#Antoinette de Maignelais

Text

[Agnès Sorel] has been paired with her cousin Antoinette de Maignelais in a binary relationship that flatters the former at the latter’s expense.

-Tracy Adams, "Queens, Regents, Mistresses: Reflections on Extracting Elite Women’s Stories from Medieval and Early Modern French Narrative Sources"

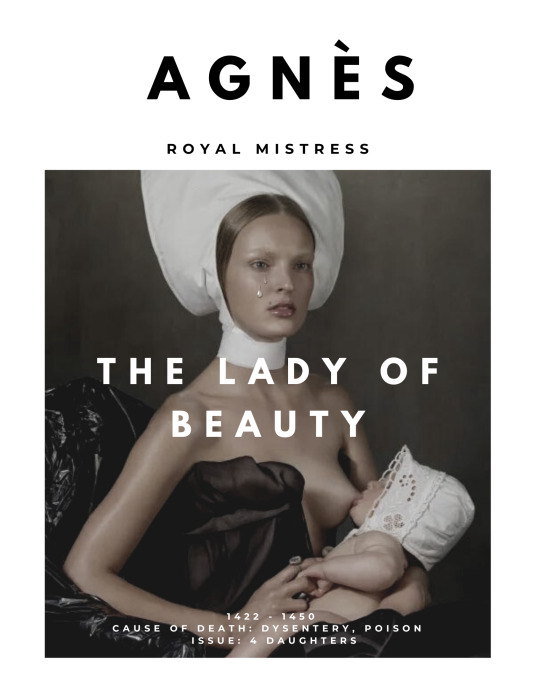

Different from her nineteenth-century historians, contemporary chroniclers write little that is positive about Agnès Sorel, except that she was beautiful. They are still less enthusiastic about Antoinette de Maignelais. Antoinette’s reputation worsens in seventeenth-century historical romances, where she becomes Agnès’s dark and envious double, sometimes responsible for Agnès’s death. Following Antoinette into the nineteenth century, we find nothing good about her in histories of that period, either, where she is typically depicted as motivated by the desire for wealth. […] Even some recent historians read the cousins in this way. According to one, Agnès’s “replacement was greedy and cynical;” in contrast with Agnès, who had “brightened the maturity of a fragile and tormented man, raising him above himself, Antoinette lowered him to the level of a lustful old man whose excesses outraged his entourage.”

The difference in the reputations, or afterlives, of the cousins is striking. Several factors can explain the discrepancy. The first, as I have noted, is that Antoinette later became the mistress of Duke François II. Breton chroniclers did not describe Antoinette favorably, and the relationship undoubtedly diminished her prestige, suggesting that she was motivated by greed rather than love. In contrast, Agnès died at the height of her glory, adored by the king. Another factor is the Melun diptych, commissioned from painter Jean Fouquet by one of the executors of Agnès’s will and royal favorite Etienne Chevalier, whom we have just seen with Antoinette and the king at the chateau of Ville Dieu. This gorgeous Virgin with child depicted on the left panel of the diptych is said to bear the facial features of Agnès. The image has left an enduring impression of Agnès as both pure and erotic. No image at all memorializes Antoinette, much less a fabulous one like the Melun Virgin. Still another is that Charles VII never married Agnès to anyone, which might suggest a particularly deep affection; in the eyes of historians over the years, the “double” adultery of Antoinette and the king has been regarded as the more sinful of the two relationships.

In addition to these factors, as I have noted, the king fathered none of Antoinette’s children: two of her sons, Artus and Antoine, were fathered by André de Villequier, and two sons and two daughters by Duke François II of Brittany. The king recognized his three daughters by Agnès, and all were handsomely married. This matters because Agnès’s daughters and their families took the lead in shepherding Agnès’s positive image into future generations.

...The Agnès/Antoinette binary, like its Marie/Eve counterpart, allowed the role of the royal mistress to be conceived of positively, anchoring the role in its positive guise to Agnès while pushing negative associations onto Antoinette. For the long-term effect of the binary I return to the narrative of the French royal mistress as it emerged in the nineteenth century, when Agnès and Antoinette became the two essential faces of the role: Agnès as the ideal that justifies or hides Antoinette, the political reality, or, put slightly differently, Agnès as the loving mistress persona giving cover to Antoinette, the political actor. Agnès and Antoinette, beautiful muse versus greedy opportunist, combined, offer a perfect standard for distinguishing the good mistress from the bad and promoting the good. For this reason, Antoinette’s role might be considered a sort of supplément to the role of royal mistress as realized by Agnès, who was typically assumed to have been little interested in politics. Antoinette might be seen as the active element required to complete the role; the cousins together add up to the French royal mistress of the later type.

#I love Antoinette a lot#historicwomendaily#Antoinette de Maignelais#agnes sorel#Agnès Sorel#french history#Charles VII#my post#queue

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

women in history [10/?] Antoinette de Maignelais, favorite of Francis II, Duke of Brittany

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notorious Women → Women of Charles VII’s Court

Though Charles VII had successfully expelled the English and oversaw the conclusion of the Hundred Years’ War, his legacy became largely overshadowed by the women in his life. From the brilliant political strategy of his mother in law, and martyrdom of a young peasant girl, who guided his path to victory, to the love of an extravagant beauty and bitter betrayal by her cousin, each woman’s story correlates with all of his success and ultimate downfall.

#historicalwomendaily#historicwomendaily#women of history#historical figures#charles vii#joan of arc#Agnes sorel#Marie of Anjou#yolande of Aragon#Antoinette de maignelais#hundred years war#french history#my post#my aesthetic post

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#history#historyedit#weloveperioddrama#perioddramaedit#Antoinette de Maignelais#breton history#French History#15th century#our edits#by Julia

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Agnès Sorel part 2 While pregnant with their fourth child, she journeyed from Chinon in midwinter to join Charles on the campaign of 1450 in Jumièges, wanting to be with him as moral support. There, she suddenly became ill, and after giving birth, she and her child died on February 9, 1450. She was 28 years old. While the cause of death was originally thought to be dysentery, scientists have now concluded that Agnès died of mercury poisoning. She was interred in the Church of St. Ours, in Loches. Her heart was buried in the Benedictine Abbey of Jumièges. Charles' son, the future King Louis XI, had been in open revolt against his father for the previous four years. It has been speculated that he had Agnès poisoned in order to remove what he may have considered her undue influence over the king. It was also speculated that French financier, noble and minister Jacques Coeur poisoned her, though that theory is widely discredited as having been an attempt to remove Coeur from the French court. Her cousin Antoinette de Maignelais took her place as mistress to the king after her death. In 2005 her remains were exhumed and examined by French forensic scientist Philippe Charlier, who determined that the cause of death was mercury poisoning, but offered no opinion about whether she was murdered. Mercury was sometimes used in cosmetic preparations or to treat worms and might have brought about her death. Sorel plays a main part in Voltaire's La Pucelle. Two Russian operas from the late 19th century also portray her, along with Charles VII: Pyotr Tchaikovsky's The Maid of Orleans and César Cui's The Saracen. She is also a featured figure on Judy Chicago's installation piece The Dinner Party, being represented as one of the 999 names on the Heritage Floor. Two garments use Sorel's name in their descriptors, Agnes Sorel bodice, Agnes Sorel corsage and a fashion style named after her as well, Agnes Sorel style, which is described as a "princess" style of dressing. She was the subject of several contemporary paintings and works of art, including Jean Fouquet's Virgin and Child Surrounded by Angels. #destroytheday

0 notes

Text

Antoinette de Maignelais, Viscountess de la Guerche and Royal Mistress

Antoinette de Maignelais, Viscountess de la Guerche and Royal Mistress

Tombstone of Antoinette de Maignelais (Photo by DeuxPlusQuatre from Wikimedia Commons)

We have told the story of Agnes Sorel, the first officially recognized royal mistress of a French king. Agnes was the mistress of King Charles VII of France and he elevated her to this position. When Agnes died in 1450, Charles swiftly took her cousin Antoinette as his lover although she never became his…

View On WordPress

#Agnes Sorel#Andres Baron de Villequier#Anne of Brittany#Antoinette de Maignelais#Battle of Montlhéry#Blanche de Rebreuve#Cholet#Francis II Duke of Brittany#French history#King Charles VII of France#King Louis XI of France#medieval history#Vicountess de la Guerche#War of the Public Good#War of the Public Weal

0 notes

Text

"If anonymity was required [for reconnaissance and espionage] the woman going about her business, between markets, was the perfect messenger. The Compaignon's news was taken to Lille by a female courier. Writing to the English government on the eve on a projected Scottish invasion Sir William Bulmer was interrupted by the arrival of the wife of one of his spies who had come because 'hir husband was suspect, so that he durst not come hyself. . .'. Equally, Sir William reported that among his spies in Scotland in 1523 he numbered one he called 'the Priores'. In the border war of intelligence it was reported, two years later, that the Scots had lost a female spy at Durham where she was captured and interrogated. There should be little surprise at this, for as Philippe Contamine points out women were much involved in medieval warfare and were employed as messengers and spies throughout the Hundred Years War. But again it is to Edward IV, and the great crisis of his reign, that we must turn. With Warwick and Clarence in France allying with Margaret of Anjou, the king sent Lady Isabel Neville one of her servants bearing an offer of peace. The woman's real business was to plead with Clarence not to be the ruin of his family, and to remind him of the deadly feud between York and Lancaster. Did he really take Warwick at his word when, having done homage to Henry VI's son, he said he would make Clarence king?* The choice of this woman was made because of her shrewdness and because she could gain access to her lady, and thus Clarence, quicker than any male agent."

-Ian Arthurson, "Espionage and Intelligence from the Wars of the Roses to the Reformation", Nottingham Medieval Studies (1991)

*The source for this is the memoirs of Philippe de Commynes, who later served in the French court and was very cognizant of espionage in contemporary politics and warfare. It's not proven or disproven by any other source.

#medieval#gender tag#wars of the roses#edward iv#(kinda not really?)#does anyone know a good book/article about medieval women and espionage?#I have ‘witches spies and Stockholm syndrome’ by finbar dwyver so other than that#I'm trying to find more info on Josine Hellebout who carried out several spying missions against Maximilian (slay)#also I was initially drawn to Antoinette de Maignelais because of the assumption that she was spying on King Charles VII - her lover -#on behalf of his son the Dauphin - but it turns out that she may have simply been a set-up by the Dauphin himself (she's still epic tho)#so...I'd love more info on other women!!#and i'd genuinely love to know the name of the woman sent to Isabel Neville 👀#my post

11 notes

·

View notes