#arthur edmund carewe

Text

REPO! The Genetic Opera but it’s a silent film from 1928

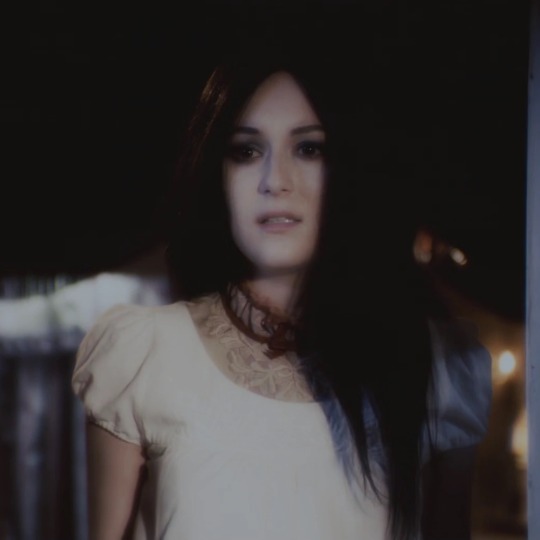

Pavi Largo - Conrad Veidt

Blind Mag - Theda Bara

Graverobber - Arthur Edmund Carewe

Luigi Largo - Lon Chaney

Amber Sweet - Olga Baclanova

Shilo Wallace - Marceline Day

#alternate cast list: connie plays everyone#he could do it#haven’t thought of ppl for nathan or rotti yet#i thought wayyyyy too hard about some of these#theda bara went back n fourth between mag and amber sweet for a while#and then i remembered olga baclanova exists#i thought mary philbin as blind mag would also be a fun idea just bc her and sarah brightman both played christine daae at one point#but she could also be a good shilo#also#none of these were biased idk what you’re talking about#suddenly it is 2020 and REPO! is always on my mind again#conrad veidt#theda bara#olga baclanova#marceline day#lon chaney#arthur edmund carewe#repo! the genetic opera

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

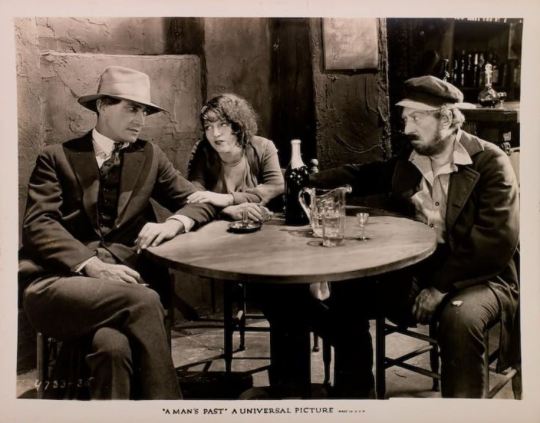

Conrad Veidt, Barbara Bedford, Ian Keith, and Arthur Edmund Carewe in the lost 1927 film A Man's Past (1/2).

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

POTO adaptations analysis — Part 1 — The Phantom of the Opera (1925), by Rupert Julian, starring Lon Chaney and Mary Philbin

I will list the positive and negative points of which midia and give a score at the end (remember this is MY OPINION)

Positive points:

– this movie has a lot of different soundtracks, but my favorite is Gabriel Thibaudeau's. His Don Juan Triumphant piece is simply fantastic

– the casting couldn't be more perfect, even if Raoul and Christine were blonde in the original novel, the actors still give an amazing performance for their characters. Mary Philbin and Lon Chaney as the two main holes are the best thing of this movie

– it's extremely Leroux accurate. Sure, they needed to explain the events as fast as they could because it's a silent movie of less than 2 hours, but it still captures the atmosphere of the novel

– the scenarios are amazing and they were made specifically for this movie (no, they didn't go to the actual Opera Garnier, it was all built!), specially Erik's lair which is amazing

– can we apreciate more the unmasking scene? Aside from the acting and direction that are already great, the scene is both frightening and tragic, it makes you sympathize for both Christine and Erik in that situation

– the figurine of this movie is speechless. Although i miss Christine's black dominó, but it's still accurate to the characters and the 19th century

– aside from horror and romance, this movie also includes the comedy scenes that the original novel had

– the chandelier scene was pretty difficult to simulate back in 1925 yet they still managed to do it realistically 👌🏼

– Erik's hand gestures and expressions 🥹 it's a whole movie by himself

– THE RED DEATH OMG his red cape in a black-and-white scenario is just 👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼

– Erik's make-up is obviously the best thing about this movie. Lon Chaney made it all himself, his work is still the most accurate and realistic deformity

– they included the Grasshopper and Scorpion scene

– Erik's lion alarm is so cute (not sure of how it works but anyway)

– the scene where Erik enters the lake as the Siren is so fucking perfect, really it's weird and cute the same time (and seeing wet Erik honestly makes me wetter than the Count's corpse)

– the scene where Erik leads Christine to his lair for the first time is the sweetest scene ever, he is so sympathetic and trying his best to make her comfortable

– also; the Don Juan was written out of the love he had for Christine. She was his inspiration 🥹 he wrote it for her!!

– DAROGA IS HEREalthogh he is a white man and has no relationship with Erik butAND HIS NAME IS LEDOUX

Negative points:

– instead of the love triangle, Raoul and Christine are just lovers since the beginning of the movie and it obviously makes him more "sympathetic" (even if he's useless and has creepy behaviours such as hiding in her dressing room to spy on her)

– Erik directly and shamelessly threatens to kill Christine in the unmasking scene? No, why??

– Christine has little to no agency here, and the rooftop scene makes her much more unsympathetic, she wasn't so petty in the novel even in the Apollo's Lyre

– the ending. Obvious that nonsense angry mob that discovered Erik's lair out of a miracle was included after the original ending was changed. It's just nonsense and cruel and takes away the redemption that Erik needed, like if the original message didn't even exist

Movie score: 8/10 🌕🌕🌕🌕🌗

#the phantom of the opera#erik#poto#gothic literature#gaston leroux#christine daaé#raoul de chagny#lon chaney#mary philbin#daroga#the persian#norman kerry#silent movies#universal monsters#arthur edmund carewe#my writing#adaptations#the phantom of the opera 1925#poto 1925

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Phantom of the Opera

directed by Rupert Julian, 1925

#The Phantom of the Opera#Rupert Julian#movie mosaics#Lon Chaney#Mary Philbin#Arthur Edmund Carewe#Norman Kerry

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

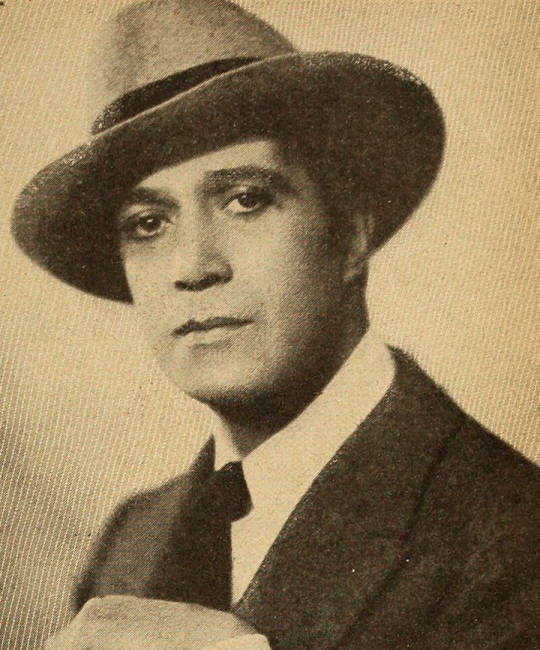

Arthur Edmund Carewe | Doctor X (1932)

#arthur edmund carewe#doctor x#1930s#pre code hollywood#pre code movies#pre code horror#30s movies#1930s hollywood

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movie Odyssey Retrospective

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

By the time French journalist-turned-novelist Gaston Leroux published Le Fantôme de l'Opéra as a serial in 1909, he was best known for his detective fiction, deeply influenced by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allan Poe. The Phantom of the Opera plays out like a Poe work – teeming with the macabre, painted with one character’s fanatic, violent lust. In serial form and, later, as a novel, Leroux’s work won praise across the West. One of the book’s many fans was Universal Pictures president Carl Laemmle who, on a 1922 trip to Paris, met with Leroux. While on the trip, he read Phantom (a copy gifted to him by Leroux) in a single night, and bought the film rights with a certain actor already in mind.

Laemmle’s first and only choice for the role of the Phantom was about to play Quasimodo in Universal’s 1923 adaptation of Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame. That actor, Lon Chaney, had subsisted on bit roles and background parts since entering into a contract with Universal in 1912. Chaney, who was about to sign a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), became an instant sensation the moment The Hunchback of Notre Dame hit theaters. Audiences and critics in the early 1920s were simultaneously horrified at the sight of his Quasimodo yet, crucially, felt a profound empathy towards the character.

In his prior films, as well as Hunchback, Chaney separated himself from his fellow bit actors with a skill that almost no other actor in Hollywood possessed: he was also a makeup artist. At this time, actors applied their own makeup – often simple cosmetics or unconvincing facial hair. None of the major Hollywood studios had makeup departments in the early 1920s, and it would not be until the 1940s that each studio had such a department. Chaney, the son of two deaf and mute adults, was also a master of physical acting, and could expertly use his hands and arms to empower a scene. Though already bound for MGM, Chaney could not possibly pass up the role of Erik, the Phantom. Despite frequent clashes with director Rupert Julian (1923’s Merry-Go-Round and 1930’s The Cat Creeps; despite being Universal’s most acclaimed director at this time, Julian was either sacked or walked away mid-production), Chaney’s performance alone earned him his place in cinematic history and, for this film, an iconic work of horror cinema and silent film.

As the film begins, we find ourselves at the Palais Garnier, home of the Paris Opera. The Opera’s management has resigned, turning over the Palais Garnier to new ownership. As the ink dries on the contract and as the previous owners depart, they warn about a Phantom of the Opera, who likes sitting in one of the box seats. Soon after, prima donna Carlotta (Virginia Pearson) receives a threatening letter from the Phantom. She must step aside and allow a chorus girl, Christine Daaé (Mary Philbin), sing the lead role in Charles Gounod’s Faust. If she refuses to comply, the Phantom promises something horrific. Aware of the letter, Christine the next day confers with her loved one, the Vicomte Raoul de Chagny (Norman Kerry), that she has been receiving musical guidance from a “Spirit of Music”, whom she has heard through the walls of her dressing room. Raoul laughs this off, but a series of murderous incidents at that evening’s production of Faust is no laughing matter. Christine eventually meets the shadowy musical genius of the Phantom, whose name is Erik (Chaney). In his subterranean lair, he professes his love to her – a love that will never die.

Rupert Julian’s The Phantom of the Opera also stars Arthur Edmund Carewe as the Inspector Ledoux (for fans of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical version, this is the Madame Giry character); Gibson Gowland as Simon Buquet; and John St. Polis as Raoul’s brother, the Comte Philippe de Chagny.

Before extoling this film, one has to single out Mary Philbin and Norman Kerry as the glaring underperformers in this adaptation. Philbin would become a much better actress than she displays here, if The Man Who Laughs (1928) is any indication. Yet, Philbin’s Christine is a blank slate, devoid of much personality and interest. It also does not help that Norman Kerry plays Raoul in a similar fashion. Raoul, in any adaptation of Phantom, tends to be a boring role. But goodness me, for a B-actor who was acclaimed for his tall, dark, and handsome looks and screen persona, he is a charisma vacuum here. During Kerry’s more intimate scenes with Philbin, you may notice that Kerry has a case of “roving hands” when he gets close with Philbin. Philbin, who could not visibly react to these moments on-camera, surreptitiously took Kerry’s hands and held them there to stop the touching.

Philbin is much better when sharing the screen opposite Chaney. Chaney and Philbin both could not stand director Rupert Julian – whom both actors, as well almost all of the crew, regarded as an imposing fraud who knew little about making art and more about how to cut costs (Laemmle appointed Julian for this film in part due to Julian’s reputation for delivering work under budget). There are unconfirmed accounts that after Julian’s departure or removal from Phantom, Chaney himself directed the remainder of the shoot aside from the final climactic chase scene (which was the uncredited Edward Sedgwick’s responsibility). In any case, Philbin’s terror when around Chaney was real. The sets of the Phantom’s lair reportedly spooked her – the subterranean waterways, his inner sanctum. Philbin also received no preparation before the filming of what is now one of the signature moments of the silent film era and all of horror cinema. Her reaction to Lon Chaney’s self-applied makeup – meant to appear half-skin, half-skeletal – was the first time that she saw Chaney’s Phantom in all his gruesomeness. Philbin, freed of the innocent, pedestrian dialogue of the film’s opening act, gifts to the camera one hell of a reaction, fully fitting within the bounds of silent film horror.

There are conflicting records on how Chaney achieved the Phantom’s final appearance. The descriptions forthcoming are the elements that freely-available scholarship generally accepts as true. It appears that Chaney utilized a skull cap to raise his forehead’s height, as well as marking deep pencil lines onto that cap to accentuate wrinkles and his brow. He also raised his cheekbones by stuffing cotton into his cheeks, as well as placing a set of stylized, decaying dentures. Inner-nasal wiring altered the angle of his nose, and white highlights across his face contributed to his skeletal look for the cameras. Cinematographer Charles Van Enger (1920's The Last of the Mohicans, uncredited on 1925's The Big Parade) – who, other than Chaney, was one of the most familiar onset with Chaney’s makeup – claimed that the nasal wiring sometimes led to significant bleeding. Taking inspiration from Chaney’s approach to keeping the makeup artistry hidden from Philbin and others, Universal kept the Phantom’s true appearance a secret from the public and press. The studio advised movie theaters to keep smelling salts ready, in case of audience members fainting during the unmasking scene. According to popular reporting at the time, audience members did scream and faint upon the reveal; a nine-year-old Gregory Peck’s first movie memory was being so terrified of Lon Chaney’s Phantom, that he asked to sleep with his grandmother that evening after he came home.

youtube

Lon Chaney’s tremendous performance allows The Phantom of the Opera to soar. Arguably, it is his career pinnacle. Masked or unmasked, Chaney’s Phantom dominates the frame at any moment he is onscreen aside from the film’s final chase sequence. Whether glowering over Christine, majestically gesturing in silhouette, strutting down the Opera House steps during the Bal Masqué, or tucked into the corner of the frame, Chaney’s physical presence draws the audience’s eyes to whatever he is doing. The differences in posture from before and after the unmasking scene are striking – from an elegant specter to a broken, hunched figure (appearing to draw some inspiration from his experience playing Quasimodo two years earlier) seething with pent-up carnality, rage, and sorrow. Chaney’s Phantom garners the audience’s sympathy when he gives Christine the grand tour of his chambers. Look at his posture and hands when he mentions, “That is where I sleep,” and, “If I am the Phantom, it is because man’s hatred has made me so.” That Chaney can ease through these transitions and transformations – as well as a third transformation, as the Red Death during the Bal Masqué – so naturally, without a misstep, is a testament to his acting ability.

Underneath the tortured and twisted visage of a man who has committed horrific acts is a vulnerable and misguided human being. His dreams, dashed and discarded by all others, have turned to despicable means. The role of the Phantom plays brilliantly to Chaney’s genius: to have audiences sympathize with even the most despicable or despondent characters he played. Chaney accomplishes this despite this film characterizing the Phantom with less sympathy than Leroux’s original novel and the popular Andrew Lloyd Webber musical.

This is already on top of Charles Van Enger’s camerawork; the sharp editing from a team including Edward Curtiss (1932’s Scarface) Maurice Pivar (1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame), Gilmore Walker (1927’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin), and Lois Weber.

Weber, who in 1916 was Universal’s highest-paid director, underwent numerous financial difficulties over that decade. One of Hollywood’s first true auteurs and largely ignored in the history of film until recently, Weber formed her own production company with Universal’s assistance in 1917, off the success of Shoes (1916). Through World War I, Weber’s movies were popular until around the turn of the decade, when her “didactic” filmmaking (a result of her devout Christian upbringing) went out of style. Most visibly among Weber’s financial failures of the early 1920s, The Blot (1921) – a movie that scholars and Weber himself considered her best – flopped in theaters. After two hiatuses from filmmaking in the early 1920s, Weber was brought in to conduct the final bits of editing on The Phantom of the Opera before returning to directing under Universal.

Though none of the film’s production designers were yet to hit their peak, The Phantom of the Opera benefitted from having a soon-to-be all-star art department including James Basevi (1944’s The Song of Bernadette), Cedric Gibbons (almost any and all MGM movies from 1925 onward), and Robert Florey (1932’s Murders in the Rue Morgue). Inspired by designs sketched by French art director Ben Carré, the production design trio spared no expense to bring Carré’s illustrations to life and used the entirety of Universal’s Soundstage 28 to construct all necessary interior sets. The set’s five tiers of seating and vast foyer needed to support several hundred extras. So unlike the customary wooden supports commonplace during the silent era for gargantuan sets, The Phantom of the Opera’s set for the Palais Garnier became the first film set ever to use steel supports planted into concrete. Basevi, Gibbons, and Florey’s work is glorious, with no special effects to supplement the visuals. The seventeen-minute Bal Masqué scene – which was shot in gorgeous two-strip Technicolor (the earliest form of Technicolor, which emphasized greens and reds) – is the most striking of all, unfurling its gaudy magnificence to heights rarely seen in cinema.

Universal’s Soundstage 28 was an integral part of the VIP tour at Universal Studios Hollywood for decades. Though the orchestra seats and the stage of the film’s Palais Garnier had long gone, the backside box seats of the auditorium remained. Stage 28 featured in numerous films after The Phantom of the Opera, including Dracula (1931), the Lon Chaney biopic Man of a Thousand Faces (1957), Psycho (1960), Charade (1963), Jurassic Park (1993), How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000), and The Muppets (2011). The soundstage was also supposedly haunted, with individuals claiming to see a caped figure (Lon Chaney as the Phantom?) running around the catwalks, lights flickering on and off, and doors opening and closing on their own. In 2014, after standing for almost ninety years, Universal decided to demolish Stage 28 so as to expand its theme park. However, the historic set escaped the wrecking ball, as Universal decided to disassemble the set, place it into storage, and perhaps someday reassemble it. It is a fate far kinder than almost all other production design relics from the silent era.

Unlike what was coming out of Weimar Germany in the 1920s in the form of German Expressionism, American horror films had no template to follow when The Phantom of the Opera arrived in theaters. There would be no codification of American horror cinema’s tropes and sense of timing until the next decade. But without 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera, Universal would never become the house of horror it did in the 1930s through the early ‘50s (including the Dracula, Frankenstein, Mummy, Invisible Man, Wolf Man, and Creature from the Black Lagoon series). So, unbound by any unwritten guidelines, 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera – a horror film, but arguably also a melodrama with elements of horror – consumes the viewer with its chilling atmosphere and, from Lon Chaney, one of the best cinematic performances ever, without any qualification. For silent film novices, this is one of the best films to begin with (outside the comedies of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd). Regardless of one’s familiarity with silent film, The Phantom of the Opera is a cinematic milestone.

My rating: 9.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

This is the twenty-third Movie Odyssey Retrospective. Movie Odyssey Retrospectives are reviews on films I had seen in their entirety before this blog’s creation or films I failed to give a full-length write-up to following the blog’s creation. Previous Retrospectives include Dracula (1931 English-language version), Oliver! (1968), and Peter Pan (1953).

#The Phantom of the Opera#Rupert Julian#Lon Chaney#Mary Philbin#Norman Kerry#Carl Laemmle#Gaston Leroux#Ernst Laemmle#Edward Sedgwick#Arthur Edmund Carewe#Gibson Gowland#Snitz Edwards#Virginia Pearson#Edward Curtiss#Maurice Pivar#Gilmore Walker#Lois Weber#silent film#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keep your hand at the level of your eyes!

The Phantom of the Opera 1925

Arthur Edmund Carewe and Norman Kerry

#the phantom of the opera#1925#vintage#silent film#1920s#norman kerry#arthur edmund carewe#raul de chagny#the persian#daroga#promo shot

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

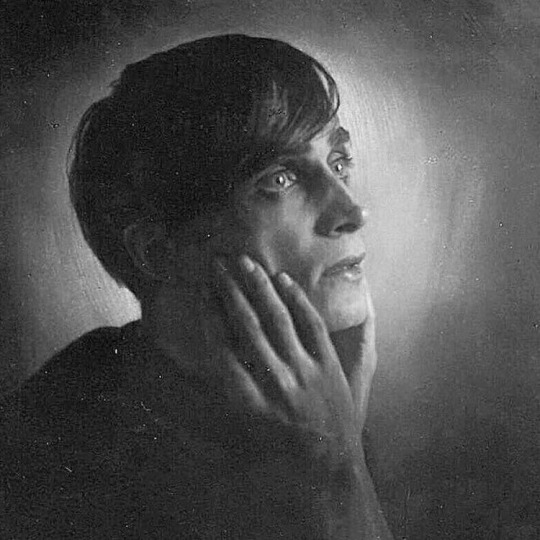

Arthur Edmund Carewe

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1, match 56

Lillian Yarbo vs Arthur Edmund Carewe

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

nothing makes me more upset than discovering an actor from the 1920's I really like and checking their filmography only to see that over half of it is marked as 'Lost Film' 😭😭😭

#yes this is about Arthur Edmund Carewe#28/50 of his works are just... gone#how depressing is that???

1 note

·

View note

Text

Commentary by the author of the drawings (who is not me, but the artist at @vermium!):

The Persian is based on 1925 version, played by Arthur Edmund Carewe. He was the best, even though he wasn’t supposed to be THE Persian, but some other guy. The Persian is fascinating. He is like Theseus who can’t bring himself to slay the Minotaur, the whole purpose of him entering the labyrinth, and the Minotaur has long forgotten about him. His guns in disuse, his sword all clean, the unfortunate Theseus wanders the house of Asterion aimlessly, lonely like the monster, lost in the labyrinth like a man would be. There is a part in the book when the Phantom, the one who wants to be seen, loved, all of that stuff, turns to a man who saved his ass, paying for that with his everything, his homeland, even his name - and casually says: “you didn’t exist, you had ceased to exist”.

The Red Death - the hat is inspired by Cranach, the text comes from Petrarch’s The Secret, and the skeleton illusion is based on pajamas.

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’ve been hating too much today so you know something i LOVE. i LOVE the 1925 phantom of the opera. i LOVEEEE this movie. this was my intro to silent films and i LOVE IT. i LOVE mary philbin. i LOVE lon chaneys makeup skills. i LOVE the technicolor sequence. i LOVE the cool as outfits everyone wears. i LOVE that the daroga is actually in this vers even though they last minute made him fr*nch. i LOVE universal monsters. i LOVE u phantom of the opera 1925 vers.

#the phantom of the opera 1925#hashtag positivity#currently re listening to the audio from the lost sound version#bc while the actual picture is dead all of the audio survives#universal monsters#lon chaney#mary philbin#norman kerry#arthur edmund carewe

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conrad Veidt, Barbara Bedford, Ian Keith, and Arthur Edmund Carewe in the lost 1927 film A Man's Past (2/2).

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fay Wray and Glenda Farrell in Mystery of the Wax Museum (Michael Curtiz, 1933)

Cast: Lionel Atwill, Fay Wray, Glenda Farrell, Frank McHugh, Allen Vincent, Gavin Gordon, Edwin Maxwell, Holmes Herbert, Claude King, Arthur Edmund Carewe, Thomas E. Jackson, DeWitt Jennings, Matthew Betz, Monica Bannister. Screenplay: Don Mullaly, Carl Ericson, Charles Belden. Cinematography: Ray Rennahan. Art direction: Anton Grot. Film editing: George Amy.

The ever-imperiled Fay Wray gets higher billing, but the real star of Mystery of the Wax Museum is Glenda Farrell, playing an intrepid (what else?), tough-talking (ditto) newspaper reporter, Florence Dempsey. Flo's boss, Jim (Frank McHugh), gives her her walking papers, so she sets out to find a sensational story to save her job. She uncovers the sinister plot of Ivan Igor (Lionel Atwill), who is opening a new wax museum in New York. Igor had a similar museum in London, but it was losing money, so his partner in the business, Joe Worth (Edwin Maxwell), burned it down to collect the insurance. Igor was trapped in the conflagration but survived. Handicapped by his wounds, he trains new sculptors to re-create the glories of the old museum. One of the trainees is Ralph Burton (Allen Vincent), whose fiancée, Charlotte Duncan (Wray), turns out to be the spitting image of Igor's most prized sculpture in the old museum, an effigy of Marie Antoinette. Naturally, Igor plans to "sculpt" Charlotte into a new Marie: His method of capturing images is, let's say, not the traditional one. By a bit of breaking and entering, Flo manages to discover the macabre truth behind the wax museum's images. The plot gimmick -- a reporter uncovers a madman's schemes -- is exactly that of Doctor X (1932), Michael Curtiz's other venture into horror movie territory filmed in two-strip Technicolor, which also starred Atwill and Wray. Mystery of the Wax Museum is the better movie, with Farrell giving a better performance as the snoopy reporter than Lee Tracy in the earlier movie. It also has a neater plot, and a real creep factor in the spooky statues -- most of which are actors standing very still. Makeup artists Ray Romero and Perc Westmore and costume designer Orry-Kelly deserve special mention.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Arthur Edmund Carewe | Doctor X (1932)

#arthur edmund carewe#doctor x#1930s#pre code hollywood#pre code film#pre code horror#30s movies#1930s horror#1930s hollywood#lionel atwill#harry beresford#john wray

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes