#Bulmer Hobson

Text

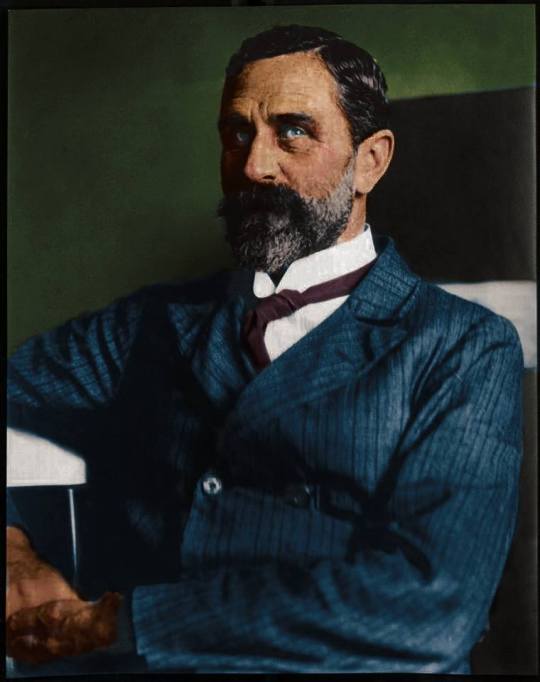

Roger Casement | A Man of Mystery

In the week after Roger Casement’s execution, on 3 August 1916, newsreel footage of the nationalist leader was shown in cinemas across America. At a conservative estimate, some 15 million US citizens saw the moving pictures. A century on, this fragment of film provides a fascinating insight.

Casement is glimpsed at his desk writing: The daily activity he performed above any other. He used the pen…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Alice Milligan#Alice Stopford Green#Angus Mitchell#Antrim#Banna Strand#British Foreign Office#Bulmer Hobson#Clan Na Gael#Co. Kerry#Congo#Congo Free State#Dublin#England#Eoin MacNeill#Germany#IRB#Ireland#Irish Brigade#Mario Vargas Llosa#Peru#Roger Casement#The Dream of the Celt

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Facts about Patrick Pearse?

Pearse’s maternal grandfather Patrick was a supporter of the 1848 Young Ireland movement and was sworn into the IRB.

Pearse’s maternal grand uncle, James Savage fought in the American Civil War [x].

The Irish-speaking influence of Pearse’s great-aunt Margaret, with his schooling at Westland Row, instilled in him with love for the Irish language.

Pearse recalled at the age of ten he prayed to God promising him he would dedicate his life to Irish freedom [x].

Pearse’s early heroes were ancient Gaelic folk heroes such as Cuchulainn, however, in his 30s he took interest in leaders of past republican movements, such as the Theobald Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet.

In 1900, Pearse was awarded a B.A. in Modern Languages (Irish, English and French) by the Royal University of Ireland, for which he had studied for two years and for one at University College Dublin. Pearse was called to the bar in 1901.

In 1905, Pearse represented Neil McBride who had been fined for having his name displayed in “illegible” writing (Irish) on his donkey cart. The appeal was heard before the Court of King’s Bench in Dublin. It was Pearse’s first and only court appearance as a barrister. The case was lost but it became a symbol of the struggle for Irish independence [x] [x] [x].

He started his own bilingual school for boys, St. Enda’s School. The pupils were taught in both Irish and English [x].

February 1914, he went on a fund-raising trip to the United States, where he met John Devoy and Joseph McGarrity both were impressed and supported him in raising money.

December 1913 Bulmer Hobson swore Pearse into the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), an organisation dedicated to the overthrow of British rule in Ireland [x].

He was soon co-opted onto the IRB’s Supreme Council by Tom Clarke [x].

Pearse was one of many who were members of the IRB and the Volunteers. He became the Volunteers’ Director of Military Organisation in 1914 and was the highest ranking Volunteer in the IRB membership.

1915 he was on the IRB’s Supreme Council, and its secret Military Council, a group that began planning for a rising while World War I raged on the European Western Front.

He was the first republican to be filmed giving an oration [x].

When the Easter Rising began Easter Monday, April 24th 1916, it was Pearse who read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic from outside the General Post Office, the headquarters of the Rising. Pearse was the person most responsible for drafting the Proclamation, and he was chosen as President of the Republic.

After six days of fighting, heavy civilian casualties and great destruction of property, Pearse issued the order to surrender.

Pearse and fifteen other leaders, including his brother Willie, were court-martialled and executed by firing squad.

Thomas Clarke, Thomas MacDonagh and Pearse himself were the first of the rebels to be executed, on the morning of May 2rd 1916.

Pearse was 36 years old at the time of his death.

According to eyewitness, after saying a tearful goodbye, he was whistling as he came out of his cell [x].

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

That Girl from Liberty Hall

Helena Molony, actress and activist, was caught up in the nationalist, feminist and trade unionist movements surrounding the fin de siècle. She was involved in many of the pivotal events of the early 20th century, such as the 1913 Dublin Lockout and the 1916 Easter Rising. Molony was engaged in the Irish-Ireland cultural movement and was active in the Abbey Theatre. She was secretary to the Irish Women Workers Union (IWWU) and continued to contribute to trade unionism after the Rising. Molony was born in 1883 to grocer Michael Moloney and Catherine McGrath.[1] Both parents died when she was young, leaving Helena and her brother Frank in the care of their stepmother with whom she had a strained relationship.[2] She was born into an Ireland where women were required to fulfil a restricted gender role, one that was focused within the domestic sphere. However, being orphaned meant she was unfettered from the usual filial expectations, which limited women in the early 20th century.

Molony recalls experiencing a ‘political awakening;’ in August 1903 she was motivated by a speech by Maud Gonne opposing the royal visit. Gonne embodied the spirit of Ireland that Molony envisioned, as Gonne ‘electrified (her) and filled (her) with some of her own spirit.’[3] This combined with her brother’s encouragement gave her the impetus to join Inghinidhe na hÉireann.[4] The evening Molony entered the organisation; she was caught up in a confrontation between the police and Inghinidhe at Gonne’s home, in the ‘Battle of Coulson Lane’.[5] Gonne, instead of a Union Jack, displayed a black cloth in the window; an apparent display of mourning at the passing Pope XIII but evidently it was to demonstrate against the visit of King Edward VII.[6] Despite initial reservations of Molony’s intention given the circumstances,[7] she was accepted into the organisation and assumed the Gaelic name ‘Emer’ as a pseudonym.[8] This renaming to the wife of the mythical Cú Chulainn would have a symbolic importance, as Molony began this new chapter of her life.[9] Inghinidhe na hÉireann was set up in 1900, developed from resistance to Queen Victoria’s visit to Ireland.[10] The organisation was established with aim to ‘opposing any expression of […] loyal flunkeyism’[11] and promote various forms of Gaelic culture; art, history, language, literature and music through offering classes for women and children.[12] The organisation also supported Irish made products; Molony devised a new strategy for promotion of Irish goods, which proved to be successful and demonstrated women’s buying power.[13] Inghinidhe appealed for school dinners, stood for anti-recruitment and discouraged romantic associations with British soldiers.[14] As Matthews notes, contrary to Molony’s view, it seems that many involved in dissuading young women from interacting with the soldiers campaigned on moral and social grounds rather than political.[15] The organisation illegally distributed of anti-recruitment pamphlets and posters. Molony was audacious in her propagation of seditious material directly targeting the authorities, Sidney Czira recollects Molony depositing handbills on a police sergeant’s back after a altercation and on the Lord Lieutenant’s car.[16] While the movement addressed worthy causes, it did not shatter the glass ceiling, operating within the socially accepted gender confines concerning mainly domestic issues and philanthropy. Molony directed the organisation after Gonne’s departure, liaising with her from France and she became Inghinidhe’s secretary in 1907.

Molony with Maud Gonne later in her life

Molony came to be the editor for the organisation’s new monthly newspaper Bean na hÉireann in 1908, describing it as a combination of ‘guns and chiffon.’[17] The journal was used not only used to disseminate nationalist propaganda, but also to review international politics and domiciliary subjects. Griffith disagreed with militarism and Inghinidhe’s anti-recruitment methods.[18] The paper was a counter to the discourse of his papers Sinn Féin and the United Irishman. Molony considered them to be ‘Anglicised’ in their moderation,[19] instead endorsing ‘militancy, separatism and feminism.’[20] Bean na hÉireann articles such as ‘The Art of Street Fighting’ and ‘Physical Force,’ combined with those in support of international insurrections can be seen as advocating the use of violence in the pursuit of the nationalist cause.[21] In order to provoke discussion, articles were published from leading Irish nationalists from the diverse nationalist ideological divides, Casement, Connolly, Griffith, Hobson, MacDonagh, Markievicz and Pearse.[22] The paper was a platform for ideological debate to play out, for example discussions on militarism versus pacifism and nationalism versus suffragism. In the November 1909 article ‘Sinn Féin and Irishwomen,’ Hanna Sheehy Skeffington prioritised the pursuit of the women’s vote over independence, contrary to Inghinidhe’s principles.[23] Hanna argued that national freedom would not alter the Irish societal frameworks, which were enslaving and pigeonholing women. A ‘Sinn Féiner’ responded to this reasoning by claiming women’s suffrage is inconsequential when deprived of independence.[24] Molony re-affirms this stance in an earlier issue, ‘if the English Parliamentary vote is not, in itself a source of power, then we should not stultify ourselves by wasting time and energy agitating for it.’[25] The journal published articles in support of the efforts made by British and Irish suffragists but Molony considered nationalism as the primary issue.

Molony introduced Countess Markievicz to the movement through participation in Bean na hÉireann.[26] The two women encountered each other at a Gaelic League meeting and became acquainted through their involvement in the Theatre of Ireland.[27] Constance Markievicz, along with her husband were involved in financing the Independent Dramatic Company.[28] Mary Quinn, who was then secretary to Inghinidhe, initiated Molony into theatre scene and was instructed in acting by the thespian Dudley Diggs.[29] This training would later serve her in her stage career but also her revolutionary activities. Through Markievicz, Molony became involved in the scouting organisation, Na Fianna Éireann, which had been founded in conjunction with Bulmer Hobson. The organisation was constructed upon the concepts employed by the Baden Powell scout movement in Britain. Conversely, Na Fianna boys additionally received training in firearms, with the intention to form the basis for a national army.[30] Molony and Markievicz organised a commune at Belcamp Park in Raheny, where Na Fianna would run weekend camps and experiment in farming.[31] The experiment failed with objections from the land Agent in relation to damage to the property and from the locals regarding the disruption by the boys.[32] Molony was also involved in the formation of the Fianna Players who staged performances.[33] Although Na Fianna subsequently played a role in the 1913 Lockout and the Rising (events which Molony was significant in), the organisation became increasingly under the control of the IRB, to the exclusion of Molony and Markievicz. This marginalisation is evident when Hobson omitted them from the Howth gunrunning.[34]

Molony’s ideology began to branch out into socialist ideals with the sentiment of backing ‘the side of the underdog.’[35] From 1910 she contributed to the column ‘Labour Notes’ in Bean na hÉireann, which dealt with trade unionism whilst placing an emphasis on women’s rights.[36] Molony’s iconoclastic commentaries questioned the romantic image portrayed in the Irish Homestead of a celebrated national archetype.[37] Molony also considered Irish history to develop her understanding, analysing the land distribution as Connolly explored in Labour in Irish History.[38] She became involved in union activities of Irish Transport and General Workers Union operating from Liberty Hall under James Larkin.[39] Returning from a meeting, which was to discuss opposition to the impending royal visit, Molony was arrested. Molony was frustrated at the minimal response IRB to royal visit; they had arranged a trip to the grave of Wolfe Tone which she regarded as ‘too tame.’[40] She had been provoked to throw stones at the king and queen’s portrait who she felt appeared ‘smug and benign, looking down on us.’[41] Given a one-month prison sentence, she was released when Anna Parnell paid her fine.[42] At a ’monster demonstration’ celebrating her liberation, Molony was almost re-arrested as she denounced King George V as ‘one of the greatest scoundrels in Europe.’[43] These actions raised her public profile and reveal her growing radicalism, as she moved ‘from propaganda to agitation.’[44]

By 1911 Inghinidhe was decreasing in popularity and Molony began working full time as an actress, whilst still maintaining union activities.[45] According to Molony to it was through Bean na hÉireann that she came to James Connolly’s notice, as he enquired after from her America and a correspondence developed.[46] Molony was a supporter of socialism as her column ‘Labour Notes’ attested. Connolly, as a socialist was also shared her opinion on feminism, maintaining that ‘the worker is the slave of the capitalist society, the female worker is the slave of that slave.[47] When Connolly returned to Ireland Molony declined his proposal for a position in the IWWU.[48] Molony fell ill in 1912 and was treated by Dr Kathleen Lynn. Like her cousin Markievicz before her, Dr Lynn became politicised after this encounter and was ‘converted (…) to the National movement.’[49] Lockout began in September 1913, in response to a strike of the Dublin Tramway Company. Molony called on her practised skills of the theatre to masquerade the recently released Larkin as a member of the clergy, allowing him to give a speech to the crowd.[50] This provoked a baton charge by the Dublin Metropolitan Police, which became known as ‘Bloody Sunday.’[51] The Irish Citizen Army was established to defend the workers from a possible reoccurrence of police violence.[52] During the Lockout the efforts of the women operating from the Liberty Hall kitchen were significant as they provided food for the families affected. Matthews contends that Inghindhe and the Irish Women’s Franchise League intended in exchange for their efforts, to proselytise the disadvantaged families, converting them to their cause.[53] Molony split her time between Liberty Hall and the stage, often disappearing between scenes. This irritated the Abbey management who dubbed her ‘that girl from Liberty Hall.’[54] This division of attentions eventually lead to a breakdown and consequently Molony passed a year with Gonne in France recovering.[55] After the outbreak of war, Molony nursed the unwounded soldiers with Gonne and her daughter Iseult.[56] Gonne continued to appeal to W.B. Yeats in the Abbey to get a position for Molony in the Theatre, she was eager to return to Ireland with the understanding that ‘England’s difficult was Ireland’s opportunity.’[57]

Molony returned to Ireland in 1915 and was offered Delia Larkin’s role as secretary of the IWWU. In undertaking this position, she also assumed the management of the food kitchens and the running of the co-operative shop, which had been established to provide work for those impacted by union militancy.[58] Molony joined the ICA, which had become increasingly nationalist in its’ outlook since the departure of Larkin. She was involved in drilling the ICA women, lecturing and organising first aid classes, which were taught by Dr. Lynn.[59] Molony took on the proprietorship of Connolly’s Workers’ Republic, which was printed from Liberty Hall.[60] Tensions were heating up in the city towards the end of 1915. Reproach for the ‘Fan go Fóills,’ the ‘cautious’ Irish Volunteers movement became more prevalent in the newly established Workers’ Republic.[61] When Connolly failed to get a reaction from the October dockworkers’ strike, he had begun to plan for an independent ICA revolt.[62] Connolly disappeared for three days in January 1916 and was co-opted into the IRB Supreme Council, agreeing a rebellion with them for Easter Sunday.[63] Connolly advised Molony and Markievicz that he had ‘converted (his) enemies.’[64] As a lynchpin in the undertakings of Liberty Hall, Molony was central to the preparations for the Easter Rising. Military regalia and cartridges were produced at the co-operative store and Liberty Hall acted as a meeting place and post office for ammunition and communiqué.[65] Molony records that although she was not directly informed of the date, she felt the Rising was imminent as the activity intensified.[66] Connolly’s employment of the tactic he termed ‘Wolf Wolf,’ whereby there was incessantly notifications of forthcoming revolt, meant that most outside of the inner circle were unsure what was planned.[67] Easter Sunday was spent in preparations, despite Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order. In Liberty Hall the women organised food rations and Molony spent the night in the back room sleeping on copies of the 1916 Proclamation.[68]

Molony was sent, under the command of her fellow Abbey actor, Séan Connolly to attack Dublin Castle.[69] There was confusion upon reaching the Castle; the Sergeant on duty initially thought it was just a display and Connolly shot him, urging the company to go inside before the gate was closed.[70] They stalled to their futility. Molony put this failure down to the success of Connolly’s ‘Wolf Wolf’ tactic. Nevertheless it is apparent that they were lacking the communication required for an effective revolt. They then took up positions in City Hall without issue. Molony was dispatched to the General Post Office (G.P.O.) to request reinforcements and Séan Connolly was mortally wounded not long after she returned to City Hall. Dr. Lynn described Connolly as ‘walking upright’ despite being ‘advised to crouch and take cover as much as possible.’[71] Possibly this was carelessness amid the confusion of conflict but it correlates with Tom Clarke’s image of the Irish in the Boer War refusing to crawl under gunfire, ‘charg(ing) forward even if it meant death.’[72] The building was destroyed by heavy machine gunfire and the company surrendered.[73] Molony was arrested and sent to Ship Street Barricks. Dr Lynn, who was interned with Molony, depicted the poor conditions; instead of beds they had to use a series of rectangular cushions called ‘biscuits’ along with lice-infested coverings.[74] Molony was transferred to Kilmaninham where she recalls hearing the leaders executions at dawn.[75] She was in the minority transferred to England and they were interned initially in Lewes prison where they were ‘well treated,’ although Molony advised her fellow internees not to acknowledge this.[76] Molony was afterwards taken to Aylesbury prison.[77] Most women participants were released ‘in view of their sex,’ however Molony was deemed an ‘extremist of some importance.’[78] She was released at Christmas as part of a general amnesty of prisoners.

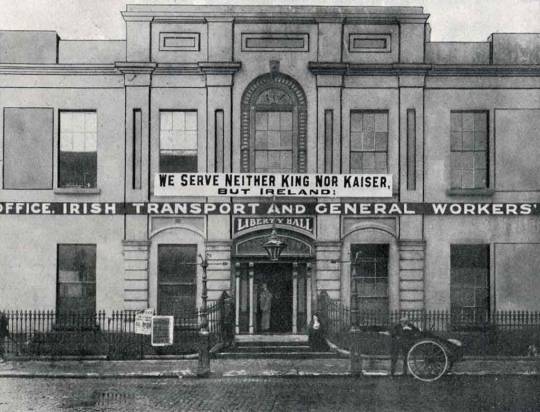

Liberty Hall

The atmosphere in Liberty Hall had changed drastically after the Rising, it was as Molony defined, ‘mainly a Trade Union Headquarters.’[79] Molony had appealed to Louie Benne, who wanted to separate the union from nationalism, to manage the IWWU in her absence. A commemoration was planned for Easter 1917. Copies of the Proclamation were posted throughout the city and flags were hoisted at the ruined G.P.O. and in the building opposite the College of Surgeons. There was some resistance to the demonstration; comparing it with the lack of protest for the royal visit, Molony considered it to be the design of the IRB.[80] Jinny Shanahan and Molony erected a scroll inscribed, ‘James Connolly Murdered – May 12th 1916,’ on the roof of an unreceptive Liberty Hall.[81] They barricaded the access to the roof with coal, as they were aware of the union’s hostility toward the ICA.[82] A standoff with the authorities ensued, with the military supposing there was ICA unit challenging them. The door was broken down and to the dismay of the trade unionists, the authorities held Liberty Hall’s food kitchen in jeopardy.[83] The mood had changed and Molony discovered the unique combination of trade unionism, socialism and separatist nationalism that Connolly imbued was no longer present in Liberty Hall. The feminist agenda had been setback evident in the exclusion of women from the new Sinn Féin Executive, this regression perhaps contributing to the historical amnesia regarding women’s participation.

Helena Molony embodied the spirit of activism at the fin de siècle. She actively participated and was a central figure in the various overlapping networks, politically, socially and culturally. Through her activism, Molony broke many social boundaries and the progression of her ideology can be perceived as she became more militant and radicalised. Initially conforming under the gendered activism of Inghinidhe na hÉireann, her activism developed into militaristic propaganda and eventual militarism, boasting that ‘even before the Russian Army had women soldiers, the Citizen Army had them.’[84] Because Molony and the rest of the women combatants were operating outside the gendered stereotype, their behaviour was unanticipated, making women’s elusive roles crucial to the subterfuge of rebellion. Although the 1916 women attempted to shatter the accepted mould, they were distinguished from the men and treated more leniently. Despite the empowerment their participation in the Rising afforded, they were still regarded as less capable. This was exhibited in Connolly’s advice to the ICA women prior to mobilisation concerning use of their weapons, ‘Don’t use them except in the last resort.’[85] Despite the militant rhetoric, Molony appears to have been troubled at the sight of enemy casualties, wanting to ‘do something’ for a wounded British soldier and she ‘did not like to think of the policeman dead.’[86] Upon entering City Hall, Molony looked for a kitchen and an area for an infirmary, both domestic issues. In her participation in the Rising, did Molony actual make a significant advancement from the role typecast for her by society or was she just playing another character?

[1] Variants of her surname are used in the sources; her birth certificate uses Moloney, however she spelled her name Molony, as was used on her death certificate.

Nell Regan, ‘Helena Molony (1883-1967),’ in Mary Cullen and Maria Luddy (eds), Female Activists; Irish Women and Change 1900-1960 (Dublin: Woodfield Press, 2001), p. 141

[2] Frances Clarke and Lawrence William White, ‘Molony, Helena,’ in James McGuire and James Quinn (eds) The Dictionary of Irish Biography Online, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[3] Imbid, p.38 and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 142

[4] Fearghal McGarry, ‘Helena Molony: A Revolutionary Life’, History Ireland, Vol. 21, No. 4 (July/August 2013), p. 38 and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 142

[5] Helena Molony, Witness Statement Document No. 391, Bureau of Military History, p.4 and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 142

[6] R. M. Fox, Rebel Irishwomen (Dublin: 1935), p. 121 and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 142

[7] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 6

[8] Clarke and White, ‘Molony, Helena’

[9] Roy Foster, Vivid Faces (London: Penguin, 2014), p.120

[10] Developed from an incentive campaign to reward children who refrained from attending the royal celebrations. McGarry, ‘Helena Molony: A Revolutionary Life’, p.38

[11] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 2

[12] Doc. 86, ‘Indhinidhe na hÉireann,’ United Irishman, 13 October 1900

[13] Czira, Sidney, BMH W.S. Doc No. 909, pp.13-14

[14] McGarry, ‘Helena Molony: A Revolutionary Life,’ p. 39

[15] Ann Matthews, Renegades: Irish Republican Women 1900-1922 (Cork: Mercier Press, 2010), p. 62

[16] Sydney Czira, BMH W.S. Doc No. 909, p. 10

[17] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 10

[18] Griffith advised Sidney Gifford against participation, Sidney Czira, BMH W.S. Doc No. 909, p. 10, This was possibly due to the negative reaction this his sister received, Matthews, Renegades, p. 62

[19] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p.8,

[20] Fox, Rebel Irishwomen, p. 122

[21] Foster, Vivid Faces, p.172

[22] Griffith’s contributions were under a pseudonym. Foster, Vivid Faces, p.172

[23] Sheehy Skeffington, Hanna, ‘Sinn Féin and Irishwomen,’ Doc.87, Bean na hÉireann, November 1909, in Maria Luddy, Women in Ireland 1800-1918; A Documentary History (Cork: Cork University Press, 1995), pp. 302-303

[24] Sinn Féiner, Reply to ‘Sinn Féin and Irishwomen,’ Doc. 87, Bean na hÉireann, December 1909, in Luddy, Women in Ireland 1800-1918, pp. 303

[25] Helena Molony, Editorial, Bean na hÉireann, February 1909, in Angela Bourke (ed), The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing Vol. V; Irish Women’s Writing and Traditions (Cork: Cork University Press, 2002), p. 101.

[26] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 10

[27] Matthews, Renegades, p.72

[28] Steve Wilmer, ‘Travesties: Ideologies and the Irish Theatre Renaissance,’ Theatre Ireland, No. 28 (Summer 1992), pp. 33

[29] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 6 and Matthews, Renegades, p.65

[30] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 144

[31] Experiments developed from the socialist commune of John Vandeleur, Foster, Vivid Faces, p.88 and Marnie Hay, ‘The Foundation and Development of Na Fianna Éireann, 1909-16,’ Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 36, No. 141 (May 2008), p.67

[32] Eugene Coyle, ‘The Belcamp Park Story: The Swift-Grattan-Markievicz Connection,’ Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 63, No. 1 (April 2010), p. 65

[33] Seamus Cashin, BMH W.S. Doc No. 8, p. n/a

[34] Marnie Hay, ‘The Foundation and Development of Na Fianna Éireann,’ pp. 65-66

[35] Fox, Rebel Irishwomen, p. 122

[36] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 145

[37] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 146

[38] Fox, Rebel Irishwomen, p. 123, and Connolly, Labour in Irish History, p.28

[39] Matthews, Renegades, p.75

[40] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 16

[41] Ibid, p. 16

[42] Parnell paid the fine anonymously, wanting Molony to transmit a manuscript of her work The Tale of the Great Sham, Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 147

[43] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 147, and Matthews, Renegades, p.76

[44] McGarry, ‘Helena Molony: A Revolutionary Life,’ p. 39

[45] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 147

[46] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 17

[47] Connolly, The Re-conquest of Ireland, UCC Celt, p. 239

[48] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 148

[49] Lynn BMH W.S. Doc No. 357, p. 1, and Matthews, Renegades, p. 83

[50] Czira, BMH W.S. Doc No. 909, p. 16

[51] Clarke and White, ‘Molony, Helena’

[52] Matthews, Renegades, p. 83

[53] Ibid, p. 86

[54] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 149

[55] McGarry, ‘Helena Molony: A Revolutionary Life,’ p. 40

[56] Gonne, BMH W.S. Doc No.317, p. 4 and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 149

[57] Ibid, pp. 149-150

[58] Ibid, p. 150, and Hackett, BMH W.S. Doc No. 546, p. 1

[59] Gonne, BMH W.S. Doc No.317, p. 18, McGarry, ‘Helena Molony: A Revolutionary Life,’ p. 40, and Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 21

[60] McGarry, ‘Helena Molony: A Revolutionary Life,’ p. 40

[61] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 22, and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 151

[62] D.R. O’Connor Lysaght, “The Irish Citizen Army 1913-1916, White, Larkin and Connolly”, History Ireland, Vol. 14, No.2, (March-April 2006), p. 21

[63] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 151

[64] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 25

[65] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 152

[66] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, pp. 28-29

[67] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 27

[68] Ibid, p. 32 and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 152

[69] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 34

[70] Ibid, p. 34

[71] Lynn, BMH W.S. Doc No.357, p. 5

[72] Czira, BMH W.S. Doc No. 909, p. 20

[73] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, pp. 38-39

[74] Lynn, BMH W.S. Doc No.357, part 2, p. 2

[75] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 41

[76] Perolz BHM W.S. Doc No. 246

[77] Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 153

[78] ‘Letter from Rt. Hon. Sir J. G. Maxwell, Commander in Chief, Ireland, to the Secretary, War Office, 10 May 1916,’ Doc. 90a, in Maria Luddy, Women in Ireland 1800-1918; A Documentary History (Cork: Cork University Press, 1995), p. 317 and Regan, ‘Helena Molony,’ p. 153

[79] Molony BMH W.S. Doc No. 391, p. 47

[80] Ibid, p. 46

[81] Ibid, p. 47

[82] Ibid, pp. 47-48

[83] Ibid, pp. 48-49

[84] Ibid, p. 39

[85] Ibid, p.33

[86] Ibid, p.36 & p. 35

0 notes

Photo

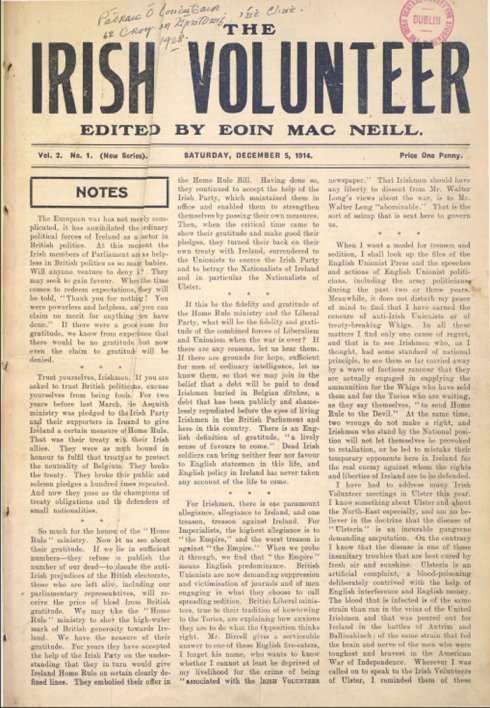

The front page of The Irish Volunteer on December 5, 1914.

Eoin MacNeill (Professor of Early--Medieval History at University College Dublin) was the co-founder of Gaelic League, who later established the Irish Volunteers after the persuasion of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (mainly by IRB member and Fianna Éireann co-founder Bulmer Hobson).

IRB used the Irish Volunteers as a front for their public recruitment. They planned to stage an armed rebellion under the Volunteers and to eventually establish a republic after the country had gained independence from the UK.

Although MacNeill was still the chief of staff of the Irish Volunteers he did not partake nor endorse the 1916 uprising. He felt that they were at a disadvantage in an open battle against the empire. Important to note that Hobson also did not participate in the planning and had also opposed the uprising.

IRB member Patrick Pearse (who was sworn into the IRB by Hobson, by the way) issued orders for three days of maneuvers to all Volunteers, beginning on Easter Sunday, but in actuality Sunday was the cue for the insurrection.

MacNeill realized the true nature of the IRB's plan and the fact the Volunteers wouldn't be receiving any support from Germany: MacNeill issued a countermand to the Volunteers. He successfully delayed the uprising for one day and confined the fighting to Dublin. In preventing Hobson from spreading MacNeill's countermand the IRB held Hobson hostage at a safehouse in Phibsboro until the uprising was over.

Over two hundred personnel from the Irish Citizen Army participated with the Volunteers in the uprising.

The Rising wasn't strategically successful; many Volunteers were arrested-- even the ones who did not actively participate in Dublin.

In 1919, the Irish Volunteers became the Irish Republican Army

Significant to the book:

SPOILERS!! SKIP IT IF YOU HAD NOT READ THE LAST THREE OR SO CHAPTERS!!

The orders for three days of maneuvers enabled Doyler (who served the Irish Citizen Army) to return to Glasthule and reunite with Jim. On Easter Sunday, Doyler kept his promise and swam with Jim to Muglins Rock and claimed it for themselves.

Jim inadvertently joined the Irish Volunteers after he'd left the Ballygihen House with Doyler's uniform to join the fighting near Shelbourne Hotel (Ch 19, 20).

Source: photo

#Bulmer Hobson#Doyler Doyle#Irish Citizen Army#Irish Republican Brotherhood#Irish Volunteers#Jim Mack#Patrick Pearse#The Irish Volunteer#Eoin MacNeill

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roger Casement | A Man of Mystery

Roger Casement | A Man of Mystery

In the week after Roger Casement’s execution, on 3 August 1916, newsreel footage of the nationalist leader was shown in cinemas across America. At a conservative estimate, some 15 million US citizens saw the moving pictures. A century on, this fragment of film provides a fascinating insight.

Casement is glimpsed at his desk writing: The daily activity he performed above any other. He used the pen…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Alice Milligan#Alice Stopford Green#Angus Mitchell#Antrim#Banna Strand#British Foreign Office#Bulmer Hobson#Clan Na Gael#Co. Kerry#Congo#Congo Free State#Dublin#England#Eoin MacNeill#Germany#IRB#Ireland#Irish Brigade#Mario Vargas Llosa#Peru#Roger Casement#The Dream of the Celt

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roger Casement | A Man of Mystery

Roger Casement | A Man of Mystery

In the week after Roger Casement’s execution, on 3 August 1916, newsreel footage of the nationalist leader was shown in cinemas across America. At a conservative estimate, some 15 million US citizens saw the moving pictures. A century on, this fragment of film provides a fascinating insight.

Casement is glimpsed at his desk writing: The daily activity he performed above any other. He used the pen…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Alice Milligan#Alice Stopford Green#Angus Mitchell#Antrim#Banna Strand#British Foreign Office#Bulmer Hobson#Clan Na Gael#Co. Kerry#Congo#Congo Free State#Dublin#England#Eoin MacNeill#Germany#IRB#Ireland#Irish Brigade#Mario Vargas Llosa#Peru#Roger Casement#The Dream of the Celt

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roger Casement | A Man of Mystery

Roger Casement | A Man of Mystery

In the week after Roger Casement’s execution, on 3 August 1916, newsreel footage of the nationalist leader was shown in cinemas across America. At a conservative estimate, some 15 million US citizens saw the moving pictures. A century on, this fragment of film provides a fascinating insight.

Casement is glimpsed at his desk writing: The daily activity he performed above any other. He used the…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Alice Milligan#Alice Stopford Green#Angus Mitchell#Antrim#Banna Strand#British Foreign Office#Bulmer Hobson#Clan Na Gael#Co. Kerry#Congo#Congo Free State#Dublin#England#Eoin MacNeill#Germany#IRB#Ireland#Irish Brigade#Mario Vargas Llosa#Peru#Roger Casement#The Dream of the Celt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roger Casement – A Man of Mystery

Roger Casement – A Man of Mystery

In the week after Roger Casement’s execution, on 3 August 1916, newsreel footage of the nationalist leader was shown in cinemas across America. At a conservative estimate, some 15 million US citizens saw the moving pictures. A century on, this fragment of film provides a fascinating insight.

Casement is glimpsed at his desk writing: The daily activity he performed above any other. He used the…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Alice Milligan#Alice Stopford Green#Angus Mitchell#Antrim#Banna Strand#British Foreign Office#Bulmer Hobson#Clan Na Gael#Co. Kerry#Congo#Congo Free State#Dublin#England#Eoin MacNeill#Germany#IRB#Ireland#Irish Brigade#Mario Vargas Llosa#Peru#Roger Casement#The Dream of the Celt

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roger Casement: A Man of Mystery

Roger Casement: A Man of Mystery

In the week after Roger Casement’s execution, on 3 August 1916, newsreel footage of the nationalist leader was shown in cinemas across America. At a conservative estimate, some 15 million US citizens saw the moving pictures. A century on, this fragment of film provides a fascinating insight. Casement is glimpsed at his desk writing: The daily activity he performed above any other. He used the pen…

View On WordPress

#1916 Easter Rising#Alice Milligan#Alice Stopford Green#Angus Mitchell#Antrim#Banna Strand#British Foreign Office#Bulmer Hobson#Clan Na Gael#Co. Kerry#Congo#Congo Free State#Dublin#England#Eoin MacNeill#Germany#IRB#Ireland#Irish Brigade#Mario Vargas Llosa#Peru#Roger Casement#The Dream of the Celt

0 notes