#Jeffrey Feltman

Text

ECCO CHI SONO I TERRORISTI CHE COMPIONO ATTENTATI IN RUSSIA PER CONTO DELL’OCCIDENTE (TERZA PARTE)

Macron/Rotschild l’ultimo interprete dei desideri dei massocapitalisti

Rete Voltaire

“Sotto i nostri occhi” (11/25)

Le due anime della Francia

di Thierry Meyssan

Proseguiamo la pubblicazione a episodi del libro di Thierry Meyssan, Sotto i nostri occhi. In questa puntata la Francia si mostra divisa: il presidente fa il gioco degli anglosassoni, mentre il suo rivale gollista quello del Qatar;…

View On WordPress

#Al Qaida#Angela Merkel#David Cameron#Dominique Strauss-Kahn#Francia#Jeffrey Feltman#Libia#Libyan Information Exchange Mechanism#Muammar Gheddafi#Nicolas Sarkozy#North Atlantic Treaty Organization#Tara Todras-Whitehill

0 notes

Text

" Il 7 febbraio [2014], mentre Barack Obama pontificava sul diritto degli ucraini all’autodeterminazione, è stata pubblicata su YouTube (forse dai Servizi russi) una telefonata intercettata fra [Victoria] Nuland* e Geoffrey Pyatt, ambasciatore americano a Kiev: i due già sanno che Yanukovich cadrà e decidono – non si sa bene a che titolo – chi fra i suoi oppositori dovrà essere premier e ministro del futuro governo. La Nuland confida a Pyatt di aver esposto il suo piano di “pacificazione” dell’Ucraina al sottosegretario per gli Affari politici dell’Onu, Jeffrey Feltman, che è intenzionato a nominare un inviato speciale sul posto d’intesa col vicepresidente americano Joe Biden, ma all’insaputa degli alleati della Nato e dell’Ue. «Sarebbe grande!», esulta la Nuland. Che non gradisce come futuro premier ucraino il capo dell’opposizione, l’ex pugile Vitali Klitschko («Non penso sia una buona idea»): meglio l’uomo delle banche Arseniy Yatsenyuk, che infatti andrà al governo di lì a un mese, mentre Klitschko diventerà sindaco di Kiev come premio di consolazione. Pyatt vorrebbe consultare l’Ue, ma la Nuland gli urla: «Fuck the Eu!» (L’Ue si fotta!). Anche il controverso finanziere ungherese George Soros si vanterà di aver partecipato al casting per il nuovo governo ucraino. La cancelliera tedesca Angela Merkel e il presidente del Consiglio Ue Herman Van Rompuy protestano per le «parole assolutamente inaccettabili» della Nuland. Ma non perché gli Usa decidono il governo e il futuro dell’Ucraina come se fosse una loro colonia. Mosca grida al golpe. Ma anche un alto esponente del battaglione Azov (nome di battaglia “Voland”), nel libro Valhalla Exspress tradotto in Italia nel 2022, ammetterà che «la Ue non ci interessava» e che Euromaidan «non fu una rivoluzione, ma un colpo di Stato». "

* Assistente del segretario di Stato John Kerry per gli Affari europei e asiatici.

---------

Marco Travaglio, Scemi di Guerra. La tragedia dell’Ucraina, la farsa dell’Italia. Un Paese pacifista preso in ostaggio dai NoPax, PaperFIRST (Il Fatto Quotidiano), febbraio 2023¹ [Libro elettronico].

#Marco Travaglio#Scemi di Guerra#Ucraina#Russia#Europa#controinformazione#Volodymyr Zelensky#Vladimir Putin#Angela Merkel#ultranazionalismo#Joe Biden#antifascismo#Unione Europea#imperialismo americano#imperialismo russo#Barack Obama#pace#terrorismo di Stato#Viktor Janukovyč#Victoria Nuland#Geoffrey Pyatt#Jeffrey Feltman#Herman Van Rompuy#nazionalismo#Donbass#Euromaidan#NATO#atlantismo#accordi di Minsk#battaglione Azov

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

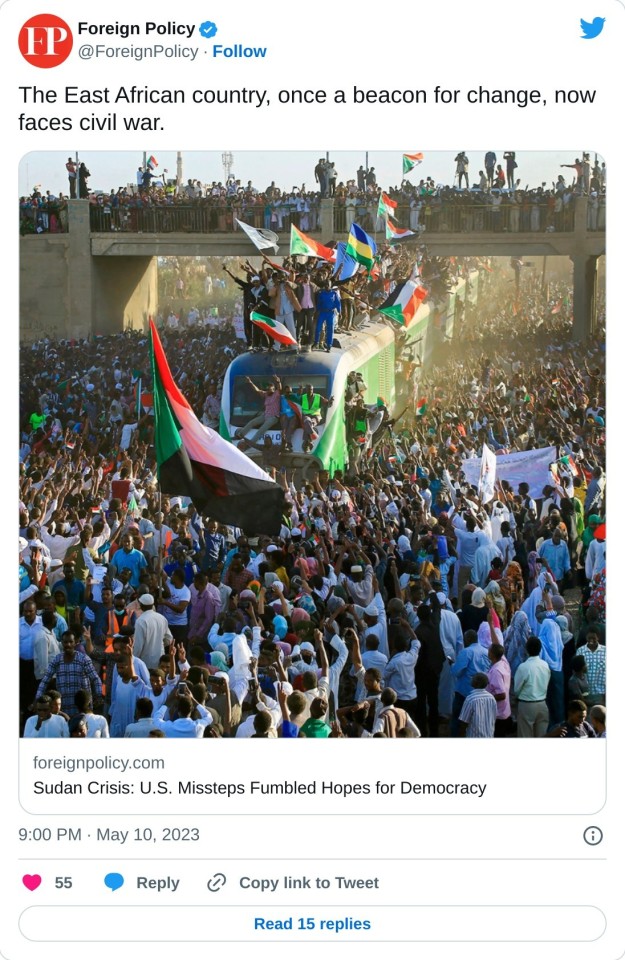

In late October 2021, a top U.S. envoy met with Sudanese military commanders and Sudan’s top civilian leader to shore up the country’s precarious transition toward democracy. The generals assured Jeffrey Feltman, then the U.S. special envoy for the Horn of Africa region, that they were committed to the transition and would not seize power. Feltman departed the Sudanese capital of Khartoum for Washington early on the morning of Oct. 25. En route, he received news from Sudan: Hours after he left, those military leaders had arrested the country’s top civilian leaders and carried out a coup.

For the next 18 months, Washington adopted a series of controversial policy measures to both maintain ties with the new military junta and try to push the East African nation back toward a democratic transition. Months of work led to a new political deal that offered, on paper at least, new hope, and some Biden administration officials felt they were tantalizingly close.

But the deal blew up in the eleventh hour as violence erupted across Khartoum last month between forces controlled by the rival generals, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who leads the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and Mohamed Hamdan “Hemeti” Dagalo, the head of the powerful Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group.

The collapse of Sudan’s democratic transition has led to anger and backlash in Washington among diplomats and aid officials, some of whom feel that the Biden administration’s policies empowered the two generals at the center of the crisis, exacerbated tensions between them as they pushed for a political deal, and shunted aside pro-democracy activists in the process.

“Maybe we couldn’t have prevented a conflict,” said one U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But it’s like we didn’t even try and beyond that just emboldened Hemeti and Burhan by making repeated empty threats and never following through.”

“And all the while,” the official added, “we let the real pro-democracy players just be cast to the side.”

The conflict between Burhan’s and Hemeti’s forces turned Khartoum overnight into a battle zone that put millions of citizens, as well as U.S. and foreign government personnel, in the crossfire of firefights, airstrikes, and mortar attacks. The fighting has pushed Sudan toward the brink of collapse and undermined, perhaps permanently, a Western-funded project to bring democracy to a country beset by autocracy and conflict for half a century.

People run and walk through the streets in front of an armored personnel carrier as fighting in the Sudanese capital of Khartoum continues between Sudan’s army and paramilitary forces on April 27. AFP via Getty Images

As successive rounds of cease-fires fail, Western officials and analysts increasingly fear that the fighting could lead to a full-scale civil war, bringing a new vacuum of instability and chaos to a region already suffering humanitarian crises and along the strategic Red Sea, through which 10 percent of global trade flows.

“The way things are going, Sudan begins to resemble a massive Somalia of the early 1990s on the Red Sea, a total state breakdown, if the fighting doesn’t stop,” said Alexander Rondos, a former European Union envoy for the Horn of Africa.

Interviews with about two dozen current and former Western officials and Sudanese activists close to the negotiations describe a deeply flawed U.S. policy process on brokering talks in Sudan in the run-up to the conflict, monopolized by a select few officials who shut the rest of the interagency team out of key deliberations and stamped out a growing chorus of dissent over the direction of U.S. Sudan policy.

“From the outset, there was a consistent and willful dismissal of views that questioned whether the U.N. talks would be a recipe for success or for failure,” said one former official familiar with the matter. “Those warnings were ignored, and instead the U.S. built a dream palace of a political process that has now crashed down on the people of Sudan.”

Current and former U.S. officials, many of whom spoke on condition of anonymity, said internal warnings of roiling tensions in Khartoum and a possible conflict were dismissed or ignored in Washington, setting the stage for U.S. government personnel to be trapped amid the fighting in various parts of Khartoum with no advance preparations to move them to safety. In Khartoum, these officials and Sudanese analysts said, the policy was further hampered by an embassy that was for years understaffed and out of its depth, without even an ambassador for much of the crucial period.

A woman inside her house protects her face from tear gas in the Abbasiya neighborhood of Omdurman, Sudan, on Nov. 13, 2021. Organizations called for civil disobedience and a general strike during demonstrations against the military coup. Abdulmonam Eassa/Getty Images

“We seemed to have lost all institutional memory on Sudan,” said Cameron Hudson, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and former State Department official. “These generals have been lying to us for decades. Anybody who has worked on Sudan has seen this stuff play out time and time and time again.”

The U.S. State Department has sharply disputed these characterizations. “U.S. engagement after the October 2021 military takeover was centered on supporting Sudanese civilian actors in a Sudanese-led process to re-establish a civilian-led transitional government,” a State Department spokesperson said in response.

“The United States did not press for any specific deal but tried to build consensus and put pressure on the key actors to reach agreement on a civilian government to restore a democratic transition,” the spokesperson said and added that those efforts included “near constant diplomacy, often working closely with civilians, to defuse tensions between the SAF and RSF that arose multiple times and again emerged in the days before April 15, 2023,” when the fighting began.

Still, for an administration that has made promoting global democracy a centerpiece of its foreign policy, many government officials who spoke to Foreign Policy contended that Sudan could stand as one of the starkest foreign-policy failures, even in the wake of the successful evacuation of all U.S. government personnel and campaign to help U.S. citizens escape the country.

These officials also fear that the crisis could reverberate well beyond Sudan’s borders if the warring sides don’t agree to a viable cease-fire soon, with the risk of rival foreign powers exacerbating the conflict and transforming it into a proxy war.

Interviews with multiple Sudanese activists and civil society leaders, meanwhile, paint the picture of a pro-democracy movement that has completely lost faith in the United States as a beacon for democracy and supporter of Sudan’s own democratic aspirations. Many spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of their safety as fighting continued in Khartoum.

“Either the U.S. and West properly step up or they just need to fuck off because halfhearted steps and empty threats of sanctions, again and again and again, are doing more harm than good,” said one Sudanese person deeply familiar with the internal negotiations. “Our trust in the U.S. is entirely gone.”

Sudanese protesters cheer on arriving to the town of Atbara from Khartoum on Dec. 19, 2019, to celebrate the first anniversary of the uprising that toppled Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir. Ashraf Shazly/AFP via Getty Images

After a popular pro-democracy uprising ousted longtime dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019 and set the stage for Sudan to rejoin the international community after decades as an international pariah, the United States invested countless diplomatic resources and hundreds of millions of dollars in Sudan’s democratic transition.

Sudan seemed poised to be a success story. A popular uprising, led in many ways by Sudanese women, had ousted one of the world’s most notorious dictators. U.S. President Joe Biden in a major U.N. speech in September 2021 denounced the global rise of autocracy and touted Sudan as one of the most compelling contrasts to that trend worldwide after the 2019 revolution. In Sudan, he said, there was proof that “the democratic world is everywhere.”

Just a month later, Burhan and Hemeti orchestrated their coup. Afterward, the Biden administration froze some $700 million in U.S. funds to aid in the democratic transition and, over a year later, issued visa restrictions on “any current or former Sudanese officials or other individuals believed to be responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the democratic transition in Sudan.” The World Bank and International Monetary Fund also froze $6 billion in financial assistance.

But some U.S. diplomats felt that didn’t go far enough and none of those reprisals would directly affect Burhan or Hemeti. A fierce internal debate unfolded. Some officials argued that Washington needed to roll out punishing sanctions against Burhan and Hemeti to bring them to heel and show support for pro-democracy activists. Other officials, including Assistant Secretary of State Molly Phee—Biden’s top envoy for Africa—argued that sanctions wouldn’t be effective and might undermine U.S. influence with Burhan and Hemeti as they sought to bring them back to the negotiating table.

“There was the right thing to do, to show the Sudanese people we were all-in on democracy, to punish Hemeti and Burhan for this blatant coup, and then there was the wrong and slightly more expedient thing to do, [to] just keep working with them after some stern finger-wagging,” said one U.S. official involved in the process. “We chose door number two.”

Jeffrey Feltman, the U.S. special envoy for the Horn of Africa, leaves after meeting with Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok in Khartoum on Sept. 29, 2021. Ashraf Shazly/AFP via Getty Images

Feltman, the former U.S. envoy, said he advocated for sanctioning Burhan and Hemeti during his time in government but in hindsight wasn’t sure if it could have prevented the conflict. “Do I think sanctions ultimately would have prevented them from eventually taking 46 million people of Sudan hostage because of their personal lusts for power? No.”

There were other complicating issues as well. Senior Biden administration officials working on Africa policy were consumed by the war in neighboring Ethiopia, where an estimated 200,000 to 600,000 people died during a bloody conflict in the country’s northern Tigray region. And the U.S. Embassy in Khartoum was understaffed and unable to come to grips with the situation; a full-time U.S. ambassador wouldn’t arrive until three years after Bashir’s ouster. During this time, officials say, Phee took direct charge over U.S. policy on Sudan.

Phee worked closely with a U.S. Agency for International Development official detailed to the State Department, Danny Fullerton, in Khartoum to negotiate directly with Burhan and Hemeti and bring them to the table for a new political deal.

“The embassy was just very beleaguered, with a real shortage of skilled or enough political officers, and both the chargés d’affaires and later the ambassador when he got there were very frustrated with a lack of support from Washington,” said one American familiar with internal embassy dynamics. “It was a group that was out of its depth, overly busy, and, frankly, not as well connected as it should’ve been with the right people in Sudan’s pro-democracy communities.”

This official said severe embassy staffing shortages, detailed in a State Department watchdog report on the embassy published in March, and leadership issues contributed to difficulties in hashing out negotiations with Burhan and Hemeti. But other current and former officials dispute that, insisting that the State Department can still make deals with high-level involvement from officials in Washington, even with an understaffed embassy.

Five current and former U.S. officials and two Sudanese activists familiar with the negotiations said that before the U.S. ambassador came to Khartoum in late 2022, U.S. officials involved in the negotiations with Hemeti and Burhan didn’t do enough to incorporate Sudan’s pro-democracy resistance committees into deliberations on a new political deal with the two generals, nor did they heed warnings about the inherent risks and flaws in a new deal.

A Sudanese woman chants slogans and waves a national flag during a demonstration demanding a civilian body to lead the transition to democracy outside the army headquarters in Khartoum on April 12, 2019. Ashraf Shazly/AFP via Getty Images

These officials said there was mounting dissent in Washington over the trajectory of U.S. policy but that Phee dismissed other policy options, including threatening Hemeti or Burhan with sanctions or other forms of pressure or incorporating Sudan’s pro-democracy groups into the political negotiations. The State Department watchdog report also noted that the deputy chief of mission in Khartoum “at times remained focused on her predetermined course of action and did not consider alternatives offered by staff”—though the report did not address whether this had any affect on U.S. policy.

The State Department spokesperson, however, sharply disputed these characterizations: “While we cannot comment on internal policy deliberations, State Department leaders carefully considered policy proposals and different opinions on our policy on Sudan and did not dismiss or stamp out any dissent.”

All the while, Burhan and Hemeti sought to expand their own power and influence across Sudan, currying favor with foreign powers and setting the stage for a growing rivalry that would later ignite a deadly conflict. Burhan found backers in neighboring Egypt. Hemeti courted the United Arab Emirates and Russia and began deepening ties between the RSF and the Wagner Group, a shadowy Russian mercenary outfit widely reported to be responsible for war crimes in other parts of Africa and in Ukraine. Hemeti, implicated in widespread atrocities in Sudan’s Darfur conflict that broke out in 2003, launched a coordinated public relations campaign to try to transform himself into a statesman on the world stage in what was seen as a political charm offensive and challenge to Burhan’s rule.

Hemeti visited Moscow on Feb. 23, 2022, on the eve of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, to discuss the possible opening of a Russian port on Sudan’s coast along the strategic trade routes in the Red Sea. Some U.S. officials who had been pushing for sanctioning Hemeti believed his brazen visit to Moscow would finally convince top decision-makers to finally pull the trigger on a major new tranche of sanctions. The sanctions never came.

Around that time, at least one memo was written and circulated within the State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs warning of the risks of current U.S. policy on Sudan and listing potential scenarios that could emerge from the rivalry between Burhan and Hemeti, including those tensions erupting into a full-scale conflict. The memo, described in broad terms by several congressional aides and former officials familiar with it, was meant to go to U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s desk, but the draft was heavily edited, watered down, and never passed out of the bureau, those people said. “Still, the State Department leaders can’t say they weren’t warned,” one former official said.

Human rights advocates have also criticized the Biden administration’s approach to Sudan in the months leading up to the eruption of violence in April. “By repeatedly failing to hold abusive leaders accountable or making clear, through concrete measures, that abusive behavior would not be condoned, Sudan’s Western partners sent these generals the signal that they can continue holding the country at a gunpoint with almost no consequences,” said Mohamed Osman, an expert on the region at Human Rights Watch.

During this time, Sudanese activists became increasingly disenchanted with the U.S. approach to Sudan. “There was no meaningful commitment that we’d ever seen from either [Burhan or Hemeti], and that was all put aside and sacrificed effectively at the altar of a political process and a political agreement that was never going to hold and that had very little popular support,” said Kholood Khair, a Sudanese political analyst who followed the negotiations closely.

John Godfrey, the U.S. ambassador to Sudan, delivers a speech in Port Sudan amid the delivery of tons of corn as part of U.S. humanitarian support for the country on Nov. 20, 2022. AFP via Getty Images

In September 2022, John Godfrey, a career U.S. diplomat with experience in the Middle East and North Africa and a background in counterterrorism, landed in Khartoum as the first U.S. ambassador to Sudan in a quarter century. Godfrey, officials said, immediately began trying to make inroads with so-called resistance committees and other civil society organizations that had been the driving force in Sudan’s push for democracy.

“He was beset with the cards that were dealt to him,” the American familiar with the embassy’s internal dynamics said. “He was burning the candle at both ends trying to make this deal happen, even if people back in Washington, outside of Phee and the [Bureau of African Affairs], weren’t giving Sudan much attention or thought.”

Even as Russia’s war in Ukraine and the ongoing conflict in Ethiopia distracted most in Washington, Phee and Godfrey—alongside counterparts including senior diplomats from the United Kingdom, United Nations, African Union, and a regional bloc called the Intergovernmental Authority on Development—pushed to restart Sudan’s transition to civilian rule. An apparent breakthrough came last December, when Sudan’s military leaders and some factions of the country’s pro-democracy forces agreed to a new civilian-led transitional government in a matter of months.

But the Western negotiators acceded to demands by Hemeti and Burhan to cut civil society and pro-democracy activists out of the negotiations, giving the military junta an early win over the weaker civilian groups, officials said. The December agreement also left unresolved one major issue that would soon become an explosive one: plans to incorporate the RSF into the SAF to create one unified military force for the country.

People gather to protest the framework agreement signed by Sudan’s military and civilian leaders, which aims to resolve the country’s governance crisis, in Khartoum on April 6. Mahmoud Hjaj/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

That question fueled more tensions between Burhan and Hemeti in the coming months. Analysts in Khartoum began sounding alarm bells about the roiling tensions that would set the stage for an eruption of violence. The push for the agreement may have exacerbated it.

“There was this absolute desperation to push the final deal over the line to the point of succumbing false hope,” said another person involved in the negotiations.

In Washington, however, plans were underway to celebrate the new transitional government the second the agreement was signed. The embassy continued arranging meetings with Hemeti and Burhan and conducting routine embassy business; an American rock band played a festival in March as part of a State Department public diplomacy tour.

The business-as-usual approach belied the tensions in Khartoum. A signing ceremony for the deal was delayed and then delayed again. Burhan and Hemeti were amassing forces around Khartoum. Some low-level U.S. diplomats and Sudanese civilian negotiators began more explicitly warning their friends and colleagues back in Washington through informal back channels that a conflict seemed imminent.

“People were calling around, saying, ‘You’ve got to pass up these messages to everyone you know in D.C. that there could really be a war, it doesn’t feel like the international community is taking us seriously’” said the American familiar with internal embassy dynamics.

Activists demonstrate in front of the White House in Washington on April 29, calling on the United States to intervene to stop the fighting in Sudan. Daniel Slim/AFP via Getty Images

Top officials in Washington either downplayed or misinterpreted these warning signs, according to six officials and congressional aides familiar with the matter. It wasn’t the first time that Burhan and Hemeti had amassed forces around Khartoum, nor the first time that U.S. interlocutors had to step in to help calm the tensions.

Godfrey and his counterpart from London, Giles Lever, who played key roles in shepherding the December deal to the finish line, left the country on separate vacations by early April, a sign that Washington felt the deal was all but done. Back in Washington, after Burhan and Hemeti signed the agreement, the State Department sent word to Congress that it wanted to ready $330 million in funds to aid Sudan’s democratic transition, according to three congressional aides and officials familiar with the matter. Those officials said the department was drafting a carrot-and-stick plan for Sudan, with the millions of dollars of funding the carrot and new sanctions authorizations a hefty stick.

The State Department had a long-standing Level 4 travel advisory for Sudan, recommending that U.S. citizens “do not travel” there, and sent out one additional security alert, on April 13, advising citizens to avoid Karima in northern Sudan, and barring U.S. government personnel from leaving Khartoum, in light of the “increased presence of security forces.” The United States didn’t issue a broad travel warning urging citizens to leave via commercial air travel, consolidate U.S. government personnel inside Khartoum in the event of a crisis, or order a departure of nonessential personnel as tensions between Burhan and Hemeti reached a boiling point.

“We’re all really questioning why we didn’t do more to prepare for the worst-case scenario,” a third U.S. official said.

Drone footage shows clouds of black smoke over Bahri, also known as Khartoum North, outside Sudan’s capital, in a May 1 video obtained by Reuters.Third-party video via Reuters

On April 15, the tensions between Hemeti and Burhan finally boiled over. The RSF launched what appeared to be a coordinated series of attacks on SAF bases and hammered Khartoum International Airport with gunfire and missiles—effectively cutting off the only viable means of escape in a densely populated city that is hundreds of miles from the coast or nearest border.

At once, the city of some 5 million people became a battle zone. The U.S. Embassy began working frantically to consolidate all its personnel and their families in several key locations. Godfrey, the U.S. ambassador, had rushed back to Khartoum, cutting his vacation short, just before the fighting erupted. RSF fighters carried out wholesale looting and assaults, and SAF troops began bombing sites around Khartoum. RSF fighters assaulted the EU’s ambassador in Khartoum, Aidan O’Hara, and in various other instances reportedly fired on, briefly kidnapped, or sexually assaulted U.N. and international organization workers, according to internal U.N. security reports obtained by Foreign Policy.

The White House, State Department, and Defense Department leaped into crisis mode, working around the clock to draft up embassy evacuation plans. On April 22, a contingent of U.S. troops took off from a U.S. base in Djibouti on three Chinook helicopters and, after refueling in Ethiopia, landed in Khartoum to safely evacuate all U.S. government staff and their families. All the while, top U.S. diplomats worked to arrange temporary cease-fires between Burhan and Hemeti to aid civilians and assist those trying to escape.

“None of the foreign diplomatic missions in Khartoum changed their security posture or staffing levels before the outbreak in fighting, and the U.S. embassy was very focused and effective in consolidating its personnel immediately after the war started,” the State Department spokesperson said.

An estimated 16,000 U.S. citizens remained trapped in the city, including many dual U.S.-Sudanese citizens and a smaller number of NGO and aid workers who worked on U.S.-funded humanitarian and development programs. U.S. lawmakers became infuriated that the Biden administration wasn’t doing more to aid in the evacuation of U.S. citizens after the initial outbreak of the conflict, comparing the fiasco to the ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan.

The Saudi-flagged ferry passenger ship Amanah carrying evacuated civilians fleeing violence in Sudan arrives at King Faisal Naval Base in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on April 26. Amer Hilabi/AFP via Getty Images

One resident who stayed in Khartoum was Bushra Ibnauf, a dual U.S.-Sudanese citizen and doctor who had moved back to Khartoum from Iowa. “He had a passion for doing good. I remember him saying, ‘I can be replaced in Iowa, but I can’t be replaced in Sudan,’” said Yasir Elamin, the president of the Sudanese American Physicians Association and a close friend and colleague of Ibnauf. Ibnauf and other doctors ventured out amid gunfights and explosions to provide aid to wounded civilians as the conflict dragged on.

Other Sudanese citizens began trying to make their way out of Khartoum, either by fleeing north to the Egyptian border or on a precarious overland journey to the coast at Port Sudan. “It was hell on earth,” recalled one Sudanese activist who escaped Khartoum. “We only left through the city and all the firefights because we were running out of water. Our choice was either definitely die of thirst or maybe get hit by bullets. It was no choice at all.”

U.S. officials have made brokering a sustainable cease-fire their top priority, but so far no cease-fire has held. Both Burhan and Hemeti have sent negotiators to peace talks in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, coordinated with Washington and Riyadh, but many officials and analysts doubt the talks will lead anywhere after multiple ceasefire attempts failed. On May 4, Biden announced a new executive order granting new legal authorities to impose sanctions on those involved in the violence in Sudan. Some Sudanese analysts doubt sanctions will work.

“The point of sanctions is that it is used as a threat during normal times to prevent bad actors from doing bad things,” said Amgad Fareid Eltayeb, a former assistant chief of staff to Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok before he was ousted from power. “I think right now it’s too little, too late—it’s already a war situation.”

The situation in Khartoum remains dire. “I don’t think so-called safe areas right now are going to be safe for much longer because the aim of the game from both sides seems to be total control of the country,” said Khair, the Sudanese political analyst.

A Sudanese person paints graffiti on a wall during a demonstration in Khartoum on April 14, 2019. Omer Erdem/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

U.S. lawmakers are pressing for new envoys to enter the fray. Rep. Michael McCaul, the Republican chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and his Democratic counterpart, Rep. Gregory Meeks, issued a joint appeal to Biden and the U.N. to appoint new U.S. and U.N. special envoys to Sudan, saying that “[d]irect, sustained, high-level leadership from the United States and United Nations is necessary to stop the fighting from dragging the country into a full-blown civil war and state collapse.”

Many Western officials fear that Sudan could plunge into civil war if the fighting isn’t stopped soon, but it’s also unclear what a viable cease-fire would mean for any hopes of reviving the moribund democratic transition in Sudan. “This is not yet a full-scale civil war, à la Syria, à la Libya,” said Feltman, the former U.S. envoy. “It’s still a fight between two rival forces. Now is the time to arrest it, to stop it before it spirals.”

All the while, the fighting in Khartoum continues. Some U.S. citizens have found additional ways to evacuate, either with the direct assistance of the U.S. government or of other countries.

Others weren’t so lucky. Ibnauf, the Sudanese American doctor who stayed in Khartoum to provide succor to civilians amid the fighting, was stabbed to death by suspected looters in front of his family on April 25.

#Sudan#east africa#khartoum#us fighting#colonialism 2023#emergency evacuations#Sudan Crisis: U.S. Missteps Fumbled Hopes for Democracy#failed us policy#Africa

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Palestinian Authority is hopeless...It suffers from self-inflicted wounds, and Israel has undermined it. As I used to tell Israeli officials, most people treat their security subcontractors better.”

January 31, 2024 | Jeffrey Feltman, The New York Times

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This steady colonization since Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan in 1967 has led to a disastrous impasse. A half-million settlers now live in explosive proximity to three million Palestinians. An inept, feckless and unpopular Palestinian Authority, a voiceless Palestinian people, armed settlers and an Israeli military with an ambiguous mission coexist in the treacherous vacuum of putative but ever-more-inconceivable Palestinian statehood. This impasse has persisted for decades, with spasms of violence — including two intifadas, or Palestinian uprisings, lasting more than a decade in total.

The question today is whether the gyre of slaughter can be broken, a third intifada averted and something new emerge from the West Bank’s disintegration and Israel’s invasion of Gaza. Is there any lingering basis for the “durable, sustainable peace” imagined by Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken, involving the pursuit of a Palestinian state through a drive “to revitalize, to revamp, the Palestinian Authority”?

Any such basis is hard to discern. “The Palestinian Authority is hopeless — there is no there there,” says Jeffrey Feltman, a former United States assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs. “It suffers from self-inflicted wounds, and Israel has undermined it. As I used to tell Israeli officials, most people treat their security subcontractors better.”

Colonized but not annexed by Israel, sliced into nonviable Palestinian pockets of partial self-governance, the West Bank is suspended in the decades-old limbo that a shattered Oslo peace process left behind. This was the so-called status quo, upended by the Hamas attack, that Netanyahu and Mahmoud Abbas, the president of a Palestinian Authority that cooperates with Israel on security, tacitly favored. Abbas enjoyed the wealth and privileges accorded him, his family and his cronies; Netanyahu has made it his life’s work to prevent a two-state outcome. They had the effective backing of the United States, or at least were assured of its inertia.

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank is both brutal and petty. It is a partnership between state and settlers that accomplishes little but breed resentment and radicalization. Anyone forced to live under such an overbearing, cruel, humiliating regime would chafe and rebel. At the same time, Palestinians continue to harbor fantasies about restoring Arab rule from the Jordan to the Mediterranean, something their corrupt leadership, willing to undermine any economic and civic independence lest it threaten Fatah functionaries' fiefdoms, does nothing to discourage. Without a Palestinian popular willingness to focus inward on the development of Palestine rather than the conquest of Israel, how is Israel to withdraw from occupation? Thus we remain mired in an unsustainable-yet-permanent impasse.

This is the situation, described with eloquence, grace, and even-handed realism by Roger Cohen. It's a dark reality from which there seems no possible escape. Future tragedy appears predestined. Inertia has set in, the only motion being the inexorable drift from bloodshed to bloodshed. Yet I must believe there is reason to hope.

Any serious person knows what must be done. The Clinton parameters for a two-state solution remain the only practical roadmap to self-determination, security, and dignity for Jews and Palestinians. Each people has chosen dreadful leadership that compounded misrule by encouraging the worst of the other side. There is great pressure to continue that cycle, but it can and must be broken. The unseating of Netanyahu and the reform of the Palestinian Authority, along with strong international pressure on their successors to make the necessary compromises for peace, would offer new visions and futures for Israel and Palestine. If both publics, seeing those possibilities and experiencing real improvements in their lives, can approach their next political choices with a modicum of wisdom, something beautiful might grow from the horror of the present.

1 note

·

View note

Text

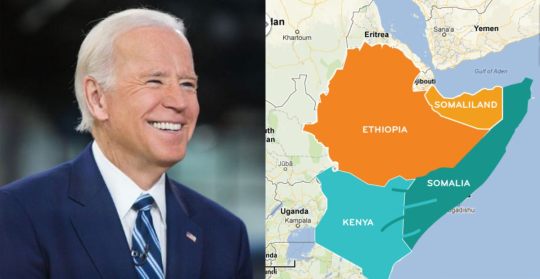

Obama Set Arab Spring, Biden Is Starting Horn Of Africa Spring

In 2010 it was the #MiddleEast. 10 years later, it is now the #HornOfAfrica. #Democrats’ thirst for war has hardly taken a hit, & its puppeteers in the #American deep state are drooling over the #prospect of @POTUS @JoeBiden initiating a #brand-new #conflict which will help them make truckloads of cash.

(more…)

View On WordPress

#Africa#Arab Spring#Barack Obama#China#Djibouti#Eritrea#Ethiopia#Horn of Africa#Jeffrey Feltman#Joe Biden#Revolution#Russia#Sanbeer Singh Ranhotra#Somalia#Somaliland#Sudan#United States

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ethiopie : le vice-Premier ministre a rencontré l'envoyé spécial américain, Jeffrey Feltman

Ethiopie : le vice-Premier ministre a rencontré l’envoyé spécial américain, Jeffrey Feltman

Le vice-Premier ministre éthiopien Demeke Mekonnen a rencontré jeudi l’envoyé spécial américain pour la Corne de l’Afrique, Jeffrey Feltman, pour discuter de l’expansion du conflit dans le nord de l’Ethiopie.

Les forces fidèles au Front populaire de libération du Tigré (TPLF) “continuent de commettre des atrocités dans les régions d’Afar et d’Amhara, créant des dommages humanitaires et…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

🔴 Libano: un anno dopo l'esplosione al porto di Beirut non c'è ancora verità per le vittime. Molto probabilmente perché i responsabili non sono tra i libanesi nemici degli USA.🔴 Ripropongo l'articolo, ancora attuale, di Assad Abukhalil, professore di scienze politiche alla California State University. (...) Gli Stati Uniti hanno uno schema nel soggiogare e dominare i paesi: prima li bombardano, poi esauriscono la popolazione e la fanno morire di fame, e poi ottenengono il dominio totale - o pensano di poterlo ottenere - perché sia in lraq che in Afghanistan non ci sono riusciti. Il governo degli Stati Uniti ha distrutto l'Iraq nella guerra del 1991 e poi gli ha imposto sanzioni crudeli. Le attuali sanzioni contro Iran e Siria sono ancora più crudeli e, come tutte le sanzioni statunitensi, fanno soffrire la gente, mentre la propaganda americana afferma che le sue sanzioni prendono di mira solo i governanti. Per gran parte degli anni '90, gli Stati Uniti hanno raggiunto ciò che fino a quel momento era inimmaginabile: un paese altamente sviluppato è stato bombardato e riportato alla fame e all'era preindustriale. L'Iraq era uno dei paesi più avanzati del Medio Oriente e la sua ricchezza gli ha permesso di costruire un forte esercito che ha infastidito Israele. Israele e gli Stati Uniti non hanno mai permesso a nessun paese arabo, o anche all'Iran, di costruire un forte esercito. Gli Stati Uniti e Israele hanno combattuto contro gli eserciti di Nasser, contro quelli dei vari regimi Ba`th in Siria e Iraq, e contro le forze armate iraniane (non direttamente ma per procura quando gli Stati Uniti hanno sostenuto l'Iraq di Saddam Hussein nella guerra Iran-Iraq). Gli Stati Uniti hanno utilizzato la stessa strategia contro il Libano: Washington ha sponsorizzato e sostenuto la maggior parte della classe dirigente settaria e corrotta in Libano. E quando quei politici corrotti sono stati sotto accusa hanno dei cittadini e dei manifestanti, gli Stati Uniti li hanno protetti. (...) Né il governo degli Stati Uniti né i suoi alleati occidentali ammettono l'ovvio: tra le potenze esterne, gli Stati Uniti esercitano la maggiore influenza in Libano e hanno il controllo parziale o completo dell'esercito libanese, delle forze di sicurezza interna, del settore finanziario, dei servizi segreti e del settore bancario.(...) Jeffrey Feltman, l'ex sottosegretario di Stato USA ed ex ambasciatore degli Stati Uniti in Libano, è stato molto schietto quando ha descritto la campagna contro la corruzione in Libano come una "caccia alle streghe", perché sa che la stragrande maggioranza dei corrotti della classe dirigente del Libano sono burattini degli Stati Uniti e dell'Arabia Saudita. (...) Il Libano rappresenta una grande preoccupazione per USA e Israele: è l'unico paese arabo nel quale esiste una forza militare che ha umiliato Israele sul campo di battaglia (luglio 2006). Per questo, periodicamente vengono annunciate varie sanzioni contro Hezbollah per ricordare ai libanesi che gli Stati Uniti punirebbero l'intera popolazione del Libano per la presenza stessa di Hezbollah. (...) Gli Stati Uniti non si stancheranno di cercare di liberare il Medio Oriente da tutti i nemici di Israele. Per fare ciò, gli Stati Uniti dovrebbero liberare il Medio Oriente da tutta la sua popolazione araba poiché essa nutre sentimenti ostili nei confronti dello stato di occupazione israeliano. Saleh Zaghloul

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heather Cox Richardson

November 8, 2021 (Monday)

The big news of the day is the Biden administration’s ongoing efforts to combat international terrorism and lawlessness through cybersecurity and international cooperation.

Today the Department of Justice, the State Department, and the Treasury Department together announced indictments against two foreign actors for cyberattacks on U.S. companies last August. They announced sanctions against the men, one of whom has been arrested in Poland; they seized $6.1 million in assets from the other. The State Department has offered a $10 million reward for information about other cybercriminals associated with the attack. Treasury noted that ransomware attacks cost the U.S. almost $600 million in the first six months of 2021, and disrupt business and public safety.

The U.S. has also sent Special Envoy Jeffrey Feltman to Ethiopia and neighboring Kenya to urge an end to the deadly civil war in Ethiopia, where rebel forces are close to toppling the government. A horrific humanitarian crisis is in the making there. The U.S. is interested in stopping the fighting not only because of that,

but also because the Ethiopian government has lately tended to stabilize the fragile Somali government. Without that stabilization, Somalia could become a haven for terrorists, and terrorists could extort the global shipping industry.

Meanwhile, it appears that Biden’s big win on Friday, marshaling a bipartisan infrastructure bill through Congress, has made Republicans almost frantic to win back the national narrative. The National Republican Congressional Committee has released an early ad for the 2022 midterm elections titled "Chaos,” which features images of the protests from Trump’s term and falsely suggests they are scenes from Biden’s America.

As Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) and other Republican leaders today attacked the popular Sesame Street character Big Bird today for backing vaccinations—Big Bird has publicly supported vaccines since 1972—they revealed how fully they have become the party of Trump.

Excerpts from a new book by ABC News chief Washington correspondent Jonathan Karl say that Trump was so mad that the party did not fight harder to keep him in office that on January 20, just after he boarded Air Force One to leave Washington, he took a phone call from Ronna McDaniel, the chair of the Republican National Committee, and told her that he was quitting the Republicans to start his own political party.

McDaniel told him that if he did that, the Republicans “would lose forever.” Trump responded: “Exactly.” A witness said he wanted to punish the officials for their refusal to fight harder to overturn the election.Four days later, Trump relented after the RNC made it clear it would stop paying his legal bills and would stop letting him rent out the email list of his 40 million supporters, a list officials believed was worth about $100 million.

Instead of leaving the party, he is rebuilding it in his own image. In Florida, Trump loyalist Roger Stone is threatening to run against Governor Ron DeSantis in 2022 to siphon votes from his reelection bid unless DeSantis promises he won’t challenge Trump for the Republican nomination in 2024.

A long piece in the Washington Post by Michael Kranish today explored how, over the course of his career, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has singlemindedly pursued power, switching his stated principles to their opposites whenever it helped his climb to the top of the Senate. Eventually, in the hope of keeping power, he embraced Trump, even acquitting him for his role in inciting the January 6 insurrection.

The former president is endorsing primary candidates to oust Republicans he thinks were insufficiently loyal. In Georgia, he has backed Herschel Walker, whose ex-wife got a protective order against him after he allegedly threatened to shoot her. In Pennsylvania, Trump has endorsed Sean Parnell, whose wife testified that he choked her and abused their children physically and emotionally.

Although such picks could hurt the Republicans in a general election with the women they desperately need to attract (hence the focus on schools), the chair of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, Rick Scott (R-FL), did not feel comfortable today bucking Trump to comment on whether Parnell was the right candidate to back. Scott said he would focus on whoever won the primary.

The cost of the party’s link to Trumpism is not just potential 2022 voters. In the New York Times today, David Leonhardt outlined how deaths from the novel coronavirus did not reflect politics until after the Republicans made the vaccines political. A death gap between Democrats and Republicans emerged quickly as Republicans shunned the vaccine.

Now, only about 10% of Democrats eligible for the vaccine have refused it, while almost 40% of Republicans have. In October, while about 7.8 people per 100,000 died in counties that voted strongly for Biden, 25 out of every 100,000 died in counties that went the other way. Leonhardt held out hope that both numbers would drop as more people develop immunities and as new antiviral drugs lower death rates everywhere.

And yet, Republicans continue to insist they are attacking the dangerous Democrats. Quite literally. Representative Paul Gosar (R-AZ), who has ties to white supremacists and who has been implicated in the January 6 attack, yesterday posted an anime video in which his face was photoshopped onto a character that killed another character bearing the face of New York Democratic Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The Gosar character also swung swords at a Biden character and fought alongside Representatives Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and Lauren Boebert (R-CO). In response to the outcry about the video, Gosar’s digital director, Jessica Lycos, said: “Everyone needs to relax.”

The House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol is not relaxing. Today it issued six new subpoenas. The subpoenas went to people associated with the “war room” in the Willard Hotel in the days leading up to the events of January 6.

The subpoenas went to William Stepien, the manager of Trump's 2020 campaign which, as an entity, asked states not to certify the results of the election; Trump advisor Jason Miller, who talked of a stolen election even before the election itself; Angela McCallum, an executive assistant to Trump’s 2020 campaign, who apparently left a voicemail for a Michigan state representative pressuring the representative to appoint an alternative slate of electors because of “election fraud”; and Bernard Kerik, former New York City police commissioner, who paid for the hotel rooms in which the plotting occurred.

Another subpoena went to Michael Flynn, who called for Trump to declare martial law and “rerun” the election, and who attended a December 18, 2020, meeting in the Oval Office “during which participants discussed seizing voting machines, declaring a national emergency, invoking certain national security emergency powers, and continuing to spread the false message that the November 2020 election had been tainted by widespread fraud.”

The sixth subpoena went to John Eastman, author of the Eastman memo saying that then–vice president Mike Pence could reject the certified electors from certain states, thus throwing the election to Trump. Eastman was apparently at the Willard Hotel for a key meeting on January 5, and he spoke at the rally on the Ellipse on January 6. None of these people are covered by executive privilege, even if Trump tries to exercise it.

The 2022 midterm elections, scheduled for November 8, 2022, are exactly a year away.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sudan's Prime Minister arrested as military takes power in coup

New Post has been published on https://newscheckz.com/sudans-prime-minister-arrested-as-military-takes-power-in-coup/

Sudan's Prime Minister arrested as military takes power in coup

Sudan’s military seized power Monday, dissolving the transitional government hours after troops arrested the acting prime minister and other officials.

Thousands of people flooded into the streets to protest the coup that threatens the country’s shaky progress toward democracy.

The takeover comes more than two years after protesters forced the ouster of longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir and just weeks before the military was expected to hand the leadership of the council that runs the country over to civilians.

After the early morning arrests of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and other officials, thousands poured into the streets of the capital, Khartoum, and its twin city of Omdurman.

Footage shared online appeared to show protesters blocking streets and setting fire to tires as security forces used tear gas to disperse them.

As plumes of smoke filled the air, protesters could be heard chanting, “The people are stronger, stronger” and “Retreat is not an option!” Videos on social media showed large crowds crossing bridges over the Nile to the center of the capital.

At least 12 protesters were wounded in demonstrations, according to the Sudanese Doctors Committee, which did not give details.

In the afternoon, the head of the military, Gen. Abdel-Fattah Burhan, announced on national TV that he was dissolving the government and the Sovereign Council, a joint military and civilian body created four months after al-Bashir’s ouster to run the country.

Burhan said quarrels among political factions prompted the military to intervene. Tensions have been rising for weeks between civilian and military leaders over Sudan’s course and the pace of the transition to democracy.

The general declared a state of emergency and said the military will appoint a technocratic government to lead the country to elections, set for July 2023. But he made clear the military will remain in charge.

“The Armed Forces will continue completing the democratic transition until the handover of the country’s leadership to a civilian, elected government,” he said.

He added that the country’s constitution would be rewritten and a legislative body would be formed with the participation of “young men and women who made this revolution.”

The Information Ministry, still loyal to the dissolved government, called his speech an “announcement of a seizure of power by military coup.” Sudan’s government says attempted coup has been foiled.

The international community expressed concern over Monday’s developments.

Jeffrey Feltman, the U.S. special envoy to the Horn of Africa, said Washington was “deeply alarmed” by the reports. Feltman met with Sudanese officials over the weekend in an effort to resolve the growing dispute between civilian and military leaders.

EU foreign affairs chief Joseph Borrell tweeted that he’s following events with the “utmost concern.” The U.N. political mission to Sudan called the detentions of government officials “unacceptable.”

The first reports about a possible military takeover began trickling out of Sudan before dawn Monday.

The Information Ministry later confirmed Hamdok and several senior government figures had been arrested and their whereabouts were unknown.

Hamdok’s office denounced the detentions on Facebook as a “complete coup.” It said his wife was also arrested.

Internet access was widely disrupted and the country’s state news channel played patriotic traditional music.

At one point, military forces stormed the offices of Sudan’s state-run television in Omdurman and detained a number of workers, the Information Ministry said.

There have been concerns for sometime that the military might try to take over, and in fact there was a failed coup attempt in September.

Tensions only rose from there, as the country fractured along old lines, with more conservative Islamists who want a military government pitted against those who toppled al-Bashir in protests. In recent days, both camps have taken to the street in demonstrations.

After the September coup attempt, the generals lashed out at civilian members of the transitional power structure and called for the dissolution of Hamdok’s government.

The Sovereign Council is the ultimate decision maker, though the Hamdok government is tasked with running Sudan’s day-to-day affairs.

Burhan, who leads the council, warned in televised comments last month that the military would hand over power only to a government elected by the Sudanese people.

His comments suggested he might not stick to the previously agreed timetable, which called for the council to be led by a military figure for 21 months, followed by a civilian for the following 18 months.

Under that plan, the handover was to take place sometime in November, with the new civilian leader to be chosen by an alliance of unions and political parties that led the uprising against al-Bashir.

Since al-Bashir was forced from power, Sudan has worked to slowly rid itself the international pariah status it held under the autocrat.

The country was removed from the United States’ state supporter of terror list in 2020, opening the door for badly needed foreign loans and investment.

But the country’s economy has struggled with the shock of a number economic reforms called for by international lending institutions.

Sudan has suffered other coups since it gained its independence from Britain and Egypt in 1956. Al-Bashir came to power in 1989 in one such takeover, which removed the country’s last elected government.

Among those detained Monday were senior government figures and political leaders, according to two officials who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to share information with the media.

They include Industry Minister Ibrahim al-Sheikh, Information Minister Hamza Baloul, Minister of Cabinet Affairs Khalid Omer, and Mohammed al-Fiky Suliman, a member of the Sovereign Council, as well as Faisal Mohammed Saleh, a media adviser to Hamdok.

Ayman Khalid, governor of the state containing the capital, was also arrested, according to the official Facebook page of his office.

After news of the arrests spread, the country’s main pro-democracy group and two political parties issued appeals to the Sudanese to take to the streets.

One of the factions, the Communist Party called on workers to go on strike after what it described as a “full military coup” orchestrated by Burhan.

The African Union has called for the release of all Sudanese political leaders including Hamdok.

“Dialogue and consensus is the only relevant path to save the country and its democratic transition,” said Moussa Faki, the head of the AU commission.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which Countries are Middle Powers - And Why are They Important to the Global Order? Part 2

var hupso_services_t=new Array("Twitter","Facebook","Google Plus","Linkedin");var hupso_background_t="#EAF4FF";var hupso_border_t="#66CCFF";var hupso_toolbar_size_t="medium";var hupso_image_folder_url = "";var hupso_url_t="";var hupso_title_t="Which%20Countries%20are%20Middle%20Powers%20-%20And%20Why%20are%20They%20Important%20to%20the%20Global%20Order%3F%20Part%202";

The growing geopolitical tensions in the international system, in particular between the United States and China and also with Russia, have led to a chorus of voices urging on middle powers to greater efforts in maintaining and even strengthening a rules-based order. Roland Paris in a major Chatham House Brief titled: “Can Middle Powers Save the Liberal World Order?” pointed at various urgent calls from international experts:

Gideon Rachman, a Financial Times columnist, has proposed a ‘middle-powers alliance’ to ‘preserve a world based around rules and rights, rather than power and force’. Two eminent American foreign-policy experts, Ivo Daalder and James Lindsay, have also called on US allies to ‘leverage their collective economic and military might to save the liberal world order’.

The urgency and calls for middle power action rose perceptively, of course, with ‘America First’ from the Trump Presidency and from the failure of the leading powers – the United States and China – to organize global governance efforts to tackle the global pandemic. Indeed the global pandemic has seemingly ‘lit a fire’ under experts and officials issuing a rising chorus of calls for greater middle power action in the face of leading power failure. An evident instance is a recent article from Foreign Affairs from our colleague Bruce Jones from Brookings titled:“Can middle powers lead the world out of the pandemic? Because the United States and China have shown that they can’t”.

In Part 1 of this Post series we attempted to identify which states experts were referring to when they issued the call for middle power action. We ended up with a variety of categories. There were the traditional states, Canada, Australia and maybe South Korea and Singapore. There were states that fell within the top 20 economic powers – way too many states but lots of familiar powers. And then there were all those states , identified by Jeffrey Robertson in his insightful article: “Middle-power definitions: confusion reigns supreme” in the Australian Journal of International Affairs (2017. 71(4): 355-370, with an interest in and “capacity (material resources, diplomatic influence, creativity, etc.)resources, diplomatic influence, creativity, etc.) to work proactively in concert with similar states to contribute to the development and strengthening of institutions for the governance of the global commons.” And in fact there seemed to be a bit of a marriage between middle powers and multilateralism in the newly created “Alliance for Multilateralism” created by the foreign ministers of France and Germany that umbrellaed at its creation some 40 states.

The linkage between middle powers, multilateralism and contemporary international policy progress has come to an enhanced focus during the ‘America First’ Trump years. Roland Paris described some of the critical efforts:

It was Canada that undertook the initial diplomacy that led to the forging of the International Criminal Court, and the concept of the ‘responsibility to protect’. It was Australia that led the effort—over initial American opposition—to create a Chemical Weapons Convention. More recently, Japan led the way in creating the TPP-11, to fill the vacuum left when the United States walked away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

But there were other actions that middle powers initiated, and chronicled by Bruce Jones in his FA apiece, “Can Middle Powers Lead the World Out of the Pandemic?” arising from the pandemic and with many of this actions directly related to the pandemic’s spread:

The UK took on the role of leading the Coronavirus Global Response Summit, to raise funds for vaccine development;

the UK, the Dutch and the Swedes took the lead in World Bank efforts to deploy more than $14 billion in surge financing to developing countries;

the UK, the largest donor to GAVI hosted a replenishment conference raising a further $8.8 billion in funding;

Sweden and Spain co-convened a virtual meeting of foreign ministers from every region to help coordinate vaccine production;

Australia helped to broker a critical outcome at the World Health Assembly, generating support for a proposal for an investigation into the sources of the pandemic; and

Norway and Switzerland together with the WHO took the lead in coordinating advanced treatment and vaccine trials (the WHO Solidarity program).

As Paris suggested over these middle power efforts, and more:

If these and other countries worked together in a concerted campaign, they might succeed in slowing the erosion of the current order, and perhaps even strengthen and modernize parts of it. It certainly seems worth trying. After all, if the world’s middle powers do not take on this task, who will?

The method for such action, he believes:

Form should follow function – Each coalition should begin with a small group of states that share a common assessment of the problem at hand and possess the means to do something about it. Once this core group devises a general plan of action, others should be encouraged to join the coalition, contribute to its efforts, and refine its goals. Participation in the coalition should depend on its subject matter and objectives.

The Several Forms of Multilateralism

But what form would these multilateral arrangements take? Now one form of multilateralism that was urged, deriving in part from the emergence of the G20 Leaders Summit in 2008, is the multilateralism built on a ‘shifting coalition of consensus’. This multilateral arrangement was, as you will see, was built on a G20 foundation and was keyed to US actions in this informal institutional setting. As I wrote in ‘Effective Multilateralism’*:

The G20 offered promise of what Stewart Patrick (2010, 358), and others suggested would be a ‘shifting coalition of consensus’[1]: “As the G20 matures and expands its agenda, it has the potential to shake up the geopolitical order, introducing greater flexibility into global diplomacy and transcending the stultifying bloc politics that have too often hamstrung cooperation in formal, treaty based institutions (including the United Nations).” Instead of blocs that emerged frequently in formal institutions and settings generated by structure and politics. Of the era, new ‘shifting coalitions of consensus’ could emerge in this post bipolar world and the coalitions could well vary depending on the issue in this new setting of global governance. The shifting coalitions of consensus were seen as particularly likely to support American efforts to promote collaboration and advance policy making at the global governance level. As Stewart Patrick (2010, 358-9) suggested: “The very size and diversity of the G20 – while not without drawbacks – may inject new dynamism into global governance by facilitating the formation of shifting coalitions of interest. As such, the G20 presents particular strategic advantages for the United States, which will likely remain the indispensable partner for most for most winning coalitions within the new steering group.” What wasn’t anticipated at the time – at the Unipolar Moment’ however – was an ‘America First’ policy that spurned multilateralism and operated largely by transactional and bilateral policy making. And of course, that is exactly what has impacted contemporary multilateralism and is reshaping the global order.

[1] For a further elaboration of the concept of ‘shifting coalitions of consensus’ see the video segment by Colin Bradford. 2013. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTRGmgPgW4U

The shifting coalitions of consensus was conceived to be a moveable arrangement of states furthering global governance effort but it seems built off of US multilateral actions. The concept though, it seems to me, has evolved. This is so not least because of the unilateralism of Trump foreign policy and its distaste for multilateralism. As a result ‘shifting coalitions of consensus’ may no longer envisage US leadership or even US involvement.

It is evident that this form of multilateralism builds off the informal leadership institutions, in this instance the G20. But what if that institutional arrangement is no longer salient to promoting multilateralism in the global order of today. This is the perspective that our colleague Bruce Jones takes with Jeffrey Feltman and Will Moreland in “Competitive Multilateralism: Adapting Institutions to Meet the New Geopolitical Environment���. Jones and his colleagues, take the position that the rise of geopolitics has altered the forms of multilateralism available:

As the world shifts into a period of renewed geopolitical competition, the multilateral order is straining to adapt. Both governments and the institutions that serve them recognize that circumstances are changing, and that multilateralism must change too — but so far, they have not agreed on a way forward.

And further they conclude:

Twenty-first century multilateralism must be fit to its strategic environment. Multilateralism defined by the post-Cold War hallmarks — a focus on utilizing existing, universal institutions to spur cooperation on shared challenges — is insufficient for a world where great-power competition has returned as a driving, structural force in global affairs. Multilateralism’s advocates must revive, and build on, lessons from the Cold War past in order to refurbish these tools for the current climate.

But Jones is not yet done. More recently he has argued, I presume beyond ‘competitive multilateralism’, there is yet another configuration: this ‘democratic multilateralism’. In a recent article with Adam Twardowski titled: “Bolstering democracies in a changing international order: The case for democratic multilateralism” the two argue:

The United States should adopt a strategy we call “democratic multilateralism” — seeking to advance coordination and cooperation among the democracies, but within the contours of the multilateral order. The U.S. — or another leading democracy — should establish a mechanism for tight coordination among the democratic states on both policy and funding for issues of technology, global health, and climate change. Going further, the U.S. could establish a “Partners Council on International Security,” which would operate in parallel to the U.N. Security Council and invite to this Partners Council its most important democratic allies and partners. These mechanisms would bolster multilateralism, not erode it, and they would keep open the necessary mechanisms for coordination with illiberal states on global issues.

Here then is a multilateral world situated, according to Jones and Twardowski, in the growing rivalry of US and China. They two reflect the development of informal multilateral arrangements but not separating from China through the traditional institutions:

Greater coordination among democracies is an obvious part of the answer. The less obvious part is how to arrange it — as a way of subverting the existing arrangements of the multilateral order, or to defend them? Orchestrating tighter coordination of the democracies within the existing mechanisms of the international order is both more likely to attract the needed coalition and can achieve the same goals at lower risk, while simultaneously leaving intact the framework needed for managing global public goods.

Tom Wright at Brookings identified this approach as well in his new piece titled, “Advancing multilateralism in a populist age”. He referred to it as “reinvigorating the free world”. Realistically, however these new arrangements are constructed, it seems to me, without China’s involvement. While the formal institutions maintain Chinese and Russian participation as well, presumably they are no longer ‘the heart’ of multilateral world of action. It appears to be a growing bifurcated global order. And one then needs to ask the question “is that a good thing?” If not, is it a necessary configuration? More on that later.

* “The Possibilities for ‘Effective Multilateralism’ in the Coming Global Order”. Research Memo. December 9, 2020.

Image Credit: Belfercenter.org

Which Countries are Middle Powers – And Why are They Important to the Global Order? Part 2 was originally published on Rising BRICSAM

1 note

·

View note

Text

A New Libya: With ‘Very Little Time Left’

BELOW: The fall of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi seemed to vindicate Hillary Clinton. Then militias refused to disarm, neighbors fanned a civil war, and the Islamic State found refuge.

By Scott Shane and Jo Becker Feb. 27, 2016

It was a grisly start to the new era for Libya, broadcast around the world. The dictator was dragged from the sewer pipe where he was hiding, tossed around by frenzied rebel soldiers, beaten bloody and sodomized with a bayonet. A shaky cellphone video showed the pocked face of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, “the Leader” who had terrified Libyans for four decades, looking frightened and bewildered. He would soon be dead.

The first news reports of Colonel Qaddafi’s capture and killing in October 2011 reached the secretary of state in Kabul, Afghanistan, where she had just sat down for a televised interview. “Wow!” she said, looking at an aide’s BlackBerry before cautiously noting that the report had not yet been confirmed. But Hillary Clinton seemed impatient for a conclusion to the multinational military intervention she had done so much to organize, and in a rare unguarded moment, she dropped her reserve.

“We came, we saw, he died!” she exclaimed.

Two days before, Mrs. Clinton had taken a triumphal tour of the Libyan capital, Tripoli, and for weeks top aides had been circulating a “ticktock” that described her starring role in the events that had led to this moment. The timeline, her top policy aide, Jake Sullivan, wrote, demonstrated Mrs. Clinton’s “leadership/ownership/stewardship of this country’s Libya policy from start to finish.” The memo’s language put her at the center of everything: “HRC announces … HRC directs … HRC travels … HRC engages,” it read.

It was a brag sheet for a cabinet member eyeing a presidential race, and the Clinton team’s eagerness to claim credit for her prompted eye-rolling at the White House and the Pentagon. Some joked that to hear her aides tell it, she had practically called in the airstrikes herself.

But there were plenty of signs that the triumph would be short-lived, that the vacuum left by Colonel Qaddafi’s death invited violence and division.

In fact, on the same August day that Mr. Sullivan had compiled his laudatory memo, the State Department’s top Middle East hand, Jeffrey D. Feltman, had sent a lengthy email with an utterly different tone about what he had seen on his own visit to Libya.

The country’s interim leaders seemed shockingly disengaged, he wrote. Mahmoud Jibril, the acting prime minister, who had helped persuade Mrs. Clinton to back the opposition, was commuting from Qatar, making only “cameo” appearances. A leading rebel general had been assassinated, underscoring the hazard of “revenge killings.” Islamists were moving aggressively to seize power, and members of the anti-Qaddafi coalition, notably Qatar, were financing them.

On a task of the utmost urgency, disarming the militia fighters who had dethroned the dictator but now threatened the nation’s unity, Mr. Feltman reported an alarming lassitude. Mr. Jibril and his associates, he wrote, “tried to avert their eyes” from the problem that militias could pose on “the Day After.”

In short, the well-intentioned men who now nominally ran Libya were relying on “luck, tribal discipline and the ‘gentle character’ of the Libyan people” for a peaceful future. “We will continue to push on this,” he wrote.

In the ensuing months, Mr. Feltman’s memo would prove hauntingly prescient. But Libya’s Western allies, preoccupied by domestic politics and the crisis in Syria, would soon relegate the country to the back burner.

And Mrs. Clinton would be mostly a bystander as the country dissolved into chaos, leading to a civil war that would destabilize the region, fueling the refugee crisis in Europe and allowing the Islamic State to establish a Libyan haven that the United States is now desperately trying to contain.

“Nobody will say it’s too late. No one wants to say it,” said Mahmud Shammam, who served as chief spokesman for the interim government. “But I’m afraid there is very little time left for Libya.”

‘WHAT ELSE CAN YOU DO?’

Media reports referred to Mrs. Clinton’s one brief visit to Libya in October 2011 as a “victory lap,” but the declaration was decidedly premature. Security precautions were extraordinary, with ships positioned off the coast in case an emergency evacuation was needed. As it turned out, there was no violence. But the wild celebratory scenes in the Libyan capital that day actually highlighted the divisions in the new order.

At a hospital, a university and government offices, Mrs. Clinton posed for photos with the Western-educated interim leaders and hailed the promise of democracy.

“I am proud to stand here on the soil of a free Libya,” she declared, standing alongside a beaming Mr. Jibril. “It is a great privilege to see a new future for Libya being born. And indeed, the work ahead is quite challenging, but the Libyan people have demonstrated the resolve and resilience necessary to achieve their goals.”

But everywhere Mrs. Clinton went, there was the other face of the rebellion. Crowds of Kalashnikov-toting fighters — the thuwar, or revolutionaries, as they called themselves — mobbed her motorcade and pushed to glimpse the American celebrity. Mostly they cheered, and Mrs. Clinton remained poised and unrattled, but her security detail watched the pandemonium with white-knuckled concern.

Hillary Clinton’s Legacy in Libya

At the University of Tripoli, students were trampling wall hangings of Colonel Qaddafi that had been pulled to the ground, recalled Harold Koh, the State Department’s top lawyer, who had flown in with Mrs. Clinton on an American military aircraft. One grateful student pointed out the gallows where anti-Qaddafi protesters had been hanged, while others wondered what the United States might do to help win the peace.

“We know what the U.S. can do with bombs,” one student told Mr. Koh. “What else can you do?”

When Mrs. Clinton’s entourage finally departed, Gene A. Cretz, the American ambassador, wrote a relieved email to Cheryl Mills, the secretary of state’s chief of staff. The visit, he wrote, had been “picture perfect given the chaos we labor under in Libya.”

Mrs. Clinton certainly understood how hard the transition to a post-Qaddafi Libya would be. In February, before the allied bombing began, she noted that political change in Egypt had proved tumultuous despite strong institutions.

"So imagine how difficult it will be in a country like Libya,” she had said. “Qaddafi ruled for 42 years by basically destroying all institutions and never even creating an army, so that it could not be used against him.”

Early on, the president’s national security adviser, Tom Donilon, had created a planning group called “Post-Q.” Mrs. Clinton helped organize the Libya Contact Group, a powerhouse collection of countries that had pledged to work for a stable and prosperous future. By early 2012, she had flown to a dozen international meetings on Libya, part of a grueling schedule of official travel in which she kept competitive track of miles traveled and countries visited.

Dennis B. Ross, a veteran Middle East expert at the National Security Council, had argued unsuccessfully for an outside peacekeeping force. But with oil beginning to flow again from Libyan wells, he was pleasantly surprised by how things seemed to be going.

“I had unease that there wasn’t more being done more quickly to create cohesive security forces,” Mr. Ross said. “But the last six months of 2011, there was a fair amount of optimism.”

Even so, the gulf separating the suave English speakers of the interim government from the thuwar was becoming more and more pronounced.

After decades in exile, some leaders were more familiar with American and European universities than with Libyan tribes and the militias that had sprung from them. Others, like Mr. Jibril, were suspect in some quarters because of previous roles in the Qaddafi regime. It was increasingly evident that the ragtag populist army that had actually done the fighting against Colonel Qaddafi was not taking orders from the men in suits who believed they were Libya’s new leaders.

“It should have been clear to anyone,” said Mohammed Ali Abdallah, an opposition member who now heads a leading political party, “that there were clear contradictions in the makeup of the opposition and that unity could not last.”

Jeremy Shapiro, who handled Libya on Mrs. Clinton’s policy staff, said the administration was looking for “the unifier — the Nelson Mandela.” He added: “That was why Jibril was so attractive. We were always saying, ‘This is the guy who can appeal to all the factions.’ What we should have been looking for — but we were never good at playing that game — is a power balance.”

Under the circumstances, Libya’s push for elections by July 2012, nine months after Colonel Qaddafi’s death, appeared to some to be premature. But the schedule fulfilled the opposition’s promises to the West and had the backing of competing factions.

“Suddenly you had people who belonged to political parties,” said Abdurrazag Mukhtar, a member of the interim government who lived in California for many years and is now Libya’s ambassador to Turkey. “The Muslim Brotherhood. Jibril. All these guys thinking, ‘Time for an election.’”

“But we were not ready,” he said. “You needed a road map for security first.”

‘FIERCE LIMITS’

By January 2012, there was an unmistakable drumbeat of trouble.

His popularity sagging, Mr. Jibril had stepped down as transitional prime minister. A prominent Muslim scholar had accused him of guiding the nation toward a “new era of tyranny and dictatorship.” In a deal struck between two powerful militias, he was replaced by Abdurrahim el-Keib, an engineering professor who had taught for years at the University of Alabama.

On Jan. 5, Mrs. Clinton’s old friend and adviser Sidney Blumenthal emailed her with the latest in a series of behind-the-scenes reports on Libya, largely written by a retired C.I.A. officer, Tyler Drumheller, who died last year.