#arnold schönberg center

Text

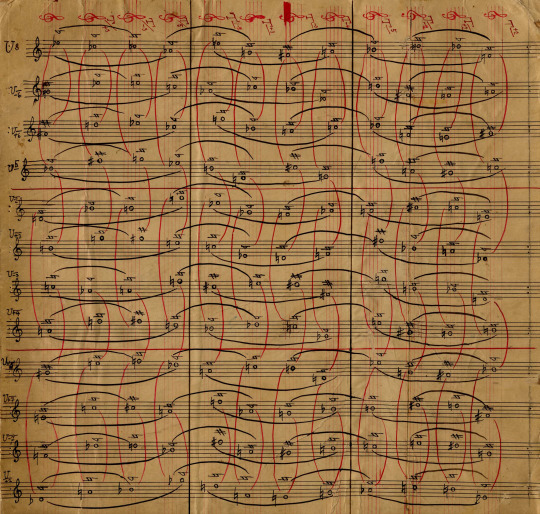

Arnold Schönberg, Suite, op. 29 – Bi-directional twelve-tone row chart, n.d. [1925-1926] [Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz. © Arnold Schönberg Center, Wien. © Arnold Schönberg Estate]

#art#manuscript#music#score#music score#notation#music notation#visual writing#arnold schönberg#arnold schönberg center#no date#1920s

269 notes

·

View notes

Photo

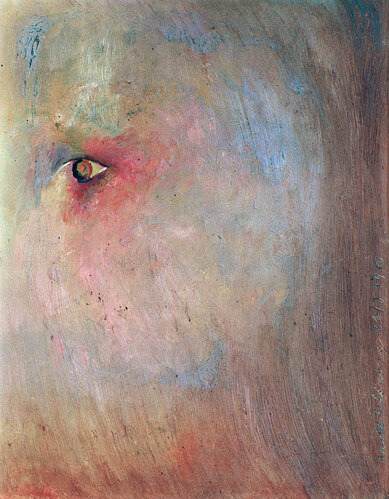

Arnold Schoenberg, Red Gaze, ca. 1910, oil on cardboard, 22 x 28 cm, Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna, Austria.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aesthetic conservatism is inextricably linked with political and social conservatism. By aesthetic conservatism, I basically mean anti-modern art. It’s an aesthetic doctrine. Music should be tonal and melodious, instead of atonal. Paintings and sculptures should be figurative instead of abstact. Storytelling in film and novels should be simple and direct. It upholds the traditional forms of (western) art as superior to modernist ideas. This is not some innocent “aesthetic preference”.

This naturally takes the form of a kind of anti-urbanism, as the industrial city is the site of modernity. And an accompanying romanticization of rural life and farming, agrarianism. It’s also of course anti-intellectual. The anti-modernist art narrative goes that intellectuals and artists in the big city, because of their unnatural technological lifestyle have lost touch with the common people and indeed reality. The common people who do physical labor and work the earth are in touch in that reality.

Of course, the common people in this narrative are rural white gentile cishet people. And this is where anti-modernist ideas show their true face. The city in western countries are often more diverse than rural areas. It’s where jewish, black and queer people tend to live.

The urban intellectuals who have lost touch are often jewish.. Anti-modernism is often anti-semitism. In the US, this kind of anti-urban discourse is centered on New York because of its large Jewish population.

Thus anti-modernist thinking is intimately tied to anti-semitic thought. The negative reaction to Arnold Schönberg’s atonal and twelve-tone music is deeply tied to his jewish identity and anti-semitism. There was a scandal about how this jewish composed worked within the austro-german tradition, yet dared to make his own innovations to it. He was seen as “perverting” and “degenerating” that tradition.

It’s also homo- and transphobic. The unnatural “lifestyles” in such anti-urban discourses are often queerness. LGBT people tend to move to cities and form communities there. It’s no accident that the modern LGBT movement was essentially born in Berlin, or that the Stonewall riot happened in New York. And this is baked into anti-urban discourses. Since at least the 1920s, “the unnatural results of technology” condemned by anti-modern discourse is frequently medical transitions. The concept of degeneracy which I’ve written about here is closed tied to both this kind of homo- and transphobia and anti-Semitism.

Of course the kind of romantic anti-urbanism and anti-semitism existed in the 1800s, prior to modern art music and literature. Yet such discourses lead naturally to an anti-modernist ideology in the 1900s. All these ideological currents were often tied together with a romantic nationalism. The white gentile common people were of a specific nation, a specific ethnic and racial breed.

And in anti-semitic thinking, the point of the conspiracy of Jewish intellectuals is to weaken and control those white gentiles. In anti-semitic thinking, queerness is part of a Jewish plot to weaken the genes of various white peoples. Queerness is not viewed as something natural, but something induced by modern society, something you are recruited into. This is what the concept of “degeneracy” refers to.

And modern art was part of this conspiracy. Traditional forms of art are associated with traditional Christian values. So modern art becomes another Jewish conspiracy to weaken the mind of gentile white westerners and turn them away from these healthy Christian values.

This romantic nationalist and anti-semitic ideology originated in the 19th century and in the 20th century developed into fascism. As Umberto Eco put it “The first feature of Ur-Fascism is the cult of tradition.“ And “Traditionalism implies the rejection of modernism.“

The nazis drew upon the anti-semtic romantic German nationalism of the Völkisch movement, extolling the virtues of “blood and soil.” They praised the simple German farmer who worked that soil and had pure German blood in his veins, and put him against the degenerate Jewish socialists in Berlin.

The nazis put the ideology I described into action when they came to power in 1933. In Berlin they destroyed the first modern LGBT movement, which was centered in Berlin. The nazis destroyed Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexology, where the first modern medical transitions were performed. They banned modernist art, and put on mocking exhibitions of “degenerate art” And of course, initiated a persecution of the Jews that culminated in what is probably the worst genocide in history.

All of these things are connected by the same romantic nationalist and anti-semitic ideology, of which nazism was just one particular variant.

So why I’m writing all this historical context? It’s because these ideas have not gone away, but in fact grown stronger with a fascist revival. Modern fascists trumpet this idea from their government offices.

And a kind of anti-intellectual and anti-modernist discourse has thrived outside of explicitly fascist environments. The idea that modern and non-figurative art, literature and films is too weird, too inaccessible and meaningless, created by (urban) intellectuals who have no connection to the concerns of ordinary people in the real world are ideas that you can find here on tumblr in spades. People will uncritically share whining about modern art from some “traditionalist” account on social media, it is worrying. Again, you don’t have to for example listen to atonal music, but this anti-intellectual dismissive attitude is not some innocent aesthetic preference.

And identifying as a leftist is no antidote. When the Soviet Union turned to romantic Russian nationalist ideas under Stalin, it lead to a cultural policy dictating a traditionalist and figurative and tonal aesthetic (called socialist realism). And it was tied to anti-semitic campaigns against “rootless cosmopolitans.” The campaign against atonality (so-called “formalism) under the Zhdanov doctrine and the anti-semitic campaign against foreign influences and “rootless cosmopolitans” were part of the same idea.

And since the 1960s/70s, the hippies have uncritically recuperated romantc anti-urban, anti-industrial and agrarianist ideas, and given it a leftist sheen. How shallow this leftism can be when you witness the many cases of seemingly leftist New-ager hippie turning to a q-anon conspiracy theorists.

And of course a lot of this nonsense comes under the heading of ecology or environmentalism. Not that I’m against ecology or environmentalism, I’m a eco-socialist. But romantic environmentalism ought to be distinguished from a political, scientific and rational approach to the present ecological crisis.

Derrick Jensen and his radical environmentalist group Deep Green Resistance becoming extremely transmisogynist was honestly no surprise to me, such ideology was implicit in Jensen’s romantic anti-industrial and anti-urban rants all along. Of course his romantic idealization of the natural excluded trans people as unnatural products of the industrial and urban society he hates. Nothing else makes sense in Jensen’s ideological framework, anti-queerness has been part of anti-urban ideology since the 1800s. It’s part of the ideological tap roots of such romantic environmentalism

Of course TERF ideology in general is a similar example of 70s hippie ideology giving this romantic and traditionalist idealization of the natural a false leftist and feminist sheen. Cis women’s womanhood is natural and biological and thus good. Whereas trans women are the products of a “frankensteinian” science gone wrong, as Mary Daly put it most clearly.

Radfem ideology has basically the same view of what is acceptable femininity as fascist traditionalists. Modern “sexualized” femininity, high heels and make-up is wrong and degenerate, whereas the feminine ideal of women as mothers is seen as good and natural.

This all might piss off all the groups I described in this from M-Ls to deep ecologists to radfems to people who just virulently dislike modern art. But this is just pointing out the ideological taproots of this form of thinking in 1800s romanticism. And that is not an innocent tradition. The idealization of the natural or agrarian in contrast to the degeneracy of modern urban living is not an innocent idea. It’s tied to racism, particularly anti-semitism, it’s tied to homophobia and transphobia, and ableism (the disabled lives which are reliant on modern medical technology are seen as another modern degenerate aberration).

And I say bollocks to all that. I’m happy to live in a city now. I used to live in a tiny rural town of about 300 people, it was miserable. Having my own apartment in the city, away from my father and the judgemental eyes of my neighbours enabled me to realize I’m a trans woman and transition. I’m happy that I have access to modern medical technology. It’s actually awesome that I take synthetic hormones that enable me to change my hormonal sex and I’m currently undergoing electrolysis to remove my facial hair. I hope to get surgery soon, so I could complete my frankensteinian transformation. Being an inhabitant of a degenerate modern industrial city far away from the judgements of narrow-minded racist and transmisogynist small towners is good, actually.

And I enjoy the art us urban intellectuals put out, even if it’s weird and noisy. Again, it’s all connected. Atonal and serialist music started with a Viennese Jewish composer, Schönberg. It’s no coincidence that perhaps the most important modernist novel, James Joyce’s Ulysses, celebrates a city, Dublin, and features a Jewish protagonist, Leopold Bloom. His “cylcops” in the book’s analogy to the Odyssey is an anti-semitic romantic Irish nationalist, who loses his debate with Bloom.

This continues in the modern day. Present-day Transfem musicians infamously tend to make industrial music and noisy hyperpop. Probably the best guide to this is the fantastic essay “A Sex close to Noise.” by Leah Tigers. It’s a great essay that maps the affinity trans women musicians have for “noisemaking.” She draws attention to Throbbing Gristle’s slogan “Industrial music for Industrial people.” And notes that trans women are “for better or worse, industrial people. Often, we make industrial music.“

And that gets to the central thrust of this text. Hatred of industrialism can’t be separated from a hatred of “industrial people”, like trans women. Hatred of the urban can’t be separated from the anti-semitic, racist, homophobic and transphobic horror that the city contains jewish, black, and queer people. And a hatred of modern art can’t be separated from that legacy. Condemning modern music as just “noise” can’t be separated from condemning the jewish people and trans women who cause all that noise.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

♪ zur musik ♪

Arnold Schönbergs »15 Gedichte aus ›Das Buch der hängenden Gärten‹« entstanden in den Jahren 1908 und 1909. Das Werk erlebte seine Uraufführung durch die österreichische Sängerin Martha Winternitz-Dorda und die Pianistin Etta Werndorf am 14. Januar 1910 in Wien. Bei den fünfzehn vertonten Gedichten handelt es sich um eine Auswahl aus einer größeren Sammlung des deutschen Dichters Stefan George. Die Komposition markiert einen Bruch mit der traditionellen Harmonielehre und dem bis dahin üblichen Umgang mit Dissonanzen. Zusammen mit den Drei Klavierstücken op. 11 steht »Das Buch der hängenden Gärten« am Beginn von Schönbergs so genannter »atonalen« Phase.

Georges »Bücher der Hirten- und Preisgedichte, der Sagen und Sänger und der Hängenden Gärten« erschien erstmals 1895. Das Buch unterteilt sich in drei aneinander anschließende Teilbände, wobei Schönberg sich vor allem durch den dritten angezogen fand. Die dort versammelten 32 Gedichte geben die Geschichte eines jungen Prinzen und seines sexuellen Erwachens in einem paradiesischen Garten in poetischen Bildern wieder. Das beherrschende Thema ist die Verwandlung: ein naiver Jugendlicher betritt den Garten, um schließlich die Erfüllung aller Sehnsüchte mit seiner Geliebten in einem Blumenbett zu finden. Wenn er nach diesem Erweckungserlebnis von ihr verlassen wird, zerfällt auch der Garten.

Charles Stratford | © Arnold Schönberg Center

1 note

·

View note

Text

Roberto Gerhard y su maestro

[Roberto Gerhard, Arnold Schoenberg y Anton Webern en las Ramblas de Barcelona (1932) / ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG CENTER]

Akal publica un libro con la correspondencia entre Arnold Schoenberg y su gran discípulo español

El 21 de octubre de 1923, Roberto Gerhard escribe desde Valls, en Tarragona, donde había nacido 27 años atrás, a Arnold Schoenberg, por entonces una de las más eximias (y polémicas) figuras de la música europea. En un estado de penoso bloqueo creativo, Gerhard confiesa su depresión anímica y pide al maestro austriaco le brinde la oportunidad de formar parte de su círculo vienés. Aquel fue el inicio de una relación que superaría el mero nexo entre maestro y alumno y que sólo terminaría con la muerte de Schoenberg en 1951.

Akal publica ahora, coincidiendo con el 150 aniversario del nacimiento del creador del dodecafonismo, la correspondencia entre ambos músicos en traducción y edición crítica de Paloma Ortiz-de-Urbina. Son en total 81 documentos (cartas, postales, telegramas), la mayoría en alemán, entre aquella primera de 1923, que el vienés conservaría toda su vida, y una última misiva fechada el 28 de junio de 1965 y dirigida a Gertrud, la viuda de Schoenberg, ya que el volumen recoge las cartas que el compositor español y su esposa vienesa (Leopoldine Feichtegger, Poldi) se cruzaron con Gertrud Schoenberg tras la muerte del esposo.

El material está organizado en cuatro partes. En la primera se recoge la correspondencia (breve, nueve documentos) que entre 1923 y 1924 acabó con Gerhard convirtiéndose en el discípulo español de Schoenberg. La segunda es la que marcó la relación entre ambas familias: por razones de salud, Schoenberg pide en 1930 a Gerhard, recién casado, le busque una casa para pasar una temporada en Barcelona, temporada que acabaría extendiéndose entre octubre de 1931 y mayo de 1932, un tiempo en el que, entre otras cosas, nacería en Barcelona Nuria Schoenberg, que con el tiempo sería la esposa de Luigi Nono. El tercer capítulo se inicia en 1934 con una primera carta de los Schoenberg, recién exiliados, desde Massachussets, y termina con la muerte del maestro vienés en Los Ángeles, cuando Gerhard llevaba ya también más de una década de exilio en Cambridge, donde acabaría nacionalizado británico y moriría. En ese tiempo ambos compositores no llegarían jamás a verse. La cuarta sección recoge la correspondencia de los Gerhard con Gertrud.

Aunque resultan indudable los lazos de amistad que se generaron en Barcelona entre las familias, en la correspondencia se aprecia un grado notable de asimetría. Gerhard escribe siempre como el devoto discípulo y el amigo entregado y preocupado por todo, mientras que Schoenberg, más allá de las fórmulas de cortesía habituales, que, sin duda, traslucen también la buena sintonía entre ambos, recurre al amigo catalán tratando de resolver sus problemas: buscarle casas (con pistas de tenis cercanas), gestionar una prevista gira de conciertos por España en 1932-33 (al final frustrada), encontrar acomodo a su hijo Georg (hijo de su primer matrimonio, con Mathilde Zemlinsky), que sufre en Viena el antisemitismo, terciar con Casals para el estreno de su Concierto para violonchelo (arreglo de una obra de Monn, compositor del XVIII)...

Si bien los dos músicos apenas intercambian comentarios sobre cuestiones profesionales técnicas (con la excepción de una carta de Gerhard) ni tampoco son demasiado profundas las referencias políticas, la situación internacional se filtra en la correspondencia de los años 30, tanto como elementos de la vida musical barcelonesa (y española) de la época, afectada por la crisis económica mundial que llegó también al país. Finalmente, este volumen recoge una parte ínfima de las más de tres mil cartas que se atribuyen al vienés (una selección fue publicada ya en español por Turner hace décadas) y ayuda a conocer algunos hechos de la vida y el trabajo de ambos compositores y a entender claves de su relación con España.

[Diario de Sevilla. 31-03-2024]

Schönberg y Gerhard. Correspondencia

Paloma Ortiz-de-Urbina (ed.)

Madrid: Akal Música, 2024.

217 páginas. 23 €

0 notes

Text

The young Austrian mezzo-soprano Patricia Nolz is the winner of the Casinos Austria Rising Star Award 2019 and was awarded at competitions such as the ÖJAB Music Competition Vienna and the Osaka Music Competition in Japan. In 2019 she was an Anny Felbermayer scholarship holder. She is right now a student at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna. Since 2019 she has been studying for a Master’s degree in Lied and Oratorio with Florian Boesch and Claudia Visca. On the opera stage Patricia has so far performed at the Schönbrunn Palace Theatre (Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel, Filipjewna in Eugene Onegin, title role in Oreste, Cherubino in Le nozze di Figaro, Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia), among others, at the Arnold Schönberg Center, at the Clairmont Concert Hall Tel Aviv, at Schloss Perchtoldsdorf (Dido in Dido and Aeneas), in Soligen and Remscheid (Bradamante in Alcina), as well as at the Herbsttage Blindenmarkt (Orlofsky in Die Fledermaus). In autumn 2020 she was highly acclaimed for her excellent debut as Cherubino in a new production of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro at the Theater an der Wien, conducted by Stefan Gottfried and directed by Alfred Dorfer. Patricia Nolz was a member of the Opera Studio of the Vienna State Opera for 2 years.

Dear Patricia, thank you for accepting our invitation! It’s always a pleasure to chat with young and talented opera singers. You just announce on your Instagram account that you will be an ensemble member of Wiener Staatsoper in the season 2022/2023. What does this step mean to your career? How do you think it will change from this point on?

After 2 seasons in the Opera Studio (Young Artist Programme) of Wiener Staatsoper, it is a big honor to continue my journey in this house in the ensemble. I am looking forward to expanding my repertoire further, refining my craft and artistry and working together with all the lovely people in Wiener Staatsoper I got to know in the past years. Interestingly, my every-day-worklife will not change dramatically, since all of us studio-members were involved in nearly every production of the past 2 years, and therefore I have a good idea already about how the life in the ensemble looks like. But of course I am happy to announce that I will be singing several bigger roles next season, such as Rosina in Barbiere di Siviglia, Zerlina in Don Giovanni and Cherubino in Le Nozze di Figaro.

Speaking of Wiener Staatsoper, since the season 2020/2021 you are a member of the Opera Studio of the Wiener Staatsoper. What do these Opera Studios look for in a young singer at the audition? What can you tell us about your experience there?

We recently had our Opernstudio-farewell-concert and I would like to quote the head of our Opernstudio, Michael Kraus: “When I first became head of the Opera Studio I started to look for singers who are the full package: talent, intelligence, diligence and a vision for themselves.” I respect Michael Kraus tremendously for the work he did and is still doing, particularly when it comes to the casting process. He takes the time to listen to hundreds of recordings by himself and invites the singers he wants to listen to live for a so-called “Arbeitsprobe”. The difference to a regular audition is that he is not only listening and requesting to listen to certain arias, but he actually works with the applicants to see how a person behaves in a collaborative situation, responds to criticism, musical suggestions and general feedback. My personal experience in the Opera Studio has been nothing, but wonderful. The whole program was really tailored to benefit all of us singers individually as much as possible. I got the opportunity to audition for several different conductors and casting directors, I participated in numerous masterclasses, and of course, probably most importantly, I got the opportunity to perform on the stage of Wiener Staatsoper dozens of times over the past 2 years, next to the most renowned singers in the world. Nothing can really inspire growth as much as these experiences.

reposted from https://opera-charm.com/

0 notes

Video

youtube

Helmut Lachenmann - Serynade (1997/98) Jan Gerdes Klavier

Live- Mitschnitt Arnold-Schönberg- Center Wien 22.1.2020

3 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Song: Swing Doors / Jazz Interlude

Composer: Allan Gray

Director: Billy Munn conducting Charles Brull’s Dance Orchestra

Record Label: Charles Brull - A Harmonic Private Recording CBL 37

Released: ca. 1950

Location: Galaxy News Radio

Continuing on into our foray on the use of library music (also known as stock music or production music) used in the Fallout series, here’s another instrumental track heard on GNR. As with all of the instrumental pieces, Three Dog makes no formal introduction of this song on the radio.

Unusually for library music, this song is listed right alongside the other more familiar vocal tunes in Fallout 3′s end credits. However instead of the plethora of copyright information, artist name, and record labels, all of that is replaced with “Courtesy of APM Music, Inc.”

APM Music is one of the well known providers of production music, combining various music libraries and underscoring countless cartoons, films, and TV shows, yet almost anonymously.

Curiously, of the music reprised from GNR in Fallout 3 into DCR in Fallout 4, the ones that didn’t make the jump all came from APM Music.

More on that later.

As is the case with library music, finding artist and recording information is extremely difficult as these songs were never meant to be sold to the public, instead being exclusively used for the film and TV industry. What follows is an attempt to extricate this information.

Note: Library music is typically identified by composer or emotion. Very little can be confirmed about the musicians who performed on the recording. This side is interesting as it features Billy Munn conducting who composed the piece on the flip side of the record.

About the composer

Arnold Schönberg's 1926 Berlin master class. Courtesy of the Arnold Schönberg Center, Vienna.

Left to right: Adolph Weiss,Walter Goehr, Walter Gronostay, Winfried Zillig, Arnold Schönberg, Erich Schmid, Josef Rufer, and Józef Żmigrod (Allan Gray, far right). Photograph taken by Gerhard Roberto who appears in a similar photograph, having swapped places with Adolph Weiss (far left) as photographer (who managed to decapitate Mr. Gray and Mr. Zilig).

There are unfortunately very few confirmed extant photographs of Allan Gray. Even commercial sheet music covers are coming up empty.

However, he is slightly more documented as a film composer.

Born Józef Żmigrod in 1902 in Tarnów, Austria-Hungary (what is now Poland), he was trained in Berlin under Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg. By the 1920s, he worked his way into the heart of the Berlin art scene in various caberets including Max Reinhardt's Deutsches Theater.

The 30s brought composing work in Germany’s booming film industry until the impending war hastened a removal to Britain in 1936. Some of his more memorable work was with the British film-making partnership of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, otherwise known as “The Archers”. Perhaps his best-known was his scoring in the 1946 film A Matter of Life and Death (released in the US as Stairway to Heaven) and the 1951 film The African Queen.

He would continue to work on as composer to over 50 films and TV shows.

For further reading:

Two biographies and a partial discography on The Powell & Pressburger Pages.

Entry in the British Film Institute.

About the recording

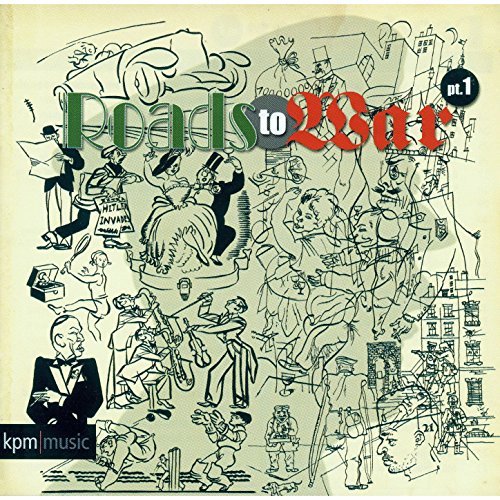

While the original record label belonged to Charles Brull, it was eventually acquired by famed UK library label KPM, which is managed in the States by APM Music.

CBL 37 is an odd mixture of spinning at 78 rpm and being made of vinyl, meaning you’d need specialized equipment for playing it.

As far as I can tell, it was first reissued in 1999 as a CD, KPM 0398 Roads to War (1933-1945) Part 1. You may find that a total of 3 songs from Fallout 3 also appear in the track listing. Here, the song picked up a description as Track No. 44:

“English dance band swing”

So as to ascertaining the date of the recording. If the CD is to be believed, this track was recorded sometime between 1933 - 1945. I have found no evidence to confirm this.

The record label itself does not have a date of publication. However, an image of Bert Graves’ “Cool Cucumber”, CBL 53, a mere 16 away from 37, shows in a very small subtitle: “Recording First Published in 1957″.

Charles Brull seems to have also provided discs for broadcast on the BBC as test pattern or test card music. You may recognize the same three tracks appearing under 1954.

1954 might have been the end of it except for some entries from our friends in the Nordic countries.

The Danish Cultural Archive or the Dansk Kulturarv has digitized the radio set-lists of the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR). The archives indicate that Allan Gray’s “Swing Doors” was played over the air in 1960 and 1961.

Meanwhile, the Swedish Film Database records that Allan Gray’s “Swing Doors” was used in the soundtracks for quite a few films, Åsa-Nisse som polis (1960), Swing it, fröken! (1956), Tarps Elin (1956), Resa i natten (1955), Flottans muntergökar (1955), Enhörningen (1955), Bröderna Östermans bravader (1955), and Biffen och Bananen (1951).

Since “Jazz Interlude” and “Swing Doors” are two halves of the same record, it is likely they were recorded around the same time. Since “Jazz Interlude” was used in a 1950 Swedish film, it would follow that “Swing Doors” came along close on its heels.

Listen to the flip side “Jazz Interlude” here.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Komposition mit zwölf Tönen. Schönbergs Neuordnung der Musik / Composition with Twelve Tones. Schönberg’s Reorganization of Music, Curated by Eike Feß, Arnold Schönberg Center, Wien, March 15 – December 29, 2023

Image: Arnold Schönberg, Bläserquintett op. 26. Reihendrehscheibe, 1926 [Arnold Schönberg Center, Wien]

#art#music#visual writing#geometry#exhibition#arnold schönberg#eike feß#arnold schönberg center#1920s#2020s

56 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Moses and Aaron in the holy Bible FREE ALBUM DOWNLOAD https://page.co/mBjB

https://songoflove.bandcamp.com/

http://songoflove.org

https://www.patreon.com/songoflove

https://www.facebook.com/songoflovemetal

https://www.reverbnation.com/songoflove

https://soundcloud.com/songoflove

https://twitter.com/Songoflove2018

https://noisetrade.com/songofloveSONG OF LOVE VIDEOS

Song of love stagger the devil https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4RhuTy3l04s

Song of love A girl named clit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R09LDR3-JPA

Song of love Orgasm planet https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O95h8vayNoA

Song of love Pride https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xUODPIpTWUc

Song of love Wake the world https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5ocHQDLUvo

Song of love Metal Jesus https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tz9gyw-A2gc

Seeking new heavy metal bass riffs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fX6YMqiK65U

This how bass guitar should sound https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tj0mDwADIKM

Amazing bass guitar riffs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhRyayLQiIg

Meaning of the song a girl named clit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QlRsCQUFDV8

A girl named clit FAIL OVERDRIVE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=074DwjGlbME

Moses and Aaron in the holy BIble https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qz5l8llHrtEMoses and Aaron in the holy BIble were led by God to bring God s people out Moses and Aaron

in the holy Bible were God s spokeperson from people to whom JESUS came to save the world Moses and aaron in the holy BIble Moses signifies those faithful to God Aaron the christians not that faithful moses and aaron in the holy BibleMoses and Aaron (original title in German, Moses und Aron) is an opera in two acts with music by Arnold Schönberg and a libretto in German by the composer himself. The third act was incomplete. The script is based on the book of the Exodus from the Bible. It is a fully twelve-tone work. moses and aaron in the holy bibleMoses and Aaron has precedent in an earlier work agitprop Schönberg, Der Biblische Weg ("The Way of the Bible", 1926-27), which represents a dramatic response to the rise of anti-Semitic movements in the world of speech German after 1848 and a deeply personal expression of his own crisis of "Jewish identity". The latter began with a face-to-face encounter with the anti-Semitic upheaval in Mattsee, near Salzburg, during the summer of 1921, when he was forced to leave the hotel for being a Jew, moses and aaron in the holy biblealthough in fact he had already converted to Protestantism in 1898. It was a traumatic experience that Schönberg would frequently refer to, and of which a first mention appears in a letter addressed to Kandinsky (April 1923): "I have finally learned the lesson that I have been forced to teach this year, and never I am not a German, not a European, in fact I am hardly a human being (at least, the Europeans prefer the worst of their race before me), but I am a Jew. "2 moses and aaron in the holy bibleSchönberg's statement echoes that of Mahler, a convert to Catholicism, a few years before: "I am three times stateless: as a Bohemian among the Austrians, as an Austrian among the Germans, and as a Jew in the whole world. I am an intruder everywhere, welcome in none. "3 moses and aaron in the holy bibleMattsee's experience was destined to change the course of Schönberg's life and influence his musical creativity, leading him first to write Der Biblische Weg, in which the main character Max Aruns (Moses-Aaron) is partially inspired by Theodor Herzl, founder of modern political Zionism; then, to proclaim in Moses und Aron his inflexible monotheistic creed; and finally, after his official return to Judaism in 1933, moses and aaron in the holy bibleto embark for more than a decade on an indefatigable mission to save European Jews from the fate that awaited them. Der Biblische Weg must be considered both a personal work and a political one. Moses, at the center of the biblical exodus, had become from the time of Heine to that of Herzl and Schönberg, the ideal incarnation of a national and spiritual redeemer.2 moses and aaron in the holy bible

0 notes

Text

Music Review: Space Quartet - Space Quartet

Space Quartet Space Quartet [Clean Feed; 2018] Rating: 4/5 Space, for left-field musician Rafael Toral, is neither a final destination nor a beginning — at least space as it’s normally understood. Whether suspended in the gossamer haze of his early ambient work, honed to precarious improvisations in his Space Program series (which recently concluded after a 13-year voyage), or, freed from paternal stricture in his present projects, gone renegade past the pearly gates of free-jazz, Toral’s work has little to do with stargazing and everything to do with positioning. Advancing a jazz-infused language that Toral first developed during the Space Program, Space Quartet aerate compositions with brisk improvisations. Quite fittingly, the cover art for the group’s self-titled debut pays homage to the aesthetic cool of 1960s-era jazz label Blue Note — it echoes the shuttered cover of Freddie Hubbard’s Hub-Tones, specifically — while sharing an easel with De Stijl painters, recalling Piet Mondrian’s kinetic rectangles, formed using only black, white, and primary colors. But Space Quartet don’t make hard bop nor do they play standards. Electronic instruments serve a role normally reserved for culprits like guitar, piano, or saxophone, with Toral’s melodic feedbacks and hacked amplifiers pouncing and twining with Ricardo Webbens’s modular synthesizer and custom electronics. The dueling voices conjure exotic bird calls transmitted through radio static, shrieking in beautiful discord. No less vivacious, the rhythm section — featuring Hugo Antunes on double bass, and João Pais Filipe on drums and handmade gongs and bells — teems with power and precision, rumbling with rib-rattling thunderclaps. Evoking fertile landscapes, Space Quartet’s four tracks reference places in Portugal where the album was recorded: “Lisboa,” Europe’s second oldest capital, predating London, Paris, and Rome; “Porto,” a northern port resting near the mouth of the River Douro; “Coimbra,” a city in central Portugal housing the country’s oldest academic institution; and “Lisbon II,” Lisbon being the Western term for Lisboa, also the site of Toral’s birthplace. Forget about passports: one can nearly taste grapes plucked along the Douro, hear fields of wheat toss in the gentlest breeze, see Roman ruins sunning on bare hillsides. Space Quartet by Rafael Toral = Neither a tour guide nor a band leader, Toral considers himself, more poetically, “an ‘architect’ of spontaneous configurations.” The sonic structures he designed for Space Quartet involved isolated interactions with each musician. During a three-year editorial process, Toral guided the group’s musical materials using a meta-score, evaluating how well they served compositional functions concerning rhythm, density, timbre, articulation, and even mood. When the group gathered together in November 2017, the compositions were brought to life for the first time. Only the musical materials, which are laid out in a timed score, were pre-established; each musician decided, on their own, when and how to perform their chosen materials, maintaining the freedom and accountability to improvise. “Lisboa I,” the album’s smoldering 18-minute opener, proudly confirms the group’s jazz allegiance. Each musician enters sequentially, allowing space for the others to pause. A ghostly melody warbles from Toral’s feedback systems, lost in soliloquy, before the bass yo-yos through center stage; drums splatter overhead, followed by loopy electronics. After lathering to a frenzy, the group pulls back, unraveling in moonlight. “Porto,” meanwhile, seeps from foggy riverbanks resembling Toral’s sporadic side-project MIMEO — an electroacoustic collective that channels sheets of noise sometimes soft enough to huff from a humidifier, other times dense as magnetic storms. While “Porto’s” electronics blink like fireflies, Pais Filipe massages gongs in sleepy washes. Finding new knees in old sea legs, the bass creeps down a noir-ish alley, rallying the group to one final flurry. Ablaze from the start, “Coimbra” ticks, clicks, and clatters like a watchmaker’s shop gaining sentience one stroke past midnight. The bass seesaws in bristling brush strokes; the drums thrash in cyclical cells; Toral whorls feedback as Webbens gargles white noise. In the concluding passage, Antunes weaves a knotted melody that would raise Arnold Schönberg’s head. Finally, the walls are not crawling with field mice, but the squeaking chatter on “Lisbon II” could rouse a rodent’s nest. Beneath the whiskered fray, the bass signals in Morse code, tangling with buckshot drum blasts. Webbens tears through some feverish dimension conceived deep in a Hawking dream. Amid spasms, Toral’s feedback shakes like a landlocked siren, wailing higher, higher, higher. Although old-school jazz fans might question the quartet’s instruments or squint at its lexicon, they just might savor the syntax, flick a match at its breathless exuberance. Music, for Toral, is no passing recreation. Dark matter be damned; Space Quartet explore a dimension within which all things exist: “Through being mindful of space,” Toral explains, music can become “a metaphor for a way of relationship to others and to the environment.” And we believe him. One need not cross the stratosphere to commune with the future. Reaching further than NASA’s probes, forging a field both singular and universal, Space Quartet celebrate a here rather than a there: a place we all share — together. http://j.mp/2L7J4nN

0 notes

Photo

O R B I T S C H Ö N B E R G I -

Warum Halbgott sein wollen, warum nicht lieber Vollmensch?

3. MAI 19:30H ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG CENTER WIEN

»Wenn jemand, um was erzählen zu können, eine Reise tut, dann wählt er doch nicht die Luftlinie!« Arnold Schönbergs Aphorismus ist das Motto einer spektakulären Konzertserie des Asasello Quartetts und von Hololulu Star Productions, die den Hörer auf gewundenen Pfaden durch Musik- und Zeitgeschichte führt. Gemeinsam Grenzen überschreitend öffnen sich Künstler und Publikum weite Horizonte, die das Quartettschaffen Schönbergs in neuem Lichte erscheinen lassen.

0 notes

Photo

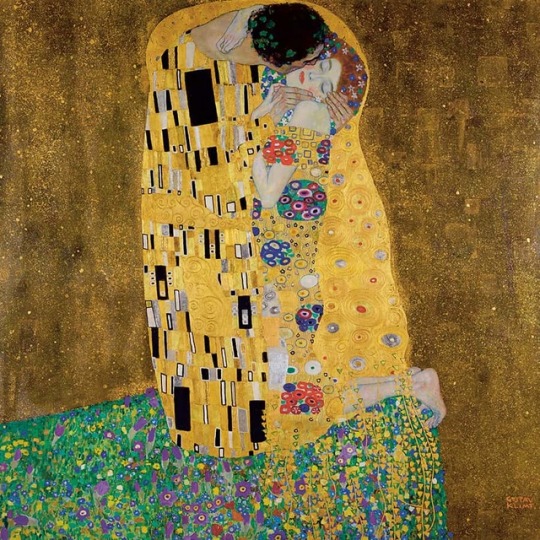

In 2018, Vienna Will Celebrate the Dark, Seductive Art of Klimt, Schiele, Moser, and Wagner on the Centenary of Their Deaths

Article by Sarah Cascone

In 1918, as World War I drew to a close, Europe lost four titans of Viennese Modernism: the artists Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Koloman Moser and the architect Otto Wagner. In honor of the centenary of their deaths, the Vienna Tourism Board is planning a massive citywide initiative, “Beauty and the Abyss,” a series of exhibitions highlighting the impact of these four artists, and a celebration of turn-of-the-century Wiener Moderne, or Viennese Modernism.

“Those four men were ahead of their time, very modern and forward thinking, and unafraid to break taboos,” Helena Hartlauer, a spokesperson for the Vienna Tourist Board, told artnet News. “Celebrating that legacy is a perfect opportunity for the city to showcase that era and its continued influence today.”

Of the four men being honored in Vienna, Klimt may be the most well known, a figure beloved for his erotic portraits of women, the most famous of which are lavishly embellished with gold leaf. His protégé, Schiele, was even more sexually explicit in his depictions of women—so much so that advertisements for “Beauty and the Abyss” featuring his contorted nudes were censored in Germany and the UK.

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1908–09. Courtesy of the Belvedere, Vienna.

The first major exhibition dedicated to Wagner in 50 years will open at the the Wien Museum Karlsplatz in March, while Moser—a prolific painter, graphic designer, and craftsman—will get his due in an exhibition at MAK, the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, home to the archives of the Wiener Werkstätte, an art and design community founded by Moser and Josef Hoffmann in 1903 on the principle of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art.

ADVERTISING

Beyond the four featured figures, “Beauty and the Abyss” takes a deeper dive into the broader cultural movement, looking at the social conditions that allowed modernist art to flourish in fin-de-siècle Vienna: the artistic communities at coffee houses and salons, and the network of collectors supporting the arts, among other factors.

The tourism board started planning the event in early 2016, and thought carefully about what to call it. “Viennese Modernism is different than classical art or Art Nouveau,” said Hartlauer. “It’s not about being only decorative and colorful and pleasant. There’s very often a dark element combined with the beauty.”

Joseph Maria Olbrich (left), artists Franz Hohenberger, Koloman Moser and Gustav Klimt (right) in Fritz Waerndorfer’s garden in Vienna (1899). Photo courtesy of the Viennese Tourism Board. © IMAGNO/ÖNB.

The Österreichische Galerie Belvedere will hold three exhibitions related to the theme. “Austria-Hungary 1918” will showcase work by artists across the Habsburg Empire during the last decade of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, including Czech cubists, Hungary’s Nyolcak group painters, and artists from Slovenia’s Sava group, with a special focus on Klimt and Schiele.

The museum will also spotlight its Schiele collection in “Egon Schiele at the Belvedere” before closing out the year with “Reflections: Klimt in an International Context.” Presented in partnership with the Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam, the exhibition will juxtapose Klimt’s work with that of Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler, among his other influences.

Gustav Klimt, Johanna Staude (1917–1918). Courtesy of the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere.

For his part, Klimt will take center stage at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien with two exhibitions: “The Naked Truth: Klimt Confronted,” featuring his Nuda Veritas, and “Stairway to Klimt,” in which a raised platform extends nearly 40 feet above the grand staircase, offering visitors up-close access to a cycle of 13 Klimt paintings on the upper walls.

“Normally, you simply you just walk by it and you don’t realize what a hidden gem that you have in the staircase,” said Hartlauer. (The museum previously installed the “Klimt bridge” with in 2012, on the occasion of Klimt’s 150th birthday.)

At the Leopold Museum, “Egon Schiele: Expression and Lyricism” will pair the artist’s paintings and graphic works with handwritten letter and poems, as well as documents, photographs, and other personal objects.

Gustav Klimt, The Arts, Paradise Choir, and The Embrace, detail of Beethoven Frieze (1902). Courtesy of the Oesterreichische Galerie im Belvedere, Vienna, Austria © Belvedere, Vienna.

Secession, a contemporary art exhibition space founded by Klimt and a group of artists, including Moser in 1897, will present “Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser and the Art of their Time.” Home to Klimt’s monumental Beethoven Frieze mural cycle (1902), the institution will delve into its early history and feature a recreation of Wreath Bearers, a plaster frieze by Moser of a row of dancing girls that was once a key feature of the building’s architecture.

The Jewish Museum Vienna and Ernst Fuchs Museum in the Otto Wagner Villa will both revisit the turn-of-the-century Viennese salon, where cultural and political discourse thrived, in the respective exhibitions “Arnstein, Todesco, Zuckerkandl: Hostesses and Their Salons Between Art and Politics” and “Old Viennese Salon Culture: Dazzling Stage for a Society.”

Other participating institutions include the Museum of Sound, Gustav Klimt’s Studio, the Arnold Schönberg Center, the Hofmobiliendepot Imperial Furniture Collection, the Literature Museum of the Austrian National Library, House of Museum the Museum of Sound, the Bulgarian Cultural Institute Wittgenstein House, and the Austrian Friedrich and Lillian Kiesler private foundation.

( Source: https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/in-2018-vienna-will-celebrate-the-dark-seductive-art-of-klimt-schiele-moser-and-wagner-on-the-centenary-of-their-deaths-1148405?utm_content=bufferb02b3&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=socialmedia )

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Vienna’s Prodigal Son

Richard Gerstl, “Self-Portrait” (winter 1906-07), india ink on paper, Private Collection

On November 4, 1908, at the age of 25, painter Richard Gerstl committed suicide in his Vienna studio, both hanging and stabbing himself. Gerstl’s suicide was prompted by the discovery of his affair with Mathilde Schönberg by her husband, Arnold Schönberg — the modernist composer and Gerstl’s close friend. Before his death, Gerstl destroyed letters, notes and paintings in his studio, but he left in his wake a body of artwork that reveals a prodigious and untimely talent.

The mythology of the passionate, unstable prodigy, ahead of his time, and untimely in the Nietzschean sense of opposing the currents of one’s time, pervades Richard Gerstl at Neue Galerie, the artist’s first US museum retrospective. Organized thematically, the exhibition includes more than half of the roughly 70 works that have been attributed to Gerstl since his rediscovery by Viennese art dealer Otto Kallir in 1931. The underlying narrative of talent and tumult and the strength of the work beg the question of what would have been had he not ended his life.

Richard Gerstl, “Mathilde Schönberg” (summer 1907), tempera on canvas, Belvedere, Vienna

The answers are various. His absorption and reinterpretation of influences suggests a painter who knew his talents and had the facility and desire to take on new territories of artistic expression. This characterization is supported by the artist’s few extant letters and notes. In the exhibition catalogue he is quoted as saying he is pursuing “entirely new paths” and friends and relatives confirm his convictions.

Curator Jill Lloyd, a specialist in Austrian and German Expressionism, reiterates the theme of the artist’s prescience by exhibiting select works by his contemporaries — most notably Oskar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele, and Gustav Klimt — alongside Gerstl’s paintings.

Klimt, whom Gerstl dismissed as a society painter, rarely sacrificed the physical beauty of his female sitters for inner emotion. Born in 1890, Schiele (represented in the exhibition by a 1917 portrait of Arnold Schönberg), began to gain acclaim the year after Gerstl’s death. Kokoschka, born in 1886, worked in the same period of feverish creative ferment as Gerstl and was, in some ways, more radical. A poet and playwright as well as a painter, his portrait “Rudolf Blümner,” from 1910, portrays the sitter as cross-eyed, with prominent, jaundiced hands and a wraithlike body dissolving into a spatial chasm. Yet Kokoschka’s radical derangements, of his own body as well as those of his sitters, are often infused with allegory and marked by theatricality.

Gerstl, on the other hand, comes across as fiercely focused on exploring his technique and the humanity of his subjects (including himself in his several self-portraits) with a startlingly modern lack of affectation.

Richard Gerstl, “Semi-Nude Self-Portrait” (1902-04), oil on canvas, Leopold Museum, Vienna

The full-length “Semi-Nude Self-Portrait,” painted between 1902 and 1904, while Gerstl was under the sway of Symbolist painters such as Ferdinand Hodler, lacks the maturity of his later self-portraits. His full frontal pose, his body wrapped in a cloth from the waist down, evokes the figure of Christ, an effect heightened by the glow of the cerulean background. But aspects of the artist’s later style, and his disdain for allegory, symbolism, and the Academy, are already apparent: for instance, the spotty brushwork, flecked with light, the amount of surface area allotted to the background and the way it competes with the image of the artist — who all but disappears in later self-portraits, if not for his piercing outward gaze.

The catalogue and wall texts cite van Gogh and Munch as major influences. While van Gogh is present in the complexity of Gerstl’s colors — pastoral palettes in some works, dark earth tones with golden highlights in others — and in his increasingly thick, gestural application, he was equally indebted to Munch’s expressions of existential angst, eventually pushing representation to the brink of dissolution.

Madness underpins “Self-Portrait, Laughing,” dated summer-autumn 1907. Gerstl portrays himself from the shoulders up with a wide grin. The slight unevenness of his facial features, with one brown and one blue eye (the blue left eye popping out against the earth tones), and the sharp slope of his shoulders contributes to the sense of mania, but a greater intensity lies in the interaction between the face and background.

Richard Gerstl, “Self-Portrait, Laughing” (Summer-autumn 1907), oil on canvas, Belvedere, Vienna

Gerstl fills in the background with abrupt, agitated brushstrokes in an earthy brown-beige that reflects his face and clothing. While the mottled background draws attention away from Gerstl’s face, it seems simultaneously to absorb him, infringing on the edges of his silhouette. It comes across as a maelstrom of color cohering at the center into a person, or, alternately, a person in the process of disintegrating.

Gerstl’s abstraction of his subject matter reached an extreme in his late landscapes, many painted while he vacationed with the Schönberg family in the town of Gmunden near Salzburg. In “Small Landscape at Traunsee” (August 1907), loose swirls of paint articulate a blue sky and verdant green meadow; the canvas is bisected vertically by the willowy black line of a tree trunk carved into the thick pigment. “Landscape Study” (September 1907) is further abstracted: broad smears of paint, squeezed straight from the tube or applied with a palette knife, are almost unreadable as a landscape up close.

Richard Gerstl, “The Schönberg Family” (late July 1908), oil on canvas, Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Gift of the Kamm Family, Zug 1969

The following summer, he again vacationed with the Schönbergs in Gmunden. A portrait, “The Schönberg Family” (late July 1908), portrays Arnold, Mathilde, and their two children as pools of paint amid a liquid yellow and green landscape. Gerstl’s style in this and similar works goes beyond Austrian or German Expressionism, laying the groundwork for Abstract Expressionism. Visionary, but conceived from a foundation of van Gogh and Impressionism, it exemplifies the artist’s spirit of formal innovation.

Yet, among his most striking works is a comparatively conventional representation of Mathilde Schönberg from the summer of 1907. Rendered in tempera rather than oil, Gerstl portrays Mathilde as pale and expressionless, dressed in a light-yellow-and-ochre kaftan and seated with folded arms in front of the goldenrod wall and blue doors of the Schönbergs’ farmhouse. Here, the artist’s future mistress is more a void in the pictorial space than its focus.

Gerstl’s self-portraits are equally compelling because he conflates narcissistic self-scrutiny with a sense of humility and his own insignificance. Where fellow Austrian Expressionists Kokoschka and Schiele, and German counterparts, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, represented themselves through sexuality, machismo or gendered self-performance, Gerstl portrayed himself as slipping away. He is off-center and defaced (“Fragment of a Full-Length Self-Portrait, Laughing,” c. 1904); shrouded in shadows (“Self-Portrait in front of a Stove,” winter 1906-1907); and in his final self-portrait, nude and awkward, with a bluish pallor (“Nude Self-Portrait,” September 12, 1908).

Richard Gerstl, “Self-Portrait” (winter 1907-spring 1908), oil on canvas, Leopold Private Collection, Vienna

A small self-portrait on a nearly square canvas (16 3/8 by 15 3/8 inches), dated winter 1907-spring 1908, is more unsettling. Described by Kallir in 1931 as “Head, self-portrait, detail of a larger painting,” and possibly cut from a full-length portrait, the painting, as Gerstl left it, depicts the artist in formal dress from the top of his chest up, against an olive green backdrop. Gerstl, in a three-quarter profile, his head tilted slightly downward, glances, furtively or nervously, at the viewer. Too small to consume the picture plane (his head reaches about three-quarters to the top edge), he seems dwarfed by its space, engulfed by emptiness.

Gerstl’s talent and vision are matched in this painting by its psychological weight. It feels both claustrophobic and unanchored. It would take a world war for his Expressionist peers to expose this level of anxiety.

Richard Gerstl continues at Neue Galerie (1048 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan) through September 25.

The post Vienna’s Prodigal Son appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2f25Uyt

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

sede: MAC – Maja Arte Contemporanea (Roma);

cura: Daina Maja Titonel.

In esposizione sei opere (cinque dipinti e una scultura) di Isabella Ducrot, Angelo Titonel, Leila Vismeh, Janine von Thüngen, Gaetano Zampogna che rendono omaggio al compositore austriaco Arnold Schönberg e agli artisti Pablo Picasso, Edward Hopper, Constantin Brancusi e Francis Bacon.

In tre dipinti il tema dell’omaggio è dichiarato già nel titolo, come nel caso di “Omaggio a Bacon” di Gaetano Zampogna, che recentemente ha tenuto una personale alla Fondazione Umberto Mastroianni. Ispirato alla celebre fotografia di John Deakin, tra le trame di un tessuto a fondo verde con stampe di elefanti, emerge – in forte contrasto – la sfocata e drammatica figura in bianco e nero di Francis Bacon. Il dipinto fa parte del ciclo “Le macellerie” a cui Zampogna sta lavorando dal 2015. Bacon stesso affermava di essere stato sempre colpito dalle immagini di mattatoi e di carne macellata: “Che altro siamo, se non potenziali carcasse? Quando entro in una macelleria, mi meraviglio sempre di non essere io appeso lì, al posto dell’animale”.

Esposta nel 2008 a Roma alla Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, l’opera di Isabella Ducrot (olio e pastello su carta intelata, collage di carta, plastica e tessuti turchi ricamati) è dedicata ad Arnold Schönberg e fa parte del ciclo “Variazioni” (2006-2007), una serie di ritratti di famosi musicisti, generalmente di cultura russa, ma anche italiani come Scelsi e Panni, i quali dal patrimonio musicale della propria terra di origine, hanno attinto ispirazione e hanno convertito vecchie canzoni contadine e nenie religiose in “musica colta”.

Dipinto nel 2011 da Angelo Titonel come si trattasse di un negativo fotografico, e restituito con un ingrandimento spinto, provocatorio e simbolico, il volto di Picasso – mano alla fronte – fissa intensamente lo spettatore e lo cattura. L’opera fa parte di un ciclo di lavori in cui, nell’uso del ribaltamento dell’immagine, l’artista scopre un’ulteriore dimensione della figura, una identità introspettiva volta a cogliere “l’altra faccia” del ritratto.

Di Angelo Titonel è esposto un secondo dipinto, “La biglietteria”, del 1980. In quest’opera l’artista veneto congela in un istante infinito di sospensione la biglietteria di una stazione ferroviaria. L’eco di un silenzio profondo e l’atmosfera malinconica contribuiscono a corroborare una visione di solitudine e irrealtà (o realismo magico). Un’atmosfera così specifica, che potremmo definire “hopperiana”. Non a caso Picasso affermava: “Noi, i pittori, siamo i veri eredi, coloro che continuano a dipingere. Siamo eredi di Rembrandt, Velázquez, Cézanne, Matisse. Un pittore ha sempre un padre e una madre; non nasce dal nulla. ”

E’ di Janine von Thüngen, scultrice tedesca attiva a Roma dal 2000, la testa dormiente in vetroresina. La bocca arcuata, la fronte levigata e tondeggiante sono di brancusiana eleganza. In questa opera l’artista ci conduce nella sua esperienza di madre che osserva il sonno del neonato, sospeso in una dimensione impenetrabile. Janine fissa per sempre quel momento nella sua scultura, a protezione una teca in vetro come una bolla amniotica. Esposta nel 2011 alla Biennale di Venezia nella sua versione in bronzo, l’opera fa parte dell’installazione “WasserKinder” (2003).

L’arte è citazione, sembrano dire le opere esposte. Come nel dipinto “Please smile” (2014) della pittrice iraniana Leila Vismeh che presenta un lavoro all’esposizione “Art Capital” al Grand Palais di Parigi. Una giovane madre, forse una contadina, tiene in braccio un neonato, accanto a lei il primogenito veste un costume rosso a pois bianchi, la bocca imbronciata. Sul fondo un mare azzurro si confonde con il cielo. E tornano alla mente e agli occhi – come un contrappunto – alcuni dipinti di Giulio Aristide Sartorio dove il mare di Fregene faceva da sfondo ai ritratti della elegante moglie con i figli sulla spiaggia; e ancora, per assonanza di quel mondo rurale, rivediamo la pastorella di michettiana memoria.

“Non temo di prelevare da altre arti, credo che gli artisti l’abbiano sempre fatto” aveva detto Lichtestein in un’intervista degli anni Sessanta, convinto che non ci fosse immagine che rielaborata, non potesse rinascere a nuova vita.

#gallery-0-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Hommage - Mostra Collettiva sede: MAC - Maja Arte Contemporanea (Roma); cura: Daina Maja Titonel. In esposizione sei opere (cinque dipinti e una scultura) di Isabella Ducrot, Angelo Titonel, Leila Vismeh, Janine von Thüngen, Gaetano Zampogna che rendono omaggio al compositore austriaco Arnold Schönberg e agli artisti Pablo Picasso, Edward Hopper, Constantin Brancusi e Francis Bacon.

0 notes