#Petalonamae

Photo

A Portuguese man o’war (Physalia physalis) on Capelinhos beach, Faial island, Azores

by ChilliPepper0713

#portuguese man o war#man o war#Physalia physalis#physalia#Physaliidae#siphonophorae#hydrozoa#Petalonamae#wildlife: azores#wildlife: portugal

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

WAR AND HATE ON PLANET EARTH

WELCOME TO THE PHYLUM PHIGHT

A BRACKET WHERE THE 37 KNOWN PHYLA OF ANIMALS (extant and otherwise) WILL BATTLE TO THE DEATH. ONLY ONE MAY BE CROWNED CHAMPION-- AND ASCEND TO THE STATUS OF KINGDOM (i have this power)

WHO WILL IT BE? THE CHORDATES, CONTAINING EVERY KNOWN VERTEBRATE INCLUDING YOU AND ME? I FEEL LIKE THAT'S A BIAS. MAYBE THE HUMBLE TARDIGRADES, THE INTERNET'S FAVOURITE EXTREMOPHILES? OR WILL IT BE THE PENIS WORMS? I FEEL LIKE IT'S GONNA BE THE PENIS WORMS.

TOURNAMENT STRUCTURE:

ok ditching allcaps now <3

round 0

preliminary face-off between the odd phellas. lasting one (1) week to give bitches time to mobilise

protoarticulata VS rhombozoa

2. phoronida VS vetulicolia

3. petalonamae VS xenacoelomorpha

4. porifera VS rotifera

5. platyhelminthes VS saccorhytida

round 1

all round 1 poll-batches will last one (1) day because dear god there are so many of them. there will however be a cooldown of like, a couple days or something between batches because i am but one man

batch 1 - BATCH TO THE DEATH

6. priapulida VS winner of 1

7. annelida VS chaetognatha

8. trilobozoa VS micrognathozoa

9. bryozoa VS lorcifera

batch 2 - THE BATCHENING

10. tardigrada VS winner of 2

11. brachiopoda VS gastrotricha

12. mollusca VS winner of 3

13. nematomorpha VS gnathostomulida

batch 3 - BATCHETFIELD HIGH

14. chordata VS winner of 4

15. archaecyatha VS cycliophora

16. nematoda VS nemertea

17. ctenophora VS kinohyncha

batch 4 - I HAVE RUN OUT OF BATCH PUNS

18. arthropoda VS winner of 5

19. agmata VS entoprocta

20. cnidaria VS onychophora

21. echinodermata VS hemichordata

round three wait and see!!!

this bracket doesn't require nominations, as the candidates are already set out all nicey for us by Science. how cool of them. Now we make them beat each other senseless for our sick amusement :)

HOWEVER please send asks, suggest representative species or images to make sure we see them at their best, send propaganda/fun facts youd like the filthy electorate to know before they condemn your fav to the deepest most basal pits of taxonomic superhell. lets all get to know the Beasts together. Before we make them fight to the death.

-mod riz (he/him)

ROUND 0 START: APRIL 10TH

#phylum phight#phylum-phight-tourney#tumblr tournament#taxonomy#tumblr polls#tournament#poll tournament#animal tournament#biology#cnidaria#bryozoa#chordata#arthropod#echinoderm#molluscs

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reino: Animalia (Linnaeus, 1.758)

Super-filo: Vendobionta (Seilacher, 1.992)

Faixa Temporal: Ediacarano até Cambriano médio.

Idade: 570 - 513 Ma.

Vendobionta é um superfilo extinto que inclui os filos dos organismos da Biota Ediacarana. Vendobionta é um grande grupo de metazoários pré-cambrianos.

A fauna do Ediacarano devia previamente conter apenas animais (multicelulares) como ancestrais para diferentes grupos de invertebrados. Por causa dos tamanhos dos fósseis, segmentação, simetria bilateral e polaridade, todos os fósseis do Ediacarano foram originalmente atribuídos aos cnidários (como plumas-do-mar e águas-vivas), vermes anelídeos e artrópodes. Porém, uma nova interpretação surgiu a favor dos fósseis do Ediacarano, apontando incongruências funcionais que indicaram que os fósseis não estavam relacionados aos grupos citados anteriormente. Charniodiscus, um exemplo, lembra modernas plumas-do-mar em forma e coordenação, mas como ele é um fronde, e tem uma folha fechada, ele foi interpretado como um organismo filtrador. Similarmente, Dickinsonia poderia ser comparada a um verme segmentado. Porém sua forma de panqueca não permitia nem os modos sinuosos nem os peristálticos de locomoção característicos dos vermes. Nem a forma superficialmente parecida com trilobita de Spriggina indica uma relação, pois, ao contrário das trilobitas, Spriggina não tinha carapaça. Outros Vendobiontes lembram nada tanto quanto as folhas das plantas terrestres atuais.

Inclui os seguintes filos:

†Petalonamae?

†Proarticulata

†Trilobozoa?

†Medusoids?

#vendobionta #animalia #ciênciacidadã #divulgaçãocientífica

1 note

·

View note

Photo

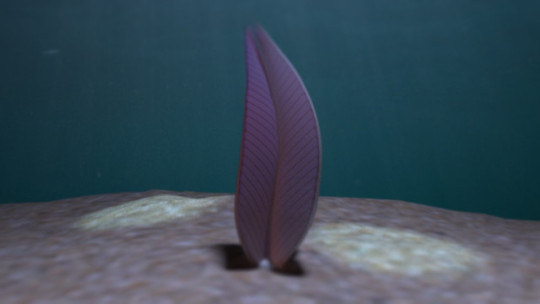

Cambrian Explosion Month #04: Phylum Ctenophora (And Petalonamae?)

Much like the sponges, the ctenophores (commonly known as "comb jellies"), are one of the oldest animal lineages, but their exact position in the evolutionary family tree is a little uncertain. Traditionally they're placed between sponges and all other animals, as the earliest branch of the eumetazoans, but some studies have suggested that they might be much more ancient, possibly branching off before even the sponges did.

And while their fossil record is poor due to their soft gelatinous bodies, some of what we do have is starting to hint that their ancestry was very different from their modern jellyfish-like representatives – and they might even have links to some weird Precambrian creatures.

At first glance Stromatoveris psygmoglena from the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago) doesn't even look like a ctenophore, instead more closely resembling a sea pen or one of the frond-like Ediacaran organisms. Up to 10.5cm tall (~4"), it was a sessile animal that lived attached by a holdfast to the sea floor, with up to four branched "petaloid" fronds that would have been used to catch food particles in the surrounding water.

It's been interpreted as a comb jelly relative based on the possible presence of cilia on its fronds, suggesting that the group may have originated as sedentary suspension feeders and later evolved a free-swimming mode of life. Along with the discovery of other fossils that might be sessile ctenophores, and a lineage of swimming forms with spiny skeletons, it's definitely seeming that the early evolution of this group was much stranger than expected.

However, Stromatoveris also might not be a comb jelly at all, and instead might really be a Cambrian representative of the fronded Ediacaran animals it so closely resembled. More recent studies of additional fossils suggest that it was part of a group of early animals called petalonamids, closely related to the weird fractal-branching rangeomorphs.

…But, of course, there's always the possibility that both relationships are correct, and that the Ediacaran frond animals were actually early ctenophores – an idea originally proposed back in the early 2000s, before Stromatoveris had even been discovered.

———

Other Cambrian ctenophores were much more recognizable, but also had much larger numbers of comb rows on their bodies.

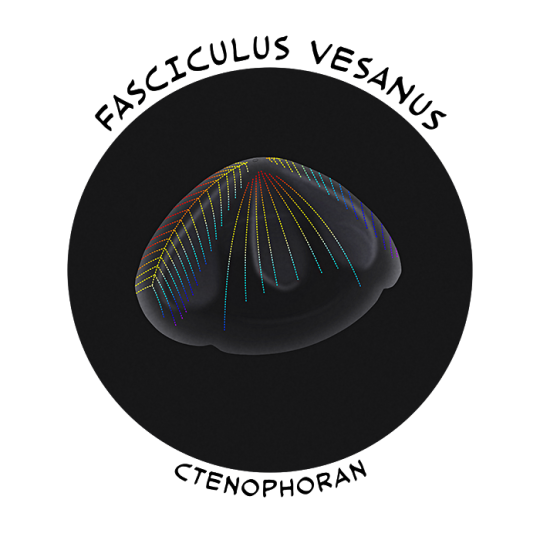

Fasciculus vesanus had one of the oddest arrangements, with two sets of long and short rows totalling 64 compared to modern ctenophores' 8. Known from the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago), it measured about 11cm in diameter (4.3") and was either a very rare member of the ecosystem or just very rarely fossilized, with only a single specimen ever found.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian#ctenophore#comb jelly#eumetazoa#animalia#stromatoveris#petalonamae#rangeomorph#fasciculus#art

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ediacaran weirdos, AKA Pancake Pals

This week’s post is a slight digression from our ongoing series about animal diversity, because it features a group of mysterious fossils that may not even be animals!

I hope you’re in the mood for pancakes.

(Image: A reconstruction of an underwater Ediacaran environment, prominently featuring Dickinsonia and several Charnia along with other ediacaran weirdos. [Source])

In order to understand these weirdos, we’re going to have to take a trip way, way, back. Back before the dinosaurs, or before the first land animals, or before the first fish, or even before they started making sliced bread. A time called the Ediacaran period, when life was good, sediments stayed where they ought to be without nasty creatures crawling about in them, and pancakes roamed the seas looking for a meal.

Many of you are probably familiar with the Cambrian Explosion, which occurred about 530-540 million years ago in the Cambrian period and records the appearance of hard-bodied animal groups in the fossil record. This event really deserves its own post, or series of posts, but it’s important to remember that this event is not placed at the actual first appearance of these organisms, but rather their first appearance in the fossil record. It’s got to do with hard body parts being hip and trendy in the mid-Cambrian, and thus a bunch of animal groups all suddenly seeming to appear at once.

Key word, seeming. These animal groups all had to come from somewhere. Many groups appear in the fossil record around the same time in the Cambrian, fully formed, and so their ancestors must have lived previously. These ancestors just didn’t have very hard body parts, so we don’t easily find fossils of them. (There are several proposed reasons why animals all suddenly started making hard parts at the same time, but I won’t go into it here.)

(Image: A bunch of Cambrian animals, including trilobites, Wiwaxia, and early chordates. [Source])

We’re currently living in the Phanerozoic Eon, or the age of visible life. In fact pretty much every fossil organism you can think of, from Australopithecus to T. rex to trilobites to trees, has lived in the Phanerozoic. It started 542 million years ago with the Cambrian period, just before the Cambrian Explosion, and it’s marked by the first appearance of the burrows of priapulids, AKA Penis Worms. Yes, we live in the eon of the penis worm, but what’s more important is that these burrows are maybe the earliest examples of any life form actually digging into the sediment and mixing it up, a process called bioturbation.

Prior to the Cambrian, there are practically no examples of any creatures bioturbating the sediment*, which means it was pretty much fair game for microbes to go hog wild. Because nothing could get to them.

*Okay, there are some examples. But these burrows all seem to be very simple, not very deep, and pretty much just up-and-down. Not much wriggling around going on.

This formed a unique type of sediments called microbial mats or microbially-bound sediments, in which the sediments are bound together into a sort of carpet that’s resistant to being disturbed. This sets the stage for preservation of very soft-bodied creatures, and what’s more, they’re being preserved in sand rather than in much finer-grained deposits that are usually the only things that can preserve any fine details. It’s a type of preservation that’s almost unheard of in the phanerozoic.

So, with that in mind, let’s imagine ourselves in the Ediacaran! The world has just stopped being an ice planet, and you are a horrible little rangeomorph.

What’s a rangeomorph?

Good question!

Just kidding. That’s not the end of the post, but it might as well be, because the answer to “what are these ediacaran weirdos” is “we just don’t know”. They don’t really clearly resemble any living animals.

(Image: a fossil of Dickinsonia. It’s approximately oval-shaped, and looks quilted. [Source])

Like, we really don’t know. The closest we have to knowing is that some bio-geo-chemical data has indicated preservation of fossil cholesterols, which narrows it down to “they are animals, or fungi, or something that’s a close relative of animals and fungi”. They’ve been suggested to be sponges, or cnidarians (jellyfish and friends), or bilaterians, or even giant placozoans, or a TON of other things. My personal favourite idea is that they’re giant single-celled organisms similar to modern monothalameans, and that they’re not animals or fungi but rather their own little group (Many of these quilted weirdos have been grouped together in a group called petalonamae, which is sometimes called vendozoa; they’re pretttty much the same thing).

So, without further ado, here’s a little who’s-who of some of the more well-known ediacaran weirdos! I’ve already shown you Dickinsonia, the classic little pancake whom we all love. Like many of these vendozoans, it comes from Australia. The very largest get up to 1.4m long! More typically, though, they’re on the order of a few centimetres. Sometimes they’re very long, but they’re never very thick, and they have a weird “quilted” appearance.

(Image: Glide symmetry in a fossil of Charnia and in cartoon leaves.)

Although Dickinsonia appears to be symmetrical at first glance, that’s not quite true. Rather than being truly symmetrical, it has what’s called glide symmetry—i.e. the body segments are mirrored and then moved forward a little, so it’s not precisely symmetrical. This is pretty common for vendozoans.

(Image: A group of Charnia, frond-like quilted organisms that stand up, looking a bit like feathers. Image by Nobu Tamura [Source])

Another significant group of ediacaran weirdos are the rangeomorphs, of which the most famous is Charnia. It maintains the quilted appearance of Dickinsonia, but stands straight up, with a sort of anchor-point holding it to the ground. Charnia fronds are typically about 10-20cm long, but some specimens that are over 2m long have been reported.

(Image: Swartpuntia, a rangeomorph that looks like three Charnia clipped through each other badly. Image by @alphynix—go follow them if you’re not already, they do great art!)

Other rangeomorphs, like Swartpuntia, have between three and six-fold symmetry, and so look more like a lemon-juicer. It also has a name that’s very fun to say.

Swartpuntia and other rangeomorphs are pretty significant in that they represent possibly the earliest tiered ecosystems of non-microscoping life forms! While things like Dickinsonia were crawling around on the ground, rangeomorphs were taking advantage of different resources by growing tall and frondy.

(Image: A fossil of Spriggina, a flattened, elongate, vaguely phallic impression fossil. [Source])

There’s also Spriggina, which—surprise!—has been a source of debate as to what it is. It’s variously been proposed to be a worm, a trilobite relative, or a vendozoan. It has glide symmetry, though, so I’m grouping it with vendozoans here.

One thing all these vendozoans have in common, besides glide symmetry and being impressions on rocks, is that there’s very little apparent internal structure. Whether this is solely an artefact of preservation is up for debate, but there is not clearly a mouth, or gut cavity, or reproductive organs, or anything like that. It’s assumed they fed by osmosis, either by moving along the seafloor feeding on microbes in the sediment (if they were flat like Dickinsonia), or by consuming floating microbes (if they were frondy, like Charnia). It’s also assumed they reproduced asexually via fission or budding.

Whatever the vendozoans were, their time was not short lived. Between the first and last of these ediacaran weirdos, almost 70 million years passed. That’s more time than between us and T. rex! During that time they survived an ice age, but they didn’t survive the start of the Cambrian. No definite vendozoan fossils are known from the phanerozoic, and it’s pretty widely thought that the start of more intense bioturbation probably destroyed the microbial mats they relied on. So these days we have to make our own pancakes.

510 notes

·

View notes

Link

An article published in the journal "Paleontology" describes a comparative study of various organisms of the so-called Ediacara fauna with the one called Stromatoveris psygmoglena. Jennifer F. Hoyal Cuthill of the Tokyo Institute of Technology and the British University of Cambridge and Jian Han of the Northwest University in Xi'an, China, analyzed more than 200 fossils of specimens of this organism that lived about 518 million years ago. A comparison with other organisms that lived later suggests that they were all animals that formed their own group, which was called Petalonamae.

0 notes

Link

Un articolo pubblicato sulla rivista "Paleontology" descrive uno studio comparato di vari organismi della cosiddetta fauna di Ediacara con quello chiamato Stromatoveris psygmoglena. Jennifer F. Hoyal Cuthill del Tokyo Institute of Technology e dell'Università britannica di Cambridge e Jian Han della Northwest University di Xi'an, in Cina, hanno analizzato oltre 200 fossili di esemplari di questa specie risalenti a circa 518 milioni di anni fa. Un confronto con altri organismi che vissero più tardi suggeriscono che fossero tutti animali che formavano un loro gruppo, che è stato chiamato Petalonamae.

0 notes