#but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed wi

Text

#Lucy Higgs Nichols (April 10#1838 – January 25#1915)#born into slavery in Tennessee#but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed wi#Paul-Belgium#oldschool

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

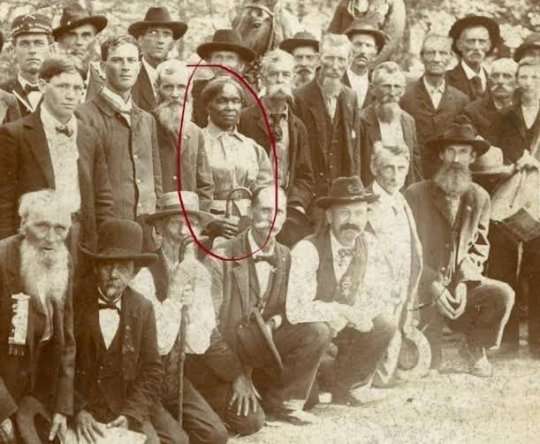

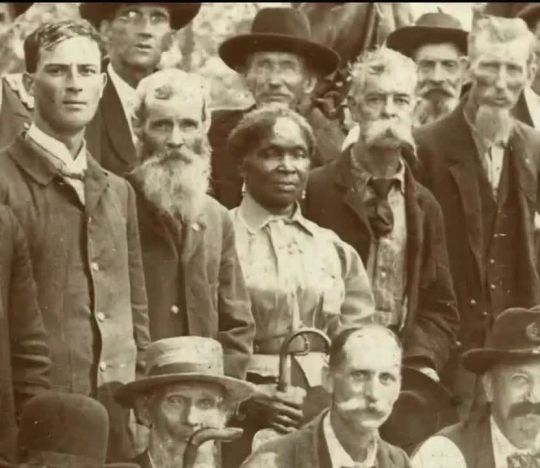

The lady circled in red was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby.

She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war. After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd. She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service.

The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted. The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. She died in 1915 and is buried in a cemetery in New Albany, Indiana.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin#lucy higgs nichols#civil war#tennessee#congress#army nurses#pension act of 1892#indiana#new albany

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

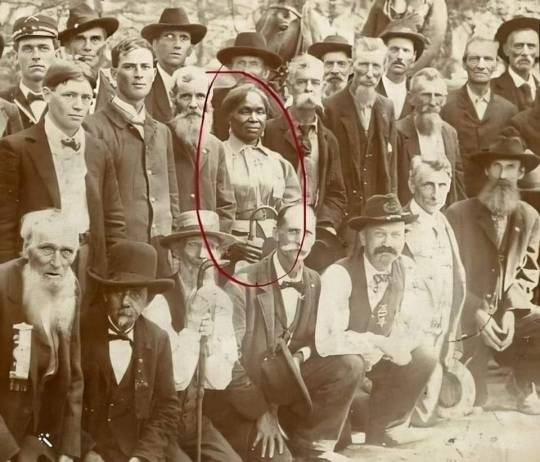

The lady circled in the photo was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby.

She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service.

The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted.

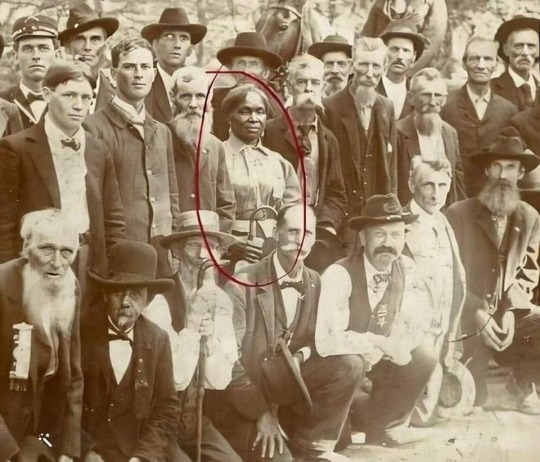

The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. Beloved by the troops who referred to her as “Aunt Lucy,” Nichols was the only woman to receive an honorary induction into the Grand Army of the Republic, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in New Albany with full military honors in 1915.

Source: African Archives Twitter

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

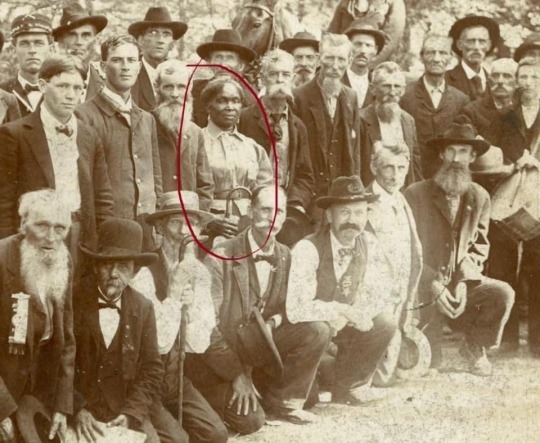

Lucy Higgs Nichols (red circle) was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby.

She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war. After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service. The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted. The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. She died in 1915 and is buried in a cemetery in New Albany, Indiana.

1 note

·

View note

Text

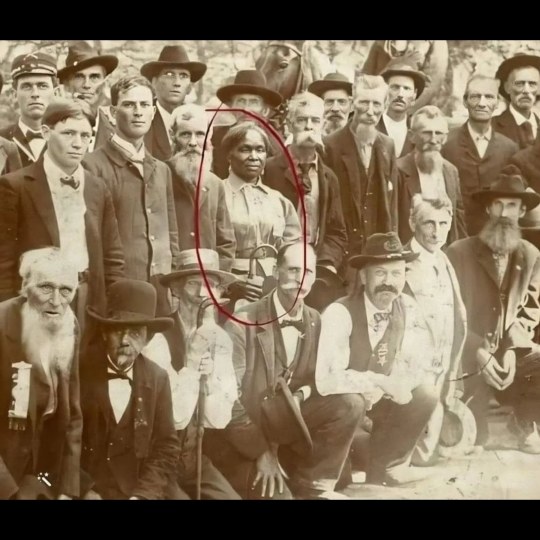

Black History month. Here is your 1st black history heroine.

The lady circled in the photo was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service. The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted.

The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. Beloved by the troops who referred to her as “Aunt Lucy,” Nichols was the only woman to receive an honorary induction into the Grand Army of the Republic, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in New Albany with full military honors in 1915.

#black history month#black history#african american history#african american#civil war#Lucy Higgs Nichols#Civil War nurses#in history#educate yourselves#educational#educate yourself#Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892#black history heroine#black women

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The lady circled in red was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service. The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted.

The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. She died in 1915 and is buried in a cemetery in New Albany, Indiana.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lady circled in the photo was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service. The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted.

The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. Beloved by the troops who referred to her as “Aunt Lucy,” Nichols was the only woman to receive an honorary induction into the Grand Army of the Republic, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in New Albany with full military honors in 1915. 🤎✊🏾

#blackhistorymonth #civilwar

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lady circled in the photo was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service. The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted.

The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. Beloved by the troops who referred to her as “Aunt Lucy,” Nichols was the only woman to receive an honorary induction into the Grand Army of the Republic, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in New Albany with full military honors in 1915.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucy Higgs Nichols: The COuntry Lady

Lucy Higgs Nichols: The COuntry Lady

The lady circled in the photo was Lucy Higgs Nichols.

She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war. After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd. She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service. The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted. The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. Beloved by the troops who referred to her as “Aunt Lucy,” Nichols was the only woman to receive an honorary induction into the Grand Army of the Republic, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in New Albany with full military honors in 1915. #blackhistorymonth is here https://www.instagram.com/p/CZZ6oWNuir_/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

On June 23rd 1314 the Battle of Bannockburn began, the first reported blows in the battle were when Bruce skillfully fought off the English Knight Henry de Bohun, splitting his skull in two with a strike of his axe, although being caught off guard by de Bun, according to legend, Bruce brushed off the encounter by stating his disappointment that he had broken a perfectly good axe.

And so it started the two day battle that was to shape the Scottish psyche for centuries to come, how many of us don't know about Bannockburn?

Anyway I post about the battle every year and decided this year to look at the "Proud Edwards Army"

Edward mustered his great army at Berwick, of between 15,000 and 20,000 men, the largest invasion force Scotland had seen. It wasn't entirely an English army - there were archers from Wales, Irish soldiers, and knights from all over Europe. Some of Robert Bruce's Scottish enemies fought for Edward II too, including the young John Comyn, whose father John the Red Comyn had been stabbed to death by Robert Bruce in 1306. Comyn was killed. It's not clear if the earl of Ulster fought at Bannockburn, but he was with Edward II a month before the battle when Edward was mustering his army. Ulster was in a dificult position, as the father-in-law of Bruce, but also of Edward's nephew the earl of Gloucester.

Only three of Edward's earls fought for him at Bannockburn - his brother-in-law Hereford, who had drawn close to the king since his presence at Piers Gaveston's death, his nephew Gloucester, and his cousin Pembroke. Gloucester was killed, as he forgot to put on the surcoat identifying him as an earl. If the Scottish soldiers had known who he was, they would have captured him for ransom. Robert Bruce treated Gloucester's body with the utmost respect, and personally kept an overnight vigil over it. Although the men had never met (as far as I know), they were second cousins - Bruce's grandmother was a de Clare - and were married to sisters, Elizabeth and Maud de Burgh. Bruce sent Gloucester's body back to England with full honours and without demanding payment, as he had every right to do.

Many English barons fought for Edward II, however: Roger Mortimer, twenty-seven, and his uncle Roger Mortimer of Chirk, in his late fifties and a veteran of Edward I's Welsh wars of the late 1270s and early 1280s. Thomas, Lord Berkeley, who was almost seventy!! Edward's French cousin Henry Beaumont, Hugh Despenser the Elder and Younger, Robert Clifford.

Edward marched into Scotland with a baggage train that stretched back twenty leagues, including jewellery, napery, costly plate, and ecclesiastical vestments for celebrating the victory. He also ordered ships to Edinburgh with more things, and the personal possessions of the earl of Hereford alone required an entire ship. Edward, and others, acted as though all they had to do was turn up and they would win. This, of course, was a horrible mistake. The Lanercost Chronicle says that Edward marched with great pomp and elaborate state, purveying goods from monasteries as he passed, and, oddly, that he "did and said things to the prejudice and injury of the saints."

For all Edward's incompetence as a general, his personal courage in the battle is beyond question, and the chronicler Trokelowe says that he fought like a lion. At one point, his horse was killed beneath him, and Scottish soldiers rushed forward to capture him. Edward’s knights surrounded him, beating them off, and Edward managed to mount another horse, from the many running around the battlefield. Again, Scottish soldiers pressed forward to try to capture him, grabbing hold of his horse’s trappings. Edward "struck out so vigorously behind him with his mace there was none whom he touched that he did not fell to the ground" according to the Scalacronica of Sir Thomas Gray, whose father was captured at the battle.

After some hours, the ground wet with blood, dead bodies of horses and men underfoot, the earl of Pembroke realised the battle was lost. He grabbed Edward's reins and dragged, him, protesting, from the field. 500 knights, including Henry Beaumont and the younger Despenser, surrounded him, their only thought: protect the king. Philip Mowbray, the constable of Stirling Castle (Scottish but on Edward's side) refused to let them enter, sensibly, as Edward would be trapped there, surrounded by the Scottish army. All they could do was gallop the fifty miles to Dunbar, which must have taken many hours. Bruce's friend Sir James Douglas followed them all the way, picking off stragglers, so close that it was said the men had no time even to stop and pass water.

Edward and his men reached Dunbar, where his ally Patrick, earl of Dunbar, opened up the castle drawbridge for them. Edward and his knights jumped off their horses, leaving them outside, and ran inside the castle. Earl Patrick found a fishing boat, and Edward made his way to Bamburgh with a handful of attendants. From there, he made his way to Berwick overland. His remaining knights were forced to ride to Berwick, with James Douglas and his men close behind them, shedding their armour to speed their way. Edward was incredibly lucky to escape capture by Douglas, and in gratitude, founded Oriel College at Oxford some years later, according to Geoffrey le Baker.

And so the king returned to Berwick not at the head of a victorious army, but in flight, forced to travel by fishing boat. His Queen Isabella supported Edward with her usual loyalty, and lent him her seal so that government business could continue, Edward's having been lost on the battlefield (Bruce returned it). She tended to his wounds herself, and even cleaned his armour.

The Vita says this about the defeat of Bannockburn: "O day of vengeance and disaster, day of utter loss and shame, evil and accursed day, not to be reckoned in our calendar; that blemished the reputation of the English."

As utterly humiliating as Edward's flight from the battlefield was, it was infinitely preferable to the two alternatives, his capture or his death. Being captured would have meant a cripplingly huge ransom, and the commentators who castigate him for his lack of military ability and cowardice would instead castigate him for his lack of military ability and his reckless stupidity. In fact, accusations of cowardice are grossly unfair, as even men who had no reason to like Edward admitted his bravery during the battle.

Edward's death in battle would have brought his nineteen-month-old son to the throne, which meant a regency of many years standing. And as events were shortly to prove, the men who replaced Edward in power were not one whit more competent than he was. A regency would have meant struggles for power, jockeying for position, while Bruce took advantage of the chaos.

Still, for the king of England, galloping away in ignominious flight from a battle he fully expected to win, the realisation that he had at least spared his country a crippling ransom or the perils of a long regency was probably no consolation whatsoever.

A wee footnote to about the fate of Edward II, he clung on to power, he survived a civil war in which started in 1321 but by January 1327 was forced to abdicate, his 14 year old son, also called Edward took the throne. The deposed King spent his last days at at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire where it is said that on 21 September 1327 by being held down and having a red-hot poker inserted inside his anus, and his screams could be heard miles away. This torture and death are said to have links to Edwards perceived homosexuality, his body is interred at what is now Gloucester Cathedral, the tomb was opened in 1855 uncovering a wooden coffin, still in good condition, and a sealed lead coffin inside it, I wonder if the murder story is true and if modern forensics could prove it? Another story says he escaped and retired to become a hermit in the Holy Roman Empire. Either way, an inglorious end to the son of Edward I, who became known as "The Hammer of Scots"

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lady circled in the photo was Lucy Higgs Nichols. She was born into slavery in Tennessee, but during the Civil War she managed to escape and found her way to 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment which was encamped nearby. She stayed with the regiment and worked as a nurse throughout the war.

After the war, she moved north with the regiment and settled in Indiana, where she found work with some of the veterans of the 23rd.

She applied for a pension after Congress passed the Army Nurses Pension Act of 1892 which allowed Civil War nurses to draw pensions for their service. The War Department had no record of her, so her pension was denied. Fifty-five surviving veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress for the pension they felt she had rightfully earned, and it was granted.

The photograph shows Nichols and other veterans of the Indiana regiment at a reunion in 1898. Beloved by the troops who referred to her as “Aunt Lucy,” Nichols was the only woman to receive an honorary induction into the Grand Army of the Republic, and she was buried in an unmarked grave in New Albany with full military honors in 1915.

Lucy Higgs Nichols aka Aunt Lucy

190 notes

·

View notes