#covent garden russian ballet

Text

4 August 2000

The Queen Mother celebrated her 100th birthday at the ballet joined in the Royal Box by her daughter's Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret. For the Queen Mother's centenary night out, at the Opera House in London's Covent Garden, the Royal party saw the Kirov Ballet dance a mixed programme by the legendary Russian choreographer Mikhail Fokine.

© Fiona Hanson/PA Archive

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

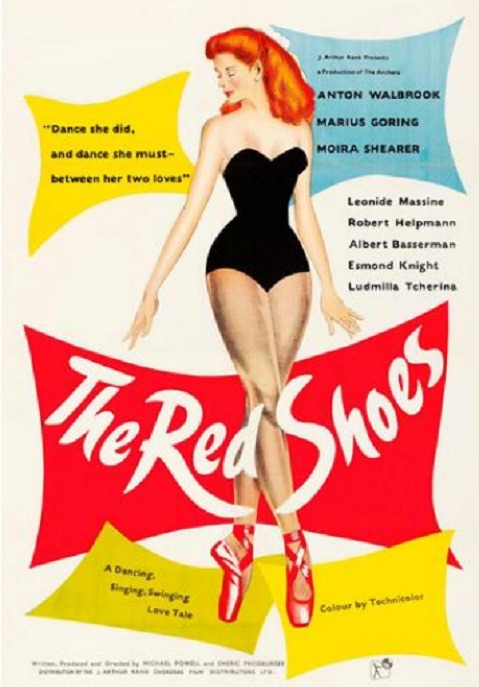

On January 17th 1926 Moira Shearer, ballet dancer and film star was born in Dunfermline.

Moira was born the daughter of Harold Charles King and Margaret Crawford Reid, née Shearer She was educated at Dunfermline High School, Ndola in Zambia (formerly Northern Rhodesia) and Bearsden Academy.

She began studying dance at 10 under Russian teacher Nicholas Legat, spent a year with International Ballet then at 16 joined Saddlers Wells Company touring with them for 4 years then became Prima Ballerina at Covent Garden. She made her film debut in Powell and Pressburger's The Red Shoes. Moira then returned to Saddlers Wells. In 1948 she danced 'Giselle for the first time, created the role of Cinderella in Frederick Ashton's production and made her first tour of America.

She toured as Sally Bowles in "I am a Camera" in 1955 and appeared at the Bristol Old Vic as "Major Barbara" in 1956. Although these performances were the start of her secondary career as an actress, she continued her primary career as a ballerina. She has appeared on TV as a ballerina and as an actress.

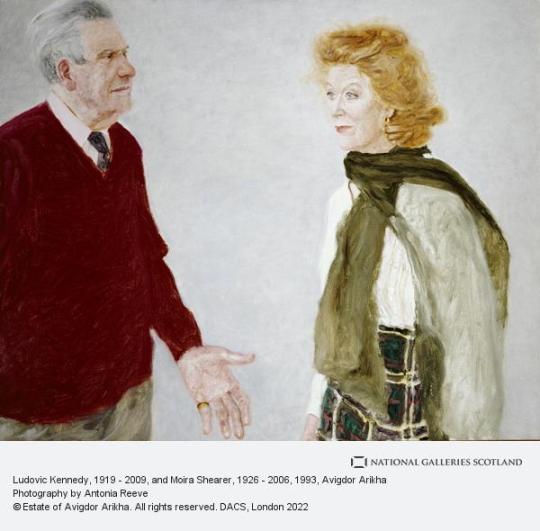

Moira was married to the journalist and writer Ludovic Kennedy, who admitted when he saw her in The Red Shoes he said that he knew instantly that she was going to be the girl he would marry. He actively sought her out and married her two years later, in February 1950 in the Chapel Royal in London's Hampton Court Palace, they had four chidren.

In 1972, Moira presented the Eurovision Song Contest when it was staged at the Usher Hall in Edinburgh. I've posted a link at the bottom, the co-comemtater was the voice of the BBC broadcasts of The Edinburgh Military Tattoo for over 40 years. It's bit of a shame sMoira had the standard BBC English accent, as was the norm in those days, I much preferred the French she used in the clip!

She also wrote for The Daily Telegraph newspaper and gave talks on ballet worldwide.

Arthur Freed wanted her to play opposite Fred Astaire in Royal Wedding in 1951, but Astaire was reluctant to dance with a ballerina. Gene Kelly asked for her for the 1954 film Brigadoon. She turned it down much preferring the classical stage in those years. She went on to play "Titania" in "A Midsummer Night's Dream" in her Broadway debut and the title role in "Major Barbara".

The joint portrait of Moira and Ludovic, by the Israeli artist Avigdor Arikha, i part of the permanent collection of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

Moira Shearer died at the Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, England at the age of 80, she is buried at Durisdeer Parish Churchyard, Durisdeer, Dumfries and Galloway, her husband, who passed away in 2009 is also buried there.

youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ballets Russes Costume, ca.1937.

Rayon, silk net, velvet, metallic fabric, braid and cord, leather, metal zips

The Ballets Russes Company, under the direction of impresario Serge Diaghilev, had a major impact on the nature of ballet in the western world from the early years of the 20th Century. Employing the most talented and creative dancers, choreographers, designers and composers, the company created spectacles of sound, colour and movement, often with an oriental or folk tale theme, that they toured throughout Europe and America.

This woman’s costume, for a young oriental dancer, is one of two in the collection that originated from the 1937 revival, at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, of Diaghilev’s 1914 production of Le Coq d’Or, a reworking as an opera based on Alexander Pushkin’s poem The Tale of the Golden Cockerel. The avantgarde artist Natalia Goncharova designed vivid sets and costumes inspired by Russian folk art for this fable set in ancient Azerbaijan. -Via JBC".

> Debra Givens > Treasure Trove of Vintage Pleasures

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Khachaturian Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia (piano arr.) Cyprien Katsaris, with sheet music

Khachaturian Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia (piano arr.) Cyprien Katsaris, piano with sheet music

https://vimeo.com/495039965

Sheet Music download here.

Spartacus ballet by Khachaturian

Spartacus, ballet in three acts by Armenian composer Aram Khachaturian, known for its lively rhythms and strong energy. Spartacus was premiered by the Kirov Ballet in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) in 1956, and its revised form was debuted in 1968 by the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow.

Khachaturian later adapted what would become his most famous ballet as a group of suites for orchestra, and, although the ballet remained a part of the Bolshoi’s repertoire, the suites provide the more familiar version.

The program of Khachaturian’s ballet (libretto by Yuri Grigorovich) was derived from a book by Raffaello Giovagnolli that details events in a 1st-century-bce Roman slave revolt; its leader, Spartacus, was a Thracian warrior captured in battle. The rebellion’s high point—literally and figuratively—was its seizure of Mount Vesuvius as a stronghold.

After two years of unrest, the rebellion was finally put down by Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Spartacus fell in battle. The surviving rebels, numbering some 6,000, were crucified along the Appian Way.

Khachaturian’s original composition was based on a narrative sketch that had been prepared earlier for the Bolshoi. It was not a great success, perhaps as much because of the choreography and the story as the music.

The 1968 version, with its contrasting moods of vibrant energy and gentle lyricism, was such a hit in Moscow that the Bolshoi took it on the road to Covent Garden the following year. By that time, the composer had already arranged orchestral suites from the ballet music so that Spartacus could reach the broadest possible audience.

Although Soviet authorities approved of the ballet, apparently seeing it as an allegory of the Russian people throwing off their tsarist oppressors, it seems quite possible to interpret its message as referring to Russians under communism rebelling against their own oppressive Soviet leaders.

Khachaturian, after all, had spent much of his life under the watchful eye of Joseph Stalin, and he had seen friends and colleagues disappear into the night.

SPARTACUS

SYNOPSIS

Spartacus is the dramatic story of the leader of a band of slaves uprising against cruel Roman rule.

ACT I

The military machine of imperial Rome, led by the Roman consul, Crassus, wages a cruel campaign of conquest, destroying everything in its path. Among the chained prisoners doomed to slavery are Thracian king, Spartacus and his wife, Phrygia. Spartacus is in despair. Born a free man, he is now a slave in chains.

At the slave market, the men and women prisoners are separated for sale to rich Romans and Spartacus is parted from a grief-stricken Phrygia, who is destined to join Crassus’ harem.

At Crassus’ palace, mimes and courtesans entertain the guests, making fun of new slave, Phrygia. Drunk with wine and passion, Crassus demands a spectacle. Two gladiators are forced to fight to the death in helmets with closed visors. When the victor’s helmet is removed, it is Spartacus, and he has killed his friend, Hermes.

In despair, Spartacus decides he will no longer tolerate captivity and incites the gladiators to revolt.

ACT II

Having broken out of their captivity, Spartacus’ followers call the local shepherds to join the uprising. Spartacus is proclaimed their leader, however he is haunted by the thought of Phrygia’s fate as a slave and he is drawn back to Crassus’ villa to find her.

Crassus is at his villa, celebrating his victories, however the festivities are cut short when Spartacus and his men break into the villa. Spartacus engages Crassus in combat and is at the point of killing him when, with a gesture of contempt, Spartacus lets Crassus go.

ACT III

Crassus is tormented by his disgrace. Fanning his hurt pride, his concubine, Aegina calls on him to take revenge.

Spartacus and Phrygia are happy to be together. But suddenly his military commanders bring the news that Crassus is on the move with a large army. Spartacus decides to go into battle but, overcome by cowardice, some of his warriors desert their leader. Spartacus’ forces are surrounded by the Roman legions. Spartacus’s devoted friends perish in unequal combat. Spartacus fights on fearlessly but, closing in on the wounded hero, the Roman soldiers crucify him on their spears. Phrygia retrieves Spartacus’ body from the battle field. She mourns her beloved and appeals to the heavens that the memory of Spartacus lives forever.

Read the full article

#noten#sheetmusicdownload#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartiti楽譜망할음악нотыnoten

0 notes

Photo

Protée (Covent Garden Russian Ballet, 1938)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

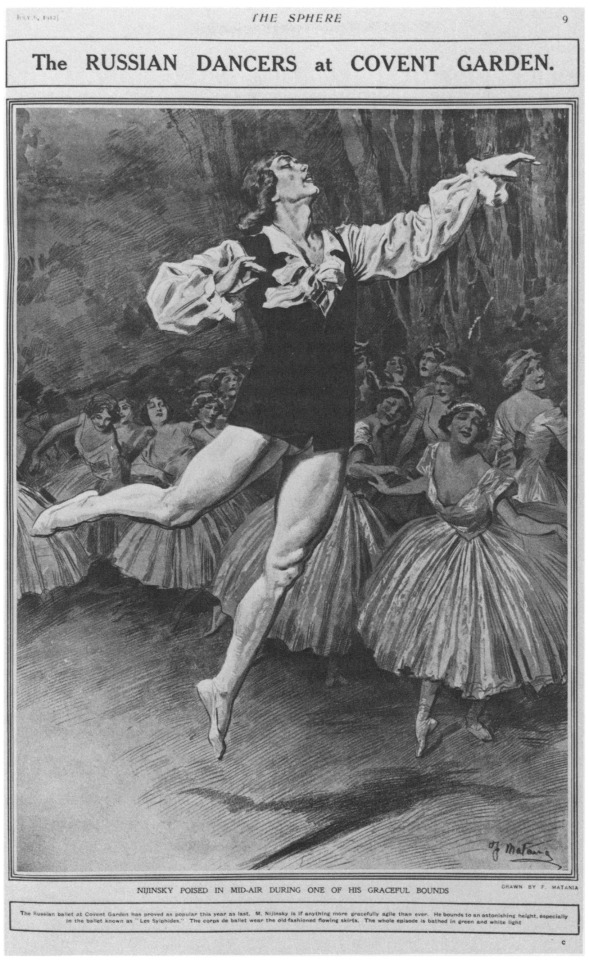

Illustration of Vaslav Nijinsky in Les Sylphides at the Royal Opera at Covent Garden (22 July 1911), by Fortunino Matania published in The Sphere (July 6, 1912).

The Russian ballet at Covent Garden has proved as popular this year as last. M. Nijinsky is if anything more gracefully agile than ever. He bounds to an astonishing height, especially in the ballet known as "Les Sylphides." The corps de ballet wear the old-fashioned flowing skirts. The whole episode is bathed in green and white light

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

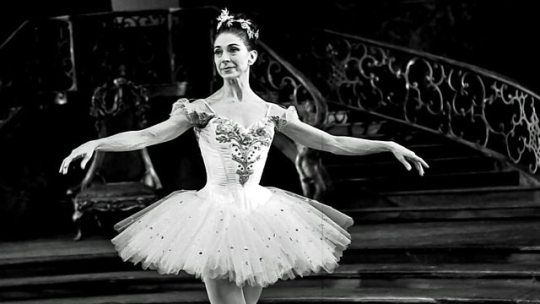

The Royal Ballet | Raymonda Act III – pas classique hongrois (Natalia Osipova, Vadim Muntagirov; The Royal Ballet)

Petipa’s Raymonda Act III is Russian classical ballet summarized in one act, full of sparkle and precise technique. Royal Ballet Principals Natalia Osipova (Raymonda) and Vadim Muntagirov (Jean de Brienne) perform the pas classique hongrois from Raymonda Act III.

Raymonda was created by Marius Petipa in 1898 for the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. It contains some of his most spectacular choreography and a magnificent score by Alexander Glazunov, full of spirited rhythms and lilting waltzes – George Balanchine called it ‘some of the finest ballet music we have’. Rudolf Nureyev had an intimate knowledge of Raymonda: he performed in the ballet as a young dancer with the Kirov Theatre and staged a full-length version for The Royal Ballet in 1964, reviving many of the dances from memory.

Nureyev presented an adapted version of Act III at Covent Garden in 1969. Against an opulent setting created by Barry Kay, a Hungarian folkdance opens the wedding celebrations for a ballerina and her cavalier. A lively male pas de quatre is followed by the famous grand pas hongrois, which contains ensembles for all 10 dancers, who wear radiant white costumes. Act III of Raymonda was performed as part of a tribute to Nureyev at the Royal Opera House in 2003.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arrivals & Departures - 18 May 1919

Celebrate Dame Margot Fonteyn, DBE Day!

Dame Margot Fonteyn, DBE (18 May 1919 – 21 February 1991), stage name of Margaret Evelyn de Arias, was an English ballerina. She spent her entire career as a dancer with the Royal Ballet (formerly the Sadler's Wells Theater Company), eventually being appointed prima ballerina assoluta of the company by Queen Elizabeth II. Beginning ballet lessons at the age of four, she studied in England and China, where her father was transferred for his work. Her training in Shanghai was with George Goncharov, contributing to her continuing interest in Russian ballet. Returning to London at the age of 14, she was invited to join the Vic-Wells Ballet School by Ninette de Valois. She succeeded Alicia Markova as prima ballerina of the company in 1935. The Vic-Wells choreographer, Sir Frederick Ashton, wrote numerous parts for Fonteyn and her partner, Robert Helpmann, with whom she danced from the 1930's to the 1940's.

In 1946, the company, now renamed the Sadler's Wells Ballet, moved into the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden where Fonteyn's most frequent partner throughout the next decade was Michael Somes. Her performance in Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty became a distinguishing role for both Fonteyn and the company, but she was also well known for the ballets created by Ashton, including Symphonic Variations, Cinderella, Daphnis and Chloe, Ondine and Sylvia. In 1949, she led the company in a tour of the United States and became an international celebrity. Before and after the Second World War, Fonteyn performed in televised broadcasts of ballet performances in Britain and in the early 1950's appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, consequently increasing the popularity of dance in the United States. In 1955, she married the Panamanian politician Roberto Arias and appeared in a live colour production of The Sleeping Beauty aired on NBC. Three years later, she and Somes danced for the BBC television adaptation of The Nutcracker. Thanks to her international acclaim and many guest artist requests, the Royal Ballet allowed Fonteyn to become a freelance dancer in 1959.

In 1961, when Fonteyn was considering retirement, Rudolf Nureyev defected from the Kirov Ballet while dancing in Paris. Fonteyn, though reluctant to partner with him because of their 19-year age difference, danced with him in his début with the Royal Ballet in Giselle on 21 February 1962. The duo immediately became an international sensation, each dancer pushing the other to their best performances. They were most noted for their classical performances in works such as Le Corsaire Pas de Deux, Les Sylphides, La Bayadère, Swan Lake, and Raymonda, in which Nureyev sometimes adapted choreographies specifically to showcase their talents. The pair premièred Ashton's Marguerite and Armand, which had been choreographed specifically for them and were noted for their performance in the title roles of Sir Kenneth MacMillan's Romeo and Juliet. The following year, Fonteyn's husband was shot during an assassination attempt and became a quadriplegic, requiring constant care for the remainder of his life. In 1972, Fonteyn went into semi-retirement, although she continued to dance periodically until the end of the decade. In 1979, she was fêted by the Royal Ballet and officially pronounced the prima ballerina assoluta of the company. She retired to Panama, where she spent her time writing books, raising cattle, and caring for her husband. She died from ovarian cancer exactly 29 years after her premiere with Nureyev in Giselle.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Homage to the Ballet - Impressions in line and aquatint by Harold Byrne of the Covent Garden Russian Ballet from drawings made from the wings during actual performances by the Ballet, Sydney ,Australia 1939.'Les Sylphides.'

(Byrne,1879-1966,was born in Goulburn,New South South Wales and studied for several years with Julian Ashton as well as Sydney Long from who he acquired a knowledge of etching.He then taught etching at the Technical College,Hobart,Tasmania in 1932. In 1933 he designed and printed his first book-plate printing from his own press.. His works are held in various public & private collections in Australia.)

(via eBay)

#art#aquatint#harold byrne#russian ballet#female portrait#artwork#1930s#australian artist#graphic artist

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fic Rec List July 2017

R & R (Risk and Ruination)

fishingclocks

Summary:

On the floor by Yuuri’s bed, there is a forlorn little beep, as Yuuri receives his fifteenth unanswered notification of the morning.

One of them from his fiance.

One of them reading ‘YUURI!! TAKE THE DAY OFF!!! YOU’VE BEEN WORKING HARD AND I LOVE YOU BYE’ followed by a copious amount of varying heart emojis.

Going ignored, the screen goes dark.

Of Office Blunders

BunniesofDoom

Summary:

Yuuri accidentally sends a picture to his boss that he really shouldn’t have sent. AU.

“OOC MY ASS!”

preciousbunnynoiz

Summary:

Yuuri secretly writes fanfiction, including Victor Nikiforov/Katsuki Yuuri fanfiction and some asshole keeps telling him he writes too OOC.

Yuuri hates him so much

I’m Pretty Much Fucked

monstersinthecosmos

Summary:

Quick drabble about getting ready to have company over. :)

If you can’t take the heat…

mtothedestiel

Summary:

Stay tuned, coming up next it’s Top Chef: International! Join thirteen chefs from around the globe as they battle it out for glory and prizes in the one and only New York City (and share all their innermost thoughts along the way!) Who will emerge victorious, and who will burn out?? Heartwarming triumphs, devastating eliminations, and even ~forbidden romance~ are all coming your way on this showstopping season of Top Chef!

To Worship and Be Worshipped

Unforth

Summary:

Tumblr ficlet written to the prompt: Yuuri as god/deity of some sort and Victor as a completely besotted worshipper

Déjà Vu

KasumiChou

Summary:

“Are you planning to sleep all day?”

A voice questioned with a soft chuckle. A chuckle that set his heart alight.

Victor lay there for a moment, a feeling of déjà vu overtaking him.

Warning: Major Character Death

Soul Loop

Cherry101

Summary:

It was almost funny, how easily it was to watch the day restart.

At this point… it was even common. Every few weeks, there would be a day that would repeat itself. Once, twice, three times, and then everything would go back to normal.

Otabek knew what it was, but he didn’t know what to do about it.

All The Beauties In His Hands

WinterSky101

Summary:

The wedding of Jean-Jacques Leroy and Isabella Yang is the wedding of the century.

Load Paper Tray 1

esutonia

Summary:

Perhaps, Victor realized, they were all gifted in their own ways. The way that Victor could charm the ancient, malfunctioning Xerox into producing perfect packets was perhaps the same way that Yuuri could print carts of brochures but not once refill the paper trays.

Soulmates/Office AU: Everyone has a little magic in them, but soulmates’ powers complete each other. Soulmates don’t know they’re meant for each other, until they figure out how their powers fit together. Victor and Yuuri work for the same company, and end up together with the help of a particularly old, obnoxious Xerox.

we have at least eleven minutes

spicyyuuri

Summary:

just a quickie between gala performances. no big deal, right?

nsfw victuuri week ♔ day two ♔ clothes

Ache

Val_Creative

Summary:

She misses everything about Minako. Hasetsu isn’t the same — too quiet, too empty of joy and laughter.

rouge my knees and roll my stockings down

alykapedia

Summary:

“It’s just that only whores wear the knot in front,” Yuuri says, stepping in close to breathe in Viktor’s intoxicating scent before peering up at him through lowered lashes and affecting an accent he’s heard during one of his and Phichit’s ill-advised jaunts to Covent Garden. “Did you want me to be your whore, milord?”

(Or: A morning well-spent with Lord Nikiforov and his expensive whore.)

At First Bite

opalish

Summary:

“Phichit,” Yuuri said slowly, noting that the hamsters currently had fangs. Tiny, needle-sharp fangs. “Did you name your hamsters Spikester, Hamsticula, and Edward Cullen II because they actually drink the blood of the innocent?”

“Oh, you caught that?” Phichit asked with a winning smile.

The Track

YuriPirozhki (AceOfSpace)

Summary:

JJ liked to think that one day, he could realise his goal of skating flawlessly to a program and song that he’d put together by himself. That would be the day when he’d be more than just Jean-Jacques Leroy, the son of ice dancing’s power couple. He’d be JJ Leroy: Record breaker, history maker, and one of a kind. He was convinced that his new guitar would help him to get there.

places to go, sights to see

Mayarene Rose (Paradise_of_Mary_Jane)

Summary:

This is what Yuuri knows: There is a giant green monster blob, a man with a blue box, and a planet called Barcelona. Also there’s time travel.

(“Time and Relative Dimension in Space,” the Doctor had proudly explained which made absolutely no sense. But then, nothing in the past hour had made any kind of sense so Yuuri’s willing to go with it.

It’s probably not a dream. Probably.)

Boof? Boof.

JMonCheri

Summary:

Makkachin tells us on how Viktuuri sexy times go down.

WARNING: EXTREMELY explicit. Don’t read unless you want to nut your intestines out.

Soft Things

airspaniel

Summary:

Yuri dresses up, with a little help.

Always Looking Out for You

TripCreates

Summary:

Mari walks over to the closet to start getting things out. She reaches for a box up on a shelf and she begins to pull it toward her. Once it slides off the edge, some sheets of paper slip off the shelf from underneath the box and drift to the floor.

Mari laughs as she sees the familiar Viktor posters land on the floor. “I was wondering where those went.”

~~~

Or Mari helps Yuuri pack up his room as he gets ready to move to St. Petersburg to be with Viktor.

love is blind(folded)

hamartiawrites

Summary:

It’s the day of Viktor and Yuuri’s wedding.

Everything looks perfect. The decorations are perfect, every single visitor looks stunning, and Phichit is certain Yuuri will look absolutely breathtaking when those big doors at the end of the hall open.

There’s just one problem, and unfortunately, it’s a big one.

The groom, Viktor Nikiforov? The five time world champion? The Living Legend? The most decorated men’s figure skater in history?

Yeah, he looks downright ridiculous.

(Or the time where Phichit thought Viktor wanted to hurt Yuuri when all Viktor wanted to do was hurt himself with Yuuri’s beauty.)

My Favorite Shape

thoughtsappear

Summary:

Isabella has never doubted Yuri Plisetsky’s animal magnetism.

Firebird

LavenderProse

Summary:

“It’s almost like a marriage proposal,” Viktoria says, and the thing is—the thing is, if Viktoria wanted it to be, Yuri would make it one. If Viktoria had asked, “Is that a marriage proposal?” Yuri would have unhesitatingly said yes. She would have lowered herself onto a knee before Viktoria in Fukuoka Airport, the officially certified least romantic place in the world, and said Viktoria Konstantinovna Nikiforova, please—please—

(Yuri doesn’t know if Viktoria will stay. She wants her to. She wants her to want to. But she doesn’t want to be the only thing holding Viktoria here. Life for Yuri Katsuki is, as always, Hard.)

Cherry

sophiahelix

Summary:

Now Mila turns to look at her, blue eyes open and bright. She offers the cigarette back, pinched between two fingertips lacquered red as her lips, and quirks a smile, sarcastic and knowing. “You mean you don’t support your brother no matter what?”

“Hmph,” Mari snorts, and takes the cigarette back.

Situation Status: Possibly Awesome

ineptshieldmaid

Summary:

It’s early in the season, his first year competing in the Grand Prix as a senior, and Kenji is in a Situation.

We’ll Always Have Paris

Teuthida

Summary:

Lilia recognized her, of course.

The Struggles of Living with Viktor Nikiforov

Minipandacakes

Summary:

Yuuri had imagined life with Viktor in St. Petersburg as being a perfect blur of snuggles and laughter and kisses. And while he was right, he wasn’t quite prepared for the frustration that comes right along with the happiness when you first make a home with your partner. This one-shot is made up of a trio of short stories I couldn’t resist writing out. Enjoy!~

Blades of a Ballet Dancer

Katrinova

Summary:

When word gets out that Yuuri helped create his record breaking routine Yuri On Ice, the world wants to know if he thinks he could do solo work. Yuuri says no, everyone else disagrees. Obviously, everyone else is a traitor.

Part of Yuuri Week 2017

Day 4- [Theme: On Ice]

Strut For Me

Katrinova

Summary:

“Darling, as your coach and choreographer it is also my job to make sure you get the exposure you deserve!” Or, there were aspects of being a world champion figure skater Yuuri was not prepared for. At all.

Part of Yuuri Week 2017

Day 5- [Theme: Eros]

Tweet tweet - Yuuri Week Day 7

hazelandglasz

Summary:

In which Yuuri should never be left alone with a full bottle of vodka and a fully charged phone

[Player] is Suffering From Thirst. [Player] is Well Again.

counterheist

Summary:

“Tell him you’re a blacksmith, Yuuri, tell him you’re good with your hands.”

“…but I’m not a blacksmith?” Phichit is a blacksmith. Yuuri used to make saddles and gaze longingly at daguerreotypes of men wearing the newest shirt collar designs. Now he gazes longingly at Russian immigrants. Maybe he’ll see Nikiforov wearing a new shirt at the next Fort. Maybe he’ll drown at a river crossing first.

Who’s to say?

Crop Top Distraction

nerdlife4eva

Summary:

When Yuuri, Phichit, Victor, and Yurio take a vacation to an all-inclusive resort, Victor’s and Yurio’s fans begin to monopolize their time. Even though Yuuri is understanding, he easily goes along with Phichit’s plan to regain Victor’s attention. These dorks fall in pools over each other. Yuuri is in a crop top, Phichit is in a crop top. Victor is lucky to be alive.

This is part of YuuriWeek and the amazing art is thanks to my insanely talented friend Magical-Mistral please go give this artist some love and watch for our future collabs!!

not in service

PuggleFiclets (Pugglemuggle)

Summary:

“You know what they say…” Yuri replies. “If you crack the ice once, you better be ready to shatter the whole motherfucking pond.”

In a dictatorship dominated by the International Skating Union, Yuri was bound to end up in prison sooner or later. He isn’t planning to stay there, though. No—Yuri’s got bigger plans.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nureyev is an important new documentary about Rudolf Nureyev’s extraordinary life which will be shown in cinemas around the UK from 25 September.

BAFTA nominated directors Jacqui and David Morris have interviewed Nureyev’s colleagues from the dance world – Alla Osipenko, Ghislaine Thesmar, Dame Antoinette Sibley, Clement Crisp, Meredith Daneman – but sensibly don’t fill the screen with them sitting on sofas surrounded by ballet memorabilia, but illustrate their contributions with video clips and photos, enabling them to pack far more into the film’s already generous 1hr 50min running time. There is much to show because the filmmakers have unearthed 16 minutes of unseen video.

The documentary is divided into thematic blocks rather than being a simple chronology and these are interspersed with quotes, the first being from Napoleon, “Great people are meteors designed to burn so that the earth may be lighted,” and the film proceeds to show how greatly Nureyev illuminated the dance world.

There is an interesting archival recording of Yehudi Menuhin who says,

There is something in the background of any Russian, whether he be Jewish or a Tartar, which dramatizes a situation; it’s more potent, more intense. It probably comes from the fact that they have such an otherwise difficult life, as it’s always been for hundreds of years between snow and mud, and they are almost harnessed to the earth and the problems of life. It enables them when they are liberated on the stage to live life as they would have liked to have lived it, with all the abandon and the capacity for focusing, for dramatizing, for intensifying the emotion and the thought. It’s as if the sun were shining through a lens and you focus it on something and it started burning. The whole of life, the whole universe, focuses itself through the greatest Russians and they start burning, burning up the audience and burning up themselves.

These neatly connected quotes and thoughts pertinently explain Nureyev’s character, and is typical of the film’s sensitivity and understated reflections on the nature and career of this gigantic influencer. It has no sensationalism but is reflective and full of warmth.

Russell Maliphant has created scenes, sort of dance tableaux, which illustrate the mood of extracts from Nureyev’s memoirs, read by Siân Phillips, and other audio recollections and commentary – dancing in the snow, huddling among the Russian birch trees, folding sheets. Theatre composer Alex Baranowski — who wrote the score for Northern Ballet’s 1984 — has created a suggestive background for these scenes, indeed the whole film, and Lucia Lacarra and Marlon Dino are two of the dancers who appear.

The fascination with the West in the ‘50s drew young Russians to make homemade records of its evil pop music and to dance the jitterbug behind closed doors — including young ballet dancers. The film is outstanding at contextualising this and other periods of Nureyev’s life. While Russia didn’t have teenage dance moves or gigantic American fridges, it did have two powerful weapons at its disposal, the Kirov and the Bolshoi, and what better way to enhance Russian prestige around the world than by having these companies tour abroad.

The Kirov was in Paris in 1961. Alla Osipenko, one of Nureyev’s partners, says,

We were totally into the underground nightlife at the time and it was a real challenge to return unseen in the morning… Rudolf was a free spirit: “This is how I want my life to be and I will live it that way. I don’t want to live the way you order me to. I will walk my own path in life.”

Nureyev defected in Paris in 1961 on Osipenko’s 29th birthday. For this, she, and many others, paid a price.

I was not allowed to leave the country for 10 years. I knew how to block those things out, saying to myself, “It’s not vital to go to America.”

The film focuses on his relationship with Erik Bruhn — Sibley: “All my generation, us girls, were in love with Erik Bruhn.” — and that with Margot Fonteyn, who invited the young Nureyev to dance in a gala at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on 2 November 1961. John Tooley, former director of the Royal Opera House has another slant on the story,

He wasn’t exactly invited over here – he arrived. He had written to Margot and said, I want to appear in your gala and I want to dance with you.

A Fonteyn quote:

Genius is another word for magic, and the whole point of magic is that it is inexplicable.

And ‘magic’ was the word used to describe the effect of their partnership on stage.

Fonteyn explains,

I believe that our partnership would not have been quite such a success if it hadn’t been for the difference in our ages, because what happened was that I’d go out on the stage thinking, who’s going to look at me with this young lion leaping ten feet high in the air and doing all those fantastic things. And then Rudolf had really this deep respect because I was this older, very famous, established ballerina. So it sort of charged the performance that we were both going out there inspired by the other one, and somehow it just worked.

Nureyev almost immediately rustled feathers at The Royal Ballet when he modified its production of Swan Lake after Fonteyn had agreed to do it his way. He justified his approach,

We became one body, one soul, we moved in one way, it was very complimentary, every arm movement, every head movement, there were no more cultural gaps or age difference, we were absorbed in characterisation. We became the part.

It was revolutionary and most of the audience loved it. One of the Covent Garden establishment said that Nureyev was like the Great War, wiping out a generation of male dancers on his arrival. The success of the Fonteyn/Nureyev partnership was unprecedented. Sibley says,

Footballers must have this all the time, this yelling and screaming, and it was unbelievable. It was out of all proportion to anything one had been accustomed to before.

Lucia Lacarra and Marlon Dino

A section of the documentary devoted to Nureyev’s often difficult character hears him describing his Tartar blood:

It runs faster somehow, it is always ready to boil, and yet it seems that we are more languid than the Russians, more sensuous — we are a curious mixture of tenderness and brutality.

English National Opera’s master carpenter, Ted Murphy, remembers some of the fights,

Over the years he’d have different people looking after him on stage and he used to kick them, punch them, slap them – I’ve seen all of that happening – but it was all to do about how his performance was really.

National Ballet School of Canada’s Betty Oliphant tells the story of her student who was playing a pageboy, excitedly telling her that Nureyev had spoken to him:

I said, “Oh that’s wonderful. Was he nice?” And he said, “Well, he told me to fuck off.”

Drawing by Jamie Wyeth

On love and relationships, the film documents the competitive love affair between Nureyev and Bruhn, which turned sour as Nureyev began to overshadow his former mentor. Pierre Lacotte recalls witnessing tremendous arguments between them.

As he told me one day — says Ghislaine Thesmar — you have to choose between giving your energy to love a human being or to love your art. You have to choose, you can’t have both… If you give yourself to art, nobody can take the place of art, it’s impossible. They can accompany you as long as they can stand it but then if you lose them you lose them, it’s not important.

When talk show host Michael Parkinson asked him if he had a sense of belonging anywhere, he replied simply, “Dance”.

Nureyev was open to newer forms of dance, different ways to move. He admired Martha Graham greatly, who remembered,

Rudolf came to see me backstage and just stood and looked at me and we didn’t talk about anything. Finally, it came out that he has an appetite for the new and he wants to experience everything to its fullest. He said, “I do not mind if I make a fool of myself.”

There is some previously unreleased amateur footage of him in some of the Graham works he performed. Other unseen clips of Nureyev in action show him rehearsing Nutcracker with Claude de Vulpian during his time as the Artistic Director of the Paris Opera Ballet.

The clubbing and cruising part of his life is coloured with moody archive footage of bathhouses and discos. Former New York City Ballet Principal Dancer, Heather Watts, was one of the first artists to join the fight against AIDS in the mid-1980s:

The year is ’82 and suddenly we start hearing about boys dying, just dying, and there’s real fear. The partying stopped, the fun stopped, and we started burying our friends. It was like a war.

In 1987 when Nureyev was finally allowed to return to Russia to visit his dying mother, his face had started to look slightly gaunt. He had been diagnosed with HIV in 1984.

Margot Fonteyn died in 1981. He said,

It was very lucky for us to have those glorious years. She became a very, very great friend of mine. To me she is part of my family. That all what I have – only her.

His own death came less than two years later.

Ghislaine Thesmar:

I really think this man was exceptional. I don’t mean the Rudolf of photos, making faces or scandals and all these cheapy things, I mean the real man he was… I think he defended the world of ballet. He loved ballet like a child would love a god, it was beautiful to see that.

An emotional Antoinette Sibley chokes as she says,

He was a very special person, and I feel very proud to have been part of it.

Nureyev, the film, will be launching in cinemas nationwide from 25 September 2018 with daily previews at Curzon Mayfair, London from 21 September.

Preview: Nureyev the film is a glorious celebration of an exceptional life Nureyev is an important new documentary about Rudolf Nureyev’s extraordinary life which will be shown in cinemas around the UK from 25 September.

#Antoinette Sibley#Erik Bruhn#Margot Fonteyn#Martha Graham#New York City Ballet#Royal Opera House#Rudolf Nureyev#Russell Maliphant#The Royal Ballet

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Royal Opera House has cancelled a planned residency by Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine. The Russian dance troupe was set to stage 21 performances from July 26 to August 14. The Bolshoi last performed at the venue in London’s Covent Garden in 2019, with stagings of Swan Lake, Spartacus, Don Quixote and The Bright Stream…!!!👍🏼👊🏼 (at New York City Ballet) https://www.instagram.com/p/CadDMARJmLw/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Kuznetsova, Maria (1880–1966) Russian soprano whose vast repertoire, expressive voice, and powerful acting place her in the highest rank of singers in the early 20th century. Name variations: Mariya Nikolayevna Kuznetsov; Marija Nikolaevna Kuznecova. Born Maria Nikolaievna Kuznetsova in Odessa, Russia, in 1880; died in Paris, April 26, 1966; daughter of Nikolai Kuznetsov; married to a son of Jules Massenet.Maria Kuznetsova was born into the brilliant cultural universe of late tsarist Russia, a world of profound contrasts between glittering balls, ballets, and operas, and the oppressive poverty and illiteracy of the peasantry. From Maria's earliest years, the newest ideas in music, literature and the theater were discussed in her home. Her father Nikolai Kuznetsov was a highly regarded painter whose portrait of the composer Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky has become universally recognizable. Initially, Maria showed great talent as a dancer, and she first appeared on stage in ballet at St. Petersburg's Court Opera. Soon, however, she decided to become a singer, studying for a number of years with Joakim Tartakov. Her 1905 operatic debut at the Mariinsky Theater as Marguerite in Gounod's Faust was an unqualified triumph. Acclaimed as a star, Kuznetsova took part in several operatic premieres, including that of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh on February 20, 1907. Her starring roles over the next few years included Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, Traviata, Madame Butterfly, and Juliette in the Gounod opera Roméo et Juliette. Starting in 1906, she began to sing outside Russia, performing in both Berlin and Paris.Paris quickly became Kuznetsova's second artistic home. Much beloved at both the Grand Opéra and the Opéra-Comique, she appeared in various French roles, including Chabrier's Gwendoline (1910) and Massenet's Roma (1912), as well as in the standard roles of Aïda and Norma. In 1909, Kuznetsova's international reputation was further enhanced when she made her debut at Covent Garden. That same year, she crossed the Atlantic to perform at New York City's Manhattan Opera House as well as in Chicago. In 1914, Kuznetsova returned temporarily to dancing, appearing with great success both in Paris and in London, where she created the role of Potiphar's wife in the Richard Strauss ballet Josephs-Legende. She also sang the role of Yaroslavna in the first British performance of Aleksander Borodin's Prince Igor. Given at the Drury Lane Theater and conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham, this was the legendary "Russian season" that introduced a wealth of new Russian opera and ballet to the English-speaking public.As a Russian patriot, Kuznetsova felt dutybound to return home at the start of World War I, performing on stage as well as in benefit concerts for the war effort. In 1916, she braved the Uboat-infested Atlantic to perform once more in the United States. On her return to Russia in 1917, she saw her country first overthrow tsarist tyranny and then quickly descend into anarchy, with the year ending in a seizure of power by the Bolsheviks. Determined to escape the Communist regime and Vladimir Lenin's proletarian dictatorship, Kuznetsova succeeded in fleeing by ship to Sweden, having disguised herself as a cabin boy and then hiding in a trunk. Virtually penniless, she supported herself in her Swedish refuge for the next several years by giving song recitals with the tenor Georges Pozemofsky, also performing as a dancer during the same program.By 1919, Kuznetsova's career was once more on track when she was invited to sing major roles at the Copenhagen and Stockholm opera houses. In 1920, she appeared again on the stage of Covent Garden, and the same year she settled in Paris, which had been transformed into a center of emigres from revolutionary Russia. Married to a son of the French composer Jules Massenet, Kuznetsova was a major personality in the social and artistic life of interwar Paris. Versatile as ever during these years, she not only sang operatic roles, but also appeared in operettas and even experimented with a new career as a motion-picture actress. In 1927, she took on another role, as impresario of a new opera company comprised largely of Russian emigres, the Opéra Russe, which survived until 1933 when it succumbed to the economic depression.During the Opéra Russe's relatively brief but brilliant existence, Kuznetsova was not only its director but its unchallenged prima donna. Specializing in the Russian operatic repertoire, it had Paris as its base but made guest appearances at major opera houses throughout Europe, including Barcelona, London, Madrid, as well as at Milan's La Scala. In 1929, Kuznetsova and her company toured South America, presenting several previously unheard works in Buenos Aires, including Mussorgsky's The Fair at Sorotchinsk and Rimsky-Korsakov's Snegourotchka (The Snow Maiden). As late as the mid-1930s, Kuznetsova was still singing professionally. In 1934, she replaced the celebrated Conchita Supervia for a performance of Franz Lehár's operetta Frasquita, and in 1936 she undertook a strenuous and successful tour of Japan. After her retirement from the stage, she accepted an assignment as artistic advisor of the Russian operatic repertoire at Barcelona's Teatro Lirico. She lived the final decades of her life in Paris, dying there on April 26, 1966.Boasting a repertoire ranging from the entire body of Russian opera to Salome, Aïda, Norma, Mimi and Gounod's Juliette, Kuznetsova not only possessed what critic Alan Blyth has described as a "gleaming voice and shimmering vibrato," but also was a famously beautiful woman whose stage charisma was legendary. Added to this were her talents as a dancer, which led some of her contemporaries to compare her artistry to that of Isadora Duncan . Many have described her superb acting talent as being equal to that of the legendary basso Fyodor Chaliapin. Highly expressive both as a singer and an actress, Kuznetsova left as a tangible legacy only 36 recordings, both acoustic and electrical, made between 1905 and 1928 for the Pathé and Odeon labels. Fortunately, all of these performances are of the highest artistic quality and have been transferred to the compact disc format in Pearl Records' compilation Singers of Imperial Russia. Critic Albert Innaurato has called Kuznetsova "one of the great singers on disc [whose] records have a fragile, tender allure, the glamorous magic in her sound closely fit to a musical sensitivity that is hard to match."

1 note

·

View note

Text

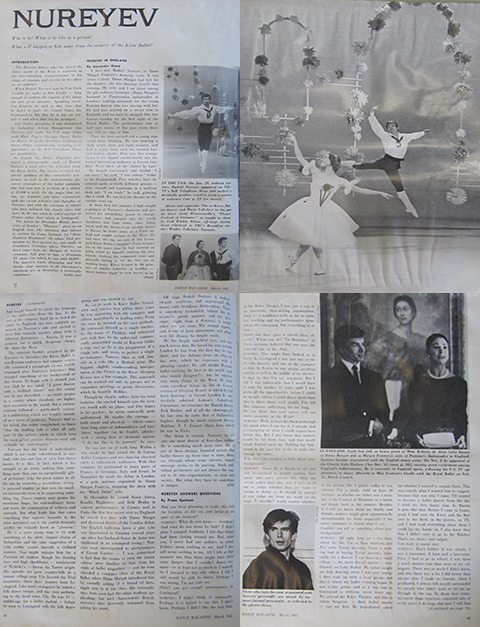

DANCE MAGAZINE march 1962: NUREYEV

NUREYEV

Who is he? What is he like as a person?

What will happen to him away from the security of the Kirov Ballet?

INTRODUCTION

The Russian dancer who has joined the dance world of the West is stubborn in his determination, temperamental in his range of emotion, and electric in his effect on an audience.

When Rudolf Nureyev was in New York recently we spoke to him briefly — long enough to confirm the reports of his sharp wit and great intensity. Speaking excellent English, he said at that time that he hopes to make the United States his headquarters. But that he is not yet certain if and when that can be arranged.

Just before presstime it was announced by Columbia Artists Management that Nureyev will make his U.S. stage debut with Ruth Page’s Chicago Opera Ballet on March 10 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Other commitments, including a reappearance on the Bell Telephone Hour, are possibilities.

In August ’61, Dance Magazine presented a photographic study of Rudolf Nureyev a week after his defection from the Kirov Ballet. The photos revealed the special qualities of this remarkable performer, as well as the unmistakably decadent atmosphere of the ballet company that had won him to perform at a salary of $2,000 a week. On the pages that follow, we acquaint you more extensively with the recent activities and thoughts of Nureyev, and with the reactions of others who have followed him closely since last June 16, the day when he asked asylum in France rather than return to Leningrad.

The article by Alexander Bland, dance critic of London’s “Observer,” gives us an English view. The interview that follows it, written by Franz Spelman for “Show Business Illustrated” (by whose kind permission we here present it), was made in Frankfort, Germany, where Nureyev, on brief leave from the Marquis de Cuevas company, had gone to tape a 20-minute TV show (for which he was paid $4,000). The dancer’s frank, disarming, and brilliantly clear answers to the interviewer's questions are in themselves a memorable experience.

Lydia Joel

NUREYEV IN ENGLAND

By Alexander Bland

I first met Rudolf Nureyev in Dame Margot Fonteyn s drawing room. It was seven o’clock. Dame Margot had left for the theatre; she was dancing Giselle that evening. My wife and I sat alone among the gilt embassy furniture (Dame Margot’s husband is Panamanian ambassador in London) waiting anxiously for the young Russian dancer who was staying with her. He had just arrived on a secret visit to England, and we were to smuggle him into Covent Garden for his first sight of the Royal Ballet. The performance was at half past seven. At five past seven there was still no sign of him.

Then the door opened and a young man stood there blinking. He was wearing a dark sports shirt and tight trousers, and had a gypsy look with his tousled hair and hollow cheeks. How was this strange figure to be slipped unobtrusively into the formal dressed-up audience at Covent Garden? Were these all the clothes he had?

He bowed courteously and smiled. “I am sorry,” he said. “I was asleep.” Calmly he disappeared. Five minutes later he entered again, a totally different person — slim, smooth and handsome in a well-cut dark suit. “I am ready,” he said, grinning like a child. We reached the theatre as the curtain went up.

In those first few minutes I had caught a glimpse of Nureyev’s character and perceived his astonishing power to change.

Nureyev had jumped into the world headlines last June when, after being faced with the threat of an ignoble return to Russia, he broke away on a Paris airfield and sought asylum in the West. He bad been the big success of the Leningrad Kirov Ballet Company’s Paris season; but in his spare time he had insisted on going round by himself, making his own friends, shirking the organized tours and generally failing to toe the line out of working hours. When it came to the prospect of similar behavior in London where matters might be even worse, as he (Over p. 42) had taught himself to speak the language – the authorities drew the line. As the rest of the company lined up to board the plane for England, two men suddenly appeared at Nureyev's side and started to steer him towards another plane with a different destination — Russia. It was a moment for a quick, desperate choice. He chose the West.

[FOTO] IN THE USA: On Jan. 19, without fanfare, Rudolf Nureyev appeared on NBC-TV’s Bell Telephone Hour and evoked a decidedly positive reaction from a national audience (see p. 23 for more).

[FOTO] Above and opposite: The ex-Kirov Ballet dancer and Maria Tallchief in the pas de deux from Bournonville’s “Flower Festival at Gensanoas” taught to them by Erik Bruhn. Below, off-stage during dress rehearsal at NBC’s Brooklyn studio: Bruhn, Tallchief, Nureyev.

The souvenir booklet prepared by the Russians to introduce the Kirov Ballet to non-Russian audiences last summer originally contained a paragraph (it was hastily expunged after Nureyev's defection) that revealed something of the background of this drama. To begin with it showed just how high he was rated. "A great dancer with a brilliant future" was the actual way he was described — no empty praise in a country where standards are higher than anywhere in the world. But a curious sentence followed — particularly curious in a publication which was frankly intended as a piece of publicity. Nureyev had so far failed, the writer complained, to learn “that the leading role is after all only part of the artistic whole to which even the most gifted premier danseur must subordinate his individuality.”

Nureyev has the kind of individuality which is not easily subordinated, as anybody who has met him or seen him dance knows. It is this, in fact, which is his strength as an artist, making him something more than just an exceptionally gifted performer. Like the great names in all the arts he emanates a mysterious, strongly personal vitality, so that even his smallest movements seem to be expressing something big. Dance experts may praise his enormous leaps, his extraordinary turns and beats, his combination of softness and strength. But what lends him that extra something that appeals instantly to the most untrained eye is the potent dramatic quality we vulgarly know as “glamour.”

He is a quiet young man of 23, with something of the alert, elegant charm of Balanchine and the same suggestion of a wild catlike nature beneath a civilized manner. You might mistake him for a Parisian art student, though his slanting eyes and high cheekbones — reminiscent of Nijinsky’s — betray his Tartar origin.

His parents are poor country-folk in a remote village near Ufa beyond the Ural mountains, three days’ journey from Leningrad. Like many youngsters he joined a folk dance troupe, and was soon performing in the local town, Ufa. He was 17 — middle-age for a ballet student — before he went to Leningrad with the folk dance group and was invited to stay.

He set to work in Kirov Ballet School, with such success that within three years he was appearing with the company, and almost immediately in leading roles, From the start he insisted on his own methods. He entrusted himself to a single teacher, by the name of Pushkin, and rehearsed only with him. In the unhurried, commercially untroubled world of Russian bullet a year may go by in the preparation of a single role, and weeks to perfect a single performance. Nureyev likes to sink himself in a role like a Method actor. His foppish, slightly condescending interpretation of the Prince in the Kirov Sleeping Вeauty was a fine example. This approach fan be worked out only in private, not at committee meetings or group discussions, which he heartily dislikes.

Though he clearly suffers from his total isolation (he ejected himself into the western world with no plans, and fifty francs in his pocket), he seems outwardly quite undismayed. He exudes the courage — both moral and physical — which comes from long years of independence and lonelines, together (as he frankly admits) with a strong dose of obstinate egoism. “I do not like to be pressed,” he says.

He was not out of work long. Within a few weeks he had joined the de Cuevas Ballet Company and was dancing classical parts to enthusiastic audiences. With that company he performed in many parts of France, in Germany, Italy and Israel. In November he made his debut in London, at a gala matinee organized by Dame Margot Fonteyn, stopping the show with his “Black Swan” solo.

In December he joined Sonia Arova, Rosella Hightower, and Erik Bruhn in concert performances in Cannes and in Paris. On that first secret visit to England, he stayed five days with Dame Margot and discussed details of the London debut. The English ballerina loves a plot (she was imprisoned in Panama several years ago when her husband Senor de Arias was implicated in an attempted rising). Nureyev went unrecognized to performances at Covent Garden — I was astonished to find that the names of even the junior soloists were familiar to him from his study of ballet magazines — and he even attended a company class of the Royal Ballet, where Dame Margot introduced him by casually asking if a friend of hers, might join in at the class. His extraordinary feats soon had the other students applauding; but with characteristic British reticence they discreetly refrained from asking his name.

Off stage Rudolf Nureyev is modest, elegant, courteous and unpunctual. He moves with fastidious deliberation. There is something formidable behind his inscrutable gentle manner, and his physique, slight from a distance, is tough when you get close. His normal expression is one of faint amusement, and when over his shyness he laughs easily.

He has bright watchful eyes, and not much misses him. He found his way around London by bus from the first day he way there, and has definite views on what he has seen, which he expresses with a pleasing candor. He still thinks Russian ballet training the best in the world (and who would disagree?), but he admires very many things in the West. He finds some excellent things in the de Cuevas version of Sleeping Beauty in which he had been dancing; at Covent Garden he particularly admired Ashton's Symphonic Variations; he venerates the Danish dancer Erik Bruhn; and of all the choreography he has seen he rates that of Balanchine highest, though he much enjoyed Jerome Robbins’ N.Y.Export: Opus Jazz, which he saw in Paris.

One thing is certain. Nureyev is not just one more dancer of first-class talent. He is something much more rare. He is one of those strange, haunted artists that ballet throws up from time to time, dancers through whom some intense, urgent message seems to be passing. Such individual performers are not always the easiest to fit into organizations, or even into society. But what they have to contribute is unique.

END

NUREYEV ANSWERS QUESTIONS

By Franz Spelman

FS: Had you been planning to make this bolt for freedom, or did you just jump at the spur of the moment?

NUREYEV: What do you mean — freedom? And what do you mean by bolt? I didn't plan. I jumped. Suddenly I felt that things had been closing around me. But, mind you, I never had any politics in mind. Politics mean nothing to me. And I myself mean nothing to me. All I felt at that moment was that there might have been some danger that I couldn't dance any more — or at least not as much as I wanted. So I jumped to this side where I felt I still would be able to dance. Perhaps I was wrong. I’m not sure yet.

FS: Didn't you get enough opportunities in Leningrad?

NUREYEV: I didn't think so personally. Perhaps it is unjust to say this. I don t know. Perhaps I didn’t like the fact that, in the Kirov Theater. I was just a cog in an enormous, slow-moving organization. Sure, it's a wonderful body as far as training, teaching and the performances themselves are concerned. But everything is so slow.

FS: Didn't you have quite я career there already? When you did “La Bayadere,” in Paris, everyone believed that you were the featured star of the show.

NUREYEV: This might have looked so in Paris. In Leningrad I was just one of the 10 solo dancers, and one of the youngest at that. In Russia no one attains anything until he is well in the middle of his thirties. It may be that I'm too impatient. But I felt it was unbearable that I would have to wait for another 15 years until I was given all the opportunities, before I could be myself, before I could dance more than two to three times each month. I’ve felt like someone suffocating for too long.

FS: Do you think that your career will run more smoothly in the West?

NUREYEV: Well, at least this flashed through my mind when I ran for it. I already had a conception of what I could expect here before this. But I also knew that matters would be far from easy, and that much would depend upon me. Nothing has happened in the past few weeks to make me change my views.

FS: Why have you revealed so little about your background?

NUREYEV: Above all, in Russia we are just not accustomed to people putting their noses into one’s private life. Only the secret police does this, and it isn’t up to me to judge whether they are right or wrong in doing so. It should be enough if you judge me from my work on the stage. It shouldn't really matter whether, in my private life. I prefer vodka to tea, whether I'm a single child or have 20 brothers, or whether my father was a member of the Council of Ministers or a habitual drunk hack in the country. Besides, if I tell too much about my family and friends, matters might grow unnecessarily uncomfortable for them - especially if the press continues to distort what I say.

[FOTO] Those who have become acquainted with Nureyev personally are struck by his many-faceted personality, as reflected by the photos above.

[FOTO] IN ENGLAND: Early last fall, as house guest of Mme Roberto de Arias (also known as Dame Margot and as Margot Fonteyn), wife of Panama's Ambassador to England, Nureyev became acquainted with the English dance scene. On Nor. 2 he appeared at the Charity Data Matinee (See Dec, ’61 issue, p, 38), causing great excitement among England's balletomanes. He is currently in England again, following his U.S. TV appearance, to dance Albrecht to Miss Fonteyn’s Giselle with the Royal Ballet on Feb. 21, March l and 6.

FS: Couldn’t you tell us something about your background?

NUREYEV: All right, here are a few facts about my life. I’m an East Siberian, and I've some Tartar ancestry. There is nothing had in having Tartar ancestry, especially for a dancer. I was born in a small village the name doesn't matter - near Irkutsk, on Lake Baikal. My father taught me folk dancing when I was very young.

I then took up with a local group, and this is where my bаllet training began. It was a fine group, and so it was sent to Leningrad to perform, seven years ago. We played the Kirov Theater, and this is where Sergeyev - their bullet master saw me first. He immediately asked me whether I wanted to remain there. This was exactly what I wanted him to suggest, because that was why I came. I'd wanted to become a ballet dancer from the day I tried my first dance step. In Russia it goes like that. Before I came to Leningrad. I had seen the Kirov and the Bolshoi in the flesh, in the movies, on TV, and I had read everything about them I could lay my hands on. I also knew then that I didn't care to go to the Bolshoi. That’s too showy and vulgar.

FS: You make it sound easy.

NUREYEV: Don’t believe it was simple. I was a latecomer. A boor and a latecomer. First, I had to go to school, I was there a much shorter time than most of my colleagues. There was so much I didn't know, and also there was a lot I did better than anyone else. I made no friends. After I graduated, I always felt myself surrounded by people who didn’t want to let me go through to the top. In those four years, my entire stage repertory consisted only of seven parts. I do hope that now I will find a broader field.

FS: Aren’t you afraid of reprisals?

NUREYEV: Why should I be? I'm not important. And I’m not an enemy of the Soviet Union. I’ve told all this to the men of the Soviet Embassy in Paris. All one can blame me for is having taken premature advantage of the greater artistic freedom which I believe, ultimately, will be inevitable in the Soviet Union, too. There is a change of generations coming in the artistic world. Right now, the cultural reins are still in the hands of the people who cling to the theories of the past. But the cleavage between the young and old is growing. I just happened to be more impatient than the rest.

FS: Are you losing many privileges?

NUREYEV: Yes and no. Not financial. I never cared for money anyway. In Russia I made 2000 rubles a month, which is far less than the $8000 I rejected when I decided not to become a permanent member of the Cuevas Ballet. Yet, if I was looking for security alone, I would have been wiser to remain in Russia. Even though I didn't belong to that group of top artists in Russia who have everything, I had just as much as I wanted - a nice small apartment and a good phonograph to play my records. Here, in the West, I feel I’m going to ask for as much money as I can obtain because the amount of money one receives is what decides one’s worth.

FS: What do you think of the West, now that you have been here for a while?

NUREYEV: It is still far too early to make a judgment. What I've seen of France I didn't like very much. I didn’t like the way in which I was dished up as a sensation, and I resented the public curiosity about everything concerning my person.

Above all, I didn’t like the way the Cuevas people dressed me up like a Christmas tree - all bangles and beads. On the other hand, I’ve felt considerably calmer since coming to Germany. People were curious, too. But after they had a glance, they let me work.

FS: How would you define the difference between Russia and Western Europe?

NUREYEV: The West isn’t as separated from the Russian mind as one might assume. In the provincial parts, yes. But certainly not in Leningrad. This isn’t perhaps as valid for Moscow. We have a saying that the Muscovites are too concerned with looking at the navels of their inflated stomachs to see anything else.

But in Leningrad the presence of the West is never absent. It oozes through in many channels: the radio, visitors, a thousand other things. [p71] In Russia, art is taken far more seriously, the artists command more respect. Audiences are better in Russia. For them, the ballet is a major experience in their lives - or a major escape, if you want to put it this way. In Europe, though, art still remains very much the privilege of the wealthy. But this, despite all the flippancy and the amateurishness and the commercial exploitation, is compensated for by the liberties which are offered. In Russia, with all the opportunities given to concentrate on one's work, the real creative person is ultimately bound to arrive at a position where he just can’t develop further. This is perhaps the advantage of the West which counts most.

FS: Can you provide a sample of such Western achievements?

NUREYEV: I believe that much of what emerges from America in painting, literature which has always intrigued me - and in music - especially jazz - is a step ahead. And of course there are the innovations in the dance. I admire Jerome Robbins. I saw If West Side Story and I thought it was marvelous. I saw his Opus Jazz and I felt that this would be the kind of choreographic theme which I would like to approach myself. Of course, I also have some criticisms. With Jerome Robbins I have an important objection, and it may seem funny that it comes from a Russian. But I do feel that the one thing wrong with his work is that his choreography tends to be too abstract, too collective. Everything tends to negleet or to overpower the individual dancer. This is what always was done at the Kirov Theater, too.

FS: What are your plans for the future?

NUREYEV: I’m on my way to see the people of the Danish Ballet. Later on I shall go to London. From there, I hope to go to New York. Of course I would like to work under a man like Balanchine. And l certainly would like to appear at Covent Garden. But I don't want to go on anywhere in the circumstances which existed in Paris. I don't want to be considered as a freak, or as a curiosity. I want to retain my own dancer's identity. But now I'm aiming for it: my own identity - as a dancer, and later on as a choreographer and teacher - even if this would mean forming my own group.

FS: What would happen if you fail to achieve your identity?

NUREYEV: Frankly speaking I haven't thought about this. The West and I have given each other a chance. If we don't succeed, I may – perhaps - go back.

END

[ DANCE MAGAZINE March 1962]

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

August 13 in Music History

1655 Birth of German instrument maker Johann Christoph Denner in Leipzig.

1692 Birth of composer Anton Simon Ignaz Praelisauer.

1704 Birth of composer Lorenzo Fago.

1717 Birth of German composer Christoph Nichelsmann.

1721 Birth of composer Francis Ireland.

1742 Handel leaves Dublin for England to start oratorio season at Covent Garden.

1784 Birth of Italian mezzo-soprano Teresa Belloc-Giorgi.

1801 Birth of English baritone Henry Phillips in Bristol.

1817 Birth of composer Karoly Thern.

1820 Birth of English musicologist Sir George Grove in Clapham.

1826 Birth of English organist William T. Best in Carlisle.

1831 Birth of German conductor and composer Salomon Jadassohn.

1841 Death of German composer, conductor and cellist Bernhard Romberg.

1841 FP of Robert Schumann's Concert Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra, in Leipzig a Gewandhaus Orchestra rehearsal conducted by Felix Mendelssohn, with soloist Clara Schumann. It was revised as the first movement of his Piano Concerto in a, Op. 54.

1852 Birth of cellist Robert Hausmann in Rottleberode, Harz.

1865 Birth of American soprano Emma Eames in Shanghai, China.

1876 FP Wagner's Das Rheingold in Bayreuth complete version.

1878 Birth of composer Leonid Vladimirovich Nikolayev.

1879 Birth of English composer John Ireland in Inglewood, Bowdon,

1884 Birth of blind American violinist and composer Edwin Grasse in NYC.

1894 Birth of Russian composer Leonid Polovinkin in Kurgan.

1901 Birth of composer Ian Whyte.

1912 Birth of tenor Francesco Albanese.

1912 Birth of Spanish composer Francisco Escudero in Zarautz.

1912 Death of French composer Jules Massenet in Paris at age 70.

1913 Birth of Czech opera composer Ladislav Holobek in Prague.

1913 Birth of Russian opera composer Anatoly Vasilievitch Bogatyrev.

1916 Death of German conductor Fritz Steinbach in Munich.

1921 Birth of French conductor Louis Fremauxvin Aire-sur-la-Lys.

1926 Birth of mezzo-soprano Valentino Levko.

1929 Birth of composer Augustyn Bloch.

1930 Birth of composer Heino Jurisalu.

1930 Birth of American contralto Margareth Bence, in Kingston, NY.

1934 Birth of composer Leifur Thorarinsson

1937 Birth of American soprano Felicia Patricia Weathers in St.

1940 Birth of mezzo-soprano Gertrude Jahn.

1942 Birth of English soprano Sheila Armstrong.

1942 Birth of English composer Philip Goddard in Harrow Weald, Middlesex.

1942 Birth of American cellist, conductor Jerome Kessler.

1943 Death of soprano Jane Osborn-Hannah.

1944 Birth of American composer David Mahler.

1946 Birth of soprano Helena Dose.

1948 Birth of American soprano Kathleen Battle in Portsmouth Ohio

1949 Birth of Scotish baritone Gordon Sandison.

1955 Death of soprano Florence Easton.

1964 FP of Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 10, arranged by Deryck Cooke. London Symphony conducted by Berthold Goldschmidt.

1973 FP of Thea Musgrave's Viola Concerto at a London Proms Concert. Her husband, Peter Mark was the soloist.

1976 FP of Duke Ellington's ballet Three Black Kings by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and the Duke Ellington Orchestra conducted by Mercer Ellington. Performed posthumously at the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center in NYC.

1996 Death of American composer Louise Victoria Talma in Yaddo, NY.

1996 Death of American composer David Tudor.

2014 Death of Dutch flutist, musicologist and recorder virtuoso Franz Bruggen.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vaslav Nijinsky Masterpost

WIP

1894

amateur Hopak production in Odessa

Imperial Ballet School

supporting parts in classical ballets such as Faust, as a mouse in The Nutcracker, a page in Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake

command performances in front of the Tsar of Paquita, The Nutcracker and The Little Humpbacked Horse

selected by the great choreographer Marius Petipa to dance a principal role in what proved to be the choreographer's last ballet, La Romance d'un Bouton de rose et d'un Papillon. The work was never performed due to the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War.

The 1905 annual student show included a pas de deux from The Persian Market, danced by Nijinsky and Sofia Fedorova. Oboukhov amended the dance to show off Nijinsky's abilities, drawing gasps and then spontaneous applause in the middle of the performance with his first jump.

In 1906, he danced in the Mariinsky production of Mozart's Don Giovanni, in a ballet sequence choreographed by Michel Fokine. He was congratulated by the director of the Imperial Ballet and offered a place in the company although he was a year from graduation. Nijinsky chose to continue his studies. He tried his hand at choreography, with a children's opera, Cinderella, with music by another student, Boris Asafyev. At Christmas, he played the King of the Mice in The Nutcracker. At his graduation performance in April 1907, he partnered Elizaveta Gerdt, in a pas de deux choreographed by Fokine. He was congratulated by prima ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska of the Imperial Ballet, who invited him to partner her. His future career with the Imperial Ballet was guaranteed to begin at the mid-rank level of coryphée, rather than in the corps de ballet. He graduated second in his class, with top marks in dancing, art and music.

Nijinsky spent his summer after graduation rehearsing and then performing at Krasnoe Selo in a makeshift theatre with an audience mainly of army officers. These performances frequently included members of the Imperial family and other nobility, whose support and interest were essential to a career

Imperial Russian Ballet

He appeared with Sedova, Lydia Kyasht and Karsavina. Kchessinska partnered him in La Fille Mal Gardée, where he succeeded in an atypical role for him involving humour and flirtation. Designer Alexandre Benois proposed a ballet based upon Le Pavillon d'Armide, choreographed by Fokine to music by Nikolai Tcherepnin. Nijinsky had a minor role, but it allowed him to show off his technical abilities with leaps and pirouettes. The partnership of Fokine, Benois and Nijinsky was repeated throughout his career. Shortly after, he upstaged his own performance, appearing in the Bluebird pas de deux from the Sleeping Beauty, partnering Lydia Kyasht. The Mariinsky audience was deeply familiar with the piece, but exploded with enthusiasm for his performance and his appearing to fly, an effect he continued to have on audiences with the piece during his career.[18]

Undated

The Pharaoh's Daughter

Eunice

L'Oiseau d'Or

Mariinsky Theatre

1906

Don Giovanni (professional debut) (Anna Pavlova, Nijinsky)

1907

Le Pavillon d'Armide (Pavlova, Nijinsky, Pavel Gerdt)

1908

Le Roi Candaule

1909

1910

Le Talisman

1911

Giselle

Ballets Russes

1909

Le Pavillon d'Armide (Vera Karalli, Nijinsky, Mikhail Mordkin)

Prince Igor

Le Festin (suite of dances)

Les Sylphides (Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris) (Tamara Karsavina, Nijinsky, Pavlova, Alexandra Baldina)

Cléopâtre✅ (cast as the favourite slave of Cleopatra)

1910

Carnaval✅

Schéhérazade✅

Giselle✅

Les Orientales✅

July - L'Oiseau de feu✅

an orchestration of Grieg's Kobold, Op. 71, no. 3 for a charity ball dance

1911

Le Spectre de la rose✅

Narcisse✅

Sadko

Petrushka✅

Swan Lake

London - Royal Opera at Covent Garden - Season of Russian Ballet (22 July 1911) [x]

Le Pavillon d'Armide (as L'Esclave d'Armide)

Scheherazade (as The favourite Negro of Zobéide)

Les Sylphides (as Mazurka, Valse, and Valse Brillante)

1912

L'après-midi d'un faune✅

Daphnis et Chloé

Le Dieu bleu✅

Thamar

1913

Jeux✅

Le sacre du printemps✅

Tragédie de Salomé

1914

Les Papillons

La légende de Joseph

Le coq d'or

Le rossignol

Midas

2 March 1916 Saison Nijinsky (The Palace Theatre; London, England)

Les Sylphides

Le Spectre de la Rose

1915

Soleil de Nuit

1916

14 April 1916 Les Sylphides & Papillon (Metropolitan Opera)✅

Las Meninas

Kikimora

Till Eulenspiegel✅

2 notes

·

View notes