#François-Timoléon De Choisy

Text

« François-Timoléon, l'abbé de Choisy, en femme. »

Musée des familles, 1855

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Folktales you can read as queer without squinting

Happy Pride everyone! Here is a selection of folk and fairy tales that I enjoy for both their plots and their queer vibes. I speak of vibes only, because I cannot say I have insight in the historical intention of these tales, but I do vouch for me presenting them to you unaltered, as I found them.

I will give the titles with links to the full texts here and summaries under the read more:

Gold-tree and Silver-tree

Scottish fairy tale, collected by Joseph Jacobs, published in 1892.

[Cw: abusive parent, murder.]

The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces

Cape Verdian folktale, collected by Elsie Clews Parsons in 1916-1917.

[Cw: attempted poisoning]

The Unicorn

Spanish fairy tale, collected by Aurelio Espinosa in 1947.

[Cw: murder, attempt at being outed, awkward use of pronouns.]

The Tale of Tamamizu

Japanese literary folktale, written by an unknown author between the Muromachi period (1336–1573) and the beginning of the Edo period (1603–1867).

[Cw: tragic ending.]

The Tale of the Marquise-Marquis of Banneville

French literary fairy tale, published in 1697, authorship contested (suggested: François-Timoléon de Choisy, Marie-Jeanne L'Héritier, Charles Perrault).

[Cw: gender dysphoria, age difference.]

Bisclavret

French literary legend, written by Marie de France in the 12th century.

[Cw: wolf-violence]

Gold-tree and Silver-tree

The beautiful princess Gold-tree is married off to a loving prince to protect her from her murderous mother Silver-tree. When her mother finds out where her daughter is she goes to visit her while the prince is out. To protect her, Gold-tree is locked in her room, but she is persuaded to stick her pink through the key hole so her mother can kiss it. Instead, the jealous queen stabs her with poison, killing Gold-tree. The prince is inconsolable and lays Gold-tree to rest in a locked room. In time he marries a second wife, who is of course curious to know what is in the room. She manages to get in and is so overcome with Gold-trees beauty that she immediately tries to wake her. She discovers a poisoned splinter, takes it out of her finger, and Gold-tree wakes up. When the prince returns home he is overjoyed and when the second wife offers to leave, he insists that she stays. The three of them live happily together until the evil queen finds out Gold-tree was revived. Once again she visits, but this time the second wife protects Gold-tree and tricks the queen into drinking her own poison. The queen dies and the three live a happy long life together, pleased and peaceful.

The Shoes That Were Danced to Pieces

A king offers his daughter’s hand in marriage plus half of his kingdom to whoever can find out why his daughter wears out seven pairs of shoes every night. A woman’s only son sets out to discover the secret, despite the threat of being executed if he fails. On his way he meets the Virgin Mary and God in disguise, who give him a coat of invisibility and a special whip. These gifts help him follow the princess as she sneaks out of the castle, passing by three bushes who greet her as she takes a flower from each. So does the boy. They arrive at a great hall where the princess dances with a company of strange old men, until all her shoes are worn. The boy collects the worn pairs of shoes, makes sure to get back to the castle before her and pretends to be asleep. The following morning he reveals the princess’ secret and gives the flowers and shoes as proof. The king asks him if he wants to marry the princess, but the boy declines, instead returning home to his mother with half a kingdom’s worth of fortune, and builds her a new house.

The Unicorn

A young woman’s sweetheart is killed by another man who is in love with her and after avenging his death, she flees her home. In this new life she lives as a man and choses the name Carlos. He goes into service for a wealthy family and the daughter of the house falls in love with him. They marry and while Carlos is sad to explain the situation to his wife, she loves him all the same and they live happily together. The lack of any children makes her father suspicious, however, and he starts putting Carlos to the test to see if he will act like a man or a woman, but he’s never able to discover anything. Eventually he takes Carlos hunting, suspecting that he will not want to bathe with the other men. Before the bathing, however, Carlos meets a unicorn who gives him a blessing and changes his body so he can go bathe without fear. The father is proven wrong and Carlos gets to return to his worried wife, to tell her what happened.

The Tale of Tamamizu

A kitsune falls in love at first sight with a nobleman’s daughter and wanders what he could possibly do to be near her. After considering taking on the appearance of a dashing young man to woo her, he decides he doesn’t want to put her in danger by marrying a fox, and turns into a girl instead. She goes to a devout couple who have only sons and introduces herself as an orphan. They immediately take her in and name her Tamamizu. Once she is settled, she confesses she would like to be a lady’s companion and her foster family get her employment with the young lady she is so in love with. Tamamizu is a great favourite, but so afraid of dogs that the young lady orders that dogs are no longer allowed near her. Three years pass when a contest is held to find the most beautiful autumn leaf. Tamamizu goes back to her fox siblings, who are overjoyed to see her and they help her find the leaf to give to her mistress. It is so magnificent even the Emperor hears of it and invites the lady to court. Tamamizu is to go with her, but she cannot bear it. Before they reach the court and she has to see her beloved become the Emperor’s wife, she disappears, leaving behind a letter for her mistress to explain everything. Everyone misses Tamamizu and the young lady sorrows for her painful heart.

The Tale of the Marquise-Marquis of Banneville

The Marquise of Banneville becomes a widow while she is pregnant and while she first wishes really hard for a son, she changes her mind and begs heaven to send her a daughter who will not have do die in war like her husband. The child is born and regardless of physicality, is raised as a girl. She grows up a beautiful, charming socialite and is a favourite of high society. The little marquise Marianne meets the handsome Marquis de Bercour and they begin a flirtatious, deeply romantic friendship that leaves her mother anxious to prevent them ever thinking of marrying. Eventually she even tells her daughter about the complication of her birth, but after some intense unhappiness the affection of the marquis and his declaration that he wants only to be her best friend, she puts it out of her mind. When her mother dies, however, the two lovers are so much together that they have to marry to escape the gossip. On the wedding night Marianne finds her husband inconsolable and he confesses that he was born a woman. She immediately tells him her own situation and they declare their love all over, decide to keep living exactly as they do now and have a child just as beautiful as they are.

Bisclavret

A kind and handsome nobleman, beloved by his king, is asked by his new wife why he disappears for three days every week. He confesses that this is when he “turns bisclavret” and must go out hunting in the shape of a wolf. His terrified wife convinces a knight who was already in love with her to steal her husband’s clothes so he cannot turn back. After her husband’s mysterious disappearance she quickly marries the knight. The distraught king comes across a wolf while hunting, however, that treats him so affectionately that he takes the animal home with him. The wolf never leaves his side and is incredibly docile, but when he attacks first the knight and then the knight’s wife, the king’s advisor starts to get suspicious. They are arrested and confess everything. The nobleman’s clothes are found and the king brings the clothes and the wolf to his royal bedchamber and leaves them. When he returns the nobleman is human again, fast asleep in the king’s bed. The overjoyed king wakes him with kisses, restores him to his title, and showers him with gifts.

Honorable mention for this mythic tale from the Bhuiya in India in which two women conceive a child together.

#laura retells#or close enough#queer representation#folklore#fairy tales#queer folklore#queer folktales

467 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more

1644 – The Abbé de Choisy, also known as François Timoléon (d.1724), born in Paris, among the notable Frenchmen of the seventeenth century, has left for posterity a vivid firsthand description of a strong cross-gender wish. During his infancy and early youth, his mother had attired him completely as a girl. At eighteen this practice continued and his waist was then "encircled with tight-fitting corsets which made his loins, hips, and bust more prominent." As an adult, for five months he played comedy as a girl and reported: "Everybody was deceived; I had [male] lovers to whom I granted small favors."

de Choisy as a woman

In 1676, he attended the Papal inaugural ball in a female attire. In 1687, he was received into the Académie de France. In 1696 he became the Ambassador of Louis XIV to Siam.

Regarding his gender identity he wrote,

I thought myself really and truly a woman. I have tried to find out how such a strange pleasure came to me, and I take it to be in this way. It is an attribute of God to be loved and adored, and man - so far as his weak nature will permit - has the same ambition, and it is beauty which creates love, and beauty is generally woman's portion … . I have heard someone near me whisper, "There is a pretty woman," I have felt a pleasure so great that it is beyond all comparison. Ambition, riches, even love cannot equal it …

In 1676, he attended the Papal inaugural ball in a female attire. In 1687, he was received into the Académie de France. In 1696 he became the Ambassador of Louis XIV to Siam.

Regarding his gender identity he wrote,

I thought myself really and truly a woman. I have tried to find out how such a strange pleasure came to me, and I take it to be in this way. It is an attribute of God to be loved and adored, and man - so far as his weak nature will permit - has the same ambition, and it is beauty which creates love, and beauty is generally woman's portion … . I have heard someone near me whisper, "There is a pretty woman," I have felt a pleasure so great that it is beyond all comparison. Ambition, riches, even love cannot equal it …

1667 – Louis de Bourbon, Légitimé de France, Count of Vermandois (d.1683) was the eldest surviving son of Louis XIV of France and his mistress Louise de La Vallière. He was sometimes known as Louis de Vermandois after his title. He died unmarried and without issue.

Louis de Bourbon was born at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. He was named after his father. Like his elder sister, Marie Anne de Bourbon, who was known at court as Mademoiselle de Blois, he was given the surname of de Bourbon not de France as a result of his illegitimacy. As a child, he called his mother Belle Maman because of her beauty. Louis was legitimised in 1669, at the age of two, and was given the title of comte de Vermandois and was made an Admiral of France.

In 1674, his mother entered a Carmelite convent in Paris, and took the name Sœur Louise de la Miséricorde. Afterwards, they saw very little of each other. From his mother and his father, Louis had five full siblings, many of whom died before his birth.

After his mother left, Louis lived at the Palais Royal in Paris with his uncle, Philippe of France, duc d'Orléans, and his wife Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate. At the Palais-Royal, he became very close to his aunt despite her well-known dislike of Louis XIV's bastards. The affection the aunt and nephew had for each other never diminished.

While he was at the court of his libertine and homosexual uncle, he met the Chevalier de Lorraine, his uncle's most famous lover. It is said that the young count was seduced by the older chevalier and his set (including the Prince of Conti) and began practicing le vice italien (the contemporary appellation for homosexuality).

Louis XIV decided to exile his son and the Chevalier de Lorraine.

In order to cover up the scandal, it was suggested that the boy be married off as soon as possible; a bride suggested was Anne Louise Bénédicte de Bourbon; Louis was exiled before anything could materialise.

In June 1682, Louis was exiled to Normandy. In order to smooth things over between father and son, his aunt Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate suggested to the king that Louis be sent as a soldier to Flanders, which was then under French occupation. The king agreed with the suggestion and his son was sent to the Siege of Courtray. It was there that Louis fell ill.

Despite his illness, Louis was desperate to regain his father's love and continued to fight in battle regardless of advice given by the royal doctor and the marquis de Montchevreuil that he return to Lille in order to recuperate.

Louis died on 18 November 1683, at the age of sixteen. He was buried at the cathedral at Arras. His loving sister and aunt were greatly impacted by his death. His father, however, did not even shed a tear. His mother, still obsessed with the sin of her previous affair with the king, said upon hearing of her son's death: I ought to weep for his birth far more than his death.

Louis was later suspected of being the Man in the Iron Mask.

Gandhi and Kallenbach

1869 – Mohandras Mahatma Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist, who employed nonviolent resistance (satyagraha) to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule, and in turn inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahatma ("great-souled", "venerable"), first applied to him in 1914 in South Africa, is now used throughout the world.

Born and raised in a Hindu family in coastal Gujarat, western India, Gandhi trained in law at the Inner Temple, London, and was called to the bar at age 22 in June 1891. After two uncertain years in India, where he was unable to start a successful law practice, he moved to South Africa in 1893 to represent an Indian merchant in a lawsuit. He went on to stay for 21 years.

It was in South Africa that Gandhi raised a family, and first employed nonviolent resistance in a campaign for civil rights. In 1915, aged 45, he returned to India. He set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban laborers to protest against excessive land-tax and discrimination. Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and above all for achieving Swaraj or self-rule.

Was Mahatma Gandhi gay? A Pulitzer-Prize winning author Joseph Lelyveld claims the god-like Indian figure not only left his wife for a man, but also harbored racist attitudes.

According to Lelyveld, his lover was Hermann Kallenbach, a German-Jewish architect and bodybuilder. The couple built their love nest during Gandhi's time in South Africa where he arrived as a 23-year-old law clerk in 1893 and lived for 21 years.

At the age of 13 Gandhi had been married to 14-year-old Kasturbai Makhanji, but after four children together they broke up so he could be with Kallenbach. As late as 1933 Gandhi wrote a letter telling of his unending desire and branding his ex-wife "the most venomous woman I have met." Kallenabach emigrated from East Prussia to South Africa where he first met Gandhi. The author describes Gandhi's relationship with the man as, "the most intimate, also ambiguous relationship of [Gandhi's] lifetime."

Much of the intimacy between the two is revealed in Kallenbach's letters to his Indian friend after Gandhi left his wifen 'Ba' — an arranged marriage — in 1908 for Kallenbach, a lifelong bachelor, according to the book.

The source of much of the detail of their affair was found in the "loving and charming love notes" that Gandhi wrote to Kallenbach, whose family saved them after the architect's death. They eventually landed in the National Archives of India. Gandhi had destroyed all those from Kallenbach.

It was known that Gandhi was preoccupied with physiology, and even though he had a "taut torso," weighing 106 to 118 pounds throughout his life, the author says Gandhi was attracted to Kallenbach's strongman build.

In letters, Gandhi wrote to Kallenbach, "How completely you have taken possession of my body. This is slavery with a vengeance."

"Your portrait (the only one) stands on my mantelpiece in the bedroom," he writes. "The mantelpiece is opposite the bed."

The pair lived together for two years in a house Kallenbach built in South Africa and pledged to give one another "more love, and yet more love."

Gandhi implored Kallenbach not to "look lustfully upon any woman" and cautioned, "I cannot imagine a thing as ugly as the intercourse of men and women."

By the time Gandhi left South Africa in 1914, Kallenbach was not allowed to accompany him because of World War I. But Gandhi told him, "You will always be you and you alone to me…I have told you you will have to desert me and not I you."

Kallenbach died in 1945 and Gandhi was assassinated in 1948

1985 - Rock Hudson, American actor died (b.1925); Hudson's death from HIV/AIDS changed the face of AIDS in the United States.

1997 – "Variety" objected to the Motion Picture Association of America's decision to give the movie "Bent" an NC-17 rating, pointing out that the sex scenes were far less graphic than heterosexual sex scenes in movies which receive R ratings.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The “great century” of French fairytales: A full chronology

As I announced, previously, La Bibliothèque des Génies et des Fées allowed me to gain access to an exact chronology of the first big “fairytale era” in French literature, its “great century” if you will - and I will put out the chronology below for all of you who are interested in it!

La Bibliothèque divides the “century of fairytales” into five different sections/periods/sub-genres.

First era is of course the “golden age of fairytales” proper, the “first wave of fairytales”, the beginning of it all - 1690-1709.

It was the time of Charles Perrault, and of Madame d’Aulnoy, still to this day the two most famous French authors of fairytales. It was when the genre of fairytales began - and when the very name “fairy tales” was coined. This was the start of what is known today as “le conte de fée mondain”, “le conte merveilleux galant”. This genre of fairytale was actually a form of entertainment that was created among upper-class circles - circles of cultured people, of literary enjoyers, the “salons” of the great ladies and courtiers of the time. It was a form of precious, polite, refined, courtly fairytale.

Beyond Perrault and d’Aulnoy, which I have spoken extensively of and will continue to do in the future, there were many other “first era storytellers”. A lot of them were women, since the fairytales were primarily a “female genre”: Mademoiselle Lhéritier, mademoiselle Bernard, mademoiselle de La Force, madame Durand, madame d’Auneuil, madame de Murat... But there were also a handful of male storytellers taking part of the fun too! Beyond Charles Perrault, there was the knight of Mailly (le chevalier de Mailly), Fénelon, Jean de Préchac, François-Timoléon de Choisy...

Interestingly, the last volume of the “Golden Age” part of La Bibliothèque actually contains both theatrical adaptations of the fairytales (which were a thing at the end of the 17th century! There’s three comedies based on fairytales in this book) as well as “critical texts” - because already back then the very genre of fairytales was discussed and explored.

The second era is “The Oriental Fairytale”, from 1704 to 1789.

This is the shift in the fairytale trend that was created by none other than Antoine Galland’s translation/rewrite of “The One Hundred and One Nights, Arabian tales”. This book launched a new wave of “oriental fairytales”, which of course latched onto the newborn “orientalism” movement.

There was a LOT of works in this era, though to quote just a few we have: “One Thousand and One Days, Persian tales.” by François Pétis de La Croix, who also wrote “Story of the sultana of Persia and of the vizirs”. There was Jean Bignon’s “Adventures of Abdalla”, Jacques Cazotte’s “Sequel to the One Thousand and One Nights”, as well as Thomas-Simon Gueullette’s various fairytales (Which range from Breton-originating tales to Peruvian tales, passing by another knock-off of Galland’s work “One Thousand and One Quarters of Hours”).

As you can see, unlike the first era of fairytales, which were mostly turned towards things inspired by European folklore and released in short formats, these “oriental fairytales” were all about “exotic” inspirations from Arabia to China, and about huge collections of tales (or titles promising a LOT of tales).

Third era overlaps with the second: it is the “second wave” of fairytales, or if you prefer the “return of fairytales”, from 1715 to 1775. In the first wave, storytellers were inventing never-seen before stories and creatng a genre ; in the second wave it was all about doing stories in the spirit of the first storytellers, exploring and growing the newborn genre.

The most famous fairytales out of these ones are without a doubt those of madame Leprince de Beaumont - who wrote “Beauty and the Beast” for her “Magasin des enfants” (Children’s Shop”), though there was an alternate version written shortly prior by mademoiselle de Villeneuve. Beyond these twos, this was also the era of other fairytale writers such as the Count of Caylus, madame Levesque, madame Le Marchand, madame de Lintot, mademoiselle de Lubert, Henri Pajon, Moncrif...

The difference between the 17th and 18th century fairytale is quite notable in its aim and goal. Because while the “first wave” fairytales were about making mostly a literary work, an entertainment, creating an aesthetic and something pleasant - this second wave of writers started to focus on making the fairytales useful. This is where we start seeing “pedagogic” fairytales, fairytales relying heavily in morals and teachings - and we are actually on the road to the “moral literature for children” that will appear in the 19th century, inspired by these fairy tales.

The fourth era could be considered a sub-category to the third, or rather a... counter-point. You see the “revival of fairytales” after the “Oriental hit” actually split into two. On one side you had people who wrote fairytales seriously, with moralist and pedagogic goals, trying to make these story into teaching-tools - the era described above. And then there were people who continued the fairytales - but with no actual serious object in mind. This was the time where the libertines took over the fairytales, from 1730 to 1754, and the fairytales they created were either parodies of fairytales, either “licentious” fairytales - and sometimes both, as humoristic erotic fairytales! It was the time of Antoine Hamilton, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Henri Pajon, Jacques Cazotte, Charles Duclos, Diderot, Crébillon, and many more... You have to understand that, by this time, we were in the full-on “Enlightenment” era, the “rule of reason and logic” over mankind. So a genre that was not logic or reasonable, a genre of wonders and supernatural and extravagance like fairytales had to be either “repurposed for the sake of reason and logic” (the third era of “pedagogic and moral fairytales” above), either mocked and denounced to better highlight the qualities of reason and logic. Which was the case here.

The fifth and last era would be the “end-of-century” fairytales, what La Bibliothèque calls “Féeries fin de siècle”. All the fairytales that were written around the publication of “Le Cabinet des Fées” - the last fairytales of the dying trend, worn-out fashion, weakening passion. The remnants of a genre that would disappear from the top of the charts, the literary discussions and the big events of the book-world up until the next turn of the century. These are the fairytales written between 1770 and 1796 : Beauharnais, Papelier, Willemain d’Abancourt, Mortemart, Regnier, Desjardins, Beckford, De Flahaut, Mérard de Saint-Juste and many more.The last of the “great storytellers” - the end of the “century of fairytales” in France.

#history of fairytales#french fairytales#chronology#fairytales chronology#catalogue of fairytales#fairytale authors#fairytale writers#literary fairytales#french culture

4 notes

·

View notes

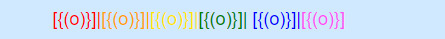

Photo

Weebly | DeviantArt | Pixiv | Blogger | Facebook | Patreon | Gumroad | Twitter | Instagram | Newgrounds

// Another Little Red Riding Hood Story // - François-Timoléon de Choisy

These two characters are actually the same guy, He(she) is from one of my doodle comic "Another Little Red Riding Hood Story", you can read it on my PIXIV→[LINK] but it hasn't translated to English.

In this comic, Choisy was a friend of Charles Perrault (The author of "Little Red Riding Hood"). Choisy tempted and toying with a girl "Marianne" because she offended and almost killed Perrault. Choisy and Marianne just like the "big bad wolf" and "little red riding hood", but in "Dangerous Liaisons" style (because I love this movie).

Choisy is very loosely based on the real historical person François-Timoléon de Choisy. In the comic, he and Perrault had a romantic relationship, but in reality, they just lived in the same era.

❤ Patreon Reward List and Progress

✨ Past Reward Shop

#my art#history character#crossdressing#little red riding hood#françois-timoléon de choisy#gothic#blond hair

21 notes

·

View notes

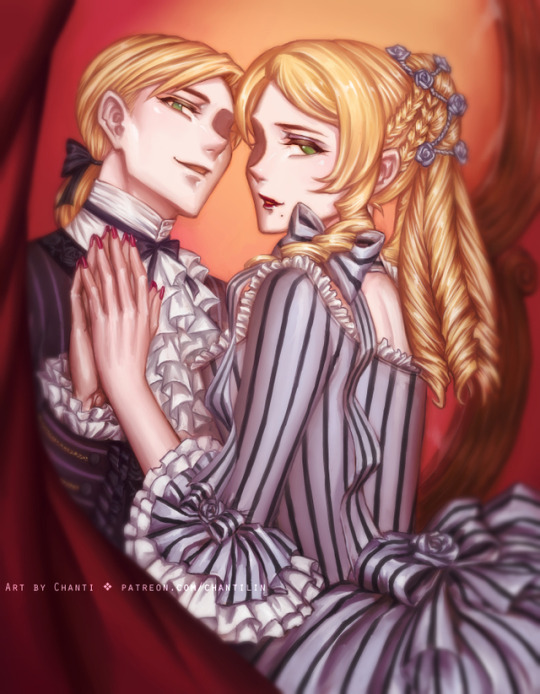

Photo

Weebly | DeviantArt | Pixiv | Blogger | Facebook | Patreon | Gumroad | Twitter | Instagram | Newgrounds

// Another Little Red Riding Hood Story // - François-Timoléon de Choisy

~ Drawlloween prompt "Werewolf" ~

He is the main character in my old doodle comic "Another Little Red Riding Hood Story"(un-translated).

The story was inspired by an actual historical person François-Timoléon de Choisy but very loosely.

🌟 SUPPORT ME TO GET FULL-RES VERSION

❤ Comic Archive

🍀 Patreon Reward List and Progress

🌼 Art Pack Shop

8 notes

·

View notes

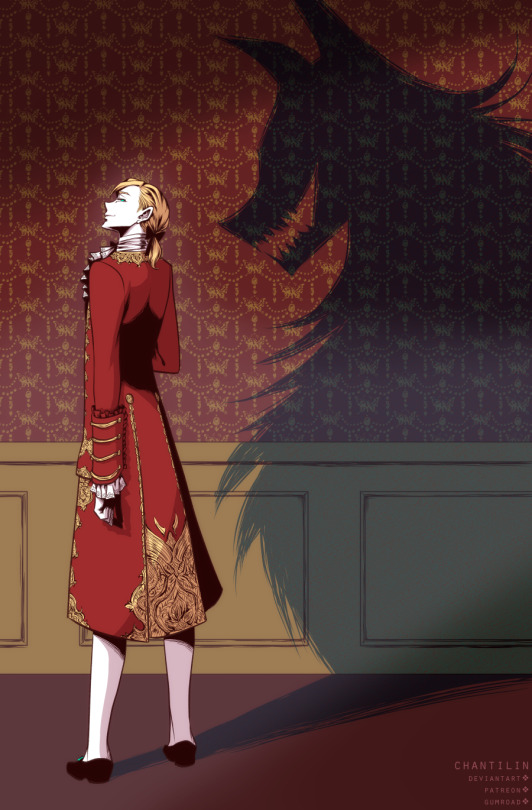

Photo

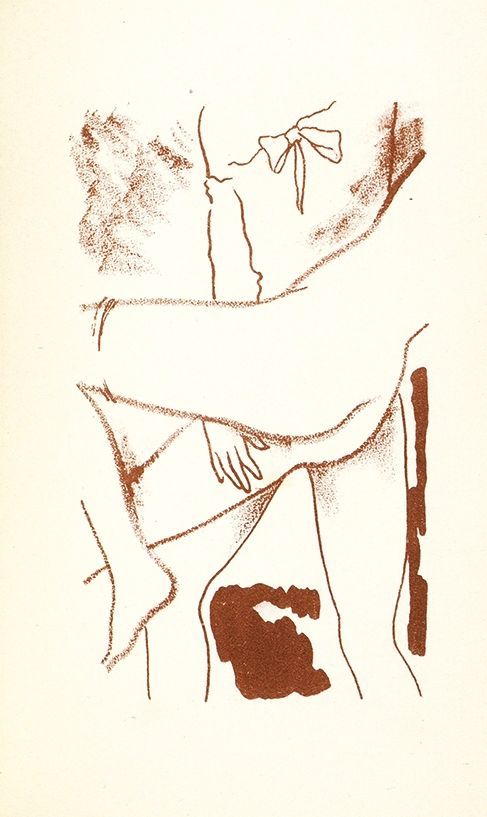

Yury (Georges) Annenkov (Russian/French, 1889–1974). Illustration to Histoire de Madame de Sancy by François-Timoléon de Choisy.

794 notes

·

View notes

Text

François-Timoléon de Choisy

One of my favourite people of Louis le Grand’s court is the Abbé de Choisy. A 17th century transvestite who lived an rather adventurous life. The abbé de Choisy as woman, image from the magazine “le Musée des familles” of 1855. Born in 1644 in Paris, he came from a not too wealthy family, which managed to enter the ranks of noblesse. Francois was the last born son of Jean III de Choisy,…

View On WordPress

#17th century transvestite#François-Timoléon de Choisy#abbé de Choisy#Madame de Sancy and Comtesse des Barres

0 notes

Text

Efemérides literarias: 2 de octubre

Efemérides literarias: 2 de octubre

Nacimientos

1616: Andreas Gryphius, poeta y dramaturgo alemán (f. 1664).1644: François-Timoléon de Choisy, escritor francés (f. 1724).1754: Louis de Bonald, político, filósofo, escritor y publicista francés (f. 1840).1808: Marcos Sastre, escritor, investigador y educador argentino de origen uruguayo (f. 1887).1877: Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi, escritor y crítico musical francés…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Eu sou Hedwig,

o CABEÇA-DE-ROUBADO da ex-alemanha oriental.

Eu sou Nano Florane,

o marinheiro passivo do navio pirata

(desnudo no significado de

frégate

ou como dizem os anglo-saxões

e suas diluições:

frigging).

Eu sou Jean Gejietti,

estudei as ruas e também os mares,

sei dos uniformes dos escravos

que manobravam remos no século XVII,

de sua lona cinza sobre os músculos,

suas correntes se chamavam “ramos”

e os punhos de renda, jabô e meias de seda

do capitão

Notre Homme.

Eu sou François-Timoléon de CHOISY, o abade.

Eu sou Madame Satã, Edwarda?

Ou serei Rrose Sélavy?

---

Bianca Lafroy

0 notes

Photo

Why October 2nd is BRILLIANT

All Dressed Up

Today is the birthday of François-Timoléon de Choisy who was born in Paris in 1644. He was a clergyman, an author and a transvestite. He tells us all about his adventures in a book called 'Mémoires de l’abbé de Choisy habillé en femme.'

Choisy's mother was on intimate terms with the French Royal family and he grew up at the court of King Louis XIV. He and the king's younger brother, Phillipe, used to very much enjoy dressing up as girls together. This was mostly at the behest of a cardinal called Mazarin. The previous king Louis XII had had terrible trouble with his own younger brother and the cardinal hoped that if the boy was feminized, he would never grow up with the desire to usurp the king. François, became his designated playmate. His mother dressed him in girl's clothes every time the young prince visited, which was about two or three times a week. She had his ears pierced, he wore diamonds and was generally dressed in what he later described as: “...all the little gewgaws to which one becomes easily used and which one parts with so hardly.” When the Prince arrived he would be dressed up likewise and the two would play together. They had a great time and the cardinal's plan worked out pretty well.

Mme de Choisy so much enjoyed seeing her son dressed so beautifully that she continued to dress him as a girl until he was eighteen. She rubbed his face with a special lotion that meant he grew no beard. He tells us that he rubbed his neck with calf water and sheep's foot pomade, which both sound horrible, to keep his skin soft. Also she banned the use of certain spices in the house. Nutmeg and cloves, it seems, are “drugs exciting to turbulence” and she certainly didn't want that.

Once he was eighteen, she needed to chose a career for him. The church seemed perfect. François became abbé of Saint-Seine in Burgundy in 1663. Although he visited there occasionally, he mostly remained in Paris, apart from the time he went to Bordeaux. There he spent five months working as an actress. He had many admirers to whom he enjoyed granting small favours but tells us he was: “much reserved about the great ones.” which earned him a reputation for modesty.

In 1666, his mother died, leaving him her jewellery. He wept for his mother but loved the jewels. In 1668 his old playmate, now Phillipe, Duke of Orleans, invited him to a ball. Phillipe was no longer really allowed to dress up but he asked his friend to come: “in a sweeping gown and unmasked.” François had a lovely time. He was much admired and danced beautifully “the ball was made for me” he said.

For the next fifteen years he seems to have dressed sometimes in women's clothes and sometimes in the clothes of an abbé. But, even then, he kept the earrings and beauty spots. He lived sometimes in the countryside and sometimes in Paris. In rural areas his choice of dress seems to have been quite readily accepted. Even though he never pretended to be anything other that a man who wore women's clothes, he took part in church services, gave concerts, took his neighbours to the opera and help distribute alms to the poor. He also had a sideline in educating young ladies about fashion. This was a situation he seems to have taken advantage of, as at least one of them became pregnant. In Paris though, he was ruined by gambling and horribly insulted on at least one occasion. Whilst attending the opera in his finery, he was told by a man called Montausier that he was a sad creature who ought to hide himself away. A horribly unkind thing to say, but it seems he was well known for it. Montausier was widely believed to be the inspiration behind the central character in Molière's play, 'The Misanthrope.'

In 1683 he became terribly ill and renounced his former ways and promised that, if he was spared, he would devote his life to God. He must have been pretty serious about it, because the following year he set off on a mission to convert the King of Siam to Christianity. The King wasn't really interested but François wrote a book about his travels and he was made a bishop. He also later wrote an eleven volume history of the French Church. In the latter part of his life he became a very holy man. He still always wore frocks when he was at home though.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Counterfeit Marquise

A literary fairy tale published in 1697, presumably by Charles Perrault and François-Timoléon De Choisy (who spent a considerable amount of his life in drag, just like the protagonists of this story).

Translated by Ranjit Bolt, featured in Warner’s Wonder tales: six stories of enchantment (1996).

Cw: gender disphoria.

The Marquis de Banneville had been married barely six months to a beautiful and highly intelligent young heiress when he was killed in battle at Saint-Denis. His widow was profoundly affected. They had still been very much in love and no domestic quarrels had disturbed their happiness. She did not allow herself an excess of grief. With none of the usual lamentations, she withdrew to one of her country houses to weep at her leisure, without constraint or ostentation. But no sooner had she arrived than it was pointed out to her, on the basis of irrefutable evidence, that she was carrying a child. At first she rejoiced at the prospect of seeing a little replica of the man she had loved so much. She was careful to preserve her husband’s precious remains, and took every possible step to keep his memory alive. Her pregnancy was very easy, but as her time drew near she was tormented by a host of anxieties. She pictured a soldier’s gruesome death in its full horror. She imagined the same fate for the child she was expecting and, unable to reconcile herself to such a distressing idea, prayed a thousand times to heaven to send her a daughter who, by virtue of her sex, would be spared so cruel a fate. She did more: she made up her mind that, if nature did not answer her wishes, she would correct her. She took all the necessary precautions and made the midwife promise to announce to the world the birth of a girl, even if it was a boy.

Thanks to these measures the business was effected smoothly. Money settles everything. The marquise was absolute mistress in her château and word soon spread that she had given birth to a girl, though the child was actually a boy. It was taken to the curé who, in good faith, christened it Marianne. The wet nurse was also won over. She brought little Marianne up and subsequently became her governess. She was taught everything a girl of noble birth should know: dancing; music; the harpsichord. She grasped everything with such precocity her mother had no choice but to have her taught languages, history, even modern philosophy. There was no danger of so many subjects becoming confused in a mind where everything was arranged with such remarkable orderliness. And what was extraordinary, not to say delightful, was that so fine a mind should be found in the body of an angel. At twelve her figure was already formed. True, she had been a little constricted from infancy with an iron corset, to widen her hips and lift her bosom. But this had been a complete success and (though I shall not describe her until her first journey to Paris) she was already a very beautiful girl. She lived in blissful ignorance, quite unaware that she was not a girl. She was known in the province as la belle Marianne. All the minor gentry roundabout came to pay court to her, believing she was a rich heiress. She listened to them all and answered their gallantries with great wit and frankness. My heart, she said to her mother one day, isn’t made for provincials. If I receive them kindly it’s because I want to please people.

Be careful, my child, said the marquise: you’re talking like a coquette.

Ah, maman, she answered, let them come. Let them love me as much as they like. Why should you worry as long as I don’t love them?

The marquise was delighted to hear this, and gave her complete licence with these young men who, in any case, never strayed beyond the bounds of decorum. She knew the truth and so feared no consequences. La belle Marianne would study till noon and spend the rest of the day at her toilette.

After devoting the whole morning to my mind, she would say gaily, It’s only right to give the afternoon to my eyes, my mouth, all this little body of mine.

Indeed, she did not begin dressing till four. Her suitors would usually have gathered by then, and would take pleasure in watching her toilette. Her chambermaids would do her hair, but she would always add some new embellishment herself. Her blonde hair tumbled over her shoulders in great curls. The fire in her eyes and the freshness of her complexion were quite dazzling, and all this beauty was animated and enhanced by the thousand charming remarks that poured continually from the prettiest mouth in the world. All the young men around her adored her, nor did she miss any opportunity to increase that adoration. She would herself, with exquisite grace, put pendants in her ears – either of pearls, rubies or diamonds – all of which suited her to perfection. She wore beauty spots, preferably so tiny that one could barely see them with the naked eye and, if her complexion had not been so delicate and fine, could not have seen them at all. When putting them on she made a great show of consulting now one suitor, now another, as to which would suit her best. Her mother was overjoyed and kept congratulating herself on her ingenuity. He is twelve years old, she would say to herself under her breath. Soon I should have had to think about sending him to the Military Academy, and in two years he would have followed his poor father. Whereupon, transported with affection, she would go and kiss her darling daughter, and would let her indulge in all the coquetries that she would have condemned in anyone else’s child.

This is how matters stood when the Marquise de Banneville was obliged to go to Paris to deal with a lawsuit that one of her neighbours had taken out against her. Naturally she took her daughter with her, and soon realised that a pretty young girl can be useful when it comes to making petitions. The first person she went to see was her old friend the Comtesse d’Alettef,11 to ask for her advice and her protection for her daughter. The comtesse was struck by Marianne’s beauty and so enjoyed kissing her that she did so several times. She took on herself the task of chaperoning her, and looked after her when her mother was busy with her suit, promising to keep her amused. Marianne could not have fallen into better hands. The comtesse was born to enjoy life. She had managed to separate herself from an inconvenient husband. Not that he lacked qualities (he loved pleasure as much as she did) but since they could not agree in their choice of pleasures, they had the good sense not to get in one another’s way and each followed their own inclinations. The comtesse, though not young any more, was beautiful. But the desire for lovers had given way to the desire for money, and gambling was now her chief passion. She took Marianne everywhere, and everywhere she was received with delight.

Meanwhile, the Marquise de Banneville slept easily. She was well aware of the comtesse’s somewhat dubious reputation, and would never have trusted her with a real daughter. But quite apart from the fact that Marianne had been brought up with a strong sense of virtue, the marquise wanted a little amusement and so left her to her own devices, merely telling her that she was entering a scene very different from that of the provinces; that she would encounter passionate, devoted lovers at every turn; that she must not believe them too readily; that if she felt herself giving way she was to come and tell her everything; and that in future she would look on her as a friend rather than a daughter, and give her such advice as she herself might take.

Marianne, whom people were starting to call the little marquise, promised her mother that she would disclose all her feelings to her and, relying on past experience, believed herself a match for the gallantry of the French court. This was a bold undertaking thirty years ago. Magnificent dresses were made for her; all the newest fashions tried on her. The comtesse, who presided over all this, saw to it that her hair was dressed by Mlle de Canillac. She had only some child’s earrings and a few jewels; her mother gave her all hers, which were of poor workmanship, and managed at relatively little expense to have two pairs of diamond pendants made for her ears, and five or six crisping pins for her hair. These were all the ornaments she needed. The comtesse would send her carriage for her immediately after dinner and take her to the theatre, the opera, or the gaming houses. She was universally admired. Wives and daughters never tired of caressing her, and the loveliest of them heard her beauty praised without a hint of jealousy. A certain hidden charm, which they felt but did not understand, attracted them to her and forced them to pay homage where homage was due. Everyone succumbed to her spell and her wit, which was even more irresistible than her beauty, won her more certain and lasting conquests. The first thing that captivated them was the dazzling whiteness of her complexion. The bloom in her cheeks, forever appearing and reappearing, never ceased to amaze them. Her eyes were blue and as lively as one could wish; they flashed from beneath two heavy lids that made their glances more tender and languishing. Her face was oval-shaped and her scarlet lips, which protruded slightly, would break – even when she spoke with the utmost seriousness – into a dozen delightful creases, and into a dozen even more delightful when she laughed. This exterior – so charming in itself – was enhanced by all that a good education can add to an excellent nature. There was a radiance, a modesty in the little marquise’s countenance that inspired respect. She had a sense of occasion: she always wore a cap when she went to church, never a beauty spot – avoiding the ostentation cultivated by most women. At Mass, she would say, One prays to God; at balls one dances; and one must do both with total commitment.

She had been leading a most agreeable life for three months when Carnival came round. All the princes and officers had returned from camp, and everywhere entertainments were being held again. Everyone was giving parties and there was a great ball at the Palais Royal. The comtesse, who was too old to show her face on such occasions, decided to go masked and took the little marquise with her. She was dressed as a shepherdess in an extremely simple but becoming costume. Her hair, which hung down to her waist, was tied up in great curls with pink ribbons – no pearls, no diamonds, only a beautiful cap. She had dressed herself, but even so all eyes were fixed on her. That night her beauty was triumphant.

The handsome Prince Sionad was there, dressed as a woman – a rival to the fair sex who, in the opinion of connoisseurs, took first prize for beauty. On arriving at the ball the comtesse decided to go and sit behind the lovely Sionad. Chère princesse, she said as she drew near and introduced the little marquise, here is a young shepherdess you should find worth looking at. Marianne approached respectfully and wanted to kiss the hem of the prince’s dress (or should I say the princess’s) but he lifted her up, embraced her tenderly and cried delightedly: What a lovely girl! What fine features! What a smile! What delicacy! And if I’m not mistaken, she is as clever as she is beautiful.

The little marquise had responded only with a bashful smile when a young prince came up and claimed her for a dance. At first all eyes were fixed on him, owing to his rank. But when people saw her answering his questions without awkwardness or embarrassment; saw what a feel she had for the music; how gracefully she moved; her little jumps in time; her smiles, subtle without being malicious and the fresh glow that vigorous exercise brought to her face, total silence, as at a concert, descended on the hall. The violinists found to their delight that they could hear themselves play, and everyone seemed intent on watching and wondering at her. The dance ended with applause, little of it for the prince, popular though he was.

The acclaim that the little marquise had received at the Palais Royal ball greatly increased the comtesse’s affection and concern for her. She could no longer do without her and she offered her rooms in her house, so that she could enjoy her company at her leisure. But on no account would her mother agree to this. The little marquise was almost fourteen and, if the secret of her birth was to be kept, it was vital that no one should be on intimate terms with her except her governess, who got her up and saw her into bed. She was still quite ignorant of her situation and, though she had many admirers, felt nothing for them. She cared for nothing and no one but herself and her appearance. People spoke to her of nothing else. She drank down this delicious praise in long draughts and thought herself the most beautiful person in the world; the more so since her mirror swore to her every day that the praise was justified.

One day she was at the theatre, in the first tier, when she noticed a beautiful young man in the next box. He wore a scarlet doublet embroidered with gold and silver, but what fascinated her were his dazzling diamond earrings and three or four beauty spots. She watched him intently and found his countenance so sweet and amiable that she could not contain herself, and said to the comtesse: Madame, look at that young man! Isn’t he handsome! Indeed, said the comtesse, but he is too conscious of his looks, and that is not becoming in a man. He might as well dress as a girl.

The performance went on and they said nothing more, but the little marquise often turned her head, no longer able to concentrate on the play, which was The Feign’d Alcibiades. Some days later she was at the theatre again in the third tier. The same young man, who drew such attention to himself with his extraordinary adornments, was in the second tier. He watched the little marquise at his leisure, as fascinated by her as she had been by him on the previous occasion, but less restrained. He kept turning his back on the actors, unable to take his eyes off her and she, for her part, responded in a manner less than consistent with the dictates of modesty. She felt in this exchange of looks something she had never experienced before: a certain joy at once subtle and profound, which passes from the eyes to the heart and constitutes the only real happiness in life. At last the play ended and, while they waited for the afterpiece, the beautiful young man left his box and went to ask the little marquise’s name. The porters, who saw her often, were happy to oblige him; they even told him where she lived. He now saw that she was of noble birth and decided, if possible, to make her acquaintance, even if he went no further. He resolved (love being ingenious) to enter her box by accident.

Ah, madame, he cried, I beg your pardon: I thought this was my box. The Marquise de Banneville loved intrigue and made the most of this one. Monsieur, she said to him with great frankness, we are indeed fortunate in your mistake: a man as handsome as you is welcome anywhere.

She hoped in this way to detain him so that she could look at him at her leisure; examine him and his adornments; please her daughter (whose feelings she had already detected) and, in a word, have some harmless amusement. He hesitated before deciding to remain in the box without taking a seat at the front. They asked him a hundred questions, to which he replied very wittily. His manner and tone of voice had an undeniable charm. The little marquise asked him why he wore pendants in his ears. He replied that he always had: his ears had been pierced when he was a child. As for the rest, they must excuse these little embellishments, normally only suitable for the fair sex, on the grounds of youth.

Everything suits you, monsieur, said the little marquise with a blush. You can wear beauty spots and bracelets as far as we’re concerned. You wouldn’t be the first. These days young men are always doing themselves up like girls. The conversation never flagged. When the afterpiece was over he conducted the ladies to their coach and had his follow it as far as the marquise’s house where, not daring to enter, he sent a page to present his compliments.

During the days that followed they saw him everywhere: in church; in the park; at the opera and the theatre. He was always unassuming, always respectful. He would bow low to the little marquise, not daring to approach or speak to her. He seemed to have but one object, and wasted no time in attaining it. Finally, after three weeks, the Marquise de Banneville’s brother (who was a state councillor) called and suggested that she receive a visitor – his good friend and neighbour, the Marquis de Bercour. He assured her that he was an excellent man and brought him round immediately after lunch. The marquis was the handsomest man in the world; his hair was black and arranged in thick, natural-looking curls. It was cut in line with the ears so that his diamond earrings could be seen. On this particular day he had attached to each of these a pearl. He also wore two or three beauty spots (no more) to emphasise his fine complexion.

Ah, brother, said the marquise, is this the Marquis de Bercour? Yes, madame, replied the marquis, and he cannot live any longer without seeing the loveliest girl in the world.

As he said this he turned towards the little marquise, who was beside herself with joy. They sat and talked, exchanging news, discussing amusements and new books. The little marquise was a versatile conversationalist, and they were soon at ease with one another. The old councillor was the first to leave, the marquis the last, having remained as long as he felt he could.

After this he never missed an opportunity of paying court to the girl he loved, and always made sure that everything was perfect. When the good weather came and they went out walking to Vincennes or in the Bois, they would find a magnificent collation, which seemed to have been brought there by magic, at a place specially chosen in the shade of some trees. One day there would be violins; the next oboes. The marquis had apparently given no instructions, yet it was obvious that he had arranged everything. Nevertheless, it took several days to guess who had given the little marquise a magnificent present. One morning a carrier brought a chest to her house which he said was from the Comtesse Alettef. She opened it eagerly and was delighted to find in it gloves, scents, pomades, perfumed oils, gold boxes, little toilet cases, more than a dozen snuff boxes in different styles, and countless other treasures. The little marquise wanted to thank the comtesse, who had no idea what she was talking about. She found out in the end, but reproached herself more than once for not having guessed at once.

These little attentions advanced the marquis’s cause considerably. The little marquise greatly appreciated them. Madame, she said to her mother with admirable honesty, I no longer know where I am. Once I wanted to be beautiful in everyone’s eyes; now the only person I want to find me beautiful is the marquis. I used to love balls, plays, receptions, places where there was a lot of noise. Now I’m tired of all that. My only pleasure in life is to be alone and think about the man I love. He’s coming soon, I whisper to myself. Perhaps he’ll tell me he loves me. Yes, madame, he hasn’t said that yet; hasn’t spoken those wonderful words: I love you, though his eyes and his actions have told me so a hundred times. Then, my child, replied the marquise, I’m very sorry for you. You were happy before you saw the marquis. You enjoyed everyone’s company; everyone loved you and you loved only yourself, your own person, your beauty. You were wholly consumed with the desire to please, and please you did. Why change such a delightful life? Take my advice, my dear child: let your sole concern be to profit from the advantages nature has given you. Be beautiful: you have experienced that joy; is there any other to touch it? To draw everyone’s gaze; to win all hearts; to delight people wherever one goes; to hear oneself praised continually, and not by flatterers; to be loved by all and love only oneself: that, my child, is the height of happiness, and you can enjoy it for a long time. You are a queen, don’t make yourself a slave: you must resist at the outset a passion that is carrying you away in spite of yourself. Now you command, but soon you will obey. Men are fickle: the marquis loves you today – tomorrow he will love someone else.

Stop loving me! said the little marquise. Love someone else! And she burst into tears.

Her mother, who loved her dearly, tried to console her and succeeded by telling her that the marquis was coming. There was a lot at stake and this incipient passion caused her considerable alarm. Where will it lead? she asked herself. To what bizarre conclusion. If the marquis declares himself – if he plucks up courage and asks for certain favours – she will refuse him nothing. But then, she reflected, the little marquise has been well trained; she is sensible; at most she will grant such trifling favours as will leave them in ignorance – an ignorance essential to their happiness.

They were talking like this when someone came to tell them that the marquis had sent them a dozen partridges, and that he was at the door, not daring to enter as he had just returned from hunting.

Send him in! cried the little marquise. We want to see him in his hunting clothes. He entered a moment later, all apologies for powder marks, sun burn and a dishevelled wig. No, no, said the little marquise. I assure you, we like you better dressed informally like this than in all your finery. If that is so, madame, he replied, next time you will see me dressed as a stoker.

He remained standing, as though about to leave. They made him sit and the marquise, kind soul, told them to sit together while she went to her study to write. The chambermaids knew what was what and withdrew to the dressing-room, leaving the lovers alone together. They were silent for a while. The little marquise, still flustered after her talk with her mother, scarcely dared raise her eyes, and the marquis, even more embarrassed, looked at her and sighed. There was something tender in this silence. The looks they exchanged, the sighs they could not contain, were for them a form of language – a language lovers often use – and their mutual embarrassment seemed to them a sign of love. The little marquise was the first to awake from this reverie.

You’re dreaming, marquis, she said. What of? Hunting? Ah, beautiful marquise, said the marquis, how lucky hunters are! They are not in love. What do you mean? she rejoined. Is being in love really so terrible? Madame, he replied, it is the greatest happiness in life. But unrequited love is the greatest misfortune. I am in love and it is not requited. I am in love with the most beautiful girl in the world. Venus herself would not dare put herself before her. I love her and she does not love me. She has no feelings. She sees me, she listens to me, and she remains cruelly silent. She even turns her eyes away from mine. How heartless! How can I doubt my fate? As he spoke these last words, the marquis knelt down before the little marquise and kissed her hands – nor did she object. Her eyes were lowered and let fall great tears.

Beautiful marquise, he said, you’re crying. You’re crying and I know the reason for your tears. My love is irksome to you. Ah, marquis, she answered with a heavy sigh, one can cry for joy as well as pain. I’ve never been so happy. She said no more and, stretching out her arms to her beloved marquis, granted him the favours she would have denied all the kings of the earth. Caresses were all the protestations of love they needed. The marquis found in the little marquise’s lips a compliance that her eyes had hidden from him, and this conversation would have lasted longer if the marquise had not emerged from her study. She found them laughing and crying at the same time, and wondered whether such tears had ever needed drying.

The marquis immediately rose to leave, but the marquise said to him pleasantly: Monsieur, won’t you stay and dine on the partridges you brought? He needed little persuading. What he desired more than anything else in the world was to be on familiar terms in this house. He stayed, even though he was dressed in hunting clothes, and had the exquisite pleasure of seeing the girl he loved eat. It is one of life’s chief delights. To watch at close quarters a pink mouth that, as it opens, reveals gums of coral and teeth of alabaster; that opens and closes with the rapidity that accompanies all the actions of youth; to see a beautiful face animated by an often repeated pleasure, and to be experiencing the same pleasure at the same time – this is a privilege love grants to few.

After that happy day the marquis made sure he dined there every night. It was a regular affair and the little marquise’s suitors, who had had no cause to be jealous of one another, took it as settled. She had made her choice and they all admitted that beauty and vanity, however powerful, are no defence against love. The Comte d’****, one of her most ardent admirers, had a keen sense that his passion was being made light of. He was handsome, well built, brave, a soldier: he could not allow the little marquise to give herself to the Marquis de Bercour, whom he considered vastly inferior in every respect to himself. He decided to pick a quarrel with him and so disgrace him, thinking him too effeminate to dare cross swords with him. However, to his great surprise, at the first word he uttered when they met at the Porte des Tuileries, the marquis drew his sword and thrust at him with gusto. After a hard-fought duel they were parted by mutual friends.

This adventure pleased the little marquise. It gave her lover a war-like air, though she trembled for him nevertheless. She saw clearly that her beauty and her preference for him would constantly be exposing him to such encounters, and she said to him one day: Marquis, we must put an end to jealousy once and for all; we must silence gossip. We love one another and always will. We must bind ourselves to one another with ties that only death can break.

Ah, beautiful marquise, he said, what are you thinking of? Does our happiness bore you? Marriage, as a rule, puts an end to pleasure. Let us remain as we are. For my part, I am content with your favours and will never ask you for anything more. But I am not content, said the little marquise. I can see clearly that there is something missing in our happiness, and perhaps we will find it when you belong to me entirely, and I to you. It would not be right, replied the marquis, for you to throw in your lot with a younger son who has spent the bulk of his fortune and whom you still know only by appearances, which are often deceptive.

But that’s just what I love about it, she interrupted. I’m so happy that I have enough money for us both, and to have the chance of showing you that I love you and you alone.

They had reached this point when the Marquise de Banneville interrupted them. She had been closeted with her agents, and thought she would refresh herself with some lively young company, but she found them in a deeply serious mood. The marquis had been greatly put out by the little marquise’s proposal. Ostensibly it was very much to his advantage, but he had secret objections to it, which he considered insurmountable. The little marquise, for her part, was a little annoyed at having taken such a bold step in vain, but she soon recovered, deciding that the marquis had refused out of respect for her – or that he wished to prove the depth of his feelings for her. This thought made her decide to speak to her mother about it, and she did so the following day.

No one was ever more astonished than the Marquise de Banneville when her daughter spoke to her of marriage. She was sixteen and no longer a child. Her eyes had not been opened to her situation, and her mother hoped they never would be. She was careful not to agree to the match, but to reveal the truth would have been a painful solution both for her daughter and the marquis. She resolved to do so only as a last resort. Meanwhile she would prevent, or at least postpone, the marriage. The marquis was in agreement with her on this, but the little marquise – passionate creature that she was – begged, entreated, wept, used every means to persuade her mother. She never doubted her lover, since he did not dare oppose her with the same firmness. Finally she pushed her mother to the point where she said these words to her: My dear child, you leave me no choice: against my better judgement I must reveal to you something that I would have given my life to conceal from you. I loved your poor father and when I lost him so tragically, in dread of your meeting the same fate, I prayed with all my heart for a daughter. I was not so fortunate: I gave birth to a son and I have brought him up as a daughter. His sweetness, his inclinations, his beauty, all assisted my plan. I have a son and the whole world believes I have a daughter. Ah, madame! cried the little marquise, is it possible that I …? Yes, my child, said her mother embracing her, you are a boy. I can see how painful this news must be for you. Habit has given you a different nature. You are used to a life very different from the one you might have led. I wanted you to be happy and would never have revealed the sad truth to you if your obstinacy over the marquis had not forced me to. You see now what you were about to do? How, but for me, you would have exposed yourself to public ridicule?

The little marquise did not answer. Instead she merely wept and in vain her mother said to her: But my child, go on living as you were. Be the beautiful little marquise still – loved, adored by all who see her. Love your beautiful marquis if you like, but do not think of marrying him. Alas! cried the little marquise through her tears, he has asked for nothing more. He flies into a rage when I mention marriage. Ah! Could it be that he knows my secret? If I thought that, dear mother, I would go and hide myself in the furthest corner of the earth. Could he know it? In floods of tears now, she added: Alas, poor little marquise, what will you do? Will you dare show your face again and act the beauty? But what have you said? What have you done? What name can one give the favours you have granted the marquis? Blush! Blush, unhappy girl! Ah, nature you are blind: why did you not warn me of my duty? Alas! I acted in good faith, but now I see the truth and I must behave quite differently in future. I must not think about the man I love – I must do what is right.

She was uttering these words with determination when it was announced that the marquis was at the door of the antechamber. He entered with a happy air and was amazed to see both mother and daughter with lowered eyes and in tears. The mother did not wait for him to speak but rose and went to her room. He took courage and said: What’s the matter, beautiful marquise? If something is distressing you, won’t you share it with your friends? What? You won’t even look at me! Am I the cause of this weeping? Am I to blame without knowing it?

The little marquise dissolved in tears. No! No! she cried. No! That could never be, and if it were so I would not feel as I do. Nature is wise and there is a reason for everything she does.

The marquis had no idea what all this meant. He was asking for an explanation when the marquise, who had recovered a little, left her room and came to her daughter’s aid. Look at her, she said to the marquis. As you see, she is quite beside herself. I am to blame. I tried to stop her but she would have her fortune told, and they said she would never marry the man she loved. That has upset her, Monsieur le Marquis, and you know why.

For my part, madame, he replied, I am not at all upset. Let her remain always as she is. I ask only to see her. I shall be more than happy if she will consider me her best friend.

With this the conversation ended. Emotions had been stirred, and would take time to settle. But they settled so completely that after eight days there was no sign of any upheaval. The marquis’s presence, his charm, his caresses, obliterated from the little marquise’s mind everything her mother had told her. She no longer believed any of it, or rather did not wish to believe. Pleasure triumphed over reflection. She lived as she had done before with her lover and felt her passion increase with such violence that thoughts of a lasting union returned to torment her. Yes, she said to herself, he cannot go back on his word now. He will never desert me. She had resolved to speak of it again, when her mother fell ill. Her illness was so grave that after three days all hope of a cure was abandoned. She made her will and sent for her brother, the councillor, whom she appointed the little marquise’s guardian. He was her uncle and her heir, since all the property came from the mother. She confided to him the truth about her daughter’s birth, begging him to take it seriously and to let her lead a life of innocent pleasure that would harm no one and which, since it precluded her marrying, would guarantee his children a rich inheritance.

The good councillor was delighted at this news and saw his sister die without shedding a tear. The income of thirty thousand francs that she left the little marquise seemed certain to pass to his children, and he had only to encourage his niece’s infatuation for the marquis. He did so with great success, telling her that he would be like a father to her and had no wish to be her guardian except in name.

This sympathetic behaviour consoled the little marquise somewhat – and she was certainly distraught – but the sight of her beloved marquis consoled her even more. She saw that she was absolute mistress of her fate, and her sole aim was to share it with the man she loved. Six months of official mourning passed, after which pleasures of all kinds once again filled her life. She went often to balls, the theatre, the opera, and always in the same company. The marquis never left her side and all her other suitors, seeing that it was a settled affair, had withdrawn. They lived happily and would perhaps have thought of nothing else, if malicious tongues could have left them in peace. Everywhere, people were saying that, while the little marquise was beautiful, since her mother’s death she had lost all sense of decorum: she was seen everywhere with the marquis; he was practically living in her house; he dined there every day and never left before midnight. Her best friends found grounds for censure in this: they sent her anonymous letters and warned her uncle, who spoke to her about it. Finally, things went so far that the little marquise went back to her first idea and decided to marry the marquis. She put this to him forcefully; he resisted likewise, only agreeing on condition that the marriage would be a purely public affair, and that they would live together like brother and sister. This, he said, was how they must always love one another. The little marquise readily agreed. She often remembered what her mother had told her. She spoke of it to her uncle, who began by outlining all the pitfalls of marriage and ended by giving his consent. He saw that, by this means, the income of thirty thousand francs was sure to pass to his family. There was no danger of his niece having children by the Marquis de Bercour whereas, if she did not marry him, her notion that she was a girl might change with time and with her beauty, which was sure to fade. So a wedding day was fixed on, bridal clothes made and the ceremony held at the good uncle’s house. (As guardian he undertook to give the wedding feast.)

The little marquise had never looked as beautiful as she did that day. She wore a dress of black velours completely covered in gems, pink ribbons in her hair and diamond pendants in her ears. The Comtesse d’Alettef, who would always love her, went with her to the church, where the marquis was waiting. He wore a black velours cloak decked with gold braid, his hair was in curls, his face powdered, there were diamond pendants in his ears and beauty spots on his face. In short, he was adorned in such a way that his best friends could not excuse such vanity. The couple were united for ever and everyone showered them with blessings. The banquet was magnificent, the king’s music and the violons were there. At last the hour came and relatives and friends put the couple together in a nuptial bed and embraced them, the men laughing, a few good old aunts weeping.

It was then that the little marquise was astonished to find how cold and insensitive her lover was. He stayed at one end of the bed, sighing and weeping. She approached him tentatively. He did not seem to notice her. Finally, no longer able to endure so painful a state of affairs, she said: What have I done to you, marquis? Don’t you love me any more? Answer me or I shall die, and it will be your fault.

Alas, madame, said the marquis, didn’t I tell you? We were living together happily – you loved me – and now you will hate me. I have deceived you. Come here and see.

So saying he took her hand and placed it on the most beautiful bosom in the world. You see, he said, dissolving in tears, you see I am useless to you: I am a woman like you.

Who could describe here the little marquise’s surprise and delight? At this moment she had no doubt that she was a boy and, throwing herself into the arms of her beloved marquis, she gave him the same surprise, the same delight. They soon made their peace, wondered at their fate – a fate that had brought matters on to such a happy conclusion – and exchanged a thousand vows of undying love.

As for me, said the little marquise, I am too used to being a girl, and I want to remain one all my life. How could I bring myself to wear a man’s hat?

And I, said the marquis, have used a sword more than once without disgracing myself. I’ll tell you about my adventures some day. Let’s continue as we are, then. Beautiful marquise, enjoy all the pleasures of your sex, and I shall enjoy all the freedom of mine.

The day after the wedding they received the usual compliments and, eight days later, left for the provinces, where they still live in one of their châteaux. The uncle should visit them there: he would find, to his surprise, that a beautiful child has resulted from their marriage – one to put paid to his hopes of a rich inheritance.

#Charles Perrault#François-Timoléon De Choisy#genderqueer folktales#trans representation#laura retells#except not really it's more like laura copy pastes this time

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Study of François-Timoléon de Choisy

Born in Paris, among the notable Frenchmen of the seventeenth century, the Abbé de Choisy, also known as François Timoléon, has left for posterity a vivid firsthand description of a strong cross-gender wish. During his infancy and early youth, his mother had attired him completely as a girl. At eighteen this practice continued and his waist was then "encircled with tight-fitting corsets which made his loins, hips, and bust more prominent." As an adult, for five months he played comedy as a girl and reported: "Everybody was deceived; I had [male] lovers to whom I granted small favors."

In 1676, attended Papal inaugural bal in a female attire. In 1687, he was received in the Académie de France. In 1696 he became the Ambassador of Louis XIV to Siam. Regarding his gender identity he wrote, I thought myself really and truly a woman. I have tried to find out how such a strange pleasure came to me, and I take it to be in this way. It is an attribute of God to be loved and adored, and man - so far as his weak nature will permit - has the same ambition, and it is beauty which creates love, and beauty is generally woman's portion ... . I have heard someone near me whisper, "There is a pretty woman," I have felt a pleasure so great that it is beyond all comparison. Ambition, riches, even love cannot equal it ...

He wrote a number of religious works but he is nonetheless attributed as the primary author of The Story of the Marquise-Marquis de Banneville; a short story that reads like a fairytale.

Written By: Julio Estrada with contributions from Dallas Denny.

Sources:

Denny, Dallas. Current Concepts in Transgender Identity. New York: Garland Pub., 1998. Print.

#François-Timoléon de Choisy#trans#transgender#crossdresser#fairytales#stephanie barbe hammer#comp lit#comparative literature#complit022b#complit22b#historical#indie group project

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Yury (Georges) Annenkov (Russian/French, 1889–1974). Illustration to Histoire de Madame de Sancy by François-Timoléon de Choisy.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Transvestite Memoirs of the Abbe de Choisy

The Transvestite Memoirs of the Abbe de Choisy

François Timoléon, Abbé de Choisy, was not only a man of the church, but also France’s most famous cross-dresser of the 17th century. As kid, he played dressing up with Louis XIV’s brother. As adult, his love for opulent dresses carried on and he even lived as a woman for a while. The Transvestite Memoirs is an account on how he transformed from male to female and what obstacles he met, while…

View On WordPress

#17th century crossdressing#17th century homosexuality#17th century transvestite#Comtesse des Barres#Madame Sancy#Marquis-Marquise de Banneville#The Transvestite Memoirs of the Abbe de Choisy#Versailles crossdressing

0 notes