#70s japan

Text

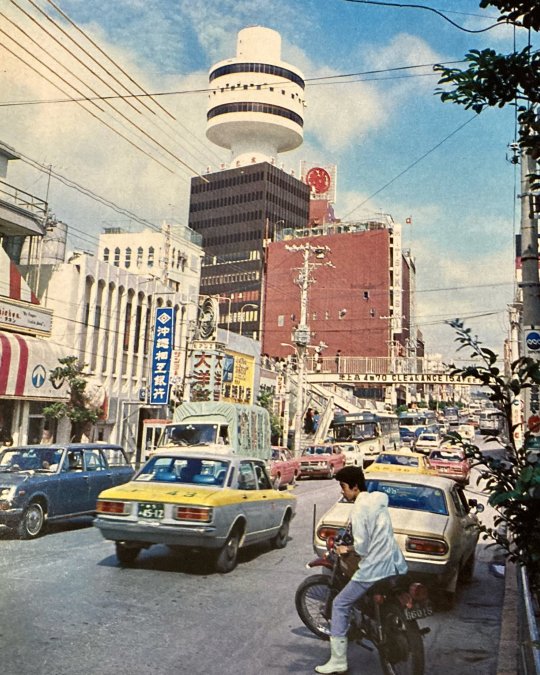

Hideo Yamashita, 1979

scan

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

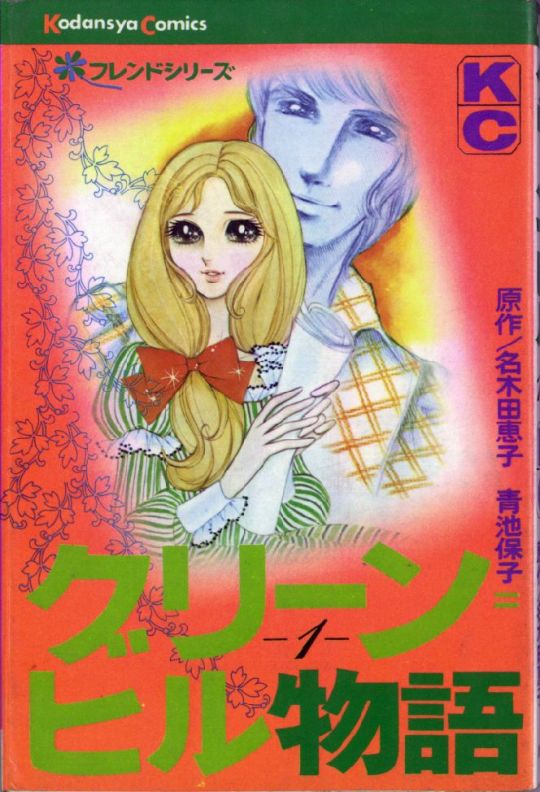

Green Hill Monogatari (1970) by Yasuko Aoike

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

#retro aesthetic#retrowave#retro japan#80s japan#70s japan#retro#honda civic#vintage cars#japanese cars#80s cars#70s cars#vintage advertising

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoujo Manga's Golden Decade (Part 3)

Shoujo manga, comics for girls, played a pivotal role in shaping Japanese girls’ culture, and its dynamic evolution mirrors the prevailing trends and aspirations of the era. For many, this genre peaked in the 1970s. But why?

Part 1

Part 2

Follow the Trend

Before we move on to the third movement of the '70s, let's take a quick look at an essential characteristic of shoujo manga: its sensitivity to trends.

The early '70s were a confusing time for the industry. There was extreme freedom in certain corners, with Yukari Ichijo, Machiko Satonaka, and other prominent artists drawing very adult-like drama in shoujo magazines for young girls. In contrast, there was also a lot of moralism. The fact manga wasn't taken very seriously meant magazines could get away with a lot since adults considered them terrible influences anyway. But, at the same time, since manga wasn't a respected medium, they were also prone to hysteria. Nothing illustrates this scenario better than the controversies surrounding "Harenchi Gakuen," the first full-length series by Go Nagai, who went on to become one of the most celebrated manga names in the '70s.

Shameless! The nudity and erotic jokes in Go Nagai''s "Harenchi Gakuen" were a hit with kids and teens, scandalized parents and teachers, and made the shoujo industry chase after their own erotic hits.

Nagai, already a respected yet fledgling name in the industry, was recruited by Shueisha to be part of Shonen Jump's inaugural team in the late '60s. Jump, as any manga fan knows, is by far the biggest success story in manga editorial history. However, back then, it was just a newcomer in a field dominated by Kodansha's Weekly Shonen Magazine and Shogakukan's Shonen Sunday. Go Nagai's series, whose translated name meant "Shameless High School," is Jump's first big hit and one of the titles that propelled the magazine to sell over 1 million copies.

But "Harenchi Gakuen," a gag manga with erotic jokes, scandalized adults across the nation. The Japanese Parents and Teachers Association successfully led a Shonen Jump boycott, getting the magazine banned in several shops across the country and triggering a media circus. At the time, agitated journalists often accosted Go Nagai at airports and public events, aggressively pointing their mics at him, a consequence of manga-kas celebrity-like notoriety during that era.

Meanwhile, the reaction around "Harenchi Gakuen" did not intimidate other manga magazines. In fact, all of them were pursuing their own "harenchi"-like phenomenon and publishing stories with erotic dirty jokes. And yes, that included the manga magazines for little girls. In Ribon, male manga-ka Hikaru Yuzuki was responsible for the "dirty" manga series. At Weekly Margaret, Yuzuki also had a considerable hit with the high school comedy "Elite Kyousoukyoku," which, while not precisely "ecchi," had a tone reminiscent of Nagai's work. At Nakayoshi, the artist in charge of this type of content was none other than a pre-"Candy Candy" Yumiko Igarashi.

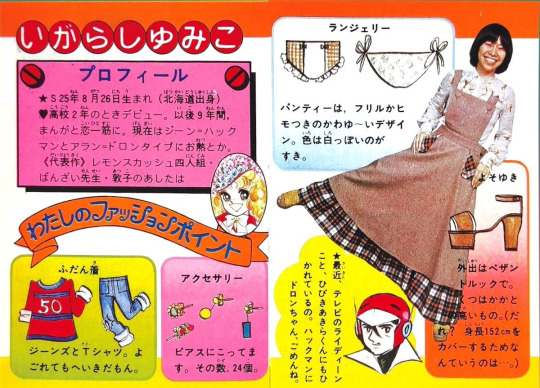

Before finding success with the smash hit "Candy Candy" manga, Yumiko Igarashi was the Nakayoshi artist in charge of recreating the "harenchi" phenomenon in the pages of the magazine. Above, in a good display of how public manga artists were in the '70s, Yumiko describes her panties as part of a Nakayoshi feature.

The "harenchi" phenomenon hinted at a shoujo field that wasn't yet wholly solidified and, therefore, was taking cues straight from the shonen segment, which would later become uncommon. But it is also an example of how the genre projects readers' dreams and preferences.

An example of this is one of Ribon's most popular series during the '70s, Yukko Yamamoto's "Miki to Apple Pie," a gag high school manga full of absurd humor and nudity in the "Harenchi" vein. The twist is that it also had everything girls dreamed of.

The "apple pie" in the title was a reference to the lead character's favorite dessert during the time the American apple pie had just arrived in Japan and was considered the trendiest sweet. Miki Miyazawa, a popular and beautiful girl who served as the proxy for readers and was loosely modeled after talento Aki Aizawa, also loved astrology and the horoscope, and the romantic lead was a transfer student named Hideki Nanjo, who was a carbon copy of Hideki Saijo, the biggest popstar heartthrob of the '70s. Basically, "Miki to Apple Pie"'s central premise was "What if the popstars girls go crazy for was your silly gorgeous classmate?".

In fact, a testament to Saijo's popularity was how many shoujo manga romantic partners of the era used him as a model. Besides "Miki to Apple Pie," inserts of him were present in Satonaka Machiko's "Spotlight," Shigeko Maehara's "Kimi Iro no Hibi," Mayumi Yoshida's "Lemon Hakusho," among others.

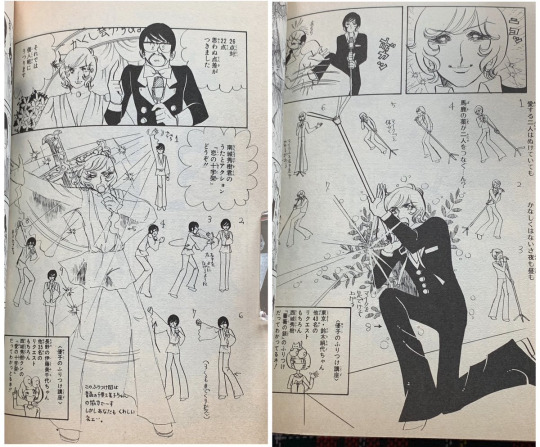

With nudity, slapstick humor, and a lot of reference to trends and pop culture, "Miki to Apple Pie" was a massive hit on the pages of '70s Ribon. The romantic lead, Hideki Nanjo, inspired by heartthrob Hideki Saiji, would often do impromptu performances of the pop hits of the times from famous stars like Agnes Chan, Finger Five and, of course, Hideki Saiji himself.

Saijo is a relic of the past, but shoujo echoing the trends of its time is a timeless characteristic of the genre. That's why most shoujo artists are women who are close in age to their readers: this sensibility to girls' desires is a vital component of the market. From the way the characters look to how they dress to even the shape of their eyebrows, everything is supposed to reflect its time. Therefore, to successfully create shoujo, one has to understand how girls perceive themselves and also how they want to be perceived. How they dress and look, but also how and what they dream of looking and wearing. What they aspire to and, above all, what they find attractive in the opposite sex.

It was precisely that sensitivity and this unique sense of what girls want and dream of that led to the creation of what is now the number 1 shoujo manga trope: the high school romance starring an unassuming, ordinary heroine. Leading the way was another group of artists that, while not as internationally celebrated as the Year 24 Group, are definitely equally as crucial to shoujo history.

The Otometique Fervor

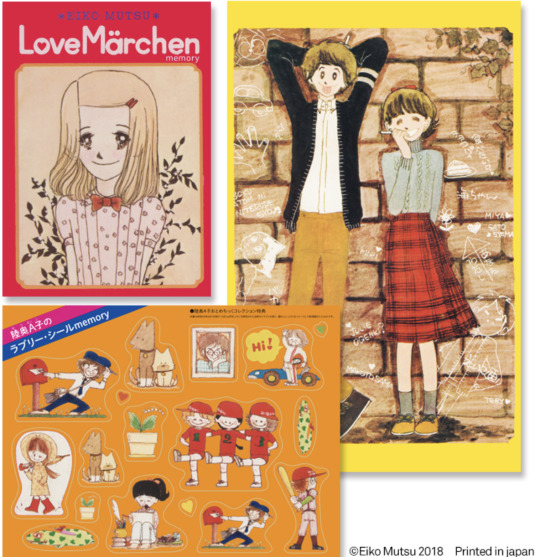

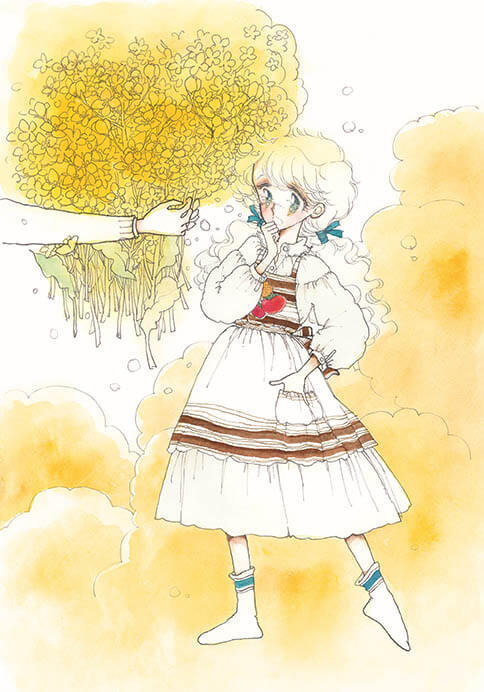

An "otometique" girl by Mutsu A-ko and some of the artist's popular furoku.

Yoshiko Nishitani, another of Shueisha's top shoujo artists of that era, is often credited as being the first to create a series around ordinary high school love. She did that in 1965's "Marie Lou," published in Weekly Margaret. "Marie Lou" was set in an American high school and had a very fashionable white girl as its lead. On her next manga, "Lemon to Sakuranbo" (Lemon and Cherries), she'd once again achieve immense success by bringing the teen romance closer to reality, using an ordinary Japanese high school as a backdrop.

While Nishitani pioneered this narrative style, the rise of more realistic, everyday stories gained momentum about a decade later. One catalyst for this was the "Otometique boom," a phenomenon that unfolded in the pages of Shueisha's Ribon magazine in the latter half of the '70s.

The term "Otometique" combines "otome," meaning "maiden" or a pure young girl, with the "-tique" (tikku in Japanese) suffix. A-ko Mutsu was the artist who spearheaded this movement.

A-ko made her debut in Ribon in 1971 at the age of 18. Her popularity skyrocketed four years later when her first short stories, led by "Tasogaredoki ni mitsuketa no" (What I Found at Twilight), were compiled into a tankobon that became a best-seller. This success elevated her status in Ribon, and soon her "otometique" style became the talk of the town.

Mutsu A-ko's art.

In contrast to the dramatic narratives of the "Satonaka-domain" faction, "otometique" stories adopted a more straightforward structure devoid of major plot twists and intense drama. Instead, they focused on modest love stories where the exhilarating moments were ordinary occurrences, like spotting a cute boy on the street or touching a crush's hand for the first time. While some stories included sad or supernatural elements, readers were captivated by the uncomplicated, heartwarming moments.

Ako's heroines were ordinary, unassuming schoolgirls, often characterized by shyness and insecurity. Different from extraordinary characters like Lady Oscar from "BeruBara" or the iconic Madame Butterfly tennis star in "Ace wo Nerae," Ako's protagonists were life-sized.

"Otometique" manga often incorporated romantic comedy tropes, such as chance encounters with cute guys on the way to school or the transformation into beauty after removing glasses. The happy endings typically featured a boy reciprocating the girl's love by accepting her as perfect and beautiful just as she was.

In otometique manga, girls were often in cute plaid and gingham check dresses and skirts, while boys were impeccably dressed in Ivy style, as seen in Mutsu Ako's art above.

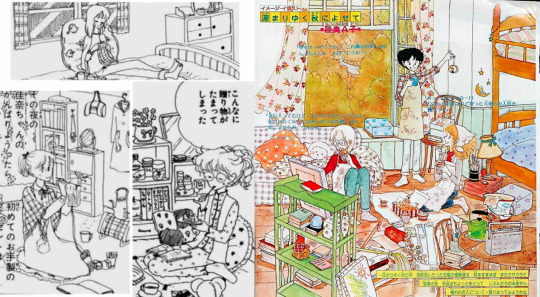

While the stories may have seemed mundane, their distinctiveness lay in the meticulous attention to detail. As significant as the exploration of falling in love and discovering inner strength were all the visual details in "otometique" art. Girls had braids or long wavy hair and wore adorable clothes with plaids and gingham-check, as well as cute accessories. At a time when most Japanese girls still had Japanese-style rooms, "otometique" heroines had gorgeous Western-style rooms. They hung out in cozy cafes, made handmade goods, and ate tasty-looking sweets. Houses had French windows and balconies. Boys were tall, lean, with fluffy hair, and were always dressed impeccably in Ivy-style clothes. The "otometique" artists created an atmosphere that perfectly matched girls' aspirations at the time.

Girls often dreamed with having Western-style bedrooms like the ones in Otometique manga.

While Mutsu A-ko was the trailblazer, she was soon joined at the top by two other iconic artists, Yumiko Tabuchi, and Hideko Tachikake. Each of them had their quirks. Tabuchi, for example, often had college girls as her heroines, mirroring herself as a student at the elite, trendy Waseda University. While Tabuchi and A-ko preferred short stories, Tachikake had a penchant for longer series with a bit more drama. But they all had a similar aesthetic and relied on ordinary stories about love.

The "otometique" phenomenon reflected the trends of the time and foreshadowed the emerging consumer culture that would swallow the country in the next decade. The sophisticated visuals attracted people of all ages, from elementary school-aged girls to highly educated women and men. Both the top public and private universities in Japan, Tokyo University and Waseda, respectively, had famous "otometique" clubs full of students who loved the genre and the style. The mangas were so trendy they were often referred to as "Ivy mangas," in reference to the iconic Ivy style that was the catalyst of Japan's youth fashion which was going through a second revival around that time.

While projecting an atmosphere that girls dreamed of, "otometique" also showcases '70s youth and girls' culture. Melancholic, simple love stories among young people were also the theme of the big folk hits of the time. Ivy or country fashion and long hair for men were the trends. Western-inspired ideals- in decoration, fashion, and musical taste- were pervasive. And creating subcultures and hobbies around consumption was the path society was taking. Simple life-sized stories as a narrative preference echoed the reality of Japan, which was stabilizing itself after decades of turbulence. These stories brought what the country was craving: comfort.

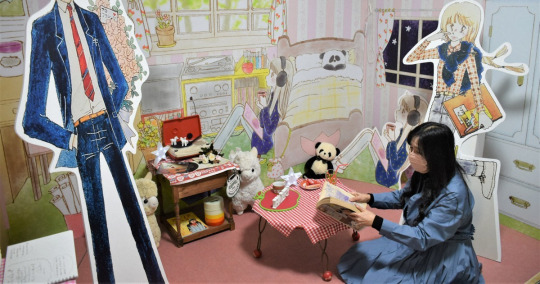

Above, a Mutsu A-ko's bedroom that lived in girls' imagination. Below, the room is recreated in a 2021 exhibition of Ako's art.

Meanwhile, the rise of consumer culture among young girls led to a "fancy goods" boom, with stores selling cute stationery, stickers, and small items popping up everywhere around the country. Illustrators and companies, eager to capitalize, spared no time in creating appealing mascots and drawings to adorn these goods, and it was in that period that Sanrio created Hello Kitty.

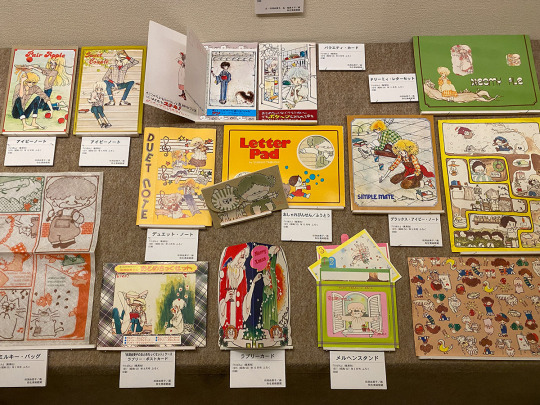

Ribon and Nakayoshi, which were "furoku" magazines, also benefitted. Furoku are extra gifts that come with the purchase of the magazines. And the "otometique" boom meant Ribon could include "fancy goods" -- like notebooks, stickers, letter sets, and small paper goods readers could assemble -- with the illustration of these highly sought-after artists. Most girls around Japan could only dream of Western-style rooms, a closet full of cute Ivy fashion, trips to trendy cafes, and homes with French windows. But they could recreate a bit of this sophisticated atmosphere by having letter sets, notebooks, stickers, and small accessories with A-ko Mutsu, Hideko Tachikake, and Yumiko Tabuchi's art. These popular furokus and the "otometique" stories were critical for Ribon magazine to surpass 1 million copies in circulation.

Girls admired A-ko, Tabuchi, and Tachikake not only as artists creating heartfelt stories with attractive atmospheres but as personalities. The trio, who were in their late teens and early 20s, closely resonated with their fans due to their proximity in age and shared interests. The readers were moved when Ribon featured an article in which A-ko Mutsu had the opportunity to meet and interview her favorite singer, the rock star Kenji Sawada, a prominent teen idol of that era. The positive response was so overwhelming that, a few issues later, Hideko Tachikake, an avid folk music enthusiast, also had the chance to interview her idol, Kosetsu Minami, the lead singer of Kaguyahime.

An otometique girl by Yumiko Tabuchi (left) and a collection of furoku illustrated by her as seen on a 2021 exhibition on her art.

The popularity of "otometique" peaked in 1977. By 1981, the boom had almost faded, and Ako, Tabuchi, and Tachikake published their last work on Ribon in 1985. Tabuchi and Tachikake married and semi-retired, while Ako successfully transitioned to manga for adult women.

Despite the end of the style, "otometique" permeated every corner of Japanese society. Its furoku and atmosphere were one of the bases for the almighty "kawaii" culture which now rules the country. The life-sized heroines and focus on mundane love stories and everyday emotions went on to become one of the main characteristics of the shoujo manga industry.

The Iwadate Domain

For years, the influence of "otometique" has been downplayed, one of the reasons why the movement is almost undiscussed in the West. However, in the last few years, best-selling books reminiscing the style were published, and exhibitions of A-ko Mutsu and Yumiko Tabuchi's works were big hits across Japan. Ako, who moved back from Tokyo to her hometown in Fukuoka and never stopped working on manga, was recognized by the local prefecture as an honorary citizen and gained a permanent museum in the area, signaling her importance to the industry.

But while the "otometique" phenomenon happened on the pages of Ribon magazine, Mutsu, Tabuchi, and Tachikake weren't the only three attracting a massive audience to this type of real-life love story.

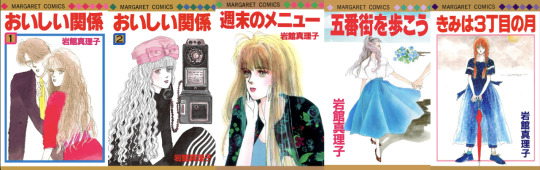

Mariko Iwadate's work was extremely popular from the late '70s to the mid-2000s. Above, a collection of her work from her Margaret era.

Going back to the research of sociologist Shinji Miyadai, three domains divided '70s shoujo. There was the "Moto Hagio domain," which included the Year 24 artists. The Hagio domain was more highbrow and intellectually challenging, and many considered it an equivalent to literature, attracting the intellectual elite that sniffed at manga in general. It is by far the most discussed and debated '70s shoujo movement, as well as the most famous in the West, but it was the least commercially successful at the time. Then there was the "Machiko Satonaka domain," with emotionally driven stories full of drama, plot twists, and larger-than-life heroines. Most of the '70s best-selling shoujo series fall under this category, which includes the work of Yukari Ichijo and Ryoko Ikeda and sports manga like "Ace wo Nerae," among others.

Finally, there's the domain in which the "otometique" stories were created. And Miyadai doesn't name it after any of the Ribon artists, calling it the "Mariko Iwadate domain" instead.

In the Satonaka domain, the heroine served as a proxy for the reader in a fantastical world, while in the Iwadate domain, the heroine represented the reader in the real world. But who is the influential Iwadate?

Mariko Iwadate, who made her debut in 1973 at the age of 16, rose to prominence by embracing the "otometique" style during its peak in the late '70s. Similar to Ribon artists, Iwadate captivated readers with her elegant and stylish art, featuring cute clothes, accessories, and intricate details.

Miyadai's choice to name the category after Iwadate rather than the genre pioneer Ako Mutsu may be attributed to Iwadate's sustained success. After leaving Ribon in 1985, Ako remained prolific but couldn't replicate her peak, while Iwadate continued her success even after she transitioned to adult women's manga. Iwadate's work, recognized for its emotional depth, became a significant inspiration for trailblazers like best-selling novelist Banana Yoshimoto and avant-garde manga artist Kyoko Okazaki. In 1993, when Miyadai wrote his book, Iwadate's fame and respect probably made her a more recognizable figure for readers to associate with the category.

Iwadate's soft girly art and story-telling made her extremely popular and influential.

Mariko Iwadate's narrative, especially her post-80s work, has a more psychological and mature element to it when compared to Ribon's artists. She, as an artist, bridged the gap between "otometique" and another highly influential "Iwadate domain" artist, Fusako Kuramochi.

Fusako Kuramochi, debuting while still a teen in the early '70s at Bessatsu Margaret, initially emulated her favorite artists, Moto Hagio and Keiko Takemiya, before finding her style—a realistic portrayal of romance with a substantial psychological element. Her success contributed to shaping Betsuma, alongside Ribon, as arguably the most influential and commercially thriving shoujo title -- the go-to magazine for high school romcom.

Like the otometique artists, Fusako Kuramochi first gained prominence with short stories and one-shots. In 1979, she wrote her first series, "Oshiaberi Kaidan," in which each chapter depicted the life of a young girl from junior high to her graduation day. In 1980, she published "Itsumo poketto ni Chopin," a classical music manga that was also about growth. From then on, she'd publish about two hit series every year in Betsuma before graduating successfully to adult women's manga in 1994.

Kuramochi's success was due to her great skill in portraying girls going through crushes, heartbreaks, and jealousy. The psychological elements struck a chord with readers and helped her create male romantic leads that were extremely popular.

Another component of Kuramochi's work was her sophistication, a result of her upbringing. Her father was the chairman of one of Japan's biggest printing companies, and she was raised in Shibuya, in the center of Tokyo, while attending an exclusive all-female institution. The fact she spent her youth in the middle of Tokyo's hustle and bustle meant she knew the capital well, and her works were full of references to trendy cafes, restaurants, nightspots, and neighborhoods. Her Betsuma work was published right before, and during Japan's luxurious Bubble years, so many chasing an exciting city life referred to her mangas.

While her Betsuma work reflected the reality and aspirations of the Bubble years, Kuramochi's true gift lay in providing readers with a realistic depiction of growing up and falling in love, making her stories immensely popular. In general, consumerism -- displayed through clothes, accessories, and decor -- isn't as crucial to her success as the three Ribon "otometique" artists.

While Fusako Kuramochi is part of the "Iwadate domain," you can argue that Kuramochi evolved into her own category, which was vital for the development of real-life love stories in shoujo in the '80s and '90s and the rise of other highly-influential artists like Ryo Ikuemi.

But going back to the three '70s movements, "otometique"/"Iwadate domain" was definitely the most influential one in steering shoujo manga in its current direction. On the other hand, all of these domains co-existed together and fed from each other. In 1977, during the "otometique" boom, Yukari Ichijo remained untouched as one of Ribon's most popular artists with her emotionally charged dramas. It was the success of Ichijo and other "Satonaka domain" artists that allowed the "Hagio domain" to debut and take risks. In turn, it was the "Hagio domain" that showed there were rewards for young risk-taking shoujo artists.

Yumiko Oshima, known for her girly art and sensitive story-telling, is the inspiration behind the otometique boom.

When asked which artist inspired them the most, both Ako Mutsu and Mariko Iwadate gave the same answer: Yumiko Oshima. Oshima, known for her quirky love stories and girly art, is an artist who trained alongside Hagio and Takemiya at the Oizumi salon and rose as part of the "Year 24 group," publishing risk-taking manga in Shogakukan and Hakusensha's magazine after a brief stint in Weekly Margaret. In other words, despite the striking differences, the origin of the "Iwadate domain" is the "Hagio domain."

While the influence of the idealized real-life romance is the one we can better observe today, contemporary shoujo would not exist if not for all these three styles meshing together and creating something new. And from that, things kept evolving and changing and gaining new forms. Because, once again, manga, and especially shoujo manga, is about reflecting the ideals of its time.

#ribon#margaret#go nagai#miki to apple pie#yumiko tabuchi#otometique#otometique manga#mutsu a-ko#mutsu ako#hideko tabuchi#70s japan#fusako kuramochi#betsuma#shoujo manga#vintage shoujo#vintage manga#harenchi gakuen#yumiko igarashi#nakayoshi#yumiko oshima

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lullaby Lovables (1976)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

House - 1977 - Dir. Nobuhiko Obayashi

#t shirt#movie#hausu 1977#hausu#house#house 1977#tie dye#tiedye#1977#70s#70s horror#j horror#70s japan#ハウス#emperimental#Nobuhiko Obayashi#Chigumi Obayashi#Chiho Katsura#Kazuo Satsuya#Asei Kobayashi#horror#comedy#horror comedy#studiohouse designs#House - 1977 - Dir. Nobuhiko Obayashi

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Haunted Turkish Bathhouse (1975)

『 怪猫トルコ風呂 』

Directed by Kazuhiko Yamaguchi 山口和彦

#a haunted turkish bathhouse#怪猫トルコ風呂#Kazuhiko Yamaguchi#山口和彦#horror#horror movies#japanese horror#pinku#pinku eiga#j-horror#j horror#horror cinema#japanese film#japanese movies#1975#70s japan#70s cinema#halloween#screencaps#cinematography#yokai#bakeneko#bakeneko movies#japan film club

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Douzo Konomama (どうぞこのまま, Please Keep it So) (1976) - Keiko Maruyama (丸山圭子). This song is the third song on Keiko Maruyama's second album, Tasogare Memory or Twilight Memory (黄昏めもりい), released on 5 March, 1976 under the label King Records and composed by Keiko Maruyama.

This song is Maruyama-san's biggest hit. The genre of this song is generally bossa nova, pay attention to the electric piano, it's very jazzy. A perfect song to listen to at night in a bar while drinking cocktail in the late 1970s. This song was also covered by many other singers like Mayo Shono, Hiromi Iwasaki and Mizue Takada.

Media Source:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FS521HcVK04

#city pop#city pop japan#city pop music#city pop songs#city pop song#japanese city pop#japanese songs#japanese song#japanese music#70s songs#70s song#70s music#1970s songs#1970s song#1970s music#1970s#1976#70s japan#1970s japan#bossa nova#jpop#j pop#keiko maruyama#丸山圭子#douzo konomama#70年代#日本の歌#日本の音楽#シティポップ#70s

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

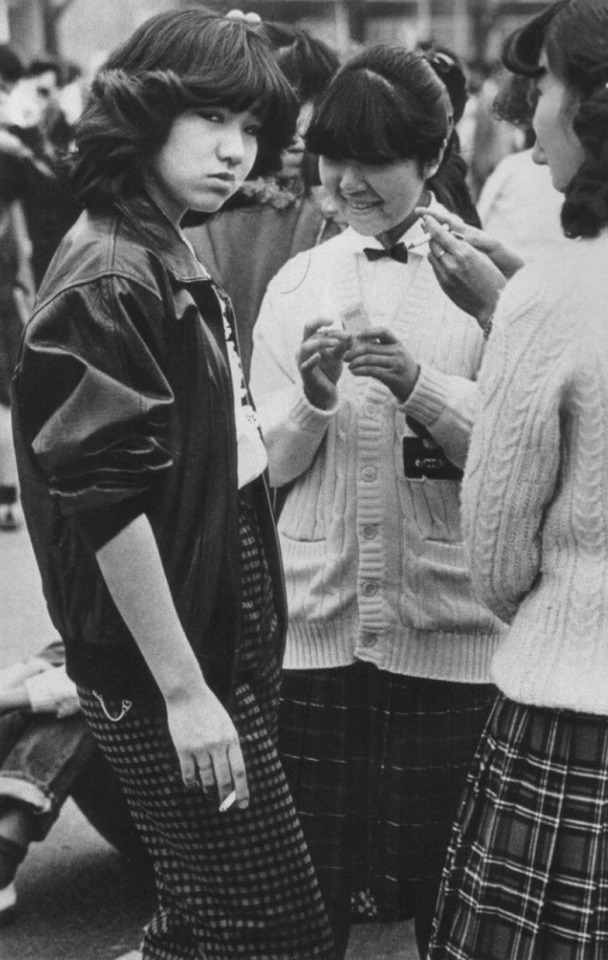

Girl gang, 1970s.

392 notes

·

View notes

Text

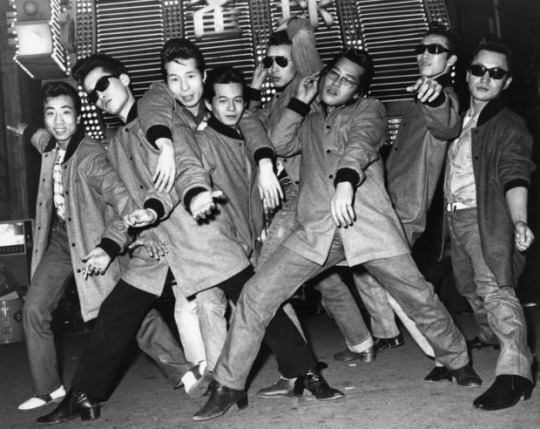

Some of my fave pics by Seiji Kurata. <3

#japan#vintage japan#1970s#70s fashion#photography#black and white#vintage#vintage photography#70s japan#tokyo#tokyo fashion#seiji kurata#flash up

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

70s Japan Trends Through the Music Charts (Part 2)

During the 1970s, the Japanese music industry was in the process of forming its identity. In addition to mirroring the musical preferences of the nation, the charts also served as a reflection of the prevailing societal trends and ambitions of that era. In this series, we chronicle the most significant musical trends of the decade.

70s Japan Trend Through the Music Charts (Part 1)

Trend #4: The Impact of Discover Japan

In 1970, Osaka hosted the World Expo, marking a significant milestone for post-war Japan following the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. To accommodate the influx of visitors, the government expanded the rail network, enabling over 60 million people—half of the nation's population—to journey to the World's Fair. However, as the Expo drew to a close after six months, concerns arose about the railways becoming obsolete. So, with the help of the ad agency Dentsu, they devised a campaign to stimulate domestic tourism by rail. The result was "DISCOVER JAPAN," one of the most iconic campaigns of the decade (which, curiously, was partially inspired by Ivy Fashion brand VAN).

"DISCOVER JAPAN" profoundly impacted Japanese society by popularizing solo travel and igniting domestic tourism, particularly among young women who ventured out on their own. This trend was further fueled by the launch of the first female fashion magazines, AnAn and Non-no, both of which extensively covered visits to charming cities across the country. Cities known as "Little Kyoto," which retained their Edo Period architecture and charm, were particularly attractive to these travelers.

Influenced by fashion magazines, these trend-conscious women journeyed to small cities throughout Japan, earning them the moniker "AnNon" (a fusion of AnAn and Non-no). Their impact during the 1970s was significant enough to be mentioned in a song by Sada Masashi, one of the decade's prominent folk singers.

"DISCOVER JAPAN," the print and TV campaign devised by Dentsu, is one of Japan's most successful and era-defining marketing campaigns.

Sada Masashi rose to fame in the early 1970s as part of the folk duo Grape before launching a successful solo career. In 1977, his song "Ehagakizaka," which paid tribute to his hometown of Nagasaki, mentioned identically dressed stylish young girls in denim, clutching AnAn and Non-no magazines while photographing their surroundings. This song vividly captured the aspirational girl culture of the 1970s, characterized by "healing" domestic trips in pursuit of tranquility and small pleasures, hippie and boho-inspired fashion, and folk music as the soundtrack.

Masashi Sada's song and the AnNon-zoku tribe aside, "DISCOVER JAPAN," had an immense impact on different layers of Japanese society. And that included the music charts. In 1971, the two best-selling singles, "Watashi no joka-machi" by Rumiko Koyanagi and "Shiretoko ryojou" by Tokiko Kato, surpassed 1 million copies sold. Both perfectly embodied the campaign's spirit in highlighting the hidden beauties of Japan.

"Watashi no jokamachi," or "My Castle Town," marked Koyanagi's explosive debut, selling over 1.3 million copies. This enka-infused kayokyoku ballad paid homage to cities with Edo-like architecture, often centered around a feudal lord's castle, evoking a peaceful, melancholic atmosphere in its lyrics. Rumiko continued to sing about regional Japan's charms the following year with another hit, "Seto no Hanayome" (The Bride of Seto). Meanwhile, the folk-inspired "Shiretoko ryoujou" (Shiretoko Journey) celebrated the unique beauty and culture of the Shiretoko peninsula on Hokkaido Island.

In the same year, other artists also succeeded by spotlighting provincial Japan. Enka superstar Shinichi Mori delved into this theme with "Boukyou" (Nostalgia). At the same time, Yuuko Nagisa found success with a Japanese rendition of The Ventures' "Kyoto Doll," titled "Kyoto no Koi" (Love in Kyoto). She would go on to have another top-selling single with her version of another Ventures song, "Reflection in Palace Lake," transformed into "Kyoto Bojo" (Kyoto Longing).

Trend #5: The Legend of Momoe Yamaguchi

"Aidoru" or "idols" are cute girl/boy-next-door types who sing, dance, act, host TV shows, and star in countless commercials. They stand as one of the cornerstones of the thriving multi-billion yen Japanese entertainment industry. The 70s was an essential era for consolidating this type of star. And one idol, in particular, shone the brightest: Momoe Yamaguchi.

Momoe is a legendary star and an example of an "aidoru" who excelled at everything, exuding sophistication, talent, and sex appeal. The fact she retired from public life at the height of her fame cemented her mythical status.

Momoe Yamaguchi in her prime, the idol industry's gold standard.

In 1972, at the tender age of 13, Yamaguchi auditioned for the talent search TV show "Star Tanjou!" (A Star is Born). Her crisp singing voice and mature beauty immediately captured the industry's attention. Hori Production, the entertainment agency, and Sony CBS label swiftly recognized her potential and signed her. In May 1973, five months after her televised audition, she made her official debut with the single "Toshigoro" (Adolescence). Although Sony had a history of immediate success with newcomers, Momoe's first single received a tepid response, so her label decided to court a bit of controversy for her sophomore outing. "Aoi kajitsu" (Ripe Fruit) had the innocent-looking 14-year-old girl singing, "you can do whatever you want to me, even if they say I'm a bad girl." The racy lyrics worked, and the single was a success.

A few months later, Yamaguchi's backers repeated this formula with "Hito natsu no keiken" (One Summer Experience). The song began with a suggestive promise: "I'll give you the most precious thing a girl has." The lyrics were laden with double entendres, describing a "sweet trap of temptation" that can only be experienced once. She sang, "if the person I love is pleased, then I'm happy. I don't mind if you break it," which could be understood as a reference to a girl's hert or hymen.

The single was an explosive hit, propelling 15-year-old Yamaguchi into the A-list. For the remainder of her career, she was frequently asked about the "most precious thing a girl has," to which she'd always offer a stern-looking reply: "her devotion."

The young, mature-looking girl singing thinly veiled songs about sexual awakening with a dark, serious-looking image set her apart from the prevalent happy-go-lucky idol aesthetic. However, it wasn't merely reliance on gimmicks that transformed her into a legend. In 1976, after firmly establishing herself as a star, she parted ways with her frequent collaborators, lyricist Kazuya Senke and composer Shunichi Tokura. Beginning with the single "Yokosuka Story," she partnered with the husband-and-wife duo Yoko Aki and Ryudo Uzaki.

Ryudo Uzaki, the frontman of the popular enka rock band DOWNTOWN BOOGIE WOOGIE BAND, infused her kayokyoku tunes with a rock edge. Through her lyrics, Yoko Aki redefined Momoe's image as a confident, clear-eyed girl transitioning into womanhood. Initially, Sony opposed Momoe's desire to collaborate with Aki and Uzaki, but the partnership ultimately helped her reach her commercial peak.

"Yokosuka Story" was Momoe's first single to reach the number 1 spot on the weekly charts. The Aki-Uzaki duo penned several other hits for her, including "Playback Part 2" and "Sayonara no mukougawa" (The Other Side of Goodbye), and opened doors for her to collaborate with other luminaries of Japanese music. Two of her most memorable hits, "Cosmos" and "Ii hi tabidaichi" (Beautiful Day Departure), both released in 1978, were penned by folk superstars Masashi Sada and Shinji Tanimura of Arisu, respectively. The latter became the theme song for the iconic DISCOVER JAPAN TV commercials.

Speaking of commercials, idols worth their salt can't limit themselves to music. Momoe earned millions being the face for Toyota cars, Fujifilm photographic films, Casio watches, and Glico confectionary products, among others. She also starred in highly-rated TV dramas and ventured into the world of film.

Starting in 1974, she appeared in two romantic films per year, always paired with Tomokaza Miura as her co-star. While Momoe pursued various ventures, Miura's acting career primarily revolved around being her on-screen romantic partner. Their undeniable chemistry and the box-office success of their films led to them being known as the "golden combination."

In a concert at the end of 1979, Momoe stunned her audience by revealing that her on-screen partner, Miura, was her real-life boyfriend. In a subsequent press conference in March of the following year, she confirmed her intention to marry him and retire officially. In September, she released her autobiography, which sold over 1 million copies in a month. In October, she bid farewell through a series of TV specials and a concert at Nippon Budokan. Her farewell concert reportedly earned Hori Productions over 20 million dollars, according to figures provided by the agency to Billboard magazine at the time. Momoe's success allowed HoriPro to become one of the best-established entertainment agencies in Japan, a position it still holds today. Her final performance took place at HoriPro's 20th-anniversary event, where she sang "Ii hi tabidaichi." In November, she married Miura and disappeared from the media.

The Japanese public obsession with her never waned. Paparazzi tried to capture her at her son's kindergarten graduation ceremony and doing classes at a local driving school. Many speculated she'd eventually come out of retirement. She never did, which only helped feed the obsession around her.

During the 1970s, Yamaguchi enjoyed immense success, but she was one of many popular female idols. The narrative created by her retirement elevated her to the status of a larger-than-life legend. She became the gifted, beautiful young woman who succeeded as a singer, a TV actress, and a movie star before choosing the ultimate happy ending: marriage. By choosing love, Momoe Yamaguchi, the legendary idol, transformed into an ordinary woman—a real-life fairy tale that resonated deeply with Japanese society.

Her decision was driven by profound motivations. Momoe revealed in her autobiography that she was raised by a single mother, the product of an extramarital affair. Her challenging upbringing and her father's late appearance to capitalize on her fame instilled a deep desire for a traditional, happy family life. She also grew weary of the relentless demands of stardom and the repetitiveness of performing the same songs. Thus, she made a heartfelt choice to relinquish fame and public life to give her husband the most important thing a girl has: her devotion.

Trend #6: Idols' Rise

The term "idol" in the Japanese entertainment industry finds its origins in the French film "Cherchez l'idole" (1963), which enjoyed immense popularity in Japan. Initially, "Aidoru" was used to describe the film's star, Sylvie Vartan, before it evolved into a general term to describe youthful-looking triple-threat domestic stars.

Before the coining of the term, "idol-like" stars had already existed. In the 1930s, Machiko Ashita attracted crowds to the Moulin Rouge Shinjuku and served as the face of several brands. In the 1950s, rockabilly stars enjoyed massive popularity among the youth, and the 1960s saw the rise of manufactured "group sound" bands and the female duo The Peanuts, comprised of twin sisters. Legendary stars such as Hibari Misora, Sayuri Yoshinaga, Teruhiko Saigo, Yukio Hashi, and Kazuo Funaki thrived as both movie stars and successful singers.

However, the 70s marked the consolidation of the "idol" aesthetic and career path, paving the way for the "golden era of idols" in the next decade. Essential for it to happen was the widespread adoption of the medium where idols shine the brightest: television.

TV allowed entertainment agencies to aggressively push their young, fresh-faced talents in front of a broad audience. They populated music and variety shows, commercials, and dramas. They were immaculate, life-sized stars ready to play the part of the nation's sweethearts.

Although history has crowned Momoe Yamaguchi as the ultimate 70s idol, she was just one among many during most of that decade. A closer examination of the numbers reveals that Mari Amachi, a female idol, had the most significant short-term impact during that time.

Amachi was first introduced on the popular TBS TV drama "Jikan desu yo" (It's Time) in 1971, playing "Tonari no Mari-chan" (Next Door Mari-chan). She played the minor role of a cute girl who lived close to the show's primary setting, a family-run public bathhouse, and often appeared by her window, playing guitar and singing. By October, with the backing of the biggest entertainment agency of the era, Watanabe Production, and Sony CBS, 19-year-old Mari Amachi officially debuted with the single "Mizuiro no Koi" (Light Blue Love). It was a hit—the first of many. Mari would be 1972's best-selling act, achieving high sales with four albums and five singles.

Mari's image, characterized by an innocent aura, a happy-go-lucky personality, and frilly dresses as stage outfits, became the prototype for female idols. Her short hair and chiseled smile earned her the nickname "Sony's Snow White," evoking the image of a fairytale princess. Unsurprisingly, she was particularly popular with children, leading Watanabe Pro to license her likeness for various goods, including the coveted "Do-Re-Mi Mari-chan" Bridgestone Cycle bicycle, highly sought after by young girls in the early 70s.

Despite her rapid rise to fame, Mari's time at the top was short-lived. By 1974, another Watanabe Pro idol, Agnes Chan, was already surpassing her in sales. In 1977, Mari's health deteriorated, and she took a lengthy hiatus, officially attributed to thyroid issues but later revealed to be depression triggered by her waning popularity. In 1979, she attempted a comeback, even bagging an endorsement deal for an ultrasonic facial device, one of the year's hit items for women. But her time had passed and she didn't find much success. Eventually, Mari's career took unconventional turns, including involvement in a softcore porn movie, the release of nude photobooks, and a transition to becoming a "fat" talento (TV personality), followed by a weight-loss book.

In 2015, in her last public interview, she revealed that, at 63, she was living in a retirement home in the Tokyo suburbs. Her fan club covered her expenses, while her daughter provided a modest weekly allowance. This marked a stark contrast to her glamorous peak years and serves as a reminder of the challenges idols face in the Japanese entertainment industry, particularly women, and how easily discardable idols can be. It also shows how wise Momoe Yamaguchi was, bowing out gracefully at the right time.

However, Momoe Yamaguchi and Mari Amachi represent two extremes within the realm of idols. While Mari achieved record profits for two years before facing decline and eventual obscurity, Momoe maintained relevance for nearly a decade before choosing to marry her on-screen partner, retire, and become a living legend. Most other 70s idols did not experience such remarkable destinies.

In 1971, two other young idols, Rumiko Koyanagi and Saori Minami, made their debut alongside Mari Amachi. The trio was collectively known as the "shin sannin musume," or the "three new girls." Their joint concert at the Budokan on Christmas of 1972 solidified their shared nickname.

The Shin San-nin Musume. Clockwise: Rumiko Koyanagi, Mari Amachi, and Saori Minami.

Rumiko Koyanagi had her skills honed at the Takarazuka Music School. Takarazuka is a very traditional, all-female theater group, and their training academy is known to be highly rigorous and selective. Koyanagi graduated top of her class but wanted something other than a musical theater career. Instead, her goal was to debut as a solo singer. So she left the Takarazuka Revue and signed with Watanabe Pro and Warner Pioneer label to fulfill her dream. Her first song, "Watashi no joka-machi" (My Castle Town), buoyed by the "Discover Japan" boom, surpassed 1 million copies sold, becoming the best-selling single of 1971.

Rumiko's repertoire predominantly featured enka-influenced kayokyoku. Her classical sound may not have been as appealing to the youth as some of her peers' slightly more modern tunes, but it ensured her stable sales throughout the decade. In her sixties, Rumiko has reinvented herself as a passionate soccer fan and a glamorous senior lady, sharing lifestyle tips and her love for Chanel and Lionel Messi on Instagram. She also conducts dinner shows, a lucrative type of intimate concert usually held at luxury hotels, where fans pay hefty prices to enjoy a multi-course dinner while listening to nostalgic hits.

The third "shin sanin musume" is Saori Minami. Minami didn't have a million-selling debut like Rumiko, nor did she become an instant sales behemoth like Mari. That didn't mean she was less impactful. Quite the opposite. Hailing from Okinawa, still under US occupation during her debut, Saori impressed Japan with her exotic beauty. In 1971 and 1972, she outsold every other female idol in bromide sales. Bromide is the local terminology for photographic portraits of celebrities, and historically, its sales are the best way to gauge how popular an idol is.

Her first single, "17-sai" (17 years old), became a classic and enjoyed enduring popularity, with several artists covering it over the decades. After retiring in 1978 upon her marriage to legendary photographer Kishin Shinoyama, Saori made a comeback in 1991 but has made only sporadic public appearances since then.

Two years after the emergence of the "shin sannin musume," a new trio of newcomers known as the "Hana no Chuusan Trio" or the "Chuusan's Flower Trio" (a reference to the fact all of them were in Chuusan, the third year of middle school) came into the spotlight. Masako Mori, Junko Sakurada, and Momoe Yamaguchi were all revealed in the talent search TV show "Star Tanjou" (A Star is Born). In 1975, by the time they were in their second year of high school (kou 2), they co-starred in the successful film "Hana no Kou 2 Trio."

The Hana no Chuushan Trio: Momoe Yamaguchi, Junko Sakurada and Masako Mori.

At 13 years old, Masako Mori secured her place as the inaugural "Star Tanjo" grand champion in 1971. The following year, she debuted under Hori Production and swiftly soared to success. Mori's music was deeply influenced by enka, and by the close of the decade, she had solidified her status as a fully-fledged enka star. In 1986, she tied the knot with enka superstar Shinichi Mori, leading her to retire from the entertainment scene. However, in 2005, following her divorce, the former idol made a comeback, embarking on tours and participating in TV dramas for a few years before ultimately deciding to bid farewell to her career once more on her 60th birthday in 2019. Notably, she shares three children with Shinichi Mori, including TAKA, the lead vocalist of the popular rock band ONE OK ROCK.

Junko Sakurada clinched victory at "Star Tanjo" in 1972 at 14. Subsequently, she signed with Sun Music agency and Victor Music, marking her official debut in February 1973 with the release of "Tenshi mo yumemiru" (Angels Also Have Dreams). Given their similar age, niche, and close debut dates, the industry and some fans pitted her against Momoe Yamaguchi despite their behind-the-scenes friendship. Both idols enjoyed substantial popularity, with Yamaguchi usually holding an edge in sales. The exception was in 1975 when Junpei, as fans affectionately knew her, dominated as the best-selling female idol in music and bromide sales.

In addition to her music career, Junko excelled as an actress. In 1983, she opted to conclude her singing career to dedicate herself solely to acting. A decade later, in 1993, the former idol shocked Japan by announcing her participation in a mass wedding ceremony organized by the controversial South Korean Unification Church at the Olympic Stadium in Seoul. Her husband had been chosen for her by the church.

Her association with the cult brought her career to an abrupt halt. With her image becoming closely linked to the church, TV networks and advertisers distanced themselves from her. Consequently, Junko relocated from Tokyo, devoting herself entirely to her faith and family. Since then, she has made a few comebacks. In 2006, she published a highly-publicized essay book, and in 2013, she celebrated the 40th anniversary of her debut with a special concert. In 2017 and 2018, she returned to the stage, coinciding with her musical comeback and the release of a new album, "My Ideology."

After this project, Junko has remained out of the spotlight, with an official return unlikely unless she completely renounces her ties with the United Church. The cult's controversial image became even more repellent following the murder of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in July, committed by a young man who attributed his family's financial and psychological turmoil to the church. Consequently, the cult's unethical financial practices and ties to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party have become widely discussed topics in the country. For Junko Sakurada, her affiliation with the cult has overshadowed her otherwise successful decades-long career.

Completing the trio alongside Junko and Masako was Momoe Yamaguchi. Although Yamaguchi's career has eclipsed that of almost every other idol of the 1970s, she initially experienced the least success among the three young girls. Unlike her peers, both of whom had claimed grand champion titles at "Star Tanjou!," Momoe secured second place at her final showcase. Moreover, her debut single was the poorest-selling among the trio. However, she would ultimately emerge as the definitive idol, and her retirement would serve as the perfect conclusion to an epoch-making career.

While Momoe, Junko, Masako, Mari, Agnes, Rumiko, and Saori, among others, collectively set an impressive precedent for future female idols, male idols also played a significant role in the era. In terms of profitability, male idols reigned supreme, thanks to the unwavering loyalty of their female fanbase. Johnny Kitagawa, the late founder of Johnny's Jimusho, would eventually become the most influential figure in the entertainment industry by monopolizing this niche for decades with his boybands.

However, during the 1970s, Kitagawa was just one among many. Although his agency achieved considerable success with the boyband Four Leaves, it was soloist Hiromi Go who briefly held the nation under his sway between 1973 and 1974. Unfortunately for Kitagawa, this period of dominance proved fleeting, as Go departed for another agency in 1976, signaling that Johnny Kitagawa still had much to accomplish to solidify his authority.

With Johnny's domination still on the horizon, Hideki Saijo emerged as the most influential male idol of the 1970s. Saijo enjoyed success with several hit singles, including the ballad "Chigireta Ai," released in 1973, and 1979's "Young Man," a cover of Village People's "Y.M.C.A." Demonstrating the power of devoted fangirls, Saijo became the first domestic solo artist to perform a concert at Nippon Budokan. His popularity quickly transcended the Budokan, propelling him to the status of a stadium headliner and solidifying his position as the decade's top concert ticket seller.

The loyalty of fangirls meant that male idols consistently outperformed any act in ticket sales. In the 1960s, The Tigers, considered one of the pioneers of the "group sound" movement and regarded by many as Japan's first idol group, became the first domestic act to hold a stadium concert. By the following decade, the "group sound" era had ended, but some former band members successfully transitioned into solo careers.

Kenji Sawada and Hideki Saijo, the two stadium-selling male idol superstars from the 80s.

Kenji Sawada, the former lead vocalist of The Tigers, remained a constant presence on the charts throughout the 1970s. Under the guidance of the influential Watanabe Pro agency, Sawada succeeded as a singer and actor. He brought a rockstar aura to his performances, incorporating impactful and extravagant visual elements and pioneering the use of makeup, drawing inspiration from David Bowie and glam rockers. In doing so, Sawada laid the groundwork for visual kei, a movement that would revolutionize Japanese rock in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Nicknamed "Julie" since his early days in the 1960s due to his admiration for Julie Andrews, Sawada continues to thrive as a prominent music figure in Japan, one of the few stars from that era still capable of selling out stadiums.

While girls' adoration often paves the way for male idols to enjoy lengthy careers, there are exceptions to this rule. In 1974, Finger 5 became one of the best-selling idol groups in the country. Comprising five young brothers from Okinawa, they were marketed as Japan's response to the Jackson 5 and consistently churned out hit singles. However, just two years later, their popularity took a nosedive. Several factors contributed to this decline, notably their heavy reliance on the two youngest members, aged only 10 and 12. These youngsters not only grappled with exhaustion from relentless work schedules but also faced the challenges of puberty, causing their voices to change and preventing them from hitting the right notes in their songs. Consequently, Finger 5 lost its appeal.

Finger 5's brief career underscores a crucial aspect of the idol industry: the importance of youthfulness. In Japan's gender-biased society, some male idols from the 1970s were granted the opportunity to age gracefully, evidenced by a few who maintained success well into their 60s and 70s. In contrast, female idols invariably confronted the pressures and inevitable decline associated with aging.

This brings us back to the quintessential idol of that era, Momoe Yamaguchi. By choosing to retire and steadfastly resisting any temptation to reenter the public eye, Yamaguchi effectively became frozen in time at 21 years old, her age at the moment she bid farewell to both showbiz and the public. This solidified her status as a legendary and unattainable icon—an idol who never aged.

70s Japan Trends Through the Music Charts (Part 3)

#enka#kayokyoku#momoe yamaguchi#70s japan#1970s#japanese music#jpop#discover japan#heibon punch#kenji sawada#hideki seiji#junko sakurada#70s idols#finger 5#mari tenchi#rumiko koyanagi#saori minami#four leaves#hiromi go

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#itsuroh shimoda#japanese 70s folk#itsuroh shimoda love songs and lamentations#70s music#70s japanese music#Youtube#70s japan

2 notes

·

View notes