#dahlia who has if you think about it is innocent to a degree given how fucked up her childhood was

Text

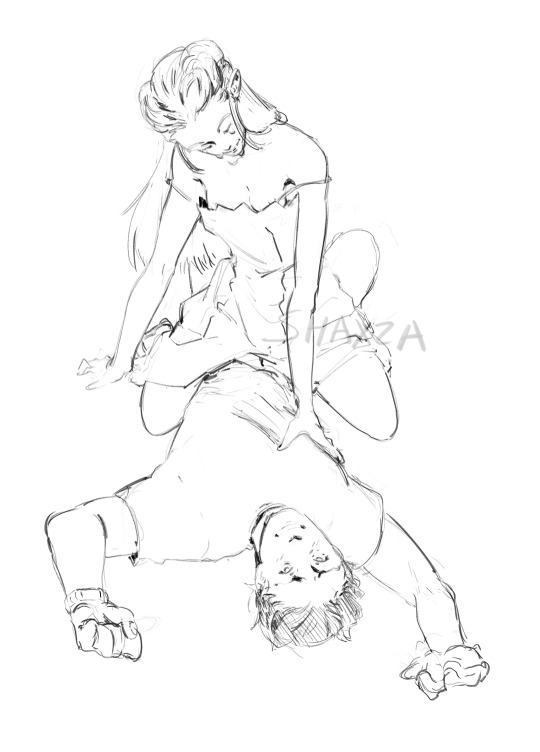

#dahlia hawthorne#ace attorney#phoenix wright#dahlia x phoenix#alexa play dark red by steve lacy#my art#since i dont want to make a dedicated post let me use my notes to vent about how much i love dahlia conceptually and how much i wish AA +#writers weren't sexist#dahlia was given the shittiest set of cards when she was a kid and she was a victim of grooming by that terry loser#she is CONSTANTLY objectified and sexualised and i think her design as a skinny young looking individual makes it even more distasteful#but i think it works if the writers could have done something with that#what i love about dahlia and phoenix's relationship is the contrast - phoenix needs to see people as innocent before jumping to help them v#dahlia who has if you think about it is innocent to a degree given how fucked up her childhood was#dahlia could have been a great case study into compassion for phoenix as she has hurt him directly but in his role as a lawyer he has to se#past certain flaws so justice can be served#and it can PUSH his understanding of what is “guilty”#yes dahlia killed people but also i choose to believe her worldview was severely warped by her enviornment and she's a product of it#or if they wanted to make her a villain and stick with it i think as a rival ro phoenix she should have been a cautionary tale#of what happens when you never learn to move beyond the shitty hand youve been dealt with and live non judgementally#anyways ^_^

289 notes

·

View notes

Note

It punches me emotionally that Phoenix either doesn't have motivation on his own or that he lets motivations inspired by other people push away things he likes, like his art degree. There's so much issues to unttangle there, like lacking direction in his life, depression, self-worth issues, identity, and so on. Also, for Kristoph's trap, it's possible that Phoenix just. Wasn't surprised that it happened. Even without potentially disassociating, he's eeriely calm.

(continued) Like Phoenix seemed to expect it could happen that he was set up. It would have been possible to prove his innocence. He didn't. Did he fear only more attacks against him would follow?

ooh, now this is a deeply fun ask to get on my day off, thank you very much anon.

I'm gonna assume this is a reference to this post where I did some tag rambling, so I'll continue some thoughts from there.

100% agree in regards to motivation. Trilogy Phoenix is fascinating to me, I know Takumi said that Phoenix tends to be something of a self-insert for the player, as the "detective" in a mystery plot he's there to solve, not act. But when you take away that doylist perspective, and go inside the text to look at him as a character, things get interesting.

The way I always saw it, the Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney games aren't really about Phoenix Wright. AA1 dedicates its largest and most significant character arc to Edgeworth, AA2 mostly has Phoenix being pushed through cases by others (all the games do this but it's really noticable in AA2) and AA3 finishes the Fey family's 3-game arc, which is more about Mia and Maya. Phoenix has very little backstory, and very few personal goals, but that's complemented by the fact that Phoenix's characterisation explains why. His motivations, his sense of self, identity, etc. all seem to exist as projections from other people. He's Edgeworth & Larry's friend because they saved him, he becomes a defence attorney because of Edgeworth's childhood beliefs, and the turnabout terror because he's emulating Mia (this is so obvious that Godot points it out). He dates Dahlia because she tells him he's her boyfriend now, his friendship with Maya begins because Mia told her to take care of him, he's Trucy's father because she casts him in the role... this is a repeated pattern for pre 7yg Phoenix. Even in terms of one of his strongest trilogy motivations - saving Edgeworth - he's still to some extent repeating the pattern that Edgeworth unknowingly set at 9 years old.

And when there aren't people around... well that's when the inverse kicks in. When Maya isn't around, Phoenix won't take cases for months (this... has always sounded like depression to me, and I think there's a really good argument for Phoenix having some form of depression. It's how I tend to write him.) He talks about Trucy "being his light", and implies that without her, he would have given up post-disbarment. Phoenix has a VERY obvious savior complex, and it's repeatedly taken advantage of; he defines his worth by how good he is at rescuing others. Examples of this off the top of my head include apologising to Lana for not fully aquiting her when she very much did commit a crime, how upset he is during AA2 because he tried to save Edgeworth and couldn't (even though it's clear that Edgeworth needed to save himself), and wanting to defend Iris even though for all he knows, she's his evil ex (at the point he decides to defend her, he has 0 evidence this isn't the same woman who tried to kill him.) But when it comes to himself? Well, he can get injured or threatened (and he does! a lot!) but Phoenix will NEVER defend himself in the same way he does other people (there's a whole tangent I could go into about how he's a very non-violent character and the few instances in the series where he's physically violent are extremly indicative of this protective streak. But I digress).

So we come to the Zak Gramarye case - Why doesn't Phoenix react? Well, he does. But to defend Zak, not himself. I think this case would have been different if any assistant had been there, whether Maya, Ema, or Pearl, because they wouldn't have accepted it, would have taken it as a challenge to themselves, and by extention motivated Phoenix. But with Phoenix alone... he's only fighting for his client. And when his client disappears... well then, he'll take it passively (If Zak had stayed, would Phoenix have pulled a turnabout? Possibly, there may have been some way to fix the situation if he'd been motivated to do so. He's arguably fought worse.)

This is why the 7yg is deeply, deeeeeeply interesting to me as someone who loves to fill in character development, because the character development that happens in the 7yg changes basically all of this. By the time we see Phoenix again in 4-1, he has gained a decidedly selfish streak, he's out for... something, whether justice, vengeance or just stopping Kristoph from hurting people, Phoenix is finally has his own goals, and he's willing to do whatever it takes to succeed. (Thus comes the reversal, Phoenix is to Apollo in AA4 what other people were to Phoenix in the trilogy, though I'd argue that Apollo has a far better developed sense of self)

Would love to hear other peoples opinions on this one though (anon you are very welcome to come back and talk more, would love to hear ur opinions on Phoenix expecting to be set-up)

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

After being on Tumblr for a while and seeing all the Manfred Von Karma hate, I've come to realize that I might've developed a soft spot for our most dispicable villain. Honestly, the guy gets FAR too much hate than he deserves. Hear me out!

One of the things we learn about Manfred Von Karma is that he has a family. He has a wife, children and grandchildren. We also know that he loves them very much, considering how much he brags about them, takes pride in everything they do and his daughter Franziksa takes pride in being the daughter of Manfred Von Karma. If you play Miles Edgeworth Investigations 2, there's a part where Manfred Von Karma brags about how good his wife's cooking is despite being an amateur. It's clear that he's a loving father and husband to his family. He even took great pride in Miles Edgeworth and his accomplishments, despite being the son of the man he killed, and made him his heir.

On the outside, it does seem strange he would love any amount of pride and care for his pupil he's going to stab in the back in Turnabout Goodbyes, but there's also plenty to consider. Manfred Von Karma's only intention was to frame Miles Edgeworth for the murder of Robert Hammond, not his father. Had he succeeded, there's a good chance Manfred Von Karma would've been permoted as Chief Prosecutor and pulled a Blackquill on Miles Edgeworth as an inmate prosecutor. So long as Miles Edgeworth still followed him like that was his Lord and Savior, he'd take it as his mentor just doing his job. Miles Edgeworth confessing to murdering his father was one thing Manfred Von Karma didn't plan and it was after he realized the note from his mentor about the murder plan that we see Manfred Von Karma inside the Record Room. We see Manfred Von Karma trying to get rid of evidence from DL-6, but we also learn from The Grand Turnabout that if there is no evidence against the Defendant, they can be declared Not Guilty. Sure, Phoenix had files of DL-6, but Manfred Von Karma doesn't know that. Sure, Manfred Von Karma hates his perfect record being destroyed, but wasn't it already destroyed anyways thanks to the Not Guilty on Robert Hammond's murder? Manfred Von Karma's not Godot, he's not going to allow a Not Guilty verdict just to indict the defendant of another crime. He's a perfectionist, if he goes down, then how can he call himself a Prosecutor? Not to say Manfred Von Karma purposely lost to Phoenix when it came to DL-6, I'd definitely disagree on that, but it's clear he was ready to burst with his guilt tumbling down on him like an avalanche. He lost his perfect record and his star pupil. You can't expect this insane guy to walk away with his head held high. The moment Miles Edgeworth realized his nightmare was real was the moment Manfred Von Karma lost everything and had no one to blame, but himself.

Manfred Von Karma's relationship with Miles Edgeworth is the one that really sticks out. This is because, strangely enough, it's a very healthy student/mentor relationship that gives us a reason for why Miles Edgeworth looked at Manfred Von Karma as some sort of god. Think of how Miles Edgeworth looks to Phoenix Wright, setting the gay jokes aside. Doesn't Miles Edgeworth also look to Phoenix Wright the same or similar way as he did with his mentor? We all know the reason why: Phoenix Wright saved Miles Edgeworth. Miles Edgeworth looked to his father to the highest degree, because he saved innocent people. So, what's the reason for him looking to Manfred Von Karma as a character who looks up to those that save innocent people and would go heaven and earth to save himself? I think that speaks for itself.

Manfred Von Karma saving people seems laughable on the surface, after seeing what he did to Gregory Edgeworth and his star pupil, but let us think of this possibility. Wasn't it also Manfred Von Karma that defended Delicia Scones from being falsely accused and framed for murder? It isn't like he had a reason to do so. I'm not saying Manfred Von Karma is Superman, but I do think that his heroic side needs to be addressed to understand why Miles Edgeworth would look up to a man like him. We need to understand why Miles Edgeworth seeing Manfred Von Karma as a murderer is what led to him writing a suicide note and being left with uncertainty of his Prosecutor’s Path. The reason is simply because Manfred Von Karma was a man that has saved innocent lives and perhaps has saved Miles Edgeworth at some point in time.

If I had to sum up what brought such a soft spot for Manfred Von Karma for me, it’s the fact he’s an evil person with a moral compass. He believes in perfection, but also loves and cares about his family and those under his authority. He’s the kind of person that would kill someone for ruining his perfect record, but is also the kind to save the innocence without being asked. He will call anyone foolish for going against him, but will defend the honor of his lowly wife, because he loves her. Manfred Von Karma is a human being that feels emotion and holds some sort of moral compass. He’s also the only mastermind villain that only murdered out of the heat of the moment. Manfred Von Karma didn’t create the earthquake or plan on Gregory Edgeworth to be stuck in an airtight elevator, then pass out to give him a moment to murder. In fact, what Manfred Von Karma did to Gregory Edgeworth is called Voluntary Manslaughter.

It’s only once you consider that Manfred Von Karma’s murder was Manslaughter and compare that to all the other villains that did murder through methods that were calculating and deliberate with the sole intention of taking someone’s life that you also have to consider that Manfred Von Karma isn’t a cold-blooded killer. Manfred Von Karma is no Dahlia Hawthorne, Kristoph Gavin, Damon Gant, Blaise Debeste, Patricia Roland, Shelly De Killer, Matt Engard, Dogen, Ambassador Alba, Redd White, Tigre, Acro and many others who had planed and calculated murders with the sole purpose of murder without regrets. Manfred Von Karma fits in with the other murderers that did murder, but only had out of passion at the moment it happened such as Frank Sawett, Dee Vascez, Godot, Jaques Portsman, Melee, Gustavia, Alita Tiala, and probably more, some of whom have been proven to only be given a lifelong sentence.

I have often had Manfred Von Karma to be given the Death Penalty, but I also consider he may’ve been given a long or life sentence. Phoenix has hinted the possibility of Manfred Von Karma having been executed, but it’s also not certain either. I don’t think we’ll ever know. What I do know is that Manfred Von Karma is in the middle on the scale of the most to least evil villain in Ace Attorney. Even his murder cannot compare to many of the most colorful villains. Manfred Von Karma murdered out of circumstances. He never planned it or even knew the outcome of it. Also, unlike the number of the most evil villains in Ace Attorney, Manfred Von Karma showed love and pride toward his family and students. He never once used them to commit any crimes or schemes. Yes, he stabbed Miles Edgeworth in the back, but again out of circumstances. Had Miles Edgeworth not shown up at Gourd Lake, Manfred Von Karma would’ve thrown Yanni Yogi under the bus quicker than a speeding train. Had he found not found Gregory Edgeworth inside the elevator or if little Miles had been awake, Manfred Von Karma would’ve not picked up the gun and just went off his merry way. Any other most evil villain would’ve found a Plan B. Manfred Von Karma would’ve been angry, but would’ve cooled down after a long walk and a cup of tea. There wouldn’t be so many No DL-6 stories, if this wasn’t the case. You’d have to admit that there was a greater chance Manfred Von Karma could’ve not murdered Gregory Edgeworth had he not been found in that elevator.

I’m certain there will always be people that hate Manfred Von Karma, even after reading this. This is more of me speaking for myself. I used to hate Manfred Von Karma with a passion after the Trilogy. After playing Miles Edgeworth Investigations 2, I began defending Manfred Von Karma. I think it was mostly because it turned out that he didn’t plan or know that the Autopsy Report of IS-7 was forged. It made me wonder if, like Miles Edgeworth and Franziska Von Karma, if Manfred Von Karma never forged evidence and was just given falsified evidence for him to use from a much bigger villain. Not saying that Manfred Von Karma isn’t a horrible person, because he is, but I don’t think he ever was trying to be a horrible person. I do think he truly believed he was doing right and saving people. Think of it this way, if Manfred Von Karma truly wanted to make Gregory Edgeworth pay and suffer in the most cruel way possible, considering how he blackmailed Jeffery Master using his daughter, which one of these would Manfred Von Karma choose: kill Gregory Edgeworth or kill his son Miles Edgeworth. Which do you believe Manfred Von Karma would use against Gregory to make him pay, if he had everything planed and calculated?

I will leave you guys with that question to think about.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

@cianidix replied to your post:

That would-be Ace Attorney fic sounds awesome :o

You know, despite the fact that I was mostly a non-presence in the AA fandom back in its heyday, the series is still very near and dear to my heart. I actually wrote a ton of fic for the series once upon a time (recently I went digging through a lot of it while looking through other old writing; I even posted the old intro to Crime of Passion while I was looking through that stuff -- it’s the last chunk in this particular post), and part of me really does want to go back and pick up some of those old ideas someday -- but this one in particular has a special place in my heart. When I think about this series and my engagement with it, that’s the fic that always comes immediately to mind, and barring the unexpected I really do think that’ll be my magnum opus for Ace Attorney on the whole.

Of course, there’s no telling when I’m actually going to get it written, or even get it completely planned out -- so there’s no harm in talking about it a little.

To start: it is canon-compliant up through AA3, at which point I just omit the case that would lead to AA4 because Phoenix needs to keep his badge. He’s a good man and a good defense attorney and I’m not putting him through that if I don’t have to. So he keeps his career, which is good, and Edgeworth decides to stick around rather than heading off to parts unknown again.

As is expected with an Ace Attorney case, everything is convoluted. That’s just the Nature of the Series. And a lot of things hinge on seemingly inconsequential bits and pieces of information -- apparent mistakes or oversights, little things that get overlooked, information that changes context once new evidence comes to light. But, as is maybe expected of me by this point, character relationships are the backbone of everything, and the relationships here run deep.

I’ve always felt a very strong sibling connection between Nick and Maya. They banter and biker and tease each other in a way that feels so much like family; there’s a kindness to the fact that even though Maya loses so much over the course of those three games, she still has family in the form of Pearl and Nick. Despite the fact that she’s going through her Spirit Medium training, I’ve always loved the idea that she wanted to honor her big sister’s memory, too, and applied herself in her spare time to studying for the bar exam so that she could become a defense attorney, too.

Meanwhile, for all that I love Phoenix and Miles as a couple, I can’t help but imagine that things would be...difficult, at first. Despite his marked improvement over the course of three games, Edgeworth still tends to keep people at arm’s length, avoiding emotional attachments to a fairly significant degree -- let’s not forget, this is the man who feigned his own death and then ran off almost immediately after his return to more parts unknown, returning only when he got word that Phoenix was in dire straits. He seems to have trouble understanding some of his own emotions (not unreasonable, honestly, given how he was raised), and therefore tries to keep them out of everything he does, personal and professional; not only that, he struggles with a need for control (again, this is very much a product of his upbringing where perfection was a requirement), and doesn’t deal well with losing it. And all of this plays into his personal life, as much as the professional one: for all that he and Phoenix are spending more time together, in and out of the courtroom, and for all that Phoenix cares deeply about Miles, Edgeworth keeps him emotionally at arm’s length, willing to broach something like friendship but never more.

Phoenix doesn’t deal well with that. If the games have shown us anything, it’s that Nick holds nothing back when it comes to his heart. He puts his all into every case, believing with everything he is in his clients’ innocence -- which is why finding that one is truly guilty of the crime they’ve been accused of comes as such a crushing blow. Even if it was mostly a puppy crush, Phoenix still put his very life on the line to try and keep Dahlia from being charged with murder, and his devastation and heartbreak when he thought that Edgeworth really had died led him to lash out at the man when he found out that it was just a ruse. Phoenix loves wholeheartedly: he’s just not capable of doing anything less. It means he has some pretty steep emotional needs, though, and with Edgeworth maintaining that distance...it wears on him. Badly.

Relationships are not easy things. They require time, care, understanding, and effort to maintain. And if only one side is putting in that labor, things are bound to crumble and fail eventually. And that’s where Crim of Passion starts: with Phoenix reaching the very limits of his ability to endure and starting to fail. He and Miles routinely face one another in court, and though private matters should stay private, it’s difficult to entirely displace private feelings in public settings. Things get...tense in court: barbs are cast in the halls outside, implications made toward the prosecution’s ill conduct toward the defense, and low blows dealt against the defense’s capabilities. The bad feelings linger through the case, simmering away on both sides...and Phoenix realizes that there won’t be reconciliation this time. He’s too tired of putting in all the work, of always being the one to accept and forgive, and getting nothing back in exchange.

So when Miles calls him to make amends, Phoenix intends to tell him that this is the end. That he can’t go on this way anymore.

But before he can, someone arrives at the office. And the last thing Edgeworth hears before the line goes dead are shots fired.

Despite his best efforts, Miles is by no means immune to his emotions. Without ever meaning to, Phoenix has gotten so much closer to him than he ever intended, slipping past his guard without the prosecutor noticing. The sound of gunshots sends him racing to the defense attorney’s office, where he finds bullet holes in the window and a blood trail on the floor, ending at the street...but when he calls the police to report a crime, he’s the one taken into custody as a suspect, a decision motivated by the known enmity between prosecution and defense. So once again, Miles finds himself behind bars -- only this time, Phoenix isn’t there to defend him; and once again, Maya has to confront the death of someone she loves, and her internal conflict as she tries to provide Edgeworth the defense counsel he deserves is enough to tear her apart.

#replies#cianidix#ace attorney#fanfiction#crime of passion#i love this thing so much to this day#also if i can play it right it's going to have some absolutely stunning turnabouts#including evidence getting completely recontextualized by a chance find#and a murder victim arriving to his own trial in the eleventh hour

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conviction (10, C+)

Why this film?: Because even people who weren’t psyched by Rockwell steamrolling the televised awards spoke fondly of this performance, and since I trusted those people, this seemed like the place to go.

The film: Conviction is the kind of film that makes you root for it, makes you want to root for it, even as you can’t help noticing its flaws. For sure, the story of Betty Anne Waters spending sixteen years to almost single-handedly prove that her brother did not commit the first-degree murder of a neighbor is the kind of Herculean feat that deserves to be lauded. But, like headlines about kids making thousands of dollars to fund medical procedures or funerals for family members, it’s the kind of that invites loads of critique about the of the systems in place that would force such a massive effort on the parts of the people being celebrated. Director Tony Goldwyn is admirably in step with Betty Anne’s point of view, but to the degree that he doesn’t, perhaps can’t ever suggest that Kenny might be guilty and Betty is spending these years working to seal his fate rather than exonerate him. Nor does he step away far enough to interrogate a police force and legal system that would have allowed this mistake to happen, even skimping over the scene of Betty Anne confronting the officer who was responsible for framing her brother. The limited scope doesn’t hold up if you think about it for too long once it ends, or even during several sequences, but within those limitations Conviction is utterly compelling. If Goldwyn can be criticized for barely seeing a world outside his lead character’s head, he’s just as responsible for creating an environment that allows all of his actors to contribute sharp and specific characterizations that feel connected to the material. Conviction’s flaws and its assets point to a startling amount of sincerity towards doing this story justice instead of coming across solely as awards bait, and though it flirts heavily with being an acting showcase and an Erin Brockovich knock-off, it still emerges in its own, minor-key and palpably incomplete way as a tribute to one woman’s endless determination and a sibling bond that few people could ever dream of boasting.

In fact, the push-pull between Conviction’s best and worst elements is arguably it’s greatest source of tension. Because Goldwyn draws more momentum out of when Betty Anne will inevitably free her brother as opposed to if she will, and because that when is framed so optimistically, the long term narrative is never very suspenseful. The movies lives or dies on a scene-by-scene basis, and what’s surprising is that Conviction stays at about the same level of quality its entire run time. It lacks the palpable ups and downs that make The Black Dahlia such a vexing and hypnotic experience, instead operating on a slightly higher average and tinier but no less affecting changes in quality. The actors consistently elevate the script even as the questions the film isn’t asking keep poking through the seams, disrupting our viewing experience to make us wish the film was a little tougher.

So what questions are the film avoiding? For one, it absolutely refuses to consider the idea that Kenny might have actually killed Katharina Bow. Betty Anne is admirably unwavering in believing that her brother is innocent, but the film is too caught up in her head to even suggest that he might be guilty. Sam Rockwell’s performance is the only source of tension in this regard, playing scenes in court and in jail that could plausibly be prescribed to either a murderer who doesn’t want to shatter his sister’s hopes or a wronged man moved and saddened by the lengths his sister is going to free him. It’s enough for us to pause in the few scenes anyone pushes against Betty Anne’s tunnel vision, opening the possibility he might be guilty even if the film never really pretends that that’s possible. The idea that she can overcome such insurmountable odds is challenged more often than his guilt, but again, it’s never really in doubt that she will eventually emerge triumphant no matter how long it takes or how strong her opponents are.

The other big gap in Conviction’s portrayal of the case is a surprising lack of interrogation into the systems that falsely imprisoned Kenny and forced Betty Anne to take on a byzantine legal system with virtually no help from any originally involved in the case, and a lack of perspective on what prison life is like for Kenny. The film is mercifully devoid of a bad apple narrative surrounding the officer who framed Kenny for murder, focusing its attention on dismantling the false evidence and speaking with the witness threatened into testifying for the prosecution. But while the sequences allowing the two witnesses - Kenny’s wife and a mistress he had around the time of the murder - to release their own pain and cooperate as they see fit are affecting and contribute fully to the narrative, they never quite shake the feeling that Conviction should be focusing more of its attention at Officer Nancy Taylor instead of evoking her as an offscreen menace. Betty Anne confronts her only once in the present, after learning that Taylor had fabricated DNA evidence against her brother, and the scene is too short to function as anything except a rejoinder from a genuinely unreliable source trying to convince Betty Anne that she has wasted her life. There is no interrogation of this woman’s action beyond her own belief that Kenny is guilty, and no other officers involved in the case are given a voice despite both witnesses saying that Taylor had a deputy present when she threatened them. It’s one thing for a film to be bashfully unwilling to confront the forces that have altered its protagonist’s lives forever, and it’s another to keep the impact of that change on the most impacted character to such a peripheral degree. Aside from an early attempted suicide and a new way of trimming his hair, Kenny’s stay in prison almost seems to be in limbo, a princess in a tower whose time there isn’t illustrated. Crown Heights, another film that’s even more weirdly unwilling to indict the police for framing the wrong man - even going so far to ignore as to underplay the racial dynamics of the case - at least shows what almost twenty years in prison did to Colin Warner. Kenny Waters gets none of this consideration, instead treated as a constant that Betty Anne must strive to reunite with.

By underplaying the severity of all potential obstacles, the film occasionally has trouble getting across the enormity of Betty Anne’s actions and the siblings’ devotion to each other. The film goes to great lengths to capture the strength of Betty Anne and Kenny’s bonds to each other, as do Hilary Swank and Sam Rockwell in rendering their relationship, but Conviction spends too much time treating her plan of attack as something any sibling would do that the moments when it underscores that this isn’t the case come off as discordant, as if the film itself isn’t entirely aware of how much Betty Anne has sacrificed for her brother regardless of whether she’s doing the right thing. Again, this is mainly symptomatic of Goldwyn attaining his vision so fully to his protagonist’s perspective, but it’s still strange to see her campaign treated mostly as durrigur. A late-film scene where her sons eventually decide that they would do for each other what their mother did for Kenny winds up playing as truncated because the film has so little distance from its heroine. Especially after the youngest and most sympathetic son describes going to such actions as “throwing my life away” for his brother, a slip of the tongue that isn’t negatively framed in and of itself, but the look of concern on Betty Anne’s face is upsetting from a perspective of viewer sympathy and frankly underexplored after she asks her son if he really thinks she threw her life away before quickly accepting him saying he didn’t mean it. In the almost two decades it took for Betty Anne Waters to get a law degree and free her brother from prison she got a divorce, seemingly lost primary custody of her children, and suffered academic and professional setbacks, yet it’s almost hard to recall the scant amount of attention these storylines received compared to Betty’s work to becoming a lawyer and her investigation into Kenny’s case. Conviction itself seems as unmoored as Betty Anne does by her son’s remarks, so impressed and in awe of her that the film is completely terrified to consider the sacrifices she’s made. The omission of Kenny’s death roughly six months after being exonerated, dying from complications after hitting his head from a great fall further illustrates Conviction’s unwillingness to poke into the darker elements of its own narrative.

Still, for all that Conviction fails or refuses to see in the story it’s telling, it does an impressive job within the boundaries it’s imposed on itself. If the compliment sounds too backhanded to be sincere, it’s worth stressing what a watchable and impressive film Conviction is, building power as it progresses. Goldwyn’s style doesn’t impose a lot of visuals to latch on to, but he’s able to tell the story with a simplicity and economy that suits its characters and setting just fine, fully earning the optimism and belief that everything will work out in the end it shares with Betty Anne. There’s also an impressive grip on the passage of time, conveying the wear and tear of sixteen years as it skips over huge chunks of time with little fanfare. Early hopscotching between Betty in law school, Kenny’s trial, and the two as children aren’t as well-coordinated as they might be, but once the film stays in the present it’s able to move forward at a healthy clip, covering a lot of ground in short scenes with strong connective tissue to each other. If the film never really commits to the idea that Kenny is guilty, it still proves itself a remarkable character study of an unbreakable sibling bond that never wavers even in its darkest moments.

Best of all is that Goldwyn has fostered an incredibly hospitable environment for his actors, creating room for two truly great performances and allowing the whole cast to play and sustain multiple emotional beats in their scenes while carving out full and consistent characterizations. Hilary Swank and Sam Rockwell are completely convincing as brother and sister, conveying decades of history together and making clear what’s special about their relationship that would inspire her to go to the lengths that she does. The evocation of The Black Dahlia earlier on only serves to highlight how fully Swank has clicked into the role, wearing Betty Anne’s stubbornness and kindness and lapses in self-determination so easily without ever getting the sense that she’s begging for the audience for sympathy. You almost wonder if her performance would play even better if the film was more distanced from Betty Anne’s headspace, giving itself and us enough distance to grasp how much she is and isn’t considering about Kenny’s chances of being freed and her own odds of success. Rockwell is able to complicate our sense of Kenny without betraying his sister’s crusade or Conviction as a whole, and his absolute joy upon being exonerated is even more affecting for the purity of his emotion. He’s charismatic and likeable, wearing his more repellent traits with the same casual appeal as his affection for his sister and his family. Their bond is the heart of the movie, and it’s in their scenes that film achieves its loveliest and saddest moments. Bailee Madison and Tobias Campbell are equally impressive in the film’s flashbacks to their childhood, evoking the same kind of love, friendship, and co-dependence amidst harsh circumstances that Desreta Jackson and Akousa Busia achieved in the introductory scenes of The Color Purple. Elsewhere Minnie Driver, Juliette Lewis, Peter Gallagher, Ari Graynor, Melissa Leo, Clea Duvall, and Karen Young all contribute memorable performances orbiting Swank’s, making the film all the more specific and alive for the textures they bring. It’s because of the performers that Conviction is so engaging, making the stakes palpable without violating Goldwyn’s vision of how he wants to tell this story.

So yes, Conviction is the kind of lightweight film that doesn’t hold up powerfully to much pressure. One wonders if this is the kind of story that benefits much from being lightweight at all, or if it should look farther than its heroine’s nose. But within those sharply limited objectives Conviction winds up telling a powerful story about one woman’s determination to prove her brother innocent and celebrates the inherent goodness of that action, finding room to give all of its characters a perspective on what’s happening and allowing its actors to contribute fully to the script. It’s perhaps the very best version of a story that speaks as much to what it isn’t saying as what it is, disposable in some ways but valuable in others, and incredibly easy to root for. One hopes it eventually builds up a good life for itself on TNT, somewhere that it can be watched and rooted for without asking too much of your attention, although it’ll hopefully earn it. It’s got two great performances, a terrific ensemble, and the kind of little guy against the system victory that deserves to be recognized. Sure it could be deeper, but what’s not to like?

0 notes