#The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes (1937 film)

Text

Top 10 Disney Movies That Were Never Made

Originally published January 13th, 2013

The Brave Little Toaster is being remade and will include more modern appliances like an iPhone. There was a huge outcry at this because fuck man, The Brave Little Toaster is just awesome like okay? But that movie was almost never made. John Lasseter would have made his directorial debut with it, but Disney fired him when he suggested using 2-D characters with 3-D backgrounds and the project was shelved. But of course, it exists now. But doesn’t it make you wonder what movies stayed shelved? Here are my Top 10.

10. Bambi’s Children (1943). There were a lot of Disney sequels that were never made, but this was by far the worst sequel idea I came across. Let’s watch some deer grow up—again!

9. The Fool’s Errand (2002). A story about a court jester that has to save his kingdom. That would have been awesome.

8. The Prince and the Pig (2003). A boy and his pig try to steal the moon. THAT WOULD HAVE BEEN AWESOME.

7. Army Ants (1988). A pacifist ant struggles living in a militant colony. It’s funny because this idea was shelved twenty years before the whole “Antz and A Bug’s Life” controversy.

6. Wild Life (2005). Animals from the zoo trying to live in the gritty New York city. The idea was canned for not being “Disney.” It was later remade into the Disney movie “The Wild.”

5. Penguin Island (1938). A half-blind Christian Monk crash lands on an island of penguins and, mistaking them for people, baptizes them. That couldn’t have gone well, but I would have watched the shit out of it.

4. The Hound of Florence Inspector Bones (1941). Essentially Sherlock Holmes with dogs. What’s unique about it is that it would have been in the style of Tex Avery cartoons. This was especially funny because Warner Bros. and Disney were in fierce competition in the early 1900s when they were both making aniamted shorts. Warner Bros. was pop culturey and Disney had heart. It would have been something to see Disney step into the Warner Bros. territory.

3. The Tales of Hans Christian Anderson (1943). This was actually going to be a story about the author’s life, with his life filmed in live-action and some of his tales included as animated segments. Some of the tales that would have been included were The Little Mermaid, The Emperor’s New Clothes, and The Snow Queen. All of these tales were made into Disney movies decades later (The Little Mermaid, The Emperor’s New Groove, and the upcoming Frozen.) It would have been strange to see how Disney would have done them in the forties.

2. Disney’s Dwarfs (2007). This was basically supposed to be a franchise following the drawfs from Snow White. Here’s the kick: It was supposed to be in the style of Lord of the Rings. Essentially, Disney was going to do a gritty reboot of its very first movie. But believe it or not, there’s a better pick for number one…

1. The Wizard of Oz (1937). Disney planned on making this film right after Snow White, but the rights were lost out to Samuel Goldwyn, who later sold them to MGM. MGM, of course, wound up making The Wizard of Oz that we all know, debatably the most iconic movie of all time. Imagine if Disney had gotten the rights. Imagine if he was the one to make The Wizard of Oz.

0 notes

Photo

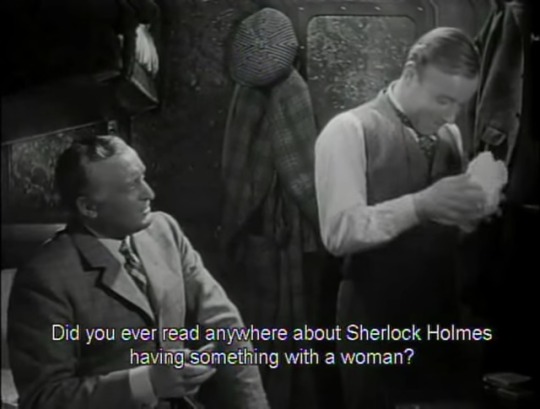

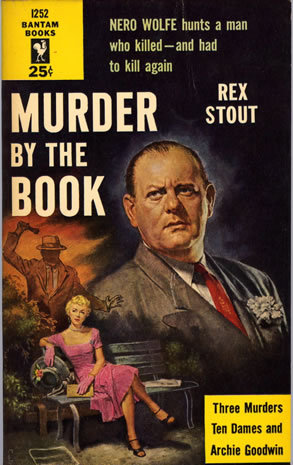

Der Mann, der Sherlock Holmes war (1937) — tr. The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes

#Der Mann der Sherlock Holmes war (1937 film)#Karl Hartl#note this is at least partly a propaganda film#oh the irony#Hans Albers#Heinz Rühmann#The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes (1937 film)#Two Merry Adventurers (1937 film)

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

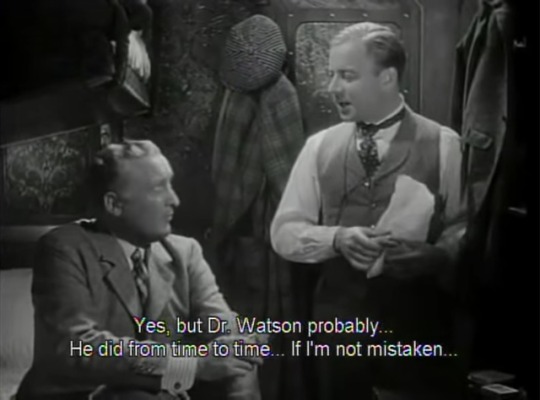

Portrayals of English Queens Regnant on Film and TV

Empress Matilda:

Becket, 1964

The Devil’s Crown, 1978

The Pillars of the Earth, 2010

Jane Grey and Mary I:

Tudor Rose, 1936

Lady Jane, 1986

Jane Grey and Elizabeth I:

The Prince and the Pauper, 1937

The Prince and the Pauper, 1976

Crossed Swords, 1977

The Prince and the Pauper, 1996

The Prince and the Pauper, 2000

Jane Grey, Mary I and Elizabeth I:

The Prince and the Pauper, 1962

Becoming Elizabeth, 2022

Mary I and Elizabeth I:

The Pearls of the Crown, 1937

Anne of the Thousand Days, 1969

Elizabeth R, 1971

Elizabeth, 1998

Elizabeth, 2000

Elizabeth I: Red Rose of the House of Tudor, 2000

The Virgin Queen, 2005

The Tudors, 2008

Wolf Hall, 2015

Elizabeth I and Her Enemies, 2017

Anne Boleyn, 2021

Just Mary I:

Marie Tudor, 1912

Anna Boleyn, 1920

Marie Tudor, 1966

The Six Wives of Henry VIII, 1971

Henry VIII and his Six Wives, 1972

Love and the Queen, 1977

Henry VIII, 2003

The Twisted Tale of Bloody Mary, 2008

Carlos, Rey Emperador, 2015

The Spanish Princess, 2019

Just Elizabeth I:

The Lovers of Queen Elizabeth, 1912

The Virgin Queen, 1923

Drake of England, 1935

Mary of Scotland, 1936

Fire Over England, 1937

The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, 1939

The Heart of a Queen, 1940

Young Bess, 1953

Elizabeth the Queen, 1968

Jubilee, 1978

Will Shakespeare, 1978

Drake’s Venture, 1980

Blackadder II, 1986

Orlando, 1992

Shakespeare in Love, 1998

Gunpowder, Treason, and Plot, 2004

Elizabeth I, 2005

Anonymous, 2011

Reign, 2015

Bill, 2015

Upstart Crow, 2017

Mary Queen of Scots, 2018

A Discovery of Witches, 2018

The Boleyns: A Scandalous Family, 2021

Blood, Sex, and Royalty, 2022

Mary II and Anne:

The First Churchills, 1969

Just Mary II:

England, My England, 1995

The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse, 2005

Versailles, 2015

Just Anne:

The Man Who Laughs, 1928

The Glass of Water, 1960

The Favourite, 2018

Victoria:

Sixty Years a Queen, 1913

Disraeli, 1916

The Yankee Clipper, 1927

The War of the Waltzes, 1933

Victoria in Dover, 1936

David Livingstone, 1936

Victoria the Great, 1937

The Little Princess, 1939

The Prime Minister, 1941

Time Flies, 1944

Annie Get Your Gun, 1950

The Mudlark, 1950

Victoria Regina, 1951

Happy and Glorious, 1952

The Story of Gilbert and Sullivan, 1953

Melba, 1953

Victoria in Dover, 1954

Seven Seas to Calais, 1961

Victoria Regina, 1961

Victoria Regina, 1964

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, 1970

Fall of Eagles, 1974

Edward the Seventh, 1975

Disraeli, 1978

Lillie, 1978

Around the World in 80 Days, 1989

Mrs. Brown, 1997

Victoria and Albert, 2001

Looking for Victoria, 2003

Around the World in 80 Days, 2004

The Young Victoria, 2009

Victoria, 2016

The Greatest Showman, 2017

The Black Prince, 2017

Holmes & Watson, 2018

Elizabeth II:

Charles & Diana: A Royal Love Story, 1982

The Royal Romance of Charles and Diana, 1982

A Question of Attribution, 1992

Fergie & Andrew: Behind the Palace Doors, 1992

The Women of Windsor, 1992

Charles and Diana: Unhappily Ever After, 1992

Diana: Her True Story, 1993

Prince William, 2002

Bertie and Elizabeth, 2002

The Queen, 2006

The Queen, 2009

The King’s Speech, 2010

William and Catherine: A Royal Romance, 2011

Walking the Dogs, 2012

A Royal Night Out, 2015

The BFG, 2016

The Crown, 2016

Inside Windsor Castle, 2017

Harry & Meghan: A Royal Romance, 2018

The Queen and I, 2018

Pennyworth, 2019

Spencer, 2021

#I skipped ones where an actress played the same queen twice#And when multiple actresses play different ages of the same queen in a show#And most of the spoofs and one-off appearances in TV shows#Can we all appreciate the progression from Charles and Diana a Royal Love Story to Charles and Diana Unhappily Ever After#like how often do Lifetime movies get sequels#also maybe after Charles and Diana retire the 'Royal Romance' thing#Queens on screens#Plantagenets#Tudors#Stuarts#Victorians#Windsors

136 notes

·

View notes

Photo

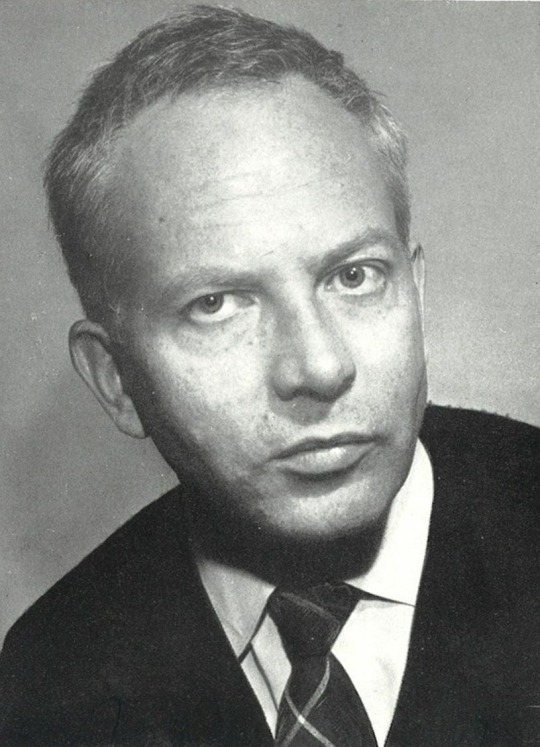

Paul Edwin Roth - a versatile character actor and Germany’s Dr. Watson

Paul Edwin Roth was born into a family of doctors in Hamburg on October 22, 1918 and grew up in the Hanseatic city. After graduating from high school at the "Johanneum" in Hamburg, he actually had other career plans and wanted to become a doctor like his father. Only at the urging of his mother did he attend the drama school of the "Deutsches Schauspielhaus" from 1937 until 1939. Roth made his stage debut in 1939 at the "Stadttheater Heilbronn" as Gustave de Grignon in the comedy "What the Ladies Like" by Eugène Scribes, followed by engagements in Karlsruhe, Heidelberg, Darmstadt and Wiesbaden.

At the end of the Second World War he was severely wounded and probarbly traumatised by his horrible experiences he was released as a prisoner of war from the Russians.

In 1948 Roth played the leading part of Beckman in the stage play "Draußen vor der Tür" ("The Man Outside") by Wolfgang Borchert at the “Hebbel Theater” in Berlin. It was a huge success and Roth was regarded as one of Germanys most important character actors since then.

His other outstanding stage roles in the late 1940s included his interpretation of Moritz Stiefel in the drama "Frühlings Erwachen" ("Spring Awakening") by Frank Wedekind as well as the title role in Friedrich Schiller's play "Don Carlos".

Paul Edwin Roth gave his film debut in 1947 in “Und über uns der Himmel” (“And above as the Sky”) in which he played the former soldier Werner Richter, who lost his eyesight during the war but regaines it later. In 1949 he played in “Unser täglich Brot” (“Our Daily Bread”) the young blackmarketeer Harry Webers who commits suicide in the end. In his film carreer which spanned more than forty years he mostly played distinctive supporting roles.

Paul Edwin Roth's main field of activity had become television since the late 1950s. He made numerous television movies and appeared in many telesvision series. His role as lawyer Patterson in the second season of the television series “Gestatten mein Name ist Cox” (“May I introduce myself - my name is Cox”) (1965) was a big success. It was probably his excellent teamwork with the leading actor Günter Pfitzmann (Roth was some kind of his sidekick) that resulted in his most famous role two years later.

In 1967/68 the first West German TV channel ARD broadcast the only German television series about Sherlock Holmes. The series consists of six episodes originally written by BBC authors based on stories by Arthur Conan Doyle: “Das Gefleckte Band” (“The Speckled Band”), “Sechsmal Napoleon” (“The Six Napoleons”), “ Die Liga der Rothaarigen” (“The Red-Headed League”), “Die Bruce-Partington-Pläne” (“The Bruce-Partington Plans”), “Das Beryll-Diadem “ (“The Beryl Coronet”) and “Das Haus bei den Blutbuchen “ (“The Adventure of the Copper Beeches”) Strangely the credits don’t mention Sherlock Holmes but only Arthur Conan Doyle.

Erich Schellow (1915 - 1995) played the master dectective while Paul Edwin Roth portrayed Dr. John H. Watson. They had a great chemistry (Schellow called his fellow actor Roth - whose two first names Paul and Edwin were drawn together as “Pled” as a nickname - “a clever guy”) and played the relationship between Holmes and Watson as warm but also as very ironic. The fact that the two of them are using the informal “you” (“Du” in German instead of “Sie”) particularly illustrates their loving relationship.

Erich Schellow plays Sherlock Holmes in an aristocratic manner with great dignity and much esprit. The actor wanted to add a touch of depravity to his portrayal (including the use of cocaine) but director Paul May disapproved of it and insisted on an irreproachable Sherlock Holmes.

Paul Edwin Roth (the mustache is false by the way) plays Dr. Watson not as a buffon like Nigel Bruce did but nevertheless he often provides funny moments. Watson’s constant use of his umbrella as a vessel for alcoholic beverages is the running gag of the series. Altough he is a physician he does not appose at the least against intensive use of tobacco and alcohol. He is a very clever man who is proud of remembering every single name and address that is ever given to him. He is also a brave man who doesn’t hesitate to use his army revolver and in “Das Beryll Diadem” he even knocks down the criminal with a stick. Even if he doesn't know what’s going on he remains cool and makes some witty remarks. The dry sense of humour is an outstanding characteristic of the series.

Inexplicably, the series was not a great success. It was only repeated once in 1991. Luckily this gem was released on DVD in 2012 and re-released in 2021.

In addition to his extensive work for film and television, Paul Edwin Roth was also a renowned voice actor. Inter alia he regularly dubbed Montgomery Clift and Michel Bouquet but also Dirk Bogarde in "Accident" and Alan Bates in "Zorba the Greek" and Jason Robards in "By Love Possessed".

Paul Edwin Roth succumbed to cancer on October 27, 1985 in his home town Hamburg - a few days after his 67th birthday.

youtube

youtube

#paul edwin roth#erich schellow#Sherlock Holmes#dr watson#Sherlock Holmes in Germany#biography#forever in my heart

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

films on youtube: part i

Updated on September 29th 2021.

Below is a selection of films available on YouTube. As I try to update this list as regularly as possible (for this is a lenghthy process), please refer to the original post for the newest version.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Apparently, Tumblr restricts the number of links you can have all on one post. Therefore, this list is divided into two parts. You can access part two by clicking on the link below:

PART II HERE.

For a visual reference of all the movies available, click here.

Titles are alphabetized by director, and organized by year of release.

Gozāresh (1977), Abbas Kiarostami

Close-Up (1990), Abbas Kiarostami

Taste of Cherry (1997), Abbas Kiarostami

Shirin (2008), Abbas Kiarostami

Dreams (1990), Akira Kurosawa

Trans-Europ-Express (1966), Alain Robbe-Grillet

L'Homme Qui Ment (1968), Alain Robbe-Grillet

Rien Que Les Heures (1926), Alberto Cavalcanti

They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), Alberto Cavalcanti

Downhill (1927), Alfred Hitchcock

The Lodger (1927), Alfred Hitchcock

Elstree Calling (1930), Alfred Hitchcock and Adrian Brunel

The 39 Steps (1935), Alfred Hitchcock

Sabotage (1936), Alfred Hitchcock

Young and Innocent (1937), Alfred Hitchcock (Part I / Part II)

The Lady Vanishes (1938), Alfred Hitchcock

Rebecca (1940), Alfred Hitchcock

Spellbound (1945), Alfred Hitchcock

Notorious (1946), Alfred Hitchcock

The Paradine Case (1947), Alfred Hitchcock

Under Capricorn (1949), Alfred Hitchcock

The Trouble with Harry (1955), Alfred Hitchcock

Salomé (1923), Alla Nazimova and Charles Bryant

Goodbye Again (1961), Anatole Litvak

Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Rublev (1966), Andrei Tarkovsky (Part I / Part II)

Solaris (1972), Andrei Tarkovsky (Part I / Part II)

Stalker (1979), Andrei Tarkovsky

Nostalghia (1983), Andrei Tarkovsky

The Sacrifice (1986), Andrei Tarkovsky

Very Nice, Very Nice (1961), Arthur Lipsett

21-87 (1963), Arthur Lipsett

A Trip Down Memory Lane (1965), Arthur Lipsett

The Chase (1946), Arthur Ripley

A Separation (2011), Asghar Farhadi

Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), Béla Tarr

The Turin Horse (2011), Béla Tarr

Un Homme Qui Dort (1974), Bernard Queysanne

Il Conformista (1970), Bernardo Bertolucci

By the Bluest of Seas (1936), Boris Barnet

Sherlock Holmes Jr. (1924), Buster Keaton

The General (1926), Buster Keaton

Steamboat Bill (1928), Buster Keaton

Mikaël (1924), Carl Theodor Dryer

Love One Another (1922), Carl Theodor Dryer

Night Train to Munich (1940), Carol Reed

The Way Ahead (1944), Carol Reed

Odd Man Out (1947), Carol Reed

The Running Man (1963), Carol Reed

Behind the Screen (1916), Charles Chaplin

The Gold Rush (1925), Charles Chaplin

City Lights (1931), Charles Chaplin

Modern Times (1936), Charles Chaplin

Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Charles Chaplin

Statues Also Die (1953), Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet

La Jetée (1962), Chris Marker

Sans Soleil (1983), Chris Marker

If I Had Four Dromedaries (1966), Chris Marker

The Seventh Veil (1945), Compton Bennett

Come Back, Little Sheba (1952), Daniel Mann

Brief Encounter (1945), David Lean

Oliver Twist (1948), David Lean

Madeleine (1950), David Lean

Summertime (1955), David Lean

Il Sorpasso (1962), Dino Risi

The Monsters (1963), Dino Risi

Shockproof (1949), Douglas Sirk

Interlude (1957), Douglas Sirk

Man With a Movie Camera (1929), Dziga Vertov

Twenty Years Later (1984), Eduardo Coutinho

Mikey and Nicky (1976), Elaine May

Agony: The Life and Death of Rasputin (1981), Elem Klimov

Come and See (1985), Elem Klimov

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), Elia Kazan

A Face in the Crowd (1957), Elia Kazan

The Kreutzer Sonata (1956), Éric Rohmer

Stéphane Mallarmé (1968), Éric Rohmer

Ninotchka (1939), Ernst Lubitsch

That Uncertain Feeling (1941), Ernst Lubitsch

Journey Into the Night (1921), F.W. Murnau

Faust (1926), F.W. Murnau

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), F.W. Murnau

City Girl (1930), F. W. Murnau

Tabu (1931), F. W. Murnau

Love in the City (1953), Federico Fellinni …

La Strada (1954), Federico Fellini

The Swindlers (1955), Federico Fellini

Nostos: The Return (1989), Franco Piavoli

Voices Through Time (1996), Franco Piavoli

Landscapes and Figures (2002), Franco Piavoli

Fragments (2012), Franco Piavoli

7th Heaven (1927), Frank Borzage

A Farewell to Arms (1932), Frank Borzage

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Frank Capra

Meet John Doe (1941), Frank Capra

Marketa Lazarová (1967), František Vláčil

Die Nibelungen: Siegfired (1924), Fritz Lang

Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache (1924), Fritz Lang

Metropolis (1927), Fritz Lang

M (1931), Fritz Lang

Hangmen Also Die (1943), Fritz Lang

Scarlet Street (1945), Fritz Lang

Cloak and Dagger (1946), Fritz Lang

House by the River (1950), Fritz Lang

Major Barbara (1941), Gabriel Pascal

The Cigarette (1919), Germaine Dulac

The Battle of Algiers (1966), Gillo Pontecorvo

Coração Materno (1951), Gilda de Abreu

Death Laid an Egg (1968), Giulio Questi

Intermezzo: A Love Story (1939), Gregory Ratoff

Simple Men (1992), Hal Hartley

Hamlet (1921), Heinz Schall and Svend Gade

Kiss of Death (1947), Henry Hathaway

Woman in the Dunes (1964), Hiroshi Teshigahara

After Life (1998), Hirozaku Kore-eda

Bringing Up Baby (1938), Howard Hawks

His Girl Friday (1940), Howard Hawks

Hard, Fast and Beautiful (1951), Ida Lupino

The Hitch-Hiker (1953), Ida Lupino

Crisis (1946), Ingmar Bergman

Summer Interlude (1951), Ingmar Bergman

Summer With Monika (1953), Ingmar Bergman

The Seventh Seal (1957), Ingmar Bergman

Wild Strawberries (1957), Ingmar Bergman

The Virgin Spring (1960), Ingmar Bergman

Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Ingmar Bergman

The Silence (1963), Ingmar Bergman

Winter Light (1963), Ingmar Bergman

Persona (1966), Ingmar Bergman

Hour of the Wolf (1968), Ingmar Bergman

Shame (1968), Ingmar Bergman

The Passion of Anna (1969), Ingmar Bergman

Cries and Whispers (1972), Ingmar Bergman

La Belle Noiseuse (1991), Jacques Rivette

Playtime (1967), Jacques Tati

Man Friday (1975), Jack Gold

Diamonds of the Night (1964), Jan Němec

Who Saw Him Die? (1968), Jan Troell

The Flight of the Eagle (1982), Jan Troell

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970), Jaromil Jireš

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hoo U?

A spirited discussion is raging on Facebook now, the good kind of spirited discussion, an enthusiastic exchange of ideas and ideals, not a snark fest.

The top is a deceptively simple one: Who are the characters various actors played?

Let me clarify:

It began as a trivia challenge to name actors who have won Oscars for playing the same character.

And there in lays the debate.

How exactly are we defining a character.

This all sounds trivial, and to be frank this part of the discussion is, but it’s gonna get deep by the end.

Trust me.

So here’s the kickoff:

Marlon Brando won a Best Male Performance Oscar for playing Vito Corleone in The Godfather; Robert DeNiro won a Best Male Supporting Performance Oscar for playing Vito Corleone in The Godfather II

Heath Ledger won a Best Male Supporting Performance Oscar for playing the Joker in The Dark Knight; Joaquin Phoenix won a Best Male Performance Oscar for playing the Joker in Joker.

(Trivia bonus: Kate Winslet and Gloria Stuart received Oscar nominations for playing the same character at different stages of her life in Titanic, and Winslet and Judi Dench were both nominated for playing the same character at different stages in Iris as well; plus Peter O’Toole was nominated twice for playing Henry II in Beckett and The Lion In Winter which technically counts as a sequel…)

The Facebook debate is over whether Ledger and Phoenix were actually playing the same character.

Now in the case of the former, The Godfather II is a continuation of the same story in The Godfather by the same creative team with much of the original cast reprising their roles, the Oscars going to two actors who played the same character at different stages of their life (BTW, where's the love for Oreste Baldini, who played Vito as a young boy?).

The two films were re-edited and combined with The Godfather III to make a nine-hour and 43-minute miniseries The Godfather Trilogy.

It is clear the creators’ intent from the beginning was for audiences to accept Baldini / DeNiro / Brando as the same person at various stages of his life.

The Ledger Joker and the Phoenix Joker cannot possibly be the same character for a wide variety of internal continuity issues separating the two films. The creators of Joker went out of their way to state their version of the character was not The Dark Knight version.

Unlike The Godfather movies, you can’t link up the various live action Batman / Suicide Squad / Joker stories into a single coherent narrative (especially since you have to drag in the live action Supeman and Wonder Woman movies and TV shows as well).

. . .

Can different actors play their version of the same character in otherwise unlinked productions?

Of course they can.

Stage plays do it all the time.

If you start with the same exact text, then clearly any number of actors can play Hamlet or MacBeth or Willy Loman.

The problems arise when one goes afield of the text.

. . .

In 1932 Constance Bennett made a movie called What Price Hollywood? that did okay but really didn’t set the world on fire.

In 1937 Janet Gaynor remade that film as A Star Is Born, the story changed to give it a tragic yet uplifting conclusion; her version was a big hit and Gaynor received an Oscar nomination.

In 1954 Judy Garland remade A Star is Born as a musical and that proved a big hit, and Garland received an Oscar nomination.

In 1976 Barbara Streisand took a swing at the material with a country-western version of A Star Is Born and while she got an Oscar nomination, audiences were unreceptive.

In 2018 Lady Gaga remade A Star Is Born and received both an Oscar nomination for her role and an Oscar win for her song.

Question:

Are they all playing the same character? Each played a character that started their film with a different name than the other versions, but the Gaynor / Garland / Streisand / Gaga versions all end with the central character proudly proclaiming they are “Mrs. Norman Maine.”

Same character?

. . .

There’s no argument that William Gillette, Basil Rathbone, and Benedict Cumberbatch all played Sherlock Holmes, even when their productions took certain liberties with the stories.

But Sherlock Holmes is not an idiot, and Michael Caine played Holmes as an idiot in Without A Clue.

Was he playing the same character as Gillette / Rathbone / Cumberbatch?

(Ironically Peter Cook played a very recognizable and wholly credible Holmes in his farcical send up of The Hound Of The Baskervilles with Dudley Moore.)

Did George C. Scott play Holmes in They Might Be Giants? Almost everybody else in the story thinks he’s a New York banker who’s suffered a nervous breakdown and only thinks he’s Holmes, but Scott believes he is Holmes 100% and throughout the film other people he encounters accept him as Holmes at face values.

He functions as Holmes throughout.

And in the end, the audience is left in a weird place, not really knowing what his fate may be, not absolutely sure if he is a bonkers banker but maybe…somehow…he is Sherlock Holmes…

. . .

Did John Cassavettes in Tempest and Walter Pidgeon in Forbidden Planet play the same character? Were either of those roles Shakespeare’s Prospero?

Did Christopher Lee play the same character in Horror Of Dracula and its sequels, in Count Dracula, and in In Search Of Dracula? (The producers of Count Dracula sure went to great pains to explain their version was a different and more accurate version than the Hammer version of the character, and In Search Of Dracula cast Lee as Vlad Tepes who was the real life historical figure Bram Stoker based his novel on.)

For that matter, is Count Orlok in Nosferatu: A Symphony Of Terror actually Dracula? A European court awarding lawsuit damages to Bram Stoker's widow sure thought so.

Along similar lines, was Bela Lugosi playing Dracula in Columbia's Return Of The Vampire? Universal's lawyers sure thought so.

Did Jim Caviezel in Passion Of The Christ, Max von Sydow in The Greatest Story Ever Told, Paul Newman in Cool Hand Luke, and Michael Rennie in The Day The Earth Stood Still all play the same character?

Did Toshiro Mifune, Clint Eastwood, and Bruce Willis all play the Continental Op?

Did Clint Eastwood play the same character in all three Dollar films?

Did Vincent Price, Charlton Heston, and Will Smith all play the same character?

Did Leonardo DiCaprio play the same character Steve McQueen played in The Great Escape (even if just for one brief scene) or did he play a character who played a character Steve McQueen played in The Great Escape?

Ooh, here's a good one!

Lon Chaney Jr starts Ghost Of Frankenstein playing the same monster Boris Karloff played in the original Frankenstein / Bride Of Frankenstein / Son Of Frankenstein trilogy, but by the end gets Ygor's brain (Bela Lugosi) transplanted into his body and speaks / thinks / acts briefly as Ygor in Frankie’s body.

However, Frankenstein Meets The Wolfman while maintaining continuity with all four previous films cast Lugosi as the monster (because Chaney had to play the Wolfman, duh) without dialog. Glenn Strange then assumed the role again in continuity with all previous films for House Of Frankenstein, House Of Dracula, and Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein, occasionally speaking briefly in the role.

Who was Strange playing in his films? The original Karloff monster or Ygor in Frankie's bod? Are those two distinct characters?

. . .

All the above is fun trivia to debate, but it links to a much more serious question: Who are you?

That’s not a trivial matter. What constitutes out identity? What makes us who we are?

I lost my father years ago to Alzheimer’s. As my brother Robert observed, the only member of a family not affected by an Alzheimer’s diagnosis is the person suffering from it themselves.

I would talk to my father on the phone, and he was always pleasant and cheery, but about three years before he died I realized he had no idea who I was, I was just some voice on the other end of the line that mom wanted him to talk to.

My father was by nature and easy going kinda guy, and that certainly made his last few years easier for my mother and brother Rikk to cope with, but one night when I was visiting, trying to get their affairs straightened out so he could enter a nursing home, he got irritated with my mother as she was trying to help him and raised his hand as if to slap hers away.

My father never raised his hand against my mother.

Ever.

He taught me and my brothers that was something no real man ever did.

He might sound gruff on occasion but he never raised a finger, much less truck our mother.

The fact he did so in the throes of Alzheimer’s indicated that whoever he once was, he wasn’t that person anymore.

We got him into a nursing home and he lasted a little less than a year there, his mind and his memory and his personality deteriorating rapidly.

Who was he at the end?

I didn’t go to his funeral.

What was the point?

The father I knew and loved had departed long before they buried his shell.

My grandmother, on the other hand, remained her cranky, irascible self until a week and a half before she died, finding the wit to crack one last memorable joke before her body began shutting down.

. . .

The question of identity is related to consciousness, and these are referred to as “the hard question” by physicians and physicists and philosophers alike.

What makes us “us”?

How do we know who we are?

What constitutes identity?

There are no easy, pat answers.

We have textbook definitions that dance around the issue of identity and consciousness, providing enough of a foundation for us to recognize what it is we’re discussing, but no one has yet come up with a clear, concise explanation of what either phenomenon is.

It’s like saying “apples are a red fruit.”

Okay, we know what you’re talking about, but we also know that description falls far, far short of what an apple actually is.

That’s why trivial discussion like whether or not Heath Ledger and Joaquin Phoenix are playing the same character is a lot more important than it seems.

(BTW, they aren’t.

Phoenix won

his Oscar for

his version of

the Rupert Pupkin character

in a violent remake of

The King Of Comedy.)

© Buzz Dixon

#movie stars#movies#identity#consciousness#Marlon Brando#Robert DeNiro#Oresti Baldini#Heath Ledger#Joaquin Phoenix#Joker#The Godfather#Frankenstein#Dracula#Wolfman#Boris Karloff#Bela Lugosi#Lon Chaney Jr#Glenn Strange#Michael Rennie#Vincent Price#Charlton Heston#Will Smith#Toshiro Mifune#Clint Eastwood#Bruce Willis#Judi Dench#Jim Caviezel#Max von Sydow#Paul Newman#Walter Pidgeon

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wolfe in Sheep's Clothing

“I rarely leave my house. I do like it here. I would be an idiot to leave this chair, made to fit me.” (Rex Stout, Before I Die)

Nero Wolfe made his first appearance in 1934, and his adventures are still being enjoyed nearly eighty years later in books, TV shows, and - beginning on April 10, 1943 - radio dramas. Not bad for a man who hated leaving his house more than nearly anything in the world.

Wolfe, the eccentric genius who weighs a seventh of a ton, was created by writer Rex Stout. Stout made a tidy sum inventing a system to track the money school children saved in their accounts, and he used his earnings and royalties to travel the world and embark on a career as a writer. His first Wolfe novel, Fer-de-Lance, was published in 1934, and Stout would go on to write 33 novels and 39 stories featuring Wolfe until his death in 1975. Over the course of the novels and stories, Stout fleshed out the character, who enjoyed fine food and good beer, tended to his orchids, and solved mysteries when he had to earn a fee, always with the aid of his assistant (and the narrator of the stories), Archie Goodwin.

Stout’s brilliant stroke was to combine two archetypes of detective fiction into one duo. Nero Wolfe was a classic refined detective in the mold of Sherlock Holmes, right down to his eccentricities, anti-social personality, and acute agoraphobia. He could listen to clues as they were presented to him in his drawing room and deduce the solution to a crime without ever leaving the chair especially designed for his massive weight. At his side was Archie, a more streetwise sleuth in the mold of (though not nearly as hard-boiled) Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe. Archie carried a gun and had an eye for a blonde like his brethren, but he drank milk instead of bourbon and he had a playful demeanor - particularly with his boss and their frequent foil on the police force, Inspector Cramer.

Wolfe came to the screen in 1934 and 1937, but it would take almost ten years for the character to make his radio debut. From 1943 to 1944, ABC aired The Adventures of Nero Wolfe which starred J.B. Williams, Santos Ortega, and Luis Van Rooten as Wolfe during various points in the run. A falling out between ABC and Stout’s representatives prevented the series from continuing, but a new version would premier on the Mutual Network in 1946. Francis X. Bushman starred as Wolfe, with Elliott Lewis, a veteran radio actor who would soon take the director’s chair on Suspense, as Archie.

But it is the 1950 NBC series The New Adventures of Nero Wolfe that is most fondly remembered and which came the closest to capturing the essence of Stout’s stories. First and foremost, they found an actor who could fully embody Wolfe’s larger than life persona - Sydney Greenstreet.

A longtime theater actor, Greenstreet’s big break came as Kasper Gutman (“The Fat Man”) opposite Humphrey Bogart’s Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon in 1941 at age 62. After receiving an Academy Award nomination for the role, Greenstreet appeared in films like Casablanca, The Mask of Demetrios, and Across the Pacific. At age 71, he was cast as Wolfe, and his trademark characteristics - arched speech, droll laugh, deliberate intonation - perfectly fit Nero Wolfe’s larger than life personality.

Over the course of the series, no fewer than six actors were heard as Archie Goodwin. Each of the first three episodes featured a different Archie: Wally Maher (October 20); Lamont Johnson (October 27); and Herb Ellis (November 10). Beginning on November 24, actor Larry Dobkin assumed the role. Dobkin had previously been heard as Louie the cab driver on The Saint and as Detective Lt. Matthews on The Adventures of Philip Marlowe. After eight episodes, Dobkin left and his old co-star Gerald Mohr voiced Goodwin for the next four episodes. Mohr was on a radio detective roll; he had just wrapped his two-year run as Marlowe and would return for a Marlowe summer series a few months after his gig as Archie came to a close. Harry Bartell, a veteran of Escape and Dragnet as well as the Petri Wine announcer for The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, stepped into Archie’s shoes for the final ten episodes of the series.

Why so many Archies to one Nero? There’s no definite answer. Some have said it was because Greenstreet was difficult to work with; others speculate the revolving door of co-stars was a sign of retooling to see if the ratings would improve.

And while the series was well done, with even Rex Stout praising Greenstreet’s performance (he was less complimentary of the program itself), it did not fare well enough in the ratings to earn a second year. The New Adventures of Nero Wolfe wrapped up its run on April 27, 1951. Fortunately for fans, the entire series run are available in great condition. One can listen to the full run and hear Greenstreet lend his one-of-a-kind voice to Wolfe, and even with so many actors playing Archie Goodwin, none is sub-par. Each brings his own style to the character while staying true to Stout’s creation. And backing up Greenstreet and his Goodwins every week are a great cast, including Bill Johnstone as Inspector Cramer, Howard McNear, Betty Lou Gerson, Peter Leeds, and Barney Phillips.

Since the radio era came to an end, Nero Wolfe has continued to entertain fans outside of the books. Several TV shows have aired, including one single-season program starring radio veteran William Conrad as Wolfe and an absolutely delightful but criminally short-lived production on A&E with Timothy Hutton as Archie and Maury Chaykin as Wolfe. And for fans who want more audio adventures of the pair, the CBC mounted an impressive series of adaptations in 1982.

Check out this episode!

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movie Odyssey Retrospective

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949)

Walt Disney seemed to have been mentally drifting in the 1940s, producing a scattershot of films without the artistic discipline he displayed prior to Bambi (1942). His attention wavered between the package animated features, his forays into live-action features and nature documentaries, and taking mental notes about the new medium of television. As Walt approached his 50s, the strain of the work he had thrust upon his studio and himself was beginning to show. In his nurse, Hazel George, he found a rare confidant (it was a friendship, nothing more). He noted his personal need to move forward on projects, rather than tolerate any stalling. “I’m going to move on to something else because I’m wasting my time if I mess around with that any longer,” he told George about his projects stuck in development hell. That was the difficult reality facing The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad – directed by Jack Kinney, Clyde Geronimi, and James Algar – as it became the final animated feature of the package era of Disney animation.

Walt was dividing his time between this film, building a personal miniature railroad in his backyard (the genesis of the idea that would become Disneyland), a nostalgic and personal dramedy of rural turn-of-the-century America in So Dear to My Heart (1948), the start of his True-Life Adventures series of nature documentaries with Seal Island (1948), and restarting the studio’s line of non-package animated features. Of all these things, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad probably consumed the least of his attention. A feature-length adaptation of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows had been in the works at the studio in the months before the United States’ entry into World War II, but was halted due various factors: the war, the Disney animators’ strike, and Walt’s belief that Grahame’s book did not justify a feature-length treatment. Work on an adaptation of Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow began in 1946. But unlike The Wind in the Willows (which also resumed production in 1946), the adaptation of Irving’s story was always envisioned as a segment to a package film – not a standalone feature. Itching to return to animated features and still not convinced in the potential of a feature film surrounding Mr. Toad and friends, Walt announced the merging of the two projects in 1947.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad uses a live-action library as a framing device. The Wind in the Willows makes up the film’s first half; The Legend of Sleepy Hollow closes it out. Each half has a narrator that, at the time, was at their career’s peak. The opening half is narrated by Basil Rathbone (1938’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and as Sherlock Holmes in fourteen movies from 1939-1946); the concluding half by Bing Crosby (best known for his musical career, but was also an enormous box office draw with the Road to… series among other films). Both Rathbone and Crosby hold up Mr. Toad and Ichabod Crane, respectively, as exemplary characters of their home nation’s literature.

The Wind in the Willows begins in 1908 as J. Thaddeus Toad, Esq. harbors an insatiable appetite for adventure, rather than being shut in his elegant Toad Hall estate all day. His friends Rat, Mole, and Angus MacBadger (also his accountant) mostly tolerate Toad’s newest crazes. When, for the first time, Toad spots a motor car, his eyes widen and he is enamored with this newfangled contraption. Toad’s obsession turns into recklessness – leading him to some fraudulent dealings with weasels and legal trouble.

On the surface on Walt Disney’s concerns with The Wind in the Willows, I disagree that Grahame’s novel could never be a feature film.* As presented, the segment runs a neat and all-too-brief half-hour. In an era of communal moviegoing and when a single movie ticket often bought the purchaser a double feature (a B-picture followed by an A-picture, with film trailers, short films, serials, or newsreels in between), The Wind in the Willows is presented as the film’s B-segment. That should not be taken as a swipe on the segment’s quality, however. The Wind in the Willows is a marvel of narrative compactness and situational madness that tees up Alice in Wonderland (1951). Whenever necessary, the narration and newspaper headline montages accelerate the plot. The pace is breakneck, but that never threatens to make The Wind in the Willows incomprehensible. It is filled with dry English wit, benefitting from wonderful voice acting from Eric Blore (a regular supporting actor in Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers musicals for RKO) as Toad and J. Pat O’Malley (Tweedledum and Tweedledee in Alice in Wonderland, 1954’s Dial M for Murder) as Toad’s horse, Cyril Proudbottom. When both Toad and Cyril are introduced in the short song “Merrily on Our Way (to Nowhere in Particular)” – music by Frank Churchill and Charles Wolcott, lyrics by Larry Morey and Ray Gilbert – it is a perfect overture to the madcap misadventure that is about to occur.

Animator Frank Thomas’ (the dwarfs from 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Captain Hook for 1953’s Peter Pan) character designs for Toad, Rat, and Mole are simple, fluid, without too much definition (think Winnie the Pooh). As such, all three are highly expressive figures easily adaptable to the comic scenarios that stumble onto. So much is related to the audience with a crazed grin from Toad, an exasperated sigh from Rat, and Mole’s concerned face. Similar praise must also be dedicated for a side character – namely, the Crown Prosecutor designed by Ollie Johnston (the three animated principal characters in 1946’s Song of the South, the fairy godmothers of 1959’s Sleeping Beauty). The Crown Prosecutor does not appear in the film for long, but his elastic limbs and body – outside Johnston’s wheelhouse – provide a simultaneously comic and menacing contrast to the anthropomorphized animals he towers over. Like all of Disney’s package film segments before it, The Wind in the Willows has numerous instances where the backgrounds and character animations compare unfavorably to the studio’s Golden Age works. But does the lack of painterly backgrounds or character design definition mean much when the piece in question is aiming purely for laughs? Not really. This is some of the best comic filmmaking made by the Disney studios in its history, even though it seems to have been overshadowed by what happens next.

youtube

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow takes place in Colonial-era Sleepy Hollow, New York. Ichabod Crane, the town’s new schoolteacher, is a thin dandy (“lean and lanky, skin and bone / with clothes a scarecrow would hate to own”) possessing an enormous appetite. The man looks nothing like a ladies’ man, but he is exactly that – to the annoyance of town rogue and proto-Gaston, Brom Bones. Brom and Ichabod vie for the attention of Katrina van Tassel, the daughter of wealthy farmer Baltus van Tassel. Noting Ichabod’s superstitious ways, one night Brom tells the story of the Headless Horseman – a stratagem that succeeds in spooking the schoolteacher.

Mary Blair’s midcentury modernist design and coloration for Sleepy Hollow reflects the folksiness of the village, Ichabod’s occasional naïveté. Her curved lines for the surrounding countryside – notice how her trees curve in improbable ways – make it an inviting, down-home place to live. Putting the segment’s climax aside, the backgrounds lend an atmosphere similar to early autumn, as the calendar year begins to wither away.

This, of course, is turned on its head when Ichabod encounters the Headless Horseman. Blair’s backgrounds are blanketed in black, blue, and purple – emphasizing Ichabod’s physical isolation in these moments. The trees blend into an abstract tapestry, as if one cannot see only a few feet outside of the road. Outside of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’s uninteresting romantic wooing scenes, the segment is an exemplar of atmosphere and how to successfully change a film’s tone with animation. Wolfgang Reitherman’s (an animator who later became a prominent director with the Walt Disney Studios in the 1960s) smooth character animation specific to the Headless Horseman chase contrasts Ichabod’s flexibility with the sharpness of the Headless Horseman and his horse. Reitherman’s approach to the characters, combined with Blair’s style for the backgrounds, heightens Ichabod’s full-bodied terror against the Horseman’s frightening presence.

The segment’s pedestrian character animation is unfortunate and is the film’s most visible example of cost-cutting. Yet Ichabod and Brom’s designs – by Ollie Johnston and Milt Kahl (Prince Philip in 1959’s Sleeping Beauty, Tigger in the Winnie the Pooh short films) respectively – are excellent. Ichabod’s outwardly-angled, high-footed gait proclaims immediately his peculiarity in behavior and temperament. His impossibly thin body is bendable to achieve tremendous comic effect while still resembling something like a human. When providing three village women singing lessons, Ichabod (voiced, like Brom, by Bing Crosby), assumes many of Bing Crosby’s affectations while singing himself – those raised eyebrows, that jowl movement. This scene is much funnier if one is familiar with Bing Crosby’s film (and to a lesser extent, television) appearances. For Brom, his muscular frame is a first for a Disney animated feature, providing a somewhat threatening feel for the song, “The Headless Horseman” (which introduces the idea of the segment’s villain). On paper, Brom should be the segment’s antagonist, but things are not clear cut – especially because Ichabod himself has questionable motives in his pursuit for Katrina. Decades later, Kahl’s character design for Brom heavily influenced Andreas Deja’s design for Gaston in Beauty and the Beast (1991). Deja would take some of Brom’s features, add more details and exaggerations, and provide his antagonist a more sneering disposition for Gaston.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow also has the benefit of songs sung by Bing Crosby and composed by Don Raye (known for various Andrews Sisters songs) and Gene de Paul (1954’s Seven Brides for Seven Brothers). The first, “Ichabod”, is the one number I always find stuck in my head and singing to myself throughout a given day (I also notice, while singing, I’m trying to imitate Crosby’s suave delivery, to little avail). It also serves as an ideal introduction to the character – outlining his personality in less than two minutes. Midway through the segment is “Katrina”, which is as musically uninteresting as the character herself. “The Headless Horseman”, also an earworm, plays on Ichabod’s fears and is a wonderful transition into this film’s most famous sequence.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is the best animated feature from the Disney package era. Its two halves – so distinct in style and narrative approach – are incongruent, some may say an unnatural pairing. But moviegoing audiences in 1949 so used to the B- and A-picture format of film exhibition were also accustomed to feature film pairings with little rhyme or reason. A flighty musical comedy might lead into a war movie; a romantic melodrama before a fast-paced swashbuckler; a seedy film noir giving way to a grand historical epic. Many decades removed from the moviegoing attitudes of this era, the pairing of The Wind in the Willows with The Legend of Sleepy Hollow pays off due to the stylistic distinctions between these two segments. Compared to its package era predecessors, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad has taken the time to shape its characters. For Toad, his motor car mania is a mostly innocent obsession that has endured; Ichabod Crane is forever associated with a harrowing chase through a gnarled wood. Their characterizations come through despite the limitations put upon the studio’s animation staff.

A modest success for Walt Disney, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is now mostly described as a transitional film. The film sees the Disney animators flex their artistry before the resumption of the studio’s traditionally-structure animated features. Sometime during the final stages of this film’s development, Walt and his brother Roy E. Disney fought over the former’s desire to return to features, to recapture the thrill that he felt when he produced Snow White. Under protest, Roy relented and approved a budget for Cinderella (1950) – the first film of Walt Disney Productions’ “Silver Age” films. While Ichabod and Mr. Toad wound down, more resources were being pooled into Cinderella.

This was the effective end to a creatively restrictive period in the studio’s history, but also to some of the most unique offerings in the Disney filmography. Audiences have seldom seen the concise characterizations, Warner Bros.-influenced outlandish humor, romanticized American folk storytelling and propaganda, and experimental animation in a Disney animated feature to the present day. Each of these aspects could be found throughout Disney’s package films – which, for any serious fan of animated film, cannot be dismissed offhand. In a decade of war and global reconstruction, the studio stood mostly alone in the realm of feature animation. But not for much longer. In Europe, animation studio Soyuzmultfilm was beginning to distribute its films beyond the Soviet Union’s borders. And with Walt Disney’s attention straying from his animated films, his animation studio’s record of sterling creativity – already hobbled by the animators’ strike and wartime budget cuts – would be further challenged.

My rating: 7.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

This is the eighteenth Movie Odyssey Retrospective. Movie Odyssey Retrospectives are reviews on films I had seen in their entirety before this blog’s creation or films I failed to give a full-length write-up to following the blog’s creation. Previous Retrospectives include Dracula (1931), Godzilla (1954, Japan), and Oliver! (1968).

* A “feature film” – as defined by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), the American Film Institute (AFI), and the British Film Institute (BFI) – is a film lasting forty minutes or longer.

#The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad#Jack Kinney#Clyde Geronimi#James Algar#Walt Disney#The Wind in the Willows#The Legend of Sleepy Hollow#Basil Rathbone#Bing Crosby#Oliver Wallace#Mary Blair#Frank Thomas#Ollie Johnston#Wolfgang Reitherman#Milt Kahl#Disney#My Movie Odyssey

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 comfort films tagged by @edddiekaspbraks thanks bb!

1. O Brother Where Art Thou (2000) - I literally talk about this movie all the god damn time. It’s probably my all time fave, and was my film to watch when i was sick for a long time. The soundtrack! The aesthetic! The COLOURS! Plot: retelling of The Odyssey by Homer set in 1937 Mississippi follows Ulysses Everett McGill and his companions Delmar and Pete, as they escape from prison to find a treasure Ulysses had buried before getting caught.

2. Sherlock Holmes (2009) - This movie!! is so fun!!! RDJ and Jude Law!!!!! Rachel McAdams!!!! Again another movie with an amazing soundtrack and fantastic visuals, which I’m beginning to think is the key to my heart. Plot: it’s a Sherlock Holmes adaptation.

3. The Maze Runner (2015) - I have such fond memories of watching this movie for the first time in the theatre and feeling so happy for DAYS afterwards. I loved these books for so long and seeing it on screen for the first time was magical. Plot: adaptation of The Maze Runner series follows a boy named Thomas who is thrown into a strange community surrounded by a giant maze with no memory of who he is beyond his first name, with a few dozen other boys in the same boat.

4. ParaNorman (2012) - Stop motion!!! really fucking amazing stop motion!!!! if you haven't seen this i highly suggest doing so. Plot: Follows a boy named Normal who can see and communicate with ghosts, who happens to live in a town plagued by a deadly curse.

5. Labyrinth (1986) - I could watch this movie a hundred times and never be sick of it. Plot: Sarah journeys through a labyrinth to recover her baby brother from the Goblin King. David Bowie is in it and its great, pls watch.

6. The Man From Uncle (2015) - 60S!!! SPIES!!!! Plot: adaptation from a beloved 1960s sitcom about an American and Russian spy who are forced to work together to stop some bad guys, working with the daughter of a German scientist.

7. Stand By Me (1986) On the more “normal” side of the Stephen King spectrum, although four 12 year olds still go off on a journey to find the body of some guy who was murdered to collect the reward money, so. coming of age! oddly touching! charming in the way that only 80s movies can be. Plot: set in the fictional town of Castle Rock, four friends set out on a journey to a lake to uncover the body of a man who was recently killed, learning more about one another and their very different home lives along the way.

i tag @boreoku @taste0fdreams @persnickett @sealotter @seaselkie @comebacknow @dustinhendrsn @smorgasbordofobsessions and whoever else would like to do it!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Works Entering the Public Domain in 2020

At the stroke of midnight hundreds if not thousands of books, songs, paintings, etc. first published in 1924 will be entering the public domain in the United States, the second year in a row this has happened after a twenty year extension that went into effect near the end of 1998, and as the year comes to a close let us take a look at some of the highlights of works I find of interest that will soon be available to all, including the first film adaptation of Peter Pan and the first appearance of the character who would later become known as Winnie the Pooh. I should note that for the purposes of this article that I will be focusing mainly on United States copyright law as laws differ from country to country and some of the works below will still be copyrighted in some countries, along with a few that will only be entering the public domain in the United States for reasons that will be explained.

How long copyright lasts

Before diving into the meat of the article, it will be helpful to explain the basics of how long copyrights last and what the public domain is. All creative works are protected for a certain amount of time after fixation and/or publication and after the copyright for a work expires, it enters the public domain where all can use it however they please in most cases. How long that copyright lasts depends on the laws on the country and in some cases the type of work. In the United States, copyrights on all works published before 1978 last for a period of 95 years with a few exceptions. The main exception are sound recordings as, due to a wide range of state and federal legal complications going back decades, none will enter the public domain prior to the start of 2022 when all recordings released before 1923 will become public domain. The other main exception to the 95 year rule is if a work was first published before 1978 and did not have a copyright notice, which released a work into the public domain immediately, or was released before 1964 and its copyright was not renewed after 28 years. These rules only apply to works that were first published in the United States and does not apply to most foreign works as, due to a number of reasons that will not be covered here, many works originating from outside of the U.S. that expired for such reasons had their copyrights restored in the mid-1990s as most countries do not have formality requirements, and even the ones who did largely abandoned them long ago.

In most countries outside of the United States and all works published after 1977 in the U.S , copyrights last for a certain amount of time after the author’s death, usually 50 or 70 years though others have terms that are either longer or shorter. Only a handful of countries have terms outside of that range with a few going as low as around 20 years after the author dies, a few go up to 75 and 80 years, and Jamaica and Mexico have the longest terms with 95 and 100 years after the author’s death respectively. Some, like India, go between the two with a term of 60 years after the author’s death. Sound recordings and corporate works usually have fixed terms, but they not always. Things get even more complicated for movies as while many countries give them a fixed copyright length, others do not and determining the author of a film can be complicated. For the purposes of this article when determining a film’s copyright status outside of the U.S. I will use the laws for movies used in countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany which determines the copyright length based on the last survivor of the main director, screenwriter, and composer.

In many countries, a copyright set to expire in a given year expires on January 1 of the following one. This is why all works from 1924 are entering the public domain at the start of 2020 in the U.S. instead of entering it at various points throughout 2019.

Works entering the public domain outside of the U.S.

While I will be focusing on the United States public domain in this article, I will also try to determine the status of a work in other countries if possible and start off by mentioning a few authors whose works are entering the public domain in countries with life+70 and life+50 terms, with some notable works being listed in parenthesis.

In life+70 countries, all works from authors who died in 1949 will be entering the public domain. Some examples include works by composer Richard Strauss (Don Juan, Also sprach Zarathustra), Margaret Mitchell (Gone With the Wind), and Richard Connell (The Most Dangerous Game). The original 1922 version of Nosferatu, considered to be one of the earliest vampire films and the first (though unauthorized) adaptation of Dracula, is also entering the public domain in many countries including its native Germany as screenwriter Henrik Galeen died in 1949. In life+50 countries works from authors who died in 1969 will enter the public domain including songwriters such as Frank Loesser (Baby, It's Cold Outside).

Works entering the public domain in the U.S.

This is a list of selected works from 1924 broken down into categories:

Music:

· Tzigane by Maurice Ravel

o Ravel died in 1937, so this composition is public domain in most of the world.

· Rhapsody in Blue by George Gershwin

o Gershwin died in 1937, so this composition is public domain in most of the world.

· It Had To Be You by Gus Kahn (lyrics) and Isham Jones (music)

o Gus Kahn died in 1941, so the lyrics are public domain in life+70 countries. Isham Jones died in 1956, so the music is public domain in life+60 countries.

· All Alone, The Call of the South, Lazy, and What’ll I Do by Irving Berlin

o Irving Berlin died in 1989, so these songs are still copyrighted in most of the world.

Movies:

· He Who Gets Slapped, starring Lon Channey and directed by Victor Sjöström

o Screenwriter Carey Wilson died in 1962, so the film is public domain in countries where the term is life+50.

o The movie is based on a play by Leonid Andreyev that was published in 1914. Since he died in 1919, the play is public domain worldwide and has been for some time.

· Peter Pan, starring Betty Bronson and directed by Herbert Brenon.

o Screenwriter Willis Goldbeck died in 1979, so this film is still copyrighted in most of the world.

o This movie is based on James M. Barrie’s play (which would be published in its final form in 1928) and had his direct involvement. Since he died in 1937, the play is public domain in most countries besides the U.S. (though the 1911 novel version entered the public domain long ago) and a limited exception in the United Kingdom regarding royalties.

Novels and Short Stories:

· A few works by Agatha Christie including the novel The Man in the Brown Suit along with several short stories featuring characters such as Hercule Poirot and Tommy and Tumpance.

o Agatha Christie died in 1976, so these works are still copyrighted in most of the world.

o The Man in the Brown Suit Introduced the character Colonel Race, who would go on to appear in later Christie works such as Death on the Nile.

· The Illustrious Client, The Sussex Vampire, and The Three Garridebs by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

o Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Doyle died in 1930, so these stories are public domain in most countries.

o These are among the last of the original Sherlock Holmes stories. Not including the above stories, only six of the original 56 stories are copyrighted in the U.S.

· The Most Dangerous Game by Richard Connell

o As mentioned earlier, this work is also entering the public domain in life+70 countries as Richard Connell died in 1949.

o The 1932 film version is also public domain in the U.S. as its copyright was never renewed.

· When We Were Very Young by A.A. Milne

o Since A.A. Milne died in 1956, this book is public domain in life+60 countries.

o This is a collection of poems. One of them, “Teddy Bear” was the first appearance of a character named Edward Bear who would be given the name Winne the Pooh in 1925. Under that name, he would go on to be featured in many stories published between 1926 and 1928.

· Grampa in Oz by Ruth Plumly Thompson

o Since Ruth Plumly Thompson died in 1976, this book is still copyrighted in most countries.

o This is the eighteenth Oz book and the fourth written by Thompson, who continued the series following L. Frank Baum’s death in 1919. All of the Oz books in the “famous forty” published after this are still copyrighted with the exception of seven that were not renewed.

· The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann

o Since Thomas Mann died in 1956, this book is public domain in life+60 countries.

o The first English translation of one of Mann’s earlier works, Buddenbrooks¸ is also entering the public domain.

· The Dream by H.G. Wells

o Since H.G. Wells died in 1946, this book is public domain in life+70 countries.

Comics and Cartoons:

· Roughly 20 Felix the Cat shorts, though some were already in the public domain as they were not renewed.

· Ten of the Disney Alice Comedies.

· Little Orphan Annie by Harold Gray debuted in 1924 as a Sunday and daily strip.

o Since Harold Gray died in 1968, these comics are public domain in life+50 countries.

Works not included above and why:

If you looked at the works listed above some of you might notice a few notable works first released in 1924 that I did not mention and there is a reason for that. In the film section some might have noticed that the original version of The Thief of Baghdad staring Douglas Fairbanks and directed by Raoul Walsh was not listed. Similarly, the original version of Gertrude Chandler Warner’s The Boxcar Children is missing from the book section. The reason I omitted these is because they were already in the public domain since neither of them had their copyright renewed. However, this only applies in the U.S. as both works are still copyrighted outside of the U.S. since Raoul Walsh died in 1980 and Gertrude Chandler Warner in 1979. One should also exercise caution with The Boxcar Children as the similar though heavily revised version published in 1942 did have its copyright renewed along with its sequels. The same is also true of the 1940 remake of The Thief of Baghdad.

In the coming weeks and certainly over the course of the year, I will try to post some of the above works, mainly some of the poems, short stories, and arrangements of some of the musical works.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Time Before, Part 1

Hi, and welcome to my first fanfic. I’m a little terrified right now, but it’s good terror, right? This story is also posted at AO3. But please, read along and enjoy how I imagine it went when Claire Beauchamp met Frank Randall.

July 1937

We had just returned to London, Uncle Lamb and I, stepping off the train at Victoria Station and emerging into the bustle of the city. It was a far cry from the dig in South America, where we had been excavating Inca ruins and living, shall we say, rather rougher than would be expected for an Oxford-educated scholar and his gently-reared niece. I would miss the quiet of the wilds of Peru, but was excited to be back in the center of things.

I slung my satchel over my shoulder, following Uncle Lamb and his manservant Firouz up the busy street. The miasma of the city — smoke, automobile exhaust, rubbish and just a tinge of vomit — hit my nostrils and I sighed, contentedly. We had been in Peru nearly nine months while Uncle Lamb worked the dig at Ollantaytambo, studying the 15th century city’s military defences and excavating weapons to send to London for further study. While I had grown up following Uncle Lamb on his expeditions, I was looking forward to just a bit of stability.

“I need to go to my offices before we head to our lodging, Claire,” Uncle Lamb said as we stopped at the street corner. Firouz, his dark hair gleaming in the sunlight, was hailing us a cab. “Would you like to go with Firouz straight to the flat?”

“No, I’ll come with you,” I said, shaking out my curls in the breeze. “I haven’t much to do at the flat by myself.”

Firouz loaded our baggage into the trunk of the cab and I slid into the backseat next to Uncle Lamb. “Why are you so keen to get to the college?” I asked, as the cab sped away toward, I assumed, the British Museum. “We’ve been away for months, surely another day won’t delay anything.”

“Oh, I’ve had a fascinating query from a junior professor that I wish to start on as soon as possible, about a point of French philosophy as it relates to Egyptian religious practice. Can you imagine?”

“Not even a little bit.” I smiled at him, charmed by his never-ending enthusiasm for his research. I was much more interested in getting out at night, myself, sans escort. The opportunities for cinema-going, dancing or cavorting with handsome men had been rather thin on the ground in Peru. I had spent more than nine months longing for a little fun.

Well, maybe not longing that hard, I thought, remembering some of the more steamy nights in the jungle, keeping not-so-cool with one of the more attractive graduate students working on the dig. Helmut was tall and sandy-haired, with brown eyes and a devastating smile, and a nigh-unquenchable thirst for the only girl in miles. We had a fair bit of fun sneaking about the ruins, and he had promised to write, but I wasn’t planning on holding my breath.

I did, however, put thoughts of Helmut and his callused hands aside, worried my face would reveal more than I intended. But Uncle Lamb had his nose in his research notebook. We never discussed my liaisons, and I honestly wasn’t sure how much he knew about my social life. He had given me a very scientific explanation of where babies come from at age 10, and we had never spoken of it again. My uncle was an oddly distracted man, but I was sure he couldn’t have been totally oblivious to my late-night comings and goings or flirtations during mealtimes. And he had been going on about the vestal virgins again...

But no matter. Helmut was still in Peru, and I was back in London. We would be in the city for at least six months — Uncle Lamb wanted time to finish his latest book about his research and ensure the relics he sent back to the museum were properly preserved, catalogued and archived. To my left, Hyde Park’s trees loomed tall and rows of neatly-manicured flowers bloomed; they were a far cry from the overgrown and unruly foliage of the jungle. Everything here, from the black cabs, to the city squares, to the newspaper cones of chips being sold on the street corners, to the Marble Arch we were zooming by, practically screamed their Englishness. It should’ve felt like a homecoming, I thought, although it really just felt like the next big adventure.

I had grown up on the road with Uncle Lamb, traveling from dig to dig, exotic jungle to historic ruin to blazing desert, since my parents’ deaths when I was five. I was coming up on 19 now, and hadn’t spent more than two years all together in England since. We came back for short stints, so Uncle Lamb could present his work to his esteemed colleagues, or to re-supply for our next expedition, but I was generally more comfortable living out of a rucksack and in a tent than in our flat in the city.

The cab stopped, and I saw the marble columns of the British Museum rise stoically into the London skyline. Uncle Lamb slid out of the cab, and I followed onto the curb. A small flock of pigeons descended on a bit of dropped crumb on the sidewalk, squawking and squabbling, as Uncle Lamb leaned in the front window, paid the gruff cabbie, and said a final few words on instruction to Firouz. He then, with a look of great satisfaction, held out his elbow for me to take, and I waved goodbye to Firouz as the cab sped away as we grandly strolled up the iconic steps, into the temple of his beloved work.

His office was in the far-off academic wing of the museum; a small window looked over a picturesque courtyard with a gleaming white statue of Artemis. It was filled, almost from floor to ceiling, with books, papers and parchments. Uncle Lamb’s desk was tucked in a corner and similarly covered in academic detris — although, I knew there was some method to the madness that was only quite intelligible to Uncle Lamb. He always left strict instructions that his office and papers be left alone while he was out of the country.

I wandered around the office, picking things up and putting them down while Uncle Lamb sat at his desk and pulled out his traveling notebook once again, and then fumbled through some correspondence. While his office was filled with objectively fascinating antiquities, there was nothing I hadn’t seen before, and I could tell he was settling in for a long session of work.

“Uncle Lamb, do you think you’ll be long? I might visit the Reading Room.”

“I’ll only be a few hours or so. Then we’ll go to the pub and get supper.”

I glanced at a clock — it was just after three in the afternoon, and we had been traveling all morning. “Of course, I’ll come back later,” I said, knowing “a few hours” could be anywhere between two and ten, depending on how absorbed Uncle Lamb became in his work. But, the museum closed at a reasonable hour and I could insist upon dinner when I returned.

I had had a reader’s ticket from the principal librarian since I was a girl, under the sponsorship of Uncle Lamb, taking out books on botany, flora and fauna to look at the pictures. The dome of the Reading Room rose above me as the silence of the library fell. It was heavily populated for an afternoon with no classes in session; the room was filled with the harsh glow of summer sunshine. I took a left and started to wend my way around the stacks, through physics and engineering, stopping at periodicals. I wasn’t particularly fussed on Ladies Companion, full of recipes and advice on raising children as it was, but I glanced through Nash’s, hoping for a glimpse of the latest film stars or glamorous dresses. No such luck; though, I dolefully noted how straight the hairstyles had become. I could never tame my curls into a sleek bob that would fit neatly under a cloche hat, and Uncle Lamb loathed hats on women anyway.

Abandoning the magazines, I meandered toward fiction, the next section in my circle around the room. Was there a new Agatha Christie, perhaps? I had only brought Dickens to Peru and was sorely in need of a change of pace. I was reaching for a maroon-covered volume with gold-gilt lettering that caught a ray of sunshine from the overhead windows, when I heard a soft footfall behind me.

“'No spring nor summer beauty hath such grace as I have seen in one autumnal face,'” a deep and rather dreamy voice said behind me. I turned to look over my shoulder. A rather handsome man, with dark hair, hazel eyes and a distinguished face, smiled.

“John Donne.”

“You know Donne but you’re choosing from the penny dreadful section?”

I was surprised by the jibe, although I supposed I shouldn’t have been. He cut a dashing figure for an obvious academic. His practical brown suit was of quality, but rumpled as if he had been sitting at a desk for hours; his tie was just slightly undone; and there was a small ink stain on his white shirt next to the lapel of his jacket.

“Since you’re so fond of Donne, try this one,” I said, leaning in conspiratorially, “‘Humiliation is the beginning of sanctification.’”

“Who said anything about humiliation?” The man clearly thought he was charming me.

I raised my voice just above an acceptable level for a library, to make sure anyone in the next aisle would hear. “Agatha Christie hardly writes penny dreadfuls, so don’t insult my taste in literature in an attempt to make my acquaintance.” I smiled beatifically at him, and watched the assured, charismatic grin fall from his face.

“My apologies, miss...” Recovering quickly, he raised his eyebrows as if expecting me to fill in the blank.

Raising my own eyebrows, I decided not to give him the satisfaction. “Not at all,” I said, polite to the point of pointedly rude. I turned back to the shelves, dismissing and forgetting him in the same moment. Not quite finding what I was looking for — there was only Murder on the Orient Express, which I had read so many times on a trip to Egypt two years before I could recite it from memory — I walked a few paces, reflecting I had never delved into the world of Sherlock Holmes.

The librarian-on-duty, who had known me since I was small, shooed me out of the Reading Room two hours later, with few new novels and a book of poetry tucked under my arm. I took the long route back to Uncle Lamb’s office, preparing to cajole him into abandoning his studies so we could eat. It being our first meal back on English soil, I reckoned it would be a relatively easy task — Uncle Lamb gloried in a good shepherd’s pie, which was not something served at camp in Peru.

I could hear the sound of raucous academic debate coming from Uncle Lamb’s office when I turned down the corridor. It seemed Uncle Lamb had hit his stride on the finer points of tomb contents in ancient Egypt’s Middle Kingdom, and I hovered just out of sight at the door waiting for a lull in conversation. As I expected, it was a few moments before I heard Uncle Lamb pause for breath, and I knocked softly and started to push open the door. “Uncle, are you ready for... oh.”

Uncle Lamb was sitting at his desk, and the man he was speaking with — obviously the young scholar who wanted to talk French philosophy — turned around in his seat. It was him! The dashing man who objected to mystery novels was here, in my uncle’s office.

“Claire, do come in,” Uncle Lamb said jovially, standing to greet me. His guest stood as well. “Dr. Randall, allow me to introduce my niece, Claire Beauchamp. Claire, this is Dr. Franklin Randall; he’s a don in the University of London’s history department.”

Well, now he knew my name. “How do you do, Dr. Randall.” I stuck out my hand to shake, but he took it in his and raised it to his lips, kissing it gently on the back. His lips were warm, just-so-slightly dry; it sent a small shiver up my arm that coiled deep in my belly.

“How do you do, Miss Beauchamp.” His voice was just as dreamy as it had been in the Reading Room, assured and educated, soft but with a hint of a rasp. I nodded my head in acknowledgement, and as he, seemingly reluctantly, let go my hand, I turned to my uncle.

“I’m so sorry to interrupt. I can come back later.”

“Oh, no, dear,” Uncle Lamb said, coming around his desk. “We were just discussing some burial practices, you know, the Egyptians’ beliefs in this area...”

I laughed. “Yes, I know. We’ve spent enough time excavating their tombs.”

“Well, yes, of course, dear. But you must be starved.” He turned to Dr. Randall as he plopped his hat on his head. “We’re going to have a bite of supper down at the pub, would you care to...”

“I’m sure Dr. Randall has other...” I started to object.

“I would be pleased to join you,” Dr. Randall perked up immediately. “I’m a bit peckish myself.”

End of part 1

Part 2

145 notes

·

View notes

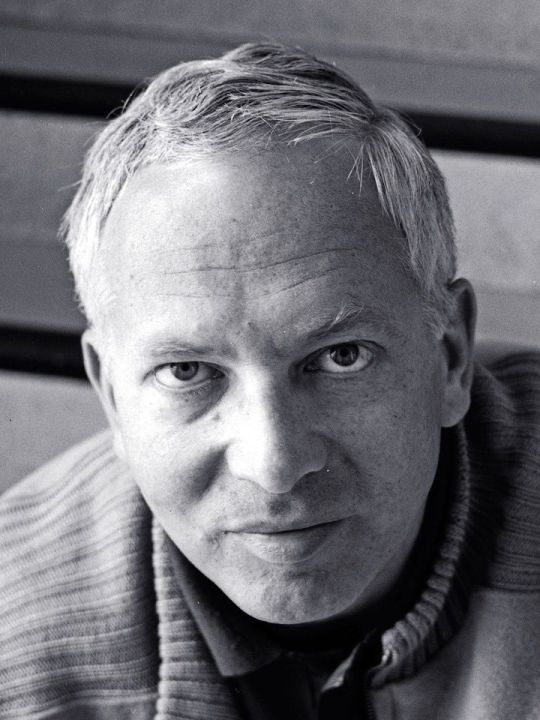

Photo

That moment when a 1922 film based on William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes play written before the creation of Sebastian Moran understands the Moriarty/Moran relationship better than about 98% of non-canonical texts involving Moran. (How much of Moran do we actually owe to William Gillette do you think? Possibly a fair bit. Even the names sound similar (Sebastian/Bassick. Maybe that’s why ACD changed his mind about Moran’s first name). Although I believe ACD did have a character like Moran in mind before the play was written; Moriarty’s network was such that he would have needed a right hand man and he obviously had an assassin type character in mind also when he wrote The Final Problem).