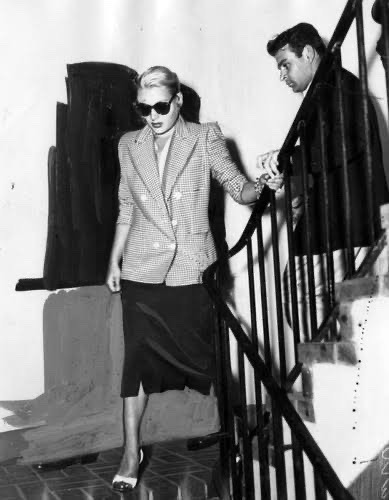

#Candid photo of my writers guild

Text

To my actor friends, here lies your future.

(New Yorker) Roles That You, a Digitally Scanned Background Actor, Will Soon Be Performing

By Nehemiah Markos and Jed Feiman, July 24, 2023

“They proposed that our background performers should be able to be scanned, get paid for one day’s pay, and the company should be able to own that scan, that likeness, for the rest of eternity, on any project they want, with no consent and no compensation.” —Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, SAG-AFTRA’s Chief Negotiator

Morning Commuter Heading to Soul-Crushing Job in Midtown

Hey, that’s your blurry face right behind digitally de-aged Tom Hanks in the opening credits of the newest chatbot-written Nora Ephron movie! And you never even had to show up to set wearing a polyester-blend suit on a ninety-degree summer day, and you never will again. Save that business attire for non-acting-related job interviews (which you’ll have to take a lot more of now).

Crowd Member in Musician Bio-pic

Remember when we scanned your fist moving from side-to-side? Well, get ready to wave your digitally-inserted lighter at standing-room arena concerts in perpetuity! We’re churning out bio-pics about every musical artist, problematic or not, that our record-label subsidiary has the rights to—coincidentally, also without those performers’ consent.

Expendable Soldier

We’re throwing you right onto the front lines of every war, real or imagined, that moviegoers will pay to see. Gruesomely die over and over and over again as you sacrifice yourself for the kingdom, republic, or our very own American plutocracy!

Cousin of Main Character in Framed Photos

Whether you sort of resemble John Boyega, Michelle Yeoh, or Richard Kind, our A.I. will replicate your smiling mug all over the protagonist’s home as proof that they come from a loving and facially similar family.

Driver Who Abandons Car and Runs for Dear Life When the Hulk Starts Throwing Shit

We’re almost done generating “Avengers Twenty-Eight: Part Seventeen,” and all the money that Disney saved by not paying hundreds of union actors in crowd scenes will help fund Bob Iger’s next helipad. Welcome to the new and artificially improved Marvel Cinematic Universe!

Enthusiastic DeSantis Supporter

Naturally, we’re licensing out our deepfake tech to politicians, too. Uncharismatic candidates who can’t even fill up an Iowa diner can now thank us for your support. As we like to say, “Your body, our choice!”

Racist Who Yells Epithets at Child on Way to Newly Desegregated School

You’re on the wrong side of history in every future Civil Rights-era movie that we hope will win us golden statues.

Believable Pervert in Police Lineup

Spoiler: your character didn’t actually do anything indecent, but your face is right next to the guy who did!

Nazi Who’s a Liiiiiiiitle Too Into It

Even the actor cast as Hitler was, like, “Whoa, buddy.”

Heroic and Lovable A.M.P.T.P. Member

We’re already developing a movie about the 2023 Hollywood strikes, because of course we are. No writers attached yet (they’re still picketing), but we do have a logline: the maligned, misunderstood, and conventionally attractive producers stand up to the greedy guild members who want to take unnecessary money away from billionaires for things like “food” and “shelter.” ChatGPT has already given it two (of your digitally scanned) thumbs up!

Villager with Pitchfork in Live-Action “Shrek” Remake

Get out of our studio, haha! Seriously, though. ♦

Photo: A scene from the movie Saving Private Ryan.

Photograph from DreamWorks / Alamy

#refrigerator magnet#new yorker#new yorker humor#for educational purposes only#actors#sag-aftra strike#strike#background actors

0 notes

Note

are you and your friends doing camp nano? I don't see many updates. when is you next chapters being posted?

I'll be honest and say that I've avoided answering this one because I've been getting a lot of messages lately about my "friends" that are more aggressive than I care to give attention to. I don't answer every anonymous message I get. If I start reading and the message sounds hurtful, I delete it. So if you are that person, then you finally win and I'm giving you the gratification of getting an answer. If you aren't that person, I'm sorry to suspect you of something like that. To be fair, the type and wording are very similar.

Yes, I'm doing camp NaNo. The people you refer to as my friends are really just online acquaintances who chat with me on occasion about the frustrations of writing. Yes, we get together often on various sites like CampNano or Habitica to motivate each other, but I wouldn't say that we were close enough to arrange visits to each others houses or vacation together or something. We're just writers helping each other out. Are we close? Sure, as guilds-people. Would I expect them to vote for me as president of the Rumbelle Club if there was one? No. At least, not if they thought someone else was more worthy. We're those kind of folks. Honest, hardworking, supportive, but not blindly so. There's a big difference between helping someone up when they're down and saying that same person is the perfect one for a job without giving consideration to any other candidate. That said, I don't think my actual friends would blindly do that for me either. At least, I hope not. I should think I have better taste in people I chose to spend time with than that kind of superficial behavior.

Anyway, point is, some of them are doing it too, at least from what I know. I haven't been online a lot due to a lot of stuff going on in my life at the moment. I'm actually very lucky to be writing this month at all.

So here's a glimpse into what I've been working on today for Camp Nano: It's the next chapter of Tent of Infinite Adventure. The Golds have just sailed a ship through a pitch black fog to end up in this land:

Photo by Jay on Unsplash

And the playlist I'm using for writing is this one, which isn't my own:

And the final words from today?

“Quiet,” commanded the population as a whole, whispering their order with little more than a breath. “This is the island of silence. You must obey or face the consequences of banishment.”

1 note

·

View note

Note

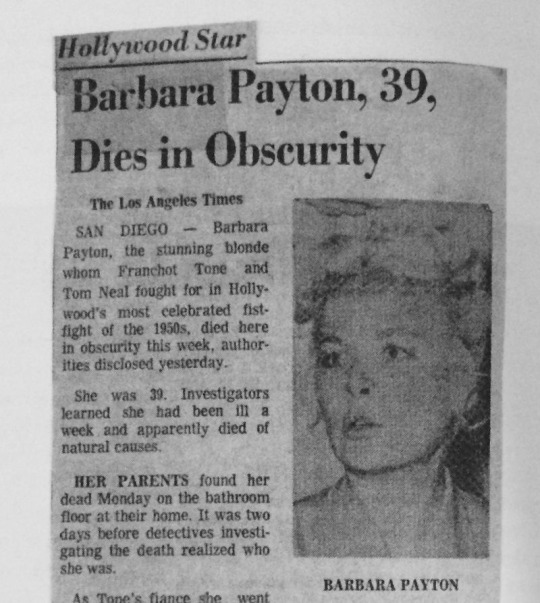

I just finished reading I am not ashamed after seeing your photo set about your favorite books about old Hollywood and I wanted to know what you think of it? I think it was interesting entertaining chaotic and funny but I feel so bad for Barbara because she was always so hopeful for the future

Omg I’m glad you read I Am Not Ashamed and liked it! I love Barbara Payton because she was so funny, honest and had a great sense of humour about herself, but at the same time she was self destructive to the point of annihilation. She always had this sense of glamour and strength you can see in candids when she’s in court for some bullshit

It’s still shocking to this day that she went from one of the top paid Hollywood starlets to resorting to dangerous street prostitution to support herself. I definitely think the sleazy journalist ghost writer Leo Guild exploited her story for money though bc Barbara didn’t get paid much despite revealing every personal aspect of her life. Like some of the passages from the book are insane:

“I’m 35 and beat up.”

“I had a body when I was a young kid that raised temperatures wherever I went. Today I have three long knife wounds on my solid frame. One extends from my buttocks down my thigh and needed I don’t remember how many stitches.” (She was stabbed while doing sex work!)

“I never go to movies and watch TV. I don’t even look in a mirror. I don’t want to see any pictures.”

I like the passages where she talks about finally being happy after finding love in Mexico, but then she leaves to go back and try to revive her career in Hollywood:

I honestly think L.A. destroyed her. The grimy, lurid lifestyle and drug and alcohol dependence there messed her up and caused her to die a tragic early death collapsing on the bathroom floor and fading away for good 💔

#I want to write about her on my blog but I left the book back home ahhh#Barbara Payton#old hollywood

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jill Fields, "Where my dreidel at?": Representing Jewish Identity in Orange Is the New Black, 13 J Jewish Identities 1 (2020)

The Netflix original series Orange Is the New Black ranks among the most watched shows available for streaming online or on cable. In June 2016, the first episode of Season 4 drew 6.7 million views in 72 hours, making it second in viewership only to HBO's popular Game of Thrones.1 It also garnered critical acclaim, receiving a Peabody Award in addition to many Golden Globe, Emmy, and Screen Actors Guild nominations and awards.2 The series is based on a memoir by Piper Kerman, who served thirteen months in a minimum security women's prison in Danbury, Connecticut after her conviction on a drug-related offense she had committed ten years earlier. Created by Jenji Kohan, the series is a "dramedy" that mixes comedic touches with poignant stories based upon Piper's prison experiences and those of others she lived with and worked alongside while incarcerated. When the series debuted in 2013, it was lauded for its diverse female cast—in terms of racial, ethnic, and sexual identities—and for its sympathetic depiction of the plight of the primarily poor women who serve time behind bars.3 Orange Is the New Black (OITNB) clearly broke new ground in representing women who are rarely seen in mainstream cultural texts, especially in prominent roles. Kohan revealed in an NPR interview that she used the character of the blonde Piper—whose last name was changed to Chapman in the show and who labels herself a WASP in both her memoir and on screen—as a "Trojan Horse" in order to sell the series to Netflix executives, who green-lighted a project that began with Chapman as the lead, but quickly evolved in an inclusive direction by elevating women of color to co-starring status.4

Academic assessment of OITNB has celebrated aspects of the series, but also critiqued ways in which the show upholds stereotypes about women of color, lesbians, transwomen, and older women, and how it draws upon women's prison film conventions that objectify incarcerated female bodies, albeit at times self-knowingly.5 Less noted thus far by scholars is the prominent attention the show gives to its Jewish characters and themes.6 Though the series deserves praise for shining light on diverse female experiences, its treatment of Jews draws upon long-standing tropes. The show deploys, for example, the classic construction of the interfaith relationship, seen for over a century in American culture; the enduring American television tradition of covert rather than openly Jewish identity; and reliance on the conversion narrative in portraying Jewish beliefs and rituals. These mechanisms highlight, yet also displace, the depiction of Jewishness on the series and the contributions of its Jewish creator, writers, directors, and actors.

Studies of Jewish representation in American popular culture have addressed both the presence and absence of Jewish characters and narratives. Documentation of the Jewish presence in film and television has produced assessments and generated debates about whether particular portrayals draw upon or challenge antisemitic tropes, provide realistic depictions of the Jewish-American experience, or sidestep considerations of what it means to be Jewish.7 Over time, and in tandem with emerging trends in feminist analysis and cultural studies, investigations of the representation of Jews in film and television began to also consider how particular narratives construct Jewish identity, especially in regard to gender, and explore contradictions embedded in mass cultural texts that reference Jewish experiences. Though ire, fear, outrage, and appreciation continue to motivate some research and give it urgency, analysis questioning assumptions about claims to authenticity, acknowledging diversity within Jewish communities, and drawing parallels in addition to contrasts with how a range of minorities are represented both in front of and behind the camera has provided new insights and opened up new ways of thinking about larger frameworks as well as specific texts. Nonetheless, asking whether products of the culture industry such as OITNB are "good for the Jews" remains relevant even when also taking into account a range of Jewish experiences and practices, the potential instability of identity formations, and possibilities for conflicting interpretations.

Important Jewish characters in OITNB include Piper Chapman's fiancé Larry Bloom, inmate Nicky Nichols—who I assert is a crypto-Jew through Season 5—and African-American inmate Cindy Hayes, who converts to Judaism in Season 3. It is significant as well that a number of actors, writers, and directors employed by the show in addition to series creator and producer Kohan are also Jewish. In what follows, I explore relevant aspects of the source material—Kerman's memoir—with a primary focus on how the fictional characters and their stories create Jewish moments in series episodes. I also suggest ways in which the representation of Jews connects with the show's Jewish cast and crew. Moreover, the contrast between the show's groundbreaking status and its employment of practices that date back to earlier periods in the history of television reveal the persistence of problematics for including fully realized Jews and their narratives on the small screen.

Larry Bloom, Masculinity, and Jewish Betrayal

Piper's Jewish fiancé Larry Bloom appears in the first episode of Season 1 and remains in the series through Season 2.8 The real Piper's real-life Jewish fiancé (now husband), who is a successful writer with the far less iconic Jewish last name of Smith, is in Kerman's memoir supportive and loving throughout Piper's prison ordeal, as are his equally wonderful parents. Larry Bloom of the series, an aspiring writer who struggles to get a paying gig, is initially kind and defends Piper to his awful Portnoyesque parents, who try to get him to dump his shiksa girlfriend. Larry has internalized his father's view of the blonde gentile woman as exotic and uses the term himself when proposing to Piper after she is sentenced. "Why would I want a felonious former Lesbian WASP shiksa who is about to go to prison to marry me? Why? Because this underachieving, underemployed Jewboy loves her."9 Larry Smith describes meeting Piper in similar terms: "Piper was pretty by anyone's standards, but blonde, blue-eyed, Waspy girls are catnip for hairy Jewish guys like myself." He further describes "classic Piper: steely and self-contained. I grew up with a different window into the world of women, one where they are a little neurotic and a lot needy."10 This well-worn construction of Jewish women has appeared in a range of media and texts, including interfaith marriage narratives depicted in such films as The Heartbreak Kid (1972) and Along Came Polly (2004), and in the 2015 comment by then-presidential candidate Donald Trump calling Congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz "crazy" and "highly neurotic."11 In OITNB, Larry further demonstrates his assimilationist impulse by preparing roasted pig for the couple's last meal together before Piper's self-surrender at Litchfield prison; their first snack in the prison visiting room is pork rinds.12

Larry is played by actor Jason Biggs, who has portrayed Jewish men in films such as American Pie (1999), though not Jewish himself.13 Soon after OITNB debuted, articles such as "Does Orange Is the New Black Have a Jewish Problem?" expressed concern about yet another iteration of Jewish masculinity as having "that tortured, brooding, nebbish quality we've come to associate with Woody Allen."14 Moreover, as other characters are humanized via flashbacks that reveal their difficult personal histories and draw viewers' sympathies, Larry's weaknesses become more apparent as the narrative unfolds and he draws viewers' disgust. A 2014 article, "A Guide to The Internet's Love of Hating Larry Bloom From 'Orange Is the New Black,'" concluded Larry was so detested he was the object of "world-class hatred."15

Larry's multiple betrayals of Piper propel his development into—or revelation as—a despised, nebbishy Judas. His first step down that path is watching episodes of Mad Men alone, after promising Piper he would wait to watch them with her after her release. To do so guilt-free, he turns over a framed photo of the two of them on his coffee table. As one critic called it, "Only a truly terrible human being would go against his loving girlfriend's wishes and watch their show without her. But turning the frame over? That's just cold-blooded."16 Larry's initial betrayal leads to more. When his only chance to get paid for writing an article requires detailing the prison experiences that Piper has shared with him in phone calls and visits, he goes ahead without her permission.17 She finds out about his New York Times "Modern Love" column from her prison counselor and, after viewers see Larry excitedly buying up copies of the newspaper, we find out that he has revealed information that endangers the tenuous relationships Piper has been building and needs to survive prison.18 In a subsequent episode, despite Piper's distress, Larry cozies up to an NPR reporter he meets at a Thanksgiving dinner, which results in a radio appearance sharing similar stories. Again, Piper only finds out about this after the fact, and listens in horror as Larry further humiliates both her and inmates she knows.19

The real Larry did write a "Modern Love" column about his relationship with an inmate, though it was published well after Piper's sentence ended, and a month before the 2010 publication of her memoir. Likely timed to promote Kerman's book prior to its release, the column most importantly does not betray her or her prison friends. Instead, Larry focuses on his devotion to Piper throughout her incarceration and the men he met who were also visiting their wives or girlfriends. The column ends with claims that his consistent visits and phone calls were not testaments to his character but instead prove how wonderful his fiancée is.20 In contrast, Netflix Larry's multiple betrayals reach their ultimate conclusion when he sleeps with Polly (Maria Dizzia), Piper's married best friend and business partner, and then dumps Piper for her. Larry and Polly even move in together and are shown enjoying their comfortable New York City lives as Larry and Piper used to do.21

Expressing dismay about how the show transformed Larry's character by drawing upon familiar tropes that denigrate Jewish men and Jews generally, and identifying differences between the two portrayals of Larry, is a fair, but ultimately narrow criticism. After all, adapting books into movies or television shows, whether fiction or non-fiction, requires alterations. The real Larry, for example, explains that translating Netflix Larry into what he calls a "schmuck" made the show more interesting.22 Another way to frame that transformation is to ask what purpose the nebbishy Judas/Jewdas performs in the OITNB narrative. I would argue that Larry's betrayal not only relieves the show from an unexciting story of a reliable boyfriend, but also displaces questions about possibly exploitative aspects of Kerman's best-seller and hit series onto the despicable and feminized Jewish man. This narrative turn burnishes the author's—and series creator Kohan's—celebratory claims to tell rather than sell the stories of incarcerated women who will not profit from their commercial dissemination.23

Kohan's OITNB cookbook, which features "Larry's Orange and Black Peppercorn Pulled Pork," is suggestive of her commercial goals and conflicted take on just how seriously the show and the discourse it has generated consider prison conditions.24 In addition, Kerman's former girlfriend, Cleary Wolters, who facilitated Kerman's criminal involvement in the drug trade, states in her memoir that she was never contacted by anyone connected with the book or the series prior to their release. In OITNB, her fictionalized character Alex Vause ends up in the same prison with Piper and their relationship is a central story line. When the Netflix series debuted, Wolters was out of prison and working and, though her employers knew the broad outlines of her criminal past, she had not shared details nor come out as gay at work when outed by the series. Wolters feared for her job security, aware of her tenuous status as an ex-felon. Within one day of the series release, the identity of the "real Alex Vause" was posted online, which caused her anxiety that former inmates might track her down. Ultimately, however, Wolters felt grateful that the success of OITNB allowed her to also share in print the sobering lessons of her criminal past and prison experiences.25 Nonetheless, the risks provoked by Wolters's inclusion in the memoir and series raise the question of exploitation, a charge against the show conceptualized as "trauma porn." Ashleigh Shackleford popularized the term in her assessment, shared by a number of African-American critics, that the show depicted "bleak narratives about the experience of people of color for the entertainment of those who have never lived those experiences."26 Such critiques provide further evidence for reading Larry's many betrayals as a displacement or hedge against similar charges directed toward Kerman or the series creators. As a long-standing trope, Jewish betrayal is easily identifiable and works to distract or absolve others of incriminating behavior.

The Jewish Inmate Problem: Levy

The treatment of a woman who, like Wolters, appears in the memoir but who has drawn less attention because she did not become an easily identifiable character in the show, provides an additional avenue for exploring Jewish identity in OITNB. Kerman's descriptions of Levy, a Jewish inmate, suggests the translation of Larry into a Judas can be indeed identified as a "Jewish problem," and one that originated in the memoir rather than the series. Consideration of the memoir is uncommon in studies of the series; Hilary Malatino's analysis is an important exception that provides a point of comparison below.27 A French Moroccan Jew, Levy is the only inmate whose behavior and demeanor Kerman derides repeatedly in her memoir. Levy is a true "other" in prison. As Kerman explains early on:

When a new person arrived their tribe—white, black, Latino, or the few and far between "others"—would … get them settled and steer them through their arrival. If you fall into that "other" category—Native American, Asian, Middle Eastern—then you got a patchwork welcome committee of … women from the dominant tribes.28

Levy thus falls outside or in between even the "other" category, but her status as a Member of the Tribe without a tribe and the impact her singularity might have had on her ability to in fact "get settled" is not considered by the otherwise compassionate Kerman. Described in the memoir as "tiny," Kerman scorns Levy for being "totally useless at electrical studies" despite "preening about her Sorbonne education."29 She is also criticized for her decision not to allow her children to come visit her because she does not "want them to see her in prison," despite Kerman noting without judgement others who "did not want their people to see them in a place like this."30 Kerman even positions Levy below guards in likeability: "'Zey have no class,'" sneered Levy. I didn't like prison guards, but she was insufferable."31 This excerpt is also an example of how Levy is singled out by Kerman, who reproduces her accent in the text to a greater degree than any other prisoner's. Levy is also ridiculed for crying more often than Kerman deems appropriate, though Kerman writes that when seeing an inmate cry after visiting hours are over, "you smiled sympathetically or touched their shoulder."32 Together, these comments justify Levy's status as:

the unifying factor in the [electrical] shop: the rest of us united against her. She was insufferable, crying daily and complaining loudly and constantly about her measly six-month sentence, asking inappropriate personal questions, trying to boss people around, and making appalling and loud statements about other prisoners' appearance and lack of education sophistication, or "class," as she put it. … Most of the time she was nervous-verging-on-hysterical, which manifested in dramatic physical symptoms; an astonishing hive-like swelling made her look like the Elephant Man, and her always sweating hands made her particularly useless for working with electricity.33

Though we do not learn the specifics regarding the cause of Levy's incarceration, Kerman mentions Levy was "whisked away to testify against her chiseler ex-boyfriend."34 However, the worst offense committed by Levy, according to Kerman, occurs after her release when she is interviewed by the Hartford Courant in September 2004, just before Martha Stewart's incarceration. Kerman reports the "Camp freaked out" that Barbara, as Levy is referred to in the newspaper article, describes the prison as a "big hotel" with "an ice machine, ironing boards," "two libraries" and "amazing food," and that she says she enjoyed not having to cook, clean, drive or buy gas. Kerman responded to the article in her memoir by "pictur[ing] Levy, swollen with hives, looking like the Elephant Man, crying every single day over her six-month sentence and sneering at anyone she thought was not 'classy.'" Though Kerman states the "reporter got many minor facts wrong," she and other inmates who "are outraged by the false claim that [they] could buy Haagen-Dazs ice cream" at the commissary blame Levy for the error. The prisoner in charge of the kitchen, Pop in the memoir and Red in the show, is upset and confused:

Piper, I just don't understand it. Why would she lie? You have the opportunity to get the truth out there about this place, and instead she makes up these lies? We have nothing here, and she makes it sound like a picnic.35

Kerman then explains to her readers that Levy lied because she "didn't want to admit to herself, let alone to the outside world, that she had been placed in a ghetto, just as ghetto as they had once had in Poland." Kerman here assumes that she understands the Jewish ghettos of World War II-era Poland better than Levy. She continues:

It was too painful … for Levy and others (especially the middle-class prisoners) to admit that they had been classed as undesirables, compelled against their will into containment, and forced into scarcity without even the dignity of chosen austerity. So instead, she said it was Club Fed.36

Kerman uses the ghetto metaphor to help her readers understand the "revolving door between our urban and rural ghettos and the formal ghetto of our prison system" in the United States and the difficulty of escaping either.37 However, Kerman, in collapsing distinctions, overlooks differences between Nazi ghettos and those she references, and also ways in which targeted communities form alliances based in shared histories of pain and oppression. Moreover, she does not consider the possibility if not probability that Levy has family members who perished, or who suffered and survived the Holocaust in France and Morocco. In a comparable critique, though one focusing on gender identity, Malatino finds Kerman "lacks a framework for understanding trans subjectivity," and uses "classic othering strategies … [that] serve to de-authenticate transfeminine gender expressions."38 Kerman similarly lacks intersectional frameworks that could account for Levy's status as both wielding middle-class privilege and experiencing her subjectivity as an isolated and vulnerable minority.

Lacking fuller consideration of Levy's multiple facets, Kerman also did not mention that Levy in the interview lauded her fellow prisoners as "classy" and defended them against charges that sexual assault was common. For Levy, "The worst part about being there was being counted. They count you like an animal." Whether intentional or not, her emphasis on this aspect of prison life being exceptionally difficult for her evokes the experiences of Jews in Nazi camps during the Holocaust, an allusion that escapes Kerman. The Courant also sympathetically reported Levy's decision not to see her children, which Levy states was the hardest part of her stay, and an effort to maintain her dignity.39

Levy indeed may have been annoying. But that alone does not explain why Kerman devotes so much attention to her. In assessing what work she performs in the narrative, I argue Levy serves several functions. First, she is a vehicle for the middle-class Kerman to distance herself from those of her own class and to legitimate her claim that she accepts her shared status with poor undesirables, which other middle-class women prisoners like Levy do not. Second, she confirms the view of Jewish women as needy and neurotic, a dominant caricature even promulgated by Kerman's real-life Jewish husband. Levy thus also is a vehicle Kerman uses to elide her possible association with reviled Jewish femininity via her relationship with a Jewish man. Third, Levy translates into Netflix Larry as they are both Judases who in self-interest betray the experiences of incarcerated women in mass media forums. Levy-Larry are categorically unable to truly understand who those women are or identify with them, unlike the transcendent Kerman. Thus Levy-Larry is the mechanism by which Kerman and by default Kohan distance themselves from assessments that they are profiting from the ordeals of women who do not have similar professional opportunities to do so.40 Moreover, the construction of the justifiably hated if not abject Jew that results from Levy's transgressive behavior and Larry's increasingly despicable acts creates more possibilities for the diverse female inmates to be viewed sympathetically by readers and viewers.

OITNB and Television's Crypto-Jews

The portrayal of Jewish identity on the television series OITNB contains further complexities, as Jewish elements beyond the Bloom stereotypes are depicted from its earliest episodes. A mechanism for simultaneously including and excluding Jews in television is the long-standing practice of the crypto-Jewish character. Leslie Fiedler first used the term in 1964 to describe the phenomenon of characters whose Jewish identity is hidden, like the original crypto-Jews, Spanish Jews forced to convert in 1492 whose Mexican and Mexican-American descendants maintained Jewish practices for centuries typically without knowing the origins of their family traditions.41 Fiedler deployed the term critically in analyzing Willy Loman in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman and other characters penned by mid-twentieth-century Jewish-American writers such as Paddy Chayefsky, Bernard Malamud, and Norman Mailer. Fielder deplored the effect of "characters who are in habit, speech, and condition typically Jewish American, but who are presented as something else—general American," as "pseudo-universalizing." As a result, "the works … lose authenticity and strength" and constitute a "failure to remember that the inhabitants of Dante's Hell or Joyce's Dublin are more universal as they are more Florentine or Irish."42

Jewish Studies media critics such as Jeffrey Shandler, David Zurawik, and Vincent Brooks found the crypto-Jew concept useful in describing television characters whose Jewish identity is ambiguous, hidden, or suppressed but hinted at through narrative gestures, personal qualities, or physical features and often by being played by a Jewish actor. These critics explain that the crypto-Jew phenomenon was born of concern largely on the part of Jewish television executives that shows that appeared "too Jewish" would not appeal to most Americans and would make them vulnerable to charges of Jewish control of the media. The practice emerged in television's "Golden Era," after the popular radio and then television show The Gold-bergs ended its twenty-six-year run in 1955. The Goldbergs depicted an observant Jewish family of modest means comprised of immigrant parents and America-born children living in New York City. Matriarch Molly Goldberg (Gertrude Berg) was a beloved mass culture icon known for her down-to-earth wisdom and endearing malapropisms. Despite its broad appeal—Berg won the first Emmy awarded for Best Actress in 1950—Jewish television moguls such as William Paley, who headed CBS, made it clear that no new shows with Jewish leading characters would be aired. This attitude has been attributed to television executives' fears that Jewish programming would bring unwanted attention and therefore problems to Jews working in the medium. Occasionally, Jewish characters appeared in Jewish-themed episodes of shows from westerns like Rawhide (1959–1965) and Bonanza (1959–1973) to procedurals such as The F.B.I (1965–1974). However, the maxim "write Yiddish, cast British" became the rule through the 1970s. It was implemented most famously in network discussions about what became The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961–1966). Created by Carl Reiner, who planned to star, the sitcom was based on his life as a television comedy writer and head of a Jewish family living in the suburbs. Innovative in depicting both its main character's home and work life, CBS agreed to put the show in the prime time schedule if Reiner, et al. would step aside for a "less ethnic" cast. The one exception in the final ensemble was supporting character Buddy Sorrel, played by Morey Amsterdam, though his Jewish identity was rarely referenced.43

In the 1970s, "write Yiddish, cast British" remained a guiding principle on network television, though popular shows such as Barney Miller (1974–1982) and Welcome Back Kotter (1975–1979) featured lead characters with familiar Jewish identifiers, such as their New York City origins and speech patterns, and who were played by Jewish actors. Nonetheless, such characters remained crypto-Jews, as story lines never referenced or confirmed their Jewish identity. Rhoda (1974–1978), a spin off from The Mary Tyler Moore Show starring the non-Jewish Valerie Harper as Mary's Jewish friend Rhoda Morgenstern, was an exception, a sitcom about a Jewish woman. Even after the late 1980s and 1990s saw the return of the Jewish female lead in The Nanny (1993–1999) and Will & Grace (1998–2006), and the Jewish leading man in dramas thirtysomething (1987–1991) and Northern Exposure (1990–1995), the crypto-Jew remained an important creature of network television. Crypto-Jews of this era include George Costanza, Kramer, and Elaine on Seinfeld (1989–1998) and Rachel Green, Monica Geller, and Ross Geller on Friends (1994–2004). In an echo of the decision to recast what became The Dick Van Dyke Show, NBC executives insisted the Seinfeld characters, who were created as Jews, not remain so. Only Jerry Seinfeld remained identifiably Jewish, which was unavoidable as his character was based on the already known Jewish comedian's real persona.44

Despite this decades-long context and an emerging self-referential and fearless Jewish sensibility in twentieth-first-century cable programming personified by Jon Stewart on The Daily Show, Larry David's Curb Your Enthusiasm, and Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson's Broad City, and by the Amazon series Transparent, celebrated as the "Jewiest show ever," all of which found broad audiences, Orange Is the New Black features crypto-Jews among its diverse cast.45 Jewish actors in the series in recurring roles that began in the first season include Yael Stone, Constance Shulman, Barbara Rosenblatt, and Natasha Lyonne. Constance Shulman's character Yoga Jones's potential identity as a crypto-Jew is tipped off in a visual cue. As the inmates prepare for the December holidays by decorating the prison, Jones tapes a two-dimensional dreidel decoration to the wall upside down. Whether this indicates ignorance or a sign of Jewish distress (or Jews in distress), like the meaning of flying the American flag upside down, it is significant that this moment precedes, and perhaps precipitates, the scene where Jones's back story is revealed in flashback. Though nothing in the character's background particularly suggests she is Jewish, that she becomes a Buddhist after her conviction for mistakenly shooting and killing a neighbor's child when protecting her remote marijuana crop might be, as so many American Buddhists are Jewish, they are known as "JuBus." Jones's story also evokes the television character Dharma Finkelstein of Dharma & Greg (1997–2002) whose father is a Jewish hippie and befuddled pothead.46

Drug offender Nicky Nichols is the most prominent and clearly identifiable crypto-Jew on OITNB throughout its first five seasons. Yet a case can be made as well for Yael Stone's Lorna Morello. Stone, for example, was originally considered for the part of Nicky Nichols, but instead was cast as the working-class Italian-American Lorna Morello. This cultural slippage between Italian Americans and Jewish Americans has been long noted. In 1964, for example, Leslie Fiedler cited Paddy Chayefsky's Italian American Marty as a Jewish American being "presented as something else."47 More recently, Dominique Ruggieri and Elizabeth Leebron in their research on Jewish- and Italian-American women on television conclude that ever since Mama Rosa debuted in 1950, shortly after the transition of The Goldbergs from radio to television, both Jewish- and Italian-American women have been portrayed as:

selfish, pushy, materialistic, domineering, manipulative, assertive, loud, shallow, whiny, demanding, man-hunting, weight-conscious, high-maintenance, shopping-crazed bargain hunters, possessive, controlling, unmarried, success-oriented, food-oriented, asexual, and unattractive. Physical qualities that epitomize these characters include large noses, big hair, a dark complexion and issues with their bodies. The positive characteristics linked to these ethnic portrayals include strong family orientation, loyalty, and devotion as mothers.48

In addition, several prominent Italian-American television characters, such as Dorothy Petrollo-Zbornak on The Golden Girls (1985–1992) and Marie Barone on Everybody Loves Raymond (1996–2005) were played by Jewish actors, Bea Arthur and Doris Roberts respectively. Some Jewish media journalists have gone a step further and declared the entire Barone family Jewish because the show's Jewish creator, Phil Rosenthal, infused the series with storylines based on his own family.49 Similarly, crypto-Jew Costanza from Seinfeld, who is ostensibly Italian American, is played by a Jewish actor, as are his parents. It works both ways; Italian-American actor John Turturro has played Jews in multiple films.50 Moreover, on OITNB, the connection between Nicky and Lorna is part of the narrative. In the first episode of Season 1, we are introduced to both characters along with Piper, who discovers them having sex in the shower. The amorous relationship between Nichols, who is a lesbian, and Morello, who identifies as heterosexual, continues through the fifth episode, when Morello breaks it off to save herself for her fiancé. Nonetheless, their relationship maintains an emotional and at times physical intimacy. Furthermore, Lorna later reveals her fiancé is Jewish, and decides, "If I marry him, I'll be Jewish too."51

On her own, drug offender Nicky Nichols personifies the typical television crypto-Jew. Natasha Lyonne neé Bronstein's thick, wavy long hair and New York accent are key physical markers. Nicky, an articulate, insightful, and wisecracking lesbian, was raised in Manhattan by her professional, well-to-do, divorced mother. Nicky complains about and blames her mother's absence in her life for some of the psychic distress that undergirds her addiction. Flashbacks depict their difficult relationship; however, as her back story progresses, we see Nicky is an incorrigible addict who uses her smarts and sarcasm to manipulate her mother, who eventually throws up her hands. Nicky's mother's characterization is not stable in the show and there is no evidence to suggest she is a crypto-Jew herself. For example, she is not played by a Jewish actor. Perhaps then it is Nicky's truly absent father who is Jewish. After all, her last name mirrors jokester Joey Nichols, who is Woody Allen/Alvy Singer's father's friend in Annie Hall. As Joey's cultural descendant, Nicky's comedic abilities are more fully evolved: in another marker of Jewish-American identity, she performs stand-up during the prison holiday talent show.52 Moreover, Lyonne makes her own Jewish identity clear in interviews and in the extra feature "Getting to Know the Cast" on the Season 3 DVD, where she talks about living in Israel in the 1980s, and provides the wittiest responses to many of the questions she and the other actors are asked. Nicky is also the first character to use Yiddish words in the series and the first to term a gang of white supremacist inmates as Nazis.53

In critical readings of the show, Nicky has been noted for her non-normative lesbian body, i.e., she is perceived as non-conforming to dominant standards of beauty. Such critiques either laud the show for depicting Nicky enjoying her sexuality despite not being thin and "attractive" or find fault in that the white lesbians with leading roles, Piper and her girlfriend Alex (Laura Prepon), uphold and thus perpetuate these oppressive standards.54 Furthermore Nicky's (crypto-Jewish) hair is unruly, and she does not attend fully to grooming and behavioral practices associated with femininity such as being neat, tidy, and controlled in appearance or speech. Nicky's presentation thus can be seen as conforming to the view of Jewish women as unattractive. Nonetheless, Kyra Hunting finds that:

often it is not Piper, marked by the politics of respectability who is the moral center for the group of white women but drug addict and promiscuous Nicky—whose appearance and lascivious language has rough edges but who consistently provides the most rational advice to other inmates.55

In addition, Nicky articulates incisive feminist critiques. For example, in regard to Lorna's obsession about her future marriage to her fiancé, Nicky comments on "the wedding industrial complex and society's bullshit need to infantilize grown women." Though Nicky demonstrates the benefits of her college education in such comments, she does not use her well-honed analytical skills to assert her superiority in the same manner as Piper's displays of knowledge sometimes do and for which other inmates call her out.56

Claiming Nicky as a crypto-Jew opens up further possibilities for considering her within the genealogy of "tough Jews," who defy stereotypes of Jews as weak, passive, victims or brainy yet nebbishy nerds. Scholars and commentators have deployed the term "tough Jew" to describe a range of real and representational Jewish men, from early twentieth-century Jewish-American gangsters Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel and Holocaust resistance fighters the Bielski Brothers, to the muscular Zionists and Israelis who forged a Jewish state and aim to protect the Jewish people. Nathan Abrams in The New Jew in Film extends the category to include the "tough Jewess with Attitude" seen in a number of turn-of-the-century films such as Miller's Crossing (1990), Homicide (1991), and Mr. & Mrs. Smith (2005). Though Nicky engages in illegal activity, she is not a gangster in the Lansky mold, nor is she a righteous member of anti-fascist resistance. Instead, her brand of Jewish toughness is born of her defiant lesbian identity, rough street life as a junkie, and willingness to speak her mind. These attributes are essential components of her prison survival skills.57

The tough Jew is posited by Abrams as a one-half of a binary paired with the queer Jewish male. In regard to Jewish women, he explains:

the tough Jewess with Attitude not only rebels against stereo(typical) gender roles, demonstrating that she can perform the same roles and tasks as the Jew, but also questions the duality of gender in the first place, confounding both the general and Jewish binary logic.58

As Nicky is queer and tough, she confounds stereotypes about Jewish women's representation on television, and, as I discuss further below, the representation of Jewish women in OITNB. Perhaps Nicky's status as a crypto—rather than "out" Jew—is thus overdetermined because not only does she defy categorization, she is categorically defiant. However, the popular cultural presence of well-known Jews with histories of substance abuse such as Lenny Bruce, Bob Dylan, Hillel Slovak, and Amy Winehouse—and that Natasha Lyonne's own struggles as an addict inform Nicky's narrative—raises additional questions about the reluctance or apparent impossibility of presenting Nicky as Jewish.59

Like many of the inmates, Nicky is not only tough. She displays vulnerability, particularly in her relationship with her prison mother Red (Kate Mulgrew). Yet even crypto-Jew Nicky engages in a Judas betrayal by sharing with a corrupt prison guard her prison mom's secret method of getting in additional culinary supplies. He plans to use the information to smuggle in drugs. This will lead to Nicky's downfall, as she later is found with drugs in her possession and, early in Season 3, gets sent to the nearby higher security prison. The dispatching of Nicky underscores the tenuous status of the television crypto-Jew, whose identity both articulates and avoids representations of Jewishness. Crypto-Jews provide gestures of Jewish representation, however reified—such as physical features, names, personal qualities, comedic sensibilities and intellectual insights—that convey a sense of Jewishness detached from historical contexts and specific experiences. Thus, a crypto character's Jewish attributes can be assigned or withdrawn at will, evading narrative demands for continuity or follow-through. The tattoo of a cross Nicky sports on the inside of her forearm, for example, thus neither confirms nor denies her Jewish identity. Instead it speaks to the shifting construction of the crypto-Jew as both trope and pastiche.60

"Where my dreidel at?" Kosher Food and Conversion Narratives

It is telling that it is only shortly after Nicky leaves, that the first "out" Jewish inmate shows up. Or at least, the first inmate who asks for a kosher meal. It turns out she is not Jewish, but requests kosher meals to get better food. This is a real phenomenon in US prisons. According to a 2012 Forward article, just one-sixth of the 24,000 prisoners receiving kosher meals in America are Jewish.61 On OITNB, the quality of the kosher meals is quickly noticed by other inmates, particularly Cindy (Adrienne C. Moore), who is among the first to request one. By the next episode several other African-American characters whose back stories have been previously highlighted are also eating kosher. However, it is Cindy who most embraces the potential of claiming Jewish identity. When she is accused of not being Jewish, she replies, "You think you know my life? Shabbat Shalom, bitch!" And as one Jewish popular press article on the topic notes, Cindy's "quest for edible food" leads her to other Jewish references, "including 'Shanah tova and hava nagila. It is good to be chosen.'" In response to someone asking if a seat is taken, she replies, "Yeah. We're saving it for Elijah." Cindy pursues her desire to learn more about Jewish culture by checking out Fiddler on the Roof and a Woody Allen movie from the library, which is humorous yet also a self-referential gesture to the importance of popular cultural texts in disseminating information about what it means to be Jewish.62

Up to this point in the series, Cindy's character has largely served as comic relief. She is depicted as a fool and an immature petty thief who is in prison because she abused her position as a TSA officer to steal passengers' belongings at the airport.63 When a rabbi is brought into the now privatized prison to determine if prisoners requesting kosher meals are motivated by "sincerely held beliefs"—an actual legal standard employed to determine the validity of prisoners' claims to kosher meals—his interviews are relayed in a montage of inmates sharing both goofy ideas about what it means to be Jewish and some well-worn stereotypes that are played for laughs: "I think y'all are doing a wonderful job controlling the media. I mean we. We are doing a wonderful job;" and "I call my mother a lot, like every day, and, love a bargain." When asked whether she was raised Jewish, Cindy claims she was "born and bred," and recounts plot points from Annie Hall and Yentl. This strategy fails to keep her on the kosher meal list and Cindy decides to convert, ending the episode with its title question, "Where my dreidel at?"64

In the next episode we discover there actually are Jewish women inmates held at Litchfield; Cindy has sought them out to prepare for her conversion. One is Ginsberg (Jamie Denbo), who sheepishly reveals she has been convicted for money laundering when asked. This is an odd exchange not only because it is rare for a prisoner to be asked that question by another inmate, especially when they have just met, but also because Ginsberg's gesture when revealing the basis for her conviction conveys shame at having been caught both in the crime itself and in a crime that evokes the antisemitic association of Jews with money. However, that same information reassures Cindy that Ginsberg is indeed Jewish, as she was skeptical due to Gins-berg's blonde hair and blue eyes. In the commentary on the episode by its credited writer, who describes herself as an Irish Catholic, she explains that Kohan rewrote Ginsberg's monologue describing the inmate's upbringing. Ginsberg's experiences thus appear grounded in those of Kohan's herself, as when Ginsberg demonstrates she knows her Jewish chops by talking about her bat mitzvah and her Hebrew name, Shayna Malka.65

In the last episode of Season 3, Cindy, with Ginsberg and another Jewish inmate, Rhea Boyle (Yelena Shmulenson) by her side, meets with the rabbi. Rhea opens the conversation: "Why you want to go from a hated minority to a double-hated minority is beyond me," before turning to the rabbi, and vouching for Cindy by asserting, "she's for real." Cindy has chosen the Hebrew name Tovah—"which means good and it's all good now"—and explains she has traded granola bars with Ginsberg and Boyle for Hebrew lessons. The rabbi then asks, "What is this for you?" Cindy's reply, written by Kohan, is conveyed in a truly moving performance by Moore.

Honestly, I think I found my people. I was raised in a church where I was told to believe and pray. And if I was bad, I'd go to Hell. If I was good, I'd go to Heaven. And if I asked Jesus, he'd forgive me and that was that. And here y'all saying there ain't no Hell. Ain't sure about Heaven, and if you do something wrong, you got to figure it out yourself. And as far as God's concerned, it's your job to keep asking questions and to keep learning and to keep arguing. It's like a verb. You do God. … I want to learn more and I think I got to be in it to do that. … Can I be a Jew?

Cindy is ecstatic when he and both witnesses say yes, until she finds out she must also experience ritual immersion in a mikvah to make her conversion official. Ginsberg consoles her by explaining that although she is not a Jew yet, she is "Jew-ish."66

A miracle ensues for all the inmates when the guards go on strike and a construction crew accidentally rips open a hole in the fence, allowing everyone to take a dip in the lake on the other side. Most prisoners run in to enjoy their momentary freedom. Cindy finds Ginsberg, who recites the blessing as Cindy immerses her naked body in the water. Conversion complete, Gins-berg congratulates her with a "mazel tov" and Cindy is all smiles in a closeup shot depicting her deep expression of her new found source of joy. Cindy's transformation during a season in which all sorts of religious identities and meanings are explored is remarkable for her as a character and also for the way it explains the meaning of Judaism, and most importantly, the difference of Judaism, which the show affirms and upholds. Furthermore, the sensitive treatment of her conversion story creates opportunities to depict Jewish community within the prison, and allusions to Jewish community outside it. In so doing OITNB incorporates significant Jewish content that a focus on individuals, especially when occurring in fleeting moments or signaled in quips, cannot accomplish alone. I would argue the brief depiction of Jewish community on the show reveals the fissures of representing Jewishness without that larger communal context, and the potential for greater narrative depth when included.

African Americans and Jews by Choice

Cindy's conversion is credible as a personal journey that concludes the series' prison kosher food narrative, and also because it resonates with the experiences of other well- and lesser-known African-American converts—whether real or imagined—to Judaism. These "Jews by Choice" join a diverse Jewish community: a 1990 study conducted by the Council of Jewish Federations concluded that in the United States 2.4 percent of "self-identified Jews list their race as black," and "about 100,000" additional African Americans "reported having 'connections' to Judaism." In addition, African-born Jews comprise 14.6 percent of Israel's Jewish population.67 Popular entertainer and Rat Pack member Sammy Davis, Jr. was the most well-known African-American Jew for many decades following his 1960 conversion, which occurred after years of study and consultation with Reform rabbis in Los Angeles and Las Vegas. He and his Swedish fiancée, actress May Britt, "formally converted a few weeks before their wedding."68 Other well-known African-American converts include writer Julius Lester, actress Nell Carter, writer Jamaica Kincaid, and rapper Shyne. Convert Alysa Stanton became the first African-American woman rabbi in 2009. She decided to convert when in her twenties, explaining her choice in similar terms voiced by the fictional Cindy, "For me, Judaism was where I found a home." After overcoming initial hesitancy upon her hiring, she ultimately led the Congregation Bayt Shalom in Greenville, North Carolina to great acclaim.69

Fictional African-American Jews have also previously appeared on television. In an episode of the 1970s situation comedy Sanford and Son entitled "Funny, You Don't Look It," patriarch Fred Sanford (Redd Foxx) is told by a genealogist that he is a descendant of Ethiopian Jews. His initial reaction trades in stereotypes in a similar vein to Litchfield inmates' attempts to assert a legitimate claim to their kosher meals, such as articulating his new-found desire for his son to become a doctor. However, like Cindy, Fred then explores more deeply the meaning and history of Judaism and its rituals. When it turns out he was misinformed about his Jewish roots, he celebrates what he learned and appreciates his Jewish teacher's perspective that "Jews and blacks … have a lot in common," hoping that "the similarities will bring us closer together."70

Sammy Davis, Jr.'s conversion was also motivated by sentiments about connections between the two minority groups, in addition to spiritual connections he felt after a 1954 car crash in which he lost one of his eyes. He had become familiar with Jewish teachings and practices after working closely with Jewish entertainers such as Eddie Cantor, whom Davis credited for giving him his first big break. Davis particularly admired and was inspired by the Jewish people's ability to survive adversity.

These are a swinging bunch of people. I mean I've heard of persecution, but what they went through is ridiculous! … They'd get kicked out of one place, so they'd just go on to the next one and keep swinging like they wanted to, believing in themselves and in their right to have rights, asking nothing but for people to leave 'em alone and get off their backs, and having the guts to fight to get themselves a little peace.71

Despite the lengthy period during which Davis considered conversion, when accomplished it was met with some skepticism and criticism. Ribbing from his Las Vegas Jewish comedian friends was to be expected, but he was also the object of charges from some African Americans that he converted to advance his career, and escape from his blackness. Such accusations may explain his 1980 statement in Ebony that "My people are my people and my religion is my religion. My people are first. I happen to be a Black Jew. I am Black first and the religion I have chosen is Judaism."72

African Americans who become or are born as Jews challenge static notions of black and Jewish identity. Popular cultural renditions can further evoke the fluid terms that construct identities generally. African-American inmate Cindy, in OITNB, seeks and finds a spiritual home by converting to Judaism. Moreover, African-American Jews, both real and imagined, create spaces for plural Jewish identities. Yet questions remain about the benefits, costs, and consequences of such transformations, and their meanings in cultural representations.

In Lovesong, Julius Lester's 1988 memoir, he explores his path to conversion and the many dimensions of his Jewish identity. In the book's preface Lester states, "I am no longer deceived by the black face which stars at me from the mirror. I am a Jew."73 This expression of tension between his identities as black and Jewish is articulated by other African-American converts as well. Assumptions when attending services at an unfamiliar congregation that one is a curious visitor and not Jewish, and accusations from African Americans that conversion to Judaism represents a desire to escape blackness and become white, are both common experiences of black Jews by Choice. However, among other diverse Jewish populations, African-American Jews open up conceptions of what an American Jew looks like and point to limitations regarding assumptions about Jews and whiteness. In OITNB, Cindy's character also points to more flexible understandings of Jewish-American identity. Cindy's turn to gospel music after an African-American inmate's death—"I may be a Jew now, but times like this call for some Black gospel no matter what"—is a tribute to the power of that musical form and an expression of her own dual moment when she articulates both her black and Jewish identities. Asserting Jewishness as American in this case is also related to African-American cultural expression. Moreover, as Terry Shoemaker points out, Cindy shows she "is capable of being both Jewish and African American."74

OITNB's deployment of an African-American character's conversion to Judaism to convey Jewish values and depict Jewish rituals without inclusion of a fully realized recurring Jewish-American character and community underscores the problematic representation of Jewish identity in American popular culture. Though Cindy in OITNB tells the visiting rabbi in Season 3 she has "found her people" when professing to the sincerity of her quest to become a Jew, Season 4 depicts her prison experience largely as before, living among and hanging out with her African-American friends, with sparse attention to her new found faith and its meaning for her. Despite her new mezuzah, the Jewish inmates who assisted her conversion have not become a part of her life and no longer appear on the show. Moreover, Cindy's Jewish identity flattens, expressed primarily by her and other inmates in articulations of stereotypical if not antisemitic Jewish avarice. Conflicts with Alison, a newly arrived African-American inmate who is Muslim, wears a hijab, and is assigned to the bunk next to Cindy's, lightly spoof tensions between the two groups, yet mostly at Cindy's expense. In one episode, Alison hopes to trade access to her contraband cell phone for some of Cindy's commissary-purchased tampons during a prison sanitary napkin shortage. When Alison references a Biblical admonition, "If there are poor among you, do not be selfish or greedy towards them" to make her case, Cindy rejects this view as Christian. In addition to demeaning Cindy by showing her to be ignorant of the shared basis of the Abrahamic religions, which Alison understands, the one-dimensional focus on stale jokes about Jewish greed that dominate Jewish references in Season 4 prevents Cindy from articulating deeply-held Jewish values—for example in this moment of potential tzedakah—as she had during the previous season's focus on her conversion.75 Thus, the show's sympathetic portrayal of Jewish faith, values, and identity is short-lived, and its reliance upon an African-American character who converts to convey the authenticity of the Jewish experience most fully proves unstable.

Despite their limitations, a century of cultural texts from The Jazz Singer to OITNB have served as vehicles for disseminating information via mass culture about Jewish practices, values, family life, and community concerns to gentile audiences. Such exposure serves an ongoing need, as African-American actress Yvonne Orji recently demonstrated when she said, "I know what Shabbat is by watching Curb Your Enthusiasm."76 Yet the apparent impossibility for OITNB, despite its well-deserved reputation for inclusivity, to incorporate a Jewish-American inmate, or an ongoing Jewish prison community, however small, for Cindy to continue to interact with, suggests Jewish television creators and writers are still struggling with a revised, contemporary version of the "write Yiddish, cast British" mandate. One expression of that dilemma occurs early in the series when a posted list of religious services is shown to include Catholic, Wiccan and Muslim, but omits a Jewish option.77

Nicky and Cindy: New Information and Missing Connections in Season 6

Six years into the series, Nicky's crypto-Jewish identity resolves via a flashback to her fraught bat mitzvah. Her parents are divorced, squabbling, and more concerned about superficial and materialist aspects of the event than their daughter's achievement. As the second pair of Jewish parents depicted on the show, they are far worse than Larry's, who, however misguided, at least cared about their son's well-being. The bat mitzvah plays out as a teenage revenge fantasy, as Nicky strays from her prepared Torah commentary to excoriate her parents in front of the congregation. Yet the additional details provided about Nicky's self-absorbed and neglectful parents, whose behavior has been referenced previously, though not as Jews, do not further humanize Nicky nor serve to explain in a compassionate manner her drug addiction and criminal behavior because her parents, like Larry's, are one-dimensional. As one reviewer assessed the season, "Nicky Nichol's bat mitzvah is a train wreck with some good laugh lines, but it does not feel like an indispensable part of this show." Rolling Stone's Season 6 review similarly found only one of the season's flashbacks—about two other characters—"worth the bother," and did not mention Nicky's at all.78

The bat mitzvah flashback comes after Nicky, who is facing significant additional prison time in the aftermath of a prison riot, has contacted her father for legal assistance, and he comes through. Themes of Jewish betrayal become central as he urges Nicky to betray Red—again—to save herself. She does, though Red in a Stella Dallas moment of maternal self-sacrifice grants her permission to do so.79 Moreover, Cindy faces a similar high-pressure situation. She contacts her conversion rabbi for legal assistance, which he facilitates. Here too, her lawyer advises her to betray her best friend.80 Though wracked with guilt—a "Jewish thing" another inmate explains—she does.81

Though Cindy asserts the primacy of her Jewish identity in this season by using her Hebrew name when she becomes co-host of a radio show within the prison, she must do so repeatedly to her gentile friends. Other audiences apparently also need convincing; it is interesting that in the closed captions for the show, she is always referred to as Cindy, not Tovah.82 Furthermore, though there are parallels to Nicky's and Tovah's story lines, they seem to exist, like these characters themselves, in separate worlds within the prison. They appear briefly together in a prison wedding scene, where Nicky has donned a yarmulke and prayer shawl to officiate, though the couple, Piper and Alex, are not Jewish and there is no Jewish content to the ceremony. The Jewish objects, which also include a chuppah, add an exotic vibe that liven up the dreary setting, but like Nicky and Tovah, do not connect in any meaningful way with their Jewish character, identity, or values. The cross tattoo on Nicky's forearm is prominently displayed in another indication of her continuing ambivalent status post bat mitzvah flashback. In a measure of the irrelevance of the Jewish components depicted at the wedding, many reviews of the episode do not mention them at all. Thus, the Jewish elements of this season's important final episode—that includes a classic TV series ratings magnet, a wedding—provide color or comic effect, detached from ritual and cultural significance.83

Conclusion

In OITNB's final, seventh season, Nicky retreats to her crypto-Jewish identity. Despite having a loving relationship with a lesbian Egyptian inmate held for an immigration violation, a seeming set up for jokes and storylines like those created for Alison and Cindy in Season 4, there is bupkis about Nicky's Jewishness in any of this season's episodes. In regard to Cindy, the brief references to her being Jewish in Season 7 are few and far between. Though her rabbi comes through for her again in writing an employment reference letter, which secures her a job, he is mentioned only in passing, and Cindy is never depicted interacting with other Jews. These retrenchments once again point to the instability of the crypto-Jew and convert in reliably relating Jewish identity, practices, and sensibilities in television narratives. Erasure and marginalization of Jewish perspectives also appear to be facilitated by the absence of depictions of Jewish community.

Over its seven seasons, OITNB's shifting representations of Jewish identity move from the Bloom stereotypes and crypto-Jew Nicky Nichols, to the inclusion of Ashkenazi Jews in minor supporting roles that are essential in supporting the conversion of higher profile character Cindy. In Season 4, the reversion to stereotypes about Jews accompanies the return of crypto-Jew Nicky, who has been transferred back from a higher security prison. Perhaps the series' success in featuring the stories of women of color, lesbians, and transwomen, and in building a fan base for its diverse cast, created the possibility for the open exploration of what it means to be a Jew, if only temporarily. Nonetheless the instability of Jewish identity in the show may suggest tensions and uncertainties surrounding the relationship of Jewish subjectivity to those more clearly understood as marginalized. Thus it is significant that the character with the most screen time who voices the most endearing and sympathetic Jewish perspective is a convert who expresses her Jewish identity through the lens of her experience as an African American. When Nicky is revealed to be Jewish in Season 6, it makes little difference, as her Jewish identity and that of Cindy/Tovah's typically find expression only in passing verbal quips or visual jokes. These indications are underscored in Season 7, the series' last, in which the Jewish identities of these characters are rarely referenced or elided completely. Like other television shows that only explore Jewish identity in the apparently safer context of interfaith marriages and relationships, Jewish identity in OITNB is most fully realized when linked with someone who is not, at least initially, Jewish, and whose struggles as an incarcerated African-American woman have been depicted previously in the series, though no Jewish inmate's story receives similar treatment. Moreover, the troubling treatment of Levy in Kerman's memoir finds an echo in references to Jewish identity on the series that mine well-worn stereotypes without addressing the consequences, for example, of antisemitism in similar ways that the series addresses racism and homophobia. Yet importantly, Cindy converts and becomes a Jew who is accepted by the Jewish inmates who supported her religious transformation and by the rabbi who authorized it. Her conversion narrative provides opportunities for compassionate expression of Jewish values, conveys information about Jewish rituals, and challenges static notions of Jewish identity.

Though OITNB incorporates if not champions the experiences and perspectives of a range of minority groups, portrays incarcerated women sympathetically, and aims to critically depict the prison-industrial complex, and deserves praise for doing so, the significant Jewish presence on OITNB still bears consideration as simultaneous displacement through deployment of familiar stereotypes, crypto-identities, and conversion narratives. As Malatino also finds in regard to trans issues, "the show subverts certain tropes," yet also relies on "stereotypes."84 Cindy's struggles to be recognized as Tovah are emblematic and suggest that a Jewish problem—the problem of Jewish representation—remains a forceful shaper of narratives and character development on episodic television and streaming series.

Notes

Michael O'Connell, "Nielsen Says 6.7M Watched Orange Is the New Black Premiere in 3 Days," Hollywood Reporter, June 29, 2016, http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/orange-is-new-black-ratings-907390; Daniel Holloway, "TV Ratings: Orange Is the New Black Premiere Numbers Revealed by Nielsen," Variety, June 29, 2016, http://variety.com/2016/tv/ratings/tv-ratings-orange-is-the-new-black-premiere-nielsen-1201805991/, accessed December 4, 2016. OITNB is the "most-watched show" on the streaming platform according to Netflix executive Ted Sarandos. Dana Birnbaum, "'Orange Is the New Black': Jenji Kohan, Cast Talks Season 4, Diversity, Binge-Watching," Variety, January 17, 2016, http://variety.com/2016/tv/news/orange-is-thenew-black-season-4-jenji-kohan-1201681782/, cited by Sarah Artt and Anne Schwan, "Screening Women's Imprisonment: Agency and Exploitation in Orange Is the New Black," Television & New Media 17:6 (September 2016): 468.

Suzanne Enck and Megan Morrissey, "If Orange Is the New Black, I Must be Color Blind: Comic Framings of Post-Racism in the Prison-Industrial Complex," Critical Studies in Media Communication 32:5 (October 2015): 303. Piper Kerman, Orange Is the New Black (New York: Random House, 2010). See also Internet Movie Data Base, which notes over 250,00 reviews and an overall viewer rating of 8.1, www.imdb.com, accessed March 14, 2019.

Numerous articles laud the show's diverse cast, even those finding fault with how specific individuals and groups are represented. See for example, Roxanne Gay, "The Bar for TV Diversity Is Way Too Low," Salon, August 22, 2013. Gay notes, "You can't blink without someone celebrating the show's diversity," accessed March 10, 2019, https://www.salon.com/2013/08/22/the_bar_for_tv_diversity_is_way_too_low/.

“Orange Creator Jenji Kohan: Piper Was My Trojan Horse," Fresh Air, National Public Radio, August 13, 2013, accessed December 4, 2016, http://www.npr.org/2013/08/13/211639989/orange-creator-jenji-kohan-piper-was-my-trojan-horse. See also Jason Demers, "Is a Trojan Horse an Empty Signifier? The Televisual Politics of Orange Is the New Black," Canadian Review of American Studies/Revue Canadienne d'Études Américaines 47:3 (2017).

For essay collections with a range of perspectives on the series and how it represents particular groups, see Shirley A. Jackson and Laurie L. Gordy, eds., Caged Women: Incarceration, Representation and Media (New York: Routledge, 2018); April Householder and Adrienne Trier-Bieniek, eds., Feminist Perspective on Orange Is the New Black (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2016), and Television & New Media 17:6 (September 2016), special issue, ed. Sarah Artt and Anne Schwan.

Analysis of religion on the show that discuss Jewish themes include Terry Shoemaker, "Escaping Our Shitty Reality: Counterpublics, Orange Is the New Black, and Religion," Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 29.3 (Fall 2017): 217–229, and Terri Toles Patkin, "Broccoli, Love, and the Holy Toast: Cultural Depictions of Religion in Orange Is the New Black," in Shirley A. Jackson and Laurie L. Gordy, eds., Caged Women: Incarceration, Representation and Media (New York: Routledge, 2018), 227–238.

Foundational texts in Jewish television studies include Jonathan and Judith Pearl, The Chosen Image: Television's Portrayal of Jewish Themes and Characters (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1999); Vincent Brook, Something Ain't Kosher Here: The Rise of the "Jewish" Sitcom (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2003); David Zurawik, The Jews of Prime Time (Hanover: Brandeis University Press, 2003). For a critical assessment of the field, see Michele Byers and Rosalin Krieger, "Beyond Binaries and Condemnation: Opening New Theoretical Spaces in Jewish Television Studies," Culture, Theory & Critique 46:2 (2015): 131–145. Some studies incorporate consideration of both television and film. See for example, J. Hoberman and Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003); Paul Buhle, ed., Jews and American Popular Culture, vol. 1 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2007); Joshua Louis Moss, Why Harry Met Sally: Subversive Jewishness, Anglo-Christian Power, and the Rhetoric of Modern Love (Austin: University of Texas, 2017); Michael Renov and Vincent Brook, eds., From Shtetl to Stardom: Jews and Hollywood (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2017).

OITNB, www.imdb.com

"I Wasn't Ready," OITNB season 1, episode 1, Netflix, July 11, 2013. Piper tells Larry not to inform his father about her predicament because "he already hates me."

Larry Smith, "My Life with Piper: From Big House to Small Screen: The Other True Story Behind Orange Is the New Black," Medium, July 14, 2014, accessed December 4, 2016, https://medium.com/matter/my-life-with-piper-from-big-house-to-small-screen-592b35f5af94#.t5josbg1p.

Jeremy Diamond, "Trump: DNC Chairwoman 'Crazy' 'Neurotic Woman,'" CNN, November 2, 2015, https://www.cnn.com/2015/11/02/politics/donald-trump-debbie-wasserman-schultz-crazy-neurotic-woman/index.html; Miriam Levine, "Am I That 'Crazy Neurotic' Jewish Woman Donald Trump Is Describing?" Forward, November 3, 2015, accessed December 4, 2016, http://forward.com/sisterhood/323877/the-crazy-neurotic-jewish-woman/

"I Wasn't Ready," OITNB season 1, episode 1.

13. Biggs also portrayed American Pie character Jim Levenstein in American Pie 2 (2001), American Wedding (2003), and American Reunion (2012).

Sigal Samuel, "Does Orange Is the New Black Have a Jewish Problem?" The Daily Beast, July 18, 2013, accessed December 4, 2016 http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/07/18/does-orange-is-the-new-black-have-a-jewish-problem.html.

Ashley Burns, "A Guide to the Internet's Love of Hating Larry Bloom from Orange Is the New Black," Uproxx, June 30, 2014, accessed December 4, 2016 http://uproxx.com/tv/aguide-to-the-internets-love-of-hating-larry-bloom-from-orange-is-the-new-black/3/.

Ibid. See also Kimberly Potts, "Orange Is the New Black: You're Not the Only One Who's Not on Team Larry," Yahoo TV, June 20, 2014, accessed December 15, 2016, https://www.yahoo.com/tv/orange-is-the-new-black-youre-not-the-only-one-96478890565.html.

"WAC Pack," OITNB season 1, episode 6, Netflix, July 11, 2013; "Blood Donut," OITNB season 1, episode 7, Netflix, July 11, 2013.

"Moscow Mule," OITNB season 1, episode 8, Netflix, July 11, 2013.

"F … sgiving," OITNB season 1, episode 9, Netflix, July 11, 2013; "Bora, Bora, Bora," OIT NB season 1, episode 10, Netflix, July 11, 2013; "Tall Men with Feelings," OITNB season 1, episode 11, Netflix, July 11, 2013.

Larry Smith, "A Life to Live This Side of the Bars," New York Times, March 28, 2010, accessed December 4, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/28/fashion/28Love.html. He wrote an earlier "Modern Love" column about proposing to marry Piper that did not mention her recent prison experience. Larry Smith, "Hear that Wedding March Often Enough You Fall in Step," New York Times, December 26, 2004.

"Comic Sans," OITNB season 2, episode 7, Netflix, June 6, 2014; "Take a Break from Your Values," OITNB season 2, episode 11, Netflix, June 6, 2014.

Smith, "My Life with Piper."

See for example Yasmin Nair, who states, "White women like Kerman leave prison with book contracts, while others keep moving through its doors, fodder for the expanding Prison Industrial Complex." Idem, "White Chicks Behind Bars," In These Times, July 18, 2013, accessed March 10, 2019, http://inthesetimes.com/article/15311/white_chick_behind_bars/. The term "trauma porn" emerged to signal concerns about the show's exploitative aspects. Ashleigh Shackelford, "Orange Is the New Black Is Trauma Porn Written for White People," June 20, 2016, accessed March 10, 2019, https://wearyourvoicemag.com/culture/orange-is-the-new-black-trauma-porn-written-white-people.

Jenji Kohan, Tara Hermann, Hartley Voss, and Alex Regnery, Orange Is the New Black Presents: The Cookbook (New York: Abrams Image, 2014).

Cleary Wolters, Out of Orange: A Memoir (New York: Harper Collins, 2015), 4–8, 300–303.

Shackelford, "Trauma Porn;" Keah Brown, "Season Four of Orange Is the New Black Has a Race Problem," June 30, 2016, accessed May 14, 2019, https://medium.com/the-establishment/season-four-of-orange-is-the-new-black-has-a-race-problem-159a999dc66c.

Hilary Malatino, "The Transgender Tipping Point: The Social Death of Sophia Burset," in April Householder and Adrienne Trier-Bieniek, eds., Feminist Perspective on Orange Is the New Black (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2016), 95–110.

Kerman, Orange Is the New Black, 49; see also "WAC Pack," OITNB season 1, episode 6.

Kerman, Orange Is the New Black, 90.

Ibid., 91, 111.

Ibid., 94

Ibid., 114.

Ibid., 97.

Ibid., 199.

Ibid., 200.

Ibid., 200–201.