#Milkweed is not just for monarchs

Text

saw a monarch butterfly on a milkweed plant for the first time in my life and it was like seeing a little legend play out before my eyes

#butterflies#personal#I mean in my head i know this happens all the time#but somehow I have never seen it#we have been cultivating milkweed along the edges of my yard#we never use pesticides#I have never seen a monarch here#we have a lot of others but never monarchs#and then i see a random one in a suburb#on a milkweed growing in a garden like a weed#nature just finding a way I suppose#maybe I should order some eggs and raise them here once our milkweed is a little more established#I wonder if that would work#or if their little hardwired genetic memories would just send them back to where the eggs originated

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

once again making a variation of this post:

If you are going to plant milkweed to help monarch butterflies, you are not allowed to get mad at other insects who come to the plant and eat the caterpillars. They are also starved for the habitat that milkweed provides, and they are not evil or bad or cruel for continuing their natural role in the ecosystem as predators of small caterpillars.

Planting milkweed helps monarch butterflies. It also helps more species than I can count or even list off the top of my head. Milkweed does not exist for the sole benefit of monarch butterflies.

If you want the monarch caterpillars to not get eaten, then you can buy a butterfly cage or build one and bring any caterpillars you find on the main plant into the cage with some potted milkweed, and keep them in there until they emerge as adults.

Nature is going to keep doing its thing whether people have decided monarchs are the most important species on that plant or not. The species that prey on monarch caterpillars are not being mean, or cruel. They do not know that monarchs are endangered, and neither do the monarchs. The predators of monarch caterpillars are playing the same role they've played for thousands of years - population control.

It's not their fault monarchs are endangered. Habitat loss and climate change are the reason monarchs are endangered.

You are not allowed to blame native species for doing their job on native plants in their native ecosystem.

If you look at a milkweed plant covered in half a dozen or more different species and your response is "Ugh! But I planted this just for the monarchs!" you need to learn and care more about habitat restoration instead of only caring about the pretty butterflies.

If your single milkweed plants has half a dozen different species living on it and this upsets you, then you really need to start thinking about the word ecosystem and start realizing, "oh, if this single plant is enough to attract all these species, then they must be desperate for habitat".

If you're mad that monarch caterpillars are being eaten on milkweed you planted, then here are your options:

Get a butterfly cage or build one. It should remain outdoors. Get several milkweed plants that are in pots that can fit inside the cage. Check the main milkweed plant for caterpillars whenever possible, and if you find them, transfer them into the butterfly cage onto the milkweed in there. Keep them in there until they form chysalises and emerge as adults. If you aren't home very often, you can look up youtube videos of how to gently remove the chrysalis and hang it up outside so the adults can fly away whenever they're ready to.

Plant more milkweed. Plant as many species of milkweed are native to your area that you can get your hands on. Spread milkweed seeds wherever it will be able to grow. Encourage your neighbors and friends to grow milkweed. Save the seeds and give the seeds away for free, and spread them in wild areas where other plants are allowed to grow (Try to avoid areas that get mowed down or tended to)

Figure out a way to cope with the fact that the natural cycle of life doesn't make exceptions for endangered species. It is not wrong or bad or evil or mean or cruel for monarch caterpillars to get eaten by their natural predators. Take pictures of the other species you find on the milkweed, research what they are. If you use iNaturalist, make observations for them. Learn to appreciate all the species native to your environment, not just the pretty butterflies.

Actually, planting more milkweed should be your #1 priority. The point of planting milkweed is to restore habitat. If the only habitat available is the single plant in your garden of otherwise non-native species, then yeah, you need to plant more milkweed.

#Monarchs#danaus plexippus#milkweed#aslepias#gardening#habitat restoration#climate change#gardening tips#Monarch butterfly#monarch caterpillar#if you think milkweed belongs solely to monarchs...you do not understand how ecosystems work and you should work on learning how they do.#If you're going to get pissed off about other native species preying on monarch caterpillars then you have a lot of learning to do#so go fucking do it#don't act like other native species are bad for doing what they've evolved to do over the entire history of this planet#It's not their fucking fault monarchs are endangered#if you want the monarchs to not be preyed upon then raise them in an enclosure#otherwise you're literally just gonna have to deal with it

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are native milkweed seeds so goddamn EXPENSIVE!

I'm not even talking like 'oh this is a pack of seeds for like 5 dollars' I'm talking 'why are you selling ten seeds for $9.75. Why is THIS person selling 5 seeds for $38.06 with $4 added in shipping?!'

Like, either I'm missing something and Sandhill Milkweed is way harder to grow and way less prolific than info websites are making it sound, or I am only finding the people trying to make big bucks off of milkweed seeds.

In other news, if anyone has sandhill milkweed seeds. Hit me up. Or, hell, I'll hit you up.

I'm trying to grow native milkweed in my garden, and trying to wean my neighbor off tropical milkweed now that she's getting a good grip on gardening, but the dirt in our backyards is. Pretty sandy. So I think this might be the best fit but god it's hard to find for a decent price.

#milkweed#sandhill milkweed#pinewoods milkweed#gardening#monarch butterflies#ani rambles#out of queue#growing from seed#I swear to god if someone even told me a place nearby that had it growing I'd fuckin drive just to TRY and get some pods at this rate

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Husband: intensely scared of flying insects including but not limited to butterflies and bees

Also husband: we need to plant flowers to make the garden pretty

#say no more my love time to get all the pretty flowers for the butterflies and bees#i got bee balm and coneflower which are both native (bee balm technically not in illinois i guess the range has recently increased to here)#i want to get some milkweed seeds for the monarchs too#and I'm gonna try and transplant some weedy flowers into the garden to trick husband into accepting them#i feel kimda bad because lillies are one of my fave flowers but my MIL is allergic...and the whole front garden is just lillies

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

some times i see people talking about the Earth and climate change saying things like "now i know it is difficult to deal with utter hopelessness, terror, and visiting the thoughts of death"

and it's like wow I am so deeply sorry about the suffering. but...concern. Concern. Tell me, am I missing something important? Why do I feel a sense of hope for our planet? Am I a lonely fool? Have I been consumed by naïveté and misguided optimism?

That would be weird. It feels weird. It feels like I would be well suited to despair. My natural temperament is Mortal Terror making my body crushed for a thousand years at the bottom of the deepest trenches of the ocean. I've thought before "I can't live any more. This exceeds the tensile strength of the human spirit."

And then? After irreversible catastrophic failure of the soul, there is...what?

We try to imagine the future where we fight to save our home and it is very painful. The resistance feels so small and the machine of death feels so vast. But something's missing.

Everyone else is missing—the plants, trees, bugs, beasts, and creatures. Hello? Are the other humans seeing this? Nature wants you to know that she is not a princess in a tower. Look! Look at the chaos moving through every cell! Iterating! Adapting! Becoming! Thriving! Watch the pollinators tirelessly at work, observe the mycorrhizal network in the forest floor distributing the rich fruits of decay and photosynthesis for every inhabitant! Pay attention! We belong here too. They feed and shelter us, give us the very air we breathe, and in return we plant and propagate, cull, thin, and burn, shape, trample, till, shepherd and sprout seeds. Our species can look toward the future, to the world of our descendants. We can call every plant and animal by name and teach our children to use and care for them responsibly. We can feel this anger, pain, and grief on behalf of the family of Life, OUR family, and we can love the smallest beetle and the humblest moss.

Look at it! This thing is nothing like me, it does not benefit me, it has no use or purpose for me, but LOOK at it! Look at its intricate structure! Look at the marvelousness of its behaviors and biological functions! Look at its uniqueness throughout the whole universe! Look at it, and see its infinite value!

I saved a baby tree from the scorching hot gravel of a parking lot. I watched it grow and thrive in the hands of its caretaker. Many more followed, trees and herbs and flowers, rescued and carefully placed in cups and old tubs that once held yogurt and sour cream. This is so strange, I thought. They're everywhere, offering themselves for free, and no one thinks to take them. Everyone thinks transplanting a tree is hard and that nothing grows on the edge of the pavement but weeds. But it's so easy??? This is weird. Plant Nurseries Hate Her: Get Free Plants With This One Weird Trick.

I protected an old barren garden patch where nothing had thrived from being mowed and weed-whacked, and transplanted little plants that I found. I marveled at the bees that came. Chicory bloomed, then asters and goldenrod. I shed actual tears over a spicebush swallowtail. I ordered some milkweed from the internet, and the monarchs came for them. Less then twenty-five bucks for a divine experience like this. Wow, everyone else really needs to know!

I started volunteering at a nature center, and was allowed to transplant flowers where they sprouted in inopportune locations. I collected tons of seeds all fall and winter long.

There is much, much more, all of it bigger than I ever would have imagined. But this spring there were more birds, in number and in species, than I'd ever seen in my back yard before. Chickadees, swallows, finches, nuthatches, jays, cardinals, warblers, sparrows, woodpeckers of every kind...I remembered just a couple years prior when all I ever saw out there was a couple grackles or starlings or robins, with the occasional sparrow. Those birds come in flocks rather than couples now. And then the bumblebee arrived. An American bumblebee, endangered now, a queen. For a few days she was always out there, would fly out and buzz around me when I came out to tend to my now-innumerable plants. It's nesting time for them. She chose this place I was creating. She saw that this place would take care of her.

A week ago, I discovered wild strawberries growing in my Mamaw's driveway. I found lyreleaf sage growing beside a gravel road. I've become a master of transplanting; I took several of each home. Yesterday, I saw a tiny, metallic blue bee, an Osmia mason bee. Today, I saw an oriole and a strange, very fancy fly. I see something new almost every day. Every day I am being irreversibly changed as a person. How did I ever fail to see how much this matters?

I said I feel hope...do I feel it? I don't think it's a feeling, I think it's a practice. It's being part of our communities and our ecosystems. Nature's interconnectedness is both reality and example: to survive, we take care of one another. And when one member of the community helps another thrive, it creates a cascade that increases the thriving of all. Just by existing, you help us all survive.

You can only take care of so many plants before you have to give some away. You can only hold so much knowledge before you have to give it away. I gave seeds to a dozen different flowers to my next-door neighbor and she invited me inside and wouldn't let me leave without food, and we talked about plants and trees. A family friend lets me have goats' milk and heirloom vegetables in exchange for help around the farm, and I listen to him talk about trees, bugs, and soil and learn so much I feel like I'm about to explode from knowledge.

Being a caretaker is unavoidably a community-oriented, community-forming thing. You can't grow plants all by yourself. Your garden will make too many tomatoes. Share them. Your milkweed will make hundreds and hundreds of seeds. Spread them. Wild blackberries invite you to take and eat. Your lonely retired neighbor invites you to talk and keep her company. Once you grow delicious fruits or little oak trees, you always have a reason to greet someone and say, "Look, it is a gift!"

We're not alone. We are not separate. We take care of each other. Every species, every individual. A single action of caretaking creates a cascade effect of thriving. A single unapologetic love for a creature creates a blossom of curiosity and fascination in everyone surrounding. It's so powerful.

As my chemical romance says "I am not afraid to keep on living"

#nature#community#plants#gardening#you are not separate from every other thing#the wonders#caretaking#plantarchy

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Butterfly (Danaus gilippus), male, family Nymphalidae, Boca Raton, Florida, USA

Poisonous.

Just like the Monarch butterfly, of the same genus, the Queen is toxic, as the caterpillars also feed on Milkweed (Asclepias spp.).

photograph by Alan (@peleides)

#butterfly#milkweed butterfly#danaus#nymphalidae#lepidoptera#insect#entomology#aniamls#nature#north america

407 notes

·

View notes

Text

breaking open dried milkweed stalks to collect their bast fibers.

i pounded them with a makeshift billet against a smooth surface to break them similar to how ive broken brambles before, and then snapped the pith in order to get only the outer fibers.

At this point i had a bunch of the papery skins attaching all the fibers together, like the image just below. But peeling them off is both inefficient and can lead to breaking

in order to get rid of the outer layer, i rubbed/rolled them vigorously between the palms of my hands, breaking it into flakes that either fell off or can be combed/carded out. it was too difficult to film but basically the same as making a friction fire (although easier for sure).

At this point i had a handful of fibers, still long but in need of combing. I have a fine-toothed comb i use for a lot of fiber stuff, and ran that through it

I'll leave the sound on this one because it's an interesting auditory experience, some might like it some might hate it. Note, be prepared to sweep afterwards!

i used to worry about combing stuff like this too much, and i sort of still am, but its important to remember that what im removing are fibers that would otherwise be too short or fragile to include in a refined long-fiber bundle. What im going for is a line flax/fluff flax-like combo; aka i comb out the short fibers and then i have a bundle of extra long ones to work with!

the result is two bundles of different textures and potential

i made a little test string with the "line" milkweed, but i have yet to do anything more with it

as for the fluff, i carded it out!

i made it into a rolag that i then spun up on my tiny spindle

I quite like it. It definitely reminds me of flax/linen, which makes sense since it's also a bast fiber. Milkweed is often known for being extremely strong; i've heard from a fiber class instructor that you can tow a car with a finger-sized rope of it

I don't know exactly what kind of milkweed this is , but i've heard swamp milkweed is top of the class for fiber. orange butterflyweed is a bit weaker than this one (which might be swamp, might not)

(Also note, if you plant milkweeds, don't plant tropical milkweed outside of its native range! it's not as good as the native ones and can even increase disease in monarchs since it doesnt die back in warm winters)

anyways, have a lil monarch caterpillar!

#crafts#fiber arts#cordage#natural fibers#milkweed#bast fibers#nature#earth skills#drop spindle#handspinning

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

what are some things we can do to make the world better?

Gosh, this is a big question. It's also definitely something that's been on my mind for a long, long time. I mean, honestly, how could it not be?

I'm not gonna be able to provide any revolutionary, mind bending answers on this. I'm honestly something more akin to a coward, if anything--I'm not gonna be able to recommend going to protests or rebel action without being a huge hypocrite.

I guess what I did is pick a couple of topics to try my best to learn as much about as possible, so I can know what I can do to help, and then try to do as much of that stuff as possible. So in my case right now its gardening. I basically went 'oh? Butterflies and bees and pollinators are at risk due to habitat loss? Is there anything I can do about it?' Learned about what I could do about it (start a garden, grow certain plants, avoid certain practices like using pesticides and herbicides in said garden, etc.), and then did as much of that stuff as is reasonable for me. And then I also shared what I was doing with other people, and encouraged and helped them do it too if they're interested.

Is my rinky dink mismatched chaotic pollinator garden changing the world? Making the whole entire place better? Not necessarily. Maybe it's making the world a bit better for the pollinators that stop by though, and if I can convince more and more people to start pollinator gardens then it can help more pollinators. I bounced off from pollinator gardening to grow vegetables too, which I can then share with my community (donating to food banks/community fridges, or just offering some to the neighbors) which can definitely help as well.

You can use this process in other aspects too. Monarchs and milkweeds is what caught my eye and drew me to pollinator gardening, but maybe it just doesn't hit for you. Maybe you're more interested in fish, or ecosystems in rivers and streams. You can look into ways to help, and maybe then you'll get into cleaning riverbanks and such. Or maybe you're moreso interested in something like food scarcity and food deserts, and you can then launch into making community gardens or a system of community fridges and harrassing legislators calling your local representatives to back initiatives that will help. I think asking yourself 'what can I do about abcxyz', learning about it, and then doing what you can is definitely a good place to start. And maybe what you learn will lead you to going to things like protests and doing rebellious actions--in which case that's fantastic! The world needs a lot more people who are a lot braver than the woman behind this Tumblr curtain. Or maybe it won't--and that's okay too. We can do what we can together.

Will you change the entire world? Make the whole world better? Probably not, and I probably won't either. I don't think one person alone can change the world. But we can improve the worlds of a few creatures in a local area, or make the world better for people in our communities. And I think that's at least worth an effort.

If anyone else wants to chime in, by all means feel free! And if my advice sucks I'm sorry.

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

I remember as a kid in the 80s that these iconic large butterflies were everywhere in our garden, along with swallowtails of several species. It's been so disheartening to see an insect that was so plentiful be on the brink of extinction just a few decades later.

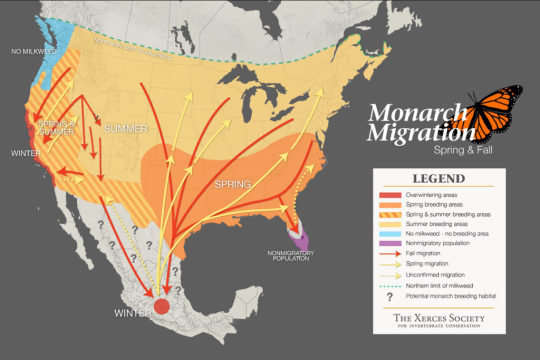

Individually we can only do so much about the effects of anthropogenic climate change, but here are a few things you can do to help monarch butterflies if you're in their range:

--No pesticides! These chemicals don't discriminate, and will harm all sorts of insects, not just the intended targets. In fact, the fewer yard chemicals you use, the better for your local ecosystem.

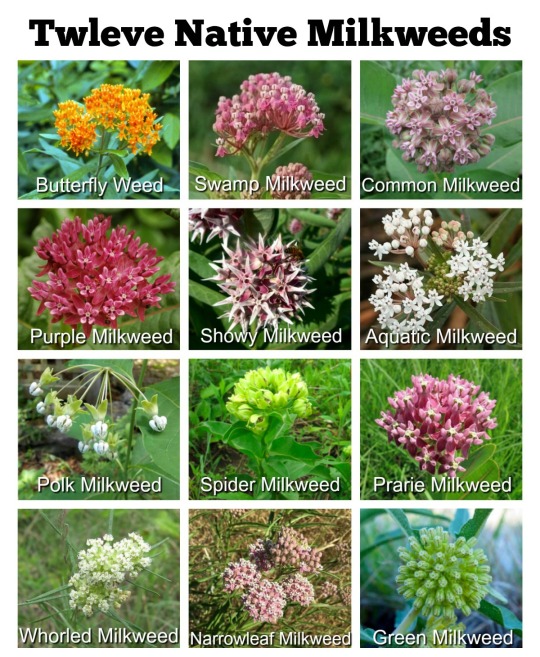

--Plant milkweed that is native to your area; even a few plants in pots count! Live Monarch (US), Monarch Watch (US), and Little Wings (Canada) all have free native milkweed seeds on a limited basis--and they appreciate donations of funds to help pay for more, too. Be aware that a lot of the milkweed on the general market consists of non-native tropical species that host parasites and also bloom late enough that they may cause monarchs to stop migrating south to overwintering grounds.

--Put out a watering station consisting of a shallow dish with a layer of rocks on the bottom and just enough water to not quite cover them so the butterflies can land and safely drink water without falling in.

--Support organizations like the ones mentioned above, and the Xerces Society of Invertebrate Conservation, which all help to protect monarch butterflies and other invertebrates.

#monarch butterflies#Danaus plexippus#butterflies#insects#invertebrates#invertblr#arthropods#endangered species#North America#extinction#environment#environmentalism#conservation#ecology

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

@markedpoint submitted: Been dealing with monarchs eating my milkweed to nothing and found one with much more black than and little to no white. Tempted to see if the butterfly will be as dark in color or not

Monarch caterpillars can be darker if the weather is cooler, presumably because the darker the caterpillar, the more heat they absorb from the sun.

They can also start to turn black and gooey due to something called black death that's actually one term for a bunch of different diseases. So if this one starts oozing liquid out its mouth and anus or starts to look deflated, it's diseased, but otherwise it's just a dark-colored caterpillar. I'm leaning toward the latter for this one.

As far as I know, adult coloration isn't affected by the caterpillar's color. I've never seen something like a dark morph adult.

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tropical Milkweed, Its Problems, and What To Plant Instead

I am writing this to atone for the sins of my past (handing out tropical milkweed cuttings to my friends and teachers before I knew better).

(Also let me make this clear I am Floridian I am writing this from the perspective of someone in the United States if you live in Tropical Milkweed's native range this doesn't apply to you go forth pogchamp)

Look online, on TV, in books, in newspapers, left, right, up, down, anywhere, and you'll see people talking about how planting milkweed is crucial, essential for the survival of monarch butterflies. Milkweed is the only plant that monarch caterpillars can eat as they're growing, and the loss of it in our wild spaces is one of the most direct links to the ecological extinction speedrun of not just monarchs, but dozens of other insects who rely on its abundance of nectar-filled flowers to survive. You'll be urged to run, not walk, to your nearest garden center, buy as much milkweed as you can, and hurry fast to plant it in your gardens and be part of the solution, not the problem. The issue is that, oftentimes, the milkweed you leave the store with is a vibrant red and orange, with pointed green leaves, dozens like it lining the shelves across stores all over the nation...

Tropical milkweed. Scarlet milkweed. Bloodflower. Mexican butterfly weed. Asclepias curassavica. This plant is a being of many names, and our culprit of the hour.

'Culprit? Culprit of what?' Culprit of enticing people to buy it under the guise of helping, only to possibly cause more harm than good.

Let's discuss.

Tropical Milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) is a gorgeous milkweed (especially the yellow variety? ooh, that had me in a grip as a teen) that's easy to obtain--too easy. It lines the shelves of stores like Walmart, Lowe's, Home Depot, and even hundreds and dozens of smaller garden stores, and is sold for reasonably cheap because its quick and easy to grow from seed and eagerly roots from cuttings. It's extremely popular with butterflies too--in many scenarios, Tropical Milkweed will be preferred as host plants over other related species like Butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa), and its also popular with other species of butterfly, bees, and wasps as a nectar source. It lasts well into winter in some areas of the United States, is quick to regrow when cut back, and doesn't die back for periods of the season like some other milkweeds do. It's eager to reseed, creating capsules with tens of dozens of seeds and scattering across the winds with the help of little silky parachutes much like the ones dandelions are known for.

'Ani, what's the problem with that? This all sounds like its great for monarchs!'

See, here's the kickers. In fact, here's several kickers. Here's an entire mollywhopping of kickers.

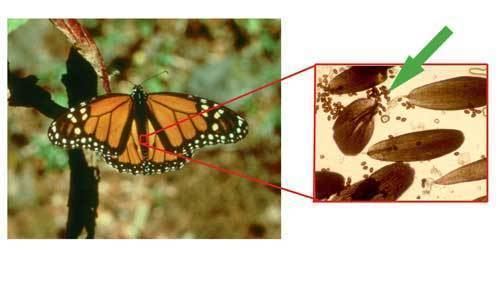

OE Infections

In the temperate areas that it doesn't die back over winter (or even, in some cases, where it doesn't die back during the season like other milkweeds), it can become a host for OE. OE is short for Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, and its a protozoan parasite that can and frequently does infect monarchs. As infected monarchs visit different plants--whether its to drink nectar, to lay eggs, or even just doing a fly-by of the garden--they drop spores from their wings that can then fall onto the leaves, flowers, and even any eggs already on the plant. As caterpillars hatch and begin to eat the plant, they ingest the protozoan, which begins the cycle anew. High OE levels in adult monarchs have been linked to lower migration success, reductions in body mass, lifespan, mating success, and flight ability. And that's if the caterpillars don't succumb prematurely to the infection, or if they're able to even exit their cocoon and fly once they finish pupating--deformed wings are frequently a result after infections. Now, OE is a parasite that's evolved alongside monarchs--and monarchs are usually able to handle an infection just fine, but if they're carrying a high load? That's where the problem lies.

What role does tropical milkweed play in this? Most milkweeds die back after blooming, at least once or even twice per season--and the parasite dies alongside them. As native milkweeds push out fresh foliage, its parasite-free, offering a healthy new buffet for caterpillars. Tropical milkweed... doesn't do that. If nothing's done, (at least in my state of Florida) tropical milkweed will stay fresh and green all the way up until the first real frost hits way in December--and that's if there's a hard frost, when you travel farther south. And during all that time, OE levels are building up on the leaves, so any future caterpillars that feed on this plant are doomed the instant their egg is laid on a leaf.

Its not that it's utterly impossible for a monarch to get infected with OE on any other kind of milkweed--monarchs are known for their traveling habits, and the chances of them happening upon a different milkweed plant than the tropical milkweed in your backyard is pretty high. But whereas native milkweeds die back and essentially reboot their system with fresh, disease-free leaves at least once a season, tropical milkweeds are like downloading a virus onto a USB and then passing it to your friends.

But that's not all, either. Time for kick 2.

Migration Interruption

Sit with me a moment and imagine you're a monarch butterfly. You're hardwired to know that as your food source starts dwindling at home, its time to get a move on and fly on down to the family's vacation home in Mexico for the winter. The buffets shut down, you exit stage left. But on your way to what's essentially a season-long smorgasbord with friends, you find... a buffet is still open. You're supposed to leave when the buffets are shutting down, but this one's up and running, lights are on, and plenty of people are there having fun, so you step in to relax. You'll take your trip later.

Now imagine a bit after you entered that buffet, the staff stuffed the guests into the walk-in freezer, locked the door, turned off all the lights, locked up the building, and left.

That's basically what tropical milkweed being 'evergreen' is doing to monarch butterflies in the fall and winter seasons. In areas up north where it can stay growing far later into the fall/winter months--or worse, in the south, where it can basically be evergreen until a hard frost (if one even happens), it can interrupt the monarchs' iconic migration cycle. They'll stay in place and continue breeding, living life like they aren't supposed to be a country away--until a frost hits, and they're dead in a snap. And if there's not a frost, you're getting a bunch of OE spore-ridden monarchs flying around a bunch of OE spore-ridden milkweed plants that the butterflies who followed the rules and overwintered in Mexico are gonna be returning to. POV you're starting a family in a house so laden with asbestos and black mold that there's practically black dust floating around.

This is already pretty bad. Can it get worse? Absolutely. Kick number 3.

It's Pretty Invasive (in the US)

It's fast growing, its eager to go to seed (so eager that it can flower and produce seed at the same time), its growing all throughout winter--which would be great, if it were native to the United States. Unfortunately, it isn't! As one could imply from the name, Mexican butterfly weed is native to--well--Mexico, as well as the Caribbean, South America, and Central America.

Further North into the states, and it's more of an annual--a plant that lasts maybe a year tops, dies back permanently, and you go buy more next year, or start from seed. Further south? It's a perennial, baby--which means its got even more time to spread its seeds and really thrive in the warmer climates of places like Florida, Texas, California, etc. Not to mention, as climate change makes temperatures rise, places where tropical milkweed is an annual may quickly begin seeing it stand strong all year...

I won't pretend to be a Professional Milkweed Identifier. I'm getting better at it with time, but I'm not a pro. But most of the time I go outside and I go 'oh, that's a milkweed!' its tropical milkweed. I've seen it grow in the sidewalk cracks of a gardening store I go to--its a clean four feet tall, always flowering, always making seeds. Tropical Milkweed is eager to escape the confines of your backyard, or make more plants in your backyard--I started with 5 plants one year, and the next year I had seven, then twelve, and that's just the ones that didn't get mowed over in the seedling stage...

But wait, that's not all! Kick number 4, baby!

Toxic to Monarchs????

According to the Xerces Foundation, emerging research suggests that tropical milkweed may become toxic to monarch caterpillars when exposed to the warmer temperatures associated with climate change.

'What the fuck, I thought milkweed was good for monarchs! How the hell does that happen?!'

All milkweeds produce cardenolides in their sap--a type of steroid that are toxic to most insects (and even people). Milkweeds create it to repel herbivores that would munch on it otherwise--except for milkweed butterflies (Danainae family), like our legendary monarch, as well as the queen and plain tiger butterfly. Larvae eat up milkweed leaves like there's no tomorrow, to stock up on those cardenolides and become toxic to their vertebrate predators--except for a few species that have evolved to become cardenolide-tolerant (black-backed orioles and black-headed grosbeaks). But, when cardenolide concentrations are high enough, it's too strong for even monarch butterflies to withstand--they die because of the very plant that's supposed to give them life. Kinda fucked up. Comparatively, many native species have lower cardenolide levels--and don't immediately go into flux at higher temps like tropical milkweed does.

'Wait, Ani, if there's all these problems with tropical milkweed, why is it sold everywhere?'

Capitalism. The answer is capitalism.

Well, actually, its a bit more complicated than that but it's also still capitalism.

The very same things that make tropical milkweed so invasive and such an issue are what make it so incredibly popular to sell. It's fast growing, and eagerly starts from cuttings as well as from seeds--which is perfect for growing tons of plants in quick and easy batches to send to vendors all over and get a quick profit. It's easy to grow from the home gardener too--its resistant to most diseases, looks gorgeous almost year-round, is quick to return in many areas without even the slightest sign of a die-back, and is popular with monarchs and other pollinators. Want to start a pollinator garden with quick results? Plant milkweed--and when tropical milkweed is all that you see available when you walk into your beloved store, it's what most people are going to get without thinking twice. Not to mention, when you hear it starts quick from cuttings, and you really wanna get your friends and loved ones into pollinator gardening, well... you get well-meaning people sharing invasive plants with their homies, like I did in high school. I've been pollinator gardening for around sixish-sevenish years (I think) and I didn't even catch wind that tropical milkweed was invasive until three years in! To say I was mortified doesn't describe it fully.

'Wait, three years ago? So information about this has been out awhile! Why aren't more places selling native milkweeds by now?! Why are people still buying this invasive milkweed and not native ones?!'

It's capitalism again! But in a different way.

Compared to tropical milkweed, many other milkweeds are a lot more... finnicky to get started, or grow in general. Many of them are a lot slower to germinate, are more prone to failing as seedlings and falling victim to things like 'dampening off' or 'too many aphid' or 'the vibes were wrong.' If they do germinate, they're slower to get to size too--I've grown tropical milkweed from seed in solo cups and gotten something about four inches tall within maybe a month and a half. Some other milkweeds I've grown from seed take about a month and a half to get more than four leaves, or even poke their little green heads out of the dirt. In addition to this, milkweeds have taproots--and some are a lot more friendly to the concept of 'transplanting from a pot to the ground' or 'growing in a pot at all' than others, and tropical milkweed ranks at the top of that list again. Not to mention, their willingness and ability to overwinter in pots--many native milkweeds fail that test, meaning that even if all the resources and efforts are put into getting a milkweed to grow from seed, it won't survive longer than a year in that pot. Considering most milkweeds don't flower until a year or so into their growth, and it's easier to sell plants that are flowering... many plants are a tough sell.

Another reason? Some native milkweeds are way more picky about when they want to make seed pods, or what conditions their seeds want to be grown in. If the seeds are hard to obtain? Good luck growing them in a production greenhouse. Let alone finding seeds for sale to grow them yourself at home--in my hunt for native milkweed species, I've seen packets of ten seeds sold for twenty bucks, packets of 25 seeds sold for anywhere from 50 to 100--meanwhile, you can find dozens if not hundreds of tropical milkweed seeds sold in a pack for maybe a dollar or five.

Let's be real. Producers haven't figured out the magic ticket to pumping out native milkweeds like they have with tropical milkweed--as such, finding native milkweeds for sale is rare, and they're often pricier. And as someone who's been to a native plant sale and found the stands sold out of milkweeds not even 30 minutes into the event--you are likely not the only person wanting native milkweeds. It is war out there in the garden parties.

And that's assuming you've actually found native milkweed for sale! As you get better with milkweed IDs, you'll be able to clearly identify the liars who are telling you they've got something that they don't, but for those who aren't In The Know--if you see a milkweed labeled like a native milkweed and want to buy native milkweed, it might be too late by the time you realize you just got sold tropical milkweed with a mislabel. Whether its on accident or on purpose, it still bites.

I've asked some of my favorite, smaller greenhouses if they'd be willing to start selling native milkweeds. Most of the time I get an exasperated 'I would love to.' But they can only sell what the vendors can produce--so if they can't find a vendor that's selling swamp milkweed (or at least reliably), then they can't give me swamp milkweed when I poke my head in asking if they have any in stock. Of all the times I've gone to dozens of different green houses and gardening events, in different cities even, to see if they have any native milkweeds I've only had success a few times--one small vendor who only has them in stock at events sometimes (and that's if I don't show up late), and the one time I rolled into a not-big-box-but-not-small gardening store near my friends house after being sad that I couldn't find it at a different gardening event. And the one I found there was the last one they had in stock for the next month or two. Until The Vendors get better at growing native milkweeds, your best bet is going to be growing it from seed yourself, getting a start from a friend, or dumb luck at smaller nurseries and events. It's rough out here, friends.

Granted! Keep in mind! That whole last paragraph was personal anecdotes. It's entirely possible that other places' greenhouses have already caught on, and I'm simply in the shadowlands where nobody's selling native milkweeds except for once or twice a year and selling out within 20 minutes of opening their damn booth. And I've heard tell of people getting milkweed popping up willingly in their backyards by doing things as simple as not mowing. I pray you have better luck than I do, young Padawan.

Now, keep in mind, there are people actively working on this. Whether its a team of university scientists dedicating themselves to a project, or a few home-growers in a sunny backyard and a greenhouse doing their damn best to grow native milkweeds as efficiently as possible for themselves and their friends, there are people working on this, sharing advice and communicating online. This isn't some unresolved issue that no one has noticed. We just... aren't at the end post yet. Until then, we scrounge for what we can.

'Oh no, oh god, I have a bunch of tropical milkweed plants in my garden!! Am I a bad person?!?!'

No You Are Not A Bad Person For Growing Tropical Milkweed

And I'm perfectly honest about that. Because I'm here telling you this and I've still got tropical milkweed plants in my backyard. As that one comic once said, about 10,000 people learn something new every day, and unfortunately today that 'new thing' is a bit sad and a bit untimely. In full honesty, oftentimes in my brain I refer to Tropical Milkweed as Starter Milkweed--its what a lot of pollinator gardeners end up starting with, because its just so available! But! There are things that you can do to mitigate the Damage that tropical milkweed can bring to your backyard butterflies.

Step One: Cut back your milkweeds! At least once a year, maybe even twice a year if you want. This will force them to put out new growth, which will be free of OE spores and give monarchs on it a good head start against the Disease. But for sure, for sure, cut your milkweeds back in the fall--once October hits, I go into the backyard and I snip down everything that's tropical milkweed. Usually at this point (at least for me), the milkweeds don't try to grow back again until spring. This is to prevent monarchs from seeing a buffet and getting locked in the freezer.

Step Two: Cut back seed pods! You would not believe how many seed pods milkweed makes. You see those little green footballs? You wanna snip these back ASAP. Even if they're tiny, but especially if they're bit. In peak flower production times, I'll go out there at least once a week and just do a look-back and cut them off. You can even yoink them off with your hands if you're in a rush--just don't get that sap into your eyes. If you do this, you're stopping seed production in its tracks--and don't forget, these plants want nothing more than to split those pods open and unleash a hellfire of flying seeds all over the place. They'll float on air, they'll float on water, they'll do whatever until they land on a prime patch of soil and get started.

If you see these you're a tinge too late. But also still yoink that off and Dispose of it.

Step 3: Don't give cuttings to your friends. It's tempting. If you're raising caterpillars in a little enclosure and see that every time you refresh your cuttings, the old ones have tons of roots and are ready for a little pot of soil and a name tag? Don't. Resist the best you can. Dispose of your cuttings whenever you go in for a trim.

Step 4: Consider replacing them with something else! I know I already went off about just how hard it was to find native milkweeds for sale, how expensive and difficult they can be to grow--but they're not impossible to grow, and putting in the effort could be worth it! Even as I speak, I'm trying to add as many native milkweeds to my garden as possible--and when I've got something that grows reliably in my backyard, I will eagerly rip up my aging tropical milkweed plants and promptly toss them in the bin so i can put a new, better milkweed in its place. Native milkweeds are more likely to be suited to your environment, making it easier to maintain and more welcoming to the pollinators we gardeners want to help. Not to mention, a lot of them are way pettier than tropical milkweed (in my opinion). Do some hunting online to see what's native to your area--your state's extensions office will likely be great for this! You've likely got great variety--the state of Florida has 21 native milkweeds! Who knows how many your state has! (Not me, I am Floridian, and I am already getting dizzy trying to learn about all 21 of our milkweeds).

Conclusion!

Anyone who knows me knows I'm not gonna be the one to discourage someone from starting a garden, especially a pollinator gardener, and especially growing milkweed. But avoid tropical milkweed when you can--the harms it can cause far outweigh the quick satisfaction of a busy garden it can bring. Take some time to select a native plant more suited to your area, give it some friends and some time, and soon you'll have an amazing pollinator garden that'll be teeming with life!

#milkweed#tropical milkweed#asclepias curassavica#asclepias#outdoor gardening#succulents#bloodflower#pollinator garden#pollinator gardening#monarch butterfly#ani rambles#out of queue#what was it three hours ago that I was declaring that I wasn't gonna write up a long research post again?#now here i am at 3:30 am ranting about milkweed with like a dozen sources#granted this is nowhere NEAR as long as the biodiversity saga was BUT STILL#i told myself i was gonna write today... i meant one of my novels NOT RANTING ABOUT MILKWEED#if this post blows up this is gonna go on my wall of 'posts that i thought of on the toilet that got way more popular than I expected'#there's not a lot of posts on that wall maybe 2 or 3 but its weird that its happened that many times already

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metamorphosis

Rating: G

Pairing: Elucien

Word count: ~2,000

TWs: None

Summary: How a butterfly and some reference books led Elain to reconsider the mate she'd been trying so hard to ignore.

Read on AO3!

-

He’d sent her books.

Elain thought it a strange change of strategy at first, until she realized he’d sent books to Feyre as well, tomes on Prythian art history. He’d even sent Nesta a slender copy of a volume on Valkyrie battle strategies. It seemed he had a surplus of books in his new home in the Day Court, where he now resided full time.

Feyre had not given her the details on that particular bout of drama, and Elain had refused to show any interest in the matter, even though it was exactly the sort of gossip she would’ve devoured in her old life. Spite won out against curiosity, but only just.

She’d accepted the books from Feyre without reading the titles and dropped them onto a shelf in her closet–atop the brown jacket whose pockets held enchanted gloves and pearl earrings. Despite her best efforts to glean no information from his latest gifts, she’d not been able to miss the elegant depiction of a butterfly etched into the top book’s cover. That drawing had tickled the dark corner of her mind that wondered about him, wondered what about these particular books had reminded him of her.

He thinks I am simple, she decided, that all I see are pretty flowers, and that I know nothing of their inner workings. He thinks I should learn about butterflies because I don’t know anything about them already.

In the spring, that butterfly resurfaced in her thoughts, when one wholly unlike any she’d seen before floated through her garden. She watched it flit on orange and black wings over rose bushes and between stalks of lavender. It drifted like a leaf on the river, never once landing before it dove behind a hedge and out of sight. Beautiful as Elain’s garden was, it did not offer whatever that butterfly sought, and watching it wander fruitlessly had sent a spear of longing through her chest: longing to provide, to nurture. To be useful in the one domain she was allowed to control.

She hoped the butterfly would return and give her garden another chance; but first, she had to learn what it needed.

That night, Elain peered into her closet. The butterfly book sat on top of The Classification of Soils and A Botanist’s Guide to the Night Court, Volume 1. Carefully, she slid Lepidoptera of the Solar Courts off of the stack.

Thankfully, there were illustrations. She didn’t let herself stop to skim any of the words as she flipped through the pages until she found one that looked promising. The illustrations were not colored, but the black lines and white spots along the wings’ edges matched quite well with what she could recall of her garden visitor. The word Monarch sat in bold script above the illustration, with a descriptive paragraph on the opposite page.

A brush-footed butterfly, orange with black veining, white spots along the edge of the wings, white spots on black body. The black veins on the female will–

Elain blinked and shook her head. She couldn’t read the whole page. That set a dangerous precedent to the book being interesting–it was intolerable enough that it be useful. She instead set to scanning the page for anything about eggs or caterpillars. Luckily, in addition to providing illustrations, the book’s author was also concise.

Host plants are any milkweed varieties native to the solar courts. Females lay eggs on the underside of the milkweed leaf, and larvae feed exclusively on the milkweed until the fifth instar. Larvae prefer to pupate as far from the host plant as possible. Chrysalis is a bright green with gold–

Elain slammed the book shut. She didn’t need to read about the chrysalis. She’d see it for herself. She only needed to find a milkweed plant that was native to the solar courts.

Her gaze drifted to the other books, where A Botanist’s Guide to the Night Court, Volume 1 sat with the silver foiling of its spine shining in the faelights’ glow. Taunting her.

Scowling, Elain stood and placed Lepidoptera of the Solar Courts on her bedside table. As she blew out a long breath, she willed the tension from her shoulders and picked up the other book. Lucien Vanserra could win, just this once. It’s not as though she had to tell him about it.

—

Those varieties of milkweed had turned out to be rather difficult to acquire. Her supplier in Velaris had few seeds and even fewer plants available. Elain cleared out their stock, much to the nursery owner’s surprise. Milkweed was highly uncommon in Velaris gardens, being considered, as its name implied, a weed. But he assured her that she’d have no trouble sowing more seeds come autumn.

As soon as she returned to the river house, she put the three plants in the ground. Two specimens had tall, gangly stalks topped by clusters of pink flowers, while the third was smaller with thin leaves and had not yet begun to bloom. Only an hour after planting, Elain was rewarded with the return of her orange-and-black visitor, who floated directly to the leaves beneath the pink blossoms.

Elain’s fae eyes found the eggs right away, dotting the undersides of the leaves like tiny pearls. Every day, sometimes every few hours, she bent over the plants until her hair nestled in the dirt to peer at those little eggs. At last, she ventured out to the garden one morning to find holes in the leaves where the eggs had been, and dozens of larvae the width of her smallest fingernail and half as long.

She tried to focus on other tasks throughout the garden, to stop herself from spending all her time worrying over the caterpillars; but it was summer, and there were only so many deadheads to prune, only so many leaves to sweep from the stone steps. Some days, when the river house was silent and there was nothing left to water, Elain allowed herself to lay on her stomach on the grass, her chin upon her hands, and watch the caterpillars nibble and creep, allowed herself to feel that swell of pride–that these creatures might not have found a home if not for her.

She did not allow herself that faint flutter of affection, stirring in the pit of her stomach, for the one who’d gifted her the knowledge she’d needed. She stamped it down whenever it threatened.

He couldn’t have known about that butterfly whose name she’d wanted to learn. He couldn’t have known how bugs like that made a garden, gave it blood and breath, just as surely as the soil. That they elevated the flowers to a purpose beyond beauty.

He could not have known, she insisted to herself, even on that day she spotted him on the other side of the windows of Feyre’s solarium. He did not look out to the garden even once as he spoke to her sister, but she knew that golden eye of his saw too much. Could it see even down to the fat, wriggling buds of life on the leaves before her?

It didn’t matter. As long as they were bound to the plants she’d planted, these caterpillars were hers alone. She could claim that much, at least.

As much as she could claim anything in this court.

—

Elain glared at the new plant in its makeshift paper pot, two vines adorned with broad, heart-shaped leaves winding around a wooden post.

It was a clever ploy. Gloves and pearls could be stashed away; gardening books, begrudgingly used before they, too, were shoved into the darkest corner of her closet. But a plant was alive, a gift that she could not, in good conscience, condemn to death by neglect.

Worst of all, it was a climbing vine, and damned if Elain hadn’t been looking for something to train on the garden’s eastern fence.

A tag sticking out of the soil read, Wooly Pipevine. A smaller tag, written in a different, elegant script, stated, host plant to swallowtail butterflies.

Elain folded her arms across her chest and huffed out a sharp breath through her nose.

Beside her, Feyre shifted on her feet. “Do you want me to get rid of it?” Ironic, as she’d been the one to accept it, the one who’d let that red-haired menace into this house to begin with.

“That won’t be necessary.” Elain bent to wrap her arms around the paper pot and, without a glance back at her sister, marched outside.

She grumbled to herself on the arrogance of the fae as she paced the length of the fence in search of a suitable spot. She grumbled more as she dug a hole, as she tossed in fertilizer and packed down the dirt with more force than was necessary. And standing back to observe her work, she grumbled still, on the choice of pipevine, of all things.

“They don’t even have pretty flowers!” she pouted to the plant in question.

Yet there it was again, that flutter of delight trapped inside her ribs; much of it came from the simple joy of a job completed, of new life and growing things. But there was that spark, too: warmth that circled her heart and squeezed it tight, etching upon it the words on that little tag, the words of someone who looked just a bit closer.

Two weeks later, a butterfly in shades of velvet midnight with a trail of black-rimmed suns along its wing drifted through her garden. It passed by roses, morning glories, even the pink and white blossoms of the milkweed, ignoring them all to alight upon a leaf of the pipevine.

—

Lucien looked as if he’d been caught in the middle of an attempted robbery–only he’d brought something into the house instead of taking something away. Elain wished she felt vindicated about catching him in the act, but it was a different sort of emotion tangled inside her chest, sending tremors through her limbs.

He’d brought another plant.

Elain kept her face a haughty mask, raising an eyebrow as she asked, “Passionflower?”

Still no vindication came to her, but she did feel a tad smug at how off-guard she’d put him. He inclined his head, looking suitably cowed. “Yes, my lady.”

“Why?” She forced accusation into that word, more than the curiosity that she’d spent so long swallowing, curiosity that had now grown so large she feared she’d choke on it.

Lucien met her gaze at last, and Elain caught a glimpse in his eye of the vulpine predator her sister had warned her about. That gaze held a danger that did not seek to intimidate or overpower, but to analyze. Dangerous in how much that gaze saw. Dangerous in how it did not feel dangerous at all. “I thought you might be looking for more host plants to add to your garden.”

Elain narrowed her eyes. “Are you well versed in the raising of insects, sir?”

He shifted the plant and its pot into the crook of his left arm. He winced as one of the little vines whipped at his cheek. “Not in the slightest.” Though he angled the plant away, the thin, curling tendril still swayed towards his face. Maybe it thought it had found the sun in his gold eye, or the reddish flakes of pine bark in the other.

Elain squared her shoulders and jerked her chin towards the plant. “It’s a host for the solar fritillary.”

He nodded. He did not look surprised. He’d done research on insect larvae and the plants that nourished them, a subject that he admitted little interest in. What led you to this? What did you see? The questions burned down her throat as she swallowed them. Did you look past the rose blossoms and see the thorns, the grubs, the detritus beneath? But it was too much to ask, too soon to hope.

“Fritillaries are rather plain,” she said instead, a half-truth. Fritillaries were a rusty orange with small streaks of black, but if one looked close enough, they would catch the striking white spots on the undersides of their wings. Had Lucien researched enough to learn that much?

But Lucien tilted his head and gave a smirk that somehow wore the guise of a frown. “I did not realize your garden had such a strict dress code, my lady.”

Elain blinked. She’d expected an empty apology. She’d grown used to being placated, to being offered deference that sounded suspiciously condescending. She did not expect a riposte, nor did she expect the smile that tugged at her lips in response. “Are you good with a shovel, my lord?”

It was a relief to see his eyes widen, to know that at least here, with a vine tickling his face, he did not feel the need to wear a mask, to hide his fear and hope. “I’m afraid I am untrained,” he said.

She turned to open the door to the garden. “Well, if you’re such a quick study on butterflies, I’m sure you can learn about planting.”

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Text is from the Center for Biological Diversity:

For Immediate Release, February 27, 2023

Contact:

Tierra Curry, (928) 522-3681, [email protected]

Rare Milkweed Gains Endangered Species Protection, Critical Habitat

Plant Is Crucial for Migratory Monarch Butterflies in South Texas, Mexico

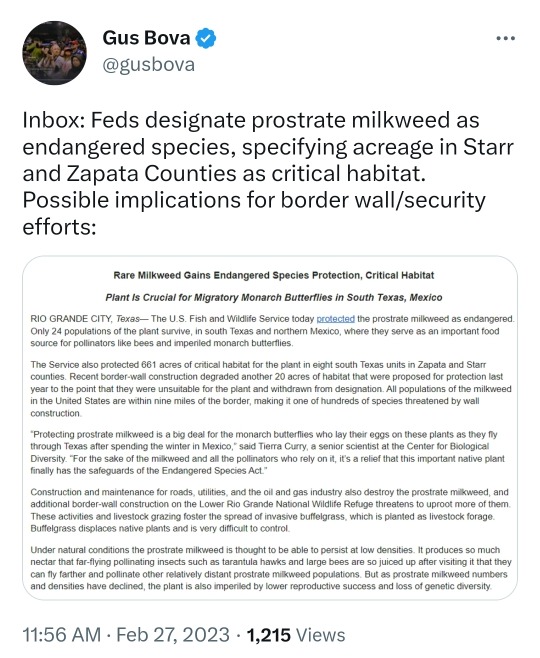

RIO GRANDE CITY, Texas— The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service today protected the prostrate milkweed as endangered. Only 24 populations of the plant survive, in south Texas and northern Mexico, where they serve as an important food source for pollinators like bees and imperiled monarch butterflies.

The Service also protected 661 acres of critical habitat for the plant in eight south Texas units in Zapata and Starr counties. Recent border-wall construction degraded another 20 acres of habitat that were proposed for protection last year to the point that they were unsuitable for the plant and withdrawn from designation. All populations of the milkweed in the United States are within nine miles of the border, making it one of hundreds of species threatened by wall construction.

“Protecting prostrate milkweed is a big deal for the monarch butterflies who lay their eggs on these plants as they fly through Texas after spending the winter in Mexico,” said Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “For the sake of the milkweed and all the pollinators who rely on it, it’s a relief that this important native plant finally has the safeguards of the Endangered Species Act.”

Construction and maintenance for roads, utilities, and the oil and gas industry also destroy the prostrate milkweed, and additional border-wall construction on the Lower Rio Grande National Wildlife Refuge threatens to uproot more of them. These activities and livestock grazing foster the spread of invasive buffelgrass, which is planted as livestock forage. Buffelgrass displaces native plants and is very difficult to control.

Under natural conditions the prostrate milkweed is thought to be able to persist at low densities. It produces so much nectar that far-flying pollinating insects such as tarantula hawks and large bees are so juiced up after visiting it that they can fly farther and pollinate other relatively distant prostrate milkweed populations. But as prostrate milkweed numbers and densities have declined, the plant is also imperiled by lower reproductive success and loss of genetic diversity.

Just 24 populations of prostrate milkweed remain in Starr and Zapata counties in Texas and in Tamaulipas and eastern Nuevo León in Mexico. Nineteen of those populations are rated in low condition, the remaining five are in moderate condition and none are in high condition — indicating acute imperilment.

The Endangered Species Act has been successful in keeping more than 99% of species under its protection from going extinct. But long delays in adding animal and plant species to the endangered list have heightened the perils and made recovery more difficult and expensive. For example, the Service must decide by the end of 2024 whether to protect monarch butterflies as threatened, 10 years after a petition seeking to protect them under the Endangered Species Act was filed.

The prostrate milkweed listing comes in response to a Center lawsuit to gain final decisions on protection for 241 plant and animal species threatened with extinction, including the prostrate milkweed and more than 35 others in Texas. The prostrate milkweed was the subject of a 2007 protection petition by WildEarth Guardians.

The prostrate milkweed’s low and sprawling leaves and stem wilt during droughts. But the plant’s subterranean tuber stays alive and after soaking up moisture from occasional tropical storms sends up stalks and pink and yellow flowers.

175 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do yk of any annoying plants (annoying for an hoa, sterile city planner, in the oh God we've sprayed pesticides on it four times how does it keep growing) I could put into a seed bomb? I know mint can be annoying in a garden but im not sure if its the best thing for the ecosystem. Idk if this is a strange question. I've been researching a bit and ik you're kinda a plant fella on here so I thought I'd ask anyways (south coastal USA, near gulf of Mexico)

Alright so here's the thing:

Seedbombing an area that is heavily maintained and treated with pesticides and herbicides: ranges from pointless to potentially harmful. The toughest plants nature has to offer are the first to show up in disturbed areas, and they don't need human help to get around.

At best, you're not really doing anything, at worst, you're leading to more pesticides and herbicides getting sprayed than before.

Seedbombing an area that might see occasional maintenance but is mostly neglected and ignored: GOOD. GREAT. What you're doing basically is re-introducing extirpated species, which can have a cascade effect on the rest of the surroundings.

Places like this might include the side of a drainage ditch, a roadside, a little empty lot set aside for stormwater drainage, just those forgotten little areas that get weedy.

You have a ton of biodiversity on the coast that isn't present here, so this will be your own quest mostly, but here's some guidelines for what you're looking for:

Native species (please do not spread invasives, and the benefits of non-natives generally are limited)

Suited to the site you want to try seed bombing (wet and soggy areas host plants suited to wetlands, drier areas have different inhabitants)

Herbaceous plants (nothing that could interfere with underground wires or pipes, so no trees or shrubs sorry)

Vigorous self-seeder that spreads by wind (because you want it to spread)

Germinates and blooms the same year (so it can reach the point of producing seeds)

A lot of plants that fit the above criteria will be annuals.

Spring or early summer blooming plants are a good idea, simply because they are more likely to survive to reseed and to be noticed by people who might think they're pretty and want to preserve them.

There are many species of milkweed. Find a few that are native to your area and mix them in. This is because they will attract monarchs, the general public is at least marginally aware of monarchs as endangered, and thus milkweeds will have a protective effect on everything else on the site.

Include a large variety of seeds. Biodiversity, and also higher success rate.

Good luck in your endeavors.

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something like butterflies: the grief nobody wants to talk about

There have been many unique flavors of grief washing over me this past week.

The most unexpected one is the grief that comes with knowing that no matter what I do or where I go, even if I leave the business entirely and never see the inside of another theater…my life is never going to be the same as it was before.

I’ve done a lot of shows in my day, and there is always a deep sense of grief when they close—even when I know the closing date when the rehearsals begin. But the grief was different. The grief was rooted in the banality-yet-relief-yet-restlessness of everything going “back to normal.” In my community theatre days, I would close a show on Sunday, and then wake up at 4am on Monday to go sling espresso at Starbucks, flipping through Backstage (yes, the paper version) on my breaks. On my days off, I’d park (sometimes illegally) by the nearest Metro-North station and make the familiar trek to Grand Central, then to Ripley-Grier or Pearl or Nola (RIP) or the old AEA offices where non-members weren’t allowed to use the bathrooms (today’s kids will never understand) and scurry between holding rooms where my name was on the non-union list for three different EPAs.

In later years, when I had my Equity card and the ability to use the temperamental online signup portal to secure an appointment, I would drive down so I could warm up in the car and search for free (or cheaply metered) parking…and then put my name on two different alternate lists while I waited for my appointment time. The last time I did that was May 2023—mere weeks before we knew for sure that Ohio was going to Broadway.

I don’t need to do that anymore. “In fact,” my agent said, “we’d strongly prefer that you didn’t. You originated a principal role on Broadway. You’re on a different level now.”

Of all the feelings that come with that statement—you’re on a different level now—I never would have expected grief to be one of them. It's not that I miss those things, per se. It's just weird to know that the version of me who did those things is gone.

Something like butterflies.

When I was a kid, my sister and I had a little bug house, and we would carefully capture bugs, observe them, for a while and then set free. One time, we supplied the bug house with milkweed and a climbing stick and captured a monarch caterpillar—and the next thing we knew, it was hanging from the climbing stick as a chrysalis. After a few impatient weeks of eager checking, cracks finally appeared in the cocoon. We gently removed the stick from the bug house, placed it in the sun, and watched in awe as our butterfly hatched.

If you’ve ever seen a butterfly emerging from a cocoon, you know awkward and vulnerable it is after it wrenches its new body and new unused modes of transportation out of the sack of goo that dissolved and then completely transformed its previous body. How must it feel? It's gotta be heckin' weird to unfurl those wet, wrinkled wings, realizing you can flap them, and eventually, when they are dry, realizing—holy poop, I can fly.

I don’t want to overly anthropomorphize a creature whose emotional capacity or long-term memory I can only guess at, but I would imagine that when a butterfly hatches from its cocoon, it probably doesn't miss being a caterpillar. By the same token, I doubt that butterflies look down disdainfully on the caterpillars whose time hasn't quite come yet, or whose time might never come. Perhaps they don’t even have an awareness that they were once caterpillars, or that they are now butterflies—they can’t even see their wings.

But what if they do know? What if they do remember? What if the butterfly remembers its caterpillar life, and recognizes its caterpillar friends, and tries to do all the things it used to do as a caterpillar, and then realizes that it’s never going to be able to relate to the other caterpillars the same way it did when it was one. I wonder if that feels lonely. Or if the butterfly is surprised that it feels lonely.

Unlike the butterfly, I don’t have an instinctual, automatic timeline for my life cycle that tells me when to mate, when to migrate, and when to die. Anything could happen next. I might book another Broadway show before the year is out, or I might not book anything else for years. I might get a different job in the industry, or I might get hired at a bakery as the night baker that nobody ever sees, or I might take my cats and go live in a little cottage off the grid, or I might get hit by a truck (which, come to think of it, does happen to butterflies too).

But no matter what I do or where I go, I’m never not going to be “Ashley Wool, one of Broadway’s original Faces of Autism™ in How to Dance in Ohio” again.

The caterpillar I was before this show came into my life no longer exists, no matter how hard I might try to fit back into the same caterpillar spaces. Like the last time I stayed over at my dad’s house and slept in the built-in twin bed that I claimed for myself at the age of three—before we’d even bought the house—situated romantically under a sloped ceiling that I once covered with stick-on glow-in-the-dark stars. I still love that bed; as long as my dad is alive and owns the house, it will still be there for me to sleep in if I need to. But I don’t quite fit in there anymore.

Of course, as an autistic person, I’m no stranger to not fitting in. But, like most people, I am a stranger to the unexpected grief that accompanies the realization of your wildest dreams. Our society is obsessed with celebrities, and the concept of becoming successful and well-known for doing what we love…and yet, when anyone who has ever been in the public eye doing exactly that, living what we think is our dream, dares to say “actually, this kind of sucks sometimes” we scoff at them.

When Britney Spears sang, "if there's nothing missing in my life, then why do these tears come at night?" we didn't want a real answer. Even 23 years later, after watching the trauma of her conservatorship play out on a worldwide stage and then voraciously devouring her memoir, many of us still say, "yeah, but so what? She's so lucky. She's a star."

Did I sign up for this? Yes, I did. Did I cognitively understand that with success also comes a great influx of people who desperately want to see me fail, or want others to believe that I’ve failed, or find some excuse to discredit my success even if it means inventing one? Also yes. But knowing it and living it are two different things.

I am deeply, gushingly, eternally grateful to everything and everyone that How to Dance in Ohio brought to my life. For as long as I live, I will projectile vomit my gratitude and love for this production and the people attached to it all over the place. Most of all, I will never stop fighting for an industry in which productions and work environments like ours are the rule, and not the once-in-a-generation exception.

But I ask as humbly as I can to please be gentle with me as I figure out how to navigate a future that will forever be shaped by an experience and an identity that only six other people in the history of the world can truly relate to.

All of us are building the planes as we fly them through a dismal, anti-artist late-stage capitalism landscape over thousands of people who still can’t quite believe that we exist—or don't want us to exist.

We are grateful. But also neurotic. And nervous, excited and anxious. But also alive.

But also butterflies.

#how to dance in ohio#broadway#spectrum club 7#musical theatre#actually autistic#htdio#musicals#theatre#grief#good grief#emotions

19 notes

·

View notes