#Gen. Sergei Surovikin

Text

A dress rehearsal for a revolution to come like Potemkin? The last act of rebellion before totalitarianism like Kronstadt? A footnote in an American history book like Storozhevoy? Maybe just another Friday in Russia…

“Russian authorities stepped up security in Moscow and issued an arrest warrant for Yevgeny Prigozhin, the owner of the Wagner paramilitary group, on charges of mutiny after he called on his troops to oust the country's military leadership.

(…)

As Russian soldiers in armored personnel carriers secured key installations in Moscow, leading Russian military commanders who had worked with Wagner urged the group's fighters to stop before it was too late. "The last thing we need is to unleash a real civil war inside the country. Come back to your senses," urged Lt. Gen. Vladimir Alekseyev, the deputy chief of Russian military intelligence.

(…)

"The evil that the military leadership of the country brings forward must be stopped. They have forgotten the word justice, and we will return it," Prigozhin said in an audio recording posted on Wagner's social media Friday. "Anyone attempting resistance will be considered a threat and immediately destroyed. This includes all the checkpoints on our path and any aircraft above our heads."

Friday's events showed the depth of political crisis inside Russia after 16 months of grueling war marked by a series of military setbacks. Pressure is rising on Putin to squelch any threat that Prigozhin now poses to his power, and to Russia's ability to continue waging the war. Putin, so far, hasn't made any public statements about the drama unfolding in Russia.

(…)

For the past several months, Prigozhin has been focusing his vitriol on Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Armed Forces Chief of Staff Valery Gerasimov. Earlier on Friday, he accused Shoigu of leading Russia into war in Ukraine on a false narrative in order to get awards and a promotion in rank.

Gen. Sergei Surovikin, the former commander of Russian troops in Ukraine who, unlike Shoigu and Gerasimov, has been repeatedly praised by Prigozhin, made a late-night video appeal asking Wagner's troops not to obey the group's owner.

"Whatever your intentions are at the moment, as valiant as somebody told you they may be, this is a stab in the back both for the country and the president," he said. "This is a military coup."

(…)

In Friday's recordings, Prigozhin said that he has 25,000 men under arms but also considers the entire army, and the entire Russian society, his strategic reserve.Russian commentators reacted to this turn of events with shock.

(…)

Earlier in the day, Prigozhin said Shoigu lied to Russians and to Putin when he told a "story about the crazy aggression from the Ukrainian side and the plans to attack us with the entire NATO bloc." In an implied criticism of Putin, he added that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky would have agreed to a deal if the Kremlin had deigned to negotiate.”

“Vladimir Putin has vowed to crush an armed insurrection led by the warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin, describing the rebel militia making their way towards Moscow as a treasonous “stab in the back”.

The Russian president labelled the first coup attempt in three decades as a “deadly threat to our statehood” and compared it with the 1917 revolution that led to the collapse of imperial Russia.

(…)

Russian military helicopters fired on a convoy of Wagner troops and armoured vehicles, including tanks, rumbling north along a highway towards the capital, according to unverified videos published on social media.

The convoy, which also appears to contain mobile air defence systems, advanced steadily from Rostov towards Moscow despite “combat operations” by regular armed forces, and in the early evening of Saturday was abound 350km from the capital’s outer ring road, where Russian troops have set up checkpoints.

If the convoy is able to advance without hindrance, they could reach Moscow before midnight local time.

(…)

The insurgency is the most serious threat to Putin’s decades-long rule, and comes after months of public infighting between Prigozhin and the country’s armed forces.

“Prigozhin’s mutiny is the greatest challenge to date of the rule of Vladimir Putin,” said Andrius Tursa, eastern Europe analyst at Teneo. “Even if the mutiny fails, the crisis events will only exacerbate perceptions of the regime’s weakness.”

Wagner’s rapid advance sparked an emergency call between G7 nations who agreed “to co-ordinate closely”, and enhanced security measures in Nato countries bordering Russia, which possesses one of the world’s largest nuclear arsenals.

(…)

In Kyiv, the crisis was a “window of opportunity” for its forces to push ahead with a counter-offensive to liberate territory occupied by Russian troops, said Hanna Maliar, Ukraine’s deputy defence minister. She added that the decision to invade Ukraine had triggered “the inevitable degradation of the Russian state”.

Putin’s pledge on Saturday to crush the attempted coup came hours after Prigozhin announced he had “blockaded” Rostov and the headquarters of Russia’s military command centre, responsible for Ukraine operations, as armed, masked men with tanks and armoured vehicles surrounded government buildings.

Putin’s grave address, which did not mention Prigozhin by name but accused his organisation of “blackmail and terrorist methods”, suggests the president has left no room for compromise with his former acolyte. “What we are dealing with is treason. Unchecked ambitions and personal interests have brought about betrayal of our country and our people,” Putin said.

Prigozhin issued a defiant response, saying his Wagner force no longer wanted to live “under corruption, lies, and bureaucracy”.

Sixteen months of war against Ukraine has hamstrung Russia’s economy because of a barrage of western sanctions and an exodus of foreign capital. The conflict has cost tens of thousands of lives and created a dangerous patchwork of competing militias and security forces.

(…)

The extraordinary decision to launch a motorised assault on Moscow was part of what Prigozhin said was a “march of justice” against defence minister Sergei Shoigu and Valery Gerasimov, commander of Russia’s invasion forces, whom he has accused of mishandling the Ukraine invasion.

(…)

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s president, said the events had laid bare “Russia’s weakness”.

“The longer Russia keeps its troops and mercenaries on our land, the more chaos, pain and problems it will have for itself later,” he tweeted. “Everyone who chooses the path of evil destroys himself.””

“Russian dictator Vladimir Putin's plane left Moscow on the afternoon of June 24 amid an ongoing rebellion led by PMC Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Belarusian Hajun monitoring project said on Telegram on June 24, citing data from the Flightradar24 service.

The Russian government’s Il-96−300PU aircraft took off from Vnukovo Airport at 14:16 local time and headed for Valdai, one of Putin’s residences, it said.

(…)

The plane reportedly disappeared from radars near the Russian city of Tver (about 150 kilometers from Valdai), the independent Russian website Important Stories (IStories) said on Telegram on June 24. The media outlet claims that the plane is “equipped to control the armed forces.”

(…)

The Ukrainian online publication Ukrainska Pravda cites an unnamed source in the Ukrainian special services who states that “Putin is leaving Moscow, he is being taken to Valdai.”

The Insider, a Russian investigative journalism project, also writes that as of 3 p.m. local time, another Russian special forces aircraft had landed in St. Petersburg.

The independent news outlet Mozhem Obyasnit, in turn, reports that Russian officials are fleeing from Moscow on business jets – at least three flights served by the Special Flight Unit “Rossiya” of the Russian President’s Administration have already departed for St. Petersburg.”

“Dmitri Alperovitch, founder of the Washington, D.C.-based think tank Silverado Policy Accelerator, shot down suggestions that the conflict would result in the development of a new Russian civil war, predicting in a series of tweets that Prigozhin's forces would quickly be defeated.

"No, this is not likely to turn into a civil war," Alperovitch tweeted. "It is what in Russia is called 'razborki' (gangland warfare) And it looks like one gang is about to get totally crushed because the other has all the weapons and the security services on their side."

(…)

In additional tweets, Alperovitch suggested that Prigozhin "might not survive the weekend" due to his declaration of war, while commenting that "this show is very entertaining but unfortunately it might be a very short one."”

“Mick Ryan, a retired major general in the Australian military and fellow for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Insider that while exactly what is happening on the ground in Russia remains unclear, "this is the kind of thing where no one wins — everyone loses something."

(…)

"Prigozhin is likely to be the biggest loser," Ryan told Insider. "But Putin and his inner circle will look like they don't have their hands on all the levers of power in a way that some Russian elites would expect them to. And the Russian army will be looking forward at the Ukrainians attacking them and looking behind themselves and their nation, seemingly in chaos — whether that's a reality or not — and it will cause deep disquiet among senior Russian leaders."

Ryan said the deep unease felt by Russian troops after hearing a regime-affiliated official disparage military leadership could be used to Ukraine's advantage as they continue to fend off Russian attacks.

(…)

"I think Prigozhin probably crossed a Rubicon of some type. This is probably the end of the tolerance for his outbursts and demands of the military," Ryan told Insider: "I think it's most likely that things won't turn out well for him. I certainly wouldn't be booking or reserving places in an old people's home if I was him."”

#russia#ukraine#russia ukraine war#putin#wagner#yevgeny prigozhin#mutiny#coup#potemkin#kronstadt#putsch#dmitri alperovitch#silverado policy accelerator#mick ryan

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Th Russian military has been in a greater state of turmoil than it usually is.

A senior Russian general in command of forces in occupied southern Ukraine says he was suddenly dismissed from his post after accusing Moscow’s Defense Ministry leadership of betraying his troops by not providing sufficient support.

Gen. Ivan Popov was the commander of the 58th Combined Arms Army, which has been engaged in heavy fighting in the Zaporizhzhia region. He is one of the most senior officers to have taken part in the bloody Russian campaign in Ukraine.

Popov said he had raised questions about “the lack of counter-battery combat, the absence of artillery reconnaissance stations and the mass deaths and injuries of our brothers from enemy artillery,” in a voice note published on Telegram late Wednesday.

In military terms, Russia can't even cope with the basics. Gen. Popov blames Putin crony Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu.

Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu “signed the order and got rid of me,” the general also said in the recording, as he accused the top Kremlin official of treason.

“As many commanders of divisional regiments said today, the servicemen of the armed forces of Ukraine could not break through our army from the front, (but) our senior commander hit us from the rear, treacherously and vilely decapitating the army at the most difficult and tense moment,” Popov said.

Russian senior officers have been taking it on the chin lately.

Another Russian General Killed in Occupied Ukraine

Russian Lieutenant General Oleg Yuryevich Tsokov was reportedly killed in an overnight attack by Ukrainian forces in the city of Berdyansk. The information was confirmed on the Telegram channel of the mayor of Mariupol, Peter Andryushchenko, and then by an advisor to the Minister of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, Anton Gerashchenko, on Twitter.

Later Andryushchenko suggested that this had been an attack against the “Duna Hotel” which had been commandeered as accommodation for the Russian military leadership in the occupied town. According to local reports, cited by the mayor, the hotel was all but completely destroyed in spite of reports that anti-missile defenses were sited close to the building. Unconfirmed reports say the building may have been struck by a Storm Shadow missile.

Cheers to the UK for supplying Ukraine with Storm Shadow missiles! 🍻🇬🇧

Russian commander killed while jogging may have been tracked on Strava app

A Russian submarine commander shot to death while jogging on Monday may have been targeted by an assailant tracking him on a popular running app, according to Russian media.

Stanislav Rzhitsky was killed earlier this week in the southern Russian city of Krasnodar by an “unknown person,” state news agency TASS reported, adding that “the motive for the crime is being investigated.”

[ ... ]

Russian media earlier reported that Rzhitsky’s killer may have used Strava, a widely available app used by runners and cyclists, to follow his movements.

Yes, this is yet another idiotic lapse in basic security by Russians. Rzhitsky was essentially broadcasting to the world his exact location with an exercise app.

Top Russian General Missing Since Mutiny Is ‘Currently Resting,’ Lawmaker Says

Russian General Sergei Surovikin, the deputy commander of Russia’s war in Ukraine—who is also known to have ties with Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin—is “currently resting” and “not available for now,” said a lawmaker from Russia’s ruling party.

The comment came in response to questions Wednesday about Surovikin’s whereabouts.

Surovikin, who is known in the Russian media as “General Armageddon” due to the tactics he used in the bloody Syrian civil war, is one of several notable Russian military leaders who have not been seen in public since Wagner’s aborted mutiny last month.

Of course the place where "General Armageddon" is resting could very well be a gulag.

While regular press freedom no longer exists in Russia, there is still a rather robust exchange of information on Telegram. This news of chaos and incompetence among the top military leadership will gradually filter through much of the population – including the cannon fodder at the front.

#invasion of ukraine#russia#pandemonium in russia's military establishment#ivan popov#sergei shoigu#oleg tsokov#stanislav rzhitsky#sergei surovikin#general armageddon#vladimir putin#strava app#wagner mutiny#россия#мятеж#некомпетентность#владимир путин#путин хуйло#армия россии#олег цоков#иван попов#сергей шойгу#станислав ржицкий#сергей суровикин#генерал армагеддон#россия проигрывает войну#геть з україни#вторгнення оркостану в україну#україна переможе#слава україні!#героям слава!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

On June 23, the Russian warlord, mercenary, and billionaire Yevgeny Prigozhin, whose Wagner troops had performed with brutal resilience in the war against Ukraine, led his men in a short-lived mutiny against his patron, Russian President Vladimir Putin. Prigozhin seemed to be demanding the dismissal of the defense minister, Sergei Shoigu, and the chief of staff, Gen. Valery Gerasimov. Putin denounced him for treason. But having seized Rostov-on-Don and marched on Moscow, Prigozhin accepted the mediation of another Putinite courtier, Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko.

Putin celebrated with a military parade in the Kremlin, attended by Shoigu, while several senior officers were dismissed for criticizing the conduct of the war. Some, apparently including his most competent fighting general, Sergey Surovikin, disappeared, possibly arrested for acquiescing in Prigozhin’s plans. At the time of writing, Shoigu and Gerasimov remain in command of the war in Ukraine. Meanwhile, at a meeting with Wagner officers at the Kremlin on June 29, Putin received Prigozhin, whom he had called a traitor less than a week before. Perhaps it was a recognition that Wagner had fought so well for the motherland.

We outsiders know little of the real intrigues of a personalized autocracy in which a vast state is ruled by a tiny clique under a single despot. There are many ways to analyze the Prigozhin mutiny and the strange maneuvers since. In this, history can be usefully revealing—but never the final word.

This certainly was the old story of a mercenary captain demanding gold and guns for his warriors. On the political spectrum, the mutiny reveals the dissident pressure from nationalist-imperialists within the elites who believe Putin has not waged war fiercely enough. More broadly, it exposes the eternal problem in dictatorships: In a system where real opposition is forbidden, conspiracy is the only way to register protest or promote change.

In terms of factional conspiracy, this represents a stage in the perhaps gradual crackup of an autocrat’s system of playing his magnates against each other. It undoubtedly exposes the creaking of an entire corrupt, incompetent klepto-bureaucracy faced with the brutal and brutalizing stress of a terrible, unnecessary, and atrocious war.

In the court politics of an embattled, isolated tsar, this revolt heralds the betrayal, both hurtful and hazardous, of a friend and protégé who had been promoted and enriched at the ruler’s whim and had proved more efficient, more loyal, and more ferocious a warrior than many of the ruler’s bureaucratic cronies.

Autocrats hate to lose favorites, for they are creatures created by the ruler and therefore meant to be blindly loyal: Such loyal outsiders are hard to find and to replace. But when they cease to be that, they lose their purpose. They are ultimately dispensable.

Though dictators have few friends, and Putin is not famed for his sentimentality, many of his favorites are childhood friends, or like Prigozhin, people he met in the early 1990s in St. Petersburg. Putin has not lightly dropped or liquidated such characters, and that may explain the extraordinary meeting with Prigozhin in the Kremlin after the mutiny—and why Prigozhin is still walking the earth.

The other reason is the war, Prigozhin’s unique role in it, and the historically perilous relationship between Russian rulers and their paladins. The bizarre tale of Prigozhin is best understood through the prism of how tsars relate to their military leaders.

Every Russian ruler since the early 18th century has struggled to find a balance between the essential themes of military leadership in Russia: the necessity to play the victorious supreme commander, and the suspicion that the army is potentially disloyal and possibly a deadly threat.

On the first point, it is clear by now that Putin is no general. Every stage of his planning during the invasion of Ukraine has gone horribly wrong, from the first blitzkrieg to take Kyiv in a week to the southern push to seize Odesa. He has repeatedly promoted, undermined, backed, and sacked ministers, commanders, spymasters, and warlords; Putin has meddled clumsily in every detail, high and low, at a terrible cost.

The conventional wisdom, repeated in the Western press, is that Putin is just inexplicably a micromanager, obsessive control-freak, and omnipotent meddler.

But it is much more fundamental and institutional than that. Like most of his predecessors, Putin sees it as his mission and his duty as Russian ruler to command in battle. The reason is not just the poison fruit of Putinesque vanity and obstinacy. It a role that is deeply ingrained within the founding myth of Putin’s regime and even deeper inside the creation of modern Russia: Putin believes that a Russian autocrat is not just a political ruler, but also must be a military commander. He aspires to be the presidential emperor and supreme commander who reconquered Crimea and Ukraine and restored the Russian imperium.

This can be traced to the founding charter of modern autocracy. In 1613, when the Romanov dynasty was raised to the throne, Russia was a failed principality, the Grand Duchy of Muscovy. Since the extinction of the Rurikid dynasty in 1598, it had been carved up by carnivorous neighbors: Sweden, Poland, and the Tatar khanate that ruled southern Ukraine and Crimea.

This was the Smuta, or Time of Troubles, the first of the three traumatic spasms of chaos (the others are the civil war of 1918-20 and humiliations of the 1990s) that have justified resurgent autocracy in Russia. The first Romanov tsar, effectively elected by an assembly of different interests, was a sickly teenager named Michael whose family was linked to the old Rurikids, but the dynasty came to power promising to restore the kingdom and expel the invaders.

As the Romanovs succeeded in their mission and rapidly switched to expansion, their court developed as a military headquarters. The third Romanov tsar, Peter the Great, took this even further, dressing in Germanic military uniform and mastering the details of artillery, infantry, and shipbuilding—and abortively attacking both the Ottomans and Tatars in southern Ukraine and the Swedes in the north.

Faced with first defeat and then invasion by the Swedes, he reformed his army and then actually commanded it in battle to rout the invaders at Poltava in 1709. Peter was far from a military genius: When he personally led an expedition against the Ottomans in July 1711 he was defeated and very nearly destroyed. But he succeeded in the north, defeating the Swedes, conquering the Baltic, and founding St. Petersburg and a Russian fleet, victories he celebrated by granting himself the Roman title imperator, or commander, and rebranding Muscovy as an empire that he renamed Roosiya.

Russia was founded as an expansionary empire; its tsar remodeled as a conqueror. Every one of Peter’s successors aspired to command in war, and most of them spent all of their time in uniform, often personally drilling soldiers. But the role is both a mixed blessing and poisoned chalice: It is essential, and yet to fail at it can be catastrophic.

Peter’s female successors promoted favorites to command in battle since they could not do so themselves: Catherine II’s romantic and political partner, Prince Potemkin, the greatest statesman of the Romanov centuries, secured new conquests—southern Ukraine and Crimea, and a protectorate over Georgia. Her son Paul was a disastrously inconsistent commander in chief, while his son Alexander I made a fool of himself against Napoleon at Austerlitz, then yielded command, humiliatingly, to the popular Gen. Mikhail Kutuzov; the emperor then commanded the Russian army all the way to take Paris.

Even Nicholas II lived in uniform, aspired to be commander in the Russo-Japanese War, and took command in World War I—so calamitously that it led, in part, to revolution. Yet Russia’s new rulers aspired to this tradition as much the old: The provincial lawyer Alexander Kerensky was never out of military uniform; the Georgian cobbler’s son and Bolshevik activist Joseph Stalin believed from youth that he was born to command.

During World War II, Stalin controlled every military detail of the Soviet war against Hitler, even to the extent of keeping a notebook with a tally of individual tanks during the Battle of Moscow. He lost millions of men in the first year of the war, many of these deaths caused by his ignorant bungling. But ultimately, at the terrible cost of 27 million people, Stalin fought all the way to Berlin.

That victory of 1945 ensured the Soviet Union survived for another 40 years and intensified the military pretensions of Russian rulers.

After the humiliating collapse of Soviet superpowerdom, marked by withdrawal from Eastern European vassal-states and the loss of 14 former Russian imperial territories reconstituted as Soviet republics, Putin doubled down on the necessity of military success: His regime commandeers the prestige of Soviet victory in 1945, conjuring himself as the actual supreme commander. His minor victories in Chechnya, Georgia, and Syria seemed to confirm that he had the gift. But his vision of himself as supremo has set himself an impossibly high threshold—and the price of defeat and stalemate in his Ukrainian war of choice have made regime security as important as military victory—or more so.

In 1698, when he was in London on his Grand Embassy mission, Peter the Great faced a mutiny by the Kremlin musketeers that he crushed brutally, breaking up that obsolete force and creating his own regiments of new-model guards that remained the Romanov dynasty’s praetorians until the end of the regime. Yet the guards, like their Roman equivalents, regularly backed their own candidates for tsar, as they did on his death in 1725 with his widow Catherine I. Later they overthrew tsars, most famously in the coups of 1741, 1762, and 1801.

In 1825, elite officers launched the Decembrist rebellion against autocracy itself, only to be crushed by Nicholas I, who created the organs of secret police in part to investigate and prevent military revolts. In February 1917, while a spontaneous uprising seized the streets in Petrograd, it was the generals who forced Nicholas II to abdicate. Later that year, his successor, Kerensky, was almost destroyed by his commander Gen. Lavr Kornilov.

Russia’s modern rulers inherited that distrust of military esprit and Bonapartist ambition in their generals, whom they feared might build a Napoleonic-style military regime with popular support—using political commissars and special military sections of their new security organs, the Cheka, NKVD, KGB, and today’s FSB—to terrorize and surveil military officers.

As early as 1930, Stalin was mulling a blood purge of top military officers that he enacted in 1937 when he executed more than 40,000 officers and three of the five marshals, including two of the most brilliant, Mikhail Tukhachevsky and Vasily Blyukher, who were tortured and murdered savagely. Instead he promoted inept cronies from his civil war days, led by Marshals Kliment Voroshilov and Grigory Kulik.

Only later in the war did Stalin sack these bunglers and promote a brilliant team led by Georgy Zhukov, but he never fully relaxed his military terror: He allowed his secret police minister, Lavrentiy Beria, to investigate and arrest generals while building up a separate phalanx of special NKVD military forces—his own praetorians. Some of his generals, most famously Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, literally came from prison to Stalin’s headquarters when the war required talented officers—and had to sit in the dictator’s office with Beria, who had personally tortured him.

After the war, Stalin demoted Zhukov to command the Odesa and the Urals military districts while deliberately promoting political hacks to military rank. (Beria and Nikolai Bulganin were marshals.) After his victory at Stalingrad, Stalin himself never appeared in public out of his marshal’s uniform. On Stalin’s death, Zhukov turned the tables on the secret police when he backed Nikita Khrushchev’s arrest—and later, execution—of Beria.

In 1957, he again backed Khrushchev against Stalin’s grandees Vyacheslav Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich. But Khrushchev also feared Zhukov, sacking him and accusing him of Bonapartism. Later, Khrushchev tried to arrange his own promotion to marshal of the Soviet Union—and when his equally unmartial successor, Leonid Brezhnev, secured his own promotion to that rank, he danced to celebrate it.

During the 1990s, President Boris Yeltsin, whose prestige was ruined when the great Russian army was defeated by ragtag Chechens in the streets of Grozny, was forced temporarily to turn to an overmighty paratrooper, Gen. Alexander Lebed, who had run against him in the 1996 election. Lebed, too, was accused of Bonapartism and sacked.

Zhukov and Lebed are the examples who would be on Putin’s mind in the more than 500 days of the Ukraine war. To avoid potential rivals, Putin promoted Shoigu and Gerasimov, his own version of Stalin’s inept cronies.

Every Russian ruler must exist in a perpetual state of ferocious vigilance, paying paramount attention to personal security. Stalin constantly purged and shuffled his security grandees, always keeping his personal security under his own control. His successors, even Yeltsin, did the same: Yeltsin’s devoted bodyguard, Alexander Korzhakov, was promoted to general and top aide until he overreached. Putin has studied these lessons, recalling how Fidel Castro, the long-serving Cuban dictator, told him how he had survived many assassination attempts by always keeping personal control of his security.

Putin has promoted his former bodyguard Viktor Zolotov to command the huge National Guard (Rosgvardiya) that is his shield against military threats. Yet at the same time, the failure to take Kyiv or Odesa and hold Kherson has revealed the cloddish incompetence of his chosen military leaders.

Putin’s entire system, not unlike that of the tsars and general-secretaries before him, resembles a court in which magnates are rewarded and promoted, then played against one another. The ruler is the supreme adjudicator. Even though Russian despots seek and reward loyalty above all other qualities, they still value and promote competence too.

Every Russian ruler has to deal with the knowledge that their bureaucrats are often cautious, corrupt, and incapable of initiative. To get things done, rulers turn to dynamic favorites, former outsiders who become intimate insiders empowered to exert pressure on vested elites. That is where Prigozhin came in.

Favorites tend to reflect the rulers they serve: Peter’s Prince Alexander Menshikov was as brutal and dynamic as his master; Catherine’s Potemkin the same combination of enlightenment, empire, and vision as she. Alexander I, disenchanted by the liberal dreams of his youth, promoted a glowering brutal disciplinarian in Gen. Alexei Arakcheev as his effective deputy, who loved to declare: “I am the friend of the tsar, and complaints about me can be made only to God.” Nicholas II’s Grigori Rasputin mirrored the weakness and mysticism of his tsar.

Prigozhin reflects Putin’s nature, too—but he was, for all his criminal record, his rise in catering, and his brutal nature, a doer: When Putin wanted to create troll farms to undermine Western democracies, Prigozhin did it; when he wanted a deniable, cheaper military force, Prigozhin created the Wagner Group that helped achieve victory in Syria and push Russian interests in Africa.

When Putin made the dire decision to attack Ukraine, Prigozhin enthusiastically embraced the war, and shaming the venal bureaucrats and military pencil pushers Shoigu and Gerasimov, he shaped Wagner as a Russian storm force. Putin’s promotion of an independent unit and its warlord was itself a sign of state weakness—and lack of confidence in his own military.

The failure to promote an effective general to fight the Ukraine war is one of Putin’s most egregious lapses. Indeed, one of the chief duties of the war leader is to select generals who can win victories and remove those who can’t. Even Stalin, after many defeats, backed Zhukov and other talented generals. Putin has either never found that talented general, or more likely, so fears the threat of one that he has preferred stalemate to the peril of a victory won by someone else. Gen. Sergey Surovikin, for example, was promoted to commander in Ukraine, then removed.

Fearing that a successful rival general could provide an alternative potentate around whom his courtiers could rally, Putin instead empowered Prigozhin to promote himself and attack the military hierarchy as slothful and crooked while he emulated Stalin’s penal battalions of World War II by recruiting criminals from Russian prisons; Prigozhin flaunted his devotion to the motherland, having deserters executed with his trademark sledgehammer. Tempered and bloodied by the cruel battles at Bakhmut and elsewhere, and possibly liberated by his own struggle with cancer, Prigozhin started to believe himself a Russian paladin hamstrung by deskbound cowards and a sclerotic autocrat.

Prigozhin was serving in a classic role as a way to intimidate the military command, but unlike Stalin’s Beria, this ferocious, loudmouthed military amateur was also winning admiration from some generals, possibly including Surovikin.

But ultimately, it was unlikely that Putin would choose an amateur condottiero and his small force of Wagnerians over the huge Russian army. In the end, he was always going to back the army. And he did so, allowing his officials to cut off Wagner’s ammunition and its budget. But Putin failed to perform his essential role of balancing his magnates, apparently refusing to talk to Prigozhin—who turned to desperate measures.

Putin now finds himself the prisoner of the conundrum of despot as supreme commander and security sentinel. His dream of imperial greatness has become a fatal trap. His weakness now means that any retreat from command could lead to a hemorrhage of power.

Every autocrat competes with gilded and titanic ghosts of imperators past. In 1945, when U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union Averell Harriman congratulated Stalin on taking Berlin, the dictator replied, “Yes, but Alexander took Paris.” Putin could not hold Kherson.

Few autocrats can be Peter or Stalin, but Putin dreams of such victories. His dilemma—a tsar’s inability to balance his roles as military commander and political survivor—is also Ukraine’s tragedy. When dictators aspire to empire, many innocents bleed; when they fail, they take whole, innocent peoples down with them.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

President Vladimir Putin announced on Wednesday that Russia would impose martial law in the four regions in Ukraine he illegally annexed last month, as his military struggles to maintain its grip on territory amid Ukrainian advances.

“Now we need to formalize this regime within the framework of Russian legislation. Therefore, I signed a decree on the introduction of martial law in these four subjects of the Russian Federation,” Putin said on national television.

Speaking to his National Security Council, Putin announced the immediate declaration of martial law in Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Luhansk and Donetsk, as well as the establishment of a new state coordination council aimed at fulfilling the objectives of his so-called special military operation.

Last month, the four regions held controversial referendums on whether to join Russia. These were widely criticized as illegitimate by the international community, and Ukraine. Some residents alleged that they were intimidated or otherwise forced into voting, and that the outcome of the vote was preordained.

Despite these criticism, Putin went ahead with formal annexation of the four regions at the end of September.

On Wednesday, Putin also signed an order introducing some elements of wartime measures to recognized regions bordering Ukraine — such as Crimea, Belgorod, Voronezh, Kursk, and Rostov, among others. Several of the regions have been important staging areas for Russia’s war in Ukraine and in recent weeks have come under increasing Ukrainian fire.

The order allows for unspecified economic mobilization in these regions, as well as seemingly laying the groundwork to organize local residents to support the military and security services. Much about the measures signed on Wednesday are vague and give the state more legal room to maneuver.

INTENSE WEEK OF COMBAT

Putin's announcement follows an intense week of combat in Ukraine. Russian forces, in response to the bombing of a key bridge to Crimea, have launched waves of missile and "kamikaze" drone strikes across Ukraine, killing civilians in cities and villages and seriously damaging critical infrastructure such as power stations.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said on Tuesday night that Russia’s latest turn in strategy — the use of stand-off missiles and drones against infrastructure and other targets far from the front — has taken 30% of his nation’s power plants offline since the strikes began on Oct. 10. Russian officials have warned that more is come.

The war has reached a critical impasse. Ukrainian forces continue their advance on Russian positions in eastern Ukraine, particularly the critical city of Kherson. Local Russian-installed officials have begun to sound the alarm on a potential Russian retreat from the city, warning civilians that the time has come to abandon the city.

The Kremlin-appointed deputy governor of Kherson, Kirill Stremousov, said that Ukrainian forces, supported by the West, would “start an offensive” against the city in the near future.

“I ask you to take my words seriously, and to understand them as meaning as prompt an evacuation as possible,” he said in a video message addressed to Kherson residents Wednesday.

Stremousov’s message follows Tuesday night’s appearance on state television of Russia’s new general in charge of what the Kremlin still insists on calling its “special military operation” in Ukraine. It is rare for a Russian general in any situation, let alone one at the helm of the nation’s largest military action since the Second World War, to give an interview.

Gen. Sergei Surovikin, who some have credited with masterminding Russia’s new strategy of bombing Ukraine into submission, signaled to the public that the situation for Russian forces in Kherson was on shaky ground — but that no matter what happens, military leadership was taking measures to ensure the safety of civilians in the region.

“Our further plans and actions regarding the city of Kherson will depend on the unfolding military and tactical situation. I repeat — it is already very difficult [the situation] today,” Surovikin said. “We will act consciously, in a timely fashion, and will not rule out taking the most difficult decisions.”

Some interpreted Surovikin’s remarks as preparing for a Russian retreat from Kherson, a city that has become a critical focal point in the war. Ukrainian victory in Kherson would potentially bring Crimea within striking distance of Ukraine’s long-range weapons — a situation that would drastically raise the perceived stakes for Putin.

#news#imperial russia#Russia#russian federation#russo ukrainian war#ukrainian crisis#ukriane#stand with ukraine#vladimir putin#volodymyr zelensky#martial law#annexation#Kherson#Zaporizhzhia#Luhansk#Donetsk#Crimea#Belgorod#Voronezh#Kursk#Rostov#Kirill Stremousov#Gen. Sergei Surovikin#war#world politics#world news#2022#nbc news

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Over the years, with his connections to Mr. Putin and the Kremlin, Mr. Prigozhin was able to secure lucrative contracts to provide food for the Moscow school system and Russian military bases, amassing great wealth. At the same time, he engaged in foreign adventurism through Wagner that suited the Kremlin, advancing Moscow’s aims — and his own — in the Middle East and Africa, where his fighters have been accused of indiscriminate killings and atrocities.

He also shepherded the Internet Research Agency, the infamous St. Petersburg troll farm that interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

So secretive was Mr. Prigozhin about his activities that he long denied any association with Wagner and even sued Russian media outlets for reporting on his connection to the group.

All that changed last year with the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In September, Mr. Prigozhin went public for the first time as the man behind Wagner.

Less than two weeks later, Mr. Putin appointed Gen. Sergei Surovikin to lead the war effort in Ukraine, a boon for the mercenary chief, who had worked with the general in Syria. Mr. Prigozhin described the new leader as a legendary figure and the most capable commander in the Russian army.

Mr. Prigozhin’s own stature was growing, too, as his fighters appeared to be making progress in the drawn-out battle for the Ukrainian city of Bakhmut, while the Russian military had little to show. . Russian commentators lavished positive coverage upon the mercenary group, and a glass tower in St. Petersburg was rebranded Wagner Center. Recruitment posters for the outfit went up across the country.

But by the beginning of this year, Mr. Prigozhin’s adversaries in the Ministry of Defense began reasserting their power.

In January, Mr. Putin appointed Gen. Valery V. Gerasimov, to replace General Surovikin as the top commander of operations in Ukraine. Mr. Prigozhin frequently belittled General Gerasimov in his Telegram audio messages, implying that he was an office-bound official of the kind that smothers regular soldiers with bureaucracy.

The enmity appears to date at least to Moscow’s intervention in Syria’s civil war, when Wagner and regular Russian soldiers sometimes clashed as they competed for resources and the spoils of war, according to the published memoirs of two Wagner veterans. Mr. Prigozhin himself went public about these tensions in Syria last year.

In February, Mr. Prigozhin acknowledged that his access to Russian prisons to recruit had been cut off. The Defense Ministry would later begin recruiting prisoners there itself, adopting Mr. Prigozhin’s tactic.

Tension between Wagner and the Russian military — long alluded to by Russian military bloggers — exploded into the open. By the end of February, Mr. Prigozhin was publicly accusing Mr. Shoigu and General Gerasimov of treason, claiming that they were deliberately withholding ammunition and supplies from Wagner to destroy it.

At the end of February, Mr. Putin tried to settle the feud by calling Mr. Prigozhin and Mr. Shoigu into a meeting, according to leaked intelligence documents .

But the rivalry would only escalate. No longer able to recruit prisoners, Wagner was forced to rely increasingly on its limited supply of skilled veteran fighters to continue waging battle in Bakhmut, according to Ukrainian and Western officials.

Isolated from the Moscow power center, Mr. Prigozhin increasingly turned to his bully pulpit: social media. His messages also grew far more political as he began appealing directly to the Russian people. He began voicing criticisms that, in a country with a law against discrediting the armed forces, few others dared make.

What had once been sharp-tongued trolling of the Russian brass over time turned into regular eruptions of bile.

“You stinking beasts, what are you doing? You swine!” he said in one recording in late May. “Get your asses out of your offices, which you were given to protect this country.’’

He went on to lambast the Russian defense leadership for “sitting on their big asses smeared with expensive creams” and to say the Russian people had every right to ask questions of them. He posted gruesome images of Wagner soldiers killed in action. He gave ultimatums about pulling his troops out of Bakhmut. He even took what was widely viewed as a swipe at Mr. Putin, without naming him, with a reference to a “grandpa’’ who might be “a complete jackass.‘’

Kremlinologists were puzzled as to why Mr. Putin did not just sweep the Wagner chief aside, or intervene and rein him in; some analysts suggested that he favored competing factions operating underneath him, with none gaining too much power. Others wondered if the Russian leader had become too isolated to solve the problem or simply did not have sufficient control.

Mr. Prigozhin’s forces captured Bakhmut at the end of May and soon after departed the battlefield, accusing the Russian military of mining the road they used to leave and briefly apprehending a Russian lieutenant colonel on the way out. That left Mr. Prigozhin newly vulnerable. Wagner was no longer needed to finish off a battle that had been played up by the Russian media.

By June, his isolation became palpable.

Mr. Prigozhin signaled a rift with the Ministry of Defense over his military catering contracts, which have helped fuel his wealth and influence for more than a decade. In a publicized letter to Mr. Shoigu dated June 6, Mr. Prigozhin said the food he had supplied to Russian military bases and institutions since 2006 had amounted to a total of 147 billion rubles — $1.74 billion — a figure that is impossible to verify. Now, he complained, “high-level people” were trying to force him to accept companies associated with them as his suppliers. He also said a new system of “loyal suppliers”threatened his cost structure and could deliver a blow to his business reputation.

His desperation seemed to be growing.

On June 10, one of Mr. Shoigu’s deputies announced that all formations fighting outside the Russian military’s formal ranks would need to sign a contract with the Russian Defense Ministry by July 1.

Mr. Prigozhin initially refused, but then Mr. Putin backed Mr. Shoigu’s plan. In the days that followed, Mr. Prigozhin released several audio and video messages showing what appeared to be attempts to reach a deal on his terms.

In one video, published on June 16, he shows himself delivering a “contract” to the Ministry of Defense in Moscow, but a receptionist behind a caged booth quickly closes the window in his face.

In the days before he led Saturday’s uprising, Mr. Prigozhin began expressing feelings of resignation, saying that none of the problems plaguing the Russian military would be fixed. He also talked about the nation rising up, saying that Mr. Shoigu should be executed and suggesting that the relatives of those killed in the war would exact their revenge on incompetent officials.

“Their mothers, their wives, their children will come and eat them alive when the time comes,” he said in a June 6 video interview, suggesting there might be a "popular revolt.”

He added, “I can tell you, honestly, I think we have only about two to three months before the executions.”

#current events#politics#russian politics#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#yevgeny prigozhin#vladimir putin#sergei shoigu#wagner group

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily Wrap Up July 6, 2022

Under the cut: Russia has made ‘genuine headway’ after capturing Lysychansk, say western officials; According to the NASA Harvest mission, Russia currently controls approximately 22% of Ukraineʼs agricultural land; The evacuation of civilians from Sloviansk continued on Wednesday as Russian troops pressed towards the eastern Ukrainian city in their campaign to control the Donbas region; Approximately 7,000 to 8,000 people remain in the eastern city of Severodonetsk but in the near future they will live in “awful conditions” with no water, gas or power supply; A Bayraktar drone that was originally crowdfunded but then donated to Ukraine by the Bayraktar company will reach Ukraine soon; Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia to buy grain from Ukraine's occupied Zaporizhzhia region;

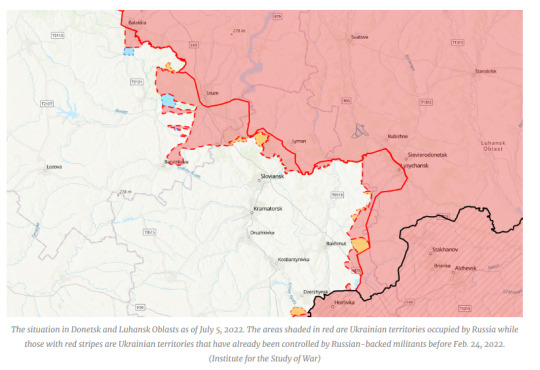

Map from The Kyiv Independent.

“The capture of the city of Lysychansk in eastern Ukraine by Russian forces has meant Moscow has made “genuine headway”, while its forces in the south have shown signs of “better cooperation”, western officials said.

Western officials said the sustainability of Russia’s attacks on Ukraine was “challenging”, but described the impact on their munitions and morale as “remarkable”.

But one official said it “remains highly uncertain whether Russia will secure the limits of Donetsk oblast this year”.

Russia has made “some significant command changes” in recent weeks, one official said, notably the recently appointed Gen Sergei Surovikin, who has taken over command of the southern group of forces overseeing the occupation of southern Ukraine and the advances on the Donbas from the south.

The official said, “He’s a controversial figure even by the standards of Russian general officers. It is unclear whether it’s his influence which has led to the recent successes around Lysychansk, but certainly there’s been better cooperation amongst groups of forces on the Russian side than we saw in the earlier phases of the war.”

There are “very serious issues” over the stocks of Russian munitions and of morale, an official said, while long-range weapons systems are starting to make a “significant operational difference for Ukraine”.”-via The Guardian

~

“According to the NASA Harvest mission (a food security and agriculture program), Russia currently controls approximately 22% of Ukraineʼs agricultural land. In these territories, mainly winter crops are grown — wheat, rye and barley.

This is stated in the analysis of NASA Harvest satellite images.

NASAʼs analysis focused on the impact of the Russian invasion on the global food system. For this, specialists took data from Planet Labs satellites and the Sentinel-2 mission of the European Space Agency. The result showed that the fields where 28% of winter and 18% of spring crops (including corn and sunflower) are sown are under occupation.

Ukraine supplied 46% of the worldʼs oil exports, 9% of wheat exports, 17% of barley and 12% of corn on world markets, so the occupation of Ukraineʼs lands directly leads to the food crisis. In addition, part of the fields is already unsuitable for sowing due to shells and mines in the fields.

The blockade of ports also affects the crisis. Mykolaiv, Chornomorsk, Pivdenne and Odesa, which are constantly attacked by the Russians, are the main exporters of grain, but they cannot work.”-via Babel News

~

The evacuation of civilians from Sloviansk continued on Wednesday as Russian troops pressed towards the eastern Ukrainian city in their campaign to control the Donbas region, as Ireland’s prime minister visited Kyiv to voice solidarity.

Agence France-Presse reports:

Sloviansk has been subjected to heavy bombardment in recent days as Russian forces push westwards on day 133 of the invasion.

“Twenty years of work; everything is lost. No more income, no more wealth,” Yevgen Oleksandrovych, 66, told AFP as he surveyed the site of his car parts shop, destroyed in Tuesday’s strikes.

AFP journalists saw rockets slam into Sloviansk’s marketplace and surrounding streets, with firefighters scrambling to put out the resulting blazes.

Around a third of the market in Sloviansk appeared to have been destroyed, with locals coming to see what was left among the charred wreckage. The remaining part of the market was functioning, with a trickle of shoppers coming out to buy fruit and vegetables.

-via The Guardian

More information can be found here from The Kyiv Independent.

~

“Approximately 7,000 to 8,000 people remain in the eastern city of Severodonetsk but in the near future they will live in “awful conditions” with no water, gas or power supply, Oleksandr Striuk, the head of the military administration of Severodonetsk, said Wednesday.

Russian forces destroyed the material base of housing and utility services in this key city in the Donbas region, and they are looking for staff to help restore them but almost no staff members remain in Severodonetsk, according to Striuk.

Many utility and city workers had been evacuated previously, Striuk said.

He added that Russian forces who now occupy the city are working on organizing the Education Department for children to go back to school starting on Sept. 1.”-via CNN

~

“A Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drone, secured by Lithuania for Ukraine after a local crowdfunding campaign, is expected to be shipped to Kyiv in the coming hours.

The “Vanagas” (which means "Hawk" in Lithuanian), along with ammunition, arrived in the Baltic country on Monday, the country’s Defense Minister, Arvydas Anušauskas, tweeted. After a press introduction on Wednesday, Anušauskas added the drone would be transferred to Ukraine soon.

“Last hours of Bayraktar “Vanagas” in Lithuania. Very soon it will be delivered to Ukraine,” he tweeted.

The crowdfunding campaign was launched by Lithuanian online broadcaster Laisves TV last month and was able to secure around 6 million euros ($6.11 million) to purchase the drone.

The purchase was organized by the Lithuanian Defense Ministry, but it says that after learning it was being purchased via a crowdfunding campaign, the manufacturer donated the drone for free.

“Citizens of Lithuania collected funds for this aircraft, but inspired by the idea, the Turkish company 'Baykar', the manufacturer of 'Bayraktar', decided to donate it,” the Lithuanian Defense Ministry said in a statement. “1.5 million euros of the donated 5.9 million was allocated for arming the unmanned aircraft.”

It is not the first time Baykar has donated some of its drones to the Ukrainian armed forces. Last month, after a Ukrainian crowdfunding campaign secured enough funds to purchase three of the drones, the company said it would be donating them for free.

“We ask that the raised funds be remitted instead to the struggling people of Ukraine,” it said in a statement on June 27.”-via CNN

~

“Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia to buy grain from Ukraine's occupied Zaporizhzhia region.

Yevgeny Balitsky, head of the Russian-imposed administration of the occupied Zaporizhzhia region of Ukraine, has said the region plans to sell Ukraine’s grain to the Middle East, according to reports from Russian news agency Tass.

Tass said that the main countries involved in the deal were Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia. Ukraine has repeatedly accused Russia of stealing grain, a charge which Moscow has denied.

Yesterday, a senior Turkish official said Turkey had halted a Russian-flagged cargo ship off its Black Sea coast to investigate a Ukrainian claim it was carrying stolen grain.”-via The Guardian

#daily wrap up#ukraine#war in ukraine#russia#lithuania#Lysychansk#NASA#slovyansk#Sloviansk#Severodonetsk#sieverodonetsk#Zaporizhzhia

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep21045#metadata_info_tab_contents%20tigere%E2%80%99%20and%20armageddon

:::

Via:

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sergei Surovikin, Russian General Detained After Wagner Mutiny, Is Released

Gen. Sergei Surovikin, who was seen as an ally of the mercenary leader Yevgeny V. Prigozhin, has re-emerged in public.

source https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/04/world/europe/general-sergei-surovikin-russia.html

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: Top Russian General Detained After Wagner Mutiny Is Released by Paul Sonne, Anatoly Kurmanaev and Julian E. Barnes

By Paul Sonne, Anatoly Kurmanaev and Julian E. Barnes

Gen. Sergei Surovikin, who was seen as an ally of the mercenary leader Yevgeny V. Prigozhin, has re-emerged in public.

Published: September 4, 2023 at 04:10PM

from NYT World https://ift.tt/gr4y1uS

via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

[ad_1] Reports that a Russian general who has been missing from the public eye since the Wagner Group uprising has now been fired could be a Russian disinformation operation.The fate of Russian Gen. Sergei Surovikin, who earned the nickname "General Armageddon" while serving as the head of the air force, has been the subject of intense speculation since the officer disappeared from public view in recent months, with new reports earlier this week indicating Surovikin has been fired by the Kremlin.But Rebekah Koffler, a strategic military intelligence analyst, former senior official at the Defense Intelligence Agency and author of "Putin’s Playbook," told Fox News Digital that such reports could be part of a disinformation operation from the Kremlin."What struck me about the Surovikin story is that it originated from a Russian source, and then, within minutes, it spread all across major Russian media like wildfire. Remember, most if not all Russian media are controlled by the state," Koffler said.UKRAINE MARKS INDEPENDENCE DAY WITH PROMISES TO CONTINUE ITS FIGHT AGAINST RUSSIA Gen. Sergei Surovikin, left, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, center (Gavriil Grigorov/Sputnik/AFP via Getty Images)According to a report from Reuters on Wednesday, news of Surovikin's dismissal was first reported by Russian state news agency RIA, which cited an "unnamed but informed source." The source, according to the report, told RIA that Surovikin "has now been relieved of his post, while Colonel-General Viktor Afzalov, head of the main staff of the air force, is temporarily acting as commander-in-chief of the air force."The RBC news outlet in Russia later reported the same, citing two unnamed sources that were familiar with the situation, though the Kremlin has yet to publicly announce Surovikin's dismissal.Those reports have been widely circulated by media in the U.S., something Koffler said could be intentional."This story has the hallmarks of a Russian tradecraft called 'information confrontation,' which is intended to confuse the opponent, divert his attention and stretch his resources, especially our intelligence resources that would otherwise be focused on the real Russian target that matters – today, it’s the battlefield in Ukraine and Putin’s decision-making process, plans and intentions," Koffler said.Such a strategy would not be the first time the Kremlin used such a tactic, Koffler said, noting her previous experience with similar stories while a member of the intelligence community."Senior officials in the White House and the Pentagon would read something in the press and would constantly ping us with silly questions," Koffler said. "Then, instead of actually focusing on the actual target, such as Russian warfighting doctrine, war plans, weapons systems, we would be chasing a wild goose."UKRAINIAN PRESIDENT VOLODYMYR ZELENSKYY THANKS DANISH LAWMAKERS FOR SENDING WARPLANES AS RUSSIAN WAR CONTINUESKoffler argued that the Russians are aware of the pressure U.S. politicians face from reports that circulate in the media, something the Kremlin seeks to take advantage of when spreading information."Our leaders have to explain things to Congress, which is also very susceptible what’s reported in the media. So, the Russians exploit that by throwing what they call a ‘duck’ (utka), ‘spray in the information stream,’" Koffler said. "It’s a rough equivalent of a 'red herring' in English."But Robert Peters, a research fellow for the Center for National Defense at the Heritage Foundation, told Fox News Digital that the timing of the firing is likely not a coincidence.Pointing to the recent possible death of Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the Wagner Group private military company, in a plane crash this week, which many observers believe was an intentional act by the Kremlin, Peters argued that the Kremlin is sending "a message … to the people of Russia, and really to all his top military commanders, that he remains the czar of all Russians, and if someone tries to take a run at him, and they're not successful, then justice will come for them."Some U.S. officials believed in June that Surovikin may have been supportive of Prigozhin, the Reuters report said, though intelligence was unclear whether the top general in any way assisted the recent, aborted Wagner rebellion. Yevgeny Prigozhin (Razgruzka_Vagnera telegram channel via AP)Surovikin's last public appearance was June 24, the last day of the Wagner mutiny, appearing in a video to encourage Prigozhin to halt his fighters' advance on Moscow. His sudden absence and potential firing could be a blow to Russian President Vladimir Putin's war effort in Ukraine, some Western military experts believe, noting the general's reputation for competence that goes back to Russia's military operations in Syria.RUSSIAN WAGNER GROUP WARLORD PRIGOZHIN AMONG DEAD ON PLANE THAT CRASHED, KILLING 10, OFFICIALS SAYOnce a recipient of Russia's top military award, Surovikin has long been believed to be one of Russia's top officers by both Russian and Western military experts. Surovikin was once the commander of Russia's overall war effort in Ukraine, but he could have fallen out of favor with the Kremlin during the Wagner revolt, according to the Reuters report. Russian President Vladimir Putin presents an award to Gen. Sergei Surovikin, the commander of Russian troops in Syria, during a ceremony at the Kremlin in Moscow on Dec. 28, 2017. (Alexey Druzhinin/Sputnik/AFP via Getty Images)Peters argued that Surovikin may have fallen out of favor with Putin long before the failed mutiny, pointing to the fact that the top general was removed from his post as commander in Ukraine just three months into his stint."Surovikin has been on the out since about January of 2023 after he failed to make any significant movements in the war against Ukraine," Peters said. "He only held command for about three months."Peters also argued that the Russian general may not have been as effective as some international observers believe, arguing that Putin has so far failed to find an effective officer to lead the war effort in Ukraine."Russia has been trying to build a narrative that it has the second-best military in the world, that it has modernized its forces, that it's excellent on the battlefield, and they're ready for a great power war," Peters said. "The war in Ukraine has shown that to be a lie."Peters noted that no matter who has been in charge of the effort in Ukraine, those officers have not achieved "any kind of sustained military push that gets behind enemy lines or achieves real battlefield success."WHO IS YEVGENY PRIGOZHIN?"That's a failure of command leadership," Peters said. "Russia has yet to find a commander that's able to make any real gains."Taken together with the failed mutiny, Peters argued that the Surovikin firing was more likely a direct message from Putin."I think it's hard to say that this is coincidental," Peters said. "It's 'Don't cross me. Don't try to take execute a mutiny against me and my regime. I remain in command.' I think the message is clear, this is what dictators do." Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, and Gen. Sergei Surovikin (Mikhail Klimentyev/Pool/AFP via Getty Image)But Koffler warned that the story could still turn out to be a "duck" planted by the Kremlin, which could distract U.S. intelligence from the war in Ukraine."That is what the Surovikin story might be," Koffler said. "We are all chasing it now, instead of assessing the state of play in the Russia-Ukraine war, what Putin thinks, what Zelenskyy thinks and what the prospects for peace are."However, Koffler believes it is possible that the top Russian general could reemerge down the road thanks to the trust he had previously gained with Putin.CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP"It’s unclear what Gen. Surovikin's whereabouts are at this time," Koffler said."It is plausible that Putin will reassign Surovikin to a new role. Surovikin has had Putin’s trust for the past several years. Putin personally honored Surovikin with two major awards – the Hero of the Gold Star of Russia in December 2017 for his performance in Syria and the Order of St. George III Degree in December 2022 for his performance in the ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine," she added. "I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that Surovikin will reemerge in the coming weeks in the new assignment, possibly in Ukraine, as Putin is now adding another vector of attack in northeastern Ukraine to stretch Ukrainian forces’ defenses thin." Michael Lee is a writer at Fox News. Follow him on Twitter @UAMichaelLee [ad_2]

0 notes

Text

Plane crash which may have killed Wagner chief is seen as Russia's revenge for Prigozhin's mutiny

Numerous opponents and critics of Putin have been killed or gravely sickened in apparent assassination attempts.

MOSCOW: Russian mercenary chief Yevgeny Prigozhin and top officers of his private Wagner military company were presumed dead in a plane crash that was widely seen as an assassination, two months after they staged a mutiny that dented Russian President Vladimir Putin’s authority.

Russia’s civil aviation agency said that Prigozhin and six top lieutenants were on a business jet that crashed Wednesday, soon after taking off from Moscow, with a crew of three. Rescuers quickly found all 10 bodies, and Russian media cited sources in Prigozhin’s Wagner company who confirmed his death.

US and other Western officials long expected Putin to go after Prigozhin, despite promising to drop charges in a deal that ended the June 23–24 mutiny. “I don’t know for a fact what happened but I’m not surprised,” US President Joe Biden said.

“There’s not much that happens in Russia that Putin’s not behind.”

Prigozhin supporters claimed on pro-Wagner messaging app channels that the plane was deliberately downed, including suggesting it could have been hit by an air defence missile or targeted by a bomb on board. These claims could not be independently verified. Numerous opponents and critics of Putin have been killed or gravely sickened in apparent assassination attempts.

Speaking to Lavian television, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence Director Janis Sarts said that “the downing of the plane was certainly no mere coincidence.”

The crash came the same day that Russian media reported that Gen. Sergei Surovikin, a former top commander in Ukraine who was reportedly linked to Prigozhin, was dismissed from his post as commander of Russia’s air force. Surovikin hasn’t been seen in public since the mutiny, when he recorded a video address urging Prigozhin’s forces to pull back.

Police cordoned off the field where the plane crashed as investigators studied the site. Vehicles were seen driving in to take the bodies, reportedly badly charred, for a forensic exam.

At Wagner’s headquarters in St. Petersburg, lights were turned on in the shape of a large cross. Prigozhin’s supporters brought flowers to the building in an improvised memorial. While countless theories about the events swirled, most observers saw Prigozhin’s death as Putin’s punishment for the most serious challenge to the authority of his 23-year rule.

Tatiana Stanovaya, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, said on Telegram that “no matter what caused the plane crash, everyone will see it as an act of vengeance and retribution” by the Kremlin, and “the Kremlin wouldn’t really stand in the way of that.”

“From Putin’s point of view, as well as the security forces and the military — Prigozhin’s death must be a lesson to any potential followers,” Stanovaya said in a Telegram post.

In the revolt that started on June 23 and lasted less than 24 hours, Prigozhin’s mercenaries swept through the southern Russian city of Rostov-on-Don and captured the military headquarters there without firing a shot, before driving to within about 200 kilometres (125 miles) of Moscow.

Prigozhin had called it a “march of justice” to oust the top military leaders who demanded that the mercenaries sign contracts with the Defense Ministry. They downed several military aircraft, killing more than a dozen Russian pilots.

Putin first denounced the rebellion as “treason” and a “stab in the back” and vowed to punish its perpetrators, but hours later made a deal that saw an end to the mutiny in exchange for an amnesty for Prigozhin and his mercenaries and permission for them to move to Belarus.

Details of the deal have remained murky, but Prigozhin has reportedly shuttled between Moscow, St. Petersburg, Belarus and Africa where his mercenaries have continued their activities despite the rebellion. He was quickly given back truckloads of cash, gold bars and other items that police seized on the day of the rebellion, feeding speculation that the Kremlin still needed Prigozhin despite the mutiny.

Earlier this week, the mercenary chief published his first video since the mutiny, declaring that he was speaking from an undisclosed location in Africa where Wagner is “making Russia even greater on all continents, and Africa even more free.”

Prigozhin’s overseas activities reportedly have irked Russia’s military leadership, who have sought to replace Wagner with Russian military personnel in Africa.

The Institute for the Study of War argued that Russian authorities likely moved to eliminate Prigozhin and his top associates as “the final step to eliminate Wagner as an independent organization.”

Flight tracking data reviewed by The Associated Press showed a private jet that Prigozhin had used previously took off from Moscow on Wednesday evening, and its transponder signal disappeared minutes later.

Videos shared by the pro-Wagner Telegram channel Grey Zone showed a plane dropping like a stone from a large cloud of smoke, twisting wildly as it fell, one of its wings missing. A freefall like that occurs when an aircraft sustains severe damage, and a frame-by-frame AP analysis of two videos was consistent with some sort of explosion mid-flight.

Prigozhin’s death is unlikely to have an effect on Russia’s war in Ukraine. His forces fought some of the fiercest battles over the last 18 months but pulled back from the frontline after capturing the eastern city of Bakhmut in late May.

As news of the crash was breaking, Putin projected calm, speaking at an event commemorating the WWII Battle of Kursk and hailing the heroes of Russia’s war in Ukraine. On Thursday, he addressed the BRICS summit in Johannesburg via videolink, talking about expanding cooperation between the group’s members. He didn’t mention the crash and the Kremlin made no comment about it.

0 notes

Text

Russia's air force commander dismissed

AP, Wednesday 23 Aug 2023

Gen. Sergei Surovikin, a former commander of Russia’s forces in Ukraine who was linked to the leader of an armed rebellion, has been dismissed from his job as chief of the air force, according to Russian state media.

FILE – In this handout photo released by Russian Defense Ministry Press Service on Saturday, June 24, 2023, the top Russian military commander in Ukraine,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

0 notes