#cabbyl Ushtey

Text

Oops, my hand slipped and I started a part 2 of Ushtey Yugi fic.

If you like Kelpies, and horses, or just mythological creatures in love with a human, then please go check out my fic, “So Where is the Line Drawn.” I wrote it as a secret santa gift, and it was such a blast to write.

#yugioh#yugioh duel monsters#ushtey#cabbyl-ushtey#kelpie#yugi mutou#yami yugi#Atem#fanfiction#fanfic#puzzleshipping

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mythological Horse Tournament

Contestants list - Submissions are closed.

Group 1

Bäckahäst (Norse Folklore) - Eliminated Round 3

Kelpie (Scottish Folklore) - Eliminated Round 1

Hippocampus (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 2

Cabbyl-ushtey (Manx Folklore) - Eliminated Round 1

Ceffyl Dŵr (Welsh Folklore)

Each-uisge (Scottish Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1 Bonus

Four Horses of the Apocalypse (Christian Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Mari Lwyd (Welsh Folklore) - Eliminated Round 2

Tikbalang (Philippine Folklore) - Eliminated Round 1

Longma (Chinese Mythology) - Eliminated Round 3

Orobas (Christian Mythology/Demonology) - Eliminated Round 2

Balaam's Donkey (Jewish mythology, Christian Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Zodiac Horse (Chinese Mythology) - Eliminated Round 4

Zodiac Sagittarius (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Group 2

Nessus (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Chiron (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 2

Arion (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Black Horse (Canadian Folklore) - Eliminated Round 2

Árvakr and Alsviðr (Norse Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Sleipnir (Norse Mythology) - Eliminated Round 4

Hrímfaxi (Norse Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Skinfaxi (Norse Mythology) - Eliminated Round 3

Trojan Horse (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Uchchaihshravas (Hindu Mythology) - Eliminated Round 2

Uffington White Horse (English Folklore) - Eliminated Round 2

Balius and Xanthus (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 3

Pegasus (Greek Mythology) - Eliminated Round 1

Unicorn (Possibly Asian???)

Submissions are closed.

Requirements are:

- Their primary form must be at least 50% horse or more (this means shapeshifters are welcome but they must primarily be depicted as a horse or horse-esk.)

- They must be depicted in Folklore or Mythology in one way or another.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Glashtyn (Manx English: glashtin, glashtan [ˈɡlaʃθən] or glashan; Manx: glashtin or glashtyn [ˈɡlaʃtʲənʲ]) is a legendary creature from Manx folklore.

The glashtin is said to be a goblin that appears out of its aquatic habitat, to come in contact with the island folk; others claim it takes the shape of a colt, or equate it to the water horse known locally as cabbyl-ushtey. Yet another source claims the glashtin was a water-bull (tarroo-ushtey in Manx), half-bovine and half-equine.

Some tales or lore recount that it has pursued after women, ending in the stock motif of escape by cutting loose the skirt-hem, although in one modern version her escape is achieved by a rooster's crowing; in that tale the glashtin pretends to be a handsome man but is betrayed by his horse-ears.

The word glashtin is thought to derive from Celtic glais (Old Irish: glais, glaise, glas), meaning "stream", or sometimes even the sea.

Recent literature embracing this notion claims that the equine glashtin assumes human form at times, but betrays his identity when he fails to conceal his ears, which are pointed like a horse's.

One modern fairy tale relates how a fisherman's daughter living in Scarlett outwitted the foreign-tongued "dark and handsome" stranger whom she recognized as glashtin by his horse's ears. She knew she was in peril because according to lore, the glashtin had the ill habit of transforming into a "water-horse" and dragging women to sea

1 note

·

View note

Text

Water Horses: more than just kelpies

Water horses as a mythological creatures appear in Celtic and Scandinavian folklore. They're shape-shifting water spirits, who lure and drag their unsuspecting victims to their demise. However, there are many types of water horses, differing from each other not only by places of origin but in behaviour. What they all have in common is: inhabiting bodies of water and taking the form of a horse.

I'll try my best to present the best known and least known ones, in simple to understand fashion. In advance, I want to apologies for any mistakes made. I'm only one person doing this partly as a story research and partly as my love/fascination for those creatures. I advise taking this post as a starting point and encourage to look into the folklore yourselves. Also, I apologies for any grammatical mistakes, English is my second language.

Kelpie

Location: Scotland

Other names: x

Body of water: streams and rivers

the best known of all water horse

appears as a powerful and beautiful black, dark grey or white horse, with reversed hooves and, in some sources, equipped with a bridle and sometimes a saddle

if the kelpie was already wearing a bridle, "exorcism" might be achieved by removing it, which would be endowed with magical properties, like healing, and if brandished towards someone, was able to transform that person into a horse or pony

can shape-shift into a human figures, with water weeds in hair, such as old wizened man; rough, shaggy man; handsome young man wearing a silver necklace, which was its bridle; or a tall woman dressed in green

in the form of handsome young man, said to seeks "human companionship" and will woo a pretty young girl which is determined to take for its wife

if mounted, its skin becomes adhesive, in stories where a hand or a finger got stuck to the creature, the only way to break free was to cut it off

most stories say they only drown their victims, but some say they tear them apart and devour them, leave the entrails to washout to the water's edge

could entice victims onto its back by singing

some sources say, it can have a offspring with a horse, which would be impossible to drown and had ears shorter then normal

could be k*lled with a silver bullet or heated iron, and after dying, it’ll turn into turf and soft mass, like jellyfish

could be tamed with well placed halter, some sources say in should have sign of a cross on it

the noise a kelpie's tail makes when it entered water sounds like thunder

its howls and wails, as a warning of approaching storms

Each-uisge

Location: Scotland, Ireland, Isle of Man

Other names: each-uisce/aughisky/ech-ushkya (Irish), cabyll-ushtey (Manx)

Body of water: sea, sea lochs and fresh water lochs

the name means "water horse", literally

has been described as "perhaps the fiercest and most dangerous of all the water-horses", being unpredictable in nature

can shape-shift into fine horse, pony, a handsome man (water weeds, sand or mud in hair) or an enormous bird (such as a boobrie/great auk)

tears apart and devours the entire body of its victim, except for the liver, lungs or heart (depending on the source), and some times pieces of clothing are also present

preys not only on humans but also cattle and sheep

could be lured out off the water by the smell of roasted meat

can be k*lled with red-hot iron and after being k*lled, leaves jelly-like substance

repelled by silver and fire

sometimes comes out of the water to gallop on land and, despite the danger, if caught and tamed then it will make the finest of steeds

most likely to come out in November

can be ride safety on interior land as long as they don't smell or gets a glimpse of water

because of their pr*datory hunger, they may even turn on their own kind, if the scent of a human rider is strong enough on the monster's body

Ceffyl Dŵr

Location: Wales

Other names: x

Body of water: mountain pools, waterfalls and seashore (few sources)

most stories say they're fresh water but some sources say there is a salt water version, differing mostly in colour

its characterisation depends on the region, in North Wales its represented as being rather formidable with fiery eyes and a dark forbidding presence, while in South Wales its seen more positively as, at worst a cheeky pest to travellers and at best, luminous, fascinating and sometimes a winged steed

appears as a pony or cob sized horse, dappled grey or sand colour, with hooves facing backwards; or large chestnut or piebald horse

though it appears solid, it can evaporate into mist or grown wings

some sources say, it could transform into frogs

can k*ll its victims by trampling them on the pathways they frequent; or by convincing someone to ride them, only to drown them; or fly them into the air only to turn to mist, dropping the unfortunate rider to his death

like with kelpies, they can be tamed by use of a well placed bridle, though it’s much harder, due to their ability to turn intangible

in some sources its connected with sea-storm: appearing with sea-foam white coat in storm seasons; dapple, grey or white, clumsily stomping about in the ocean waves prior to the storm (possibly brewing up the very storm its sighting precedes); and as large chestnut or piebald horse trotting along the coast after storm

Nykur

Location: Iceland

Other names: x

Body of water: lake, river, stream and sea

appears as a grey horse with backwards hooves and ears

could change itself into all forms, living or dead, e.g. lambswool or peeled barley

repelled by speaking its name or a synonyms of it (Nennir, Nóni, Vatnaskratti (“water demon”) or Kumbur)

appears on the lake-shore, with half its body in the water, and looks to be quite tame to its unsuspecting victims

if mounted, its skin becomes adhesive and its will ride into the water and drown its victim

its neighing is said to sound like ice cracking

could breed with a horse (giving birth like a normal mare, albeit in the water), its offspring were indistinguishable from those of a normal horse but had a tendency to lie down when splashed with water or when led through belly-deep water

Tangie

Location: Shetland Islands, Orkney Islands

Other names: tongie

Body of water: fresh and salt water

the name comes from 'tang', which comes from Old Norse "þang" meaning 'seaweed' (probably referring to seaweed of genus Fucus)

appears as a coarse-haired, apple-green pony or a black horse with seaweed or shells in its mane

in other forms, appears as an aged man or merman, also covered in seaweeds

known for terrorizing lonely travellers, especially young women on roads at night near the lochs, whom it will abduct and devour under the water

said to be able to cause derangement in humans and animals

best known for playing a major role in the Shetland legend of Black Eric, a sheep rustler

Nuggle

Location: Shetland Islands, Orkney Islands (few mentions)

Other names: neugle, njogel, nuggie, noggle, nogle, nygel, shoepultie/shoopiltee

Body of water: rivers, streams and lochs, beside watermills

nocturnal

always male, appearing as a attractive, generously fed and well-conditioned (Shetland) pony or horse, with wheel-like tail which it hides between its back-legs or arched over its back, and sleek coat from a deep bluish-grey through to a very light, almost white, grey

can take many forms, but never of a human

never strays very far from water

fairly gentle disposition, being more prone to playing pranks and making mischief rather than having malicious intents, like stopping the watermill's wheel

some stories state, only magical beings called Finns (Finfolk) were able to ride a nuggle without coming to any harm

Bäckahäst

Location: Scandinavian

Other names: brook horse

Body of water: rivers, lakes and ponds

appears as a majestic white (sometimes with spotted sides) horse

appears particularly during foggy weather

could be harnessed and made to plough, either because it was trying to trick a person or because the person had tricked the horse into it

Cabyll-Ushtey

Location: Isle of Man, Ireland

Other names: glashtyn, cabbyl-ushtey, capall uisce (possibly Irish or Old Irish)

Body of water: sea

there are very few tales about it

very similar to each-uisge, but not as dangerous

appears as a pale grey horse, but capable of change into a young man

mostly known for seizing cows and tear them to pieces, stampeding horses, and stealing children

If there are any mistakes or missing informations or questions, feel free to ask.

#water horse#kelpie#each-uisge#capaill uisce#mythology#ceffyl dwr#celtic mythology#scandinavian mythology#scottish mythology#irish mythology#welsh folklore#nykur#tangie#nuggle#cabyll-ushtey

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kelpie

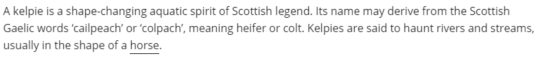

A kelpie is a shape-changing aquatic spirit of Scottish legend. Its name may derive from the Scottish Gaelic words ‘cailpeach’ or ‘colpach’, meaning heifer or colt. Kelpies are said to haunt rivers and streams, usually in the shape of a horse.

But beware…these are malevolent spirits! The kelpie may appear as a tame pony beside a river. It is particularly attractive to children – but they should take care, for once on its back, its sticky magical hide will not allow them to dismount! Once trapped in this way, the kelpie will drag the child into the river and then eat him.

These water horses can also appear in human form. They may materialize as a beautiful young woman, hoping to lure young men to their death. Or they might take on the form of a hairy human lurking by the river, ready to jump out at unsuspecting travellers and crush them to death in a vice-like grip.

The sound of a kelpie’s tail entering the water is said to resemble that of thunder. And if you are passing by a river and hear an unearthly wailing or howling, take care: it could be a kelpie warning of an approaching storm.

But there is some good news: a kelpie has a weak spot – its bridle. Anyone who can get hold of a kelpie’s bridle will have command over it and any other kelpie. A captive kelpie is said to have the strength of at least 10 horses and the stamina of many more, and is highly prized. It is rumoured that the MacGregor clan have a kelpies bridle, passed down through the generations and said to have come from an ancestor who took it from a kelpie near Loch Slochd.

The kelpie is even mentioned in Robert Burns’ poem, ‘Address to the Deil’:

“…When thowes dissolve the snawy hoord

An’ float the jinglin’ icy boord

Then, water-kelpies haunt the foord

By your direction

And ‘nighted trav’llers are allur’d

To their destruction…”

A common Scottish folk tale is that of the kelpie and the ten children. Having lured nine children onto its back, it chases after the tenth. The child strokes its nose and his finger becomes stuck fast. He manages to cut off his finger and escapes. The other nine children are dragged into the water, never to be seen again.

There are many similar tales of water horses in mythology. In Orkney there is the nuggle, in Shetland the shoopiltee and in the Isle of Man, the ‘Cabbyl-ushtey’. In Welsh folklore there are tales of the ‘Ceffyl Dŵr’. And in Scotland there is another water horse, the ‘Each-uisge’, which lurks in lochs and is reputed to be even more vicious than the kelpie.

So next time you are strolling by a pretty river or stream, be vigilant; you may be being watched from the water by a malevolent kelpie…

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shape-Shifting Part 1: Transfiguration and Creatures in the Harry Potter Books and European Lore

Animagi, werewolves, Transfiguration… all those shape-shifting forms appear in the Harry Potter series. They can be voluntary or not, linked to a spell, a curse/disease or to the sheer will of the shape-shifter, but they are always quite spectacular. Werewolves are part of the folklore in the northern hemisphere. But what about Animagi? Are shape-shifters a mere figment of Rowling’s imagination or are there shape-shifter stories in different cultures around the world? The answer is definitely the second option, and here are some examples (I can’t promise this paper to be short, I’m afraid :( … However, I can safely promise I won’t take examples from Cursed Child. )

I’ll start with a review of what shape-shifting means in Rowling’s novels, before going for a little tour of some cultures I want to explore regarding shape-shifting.

In the Harry Potter books and Fantastic Beasts-the film

To start with, let’s consider the types of shape-shifting appearing in Rowling’s books: Werewolves, Animagi, Metamorphmagi, Transfigured people, Boggarts, Kelpies, Veela. For the creatures, I’ll try and give a short -snorts- account of the image Muggles have of them, in their folklore.

Werewolves were already discussed a bit in other papers on this blog, so let’s leave them out of this one. For the rest, here goes:

1. Use of a Spell or a Potion

Transfiguration allows the wizard to change the shape of a fellow human into that of another animal, like Moody did with Draco when he turned the latter into a ferret, or into that of another human being. This is a means of shape-shifting using a spell, obviously. The first ever dated record of human Transfiguration was the one happening during a Quidditch match in 1473, when a Chaser was turned into a polecat. Of course, that kind of transformation had happened before. Take Circe, for instance, who was famous for turning sailors into pigs. She lived thousands of years ago. Some examples are more recent, like the one of Gellert Grindelwald, who was superskilled at Transfiguration, and lived as MACUSA Auror Percival Graves in 1926 New York.

Transfiguring someone into an animal would cause that person to become an animal fully, not retaining one ounce of humanity, meaning that they could perform no magic of their own, and would need the mediation of another wizard to get back to their human form (I wonder what happens to their clothes and especially to their wand during that time, and also if the one who transfigured the wizard would then become master of the wand, since it sort of defeated its owner…).

Transfiguration in the case of Animagi is going to be dealt with later, because it’s a different form of Transfiguration than just casting a spell. Transfiguration spells are numerous, according to various sources. However, the books don’t mention the spells per se, so I won’t list them here.

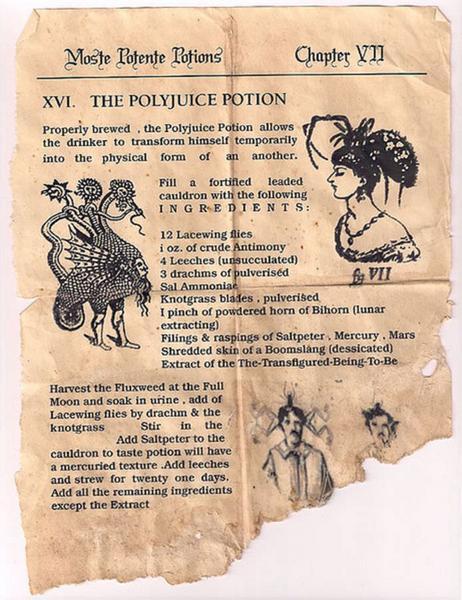

There are also examples of humans transforming themselves into humans, by means of Polyjuice Potion. Harry, Ron and Hermione used it in Chamber of Secrets to sneak into the Slytherin Common Room, and they also did use it in Deathly Hallows to enter the Ministry of Magic while trying to retrieve Slytherin’s locket from Umbridge, while trying to get food when they were on the run and finally when breaking into Gringotts to get Hufflepuff’s cup from Bellatrix Lestrange’s vault. In Goblet of Fire, Barty Crouch Jr. drank it all year round to impersonate Alastor Moody, whom he kept secured in a trunk all the time to get hair for his potion. We also know that Draco Malfoy made Crabbe and Goyle drink it and turned them into girls while they were keeping watch outside the Room of Requirement in Half-Blood Prince. Finally, at the beginning of Deathly Hallows, six people turn into Harries so as to keep danger -relatively- at bay while moving Harry from Privet Drive to the Burrow. Rowling made quite a use of Polyjuice. And as far as I know, I might have forgotten occurrences.

I have no recollection of any other potion in the books that would allow the drinker to change form. Since it’s considered Dark Magic, it’s only consistent it would be so. After all, the recipe for the Polyjuice Potion is found in a book called Moste Potente Potions, that is kept in the Restricted Section of the Hogwarts Library, because of all the gruesome stuff it contains, according to Hermione. Shape-shifting is not legal in the wizarding world, unless you’re a registered Animagus (see next paper). I can understand why there’s no more potions about that.

The use of a spell or a potion to change someone’s appearance is not common in cultures around the world - at least not to my knowledge; if you know something, tell me. It’s a pretty artificial way of achieving shape-shifting, and it is restricted to myths and legends.

2.Creatures

Form-changing creatures are more common, even outside the wizarding world. According to Newt Scamander (and I’m sticking to book canon here), there aren’t many shape-shifters among the Magical Creatures. In Fantastic Beasts And Where to Find Them, Scamander mentions only the Kelpie. In the Harry Potter series we come across a couple of other creatures, namely the Boggart and the Veela. It’s strange that they aren’t mentioned in Fantastic Beasts, at least for the Boggart, since it’s definitely a beast (maybe it’s because nobody knows its true shape). As for the Veela, it’s a Being, which accounts for its being left out of the book.

Reminder: the Ministry of Magic has a classification for Creatures. It goes from X (boring) to XXXXX (known wizard-killer and impossible to domesticate).

a. Kelpies

According to Newt Scamander, the Kelpie is a British and Irish water-demon, classified as XXXX by the Ministry of Magic. That means a skilled and trained wizard could deal with a Kelpie. It can change its shape to lure its preys into water, and the shape it takes the most often is that of a horse. It doesn’t take much to differentiate that horse from a regular Equus sp. because the mane of the horse-Kelpie is made of bulrushes. According to Muggle folklore, the hooves of the horse-kelpie are inverted compared to those of a regular Equus sp, and in Aberdeenshire, the mane is made of snakes. It is also said that if a Kelpie takes the shape of a human, then it’s betrayed by his hair being mixed with seaweed.

In his book, Scamander describes the festine that takes place at the bottom of the waters as quite gruesome because the entrails of the victim end up floating on the surface, or, according to legend, are thrown on the shore. Very nice. Sounds like the Kelpie’s Burp.

Still according to Scamander, you can render the horse-Kelpie tame by using and bridle jointly with a Placement Charm. However, it requires skill.

The world’s most famous Kelpie is the so-called-by-Muggles Loch Ness Monster. It was discovered to be a Kelpie when it was witnessed to turn into an otter to escape a crowd of Muggles. Every Scottish bit of water has a kelpie story attached to it. :)

Kelpies aren’t an invention of Rowling’s. They are part of the British lore. In Scotland, where the word originates from (first written records of the name back in the second half of the 17th century), Kelpies are apparently small, roundish, shape-shifting water fairies. They are said to usually appear as grey horses who lure their preys onto their backs, dive deep into the waters and devour their preys. Those creatures - or similar ones - appear all over the British Isles, with various names according to the region they are in: Each-Uisge in Ireland, Cabbyl-Ushtey on the Isle of Man, Shoney in Cornwall, Ceffyl Dwr in Wales, Nuggies in the Shetlands and Tangies on the Orkneys. Moreover, similar creatures are observed in Scandinavia, for instance (the Swedish Backhäst), or even as far as Southern America and Australia.

The Scottish Kelpie was said to lure people by crying for help, which led people to deny rescue to people drowning or trapped on islands if they thought they were kelpies crying. That, of course, led to the actual people dying. Near Fife, Scotland, the Kelpie is said to make a dreadful roaring before a boat was lost at sea.

In Scotland, apparently, the most usual transformations of the Kelpie are into a horse or a handsome young lad (rarely a lass). Yet Nessie is a Sea-Serpent :P

Lord I just found out something in a book called ‘The Fabled Coast’ (references below, naturally): Newt Scamander wasn’t an old loony when telling about bits of guts floating after the Kelpie’s repast. Actually, a paragraph about Lochboisdale, Western Islands, Scotland, tells the reader that exact gory bit of the legend. Kelpie-researchers go so far as to make a difference between sea-water demons, which they call Water-Horses, and fresh-water demons, which they call Kelpies. This apparently was a huge debate involving famous writers like Sir Walter Scott in the 19th century. The dispute is still not closed today… In that paragraph about Lochboisdale, the author also says that most people don’t give a bit of toast about that and call all those creatures Kelpies. I’ll also summarize the tale told in that chapter about the Kelpie. The narrative frame is the usual one, but still…

In Lochboisdale lived a widowed man and his daughter. The man married again and the stepmother and stepdaughter moved in. As usual, the stepmother was a mean old hag who gave all the dirty work to her husband’s daughter and let hers flirt all day.

One day that the girl was fishing at sea and catching nothing to save her life, the Kelpie appeared in front of her as a good-looking young man. He offered her help and they filled the boat with fish, because, he said, he knew about her misfortunes and had fallen in love with her. However, when the lass found out that her rescuer was a Water-Horse, she didn’t want anything to do with him anymore and he had to go back to his underwater realm.

Some time later, an assembly was held in the village and the Water-horse told his fellow kelpies he was going to bring a mortal amongst them. So he went to the dance, richly attired, looking handsomer than ever. Seeing him, the stepdaughter was so besotted that she clung to him all night, to the great pleasure of the Water-horse. He then lured her to the beach, and before she was aware the stepdaughter was invited to yet another ball, of which she was the main guest. Nobody heard anything about her on the land anymore. Romantics believe it was a way for the Water-horse to help his beloved have a better life. Realists think he wanted food.

Other tales include children, who try and mount the Kelpie, but as soon as their hand touches the creature, it gets stuck. If the kid cuts off his fingers or hand he might escape. Otherwise, it’s death and guts on the water edge. In some tales the Kelpie actually chooses a mortal life and marries the belle he loved, after trials and all that such a tale requires, naturally. Yet in other accounts, the Kelpies are reckoned to have great strength and when tamed they are used to carry milestones and plough fields. When released, though, they sometime issue a curse and some families are believed to have died out following such a malediction.

In Wales there’s part of the tale Newt Scamander relates in his book, namely the bit about the taming of the Horse-kelpie. There are several tales about Ceffyl-Dwr (see picture above; source: https://imgur.com/gallery/r5NYu ) being caught and used as farm-horses, and inevitably at some point the bridle falls and the Ceffyl-Dwr returns to the sea, sometimes dragging plough and farmer behind him. The Ceffyl-Dwr was sometimes seen plunging up and down into the sea like a dolphin, which makes it more an elemental beast than a water-demon. That’s a difference between the Scottish Kelpie and the Welsh Ceffyl-Dwr, and goes against Scamander’s putting all those shape-shifting water-horse creatures under the same name.

Naturally, Christian religion has taken the Kelpie as a satanic creature, and according to them, carrying a Bible or using a cross to tame the Kelpie works, as well as shooting it with a silver bullet. (strange how the Christian ways to get rid of ‘demons’ is always the same :P )

b. Boggarts: be good or the bogeyman will get you!

In the Harry Potter series, Boggarts first appear in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Professor Lupin introduces them in the first decent Defence Against the Dark Arts lesson Harry and his classmates have had in the two years they’ve been at Hogwarts. Lupin has stored a Boggart in the staffroom wardrobe and intends the students to practice on it to get the grip of the Boggart-Banishing-Spell Riddikulus.

If the spell is Riddikulus, which is a mere spelling twist on the English ridiculous, then it might mean ridicule has something to do with banishing a Boggart. Sure enough, the only way to get rid of a Boggart is making it turn into something so ludicrous you’ll laugh your head off and it’ll blast off. You could ask why you need to do such a thing, though. Well, the answer is easy: the Boggart is a shape-shifting non being that will turn into whatever frightens people the most when they face them. Of course, that means nobody but one that wouldn’t fear anything would know what a Boggart looks like when they hide in dark corners and other confined spaces. Naturally, the more people are tackling the Boggart at the same time, the easier it is to finish it off. If two or more people are in front of it, the Boggart will get confused because it won’t know what to turn into. Lupin says, in Prisoner of Azkaban, that he ‘once saw a Boggart make that very mistake - tried to frighten two people at once and turned himself into half a slug. Not remotely frightening.’ (Chapter Seven)

According to Rowling in her writings for Pottermore, Boggarts’ presence can be felt by Muggles, yet they wouldn’t dare believe that there’s actually something there, and would merely believe it’s their imagination playing a trick on them.

Boggarts are non beings, like Poltergeists or Dementors. Not truly alive, yet not dead. They seem, like Dementors, to feed on human emotions. We don’t know how they breed, but apparently the fuel they use is fear (while remember, Dementors feed not only on fear, but also despair, sadness and all ‘negative’ emotions).

The particularity of Boggarts among shape-shifting creatures is that what they are going to turn into is unknown until it does so, and the variety of shapes it can assume is as wide as the pictures of fear in humankind.

I don’t think I’ve come across anything like a Harry-Potter-style-Boggart in any culture I’ve been reading about. However, since that could be the case, if you know anything of the sort, please comment below the article or on our fb page! I’d love to know more! Here’s what I found, though. Some traits are similar to Rowling’s boggarts, but not many.

Apparently, in Muggle Scotland, a Boggart is a male fairy who will create havoc in your house with great pleasure. Sounds like Peeves to me, but Peeves is a Poltergeist. It also loves frightening travellers (that’s one of the closest trait to a HP-Boggart). Across the British Isles, the Boggart goes by many names: Padfoot or Hobgoblin in Northern England (Hobgoblin is also a nice ale :P ), or even Boogey Man, and all the nicknames such a name can induce people to think of, naturally.

There are two kinds of boggarts, the household ones, and the outdoors ones, the latter living on bogs and marshes. While the household boggarts are more like Peeves, causing mischief and not living you in peace, the outdoor ones are accused of crimes of a more serious nature, like abducting children.

About household boggarts, if they are anyway like Peeves, I can very well imagine that people would want to get rid of them as soon as possible. However, that proves tricky, as this story shows: A man and his family were living in a house where a boggart had decided to establish his residence. It caused so much havoc that at some point the family decided to pack their things and move out. At the gate, the neighbour coming towards the family asked if they were leaving. From the suitcase came that happy cry: ‘Yes, we are!’. The man and his family turned back and went home. There’s no escaping a household boggart.

There are no specific kind of habitat for Boggarts. Of course bogs and marshes, but those are wetlands in general, that, since they are treacherous to wander on, are believed to be home to treacherous and maligne creatures. There are also reports of them living on dangerous slopes over roads, which could suggest that these are made up locations by muggles, because it’s just avoiding to say nature has her own ways and sometimes the stones and trees move on slopes and come down, causing accidents. Caves are also among the favourites, apparently, and that is closer to what Rowling says about Boggarts living in closed dark spaces. There’s a cave in Yorkshire, near Giggleswick, called Cave Ha, that is said to be haunted by a Boggart. Cave Ha, with its unusual name, is a huge shelter cave, and there has been human and animal bones found there, buried, but some also smashed to remove the marrow apparently, which might link the site to a ritual sacrificial place. There’s evidence of Cave Ha being used since the Neolithic period. The local legends around Giggleswick say that around that particular shelter cries and weird noises are often heard, and that a bogard roams around it.

The pictures of boggarts we can find in literature or on the internet often resemble a sort of oldish dwarfish creature with crooked nose and fingers, not unlike the Goblins in the HP-films (see pic above; source:

https://lancashirefolk.com/2017/04/19/a-boggart-did-it-proved-in-court/ )

It looks like in folklore, Boggarts aren’t shape-shifters. The closest to shape-shifting I found is the fact that benevolent household creatures like brownies can turn into boggarts if ill-treated or offended. HA! No way. In Harland and Wilkinson, 1867, there’s a few paragraphs about Boggarts in Lancashire, which, as everyone knows, is a land of witchcraft. Here’s a summary of what they say:

Boggart is a name that might mean two things: bar-gheist, which is literally gate-ghost (bar means gate in the North, and ghast is Anglo-Saxon for spirit, anima), or buhr-gast, wich means town-sprite (buhr being the Anglo-Saxon for town, and gast for ghost). The spirits standing on gates or walls were known to frighten people - that’s consistent with the general fear-thing associated with boggarts. They also say that those boggarts can TAKE VARIOUS FORMS, or, as they put it, strange appearances. So those particular boggarts would be shape-shifters. There’s even a list of creatures the boggart could turn into: ‘a rabbit, dog, bear, or still more fearful form’. Those were recorded east of Manchester. Of course, those boggarts were cleaned off by churchmen at first, and industrialisation next, and in the end, rationality took over and people said that ‘fact'ry folk havin' summat else t'mind nur wanderin' ghosts un' rollickin' sperrits’ and ‘There's no Boggarts neaw, un' iv ther' were, folk han grown so wacken, they'd soon catch 'em.’ That last bit of course makes me think that rationality hadn’t completely won over old ideas, and so much the better, in my opinion. Rationalism alone is not the solution :P

The more I read the book, the more similarities I find with Rowling’s Boggarts. So as seen just before, some boggarts can change shape. It is also widely believed that some enjoy frightening people. However, it was never mentioned to what extent they did that. Rowling of course makes her Boggarts impersonate the worst fear of the person who encounters the Boggart. Tradition makes it a tad different, as Harland and Wilkinson tell (this quote is straight from their book):

‘Having fallen into conversation with a working man on our road to Holme Chapel, we asked him if people in those parts were now ever annoyed by beings of another world. Affecting the esprit fort, he boldly answered, "Noa! the country's too full o' folk;" while his whole manner, and especially his countenance, as plainly said "Yes!" A boy who stood near was more honest. "O, yes!" he exclaimed, turning pale; "the Boggart has driven William Clarke out of his house; he flitted last Friday." "Why," I asked; "what did the Boggart do?" "O, he wouldn't let 'em sleep; he stripp'd off the clothes." "Was that all?" "I canna' say," answered the lad, in a tone which showed he was afraid to repeat all he had heard; "but they're gone, and the house is empty. You can go and see for yoursel', if you loike. Will's a plasterer, and the house is in Burnley Wood, on Brown Hills."’

However, even if there are some tales about shape-shifting boggarts and boggarts that would frighten people so much they’d leave the premises, the usual accounts are those of pesky pests, mostly household creatures who’d play pranks on the inhabitants. Sometimes being helpful, mostly being just nasty things.

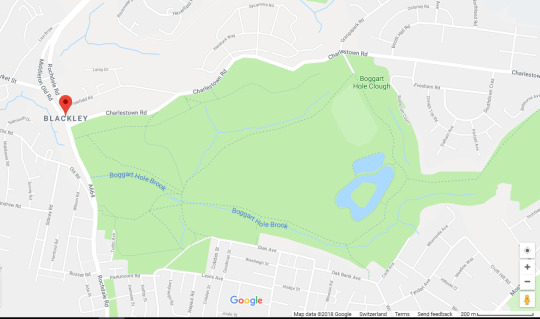

Still, whatever the role of industrialisation and almighty priests in getting rid of boggarts, there are places that retain the history of their being in the names they bear. Those I found were mostly in Lancashire and Yorkshire, UK. For instance, Harland and Wilkinson mention a place north of Manchester, called Blackley, where there is a clough in which boggarts are said to live. Today it’s a park complete with stadium and pond, but records of people disappearing have given credit to the existence of a mean spirit in there, and for centuries the bottom of the clough has been called Boggarts Hole… so…

And just to end up on a funny note: I just read a paper while foraging for pictures and found this. In 1869 a boggart was accused by law of breaking windows in a building. The man who was the first suspect claimed his innocence and gave proof of it, ending his tirade with ‘it must have been a boggart’. The court, then had not choice but to convict the boggart and release the man.

c. Veela

Veela appear for the first time in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, during the Quidditch World Cup, as the mascots of the Bulgarian Team. The description in the book when we first encounter those beings is as follows: ‘Veela were women… the most beautiful women Harry had ever seen … except that they weren’t - they couldn’t be - human. [...] he tried to guess what exactly they could be; what could make their skin shine moon-bright like that, or their white-gold hair fan out behind them without wind… [...] The Veela started to dance, and Harry’s mind had gone completely blissful and blank. All that mattered in the world was that he kept watching the Veela, because if they stopped dancing, terrible things would happen…

As the Veela danced faster and faster, wild, half-formed thoughts started chasing through Harry’s dazed mind. He wanted to do something very impressive, right now. Jumping from the box into the stadium seemed a good idea … but would it be good enough?’ (Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Chapter Eight).

Harry is of course not the only one to be bewitched by Veela, and Ron is even more sensitive to their presence than Harry. He is so sensitive that he, like some other fellow Hogwartsians, is completely besotted when Fleur Delacour arrives for the Triwizard, and she’s only part-Veela, actually only 25%, since it’s from her grandma’s genes.

Veela in Harry Potter can change shape when infuriated, as they did at the Quidditch World Cup after the Irish Leprechauns had been rude to them: ‘They launched themselves across the pitch, and began throwing what seemed to be handfuls of fire at the leprechauns. Watching through his Omnioculars, Harry saw that they didn’t look remotely beautiful now. On the contrary, their faces were elongating into sharp, cruel-beaked bird heads, and long scaly wings were bursting from their shoulders.’ (Chapter Eight)

Veela hair is also considered to have magic enough to be used in wandlore. However, Ollivander wouldn’t use it, sticking to his three favourite, dragon heartstring, phoenix feather and unicorn tail hair. He thinks Veela hair makes temperamental wands (Chapter Eighteen), and honestly who would contradict him, given what happened at the World Cup :P

Only female Veela are mentioned in the Harry Potter books. Apparently they also can breed with ordinary humans, since Fleur’s grandma was a Veela. There’s not much information in the HP books about details, nor is there any writing by Rowling about them. One thing can be said, though, and it’s the strange fact that Veela would submit to serve ordinary humans, in quality of pom pom girls. Honestly, after reading about them, I can’t imagine them doing that at all.

All right. I must admit I thought Veela were a creation of Rowling’s. Well, they aren’t. I always check my books and google everything just in case, and here I was surprised, and not for the worst. The only consequence is that if you’ve been reading that far you’ll be reading another couple of pages :p

Vila (or Wiła) are, according to what I read, the most important creatures of Slavic folklore and are present from the Baltic States to the Balkans as well as in Russia. Online there’s quite a lot about Serbian folklore, but not much else. That actually has an explanation, and thank you Kikimora for providing it :)

There's an important difference between the three groups of Slavic folklore, namely Balcanic on one side, Czech, Polish and Slovak on another, and Russian.

Balcanic Folklore

The Balcanic folklore was directly influenced by Ancient Greek traditions, and they base their documentation on Vila on a book by the famous Greek historian Procopius, who lived in the 6th century AD (I confess I didn’t read the book, so I trust the bloke who wrote the article).

In Serbian, the etymology of the world ‘vila’ would come from the word vel, which means ‘perish’. If you read what Vilas are, it’s a bit strange that the roots of the name would link the creature to death, while they actually are creatures that have the possibility of deciding the time of their own death and rebirth, and aren’t usually death omens. Rather the contrary. Maybe their fierce warrior reputation? However, it seems that many Slavic peoples have similar spirits of the death, or of unbaptized girls (that of course would be after Christianity had overtaken the world and decided that being unbaptized is some sort of death…) or girls condemned to float between life and death because of living a frivolous life or having been cursed by God because of their bad life (always the girls, right….).

According to Serbian folklore, Vila have been thought to be linked to storms and bad weather at first, and only later got linked with forest, water and mountain habitats. They are the equivalent of the Ancient Greek nymphs, can live in various environments and are shape-shifters, yet their usual form is that of a beautiful maiden. Those women can be either naked or dressed in white, but usually have long silvery hair. While unprovoked, Vila are benevolent and helpful, but turn into murderous creatures if molested or offended. It is also said that if seen bathing, or dancing, Vila would hunt the offending men down and shoot them with bow and arrow, sometimes to death, sometimes not. When not, the offender would lose a limb, for instance. That reminds me a bit of other parts of Greek mythology where offenders lost their sight for watching a goddess bathing. However, unlike Athena, Vila would sometimes lure men into dancing or watching them. That could turn into something good or bad for the men. This bit is sort of consistent with the bewitching power of Rowling’s Veela. Vila get their power from their hair, like many other heroes, and from another thing I can’t write the name of (only heard it and don’t want to misspell it), but it’s an element of dressing going down the back from the hair to the wings (when they have wings). If a man stole that bit of clothing while a Vila was bathing, he stole her powers and thus became her master. In other tales this happens if the man plucks a feather of the Vila’s wings. If a Vila’s hair was plucked, though, the Vila would die. So I must imagine that the hair from Fleur’s grandma, that ended up in Fleur’s wand, was collected on a brush or comb :P

Vilas are mostly female. Some claim there’s no male Vila, some that there’s a few, who became such because they came into contact with Vilas. In Serbian folklore, they would be called Vilenyak. Vila could also ‘adopt’ children and it is said a child breast-fed by a Vila would gain unusual strength from it. That happened for instance to the Serbian folklore hero Prince Marko.

Vila have a big responsibility in communities: formerly they would teach people how to sew, plough, irrigate their fields all kind of skills. Vilas are also believed to be learnt in healing with plants and divination or rather prophetisation, and are often mentioned as healers of the hero’s wounds in folk tales. In some tales, Vila go as far as to marry mortal men, putting the usual set of conditions (like not mentioning their decent) lest they would disappear forever. Apparently Fleur’s grandma didn’t come to that extremity with her husband.

North-Eastern European Wiłas

(spelling adopted here: Polish, because I discussed the subject with Polish friends. The spelling differs a bit from one language to the next, but not the names).

We know much less of Vilas in the northern part of Eastern Europe. That's due to many things, amongst which the non-writing of legends is one part, and the fact that most of European Slavic peoples' history has been written by others than the actual peoples. Usually dominating countries or foreign explorers. Archaeologists and anthropology field scientists agree that they can't be sure about anything when it comes to Slavic traditions before Christianisation, and what happened after is of course strongly tainted by ideology.

Slavic peoples from the North-East part of Europe think of Vilas not as nymphs, but more as demons. The word Vila, Wiła in Polish, is not that much used in northern countries, apparently, where those beings are also called Rusałki.

In North-Eastern folklore, it is said that wiłas can shape-shift, namely turn into animals and winds. They are also fierce warriors, like their southern cousins, having that bare and raw natural force (we Finns would call it sisu I'd say) that can help you fulfil your dreams and carry on whatever the circumstances but that can turn against you should you be careless. As Kikimora puts it, it's something along the lines of 'watch out what you wish for, respect what you don't understand, you can't rule everywhere' (Kikimora, pers. comm.).

Unlike the southern folklore, northern Slavic tradition doesn't have male rusałki or wiła. In Slavic folklore, there are some traits or strengths (and weaknesses) that are more male or more female; Wiła and rusałki are female. The male counterpart to rusałki would be wodniki.

Like their southern counterparts, Wiła were demonised (in the clerical sense) once their countries were taken over by Christians, in whose beliefs anything female is dangerous and satanic and bad (remember Satan is a bloke - tries to find coherence - there's none). Before that, there were male and female demons, ghosts, energies... and there was a sort of balance.

So even if we consider both sides of Slavic folklore, we can see similarities between the traditional Vilas and Rusálki/Wiła. There's that shape-shifting, the luring people (both men and women, even if the latter very rarely, according to the internet), the demonish side, and the being careful with what you wish. Remember the things the boys at Hogwarts or at the World Cup did to try and get the Veela's attention...

Arts

Vila have been used by composers in operas, like Hungarian Ferenc Lehár in his Lustige Witwe (1905) and Antonin Dvořák in his Rusálka (1901), and Westerners as well, notably by poet Heinrich Heine and composers Giaccomo Puccini in Le Villi (1884) and Adolphe Adam (Ballet Giselle orLes Wilis, 1841).

4. Summary Comparison

Time to draw a small comparison. Rowling’s shape-shifting creatures are all loosely based on folklore. Whether she knew it or not, nobody can tell but her. However, the coincidences are too strong to leave much doubt.

Shape-shifting is a fairly common thing in the wizarding world, as in folklore.

Kelpies are designed straight from the Scottish folklore version, no doubt about that, even if Scamander doesn’t develop the subject much in his works. They aren’t mentioned often in the Harry Potter books either.

Boggarts are loosely based on Lancashire and Yorkshire versions of the creatures, retaining only the fact that they like frightening people and can shape-shift for that purpose. Rowling takes that further, though, making the creatures Dark and rather close to Dementors in the way they use fear. However, as Boggarts in folklore play tricks on humans, humans in Harry Potter play tricks on Boggarts to get rid of them. The way Mrs Weasley sees the Boggart at 12 Grimmauld Place turn into many different dead people in turn is rather exceptional. I didn’t find anything similar in literature, but again, I didn’t read everything available, I suppose.

To write about Veela Rowling must have known about the Serbian Vila. There are too many similarities (the luring, the dancing, the beauty, the magical hair, the turning into harpie-like creatures) to leave much doubt, but there’s a lot of discrepancies as well, and since there’s no writing by Rowling about Veela anywhere, it’s hard to know to which extent she wanted her Veela to resemble Vila. It’s sure she knew they were from Slavic folklore though, since she attributed them to the Bulgarian Quidditch team as mascots. Now I don’t think Vila would have agreed to be used that way, particularly given the fact they punish people for watching them dance.

Fleur’s grandmother was one of the Veela who married a mortal man, but we know nothing more about that. One thing we can infer from the fact that one of her hair is used as a wand core, is that the magical power of the hair was known by Rowling, and that unless Veela gather their fallen hair it must be horribly difficult for wandmakers to come across that particular core.

Now you could ask me why I don’t mention Obscuri here. As you know, they are creatures generated by a form of transfiguration that is intrinsic to a wizard whose magic has been hindered through his own will or others’. The people who create Obscuri are usually children (they hardly ever live over the age of ten, and in 1926 there was no documented fact that any had lived over that age), according to Newt Scamander in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, the screenplay. In the film, Credence Barebone is an Obscurial, whose magical energy has been repressed for over twenty years and who unleashes a devastating monster when his emotions are triggered. It looks, in the film, that he has gained some mastery over the phenomenon over time, but there’s not much documentation about that. I didn’t include Obscurials in this paper because as far as I know, there’s no counterpart in the Muggle world and I like comparisons.

Next bit: Animagi :) Thank you for reading and commenting if you do!

Sources

Rowling, Joanne K., Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Bloomsbury, London, 1998

Rowling, Joanne K., Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Bloomsbury, London, 1999

Rowling, Joanne K., Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Bloomsbury, London, 2000

Rowling, Joanne K., The Tales of Beedle the Bard, Bloomsbury, London, 2007

Rowling, Joanne K., Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them - The Original Screenplay. Bloomsbury, London, 2016.

Scamander Newt, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, Obscurus Books, Diagon Alley, London, 2001

Wisp, Kennilworthy. Quidditch Through the Ages, Bloomsbury, London, and WhizzHard Books, Diagon Alley, London. 2001.

Kelpies

Kelpies: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kelpie

Necks (water-spirits): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neck_(water_spirit)

Boggarts

http://caveburial.ubss.org.uk/northyorks/caveha.htm

http://oldfieldslimestone.blogspot.ch/2013/03/prehistoric-three-peaks-part-two-cave.html

http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/87393/7/bcra_cks124042.pdf (scientific paper about how the caves formed and what is left now)

http://www.haunted-yorkshire.co.uk/giggleswicksightings.htm (pretty bs paper, most of the text not written by one person and mostly copy-pasted from wikipedia, but has some local stories)

https://www.pottermore.com/writing-by-jk-rowling/boggart

http://manchesterhistory.net/manchester/squares/boggart.html

https://lancashirefolk.com/2017/04/19/a-boggart-did-it-proved-in-court/

Vila and Wiła

Serbian video about Vila in Slavic culture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3qrtiiOH4yc

http://folklorethursday.com/regional-folklore/serbian-folklore-his-majesty-the-zmaj-and-her-majesty-the-vila/#sthash.kgkk4MzK.dpbs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supernatural_beings_in_Slavic_religion#Vila

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Villi (opera by Puccini)

Knowledge base called Kikimora.

General Literature

Johnson, Paul. The Little People of The British Isles, Wooden Books, Glastonbury, 2008. 58 pp.

Kingshill, Sophia; Westwood, Jennifer. The Fabled Coast - Legends and Traditions from around the shores of Britain and Ireland. Arrow Books, 2014. 510 pp.

Kronzek, Allan Zola and Elizabeth, The Sorcerer’s Companion - A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter, Broadway Books, New York, 2001, 286 pp.

Harland, John., Wilkinson, Thomas T., Lancashire Folklore, Frederick Warne & Co., London, 1867 pp 50-62: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/41148/41148-h/41148-h.htm (this book is a real treasure).

#J.K.Rowling#Creatures#British Isles Folklore#Slavic Follklore#Kelpie#Veela#Boggart#Vila#Wiła#Rusalka#Scamander#Harry Potter Series#Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them#Water Horse#Louhi

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I absolutely love your blog, and every October/November I get super excited because my dash is just filled with glorious murder-horses. I was just wondering what you thought were the origins for the capail usice? I like to think the Mares of Diomedes somehow found their way from Greece to British Isles/Thisby (maybe in search of cooler water) and stayed there. Then bam, our water loving, man-eating capail usice are born. So what would your take on their origin be?

Ah, thank you friend! October/November is a glorious time for our fandom, isn’t it? :)

Oh, I love your take on the capaill uisce’s origins! I came across this interesting blog post about reading The Scorpio Races through the lens of classical antiquity, which you might find relevant to your interests!

I’m so fascinated by mythology, and there’s such an interesting collision of Celtic and Greco-Roman mythologies. The Romans adopted Epona, the mare goddess, as one of their own. There’s the hippocampus mosaic at Bath, which I’ve had the pleasure of seeing in person. And then there’s the Pictish Beast, though it isn’t clear whether or not it was influenced by the hippocampus or if it predated it. Could the Romans have brought water horses to Britain?

Celtic mythology is filled with water horse mythology too, i.e. the kelpie, the each-uisge, the cabbyl-ushtey, the Ceffyl Dŵr, Morvarc'h, etc., which are probably related to the Scandinavian bäckahäst and the Germanic neck (Thanks, Wikipedia!). In Irish mythology, Manannán mac Lir, the sea god, had a horse named Enbarr, who could travel across both land and sea (incidentally, I like to think that Manannán mac Lir could be the “forgotten ocean god” that Sean describes as being depicted in Malvern’s stables; the capaill uisce could belong to him, and they were either gifted to humans or they were stolen by them).

Anyway, there are water horse mythologies from all over the world, but there definitely seems to be a concentration of them near the British Isles. On Thisby, Sean says, it is “because we love them,” and I think there’s something really beautiful about that. It’s sobering to think that the capaill uisce could have lived all over the world, only to disappear or die out, and that only Thisby loved them enough to give them a home and let them keep it.

#the scorpio races#maggie stiefvater#anonymous#confession#water horses#capaill uisce#kelpie#relevant mythology#the mares of diomedes#the scorpio races fandom#origin story

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scottish Mythology :- Kelpie

The kelpie is a Scottish creature often associated with the realm of faerie. It also falls into the classification of water horse, although this one is decidedly malevolent. It most commonly appears as a beautiful horse near or in running water, and can be identified by the mane that seems to be constantly dripping wet. Females will sometimes appear as a beautiful woman dressed in green, bent on luring lustful men to their watery doom. (Source)

The kelpie may appear as a tame pony beside a river. It is particularly attractive to children – but they should take care, for once on its back, its sticky magical hide will not allow them to dismount! Once trapped in this way, the kelpie will drag the child into the river and then eat him. (Source)

Merely touching these creatures activates one form of its magic, the ability to adhere a human’s flesh to its own. (...)

This is not the only thing a kelpie can do to defend itself from capture or drag an unwary human to his doom. The kelpie has a tail that can be smacked on the water with such force that a clap of thunder is emitted. The resulting flood can drag a human into the water, where the kelpie will drag them to their death. (Source)

A common Scottish folk tale is that of the kelpie and the ten children. Having lured nine children onto its back, it chases after the tenth. The child strokes its nose and his finger becomes stuck fast. He manages to cut off his finger and escapes. The other nine children are dragged into the water, never to be seen again.

There are many similar tales of water horses in mythology. In Orkney there is the nuggle, in Shetland the shoopiltee and in the Isle of Man, the ‘Cabbyl-ushtey’. In Welsh folklore there are tales of the ‘Ceffyl Dŵr’. And in Scotland there is another water horse, the ‘Each-uisge’, which lurks in lochs and is reputed to be even more vicious than the kelpie. (Source)

“…When thowes dissolve the snawy hoord

An’ float the jinglin’ icy boord

Then, water-kelpies haunt the foord

By your direction

And ‘nighted trav’llers are allur’d

To their destruction…” (Source)

Part of the poem “Address to the Devil” By Robert Burns

0 notes

Text

20 of the world’s best waterfalls: readers’ tips | Travel

Winning tip: Cola de Caballo, Pyrenees, Spain

The aptly named Cola de Caballo (horsetail) cascade is the most spectacular of the many along the Arazas River in the Spanish Pyrenean Ordesa national park. Taking the GR11 upstream from the park’s entrance, a three-hour hike takes you past increasingly dramatic falls. Another kilometre beyond the Cola is the beautifully isolated Góriz mountain refuge hut, where you can enjoy some of Europe’s most unpolluted night skies. The backdrop is the brooding grandeur of Monte Perdido (Lost Mountain) looking down from its 3,300-metre peak, and often you can see giant lammergeiers (also called bearded vultures) circling. To the north, across the French border is Gavarnie, another magnificent waterfall.

Alan

Aquafraggia Falls, Lombardy, Italy

Photograph: Francesco Bergamaschi/Getty Images

A couple of weeks ago we went to the Notte delle Cascate festival which sprawls around the foot of the Acquafraggia Falls in the Val Bregaglia near Chiavenna. We sampled local food and wine as we wandered ever closer to the base of the dramatic falls – two tiers and twin streams dropping 130 metres off the valley wall – and found a good viewpoint to spread our blanket on the grass, and wait. There were river pools for kids to play in and lots of pop-up bars for refreshments. All this is the build up to the exciting climax: at 10pm a squad of abseilers, their bodies outlined with lights, slowly descend the falls in the dark. Magical.

Martha

Grawa, Austria

Photograph: Getty Images

The Grawa waterfall is on the Wild Water Trail in the Stubai Valley. We travelled there by bus using the Stubai Super Card. Our walking group were the only ones there on a damp, misty morning. The 85-metre-wide waterfall wasn’t even in full flow but it was an awesome, thundering spectacle. When we revisited the next day, it was transformed: a bright, sunny afternoon had framed the waterfall with blue sky and green trees and brought many people out to enjoy the show from the wooden platform and seating.

Liz Young

Svartifoss, Iceland

Photograph: Getty Images

One of my most amazing experiences ever was to see the mystical Svartifoss waterfall in Iceland, in the south of Vatnajökull national park. Although this is not the biggest of the Icelandic “fosses”, the magic of the place was palpable. Magnificent octagonal basalt columns that surround Svatrifoss add something special. In the dying light of winter sun, the icy glow of falling glacier water was radiating extraordinary power. The hike to Svartifoss from the visitor centre in Skaftafell takes about 45 minutes each way. Every time I think about Svartifoss, my heart is filled with wonder.

Rod L

Every week we ask our readers for recommendations from their travels. A selection of tips will be featured online and may appear in print, and the best entry each week (as chosen by Tom Hall of Lonely Planet) wins a £200 voucher from hotels.com. To enter the latest competition visit the readers’ tips homepage

Søtefossen, Norway

Photograph: Getty Images

If, like me, you’re obsessed with waterfalls, Norway is the promised land. No other country gives more bang for your buck. Unfortunately many of Norway’s cataracts are harnessed for the country’s huge hydroelectric industry. But a hike up the Kinso River bags you four of its finest unharnessed falls culminating in Søtefossen, a giant double leap down the headwall of the Husedalen. You start in Kinsarvik: there’s a bus stop in the village and a car park at the trailhead a few kilometres up the valley. The trail climbs 666 metres, it’s strenuous but the payoff is extraordinary.

Michael

Glen Maye, Isle of Man

Photograph: Mark Wallace/Alamy

A small but powerful force, Glen Maye waterfall in the Isle of Man plungesthrough a dramatic, intensely green gorge sheltered by mature woods and clothed in moss, ferns and trailing plants saturated by the river’s breath. When the river is not in full spate, the pool is an unforgettable place to swim – deep, wild, clear and exhilaratingly cold. A spirit of Manx folklore – the Cabbyl-Ushtey (Water Horse) – is said to dwell here. Glen Maye is a 10-minute drive from the western town of Peel. There’s a car park above the glen, from which you can follow the river down through the trees to the beach for a picnic.

Elizabeth

Cora Linn, South Lanarkshire

Photograph: Peter Devlin/Alamy

The most magical place in Central Scotland is the Cora Linn at the Falls of Clyde after a heavy rainfall. It can be reached by walking from the historic town of New Lanark via a well-maintained woodland pathway alongside the river where badgers and otters make their home. The falls have impressed and inspired poets and writers for centuries, including Wordsworth, Coleridge, and JMW Turner. The feeling of being miles from anywhere while being midway between Scotland’s major cities is sensational. And when you catch your first sight of the falls the feeling is glorious.

Moira

Mill and Whitfield Gill Force, Wensleydale, Yorkshire

Mill Gill Force. Photograph: Mike Kipling Photography/Alamy

Picturesque Askrigg in Wensleydale offers an enchanting five-mile round-trip to two fabulous but unheralded waterfalls, Mill Gill Force and Whitfield Gill Force. Park outside the church (free) and walk through backstreets and then meadows before meeting Mill Gill Beck in its wooded glade. You’ll soon be following the whooshing of the falls, descending to the first in a cavernous gully shrouded by cliffs and trees. Keep going to the even more spectacular Whitfield, before ascending out of the glen and taking a moorland track back to Askrigg, with commanding views over the dale. Refresh at the ancient and atmospheric King’s Arms, with its excellent food, ales, and friendly staff.

Daniel Ashman

Baatara Gorge waterfall, Lebanon

Photograph: Alamy

The Cave of Three Bridges near Tannourine village (a 90-minute drive from Beirut) is a primordial wonder. A vertical shaft of icy melt water drops 250 metres through a limestone cave. Over the centuries the water has carved three limestone arcs across the main chamber at the end of a dizzyingly steep gorge. The curved nature of the erosion and abundance of greenery give the impression of an imagined landscape, a sublime rendering of the natural world. The Baatara Gorge can be accessed by trail from the village of Mgharet al-Ghaouaghir and offers an insight into the incredible geology of this tiny, troubled country.

Gareth Roberts

Gocta Waterfall, Peru

Photograph: Getty Images

It is well worth the trek to get to this astonishing waterfall. In cloud forest at the edge of the Amazon, in the Chachapoyas region, it is the most beautiful waterfall I’ve ever seen. Locals will tell you it’s the third-highest waterfall in the world (at 771 metres) although experts dispute this because it falls in two drops and it’s rated by the World Waterfall Database as 16th-highest in the world. Whatever its standing, it’s worth the 6km trek, which takes about four hours. The route is generally well-signposted, if a little rugged in parts. It’s also free, unless you want to take up the option of hiring a horse and a guide.

Tim Evans

Moconá Falls, Misiones, Argentina

Photograph: Francois-Olivier Dommergues/Alamy

These falls on the Uruguay River dividing Brazil and Argentina are often overlooked by travellers seeking the undoubted majesty of its big brother, Iguazu, 300km away. We visited Moconá Falls when staying at Don Enrique Lodge, about 50km from the falls, after a tip from our hosts. A 4WD taxi down miles of dirt tracks followed by an hour’s rib-boat trip took us to the 3km-long falls. Uniquely, the falls run the length of the river and although only about 20 metres high, they are breathtaking. Moconá translates in the Guarani language as “to swallow everything”, an entirely justified description. Not easy to reach but an unforgettable experience. Also known as the Yucumã Falls, this incredible sight can also be viewed from the Brazilian side.

Paul Hammond

Snoqualmie, Washington State, US

Photograph: Getty Images

This is the 82-metre waterfall (about 30 metres taller than Niagara Falls) made famous internationally in the 1990s TV series Twin Peaks. One of the great things, beyond the sheer force of its visual splendour, is that Snoqualmie is accessible by public bus services from downtown Seattle (30 miles) for a few dollars, so you don’t need a hire car to get there. It’s less than a mile woodland hike to the base of the falls from the top (and there are other hikes there too).

David Chalton

Sunwapta Falls, Jasper national park, Canada

Photograph: laurenepbath/Getty Images

This is a perfect stopover when driving on the Icefields Parkway. The 18-metre Upper Falls are easily accessed from the car park. The cascading water, partly fed by the Athabasca Glacier, is immensely powerful in spring and early summer when meltwater volumes are at peak. Walk to the centre of the high wooden footbridge that spans the gorge to appreciate the picture-perfect sight of the towering mountains in the background, and the picturesque island of trees just before the falls. Rushing water curves dramatically around both sides of the island. Sunwapta means “turbulent river” in the Stoney First Nation people’s language. A mile’s hike leads you through forest to the Lower Falls. Watch out for bears.

Victoria

Kalandula Falls, Angola

Photograph: Alamy

Angola is home to one of Africa’s biggest waterfalls, the Kalendula Falls, boasting an impressive width of 410 metres and a drop of 105 metres. The thundering noise, mist and setting are overwhelming. The best way to experience the falls is by hire car from Luanda, a six-hour drive on fairly rudimentary roads through varied landscapes. Alternatively, travel by train to the regional capital, Malanje, and then drive north for an hour via Lombe and Calandula. Stay at the charming Pousada Calandula (doubles from about £150). The six rooms have incredible views (and the noise) of the waterfall. The falls are best enjoyed from the B&B’s veranda with its bar.

Line Nyhagen

Ngare Ndare, Kenya

Photograph: Martin Mwaura/Alamy

Hidden in the middle of a small, community-managed forest reserve in central Kenya, Ngare Ndare is an impossibly pretty set of waterfalls perfect for swimming in. Four amazingly clear pools stretch a kilometre from a cerulean-blue pool fed by melting ice from the slopes of nearby Mount Kenya, past a couple of smaller, steeper pools with myriad jumping opportunities for adrenalin junkies, ending with the largest fall and best swimming spot. It’s a cool 4km hike through shady forest from the main gate. Take a guide – we came across elephants.

Clare

Tappiya Falls, Philippines

Photograph: Getty Images

In a valley of the Cordillera mountains, the journey to the Tappiyal Falls involves making your way to the small village of Batad, among the Ifuago rice terraces, a Unesco world heritage site (390km north of Manila). Hiring a local guide costs between £8 and £16 to take you on a trek along the luscious green terraces carving along mountains before a 30-minute descent to the falls. Here, the water plummets 30 metres to a huge, refreshing pool to swim in and wash off the sweat from the hike. Tappiya’s beauty isn’t solely in the falls (stunning as they are), but the journey to get there: to the remote village, the phenomenal terraces, and the tricky descent.

Laurence Britton

Nachi, Japan

Photograph: Sean Pavone/Getty Images

The Kumano Kodo pilgrim trail is actually a collection of routes 100km or so south of Osaka. They are among the best and most well-organised of Japanese hikes with wonderful traditional Japanese accommodation and food on route. The gem at the end of the Nakahechi route is the Nachi Falls which, with a drop of 133 metres, is Japan’s most spectacular cascade. Full details from the Kumano Travel Centre.

John Thackray

Khe Kem, Vietnam

Photograph: Son Viet

Take a rented moped (about £7) from Con Cuông in the North Central Coast region on a meandering 20km ride through chiseled mountains, alongside rural villages to access the graceful Khe Kem waterfall. |For a £1 entry fee, visitors get access to paths with bamboo rails that guide through the undergrowth towards the foot of the cascade, where a serene pool is surrounded by natural sun-baked stone loungers. Swim directly under the flowing torrent while having your feet gently nibbled by some of Pu Mat park’s fish population. If you’re lucky, as we were, an invitation to join a picnicking local family and share in food, beers and cheers might cap this magnificent experience.

Belly

Weeping Wall, Hawaii

Waialeale crater with many waterfalls and green cliffs in Kauai, Hawaii, USA. Photograph: Getty Images

If you take one helicopter trip in your lifetime, let it be around Hawaiian island Kauai. Not only will you feel transported to the opening scene of Jurassic Park, but in one sweep you will see some of the most astonishing and remote landscapes on Earth from an unforgettable vantage. The Waimea Canyon, the towering cliffs of the Nā Pali coastline, the horseshoe reef of Tunnels beach, and the Weeping Wall. Scores of rivulets thousands of feet high fall like tears directly from the misty sky. Set against the emerald background of shield volcano Mount Waialeale: a towering physical beauty from an earlier geological age, this is one of the most astounding sights on the planet. Hiking to the falls is only feasible for experienced adventurers.

Sarah croudace

Whangarei Falls, North Island, New Zealand

Photograph: Chandrasekhar Velayudhan/Getty Images

There are bigger, splashier more dramatic Kiwi waterfalls but few are as photogenic as Whangarei Falls. The spectacular 27-metre drop down a basalt cliff is set in a wooded valley. There’s a wonderful loop walk around the falls among the 500-year-old native flora and fauna. The three viewing platforms, picnic spots and well-maintained paths are balanced with the sheer beauty of the place. It’s easily accessible, a 10-minute drive out of Whangarei, with plenty of free parking and toilets. Walks to the falls from the car parks range from 15 minutes to 1.5 hours. Perfect for a picnic and exploring.

Phil Lines

Looking for a holiday with a difference? Browse Guardian Holidays to see a range of fantastic trips

The post 20 of the world’s best waterfalls: readers’ tips | Travel appeared first on Tripstations.

from Tripstations https://ift.tt/2yrvEht

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Mythological Tournament

Round 1 - Group 1

5 notes

·

View notes