#aliya writes

Text

*A Deal With The "Devil," Made For You.*

—or, cover image for my Desperados fanfic. Detailing the gun/chair/blood/Samedi/shadows in the background really made me appreciate life.

Read the story here: http://archiveofourown.org/works/47492977/chapters/119689564

#aliya's art#aliya writes#desperados#wouldn't really think from this image that desperados is a western

1 note

·

View note

Text

𝕴𝖇𝖚 ‡ 𝕲𝖔𝖉𝖉𝖊𝖘𝖘 𝖔𝖋 𝕯𝖊𝖆𝖙𝖍

It's in the blood and this is tradition

She moved with such grace, yet killed with no mercy. One barely had time to take in her beauty before she reaped their souls. After what happened to her, she was going to make sure every man feared her.

No one ever escaped.

So she earned the name Ibu, the Goddess of Death.

#the sims 4#ts4#sims 4#ts4 edit#ts4 render#simblr#simblreen#simblreen 2023#aliya's sims#amongussy#roxy#theseus 08085#as promised here's the edit i said i'd do before japan#it fit spooky season so here we are#ibu is the goddess of death in filipino mythology and roxy is filipino#think of john wick being known as babayaga#i can once again write a 5 page essay on what all this means#the song and her lore all come together for this#yes only i know it#but ANYWAY happy simblreen sorry i disappear and drop a random edit nowadays

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gummies, a short comic

(I’m no writer so bear with me)

Nika is acting strange

grabbing hold of the mechanic’s hand

Chuchu takes Nika to the Earth House dorms to see what’s up

Once standing now her back suddenly against the floor

Chuchu realized

she was the bottom of this relationship

Woah…Nika…

She’s on top of her

uniform unzipped

Where did the tie go?

The mechanic was leaning closer

she’s so…wobbly…ah…she fell over

Nika was now lying beside her making grunting noises

What’s gotten into her?! This isn’t like her at all…

“Nika-nee…”

Wait, what is that?

What the hell?

Gummies?

Is this what’s causing her to act so strangely?

Where did she even get these?!

Chuchu glanced over at Nika

She’s sitting now

and…chewing something..!!

She got it out

Nika on the other hand was now clenching Chuchu’s jacket tightly

She would NOT let go

Damn it Nika…

The mechanic brought the jacket down to Pom-Pom’s feet and pulled

Chuchu reluctantly stepped out of it as Nika kept pulling

The mechanic fell back, jacket in her grasp

Ah…she took my jacket…

Chuchu raised a hand to reach out towards Nika to give it back

but she was hugging it dearly

no clear sign of giving it up

Chuchu blushed

Cute…

She turned around, scratching the back of her neck

Well, it can’t be helped..

She looked back at Nika who was rubbing her face all over her pink jacket

Nika…

Chuchu walked over to her mechanic

squatting down, arms over her knees

Nika fell over to her side, giggling with the jacket in her face

Chuchu chuckled,

“You’re so drunk, Nika-nee.”

This wasn’t the time to play around though

even Chuchu knew that

She placed her hands under Nika and lifted her up

carrying her in her arms

Yeah she can carry her

Nika was taller but it wasn’t going to stop Chuatury Panlunch

Chuchu had notified the other Earthian girls via text to come to the dorms

She explained the situation and handed the near-empty bag of gummies to Aliya

Lilique placed her hands on her knees and looked down at a now sleeping Nika

She was worried

Nika wasn’t looking too good

The three knew they couldn’t take Nika to the nurse’s office

They would get in so much trouble for having these kind of gummies on campus

knowing they wouldn’t even get a chance to explain because they’re Earthians

then again

How did Nika even get these? There’s no way she’d eat these if she knew what was actually in them

Did she not notice the taste? Well, Chuchu didn’t know how they tasted like

For all she knows they could taste the same as regular gummies or even better!

Someone must have given these to Nika, saying they were just normal fruity gummies

Chuchu was going to get to the bottom of this

but for now

she’s going to stay by Nika’s side and look after her

Bonus:

#wow I finished this at 6 am#writing isn't my style but I wanted to provide more context to the images#idk if I’ll continue this but yeahhh#Nika is going to have a big tummyache and headache when she wakes up#but she’ll be okay bc Chuchu is there#and Aliya will provide remedies#this was all an excuse to draw a drunk Nika#which I want to explore more on if I continue this#her drunken state is supposed to reflect on her how she feels about being a go-between and having to endure the torment from the Spacians#bottled up emotions leaking out#that obviously wasn’t shown here but I have ideas#her love for Chuchu spilled out more#wanting to hold onto what she holds dear to her from the fear of losing them because she’s lying to them#nikachu#chunika#nika nanaura#chuatury panlunch#chuchu#gundam witch from mercury#g witch#my art

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright, time for the boys first meeting!... I think(?)

--------------------------------------------

Ages of characters in this*:

Boboiboy: 6

Ali: 3

*unfortunately wiki is not telling me Amato, Dr. Ghazali and Aliya's ages so i won't include that here :(

--------------------------------------------

"Ah, Amato! I'm glad you could come over on such short notice" said Dr. Ghazali

Amato chuckled, "Why wouldn't I come over? You're my friend! Besides the mess of a picture you sent me of your office worried me"

"Heh, now please come i-", Dr. Ghazali was cut off by a yawn. There standing next to his friend was a child "Dada, is this the place you had to go to...?", The child said in a sleepy daze

Dr. Ghazali deadpanned at Amato, "Really?" Amato sheepishly looked away

"I know I know, but she was busy with some work that got handed to her last second and I didn't want to disturb her.", Amato explained as he looked at his child. "That and she won't be back any time soon", chimed in a red spherical robot from behind him.

"Well, let's see what we can do then", Dr. Ghazali replied

"Hmm, you didn't tell me we had guests coming tonight", said a voice.

"Ah, I'm sorry I forgot to tell you", he answered. Aliya, stood behind the Dr. as she looked over at Amato and Mechabot. She carried a small child in her arms

"Hello Amato, it's nice to see you again", she noticed the child clinging to Amato's legs, she gasped "Boboiboy! I didn't know you were coming too", Aliya spoke

The boy looked down in embarrassment , "Didn't want to be alone..."

"Ah, come in sweety",she replied warmly. "Ma, 'mm hungy", spoke the child in Aliya's arms, "I know Ali", she looked at the others "Dinner is ready, you guys should come in, don't want the kids to catch a cold", she then proceeded to give a sharp look to Amato, Mechabot and her husband, "You're lucky the kids are here"

Dr. Ghazali, Amato and Mechabot gulped(can a robot gulp?) as they walked in.

--------------------------------------------

Phew, that was long. Can't write it in one post so I'm gonna split it up in parts... Hopefully i don't forget(remind if i do please, that would be much appreciated)

#writing a fic here for the first time#anxiety go brrrr#LDF AU#Long Distance Friendship AU#The origins of bbb and ali's friendship#weeeeee#ejen ali x boboiboy crossover au#ejen ali#boboiboy#boboiboy galaxy#boboiboy's father amato from mechamato(should i tag this? forget it)#mechamato#dr. ghazali#mechabot#aliya#first fanfic???#idk man#part 1 ig tho

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gundam witch but its a Christmas carol au where delling is scrooge, vim is jacob marley, suletta is bob cratchet, etc.

#ive had this idea rattling around in my brain for a while maybe ill write a fic or draw something who know lol#lilique and/or aliya are definitely the ghost(s) of Christmas past#nuno and ojelo would be the ghosts of Christmas present#ghost of Christmas future could be elnora idk ill have to think about that one#*youtuber voice* who do YOU think would play what character leave your answers in the comments below‼️‼️#gundam#gundam witch#g witch#suletta mercury#delling rembran#the witch from mercury

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heaven's Vault: a variety of verbs

for @laughingpinecone

The sunlight of Iox lay overhead like an animal at rest. Paused in the doorway of the Nightingale, Aliya blinked up at the splintered wing mast. Easier to look at the broken wood than at Mina and Huang. She’d intended to come see them to compare some translations, but had limped into Iox with unnoticed wear on the ship finally collecting its due.

Iox couldn’t get parts as reliably as Elboreth, but would involve fewer people trying to talk to Aliya, at least.

Instead, the complications of their own distinctly Ioxian sort started early.

“Do you need any help with that?” Huang asked, waving from where he stood beside the landing pad with Mina by his side. Aliya still felt a pull between herself and Huang. So much had happened since she had begun to see his polite but unmistakable advances as doors, not walls. She had Enkei on board now, and had walked on ancient flagstones and through sites horrific with the long-gone blood of forced transformations. She hardly felt like the same species as Huang any more.

And yet there was something nice about having someone on Iox she truly enjoyed talking to, as much as they disagreed with each other over everything from philosophy to translations.

“You’re better at linguistics than repairs, and we both know it,” Aliya replied, approaching Huang and thereby taking on the full force of the Ioxian daylight.

Huang's smile was strained but sincere. “I can’t argue with that. Do you still have your robot this time?”

You couldn’t have Enkei, first of all — the empress had to at least make it sound like following you was her idea. “Not a scratch on it,” Aliya said after a moment. “How are you settling in, Mina?”

Iox’s sun put highlights in Mina’s mousy hair. “Found, not lost,” she said. “Not yet.”

Aliya’s smile was genuine, although she still wasn’t sure what to say. She’d imprinted on Mina, wanting the girl to have what Aliya had — the resources and experience of Iox — while also feeling like she herself was more Elborethian than Ioxian. Mina would get to see the moon’s three libraries as much as she wanted now, but she would also find her foot in the mud of university politics.

Huang felt like home for Aliya more than most places did, but he was an antagonym, and meant the opposite, too. Aliya could be comfortable with him near her ship — near an escape route — in a way she couldn’t in the library. One was her turf, the other, his. She could almost forget the Loop as the Nightingale flew. Maybe that was part of why her feelings were up and down: Rivers really did break off a chunk of the soul.

Except, no. Aliya chuckled softly at her own fancy.

“Good. I’ll be repairing the ship, so be careful around the masts,” she said.

“Can I look at your library?” Mina asked. “There are so many new subjects I’m interested in now. I didn’t even know to look for them last time I was on the ship.”

Well, that isn't a surprise. You were so afraid you hardly moved.

“Go ahead. I’ll be working on the outside spar,” Aliya said. If it falls, it will fall outward…

Huang caught her eye as he followed Mina inside. Aliya couldn’t read his expression. It reminded her of a robot’s programmed, flat speech, and for a moment she resented the lack of information. She hadn’t ever wanted to kiss him, hadn’t ever wanted to stay with him. So why did the idea of someone else being with him gall her? She might have scowled, because his gaze flickered with concern before he passed her without modifying his speed.

Aliya looked up at the splintered spar again. That wouldn’t be easy to fix, either.

It took work, to find someone on Iox willing to help a River pilot. Aliya had built up contacts, though, and with some help she had the mast re-bound. It would still need a replacement on a moon with more trees, but it would be able to fly off Iox. By the time they were done she was sweating, her hair mussed. She directed her helper to Myari’s coffers, a perk of technically working on university orders. Myari didn’t need to know — or knew she couldn’t do anything about — how much of Aliya’s initiative was … extracurricular.

As Aliya entered the Nightingale after the job was done, the air immediately cooled away from Iox’s bright light. A squeaking, shuffling noise heralded the presence of the Renaki gecko, although Aliya could not see where it was hiding. Mina stood on her tip-toes to pull a book — a rudimentary dictionary — off the shelf, while Huang stood by the shelves on the other side of the room, tipping his head as he checked for the newest work from a renowned academic he and Aliya both respected (mostly). The portholes turned Iox’s harsh light into a softer blue that cascaded over the ladder, bookshelves, and the red, geometric-patterned carpet. The dusty smell of the ship blanketed the room.

At first, Aliya’s heart sank as she looked around the nooks and crannies of the small ship and realized Enkei was nowhere to be found. Then she remembered that the robot had claimed she had no interest in tarnishing her memories of the glory of Iox, and confined herself to the cockpit. It was a way to both preserve her pride and to not have to talk to anyone new or give out any more information, Aliya figured.

“All fixed?” Huang asked.

“Strea’s newest paper is on the table,” Aliya replied.

“Oh!” He hurried over, but met Aliya’s eyes as soon as the folio was in his hands. He flipped through it, clearly eager to focus on it but torn between trying to be social with both Aliya and Mina.

“It’s good,” Aliya jabbed. “But it still dances around the idea that history might be in the past.”

“That’s a very literal interpretation of the Loop, Aliya,” Huang said idly, without rancor, as if their philosophical arguments had themselves been set in stone to repeat for the next cycle.

Huang started talking to Mina about Strea’s paper, and Aliya sat half-comfortable in the hammock as if she was getting ready for bed during a long journey. The watery light even reminded her of the Rivers.

Maybe what she had really wanted was to sit and listen to someone else’s intelligent conversation. Even if it did have too much of the Loop in it, Huang and Mina used jargon Aliya knew, worked through more advanced versions of concepts she had learned as a teen. It was better than being alone and better than having to talk to someone, because she could just listen. Huang and Mina both wanted Aliya there, wanted her to feel included. She could tell by their glances at her, the sweep of placid eyes. Their voices rose and fell, sometimes authoritative, sometimes curious, sometimes laughing.

(Aliya felt some some resentment, too: they wanted her help, but wouldn’t fly a River to come see her, to enter her world …)

Aliya still grated against the idea of what she wanted from Huang. She’d thought she might love him, if he didn’t love the Loop. Mina matched him on that, though. They would learn beside one another and hold each other in their familiar, comfortable orbits, whereas Aliya was always trying to pull one or the other of them out of true.

It had been what Mina needed to get away from her father. Maybe what she needed now was stability, though.

Maybe what she had needed today was to sit in a library while someone else was working on making sure it didn’t physically fall apart around her…

That didn’t sound bad. Aliya flopped down in the hammock and watched the gecko traverse the ceiling upside down while Mina and Huang muttered to each other across the room. The noise and smell of books comforted Aliya, too. As unlikely as it was, she thought all three of them had that in common.

When they had flown from Renaki to Iox, Aliya had thought Mina’s stillness was religious terror. Maybe part of it had been. As she sat in the same room, though, Aliya relaxed enough to start to understand some of what the ship had been to Mina. The familiar books had been as alien to her as a thousand-year-old inscription was to Aliya. While for Aliya, the familiarity of the Nightongale was what made it feel like home, Mina had the instinct that drove baby scholars: the ability of the unknown to feel instantly familiar. It wasn’t a practical skill, and leaning too much on it made a researcher vague. It was essential in the beginning, though. It could make you sit still with just awe.

Aliya closed her eyes, comfortable.

Things certainly could change. Six to Enkei, small town girl to university librarian, words across generations. It was good to take the quiet comfort where she could get it. Aliya only just recently figured out vault was a verb, after all.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: First image shows large falafel balls, one pulled apart to show that it is bright green and red on the inside, on a plate alongside green chilis, parsley, and pickled turnips. Second image is an extreme close-up of the inside of a halved falafel ball drizzled with tahina sauce. End ID]

فلافل محشي فلسطيني / Falafel muhashshi falastini (Palestinian stuffed falafel)

Falafel (فَلَافِل) is of contested origin. Various hypotheses hold that it was invented in Egypt any time between the era of the Pharoahs and the late nineteenth century (when the first written references to it appear). In Egypt, it is known as طَعْمِيَّة (ṭa'miyya)—the diminutive of طَعَام "piece of food"—and is made with fava beans. It was probably in Palestine that the dish first came to be made entirely with chickpeas.

The etymology of the word "falafel" is also contested. It is perhaps from the plural of an earlier Arabic word *filfal, from Aramaic 𐡐𐡋𐡐𐡉𐡋 "pilpāl," "small round thing, peppercorn"; or from "مفلفل" "mfelfel," a word meaning "peppered," from "فلفل" "pepper" + participle prefix مُ "mu."

This recipe is for deep-fried chickpea falafel with an onion and sumac حَشْوَة (ḥashua), or filling; falafel are also sometimes stuffed with labna. The spice-, aromatic-, and herb-heavy batter includes additions common to Palestinian recipes—such as dill seeds and green onions—and produces falafel balls with moist, tender interiors and crisp exteriors. The sumac-onion filling is tart and smooth, and the nutty, rich, and bright tahina-based sauce lightens the dish and provides a play of textures.

Falafel with a filling is falafel مُحَشّي (muḥashshi or maḥshshi), from حَشَّى (ḥashshā) "to stuff, to fill." While plain falafel may be eaten alongside sauces, vegetables, and pickles as a meal or a snack, or eaten in flatbread wraps or kmaj bread, stuffed falafel are usually made larger and eaten on their own, not in a wrap or sandwich.

Falafel has gone through varying processes of adoption, recognition, nationalization, claiming, and re-patriation in Zionist settlers' writing. A general arc may be traced from adoption during the Mandate years, to nationalization and claiming in the years following the Nakba until the end of the 20th century, and back to re-Arabization in the 21st. However, settlers disagree with each other about the value and qualities of the dish within any given period.

What is consistent is that falafel maintains a strategic ambiguity: particular qualities thought to belong to "Arabs" may be assigned, revoked, rearranged, and reassigned to it (and to other foodstuffs and cultural products) at will, in accordance with broader trends in politics, economics, and culture, or in service of the particular argument that a settler (or foreign Zionist) wishes to make.

Mandate Palestine, 1920s – early '30s: Secular and collective

While most scholars hold that claims of an ancient origin for falafel are unfounded, it was certainly being eaten in Palestine by the 1920s. Yael Raviv writes that Jewish settlers of the second and third "עליות" ("aliyot," waves of immigration; singular "עליה" "aliya") tended to adopt falafel, and other Palestinian foodstuffs, largely uncritically. They viewed Palestinian Arabs as holding vessels that had preserved Biblical culture unchanged, and that could therefore serve as models for a "new," agriculturally rooted, physically active, masculine Jewry that would leave behind the supposed errors of "old" European Jewishness, including its culinary traditions—though of course the Arab diet would need to be "corrected" and "civilized" before it was wholly suitable for this purpose.

Falafel was further endeared to these "חֲלוּצִים" ("halutzim," "pioneers") by its status as a street food. The undesirable "old" European Jewishness was associated with the insularity of the nuclear family and the bourgeois laziness of indoor living. The קִבּוּצים ("Kibbutzim," communal living centers), though they represented only a small minority of settlers, furnished a constrasting ideal of modern, earthy Jewishness: they left food production to non-resident professional cooks, eliding the role of the private, domestic kitchen. Falafel slotted in well with these ascetic ideals: like the archetypal Arabic bread and olive oil eaten by the Jewish farmer in his field, it was hardy, cheap, quick, portable, and unconnected to the indoor kitchen.

The author of a 1929 article in דאר היום ("Doar Hyom," "Today's Mail") shows unrestrained admiration for the "[]מזרחי" ("Oriental") food, writing of his purchase of falafel stuffed in a "פיתה" ("pita") that:

רק בני-ערב, ואחיהם — היהודים הספרדים — רק הם עלולים "להכנת מטעם מפולפל" שכזה, הנעים כל כך לחיך [...].

("Only the Arabs, and their brothers—the Sepherdi Jews—only they are likely to create a delicacy so 'peppered' [a play on the פ-ל-פ-ל (f-l-f-l) word root], one so pleasing to the palate".)

Falafel's strong association with "Arabs" (i.e., Palestinians), however, did blemish the foodstuff in the eyes of some as early as 1930. An article in the English-language Palestine Bulletin told the story of Kamel Ibn Hassan's trial for the murder of a British soldier, lingering on the "Arab" "hashish addicts," "women of the streets," and "concessionaires" who rounded out this lurid glimpse into the "underground life lived by a certain section of Arab Haifa"; it was in this context that Kamel's "'business' of falafel" (scare quotes original) was mentioned.

Mandate Palestine, late 1930s–40s: A popular Oriental dish

In 1933, only three licensed falafel vendors operated in Tel Aviv; but by December 1939, Lilian Cornfeld (columnist for the English-language Palestine Post) could lament that "filafel cakes" were "proclaiming their odoriferous presence from every street corner," no longer "restricted to the seashore and Oriental sections" of the city.

Settlers' attitudes to falafel at this time continued to range from appreciation to fascinated disgust to ambivalence, and references continued to focus on its cheapness and quickness. According to Cornfeld, though the "orgy of summertime eating" of which falafel was the "most popular" representative caused some dietary "damage" to children, and though the "rather messy and dubious looking" food was deep-fried, the chickpeas themselves were still of "great nutritional value": "However much we may object to frying, — if fry you must, this at least is the proper way of doing it."

Cornfeld's article, appearing 10 years after the 1929 reference to falafel in pita quoted above, further specifies how this dish was constructed:

There is first half a pita (Arab loaf), slit open and filled with five filafels, a few fried chips [i.e. French fries] and sometimes even a little salad. The whole is smeared over with Tehina, a local mayonnaise made with sesame oil (emphasis original).

The ethnicity of these early vendors is not explicitly mentioned in these accounts. The Zionist "תוצרת הארץ" "totzeret ha’aretz"; "produce of the land") campaign in the 1930s and 1940s recommended buying only Jewish produce and using only Jewish labor, but it did not achieve unilaterial success, so it is not assured that settlers would not be buying from Palestinian vendors. There were, however, also Mizrahi Jewish vendors in Tel Aviv at this time.

The WW2-era "צֶנַע" ("tzena"; "frugality") period of rationing meat, which was enforced by British mandatory authorities beginning in 1939 and persisting until 1959, may also have contributed to the popularity of falafel during this time—though urban settlers employed various strategies to maintain access to significant amounts of meat.

Israel and elsewhere, 1950s – early 60s: The dawn of de-Arabization

After the Nakba (the ethnic cleansing of broad swathes of Palestine in the creation of the modern state of "Israel"), the task of producing a national Israeli identity and culture tied to the land, and of asserting that Palestinians had no like sense of national identity, acquired new urgency. The claiming of falafel as "the national snack of Israel," the decoupling of the dish from any association with "Arabs" (in settlers' writing of any time period, this means "Palestinians"), and the insistence on associating it with "Israel" and with "Jews," mark this time period in Israeli and U.S.-ian newspaper articles, travelogues, and cookbooks.

During this period, falafel remained popular despite the "reintegrat[ion]" of the nuclear family into the "national project," and the attendant increase in cooking within the familial home. It was still admirably quick, efficient, hardy, and frequently eaten outside. When it was homemade, the dish could be used rhetorically to marry older ideas about embodying a "new" Jewishness and a return to the land through dietary habits, with the recent return to the home kitchen. In 1952, Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi, the wife of the second President of Israel, wrote to a South African Zionist women's society:

I prefer Oriental dishes and am inclined towards vegetarianism and naturalism, since we are returning to our homeland, going back to our origin, to our climate, our landscape and it is only natural that we liberate ourselves from many of the habits we acquired in the course of our wanderings in many countries, different from our own. [...]

Meals at the President's table [...] consist mainly of various kinds of vegetable prepared in the Oriental manner which we like as well as [...] home-made Falafel, and, of course vegetables and fruits of the season.

Out of doors, associations of falafel with low prices, with profusion and excess, and with youth, travelling and vacation (especially to urban locales and the seaside) continue. Falafel as part and parcel of Israeli locales is given new emphasis: a reference to the pervasive smell of frying falafel rounds out the description of a chaotic, crowded, clamorous scene in the compact, winding streets of any old city. Falafel increasingly stands metonymically for Israel, especially in articles written to entice Jewish tourists and settlers: no one is held to have visited Israel unless they have tried real Israeli falafel. A 1958 song ("ולנו יש פלאפל", "And We Have Falafel") avers that:

הַיּוֹם הוּא רַק יוֹרֵד מִן הַמָּטוֹס

[...] כְבָר קוֹנֶה פָלָאפֶל וְשׁוֹתֶה גָּזוֹז

כִּי זֶה הַמַּאֲכָל הַלְּאֻמִּי שֶׁל יִשְׂרָאֵל

("Today when [a Jew] gets off the plane [to Israel] he immediately has a falafel and drinks gazoz [...] because this is the national dish of Israel"). A 1962 story in Israel Today features a boy visiting Israel responding to the question "Have you learned Hebrew yet?" by asserting "I know what falafel is." Recipes for falafel appear alongside ads for smoked lox and gefilte fish in U.S.-ian Jewish magazines; falafel was served by Zionist student groups in U.S.-ian universities beginning in the 1950s and continuing to now.

These de-Arabization and nationalization processes were possible in part because it was often Mizrahim (West Asian and North African Jews) who introduced Israelis to Palestinian food—especially after 1950, when they began to immigrate to Israel in larger numbers. Even if unfamiliar with specific Palestinian dishes, Mizrahim were at least familiar with many of the ingredients, taste profiles, and cooking methods involved in preparing them. They were also more willing to maintain their familiar foodways as settlers than were Zionist Ashkenazim, who often wanted to distance themselves from European and diaspora Jewish culture.

Despite their longstanding segregation from Israeli Ashkenazim (and the desire of Ashkenazim to create a "new" European Judaism separate from the indolence and ignorance of "Oriental" Jews, including their wayward foodways), Mizrahim were still preferable to Palestinian Arabs as a point of origin for Israel's "national snack." When associated with Mizrahi vendors, falafel could be considered both Oriental and Jewish (note that Sephardim and Mizrahim are unilaterally not considered to be "Arabs" in this writing).

Thus food writing of the 1950s and 60s (and some food writing today) asserts, contrary to settlers' writing of the 1920s and 30s, that falafel had been introduced to Israel by Jewish immigrants from Syria, Yemen, or Morocco, who had been used to eating it in their native countries—this, despite the fact that Yemen and Morocco did not at this time have falafel dishes. Even texts critical of Zionism echoed this narrative. In fact, however, Yemeni vendors had learned to make falafel in Egypt on their way to Palestine and Israel, and probably found falafel already being sold and eaten there when they arrived.Meneley, Anne2007 Like an Extra Virgin. American Anthropologist 109(4):678–687

Meanwhile, "pita" (Palestinian Arabic: خبز الكماج; khubbiz al-kmaj) was undergoing in some quarters a similar process of Israelization; it remained "Arab" in others. In 1956, a Boston-born settler in Haifa wrote for The Jewish Post:

The baking of the pittah loaves is still an Arab monopoly [in Israel], and the food is not available at groceries or bakeries which serve Jewish clientele exclusively. For our Oriental meal to be a success we must have pittah, so the more advance shopping must be done.

This "Arab monopoly" in fact did not extent to an Arab monopoly in discourse: it was a mere four years later that the National Jewish Post and Opinion described "Peeta" as an "Israeli thin bread." Two years after that, the U.S.-published My Jewish Kitchen: The Momales Ta'am Cookbook (co-authored by Zionist writer Shushannah Spector) defined "pitta" as an "Israeli roll."

Despite all this scrubbing work, settlers' attitudes towards falafel in the late 1950s were not wholly positive, and references to the dish as having been "appropriated from the [Palestinian] Arabs" did not disappear. A 1958 article, written by a Boston-born man who had settled in Israel in 1948 and published in U.S.-ian Zionist magazine Midstream, repeats the usual associations of falafel with the "younger set" of visitors from kibbutzim to "urban" locales; it also denigrates it as a “formidably indigestible Arab delicacy concocted from highly spiced legumes rolled into little balls, fried in grease, and then inserted into an underbaked piece of dough, known as a pita.”

Thus settlers were ambivalent about khubbiz as well. If their food writing sometimes refers to pita as "doughy" or "underbaked," it is perhaps because they were purchasing it from stores rather than baking it at home—bakeries sometimes underbake their khubbiz so that it retains more water, since it is sold by weight.

Israel and elsewhere, late 1960s–2010s: Falafel with even fewer Arabs

The sanitization of falafel would be more complete in the 60s and 70s, as falafel was gradually moved out of separate "Oriental dishes" categories and into the main sections of Israeli cookbooks. A widespread return to כַּשְׁרוּת (kashrut; dietary laws) meant that falafel, a פַּרְוֶה (parve) dish—one that contained no meat or dairy—was a convenient addition on occasions when food intersected with nationalist institutions, such as at state dinners and in the mess halls of Israeli military forces.

This, however, still did not prohibit Israelis from displaying ambivalence towards the food. Falafel was more likely to be glorified as a symbol of Jewish Israel in foreign magazines and tourist guides, including in the U.S.A. and Italy, than it was to be praised in Israeli Zionist publications.

Where falafel did maintain an association with Palestinians, it was to assert that their versions of it had been inferior. In 1969, Israeli writer Ruth Bondy opines:

Experience says that if we are to form an affection for a people we should find something admirable about its customs and folklore, its food or girls, its poetry and music. True, we have taken the first steps in this direction [with Palestinians]: we like kebab, hummous, tehina and falafel. The trouble is that these have already become Jewish dishes and are prepared more tastily by every Rumanian restaurateur than by the natives of Nablus.

Opinions about falafel in this case seem to serve as a mirror for political opinions about Palestinians: the same writer had asserted, on the previous page, that the "ideal situation, of course, would be to keep all the territories we are holding today—but without so many Arabs. A few Arabs would even be desirable, for reasons of local color, raising pigs for non-Moslems and serving bread on the Passover, but not in their masses" (trans. Israel L. Taslitt).

Later narratives tended to retrench the Israelization of falafel, often acknowledging that falafel had existed in Palestine prior to Zionist incursion, but holding that Jewish settlers had made significant changes to its preparation that were ultimately responsible for making it into a worldwide favorite. Joan Nathan's 2001 Foods of Israel Today, for example, claimed that, while fava and chickpea falafel had both preëxisted the British Mandate period, Mizrahi settlers caused chickpeas to be the only pulse used in falafel.

Gil Marks, who had echoed this narrative in his 2010 Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, later attributed the success of Palestinian foods to settlers' inventiveness: "Jews didn’t invent falafel. They didn’t invent hummus. They didn’t invent pita. But what they did invent was the sandwich. Putting it all together. And somehow that took off and now I have three hummus restaurants near my house on the Upper West Side.”

Israel and elsewhere, 2000s – 2020s: Re-Arabization; or, "Local color"

Ronald Ranta has identified a trend of "re-Arabizing" Palestinian food in Israeli discourse of the late 2000s and later: cooks, authors, and brands acknowledge a food's origin or identity as "Arab," or occasionally even "Palestinian," and consumers assert that Palestinian and Israeli-Palestinian (i.e., Israeli citizens of Palestinian ancestry) preparations of foods are superior to, or more "authentic" than, Jewish-Israeli ones. Israeli and Israeli-Palestinian brands and restaurants market various foods, including falafel, as "אסלי" ("asli"), from the Arabic "أَصْلِيّ" ("ʔaṣliyy"; "original"), or "בלדי" ("baladi"), from the Arabic "بَلَدِيّ" ("baladiyy"; "native" or "my land").

This dedication to multiculturalism may seem like progress, but Ranta cautions that it can also be analyzed as a new strategy in a consistent pattern of marginalization of the indigenous population: "the Arab-Palestinian other is re-colonized and re-imagined only as a resource for tasty food [...] which has been de-politicized[;] whatever is useful and tasty is consumed, adapted and appropriated, while the rest of its culture is marginalized and discarded." This is the "serving bread" and "local color" described by Bondy: "Arabs" are thought of in terms of their usefulness to settlers, and not as equal political participants in the nation. For Ranta, the "re-Arabizing" of Palestinian food thus marks a new era in Israel's "confiden[ce]" in its dominance over the indigenous population.

So this repatriation of Palestinian food is limited insofar as it does not extend to an acknowledgement of Palestinians' political aspirations, or a rejection of the Zionist state. Food, like other indicators and aspects of culture, is a "safe" avenue for engagement with colonized populations even when politics is not.

The acknowledgement of Palestinian identity as an attempt to neutralize political dissent, or perhaps to resolve the contradictions inherent in liberal Zionist identity, can also be seen in scholarship about Israeli food culture. This scholarship tends to focus on narratives about food in the cultural domain, ignoring the material impacts of the settler-colonialist state's control over the production and distribution of food (something that Ranta does as well). Food is said to "cross[] borders" and "transcend[] cultural barriers" without examination of who put the borders there (or where, or why, or how, or when). Disinterest in material realities is cultivated so that anodyne narratives about food as “a bridge” between divides can be pursued.

Raviv, for example, acknowledges that falafel's de-Palestinianization was inspired by anti-Arab sentiment, and that claiming falafel in support of "Jewish nationalism" was a result of "a connection between the people and a common land and history [needing] to be created artificially"; however, after referring euphemistically to the "accelerated" circumstances of Israel's creation, she supports a shared identity for falafel in which it can also be recognized as "Israeli." She concludes that this should not pose a problem for Palestinians, since "falafel was never produced through the labor of a colonized population, nor was Palestinian land appropriated for the purpose of growing chickpeas for its preparation. Thus, falafel is not a tool of oppression."

Palestine and Israel, 1960s – 2020s: Material realities

Yet chickpeas have been grown in Israel for decades, all of them necessarily on appropriated Palestinian land. Experimentation with planting in the arid conditions of the south continues, with the result that today, chickpea is the major pulse crop in the country. An estimated 17,670,000 kilograms of chickpeas were produced in Israel in 2021; at that time, this figure had increased by an average of 3.5% each year since 1966. 73,110 kilograms of that 2021 crop was exported (this even after several years of consecutive decline in chickpea exports following a peak in 2018), representing $945,000 in exports of dried chickpeas alone.

The majority of these chickpeas ($872,000) were exported to the West Bank and Gaza; Palestinians' inability to control their own imports (all of which must pass through Israeli customs, and which are heavily taxed or else completely denied entry), and Israeli settler violence and government expropriation of land, water, and electricity resources (which make agriculture difficult), mean that Palestine functions as a captive market for Israeli exports. Israeli goods are the only ones that enter Palestinian markets freely.

By contrast, Palestinian exports, as well as imports, are subject to taxation by Israel, and only a small minority of imports to Israel come from Palestine ($1.13 million out of $22.4 million of dried chickpeas in 2021).

The 1967 occupation of the West Bank has besides had a demonstrable impact on Palestinians' ability to grow chickpeas for domestic consumption or export in the first place, as data on the changing uses of agricultural land in the area from 1966–2001 allow us to see. Chickpeas, along with wheat, barley, fenugreek, and dura, made up a major part of farmers' crops from 1840 to 1914; but by 2001, the combined area devoted to these field crops was only a third of its 1966 value. The total area given over to chickpeas, lentils and vetch, in particular, shrank from 14,380 hectares in 1966 to 3,950 hectares in 1983.

Part of this decrease in production was due to a shortage of agricultural labor, as Palestinians, newly deprived of land or of the necessary water, capital, and resources to work it—and in defiance of Raviv's assertion that "falafel was never produced through the labor of a colonized population"—sought jobs as day laborers on Israeli fields.

The dearth of water was perhaps especially limiting. Palestinians may not build anything without a permit, which the Israeli military may deny for any, or for no, reason: no Palestinian's request for a permit to dig a well has been approved in the West Bank since 1967. Israel drains aquifiers for its own use and forbids Palestinians to gather rainwater, which the Israeli military claims to own. This lack of water led to land which had previously been used to grow other crops being transitioned into olive tree fields, which do not require as much water or labor to tend.

In Gaza as well, occupation systematically denies Palestinians of food itself, not just narratives about food. The majority of the population in Gaza is food-insecure, as Israel allows only precisely determined (and scant) amounts of food to cross its borders. Gazans rely largely on canned goods, such as chickpeas (often purchased at subsidized rates through food aid programs run by international NGOs), because they do not require scarce water or fuel to prepare—but canned chickpeas cannot be used to prepare a typical deep-fried falafel recipe (the discs would fall apart while frying). There is, besides, a continual shortage of oil (of which only a pre-determined amount of calories are allowed to enter the Strip). Any narrative about Israeli food culture that does not take these and other realities of settler-colonialism into account is less than half complete.

Of course, falafel is far from the only food impacted by this long campaign of starvation, and the strategy is only intensifying: as of December 2023, children are reported to have died by starvation in the besieged Gaza Strip.

Support Palestinian resistance by calling Elbit System’s (Israel’s primary weapons manufacturer) landlord; donating to Palestine Action’s bail fund; buying an e-sim for distribution in Gaza; or donating to help a family leave Gaza.

Equipment:

A meat grinder, or a food processor, or a high-speed or immersion blender, or a mortar and pestle and an enormous store of patience

A pot, for frying

A kitchen thermometer (optional)

Ingredients:

Makes 12 large falafel balls; serves 4 (if eaten on their own).

For the فلافل (falafel):

500g dried chickpeas (1010g once soaked)

1 large onion

4 cloves garlic

1 Tbsp cumin seeds

1 Tbsp coriander seeds

2 tsp dill seeds (عين جرادة; optional)

1 medium green chili pepper (such as a jalapeño), or 1/2 large one (such as a ram's horn / فلفل قرن الغزال)

2 stalks green onion (3 if the stalks are thin) (optional)

Large bunch (50g) parsley, stems on; or half parsley and half cilantro

2 Tbsp sea salt

2 tsp baking soda (optional)

For the حَشوة (filling):

2 large yellow onions, diced

1/4 cup coarsely ground sumac

4 tsp shatta (شطة: red chili paste), optional

Salt, to taste

3 Tbsp olive oil

For the طراطور (tarator):

3 cloves garlic

1/2 tsp table salt

1/4 cup white tahina

Juice of half a lemon (2 Tbsp)

2 Tbsp vegan yoghurt (لبن رائب; optional)

About 1/4 cup water

To make cultured vegan yoghurt, follow my labna recipe with 1 cup, instead of 3/4 cup, of water; skip the straining step.

To fry:

Several cups neutral oil

Untoasted hulled sesame seeds (optional)

Instructions:

1. If using whole spices, lightly toast in a dry skillet over medium heat, then grind with a mortar and pestle or spice mill.

2. Grind chickpeas, onion, garlic, chili, and herbs. Modern Palestinian recipes tend to use powered meat grinders; you could also use a food processor, speed blender, or immersion blender. Some recipes set aside some of the chickpeas, aromatics, and herbs and mince them finely, passing the knife over them several times, then mixing them in with the ground mixture to give the final product some texture. Consult your own preferences.

To mimic the stone-ground texture of traditional falafel, I used a mortar and pestle. I found this to produce a tender, creamy, moist texture on the inside, with the expected crunchy exterior. It took me about two hours to grind a half-batch of this recipe this way, so I don't per se recommend it, but know that it is possible if you don't have any powered tools.

3. Mix in salt, spices, and baking soda and stir thoroughly to combine. Allow to chill in the fridge while you prepare the filling and sauce.

If you do not plan to fry all of the batter right away, only add baking soda to the portion that you will fry immediately. Refrigerate the rest of the batter for up to 2 days, or freeze it for up to 2 months. Add and incorporate baking soda immediately before frying. Frozen batter will need to be thawed before shaping and frying.

For the filling:

1. Heat olive oil in a skillet over medium heat. Fry onion and a pinch of salt for several minutes, until translucent. Remove from heat.

2. Add sumac and stir to combine. Add shatta, if desired, and stir.

For the tarator:

1. Grind garlic and salt in a mortar and pestle (if you don't have one, finely mince and then crush the garlic with the flat of your knife).

2. Add garlic to a bowl along with tahina and whisk. You will notice the mixture growing smoother and thicker as the garlic works as an emulsifier.

3. Gradually add lemon juice and continue whisking until smooth. Add yoghurt, if desired, and whisk again.

4. Add water slowly while whisking until desired consistency is achieved. Taste and adjust salt.

To fry:

1. Heat several inches of oil in a small or medium pot to about 350 °F (175 °C). A piece of batter dropped in the oil should float and immediately form bubbles, but should not sizzle violently. (With a small pot on my gas stove, my heat was at medium-low).

2. Use your hands or a large falafel mold to shape the falafel.

To use a falafel mold: Dip your mold into water. If you choose to cover both sides of the falafel with sesame seeds, first sprinkle sesame seeds into the mold; then apply a flat layer of batter. Add a spoonful of filling into the center, and then cover it with a heaping mound of batter. Using a spoon, scrape from the center to the edge of the mold repeatedly, while rotating the mold, to shape the falafel into a disc with a slightly rounded top. Sprinkle the top with sesame seeds.

To use your hands: wet your hands slightly and take up a small handful of batter. Shape it into a slightly flattened sphere in your palm and form an indentation in the center; fill the indentation with filling. Cover it with more batter, then gently squeeze between both hands to shape. Sprinkle with sesame seeds as desired.

3. Use a slotted spoon or kitchen spider to lower falafel balls into the oil as they are formed. Fry, flipping as necessary, until discs are a uniform brown (keep in mind that they will darken another shade once removed from the oil). Remove onto a wire rack or paper towel.

If the pot you are using is inclined to stick, be sure to scrape the bottom and agitate each falafel disc a couple seconds after dropping it in.

4. Repeat until you run out of batter. Occasionally use a slotted spoon or small sieve to remove any excess sesame seeds from the oil so they do not burn and become acrid.

Serve immediately with sauce, sliced vegetables, and pickles, as desired.

#Palestine#Israel#vegetarian recipes#Palestinian#falafel#chickpeas#sumac#onions#garlic#parsley#cilantro#dill seeds#sesame seeds#tahina#yoghurt#long post /

781 notes

·

View notes

Note

[ Aeternus ]

She says to ( wait ) and unlike everyone else who has asked him such a simple thing, he waits.

He does not turn however. He stays staring forward; sharp suit of autumnal colors and hat decorated like the last rays of the sun with only the sharp pinprick of a wrapped emerald and a few mouse skulls adorning it's brim, cleaned and pressed and no sign of the horrors he's done and seen to get where he is now. If he looks back, he will have ( regrets ).

But he feels her hand gently against his, less like ' I want to show you something, would you be interested ' and more like ' my hands would recognize yours no matter how bloody and calloused they get '. She steps in close, so much smaller than she already was all those years ago, her eyes a lovely but pale reminder of skies that he can only ever remember as ever-burning and full of smoke. She says nothing for a moment, but she doesn't need to.

( oh. it's you. my soul has been waiting for you. where have you been? )

... With little prompting left, he leans down to kiss her.

A kiss like the first flame brought to humanity; disastrous but awe inspiring, a warmth flooding through the body like the dawn and yet right in the palm of their hands. A gift, a curse, and a spite towards the gods all in one. He pulls away after a few moments and whispers against her lips,

"I canno' be 'ere lon'. Bu', I'm glad ya missed me, songbird."

She pauses there, her hand in his. Like that's where it's supposed to be. Looking up at him with those soft blue eyes. Curious and loving all the same. Unchanged by the years. Still seeing more than she lets on. Hands seeing and saying more than most would notice.

It's not an outfit she recognizes. But it's him. And he's there. Even if it's just but for a moment. Here, with her. And she's feeling things she hasn't felt for a long time. She wants to hold on, for as long as she can. Holding this moment close.

There isn't a moment of hesitation, Aliya leaning into the kiss. Into the warmth and familiarity of it. Smiling, even as it ends. Yes, hello again, you're remembered and missed.

"I'll be glad for however long you can give." Whispered back, content and slow. She doesn't want to move away. Wants to be close to him. To have this moment for as long as it lasts. "I'm glad I was remembered."

#ic: Aliya#aliya - books and a psychic#springtwirling#ch: Aeternus#asks#answered#verse: Freedom#//YOU#//MY HEART#//AAAAAA#//stop. stealing. my. kneecaps /j#//My BONES Solaris#//curse you and your fantastic writing#//I love it all

0 notes

Note

loving your falafel research saga and just wanted to ask - something I remember hearing about falafel is that while Israeli culture definitely appropriated it, the concept of serving it in pita bread with salads, tahini etc. is a specifically Israeli twist on the dish. I wonder if you found/know anything about that?

The short answer is: it's not impossible, but I don't think there's any way to tell for sure. The long answer is:

The most prominent claim I've heard of this nature is specifically that Yemeni Jews (who had immigrated to Israel under 'right of return' laws and were Israeli citizens) invented the concept of serving falafel in "pita" bread in the 1930s—perhaps after they (in addition to Jews from Morocco or Syria) had brought falafel over and introduced it to Palestinians in the first place.

"Mizrahim brought falafel to Palestine"

This latter claim, which is purely nonsense (again... no such thing as Moroccan falafel!)—and which Joel Denker (linked above) repeats with no source or evidence—was able to arise because it was often Mizrahim who introduced Israelis to Palestinian food. Mizrahi falafel sellers in the early 20th century might run licensed falafel stands, or carry tins full of hot falafel on their backs and go from door to door selling them (see Shaul Stampfer on a Yemeni man doing this, "Bagel and Falafel: Two Iconic Jewish Foods and One Modern Jewish Identity," in Jews and their Foodways, p. 183; this Arabic source mentions a 1985 Arabic novel in which a falafel seller uses such a tin; Yael Raviv writes that "Running falafel stands had been popular with Yemenite immigrants to Palestine as early as the 1920s and ’30s," "Falafel: A National Icon," Gastronomica 3.3 (2003), p. 22).

On Mizrahi preparation of Palestinian food, Dafna Hirsch writes:

As Sami Zubaida notes, Middle Eastern foodways, while far from homogeneous, are nevertheless describable in a vocabulary and set of idioms that are “often comprehensible, if not familiar, to the socially diverse parties” [...]. Thus, for the Jews who arrived in Palestine from the Middle East, Palestinian Arab foods and foodways were “comprehensible, if not familiar,” even if some of the dishes were previously unknown to most of them. [...] They found nothing extraordinary or exotic in the consumption, preparation, and selling of foods from the Palestinian Arab kitchen. Therefore, it was often Mizrahi Jews who mediated local foods to Ashkenazi consumers, as street food vendors and restaurant owners. ("Urban Food Venues as Contact Zones between Arabs and Jews during the British Mandate Period," in Making Levantine Cuisine: Modern Foodways of the Eastern Mediterranean, p. 101).

Raviv concurs and furnishes a possible mechanism for this borrowing:

Other Mizrahi Jewish vendors sold falafel, which by the late 1930s had become quite prevalent and popular on the streets of Tel Aviv. [...] Tel Aviv had eight licensed Mizrahi falafel vendors by 1941 and others who sold falafel without a license. [FN: The Tel Aviv municipality granted vending license to people who could not make their living in any other way as a form of welfare.] Many of the vendors were of Yemenite origins, although falafel was unknown in Yemen. [FN: Many of the immigrants from Yemen arrived in Palestine via Egypt, so it is possible that they learned to prepare it there and then adjusted the recipe to the Palestinian version, which was made from chickpeas and not from fava beans (ṭaʿmiya). Shmuel Yefet, an Israeli falafel maker, tells about his father, Yosef Ben Aharon Yefet, who arrived in Palestine from Aden [Yemen] in the early 1920s and then traveled to Port Said in 1939. There he became acquainted with ṭaʿmiya, learned to prepare it, and then went back to Palestine and opened a falafel shop in Tel Aviv [youtube video].]*

But why claim that Yemeni Jews invented falafel (or at least that they had introduced it from Yemen), even though its adoption from Palestinian Arabs in the early days of the second Aliya, aka the 1920s (before Mizrahim had begun to immigrate in larger numbers; see Raviv, p. 20) was within living memory at this point (i.e. the 1950s)? Raviv notes that an increasing (I mean, actually she says new, which... lol) negative attitude towards Arabs in the wake of the Nakba (I mean... she says "War of Independence") created a new sense of urgency around de-Arabizing "Israeli" culture (p. 22). Its association with Mizrahi sellers allowed falafel to "be linked to Jewish immigrants who had come from the Middle East and Africa" and thus to "shed its Arab association in favor of an overarching Israeli identification" (p. 21).

Stampfer again:

On the one hand (with regard to immigrants from Eastern Europe), [falafel] underscored the break between immediate past East European Jewish foods and the new “Oriental” world of Eretz Israel.** At the same time, this food could be seen as a link with an (idealized) past. Among the Jewish public in Eretz Israel, Yemenite falafel was regarded as the most original and tastiest version. This is a bit odd, as falafel—whether in or out of a pita—was not a traditional Yemenite food, neither among Muslims nor among Jews. To understand the ascription of falafel to Yemenite Jews, it is necessary to consider their image. Yemenite Jews were widely regarded in the mid-20th century as the most faithful transmitters of a form of Jewish life that was closest to the biblical world—and if not the biblical world, at least the world of the Second Temple, which marked the last period of autonomous Jewish life in Eretz Israel. In this sense, eating “Yemenite” could be regarded as an act of bodily identification with the Zionist claim to the land of Israel. (p. 189)

So, when it's undeniable that a food is "Arab" or "Oriental" in origin, Zionists will often attribute it to Yemen, Syria, Morocco, Turkey, &c.—and especially to Jewish communities within these regions—because it cannot be permitted that Palestinians have a specific culture that differentiates them in any way from other "Arabs." A culinary culture based in the foodstuffs cultivated from this particular area of land would mean a tie and a claim to the land, which Zionist logic cannot allow Palestinians to possess. This is why you'll hear Zionists correct people who say "Palestinians" to say "Arab" instead, or suggest that Palestinians should just scooch over into other "Arab" countries because it would make no difference to them. Raviv's conclusion that the attribution of falafel to Yemeni immigrants is an effort to detach it from its "Arab" origins isn't quite right—it is an attempt to detach it, and thus Palestinians themselves, from Palestinian roots.

"Yemeni Jews first put falafel in 'pita'"

As for this claim, it's often attributed to Gil Marks: "Jews didn’t invent falafel. They didn’t invent hummus. They didn’t invent pita. But what they did invent was the sandwich. Putting it all together.” (Hilariously, the author of the interview follows this up with "With each story, I wanted to ask, but how do you know that?")

Another author (signed "Philologos") speculates (after, by the way, falsely claiming that "falafel" is the plural of the Arabic "filfil" "pepper," and that falafel is always brown, not green, inside?!):

Yet while falafel balls are undoubtedly Arab in origin, too, it may well be that the idea of serving them as a street-corner food in pita bread, to which all kinds of extras can be added, ranging from sour pickles to whole salads, initially was a product of Jewish entrepreneurship.

Shaul Stampfer cites both of these articles as further reading on the "novelty of the combination of pita, falafel balls, and salad" (FN 76, p. 198)—but neither of them cites any evidence! They're both just some guy saying something!

Marks had, however, elaborated a little bit in his 2010 Encyclopedia of Jewish Food:

Falafel was enjoyed in salads as part of a mezze (appetizer assortment) or as a snack by itself. An early Middle Eastern fast food, falafel was commonly sold wrapped in paper, but not served in the familiar pita sandwich until Yemenites in Israel introduced the concept. [...] Yemenite immigrants in Israel, who had made a chickpea version in Yemen, took up falafel making as a business and transformed this ancient treat into the Israeli iconic national food. Most importantly, Israelis wanted a portable fast food and began eating the falafel tucked into a pita topped with the ubiquitous Israeli salad (cucumber-and-tomato salad).

He references one of the pieces that Lillian Cornfeld (columnist for the English-language, Jerusalem-based newspaper Palestine Post) wrote about "filafel":

An article from October 19, 1939 concluded with a description of the common preparation style of the most popular street food, 'There is first half a pita (Arab loaf), slit open and filled with five filafels, a few fried chips and sometimes even a little salad,' the first written record of serving falafel in pita. [Marks doesn't tell you the title or page—it's "Seaside Temptations: Juveniles' Fare at Tel Aviv," p. 4.]

You will first of all notice that Marks gives us the "falafel from Yemen" story. I also notice that he calls Salat al-bundura "Israeli salad" (in its entry he does not claim that European Jewish immigrants invented it, but neither does he attribute it to Palestinian influence: the dish was originally "Turkish coban salatsi"). His encyclopedia also elsewhere contains Zionist claims such as "wild za'atar was declared a protected plant in Israel" "[d]ue to overexploitation" because of how much of the plant "Arab families consume[d]," and that Israeli cultivation of the crop yielded "superior" plants (entry for "Za'atar")—a narrative of "Arab" mismanagement, and Israeli improvement, of land used to justify settler-colonialism. He writes that Palestinians who accuse "the Jews" of theft in claiming falafel are "creat[ing] a controversy" and that "food and culture cannot be stolen," with no reflection on the context of settler-colonialism and literal, physical theft that lies behind said "controversy." This isn't relevant except that it makes me sceptical of Marks's motivations in general.

More pertinent is the fact that this quote doesn't actually suggest that this falafel vendor was Yemeni (or otherwise) Jewish, nor does it suggest that he was the first one to prepare falafel in pitas with "fried chips," "sometimes even a little salad," and "Tehina, a local mayonnaise made with sesame oil" (Cornfeld, p. 4). I think it likely that this food had been sold for a while before it was described in published writing. The idea that this preparation is "Israeli" in origin must be false, since this was before the state of "Israel" existed—that it was first created by Yemeni Jewish falafel vendors is possible, but again, I've never seen any direct evidence for it, or anyone giving a clear reason for why they believe it to be the case, and the political reasons that people have for believing this narrative make me wary of it. There were Palestinian Arab falafel vendors at this time as well.

"Chickpea falafel is a Jewish invention"

There is also a claim that falafel originated in Egypt, where it was made with fava beans; spread to the Levant, including Palestine, where it was made with a combination of fava beans and chickpeas; but that Jewish immigration to Israel caused the origin of the chickpea-only falafal currently eaten in Palestine, because a lot of Jewish people have G6PD deficiencies or favism (inherited enzymatic deficiencies making fava beans anywhere from unpleasant to dangerous to eat)—or that Jewish populations in Yemen had already been making chickpea-only falafel, and this was the falafel which they brought with them to Palestine.

As far as I can tell, this claim comes from Joan Nathan's 2001 The Foods of Israel:

Zadok explained that at the time of the establishment of the state, falafel—the name of which probably comes from the word pilpel (pepper)—was made in two ways: either as it is in Egypt today, from crushed, soaked fava beans or fava beans combined with chickpeas, spices, and bulgur; or, as Yemenite Jews and the Arabs of Jerusalem did, from chickpeas alone. But favism, an inherited enzymatic deficiency occurring among some Jews—mainly those of Kurdish and Iraqi ancestry, many of whom came to Israel during the mid 1900s—proved potentially lethal, so all falafel makers in Israel ultimately stopped using fava beans, and chickpea falafel became an Israeli dish.

Gil Marks's 2010 Encyclopedia of Jewish Food echoes (but does not cite):

Middle Eastern Jews have been eating falafel for centuries, the pareve fritter being ideal in a kosher diet. However, many Jews inherited G6PD deficiency or its more severe form, favism; these hereditary enzymatic deficiencies are triggered by items like fava beans and can prove fatal. Accordingly, Middle Eastern Jews overwhelmingly favored chickpeas solo in their falafel. (Entry for "Falafel")

The "centuries" thing is consistent with the fact that Marks believes falafel to be of Medieval origin, a claim which most scholars I've read on the subject don't believe (no documentary evidence, + oil was expensive so it seems unlikely that people were deep frying anything). And, again, this claim is speculation with no documentary evidence to support it.

As for the specific modern toppings including the Yemeni hot sauce سَحاوِق / סְחוּג (saHawiq / "zhug"), Baghdadi mango pickle عنبة / עמבה ('anba), and Moroccan هريسة / חריסה ("harissa"), it seems likely that these were introduced by Mizrahim given their place of origin.

*You might be interested to know that, despite their Jewishness mediating this borrowing, Mizrahim were during the Mandate years largely ethnically segregated from Eastern European Zionists, who were pushing to create a "new" European-Israeli Judaism separate from what they viewed as the indolence and ignorance of "Oriental" Jewishness (Hirsch p. 101).

This was evidenced in part by Europeans' attitudes towards the "Oriental" diet. Ari Ariel, summarizing Yael Raviv's Falafel Nation, writes:

Although all immigrants were thought to require culinary education as an aspect of their absorption into the new national culture, Middle Eastern Jews, who began to immigrate in increasing numbers after 1948, provoked greater anxiety on the part of the state than did their Ashkenazi co-religionists. Israeli politicians and ideologues spoke of the dangers of Levantization and stereotyped Jews from the Middle East and North Africa as primitive, lazy, and ignorant. In keeping with this Orientalism, the state pressured Middle Easterners to change their foodways and organized cooking demonstrations in transit camps and new housing developments. (Book review, Israel Studies Review 31.2 (2016), p. 169.)

See also Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, "Longing for the Aromas of Baghdad: Food, Emigration, and Transformation in the Lives of Iraqi Jews in Israel in the 1950s," in Jews and their Foodways:

[...] [T]he Israeli establishment was set on “educating” the new immigrants not only in matters of health and hygiene, [77] but also in the realm of nutrition. A concerted propaganda effort was launched by well-baby clinics, kindergartens, schools, health clinics, and various organizations such as the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO) and the Organization of Working Mothers in order to promote the consumption of milk and dairy products, in particular. [78] (These had a marginal place in Iraqi cuisine, consumed mainly by children.) Arab and North African cuisines were criticized for being not sufficiently nutritious, whereas the Israeli diet was touted as ideal, as it was western and modern. […] [T]he assault on traditional Middle Eastern cuisines reflected cultural arrogance yet another attempt to transform immigrants into “new Jews” in accordance with the Zionist ethos.

Thus, European table manners were presented as the norm. Eating with the hands was equated with primitive behavior, and use of a fork and knife became the hallmark of modernity and progress. (pp. 100-101)

[77. On health matters, see Davidovich and Shvarts, “Health and Hegemony,” 150–179; Sahlav Stoller-Liss, “ ‘Mothers Birth the Nation’: The Social Construction of Zionist Motherhood in Wartime in Israeli Parents’ Manuals,” Nashim 6 (Fall 2003), 104–118.]

[78. On propaganda for drinking milk and eating dairy products, see Mor Dvorkin, “Mif’alei hahazanah haḥinukhit bishnot ha’aliyah hagedolah: mekorot umeafyenim” (seminar paper, Ben-Gurion University, 2010).]

**On the desire to shed "old, European" "Jewish" identity and take on a "new, Oriental" "Hebrew" one, and the contradictory impulses to use Palestinian Arabs as models in this endeavour and to claim that they needed to be "corrected," see:

Itamar Even-Zohar, "The Emergence of a Native Hebrew Culture in Palestine, 1882—1948"

Dafna Hirsch, "We Are Here to Bring the West, Not Only to Ourselves": Zionist Occidentalism and the Discourse of Hygiene in Mandate Palestine"

Ofra Tene, "'The New Immigrant Must Not Only Learn, He Must Also Forget': The Making of Eretz Israeli Ashkenazi Cuisine."

#sorry for this but you should've known better than to ask me about falafel at this stage in my life#falafel research saga

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

GWitch: Finale thoughts

Pardon for the lateness on this, got busy after the episode aired and then proceeded to write a fic using my achemy brainworms lmao. But here it is, the end of a terrific journey!

The permet stress really took its toll upon Suletta after her bout with Eri but that won't stop our girl from trying to save her family. So rough to see though.

Gotta say, besides Nika and Chuchu, Aliya is easily my fav Earth House kid. She's into divination, takes care of animals, and is just so chill

Surprise Surprise SAL are being cheeky assholes. They don't care what Delling/Benerit has to say since this is just a grasp for power on their behalf. They have all the cards atm with that WMD

This was nice I guess, but I really dislike him so I just rolled my eyes lmao. I guess the one Lauda stan is happy he got screentime.

For Mio to keep entreating Prospera is admirable on her part. She knows it might fall on deaf ears but she has to try for the sake of her future wife and hellish mother-in-law. It was so good how her faith in Suletta never wavers. She knows Suletta is coming and isn't surprised once she shows with Aerial

And Suletta demonstating her growth by ignoring Prospera's command? Top-tier fr fr. Loved that entire exchange and call back to ep12

I don't mind 4 but it is painfully obvious he was slotted into this role because of the truncated re-write. 'I guess I'm like her' No sir, you were explicitly not in S1 LMAO! But I guess they needed a newtype to overpower Eri even though it doesn't narratively make sense for 4 to be one. Ah well, in another world where Okouchi got the seasons he wanted ;-;. It was a nice send off nonetheless

Rainbow party permet is so cool, pride Gundam!! I wasn't too keen on Calibarn's design before, tho I love the broom, the rainbow really sells it for me. And that coven of gundams?? So cool. Schwarzette usage here, abysmal pilot, and wealth of unused symbolism stings a bit. They so clearly had an arc planned but had to cut it :/ I would love to see the initial draft before cuts were made

MIOMIO DISSOLVES BENERIT. Hell yeah. Had a feeling she would choose to go this route. Also, the stone cold way she stares down the barrel of a gun... Ma'am, my heart <3 The best peace princess ever

This hit me in the feels. Suletta forgiving her mother, Eri begging for all of them to be a family, and Prospera seeing the ghosts of Vanadis smiling at her lovingly. It was everything to me.

The soundless fake-out as Mio believes Suletta is dead was cruel and brilliant. The horror in her eyes that morphs into weepy happiness when Suletta awakens will stay with me for a long time. They even did the little gundam helmet bop again!

Shaddiq taking the fall for everything was good of him, but it feels a bit too neat haha (They had to wrap up loose threads hastily and it shows) He really is an interesting character that, in a longer run, could have been amazing

Surprise! Sulemio got happily married during the timeskip and now Mio has to suffer a keychain's negging. Super funny outcome but I hope Eri can move between devices or else that's a bit hellish

Mio stealing Shaddiq's highly trained girlsquad is amazing. Ain't no one getting to the president of GUND-ARM without a fight. This also opens up the possibility for more Sabanika, so excellent decision all around

THE RINGS!!!! Ahh any nitpicks are nothing compared to sheer happiness I feel when seeing them. They fought and suffered so hard for this ending and it was all worth it! Eri and Prospera sharing in their joy is the cherry on top~

This image is my fav. Suletta is such a special protagonist and her relationship with Miorine broke ground in a legacy franchise no less. They are in love! They married! And no one can take that from them. Thank you GWitch, I love you lots. This ride has been unforgettable from the beginning <3

#and they all lived happily ever after#g witch#g witch spoilers#suletta mercury#miorine rembran#sulemio#gundam witch from mercury#prospera mercury#ericht samaya

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

if you've been reading my desperados fic, here's a masterlist (the last three are public domain characters/my OCs)

#desperados#aliya writes#hector like laughing: I'm in danger#I might doodles the three OCs that're in the bottom

1 note

·

View note

Note

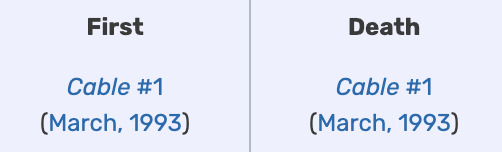

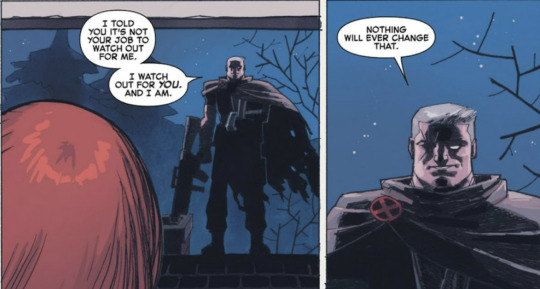

what happened to Cable’s wife and daughter?

well, it shouldn't be any surprise that 616 nathan is a perpetual bachelor actually and does not in fact have a wife (unless we are counting one wade w wilson, nathan's long-term long-distance low-commitment casual girlfriend)

he's had girlfriends over the years but i don't think nathan's the marrying type, save for, of course, the time wade and nate were biologically linked. sounds pretty close to married.

nathan never been married but definitely divorced summers.

he actually was married in some alternative future to (reads notes) ...aliya... who survived for a grand total of one issue.

i actually have this issue. but i didn't even remember it.

f in the chat for nathan's wife, aliya dayspring (1993–1993)

and they had a son. who is also dead. f in the chat for tyler.

(i can't believe nathan's son is named tyler. such a fucking white boy name. wade would bully him relentlessly if he found out nate had a son called tyler. fucking tyler. it's a shame he's dead. eleanor would bully him relentlessly too. fucking tyler. i think i should write tyler into 9319 and he has to babysit eleanor at some point and eleanor is an unrelenting terror and definitely makes him cry.)

as for his daughter, she's around. she's adopted. i love her.

hope summers, my beloved. she does exist in 9319. in fact, i have a whole post about fatherhood scripted between nate and wade that will come around eventually. eventually.

not me clutching messy fathers with daddy issues wade wilson and nathan summers so very close to my chest and waiting for them to bond over it. canon never gave me this. i need wade wilson to ask nathan for dadhood advice. i need it like i need oxygen.

("you were always like a father to me." wade wilson says to nathan summers, under the moonlight. nathan summers says "that is so fucking weird for you to say." a beat of silence across the cosmos.)

#sci speaks#this answer got out of hand.#anyway we can get into the daddy issues at a later date. wade will probably speak at great length about it in therapy.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I finished secret project 3 about seven hours ago, and I need to vent my love for this abomination of a wonder that is this book before I squeal loudly enough to wake the neighbors!

Brandon Sanderson, I direct this at you with all of my appreciation, nearly hyperventilating while grinning and cackling and tearing up from happiness:

What the (highly) absolute fuck was that?!

Seriously how?! Why!? I love this book so so so so much! But WHY?!?!

He made a world that was messed up weirder than Threnody, the weirdness disaster god death planet itself?!

He made a planet that was so Invested that it heated the ground to death-inducing levels, and that was before the activation of the undead world-destroying nightmare-supported time-lord-prison-utilizing spirit-trapping art-blaspheming neon machine.

Seriously, this novel features an undead world-destroying nightmare-supported time-lord-prison-utilizing spirit-trapping art-blaspheming neon machine!

Yet it’s the world I find the most beautiful and fascinating in the entirety of the Cosmere? I’ll be chewing on best-planet Komashi for the foreseeable future, so that’s great! Especially since we’re probably never going to visit this planet again!

And somehow secret project 3 is also a heartwarming tear inducing story of purpose and passion and connection. A story with characters I’ll be spinning around in my head for the next several months, if not longer. With a Sanderlanche that emotionally wrecked me.

By the way, let’s talk about the Sanderlanche! This Sanderlanche read to me like a love child of the Elantris and Warbreaker Sanderlanches, only with with Brandon’s current writing skill and Cosmere worldbuilding. Both of which had a strong willingness to let main characters die! I mean come on, there’s a hidden second epilogue not in the table of contents, solely to fuck with us into thinking this story would end with the major character death!

But this book not only gets a happy ending, but also has the fewest named character deaths of any full-length Cosmere novel to date?! (not counting those that were already dead from the start I mean, the only death is Usasha I think?).

To make my composure break even further, I found the artwork of the book itself be absolutely gorgeous! Aliya Chen’s showcase for this novel is beautiful while being perfectly suited for the vibe of the novel. The emotion and chemistry on display in the art? Fantastic. The colors and textures are so amazing! The way the artistry of the stacked rocks are captured on the page?! While also conveying just how overwhelming the nightmares would feel?! And the endpapers, those endpapers!

And the cosmere connections! The Hoid powers lore had me squealing! The discussion of Komashi’s Investitures and Yumi’s abilities in relation to other Invested beings! Design in general, Design best spren! And that’s only part of it!

Brando Sando, what made you decide to go this hard on this standalone novel?! I know you said you’re taking the gloves off, but this is ridiculous!

I don’t think this is going to be a novel that all Brandon Sanderson fans are going to love to this extent, since taste and individual standards are a thing that exists and that’s valid! Still, wow!

I can’t keep the grin off my face and tears of happiness from my eyes and I’m so so so so glad this book exists now!

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

how would each RO support MC at a sports game? Like full on face paint, MC's jersey, and glittery big sign or comes normally but shouts SO LOUD, or just shows up like 🧍with a "ya did good kid" at the end for MC?

aliya: she would definitely show up in like sorority girl chic like mc's cropped jersey and cute matching face paint except she likes to yell really mean things at the other team and the ref when she gets upset

baz: he's not really a sports guy so he'd probably just cheer when everyone else cheers but he'd def listen to mc ramble about whatever pissed them off during the game in support