#My interpretation of the general iconography is probably very off so take it purely as an aesthetic pursuit lol

Text

An angel. Alchemy treaty Aurora Consurgens, 1420-1450

#medieval redraw#alchemy#angel#manuscript illumination#My interpretation of the general iconography is probably very off so take it purely as an aesthetic pursuit lol#all of this is alchemical allegory#i recommend looking up the other weirdo miniatures from this manuscript it slaps

17K notes

·

View notes

Photo

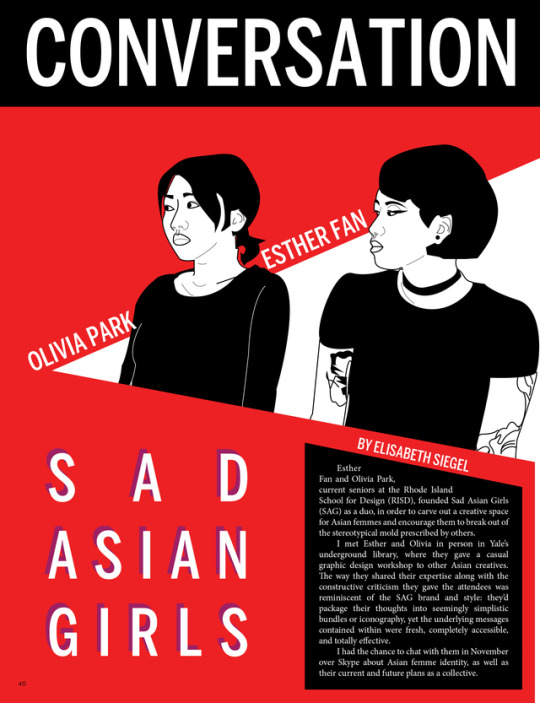

Conversation with Sad Asian Girls (formerly Esther Fan & Olivia Park)

As Fan and Park, known collectively as Sad Asian Girls, announced the dissolution of their partnership about two months ago, we decided to post the interview that Sine Theta magazine’s art director Elisabeth Siegel conducted with the duo last November in full as a fun retrospective and tribute to their amazing work. The interview is available in print form in Sine Theta Issue 3: “LIGHT 阴.” We at Sine Theta are excited for what’s to come for Fan and Park!

Esther Fan and Olivia Park, current seniors at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in the U.S., founded Sad Asian Girls (SAG) as a duo, in order to carve out a creative space for Asian femmes, and to encourage them to create content and break out of the stereotypical mold prescribed by other non-Asians or non-femmes.

I met Esther and Olivia in person for the first time deep in Yale’s underground library, where they gave a casual graphic design workshop. While at Yale, they also participated in a conversation about being Asian femme creators at the Asian American Cultural Center (AACC). The way they shared their expertise along with the constructive criticism they gave attendees was reminiscent of the SAG brand and style: they’d package their thoughts into seemingly simplistic bundles or iconography, yet the underlying messages contained within were fresh, completely accessible, and totally effective.

I had the chance to chat with them over Skype and pick their brain about Asian femme identity, as well as their current and future plans as a collective.

Elisabeth Siegel: So just to start out, how did you two meet? How did SAG get started?

Olivia Park: We met essentially through classes, and then while working together on non-SAG related projects, we noticed similarities regarding our identities, and through that we decided to make work related to the Asian femme experience.

Esther Fan: We both realized that we both seemed to be the few students in our department interested in social issues or making work about it, and also the first time we collaborated it was about millennial culture, and then we moved on to things more specific to ourselves.

ES: So, the “Asian femme experience” — could you talk more about what you define that as, and what you find unique to the Asian femme identity versus Asians in general?

EF: I think at the moment there is a lot of talk about feminism and the various experiences that women have in a mostly male dominated society. Once you add Asian to that label, the experience is narrowed down, yet the experience is still so common.

OP: One thing that is unique is invisibility of Asian presence, especially in media, and healthcare in general, specifically mental health awareness — almost everything. We’re kind of just not regarded. On the one hand, I understand, because we’re only 5% or 6% of the population [in America], but we still are part of the population, and we’re the fastest growing, so America just really needs to be aware at this point.

EF: I think the experience of an Asian femme is so specific because the expectations put on women in Asian culture is quite different from the western expectations of women. It’s still similar in the fact that we need to be secondary to men and things like that, and also it depends on each family. But for us, both of our parents were or are still Christian and conservative, and the kind of things that they try to teach us in how to be a perfect woman and be the perfect “wife-y package” contributed a lot to us trying to tell our stories about Asian femmes.

ES: I definitely know what you mean. When it comes to western versus eastern as a binary — even though I think calling it an absolute binary can be quite harmful — in general, the experience for women is very different.

As you know, Sine Theta is specifically by and for those experiencing the Sino diaspora. How does the more unique experience of being part of a diaspora shaped or informed your art, on an individual level or in your collaborated projects?

OP: There are so many moments where we have identity crises. It just becomes more and more important to find something to hold onto and identify with, and so things like food become a cultural recognition and almost an awakening, and conversations happen through those moments. The “Have You Eaten?” video was a lot about the conversations we would have [with our families], and a way to have that initiated was by eating the food of our motherland.

ES: I wanted to ask you guys about specifically the name “Sad Asian Girls.” I get the asian girls part, that’s pretty obvious. I was wondering if you could talk about the inspiration behind “sad” and why you settled on SAG.

EF: It really started off just as having to think of a name really quickly so we could make a YouTube account to upload the [“Have You Eaten?”] video. It was a parody of the “sad girls club” that happens on Tumblr, and it seemed natural. Over time, when we gained a following, it started to take on a meaning of its own. In a later video, we mentioned that the term “Sad” could refer to the frustrations of having to live with both our parents’ cultures and western cultures, and the type of identity crisis that usually comes with that. Now, we just kind of kept the term sad and Asian, for consistency, and it’s kind of created an identity of its own.

ES: What sort of identity would that be? Also, as for the “identity crisis,” do you think sadness is a part of what causes the crisis, or a result of it?

EF: Maybe both, but probably more so a result of it. We’re born into having to juggle between two different identities. I think when people hear SAG, it sounds something they can resonate with, usually more ironically than seriously.

OP: I also think the name has done a lot for us. You almost immediately get an idea of what we’re about. If we were called the “Asian Student Art Collective” that might just sound like we’re trying to foster a community of neutral art that could be even purely aesthetic. But SAG says something that signals oppression, something that signals hurt, and I think that’s where the root of our work comes from. It’s from the hurt. At the same time, if you look at our work, it’s about being proactive and storing that sadness into something positive.

ES: Sometimes within activism against oppression, it can be difficult to maintain a certain level of sadness or anger, because it gets tiring...I’ve experienced this in some activist circles, that as you move forward it can be harder and harder to maintain emotional momentum.

OP: So you’re asking, how do we feel motivated to do things despite sadness?

ES: That’s definitely part of it. And with “Sad” in your name, how is “sadness” maintained in your art? Does that ever get tiring?

OP: I think also that our visuals matter a lot. If we were to use a grungy filter with blue and green it might appear to be a little more soft, mellow, kind of like “Flickr-artsy.” But we intentionally use high contrast. We blow up our typography, we use bold reds. Our site is like 255 RGB red. We always use 255 because that’s the brightest red the computer’s got so we’re going to use it. We also changed our typeface to Noto, which is Google’s free typeface that can be translated into every language. These are all very intentional design choices that we’ve made and it’s loud and it’s clear and it’s sad. Some people have said that our visual language comes off as more angry than sad, but anger to me is a more intensified form of sadness. Anger is what results when you experience sadness with no resolution. I think it’s fitting.

EF: The thing is, being a marginalized group, and this goes for any marginalized group, things aren’t ever wholly resolved. We can make progress little by little, but there is always going to be something else that is making us “sad.” In terms of a resolution for sadness, simply use that sadness as a tool or a motivation for making, a fuel for making activist art. It sounds kind of pessimistic, but without sadness and without frustration and things like that, there wouldn’t be powerful art. The strongest pieces that work come from hardships. So to answer your question as best as I can, every project that we make is based on an existing issue in the world that makes us “sad.”

ES: This issue’s theme is “Light,” and we’re going with that as also talking about the Chinese concepts yin and yang, and the tons of meaning imbued in both yin and yang. Yin has various meanings, but some of the ones that we’re looking at also have to do with femininity, as well as passivity. You mentioned “Sad Asian Girls” was an ironic title you were giving yourselves — how do you go about subverting that title within self-application?

OP: First of all, I think no matter what people are going to interpret it wrong. Some people will. So it’s all about clarity. After repeating ourselves so many times in interviews, we only solidified our stance. At first, I don’t think we explained it well enough or enforced the idea. It’s good to start out strong and confidently and go with that and stand up for it, instead of starting weak and having to explain yourself and have to apologize over and over again, going back to changing your idea or your message. Know what you’re doing. Make it strong, make it unapologetic.

EF: I think transparency is also important. Most people who start out activist work are really excited or really angry and they want to make their content as fast as they can, sometimes without thinking how that’s going to happen or how that’s going to be successful. And I think that’s okay, you need to keep that fire going, but if you do make a mistake or decide that you want to go in a different direction, that has to be clear in your work too, and so that’s why in our presentations and things we’ve kind of discussed our successes and our failures, and why we took a break, things like that. Somebody in my class last night was talking about how a lot of the time when people want to be activists or go to protests or do something, they are really excited and they do too much and they go overboard and there ends up being consequences or it fails or their project doesn’t work, and then that discourages them from doing anything else ever again. But I think after you’re excited it’s important to step back and really think critically about how you’re going to move forward and how to make whatever impact you make last and not be impulsive.

ES: To step back and look more at SAG’s presence as a collective — your site in November said you were in the process of re-branding. What is that process like?

OP: Mostly using accessible typefaces, things that people can get for free. We were using Futura before, and a lot of that typeface some people won’t have, so we thought that everybody should be able to mimic Sad Asian Girls’ vernacular. So we’re basically making it easier for people to copy us and to share the same visuals.

EF: Also making it more legible. We cut down on a lot of text on the website and different sections where everything was displayed out on one page.

OP: We don’t want to look like you have to be an angry tattooed girl.

EF: And that’s why we added that dinky little sad face. It’s a cheeky way of holding onto the sad sentiment but in a way that is still bold. It implies that there’s more that you can do with it. [Rebranding] is more about making projects in the future with the same language. I think once we generate more content with the visual language as the same as our website, with our new logo, the new brand will be more solidified.

ES: What has been your favorite work that you worked on together for SAG?

OP: It’s definitely the next project. We always get super excited about the next project, because every time, we improve. Every project gives us more experience on what we like and what we don’t like, and how to work better or narrow down our process, or things like that. It’s kind of like how your favorite song is the last song you’ve heard.

EF: Nice analogy. Wow.

ES: You guys probably don’t want to spoil what it’s going to be…

OP: It’s probably going to be about the lack of visibility in galleries, which are white spaces. It’s a commentary more specific to the art field and scene. Since we’re both graphic designers and we’re both graduating soon, it’s kind of expected that we immerse into that field. Just seeing the lack of example, and also lack of invitation of femme identities makes us worried or concerned and so we’re kind of making a statement about that.

EF: Being in art school you definitely learn a lot about the art world, and how it’s programmed to benefit white male artists. Our entire curriculum is based on white male artists. The few times that there are female artists, it’s almost in a tokenizing way. Like how the Guerilla Girls did their thing about more women in museums, and last weekend we went to the MOMA just to look around, and they were selling Guerilla Girls’ merch for profit, but we aren’t seeing any more women in museums. Their work was there just for show, basically. I think this upcoming project focuses more on actually trying to inject the Asian femme identity into these faces that are mostly predominantly white, male and old.

ES: Right! One of the topics that I heard come out of the discussion at the Asian American Cultural Center while you were at Yale was the room full of silence whenever an artist makes a work concerning race. Could you elaborate on that?

EF: We talked about how another group in our school, called Black Artists and Designers, made a project called the Room of Silence, which is what happens when a student of color decides to make a project about their race, and the different dynamics that come with that. The room full of silence occurs because nobody else who isn’t a person of color knows how to critique it, out of fear of seeming racist or they’re just indifferent, or they just don’t think it applies to them.

OP: This was a video of several interviews of mostly black students, there was asian and latinx students in their too.

EF: It kind of went viral in our school, and some professors showed it to their students. Our professor showed it to us, and I feel like it was again just to show that they know that it exists, and to show that “I’m not like other professors.” They also attempted to have a conversation and at Yale we also talked about how when our class was shown the video, nobody still knew how to talk about it. Some people were falling asleep, some people didn’t watch the whole thing, and the professor said, “Are we done talking about it? Do you want to move on? Okay…,” and then Olivia got mad about it, and she said, “No, I think you need to force the students to talk about it. It’s such an important thing that’s happening in our school, and you can’t brush it off like a snazzy project.”

OP: And even Esther added on to that conversation, but that was kind of the end, though.

EF: The last thing I said about that was that I called out one white male student in our class who consistently makes average work, but the professors would always be into it, because his being a white male makes it seem like his work is conceptual and more than it really is. Other students whose English isn’t that great, or who have accents, the professors tend to skip over them because they subconsciously feel like people who have accents are less intelligent, and that’s what I talked about. Even though that video happened, and we also had a protest last year, the school has kind of gone back to the way it was, it kind of seen as those students of color just being angry again.

OP: I think that people do want to make change, but it’s an institution after all, and for an institution to work well while pleasing everyone that is in power right now, there’s not much change that can be done, except for maybe cultural attitudes. That’s what activists and artists are doing right now, to give a voice to who we are and what we want versus what is actually happening.

ES: Could each of you talk about what your favorite thing is when working with the other person?

OP: That’s a good question. Why don’t you go first? [Laughs.]

EF: There’s a lot of things I love, there’s a lot of things I hate. Let’s do that thing from Kindergarten where you say two compliments and one criticism. When we work together, we generate ideas in conversations at the same time, but usually Olivia comes up with better ideas for execution, or places we can go, or like forms that we can use. And then I’m the person who’s doing the tweaks and how to make things say something more clearly. I’m really picky about language, like I need every sentence to say exactly what it needs to say. But I think that’s fine. I think we make a good pair in that sense, where I have things I want to talk about, and sometimes I introduce them to Olivia, and then we sit down and we discuss ideas. We have really different aesthetic tastes, and sometimes we argue over that—

OP: And that’s over stupid stuff, like over whether to make one thing twenty percent desaturated or not. We will fight for a day and I’ll be like, Okay, I don’t really care about this project anyway. And I’ll be super petty. So I think [Esther] summed it up pretty well, like I’ll come up with a weird idea, and Esther will come up with how to make it more practical, more economical. So I guess Esther really puts it together.

EF: Awww.

OP: I also spend so much fucking time on the internet that I feel like a lot of things that come up in Internet culture or social media, the different things that people talk about I like to inject in our projects sometimes.

ES: As seniors are your plans for graduation, post-graduation? Do you plan on still working together as a collective?

OP: I think that’s a really good question actually. I think we both know that we can’t undo being activist-artists anymore. At first, I really cared about food packaging or whatnot, and I couldn’t give less of a shit right now. So I think we’ll be working closely with the Asian community no matter what we do, or where we end up.

EF: Because we don’t know where we’re going to end up, as in we’re probably going to be in different states or different countries, even if we aren’t able to continue managing this Sad Asian label, I think we still will continue to make work that is relevant to our identities, or at least some type of activist work. When I’ve said this to other friends, that Sad Asian Girls probably isn’t going to be forever, they saw it as this tragic thing. But people don’t need a snazzy name to make activist work. And I think what we’ve been doing so far is encouraging other Asian femmes to continue making work, knowing that we might not continue doing it together. Ideally, people will still make work and not really need a group like us to do it.

OP: What’s more important is that young people — we’re millennials, but what about gen z? — need to get it together and make work and that’s what we’re trying to do, have some type of presence so that they know it’s an option to make work, and that’s important to me. It’s also so easy. Executing a project or thinking up ideas is so simple, and I feel like based on what I’ve read about your generation, you guys are so much more active, and you guys care so much more about social issues than previous generations, and that kind of excites me, because I wonder where you guys are going to go with that. Hopefully it’s not the new high school phase, hopefully you all bring that to college with you.

EF: You’re born on the internet. Everyone’s on the internet, so you have a bigger audience. It’s better for you. You can get your stuff out. That’s why design matters more and more. You can only get more publicity and more circulation if you have a strong voice and what you say matters to a lot of people.

ES: I’ve noticed very recently [during November] on your Instagram there’s been a lot of posts styled after what you’ve just talked about. What was that project?

OP: We went to New York a couple days ago, and there was an event called “Scamming the Patriarchy,” at the New Museum, and a ton of small art collectives got together and made art installations and also talks. Our assignment was to do some kind of instagram takeover, so we posted one video on the main museum page, and on our Instagram we got submissions from femme creatives in general to send encouraging words to other femmes. We got 90 submissions or so, and we had a lot of positive feedback.

EF: That project again came from an issue that has frustrated a lot of marginalized groups in America. We planned that project as a result of the election. During that time, what people really wanted to hear was not more facts about Trump. They wanted to hear from other people, who were in similar situations, about how to move forward, and also how to take care of yourself and where we can look to at this time. Having so many statements and just bombarding everybody who follows us with those posts also had an effect.

ES: In the same style as the Instagram posts, what sort of advice would you give to other sad Asian femmes right now?

OP: If you have a good idea, try to find the people that would love your idea, and do something with them. Even if it’s just one random small thing that you don’t even know will make a difference, if it reaches out to at least one person, I think it’s so worth it. Just make work, and generate content, and think about the way that you’re going to publish it. The web is an amazing place, and you should take advantage of it.

EF: I probably have less of a place to say anything [post-election], because I’m Canadian, but I do think that in times of turmoil, or in the event of tragic occurrences, it is important to grieve and process what is happening and be around people if that’s what you need (or be alone if that’s what you need). But also keep in mind that staying in that state of depression, not that it doesn’t change anything, but it also will hurt you in the long run. While it is trying to process things and maybe isolate yourself, I think self-care also includes doing something about it, or expressing your thoughts in a productive way that other people can resonate with. And creating community is a really crucial part of self-care.

OP: You are not alone! Don’t forget that. •

Interview & Illustrations by Elisabeth Siegel

sinθ is an international print-based creative arts magazine made by and for the sino diaspora. Values include creative expression, connection, and empowerment. Find out more here.

Follow our Sino arts blog for daily posts featuring Sino creatives and their works.

Issue 5 will be released in August 2017.

Instagram | Facebook | Blog | Donate | Submission guidelines

#sad asian girls#esther fan#olivia park#sad asian femmes#rhode island school of design#sine theta magazine#written#interview#conversation#issue3

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on the Function of Art?

(R:) I didn't want to append this to that big thread about censorship, questionable story content, and authorial intent because I am a Small Person who just consumes things and I was pretty sure that I can't actually add anything useful to the discussion. But I'm still stuck on it a little, so here is a thing that I'm putting behind a readmore in case everyone is fucking tired of the whole censorship debate.

tl;dr: Riss is old and grew up in an environment that was not exactly info-rich when it came to controversial issues. Riss is clumsily attempting to tape this and that together for some reason, possibly just to get it out of the brain. (This ultimately turned into a long fucking story about my early life that doesn't really go anywhere. It's just a long fucking story.)(**ALERT: This includes discussions of stereotypes, slurs, and fetishization.)

People in that thread pointed out the weird over-reliance on interrogating an author about what exactly they meant by writing certain content and that authorial intent should be a yardstick for whether certain content is edifying (and deserving of existence) or not. Other people wisely pointed out that every consumer will inevitably interpret every creation through the lens of their own experience and come up with a different take on what the piece is "saying" about whatever it depicts.

Back when I was very young, there was no way to directly contact any sort of creator. Novels had small text somewhere that mentioned how to send snailmail to the author C/O the publishing company, but naturally there could be no expectation that an author would ever actually write you back. Direct contact with creators was usually in the context of them being guests at a con or signing or gallery showing, which was sort of like seeing a band play live. Every other exposure to them was one-way or indirect, through their work or news articles or possibly from hearing a radio interview or watching a TV program about them, if they were important enough. This was pre-widespread-Internet, so nobody had blogs; some big-name people had fanclubs that mailed out regular newsletters, but the vast majority of creators had nothing but their content in circulation.

I guess that the point of saying all of that is just to illustrate that the present-day situation in which creators have public social media accounts that one can just drop into and toss opinions and questions about intent at them is...kind of a luxury, in my experience? For writers of "classics," there might be printed articles or essays in which they went on about their intent or process, but for creators who weren't popular while they were alive, historians have to go mining for diaries or letters to even get an idea of what sort of person they were, much less what they meant when they wrote that one scene from that one novel that was Kind Of Problematic.

And that was a tangent leading around to a perspective about creative work in general that I heard very early on and took to heart when it came to consuming media. I read somewhere that the point of creating something was to produce a response or emotion in the consumer. Any response. The creation was meant to be a catalyst for newness or change in the viewer, even if the response was something like anger, fear, or disgust. The worst possible response to a creation was dull indifference, because it had failed to do anything at all to the consumer.

I saw supporting evidence for this perspective in a lot of media. Bands built up weird, elaborate Aesthetics purely to draw attention to their songs, not because they were demonstrating some deeply-held belief system. (I've lost track of how many CDs I saw from bands who made dark music about cruelty, despair, and the emptiness of the universe and yet, in tiny liner-note text, poured out flowery squee about how they thanked the loving Lord God and Jesus Christ for blessing them with their musical careers.) Artists who talked to other artists about their craft admitted that they often made the art they did just because they wanted to make it for no special reason, but they fabricated deep-sounding bullshit to attach to it so that collectors would buy the thing just for the story that went with it.

A piece that kept getting talked about over and over back then was Piss Christ, which was literally a large glass jar full of urine that had a crucifix floating in it. Large sections of society were fucking outraged that this thing even existed, that galleries dared to let it darken their doorways, that the artist was even depraved enough to think up such a thing. I don't recall what the artist herself (I think it was a she) said about why she made it, but what was clear to me was that she had succeeded at the goal of art like an absolute champion. Nobody could look at that piece without having some kind of intense response, and whole groups of educated people were compelled to spill out their opinions and argue about it. Piss Christ was Successful Art, the thing that every piece of art wished that it could be. It didn't matter that most of the responses were negative. Apart from making it, the artist did nothing to encourage all the discussions prompted by the art's existence. People used it as a springboard for debates about What Is Art Really, the empty veneration of religious iconography, public obscenity, and all sorts of other things, entirely on their own.

Granted, there were clear downsides to not having instant access to people's creative narratives and backgrounds, or to the greater community of consumers. There were panels discussing themes in modern writing at cons and sometimes a nearby book club where people could rec things and talk about good and bad aspects to whatever they were reading, but if you weren't in a position to have either of those things? There wasn't a lot to do but chat with any reader buddies you might have or actually trust marketing. This book is a NYT Bestseller and has its own special display in Borders? Well, must be a well-written book with quality content, or else it wouldn't have that kind of backing, right? (I was such a trusting little idiot back then, seriously.) So this was when all those toxic norms of casual misogyny, racism, and queer villainization went unchallenged in a lot of places and was just The Way Things Are.

My family moved around to many parts of the US while I was young and I swear I never heard people anywhere bothering to have a discussion about the trend of weak female characters or how POC cultures kept getting reduced to exotic window dressing. There was a sense that those kinds of intellectual topics were the sort of thing that academics did in far-off Academic Country, where they only read classic literature and went over word-by-word symbolism with ever finer combs. I'm no quality literature historian, but I imagine that those kinds of thematic conversations probably got louder as widescale communication got easier, such that a person could throw out into the aether, "Is it just me, or is the only time when cultural elements from Asian, Middle Eastern, Native American, or African civilizations turn up in mainstream lit is when they need 'exotic savage foreigners'?" and people would be able to chorus back, "OMFG THANK YOU I thought I was the only one bothered by that!!" (I mean, advancements in communication helped every minority find other people like themselves, which is why the Internet is part of real life and a genuinely precious resource to isolated odd folk who are forced to live in places that are hostile to them. You no longer have to live your entire life being the only lonely freak instance of your kind in the entire universe.)

So I recognize the shitty situation of having mainstream marketers telling people which stories were good and which story elements were admirable without also having access to Discourse that would challenge those norms. I remember just accepting that girls would hardly ever be able to be heroes the way boys could be, and that people from far-away cultures were always primitive and backward but in fascinating ways. Nothing in my daily life countered anything that I read. Discussions that I found online much later in life caused me to rethink the trends in everything that I'd read as a kid and see it all with fresh eyes so that I could realign my opinions. It's vital to have discourse and challenge happening alongside creation so that we don't have generations of people absorbing shitty norms that are supported by fiction and not realizing that there are even alternative ways of seeing things.

But there's still that issue, in my mind, of a good creation being one that creates ripples far outside of itself by prompting any kind of response in the consumer. Which is, I guess, why it seems fine to me that Problematic things exist and that people encounter them even if they come away hating those things. The encounter with that thing can make a person think about their own perceptions and experiences, and it can prompt conversations about was learned from that encounter - the why of the result and what it means. Obviously, the same can be done with media that makes a person happy or comforted, and that ends up in Discourse because people end up comparing their experiences and questioning whether the people who are happy/comforted are correct to feel that way about the media.

(Bonus Tangent: it's never possible to be incorrectly upset/offended, only incorrectly happy, strangely. Because telling people that they are not allowed to be upset about something is controlling and aggressive, but telling people that they're wrong to enjoy something is...I'm not finding any positive result. It's shaming, which is a response used to exert social control over others. Talking about whether or not casting shame on total strangers leads to the desired result is something that even I don't want to take the space to talk about. I'm one of those who considers emotion to be out of a person's control. Emotion precedes action. What's important, IMO, is what action a person takes regardless of what emotions they might have, because it's possible to choose actions. Telling a person that they're not allowed to feel a certain way is an attack based on something that a person can't actually control. Whenever I see antis saying things like "no one should ever enjoy this content," I wonder how people are supposed to casually shut off their enjoyment. Can the antis shut off their outrage with a flip of a switch, since it's just an emotion too? Attempting to reprogram a person's emotional or motivational palette leads to things like conversion therapy, which has a high rate of failure/relapse and tends to traumatize people into other mental deformities. That's why it's far more useful to focus on responses to emotion instead of emotion itself. People with uncontrollable emotional responses - such as phobias or fetishes, say - can learn adaptive actions faster than they can unlearn emotional responses.)

This was a hugely roundabout way of saying that I really think that bad media or problematic media are still important. They can prompt discussion and introspection, as mentioned, but, IME, even a shitty representation of a concept can put cracks in a person's worldview and make it possible for them to be open to better ideas in the same vein later on.

For instance, I had that strict mainstream heteronormative upbringing. The only thing I knew about queer people for a huge part of my life was that they needed to be pitied because they were going to hell, and the closest thing to a trans person that I knew about was that Crying Game trap drag queen concept where the sinister man in a dress seduced honest straight men with borrowed feminine wiles. (I literally did not know that transgender people were actually real until after I was 20, which is one reason why I am such a massive late trans bloomer.) I also had that strict gender role upbringing in which there were certain things that a person must and must not do in order to be "proper."

Back when I first got on the Internet and started interacting with fandoms, genderswap fics were popular in my circle. Often, it was basically the same plot as the source material, but you'd switch everybody to the opposite binary gender and then, based on the assumption that men and women think and do things in slightly different ways, the plot would usually derail from canon because the genderswapped characters wouldn't do the same things that they canonically did. It was just one of many common fanfic thought exercises.

Looking back, reading genderswap fics was something that started eroding the strict worldview that I'd inherited. The "men and women just naturally do things differently" was enough in line with traditional gender roles that it passed by my defenses, but the swapped cast of just about everything ended up with lots of strong, heroic women and the occasional male sidekick. Further, writers tended to use the "women are more socially/emotionally intelligent than men" stereotype to correct shitty things that male characters did in canon because, if they were women, they'd be too smart and perceptive to do whatever stupid thing they did and everything would have happened differently. Nowadays, there's formal discussion about the lack of strong female characters in mainstream fiction, but in fandom, female writers just fixed the problem directly with genderswap so all the interesting, powerful people could be women and the guys could be useless arm candy for once. It was a way of reclaiming importance and power when canon media didn't give women much else to work with.

(I became aware while ago that Discourse is informing people that genderswap fics are hugely offensive to trans people. Now, I've described my crappy upbringing, but as a trans person, I don't understand this at all. I get that the "opposite gender" swap upholds the gender binary, but the issue is offense against trans people, not against genderqueer or nonbinary people. I seriously don't get why I should be offended? Is it because the genderswap doesn't include actual RL transgender experiences, as if the entire cast were realistically transitioning as a plot element? Genderswap is not acceptable unless it specifically includes things like "this is the story of how Cloud Strife got her testicles removed and enjoyed growing breast buds thanks to HRT"?? Maybe I'm an idiot, but those are two distinctly different story concepts and both have merit. o_o)

Later on, I became aware of people who were preoccupied with stories and fantasies of fantastical gender transformation, usually male to female. Some stereotypical male character would get injected with an alien serum or zapped by a fairy's wand or something and he would immediately metamorphose into a woman. There was often a disturbingly rapey element to these stories, like the boy wouldn't want to be transformed and was horrified while he was changing, but after he settled into the woman-shape or had sex as a woman after changing, he realized that he loved it and felt so much better that way. The stories were mostly just short repeats of this exact same situation, written by different authors with slightly different details, and this group never seemed to get tired of them.

Eventually, I learned that most of the people in the core of this group identified as trans women, but they lived in circumstances where they weren't permitted any female expression or had lost hope of ever transitioning. They fixated on transformation fic as a way to soothe the pain of living. Looking back, the noncon/dubcon themes that kept appearing in the fics made sense as a way of indirectly satisfying the powerful social forces that were demanding masculinity of them. The male characters were trying hard to stay male, fighting back against the transformation; they were clearly performing all the do not want signals expected of men threatened with feminization. They fought the good fight, but the enemy overpowered them! Womanhood was forced upon them! It was totally unexpected that they enjoyed being a girl after all, but because their maleness had been aggressively destroyed, they were free to stop performing resistance and love themselves.

But you can find fetish material like this in a lot of places, without any context as to the intent of the creator. (And I'd argue that it counts as a fetish if you crave it as necessary somehow, regardless of whether or not you're jacking/jilling to it.) Some people would write the same kind of stories for forced feminization as a type of humiliation. Among furries, transformation fetish material seems to add an extra angle of growing into new power and strength by a change into some larger, more magnificent creature in addition to changes involving sexual characteristics.

Further into the fantasy fetish scene is smut involving dickgirls/cuntboys. Those terms are inherently objectifying and fetishizing; the focus is entirely on the genitals and how a person has the "wrong" ones for their body. Understandably, this is where trans people get turned into dehumanized kink fuel, and real life "tranny chasers" exist who try to weasel into relationships with trans people just to have an embodiment of their fetish.

Artists seem to be slowly getting better with at least giving a nod to real trans people when tagging this sort of art, but (likely to get the most search hits) usually it's just "transwoman/man" alongside "dickgirl/cuntboy." And the art, at least, is clearly designed as fap fuel, so it's not like changing the label makes the content more respectful to the real humans it resembles.

Fetish art with that sort of name shouldn't be uplifting or encouraging because it makes trans people into objects, I know. But I enjoy it when I see it not because it gets me hot in itself, but because I feel heartened when I see sexy art of, essentially, trans people who have not had any genital surgery. I'm fortunate in that I don't have the worst soul-crushing dysphoria surrounding my (still XX factory standard) genitals, but I know a lot of trans people get seriously torn up about theirs and worry that they'll never be truly attractive to others because their genitals are "wrong." While it's possible to find humiliation art online of people with all kinds of body configurations, I tend not to (YMMV again) find much that seems to be specifically shaming or hating on characters who have trans genitals specifically because they are wrong/ugly/queer/etc. They're just participating in enthusiastic hot sex like all the other characters. Sometimes they're literally just standing around looking sexy, like any other badly-posed pinup. But when they're in the mix of whatever smut they're depicted in, they're objects of desire with their own sexual power, unashamed and equal to the others, and the other characters find them attractive and are clearly really excited to be doing whatever they're doing with that hot trans character.

And this response is very problematic, I know, because smut of trans characters that's designed to satisfy fetishes actually does lead to cis stalkers who want trans partners as living sex toys. And art of pre/non-op trans people being sexually liberated and desirable might end up being nearly indistinguishable from most of the fetish art I've seen, apart from lacking the objectifying dickgirl/cuntboy label. I hate seeing those terms in art tags, but the art itself makes me happy. Not even aroused, just happy to see characters who are essentially pre/non-op trans people being desired and enjoying themselves. When you've lived your life believing that you're ugly and unlovable, seeing people similar to yourself in those kinds of situations is a Band-Aid on an old, deep wound. I wish someone would look at me that way. I wish someone wanted to touch me that way. And even if you can't have that for yourself, you can at least look at art where similar people can, and even if those trans people are imaginary six-breasted purple foxtaurs, you can still feel like at least there are trans people somewhere in the galaxy who are free and happy and desirable. It's the same as those trans girls who spent years telling each other the same MTF transformation story over and over and over even though it was pure fantasy. They needed periodic inoculations of that fiction to keep themselves afloat when they believed that they could never have the reality.

That's why, to return to my earlier point and to the points that the people in that big thread probably said better than I have, I don't want bad media to go away. Even gross White Man Story For White Menfolk fiction can at least prompt discussion and response and might have little bits in it that made someone out there think of something in a way that they haven't before. Even depictions of minorities that are pretty clearly designed to be shallow fetish fuel might be a lifeline to some isolated person to whom that shitty depiction is the most positive representation of their identity that they've ever seen. You'd hope that they'd quickly be able to find better ones, but beggars can't be choosers, and if that shitty depiction hadn't existed then they might never have had the chance or the knowledge that different views were possible. You just can't know what people see and think when they consume a particular piece of media. They bring so much of their own context into the experience.

That's why I wish people would focus on action instead of on vague, catastrophizing speculations about intent or potential or who has a "right" to create or consume certain things. There are at least a couple of stories floating around about female fic writers who regularly wrote m/m smut, but who, IRL, opposed same-sex marriage and disowned their queer relatives. IMO, that's how you can tell who is making objectifying content - by whether they treat actual, living representations of minorities/fetishes like frivolous entertainment. I would bet that those IRL-anti-queer fic writers wrote things that were indistinguishable from the general mass of fanfic, which was why other fandom people were shocked to discover their IRL actions. People create things for all sorts of different reasons, not because ther creations are a clear window into their innermost motivations. You just can't know what's in a person's head, no matter what sort of things they create.

And I've literally spent hours writing this and sort of vaguely editing it paragraph by paragraph, so I'm going to post this now and release myself from childhood memory hell. Ultimately, that reblogged thread still said all of this better, but I just had a compulsion to LET ME SING YOU THE SONG OF MY PEOPLE FOR TEN FUCKING PAGES. :P

And oh hey, I was so caught up in time-warping back to the 80's and early 90's that I forgot that Wikipedia existed, so here's their page on Piss Christ. Turns out the artist was male. Says it was only a photo?? Lies!! I distinctly remember seeing the goddamn gross jar of pee!! Because human memory is a reliable, unalterable record!! (Okay, I've clearly gone on too long here. I apologize to the whole internet in advance.)

#fetishization#queer#early life experiences#slurs#queer fetishization#fandom politics#not even sure what to tag this as so just sort of be generally cautious

1 note

·

View note

Text

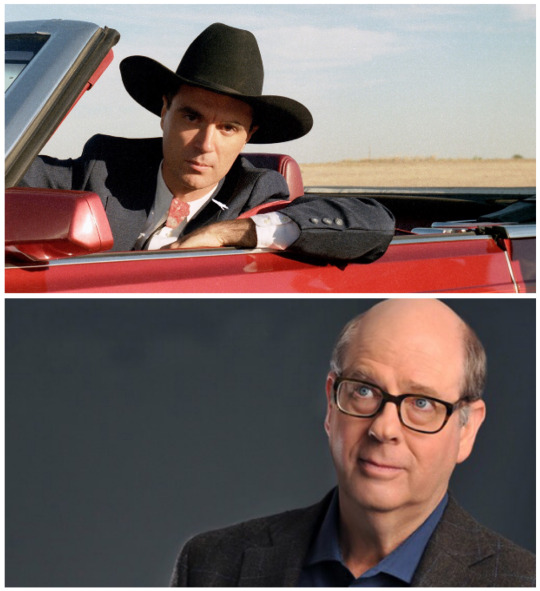

True Stories, From Stephen Tobolowsky

Next week, David Byrne will be in attendance for a Q&A at two screenings of his film TRUE STORIES, on March 13 at the SXSW Film Festival in Austin, and the following day, March 14, at the Angelika Film Center in Dallas, sponsored by the USA Film Festival. To get the straight dope on the film’s creation, I spoke to Stephen Tobolowsky, co-screenwriter along with Bryne and Beth Henley. He can be found online at stephentobolowsky.com.

"True Stories" was also recently released on Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection in a package that also includes, for the first time ever, the film's complete soundtrack.

Below is a transcript of our interview, which also includes a great story about the time Tobolowsky wrote a song for Willie Nelson.

Nathan Cone: I want to thank you in advance here for just taking a little bit of time to talk to me about this particular picture. I remember listening to the podcast episode on it long ago and there's great stories in there, and I just want to kind of dig a little bit deeper into this movie and talk a little bit about it especially since you know we here at Texas Public Radio have that connection to that time and that place and... So thank you for....

Stephen Tobolowsky: Yes. My pleasure.

Going back to when I remember listening to that podcast, you mentioned in first meeting the Talking Heads that you knew very little about them at the time that you went to the screening of “Stop Making Sense.” Just first off, what was your impression of the band, and of David Byrne after seeing and hearing their music for the first time?

Well it was kind of it was kind of mind blowing, not knowing any [of them]… just Jonathan Demme was kind of our friend at the time, because he wanted to do a project with Beth [Henley], some sort of writing project with Beth, and she had just won the Pulitzer. So she had that cache and you have to imagine going into the Academy theater, which I think is 9500 seats.

Yeah.

Perfect, perfect screen, perfect stereo, knew nothing about the talking heads. Beth and I are sitting kind of in the middle back of the theater with Jonathan his ex-wife Evelyn and with David Byrne. So the five of us are sitting back there together and the rest of the Talking Heads, Tina and Chris and Jerry, they're up front. They're sitting up front, so all I see is the back of their heads, and the rest of the place is absolutely empty deserted. And then the movie starts. And it was my introduction to the Talking Heads sitting next to David Byrne! It was almost an out of body experience. To hear that music for the first time from Psycho Killer to Life During Wartime. Take Me To The River. All those songs with David sitting next to me. And the in my curious life, the only other time that happened was when Beth and I went to see the Brad Dourff…Walter Houston directed me…. John Houston directed it… where he's the kind of crazy preacher?

I don't remember.

It was one of John Houston's later films. I think after “Chinatown,” and we went, Beth and I, went to see an afternoon feature of that and John Houston came and sat down a seat away from us and was eyeballing us the whole time. But I lived in Los Angeles so freaky things like that could happen. But David was kind of eyeballing us the whole time. And I had the "watched" feeling, like I was being watched, watching this movie. And so I was so delighted with the music overwhelmed me and I just fell from "watched" into pure joy. And I think Beth and I could have been the greatest audiences for that film ever, in that theater because afterwards all we could do-- we went out to eat with David and with Jonathan-- and all we could do was just scream basically in the restaurant about how great the movie was! And David, of course, I think I mentioned in the podcast all David wanted to do was wanted criticism.

Yeah he wanted the real feedback!

He wanted criticism. Don't say--you know after I said "oh this is great!" He said, "What do you think of the big suit?" "Oh, the big suit is fantastic." That's the center of the film. That's the you know the whole film changes after that because the sound becomes more intense and it was coming out of different speakers in the theater so that the orchestration of that film, when you're in a big theater with a real sound system is incredible. So by the time you get to Take Me To The River, that film is blasting. Did I answer your original question?

You did!

It was an out of body experience. That's as close as I could say, sitting next to him and knowing I was being watched every second. And the moments of transcendence that came with the film overcame my feelings of being watched were frequent and more frequent as the film went on.

Fantastic, fantastic! Well when it came time for you and when Byrne and you had connected and he had started coming up with this idea for the film that would become True Stories you've related how he did the series of drawings that he thought would make great visuals I guess in the movie? And as you two were examining these drawings did he ever, ever say anything about what was happening in the drawings or was that left for you to interpret?

Yeah. First of all when I came over to David's house the drawings were already done. There was no script but there were maybe a hundred-plus drawings on the wall. Just pinned to the wall. Pencil sketches, and drawings of frames. No script, but just drawings. And David asked "Can you turn these pictures into a screenplay?" And I said, "Well, let me look at them." And then I went. And it was like being at the Museum of Modern Art. We were silent. And I want to say for like two hours. I met him at noon and I started looking at the pictures at about 12:15, and I finished looking at them at 2 o'clock, and for that period of time I don't remember a word being spoken. David stood with me looking picture to picture, examining me as I was examining the pictures. And I took notes, and again, nothing was really exchanged except I said, "I'll tell you what. I'll go home. Let me work on an outline based on these pictures. I'll work on maybe some dialogue from some scenes and give it to you tomorrow. And if you like it you can hire me to do the screenplay, and if you don't like it the outline is yours, you can keep what you want or not want, it's free, no problem, I'll do it for free. And so I went home and I did about 35 pages of outlined and then with scenes a few scenes sketched with dialogue and character kind of portraits of people. And David came over to my house and I gave him the outline and I said just look at over let me know what you think. And then I gave him a general impression of how I saw the movie and that was the music is going to be the star of this movie. So all the screenplay has to be is an open enough structure for the music to exist. And I think David and I agreed with that point and I think what David ended up doing he felt that my script-- or my take on it-- had much through line too much connection, too much character development. He wanted it more to be, I think, iconography, very much like the original pictures. He wanted there to be something like hieroglyphics about it. And I recently saw the film a couple of times one at a film festival in San Francisco, one at the Walker Center in Minnesota, and it holds up so well and I think one of the reasons it holds up so well of course is the music, and that it is so curiously out of time. I think David's approach to it was perfect because nothing is really connected to a time or a place, and especially him in that cowboy outfit with phony cars. And the fashion show, oh my god!

It's like a Texas of your fantasy. You know, his outfit? Were things in that early stage, were things like the sesquicentennial or the celebration of "specialness…" or even Texas part of what you were giving him, or did that come later on, like after he went to Texas and you famously took him to visit your parents and your mom offered him too many soft drinks…

Haha! The sesquicentennial was probably my first idea in that I was thinking, “OK right there is a perfect Talking Heads talking point.” It is a weird word, sesquicentennial. It sounds like a celebration, nobody knows what the hell it is, and it is enough of a structure-- an open structure to put the music in. With the sesquicentennial I said you could have the time capsule, you could have the Shriners and the little cars, you can have a parade. You could have a fashion show, a talent show, you could do all these things linked to the sesquicentennial. So that's first, that was the primary idea I had when I looked at the pictures, and that idea David loved. And I think he loved "sesquicentennial!" I think where I went with that is making relationships between the mayor and the Lying Woman that, you know, to give them rationales for jobs involved with the sesquicentennial and I think David didn't care for that. You know I think he thought that wasn't necessary. That was too conventional. And the I guess the order of things is... (I) wrote the script, gave it to David... I'm trying to think when we toured Texas together with that with the drinks, you know with mom and the drinks. And it was, because I know it was about a year later after--we had to deliver that script in something like.... 19 days is what they asked for Beth and I to-- Beth went over and met with David first. She was the primary point person David wanted to see, and then she called me. This is before the age of real cell phone use. So I think she called me from David's house and said "Sweetie, I can't make heads or tails of these drawings. I think, I think they need somebody who's good at structure. You know, I'm better with character, why don't you come over here and take a look?”

So Beth came home and I went over to David's, and that's when I looked at the stuff. And then after I gave David the outline, the next day he offered Beth and I to co-write the first draft but he had to have it in 19 days. Something crazy. And so it's... it's David Byrne You know it's Talking Heads. We're like nobodies. It's like, "hell yes." And so we jumped at it and we finished it. And the way we did it is Beth and I alternated scenes, she would take certain scenes, and I would take other scenes, and then we put it together and hoped it made sense! And we gave it to David. And I don't think that's when we went to Texas. I think we went to Texas when the film was getting more to where he was looking at locations. And so it was David taking that script at that point in time, and we didn't see him for months afterwards. And it was after that, you know we didn't hear anything about the project. We didn't know that went into a black hole of space. It's when I'm driving in the Hollywood Hills and that's when there's a knock on my car window and it's David Byrne on a bicycle, and he's going like "roll your window down." He says, "Sorry I haven't gotten in touch with you we went on tour and I've been rewriting the script. There's something I need you to hear." And that's when we went back to we're better not lived up in the hills. And David said he added the character that could hear tones.

Yeah.

From my ESP story, and wrote the song "Radio Head," and he played me "Radio Head" in the living room which was… you want to talk about... there is the public mind-blowing experience of being introduced to the Talking Heads at the Academy, in the Academy theatre with David Byrne sitting next to you. But then there is the private mind-blowing experience, when David has taken part of your life... pretty much the courtship of Beth and myself... and turned it into a classic rock'n'roll song. And hearing that in my living room… I mean, I still get weak in the knees when I think of that moment and that how great that song is. I think David is just such a genius and it we were lucky that way.

See what's interesting about that song, and that experience that you describe, and about the backstory behind it, about the fact that you had this psychic experience that was happening during college where you were able to hear tones and delve information about other people from them and that became the song "Radio Head," but you also talk about in your podcast about that being kind of a negative experience for you, and that you shut the door on it.

Yes.

So how did you reconcile both the song being written about that and also the, probably the conflicted feelings you were probably having about that being a part of your life where you said "you know what. That's just something that happened to me and I clearly don't want it to happen again."

Yeah but it is that old mistress, time, and it happens all the time when you think about it. Side event: I was in a hit play on Broadway, "Morning's at Seven." We were nominated for something like 13 Tony Awards 13 or 14 more Tony Awards than any straight play history of Broadway. This was in 2002. We were playing to 95 percent capacity. Uh, Lincoln Center had extended the show once, was ready to extend it again. We had been performing pretty much for nine months straight, and we all got together, the cast got together and said, "No. We want to go home. We want to quit." And you go like, "oh wait a minute." Everybody's heard the story of actors who struggle and struggle and struggle never succeed. But you don't hear the story of actors in a runaway success on Broadway, the dream you want, acclaimed by critics, who say, "we've had enough. We need to go home. We can't do this. It's too hard." And kind of the... hearing the tones. There was the exuberance. First of all, there was the scariness of it happening. So terror is compelling... of what happened and the fact that all those things, as my teacher said, were true that I was able to read about his life. Then it expanded to Beth and I got together because of it and her charging 25 cents to a dollar for me to read people's tones. And then we were gonna collect the money!

I just picture like Charlie Brown, the Charlie Brown thing in front of you.

Yes! It's the lemonade stand. It's hysterical. And so our living together and our romance blossomed from this, and that was all good. But the more I did it the more it intruded into my life, and I couldn't stop it. And it became incredibly creepy and scary, and I had no peace. I had no peace of mind. So I tried to stop it. And so I quit doing that. Yet at the same time, you know, I've had unexplainable events that happened since then, that kind of fall in the same category. And my explanation of it is that it's not extra sensory experience, it's just sensory experience. It's things that probably happen to all of us, to one degree or other, and maybe we're aware of it, maybe we're not aware of it. So, I don't think it is any kind of form of magic, but just something that has not been really subtly explained.

Yeah. Most people haven't been able to pick up on so to speak.

I think... I don't know if I have told you the last time [my wife] Ann was going to do a surprise for me for my birthday. And this was not long ago. And she's always asking me if I'm using my ESP and I'll go, "I don't know, baby I don't do that anymore." So you know she was jesting me that she had something really special planned for my birthday. And so I said, "You know, I'll tell you what, we'll finish this in one swoop here. I'm going to write down on a piece of paper, seal the envelope, put it on your desk, of what we're doing for my birthday. And you know, we'll see that ESP is phony and we'll go have a great time." So I wrote down on the piece of paper "going to Disney Hall downtown Los Angeles to play on the grand piano onstage." And I put it in an envelope, put it on a desk, and she said, “well, dress up nicely like you're going to have lunch with the president or something like that.” She said, "Well the restaurant we're going to is kind of snazzy." I'm going, "All right...." So I put on a suit. She said "It's downtown. Why don't you head off kind of... It's right across the street from Disney Hall. So just drive down toward there and we could probably park in the parking lot under the symphony hall. And all of a sudden I have the sickest feeling in my stomach.

We we come up the elevator for Disney Hall and the custodian is there. My friend Robert Brinkman is there with the suitcase filled with my piano music, and the custodian opens the Grand Hall, and there onstage is the grand piano, center stage, and I go up there and I play for about an hour and Brinkman, who filmed the "Stephen Tobolowsky’s Birthday Party" filmed the thing and took pictures of it and all of this, and I got to play Beethoven and Bach and Brahms and Mozart on the grand piano in Disney Hall. And the whole time inside I am feeling, like, "what is going to happen when we get home?" And we got home and Ann was so mad. She thought I'd either been snooping on her computer or spying on something or... and I said, "Listen. You know, it's probably one of these things to where I observed something at home. And it kind of goes in the back of your brain." And it's when they put when forensic psychiatrist give you hypnosis can you recall that the suspect is you may recall these things that you don't consciously remember.

Yeah.

I said, "So it's probably something like that," but we've never quite gotten over that event.

Yeah, wow. Circling back to the movie here and how it how it went. When you first saw it… you've spoken about how it seems about 13 or so of your lines your and Beth's lines made it into the final film. And what. What. What was in your original draft that you think might have been in the film? You know, what would it have looked like it in y'all's original form?

We had lots of jokes in there. You know Beth always writes very macabre things. And so a few of her lines in there that remain in there was, "he had a tattoo of a bulldog on the stomach." I think that was like one of Beth's lines that still was in the film and my stuff was like all the preacher stuff, the church scene with the preachers singing, the old white guy singing the gospel song?

Oh yeah, I love that.

About have you ever figured conspiracy, and how you always run out of toilet paper towels and Kleenex at the same time.

And later on there's the other character who talks about the hot dogs and the buns too!

Yes. So all that stuff was mine. So we have those kind of jokes all the way through the show. And I think for example some of that stuff was a launching pad for Harvey, the Lying Woman who's always lying. Like a lot of Beth's script was a jumping off point for her. But I think she improvised or extrapolated or changed a lot of Beth's lies. But Beth had some pretty hilarious lies for the Lying Woman. So I think those could have remained in the movie but you know you're filming, and a lot of times improvisation feels more vital while you're filming, and so you keep that in. I think I had more Spalding Gray. I think the mayor and the computer guy had more scientific blather that I had put in there, and I think a lot of it was removed for time, and who needs that, and let's get to the next song. And the songs were better than our dialogue or jokes! That was you know, that goes back to the original idea that the songs were going to be stars.

One of the things I really loved about this movie is that it's very gentle in its nature.

Yes.

And that it's really a celebration of people and the creations that they make and how it's just as important as, you know, the hip stuff that's happening in L.A. or New York or wherever and that you know we're kind of smiling at the outrageousness of it all. But, you know, we all have that within us, these elements of outrageousness and quirkiness that I think we can recognize in these characters in the film. Was that part of y'all's original ideas well the kind of gentle celebration of the "specialness" that the word is used?

Yeah, I think I think that has... that I think was just serendipitous if you take a look at the like Tobolowsky Files, and all the stuff I've written since then. There is this kind of celebration of mundane events, and if you take a look at Beth's writing she always has made the ordinary extraordinary. And after listening to David's new music, he always... It's just amazing. He does the same thing in celebrations of making ordinary events absolutely, stratospherically, cosmically unique. That seems what he is about in his new music now. So in a way we were very lucky, because I really hadn't written much except a lot of unproduced screenplays at the time and a couple plays. Beth of course had written about two or three plays and one screenplay, all of which eventually got produced because of the Pulitzer, but she didn't really have a lot of work under her belt either. And it's amazing that we were all sort of psychically on the same page, that we believed that there is miraculous in the everyday and in the average. And that seemed to come through with all of our writing. We ever had to work at reaching the same tone or having the same conclusions. We were like that all along. We were always on the same page with that.

Yeah, nice. Well lastly referring back to "Radio Head" one more time. Have you ever met any of the members? Have you met Thom Yorke or any of the members of the band?

No, never met those guys, but I tell ya, it's on the to do list. It's on the to do list. When I did the event in San Antone, had the had I told you the Willie Nelson story? Did the Willie Nelson story happen yet?

No, you hadn't.

Just just in terms of wildness and the craziness.

Please!

So, in “Adventures With God,” the story I did, but in the "Exodus" section of my life with Beth, there's the fact that T-Bone and Betty and Beth and I, we couldn't get anything going in Los Angeles we couldn't even work for free! And so one night we're all sitting around the table drinking beer and I said "Hey I have a great idea guys, I just heard this 'Red Headed Stranger' thing, and I think this Willie Nelson guy really has talent, you know, I think he's going to go places." And they're all staring at me. "What are you talking about? It's the number one album in the country!" I said, even better. "What if I write a song for Willie Nelson? I will write a song for Willie Nelson. We're from Texas, he's from Texas, and if he buys the song, we'll have money for rent for acting class, and we'll probably be able to parlay it into getting an agent." And T-Bone goes, "Why not?" And so as the story goes in the book I sit down, write a song for Willie Nelson. Betty sings it, we record it on the little cassettes on our phone answering machine. And Beth said when we finished, she said, "Well where are you going to send it?" And I said "Well that's a good question." I said, "What if I send it to," I mean Willie Nelson is kind of like Santa Claus. "What if I just send it to like Willie Nelson. Austin, Texas, I'm sure it'll get there." The Post Office has to deal with this all the time. So the next day I take the cassette down in a padded envelope covered with stamps addressed only to "Willie Nelson, Austin, Texas." And that story is in "My Adventures With God."

So sometime along this book tour, and it was either right before or right after San Antonio, I get a tweet from a young man in Rio de Janeiro. Gabriel Baretto. and he said he remembered me when I did a movie in Rio de Janeiro with his dad Bruno Beretto, which I did! I did "Bossa Nova," and I remember one day shooting the movie and there's this little kid on the set. And he said, "I thought it was really funny when my mama kept punching you and you kept falling on the floor." Which is true. Amy Irving kept punching me in the movie and I kept falling on the floor! He said. "I saw you had this book and I remembered our childhood memories together so I got the book and I loved it, and I have a question. Do you still have the song for Willie Nelson?" And I said, "Well actually I do. I re-recorded it with some friends of mine just so I wouldn't forget it." He said, "Well [if you] have the sound file of it, send it to me because I'm standing next to Willie Nelson right now." And I said, "You've got to be kidding!" He said, "No. I showed Willie the part of the book where you wrote the song addressed to Willie Nelson, Austin, Texas. He thought it was hilarious and he wants to hear the song for Willie Nelson." So I sent him to file. Gabriel Barreta said like, "Willie's listening to it now. He's laughing, he's giving me a thumbs up. Stephen I don't know, he says I've heard the song. I think it's a really good song. I don't know if it's going to be on Willie's the next album, but I wanted you to know that when you sent that cassette to Willie Nelson, Austin, Texas, it was finally delivered. Forty years later." And I'm hoping the same thing happens with Radiohead. I'm hoping that that event will happen. And these things happen, when you do creative things and you put it out in the universe, sometimes you get the strangest answers.

Yeah, and it takes a long time for them to gestate.

You never know. You never know what century it'll come forward!

Well Stephen, man, thanks so much for the time and I'm sorry I've kept you from your oatmeal for 30 some-odd minutes.

No no no, it's going to be so delicious at this point.

All right. Wow well thank you again very much, and thanks for all your wonderful writing. Are there new podcasts coming along in the new year, you think?

Yes, I finished about seven of them now. And I've just been in conversations with Simon and Schuster as of yesterday about a third book.

Excellent.

And so I'm thinking now of releasing the podcasts maybe in terms of anticipation of the book or something like that.

Great. Well, have a wonderful Friday, and thank you. I look forward to hopefully talking to you again sometime soon.

Same here man, love talking to you.

0 notes

Text

Racism: Fight The Real Enemy

Over twenty-five years ago, on an October 3rd, 1992 episode of Saturday Night Live, Irish folk-rock singer Sinead O’Connor exhibited a public act of civil disobedience, whose repercussions still reverberate to this day. Angered by the abuse and cover-up within the Catholic Church, she sang a heartfelt a capella version of Bob Marley’s classic tune, “War.” O’Connor revised some of the lyrics to depict the abuse and exploitation of youth, which culminated in her holding up a picture of Pope John Paul II. She ended this politically-charged moment by tearing up his picture on camera, adding, “Fight the real enemy” as the icing on the cake.

Needless to say, religious zealots and the righteously devout were appalled - calls were made to boycott her music, and destroy her physical albums and CD’s in effigy; SNL producer Lorne Michaels (in an act of genuine cowardice) not only disowned her actions in the press, but placed a lifetime ban on O’Connor from ever appearing on the show. Apparently, O’Connor held up a different picture (one of orphaned children) during the dress rehearsal, so no one had any idea the real target was going to be the Vatican, as represented by the Pope’s countenance. Actually, Michaels has an official policy that any guest who dares go “off script” in any way (as in improvising or changing up a written and rehearsed sketch) is deemed too risky, and O’Connor joined the ranks of non-controversial guest stars like Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman’s Louise Lasser, Charles Grodin, Martin Lawrence and Steven Segal.

Still, the fact that no one in the SNL cabal had the slightest interest in finding out exactly why Sinead had chosen their show as a platform for political protest speaks volumes to an overarching ignorance of the social ills we so readily live with, coupled with our insatiable need for finding occasions to be offended. No matter that the sex abuse scandals that O’Connor had the prescience to expose have come to light in the most egregious, heartbreaking ways (not to mention the veil of collusion and denial which is equally appalling) - vindication for O’Connor’s bravery and outspokenness has never been forthcoming.

I bring this anecdote up to illustrate precisely what Sinead O’Connor was telling us back in 1992 - that is, it’s time we fight the real enemies to freedom, liberty, justice and equality. Which is why, when some misguided SJW’s decided that the real enemies of racial equality were statues of dead Confederate generals on the grounds of municipal buildings, I was taken aback by both the naiveté and indignation on display. The argument was that the statues represented the Civil War - specifically, the Southern bias that sided with those who were against the abolition of slavery, which of course, would have to be interpreted as a stain on American history that needed to be rectified. And so, the campaign was one to have these statues removed, so that the average American who found it oppressive to be reminded of our history could go about their business without being subjected to their racist iconography.

Never mind the fact that not all Northerners were opposed to slavery, or that Democratic politicians often sided with Confederate policy makers on the subject; that some in the North actually owned slaves themselves, or that the great emancipator, Abraham Lincoln, was a member of the Republican party. Let’s just paint the South with a wide brush, accuse them all of being racist, and therefore justify our campaign to remove all evidence of Confederate statues from public places. Several years back, during the height of this controversy, I was attending the annual Wild Goose Festival in Hot Springs, NC. The issue was very much on the minds of Southern progressives at the time, and many were both passionate and vocal about their distaste of seeing statues of Confederate generals gracing municipal buildings.

I attended a late night philosophical program session where the topic of removing Confederate statues came up - out of the handful or so of us gathered around in discussion, I couldn’t help notice I was the only black person participating in a dialogue about racism. I listened to all the arguments about why those statues needed to go, how their very presence essentially validated our country’s racist past, and how they no longer served a useful purpose in our more ‘enlightened’ society. I held my tongue, and patiently waited until all the unified opinions had voiced themselves. Then I responded:

“So we should remove all these statues because of what they ‘represent’, which is oppression, racism and the genocide of African Americans. I see. My dad is from North Carolina, and his grandmother, my great-grandmother was a full-blooded Cherokee Indian. Let me ask you something, what should I, as a child of Cherokee ancestry think about the American flag? Isn’t it a fact that the settlers to America were essentially intruding on the Native American’s way of life? Did they not cheat, exploit, rape and murder my Native American brothers and sisters? Should I not view the stars and stripes as a symbol of racism, a symbol of the genocide of Native Americans, whom I can personally identify with? Should I not petition to have the American flag removed from all public and government buildings, as it serves as a constant reminder of the genocide of my people?”