#copyfraud

Text

Good riddance to the Open Gaming License

Last week, Gizmodo’s Linda Codega caught a fantastic scoop — a leaked report of Hasbro’s plan to revoke the decades-old Open Gaming License, which subsidiary Wizards Of the Coast promulgated as an allegedly open sandbox for people seeking to extend, remix or improve Dungeons and Dragons:

https://gizmodo.com/dnd-wizards-of-the-coast-ogl-1-1-open-gaming-license-1849950634

The report set off a shitstorm among D&D fans and the broader TTRPG community — not just because it was evidence of yet more enshittification of D&D by a faceless corporate monopolist, but because Hasbro was seemingly poised to take back the commons that RPG players and designers had built over decades, having taken WOTC and the OGL at their word.

Gamers were right to be worried. Giant companies love to rugpull their fans, tempting them into a commons with lofty promises of a system that we will all have a stake in, using the fans for unpaid creative labor, then enclosing the fans’ work and selling it back to them. It’s a tale as old as CDDB and Disgracenote:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CDDB#History

(Disclosure: I am a long-serving volunteer board-member for MetaBrainz, which maintains MusicBrainz, a free, open, community-managed and transparent alternative to Gracenote, explicitly designed to resist the kind of commons-stealing enclosure that led to the CDDB debacle.)

https://musicbrainz.org/

Free/open licenses were invented specifically to prevent this kind of fuckery. First there was the GPL and its successor software licenses, then Creative Commons and its own successors. One important factor in these licenses: they contain the word “irrevocable.” That means that if you build on licensed content, you don’t have to worry about having the license yanked out from under you later. It’s rugproof.

Now, the OGL does not contain the word “irrevocable.” Rather, the OGL is “perpetual.” To a layperson, these two terms may seem interchangeable, but this is one of those fine lawerly distinctions that trip up normies all the time. In lawyerspeak, a “perpetual” license is one whose revocation doesn’t come automatically after a certain time (unlike, say, a one-year car-lease, which automatically terminates at the end of the year). Unless a license is “irrevocable,” the licensor can terminate it whenever they want to.

This is exactly the kind of thing that trips up people who roll their own licenses, and people who trust those licenses. The OGL predates the Creative Commons licenses, but it neatly illustrates the problem with letting corporate lawyers — rather than public-interest nonprofits — unleash “open” licenses on an unsuspecting, legally unsophisticated audience.

The perpetual/irrevocable switcheroo is the least of the problems with the OGL. As Rob Bodine— an actual lawyer, as well as a dice lawyer — wrote back in 2019, the OGL is a grossly defective instrument that is significantly worse than useless.

https://gsllcblog.com/2019/08/26/part3ogl/

The issue lies with what the OGL actually licenses. Decades of copyright maximalism has convinced millions of people that anything you can imagine is “intellectual property,” and that this is indistinguishable from real property, which means that no one can use it without your permission.

The copyrightpilling of the world sets people up for all kinds of scams, because copyright just doesn’t work like that. This wholly erroneous view of copyright grooms normies to be suckers for every sharp grifter who comes along promising that everything imaginable is property-in-waiting (remember SpiceDAO?):

https://onezero.medium.com/crypto-copyright-bdf24f48bf99

Copyright is a lot more complex than “anything you can imagine is your property and that means no one else can use it.” For starters, copyright draws a fundamental distinction between ideas and expression. Copyright does not apply to ideas — the idea, say, of elves and dwarves and such running around a dungeon, killing monsters. That is emphatically not copyrightable.

Copyright also doesn’t cover abstract systems or methods — like, say, a game whose dice-tables follow well-established mathematical formulae to create a “balanced” system for combat and adventuring. Anyone can make one of these, including by copying, improving or modifying an existing one that someone else made. That’s what “uncopyrightable” means.

Finally, there are the exceptions and limitations to copyright — things that you are allowed to do with copyrighted work, without first seeking permission from the creator or copyright’s proprietor. The best-known exception is US law is fair use, a complex doctrine that is often incorrectly characterized as turning on “four factors” that determine whether a use is fair or not.

In reality, the four factors are a starting point that courts are allowed and encouraged to consider when determining the fairness of a use, but some of the most consequential fair use cases in Supreme Court history flunk one, several, or even all of the four factors (for example, the Betamax decision that legalized VCRs in 1984, which fails all four).

Beyond fair use, there are other exceptions and limitations, like the di minimis exemption that allows for incidental uses of tiny fragments of copyrighted work without permission, even if those uses are not fair use. Copyright, in other words, is “fact-intensive,” and there are many ways you can legally use a copyrighted work without a license.

Which brings me back to the OGL, and what, specifically, it licenses. The OGL is a license that only grants you permission to use the things that WOTC can’t copyright — “the game mechanic [including] the methods, procedures, processes and routines.” In other words, the OGL gives you permission to use things you don’t need permission to use.

But maybe the OGL grants you permission to use more things, beyond those things you’re allowed to use anyway? Nope. The OGL specifically exempts:

Product and product line names, logos and identifying marks including trade dress; artifacts; creatures characters; stories, storylines, plots, thematic elements, dialogue, incidents, language, artwork, symbols, designs, depictions, likenesses, formats, poses, concepts, themes and graphic, photographic and other visual or audio representations; names and descriptions of characters, spells, enchantments, personalities, teams, personas, likenesses and special abilities; places, locations, environments, creatures, equipment, magical or supernatural abilities or effects, logos, symbols, or graphic designs; and any other trademark or registered trademark…

Now, there are places where the uncopyrightable parts of D&D mingle with the copyrightable parts, and there’s a legal term for this: merger. Merger came up for gamers in 2018, when the provocateur Robert Hovden got the US Copyright Office to certify copyright in a Magic: The Gathering deck:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/14/angels-and-demons/#owning-culture

If you want to learn more about merger, you need to study up on Kregos and Eckes, which are beautifully explained in the “Open Intellectual Property Casebook,” a free resource created by Jennifer Jenkins and James Boyle:

https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/openip/#q01

Jenkins and Boyle explicitly created their open casebook as an answer to another act of enclosure: a greedy textbook publisher cornered the market on IP textbook and charged every law student — and everyone curious about the law — $200 to learn about merger and other doctrines.

As EFF Senior Staff Attorney Kit Walsh writes in her must-read analysis of the OGL, this means “the only benefit that OGL offers, legally, is that you can copy verbatim some descriptions of some elements that otherwise might arguably rise to the level of copyrightability.”

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/01/beware-gifts-dragons-how-dds-open-gaming-license-may-have-become-trap-creators

But like I said, it’s not just that the OGL fails to give you rights — it actually takes away rights you already have to D&D. That’s because — as Walsh points out — fair use and the other copyright limitations and exceptions give you rights to use D&D content, but the OGL is a contract whereby you surrender those rights, promising only to use D&D stuff according to WOTC’s explicit wishes.

“For example, absent this agreement, you have a legal right to create a work using noncopyrightable elements of D&D or making fair use of copyrightable elements and to say that that work is compatible with Dungeons and Dragons. In many contexts you also have the right to use the logo to name the game (something called “nominative fair use” in trademark law). You can certainly use some of the language, concepts, themes, descriptions, and so forth. Accepting this license almost certainly means signing away rights to use these elements. Like Sauron’s rings of power, the gift of the OGL came with strings attached.”

And here’s where it starts to get interesting. Since the OGL launched in 2000, a huge proportion of game designers have agreed to its terms, tricked into signing away their rights. If Hasbro does go through with canceling the OGL, it will release those game designers from the shitty, deceptive OGL.

According to the leaks, the new OGL is even worse than the original versions — but you don’t have to take those terms! Notwithstanding the fact that the OGL says that “using…Open Game Content” means that you accede to the license terms, that is just not how contracts work.

Walsh: “Contracts require an offer, acceptance, and some kind of value in exchange, called ‘consideration.’ If you sell a game, you are inviting the reader to play it, full stop. Any additional obligations require more than a rote assertion.”

“For someone who wants to make a game that is similar mechanically to Dungeons and Dragons, and even announce that the game is compatible with Dungeons and Dragons, it has always been more advantageous as a matter of law to ignore the OGL.”

Walsh finishes her analysis by pointing to some good licenses, like the GPL and Creative Commons, “written to serve the interests of creative communities, rather than a corporation.” Many open communities — like the programmers who created GNU/Linux, or the music fans who created Musicbrainz, were formed after outrageous acts of enclosure by greedy corporations.

If you’re a game designer who was pissed off because the OGL was getting ganked — and if you’re even more pissed off now that you’ve discovered that the OGL was a piece of shit all along — there’s a lesson there. The OGL tricked a generation of designers into thinking they were building on a commons. They weren’t — but they could.

This is a great moment to start — or contribute to — real open gaming content, licensed under standard, universal licenses like Creative Commons. Rolling your own license has always been a bad idea, comparable to rolling your own encryption in the annals of ways-to-fuck-up-your-own-life-and-the-lives-of-many-others. There is an opportunity here — Hasbro unintentionally proved that gamers want to collaborate on shared gaming systems.

That’s the true lesson here: if you want a commons, you’re not alone. You’ve got company, like Kit Walsh herself, who happens to be a brilliant game-designer who won a Nebula Award for her game “Thirsty Sword Lesbians”:

https://evilhat.com/product/thirsty-sword-lesbians/

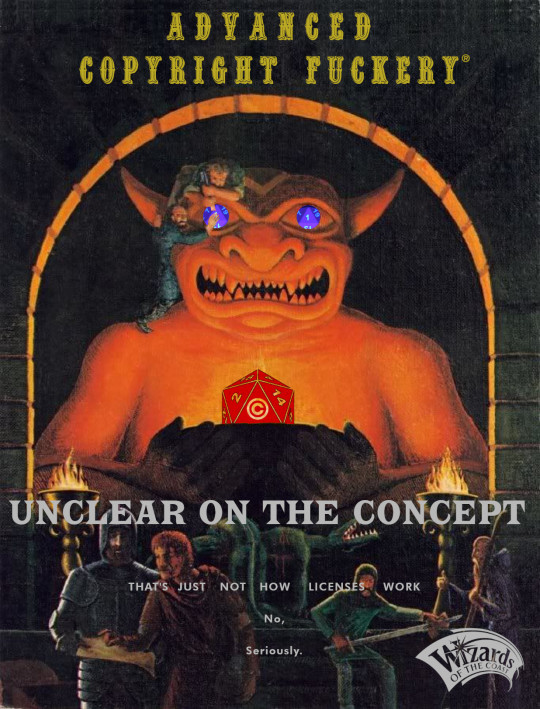

[Image ID: A remixed version of David Trampier's 'Eye of Moloch,' the cover of the first edition of the AD&D Player's Handbook. It has been altered so the title reads 'Advanced Copyright Fuckery. Unclear on the Concept. That's Just Not How Licenses Work. No, Seriously.' The eyes of the idol have been replaced by D20s displaying a critical fail '1.' Its chest bears another D20 whose showing face is a copyright symbol.]

#pluralistic#copyfraud#wizards of the coast#wotc#dungeons and dragons#d&d#ogl#open gaming license#eff#fair use#kit walsh#consideration#licenses

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

When you realize that someone had to literally commit copyright infringement to take the photo you are seeing right now...

from the wikipedia page for "Copyfraud"

14 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

That’s messed up.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italian government: "You took some photographs of ancient art!? PAY ME!"

Italian government: “You took some photographs of ancient art!? PAY ME!”

Among the monuments of Mithras is CIMRM 584, a relief showing the tauroctony, Mithras killing the bull. It was probably found in Rome, but is today in Venice, as part of the Zulian bequest. I came across a photograph online, and added it to the catalogue of Mithraic monuments.

CIMRM 584, tauroctony of Mithras from the museo archeologico at Venice.

While googling, I found another photograph at…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

The Big Tech companies argue that they have an appeals process that can reverse these overclaims, but that process is a joke. Instagram takedowns take a few seconds to file, but 28 months to appeal.

Cory Doctorow

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fake Copyright Strike Claim & Asking for Money ! What is Problem & Solution?

Fake Copyright Strike Claim & Asking for Money ! What is Problem & Solution?

Fake Copyright Strike Claim & Asking for Money! What is Problem & Solution? Fake Copyright Strike Claim & Asking for Money! What is Problem & Solution?

Hello friends, welcome to all of you, friends on WiFi Guruji dot com. In the last 2 years, we have become the most popular YouTube creator in India and work very hard and hard work mostly so that some can earn money or else Could grow your YouTube…

View On WordPress

#copyfraud#copyright claim youtube fair use#Fake Copyright Claim#false copyright claims penalty youtube#false copyright claims youtube#how long does a youtube copyright dispute take#how to solution for Fake Copyright Claim#how to solve problem of Fake Copyright Claim#is it illegal to falsely claim copyright#what happens when you dispute a copyright claim on youtube#what is Fake Copyright Claim#youtube copyright claim abuse

0 notes

Quote

Copyfraud is everywhere. False copyright notices appear on modern reprints of Shakespeare's plays, Beethoven's piano scores, greeting card versions of Monet's Water Lilies, and even the U.S. Constitution. Archives claim blanket copyright in everything in their collections. Vendors of microfilmed versions of historical newspapers assert copyright ownership. These false copyright claims, which are often accompanied by threatened litigation for reproducing a work without the owner's permission, result in users seeking licenses and paying fees to reproduce works that are free for everyone to use.

Jason Mazzone: Copyfraud. 2005 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=787244

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Deere's repair fake-out

Last week, a seeming miracle came to pass: John Deere, the Big Ag monopolist that — along with Apple — has led the Axis of Evil that killed, delayed and sabotaged dozens of Right to Repair laws, sued for peace, announcing a Memorandum of Understanding with the American Farm Bureau Federation to make it easier for farmers to fix their own tractors:

https://www.fb.org/files/AFBF_John_Deere_MOU.pdf

This is a move that’s both badly needed and long overdue. Deere abuses copyright law to force farmers to pay for official repairs — even when the farmer does the repair. That’s possible thanks to a practice called VIN locking, in which engine parts come with DRM that prevents the tractor from recognizing them until they pay hundreds of dollars for a John Deere technician to come to their farm and type an unlock code into the tractor’s console:

https://doctorow.medium.com/about-those-kill-switched-ukrainian-tractors-bc93f471b9c8

Like all DRM, VIN locks are covered by Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), a 1998 law that criminalizes distributing tools to bypass “access controls,” even if you do so for a lawful purpose (say, to fix your own tractor using a part you paid for). Violations of DMCA 1201 carry a penalty of 5 years in prison and a $500k fine — for a first offense.

This means that Deere owners are locked into using Deere for repairs, which also means that if Deere decides something isn’t broken, a farmer can’t get it fixed. This is very bad news indeed, because John Deere tractors are just computers in a fancy, mobile case, and John Deere is incredibly bad at digital security:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/23/reputation-laundry/#deere-john

That’s scary stuff, because John Deere is a monopolist, and a successful attack on the always-connected, networked tractors and other equipment it supplies to the world’s farmers could endanger the global food supply.

Deere doesn’t want to make insecure tractors, but it also doesn’t want to be embarrassed by security researchers who point out that its security is defective. Because security researchers have to bypass Deere tractors’ locks to probe their security, Deere can leverage DMCA1201 into a veto over who gets to warn the public about the mistakes it made.

It’s not just security researchers that Deere gets to gag: the company uses its repair monopoly to threaten farmers who complain about its business practices, holding their million-dollar farm equipment hostage to their silence:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/05/31/dealers-choice/#be-a-shame-if-something-were-to-happen-to-it

This all adds up to what Jay Freeman calls “felony contempt of business model,” an abuse of copyright law that allows a monopolistic corporation to reach beyond its own walls and impose its will on it customers, critics and competitors:

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

If Deere was finally suing for peace in the Repair Wars, well, that was wonderful news indeed — as I said, a seeming miracle.

But — like all miracles — it was too good to be true.

The MOU that Deere and the Farm Bureau signed is full of poison pills, gotchas, fine-print and mendacity, as Lauren Goode documents in her Wired article, “Right-to-Repair Advocates Question John Deere’s New Promises”:

https://www.wired.com/story/right-to-repair-advocates-question-john-deeres-new-promises/

For starters, the MOU makes the Farm Bureau promise to end its advocacy for state Right to Repair bills, which would create a repair system governed by democratically accountable laws, not corporate fiat. Clearly, Deere has seen the writing on the wall, after the passage in 2002 of Right to Repair laws in New York and Colorado:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/06/when-drm-comes-your-wheelchair

These two bills broke the corporate anti-repair coalition’s winning streak, which saw dozens of state R2R bills defeated:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/26/nixing-the-fix/#r2r

Deere’s deal-with-the-devil is a cynical ploy to brake R2R’s momentum and ensure that any repairs are carried out on Deere’s terms. Now, about those terms…

Deere’s deal offers independent repair shops access to diagnostic tools and parts “on fair and reasonable terms,” a murky phrase that can mean whatever Deere decides it means. Crucially, the deal is silent on whether Deere will supply the tools needed to activate VIN locks, meaning that farmers will still be at Deere’s mercy when they effect their own repairs.

What’s more, the deal itself isn’t legally binding, and Deere can cancel it at any time. Once you dig past the headline, the Deere’s Damascene conversion to repair advocacy starts to look awfully superficial — and deceptive.

One person who wasn’t fooled is sick.codes, the hacker who has done the most important work on reverse-engineering Deere’s computer systems, culminating in last summer’s live, on-stage hack of a John Deere tractor at Defcon:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/15/deere-in-headlights/#doh-a-deere

Shortly after the announcement, Sick.codes tweeted how the fine-print in the MOU would have prevented him from doing the work he’s already done (including “a direct stab at me lol”):

https://twitter.com/sickcodes/status/1612484935495057409

As with other instances of monopolistic, corporate copyfraud — like, say, the deceptive Open Gaming License — the John Deere capitulation is really a bid to take away your rights, dressed up as a gift of more rights:

https://mostlysignssomeportents.tumblr.com/post/706163316598407168/good-riddance-to-the-open-gaming-license

[Image ID: Hieronymus Bosch's painting, 'The Conjurer.' The Conjuror's shell-game table holds a small John Deere tractor that the audience of yokels gawps at. One yokel is wearing a John Deere hat. The conjurer is holding a wrench.]

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

6 Blockchain Business Use Cases You Should Know About

6 Blockchain Business Use Cases You Should Know About

The potential of the distributed ledger technology (DLT) — an umbrella term of which blockchain is the most popular kind — is enormous. Businesses can use blockchain to secure data, handle supply management, fight copyfraud, automate processes, and so on.

Blockchain may have a major impact on businesses thanks to its unique capabilities to enable transactions and operations without a single…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

How much of ERBs Mars/Venus stories are in the Public Domain? Because I remember reading somewhere that only the first five John Carter stories are in the Public domain, while the rights to the other five and the character himself are held by ERB Inc. Which has some shady history to it, like the time they went after Dynamite press for publishing John Carter comic books.

It depends on where you are. Almost all the Tarzan and Barsoom books are in the public domain in Australia, since the Aussies have shorter copyright duration. That’s why I tell people to look things up on Project Gutenberg Australia first.

Nothing has entered the public domain since 1998. The shrinking of the public domain due to increased duration for copyright is nothing short of criminal; it’s robbing the entire public of culture that should belong to all of us.

To understand the situation with Tarzan and John Carter, you have to understand the difference between two different types of intellectual property, copyright and trademark.

Copyright is:

Given to artistic works in a fixed medium (art, fiction, novels, movies, etc.)

Is designed to expire, so that works can become common property of our cultural heritage. The goal of copyright law is to provide a thriving public domain, not the other way around.

Is automatic from the time something exists in a fixed form, so you don’t have to register it.

There is no “use it or lose it,” you don’t lose it if you don’t enforce it strongly.

Trademark is:

Given to symbols or slogans that have no value in and of themselves, only because they are associated with a company or brand, like the Nike swoosh or the Coca-Cola logo. Trademark is an issue of consumer protection; only actual Coca-Cola can call itself Coca-Cola. The goal of trademark law is to prevent consumer confusion.

Does not protect the content of works, but only the title, and terms it can be sold with.

Is not designed to expire (is perpetual)

Requires registration

Can be lost if it isn’t enforced (this is why companies hate it when a brand becomes a word for something, like kleenex or xerox machine: it’s possible to lose the trademark if it is considered a generic term)

Let me be absolutely clear, here: The copyright on the first few Tarzan and John Carter of Mars books have expired, which means Tarzan and John Carter of Mars are in the public domain now and belong to all of us, as well as the situations, events, and concepts in the first few novels: Opar, La, Jane Porter, Dejah Thoris, the holy therns, the Green Men, etc.). For characters, copyright is fixed at the point of initial publication. This means anyone can write or create their own Tarzan or John Carter of Mars stories and use them for commercial purposes, even sell them. However, situations and characters introduced in the works still under copyright are still protected, which means you can’t use Queen Nemone and the City of Gold from Tarzan and the City of Gold, written in 1933 and still under copyright in the US and UK.

However...because the terms Tarzan and John Carter are still trademarked, still owned by ERB, Inc, you can make your own Tarzan book (since it’s out of copyright), but you can’t call it Tarzan, since that would interfere with ERB, Inc’s trademark. That’s why the Dynamite comics initially went with “Lord of the Jungle” and “Warlord of Mars” (we know what they mean).

Now, here’s where it gets shady: trademark is used to create a kind of perpetual, permanent copyright...which was never the intention. The Dynamite suit was totally baseless (again, these characters are in the public domain), and it’s something you see often when dealing with older characters: “copyfraud.” Yes, I said fraud, and I mean fraud. It’s a racket: pretending characters that now belong to all of us are still under ownership, enforced by the threat of litigation. Buck Rogers, Fu Manchu, Tarzan and John Carter should all, at this point, be public domain. Thankfully, the tide is starting to turn, particularly after the suit against the Conan Doyle heirs that said their supposed continued ownership of Sherlock Holmes was copyfraud.

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Mexico's New Copyright Law Crushes Free Expression

When Mexico's Congress rushed through a new copyright law as part of its adoption of Donald Trump's United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), it largely copy-pasted the US copyright statute, with some modifications that made the law even worse for human rights.

The result is a legal regime that has all the deficits of the US system, and some new defects that are strictly hecho en Mexico, to the great detriment of the free expression rights of the Mexican people.

Mexico's Constitution has admirable, far-reaching protections for the free expression rights of its people. Mexico’s Congress is not merely prohibited from censoring its peoples' speech -- it is also banned from making laws that would cause others to censor Mexicans' speech.

Mexico’s Supreme Court has ruled that Mexican authorities and laws must recognize both Mexican constitutional rights law and international human rights law as the law of the land. This means that the human rights recognized in the Constitution and international human rights treaties such as the American Convention on Human Rights, including their interpretation by the authorized bodies, make up a “parameter of constitutional consistency," except that where they clash, the most speech-protecting rule wins. Article 13 of the American Convention bans prior restraint (censorship prior to publication) and indirect restrictions on expression.

As we will see, Mexico's new copyright law falls very far from this mark, exposing Mexicans to grave risks to their fundamental human right to free expression.

Filters

While the largest tech companies in America have voluntarily adopted algorithmic copyright filters, Article 114 Octies of the new Mexican law says that "measures must be taken to prevent the same content that is claimed to be infringing from being uploaded to the system or network controlled and operated by the Internet Service Provider after the removal notice." This makes it clear that any online service in Mexico will have to run algorithms that intercept everything posted by a user, compare it to a database of forbidden sounds, words, pictures, and moving images, and, if it finds a match, it will have to block this material from public view or face potential fines.

Requiring these filters is an unlawful restriction on freedom of expression. “At no time can an ex ante measure be put in place to block the circulation of any content that can be assumed to be protected. Content filtering systems put in place by governments or commercial service providers that are not controlled by the end-user constitute a form of prior censorship and do not represent a justifiable restriction on freedom of expression." Moreover, they are routinely wrong. Filters often mistake users own creative works for copyrighted works controlled by large corporations and block them at the source. For example, classical pianists who post their own performances of public domain music by Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart find their work removed in an eyeblink by an algorithm that accuses them of stealing from Sony Music, which has registered its own performances of the same works.

To make this worse, these filters amplify absurd claims about copyright — for example, the company Rumblefish has claimed copyright in many recordings of ambient birdsong, with the effect that videos of people walking around outdoors get taken down by filters because a bird was singing in the background. More recently, humanitarian efforts to document war-crimes fell afoul of automated filtering.

Filters can't tell when a copyrighted work is incidental to a user's material or central to it. For example, if your seven-hour scholarly conference's livestream captures some background music playing during the lunch break, YouTube's filters will wipe out all seven hours' worth of audio, destroying the only record of the scientific discussions during the rest of the day.

For many years, people have toyed with the idea of preventing their ideological opponents' demonstrations and rallies from showing up online by playing copyrighted music in the background, causing all video-clips from the event to be filtered away before the message could spread.

This isn’t a fanciful strategy: footage from US Black Lives Matter demonstrations is vanishing from the Internet because the demonstrators played amplified music during their protests.

No one is safe from filters: last week, CBS's own livestreamed San Diego Comic-Con presentation was shut down due to an erroneous copyright claim by itself.

Filters can only tell you if a work matches or doesn't match something in their database — they can't tell if that match constitutes a copyright violation. Mexican copyright contains "limitations and exceptions" for a variety of purposes. While this is narrower than the US's fair use law, it nevertheless serves as a vital escape valve for Mexicans' free expression. A filter can't tell if a match means that you are a critic quoting a work for a legitimate purpose or an infringer breaking the law.

As if all this wasn't bad enough: the Mexican filter rule does not allow firms to ignore those with a history of making false copyright claims. This means that if a fraudster sent Twitter or Facebook — or a Made-In-Mexico alternative — claims to own the works of Shakespeare, Cervantes, or Juana Inés de la Cruz, the companies could ignore those particular claims if their lawyers figured out that the sender did not own the copyright, but would have to continue evaluating each new claim from this known bad actor. If a fraudster included just one real copyright claim amidst the torrent of fraud, the online service provider would be required to detect that single valid claim and honor it.

This isn't a hypothetical risk: "copyfraud" is a growing form of extortion, in which scammers claim to own artists' copyrights, then coerce the artists with threats of copyright complaints.

Algorithms work at the speed of data, but their mistakes are corrected in human time (if at all). If an algorithm is correct an incredible, unrealistic 99 percent of the time, that means it is wrong one percent of the time. Platforms like YouTube, Facebook and TikTok receive hundreds of millions of videos, pictures and comments every day — one percent of one hundred million is one million. That's one million judgments that have to be reviewed by the company's employees to decide whether the content should be reinstated.

The line to have your case heard is long. How long? Jamie Zawinski, a nightclub owner in San Francisco, posted an announcement of an upcoming performance by a band at his club in 2018, only to have it erroneously removed by Instagram. Zawinski appealed. 28 months later, Instagram reversed its algorithm's determination and reinstated his announcement — more than two years after the event had taken place.

This kind of automated censorship is not limited to nightclubs. Your contribution to your community's online discussion of an upcoming election is just as likely to be caught in a filter as Zawinski's talking about a band. When (and if) the platform decides to let your work out of content jail, the vote will have passed, and with it, your chance to be part of your community's political deliberations.

As terrible as filters are, they are also very expensive. YouTube's "Content ID" filter has cost the company more than $100,000,000, and this flawed and limited filter accomplishes only a narrow slice of the filtering required under the new Mexican law. Few companies have an extra $100,000,000 to spend on filtering technology, and while the law says these measures “should not impose substantial burdens" on implementers, it also requires them to find a way to achieve permanent removal of material following a notification of copyright infringement. Filter laws mean even fewer competitors in the already monopolized online world, giving the Mexican people fewer places where they may communicate with one another.

TPMs

Section 1201 of America's Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is one of the most catastrophic copyright laws in history. It provides harsh penalties for anyone who tampers with or disables a "technical protection measure" (TPM): massive fines or, in some cases, prison sentences. These TPMs — including what is commonly known as "Digital Rights Management" or DRM — are the familiar, dreaded locks that stop you from refilling your printer's ink cartridge, using an unofficial App Store with your phone or game console, or watching a DVD from overseas in your home DVD player.

You may have noticed that none of these things violate copyright — and yet, because you must remove a digital lock in order to do them, you could be sued in the name of copyright law. DMCA 1201 does not provide the clear, unambiguous protection that would be needed to protect free expression. One appellate court in the United States has explicitly held that you can be liable for a violation of Section 1201 even if you’re making a fair use, and that is the position adopted by the U.S. Copyright Office. Other courts disagree, but the net effect is that you engage in these non-infringing uses and expressions at your peril. The US Congress has failed to clarify this law and tie liability for bypassing a TPM to an actual act of copyright infringement — “you may not remove the TPM from a Netflix video to record it and put it on the public Internet (a copyright infringement), but if you do so in order to make a copy for personal use (not a copyright infringement), that's fine."

The failure to clearly tie DMCA 1201 liability to infringement has had wide-ranging effects for repair, cybersecurity and competition that we will explore in later installments of this series. Today, we want to focus on how TPMs undermine free expression.

TPMs give unlimited power to manufacturers. An ever-widening constellation of devices are designed so that any modifications require bypassing a TPM and incurring liability. This allows companies to sell you a product but dictate how you must use it — preventing you from installing your own apps or other code to make it work the way you want it to.

The first speech casualty of TPM rules is the software author. This person can write code -- a form of speech — but they cannot run it on their devices without permission from the manufacturer, nor can they give the code to others to run on their devices.

Why might a software author want to change how their device works? Perhaps because it is interfering with their ability to read literature, watch films, hear music or see images. TPMs such as the global DVB CPCM standard enforce a policy called the "Authorized Domain" that defines what is — and is not — a family. Authorized Domain devices owned by a standards compliant family can all share creative works among them, allowing parents and children to share among themselves.

But an "Authorized Domain family" is not the same as an actual family. The Authorized Domain was designed by rich people from the global north working for multinational corporations, whose families are far from typical. The Authorized Domain will let you share videos between your boat, your summer home, and your SUV — but it won't let you share videos between a family whose daughter works as a domestic worker in another country, whose son is a laborer in another state, and whose parents are migrant workers who are often separated (there are far more families in this situation than there are families with yachts and second homes!).

Even if your family meets with the approval of an algorithm designed in a distant board-room by strangers who have never lived a life like yours, you still may find yourself unable to partake in culture that you are entitled to. TPMs typically require a remote server to function, and when your Internet goes down, your books or movies can be rendered unviewable.

It's not just Internet problems that can cause the art and culture you own to vanish: last year, Microsoft became the latest in a long list of companies who switched off their DRM servers because they decided they no longer wanted to be a bookstore. Everyone who ever bought a book from Microsoft lost their books.

Forever.

Mexico's Congress did nothing to rebalance its version of America's TPM rules. Indeed, Mexico's rules are worse than America's. Under DMCA 1201, the US Copyright Office holds hearings every three years to grant exemptions to the TPM rule, granting people the right to remove or bypass TPMs for legitimate purposes. America's copyright regulator has granted a very long list of these exemptions, having found that TPMs were interfering with Americans in unfair, unjust, and even unsafe ways. Of course, that process is far from perfect: it’s slow, skewed heavily in favor of rightsholders, and illegally restricts free expression by forcing would-be speakers to ask the government in advance for permission through an arbitrary process.

Mexico's new copyright law mentions a possible equivalent proceeding but leaves it maddeningly undefined — and certainly does nothing to remedy the defects in the US process. Recall that USMCA is a trade agreement, supposedly designed to put all three countries on equal footing — but Americans have the benefit of more than two decades' worth of exemptions to this terrible rule, while Mexicans will have to labor under its full weight until (and unless) they can use this undefined process to secure a comparable list of exemptions. And even then, they won’t have the flexibility offered by fair use under US law.

Notice and Takedown

Section 512 of the US DMCA created a "notice and takedown" rule that allows rightsholders or their representatives to demand the removal of works without any showing of evidence or finding of fact that their copyrights were infringed. This has been a catastrophe for free expression, allowing the removal of material without due care or even through malicious, fraudulent acts (the author of this article had his New York Times bestselling novel improperly removed from the Internet by careless lawyers for Fox Entertainment, who mistook it for an episode of a TV show of the same name).

As bad as America's notice and takedown system is, Mexico's is now worse.

In America, online services that honor notice and takedown get a "safe harbor" — meaning that they are not considered liable for their users' copyright infringements. However, online services in the US that believe a user’s content is noninfringing may ignore it, and they are only liable at all if they meet the tests for “secondary liability" for copyright infringement, something that is far from automatic. If the rightsholder sues, the service may end up in court alongside their user, but the service can still rely on the safe harbor in relation to other works published by other users, provided they remove them upon notice of infringement.

The Mexican law makes it a strict requirement to remove content. Under Article 232 Quinquies (II), providers must honor all takedown demands by copyright owners, even obviously overreaching ones, or they face fines of UMA1,000-20,000.

Further, Article 232 Quinquies (III) of the Mexican law allows anyone claiming to be an infringed-upon rightsholder to obtain the personal information of the alleged infringer. This means that gangsters, thin-skinned public officials, stalkers, and others can use fraudulent copyright claims to unmask their critics. Who will complain about corrupt police, abusive employers, or local crime-lords when their personal information can be retrieved with such ease? We recently defended the anonymity of a person who questioned their religious community, when the religious organization tried to use the corresponding part of the DMCA to identify them. In the name of copyright, the law gives new tools to anyone with power to stifle dissent and criticism.

This isn't the only "chilling effect" in the Mexican law. Under Article 114 Octies (II), a platform must comply with takedown requests for mere links to a Web-page that is allegedly infringing. Linking, by itself, is not an infringement in the United States or Canada, and its legal status is contested in Mexico. There are good reasons why linking is not infringement: It’s important to be able to talk about speech elsewhere on the Internet and to share facts, which may include the availability of copyrighted works whose license or infringement status is unknown. Besides that, Web-pages change all the time: if you link to a page that is outside of your control and it is later updated in a way that infringes copyright, you could be the target of a takedown request.

Act now!

If you are based in Mexico, we urge you to participate in R3D's campaign "Ni Censura ni Candados" and send a letter to Mexico's National Commission for Human Rights to asking them to invalidate this new flawed copyright law. R3D will ask for your name, email address, and your comment, which will be subject to R3D's privacy policy.

from Deeplinks https://ift.tt/302EoJz

0 notes

Text

The more I use Apple, the more they suck

The two biggest reasons why Apple sucks would be their price, and the fact that they honestly think it’s their job to control you.

I’m not kidding.

Time & time again I’ve tried to save an image or copy some text from a webpage -- usually as a cite for some online argument -- and Apple won’t allow it. They think they need to police you. They think they should police you and they do police you.

The phone is worse than the computer and the computer is pretty awful with this policing you...

This is stupid. Honestly, I just plain don’t care about massive corporations. Their “Copyrights” are important to me... ESPECIALLY when they so often commit CopyFraud, claiming copyright violations when there are none.

You? Good luck. Nobody will protect you and your rights. Everything is geared towards “Protecting” massive corporations.

Why spend over $1,000 on a great piece of hardware just so it can police you in a ridiculous, inappropriate manner?

#Copyright#copyfraud#Apple#big brother#going too far#abuse#Apple is the guilty party in an abusive relationship#controlling#unreasonable

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Link

The incident was a wake-up call for Marina, who is quitting Youtube altogether, noting that it has become a place that favors grifters over creators. She's not wrong, and it's worth looking at how that happened.

Content ID was created to mollify the entertainment industry after Google acquired Youtube. Google would spend $100m on filtering tech that would allow rightsholders to go beyond the simple "takedown" permitted by law, and instead share in revenues from creative uses.

But it's easy to see how this system could be abused. What if people falsely asserted copyright over works to which they had no claim? What if rightsholders rejected fair uses, especially criticism?

In a world where the ownership of creative works can take years to untangle in the courts and where judges' fair use rulings are impossible to predict in advance, how could Google hope to get it right, especially at the vast scale of Youtube?

The impossibility of automating copyright judgments didn't stop Google from trying to perfect its filter, adding layers of complexity until Content ID's appeal process turned into a cod-legal system whose flowchart looks like a bowl of spaghetti.

4 notes

·

View notes