#Ferde Grofé

Text

Vox Satanae: Episode #575 - A Tribute to Magister Neil Smith

Vox Satanae – Episode #575

19th-20th Centuries

A Tribute to Magister Neil Smith

This week we hear works by Sergei Rachmaninoff, Dmitri Shostakovich, Giacomo Puccini, George Gershwin, Ferde Grofé, P.D.Q. Bach, and Andrew Lloyd Webber.

140 Minutes – Week of April 15, 2024

Stream Vox Satanae Episode 575.

Download Vox Satanae Episode 575.

View On WordPress

#Andrew Lloyd Webber#classical instrumental music#classical music#classical vocal music#Dmitri Shostakovich#Ferde Grofé#George Gershwin#giacomo puccini#magister gene#p.d.q. bach#radio free satan#Sergei Rachmaninoff#vox satanae

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vijf jaar geleden: Grupetto speelt Gershwin

Vijf jaar geleden trad de zes-koppige groep Grupetto op in zaal Roxy te Temse. Zij zetten de memorabele George Gershwin in de spotlights door “Rhapsody in Blue” uit te voeren, “Swanee” en nog andere van zijn composities. Wie van muziek houdt kan niet voorbijgaan aan Gershwin omwille van zijn baanbrekend werk: hij creëerde een mengvorm van jazz en klassieke muziek.

Continue reading Vijf jaar…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A Fantasy in Blue

Ferde Grofé (1892 - 3 aprile 1972): Metropolis – a Fantasy in Blue per orchestra (1928). Han-Louis Meijer, pianoforte; The Beau Hunks, dir. Jan Stulen.

youtube

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

🍓🌵🍄

🍓 ⇢ how did you get into writing fanfiction?

When I started plotting fanfic versus when I started actually physically writing it is different. I was always so sad when bad things happened in my shows :( that I would just make up fix-its (though I didnt call them that because I was five) where all the characters were happy (I watched a lot of adult shows, sad things were happening all the time).

When I was old enough for school, I would always use character names for my worksheets (god. there were three. if youve been on tumblr for five minutes you can take a guess which three.)

For assignments, I wrote stories inspired by shows and movies I'd seen (usually very dark and definitely not for children lmao). Perhaps the most obvious example of this was the 22-page story I wrote in fifth grade which was a blatant Charmed x Supernatural crossover with most of the character names changed. (I think the funny thing was I didn't even include the sisters, just a side character they had helped in one episode who was the protagonist of my story. Saying this now, that's about as fanfic as u can get lol).

The first piece of actual fanfiction I can find is a 15-line fic I made when I was twelve. The 2nd was a 40 word whump snippet. The third was a 350 word crackfic (same fandom as the first).

I seemingly took a break for a while as I discovered you could read other people's fanfiction and promptly devoted all my free time to it.

I continued physically writing but it was all original fiction, not fanfic. I started physically writing fanfic snippets again (whump) a few years ago for an interest of mine and eventually started doing it for more fandoms, leading to now where I'm working on completing my ~10k White Collar fic.

🌵 ⇢ share the link to a playlist you love

I actually don't listen to any playlists surprisingly, except my own which are just grouped by genre. I do enjoy "Grand Canyon Suite" by Ferde Grofé. Love "Painted Desert". I also like the soundtrack for the game A Short Hike.

🍄 ⇢ share a head canon for one of your favourite ships or pairings

I like to think the Neal celebrates all the holidays with the Burke's. It's already established he goes to their house a lot, but I like the idea of them doing various holiday things especially since Neal likely never got the best version of that growing up.

Thanks for the ask!!! :D

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ferde Grofé: Grand Canyon Suite. Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra - 1950.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

lately ive had a big band jazz cover of ferde grofés grand canyon suite in my head sunset especially. now can someone tell me WHERE to find a piano soundfont for lmms before i go bananas

0 notes

Text

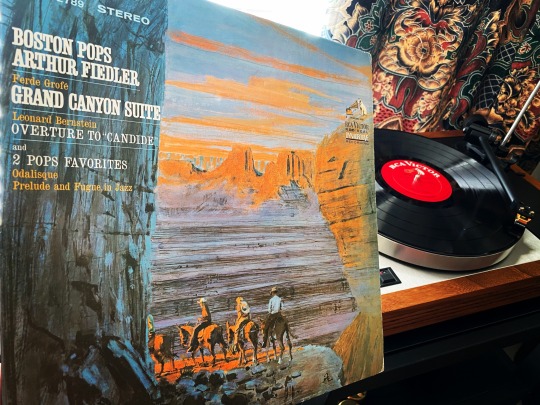

Heading off to the Grand Canyon this morning (musically speaking that is). Fans of A Christmas Story will recognize the track “On The Trail”

#ferde grofé#leonard bernstein#grand canyon suite#overture to candide#classical music#nowspinning#vinyl#33 1/3 rpm

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Canyon Suite: V. Cloudburst · Ferde Grofé - Leonard Bernstein - New York Philharmonic

I found this song with #BeatFind

Grand Canyon Suite: V. Cloudburst · Ferde Grofé - Leonard Bernstein - New York Philharmonic

1 note

·

View note

Photo

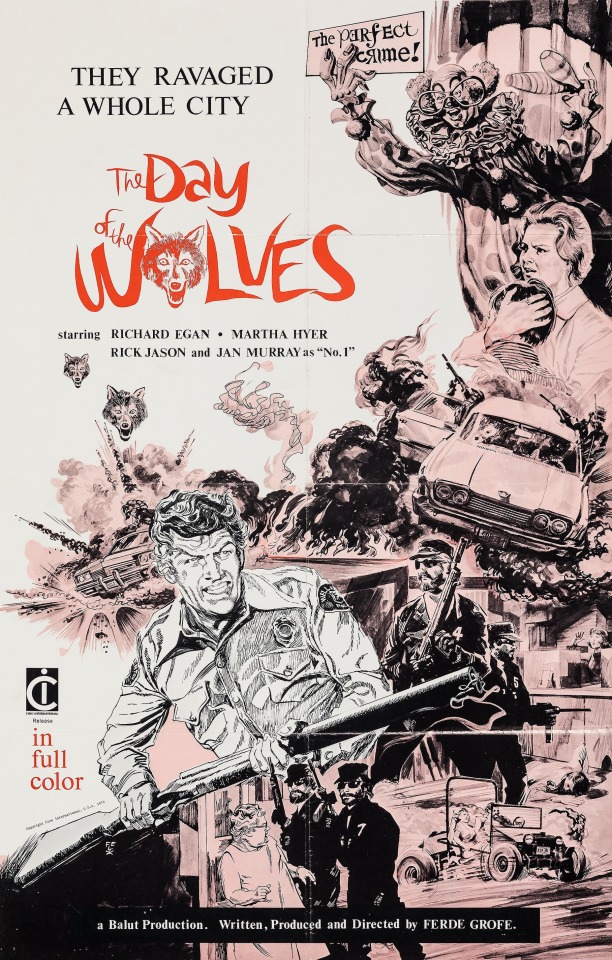

Affiche argentine du film de Ferde Grofé Jr., ''The Day of the Wolves'' (1972), dessinée par Felix. - Source Heritage Auctions.

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trylon and Perisphere, May 18, 1939. Photograph by Samuel H. Gottscho, from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

April 30th marks the 80th anniversary of the opening of the New York World’s Fair. Driving for Deco could not let that milestone pass without a post about it. Of course the entire fair fits the category of “vanished New York City Art Deco”. But this two-part post will look at the fair’s “theme center”, the Trylon and Perisphere.

The news of a proposed New York World’s Fair hit the newspapers on September 23, 1935. The recent success of The Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago made planners in New York feel that a fair in the city would reap huge economic benefits. After a short search, the site chosen for the fair was a large ash dump in Queens near Flushing Bay. Reclaiming the over 1,000 acres and the construction of the fair took less than four years.

Mark Washington Inaugural

According to the committee’s plans, the fair would be opened on April 30, 1939, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the inauguration of George Washington as the first President of the United States in New York City on April 30, 1789. The entire exposition, which has yet to be named, would celebrate not only that single event but the establishment in that same year of the government of the United States.

New York Herald-Tribune, September 23, 1935, Pg. 1

James Earle Fraser’s enormous statue of George Washington on Constitution Mall at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair. Photograph by William A. Dobak from the collection of The Museum of the City of New York.

The large statue of the Washington near the center of the fair grounds would try to remind visitors of the initial reason for the exposition. But the committee’s vision of the fair changed considerably before the opening day. Instead of looking back, the theme of the fair looked forward.

October 9, 1936 New York Times Headline. Image from Proquest Historical Newspapers.

At an October 8, 1936 press conference, the board of directors of the New York World’s Fair of 1939 formally announced their plans. The New York Times reported the next day:

The exhibits and amusements covering an area of 1,216 1/2 acres, keyed to the theme of “Building the World of Tomorrow,” are being planned with a view to a total investment of $125,000,000, and are expected to attract 50,000,000 visitors in a year’s time, with a daily maximum capacity of 800,000.

New York Times, October 9, 1936, Pg. 1

At the same conference, President of the Fair, Grover Whalen told the press “The theme, is the creation of a better world and fuller life – the advancement of human welfare. This would be on display in the ‘theme building’. At 250 feet the theme building would tower over the rest of the fair, whose buildings would not be much higher than two stories. Inside the “Theme Building” a panorama visualizing the “theme” shows how tools of today’s civilization have been developed in the 150 years since the inauguration of George Washington.”

Sketch of the proposed “Theme Building” of the New York World’s Fair. Showing one of the 250 foot tall towers. Image from MCNY.org

Five months after announcing theme “the world of tomorrow”, the “theme building” underwent a radical redesign. Instead of a traditional building in a modern style, the design became futuristic and abstract.

March 16, 1937 headline from the New York Herald-Tribune, Pg. 23A. Image from Proquest Historical Newspapers

A sphere and an obelisk of fantastic proportions will compose the dominant architectural theme of the New York World’s Fair of 1939. The sphere will house the “theme exhibit” – a portrayal of “the basic structure of the world of tomorrow” – and will appear to be suspended above a circular pool. Actually the huge white globe will be supported by eight steel columns encased in glass and hidden from sight by clusters of fountains.

The sphere will be 200 feet in diameter, or about equal to an eighteen-story building. Its interior will be a single vast auditorium, more than twice the size of Radio City Music Hall. A single entrance fifty feet above the pool will be reached by glass enclosed escalators.

A bridge will link the sphere to the obelisk. The obelisk will rise 700 feet. From the connecting bridge, a wide ramp 900 feet long, will slope to the ground in a three-quarter circle around the pool. The highest vantage point on the exposition grounds will be the bridge and the top of the ramp.

Upon entering the sphere, visitors will descend a short ramp and emerge on a moving platform which will rim the circular exhibition space. An amplified voice, accompanied by soft music, will describe the floor exhibits and the planets and constellations which probably will decorate the dome.

The moving platform will be suspended far above the exhibition floor and hung twelve feet from the wall, so that a view may be had from the railing on either side. Moving at the rate of thirty feet a minute, it will take fifteen minutes to carry a visitor from the entrance to the adjacent exit.

Mr. Whalen said that the architectural motif of the “theme center” was so new that technicians had to coin several new words to describe the structures. The obelisk, he said, will be known as a “trylon” – a combination of “tri”, referring to its three sides, and “pylon.” Indicating its use as a monumental gateway to the theme building, which he called a “perisphere.”

Plans for the two structures were prepared by the architectural firm of Harrison & Fouilhoux. The structures will be built at an estimated cost of $1,200.000.

The sphere will be floodlighted at night. Batteries of projectors mounted on distant buildings will spot the globe in color, while other projectors will superimpose moving patterns of light which may take the form of clouds, geometric patterns or moving panoramas. This will create the optical illusion that the sphere itself is slowly rotating.

The obelisk will not be illuminated. “Its sloping sides will fade into the night,” according to the plans, “giving the effect of a tower reaching to infinity.”

New York Herald-Tribune, March 16, 1937, Pg. 23A

Harrison and Fouilhoux 1937 patent drawing for the Trylon and Perisphere. Image from thepatentroom.com.

Model of the proposed “Theme Center”, 1937. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Construction

1936 – 1937

The formal dedication of the fair occurred on June 3, 1936. At the Flushing site, Grover Whalen led the directors over a 90 foot ash mound and discarded tires to a tower erected for the ceremony. With a vantage of 150 feet above the dump, Whalen broke a bottle of 1923 champagne, christening the fair. Shortly thereafter the herculean task of grading the site began. Accompanied by the 65 piece Department of Sanitation Band, Grover Whalen, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and Park Commissioner Robert Moses broke ground on June 29th.

New York City Mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia watches with amusement while Grover Whalen breaks ground for the 1939 New York World’ Fair, June 29, 1936. Image from

With the groundbreaking at the Corona Ash Dump, grading the site began. Full grading of the future park took about a year. The driving of wooden piles into the marshy land, to support the future fair building, began in 1937. With less than two years to go construction crews worked in three shifts around the clock.

Surveying the fair site in 1938, showing the piles driven into the marshland. Image from mcny.org.

With the pilings in place, construction of the fair buildings began in earnest during 1938. Soon the Trylon and Perisphere would rise and dominate the skyline of the borough of Queens.

Site of the future and futuristic “Theme Center”, May 28, 1937. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

1938 – 1939

During the winter of 1938 construction begins on the “Theme Center”. There is less than 14 months until the opening day of the fair.

March 21, 1938. The first steel is laid for the Perisphere. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

March 22, 1938. The Trylon is already rising from its base as work begins on the Perisphere. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

#gallery-0-29 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-29 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-29 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-29 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

The drum girder. This is the base that the Perisphere will rest on.

The drum girder in place, soon the frame work for the cranes to construct the Perisphere will be built on it. Image fron NYPL Digital Collections.

#gallery-0-30 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-30 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-30 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-30 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

April 21, 1938. Little more than one year until opening day. The frame for the cranes to construct the Perisphere is in place. And the Trylon grows higher. Image from the NYPL Digital Collections.

The Perisphere starts to take shape in the early spring of 1938. Richard Wurts photograph from MCNY.org

By late spring 1938, the Perisphere’s outer steel work neared two-thirds completion. And already finsihed was the frame-work for the bridge connecting it to the Trylon. Inside that bridge the world’s longest (at the time) escalator would carry visitors up inside the Perisphere.

June 13, 1938. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

By July the construction of the Trylon topped off. World’s Fair publicity listed the Trylon’s height at 700 feet. The actual height came to 610 feet, even so it became the tallest structure on Long Island. The Perisphere also had the same size embellishing, claiming a diameter of 200 feet. Its size at 180 feet or eighteen stories was still impressive. As the Perisphere’s framework neared completion, the construction workers playfully dubbed it “the big apple”, due to the red rust proofing paint use on the steel.

#gallery-0-31 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-31 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-31 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-31 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Looking up the frame work of the Trylon, summer, 1938. Wurts Bros. photo from the collection of mcny.org

Summer, 1938 showing the topped off Trylon. Wurts Bros. photo from mcny.org

#gallery-0-32 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-32 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-32 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-32 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

The steel framework of the Perisphere nears completion, summer, 1938. Richard Wurts photo from mcny.org.

Richard Wurts photo looking down from the top of the Trylon on the nearly complete framework of the Perisphere. Construction of the Helicline is underway. Summer of 1938. Image from mcny.org

By August and the “Theme Center’s” steel work complete, it was time to dedicate the Trylon and Perisphere. Grover Whalen and Mayor LaGuardia hosted the ceremony with Ferde Grofé and his orchestra providing the music. After the first musical number, Mayor LaGuardia drove the last rivet into the Perisphere.

Friday August 12, 1938, grounds set up for the dedication of the Trylon and Perisphere. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Now the time had come to encase the Trylon and Perisphere in scaffolding and to cover them in plywood and gypsum . The entire structure then received coatings of pure white paint. The only pure white buildings at the World’s Fair were the Trylon and Perisphere.

Scaffolding starts to cover the “Theme Center”, September 23, 1938. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Autumn, 1938 and scaffolding almost completely encases the Trylon and Perisphere. Wurts Bros. photograph from mcny.org.

Workmen nailing the plywood covering of the Trylon. Winter, 1939. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

#gallery-0-33 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-33 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-33 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-33 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

The gypsum covered top of the Perisphere in the winter of 1939. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Early winter of 1939 and the Trylon and Perisphere is still shrouded in scaffolding. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Industrial designer, Henry Dreyfuss, won the commission for creating the “Theme Center” exhibit. Entitled Democracity it provided visitors a look at a utopian city in the year 2039. While on the inside of the dome visions of workers and the constellations would be projected. CBS newscaster H. V. Kaltenborn provided narration explaining to the visitors what they were seeing. Two platforms, moving in opposite directions, transported people around the inside of the Perisphere in six minutes. One revolution equaled a twenty-four hour period.

#gallery-0-34 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-34 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-34 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-34 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Workers prepare the interior of the Perisphere, winter of 1939. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Detail of the of the platforms during the construction of the Perisphere. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Winter 1939 and the scaffolding is coming down to reveal the gigantic pure white sphere and obelisk. Photo by Gottscho & Schleisner from the collection of mcny.org

#gallery-0-35 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-35 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-35 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-35 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Almost finished. Late winter, 1939. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

A dramatic view of the Helicline, Perisphere and Trylon. Less than two months until opening day. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

April, 1939 and ready for the public. Construction of the massive “Theme Center” took just over a year. It dominated the fair grounds and instantly captured the world’s attention.

April, 1939. Ready to open. (Photo by George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images)

Part Two will look at the Trylon and Perisphere during the run of the World’s Fair and its fate after the closing in 1940.

Anthony & Chris

If you enjoyed this post check out these earlier World’s Fair related posts:

New York World’s Fair Souvenirs 1939 – 1940

Reference Library Update – Heinz Exhibit Brochure, 1939 New York World’s Fair

Reference Library Update: The Great Lakes Exposition, 1936

Vanished New York City Art Deco: The Trylon and Perishpere – Part One Construction

#1939#1939 New York World&039;s Fair#Art Deco#Ferde Grofé#Fiorello LaGuardia#Flushing Meadow-Corona Park#George Washington#Grover Whalen#Henry Dreyfuss#J. André Fouilhoux#New York City#Queens#Robert Moses#Trylon and Perisphere#Wallace Harrison

0 notes

Link

Mi crítica del último concierto de abono de temporada de la ROSS ayer en el Maestranza.

#real orquesta sinfónica de sevilla#juan pérez floristán#john axelrod#duke ellington#leonard bernstein#george gershwin#ferde grofé#jacek policinski#ross#música#music

0 notes

Photo

josh_gvf: The “Grand Canyon Suite” written and composed by Ferde Grofé, a body of work buried at the back of my mind for far too long, had, at first encounter with the mighty gorge, reawakened. The melodies leaping forth, beckoning from afar and drawing nearer like a fierce wind to carry the body out over all before me so that I may marvel at its glory.

#greta van fleet#jake kiszka#josh kiszka#teddy graham#tarzan#ig#im deaDS#looks like they are holding haNDS

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

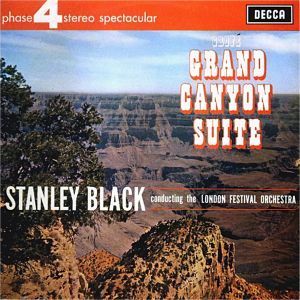

Stanley Black

Ferde Grofé’s Grand Canyon Suite (1963)

Stanley Black – 01 – Sunrise (5:40)

Stanley Black – 02 – Painted Desert (5:24)

Stanley Black – 03 – On The Trail (7:23)

Stanley Black – 04 – Sunset (4:27)

Stanley Black – 05 – Cloudburst (8:56)

Stanley Black published first on https://soundwizreview.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Dancing IS the Jazz Age….Jazz is dancing music. Swing is Jazz music.

(L:) Sheet Music cover. Stumbling: a Fox-Trot Oddity. Confrey, Zez. New York: Leo Feist, Inc. 1922. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries. (R:) Sheet music cover. Blame it on the Waltz. Kahn, Gus, music by Alfred Solman. New York: Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1926. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

American jazz and popular dance tunes- for the foxtrot and other 1920���s and 30’s dances, dominated nightlife and entertainment in the movies and live performance.

The 1920s represented a period of “new wildness” and vibrancy created in the aftermath of the first World War in Europe and America. Coined the “Roaring Twenties,” the decade became popular for the rise of jazz and dance culture. With its origins in the United States, many of the dances were heavily influenced by the Harlem neighborhood’s timed dances and short, rhythmic beats, popularized by musicians and dancers in nightclubs in New York such as the Cotton Club and Savoy Ballroom. Prior dancing trends were based upon historical styles from before WW I such as traditional ballroom dancing- the one step, tango, as well as the dances popularized by the Ragtime genre.

Waltz: A derivative left over from previous ballroom styles of the early twentieth century, the waltz became intertwined with the Jazz Age through flowing footwork and dramatic facial expressions. This style of dance was characterized by small, double steps and the dance was fairly contained and restrained. Generally, it did not display the sense of swooping and the broad motion associated with modern, competition ballroom Waltz, or the high-speed, rapid rotation of the Viennese Waltz.

Fox Trot: The Fox Trot dance arose in the 1910s and was known as the “One Step.” With the advent of World War I, it was quickly forgotten but reappeared again in the 1920s as the “Fox Trot.” The foxtrot dance is known for its smoothness, characterized by long, continuous flowing movements across the dance floor. This dance is commonly accompanied with big band music and is stylistically similar to the Waltz, although the rhythm is in four-quarter instead of a three-quarter time signature.

(L:) Sheet music cover. Suez; Oriental fox-trot romance. Ferde Grofé; Peter De Rose. Wohlman Studios, illustators. New York: Triangle Music Pub. Co. 1922. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

(R:) Sheet music cover. Charleston Cabin: (song melancholy). Reber, Roy and Sidney Holder. Irving Politzer, illustrator. New York: E.B.Marks Music Co. 1924 Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

The Charleston: This dance emerged in the 1920s when it accompanied James P. Johnson’s song “The Charleston” in the 1923 Broadway musical Runnin’ Wild. The variety of Charleston variations exploded with the advent of Charleston contests, for both solo dancers and couples across the world. Known for its complex footwork, the dance requires stepping backwards and then forwards, all the while kicking one’s legs out to the side. The second step is to move forwards and kick a front leg out, followed by moving backwards and kicking a leg back. The final step is to put both hands on both knees and move side-to-side by moving the knees apart and then together.

Sheet music cover. Doin’ the Raccoon. Coots, J. Fred and Raymond Klages. New York: Remick Music Corp. 1928. Uncat. Smithsonian Libraries.

While ballroom dancing still resonated with older and more conservative men and women, the new dance crazes appealed to the younger generation who valued extreme sports, frivolity, and looser morals. In the period between the Wars, many young Americans were chastised by their elders for violations against decency, including using slang, performing “low-class” dances, and enjoying syncopated music with African American influences. During the Roaring Twenties young Americans responded to this criticism by broadening all of these “violations,” with more outrageous slang, jazzier music and dance, shorter and flimsier dresses and even shorter hair in reaction against these social rules of modesty and gender. There was no formal training for these new dances; the various steps, movements, and styles were informally “picked up” by party goers who would travel from one club to the next. It was, thus, in dance halls across the country in the 1920s that free form social dancing emerged.

This post was written by Elizabeth Broman and Sylvia Ferguson. Elizabeth is the Reference Librarian at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library. Sylvia Ferguson is a graduate student in the MA History of Design and Curatorial Studies program offered at Parsons The New School of Design jointly with Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

from Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum http://ift.tt/2ulHCd3

via IFTTT

12 notes

·

View notes