#Grambank

Text

Hello Grambank! A new typological database of 2,467 language varieties

Grambank has been many years in the making, and is now publically available!

The team coded 195 features for 2,467 language varieties, and made this data publically available as part of the Cross-Linguistic Linked Data-project (CLLD). They plan to continue to release new versions with new languages and features in the future.

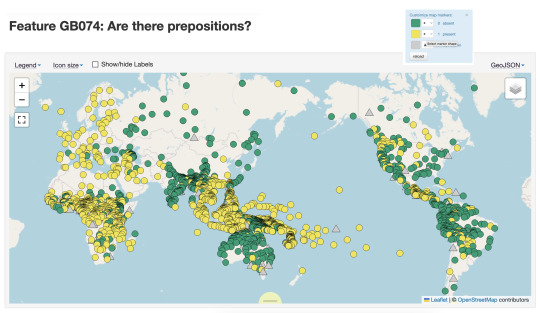

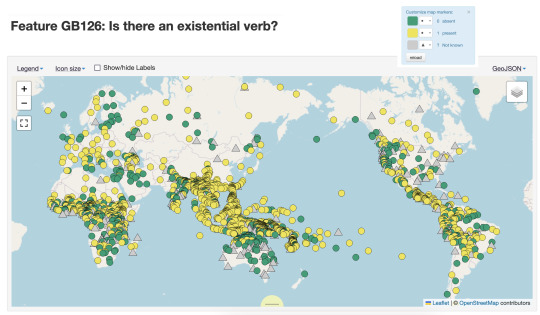

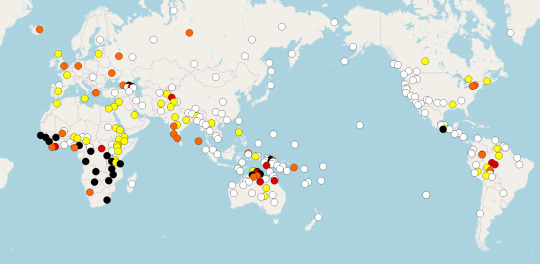

Below are maps for two features I’ve selected that show very different distribution across the world’s languages. The first map codes for whether there are prepositions (in yellow), and we can see really clear clustering of them in Europe, South East Asia and Africa. Languages without prepositions might have postpostions or use some other strategy. The second map shows languages with an existential verb (e.g. there *is* an existential verb, in yellow), we see a different distribution.

What makes Grambank particularly interesting as a user is that there is extensive public documentation of processes and terminology on a companion GitHub site. They also have been very systematic selecting values and coding for them for all the sources that they have. This is a different approach to that taken for the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures (WALS), which has been the go-to resource for the last two decades. In WALS a single author would collate information on a sample of languages for a feature they were interested in, while in Grambank a single coder would add information on all 195 features for a single grammar they were entering data for.

I’m very happy that Lamjung Yolmo is included in the set of languages in Grambank, with coding values taken from my 2016 grammar of the language. Thanks to the transparent approach to coding in this project, you can not only see the values that the coding team assigned, but the pages of the reference work that the information was sourced from.

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fiat Lingua Top 10 for 2023

It's time for the annual Fiat Lingua rewind!

Background: I created Fiat Lingua over ten years ago with the idea that it could be something like the Rutgers Optimality Archive: A place where conlangers could post work that they wanted to showcase, or work that was in progress. We've had tons of contributions over the years, and some standout work I'm really proud of.

Using our fancy statistics program (you know, the free version) we're able to determine the top 10 visited posts for this year (though, note, the numbers for the current year's December post will always be down a little bit, since it didn't have a full month. If you'd like to take a look at it, Carsten Becker did a version of "Silent Night" in his conlang Ayeri!). Here they are!

NUMBER 10

"Road Trip Conlanging with Kids" (August, 2023) by Mia DeSanzo: Fiat Lingua is supposed to be an archive of long, detailed conlang articles, and also short, breezy conlang ideas, and this is one of the latter! It's less than a page long, but a fun idea, and it was quite well-received!

NUMBER 9

"Art & Anxiety: Conlanging through impostor syndrome" (February, 2023) by Jessie Sams (now Jessie Peterson): This is a personal reflection by @quothalinguist on how she has dealt with impostor syndrome, and how it's impacted her conlanging.

NUMBER 8

"Taadži Linguistics" (March, 2023) by Lauren Kuffler: This is a wonderful introduction to the Taadži language, which features a writing system reminiscent of Mayan epigraphs.

NUMBER 7

"Tone for Conlangers: A Basic Introduction" (April, 2018) by Aidan Aannestad: Making a second consecutive appearance in the top ten, Aidan Aannestad's introduction to tone has been an invaluable resource for conlangers producing tonal conlangs for just over five years now!

NUMBER 6

"Afrihili: An African Interlanguage" (April, 2014) by William S. Annis: Afrihili is an a posteriori auxlang from the late 60s that uses Bantu languages as its source, and it is fascinating! One of my all-time favorite auxlangs, and William provides a wonderful introduction. Of interest, this article was number 6 in the top ten last year, as well!

NUMBER 5

"Names Aren’t Neutral: David J. Peterson on Creating a Fantasy Language" (March, 2019) by David J. Peterson: Up four spots from last year, this is my article on best practices when coming up with names in a fantasy setting—even when no conlang is present.

NUMBER 4

"Grambank & Language Documentation: Zhwadi and Its Features" (June, 2023) by Jessie Sams (now Jessie Peterson): The first of the game-changing mega-resources for conlanging Jessie created in 2023, this is a short description of how to use Grambank in conlanging with a link to a fillable Google spreadsheet any conlanger can copy and use to introduce their conlang to others.

NUMBER 3

"Patterns of Allophony" (April, 2015) by William S. Annis: Definitely one of the most popular papers on Fiat Lingua, William illustrates graphically a number of very common sound changes. This article once again occupies the third spot of our top ten!

NUMBER 2

"A Conlanger's Thesaurus" (September, 2014) by William S. Annis: We have a new number 1 for this year! This has, historically, been the most accessed article on Fiat Lingua, and it's obvious to see why. The article is relatively short, compared to the information and use you can get out of it. William Annis details ways in which languages relate words to other similar words. For conlangers who struggle either with coming up with words that are different from English in meaning, or who struggle with coming up with words at all, this reference article should prove very useful. Using the word maps in this article, you might be able to come up with words you never dreamt of before, but words which could exist in some language. A great resource for conlangers who are desperately trying to break out of the influence of their L1 or L2!

And now for the top viewed article for 2023 on Fiat Lingua...

NUMBER 1

"A Surreal Conlang" (January, 2023) by David J. Peterson: Quite the surprise! Late 2022 I wrote an article about how one might go about creating a surreal conlang—neither naturalistic nor regular and artificial like an auxlang or engelang—and it went up on Fiat Lingua on January 1st. I think (or hope) it served as a useful jumping off point for conlangers who are looking to try something really different from what they've seen done elsewhere.

* * * * *

And that's it for 2023! I'm looking forward to posting more conlang articles next year. If you are a conlanger, a conlang-researcher, or conlang fan who has something to say in .pdf format about a specific conlang or conlanging in general, please consider submitting something to Fiat Lingua! We take any and all articles related to conlanging in whatever form you have them. I'm also happy to help you think up ideas, or refine those ideas you have. There is no strong review like in a fancy journal: I just want to get what you have up. I'm especially in interested in hosting personal conlang stories—stories about how or why you started to create a language, or your experience creating your own language—personal stories that are often lost, but are so vital, as there is an absolute dearth of literature about conlangers! If you think you have even the seed of an idea, please get a hold of me! I want to share as many stories and ideas as I can.

#conlang#fiat lingua#quothalinguist#language#afrihili#language creation#language invention#language construction#language creation society#lcs#William annis#taadzi#grambank#Jessie Peterson#Jessie Sams#Lauren Kuffler#Aidan Aannestad#Mia DeSanzo#Ayeri#Carsten Becker#Zhwadi

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Co utváří strukturu jazyků?

Mezinárodní tým vědců ve své nové studii uvádí, že gramatická struktura je v různých jazycích velmi flexibilní a že se utváří v důsledku společného původu, omezení v oblasti poznávání a používání a jazykových kontaktů. Studie využila databázi Grambank, která obsahuje údaje o gramatických strukturách více než 2400 jazyků. Projekt iniciovalo oddělení jazykové a kulturní evoluce Ústavu Maxe Plancka pro evoluční antropologii v německém Lipsku ve spolupráci s týmem více než stovky lingvistů z celého světa.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Grambank shows the diversity of the world's languages

An international team has created a new database that documents patterns of grammatical variation in over 2400 of the world’s languages.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Can't wait for Tongues and Runes today at 3:30pm CT. I've got:

More dice tables!

Results for our patron poll!

Fun with Grambank!

Plus, I think we may be ready to start noun morphology!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

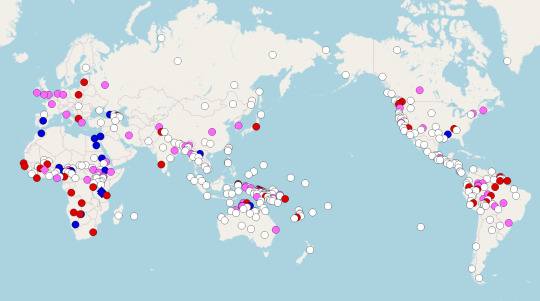

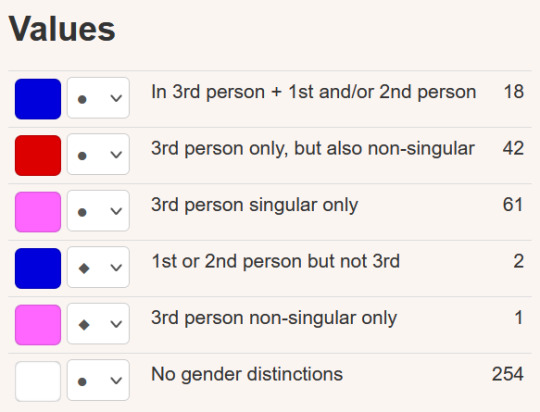

so this post by @icebluecyanide greatly brings to attention how the majority of languages in the world don't have gender marking for pronouns, though the list in it is pretty limited. it's understandable not to know these things depending on what languages you speak or are exposed to, and the reblogs (while they do have the spirit) are a bit confused. science education however is my passion so here are some visualizers and clarifications on gender in languages!

first, a look at gender marking in pronouns.

as pointed out in the post, it is uncommon to have gender marking in pronouns - only about 30% of languages do it, while the vast majority of languages omits the distinction. you'd be forgiven for finding this surprising! gender opposition in pronouns is common in european languages, with africa being another prominent area for gender marking. gender distinction in pronouns is usually sex-based (masculine and feminine and sometimes neuter(s)).

next, to address the confusion in the reblogs! the last reblog spoke of number marking in pronouns, or "the amount of subjects". they mention differentiation between two or more subjects (dual-plural) and whether the speaker or listener (or both) are included (inclusivity-exclusivity). grammatical number and clusivity vary in languages, and even more distinctions exist than mentioned! but as they are separate from gender, i won't get into them here.

one reblog by @assuming-dinosaur states that english is "highly unusual among languages in having grammatical gender align so precisely with the social concept of gender". they also mention multiple interrelated phenomena related to noun class/gender systems. clarifications:

languages vary in how grammatical gender/class is assigned to nouns - some languages assign gender solely based on the meaning of the word (e.g. "woman" is feminine), or additionally based on form or pronunciation (e.g. all words ending in "-a" are feminine).

"gender" in linguistics means a system for categorizing nouns, alternatively called "noun class". while these systems can have significant overlap with the social and cultural concepts of gender/sex, as mentioned in the reblog, there are lots of systems whose criteria for noun categorization are unrelated to "natural gender". in addition to sex and pronunciation as factors in assigning grammatical gender, grambank features factors such as shape, animacy and plant-status.

modern english does not, for the most part, have grammatical gender, so it's a bit silly to compare its pronouns to languages with wider-reaching gender systems. as stated above, the masculine/feminine/neuter distinction in pronouns is very common worldwide. and even in english, the alignment isn't 100% precise - e.g. ships and churches may also be referred to as "she".

many languages have a gender system that utilizes multiple factors for noun class assignment. of languages with gender systems in wals's sample, a majority include some sex-based distinction. all non-sex-based systems in the sample were based on some kind of animacy, most often human vs. non-human, or animate vs. inanimate. there's plenty of variation in what is considered animate, though! (in sumerian, for example, humans, gods, and statues (sometimes) were animate, while slaves, among others, were classified as inanimate.)

and yet, after such a long ramble on gender systems, let us remember that languages with gender/noun class systems are in the minority.

ending on this lovely map demonstrating on one hand how common it is to not have grammatical gender, and on the other, the variety of existing gender systems!

all maps and articles linked here are from wals, the world atlas of language structures, as well as grambank, two wonderful typological databases. wals's language sample size is quite small, but the maps and articles are still very useful and informative for typological comparison. for a larger sample size visit grambank! here's their article on gender in third person pronouns and sex-based noun class systems.

#linguistics#linguistics tag#language#bro i was supposed to go out but instead i spent way too long writing this#some wikipedia links. they do have information that should suffice as a primer if you don't wanna get Into It#text#also to people @d here this isn't a callout lmao just clearing up some things and providing more info

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's interesting that suppletion for number is NOT that common, and looks sort of like an areal feature when it occurs.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

rn im going through the grambank sheet @quothalinguist created and im actually quite surprised of how many prompts i can answer right away. im currently almost a third of the way in and i only had to skip 1 questian that i didnt have an aswer to. its really nice, shows me how much of my language i have made, and its not a little amount :)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Human or Not?, Grambank Grammar Database, Dungeons and Dragons, More: Thursday Afternoon ResearchBuzz, April 20, 2023

NEW RESOURCES

CTech: AI21 Labs vs. CTech: Human or Not? . “‘Human of Not?’ is currently available via a web browser where users are asked to write prompts where the game – either AI21 Labs’ AI tool or a physical human – will reply. The game lasts two minutes and at the end, players need to guess who they were playing against.”

University of Colorado Boulder: World’s largest grammar database…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Grambank shows the diversity of the worlds languages

Grambank was constructed in an international collaboration between the Max Planck institutes in Leipzig and Nijmegen, the Australian National University, the University of Auckland, Harvard University, Yale University, the University of Turku, Kiel University, Uppsala University, SOAS, the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme, and over a hundred scholars from around the world. Grambank’s coverage spans 215 different language families and 101 isolates from all inhabited continents. “The design of the feature questionnaire initially required numerous revisions in order to encompass many of the diverse solutions that languages have evolved to code grammatical properties,” says Hedvig Skirgård, who coordinated much of the coding and is the lead author of the study.

Limits on variation

The team settled on 195 grammatical properties, ranging from word order to whether or not a language has gendered pronouns. For instance, many languages have separate pronouns for ‘he’ and ‘she’, but some also have male and female versions of ‘I’ or ‘you’. The possible ‘design space’ would be enormous if grammatical properties were to vary freely. Limits on variation could be related to cognitive principles rooted in memory or learning, rendering some grammatical structures more likely than others. Limits could also be related to historical ‘accidents’, such as descent from a common language or contact with other languages.

The researchers discovered much greater flexibility in the combination of grammatical features than many theorists have assumed. “Languages are free to vary considerably in quantifiable ways, but not without limits,” explains Stephen Levinson, Director emeritus of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen and one of the founders of the Grambank project. “A sign of the extraordinary diversity of the 2400 languages in our sample is that only five of them occupy the same location in design space (share the same grammatical properties).”

Languages show much greater similarity to those with a common ancestor than those they are in contact with. “Genealogy generally trumps geography,” says Russell Gray, Director of the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution and senior author of the study. “Nevertheless, if processes of linguistic evolution and diversification were run again from the beginning, there would still be some resemblance to what we now have. The constraints of human cognition mean that, while there is a great deal of historical contingency in the organisation of grammatical structures, there are regular patterns as well.”

Diversity under threat

“The extraordinary diversity of languages is one of humanity’s greatest cultural endowments,” concludes Levinson. “This endowment is under threat, especially in some areas such as Northern Australia, and parts of South and Northern America. Without sustained efforts to document and revitalise endangered languages, our linguistic window into human history, cognition and culture will be seriously fragmented.”

The Grambank database is an open-access comprehensive resource maintained by the Max Planck Society. “It puts linguistics on an even footing with genetics, archaeology and anthropology in terms of quantitative, large scale, accessible data,” says Gray. “I hope it will facilitate the exploration of links between linguistic diversity and a broad array of other cultural and biological traits, ranging from religious beliefs to economic behavior, musical traditions and genetic lineages. These links with other facets of human behavior will make Grambank a key resource not only in linguistics, but in the multidisciplinary endeavour of understanding human diversity.”

0 notes

Text

Transcript Episode 81: The verbs had been being helped by auxiliaries

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘The verbs had been being helped by auxiliaries’. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Lauren: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Lauren Gawne.

Gretchen: I’m Gretchen McCulloch. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about auxiliary verbs. But first, we’re doing a fun experiment. Are there linguistics things in your life that you would like advice about? Whether that’s serious advice or somewhat silly advice, we’re gonna do a special linguistics advice bonus episode for our 7th anniversary coming up in November 2023 with questions from patrons.

Lauren: Ask us your question by following the link in the show notes by September 1st, 2023. We’ll have the episode as our bonus in November 2023. Our most recent bonus episode was a discussion about linguistics and jobs, including a behind-the-scenes on a new academic paper that brings together seven years of interviews with people who have done linguistics and gone on to interesting careers.

Gretchen: You can go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm to get access to these and upcoming bonus episodes and also because our patrons are what lets us make the show. We don’t run advertising. If you like that Lingthusiasm continues to exist, we always appreciate patronage at any level.

[Music]

Lauren: Today, Gretchen, we’re going on an excursion to a farm.

Gretchen: Ooo, what are we gonna see at the farm?

Lauren: We’re gonna see all kinds of animals that we’re gonna use as our example sentences. The first is this horse. The horse is eating grass

Gretchen: Ah, look at the horse! The horse has eaten an apple.

Lauren: Oh, what a nice treat. Both sentences “The horse is eating grass” and “The horse has eaten an apple” are about the verb “eat,” but they’re structured a little differently.

Gretchen: Yeah. They’ve got something in common, which is that they have a main verb “eat” – “is eating grass,” “has eaten an apple” – and also a second helping verb that’s less important when it comes to how we’d draw a nice picture of the scenario but gives us some useful grammatical information.

Lauren: These verbs have their own life as well when they’re not hanging out alongside another verb and helping it. “The horse is eating grass” is the same verb as in “The horse is an animal.” Here “is” is doing the work of painting a picture of what’s happening. The “is” is the whole verb by itself. It doesn’t have any helpers.

Gretchen: The same thing with something like, “The horse has an apple.”

Lauren: Oh, lucky horse.

Gretchen: Lucky horse. We don’t know whether it’s eaten yet, but the “has” there doesn’t have any helpers. It’s not helping. It’s just the only verb. Whereas in “The horse is eating grass,” “The horse has eaten an apple,” you have “eat,” which is your primary verb, star of the show, and then that “is” or “has” that’s helping it out.

Lauren: And those verb-y things that are helping another verb are known as “auxiliary verbs.”

Gretchen: Yeah, “auxiliary” is – the type of terminology, like, “Wow, that’s a long word for such a short verb.”

Lauren: Yes. It’s a very fancy word for when often very short verbs are used to help another verb. It’s because it’s just the very fancy French borrowed word for “help.”

Gretchen: It’s this French word which was borrowed from Latin meaning “helpful” or “aiding.” You do sometimes see an auxiliary, like an “auxiliary armed force” or like a “ladies auxiliary” in a historical military context.

Lauren: True, yes, that is where you may have also encountered the word “auxiliary” outside of linguistics.

Gretchen: I wouldn’t say it’s super common, but there we go. Sometimes, you do see people just refer to them as “helping words” which is also extremely defensible, but the technical, formal word that linguists use is “auxiliary,” which is sometimes shortened nicely to “aux” – just A-U-X.

Lauren: We have auxiliary verbs in English, like the examples we just shared. We can explore how auxiliary verbs work in other languages as well thanks to a very conveniently timed launch of a new database called “Grambank.”

Gretchen: This is very good and coincidental timing. If you’ve listened to previous episodes of Lingthusiasm, you might’ve heard us talk about WALS, which is the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures, which does these cool diagrams of where various linguistic features are found. Grambank is sort of like the new WALS. Let’s talk a little bit about – do you know the history of how these two sites came to be?

Lauren: WALS has been our go-to for almost 20 years. It started out in 2005 as a CD-ROM.

Gretchen: Oh my god, I didn’t realise that it used to be a CD-ROM.

Lauren: Only came online in 2008. The way that WALS works is that an individual researcher would come up with a question, and they would survey as many grammars as they could and then share their results. The way that Grambank works is, instead, they started with almost 200 different features of how the grammar of a language can work, and then they had a massive team – there’s over 100 named authors on the Grambank big, initial publication – and those 100+ authors went through over 2,000 different grammars of different languages looking for each of those 195 different features to put in the database. It’s a very different process.

Gretchen: That’s both more questions than WALS, which has around 90-some questions and also way more languages. Generally, when you see a language map in WALS it’s got maybe about 500 languages, somewhere between 400 and 800 languages, whereas there’s thousands of languages in each of the Grambank databases – not the full, maybe, 7,000 that we think exist, but 2,000-2,500 is certainly a lot closer to having some sense of “What do things like look cross-linguistically?”

Lauren: To pull an example of a grammar completely not at random, one of the coders used my grammar of Lamjung Yolmo. They picked up the grammar, and they opened it up, and they literally went through their list of 195 questions looking for the answers in the grammar and added it to the database.

Gretchen: This is, I think, such a tremendous example of how the work of linguistics involves so many different people because each of the grammars that this database is using as input – and a database like WALS also uses as input – is written by one person or a group of people and can be several hundred pages long and take like 5 or 10 years. Then you have another group of 100+ people spending all this time looking through the grammars and trying to compare them and extract things that make them comparable to each other when grammars are written in different traditions at different times by different people with different interests and try to do something that lets you compare them with respect to each other.

Lauren: One thing that Grambank does really well is that it’s really transparent about the methods it uses. There’s an entire Wiki that goes along with it that explains the process and the methods and what terminology they’re using and why. I think that really helps to make sure that everyone is as much on the same page as possible when it comes to making these decisions.

Gretchen: If you had somebody who’s writing a new grammar, they could look at these 195 questions and say, “I could just provide answers for them in an appendix” or something at the end, so you could just encode them more directly in a future version of Grambank. Are they planning on doing that?

Lauren: This is definitely Version 1.0. There is scope to expand both the number of features they look at the number of grammars that are included in the future, which is also really exciting.

Gretchen: It’s all freely available online, so if you wanna poke around and see what’s in it, that’s a thing that anybody can do.

Lauren: WALS absolutely still has value. I’m sure that we will continue to refer to it when it’s useful, but I’m excited that we’ll also get to use Grambank for future episodes as well.

Gretchen: Yeah. And they ask slightly different sets of questions, so it’s still worth having both sets of resources. But since we have auxiliaries today, and since WALS doesn’t do much with auxiliaries, this is a great time to say, “What does Grambank tell us about auxiliaries in 2000+ languages?”

Lauren: Before we do that, we have to decide what is an auxiliary in any given language. All of those people who wrote those 2,500 references that are included in Grambank, and that means that we have to think about “What are some of the most important features when we’re talking about something as an auxiliary?”

Gretchen: Right. I think a basic working definition of an “auxiliary” is that when you have multiple verbs in the same phrase like “has eaten.” One of them contributes the most to the meaning, and other ones have grammatical function and don’t really have much with their own meaning. In something like, “The horse has an apple,” “has” has a meaning of owning or possession or belonging to, whereas in something like, “The horse has eaten,” it’s not that the horse owns or possesses or belongs to the state of having eaten. It’s an auxiliary in that case where it’s helping out the other verb with grammatical functions.

Lauren: As we’re going through these examples, I think just like we might go for a wander around the hypothetical farm we’re talking about today, we’re also just wandering through these examples and not getting too bogged down on making a complete list. We have that list in the Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. It’s a very big and heavy book.

Gretchen: Speaking of reference works that take multiple people to do, this is also some 2,000+ pages and has 12 co-authors. There’s many people at every level of this process trying to describe what’s going on in a language. This is not an exhaustive tour.

Lauren: In English, we’ve talked about “is” and “has” having auxiliary functions. We also have “do” as in “The horse does eat grass,” which is different to “do” in its main form as “The horse does a dance,” maybe for some dressage.

Gretchen: “The horse does a little dance, does a little jump” – that’s “do” as its canonical, by itself, independent verb form, whereas “The horse does eat grass” is doing a grammatical thing. Similarly, with an example like “The grass was eaten by the horse,” or maybe by a stray goat, the “was” there is doing a grammatical thing and “eaten” is the main verb.

Lauren: “The grass was eaten by the horse” is a really nifty example of how the auxiliary is helping by making the grass the focus and creating this passive structure.

Gretchen: Right. Sometimes, “The horse is eating grass,” or “The horse has eaten grass,” this locates the event of grass-eating in time and the timeline of how this event has happened. Sometimes, it can change how the entities in the sentence relate to each other. There’s lots of different things that auxiliaries can do.

Lauren: Another example of what auxiliaries can do that’s not from my variety of English is “The horse be eating grass” in African American Vernacular English, where instead of the “is” form of the verb, you have the “be” form. That means that it’s being used in a way that means the horse regularly or habitually eats grass.

Gretchen: Which I think is a true thing about horses.

Lauren: I think so. Neither of us are particularly horse experts.

Gretchen: One of the papers that I like to cite about this construction which is called, “Habitual ‘be’,” uses “Cookie Monster be eating cookies” as the example, which is definitely true about cookie monsters. Even if Cookie Monster is not currently eating cookies, this is a thing that is habitually true about Cookie Monster as an entity.

Lauren: That’s a really helpful auxiliary.

Gretchen: It’s interesting how auxiliaries are often drawn from this relatively limited set of words. Here, we’ve seen “be” and “is,” which are part of the same verb, be used in three different ways as slightly different flavours of auxiliary in English because it’s this small set of auxiliaries, and then you can do all these interesting grammatical things with them.

Lauren: There’re all these downstream effects of what happens when you have an auxiliary. Because it’s being used to help in terms of what it’s contributing to the grammar, it means that it’s not coming along with its own meaning as central. Because they no longer bring their own meaning while they’re helping, you get sentences which, if you don’t treat them as an auxiliary, sound a little bit contradictory. So, “I am going to come to the farm,” because “going” is the auxiliary there, you can use it with “come,” which has the opposite meaning if you’re thinking about the meaning of both of these verbs.

Gretchen: Can you say, “I’m coming to go to the farm”?

Lauren: It would be like, “I’m coming to your house, and then we’ll go to the farm together,” so it’s not really an auxiliary.

Gretchen: The one that I really like is – so “have,” which can be an auxiliary or not an auxiliary, is very often pronounced differently in English. It’s spelled the same way, but it’s pronounced differently in English depending on which one it is.

Lauren: Huh.

Gretchen: Let me try this little quiz for you. If I say, “I have two pens” versus “I have to pen up the chickens,” did you notice the difference between how “have” is pronounced there?

Lauren: “I have two pens” and “I have to” – “I hafta,” “I hafta pen up the chicks.” I could make that really short.

Gretchen: One of them is “have” pronounced with the V – “have to” – the other one is “hafta pen” with an F sound, which you could write like “hafta.” It would be sort of weird, I think, to say, “I hafta pens,” to mean “I have two pens.” I don’t think I can do that.

Lauren: “She hasta duck because a chicken is flying over her head” versus “She has two ducks.”

Gretchen: That’s “has” which gets pronounced with a Z when it’s “has two ducks.”

Lauren: When it’s helping, it’s no longer the star of the show. We can smooth down the edges of how we pronounce it.

Gretchen: And make that S or that V more like the T that’s coming after and change the sentence to “She hasta duck.” I think if you say something like, “She has to duck,” it sounds very formal. You can do it, but it sounds very, very formal. [Slowly] “I HAVE to pen up the chickens,” “She HAS to duck” – I just have to say it so slowly in order to not make the “to” into /tə/ and the “have” into /hæf/ and /hæs/.

Lauren: That works for other ones as well. Like, “I’m gonna come to the farm.”

Gretchen: Right. Like, “I’m gonna the farm” – maybe you can say it in some very informal or relaxed varieties.

Lauren: It’s a very informal Australian-sounding pronunciation there.

Gretchen: But like, “I’m gonna milk the cows” or something, like that’s just the one that means future. One that I like is, so, you can say, “I’ve gone away” – you’re reduced that “have,” you know, the auxiliary. It’s shortened from “I have gone away.”

Lauren: “Have” just reduced to /v/ there.

Gretchen: But “I’ve the milk” – do you have that?

Lauren: Now, you sound British in my head.

Gretchen: “I’ve the milk” and “I’ve the eggs.” I think I would have to say, in my Canadian English, “I’ve got the milk” or something like that. I’d have to reinforce the meaning there if I wanna shorten it. I really don’t think I would say, “I’ve to go,” to mean “I have to go.”

Lauren: No. Much harder to shorten a main verb than a helper verb.

Gretchen: I can say, “I gotta go,” “I have to go,” but it’s not quite something I can shorten in that context. Auxiliaries tend to have these sorts of contractions because they’re grammar-y things. They’re very high frequency. Fun fact about high frequency – there’s a very fun study that finds that words that are unexpected in their context or that are less frequent overall in a language tend to be produced over a longer period of time, like slower with longer duration. The example from this that I really like, which is – so there’s a word, “cant,” like a “thieves’ cant” or “the cant of the streets.” You can tell that me saying it with the definition it’s not super common. It’s like an argot. Like, “I heard the cant of the streets going through the night.” This tends to be produced much longer and slower and more precisely than “I can’t” as in “I can’t go,” “I cannot go.”

Lauren: I can’t say “cant” with the same vowel, so it doesn’t work for me, but it does make sense because these auxiliaries are really hard-working helpers. They turn up in sentences so often, and they don’t contribute that meaning. It makes sense that they would be the thing most likely to reduce.

Gretchen: They’re squished down because they’re being grammatical glue between the big meaning-heavy chunks of words. Once we figure out, okay, this counts as an auxiliary, it’s helping the verb in this language, we can then start saying, “What else do auxiliaries do in a particular language that might be of interest when you start zooming in very narrowly on one language?”

Lauren: I know auxiliaries and how we ask questions in English interact in interesting ways.

Gretchen: Right. Let’s look at some examples and questions. We could have “Is the horse eating grass?”, “Has the horse eaten grass?”, “Does the horse eat grass?”

Lauren: In all of these, the auxiliary is at the start – “Is the horse,” “Has the horse,” “Does the horse” – and “eat” is further back.

Gretchen: “Eat” is further back. When those same verbs are used as main verbs rather than auxiliaries, it gets a bit weirder. So, “Eats the horse grass?”

Lauren: Hmm. Hmm. That doesn’t fit with my grammar.

Gretchen: This does exist in the history of English. It’s still something you can say in other Germanic languages, but it’s not something that’s for most present-day English speakers. How do you feel about “Does the horse a dance”?

Lauren: You sound very theatrical, which is usually a way of saying that it is a more archaic form of English.

Gretchen: What about “Has the horse an apple?”

Lauren: Yep, very similar vibes.

Gretchen: I feel like that one sounds a bit British to me also. But “Is the horse an animal?”

Lauren: Yeah, that’s a perfectly normal sentence to my ears. I sometimes have to double check after hearing a bunch of things that I’m questionable about. Be like, “Ah, that is a sentence.”

Gretchen: That’s why I did it in that order just so you could have that happen to you. Yeah! This is a downstream thing that happens with English auxiliaries if you don’t have any auxiliary in the sentence like, “Eats the horse grass?” You have to put one in, “Does the horse eat grass?” or “Can the horse eat grass?” But for some reason, “is” is an exception. I dunno. “Is” is a bit weird. You can check out our copulas episode for more. These are why these aren’t quite used as a diagnostic for auxiliaries, it’s just sort of a thing that happens afterward.

Lauren: Once again, there’s a reason the Cambridge Grammar of the English Language is the size of a relatively healthy cat.

Gretchen: A nice big farm cat.

Lauren: So far, we’ve only had examples of sentences with a single auxiliary, but they are so helpful that they’re willing to stack up and have more than one to help create even more complex meaning in a sentence.

Gretchen: So, if you leave a big barrel of apples on the farm, and there’s a bunch of goats around, by the time you get back into the room, you might see that the apples will have been being eaten by the goats for the whole day.

Lauren: Oh, no. It’s a sad situation but a very exciting use of – was that four? – auxiliaries, “will,” “have,” “been,” “being.”

Gretchen: Yep.

Lauren: And then “eaten.”

Gretchen: Exciting day for the goats. Exciting day for the auxiliaries. Not so exciting for the humans who want to eat the apples. And we still have one main verb, which is “eaten,” because that’s still the action that’s happening, and then all of these other auxiliaries are telling us things about how and when and under what circumstances this event happened.

Lauren: “Do,” “have,” and “be” are doing a lot of heavy lifting in English. We also had a whole episode on modals, which are also like auxiliaries in a lot of ways.

Gretchen: Modals are interesting in English because they don’t act like full verbs, so you can’t just say, “I can the apple,” or “I will the apple,” “I should the apple,” but you can use them in the same auxiliary slot and helping slot as other auxiliaries that are verbs. Sometimes, people talk about auxiliaries as a category that includes verbs that are definitely verb-y, like “be” and “have” and “do,” and other things that are maybe not verb-y, but they’re still doing what seems to be the same helping thing as these helping verbs.

Lauren: Alongside our really common helpers, there are some occasional helpers. “Let” is a really nice example. Something like, “Let’s go.”

Gretchen: “Let’s go.” It’s originally “Let us go,” which sounds very formal to me, and doesn’t quite mean the same thing as “Let my people go,” “Let us go,” it just means, “Shall we go?” or “Let the group of us go” or “Let there be light,” “Let there be peace,” just used as a formal command. “Let” can be an auxiliary because you have these other main verbs like “go” and “be.”

Lauren: That’s a really nice example of how auxiliaries can fork off from their main verb usage and go on their own little adventures. They’re often weird or irregular because they’ll keep this grammatical function that’s separate from their main meaning function.

Gretchen: This grammatical idiosyncrasy of auxiliaries was something that came up a lot when I was learning French. I know you haven’t studied French, but my experience with French was that we spent years and years and years learning this one particular thing about French verbs, which is known as the “passé composé,” which is how to make a certain type of past verb in French, that if you were translating literally, you could translate as something like, “I have eaten,” “I have arrived,” but it’s used to just mean a general past thing. There’s a “have” word there, but it’s used to mean a past thing.

Lauren: It’s nice that it uses “have” as an auxiliary like English does. Big shout out to “have.” I feel like we could have a whole “have” episode.

Gretchen: We really could. In this case, it is “have” most of the time, but sometimes, instead of “have,” it’s “be.”

Lauren: Okay, this is why it took so long to learn.

Gretchen: Yeah. They mean the same thing. There’s just, for a word like “eat,” you use “have,” but for a word like “arrive” or “come” or “descend,” you use “be.” It’s our old friends “have” and “be,” but in this case, it’s like some verbs get “have” and some verbs get “be.” This is actually something that existed historically in English and still exists a little bit in German where you can kind of say in English, “I have come” or “I am arrived.”

Lauren: True. They both work.

Gretchen: In a way that, with other types of verbs, if you say something like, “I am laughed.”

Lauren: Okay, that definitely doesn’t sit well with my intuitions.

Gretchen: No. Or if you say, “I am eaten,” again, well, that means something very different.

Lauren: You’ve got to stay away from those goats. They’re very vicious.

Gretchen: “Help, help, I’m being eaten alive!” Yeah, but you can say, “I am arrived,” in a way that’s a little bit old fashioned, olde-y time-y in English, but doesn’t sound nearly as out there as “I am laughed” for “I have laughed.” But in French, this is obligatory. Some verbs are like, “J'ai mangé,” “I have eaten,” and some verbs are like, “Je suis arrivé,” “I am arrived,” and this is this whole thing that you need to just learn if you’re learning French. It’s also the case in Italian. There’s some stuff in Spanish about which auxiliary verb you need to choose when in these particular grammatical circumstances that is the kind of thing that shows up if you’re learning one of these languages.

Lauren: A good reminder even if two languages use their language’s verb for “have” doesn’t mean they always use them in exactly the same places and in exactly the same ways.

Gretchen: One of my favourite examples of how a word can become grammaticalised and then almost lose it’s original literal meaning comes from Spanish where you have “haber,” which is spelled with an H, and you can see its roots to Latin “habeo,” which is “to have.” This is used for grammatical functions like “El caballo ha comido,” “The horse has eaten,” but it’s no longer really used in most cases for “have” as in “to own” or “to possess.”

Lauren: So, it’s so helpful that it stopped having its own life and now is just helping out.

Gretchen: This is a metaphor, you know, don’t give up on your dreams, “haber”! Now, you have “tener,” which is from Latin and means something like, “to hold” or “to keep.” You can say something like, “El caballo tiene una manzana,” “The horse has an apple,” as like “to have” and “to hold,” which is not the same verb at all that’s used for “has eaten.” But historically, “have” was used for both, and then they were like, “Oh, no, let’s take this other one to mean the more literal meaning of ‘have’.”

Lauren: On the topic of same verb. Latin “habeo” and English “have” – related, not related?

Gretchen: You know, this is the thing that really gets me. They really look like they should be, and they are not.

Lauren: Oh, wow, plot twist.

Gretchen: Plot twist. They are not. You could look this up. We have looked this up. It’s kind of cute. The Wiktionary entry for both “habeo” and for “have” are like, “They’re not related, guys. I’m sorry. We promise. Here’s all the reasons.”

Lauren: Which is why it’s always good to double check these things.

Gretchen: In fact, we don’t think that there was a common Indo-European root for a word meaning “have” because it’s like forked in the descendant languages.

Lauren: Ah, got to save it for the “have” episode.

Gretchen: Oh, yes, sorry. One day we will HAVE an episode about “have.”

Lauren: Acknowledging that auxiliaries can look different in different languages, have slightly different functions, have different downstream effects, let’s return to Grambank and have a look at what they have to say about the spread of auxiliaries across the world’s languages.

Gretchen: Yeah, I wanna find out.

Lauren: The nature of the database means that we can look at the types of questions they have asked, and they’ve asked if auxiliaries are used for a range of different functions across the world’s languages.

Gretchen: One of those functions is, as we’ve seen in English, things like, “is eating,” “has eaten,” things that have to do with when and how and in relation to what an event is taking place.

Lauren: That is the most common use of auxiliary verbs across the world’s languages. It’s way more than 30% of the world’s languages, according to the coding that’s been done, have that kind of auxiliary.

Gretchen: This is formally known as “tense, mood, and aspect.” We’ve done episodes about some of these topics and may do episodes about others of them in the future.

Lauren: The next most common use for auxiliary verbs is to use in negation, which is not quite something we have in English.

Gretchen: In English, you can make a negation by putting “not” after an auxiliary, or depending on how you wanna analyse it, you can add “n’t” to the auxiliary. You can say, “The horse is not eating grass,” which “not” is not acting like a verb there. I can’t say, “The horse not grass.” Or I can say, “The horse isn’t eating grass,” and the “n’t” is attaching to the “is,” which is, again, not a separate auxiliary verb that specifically makes it negation.

Lauren: That’s very different to a language like Irish where the negation changes depending on whether it is happening now or happened in the past. In the present, it is “ní,” and in the past it is “níor.”

Gretchen: Interesting. That’s something that English doesn’t do. What percentage of languages do that auxiliary verb for negation?

Lauren: It’s around 20% of languages in the database have that. The final type of auxiliary use they coded for was, in an English example, “The grass was eaten by the horse” – since the horse didn’t get its grass before, I wanna make sure it has had it now. That passive usage is found in about 10% of languages. The really nice thing about a database like Grambank is that we can click on the map and see that for these passives, there’s this big chain of languages that spread down through the Europe, India, Indo-European area and then down into Southeast Asia. That 10% of languages tend to be focused in that area. There’re large parts of the Pacific and Africa and North and South America where there aren’t as many languages that do this, so we see some kind of common themes among specific languages of certain families or in certain areas that tend to more likely do this. That’s one of the really useful benefits of a big database of features like this.

Gretchen: And one that’s based on a map where you have all of these languages as points on a map.

Lauren: Yeah, totally.

Gretchen: That’s really neat. Seeing languages that are related to each other or just languages that had contact with each other over thousands and thousands of years of history and many people have been bilingual and borrowed things from one language to the next, and you can see these areal groupings of different languages. Auxiliaries are very neat, but clearly, they’re not a thing that all languages necessarily feel the need to use. If a language isn’t using an auxiliary, what are some of the things that they could be doing instead?

Lauren: Grambank tends to code things just on a yes or no basis, so if it doesn’t have it, it’s just coded as a no, but we know there’re some other strategies if you’re not using an auxiliary that you can use to get the same kind of function.

Gretchen: One obvious idea would be to use a suffix or a prefix. If you wanted to say something like, “The grass was eaten,” you could add some sort of ending or some sort of prefix on to “eat” that would make it passive instead of having the “was eaten” part make it passive. This is a strategy that lots of languages do.

Lauren: You might have a prefix for negation instead of some strategy that uses an auxiliary.

Gretchen: You can also use a different type of word. Instead of something being specifically you’re recruiting a helping verb that is verb-y to do your meaning, you could also have a “particle,” which is a glorious linguistic catch-all term for “I dunno. It’s a word doing something.” It’s not obviously a verb. It’s not obviously a noun. It’s just a word that’s there and doesn’t really change its form – like “not,” which I think is a negative particle. Something like “not” is a way of expressing negation rather than changing the end of the word, the beginning of the word, you can have “Let’s just stick in another word.” I don’t think anybody thinks “not” is a verb in English.

Lauren: I don’t know, but different linguists use different criteria for defining what is a verb and what is a particle, so if they have an argument to make for it, then it’d be interesting to hear.

Gretchen: I think in English our standard tests for verb-hood “The horse not the apple” doesn’t seem like it’s acting like a verb there. You could use other words that aren’t necessarily verbs to express negation or passives or any of these complicated tense-y, time-y, timeline-y things.

Lauren: You could say something like, “The horse habitually eats grass.” We have to use “habitually” there or “regularly,” and it makes you realise just how elegant that AAVE construction is using habitual “be” for “The horse be eating grass.”

Gretchen: Or “I eat already” compared to “I have eaten.” The “already” or the “usually” or the “habitually” – adverb-y things – can also sometimes express some of these meanings as well. We’ve given a lot of love to “have” as a very common copula.

Lauren: We have.

Gretchen: We have. But also “be” is a very common copula in a bunch of languages.

Lauren: We are gonna give it some love.

Gretchen: Basque uses “be” as a copula.

Lauren: Ooo, our isolate language of Europe.

Gretchen: Yes. I don’t know enough about the history of Basque to know whether this is related to contact with a bunch of other Indo-European languages in the Spain/France region where Basque is spoken, or whether this is something that is passed down from historical Proto-Basque, but it does use “be” as an auxiliary.

Lauren: Okay. So, still in the European neighbourhood. But we don’t need to stay in that neighbourhood. Palestinian Arabic is another language that has been analysed as using “be” as an auxiliary.

Gretchen: Very nice. We have an example where something like, “She wrote,” is done without an auxiliary, and then something like “She used to write” uses “be” to express that “used to” meaning. “Used to” is another interesting example of an auxiliary in English, actually, now that we’re thinking about it.

Lauren: While we’re collecting them.

Gretchen: Compared to “used two pencils to write.”

Lauren: Hmm, yes.

Gretchen: Also, Kinande, which is a Bantu language, uses “be” as an auxiliary.

Lauren: Excellent.

Gretchen: I have a rather violent example here, which is “We hit (recently, not today),” and “We are hitting,” are both forms of the verb that change based on a prefix. Then “We were (recently, not today) hitting” is a form of the verb that uses “be” to express part of that meaning.

Lauren: So, all using the same “be” verb but in slightly different ways and to achieve different grammatical ends.

Gretchen: Exactly. And showcasing some of the ranges of examples of different types of meanings, whether that’s recent past or “used to” or other types of meanings that can be expressed with an auxiliary just depending on what your language is in to.

Lauren: While they’re not the only verbs that can become auxiliaries, “have” and “be” deserve special shoutouts for being the work horses of auxiliaries across many languages.

Gretchen: We could think of auxiliary verbs as if you are just a person with a shovel, with a rake, trying to plant some seeds, you’re gonna have a bit more difficulty than if you have a plough or you have a horse that can draw it and help you out with your ploughing, so you have the horse helping you out.

Lauren: I think maybe we should think of it as an aux-driven plough instead of an ox-driven plough.

Gretchen: Oh, no, these words sound exactly the same for me. “Ox” as in “oxen,” the animal, and “aux” as in “auxiliary” sound exactly the same for me.

Lauren: This is disappointing where “ox” and “aux” are another thing where I don’t have a merger.

Gretchen: I think actually English might be the only language that has the “ox/aux” merger.

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: Because “auxiliary” comes from French, and so French has “auxiliaire” to mean the grammatical thing, but then the animal, like a male cow, is just a “bœuf,” like a “beef.” Whereas German has “Ochs,” as in the cow, but for the grammatical thing it has “Hilfsverb,” which just means “help verb.”

Lauren: Oh, a much more transparent root than English borrowing French auxiliary.

Gretchen: But it does let us make this spectacular joke, which is that you can have an aux-driven verb. There are a few people, including friend of the podcast Kirby Conrod, who sometimes jocularly pluralise “aux,” as in “auxiliary,” as “auxen,” like the cow.

Lauren: Oh, I am definitely gonna start calling them “auxen” from now on. It’s a nice souvenir from our trip to the farm.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, SoundCloud, YouTube, or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr. You can get aesthetic IPA posters, IPA scarves, lots of linguistics t-shirts, and other Lingthusiasm merch at lingthusiasm.com/merch. I can be found as @GretchenAMcC on Twitter, my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com, and my book about internet language is called Because Internet.

Lauren: I tweet and blog as Superlinguo. Have you listened to all the Lingthusiasm episodes, and you wish there were more? You can get access to an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month plus our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now at patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Have you gotten really into linguistics, and you wish you had more people to talk with about it? Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans. Plus, all patrons help keep the show ad-free. Recent bonus topics include a liveshow Q&A with Kirby Conrod, our 2022 listener survey responses, and using linguistics in the workplace. If you can’t afford to pledge, that’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language. And don’t forget to ask us your linguistic advice questions by the 1st of September, 2023.

Gretchen: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, and our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Lauren: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#language#linguistics#lingthusiasm#episode 81#podcasts#transcripts#auxiliary verbs#auxiliaries#verbs#grammar#grambank

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've made a new conlang Grambank entry for Trigedasleng! Jessie Peterson created a Google Sheets spreadsheet that conlangers can copy and fill out in order to share their work. I did one previously on High Valyrian, and now the Trigedasleng one is finished.. This won't tell you everything about the language, but it'll tell you a LOT in a very small space. If you'd like to do something like this for your conlang, the blank one can be found here.

#conlang#language#the 100#Clexa#lexa#clarke#grounder#grounders#slakkru#Trigedasleng#Trigedasleng language#Grounder language#cw

121 notes

·

View notes

Link

Funding Announcement:

The Grambank project is working to establish a global database of structural language and seeks to use these features to investigate deep language prehistory. With support from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, SOAS linguistic students are funded to contribute to the database by adding language data towards the ultimate goal of 3000 languages. The SOAS Grambank project is now entering its second year, and the team are pleased to announce that they have secured a further year of funding.

Since SOAS World Languages Institute partnered with the Grambank project, the team of has grown from 3 coders to 16. Our coders use their knowledge of Linguistics to enter data based on reference grammars, contributing to the study of typology, language prehistory, and language universals. Back in 2016, Grambank contained 195 morpho-syntactic features of over 600 languages and now it contains over 1200 languages. The SOAS Grambank team has contributed almost 170 of those languages to the project and they are excited to add many more!

You can read more about the project and team at: https://buff.ly/2MsbbyM

For further information, contact:

#endangered languages#language documentation#linguistics#linguistic ressources#sociolinguistic typology

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Database gives insights into language loss

A new global database of grammatical features in different languages also gives us new insights into the consequences of language loss.

The first study to use the new database—called Grambank—shows that grammatical diversity is decreasing in the areas of the world in which languages are most endangered.

You can explore the database yourself here!

An incredible book about what types of grammatical diversity are lost when languages stop being spoken is When languages die:

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Grambank-coding is soothing, it’s nice when you’re describing a language and you sometimes feel like you don’t know anything - but then you are able to answer these questions about it.” - brilliant Tina Gregor at a Grambank coding session at CoEDL the other day. Tina is another PhD student here at ANU (and recent Grambank poster child). She is describing two endangered languages of West Papua: Yelmek and Maklew. Here she is at the ANU Three Minutes Thesis event talking about her research: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMad020aXqM #coedl #lingtyp #anu3mt

2 notes

·

View notes