#Fuji Single Grain Whiskey

Text

GSN Review: FUJI 30-Year-Old Single Grain Whiskey

GSN Review: FUJI 30-Year-Old Single Grain Whiskey

FUJI Whisky recently announced the U.S. release of its 30-Year-Old Single Grain Whiskey. Only 100 bottles of this elegant whiskey are available in the U.S in 2022.

A blend of multiple maturates of Canadian style grain whiskies, the FUJI 30-Year-Old Single Grain Whiskey includes distillates aged more than 30 years, including some aged up to 40 years. Distilled by the batch distillation method…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hayashi Yuu: 100 Questions (101 actually) Part One

Brief translation of most of the 100 questions Hayashi Yuu answered in his YT video. Split into 2 posts due to character limit.

Q1 - Q50

Top 3 movies?

Doesn't have an actual favourite, but he listed Shawshank Redemption, Léon, 100 Yen Love.

Does he read fan comments?

Yes, he reads them all and likes everyone's comments.

If he could be reborn, would he want to be male or female?

Male.

Most important item?

PC, because without it he can't practice his voice acting or conduct his YouTube activities.

Favourite character?

In high school, Ijuin from Tokimeki Memorial 2. He liked tsun characters.

A senpai he respects?

Namikawa Daisuke.

How does he deal with anger?

He just becomes too silent.

Which fast food joint's fries does he like most?

First Kitchen's plain fries doused with a lot of their spicy ketchup (ピリ辛ケチャップ).

Favourite western-style clothing brand?

SHAREEF (シャリーフ).

Opinion on women taller than him?

SO JEALOUS.

Which of his work does he want viewers to watch?

The Perks of Being a Wallflower (he voices Charlie Kelmeckis).

Hardest song he sang?

Ado's Odo.

Impressionable childhood memory?

When he was in kindergarten, he slipped and fell on the slide's side handles (the jutting part) left eye-first, and his left eye swelled up. (He elaborated on the memory in his first livestream)

Favourite hair colour?

His pink-beige hair in Distant Goal.

When did he start playing the piano?

18 y/o. He went to a music vocational school and didn't want to just sing but to also play an instrument so he chose to learn the piano.

One-phrase acapella please.

(demo in vid)

Highest and lowest he can go with his voice.

(demo in vid)

Career aspiration other than voice acting?

Primary/ grade school teacher as he's good at interacting/ playing with kids.

Type of woman he likes?

Short haircut, slim body.

What does he do when he feels down?

Sleep.

What does he want his fans to call him on YT?

Hayashuu (はやしゅー)

Most wanted item currently?

A portable camera to film videos for his YT channel, which he'd been considering getting.

High school club activities?

Though he joined the music/ band club (軽音楽部), he barely participated in it.

A happy moment since he became a seiyuu?

Tokyo Revengers got popular, and a lot of people he hadn't met in a long while got in contact with him again.

What quirk/ habit of women's does he like? (what gives the 'kyun' feeling)

When she adjusts her hair behind her ear as she's eating ramen/ soupy food.

What to keep in mind during recording sessions?

Trying to feel your chara's emotions is important, but pay attention to others' dialogue lines too.

Does he like Graniph clothing brand?

Yes. Cute sweatshirts and hoodies, plus he notices the cute outfits (worn by women) during filming.

What challenge does he want to try?

Collab with various singers.

What does he do for daily motivation?

(I didn't really follow but seems to be on the lines of just thinking a lot)

Udon or soba?

Soba.

Difference between acting techniques for anime vs foreign film dubbing?

For anime you have to imagine how to portray the character on your own, as for film dubbing there's already an existing screen actor so the consideration is to fill in as the actor's voice.

Favourite manga?

Recently, it's The Fable (by Minami Katsuhisa).

Any quirks/ habits?

While deeply concentrated in gaming, he'd stick his tongue out (as demonstrated in the YT video), and he's worried about unconsciously doing it when doing game activities for work.

Which seiyuu does he want to collab with the most?

Many, but if he were to pick one, Shirai Yuusuke because he seems to be the most involved with YT activities.

'Dark' personal history?

In high school, he was a gyaruo who'd try to hit on girls.

Liquor recommendation?

(Some kind of whiskey I didn't catch, not commonly stocked in shops; from his earliest livestream, I think it's Kirin Fuji Single Grain Whiskey)

Embarrassing experience?

In the 2nd year of middle school, while in the library he gotta rip a silent fart. You can guess what happened :)

What did he like to play during his school years?

A lot of Super Famicom games during primary school, stuff like Captain Tsubasa.

What pet would he keep?

He's not really into animals, but if he had to pick, cat.

Most laborious/ tiring moment?

He went on a 3-year hiatus from acting for club activities in middle school, but once again aspired to become a voice actor in high school. It was the most tiring period for him back then, having to juggle both school and work.

What makes him happiest?

The times when he's eating (rice/ meals).

The senpai he's on best terms with.

Katsu Anri, or at least he thinks so, and Taniyama Kishou whom he sometimes went to drink with.

Important points when dealing/ interacting with people?

Don't get carried away.

Where does he want to go for a vacation?

Barcelona, Spain.

Which seiyuu does he think has a great voice?

Tsuda Kenjirou.

Seasoning that he likes?

Tabasco.

Protein flavour that he likes?

Cookies and cream, strawberry.

Favourite outfit on women?

Pants style/ overalls.

What spicy food challenge does he want to try?

Okamoto Nobuhiko suggested that he try The Source Hot Sauce, but as it costs over 20,000yen he hasn't tried it yet, maybe one day.

For breakfast: rice gang or bread gang?

Rice gang. Natto, rice, and miso soup.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Made with peat from the Skagit Valley, Westland Distillery releases Solum 1 peated American Single Malt Whiskey.

Press Release

SEATTLE … Marking the official launch of the third and final expression in their Outpost Range, Westland Distillery has announced the release of Solum Edition 1 American Single Malt Whiskey (50%ABV, 700ml, $149.99 SRP). This limited annual bottling is the first nationally available single malt whiskey to showcase American peated malt, sourced from Washington’s Skagit Valley.

In its mission to showcase “a sense of place,” Westland Distillery’s Solum Edition 1 completes the Outpost Range story of oak (Garryana), barley (Colere) and peat (Solum) unique to its Pacific Northwest homeland. With its unique and location-specific botanical mix, this Pacific Northwest peat imparts a distinct flavor profile to the resulting whiskey.

“The peat of the Pacific Northwest has a completely different organic makeup than that of Scotland, resulting in a totally different flavor profile,” says Westland Co-Founder Matt Hofmann. “Botanicals like Labrador Tea, an aromatic shrub, bring unique qualities to our regional peat.”

Harvested from a bog approximately two hours south of Seattle, Westland departed from traditional methods of peat harvest, retrieving it from below the bog’s waterline rather than first draining and excavating the bog. This harvesting process was specifically designed to not disrupt the bog’s ecosystem, preventing the release of greenhouse gasses and ensuring that the bog will be able to continue producing peat into the future – a testament to Westland’s devotion to sustainability.

The act of harvesting and smoking its own barley also required collaboration with longtime partner Skagit Valley Malting, which developed the technology to achieve the desired results.

Solum Edition 1 Tasting Notes

(50%ABV, 700ml, $149.99 SRP; 4,044 bottles released globally)

NOSE: This peated whisky showcases bright notes such as fresh fuji apple, ground cinnamon, charred wood, and strawberry rhubarb crisp. There’s a savory smoke note that teases the nose.

PALATE: On the palate there are complex herbal tones such as burned sage, vanilla chamomile tea, and grain notes of coffee cake, pumpernickel toast.

GRAIN BILL: Skagit Valley Malting Peated Malt

CASK TYPES: Cooper’s Reserve New American Oak, Cooper’s Select New American Oak, First Fill ex-Bourbon

YEAST: Belgian Saison Brewer’s Yeast

FERMENTATION TIME: 96-144 Hours

The Outpost Range, which was first introduced in August 2020, features three limited-edition expressions that are released annually — Garryana, Colere, and Solum American Single Malt Whiskeys – each one emblematic of the Seattle distiller’s core mission to push beyond the old-world conventions of single malt. Garryana celebrated its seventh edition in February with 6,900 bottles, and the second edition of Colere was released in May 2022 with 3,000 prized bottles.

For information about Westland, please visit www.westlanddistillery.com. High-resolution images and limited-quantity samples are available upon request.

###

About Westland Distillery

Founded in 2010 and acquired by Remy-Cointreau in 2017, Seattle’s Westland Distillery brings a new and uniquely American voice to the world of single malt whiskey by exploring possibilities that have been ignored for generations. Along the way, Westland has been recognized as the country’s leading producer of American Single Malt Whiskey and founded the formal establishment of the emerging American Single Malt Whiskey category by starting the American Single Malt Whiskey Commission. While the distillery uses the same basic ingredients and processes used for centuries by traditional Old World single malt producers, it does not simply seek to replicate the results of its Scottish predecessors. Instead, Westland works to create whiskeys that reflect the distinct qualities of its time, place, and culture in the Pacific Northwest. All of Westland’s expressions are distilled at the Seattle distillery from 100% malted barley and fermented with a unique Belgian Saison brewer’s yeast before maturing in one of a variety of cask types, including new American oak, ex-Bourbon, ex-Sherry, and Garry Oak, to name a few.

from Northwest Beer Guide - News - The Northwest Beer Guide https://bit.ly/3J6lveg

0 notes

Text

LIST OF RARE & COLLECTABLE WHISKIES RELEASED FOR THE DISTILLERS’ CHARITY AUCTION ON 10th APRIL 2018

The full list of lots for the second Worshipful Company of Distillers’ Charity Auction will go live at www.distillers.auction on Tuesday 20th March 2018. It features more than 70rare and highly collectable whiskies and experiences that will go under the hammerat Mercers’ Hall, in the heart of the City of London, on Tuesday 10th April.

The evening, hosted by Master of the Worshipful Company of Distillers Bryan Burrough, will begin with a reception attended by the Lord Mayor of London, followed by international auctioneer David Elswood of Christie’s conducting the auction. Tickets to attend (dress code - black tie) are available for £100 at www.distillers.auction. There is also the opportunity on the auction website to register for absentee and telephone bidding.

Estimates for the lots, all of impeccable provenance having been donated directly by the producers or livery men of the Distillers, range from £250 to £25,000.They include some of the most sought-after whiskies in the world, one-of-a-kind expressions, special bottlings never released commercially and private invitations to tastings with the makers.

Bidding is expected to be strong for the Whyte & Mackay contribution of a one-off, specially produced bottle of The Dalmore 1976 Highland Single Malt Whisky 41 Years Old, matured in a Graham’s Port Colheita 1963 Pipe, with details andtasting notes on a scroll handwritten bymaster blender and liveryman Richard Paterson.

William Grant & Sons has provided exceptional whiskies with wonderful stories. Glenfiddich 50 Years Old, vintage distillery bottling from 1991, is number 440 of a limited edition of 500 bottles. This whisky was made from a batch of nine casks laid down in the 1930s, one for each of William Grant's nine children who had helped to build Glenfiddich Distillery in the 1880s.Its bottle of The Balvenie 50 Year Old Cask 191(bottle number 14 of 83), distilled in 1952 and bottled is 2002, is one of the oldest Balvenies ever released and the label reads: “The last cask of The Balvenie Single Malt Whisky from the nineteen fifties is unique and unrepeatable.”

Gordon & MacPhail has gathered six of its historic bottlings of Single Malt Scotch Whiskies, one distilled in each decade from the 1930s to 1980s, to create The Archive Collectionexclusively for The Distillers’ Charity Auction: Strathisla 1937, Linkwood 1946, Talisker 1955, Glen Grant 1965(never released for sale), Ardbeg 1974 and St. Magdalene 1982. This is accompanied by an invitation to the home of this family-owned company.

Compass Box Whisky has also delved into its archive to compileThe Hedonism Collection, from the originalin 2000 (the world’s first Blended Grain Scotch Whisky)to the latest expression released this year: Hedonism (First Edition), Hedonism Maximus, Hedonism 10th Anniversary, Hedonism Quindecimus and Hedonism The Muse. Founder John Glaser will host a special dinner in the Compass Box Blending Room for the winning bidder and five guests.

The Kirin Brewery Company Fuji-Gotemba Distillery has brought together a set of three 21 Year Old bottlings, never before sold together (two no longer available commercially and a Single Malt that has never been released for sale), from its historical whisky library stocks: Evermore 2001 Blended Whisky, Evermore 2002 Blended Whiskyand Fuji-Gotemba Single Malt Whisky distilled in 1981.

Chivas Bros has created The Royal Salute Highland Fling, a two-day trip to Speyside hosted by Peter Prentice, Keepers of the Quaich chairman and global VIP relations director for Chivas Bros. Staying at Linn House, six guests will visit Aberlour, The Glenlivet and Strathisla Distilleries with tastings in the Royal Salute Vault and Chivas Regal Cellar. The trip culminates in a Royal Salute Scottish Dinner and tasting of extraordinary whiskies.

Other highlights include: a magnum of Glenfarclas Highland Single Malt Whisky Aged 50 Years specially selected for The Worshipful Company of Distillers by John L S Grant and George S Grant and donated by Glenfarclas Distillery; Bowmore Single Malt Scotch Whisky 1964 Fino Cask 46 Years Old (one of 72 bottles) given by Beam Suntory UK; a unique bottle of Littlemill The Worshipful Company of Distillers 2018 Edition 40 Years Old selected by master blender Michael Henry; The MacallanSherry Oak 40 Years Oldrare single malt matured in three handpicked Oloroso sherry seasoned casks from Jerez; and number 232 of 500 crystal decanters of cask strength The North British Single Grain Scotch Whisky 50 Years Oldgiven to employees, former employees and friends ofThe North British Distillery Company Limited to celebrate its 125th Anniversary in 2010.

Alongside these legendary names are new distilleries already making their mark. Liverymen Daniel Szor, founder and CEO of The Cotswolds Distillery, is offering aday of whisky making and a hand-drawn cask strength bottle of Cotswolds Single Malt Whisky, and Stephen A Gould, proprietor and distiller at the Golden Moon Distillery, has donated a bottle from the first cask of its initial release of Colorado Single Malt Whiskey.

Bryan Burrough, Master of the Worshipful Company of Distillers, said: “As a Livery Company, charity is at the heart of what we do, and as Distillers we are proud to be leading our fundraising with the Distillers’ Charity Auction. An incredible collection of whiskies has been donated, which we are sure will generate a great deal of interest and excitement from collectors around the world.”

In the spirit of the event, the first two Worshipful Company of Distillers single cask bottlings of The Master’s Cask, signed by the Master of their year of bottling (an unpeated Caol Ila 18 Years Old for Douglas Morton in 2016 and Knockando 18 Years Old for Richard Watling in 2017), are presented for auction in a specially commissioned cabinet.

All proceeds will be donated to the Distillers’ Charity, which supports industry training and education, the Alcohol Education Trust dedicated to improving alcohol education for young people in Scotland, and the Lord Mayor’s Appeal towards the OnSide Youth Zones initiative creating opportunities for young people in London to thrive. More information on these charities can be found at www.distilers.auction.

Follow The Distillers’ Charity Auction on Instagram and Facebook @distillersauction.

The post LIST OF RARE & COLLECTABLE WHISKIES RELEASED FOR THE DISTILLERS’ CHARITY AUCTION ON 10th APRIL 2018 appeared first on GreatDrams.

from GreatDrams http://ift.tt/2GKW01t

CatherineDianneSoleta

1 note

·

View note

Text

Can We Ever Make It Suntory Time Again?

Aaron Gilbreath | Longreads | October 2019 | 23 minutes (5,939 words)

Bic Camera looked like many of the other loud, brightly colored electronics stores I’d seen in Japan, just bigger. Mostly, it was a respite from the cold. The appliances and electronics that jammed its interior gave no indication of its dizzyingly good liquor selection, nor did the many inexpensive aged Japanese whiskies hint that affordable bottles were about to become a thing of the past, or that I’d nurture a profound remorse once they did. When I found Bic Camera’s wholly unexpected liquor department, I lifted two bottles of high-end Japanese whisky from the shelf, wandered the aisles studying the labels, had a baffling interaction with a clerk, and put the bottles back on the shelf. All I had to do was pay for them. I didn’t.

Commercial Japanese whisky has been around since at least 1929, so during my first trip to Japan (and at home in the U.S.), there was no reason to think that all the aged Japanese whiskies that were readily available in the early 2000s would soon achieve holy grail status. In 2007, there were $100 bottles of Yamazaki 18-year sitting forlornly on a shelf at my local BevMo. One bottle now sells for more than $400 at online auctions; some online stores sell them for $700.

Yoichi 10, Yoichi 12, Hibiki 17 and 21, Taketsuru 12 and 17 — in 2014, rare and discontinued bottles lined store shelves, reasonably priced compared to their current $300 to $600 price tags. Those were great years. I call them BTB — before the boom. Before the boom, a bottle of Yamazaki 12 cost $60. After the boom, a Seattle liquor store priced their last bottle of Yamazaki 12 at $225. Before the boom, Taketsuru 12 cost $20 in Japan and $70 in the States. After the boom, online auctions sell bottles for more than $220.

Before the boom, Karuizawa casks sat, dusty and abandoned, in shuttered distilleries. After the boom, a bottle of Karuizawa 1964 sold for $118,420, the most expensive Japanese whisky ever sold at auction, until a Yamazaki 50 sold for $129,186 the following year, then another went for $343,000 15 months later.

Before the boom, whisky tasted of rich red fruits and cereal grains. After the boom, it tasted of regret.

I’ve spent the past five years wishing I could do things over. I remember my trips to Japan fondly — the new friends, the food and record stores, the Kyoto temples and solitary hikes — except for the whisky, whose absence coats my mouth with the proverbial bitter taste. I replay the time I walked into a grocery store in Tokyo’s Ikebukuro neighborhood and found a shelf lined with Taketsuru 12, four bottles wide and four deep, at $20 apiece; it starts at $170 now. I look at the photos I took of Hibiki 12 for $34, Yoichi 12 for $69, Taketsuru 21 for $89. I tell friends how I’d visited the Isetan Department Store’s liquor department in Shinjuku, where they had a 12-year-old sherried Karuizawa bottled exclusively for Isetan for barely more than $100, alongside a blend of Hanyu and Kawaski grain whisky that famed distiller Ichiro Akuto did exclusively for the store. Staff wouldn’t let me photograph or touch anything, but I could have afforded both bottles. They now sell for $1,140 and $1,290, respectively. I torture myself by revisiting my unfortunate logic, how I squandered my limited funds: buying inexpensive bottles to drink during the trip, instead of a few big-ticket purchases to take home.

Aaron, I’ve thought more times that I could count, you are such a fucking idiot.

To time travel, I look at photos of old Japanese whisky bottles in Facebook groups, like they are some sort of beverage porn, and wonder: Who am I? What have I become? There’s enough incredible scotch available here at home. Why do I — and the others whose interest spiked prices and made the bottles we loved inaccessible — care so much about Japanese whisky?

* * *

After the notorious Commodore Perry landed on Japanese shores in 1853 to open the closed country to trade, he gifted the emperor a barrel and 70 gallons of American whiskey, a spirit not well-known in Japan. As whiskey tends to do, it softened the nations’ encounter; one tipsy samurai felt so good he even hugged Perry. At the time, domestic spirit production was limited to shōchū and an Okinawan drink called awamori, made from sweet potatoes and rice respectively. Japanese companies tried to recreate the brown spirits that American and European companies had started importing, but without a recipe, the imitations were rough. The earliest Japanese attempts were either cheaply made locally or imported from Europe and labeled Japanese. When two boatloads of American soldiers stopped in the port of Hakodate in 1918, en route to fight Bolsheviks in Siberia, they found bars filled with knock-off scotch, including one called Queen George. As Major Samuel L. Johnson wrote in a letter, “If you come across any, don’t touch it. … It must be 86 percent corrosive sublimate proof, because 3,500 enlisted men were stinko fifteen minutes after they got ashore.”

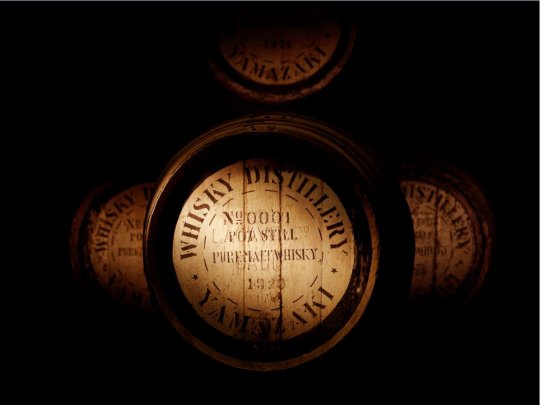

It was in this miasma of bad imitations that Suntory’s founder Shinjiro Torii recognized an opportunity. Winemaker Torii had been importing whiskies and bottling them as early as 1911. He called his brand Torys. As whisky found a toehold in Japan, he realized that slinging rotgut like the other frontier opportunists wasn’t the way to create a market; he needed to learn to distill an authentic, higher-quality whisky. The way Suntory’s marketing materials later presented it, Torii wanted to create a refined whisky that also reflected Japanese natural resources and Japanese tastes, which he perceived as more attuned to delicacy and nuance than the Scottish palate and that paired with Japanese cuisine rather than overpowering it — anything that tasted of corrosive sublimate would overwhelm your food. In 1923, he used his wine profits to build a distillery near Kyoto.

Elsewhere, in Osaka, Masataka Taketsuru, the son of a sake-maker, had been working for shōchū-maker Settsu Shuzo. The company, like Torii, wanted to make whisky, so in 1918 its president sent Taketsuru to study whisky-making in Scotland. Taketsuru was a 24-year-old chemist and took detailed notes when the Scottish distillers finally showed him their facilities and techniques. After two years learning the art of cask maturation, pot stills, and peat-smoking, Taketsuru returned to Japan to find that his employer’s enthusiasm for making real whisky had waned. So Taketsuru took his Scottish knowledge and enthusiasm to Torii, and the two men pooled their skills to build what became the Yamazaki Distillery, the country’s first commercial whisky producer. Sticking with Scottish tradition, they spelled it without the ‘e.’

It must be 86 percent corrosive sublimate proof, because 3,500 enlisted men were stinko fifteen minutes after they got ashore.

Suntory gets all the credit for distilling Japan’s first Scottish-style whisky, but Eigashima Shuzō, the company that now runs the White Oak Distillery, actually got the first license to produce whisky in Japan in 1919, five years before Yamazaki. Founder Kiichiro Iwai, who later founded the Mars Shinshu distillery and designed its equipment, had been Taketsuru’s mentor at Shuzo and is often called “the silent pioneer of Japanese whisky.” But Yamazaki started producing whisky sooner, so the rest, as they say, is history.

Suntory’s Yamazaki distillery launched Japan’s first true commercial whisky in 1929. Ninety years later, around a dozen companies distill whisky in Japan, depending on how you count them: Suntory and Nikka. Chichibu in Saitama Prefecture, White Oak in coastal Akashi. Kirin at the base of Mt. Fuji, Mars Shinshū in the village of Miyada in the Japanese Alps. Upstarts like Akkeshi in Hokkaido and the Shizuoka Distillery near Shizuoka. All produce stellar whisky.

Whisky experienced a huge boom in postwar Japan, coming to represent success, the West, masculinity, worldliness, and Japan’s increasing importance on the world stage. “If you were to choose a drink to symbolize the rapid economic growth in the four decades after the war,” Chris Bunting writes in Drinking Japan, “it would have to be whisky.” In journalist Lawrence Osborne’s words, whisky was “the salaryman’s drink, a symbol of Westernized manliness and sophistication.” Initially, distillers flooded the domestic marketplace with mediocre blended drams and single malts that appealed to hard-working businessmen. Then Suntory relaunched Torys to reach the working-class masses; the stuff was cheap and tasted it, with a cartoon businessman mascot that the target demographic could identify with. Nikka also began producing different lines to offer Japanese drinkers an affordable Western luxury product. During the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, there was Hi Nikka, Nikka Gold & Gold, Suntory Old Whisky, and Suntory Royal. Many of these these brands used the same affectations as Scottish and English products: crests, gold fonts, aged labels, faceted glass decanters with boldly shaped stoppers, the British spelling of flavour. The approach worked. Whisky went from a drink of the well-to-do businessman to a drink of the average citizen, and it became common for working-class Japanese men to keep bottles at home. Production boomed.

In the mid-1980s, consumer drinking habits shifted toward shōchū, whisky lost its allure, and some distillers from the postwar boom years closed. But Keizo Saji, the second son of Suntory founder Shinjiro Torii, saw an opportunity: premium whisky. In 1984, the year domestic whisky consumption dropped 15.6 percent, Saji launched Yamazaki 12, Japan’s first high-end mass-market single malt, transforming a downturn into a chance for the company to outdo itself with top-notch quaffs that would raise whisky’s domestic reputation and compete with scotches in the global marketplace. Nikka followed suit with their own single malt. Historians usually date the true start of Japanese whisky’s global ascendency to 2001, when 62 industry professionals did a blind taste test for British Whisky Magazine and named Nikka’s Yoichi 10 Single Cask the year’s best. “The whiskeys of Japan proved to be a real eye-opener for the majority of tasters,” the magazine wrote. As the Japan Times reported the following year, “Sales of Nikka’s award-winning 10-year-old single-cask whiskey, which has only been sold online at Nikka’s Web site, surged from about 20 bottles a month in 2000 to 1,200 in November after several Japanese newspapers carried an article about the taste-test events.”

For a long time, the majority of Japanese whisky was made following Scottish distilling methods: Japanese single malts were made from 100 percent malted barley (mostly imported from the U.K.) with local mountain and spring water, distilled in pot stills, and matured at least three years in oak. Japanese single malts moved to casks made from American or European oaks and that once held bourbon to age further and take on color and flavor, usually for 10 to 18 years. Like scotch, these single malts were rich, wooded, and highly aromatic. But Japanese innovation also created an astonishing diversity of flavors that tradition would never have allowed. Distillers age their whisky age in casks that once held sherry, bourbon, brandy, ume, and port, and, on a more limited basis, expensive casks made from Japan’s native mizunara oak. Every culture has masters and apprentices, but the Japanese have a particular respect for craftsmanship, and many people, from coffee roasters to cedarwood lunch box makers, dedicate their lives to a single specialty. Whisky writer Brian Ashcraft told Nippon that there’s a word for this: “In the Meiji period [1868–1912] there was a slogan, wakon-yōsai, or Japanese spirit and Western knowhow. So even if a product made in Japan is superficially the same as one made overseas, it’s going to be something Japanese because of differences in culture, language, food, climate. … This applies to anything from blue jeans to cameras, cars and trains. There are elements of the culture manifesting in the finished product.” Sakuma Tadashi, Nikka’s chief blender, told Ashcraft that by liberating themselves from tradition and embracing innovation and experimentation, the company can continue to improve its whisky. “At Nikka,” Tadashi said, “it’s ingrained into everyone that we need to make whisky that is better than scotch. That’s why if we change things, then we can make even more delicious whisky.”

* * *

Like whisky aging in barrels, Japanese whisky producers’ international reputation took years to develop, but gradually medals started weighing down their lapels. In 2001, the International Wine and Spirits Competition awarded Karuizawa Pure Malt 12 a gold medal. In 2003, the International Spirits Challenge gave Yamazaki 12 a gold award. Hibiki 30 won the International Spirits Challenge’s top prize in 2004, Yamazaki 18 won San Francisco World Spirits Competition’s Double Gold Medal in 2005, and Nikka’s Yoichi 20 was named World’s Best Single Malt Whisky in 2008. The World Whiskies Awards named Yamazaki 25 “World’s Best Single Malt” in 2012. Hibiki 21 was named the world’s best blended whisky in 2013. And on and on.

I’ve harbored an interest in Japanese culture and history since fifth grade. When I discovered the anime Robotech — one of the first Japanese animated shows adapted for mainstream American television — I sat for hours in my room, copying images of robots, missiles, and sparkly-eyed warrior women into my sketchbooks. As I moved away from anime and manga, I read more broadly about Japan and fell in love with Japanese literature, food, smart technology, and the Toyotas that never died, like the truck that took me from Arizona to British Columbia and back two times. Naturally, Bill Murray’s now-famous line in Lost in Translation “For relaxing times, make it Suntory time” made me want to taste what he was talking about. So I ordered a glass of 12-year Yamazaki at a bar.

Lively and bright with a medium body, the Yamazaki had layers of orange peel, honey, cinnamon, and brown sugar, along with a surprisingly earthy incense aroma, almost like cedar, which I later learned came from casks made from Japan’s mizunara oak — Mizunara imparts what distillers call “temple flavor.” I kept my nose in the glass, sniffing and smiling and sniffing, no matter what the other patrons thought of me. When Bill Murray raised his glass of Hibiki 17, Suntory’s Hibiki and Yamazaki lines were not widely distributed in the U.S. or Europe, and Western drinkers who knew them often considered them a novelty, or worse, a careful impersonation of the “real” Scottish malts. What I tasted could not be dismissed as a novelty. I knew that the people at Suntory who made this whisky had treated it as a work of art.

I loved it so much that I wondered what else was out there. There was little information in English: a single English-language book, Ulf Buxrud’s hard-to-find Japanese Whisky: Facts, Figures and Taste, which cost too much to order. Instead, I found a community of blogging gaijin who took Japanese spirits as seriously as the distillers did, sharing information, reviews, and whatever information they could find. Some of them lived in Japan. Others visited frequently and had Japanese connections who could translate details and source bottles. Clint A. of Whiskies R Us, Chris Bunting and Stefan Van Eycken at Nonjatta, Michio Hayashi at Japan Whisky Reviews. And Brian Love, aka Dramtastic, who ran the Japanese Whisky Review. They blogged about the domestic drams that you could only buy in Japan. They blogged about obscure drams from the decommissioned Kawasaki grain distillery; about something called owners casks and other limited bottlings made for Japanese department stores; and about what remained from the mothballed Karuizawa distillery, now one of the most fetishized whiskies in the world. They were my education.

At home, I searched for whiskies online and in bars and liquor stores and soon discovered my favorites: I preferred the smoky, rich coal-fired Yoichi to the woody, spicy Yamazaki. I liked the fruity depth of Hibiki a lot, but had an irrational prejudice against blended whisky, so I didn’t buy any bottles of Hibiki when they cost a mere $70. And I preferred the crisp, herbaceous forest flavors of 12-year-old Hakushu to them all; I still do. Even after I became moderately educated and increasingly opinionated, I kept buying $30 bottles of my beloved Elijah Craig 12-year instead of Yoichi or Hibiki. That’s the thing: The bloggers couldn’t teach me that the years when I discovered Japanese whisky turned out to be their best years, and that I needed to take advantage of my timing. They didn’t know. Nobody outside the whisky companies did, and nothing about their posts suggested that this world of abundant, affordable Japanese whiskies would come to an end around 2014.

The fan groups and bloggers praised Yamazaki and Karuizawa malts, driving worldwide interest and prices. By the time the influential Jim Murray’s Whisky Bible named the Yamazaki Single Malt Sherry Cask “World Whisky of the Year” in 2015 and San Francisco World Spirits Competition named Yamazaki 18 their 2015 Best in Class under the category “Other Whiskey,” U.S. and U.K. stores couldn’t keep Japanese whisky in stock. The student had overtaken the master. The $100 bottles of Yamazaki 18 no longer appeared on suburban BevMo shelves, and Hibiki 12 no longer cost $70. Everyone was asking stores for sherry cask, sherry cask, do you have the sherry cask? No, they did not. If you wanted a taste of Miyagikyo 12 in America, it would run you $30 to $50 a glass. The year 2015 was the first time Jim Murray named a Japanese malt the world’s best and the first time in the Whisky Bible’s 12-year history that no Scottish malt made the top five. Every drinker and their grandpa knew Johnnie Walker and Cutty Sark. Now they knew Suntory, too.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

In Japan, television fanned the flames further; a 2014 TV drama called Massan, based on the life of Nikka founder Masataka Taketsuru and his industrious Scottish wife Rita Cowan, helped the Japanese take renewed notice of their own products. Simultaneously, Suntory ran an aggressive ad domestic campaign to encourage younger Japanese to drink cheap highballs — whisky mixed with soda — fueling sales and depleting stock even more.

The buzz caught Suntory and Nikka off guard. After decades of patiently turning out top-notch single malts for a relatively indifferent domestic market, Nikka announced that their aged stock had run low, not just at retailers but inside their facilities. Unable to meet worldwide demand, they did what drinkers found unthinkable: They overhauled their lineup in 2015, replacing beloved aged whiskies with less expensive bottles of “no age statement” or “NAS” whiskies that blended young and old stock. Instead of Miyagikyo aged in barrels for 12 years, Nikka gave us plain Miyagikyo. Instead of Yoichi 10, 12, 15, and 20, there was straight-up Yoichi. Suntory had already added NAS versions of its age-statement Hibiki and Hakushu to conserve shrinking old stock and then went even further, banning company executives from drinking the older single malts to save product for customers. Yamazaki 12 still landed on American shelves, but in smaller quantities that sold out quickly, and Japanese buyers saw them less frequently back home.

Longtime fans greeted Suntory’s answer to the masses, called Toki, with skepticism and hostility. (In the words of one non-word-mincing Reddit poster: “Toki sucks. It’s fucking terrible.”) Time in wood gives whisky complexity. That’s how whisky works, but distillers didn’t have enough old whisky anymore, and they seemed to be rationing what remained in order to blend their core lines while they continued aging what they hoped to bottle again. They were victims of their own success, and they needed time to catch up. Nikka’s official press release put it this way: “With the current depletion, Yoichi and Miyagikyo malt whiskies, which are the base of most of our products, will be exhausted in the future and we will be unable to continue the business.”

On the open market, the news created a frenzy that fueled the resale business. Japanese citizens who previously bought few Nikka malts scavenged whatever bottles they could. Chinese investors flew to Japan to gather stock to mark up. Stores in Tokyo inflated prices to gouge tourists, selling $873 bottles of Hakushu 18 that retailed for $300 in Oregon. Secondhand liquor stores collected and resold unopened bottles, many of which came from the elderly or deceased, who had received them as omiyage gifts but didn’t drink whisky. Auction sites flourished. “We call this the ‘terminal aunt’ syndrome,” Van Eycken wrote, “you know, the aunt you never visit until she’s terminally ill.”

The boom times were over.

After the boom, foreign whisky fans took to the web to post about Japan’s shifting stock. Obsessive types like me — what the Japanese call ‘otaku — shared updates about which bottles they found where and which stores were picked clean. “The Japanese whiskys here are in short supply still, short of the cheap stuff,” said one visitor in Fukuoka. Another foreigner proclaimed “the glory days of $100 ‘zawa’s and easy to find single cask Hanyu’s are over.” Gaijin enthusiasts would search cities in their free time while in Japan on business; others drove out into inaka, the sticks, systematically searching for rare or underpriced bottles at mom-and-pop shops. “On the bright side,” the same commenter reported in 2016, “I went into the boonies and found a small liquor distributor who had 2 Yoichi 10’s and a bunch of dusties (Nikka Super 15, Suntory Royal 15, The Blend of Nikka 17 Maltbase, Once Upon a Time) all pretty cheap, between $18-$35 each. I know some of those dusties are not much more than mixer material, but it’s nice to have a piece of history.” Others found these searches pointless. “Well as a point of fact there is no point for any foreigner to come to Japan in search of Japanese whisky,” Dramtastic wrote in 2015. “You will in many countries almost certainly find a better offering at home and if not, one of the online retailers.” He titled his post “Buying Japanese Whisky In Japan — Nothing But Scorched Earth!”

It was right before the earth got scorched that I obliviously arrived in Japan.

* * *

When I finally got the money to travel overseas, there was only one real choice: Japan. For three weeks, I roamed Tokyo and Kyoto alone, where I shopped for my beloved canned sanma fish and green tea soy milk in grocery stores. I bought jazz CDs and Murakami books in Japanese I couldn’t read. I wrote about capsule hotels and old jazz bars. I photographed my ramen and eel dinners, and I photographed bottles of whisky on store shelves.

It wasn’t that I didn’t want them. I wanted them all: Yoichi 15, Hibiki 21, Miyagikyo 12. But as a traveler, practical considerations prevailed. I didn’t have much money. My luggage already held too much stuff, and anyway, the products would be there next time. I bought a few bottles of common whisky to drink during my trip and went about my business.

I unwittingly found the largest selection of Japanese whisky on my final night in Japan.

I was staying near the busy Ikebukuro train station and went out seeking curry. I wandered around in the cold, shivering and sad about leaving. As I passed ramen shops and busy izakayas, I spotted a cluttered electronics store. Music blared. The interior had a cramped, carnival atmosphere. Blinding white light spilled out the front door. Red lettering on the building’s reflective side said Bic Camera.

I didn’t know it then, but the Bic Camera chain had nearly 40 stores nationwide. The stores often stand seven or eight stories in busy areas near train stations where pedestrians abound. In 2008, the company was valued at $940 million, and its founder, Ryuji Arai, was the 31st richest person in Japan. When Arai opened his original Tokyo camera store in 1978, he sold $3.50 worth of merchandise the first day. Today, Bic Camera is an all-purpose mega-store that sells seemingly everything but cars and fresh produce.

Before the boom, Bic sold highly limited editions of whisky made exclusively for Bic, including an Ichiro 22-year and a Suntory blend. The stock is designed to compete with liquor stores that carry similar selections, though many Japanese shoppers come for the imported scotch and American bourbon. That night I couldn’t tell any of that. I couldn’t even tell if this was an upscale department store or a Japanese version of Walmart. In America, hip stories follow the “less is more” principle, with sparse displays that suggest they’re also selling negative space and apathy. Bic crammed everything in.

I rode the escalator up for no other reason than to see what was there. Cell phones, cameras, TVs — the escalator provided a nice view of each floor. When I spotted booze on 4F, I jumped off. They had an entire corner devoted to liquor and a wall displaying Japanese whisky. They had all the good ones I’d read about online but hadn’t been able to find and others I didn’t know. My luggage already contained so many CDs, clothes, and souvenirs that I’d have to mail some things home, but I grabbed two bottles anyway, I no longer remember which kind. I only remember gripping their cold glass necks like they were the last bottles on earth, desperate to bring just a bit more home, and I held them tightly as I wandered the aisles, studying the unreadable labels of aged whiskies and marveling at the business strategy of this mysterious store as I preemptively mourned my return to the States.

A clerk in a black vest approached me and said something politely that I couldn’t understand. With a smile, the man said something else and bowed, sorry, very sorry. He pointed to his watch. The store was closing, maybe it already had. He stood and stared. I looked at him and nodded. He stood nodding back. In that overwhelming corner, with indecipherable announcements blaring overhead, I considered my options and returned the bottles to the shelf, offering my apologies. Then I rode back down to the frigid street. The dark night felt darker away from Bic’s fluorescence, as did the winter air.

The high-end whiskies in a locked case. Tokyo grocery store 2014. Photo by Aaron Gilbreath

Like a good tourist — and like a dumbass — I photographed everything on that first trip, from tiny cars to bowls of udon to Japanese whisky displays. When I look at the photos of those rare bottles now, I see the last Tasmanian tiger slipping into the woods. The next season, it went extinct, and all I’d done was raise my camera at it. I had unwittingly visited the world’s greatest Japanese whisky city and I had nothing to show for it.

* * *

The trip ended. The regret lived on.

Partly, it was fed by money, or my lack thereof: Because I like having a few different styles of whisky at home, I wanted a range of Japanese styles, but I couldn’t afford $100 bottles of anything, which meant I’d never get to taste many of these whiskies.

Part of it was nostalgia: I wanted to keep the memory of my time in Japan alive, to prolong the trip, by keeping its bottles on display at home.

Mostly, it’s driven by something much more ethereal. When people ask why I like whisky, I tell them it’s the taste and smell. Scotch strikes a chord in me in a way that wine, bourbon, and cocktails do not. I spare them the more confusing truth, which even I struggle to articulate. Part of scotch’s appeal comes from scarcity and craftsmanship. Its spare ingredients include only barley, spring water, wood, and the chemical reactions that occur between them. And time: Aged spirits are old. For half of my 20s and all of my 30s — the time I was busting my ass after college, trying to build a career and learn to write well enough to tell a story like this — 18-year old Yamazaki whisky lay inside a barrel in a warehouse outside Osaka. That liquid and I lived our lives in parallel, steadily maturing, accruing character, until our paths finally crossed at a bar in Oregon.

That liquid and I lived our lives in parallel, steadily maturing, accruing character, until our paths finally crossed at a bar in Oregon.

But it’s more than age. Something magical happens in those barrels, where liquid interacts with wood in the dark, damp warehouses where barrels rest for decades. Aged whisky is a rare example of celebrating life moving at a slow, geological pace that is no longer the norm in our instant world. You can’t speed up this process, and that makes the liquid precious. When you’ve waited 12 years for a whisky to come out the cask, or 20 years — through wars and presidencies, political upheavals and ecological crises — that’s longer than many people have been alive. And in a sense, the whisky itself is alive. That potent life force is preserved in that bottle. The drops are by nature limited, measured in ounces and milliliters, and that limitation puts another value on it. When the cap comes off your 750-milliliter bottle, you count: sip, sip, uh oh, 600 mils left, then 400, then a level low enough that you reserve the bottle for special occasions.

The limited availability of certain whiskies adds another layer of scarcity value; when distilleries close, their whisky becomes irreplaceable. No more of those Hanyus or Karuizawas will ever get made. No more versions of the early 1990s Hibiki, since Suntory changed the formula. For distilleries that still operate, their whisky is irreplaceable, too. The exact combination of wood, temperature, and age will never produce the same flavor twice. Even when made according to a formula, whisky is a distinct expression of time and place. The weather, the blender, the barley, the proximity to the sea, and of course, the barrels — sherry, port, or bourbon? — all impart a particular flavor along with the way blenders mix them. For Yamazaki 18, 80 percent of the liquid gets aged in sherry casks, the remaining 20 percent in American oak and mizunara. That deliberation and precision come from human expertise that takes a lifetime to acquire, and expertise, like the whisky it produces, is singular and therefore valuable.

When you sip whisky, you don’t have to think about of any of this to enjoy it. You don’t even have to name the flavors you taste. You can just silently appreciate it; it doesn’t have to be any more complicated than that.

For me, Japanese whisky became more complicated, because I also wanted it to give me something more than it could: a connection to a trip and a time that had passed.

In Japan, everything looked a certain way. The way stores displayed bottles. The way restaurants displayed food. The way businesses signs hung outside — Matsuya, Shinanoya, CoCo Curry House — and the way all of those images and colors and geometries combined in a raucous clutter of wires and Hiragana and Katakana to create urban Japan’s distinctive look. When I returned home, I kept picturing those streets. They appeared in dreams and projected themselves on shower curtain as I washed in the morning. To stave off my hunger, I frequently ate at local Japanese restaurants, but even the most exacting decorations or grilled yakitori skewers couldn’t fully give me what I wanted. So I fantasized about creating it myself, and then I did: my best replica of an underground Tokyo bar, in the corner of my basement, the bottles lined up just so.

When my wife, Rebekah, and I took our honeymoon to Japan in 2016, I hoped to make up for past errors. Instead, I found the scorched earth. Japanese liquor stores and grocers sold few of the rare bottles they did just two years earlier. The fancy department stores had no Karuizawa or Hanyu. And the aged whiskies I did find had price tags too big to afford. I bought none of them on that trip either. For the cost of a $130 Yoichi 12, I could buy three great bottles of regular hooch at home. After we returned, I kept scheming ways to return to Japan for just a few days. Since I couldn’t, I satisfied myself with my display of empty whisky, sake, and Japanese beer bottles, and I kept scheming ways to get more domestic booze. A friend brought me a bottle of Kakubin while visiting her family in Tokyo. I asked a few friends in Japan to mail me bottles, even though regulations prohibit Japanese citizens from doing that. (They said no.)

There was only one way to get more whisky, and I couldn’t afford the ticket.

Then in January an email about a discount flight to Tokyo landed in my inbox. Flights were crazy cheap. I had to go.

When I proposed this to Rebekah, she said, “Seriously?” She lay in bed, staring at me like I’d asked if she’d hop on a plane to Amsterdam in 10 minutes without packing. “Just hear me out,” I said, and outlined my impractical business plan for recouping expenses by throwing paid, tip-only whisky parties for booze no one could find anywhere else in Portland, where we live. “Think about it as a stock mission,” I said. “I’m buying inventory.” She stared at me unblinking. It’s Japan, I said. It’s right there, next to Oregon after all that water. We were basically neighbors! The quality of the whisky I’d buy would be lower than all the now-collectible bottles I passed up on my first trip, but at least I would do it right.

It’s Japan, I said. It’s right there, next to Oregon after all that water.

I pictured myself flying to Tokyo in spring. The train from Narita Airport to Bic Camera in Kashiwa would wobble along the tracks, its brakes squeaking as it stopped at countless suburban platforms, with their walls of apartments and scent of fried panko. A 6 o’clock, the setting sun would cast the sides of buildings the color of summer peaches, and what little I could see of the sky would glow a blinding radish yellow. My knees would hurt from sitting on that plane for 11 hours, so I’d stand by the train door to stretch them the way I had during my first Tokyo trip, watching the 7-Eleven signs and giant bike racks pass, and posing triumphantly over time and my own pigheadedness. I’d buy as many bottles of domestic Japanese whisky as my one piece of rolling luggage would hold without exceeding the airline’s 50-pound limit. In a life marked by stupid things, this would be one of the stupidest. I’d feel endlessly grateful. The bottles would keep me connected me to Japan, to that trip, date-stamped by its ephemerality, just like the numbers on the bottles of aged whisky: 10, 12, 15, 20 years.

I never bought the plane ticket. There was little there to buy anyway. In 2018, Suntory announced that it would severely limit the availability of Hibiki 17 and Hakushu 12 in most markets. Soon after, Kirin announced it would discontinue its beloved, inexpensive, domestic Fuki-Gotemba 50 blend. Stock had simply run out. I’d bought a few good bottles for low prices before the boom and they stood in our basement bar, where we drank them, not hoarded them for future resale. Drinking is what whisky is for. The bottles stood as reminders that I had done a few things right. And maybe we should think less about what we missed and more about what is yet to come. In 2013 and 2014, Suntory expanded its distilling operations to increase production. It, Nikka, Kirin, and many smaller companies have laid down a lot of whisky, and when all that whisky has sufficiently aged there will be a lot of 10-to-15-year-old whiskies on the market — maybe as early as 2020 or 2021. “I always tell people not to worry about not being able to drink certain older whiskies that are no longer available,” Osaka bar owner Teruhiko Yamamoto told writer Brian Ashcraft. “Scotch whisky has a long tradition, but right now it feels like Japanese whisky is entering a brand new chapter. We’re seeing whisky history right before our eyes.”

Still, sometimes I can’t help myself. I’ll wonder if any Suntory shipments arrived at local stores here in Portland. They rarely do. Suntory doled out their remaining aged whiskies very carefully to try to satisfy their international markets. But when I checked Oregon State’s liquor search website recently, I found that a few stores had bottles of the very rare Yamazaki 18 for $300 apiece. Compared to auction sites, that was a deal. I still couldn’t afford that, but I was curious how many other interested, obsessive types were scrambling to secure bottles. When I called one store, a man answered the phone with, “Troutdale Liquor. We’re all sold out of the Yamazaki.”

“Ha,” I said. “Okay, thanks. I hope the calls end soon.”

He said, “Me too!”

I hung up the phone and got back to work.

* * *

Aaron Gilbreath has written for Harper’s, Kenyon Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Dublin Review and Brick. He’s the author of the books This Is: Essays on Jazz and Everything We Don’t Know: Essays. He’s working on books about California’s rural San Joaquin Valley and about Japan.

Editor: Michelle Weber

Fact checker: Sam Schuyler

Copy editor: Jacob Z. Gross

0 notes

Text

Whisky from the ‘Land of Rising Sun’.

“Whisky” the word itself is a ring to our ears, whether you drink whisky or not,; there is something about it that it makes everyone to at least have a taste of it and feel it. It makes to know more about it. Whisky is one of the most chosen liquor categories around the world. And no wonder, every year when many of the whisky brands come out for an auction, the collectors of whiskeys come out with high bids, and passion to claim the particular one to themselves. It’s a possession that no one wants to lose. Recently in the month of July and August of 2018 have seen some of the highest bid and auctions in the history of Whisky around the world.

It is all about the region that it comes from, from where it has been distilled, in which barrel it has been matured and finally with what ingredients it has been prepared? When we get a strong woody nose to the whisky, we usually think of it as coming from Kentucky or Tennessee. But when it’s taste refine, it is from Scotland and with Canada Whisky it is like to have something that is easy to take.

But let’s not forget about one more regional whisky, i.e. Japanese Whisky. Japan has always known for its liquor varieties, especially with the rice brew sake, wine and then there is traditional Shocho, awamori. But when it comes to Japanese Whisky, it is much more than just a category of the particular liquor type.

Japanese whisky is a style of whisky developed and produced in Japan. Whisky production in Japan began around 1870, but the first commercial production was in 1924 upon the opening of the country’s first distillery, Yamazaki. Broadly speaking the style of Japanese whisky is more similar to that of Scotch whisky than other major styles of whisky.

After Years, of innovation, tweaking, and perfecting, Japanese Whisky is said to be in a good place at the moment. Its distilleries have reached an accomplished status among and around all the world distilleries. Japanese whisky is making a play for dominance. Many of the Japanese Whisky is as good as the Scotch single malt especially as they also come in a low priced tag. But it is quite difficult to make anyone understand, what really is Japanese Whisky? As it doesn’t classification or regulation like scotch and bourbon do for that matter.

Japanese whisky is heavily influenced by Scotch, as the original distiller, Masataka Taketsuru, studied the craft in Scotland, and the malt for Japanese whiskies are often brought in from Scotland. It maintains similar traits, particularly the preference to blend varieties for singular tastes, though it’s often lighter, with subtler tones.

When you ask about Japanese whiskeys, two names come front which is, Suntory and Nikki. And this two brand is closely linked with two influential figures of Japanese Whisky who are, Shinjiro Torii and Masataka Taketsuru.

It was Shinjiro Torii, who first built the infamous Whisky distillery of Yamazaki, where he wanted to produce whiskies that is for the Japanese people. It was also him to hire Masataka Taketsuru, the original distiller of Japanese Whisky history. When they got separated, Torii’s Kotobukiya named as Suntory while Taketsuru started his own whisky brand named as Dainipponkaju, now known as Nikki. And since then it has been making a name for itself around the world, especially among the whisky drinkers.

Winning in the world whisky award in the category of best Japanese single malt by Hakushu 25 years old for another year again in 2018 has just proved that is it giving tough competition to the Scottish counterparts who are known for their distinctive taste and aroma. But not all of it, recently a rare bottle of 50 years old Yamazaki whisky has been sold out for ₹ 2 crores ( HK$2,695,000 / US$343,318) in an auction of Hong Kong, breaking the record of the most expensive bottle of Japanese whisky ever sold. Suntory’s Yamazaki distillery — Japan’s first and oldest — released the first edition Yamazaki in 2005 with just 50 bottles. The rare whisky was matured in casks made from mizunara (Japanese oak), giving it its deep amber colour. Nosing and tasting notes given by Suntory at the time of release for the “richly sweet and mature” expression included “a hint of the sweet-sour aroma of dried fruit set against a striking perfume that suggests the aromatic eaglewood tree”, “a full-bodied, yet mellow taste — smooth and strong, like silk” and “a lingering aftertaste, a slightly smoky fragrance, and mild woodiness”.

No, you don’t have to be scared to burn a hole in your pocket to possess one of these amazing Japanese Whisky, in order to enjoy drinking them. Here is a list of Japanese Whiskies that are quite affordable.

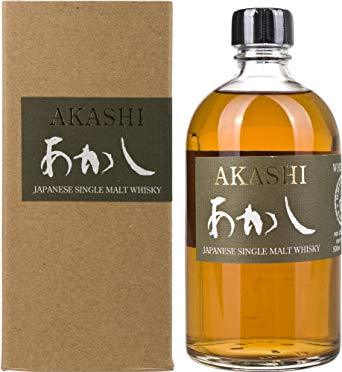

Akashi White Oak Single Malt

The White Oak Distillery’s non-age-statement single malts are young (usually between three and five years) and punchy. There is lots of oak, but this single malt does settle down with some time in the glass.

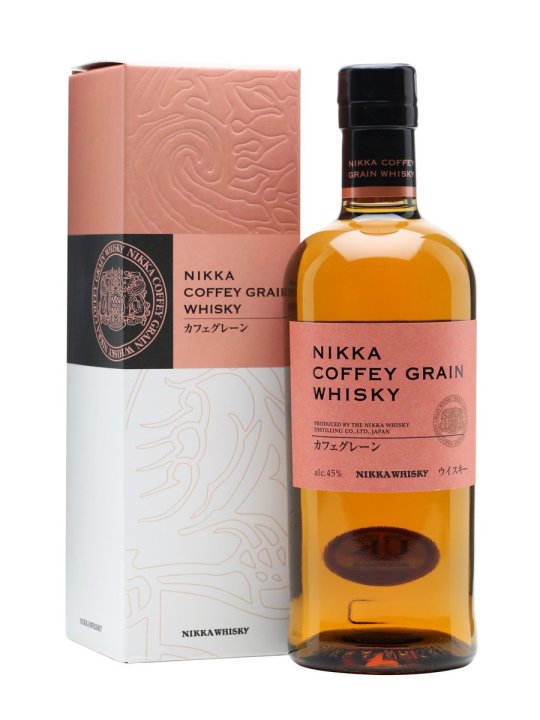

Nikka Coffey Grain Whisky

Not “coffee” as in the drink, but “Coffey” as in Aeneas Coffey, the inventor who created the traditional two-column Coffey still to produce spirit. Nikka is in possession of a Coffey still it imported from Scotland in the early 1960s and uses it to distill spirit with tremendous depth and flavor. There are two releases, Coffey Grain made from grain whisky, and Coffey malt made from malt spirit — something that isn’t traditionally done in Coffey stills. Both releases are excellent and affordable so you cannot go wrong with either.

Hibiki Japanese Harmony

The Hibiki blends are excellent representations of both the flavors and ideas conveyed in Japanese whisky. Good news, because Japanese Harmony, the entry-level release, is actually better than some of the Hibiki releases with age statements (though, it cannot top the incredible 17-year-old or the excellent 30-year-old). It’s a wonderfully soft whisky with honeyed wood aromas and silky, textured mouthfeel.

Ichiro’s Malt & Grain Blended Whisky

Ichiro is whisky maker Ichiro Akuto, and his Chichibu Distillery makes some of the most desirable whisky in the world. Limited bottlings can fetch high prices — that is, if you’re even able to buy them. Malt & Grain is the entry-level release. It’s a blend made from Chichibu’s malt spirit and imported grain spirit. Since the distillery doesn’t have massive continuous stills to produce grain spirit and since other large Japanese whisky makers who do keep all their grain spirit for in-house blends, it has no choice but to import. Malt & Grain is a fine introduction to Chichibu’s whiskies and shows off Ichiro’s blending talents.

Ichiro’s Malt Double Distilleries

Another excellent release from Ichiro Akuto, with malt spirit from his Chichibu Distillery as well as malt spirit from the Hanyu Distillery, which his family used to own. After the Hanyu Distillery was sold, the new owner wasn’t interested in whisky production, and Ichiro, who hadn’t yet found his footing with Chichibu, saved the casks of Hanyu whisky. This is both the past and the future of Japanese whisky. I’ve seen the smaller 200ml at local supermarkets here in Osaka, and a large department store recently got in a shipment of the bigger 700ml bottles.

Kirin Whisky Fuji Sanroku

Another Japanese supermarket whisky; another excellent, affordable buy. It’s bottled at 50 percent alcohol so most won’t have it neat. It opens up with some good water, but also makes a refreshing high-ball drink as the weather heats up. What makes Sanroku interesting among Japanese whiskeys is that aromas and flavors are like you’d find in bourbon. But unlike bourbon, this is made from melted Mount Fuji snow that takes over 50 years to filter through sediment left by volcanic eruptions to the water source Kirin uses for whisky.

Mars Whisky Twin Alps Blended Whisky

Mars Whisky says it is moving to single malt releases only, and this blend seems like a stop gap before more aged malt whisky hits shops. Still, Twin Alps is way better than it should be. It’s inexpensive in Japan (under $20), approachable and delicious, with oak aromas and soft fruit flavors and a hint of spice.

Nikka Whisky From The Barrel

This is very, very good. Sweet berry aromas, old books, and burnt wood. The delivery is crisp and clear. It’s bottled at a rather high percentage (51.4%), so you’ll probably want to bring it down with good water. It also means that you’re getting more bang for your buck, making this another excellent deal.

Taketsuru Pure Malt (No Age Statement)

While Nikka might be running short on whiskies with age statements, it’s making up for that with a strong line-up of affordable and terrific no-age-statement releases. Case in point: Taketsuru Pure Malt. Taketsuru is one of the founders of Japanese whisky, bringing back techniques from Scotland, helping to set up the Yamazaki Distillery, and then striking out on his own to found Nikka. Here is an exceedingly balanced blend of malt spirit from the Yoichi and Miyagikyo Distilleries with notes of bonfire smoke, berries, and spice.

The Yamazaki Single Malt 12 Years Old

First released in 1984, the Yamazaki 12-year is a classic Japanese single malt. While not the first Japanese single malt, it is one of the most iconic. It’s smooth with honeyed oak notes, wet grassy aromas and gentle smoke for a spicy finish.

Yoichi Single Malt (No Age Statement)

Year-by-year, this single malt release gets better and better. The Yoichi Distillery is the only place in the world that still fires its pot stills by coal. The temperature fluctuations give added personality to this robust spirit, which is then slowly aged in Yoichi’s warehouses. A dignified and refined Japanese whisky.

“If we don’t just give it a try, we will not know.” — rightly said by Suntory founder Shinjiro Torii.

#saycheers

#saycheers

#daru #daru App #delivery #drinkresponsibly #enjoyresponsibly

#NammaBengaluru#alcohol #alcholdelivery #liquordelivery #deliveryinbangalore #storenearme #liquorstorenearme #storenearme #winestore #Party #India #Bengaluru #Product #creativity #akashiwhiskysinglemalt #japan #japanesewhisky #Liquor #Winestore #singlemalt #nikkiwhisky #Yamazakiwhisky #hibikiwhisky #Akashiwhisky

Beer | Spirits | Wine | Delivered

Order online at www.daruapp.com or download DaruApp available on Google Play store and IOS app store, Available in Bangalore, India.

0 notes

Text

GSN Spirited News: November 2nd 2021 Edition

Templeton Distillery, part of the Infinium Spirits portfolio, is launching the third expression in its Cask Finish Series. The latest whiskey is Templeton Rye Oloroso Sherry Cask Finish, made from American straight rye whiskey aged a minimum of six years in charred oak barrels. It was then rested an additional nine months in Sherry casks sourced from the Marco de Jerez region of Spain that aged…

View On WordPress

#Alfred Giraud#Angel&039;s Envy#Bisquit & Dubouché#Bunnahabhain#Campari America#Cask Strength 12 Year Old#Distinguished Vineyards & Wine Partners#Founder’s Series cask strength rye#Fuji Single Grain Whiskey#High Rye Blended Scotch Whisky#Johnnie Walker#michter&039;s#Michter’s 20 Year Old Kentucky Straight Bourbon#Pernod Ricard#Procera#Templeton Distillery#Templeton Rye Oloroso Sherry Cask Finish#U.S. Angel’s Envy 2021 Cask Strength Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey Finished in Port Wine Barrels#Voyage

0 notes

Text

GSN Review: Fuji Single Grain Whisky & FUJI Whisky World Blend

GSN Review: Fuji Single Grain Whisky & FUJI Whisky World Blend

Distinguished Vineyards & Wine Partners (‘DVWP’) recently announced the U.S. debut of FUJI Whisky, the grain and blended whiskies from Japan. Launching in the U.S. for the first time in the brand’s history, FUJI Single Grain Whiskey, the brands flagship blend, and FUJI Whisky World Blend are now available at select establishments nationwide on and off premise.

Mt. Fuji Distillery was established…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Best Whiskeys In The World, According To The World Whiskies Awards 2020

#Whisky #KirinDistillery [Uproxx]This very rare bottle of Japanese whisky masters the single grain experience. Kirin’s Fuji Gotemba distillery is all about precision at every step. The distillery’s location at 2,000 feet above sea …

0 notes