#Myriam Mézières

Text

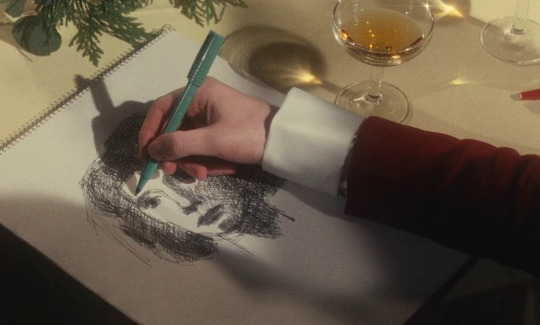

Paul Vecchiali - Don't Change Hands (1975)

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

change pas de main (fr, vecchiali 75)

#change pas de main#paul vecchiali#myriam mézières#nanette corey#liza braconnier#claudine beccarie#georges strouvé

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fleurs de sang [Flowers of Blood] (Alain Tanner / Myriam Mézières, 2002)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Retrato de mujer con hombre al fondo (Manane Rodríguez, 1997)

Mi descubrimiento de Manane Rodríguez se produjo a raíz de este su primer largometraje, rodado ya en España en Super 16mm (ampliados a 35 para posibilitar su exhibición), escrito con su pareja, el también director Xavier Bermúdez (y con la colaboración de Antonio Larreta, otro exiliado afincado aquí), y con una magnífica actriz chilena, Paulina Gálvez (inexplicable y lamentablemente desaprovechada por los demás cineastas), que interpreta la mujer del título.

Título, por cierto, que aun siendo atractivo y pese a no faltar a la verdad (es también eso) minimiza o subestima el alcance real de la película, y que debió ser lo mismo pero con todo en plurales, ya que, elípticamente, sin retórica ni pesadez, en certeros esbozos que permiten deducir o adivinar el resto, nos ofrece los retratos, más o menos centrados y detallados, de no menos de cinco mujeres (y un apunte de otra más, brevísimo pero muy divertido y revelador) y tres hombres muy al fondo (sin contar dos niños de no muy promisorios auspicios de futuro).

Fue para mí la revelación de no menos de tres talentos (Manane, Xavier y Paulina), sin contar el esperanzador encuentro de dos productores que entonces se atrevían a correr riesgos (Juan Pulgar y Rafael Álvarez), un director de fotografía notable (Juan Carlos Gómez) y un músico aún no muy conocido (Jorge Drexler), cuya perezosa partitura no subrayante sienta como un guante a la película en su conjunto, modesta, tranquila y nada altisonante.

Muchos años han pasado desde entonces, y Manane ha hecho algunas (no muchas, desgraciadamente, quizá demasiado pocas) películas más, cortas y largas, de encargo unas y de iniciativa propia otras, todas buenas e incluso aún mejores y más emocionantes, más cruciales, más difíciles (de hacer, no de ver ni de entender), con tremendos dilemas morales casi siempre, como Migas de pan y, sobre todo, Los pasos perdidos, pero yo le tengo un afecto especial a este Retrato de mujer con hombre al fondo, que he seguido volviendo a ver varias veces en el curso de los años, y que siempre reencuentro fresca, original y distinta de casi todo. No es tan frecuente, y es un momento feliz para un aficionado al cine, que uno intuya en una primera película la aparición de un verdadero cineasta, y encima uno que con modestia y atención mira con la cámara para comprender mejor, sin efectismos ni pretensiones desaforadas, sin tratar a todo trance (y a cualquier precio, claro) de llamar la atención y de proclamar (más que demostrar) lo «original», lo «radical» y lo «rompedor» que es.

Como a mí no me interesa que haya muchos directores, sino más bien que lo sean de verdad (y no impostores) y además sean buenos, no tengo el menor empeño en que las mujeres —así, en masa— dirijan más películas, sino que desearía que más mujeres que lo deseen hagan buenas películas y las que ya dirigen las hagan mejores.

Es cierto, por lo demás, y lo encuentro normal, que igual que no todos los hombres somos iguales, las mujeres son muy variadas, y no caben las generalizaciones excesivas, y no creo adecuado tratarlas como un colectivo, sino como individualidades libres e independientes. Eso no impide que a menudo aunque no siempre, a algunas mujeres les interesen más que a muchos hombres ciertas cosas, actitudes o actividades, y que las miren de otra manera, y en cambio presten menos atención que buena parte de los hombres a otros aspectos de la vida, la sociedad... o las familias. Digo esto porque no me interesó esta película, en principio, ni antes de verla ni después, por tratarse de un film realizado por una mujer, aunque, desde luego, de no haberlo sabido de antemano, como si no la hubiera visto con títulos de crédito, a partir de algunos detalles habría sospechado que su autora cinematográfica principal era una mujer, y no sólo eso, sino además sensible, inteligente, con «buen ojo», con sentido del ritmo, con claridad y concisión narrativa, con humor, con buen oído para los diálogos —cosa excepcional y llamativa en el cine y la televisión españoles, ¡aquí no suenan falsos ni impostados!—, y con habilidad y finura notables como directora de actores de ambos sexos, aunque yo encuentre sistemáticamente mejores a las actrices... y también más interesantes los personajes que les ha tocado encarnar.

Aclaro que este último aspecto no lo considero un defecto o una limitación imputable a un supuesto «partidismo» de la directora (que a veces existe en otras cineastas, en ocasiones hasta llegar a extremos escandalosos de misandria, heterofobia o misogamia), sino a una sensación subjetiva mía general, y es que encuentro más interesantes, como promedio y casi siempre, a las mujeres, y que en casi cada pareja me parece ella superior al hombre, lo que ocasiona a veces, desde mi punto de vista, un notable desequilibrio que, si no se lleva con paciencia y humor por ambas partes, quizá explique algunos problemas de la vida real, que creo que el primer largo de la entonces aún joven pero ya madura directora capta y señala con bastante tino y sin homogeneizar: los tres hombres de la película tampoco son iguales entre sí, no representan los mismos problemas o inconvenientes, y ninguno es realmente un canalla, si bien ninguno parece muy divertido y sí, en contrapartida, diría yo que singularmente carentes, los tres, del menor sentido del humor. Se toman tan en serio y parecen tan satisfechos de sí mismos que no les queda hueco para nadie más y tienden a tomarse todo como ofensas personales.

Como crónica de una serie de días —que de ser más teme uno que no fuesen demasiado diferentes— de la vida cotidiana de la protagonista, Cristina de León (Paulina Gálvez), una joven soltera e independiente, pero no muy amante de la soledad, abogada especializada en divorcios en el bufete del que es socia con Joaquín (Pedro Miguel Martínez), y al parecer con cierta holgura económica, Retrato de mujer con hombre al fondo nos va poniendo en contacto con los restantes personajes de su entorno, según se relacionan con ella, por unas razones u otras, unas veces por iniciativa de ellos y otras de Cristina: alguno arraigado aunque distanciado como la ex-pintora Marisa (Myriam Mézières), casada con el nada sensible Joaquín y completamente deprimida y alcoholizada, que es el personaje más trágico y sin salidas de la película; otros más accidentales, como la muy joven secretaria-recepcionista del despacho (Begoña Hernando); otros recién conocidos, como un nuevo amante, que Cristina ha conocido como Alfredo (Bruno Squarcia) en un fin de semana en la playa y que resulta ser Diego Garrido, el marido del que está divorciando a una clienta no muy convencida de querer separarse, Ana Portolés (Cristina Collado, que en sus varias pero breves apariciones pinta de su personaje dubitativo y tenso un retrato muy completo); otro amante (como todos los demás hombres de la película, casado e insatisfecho), Andrés (Ginés García Millán), al que Cristina parece arrastrar ocasionalmente consigo sin mucho entusiasmo ni grandes esperanzas de futuro desde hace tiempo.

Aunque no puede decirse que Cristina tenga mucha suerte con los hombres, pese a ser ella muy atractiva y tener talento como abogada, ironía y bastante personalidad y fuerza de voluntad, lo cierto es que conserva aún un notable sentido del humor, aunque también cabe preguntarse con cierta preocupación (cosa que la película no hace) si lo retendrá cuando tenga diez o quince años más.

Hay que destacar que la película se mueve fuera de cualquier territorio genérico convencional. Reforzando o subrayando las cosas más agradables, podría haberse convertido en una novelita rosa; exagerando un poco los personajes y acelerando el ritmo narrativo, pudo ser una especie de «comedia alocada» (y da la sensación de que la directora habría podido movilizar en ese registro a sus actores); cargando las tintas y dramatizando las frustraciones, las soledades, las rupturas, pudo convertirse en un desolador melodrama.

No creo que las cosas vayan tan deprisa, en el fondo, como a veces parece en la superficie y en algunos aspectos que, ciertamente, han cambiado mucho en los 22 años transcurridos desde que se escribió y filmó esta película, en su momento no sólo contemporánea sino con las antenas de detección de lo que empieza a suceder o se anuncia a corto plazo muy bien puestas.

Nos choca hoy ver gente con teléfonos inalámbricos en su casa pero todavía ni un sólo móvil, con ordenadores pero sin mucho empleo de internet, fumando casi todo el mundo y todo el rato en todas partes, en lugares hoy prohibidos, elementos a los que nos hemos acostumbrado tanto que olvidamos que su introducción o desaparición es todavía relativamente muy reciente.

Es decir, se trata de una película muy datada, que quien la vea hoy notará que es ya «antigua» (más vale con el cine usar ese adjetivo que el más negativo de «vieja»), pero que es, en casi todo lo fundamental, como cine y como observación sociológica, todavía vigente.

Porque, igual que no quiso, creo yo, hacer un film de tesis ni una apología de nada ni de ninguna postura, Manane Rodríguez tampoco pretendía crear una especie de testimonio radiográfico de un sector muy determinado (los profesionales acomodados) de la sociedad madrileña de finales de siglo, sino que parece esforzarse por mantenerse en un difícil equilibrio estable en tierra de nadie, sin juzgar. Un poco como Roberto Rossellini en los primeros años de la década de los 50 o como Eric Rohmer en las décadas siguientes del pasado siglo XX.

Miguel Marías

Libro "Manane Rodríguez, voz en libertad", Antonio Peláez Barceló (Éride Ediciones, 2018)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

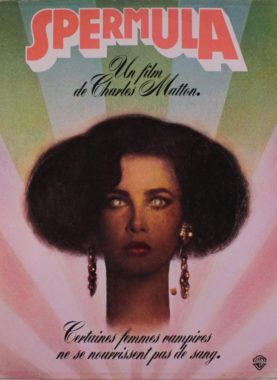

“Spermula” de Charles Matton (1976) avec Dayle Haddon, Udo Kier, François Dunoyer, Jocelyne Boisseau, Ginette Leclerc, Myriam Mézières et la participation de Nino Ferrer, dans le cadre de la rétrospective “Vampires, de Dracula à Buffy” à la Cinémathèque, octobre 2019.

#films#vampires#fairies#Matton#Haddon#Kier#Dunoyer#Boisseau#Leclerc#Mezieres#Ferrer#CinemathequeFrançaise

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

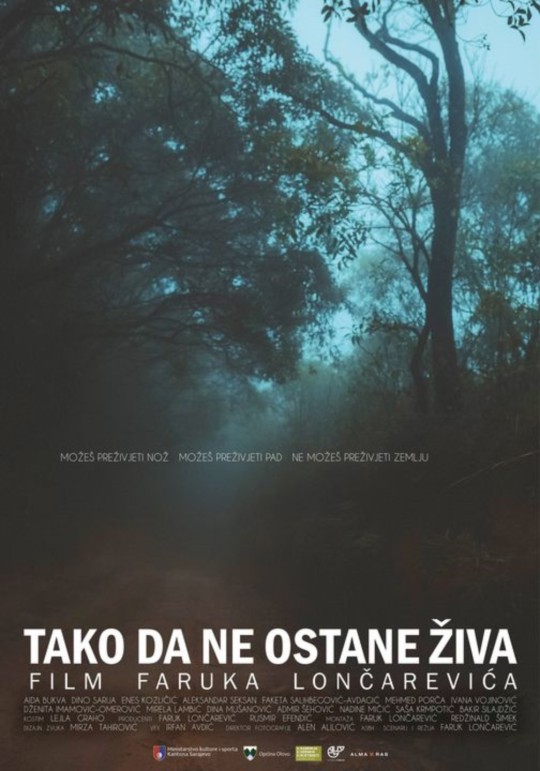

"Tako da ne ostane ziva"

“Tako da ne ostane ziva”

Pise: Dzana Mujadzic

Slika drustva

Medjunarodni ziri 36 izdanja Festivala de Valencia/Cinema Mediterrani, cija je predsjednica bila francuska scenaristica i glumica Myriam Mézières, dodijelio je Zlatnu palmu pobjedniku manifestacije, sarajevskom reditelju i profesoru Akademije Scenskih Umjetnosti, Faruku Loncarevicu. Cineast je dobio i novcanu nagradu od 25 000 eura. Zanimljivo je da je…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: John Berger and Alain Tanner’s Films About Life After Political Failure

Madeline (Myriam Mézières) and Max (Jean-Luc Bideau) in Alain Tanner’s Jonah Who Will Be 25 In the Year 2000 (Citel Films release)

John Berger did not think of himself as a critic. When mentioned during interviews he often disputed the claim, countering with his own preferred expression: he was a storyteller. This was true in some very obvious ways. For the most part, Berger had stopped regularly reviewing exhibitions around 1959, following a stint as a critic for the New Statesman, and his work over the next five-plus decades would take many different forms: both novels and short fiction, poems, plays, television documentaries, feature films, essays, and image-text collaborations. But his rejection of the distinction went deeper, and was connected to crucial changes he had made in his life. In 1973 Berger moved to the French Alpine town of Quincy, where he lived until his death earlier this year. Following the writing of The Seventh Man, a collaboration with the photographer Jean Mohr on migrant workers being forced into the industrial centers of Western Europe, he felt he was too detached from peasant lives to continue writing about them. So he went to live among them.

Berger wasn’t simply a writer dropping in from nowhere, getting what he needed and retreating. Many years later, he would frame his move to Quincy as a calling and relate it back to his formulation as a storyteller. “I feel as if I belong here, if I belong anywhere,” he told an interviewer from the New York Times. “And I don’t miss the city, certainly not the social life. I mean, for fun in the city, people get together at a party and swap opinions. Opinions. Here, when people relax, get together, they drink, play cards and sing—sit in a room and sing. And of course, they tell stories.”

This attraction to the primacy of storytelling is what eventually led Berger to the Swiss filmmaker Alain Tanner. Berger wrote a review for Sight & Sound magazine about Tanner’s film Nice Time (1957), which documents an entire evening in Piccadilly Circus, and was introduced to Tanner soon after by the filmmaker Lindsay Anderson, a mutual friend. Coming from different backgrounds, Tanner and Berger found a connection in their increased politicization and need to break from standard modes of making work. The two stayed in touch and eventually collaborated on a number of projects, most notably a series of three films — La Salamandre (1971), Middle of the World (1974), and Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000 (1976) — that melancholically reflect on the perceived failures of radical struggle, and the glimmer of hope in the distance of the future. The loose trilogy, along with other works by Tanner, will screen at Metrograph in New York beginning July 12.

As political films, the collaborations between Berger and Tanner are immediately distinguishable from what other artists were making in the aftermath of 1968. In an interview surmising his work with Tanner, Berger used Jean-Luc Godard as a counterpoint and returned to his idea of storytelling. “My own formulation about Godard is that he is the great film critic of our time, but, unlike most film critics, instead of writing his criticism in words, he makes films which are criticism of film,” Berger told an interviewer from Cineaste Magazine in 1980. “Alain, on the other hand, is essentially a storyteller — it’s a different function.” What this meant was that politics in the films they made together were not always direct. While Godard’s work became increasingly confrontational and dogmatic, Berger and Tanner’s critiques of society were buried in humanistic narratives that, as the critic Dave Kehr wrote, brought “thinking and caring together again.”

Rosemonde (Bulle Ogier) in Alain Tanner’s La Salamandre (CAB Productions SA release)

The most fruitful way to think about the Berger and Tanner collaborations is to see them as a continual sketch, with each film building on the last. The two would write the scripts together, often starting from a simple prompt and expanding from there, with Berger removing himself from the filming process and only coming back during the editing. La Salamandre (1971), the first feature they made together (Berger had contributed narration to a short documentary about Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh in 1965), is the loosest of their films, concerning two writers — one a journalist (Jean-Luc Bideau), the other a novelist (Jacques Denis) — who come together to script a television program based on the purported attempt by a local working-class woman, Rosemonde (Bulle Ogier), to murder her uncle. Rosemonde is the first of Berger and Tanner’s female outsiders, floating from job to job in rebellion against a world that only views her as a worker or a sex object. The more the two writers attempt to figure her out, the more she rejects their naive characterizations. “I’m not quite normal,” she tells one of the writers during an interview session for their project. “At least that’s what people say.”

But for Berger and Tanner, Rosemonde’s transformation was the epitome of post-1968 freedom. And she became the model for the characters of their future films, many of who are female. Alienated from collective struggle and finding themselves in a time of political stasis, they find politics in their small disruptions to bourgeois society and in relation to forces of control. In Middle of the World, Berger and Tanner’s second collaboration, an opening narration calls this moment, where disillusionment marked a turn toward apoliticism, a period of “normalization,” where hopes remain but are subsumed. “Only words, dates, and seasons change,” an unidentified female says. “Nothing else.” This is seen through the story of Adriana (Olimpia Carlisi), an Italian waitress working in a rural area of Switzerland. At the café where she serves drinks, she fends off the creeping hands of men playing cards and is told by an older waitress to stay away from any political discussion because “politics and business never mix.” Soon, she begins an affair with Paul (Philippe Léotard), a local politician who is married.

Adriana (Olimpia Carlisi) and Paul (Philippe Léotard) in Alain Tanner’s Middle of the World (CAB Productions SA release)

Like with Rosemonde, Berger and Tanner present Adriana’s story as one of self-realization. As her relationship with Paul progresses, it becomes clear that her future is being prepared for her without her consent. It is everything a woman of her means is supposed to expect: a good-natured man, marriage, a home. Paul plans to divorce his wife, putting his political career at risk, to start another life that mirrors the previous one. But Adriana is not trapped. She refuses the only future that Paul can see for them, to be consumed by Paul’s need for a life of middle-class convenience and comfortability — he tries to woo her at one point by listing the appliances he has in his home — keeps her possibilities alive. She has a choice, and makes one.

The three features Berger and Tanner made together are essentially films about class. Characters are struggling to live life after political failure, finding ways to resume their resistance to a value system that remains ever-present and crushing. Berger, as a writer and as a human being — the two were never truly separated — was engaged in a similar process. His work became increasingly focused on the poor and working class following his move to Quincy, and he was searching for a form to match his subjects. This resulted in the simplified prose and traditional narratives of the Into Their Labours trilogy, a series of novels he completed following the end of his collaboration with Tanner. According to Berger, Tanner at the time was moving in the opposite direction. He wanted to make films with a “looser structure” that were “more experimental in their narrative.” The tension between their divergent positions resulted in their final film, and certainly the most well known of their collaborations, Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000.

The most explicitly political of the work Berger and Tanner made together, Jonah tells the story of a group of former radicals: one has become a teacher (Jacques Denis), bringing radical ideas into a rural classroom; another (Rufus) finds work on farm while his wife (Myriam Boyer) hopes to bring another child into the world; the owners of the farm (Dominique Labourier, Roger Jendly) sell chemical-free produce at the local farmer’s market; a former journalist now working as a proofreader (Jean-Luc Bideau) subverts land speculators in his spare time and meets a woman (Myriam Mézières) who finds radical potential in tantric sex; a young woman (Miou-Miou), working as a cashier, gives discounts to the elderly and other people in need. The film is built around long takes and evolving conversations between the group, and uses dream-like sequences, newsreel footage, and occasional off-screen narration that breaks into the realist narrative.

Marco (Jacques Dennis) and Marie (Miou-Miou) in Alain Tanner’s Jonah Who Will Be 25 In the Year 2000 (Citel Films release)

These characters come together, forming something like a collective living space, and find that they can keep hope alive through their small actions. But can these actions bring about change? It’s the question that is at the heart of Jonah, and one that the film answers with a sense of political optimism. As the conventional world puts pressure on the characters to give up their radical dreams, the future is contained in a young child named Jonah. A central image of the film is a mural, painted on a stone wall at the farm and depicting many of the characters. Their image and their values are marked in history, positioned like idols. But as time passes, the mural starts to fade. One of the final things we see in the films is the young Jonah scribbling over these former student radicals with chalk. How you see this ultimately depends on your cynicism, perhaps. You can look at this as Jonah erasing the past, and see a bleak future where the child comes to represent all that his parents and their friends rejected. Or you can view this as Jonah presenting a new way forward, to advocate, as the writer Geoff Dyer once said of Berger’s writing, for a way to “redraw the maps.” When one flame dies, another starts to burn.

John Berger and Alain Tanner’s La Salamandre, Middle of the World, and Jonah Who Will Be 25 In the Year 2000 are screening at Metrograph (7 Ludlow St, Lower East Side, Manhattan) July 12–July 19.

The post John Berger and Alain Tanner’s Films About Life After Political Failure appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2tbb67S

via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alain Tanner Retrospective at the Metrograph

Alain Tanner Retrospective at the Metrograph

Photo

Myriam Mézières and Jean-Luc Bideau in Alain Tanner’s “Jonah Who Will Be 25 in the Year 2000.” Credit Citel Films

With the opening of several new repertory screens in New York City comes a welcome bonus: retrospectives of foreign filmmakers whose work animated the city’s film culture decades ago. This past spring, the Quad Cinema hosted a revival of the Italian political and sexual…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

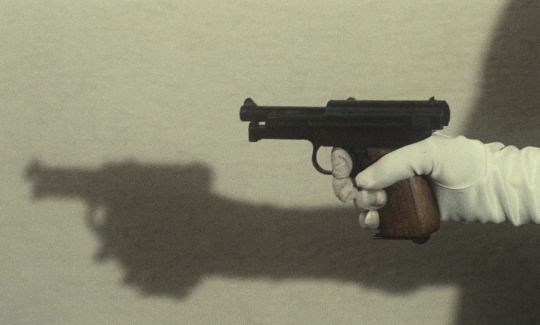

Paul Vecchiali - Don't Change Hands (1975)

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

jonas qui aura 25 ans en l’an 2000 (sw/fr, tanner 76)

#jonas qui aura 25 ans en l’an 2000#jonah who will be 25 in the year 2000#alain tanner#john berger#jean-luc bideau#myriam boyer#Myriam Mézières#renato berta

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Spermula” de Charles Matton (1976) avec Dayle Haddon, Udo Kier, François Dunoyer, Jocelyne Boisseau, Ginette Leclerc, Myriam Mézières et la participation de Nino Ferrer, dans le cadre de la rétrospective “Vampires, de Dracula à Buffy” à la Cinémathèque, octobre 2019.

0 notes

Photo

Myriam Mézières & Azize Kabouche

Une flamme dans mon coeur, Alain Tanner, 1987

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Change pas de main (Don't Change Hands). Paul Vecchiali. 1975. France.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Vecchiali - Don't Change Hands (1975)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Vecchiali - Don't Change Hands (1975)

#film#paul vecchiali#don't change hands#Change pas de main#Myriam Mézières#Hélène Surgère#marlene dietrich#1975

19 notes

·

View notes