#El Salvador Community Corridor

Text

Nobody Drives in LA -- The Los Angeles Grand Tour

Nobody Drives in LA — The Los Angeles Grand Tour

The Grand Tour, for the unfamiliar, was a custom that arose in Britain in the mid-1600s, which involved upper class young British men touring around Europe as part of their cultural education. By the 1800s, the custom had spread from the British upper classes to the nouveau riche of Europe, the Americas, and the Philippines. Although initially limited to men — accompanied by a chaperone and…

View On WordPress

#Chinatown#El Salvador Community Corridor#Filipinotown#Frenchtown#Greek Town#Koreatown#Little Armenia#Little Bangladesh#Little Belize#Little Brazil#Little Italy#Little Odessa#Little Osaka#Little Tokyo#Nobody Drives in LA#Oaxacatown#Sonaratown#Tehrangeles#Thai Town#Yaangna

1 note

·

View note

Text

Five Interesting Salvadoran Non-fiction Books

"Solito : A Memoir" by Javier Zamora

Javier Zamora’s adventure is a three-thousand-mile journey from his small town in El Salvador, through Guatemala and Mexico, and across the U.S. border. He will leave behind his beloved aunt and grandparents to reunite with a mother who left four years ago and a father he barely remembers. Traveling alone amid a group of strangers and a “coyote” hired to lead them to safety, Javier expects his trip to last two short weeks. - (Amazon.com)

2. "The Salvador Option: The United States in El Salvador, 1977-1992" by Russell Crandall

El Salvador's civil war between the Salvadoran government and Marxist guerrillas erupted into full force in early 1981 and endured for eleven bloody years. Unwilling to tolerate an advance of Soviet and Cuban-backed communism in its geopolitical backyard, the US provided over six billion dollars in military and economic aid to the Salvadoran government. El Salvador was a deeply controversial issue in American society and divided Congress and the public into left and right. Relying on thousands of archival documents as well as interviews with participants on both sides of the war, The Salvador Option offers a thorough and fair-minded interpretation of the available evidence. If success is defined narrowly, there is little question that the Salvador Option achieved its Cold War strategic objectives of checking communism. Much more difficult, however, is to determine what human price this 'success' entailed - a toll suffered almost entirely by Salvadorans in this brutal civil war. - (barnesandnoble.com)

3. "Defender el agual" by Robin Broad and John Cavanagh

If you had to choose, would you trade water for rivers of gold? More than 20 years ago, mining corporations posed this dilemma to the people of El Salvador, under the promise that the precious metals industry would be synonymous with progress. But "green mining" only brought with it poisoned basins and springs, as well as the persecution of those who stood up against the dispossession and destruction. Robin Broad and John Cavanagh recount here the improbable triumph of those in El Salvador who decided to defend water and formed a popular resistance movement that confronted death and corruption through political ingenuity and the creativity of community organizations. This story, in which narrative journalism is mixed with legal and historical chronicle, takes us from the beautiful landscapes of Cabañas and Chalatenango to the cold corridors of the World Bank in Washington, where the fate of the small town's water resources was settled. . Central American nation. Rather than an isolated success story, the story Defending Water tells gives many reasons to enhance the optimism and conviction of those who will never believe that money is worth more than water or, in other words, more than life. - (barnesandnoble.com)

4. "State of War" by William Wheeler

One of President Donald Trump’s favorite rhetorical motifs is stoking fear that members of the MS-13 gang from El Salvador intend to cross the U.S. border in force and wreak havoc on American society. It’s an inaccurate scenario, and in State of War, foreign correspondent William Wheeler tells the real story: In the 1980s, the U.S. supported the repressive Salvadoran government in a brutal civil war, and many Salvadoran families fled to America—especially Los Angeles, where teenagers in poor neighborhoods founded MS-13. A decade later, the U.S. responded to rising anti-immigrant sentiment by deporting many Salvadorans back home. Ever since, El Salvador has been one of the most violent countries in the world. (barnesandnoble.com)

5. "Made in El Salvador" by Roberto Valencia

The chronicle is the novel of reality, Gabriel García Márquez once said. With that maxim as its guiding principle, Made in El Salvador compiles sixteen of the best chronicles and profiles that journalist Roberto Valencia has signed over a dozen years. A muscular book, full of surprising stories and endearing characters, with blue and white as the flag. Salvadoran export journalism. -(Amazon.com)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Women using technology for good

A drought early-warning system with women and technology at the forefront.

In the Dry Corridor of Central America, persistent drought—interrupted by violent storms that do further damage to crops—is driving farmers from land they’ve cultivated for generations. The climate crisis is obviously a sober topic, but on a clear day in October outside the town of San Antonio del Mosco in El Salvador, you wouldn’t know it. Here, seven women have gathered in an open field for a practice session with a new tool for predicting the future: a drone.

And they’re loving it.They joke, laugh, and hug as they set out to demonstrate their expertise at assembling and launching it into the air. Even the drone, with its arms and legs outstretched, looks exuberant.

Ana Hernández steps up first to show how it’s done. She has been an avid participant in a series of projects organized by Oxfam and partners that are focused on helping women take the lead in reducing disaster risks. When she’s not cultivating her land and caring for her two youngest children, Ana is coordinating her town’s civil protection commission, participating in women’s leadership initiatives, and taking university courses to deepen her knowledge of disaster-related topics.

So, where do drones come in? They’ll enable the women to monitor water levels in the rivers, crop growth in the fields, and areas badly affected by drought—without navigating all the rough terrain they’d otherwise need to travel. And in emergencies like floods, they can help locate people whose lives may be in danger.

Hernández puts the drone through its paces and brings it in for a smooth landing, and she’s pleased with the results. “For me, fear and nervousness about operating drones are in the past.”Inmer Arguenta Ramos, a technician from the local organization Fundación Campo (FC), cheers from the sidelines. She has been training the women and is pleased with the results. “The women overcame their fear of using the technology, and it strengthened their self-esteem.”

FC is a rural-development organization that Oxfam works closely with on programs to reduce disaster risks in the Dry Corridor. Their projects—which include economic development and natural resource protection, as well as disaster management—emphasize gender equity and youth empowerment. Oxfam has helped FC build on their technical and analytical skills so they can carry out effective, well-targeted humanitarian activities in communities hit hard by drought and other emergencies. (Read more about Oxfam’s commitment to local humanitarian leadership.)

“In my community there are 200 women taking part in projects based at our multi-threat center,” says Hernández, referring to an Oxfam-funded base of operations. “They are working on civil protection commissions and participating in agricultural field schools.”

Oxfam and partners are working with more than 3,000 participants in 30 communities in rural El Salvador, providing training in disaster preparedness and risk reduction, linked to programs to help women—who have traditionally been excluded from leadership—hone their skills at taking charge.

“Women have so much energy and capacity, and there are no limits to what we can learn,” she says. “My big dream is to see all the women in my community trained and empowered. I feel that we are achieving it.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

COVID-19 fuels the threat of global famine

The pandemic has exacerbated food insecurity around the world. The World Food Program is short of resources to alleviate hunger.

Conflicts, climate change and now COVID-19 are the three C’s driving 270 million people to famine in the most impoverished countries in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Central and Latin America. Officials at the World Food Program (WFP), the hunger relief arm of the United Nations that feeds about a hundred million people each year in some 88 countries, warned that they are running out of resources to meet the demand for staple foods and thus prevent people dying from starvation.

“We are asking globally $13.5 billion for our budget this year, but we forecast being able to raise only about $7.8 billion,” said Steve Taravella, WFP’s senior spokesperson at a briefing organized by Ethnic Media Services on Feb. 26.

Before the pandemic, there were about 135 million people acutely hungry in the world, but the collateral economic impacts of the virus have doubled that number. WFP estimates that in 2021, about 19,000 officials working in developing countries will have to duplicate efforts to serve at least 120 million people, in hardest-hit places like Yemen, South Sudan, Nigeria and Burkina Faso.

“For some years WFP and others working on global hunger were really effective in bringing hunger down to what we hoped would be the zero hunger goal of the UN by 2030. It’s pretty clear now, that’s not going to happen,” Taravella said. “COVID is making the poorest of the world poorer and the hungriest of the world hungrier.”

WFP won the Nobel Peace Prize last year for its efforts to eradicate hunger in areas where natural disasters and conflict have disrupted normal food distribution channels. Areas where bombed roads prevent trucks carrying flour, rice, lentils, peas, cooking oil and salt from getting through. Areas where airstrikes destroy planes carrying dietary supplies. Areas where incessant fighting prevents hungry people from venturing out for food or aid workers from moving safely to provide it, at a time when crops cannot be harvested.

“There have been terrorist acts against villagers and aid workers by Al-Qaeda Al-Shabaab, Boko Haram and ISIS,” Taravella said. Recently, a WFP staff member was killed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo while accompanying the Italian ambassador on a visit to a school feeding site.

WFP provides school meals in the classrooms, helps pregnant women and new mothers to understand nutrition, and supports small farmers to find markets for their produce.

“We work very closely with governments but we see ourselves there only as a temporary band-aid. Our goal is to help build the country’s capacity to manage the programs,” said Taravella.

Although the WFP does not operate food banks in the United States, immigrants in the country have contributed greatly to alleviating hunger in their homelands after natural disasters such as the typhoon that devastated the Philippines or the hurricanes in Central America. But COVID has also impacted remittances.

Devastating hurricanes

“When COVID hit, we were really hoping that the hurricane season will be a quiet one as we had a few years ago, but that was not the case,” said Elio Rujano, communications officer for the WFP’’s regional bureau for Central America and the Caribbean.

The 2020 season produced 30 named storms, of which 13 became hurricanes, six of them devastating in scope. Eta and Iota ravaged areas in Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua while tropical storm Amanda hit El Salvador. Since 2014, these countries have already been experiencing prolonged periods of droughts or excessive rains caused by the El Niño phenomenon, both causing the destruction of crops and the livelihood of farmer families.

“In the past we were only focusing on the dry corridor where rural farmers live, but now, because of the pandemic, hunger has expanded to urban areas,” Rujano said from his Panama City office. “50% of the labor in Latin America and Central America is informal labor. People work on the streets, and since they could no longer go out, they couldn’t meet their basic needs.”

Back in 2018, hunger in the region was affecting 2.2 million people and that number is approaching nearly 8 million in 2021.

Here WFP works to support communities to become more resilient to climate change. They teach them to replace the plantation of fragile products such as beans and maize with beekeeping, since honey can be stored for longer periods. They also provide people with cash transfers to buy food at local shops and teach them about nutrition.

Rujano estimates that they could serve up to 2.6 million people this year if they reach $47 millions in donations to reach that population.

Malnourished children in Yemen

Although the situation in Central America is worrying, in places like Yemen where conflict is the main driver of the hunger crisis, the figures are even more chilling. Since the end of 2018, this country has been described as the home of the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. Six years of war between the Houthi rebels who control the north of the country and the nationally recognized government dominating the south, have devastated infrastructure, destroyed agricultural land, eroded government services and left the healthcare system on its knees.

About 4 million people out of a population of 30 have become internal refugees while food prices are on average 140 times higher than before the war.

“The hunger situation right now in Yemen has hit a new peak,” said Annabel Symington, head of communications for the WFP in Yemen. “The forecast for 2021 is that 50,000 people are already living in famine like conditions, another 5 million are at severe risk of falling into famine and about 11 million people are facing crisis levels of food insecurity,” she added.

Famine occurs when malnutrition is so widespread that people are literally starving from lack of access to nutritious regular food.

WFP assists more than 12 million people in Yemen – its world’s largest operation – delivering flour, pulses, oil, sugar and salt, as well as canned goods for those who do not have immediate access to kitchen equipment such as the case of the internal displaced people.

The conflict has contributed to nearly half of all children under the age of 5 in Yemen facing acute malnutrition, which not only affects their physical and cognitive development, but puts them at risk of death. 11.2 million pregnant or breastfeeding mothers are also malnourished and according to Symington these numbers can be an underestimate.

Mothers are resorting to desperate measures to survive: either they eat less to feed their children or they must choose which of their kids eat.

After COVID, death rates skyrocketed, but as the testing capacity is limited, it is unknown for sure how many people contracted the virus. “The lockdown was lifted quite early because people will starve if they stay at home,” Symington said.

“It is clear that peace is what Yemen needs so we can address the food crisis,” she added.

Migrants in India

In India, the country with the highest number of food insecure people due to its large population (1.3 billion inhabitants), the pandemic worsened the living conditions for domestic migrants.

Almost 139 million people move from rural areas to large cities to work in informal jobs in factories or as street vendors. The coronavirus forced them to go back to their villages, and since transportation was not working, they had to move by foot, facing not only long hours of walking but hunger. The pandemic also disrupted the harvesting season in March and April affecting food supply chains.

“Although the restrictions (due to the pandemic) have been eased out and these people came back to the cities, there are very few jobs due to the economic slowdown,” said from New Delhi Parul Sachdeva, country advisor in India for Give2Asia, an NGO that supports grassroots organizations in 23 countries in Asia Pacific.

“Today 8 in 10 people are eating less food than before the pandemic and nearly 1 in 3 people face moderate or severe food insecurity.”

The government approved a package of US $22.6 billion for the distribution of staple foods during four months and cash transfers of $ 500 rupees (US $ 7) for up to three months. But informal workers were left out of the package, forcing civil society organizations to support those returning to their villages with meals, health supplies and shelter.

Organizations like Akshaya Patra distributed 1.8 million meals a day to children across India. GIve2Asia is now working on economic rehabilitation through training and input costs for agriculture.

“These are the kind of activities we wish to promote,” Sachdeva added. “I think they provide some kind of solution for livelihood regeneration in a country like ours,” she concluded.

You can donate to WFP here or via the Share the Meal app

Originally published here

Want to read this piece in Spanish? Click here

#COVID_19#Global Famine#World Food Programme#WFP#Hunger#Famine#Yemen#India#Central America#Guatemala#El Salvador#Nicaragua#English#Give2Asia

0 notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from The Conversation/EcoWatch:

Migration from Central America has gotten a lot of attention these days, including the famous migrant caravans. But much of it focuses on the way migrants from this region — especially El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua and Honduras — are driven out by gang violence, corruption and political upheaval.

These factors are important and require a response from the international community. But displacement driven by climate change is significant too.

The link between environmental instability and emigration from the region became apparent in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Earthquakes and hurricanes, especially Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and its aftermath, were ravaging parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and El Salvador.

In the years since those events, both rapid-onset and long-term environmental crises continue to displace people from their homes worldwide. Studies show that displacement often happens indirectly through the impact of climate change on agricultural livelihoods, with some areas pressured more than others. But some are more dramatic: Both Honduras and Nicaragua are among the top 10 countries most impacted by extreme weather events between 1998 and 2017.

Since 2014, a serious drought has decimated crops in Central America's so-called dry corridor along the Pacific Coast. By impacting smallholder farmers in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, this drought helps to drive higher levels of migration from the region.

Coffee production, a critical support for these countries' economies, is especially vulnerable and sensitive to weather variations. A recent outbreak of coffee leaf rust in the region was likely exacerbated by climate change.

The fallout from that plague combines with the recent collapse in global coffee prices to spur desperate farmers to give up.

These trends have led experts at the World Bank to claim that around 2 million people are likely to be displaced from Central America by the year 2050 due to factors related to climate change. Of course, it's hard to tease out the "push factor" of climate change from all of the other reasons that people need to leave. And unfortunately, these phenomena interact and tend to exacerbate each other.

Scholars are working hard to assess the scale of the problem and study ways people can adapt. But the problem is challenging. The number of displaced could be even higher — up to almost 4 million — if regional development does not shift to more climate-friendly and inclusive models of agriculture.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate Change and Central American Refugees

A non-exhaustive list of news articles:

Deportees From Immigration Raids Face Deadly Climate Change (Grist, 1/2016)

Climate Change is Contributing to the Migration of Central American Refugees (PRI, 7/2018)

“Every Day You Become More Desperate” - Extreme Weather in Central America’s Dry Corridor is Forcing Farmers to Make the Hardest Decision (Weather.com, 10/2018)

The Unseen Driver Behind the Migrant Caravan: Climate Change (The Guardian, 10/2018)

How Climate Change is Affecting Rural Honduras and Pushing People North (Washington Post, 11/2018)

How Climate Change Is Driving Central American Migrants to the United States (Texas Observer, 12/2018)

How Climate Change is Fuelling the U.S. Border Crisis (The New Yorker, 3/2019)

How Climate Change is Pushing Central American Migrants to the US (The Guardian, 4/2019)

Central American Farmers Head to the U.S., Fleeing Climate Change (New York Times, 4/2019)

Climate Change is Killing Crops in Honduras — and Driving Farmers North (PBS, 4/2019)

Climate Change and Health: Chronic Kidney Disease is On the Rise (Vox, 5/2019)

‘He Went Seeking Life But Found Death.’ How a Guatemalan Teen Fleeing Climate Change Ended Up Dying in a U.S. Detention Center (TIME, 5/2019)

Climate Change, CAFTA, and Forced Migration (IATP, 5/2019)

Climate Change is Devastating Central America, Driving Migrants to the U.S. Border (NBC News/InsideClimate, 7/2019)

‘It Won’t Be Long’: Why a Honduran Community Will Soon Be Under Water (The Guardian, 7/2019)

Living Without Water: The Crisis Pushing People Out of El Salvador (The Guardian, 7/2019)

'People are Dying': How the Climate Crisis Has Sparked an Exodus to the US (The Guardian, 7/2019)

How Climate Change is Driving Emigration From Central America (PBS, 9/2019)

Drought and Hunger: Why Thousands of Guatemalans are Fleeing North (The Guardian, 2/2020)

Where Will Everyone Go? (ProPublica, 7/2020)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

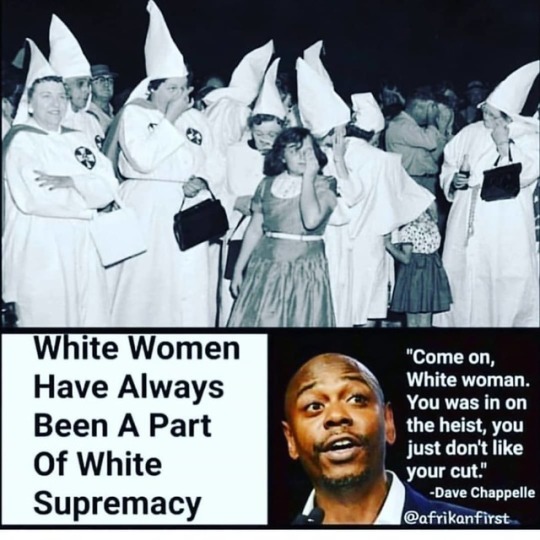

Dumb niggaz quote: White women are cool... They ain't like white men. Me: Miss Mc Beth always been the part of white supremacists.🤐 (at El Salvador Community Corridor - Los Angeles) https://www.instagram.com/p/B3XjavxDVOC/?igshid=jnbmdgh9sq2m

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Border: Three Problems. No Strategy.

Just slogans for Fox News and worse to come.

We just completed a 2700 mile ride from the Gulf to the Pacific following the US-Mexico border as closely as legally possible. We met people from across the political spectrum including ranchers, environmentalists, park rangers, border patrol, law enforcement, activists, and a bunch of other people living in the borderlands.

A thee week jaunt doesn’t make me an expert but we did deliberately seek out diverse opinions and listen to people’s experiences. Take these comments in that context.

So .. there are three overlapping problems at the border and (spoiler alert) a wall will not fix any of them but will create a whole set of new problems.

Men Seeking Work

Since the border was created 180 years ago, there has been a steady flow of workers from the south coming to work in the US. They arrive, work, pay their taxes, contribute to the local economy, send money home or go home. There are jobs that US workers do not want to do in our fields and factories and construction sites. Even migrants’ children who speak English and have an education do not want to pick radishes or gut chickens. There has always been a demand, and there will always be a supply. It is idiotic to claim that they are taking Americans’ jobs and it is even more stupid to spend billions on a wall or spend millions of dollars on border patrol resources and prisons to intercept and deport workers that America needs. A wall will not stop this flow when people can climb, fly, or tunnel.

If there was a sensible worker visa program, this problem would simply go away. This would free resources for other uses, stop migrants dying in the Sonoran desert or at the hands of coyotes, and move money from the hands of criminal smugglers into the hands of US communities.

Families Seeking Asylum

The countries to the south of Mexico - Guatamala, El Salvador, Nicaragua - are failed states. Climate change has decimated their agriculture - especially coffee - and gangs and drugs have decimated their civil society. Families are leaving in desperation to save themselves and their children. They would rather risk losing their children through separation in the US than lose them to gang violence at home. This is like osmotic pressure on the border and it is only going to increase unless the US helps fix these countries. There could be another million on their way but these migrants are turning themselves in legally at the major border ports of entry in the hope of finding a better life - despite Pres.Trump’s increasing cruelty and desperation to make them disappear. A wall will make no difference to this.

Drugs Seeking Markets

NAFTA expanded trade with Mexico and truck traffic increased 5x across the border providing lots of places to hide drugs. At the same time, NAFTA enabled cheap American corn and wheat to put Mexican farmers out of business.Throw in the opioid epidemic that is ramping demand for Mexican heroin and you have a perfect storm. Cartels have shifted their delivery routes from the Caribbean to Mexico and have found lots of unemployed Mexicans to grow new profitable crops and work as foot soldiers in the drug war. Drugs mainly come in through ports of entry but still also come across the open desert and, in neither case, will a “beautiful wall” make a bit of difference. Again, there is a huge demand that will be satisfied one way or another. If we stopped wasting resources on catching and jailing migrants, we’d have more resources to spend on the real problem of drugs. Many times we heard from border patrol that they are being diverted to process asylum paperwork instead of going after bad guys,

There are also three problems that we OUGHT to be dealing with but that we are ignoring when we are distracted by the Trump miasma of bullshit.

Healthcare Caravan

When staying in Columbus, NM we went over the border to Palomas for dinner. This is a tiny hamlet but has four dental offices and as many pharmacies catering to Americans looking for affordable healthcare. In Los Algodones across from Yuma, AZ there are over 300 dental offices and, in the peak winter season, over 6,000 Americans cross every day to see a Mexican dentist. The town is informally called “Molar City”. We don’t have caravans of latinos invading America, we have caravans of Americans invading Mexico for healthcare. This is a natural market response to the US healthcare nightmare but is a disgrace being hidden by the distractions.

Ecological Disaster

Any wall can be breached by humans but that is not the same for wildlife. When we met with a group of ranchers in the Sky Islands area of Arizona and New Mexico, they described their region between the Rockies and the Sierra Madre as one of the most diverse ecosystems in North America. They depend on the health of this area for their ranching livelihood, they have been looking after it for generations, and are upset that a wall will do permanent damage to wildlife corridors and the health of this land. Along the Rio Grande Valley the story is the same; a wall along the river will cutoff wildlife and ranches from the river and destroy the diversity and beauty of this wild place. We talked to a lot of deeply conservative people who were dead set against a wall.

Border Industrial Complex

There’s money to be made in borders and walls - construction with little oversight, technology for surveillance by contractors, prisons and transport for apprehended migrants, equipment and arms and trucks and service and housing and management. These are all multi-billion dollar businesses with lobbyists and committee chairmen and good old boys all over the establishment, This is becoming entrenched, self-perpetuating, and fundamentally corrupt.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

If you are searching for Asian Fusion in El Salvador Community Corridor then contact at Cheeky Cheeky Monkey. Visit: https://is.gd/CheekyCheekyMonkey

0 notes

Text

Trump Says He’s Sending the National Guard. On the Border, Many Aren’t Sure Why.

By Manny Fernandez, NY Times, April 5, 2018

MCALLEN, Tex.--They arrive a few dozen at a time, their children by their side, their belongings in government-issued plastic bags.

The immigrants who step inside a Catholic Charities relief center in this South Texas border city are the focus of national controversy, but their concerns are more logistical than political. One of the first things they do after sitting down is fix their shoes--most have spent a few days in federal detention before coming here; they had to remove their shoelaces, and now they sit in the center’s blue hard-backed chairs, tying up their shoes.

Dozens of immigrants, mostly from Central America, have been crossing illegally here every day, most of them scooped up by federal Border Patrol agents, given a court date and an ankle bracelet monitoring device, and dropped off at the downtown bus station. From there, they are led by volunteers to the nearby relief center, where they put their belts back on, eat a bowl of cereal, sort through donated clothes and change their infants’ diapers.

In the drama that is the migrants’ journey, this is the intermission--the limbo of waiting for the journey to start up again. And it goes on, seven days a week, morning to night, regardless of the news out of Washington.

“They will always come,” said Mariana Salinas, 43, who was apprehended crossing the Rio Grande on an inflatable mattress with her two sons last week after fleeing the threat of gang violence in her native El Salvador. “We’re doing it for the kids.”

Earlier this week, on the day White House officials announced that President Trump planned to deploy the National Guard to the southern border, Ms. Salinas was one of about 170 newly released immigrants who were assisted by the center. The day before, the number was about 140.

Mr. Trump on Thursday railed again at the flow of undocumented immigrants across the border but took credit on Twitter for reducing such crossings to a 46-year low. “We’re toughening up at the border,” Mr. Trump told an audience in West Virginia. “We’re throwing them out by the hundreds.”

There was little evidence of that this week at the border, where a steady flow of immigrants made their way out of the detention center, through the relief center, and from there, onward to cities around the country. Border apprehensions have slid significantly over the past year, but the Department of Homeland Security announced Thursday that illegal border crossings had surged in March: The 37,393 individuals apprehended on the Southwest border was a 203 percent increase over the same period in March 2017, though the number was lower than in 2013 and 2014.

“The number of illegal border crossings during the month of March shows an urgent need to address the ongoing situation at the border,” Tyler Q. Houlton, the department’s press secretary, told reporters in Washington. “As the president has repeatedly said, all options are on the table.”

But here in the Rio Grande Valley at the southern tip of Texas, one of the busiest corridors for human smuggling and illegal entry into the United States, the issue takes on a far more nuanced tone.

The Trump administration’s immigration policies were rarely mentioned in the dining room and lobby of the McAllen respite center. Although the center was busy, no one working to help handle the flow seemed to think they needed help from the National Guard. These immigrants were mothers and fathers, teenagers and infants--men with baseball caps changing their child’s diaper, mothers and daughters brushing their teeth for the first time in days at the bathroom sink, men eating bowls of chicken soup.

Many of the other Americans who live here--those who legally call the border home and have done so for years, sometimes generations--appeared to share the same view: There is no security crisis, only the daily challenge of meeting the basic needs of migrants who keep filling downtown McAllen.

“We’re not in a position where military zones are needed in our communities,” said Sergio Contreras, the president of a regional business group, the Rio Grande Valley Partnership. “It’s not something that’s helpful.”

Ismelda Cruz, 28, came from Guatemala. She, her husband and 7-year-old daughter crossed the Rio Grande at Reynosa, Mexico, fleeing the criminals she said were trying to recruit her husband. Asked if the presence of National Guard troops would deter people from making the journey from Guatemala, Ms. Cruz replied, “They’re always going to find a way through.”

Migrants who were recently apprehended, longtime residents and local officials in McAllen and other cities in the Rio Grande Valley said that with or without the National Guard, and with or without the White House’s increasingly anti-immigrant rhetoric, people would keep crossing. They worry that a deployment of troops would hurt the region’s economy and add to the inaccurate perception that Texas’ border cities were unsafe.

“We’ll get the bad publicity,” said Tony Martinez, the mayor of Brownsville, an hour’s drive to the east. “Nobody is sitting around here locking their doors and taping up their windows. It’s not a matter of security. Immigrants don’t want to migrate. They have to. This charade that Washington, or Trump more particularly, is imposing on the border is nothing more than empty rhetoric.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

UN: 1.4m need food aid in Central America, Sparking Migration

Five years of poor harvests in several Central American countries have left 1.4 million people struggling to feed themselves, according to the World Food Programme (WFP).

This now make some families see migration as their only remaining option.

In Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua, long dry spells and excessive rains have been destroying maize and bean crops, the UN agency reported on Friday in Geneva.

Maize and Bean are the main staple of subsistence farmers in the region, the UN agency said.

In a survey conducted by the WFP and government agencies in the affected countries, eight per cent of families indicated that they would leave their homes and search for more stable livelihoods within their country or abroad.

“Migration, though, is not a solution,’’ WFP spokesman, Herve Verhoosel, said, pointing out that the people, who stay behind will continue to suffer.

The WFP appealed for 72 million dollars from donor countries to help the region fund food aid.

Those donations would cover 700,000 people.

In addition, longer-term resilience programmes are needed so that farming communities can withstand prolonged poor harvests, Verhoosel said.

The weather and harvest situation in the so-called Dry Corridor that runs from southern Mexico to Panama was very much linked to climate change, the spokesman said.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Mexico becomes a destination for migrants

THE Suchiate river is the southernmost stretch of Mexico’s border with Guatemala. At Ciudad Hidalgo there are two ways to cross it. You can use the bridge, which guarantees an encounter with an immigration official. Or you can walk down to the river bank, hire a raft (planks tied to the inner tubes of two tractor wheels) and get yourself punted across. Many passengers are Guatemalans who want to shop in Ciudad Hidalgo, where goods are cheaper. The Mexican border guards ignore the flotilla below them and its duty-dodging cargoes; they bring the town a lot of business.

Such rafts are also popular with Central Americans heading farther north, to the United States. But their number has dropped in recent months, says Alexander, who has piloted a raft for four years. Occupancy at the Casa del Migrante in nearby Tapachula has fallen by more than a third since 2016, says Julver Gordillo, who works at the hostel. Immigration police are catching far fewer Central Americans without the right documents this year (see chart).

The deterrent is Donald Trump. His administration’s temporary ban on refugees, increase in the deportations of unlawful migrants and plans to build a border wall have put off would-be migrants. “He’s been good at scaring people,” says Gustavo Mohar, a former Mexican undersecretary for migration, population and religious affairs. Since Mr Trump took office arrests of migrants at the United States’ southern border, half of whom are Central Americans, have dropped dramatically.

But some people from Central America’s poor and violent “northern triangle”—El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras—dare not stay at home, regardless of the frosty reception that would await them in the United States. For some of those, Mexico is a destination rather than a corridor. Maria (not her real name), who is living at a migrant hostel in Mexico City, fled Guatemala with her two children early this year after her husband, who has gang connections, nearly killed her. He was sent to prison, but Maria fears he will carry out his threat to try again. She will not attempt to enter the United States. “As long as I feel safe we’ll stay here,” she says.

Central Americans are making that choice in growing numbers. To stay in Mexico legally, most have to apply for asylum. In the first six months of this year 7,000 migrants, almost all Central Americans, requested asylum. That compares with 9,000 for all of 2016. Liduvina Magarín, El Salvador’s deputy minister for Salvadoreans living abroad, says that around 90% of countrymen whom she met on a recent tour of Mexican migrant shelters were planning to request asylum there.

Mexico faces nothing like the influx that Europe has recently experienced. Germany, whose population and territory are much smaller, had 750,000 asylum requests in 2016. In theory, Mexico is just as welcoming. It grants asylum to people persecuted for their race, religion, nationality, gender, membership of a social group or political views. But it thinks of itself as a source of migrants rather than a magnet for them. So the rise in the number of refugees is causing consternation.

Typical of the river-crossers who now propose to stay in Mexico is “Carlos”, who fled Honduras after refusing to carry out a “mission” for a gang. He wants to find work in northern Mexico but has taken shelter in Tapachula while he awaits a decision on his asylum application. A decade ago such fugitives were almost all men, but as gangs increasingly threaten their enemies’ relatives, women and children have joined the exodus. Under Mexican law, a member of a family that has been threatened by a gang may qualify as belonging to a persecuted social group.

Mexico’s attractions include a shared language and communities of compatriots. Perhaps 300,000 Central Americans live in Mexico (compared with more than 3m in the United States). Mexico processes asylum requests much faster than the United States and Canada do.

But its welcome is cooler than that suggests. Speedy asylum decisions are not necessarily fair. “The government has prioritised detaining and deporting migrants as soon as possible—and is not ensuring they get properly screened,” says Maureen Meyer of the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), an NGO. In 2014 Mexico deported 77 out of every 100 unaccompanied children it caught; in the same year the United States sent back just three. Migrants encounter discrimination and are often robbed. Violence against migrants is “chronic” and is rarely punished, says a recent report by WOLA. According to some estimates, more than half of female migrants from Central America are victims of sexual assault.

The country has not always been hostile terrain for outsiders. In the mid-19th century it admitted thousands of fugitive slaves from the United States; under the constitution of the time they became free when they set foot on Mexican soil. From 1939 to 1942, when Britain and France turned away some refugees from Spain’s civil war, Mexico let 25,000 in. But by the 1970s the government, worried about unemployment, restricted entrance to “useful” migrants and made it a criminal offence both to enter and to stay in the country without authorisation. (In the United States, entering the country illegally is a crime but staying there is a civil offence.) In 2014, with encouragement and cash from the United States, Mexico stepped up its efforts to catch migrants headed north. Mexico deports children of migrants born in the country, in violation of its own laws, says Salva Lacruz of the Fray Matías de Córdova human-rights centre in Tapachula.

Under pressure from activists and from migrants themselves, Mexican attitudes are softening. The attorney-general’s office has established a unit to investigate crimes against migrants. The country’s president, Enrique Peña Nieto, has promised to promote refugees’ integration into society and to increase the staff of COMAR, the commission that is responsible for the welfare of asylum-seekers and rules on their applications. Entering and staying in the country without papers stopped being a crime in 2008. The success rate for asylum claims rose from 40% in 2014 to 63% last year.

Even with these improvements, the government pays too little heed to migrants’ rights, says Mr Lacruz. He says it should start by complying with its own laws, including the one allowing children born in the country to stay.

Mr Trump’s harder border, and the flow of refugees across Mexico’s southern one, will force the government to pay more attention to Central America. During Barack Obama’s presidency, the United States increased its spending on projects in the region that aim to reduce violence and improve job prospects, especially for young men. As Mr Trump turns his back on the United States’ southern neighbours, Mexico may become more active. Central America should be Mexico’s “top foreign-policy concern”, says Mr Mohar. That is unlikely to happen: the United States is plainly more important. But as rafts continue to cross the Suchiate river, the northern triangle and its woes will move up the diplomats’ agenda.

This article appeared in the The Americas section of the print edition under the headline "Fewer rivers to cross"

http://ift.tt/2h61daW

0 notes

Text

Smuggling in the Time of Coronavirus

In a break from the usual content of the daily White House press briefings on Covid-19, on April 1 U.S. defense secretary Mark Esper announced an increase in military assets assigned to U.S. Southern Command in an effort to stop illicit-drug traffickers from exploiting the ongoing crisis.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley offered a stark warning to the cartels: ‘You will not penetrate this country … You’re not going to come in here and kill additional Americans. And we will marshal whatever assets are required to prevent your entry into this country to kill Americans.’

It is unclear what intelligence prompted this response; however, it poses interesting questions about how drug cartels might seek to capitalize on the coronavirus pandemic. While any crisis that consumes national focus offers opportunities for organized crime, the unprecedented nature of this particular crisis means there’s no real historical reference point for dealing with the problem. It seems likely, though, that drug-trafficking organizations will face their fair share of challenges (as well as opportunities) as this pandemic unfolds.

Since the majority of illicit drugs enter the U.S. through recognized ports of entry, the reduced traffic between Mexico and the U.S. will force traffickers to use other, less efficient smuggling corridors. Competition for access to these corridors will undoubtedly lead to violence between cartels. We may already be seeing evidence of this playing out—Mexico had a record high of 2,585 homicides in March.

Global supply lines have been disrupted and early reports from eastern and southern Africa indicate an increase in heroin prices combined with a reduction in purity. There are also reports that the Sinaloa cartel is experiencing shortages in precursor agents—which generally come from China—for the production of methamphetamines and fentanyl.

An interruption to the supply of fentanyl is likely to be one positive for the U.S., which reported roughly 50,000 fatalities from opioid-involved overdoses in 2018.

On the demand side, reduced street traffic in cities with quarantine measures will put dealers and users under pressure in ways that may significantly alter traditional distribution methods. It’s also unclear if social isolation will result in a decline in recreational drug use. People with more serious addictions, however, will likely seek out alternatives such as prescription medications if the illicit-drug supply continues to be disrupted.

As British journalist and lecturer Ian Hamilton wrote recently, ‘People don’t behave rationally in these situations, whether it’s about the supply of toilet roll or cocaine.’

Like any business, drug cartels will look to innovate in order to survive. Whereas organized crime more broadly has seen an increase in cybercrime and the counterfeiting of medical equipment, drug cartels may simply leverage their expertise in human trafficking and extortion.

In any case, the new restrictions on movement across international borders will test even the most resilient trafficking networks. This provides unique opportunities for law enforcement, but also risks encounters with organizations that may be becoming increasingly desperate and violent.

In a bizarre demonstration of apparent social responsibility, drug gangs recently enforced curfews in parts of Brazil and El Salvador in the absence of government action to prevent the spread of the pandemic. Similar actions were seen in Venezuela by the group Colectivos, which is loyal to President Nicolas Maduro, who, coincidently, was recently indicted by the U.S. government on charges of ‘narco-terrorism’.

Drug cartels wielding state-like power isn’t a new phenomenon in Latin America, though its use in response to a pandemic certainly is. How well these organizations respond to the crisis will likely determine the level of ongoing support they get from the communities that ensure their survival.

In the U.S., the administration’s decision to increase the military and law enforcement presence near the southern border was probably a wise move that may already be paying off. If it is coordinated effectively, it could prove to be devastating for drug cartels that are likely to be under increased pressure to move whatever product they have available.

In more normal times, this would provide a unique opportunity for international cooperation against a common threat. But these are not normal times.

Gareth Rice is an officer in the Australian Army undertaking postgraduate research with UNSW Canberra. His views do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Australian Defence Force or the Australian government.

This article appears courtesy of The Strategist and may be found in its original form here.

from Storage Containers https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/smuggling-in-the-time-of-coronavirus

via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

Erratic Weather Patterns in the Central American Dry Corridor Leave 1.4 Million People in Urgent Need of Food Assistance

Erratic Weather Patterns in the Central American Dry Corridor Leave 1.4 Million People in Urgent Need of Food Assistance

Human Wrongs Watch

2.2 million people in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua have lost their crops due to rainfall and drought; 1.4 million urgently need food assistance

FAO and WFP are requesting US$72 million from the international community to provide food assistance to more than 700,000 people in the Dry Corridor. 25 April 2019, Panama City (FAO)* – The United Nations Food…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

http://sdg.iisd.org/news/range-states-launch-jaguar-conservation-roadmap/

20 November 2018: Fourteen jaguar range States and international conservation organizations launched the ‘Jaguar Conservation Roadmap for the Americas’ at the 14th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 14) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The Roadmap seeks to protect key jaguar corridors while also contributing to biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.

The jaguar ranges across 18 countries in Latin America. As a result of habitat loss and fragmentation, human-jaguar conflict and illegal poaching, 50 percent of the jaguar’s original range has been lost, and the jaguar is now extinct in El Salvador and Uruguay. According to the UN Development Programme (UNDP), successful jaguar conservation requires landscape planning and management in development and economic sectors, such as agriculture, forestry and infrastructure, to maintain biodiversity and connectivity. By conserving jaguars, conservation initiatives also maintain biodiversity, forests, carbon, watersheds and cultural and national heritage, and support achievement of the SDGs, the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets.

The Jaguar Conservation Roadmap represents the type of innovative partnership that is essential for achieving the SDGs.

The Jaguar Conservation Roadmap for the Americas aims to strengthen the Jaguar Corridor, which ranges from Argentina to Mexico, by securing 30 priority jaguar conservation landscapes by 2030. The regional initiative will strengthen international cooperation and raise awareness on jaguar protection initiatives, such as connecting and promoting jaguar habitats, mitigating human-jaguar conflict and promoting sustainable development opportunities that support the well-being of indigenous peoples and local communities. The initiative also seeks to raise awareness on the jaguar’s role as a keystone species whose presence is indicative of a healthy ecosystem. The Roadmap outlines four strategic conservation pathways: coordinating at a range level to support protection and connectivity; developing and implementing range countries’ strategies and improving contributions to transboundary efforts; scaling up conservation-compatible sustainable development models in jaguar corridors; and enhancing the financial sustainability of systems and actions to conserve jaguars and their ecosystems.

UNDP Head of Biodiversity and Ecosystems, Midori Paxton, said the Jaguar Conservation Roadmap “represents the type of innovative partnership that is essential for achieving the SDGs” and will help protect key jaguar corridors in ways that strengthen sustainable livelihoods for local communities and open up business opportunities for sustainable agriculture and ecotourism.

Also in support of jaguar conservation, the UNDP, Panthera, Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and government representatives announced the creation of the first-ever Jaguar Day to raise awareness about threats facing the jaguar and conservation efforts in support of the species. The Day will be celebrated annually on 29 November.

The Roadmap’s release comes after a UN high-level forum that resulted in the launch of the ‘Jaguar 2030 New York Statement’ by 14 jaguar range countries and international conservation organizations.

COP 14 is taking place in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, from 15-29 November. [UNDP Press Release] [IISD RS Coverage of UN Biodiversity Conference]

Some good news for jaguars!

0 notes

Text

No peace for Hondurans one year after post-election crackdown

The bullet hole in Junior Rivera’s neighbour’s garage door was just one of many in the Lopez Arellano sector of Choloma, in northwestern Honduras. Military police shot live ammunition during repeated crackdowns on local highway blockades by residents protesting what they called "election fraud".

"This is the sector that was the worst hit by the repression," Rivera, an opposition alliance political activist, told Al Jazeera.

On two early occasions, national civilian police force officers showed up to dialogue with Lopez Arellano residents blocking the highway, a critical commercial corridor running from San Pedro Sula, the country's second-largest city, to Puerto Cortes, the country's main port. Police and locals negotiated a compromise, leaving one lane open to traffic, but police soon stopped showing up to talk, Rivera said.

"After that, it was just the military police with tear gas and live bullets," he added.

Monday marks one year since the 2017 presidential elections in Honduras, and the ensuing political crisis continues, contributing to the mass exodus of thousands currently fleeing the country.

Preliminary election results showed opposition alliance presidential candidate Salvador Nasralla with a supposedly irreversible five-point lead. But after the election data transmission system crashed for hours and came back online, incumbent President Juan Orlando Hernandez quickly shot into the lead.

Hernandez and his predecessor from the ruling National Party, Porfirio Lobo, have been plagued by allegations of ties to organised crime and drug trafficking, and they both now have close relatives in custody in the United States.

On Friday, Juan Antonio Hernandez, a former congressman and the president's brother, was arrested at the Miami airport. He faces charges of conspiring to import cocaine to the US, as well as weapons charges. Last year, a US district court sentenced one of Lobo's sons to 24 years in prison for conspiring to import cocaine.

"In the case of the citizen Juan Antonio Hernandez, as in the case of any other Honduran, the President and his government maintain the position that every individual is responsible for their actions and that in no manner is that responsibility transferable to anyone else," the Office of the President said Friday in a statement.

Hernandez's candidacy for a second term was contentious from the start. The Honduran constitution has a strict ban on presidential re-election, but a Supreme Court ruling during Hernandez's first term in office gave him the green light to run.

Three political forces united in an effort to defeat Hernandez at the ballot box: the LIBRE party that grew out of opposition to a 2009 coup d'etat; Salvador Nasralla and his broad base of supporters backing his anti-corruption platform; and the small PINU party.

The sudden reversal of the preliminary election results sparked widespread condemnation, prompting calls for a total recount. The secretary-general of the Organisation of American States called for new elections.

Government crackdown

Highway blockades, city road barricades and marches broke out around the country. Hernandez enacted a state of exception, suspending several constitutional rights and freedoms, but it did not contain the outrage.

Military and police forces cracked down on protesters, sometimes firing live ammunition into crowds. Human rights organisations documented more than 35 killings, though some were reportedly extrajudicial executions of activists outside of the demonstrations.

International institutions concluded more than 20 protesters and bystanders were shot and killed during the crackdown on protests and highway blockades. The country's chief medical examiner confirmed that autopsies revealed bullets corresponding to state security forces in most of those killings.

Six Lopez Arellano residents were shot and killed in when security forces attacked local highway blockades in the month following the elections.

The government and military denied responsibility for any post-election killings. The government claimed the protests were infiltrated by gang members and financed by Venezuela, but presented no evidence to support the allegations.

Public prosecutors have initiated a few legal cases related to abuses by security forces following the elections, but there has been only one arrest for homicide in the context of election protests.

Al Jazeera first spoke with Rivera in his home in late December 2017. Port-bound semi-trailers sped past on the highway separated only by weeds and a ditch from the pot-holed gravel street in front of Rivera's house. Military police were stationed a few blocks away, at the main entrance to the Lopez Arellano Sector.

At the time, Rivera was the Choloma municipal coordinator of the opposition alliance, a member of the Cortes departmental opposition alliance coordinating body, and held a position in the Lopez Arellano Sector community council.

Rivera's gate and front door were damaged. Military police kicked the door in on December 12, 2017. They detained Rivera without telling him why or accusing him of any crime, and tried to take him away.

"They told me they were going to disappear me," Rivera said.

Word of the commotion military police were causing at Rivera's home had spread quickly. Rivera is widely known in the neighbourhood, not just as an opposition activist but also for his involvement in local matters, standing up for youths subject to arbitrary arrests and taking part in community battles against water pollution. A crowd began gathering to defend Rivera, and the military police were forced to let him go.

Hector Hernandez accompanied Rivera, his friend, during the interview with Al Jazeera last December. An energetic former police officer, Hernandez was an active participant in the local highway blockades and marches following the November 2017 elections.

Five weeks after the interview, on February 4, Hernandez was shot and killed in the street in broad daylight. No one has been arrested.

Forced to flee

Rivera was already spending the night elsewhere by late December, hoping it would become clear to security forces he did not sleep at home, so they would not show up at night and place his family in danger. The threats and attacks continued, though, and this past April, he fled with his wife and children to another part of Honduras. But Rivera kept getting word that military and police officers were looking for him.

Last month, Rivera left the country altogether. He joined thousands of Hondurans fleeing violence, poverty, and political persecution en masse in what was originally dubbed a caravan and has since renamed itself an exodus. Subsequent groups from Honduras and El Salvador, as well as individuals and groups from other countries, followed in their footsteps heading north through Guatemala and Mexico.

More than 5,000 Central American migrants and refugees are now in Tijuana, at the border with the US. They face overcrowding and underfunding at the local stadium that has become their shelter, and increasing border militarisation and US asylum restrictions.

Rivera is not with them. He is one of the more than 3,000 Central Americans from the exodus who chose to stay behind to request legal documentation when they entered Mexico. Many plan to seek asylum and work in Mexico, while others simply want a visa to legally transit through the country on their way to the US border.

They were all detained for two weeks upon entry, but are now scattered in shelters and crowded rented rooms around Tapachula, a city in the southern state of Chiapas. More than a month into the process of applying for refuge, they are not authorised to leave the state.

Every week, the thousands of refuge seekers line up to sign in both with Mexican immigration authorities and at the National Refugee Commission, which is coordinating with the Mexican office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Rivera is far from the Lopez Arellano Sector resident to flee Honduras. In an interview this weekend in Tapachula, he told Al Jazeera that more than 75 people from the Lopez Arellano Sector joined the exodus. Some continued on to Tijuana, but many stayed behind in Tapachula. Abuses by state security forces, gang violence, and extortion are among the main factors behind Lopez Arellano Sector residents deciding to flee.

Rivera is also not the only local resident to flee due to political persecution and threats. There is widespread support for the opposition alliance in northwestern Honduras, but in the Lopez Arellano Sector, the most active opposition alliance activists formed a collective. Of the 86 members of the collective, 44 fled the country last month, said Rivera.

"We just want somewhere we can be safe, and to be able to work to support ourselves and our families," he said.

Read the full article

0 notes