Text

"The white rose was [strongly] associated with the Virgin. It should therefore be acknowledged that one of the motivations behind the emblem being adopted by the house of York, and promulgated by Edward IV alongside the sun device, was its religious resonance. The Virgin was a favoured saint of many royals, not least due to her association with fertility, birth and nurturing lineage, and Marian references can be found in political images and narratives of the fifteenth century. Alongside St Anne, the Virgin was a focus of Yorkist religious devotion. Both Edward IV and his mother Cecily, duchess of York (d. 1495), committed their souls to the Virgin in their respective wills, and images of the saint were depicted in the north clerestory windows in the Yorkist mausoleum at Fotheringhay [...] Edward further demonstrated his favouritism by making the Virgin the joint patron saint of the Order of the Garter in 1469."

-Matthew Ward, "The Livery Collar in Late Medieval England and Wales: Politics, Identity and Affinity"

#I'm mainly posting this for the Order of the Garter part because I didn't know that!#Edward IV#Cecily Neville Duchess of York#medieval#my post#Ward claims that the depiction of the saint at Fotheringhay was 'probably at Cecily's instigation'#which I've removed because it's extremely unlikely#as Laynesmith points out there's no evidence Cecily even visited Fodrygnhey after her husband's death#and did not have any financial responsibility for any of the works and renovations there#nor would Edward IV have needed Cecily's instigation in the first place considering he himself was committed to the imagery#and official records called the manor 'the king’s castle of Fodrygnhey’#queue

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mermaid on Fresco ~ late 14th century ~ St Olaf's Church ~ Poughill ~ Cornwall, England

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

In that search for allies, in particular against France, English rulers had in the past largely confined themselves to two main sources: the Iberian peninsula and the Low Countries. But if any kind of effective encirclement of France was to be considered, or a joint north–south pincer-style operation undertaken, then an alliance – or at least a guarantee or likelihood of neutrality – might be sought with one or more of the Italian principalities or republics. And in the changed and changing political conditions of the later fifteenth century, a permanent English presence at the papal court in Rome, backed by Italian agents and allies, was also increasingly desirable [...] In 1463, both Ferdinand I, king of Naples, and Francesco Sforza, duke of Milan, became knights of the Order. Their evident value as potential, if not actual, opponents of French claims to Aragonese held Naples on behalf of the house of Anjou, and Sforza’s succession to the duchy of Milan in the face of French-backed Orleanist rivalry in 1450, made them potentially useful allies. Then, in 1474, Federigo da Montefeltro, duke of Urbino, was elected, while in 1480 Ercole d’Este, duke of Ferrara became a member. A greater presence of ‘foreigners’ among the knights of the Garter, especially under Edward IV and, to a slightly lesser extent Henry VII, may be revealing of England’s changed situation. Under Edward, eight were elected, of whom four were Italian, three Iberian and one Burgundian (Charles the Bold). Under Henry VII, six were elected, of whom three were Habsburgs (and therefore Austro-Spanish), two were Italian and one Scandinavian.

— Malcom Vale, 'England and Europe, c.1450–1520: Nostalgia or New Opportunities?' | The Fifteenth Century XIX: Enmity and Amity

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

— Glenn Richardson and Susan Doran, Tudor Monarchs and their Neighbours

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Among scholars of late medieval spirituality, Johanna is perhaps best known for her relationship with Birgitta. For many modern scholars—as for Margareta Clausdotter—the friendship between the fastidious Swedish prophetess and Naples’s purportedly lascivious queen has long presented a conundrum. Birgitta’s rich, prolific career intersected Johanna’s at crucial junctures, and there is abundant evidence for their friendship. Birgitta’s biting prophetic invective against Naples’s queen, as well as her apparent affection for her, are often remarked on in Birgittine scholarship. Despite Birgitta’s visions of Johanna (discussed below), there is overwhelming evidence of their mutual regard. Johanna was a prominent supporter of early efforts to canonize Birgitta and promote her cult, and she played an important role in the saint’s later years.

…Johanna’s patronage of Birgitta had its reward: In the Regno and elsewhere, especially in early Birgittine literature, Johanna was memorialized as the saint’s “especially good friend.” Johanna’s friendship with Birgitta began in 1365, when Birgitta visited the tomb of St. Thomas at Ortona. After she miraculously healed the son of Lapa Buondelmonte, Niccolò Acciaiuoli’s sister, Birgitta entered court circles and met Johanna. …Birgitta stopped again in Naples as she traveled from Jerusalem back to Rome, where she had lived since 1350, remaining for several months as Johanna’s guest while she recovered from the arduous journey. She gained fame in Naples for her public attacks on the city’s immorality—prompted by Johanna herself, who asked Birgitta to pray and prophesy for her people and arranged for a panel of theologians to examine her prophecies—and for the healing miracles she performed. Birgitta spoke out against what she perceived as Neapolitan depravity and gave Johanna herself a long, detailed vision about the precarious condition of her soul.

Keep reading

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Johanna’s date of birth is unknown, but she was likely born in 1326 or 1327, the daughter of Marie of Valois (1309–32) and Charles of Calabria (1298–1328), the son and heir of King Robert of Anjou (r. 1309–43). Charles’s death made Johanna and her sister, Mary (b. 1329), Robert’s only direct lineal heirs; Robert designated Johanna his successor in 1330. …Johanna grew up in a court noted by contemporaries for its scholarly culture—although she apparently received no formal education. Instead, she came under the tutelage of her step-grandmother, Sancia of Majorca (ca. 1285–1345), after her mother died in 1332. Sancia was famous for her piety, her devotion to the Franciscan order, and her active religious patronage, and she provided an important model for Johanna. She lived austerely even before widowhood, when she retired to a Clarissan convent, and she had more interest in contemplation and prayer than in the more worldly aspects of queenship, but she wielded great power at court and took a forceful role in the dispute about evangelical poverty.

The Angevin court was not entirely given over to piety, however. The Angevins had long patronized arts and letters, and Robert was famous for his learning. His court attracted and fostered the leading lights of fourteenth century culture, including Giotto, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. It was frequented as well by Robert’s younger brothers, Philip, prince of Taranto (1278–1331), and John of Gravina, duke of Durazzo (1294–1336), and their wives and children, including six sons whose rivalry dominated court gossip and helped shape the first two decades of Johanna’s reign. Johanna was thus the product of a court marked, on the one hand, by religious fervor and a fledgling humanist culture and, on the other, by intrigue and simmering factionalism. In 1343, Johanna succeeded Robert ahead of nine male cousins who could (and did) stake claims to her throne. She would struggle with their resentment, as with their plays for power.

Keep reading

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite History Books || From She-Wolf to Martyr: The Reign and Disputed Reputation of Johanna I of Naples by Elizabeth Casteen ★★★★☆

During the latter half of the fourteenth century, both Provence and the Kingdom of Naples were ruled by a woman. In both cases, the woman became vital to regional memory. Provence’s Countess Jeanne is remembered as pious, beautiful, courtly, wise, and committed to her subjects’ well-being. In the words of an eighteenth-century historian, she was “a woman endowed with all the agreeable traits possible in her sex.”

Naples’s Queen Giovanna is another story entirely. A century after her death, according to a fifteenth-century Neapolitan historian, people still whispered about how she strangled her first husband as retribution for his sexual inadequacies. Hopelessly debauched and voraciously lustful, she squandered her kingdom’s resources until she met a fitting end, murdered by her heir to avenge decades of misrule.

These two historical portraits appear dichotomous, but they actually describe the same woman. Variously known (depending on who was or is describing her) as Jeanne, Jehanne, Joan, Giovanna, Zuana, or Joanna, in life she was most often called— at least in writing— by her Latin name, Johanna. Johanna of Naples, queen of Sicily and Jerusalem and countess of Provence and Forcalquier (r. 1343– 82), was a controversial, complex figure in life and after her death.

Her posthumous reputations serve as a reminder of the mutability of historical memory and how contingent and culturally determined reputation is: One person’s Jeanne is another’s Giovanna. This book is about Johanna’s various, contradictory reputations; through this lens, it examines the cultural mentality of late medieval Europe, particularly diverse, multifaceted reactions to regnant queenship, female sovereignty, and Johanna herself.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

If Edward III had died as expected in autumn 1376 then the marriage between Mary Percy and John de Southeray [bastard son of Edward III and Alice Perrers] would probably have never taken place. When John of Gaunt took control of government in the months following the Good Parliament, Percy was his most active and vigorous supporter. In return for his loyalty he was appointed Lord Marshal, and Gaunt presumably promised Percy other forms of patronage, including the wardship of his half-sister. As it was, there was little that Percy or Gaunt could do until Edward III died in June the following year. Percy was far from being permanently back in the royal fold, however, and when his subsequent actions are viewed as a whole they are highly revealing about his attitude towards royal authority. In 1381 he opposed Gaunt during the Peasants’ Revolt and in 1399 he turned against Richard II in a crucial change of sides, which paved the way for his removal from the throne. This was followed by high-profile rebellions against Richard’s replacement, Henry IV, in 1403 and 1405. Percy clearly did not have a high opinion of, or any sense of loyalty to, anyone – magnate or king – who acted against his interests. It is not surprising then that he reacted so strongly against Alice, and the episode might have helped shape his later actions against the crown.

Laura Tompkins, "Mary Percy and John de Southeray: Wardship, Marriage and Divorce in Fourteenth-Century England", Fourteenth Century X (Boydell and Brewer, 2018)

#john de southeray#mary percy#alice perrers#edward iii#henry percy 1st earl of northumberland#english history#queue

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie of Blois (1345–1404) was a daughter of Joan of Penthièvre, Duchess of Brittany and Charles of Blois, Duke of Brittany. Through her marriage to Louis I, Duke of Anjou, she became Duchess of Anjou, Countess of Maine, Duchess of Touraine, titular Queen of Naples and Jerusalem and Countess of Provence.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

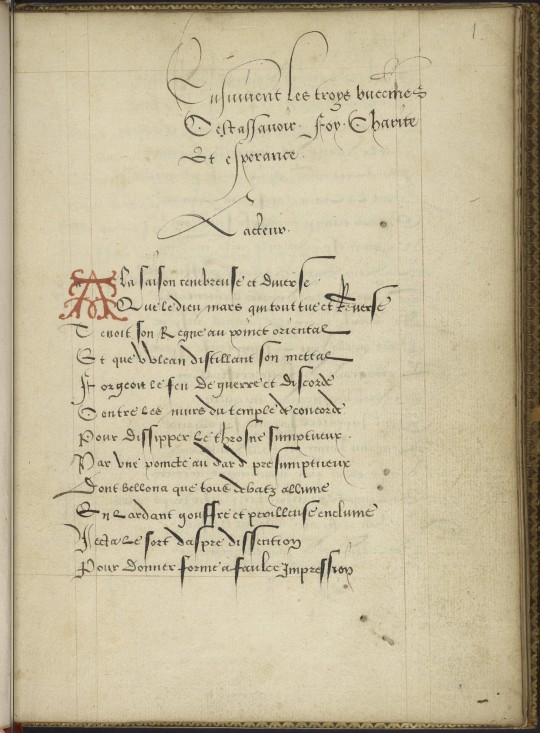

Ms. Codex 850 - [Collection of French poetry]

This manuscript is a collection of 16th-century French poetry, including ballades and rondeaux, by Adrien de Saint-Gelais, Anne de Graville, André de la Vigne, Richard de la Porte, and Jean Marot, with additions perhaps by Robert de la Porte, son of original owner Richard de la Porte. It was possibly written in Rouen, before 1560 CE.

Do you want to know more? Click here for the facsimile, or here for additional information!

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brass aquamanile in the form of a dragon, Northern Germany, circa 1200

from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

495 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was wondering what you knew about Cesare's only legitimate child, Louise Borgia? I'm so curious about her life and her relationships with the people around her, but there's not really much i could find, which is strange considering she was the heir of both her father and mother, and lived till a decent age? Is there anything more we know of her and her life?

Hm, probably the same as you, anon. Sadly there isn’t much information available about her. I think you may already checked out Miron’s work about Charlotte, which brings some information about Louise, so I checked out Sacerdote’s bio to see if I could find anything “new”, but I think he mainly just used Miron’s work. In any case, I’ll add here what I could gather:

Louise kept up a continuous correspondance with her aunt, Lucrezia ,although as far as I know these letters were never published, which it’s a shame, it would be interesting to read them. After her mother died (1514), she was placed under the guardianship of Louise of Savoie, Francis I’s mother. It seems there was conflict between them, in regards to Louise’s assets and the terms in the guardianship etc, but also maybe a clash of personalities.

That made Louise appeal to her grandfather, Albret d’Albret, and then interestingly enough to Isabella d’Este, you probably already read this letter, but just in case, I’m posting it here:

"Madame, with all respect I commend myself to your good grace. Madame, that which I desire above all else in the world is to hear how my good relations and friends are and prosper, and to be advised of you and of Madame the Duchess, my aunt. I have given charge to and sent the bearer of this letter to see you, and to advise me of your news. I beg of you, Madame, to send me news of you by him in full. And if it pleases you to hear of mine, he will inform you amply. Madame, I have also charged him to tell you something else from me. I beg of you to believe it, and to be good enough to help in the matter of which he will speak to you. And in doing so you will make my gratitude always yours. Praying Our Lord to give you a very good and long life. Written at Auxonne this ninth day of July, 15.

"Your very humble niece and good friend,

Louise de Valentinois."

It's interesting that Louise felt she could write to Isabella d'Este, even though the marriage alliance between her and their son, Federico, failed to succedded. It's pretty clear, by the tone of the letter, that some political intrigue was going on, whether it was Louise wanting to know more about her father's inheritance in Italy, or gauging the possibility of the above mentioned marriage alliance her father tried to make with the Gonzaga, perhaps with her aunt Lucrezia helping her with it, as well, given her close relations with the Marquis of Mantua, Isabella's husband. It's possible she was searching for other options, and if that is so, then it implies she wasn't very willing to marry Trémoille. Personally, I find his interest in her a little strange, maybe Louise felt it, too, who knows. Sacerdote says the followingabout this letter:

The letter has no date; but it was certainly written after 1514 - the year of Charlotte d’Albret's death - and before 1517, the year of Louise' marriage. As for the "matter", in which she wanted to interest Isabella d 'Este, it is very likely that it was her inheritance, left to her by her father in Italy. It is known, in fact, that Cesare Borgia had a very high sum on deposit with Genoese, Venetian and Florentine bankers; and before fleeing to Naples he had entrusted to his friend, Cardinal Vera, all his gold and silverware and carpets and other things of value, so that, if he came to die, they were to be sent to his wife. [...] As for the other "affair", her engagement with Federico Gonzaga, son of Isabella, had definitely ended. It begun as early as December 1501, the negotiations for this engagement were then conducted with fervor on both sides. Despite the great aversion that Isabella d'Este and her husband Francesco Gonzaga felt for the Borgias, they nevertheless knew that such a relationship would have a high political value for their house and for their state.

In 1516, Federico Gonzaga was sent to Paris, and he and Louise saw each other, and at the time there was talk about finally making the marriage alliance between the two Houses happen, but for reasons unknown, it failed again. There was also talk of a marriage between Louise and the Medici, with Piero de Medici’s son, Lorenzo de’ Medici.

It seems the prejudice against the Borgia family, esp. against Cesare, ended up touching Louise as well. There was some effort to ignore, or to "look past" Louise' bloodline on her father's side. For example, when Louis II de la Trémoille, her first husband, was asked as to why he chosed the daughter of Cesare Borgia (such a wicked man to their eyes) as a wife? To placed her on the same bed as his former wife, Gabrielle de Bourbon Montpensier? He allegedly is recorded as having answered: “La mia scelta cadde su madamigella de Valentinois, perché ella discende da una razza, la virtù delle cui donne non fu mai posta in questione. /My choice has fallen upon Mademoiselle de Valentinois because she springs from a race whose women's virtue has never been called in question."

As Sacerdote (and Miron) point out, he clearly wasn't talking about the Borgia women, so he was implying that as far as he was concerned, Louise was entirely from d'Albret and their lineage's bloodline, and as such he knew Louise had inheritated the virtues known in her mother and the women’s side of that family, which was why he chose her as his bride.

Louis died in battle, at Pavia in 1525, and Louise re-married Philippe de Bourbon in February 3, 1530. I couldn’t find anything about her relationship with her second husband, which it’s a shame, because that’s something I would like to know more about myself. They have six children:

Claude de Bourbon, Count of Busset, of Puyagut, and of Chalus.

Marguerite de Bourbon

Henri de Bourbon

Catherine de Bourbon

Jean de Bourbon, Seigneur of La Motte-Feuilly and de Montet.

Jerome de Bourbon, Seigneur de Montet.

And iirc by this bloodline, there are still many living descendants today of Cesare and Charlotte.

Louise was a member of the Third Order of Saint Dominic.

She always signed herself as Duchesse de Valentinois, comtesse di Diois, and in a document dated June 18, 1535. It seems she was party to a transaction between her and her cousin, Henri de Navarre, touching the “droits de légitime” (portion that a child has by law in his father’s estate) of her mother, Charlotte d’Albret.

And that’s about all I could gathered, anon, the other Borgia bios I have checked either don’t have anything or they just repeat what was established by Miron and Sacerdote and some French authors. Sorry if it wasn’t too helpful, I really wish we knew more. Again, I'd love to see the letters between Lucrezia and Louise published. I think it would give us more information about her, but as far as I know it hasn’t been.

#ooh interesting#I know Louise was described by a contemporary as:#'a very noble and virtuous lady heiress to perfections as well as the riches of her mother whose manners and#disposition she made her own; a lady in short as chaste virtuous and gentle as her father was possessed cruel and wicked'#though how much this actually truly described her is hard to say 🤷🏻♀️#Louise Borgia#queue

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Matilda alone was in possession of kingly power, beyond any form of wardship over her freedom of action, including that of her husband, who remained in France, focused on subjugating Normandy. Conceptually, this was a problem. English queens had wielded effective political power for centuries, but what legitimized such actions was their relationship to male gendered power; queens could render assistance to their fathers, husbands, and sons, or rule in their place temporarily as regents. But women were not supposed to pursue political power for themselves. Geoffrey of Anjou did not put his Norman campaign on hold to rush to London for a joint coronation, nor did he send young Henry, then aged eight, as a legitimizing presence. Had Matilda been crowned, she would have been crowned alone.” “Greater by Marriage” The Matrimonial Career of the Empress Matilda by Charles Beem

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unknown Artist

Reliquary with St. Valerie holding her head

Partially gilt and champlevé enamelled copper, set with a rock crystal, 27 cm, late 12th/early 13th century

529 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gregory's Chronicle using Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville as a warning lesson for his audience as an abject example on what not to do is still the funniest thing ever.

"Now take heed what love may do, for love will not nor may not cast no fault nor peril in nothing."

Translation: DO NOT - I repeat, DO NOT - follow their example. Did you hear me? DO NOT -

#when your marriage is so scandalous it's literally used as a red alert for others 💅#edward iv#elizabeth woodville#my post#also Gregory calling Edward a slut. loved that part too <3#('it 'were evyr ferde that he had not be chaste of hys levynge')#tbh I wrote this as a dumb shitpost after getting back home drunk a few days ago but on a more serious note:#consider how Gregory emphasized how Edward's nobles and advisors' required him to marry#''a quene good of byrthe acordyng unto hys dygnyte''#and what that clearly implies about Elizabeth Woodville whose marriage to him was framed as inappropriate and a caution to others#It's pretty on-the-nose

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"[Alice Perrers] requested that she be buried in the parish church of Upminster, St Laurence, before the altar of the Virgin Mary. Alice seems to have had an affinity with Mary through her life; a seal of hers from c. 1374 shows an image of the Virgin Mary and child, her tabernacle seized in 1377 had an image of the Virgin Mary on it, and now she wished to be buried before Mary’s altar."

-Gemma Hollman, "The Queen and the Mistress: The Women of Edward III"

#historicwomendaily#alice perrers#my post#I didn't know about this but it's so very intriguing#I wonder if Alice associated herself with Mary to try and assert her own 'quasi-queenship'#(ie: the most powerful woman in the country at the side of a king)#as Mary was obviously important element of queenly iconography in late medieval England#though on the flip side I suspect it would have also raised hackles that Alice - a commoner and royal mistress - was attempting#to present herself in such a way#it's especially interesting to consider in the context of Tompkins' argument that Alice was perceived as 'inverting queenship' (slay)#also this book was ... complicated.#It's very understanding and sympathetic and raised some very good points#but also tried to...massively soften Alice's actions and downplay her role and power in the process#(ie: defending her by diminishing her)#also there's this gem:#'Edward had been markedly restrained with the gifts and favour he had bestowed upon Alice' girl that is a flat-out lie#no other royal mistress of medieval England was ever given so much or honored in such a way.#yes we should emphasize Alice's own proactive role and intelligence in building up her vast estates#but even if that hypothetically hadn't happened#Edward's grants and gifts would have still made her extremely wealthy and powerful regardless#and was also weirdly obsessed with romanticizing Edward III and it got kinda questionable#like yes obviously I think we should ascribe more nuanced motivations and emotions to *Alice* than 'ambitious gold-digger#taking advantage of an aging king'#but I'm not fond of it veering too far on the other side either#I think sometimes we should simply be comfortable admitting when we simply don't know something

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Boleyn Molten Gold Pendant by Common Era

92 notes

·

View notes