#1933 - 1934 Century Of Progress Exposition In Chicago

Video

1933 - 1934 Century Of Progress, The Chicago World's Fair - Gigantic Fountain (No. 587), Published By Gerson Bros., Chicago, ILL. by Joe Haupt

#1933 - 1934 Century Of Progress Exposition In Chicago#1933 Chicago World's Fair#Vintage Century Of Progress Postcard Collection#World Fairs Memorabilia#World Fairs & Expositions#flickr

0 notes

Photo

A Native American demonstrates archery at the Century of Progress International Exposition, the world's fair held in Chicago during the summers of 1933 and 1934. © Century of Progress Records

#1933#1934#1930s#30s#A Century of Progress#Century of Progress#Chicago#Illinois#archery#World's Fair#~

123 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Century of Progress International Exposition--(1933-1934). Weimer Pursell. Neely Printing Co., [1933]

Some products that made their debut(not invention date) at the Chicago World's Fair included: CRACKER JACKS POPCORN, AUNT JEMIMA PANCAKE MIX, T H E Z I P P E R (like the zipper still used; other versions of the zipper never caught on), FERRIS WHEEL, WRIGLEY’S CHEWING GUM and SPRAY PAINTING.

#poster#posters#Illustration#graphic design#design gráfico#design graphique#Typography#vintage#history#histoire#historia

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

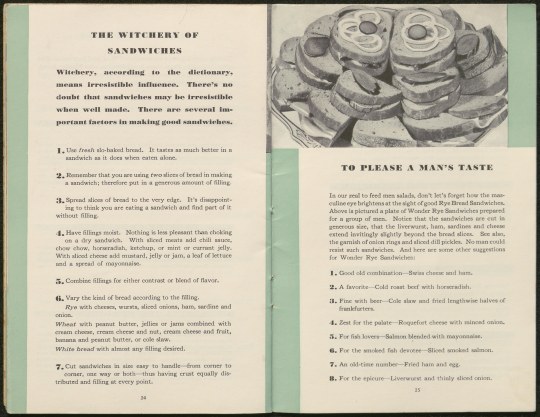

We’re saying goodbye to National Sandwich Month today. August was claimed for the sandwich as early as 1952, when the milling industry, commercial bakers, and other food industry interests joined forces with the National Restaurant Association, who spearheaded the campaign to announce to the country that “August is Sandwich Time”.

The pages seen here are from the World’s Fair edition of The Wonder Book of Good Meals, a circa 1932 pamphlet of Wonder Bread based recipes released by the Continental Baking Corporation as a tie in to its presence at the 1933-1934 Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.

In addition to teaching readers about the “Witchery of Sandwiches” and providing some guidance for those looking to feed sandwiches to men, its pages offered irresistible recipes for Cheese Dreams, Pilgrim Pies, De Luxe Bridge Loaf, and Hot Bread (which is exactly what it sounds like).

The Wonder Book of Good Meals is Pam 2010.258 in Hagley Library’s Published Collections. To view the pamphlet in its entirety online, click here to visit its page in our Digital Archive.

#National Sandwich Month#NationalSandwichMonth#Sandwich Month#August#1950s#National Restaurant Association#August is Sandwich Time#Wonder Bread#WonderBread#1930s#Continental Baking Corporation#Century of Progress#Century of Progress International Exposition#hot bread#it's called toast#sandwiches#bread#bread industry#food industry#food culture#American food#witchery#witchery of sandwiches

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

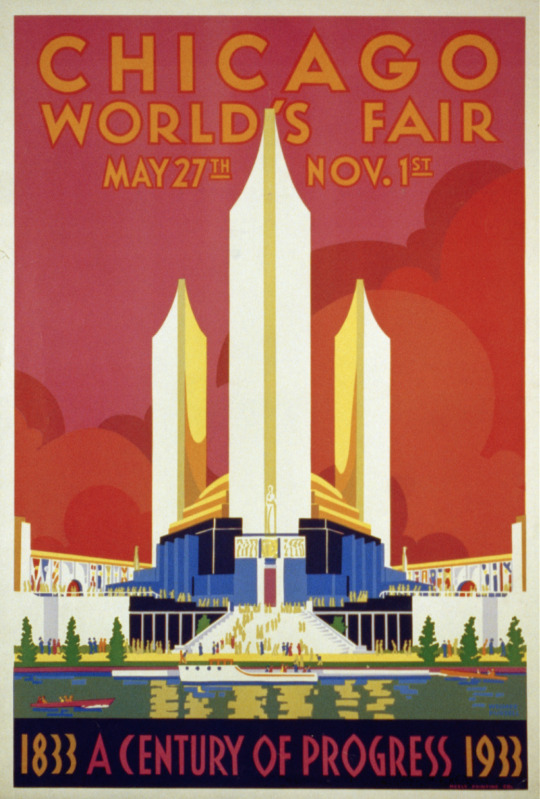

Chicago World’s Fair: A Century of Progress

Official Poster by Weimer Pursell, 1932

Source: Library of Congress / Wikipedia

One of many iconic posters whose images you’ll still find reproduced as prints, on T-shirts, etc. It’s so great! And not inspired out of fantasy, but reality, as you’ll see when the actual pictures start coming up on this blog :)

Intro to the fair from the Chicago Architecture Center:

Rather than turn longingly to the past, the 1933-1934 Century of Progress Exposition looked to the future. It was the second world’s fair hosted by Chicago. The site of the fair was Northerly Island, an artificial stretch of land that is actually a peninsula, not an island.

Despite its name, the fair was less a retelling of Chicago’s first 100 years and more a showcase for modern living, consumerism and entertainment. All of this was driven by the need to stimulate spending during the Great Depression. There were nearly two dozen corporate pavilions at the exposition pushing the latest gizmos and gadgets for home and car—a big increase from the nine corporate pavilions at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

The exposition’s architectural team included Daniel Burnham’s sons, Hubert and Daniel Jr., who took the reins of their father’s practice following his death. Unlike the elder Burnham—who 40 years earlier emphasized the Beaux-Arts style in the “White City”—the 1933-1934 fair planners embraced a vibrant modern aesthetic. These styles would later come to be known as Art Deco and Art Moderne. They feature clean lines, synthetic materials and bright splashes of color. Leading the charge among a who’s who of designers assigned to construct areas of the fair were young architects Louis Skidmore and Nathaniel Owings, who would later found Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. They designed exhibitions throughout the grounds, ensuring a consistent aesthetic—one that Frank Lloyd Wright, left out of the planning, derided as a “sham,” but that others saw as progressive.

George Keck's famed House of Tomorrow also debuted at the exposition. It was later transplanted to the Indiana dunes alongside other futuristic homes. This steel-framed model home deployed a radical use of glass and a curtain wall system. It included not only a garage, but an airplane hangar for the day when we’d all need a space to park our private planes. The interior of the house was more down to earth, with features like dishwashers and air conditioning that would indeed become commonplace household items.

The Century of Progress Exposition had many lasting architectural impacts on Chicago. It introduced millions of people to newly created lakefront land near the Museum Campus and put them in contact with new inventions. It also foretold the rising influence that the automobile would have on city planning. The fair hinted at a future change in city design—particularly how buildings would relate to one another and how houses would address the street.

Perhaps most importantly, the 1933-1934 World’s Fair gave people hope for the future during the Great Depression. Now, more than 80 years later, the site of the fair is a beautiful lakefront park and Art Deco is a celebrated architectural style.

#chicago world's fair#world's fair#century of progress#century of progress exhibition#chicago#chicago history#art deco#art deco architecture#1930s history

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The General Motors Building, Chicago. Century of Progress International Exposition, 1933-1934

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help This Scholar Reverse the Erasure of Native Contributions in the Creation of These 20th-Century Murals

https://sciencespies.com/history/help-this-scholar-reverse-the-erasure-of-native-contributions-in-the-creation-of-these-20th-century-murals/

Help This Scholar Reverse the Erasure of Native Contributions in the Creation of These 20th-Century Murals

Smithsonian Voices Smithsonian Institution Office of Fellowships and Internships

Reversing the Erasure of Native Contributions to Muralism

October 9th, 2020, 9:00AM

/ BY

Davida Fernandez-Barkan

Eduard Buk Ulreich, Advance Guard of the West (mural study, New Rockford, North Dakota Post Office), ca. 1939-1940, tempera on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1965.18.33

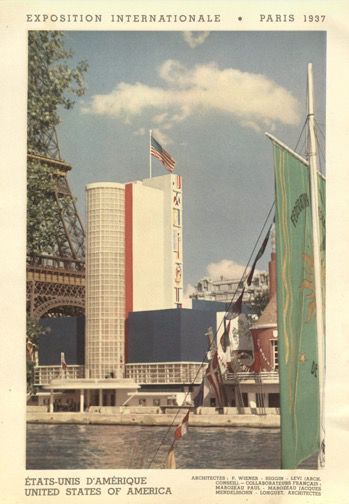

Being an art historian is a little like being a detective. It sometimes takes me to unlikely places—including, recently, a basement outside St. Louis, where the relatives of an artist I was researching for my dissertation generously allowed me to review documents from his life. The artist, Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, had designed a number of publicly funded murals throughout his career; studies for many of them can be found in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Renwick Gallery (SAAM). My interest in Ulreich was related to two 88-foot wooden panels inspired by Native American symbols that he conceived for the United States Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.[1] One document in particular has occupied my thoughts in the months since my visit: a newspaper clipping showing two men shaking hands. The men stand in front of what appears to be Ulreich’s mural Indians Watching Stagecoach in the Distance (1937), which he painted for the post office in Columbia, MO. The man on the left is named in the caption as the 1937 U.S. pavilion’s “chief designer,” Paul Lester Wiener, while the one on the right, appearing in a feathered headdress, is identified simply as, “a Navajo Indian who gave his advice on the vast murals depicting Indian life and thought which are being painted by Buck [sic.] Ulreich for the outside of the skyscraper tower.”[2] My goal, ultimately, is to identify this man. Yet even without declaring this man’s identity, the photograph highlights an oft-overlooked aspect of twentieth-century American art: the essential contributions of Native Americans to the mural movement that overtook the United States in the years between World War I and World War II.

Paul Lester Wiener and an unidentified advisor for the U.S. Pavilion murals, Private archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO. (Hans Knopf, Pix, Inc.)

Ulreich was one of the many U.S. artists who received funds to install murals in public buildings in the United States during the 1930s and early 1940s through programs such as the Public Works of Art Project, the Treasury Section of Fine Arts, and the Works Progress Administration. He styled himself as a “Cowboy-Painter,” a claim that lay in part in his avowed knowledge of Native American cultures.[3] The artist was vocal about time he had spent around Native Americans, including as an actual cowboy on a ranch on an Apache reservation in Arizona. He posited that it was this type of exposure that resulted in his selection to paint the exposition murals.[4] Yet as the newspaper clipping indicates, Ulreich required the input of at least one Native advisor to accurately convey the mural’s symbols. A different clipping in Ulreich’s family’s archive identifies a number of the symbols that appear, stacked on top of one another, in the pavilion’s murals. These include a “Kachina”[5] figure popular in Pueblo cultures, a Crow thunderbird, and an adaptation of a deity used in Navajo[6] sand painting.[7] This same clipping indicates that, although Ulreich designed the murals, a “member of the Navajo tribe” actually painted them. This individual, like the man in the photograph, is unnamed in the clippings. Neither appears to be mentioned at all in fair-sponsored publications and they are absent altogether from what limited secondary literature exists about the U.S. pavilion at the 1937 exposition.

The U.S. Pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, pylon murals designed by Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, from Photographies en couleurs: exposition internationale des arts et des techniques appliqués à la vie moderne: album official (Paris: Photolith, 1937)

The 1937 fair was not the first world’s fair to feature murals indebted to Native American labor and knowledge. The 1933 Century of Progress exposition in Chicago had included a series of murals executed by a group of artists associated with the Santa Fe Indian School. Changing perceptions of Native culture, reflected in the work of both Native and non-Native artists alike, were in fact a hallmark of the mural movement in the United States. In addition, one of the movement’s most revolutionary aspects was an increased access to the role of “artist.” Not only men of European descent, but also many women, Native Americans, and other people of color became muralists. Still, artists from these marginalized groups did not receive the same treatment as their white male counterparts. Like the Native participants in the 1937 exposition, the artists who developed the Century of Progress murals are anonymous in fair literature. One administrative document refers to them simply as the “Santa Fe Indians,” while it refers to white artists such as George Biddle and John Norton by name.[8] Thanks to the work of art historians such as Jennifer McLerran, we know the identities of many of the mural artists involved with the Santa Fe Indian School. Several of these are represented in SAAM’s collection, including Julian “Pocano” Martinez, Tse Ye Mu (known alternately as Romando Vigil), Awa Tsireh (known alternately as Alfonso Roybal), Oqwa Pi (known alternately as Abel Sanchez), and Ma Pe Wi (known alternately as Velino Shije Herrera), whose murals can also be found in the Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C.[9]

To identify the Native individuals who helped create the panels at the 1937 fair would ensure that they are given credit, if belated, for their work. Beyond this, it would be a means of celebrating Native contributions to the mural movement. Native participation in the painting of such monumental, public works of art during this period is little known and seldom discussed, a problem that is compounded when we do not know the names of the individuals who took part. The erasure of nonwhite groups from public life is particularly dangerous, as it has a pernicious history in this country. From attacks on Black communities to anti-immigrant rhetoric, the claim that only white Americans “create,” while others sponge off their productivity, has been one of the most insidious myths shoring up the ideology of white supremacy over the last several centuries.[10]

Searching for the identity of the man in the 1937 photograph is a small way of combatting this myth. It is a way of ensuring that white artists do not receive the only credit for their collaborations with communities of color. I am therefore hoping that anyone who might have information about the man in the photograph or other Native participants in the 1937 exposition will get in touch! With such interventions, perhaps art history can help to make the inclusiveness promised by muralism a reality.

[1] Carlyle Burrows, “A New Project in Modern Decoration: The Stage Coach and the Pony Express,” New York Herald Tribune, August 1, 1937, F6.

[2] Art historian Emily Burns notes that the man’s dress appears to be a composite of clothing from a number of different Native nations. The headdress, for example, is typical of Plains rather than southwestern cultures. It thus constitutes a kind of Native American “intern-nationalism” against the backdrop of the International Exposition. Emily Burns, email message to the author, September 30, 2020.

[3] “With Latin Quarter Folk,” Folder “1926,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[4] Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, “Eduard Buk Ulreich: A Brief History,” n.d., Folder “Buk Autobiography,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO; “Story of the Indian Ornament for the American Exposition Building at Paris, France,” n.d., Folder “1937,” Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[5] The term “katsina” (plural “katsinam”) is preferred.

[6] Members often prefer the name “Diné” to Navajo.

[7] Francis Smith, “Brilliant Murals Portray Lore of U.S. Indains at Exposition,” Paris Herald, July 27, 1937, Private Archive of Eduard “Buk” Ulreich, St. Louis, MO.

[8] “Interior Painting & Murals,” n.d., Series 15, Box 7, Folder 15-74, Century of Progress World’s Fair, 1933-1934 (University of Illinois at Chicago).

[9] See Jennifer McLerran, A New Deal for Native Art: Indian Arts and Federal Policy, 1933-1943 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012), 164.

Davida Fernandez-Barkan is a Ph.D. candidate in History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University and was a Smithsonian Institution Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum during the 2019–20 academic year. She holds an A.B. and M.A. in History of Art and Architecture from Harvard and an M.A. in Curating the Art Museum from The Courtauld Institute of Art. She has worked or interned in curatorial departments at the Harvard Art Museums, the Centre Georges Pompidou, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, the National Gallery of Art, Tate Britain, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Her work appeared in the most recent issue of the journal Public Art Dialogue. Her dissertation is titled, “Mural Diplomacy: Mexico, the United States, and France at the 1937 International Exposition in Paris.” She is currently a Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (CASVA) David E. Finley Fellow (2020–23).

More From This Author »

#History

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Century Of Progress!

A Century Of Progress!

When the World’s Fair came to Chicago, it was called “A Century Of Progress International Exposition”. It was originally to run from May 27th 1933 until November 12th 1933, but it was such a success that the Fair was opened again on May 26th the following year and ran until October 31st, 1934.

There were many exhibitors at the Chicago World’s Fair—some of the exhibitors were automobile…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

World's Fair 1933 a.k.a. A Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago (May 27, 1933 – Oct 31, 1934) [1544x2000] Check this blog!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#World’s Fair Wednesday

Helena Rubenstein, international beauty authority, gets a glimpse of the beauty that is A Century of Progress through a window in the ultra-modernistic Trustees' room of the Administration building. Her guide, who is pointing out the sights, is Lucia Lewis.

To find out more about the Century of Progress World’s Fair that took place in Chicago in 1933-34, visit the Century of Progress collection finding aids or check out other photos in this digital collection: Images of Progress: Views from A Century of Progress International Exposition, 1933-1934.

[COP_17_0006_00249_015], Century of Progress Records, 1927-1952, University of Illinois at Chicago Library.

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

HIAWATHA #2 The Milwaukee Road (CMStP&P) Early 1930s

Caption: “On her initial run from Chicago to Minneapolis she clocked a stretch north of Tomah, Wisconsin at slightly over 126 mph. Not bad for an old steamer (not bad for a modern Diesel). The driving wheels were 84 inches in diameter. The picture is a postcard from the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition, 1933/1934.”

(via HIAWATHA #2 The Milwaukee Road (CMStP&P) | Early 1930s On he… | Flickr)

#milwaukee road#hiawatha#MILW hiawatha#MILW#steam#steam train#steam engine#steam locomotive#locomotive#passenger train#train#trains#trainspotting#track#tracks#steampunk#design#streamliner#1930s#chicago#chicago century of progress#postcard#old postcard#vintage#vintage postcard#retrowave#art deco#retro#retrostyle#RR

60 notes

·

View notes

Video

1933 - 1934 Century Of Progress, The Chicago World's Fair - General View By Illumination (No. 578), Published By Gerson Bros., Chicago, ILL. by Joe Haupt

#1933 - 1934 Century Of Progress Exposition In Chicago#1933 Chicago World's Fair#Vintage Century Of Progress Postcard Collection#World Fairs Memorabilia#World Fairs & Expositions#flickr

0 notes

Photo

World's Fair 1933 a.k.a. A Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago (May 27, 1933 – Oct 31, 1934) [1544x2000] via /r/HistoryPorn http://bit.ly/2WT6ZjX

0 notes

Photo

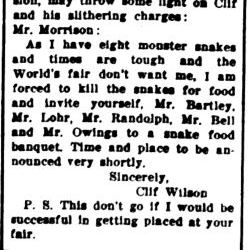

August 2, 1934; St. Charles Chronicle Vol LIII, No. 15, p. 5

[image caption: Will Eat Snakes if Fair Doesn’t Want ‘Em

Chicago. - Last year one Clif Wilson ran a snake show on the Midway, at A Century of Progress, where the Street of Villages is now located. Little has been heard about Clif since the 1933 World’s fair closed, but the following telegram addressed to Jack Morrison, of the exposition’s publicity division, may throw some light on Clif and his slithering charges:

Mr. Morrison:

As I have eight monster snakes and times are tough and the World’s fair don’t want me, I am forced to kill the snakes for food and invite yourself, Mr. Bartley, Mr. Lohr, Mr. Randolph, Mr. Bell and Mr. Owings to a snake food banquet. Time and place to be announced very shortly.

Sincerely, Clif Wilson

P.S. This don’t go if I would be successful in getting placed at your fair.]

#history#Chicago World's Fair#old news articles#snakes#people being Extra#the things you find when you're searching thru microfilm for someone's obituary...#St. Charles Chronicle#cw: snakes#cw: implied animal death#(I guess?)#tbh one of the best things about being a reference librarian is finding weird stuff like this

1 note

·

View note

Photo

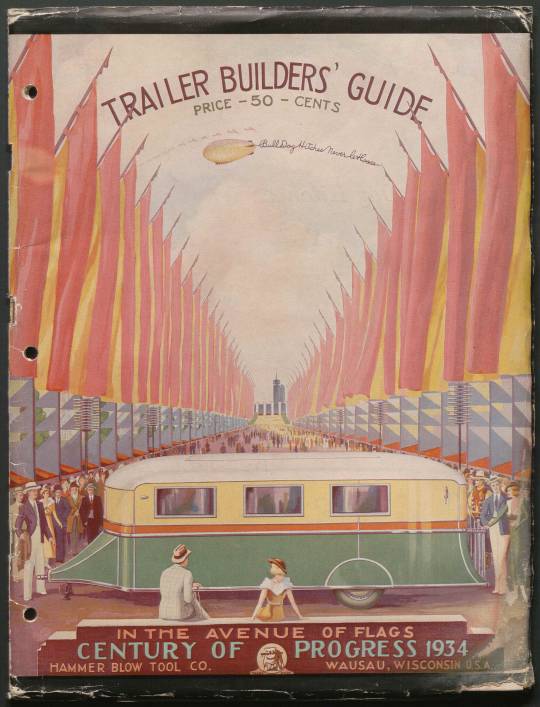

This catalog of trailers and guide to trailer building from Wausau, Wisconsin’s Hammer Blow Tool Company has us feeling mighty tempted to hit the open road this #TravelTuesday.

The catalog was designed to market the Company’s lines of trailers, trailer blueprints, and trailer accessories being featured at the Century of Progress International Exposition at the Chicago World's Fair, held in Chicago, Illinois from 1933 to 1934.

This item is call number Trade Cat .H2245 1933 in the Hagley Library’s collection of trade catalogs and pamphlets. You can view it online now in our Digital Archive by clicking here.

#Travel Tuesday#TravelTuesday#trailers#trailer homes#travel trailers#trailer#travel#hammer blow tool company#1930s#1930s aesthetic#1930s illustration#mobile home#mobile homes#mobile living#century of progress international exposition#chicago world's fair

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

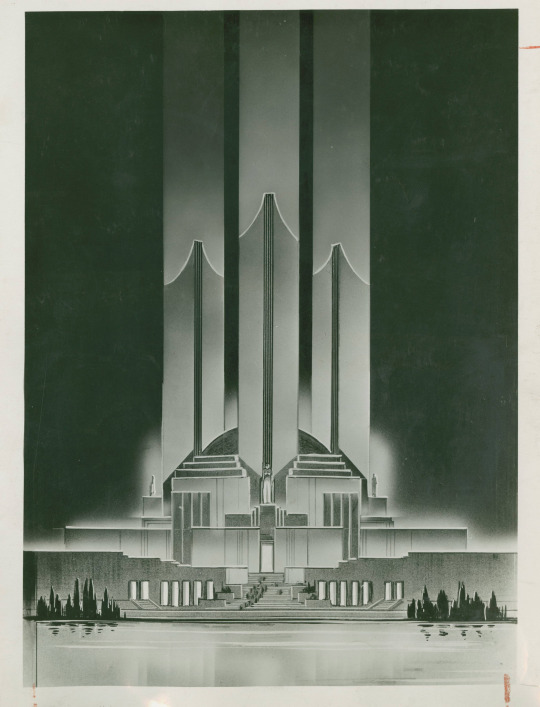

Century of Progress International Exhibition - Chicago

Poster Source: Newberry Library (Chicago)

My love for pre-WWII world’s fair and expo architecture is boundless. I have a particular affinity for the 1939/1949 NY World’s Fair, but Chicago’s in 1933 and the Pan-Pacific Exposition and others were awesome as well.

For now, I’m going the present the architecture of the Century of Progress, along with some of the history.

Aerial from Newberry Library, the origin of many of the photos I’ll be sharing.

From a great CoP online reference by Chicaology:

A Century of Progress was organized as an Illinois nonprofit corporation in January 1928 for the purpose of planning and hosting a World’s Fair in Chicago in 1933. City officials designated three and a half miles of newly reclaimed land along the shore of Lake Michigan between 12th and 39th streets on the Near South Side for the fairgrounds. Held on a 427 acres portion of Burnham Park A Century of Progress opened on May 27, 1933. The fair’s opening night began with a nod to the heavens. Lights were automatically activated when the rays of the star Arcturus were detected. The star was chosen as its light had started its journey at about the time of the previous Chicago world’s fair—the World’s Columbian Exposition—in 1893. The rays were focused on photoelectric cells in a series of astronomical observatories and then transformed into electrical energy which was transmitted to Chicago.

By opening day, thirty-two major buildings had been constructed, everything from the “breathing” Travel and Transport Building—with a suspended roof that expanded and contracted as much as six feet as the temperature varied—to the 227-foot tall Great Havoline Thermometer, hailed as a “monument to Chicago’s climate.”

“The morning of the fair,” Martha McGrew, the General Manager’s assistant recalled, “we went up to the roof and looked over at the 12th Street bridge. It looked like the lines were all the way over to the Art Institute. It was the biggest thrill of all. People were coming to the fair! We had been worried about that, but ten thousand people came that first day.” It was a bright spot in a world of gloom.

Originally, the fair was scheduled only to run until November 12, 1933, but it was so successful that it was opened again to run from May 26 to October 31, 1934. The fair was financed through the sale of memberships, which allowed purchases of a certain number of admissions once the park was open. More than $800,000 was raised in this manner as the country came out of the Great Depression. A $10 million bond was issued on October 28, 1929, the day before the stock market crashed. By the time the fair closed in 1933, half of these notes had been retired, with the entire debt paid by the time the fair closed in 1934. For the first time in American history, an international fair had paid for itself. In its two years, it had attracted 48,769,227 visitors. On the last day of the fair, a record 374,127 people attended.

According to James Truslow Adams’s Dictionary of American History, during the 170 days beginning May 27, 1933, there were 22,565,859 paid admissions; during the 163 days beginning May 26, 1934, there were 16,486,377; a total of 39,052,236.

A Century of Progress management, which posted a $1,000,000 bond to insure that Burnham Park would be left in its nearly original condition, hired a Springfield firm to tear down the Century of Progress. The demolition began in February 1935, and ended almost a year later, about half the time it took to build the fair.

Most of the exposition’s artifacts have vanished. Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry received many exhibits, but all have been destroyed or given away because they became technically obsolete, according to the museum’s registrar.

The pumping equipment in the grand fountain—enough to supply the water needs of one million people—was dismantled and sold, along with twelve million feet of lumber, twenty thousand tons of steel, eight million feet of wallboard, fifty miles of pipe, three thousand flood lights, and three thousand doorstops. A Century of Progress General Manager, Lenox R. Lohr bought, among other things, an eighteen-foot fishing boat for $26.

Much more coming.....

Wendy

#century of progress#century of progress exhibition#chicago#chicago history#1930s history#world's fair#art deco#art deco architecture#great depression#illinois history

54 notes

·

View notes