#Amir Aghaee

Text

‘Beyond the Wall’ Review: A Grueling Guided Tour of an Iranian Police-State Nightmare

A suicidal blind man and an epileptic fugitive mother become physically and psychologically trapped in Vahid Jalilvand's bruisingly assaultive polemic against Iranian state oppression.

By Jessica Kiang

Sep 8, 2022

11:31am PT

Nobody emerges unscathed — least of all the audience — from Vahid Jalilvand‘s highly effective, deeply unpleasant “Beyond the Wall,” a morbidly violent allegory for the effects of state-sponsored trauma on the individual that places contemporary Iranian society somewhere on the map between the sixth and seventh circles of hell. A strange combination of intricate, almost sci-fi-inflected psychological thriller, splenetic social-breakdown broadside and two-hander (torture) chamber drama, it is an exercise in bravura filmmaking applied to a story so relentlessly grim you might wish it were a little less well-made, giving you an excuse to look away. In his 2017 film “No Date No Signature” (which won Best Director and Best Actor in Venice’s Horizons sidebar), Jalilvand pictured a stratified society teetering on the edge of legality and morality; here, however, it has toppled entirely into the abyss. The only way is down, and the filmmaker is bringing you with it.

These uncompromising intentions are signalled by an opening salvo that would surely be any other film’s brutalizing emotional nadir, as we’re introduced to Ali (“No Date, No Signature” star Navid Mohammadzadeh) in the commission of an attempted suicide. No mere “cry for help,” it is not just the act itself but the manner he has chosen that is shocking: In the dripping damp of a dingy bathroom, Ali wraps a soaking T-shirt around his head, ties a plastic bag over that and shoves his battered hands down behind the shower pipe, effectively cuffing his own arms behind him while he screams and suffocates. The scene is such a trial to witness, it’s possible to miss the brief, disorienting, semi-subliminal inserts where it appears the violence is being done to him by someone else — or to think you have imagined them.

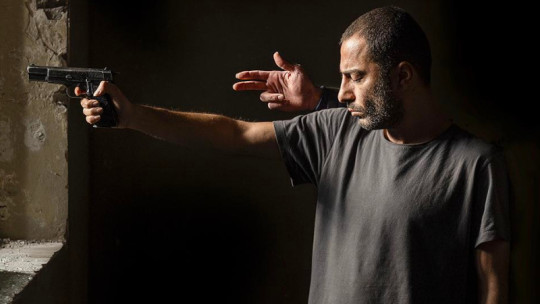

It is only an insistent pounding on his front door that brings Ali back from the brink. Breaking the pipe and tearing off his plastic shroud, he shuffles, gasping, dripping, broken, to answer it. The men at the door inform him that a woman wanted for a heinous crime has fled custody and was last spotted on the fire escape of his forbiddingly enormous apartment building. They suspect him — for some reason more than all the other residents — of harboring her. Ali shoos the men away, but we know that the woman, Leila (Diana Habibi), has indeed infiltrated his home and is cowering beneath a countertop, hands clasped over her bleeding, chapped lips to stifle her sobs. Ali has not seen her, because he does not see anything much. His failing eyesight is not just a temporary symptom of his recent near-death encounter, but a condition brought on from an earlier trauma, and it is degenerating faster than it should, as Ali refuses to use the treatments prescribed by sympathetic doctor Nariman (Amir Aghaee) on his frequent house calls.

It takes a painfully long time — and rather too many sequences of Ali feeling his way down his apartment’s yeasty, peeling walls, lighting cigarettes with palsied hands and peering at a mysterious letter he’s received — but eventually, as must happen, Ali discovers Leila. She is, and remains, terrified throughout but in Ali she has lucked upon the one man in this whole building (perhaps even the one man in all of Iran) who wants, obscurely, to help her. It might be because, given his initial state, he has little to lose. But perhaps it is something else, something like a shot at redemption for the unknown sins of a past that more frequently forces itself into the present as Ali and Leila’s predicament worsens.

It takes a painfully long time — and rather too many sequences of Ali feeling his way down his apartment’s yeasty, peeling walls, lighting cigarettes with palsied hands and peering at a mysterious letter he’s received — but eventually, as must happen, Ali discovers Leila. She is, and remains, terrified throughout but in Ali she has lucked upon the one man in this whole building (perhaps even the one man in all of Iran) who wants, obscurely, to help her. It might be because, given his initial state, he has little to lose. But perhaps it is something else, something like a shot at redemption for the unknown sins of a past that more frequently forces itself into the present as Ali and Leila’s predicament worsens.

The tricksiness of the finale, however, does somewhat undercut the seriousness of the film’s more intriguing ideas about how a prison made of concrete can never so comprehensively constrain us as the prisons of the body and the mind. Ali’s failing eyesight, his nerve-damaged hands, his stooped posture and proliferating scars, as well as Leila’s epilepsy and her son’s muteness, can be read as a fleshy physiological allegory for state violence and oppression, as damage to the body social manifesting in damage to actual bodies. But the metaphor only really works up to the point when Jalilvand’s overly complicated plotting comes round on itself. In any case, after more than two hours of seizures, crashes, riots, shootouts, beatings, and endlessly relived trauma, some of the finer points of the movie’s philosophy may escape you, just as you, too, are longing for escape.

#Iranian Cinema#Vahid Jalilvand#Beyond the Wall#Variety#No Date No Signature#Navid Mohammadzadeh#Diana Habibi#Amir Aghaee

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Beyond the Wall (2022), dir. Vahid Jalilvand

Ali, a blind man, is attempting to commit suicide when he is interrupted by the concierge of his building. He is informed that the police is in search of a woman who has escaped and hidden somewhere in the building. Little by little, Ali finds out that the fugitive woman, Leila, is inside his apartment. After participating in a workers’ protest that led to chaos, she is distraught about her four-year-old son who was lost when she was taken in a police van. Gradually, Ali becomes emotionally attached to her. Wishing to flee reality, helping Leila becomes a refuge in his own world of imagination.

#Beyond the Wall#Vahid Jalilvand#Navid Mohammadzadeh#Diana Habibi#Amir Aghaee#cinema#trailer#Shab Dakheli Divar#Youtube

0 notes

Text

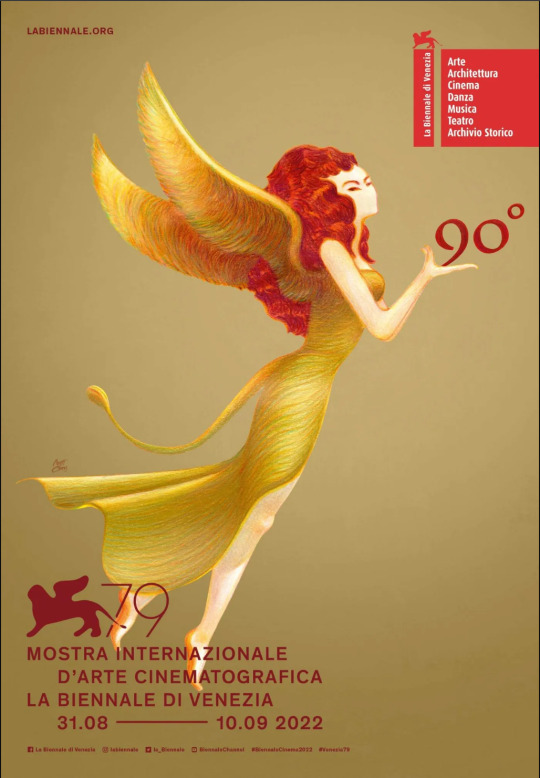

VENEZIA 79 - 90 ANNI DI CINEMA al LIDO di VENEZIA

Manifesto Lorenzo Mattotti

COMPETITION of 79th Venice Film Festival

1. WHITE NOISE - OPENING FILM by NOAH BAUMBACH starring Adam Driver, Greta Gerwig, Don Cheadle, Raffey Cassidy, Sam Nivola, May Nivola, Jodie Turner-Smith, André L. Benjamin and Lars Eidinger/ USA / 136'

2. IL SIGNORE DELLE FORMICHE by GIANNI AMELIO with Luigi Lo Cascio, Elio Germano, Leonardo Maltese, Sara Serraiocco / Italy / 134'

3. THE WHALE by DARREN ARONOFSKY with Brendan Fraser, Sadie Sink, Hong Chau, Samantha Morton, Ty Simpkins / USA / 117'

4. L'IMMENSITÀ by EMANUELE CRIALESE with Penélope Cruz, Luana Giuliani, Vincenzo Amato, Patrizio Francioni / Italy, France / 97'

5. SAINT OMER by ALICE DIOP with Kayije Kagame, Guslagie Malanda, Valérie Dréville, Aurélia Petit / France / 122'

6. BLONDE by ANDREW DOMINIK with Ana de Armas, Adrien Brody, Bobby Cannavale, Xavier Samuel, Julianne Nicholson, Lily Fisher / USA / 165'

7. TÁR by TODD FIELD with Cate Blanchett, Noémie Merlant, Nina Hoss, Sophie Kauer, Julian Glover, Allan Corduner, Mark Strong / USA / 158'

8. LOVE LIFE by KÔJI FUKADA with Fumino Kimura, Kento Nagayama, Atom Sunada / Japan, France / 123'

9. BARDO, FALSA CRÓNICA DE UNAS CUANTAS VERDADES (BARDO, FALSE CHRONICLE OF A HANDFUL OF TRUTHS) by ALEJANDRO G. IÑÁRRITU with Daniel Giménez Cacho, Griselda Siciliani, Ximena Lamadrid, Iker Sanchez Solano, Andrés Almeida, Francisco Rubio / Mexico

10. ATHENA by ROMAIN GAVRAS with Dali Benssalah, Sami Slimane, Anthony Bajon, Ouassini Embarek, Alexis Manenti / France / 97'

11. BONES AND ALL by LUCA GUADAGNINO with Taylor Russell, Timothée Chalamet, Mark Rylance, André Holland, Chloë Sevigny, Jessica Harper, David Gordon Green, Michael Stuhlbarg, Jake Horowitz / USA / 130'

12. THE ETERNAL DAUGHTER by JOANNA HOGG with Tilda Swinton, Joseph Mydell, Carly-Sophia Davies / UK, USA / 96'

13. SHAB, DAKHELI, DIVAR (BEYOND THE WALL) by VAHID JALILVAND with Navid Mohammadzadeh, Diana Habibi, Amir Aghaee / Iran / 126'

14. THE BANSHEES OF INISHERIN by MARTIN MCDONAGH starring Colin Farrell, Brendan Gleeson, Kerry Condon, Barry Keoghan / Ireland, UK, USA / 109'

15. ARGENTINA, 1985 by SANTIAGO MITRE with Ricardo Darín, Peter Lanzani, Alejandra Flechner, Norman Briski / Argentina, USA / 140'

16. CHIARA by SUSANNA NICCHIARELLI with Margherita Mazzucco, Andrea Carpenzano, Carlotta Natoli, Paola Tiziana Cruciani, Luigi Lo Cascio / Italy, Belgium / 106'

17. MONICA by ANDREA PALLAORO with Trace Lysette, Patricia Clarkson, Adriana Barraza, Emily Browning, Joshua Close / USA, Italy / 106'

18. KHERS NIST (NO BEARS) by JAFAR PANAHI with Jafar Panahi, Naser Hashemi, Vahid Mobaseri, Bakhtiar Panjeei, Mina Kavani, Reza Heydari / Iran / 106'

19. ALL THE BEAUTY AND THE BLOODSHED by LAURA POITRAS USA / 113'

20. UN COUPLE (A COUPLE) by FREDERICK WISEMAN with Nathalie Boutefeu / France, USA / 63'

21. THE SON by FLORIAN ZELLER with Hugh Jackman, Laura Dern, Vanessa Kirby, Zen McGrath, Anthony Hopkins, Hugh Quarshie / UK / 123'

22. LES MIENS (OUR TIES) by ROSCHDY ZEM with Sami Bouajila, Roschdy Zem, Meriem Serbah, Maïwenn, Rachid Bouchareb, Abel Jafrei, Nina Zem / France / 85'

23. LES ENFANTS DES AUTRES (OTHER PEOPLE'S CHILDREN) by REBECCA ZLOTOWSKI with Virginie Efira, Roschdy Zem, Chiara Mastroianni, Callie Ferreira / France / 104'

OUT OF COMPETITION

1. The Hanging Sun, by Francesco Cozzini - Closing Film of the Festival

2. Kapag Wala Nang Mga Alon (When the Waves are Gone), by Lav Diaz

3. Living, by Oliver Hermanus

4. Dead for a Dollar, by Walter Hill

5. Kone Taevast (Call of God), by Kim Ki-Duk

6. Dreamin' Wild, by Bill Pohlad

7. Master Gardener, by Paul Schrader

8. Drought, by Paolo Virzi

9. Pearl, by Ti West

10. Don't Worry Darling, by Olivia Wilde

OUT OF COMPETITION - NON FICTION

1. Freedom on Fire: Ukraine's Fight for Freedom, by Evgeny Afineevsky

2. The Matchmaker, by Benedetta Argentieri

3. The Last Days of Humanity, by Enrico Ghezzi and Alessandro Gagliardo

4. A Compassionate Spy, by Steve James

5. Music for Black Pigeons, by Jorgen Leth and Andreas Koefoed

6. The Kiev Trial, by Sergei Loznitsa

7. In viaggio, by Gianfranco Rosi

8. Bobi Wine Ghetto President, Christopher Sharp and Moses Bwayo

9. Nuclear, by Oliver Stone

OUT OF COMPETITION - TV SERIES

1. Riget Exodus (The Kingdom Exodus) - episodes 1-5, by Lars von Trier (1 September)

2. Copenhagen Cowboy - episodes 1-6, by Nicolas Winding Refn

OUT OF COMPETITION - SHORTS

1. Camarera de Piso (Maid), by Lucrecia Martel

2. Look at Me, by Sally Potter

3. As for Us, by Simone Massi

4. When the war is over, by Simone Massi

ORIZZONTI

1. Princess, by Roberto De Paolis - Opening film

2. Obet' (Victim), by Michal Blaško

3. En Los Margenes (On the Fringe), by Juan Diego Botto

4. Trenque Lauquen, by Laura Citarella

5. Vera, by Tizza Covi and Rainer Frimmel

6. Innocence, by Guy Davidi

7. Blanquita, by Fernando Guzzoni

8. Pour la France (For My Country), by Rachid Hami

9. Aru Otoko (A Man), by Kei Ishikawa

10. Chleb I Sol (Bread and Salt), by Damian Kocur

11. Luxembourg, Luxembourg, by Antonio Lukich

12. Ti mangio il cuore, by Pippo Mezzapesa

13. Spre Nord (To The North), by Mihai Mincan

14. Autobiography, by Makbul Mubarak

15. The Syndacaliste (The Sitting Duck), by Jean-Paul Salomé

16. Jang-E Jahani Sevom (World War III), by Houman Seyedi

17. Najsrekniot Čovek Na Svetot (The Happiest Man in the World), by Teona Strugar Mitevska

18. A Noiva (The Bride), by Sergio Trefaut

ORIZZONTI EXTRA

1. L'origine du mal (Origin of Evil), by Sebastien Marnier - Opening film

2. Hanging Gardens, by Ahmed Yassin Al Daradji

3. Amanda, by Carolina Cavalli

4. Zapatos Rojos (Red Shoes), by Carlo Eichelmann Kaiser

5. Nezouh, by Soudade Kaadan

6. Phantom Night, by Fulvio Risuleo

7. Bi Roya (Without Her), by Arian Vazirdaftari

8. Valeria Mithatenet (Valeria is Getting Married), by Michal Vinik

9. Goliath, by Adilkhan Yerzhanov

_________///_______////_______///_______///_______

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un mercoledì di maggio

Un mercoledì di maggio

Cinema: Un mercoledì di maggio

La caparbia resistenza di due donne disperate(mymonetro: 3,00)

Regia di Vahid Jalilvand.

Con Niki Karimi, Amir Aghaee, Shahrokh Foroutanian, Vahid Jalilvand, Borzou Arjmand, Afarin Obeisi, Saeed Dakh, Sahar Ahmadpour, Milad Yazdani.

Genere Drammatico

– Iran,

2015. Durata 102 minuti circa.

Su un quotidiano di Teheran appare uno strano annuncio: un uomo di nome…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

L'Iran ha scelto come proprio rappresentante per gli Oscar 2019 il film No Date, No Signature

L'Iran ha scelto il dramma psicologico di Vahid Jalilvand No Date, No Signature come proprio rappresentante per il miglior film in lingua straniera agli #Oscar2019

La decisione, annunciata venerdì dall'Iran's Farabi Cinema Foundation, arriva nonostante le richieste di alcuni membri del paese di boicottare gli Academy Awards sul ritiro di Washington dall'accordo nucleare Iran 2015.

Scritto e diretto da Jalilvand, il film racconta una complessa storia di un patologo forense, il Dr. Nariman (Amir Aghaee) che ferisce un bambino di otto anni in una collisione con una motocicletta guidata dal padre del ragazzo. Le offerte di aiuto del medico vengono respinte, ma poco dopo, nell'ospedale dove lavora, il dottor Nariman viene a sapere che il ragazzo è stato sottoposto a un'autopsia dopo una morte sospetta.

#bestforeignlanguagefilm

0 notes

Photo

#280 #BedooneTarikhBedooneEmza #NoDateNoSignature #SemDataSemAssinatura ⭐️⭐️⭐️ Como viver uma vida com a culpa martelando sua cabeça? É basicamente isso que vemos em “Sem Data, Sem Assinatura”, culpa e ressentimento recheiam o filme iraniano, vencedor nas categorias ator e diretor da mostra Horizontes em Veneza. Envolvidos em um acidente de carro, os personagens de Amir Aghaee e do premiado Navid Mohammadzadeh, vivem no limite após a fatalidade que proporcionou o segundo encontro entre os dois. Sem nunca ser explícito e sem fazer juízo de valor dos protagonistas, o filme tem alguns clichês mas não prejudica o todo e a mensagem é bem endereçada. #movie #Filmes2017 #MostraSP #Irã🇮🇷 (em Espaço Itaú de Cinema)

#bedoonetarikhbedooneemza#movie#filmes2017#irã🇮🇷#mostrasp#nodatenosignature#280#semdatasemassinatura

0 notes

Text

Gli invisibili. Cosa vedere al cinema dal 10 maggio

Gli invisibili. Cosa vedere al cinema dal 10 maggio

Cosa vedere al cinema questo week end? Come ogni settimana arriva la nostra rubrica di cinema poco visibile. Vi segnaliamo e consigliamo i film in sala con una bassa distribuzione, le pellicole poco pubblicizzate che meriterebbero di essere conosciute. Correte a cercarli nella vostra città prima che vengano tolti, oppure se non li trovate, segnateveli per recuperarli in futuro.

Benvenuto in…

View On WordPress

#Alessandro Parrello#Alessandro Prete#Alireza Ostadi#Amir Aghaee#Andrea Bruschi#Augusto Zucchi#Claudia Vismara#Elyas M&039;Barek#Eric Kabongo#Ettore Belmondo#Florian David Fitz#Francesco Mandelli#Hediyeh Tehrani#Heiner Lauterbach#Igor Maltagliati#Marco Leonardi#Marco Ripoldi#Martina De Santis#Massimiliano Loizzi#Mauro Meconi#Navid Mohammadzadeh#Palina Rojinski#Renato Avallone#Saeed Dakh#Senta Berger#Simon Verhoeven#Ulrike Kriener#Uwe Ochsenknecht#Vahid Jalivand#Valentina Lodovini

0 notes

Text

‘Beyond the Wall’ Review: A Powerful, Twisty Drama About Iranian State Repression

Vahid Jalilvand's film revolving around a suicidal blind man and a runaway mother is one of two Iranian works in Venice competition, alongside Jafar Panahi's 'No Bears.'

BY LESLIE FELPERIN

SEPTEMBER 9, 2022 9:35AM

COURTESY OF TIFF

Iranian director Vahid Jalilvand’s second film No Date, No Signature became Iran’s submission in 2019 for the Oscars’ Best Film Not in the English Language category. It would be a miracle if his latest, Venice competition entrant Beyond the Wall, gleaned the same honor, not because it wouldn’t be a worthy choice — it’s a ravaging, powerful work. It’s just that it’s impossible to imagine the Iranian authorities would approve submitting it.

Overtly critical of the repressive state apparatus, especially its capriciously cruel and violent police forces and merciless justice system, this feature played in Venice without Iranian government support and no doubt places Jalilvand in the ranks of audacious cinema dissidents, along with currently imprisoned filmmakers Jafar Panahi (whose latest No Bears also plays Venice this year), Mohammad Rasoulof and Mostafa Aleahmad.

For this twisty study of guilt and self-sacrifice, Jalilvand has reteamed with acclaimed actor Navid Mohammadzadeh, who co-stared in Jalilvand’s No Date as well as Saeed Roustayi’s recent Cannes competitor Leila’s Brothers. First met trying to kill himself with a wet shirt and a plastic bag in a concrete shower stall, his body covered in bruises and squinting through near-blind eyes, Mohammadzadeh’s lead character Ali pauses his suicide attempt to answer an aggressive knock at his door. It seems Ali lives in an apartment alone, where he’s struggling to cope with his recent loss of vision. But throughout the film he has a steady stream of visits, mostly from a gruff but sympathetic doctor (Amir Aghaee), a meddlesome building manager (Danial Kheirikhah) and a menacing police inspector (Saeed Dakh). The latter is looking for a mysterious woman being hunted by the authorities whom they suspect is hiding in Ali’s building.

It transpires that while answering the door, the woman, Leila (Diana Habibi, fantastic at channeling unhinged desperation) did indeed slip into Ali’s apartment through an unlocked back door, having ascended up a spiral staircase. The staircase is not only an effective fire escape, but also an obvious metaphor for the film’s spiral narrative, which keeps circling back in time to show earlier events from a different point of view.

Terrified for her life and nearly hysterical with worry about her young son, from whom she got separated in some kind of kerfuffle, Leila hides in Ali’s apartment in the shadows where he can’t see her and tries to call a friend for help. Ali can only sense her presence at first, but he leaves out food and gently calls out to her, trying to gain her trust. It would certainly be handy to have someone read the letters for him that keep getting slipped under his door that he can barely decipher. Eventually, Leila awakens from an epileptic fit to the sound of him playing back her voice messages, and slowly the events that brought her to his rooms are revealed.

Jalilvand started out as a theater director before moving into TV and then film, so the stagey feel of the scenes inside Ali’s apartment might seem like a deliberate call back to his earlier career at first, or a budget-saving use of a confined space. However, as the film goes on it gets progressively stranger in terms of time and space, with characters, especially Leila, slipping out one door and reappearing again moments later, having seemingly slipped back into the past, a change of reality that Ali just rolls with.

Meanwhile, the stage, as it were, expands to assimilate an outdoor scene by a closed factory where Leila came some time ago to collect her wages with other protesting workers, her mute son by her side. They get separated when a riot breaks out and the police started randomly arresting whomever they can grab. The noise of the knocking turns out to correspond to a completely different source — the sound design throughout is eerie — and nothing is quite what it seems. Mind you, the overhead shot of Ali’s door, in degraded digital black and white like the feed for a CCTV system, is an obvious early giveaway as to what’s going on.

Powerful though the subject matter is — and brave for all involved considering that a number of taboo subjects are touched on, from suicide to police brutality — Jalilvand’s editing in the final stretch loses some impact with a clunkier-than-necessary pace. Perhaps the filmmakers were challenged by the near two-year process it took to complete the shooting, forcibly put on pause as they were by Mohammadzadeh catching COVID — although that may have paid off as it helps him look almost like an entirely different person, plumper and healthier, when we see him in the plot’s deep past.

Despite any minor flaws, the film’s final bravura, deeply meaningful drone shot sends it out on a literally soaring high, fitting for a work of sly, ambitious accomplishment. For the record, the film’s international title Beyond the Wall is a poor substitute for the more evocative cinematic, screenplay-style language of its original Farsi title Shab, Dakheli, Divar, which means “night, interior, wall.”

0 notes

Photo

Amir Aghaei | امیر آقایی

No Date, No Signature | بدون تاریخ، بدون امضاء

#امیر آقایی#Amir Aghaei#Amir Aghaee#Amir Agha`ee#بدون تاریخ، بدون امضاء#No Date No Signature#بازیگر ایرانی#Iranian actor

0 notes

Text

Films from Iran and films from all over

By Loren King

GLOBE CORRESPONDENT

JANUARY 03, 2019

A highlight of every new year is the Museum of Fine Arts’s Boston Festival of Films from Iran, which for many years has brought varied and compelling works by contemporary Iranian filmmakers to local audiences. Running Jan. 17-27, it opens with writer-director Vahid Jalilvand’s “No Date, No Signature,” an international award winner and Iran’s entry for best foreign language film for the 2019 Oscars. It’s a taut, neorealist tale of guilt and morality in the tradition of groundbreaking Iranian filmmakers Asghar Farhadi and the late Abbas Kiarostami.

“No Date, No Signature” opens with a car accident, as forensic pathologist Dr. Nariman (Amir Aghaee) injures an 8-year-old boy in a minor collision with a motorcycle driven by the child’s father (Navid Mohammadzadeh). Despite Nariman’s insistence, the boy’s father refuses to seek medical attention. Later, at the hospital where he works, Nariman learns that the boy has been brought in for an autopsy after a suspicious death. A fraught reckoning ensues as Nariman and the boy’s parents wrestle with anger, responsibility, and shame.

“No Date, No Signature” won the best director prize, Mohammadzadeh took best actor honors, at the Venice Film Festival in 2017.

Another notable film is Milad Alami’s debut feature, “The Charmer,” a timely drama/romance/thriller that deals with the plight of Iranian immigrants. Esmail (Ardalan Esmaili), an Iranian struggling to remain in Denmark, is on a desperate quest to find a Danish woman who’ll agree to live with him before his visa runs out. After a series of failed liaisons, Esmail meets Sara (Soho Rezanejad), a law student eager to escape her oppressive Iranian mother and her mother’s circle of aging Iranian expatriates. As their relationship deepens, Esmail finds himself in an increasingly complex entanglement.

This year’s festival presents new films from Mohammad Rasoulof and Jafar Panahi, two of Iran’s leading filmmakers, who are barred by the Iranian government from making films. Rasoulof shot “A Man of Integrity” in secret in rural northern Iran while an as-yet unexecuted prison sentence hung over his head. Panahi’s “3 Faces” is the fourth movie he’s made in defiance of the government’s ban. The film won Panahi the best screenplay award at last year’s Cannes Film Festival.

Go to mfa.org.

Loren King can be reached at [email protected]

#boston globe#loren king#Boston Festival of Films from Iran#iran#vahid jalilvand#No Date No Signature#Asghar Farhadi#Abbas Kiarostami#amir aghaee#navid mohammadzadeh#Venice Film Festival#milad alami#the charmer#ardalan esmaili#soho rezanejad#mohammad rasoulof#jafar panahi#a man of integrity#3 Faces#cannes film festival#in english

0 notes

Text

Oscars: Iran Selects ‘No Date, No Signature’ for Foreign-Language Category

Iran has selected Vahid Jalilvand's psychological drama 'No Date, No Signature' as its submission for best foreign-language film at the Oscars.

BY Nick Holdsworth

Courtesy Of Venice Film Festival

Iran has selected Vahid Jalilvand’s psychological drama No Date, No Signature as its submission for best foreign-language film at the Oscars.

Iran has selected Vahid Jalilvand’s psychological drama No Date, No Signature as its submission for best foreign-language film at the Oscars.

Written and directed by Jalilvand, No Date tells a complex story of a forensic pathologist, Dr. Nariman (Amir Aghaee), who injures an 8-year-old boy in a collision with a motorcycle driven by the child’s father. The doctor’s offers of help are rebuffed, but soon after, at the hospital where he works, Dr. Nariman learns that the boy has been brought in for an autopsy after a suspicious death.

No Date, No Signature screened in the Horizons section at the Venice Film Festival in 2017, where it won the best director prize and best actor honors for its star, Navid Mohammadzadeh, who plays the father.

The Hollywood Reporter’s Venice review said that while the pic is “lensed with great sensitivity and style and superbly acted, it has one drawback for Western audiences in its perplexing plot points based on the local culture and customs.”

The decision, announced Friday by Iran’s Farabi Cinema Foundation, comes despite calls from some in the country to boycott the Academy Awards over the U.S.’ withdrawal from the Iran 2015 nuclear deal. The foundation, which selects Iran’s Oscar entry, said the Academy should not be confused with the U.S. government, stating: “The Academy is a non-governmental institution and belongs to American cineastes.”

It added: “American cinema, in particular the Academy members, in their attitude of mind, alongside the absolute majority of the U.S. press and media, are the main centers for opposition, criticism and divergence against [President Donald] Trump’s populism and his racist and despotic policies.”

Iran has submitted films for Oscar consideration often since 1994 and won the coveted statuette twice — for A Separation in 2011 and The Salesman in 2016, both by director Asghar Farhadi. In 1998, Majid Majid’s Children of Heaven made the final shortlist, but failed to win.

#Iran#Cinema#The Hollywood Reporter#Nick Holdsworth#No Date No Signature#بدون تاریخ، بدون امضاء#Vahid Jalilvand#وحید جلیلوند

0 notes

Text

Il dubbio - Un caso di coscienza

Il dubbio – Un caso di coscienza

Cinema: Il dubbio – Un caso di coscienza

Un’opera che si interroga su quanto l’occultamento della verità sia un veleno diffuso dagli effetti letali

(mymonetro: 3,00)

Consigliato: Sì

Regia di Vahid Jalilvand.

Con Navid Mohammadzadeh, Amir Aghaee, Hediyeh Tehrani, Zakieh Behbahani, Saeed Dakh, Alireza Ostadi.

Genere Drammatico

– Iran,

2017. Durata 104 minuti circa.

Kaveh Nariman è…

View On WordPress

0 notes