#日本フクラ

Text

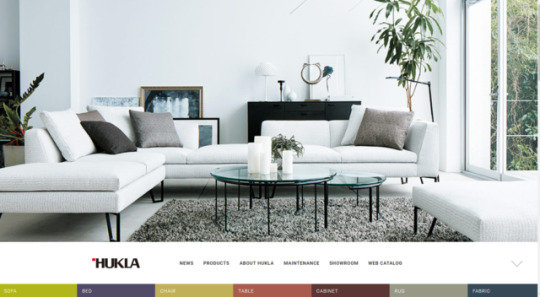

いい家具と、いいカーテンと。【⑨HUKLA 日本フクラ】

糸の素材、撚り方、織り方、編み方、染め方、加工の仕方など。

カーテンをかたちづくる、すべての要素にこだわったのがアスワンの『AUTHENSE(オーセンス)』です。

その見本帳に掲載している、家具メーカー様にご協力いただいた、家具・椅子張り生地・カーテンのコーディネートをご紹介。

家具メーカー:日本フクラ @hukla_official

商品名/品番:カストール カウチ/N528-49(張地:18-3929、ベース:ダークブラウン(DB))、背クッション/N528-37(張地:18-3929)

カタログ:AUTHENSE edit10

カテゴリ:Function/抗菌・防臭

名前:シェーン

品番:C1147

機能:防炎、抗菌防臭、ウォッシャブル

くわしくはお近くの #インテリア専門店 またはプロフィール @aswan_jp のリンクから『AUTHENSE』をご覧ください

instagram

#インテリア#インテリアコーディネート#インテリアコーデ#コーディネート#カーテン#オーダーカーテン#オーセンス#authense#curtains#カーテンレール#装飾カーテンレール#リフォーム#リノベーション#家具#ソファ#照明#フクラ#hukla#日本フクラ#カストール#インテリア好き#インテリア選び#アスワンのカーテン#インテリアショップ#インテリア専門店を元気にする#アスワン#aswan#アスワンのある暮らし#アスワンと家具#インテリア専門店

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (48): (1587) Eighth Month, Twenty-fifth Day, Midday.

48) Eighth Month, Twenty-fifth Day; Midday¹.

It had been promised that [Imai] Sōkyu --

﹆ [would] bring the tea².

◦ 4.5-mat [room]³.

◦ [Guests:] Sōkyū [宗久]⁴, Yakushi-in [藥師院]⁵, Fujishige [藤重]⁶, Rōju [良壽]⁷, Sōmoto [宗本]⁸.

Sho [初]⁹.

﹆ Engo [圓悟]¹⁰: in accordance with [the guests’] request to bring [this kakemono] out [for their appreciation]¹¹.

The gedai [外題] was displayed in the toko¹².

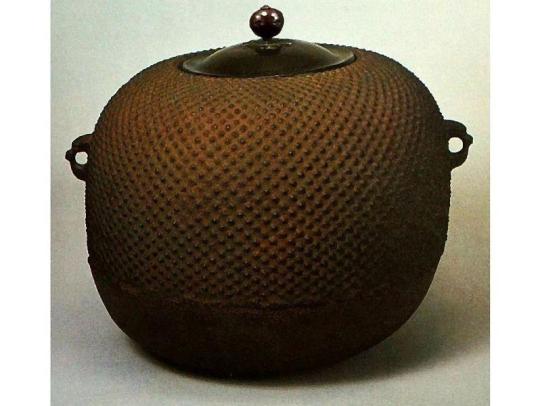

◦ On a ko-ita [小板], the furo ・ unryū-gama [風爐 ・ 雲龍釜]¹³.

▵ Shiru saku-saku [汁 サク〰]¹⁴.

▵ Roast shigi [鴫] ・ kamaboko [カマホコ]¹⁵.

▵ Asa-zuke [アサツケ]¹⁶.

▵ Senbei ・ yaki-guri [センヘイ ・ ヤキクリ]¹⁷.

Go [後]¹⁸.

◦ The toko remained as it was¹⁹.

◦ Mizusashi Shigaraki [水指 シカラキ], on top of which was placed the hishaku [ヒシヤク]²⁰.

﹆ Sa-tsū-bako [茶通箱]²¹.

However, inside [the sa-tsū-bako] were the Shiri-bukura [尻フクラ] ・ ko-natsume [小ナツメ]²².

◦ Habōki [羽帚]²³.

Su [ス]²⁴.

◦ Chawan kuro [茶碗 黒], ori-tame [折撓]²⁵.

_________________________

¹Hachi-gatsu nijū-go-nichi, hiru [八月廿五日、晝].

The Gregorian date was September 27, 1587, since the Eighth Month of Tenshō 15 had only 29 days.

This seems to have been another chakai given for influential machi-shū tea practitioners, probably intended to promote interest in Hideyoshi’s upcoming Kitano ō-cha-no-e [北野大茶の會]. It appears that the guests asked to inspect the Engo bokuseki -- perhaps as a sort of compensation for their taking part in the gathering.

There are several issues with the Enkaku-ji version of this entry that are contradicted by (all of) the other manuscripts (including Jitsuzan’s original copy, which was made with the Shū-un-an document in front of him), suggesting that Jitsuzan either mistook his earlier notes, or deliberately decided to change things for reasons of his own; and (in contradiction to Rikyū’s own writings on the subject) the premise on which the use of the sa-tsū-bako is based clearly derives from machi-shū practices that became mainstream, as a result of Sōtan’s influence*, during the Edo period -- rather than the way that Rikyū appears to have handled this kind of temae. These problems might be considered so significant that it is possible to doubt whether this was an actual chakai hosted by Rikyū -- or whether the entry is completely (or at least partially) spurious.

___________

*Ultimately, these were machi-shū practices that appear to trace their origins back to Jōō’s middle period (when the form of the cha-kai [茶會] was being codified -- based on, though increasingly distinct from, the Shino family’s kō-kai [香會]). Though later superceded by subsequent developments -- which were largely associated with Rikyū (and his influence on Jōō during the last year of the latter’s life) and his circle. A movement to return to the earlier forms appeared shortly after Rikyū’s seppuku, as part of a semi-official effort to repudiate Rikyū’s influence on chanoyu -- championed (with encouragement from at least some of the important daimyō surrounding Hideyoshi such as Date Masamune) by the group of machi-shū practitioners associated with Imai Sōkyū: It was under the influence of this group that Sōtan trained (he was some 14 years of age when Rikyū died); and it was their teachings that he disseminated when he ultimately rose to his position of influence on account of his fictive relationship to Rikyū -- a relationship that was especially important to the Tokugawa bakufu (since it furthered their efforts to turn Hideyoshi’s collection of famous tea utensils into cash).

²Yaku-soku ni te Sōkyū [h]e ﹆cha jisan [約束ニて宗久ヘ ﹆茶持參].

This words cha jisan [茶持參] are marked with a red spot in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, indicating the importance of Sōkyū’s agreeing to provide the tea. However, none of the other versions of this kaiki* are formatted in this way (suggesting that the emphasis -- provided by the red spot -- was added by Jitsuzan, rather than Rikyū).

In all of the other versions of this kaiki, this line reads yakusoku ni te Sōkyū cha jisan [約束ニて宗久茶持參] -- without the particle [h]e [ヘ]†, or the emphasis on the words cha jisan [茶持參].

__________

*Including Jitsuzan's original copy, which he made with the Shū-un-an documents in front of him.

†The particle [h]e [へ] confuses the sense of the statement -- making possible the interpretation that Rikyū was taking the gift tea to Sōkyū.

³Yojō-han [四疊半].

The 4.5-mat room in Rikyū's residence.

⁴Sōkyū [宗久].

This was Imai Sōkyū [今井宗久; 1520 ~ 1593], who was said to be “the other one” of Jōō’s two greatest disciples*.

Sōkyū was married to Jōō’s daughter, and assumed the guardianship of Jōō’s son Sōga [宗瓦; 1550-1614] (who was just six years of age at the time of his father’s death).

At the time of this chakai, the relations between Sōkyū and Rikyū were still more or less cordial, with their main source of contention restricted to their rivalry for Hideyoshi's favor†.

___________

*The other was, or course, Rikyū.

†The primary cause of the bad blood between Rikyū and Sōkyū seems to have arisen because Rikyū disagreed with Sōkyū over how he was managing Sōga’s (Jōō’s son) affairs.

Sōkyū seems to have taken charge of Jōō’s extensive collection of meibutsu utensils shortly after Jōō’s death, which he said was intended both to safeguard them (as Sōga’s inheritance), as well as (in certain cases) reimburse himself for the added expenses placed on his household by the boy’s upbringing. Rikyū, meanwhile, believed (and made it publicly known) that, in his opinion, Sōkyū was simply enriching himself -- both monetarily and with respect to his reputation as a tea master -- at the boy’s expense. (It must be remembered, with respect to meibutsu utensils, that ownership implied that the owner also had been initiated into the secrets of their use -- and, indeed, it was just this fact on which not only Jōō’s own reputation, but eventually that of Sōkyū as well, had been based.)

Rikyū’s own densho addressed to Sōga, meanwhile, suggests that, in his opinion at least, Sōkyū was not doing a very good job at educating the young man in the details of chanoyu that had been finalized by Jōō at the end of his life: rather, it seems that he was schooling him in Sōkyū’s own version of these teachings (which seems to have remained faithful to the style of chanoyu popularized by Jōō during his middle period -- before Rikyū returned from his sojourn in Korea) . Sōkyū’s way of practicing chanoyu (as the leader of the machi-shū faction that was increasingly opposed to Rikyū’s simplifications) can be identified with what is now called the machi-shū style of tea -- which passed into the modern world through Sōtan and his descendants. The difference between Sōkyū’s “machi-shū style” and Rikyū’s chanoyu can be seen clearly by comparing Rikyū’s densho with the practices advocated by the modern Senke schools.

After Rikyū’s death, Sōkyū was one of the leaders of the group that sought to eradicate all traces of Rikyū’s teachings from the practice of chanoyu -- and, given the subsequent and lingering animosity between the Sen families and Rikyū’s own writings, it might be said that Sōkyū was more successful in leaving his imprint on chanoyu than Rikyū, or than he (Sōkyū) could ever have dreamed possible.

⁵Yakushi-in [藥師院].

This was Rikyū's nickname for the man more usually known as Yakuin Zen-sō [施藥院全宗; 1525 ~ 1599]*. Formerly a monk from Ei-san [叡山]†, he was also a respected medical doctor of the period, and a close personal attendant of Hideyoshi's‡.

__________

*He was also a chajin and had been a disciple of Jōō.

†This mountain is now usually called Hiei-san [比叡山]. It is one of the peaks in the mountain range between Kyōto and Ōtsu (to the east).

‡Perhaps occupying a position similar to a personal physician.

Hideyoshi was suffering from tertiary syphilis (which evolved into neurosyphilis in the second half of the 1580s) during the last years of his life (which accounts for his increasingly erratic behavior during this final decade), and so the near-constant attendance of a physician (who could at least offer a degree of palliative care) would have been important to him and those around him.

It is inferred that his increasing susceptibility to his delusions of grandeur – specifically that he could succeed in conquering China and having himself installed as Emperor (as suggested by the Korean expatriates in Hakata – whose actual goal seems to have been causing political instability on the Korean peninsula, thus potentially could have allowed for a restoration of the Han [韓] republic that was overthrown by the Ming military incursions aimed at reinstating the feudal system on the Korean peninsula, under the Lee family (as a Chinese puppet-regime), in the middle of the previous century) – increased in step with his developing neurosyphilis.

⁶Fujishige [藤重].

This was Fujishige Tōgen [藤重藤元; his dates of birth and death are not known], a famous lacquer artist from Nara. He was considered the greatest master of that period, and his list of patrons is said to have included both Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

⁷Rōju [良壽].

This seems to refer to the machi-shū of Sakai known as Akane-ya Rōju [茜屋良壽; his dates are unknown]. His name is also given as Akane-ya Dōju [茜屋道壽] (which would make him a fellow disciple of Araki Dōchin, together with the young Rikyū; perhaps these two were of a similar age).

His name appears as a guest several times in Rikyū's kaiki, but the details of his practice are not known.

⁸Sōmoto [宗本]⁸.

This was the man known as Noto-ya Sōmoto [能登屋宗本; his dates are not known], another machi-shū of Sakai, and apparently a chajin as well.

No further details have been discovered relating to his life and career.

⁹Sho [初].

The shoza.

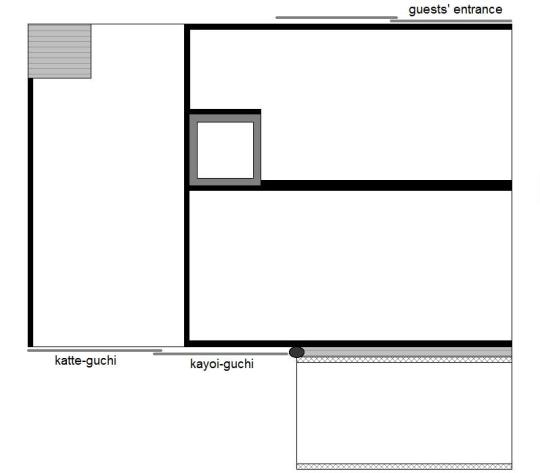

With respect to the kane-wari:

- the tokonoma contained the kakemono, displayed rolled up on the floor of the toko, so that the guests could inspect the gedai [外題]*, and so was han [半]†;

- the room, meanwhile, contained the ko-ita furo, and so was han [半] as well;

- there was no tana.

Han + han is chō, which is proper for the shoza of a gathering held during the daytime.

__________

*The gedai [外題] is a sort of title (actually, it generally contains the name of the artist responsible for the composition that is featured on the scroll), written on a small piece of paper that is glued to the back of the scroll near the upper roller. Thus, it was originally intended to allow someone to know what the scroll contained without going to the trouble of opening it up. Some of the earliest gedai were written by several of the great Higashiyama dōbō [東山同朋]; and, since they are verified by the writer’s seal, the gedai became an object of appreciation in its own right (this was especially important when many of the old paintings, which were often fragments of larger works salvaged from deteriorating specimens, lack their artist’s signature -- hence the gedai alone provides the viewer with the ascription, which was based on the dōbō’s expertise).

†Tanaka Senshō, unfortunately, confuses things by suggesting that perhaps the toko was empty when the guests entered the room, with Rikyū only bringing the scroll out from the katte after the guests had entered (they would therefore have had to all move to the tokonoma to view the gedai once the scroll was placed there). This, however, would confound the kane-wari -- as well as contradict Rikyū's own words (gedai wo kazaru [外題ヲカサル] -- that “the gedai was displayed [in the toko]”).

¹⁰Engo [圓悟].

This is the bokuseki now usually known as the Nagare Engo [流れ圜悟], formerly owned by Shukō (this, it is said, is the scroll that tradition holds was given to him by Ikkyū Sōjun, and before which he was encouraged to perform chanoyu), which he hung in his room when serving tea. Furthermore, this is said to have been the first bokuseki ever used for chanoyu*.

The scroll was written by the Chinese Chán monk Yuán-wù Kèqín [圜悟克勤; 1063 ~ 1135], the editor of the Bìyán Lù [碧 巖 錄] (Heki-gan Roku; the Blue-cliff Records).

This document was not intended (by Yuán-wù Kèqín) to be used as something like a scroll. It is actually a fragmentary part of Yuán-wù’s notes from one of his lectures (he traveled around China presenting lectures on the cases in the Bìyán Lù at various temples, and this is a fragment of the text of one of these lectures -- probably preserved originally by one of the auditors, as a sort of souvenir of the experience).

Precisely how this document made its way to Japan is unclear, though it seems most likely that Ikkyū Sōjun brought it with him when he immigrated from Korea at the beginning of the persecution of Buddhism (as both a monk, and the posthumous son of the last king of Koryeo, Ikkyū had double reason to fear for his life during this time of great trouble for the faith) on the Korean peninsula.

___________

*Before this, only paintings (almost always imported from the continent) were displayed in the tokonoma. The original intention was to recreate a scene of Amida’s Western Paradise.

¹¹Shomō-yue jisan [所望故持參].

This means that the reason (yue [故]) the scroll was brought out (jisan [持參]) on this occasion was because of a request (shomō [所望]) made by the guests. The request likely was tendered before, or at, the time when the guests accepted the invitation.

¹²Gedai wo kazaru [外題ヲカサル].

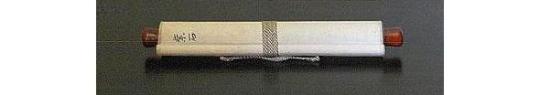

The gedai [外題], which is usually translated to mean “title,” refers to something written on the back side of the scroll, near the upper roller, that identifies the scroll’s contents. While the gedai is sometimes written directly on the mounting itself (as in the example shown below), since the Higashiyama period it has also been the custom to write this information on a small slip of paper*, which is then glued onto the back of the scroll.

Now, while there were various accepted times at which the gedai might be displayed†, on this occasion it seems that Rikyū displayed the rolled-up scroll on the floor of the tokonoma (oriented so that the gedai would be easy to read)‡; and after their silence indicated that the guests were finished, he entered and proceeded to hang the kakemono in the toko, so that the guests could then inspect Yuán-wù’s writing.

___________

*Writing the gedai on a separate piece of paper (that was then glued to the back of the scroll) allowed the ascription to be lodged without physically damaging or altering the scroll itself (the glue, which was made from sticky-rice, was water soluble, and could be removed without difficulty). This was the dōbō‘s intention (since the gedai itself was originally considered to be a sort of inventory or cataloging aid).

According to the commentary on the Chanoyu San-byakka Jō [茶湯三百箇條] (this work is usually ascribed to Jōō, though Jōō himself held that the core entries were set down by Shukō: the earliest surviving manuscript was created by Jōō’s disciple Uesugi Kenshin about ten years after Jōō’s death; and includes not only Kenshin’s extrapolations, but also additional interlineal material added by Sen no Dōan and Dōan’s disciple Kuwayama Sōzen -- the different layers of commentary are not separated, or even separable, from each other), the proportions of the slip of paper on which the gedai is written should be calculated in the following way: “if the [honshi [本紙] -- the paper on which the scroll was written -- of the] bokuseki is 1-shaku 1-sun from top to bottom or less, this length should be divided into thirds, and the length of the gedai should be equal to one of the thirds. The width of the gedai should be equal to a sixth-part of its length. This is a secret matter.

“If the scroll is long and wide, or if it is extremely narrow for its length, in general the proportions of the gedai are determined in the same way as above; however, the details are secret:

“1) When [the honshi] exceeds 1-shaku 1-sun when measured top-to-bottom, that length is divided by four, and one of the fourths is discarded; then the remaining three are divided as above to give the length and width of the gedai.

“2) In the case of extremely long and narrow scrolls, the rule is that the length of the honshi was divided into four parts, and one of these quarters is discarded. The remainder was divided into quarters again, and a further fourth was deleted. From the length of the remaining three, the above rules were followed to determine the length and width of the gedai.”

The above secret material was based on Nōami’s [能阿弥] and Sōami’s [相阿弥] gedai. Since, as mentioned above, these were often pasted onto the backs of scrolls which lacked any sort of artist’s signature at all (either works that were in a poor state of preservation, or panels of a long horizontal scroll that had been cut into individual pieces based on content), it became essential to be able to verify that the gedai actually belonged to the scroll to which it was attached (forgeries of paintings were not uncommon; and one of the easiest ways to pass off a fake was by attaching an authentic gedai -- removed from some other scroll -- to it). Thus, these details provided the assessor with a very good way of determining whether the gedai actually belonged to the scroll to which it was attached, or not. Further details can be found in the post entitled The Three Hundred Lines of Chanoyu (Lines 261 - 270: Part 1, Lines 261 - 265). The quote comes from footnote 5 under line 263 (“The way to inspect a bokuseki’s gedai”).

The URL for that post is:

chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/62296322423/the-three-hundred-lines-of-chanoyu-lines-261

†Sometimes the gedai was displayed first, and after inspecting it, the scroll was hung up so that the guests could view that as well; and sometimes the scroll was already hanging in the toko when he guests entered the tearoom, and the inspection of the gedai took place later in the za (such as immediately before they left the room for the naka-dachi). The latter form was mostly used when the guests subsequently asked to inspect the gedai, while the former was used when the request was tendered before the host began his preparations (as was the case on this occasion).

‡It is not clear who the gedai on this scroll was written by -- though Ikkyū Sōjun or Shukō would seem to be likely candidates. This scroll was never a part of the Higashiyama collection, hence none of the dōbō would have been involved. The hyōgu [表具] (mounting) seems to have been designed by Shukō.

¹³Ko-ita ni furo ・ unryū-gama [小板ニ風爐 ・ 雲龍釜].

For this special occasion, it seems that Rikyū borrowed the old Temmyō kimen-buro that had belonged to Yoshimasa (and, later, Nobunaga).

The kama would have been the first small unryū-gama, which Rikyū designed to be used with this furo.

I assumed (when creating my sketch showing the general arrangement of the room under footnote 3) that Rikyū placed the ko-ita furo on the right side of the utensil mat, since this was the orthodox way of doing things in a room that had a dōko. Nevertheless, in light of the shōkyaku’s relationship to Jōō, and in deference to his feelings*, it is possible that Rikyū decided to place it on the left, in the manner used by Jōō during the middle period of his career†.

___________

*Sōkyū was Jōō’s brother-in-law, and a known champion of the teachings emanating from Jōō’s middle period (meaning the period prior to Rikyū’s return from the continent -- after which Jōō incorporated numerous changes in light of the new material that Rikyū brought back with him from Korea).

†Locating the ko-ita furo on the left (as shown above) was also the arrangement preferred by Hideyoshi (perhaps under the influence of Sōkyū: this manner of arrangement also makes it easier for the guests to see everything the host is doing, whereas placing the furo on the right tends to hide many of the host’s actions behind its bulk -- Hideyoshi was perennially fearful of being poisoned, a method of assassination said at that time to be preferred by the followers of the Ikkō-shu [一向宗], the Amidist sect of Buddhism with which most of the Sakai machi-shū-chajin were at least nominally affiliated), hence it might have felt “less controversial” to employ this version of the arrangement on the present occasion (not only out of respect for Sōkyū’s sense of propriety, but because several of the other guests were also employed as Hideyoshi’s tea masters).

That said, it could have been precisely for this reason that Rikyū may have decided to locate the furo on the right -- in order to illustrate to the assembly the theoretically appropriate way of doing things (less the habit of doing things in the way preferred by Hideyoshi induce a state of forgetfulness).

¹⁴Shiru saku-saku [汁 サク〰].

This was miso-shiru containing coarsely chopped greens from the kitchen garden. The chopped greens were added just before the soup was served, so they would still be crisp when eaten (this is what the onomatopoeaic saku-saku means).

¹⁵Shigi yakite ・ kamaboko [鴫 ヤキテ ・ カマホコ].

Shigi [鴫] means snipe* -- a shore-bird; a type of sandpiper. While Rikyū does not go into the details of its “roasting,” cooking the birds in the senba-iri [船場煎り] style† seems likely.

Kamaboko [蒲鉾] is boiled or steamed fish-paste. in Rikyū’s day the kamaboko was probably formed into cylinders (possibly hollow tubes, which insured faster cooking times), or flattened into patties, and then deep-fried in oil (by the shop that produced it) -- it could be offered to the guests as it was received from the shop (warm to cold), or be reheated before being served.

These dishes would have been accompanied by the service of several rounds of sake.

___________

*Shibayama Fugen’s manuscript, however, has kamo [鴨], meaning the wild duck. The kanji are similar; and perhaps shigi seemed a bit too “exotic” for the late Edo-period palate of the gentleman responsible for producing his copy of the Nampō Roku. (We must remember that making copies -- or even writing down notes -- while in the Enkaku-ji, was strictly forbidden. Thus the material could be committed to paper only after the person -- I do not believe the name of the person who made the original copy is actually known -- took his leave.)

That said, shigi was also served at a gathering mentioned in the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki [利休百會記] -- albeit in that case, it was mashed and formed into dango [團子], and served in a clear broth.

†Senba-iri [船場煎り] refers to a style of cooking employed in the food stalls located along the wharves at Sakai. It was used primarily for preparing small birds (and, incidentally, prawns as well). In this case, the entire bird (plucked, and with the head, feet, and innards removed) was threaded or tied onto a spit and roasted over a small wood or charcoal fire in a brazier, while basting them with a mixture of sesame oil, soy-sauce (or iri-zake [煎り酒]), sake, mirin, and crushed garlic. (The wood fire added an interesting dimension to the food’s flavor -- since in Rikyū’s day most home cooking was done over charcoal.)

¹⁶Asa-zuke [アサツケ].

Asa-zuke [淺漬け] are a simple kind of home-made tsuke-mono (the type is often referred to as o-shinkō [お新香] today). Naturally crisp vegetables -- such as immature cucumbers, daikon, hakusai, Japanese eggplant, and the like -- are either dusted lightly with salt (usually small slivers of dried kombu [昆布] -- kelp -- are added during this step as well), kneaded with the fingers (to distribute the salt evenly), and then left to stand under a light weight (which helps to press out the water).

Alternately, the vegetables and kombu can be placed in a brine solution to pickle.

In either case, they are left to stand anywhere between several hours and overnight. The process removes the extra water, increasing the natural crispness of the vegetables.

¹⁷Senbei ・ yaki-guri [センヘイ ・ ヤキクリ].

These were the kashi:

- senbei [煎餅], rice crackers, which were usually obtained from a professional confectioner (and often, in the case of Rikyū’s chakai at least, received as a gift from one of the guests* -- rather than being procured for this purpose by Rikyū himself); and.

- yaki-guri [焼き栗], chestnuts roasted over a charcoal fire.

___________

*Unlike in the present, money was not considered an appropriate thank-gift for the guests to give to the host. Elegant senbei, or other things of that sort, were preferred. Since the guests were all chajin, they would likely have bought such a gift as a group, after consulting with each other.

¹⁸Go [後].

The goza.

As for the kane-wari:

- the scroll remained hanging in the tokonoma, and so it remained han [半];

- in addition to the ko-ita furo, the room contained the mizusashi (with the sa-tsū-bako arranged in front of it, and the hishaku resting on top -- all of which counted as a single unit), and so was chō [調].

Han + chō is han, which is appropriate for a gathering held during the daytime.

¹⁹Toko sono-mama [床其儘].

The kakemono remained hanging in the toko, as it had been since the guests finished inspecting its gedai during the shoza.

²⁰Mizusashi Shigaraki, ue ni hishaku [水指 シカラキ、上ニヒシヤク].

This was Rikyū's Shigaraki mizusashi.

The hishaku was placed on top, with the butt end of the handle touching the second kane, as explained in the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 2 (46): (1587) Eighth Month, Second Day, Morning*, under footnotes 14 and 16.

___________

*The URL for that post is:

http://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/184163345058/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-2-46-1587-eighth-month

²¹Sa-tsū-bako [棚ニ茶通箱].

This entry is marked with a red dot, indicating its importance. This would have been a futatsu-iri sa-tsū-bako [二つ入り茶通箱], a sa-tsū-bako made to hold two containers of tea (this is the kind usually seen today* -- though what kind of lid the box may have had cannot be verified: the box shown below has what is known as a yarō-buta [藥籠蓋]).

The sa-tsū-bako was probably placed in front of the mizusashi†.

__________

*Based, apparently, on the precedent of this chakai -- though this chakai is, in fact, not representative of the way that Rikyū usually handled the sa-tsū-bako (when he was sending a gift of tea to someone else). Rather, it shows the way that Jōō may have been doing things during his middle period (this is where the machi-shū tea of Sōtan, on which modern day chanoyu is based, originated).

This anomaly has fueled certain suspicions that this chakai is at least in part spurious -- and was possibly modified or inserted into the kaiki to provide a Rikyū-based precedent for the way that the Sen family was handling the sa-tsū-bako and its (by that time, “secret”) temae.

†Shibayama Fugen, however, notes that if the chaire contained in the sa-tsū-bako (he seems to have believed it to have been Rikyū’s Shiri-bukura chaire [尻膨茶入]) was a meibutsu, then the sa-tsū-bako should be placed on the central kane.

In this case, rather than an ordinary ko-ita, which measures 9-sun 5-bu square (shown on the left in the following sketch), a specially made smaller one (measuring 8-sun square -- the arrangement of which is shown on the right) could be used. This smaller version of the shiki-ita was arranged according to the usual rules: 5-sun from the far end of the mat, and 9-me from the heri. The effect, then, was to move the furo diagonally away from the central kane, making it possible to place the chaire -- or, in this case, the sa-tsū-bako -- on the central kane (without any danger that the heat from the furo would be close enough to damage the tea).

As with the ko-ita, this smaller shiki-ita (which was Rikyū’s creation) could only be used with a large furo (meaning a furo measuring between 1-shaku 1-sun and 1-shaku 2-sun in diameter -- whether made of iron, or of lacquered clay).

Nevertheless, Fugen admits that, in this particular case, he is unsure where the box would have been displayed (and seems inclined, on second thought, to imagine that it was more likwly placed in front of the mizusashi).

Tanaka Senshō, meanwhile, suggests that the sa-tsū-bako might have been displayed in the toko (along with the scroll, which still remained hanging as it had been during the shoza) -- though doing so would have made the apparent kane-wari unworkable (and so Rikyū probably did not do this). Nevertheless, in such a case the host (immediately after bringing the chawan into the room -- which he temporarily placed on the left side of the mat) would go to the toko and retrieve the sa-tsū-bako (for this reason, the box would have been displayed on the side of the toko closer to the toko-bashira, so that the host would not disturb the shōkyaku when he went to pick up the sa-tsū-bako). After bringing the box back to the utensil mat, the host would cut the box open with a knife, as explained under the next footnote.

²²Tadashi, uchi ni Shiri-bukura ・ ko-natsume [但、内ニ 尻フクラ ・ 小ナツメ].

The chaire is generally assumed to be Rikyū's meibutsu Shiri-bukura chaire [尻膨茶入] (shown below). But if that was the case, the source of the tea it contained (whether matcha ground that morning by Rikyū, or the gift-tea that was received from Sōkyū -- over which Rikyū seems to have made quite a fuss) becomes a matter for confusion*.

According to both Shibayam Fugen and Tanaka Senshō, the Shiri-bukura chaire contained tea that would be served as koicha, while the ko-natsume contained tea intended for use as usucha -- and this is represented, by both of them, as being the traditional assessment of the contents of the sa-tsū-bako that was held by all of the scholars (since the time of Tachibana Jitsuzan himself, and so from the beginning of the study of this document) associated with the Enkaku-ji and the Nampō Roku scholarship.

This latter assertion, too, is problematic as well, since (at least in the time of Jōō and Rikyū) the ō-natsume [大棗] was generally used for usucha, while the ko-natsume (according to Jōō -- who created both of these kinds of chaki†) was supposed to be used for koicha. If, as some suggest, the tea in the Shiri-bukura was Rikyū’s own tea, then the tea in the ko-natsume being intended for usucha is equally odd -- since the tea used for usucha was either left-over koicha‡, or ground from the inferior-quality tea leaves that had been used as packing material in the cha-tsubo. In either case, for Imai Sōkyū to promise to send a container of matcha, and then send over such poor quality tea, would be almost insulting -- and, again, does not conform with what we know of Sōkyū’s character (since he was, if anything, inclined to be self-promoting, and very concerned about “face”: if anything, Sōkyū would have sent the highest-quality tea he had, and made quite sure that Rikyū respected it properly by preparing it as koicha -- especially if this were the only tea from Sōkyū that would be served during the chakai). Furthermore, if the matcha received from Sokyu had really been such poor tea, Rikyū would have hardly made such a fuss over it

Gift tea was (originally -- and this custom was still current in the time of Jōō and Rikyū) packed into the sa-tsū-bako by the person giving the tea, and that person then sealed the box by pasting a paper tape around the place where the lid joined the sides, and applied his name-seal to the place where the two ends of the tape met (which was considered the side of the box that would face toward the guests -- meaning that the container or containers of matcha were always oriented accordingly). The host opened this tape with a small knife, using three cuts: first he cut from just beyond the name-seal away from himself (and so around the box to the side opposite the name-seal); then from just beyond the seal and toward himself (the two cuts, then, meeting on the far side of the box from that were the seal had been impressed). Then the sa-tsū-bako was passed around for haiken (with the name-seal still remaining uncut -- to verify to the guests that the contents of the box were as packed by the giver), while the host dusted the utensil mat with the habōki. Then, after the box was returned, the host took the knife and cut through the name-seal, thus freeing the lid, and so allowing him to open the box and remove the container or containers of matcha. This process is clearly described in the Nampō Roku.

It is unlikely, then, that the sa-tsū-bako contained one kind of tea prepared by Rikyū (in his Shiri-bukura chaire) and another tea (in the natsume) prepared by Sōkyū. If any of the tea was from Sōkyū, then all of the tea in the sa-tsū-bako would have been from him (and the box sealed with his name-seal); and if Rikyū still intended to use his own tea (ground that dawn and put into his own chaire, the Shiri-bukura), then the gift tea in its sa-tsū-bako would have had to be placed elsewhere until the service of tea from the Shiri-bukura was finished (since the host’s tea always took precedence in such cases). Putting the tea containers together in the same box was simply not done during Rikyū’s period -- since this would have involved cutting off the donor’s seal beforehand, making the entire process of cutting off the tape nonsensical (Rikyū’s introductory remark that the tea had come from Sōkyū certainly implies that all of the tea that was served was from him -- that the sa-tsū-bako was from Sōkyū, and so would have been sealed with his name-seal).

As an separate comment added here, Shibayama Fugen adds that, if the chaire was a karamono piece (as was Rikyū’s Shiri-bukura chaire), then, after opening the box (and seeing what it contained), the host would quietly go out to the katte and bring in a chaire-bon, and so serve the first tea using the bon-date temae**.

__________

*The idea was always to prevent the tea from coming into contact with the air. Thus, the containers of matcha were always tied into shifuku (or, for gift tea sent to someone in newly-made natsume, purple, fukusa-shaped furoshiki) and loaded into the box, which was then sealed with a paper tape. The seal was not broken until the box was opened, before the eyes of the guests (according to the Nampō Roku), during the koicha-temae.

Therefore, Rikyū could hardly have received two containers of gift tea from Sōkyū, and then transferred one of them into his own chaire (since that would expose that tea -- which would have been the better of the two -- to the air, potentially ruining it, and causing grave insult to Sōkyū). Neither could he have included his own chaire of tea in the box with the gift tea (in a ko-natsume), since the box would have been packed and sealed by Sōkyū (in his own home, immediately after grinding the tea). It may have been possible that Sōkyū borrowed Rikyū's chaire; but it seems that people of that period did not usually do such things -- since there would have been nothing to prevent the borrower from showing the chaire secretly to his friends (though, given Sōkyū's status -- and his personal commitment to maintaining his reputation -- it is unlikely that he would have breached Rikyū's trust in this way). Therefore, the most likely possibilities -- assuming that this kaiki is authentic (something which these particular details tend to make less likely) -- are either that Sōkyū used his own shiri-bukura chaire (which has not been identified) -- if, indeed, a shiri-bukura chaire even originally figured into this -- or that he borrowed Rikyū's chaire for this purpose.

However, all of that aside, if things were done “correctly,” the sa-tsū-bako would have contained two natsume (perhaps a ko-natsume of koicha and an ō-natsume of tea intended for usucha -- though it is also possible that it contained two ko-natsume, both holding koicha-quality tea), and that the words “Shiri-bukura chaire” were added by someone who wanted to make this sa-tsū-bako temae appear identical to what the Sen family was teaching.

Imai Sōkyū, it must be remembered, was married to Jōō's sister (I have said this before; but this point is extremely important if one wishes to understand Sōkyū and his motivations); and his practices tended to mirror Jōō's own usages from his middle period (during which time Jōō preferred using one variety of matcha for koicha, and a different, slightly lower-quality tea for usucha); he also had an extensive collection of high-quality tea utensils (a number of which had come from Jōō’s collection -- taken by Sōkyū to reimburse himself for the expenses of raising Jōō’s son Sōga). But I have never seen it alleged (in contemporary documents) that Jōō placed a chaire and a natsume together in the sa-tsū-bako; nor that Jōō taught that the sa-tsū-bako should be opened by the host (before the chakai began) and then repacked so that it would contain his own chaire along with the gift tea (whether the chaire also contained gift tea, or tea ground for the occasion by the host).

All of the documented instances of the use of a sa-tsū-bako from Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period clearly imply that:

- the sa-tsū-bako contained only the gift tea (never tea prepared by the host);

- that the gift tea was to be placed in newly made natsume (or other new lacquerware tea containers) of an appropriate size (this was done precisely so that it would be the tea that was important to the guests, not the container in which it had been sent);

- and, that the sa-tsū-bako was packed by the donor, and sealed with his name seal, and that the sa-tsū-bako was not to be tampered with until the box was cut open in front of the eyes of the guests, who would then be served the tea it contained (this because it was the reputation of the donor that was at stake, rather than that of the host: tampering with the box could make the donor loose face, if the tea proved to be bad).

Tachibana Jitsuzan, Shibayama Fugen,Tanaka Senshō, and the group of scholars affiliated with the Enkaku-ji, however, were all products of their age. Since they only knew the sa-tsū-bako temae taught by the Sen family (which holds that the sa-tsū-bako was prepared by the host, to contain a chaire of his own tea, plus a natsume or other container of gift tea), it seems that none of them were able to imagine anything different -- even though the differences are actually described elsewhere in the Nampō Roku itself. This kind of inflexible attitude remains the bane of Nampō Roku scholarship, even to this day.

†Since Imai Sōkyū was not only married to Jōō’s sister, but also the de facto guardian of Jōō’s son (and heir), he appears to have been a stickler for adhering to Jōō’s teachings and practices, at least in so far as he was aware of them. (Sōkyū, together with many of the machi-shū, had a sort of falling out with Jōō during the last year of his life -- after Jōō began to modify many of his teachings in light of the new information that Rikyū had brought back with him from the continent. This last one-year period is what saw the incredibly rapid evolution of the small room, along with the advancement of extremely wabi practices -- in contradistinction to what Jōō had championed for most of his professional life.) Thus, it is highly unlikely that Sōkyū would have so wantonly rejected one of Jōō’s basic teachings by using the ko-natsume for a purpose for which it had not been intended.

‡In other words, koicha-quality matcha left over from tea that had already been placed in a chaire and used to serve tea at an earlier gathering (it was considered rude for all of the tea in the chaire to be used, in case the guests wanted to drink more: thus, the host always selected a chaire that was larger than necessary, and the tea container was always filled fully, with the intention being that a certain amount should always remain in the container at the end of the temae, as a sign of the host’s courtesy and concern for his guests): such tea could only be used later for usucha, because it had already been exposed to the air too much -- meaning that the volatile constituents (which contribute heavily to both the aroma and taste of the tea) would have been lost, for the most part.

**Or, more specifically, a meibutsu karamono chaire (that had been paired with a tray). In Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period, only karamono chaire that had been paired with a tray were used for bon-date (by Rikyū’s day, ko-Seto chaire were also acceptably used in this way -- assuming that they had been paired with a tray) -- and, since the tray had to agree with the proportions of the chaire exactly (according to both Jōō and Rikyū), it would have been impossible for the host to simply bring out any “random” tray, historically speaking, at this point in time (the idea of using “any small tray” began with Sōtan and his followers, as a result of ignorance of Rikyū’s teachings -- or perhaps as a deliberate rejection of the way that Rikyū had done things), on the spur of the moment, after finding such a chaire in the sa-tsū-bako . This highlights (albeit inadvertently, so far as Shibayama Fugen’s comment is concerned) the difference between practices in Rikyū’s day and his own (which, as is also true of modern-day chanoyu , followed directly from Sōtan’s machi-shū style of chanoyu).

“For the record,” Jōō's chaire-bon was supposed to be (exactly) 3-sun 5-bu larger on all four sides than the chaire that would be used on it; Rikyū’s chaire-bon (which was notably smaller than Jōō’s tray), was 2-sun larger on all four sides. These measurements were supposed to be exact (the tolerence is less than 1-bu in the case of all of the old chaire and their trays that have survived), and even modest deviations were generally rejected. If one had a tray that conformed with the chaire, and that chaire was deemed worthy of being used on a tray, then one did bon-date. If either of these conditions were not true, then the chaire was supposed to be used without a tray.

²³Habōki [羽帚].

The habōki (which was a larger one, made from feathers that were between 9-sun and 1-shaku long -- the kind that is usually seen today) was placed on the left side of the mat, next to the heri.

According to Shibayama Fugen, it was used to dust the utensil mat just before the sa-tsū-bako was (finally) cut open and the first container of tea taken out.

²⁴Su [ス].

The utensils that follow this notation (the chawan; and, though not specifically mentioned in the kaiki, the koboshi and futaoki) were brought out from the katte at the beginning of the koicha-temae, rather than being displayed in the room when the guests entered the room for the goza.

Su [ス] is an odd modification of the kanji mata [又], used consistently in this book by Tachibana Jitsuzan. It is intended to mean “also,” “and again.”

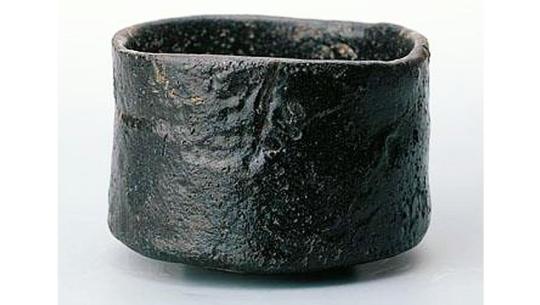

²⁵Chawan kuro, ori-tame [茶碗 黒、 折撓].

Though usually assumed to be one of Chōjirō’s early black bowls, it seems more likely to have been the hiki-dashi-kuro chawan that Furuta Sōshitsu made for Rikyū the year before -- the chawan that is shown below (which bears Rikyū's kaō, as a mark of his ownership, on the bottom) -- since Rikyū would have been extremely sensitive to avoid any charges of self-promotion leveled after the fact by this group of guests.

Consequently, it does not seem that Rikyū would have used one of Chōjirō's bowls (since those bowls were known to have been produced under Rikyū’s watchful gaze -- and those not approved by him were destroyed), since a certain reticence would have seemed to be called for during this chakai. His own creativity would have been sufficiently demonstrated by the use of one of his own chashaku -- made to accompany the main tea container, Rikyū's meibutsu Shiri-bukura chaire [尻膨茶入] -- and the use of a take-wa [竹輪] as the futaoki (below) -- and the other unimportant (though necessary) utensils.

While nothing is said, it seems most likely that Rikyū would have used a take-wa [竹輪] as his futaoki, and a mentsū [面桶] as the koboshi.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Favorite tweets: 今夜のイベント主催者は、もってる!台風直撃タイムを深夜にずらしたよー!遊びにきてね☆「猫も杓子もvol.3」〜はいからさん 「LONG TIME COMING!!」レコ発名古屋〜出演:リバーヴスフクラ本舗ジャッケンボーノはいからさん松石ゲル(DJ)開場18:30開演19:00当日¥2,500 D別— 磯 たか子 (@isosounds) July 28, 2018

http://twitter.com/isosounds

0 notes

Text

札幌市東区Nさま宅へHUKLAのソファーセットを出張買取

専門家

本日も当社のブログをご覧頂きありがとうございます。

片付屋.comです🎶

本日は作業実績をご報告いたします!!

–

ここ数日でサイトのページ追加を行っていますがうまくことが進みません。

これを盛り込もう、あれを入れようと思っていると調べるのに時間がかかったりしてしまうのです。

専門家ってやはりすごいんだと改めて実感しました。

そんな表をもらえるように頑張らないと・・・。

札幌市東区Nさま宅へHUKLAのソファーセットを出張買取

昨日は札幌市東区Nさま宅へHUKLAのソファーセットを出張買取させていただきました。

ドイツのメーカーHUKLA。

3人掛けと1人掛けを2脚の計3脚を買取させていただきました。

通常ソファーは木材で枠取りをし加工するため、重量はかなりあります。

ですがフクラのソファーはウレタン素材のため軽く女性でも持ち上げることができるくらいの軽さ。

年数が経ってもへた…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

いい家具と、いいカーテンと。【③HUKLA 日本フクラ】

糸の素材、撚り方、織り方、編み方、染め方、加工の仕方など。

カーテンをかたちづくる、すべての要素にこだわったのがアスワンの『AUTHENSE(オーセンス)』です。

その見本帳に掲載している、家具メーカー様にご協力いただいた、家具・椅子張り生地・カーテンのコーディネートをご紹介。

さらに『Wall to Wall CARPET』から、心地よさとサステナブルにこだわったカーペット『アスオーシャン』も合わせました。

家具メーカー:日本フクラ @hukla_official

商品名/品番:ルベル 2P片肘ソファ/T565-06、コーナーカウチ/T565-31L(張地:18-3929、脚部:アルミ脚(BL))、ヘッドレスト/T565-59、背クッション/T565-35・36・37(張地:18-3929)、カストール リビングテーブルSサイズ/SLT528-40R(トップ:スモークガラス(SG))、リビングテーブルMサイズ/SLT528-60R(トップ:磁器質タイル ホワイト(CWH))

カタログ:AUTHENSE edit10

カテゴリ:Grand Harmony/stylish

名前:BELFALA/ベルファラ

品番:C1004

機能:防炎、ウォッシャブル

カタログ:Wall to Wall CARPET edit1

カテゴリ:Sustainable

商品名:アスオーシャン

品番:OCN-43

機能:防炎、遮音、床暖対応、工事対応(グリッパー施工可)

くわしくはお近くの #インテリア専門店 またはプロフィール @aswan_jp のリンクから『AUTHENSE』をご覧ください

instagram

#インテリア#インテリアコーディネート#インテリアコーデ#コーディネート#カーテン#オーダーカーテン#オーセンス#authense#curtains#カーテンレール#装飾カーテンレール#リフォーム#リノベーション#家具#ソファ#照明#フクラ#hukla#日本フクラ#カストール#インテリア好き#インテリア選び#アスワンのカーテン#インテリアショップ#インテリア専門店を元気にする#アスワン#aswan#アスワンのある暮らし#アスワンと家具#インテリア専門店

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (12): (1587) Twelfth Month, Eleventh Day, After the Morning Meal.

12) Twelfth Month, Eleventh Day¹; following the morning meal, fu-ji [不時]².

◦ Three-mat room³.

◦ (Guests:) Toda minbu [戸田民部]⁴, Ikeda Bicchū [池田備中]⁵.

First⁶:

﹆ One bowl of usucha was served⁷.

◦ Mizusashi Bizen [水指 備前]⁸;

◦ nakatsugi [中次]⁹.

▵ Kobu aburite ・ kuri [コフ アフリテ ・ 栗]¹⁰.

◦ [Then,] using the na-kago [菜籠], a full-set of charcoal was laid [in the ro]¹¹.

◦ Kama unryū [釜 雲龍]¹².

◦ On the tana, the kōgō and habōki¹³.

◦ Toko Tōyo [床 東與]¹⁴ -- [it had been] hanging from the beginning¹⁵.

◦ After [the scroll in the] toko was rolled up¹⁶, in a take-zutsu [竹筒], plum [blossoms]¹⁷.

◦ Chaire Shiri-bukura [茶入 尻フクラ], on [its] tray¹⁸;

◦ temmoku [天目]¹⁹;

◦ mizusashi Bizen [水指 備前] -- [the same] as in the beginning²⁰.

_________________________

¹Jūni-gatsu jūichi-nichi [十二月十一日].

The Gregorian date for this chakai was January 19, 1587.

²Asa-han ato fu-ji [朝飯後 不時].

In other words, after taking the morning meal, it was spontaneously decided to have a chakai.

Both guests were numbered among Hideyoshi's personal guards, and had probably been on guard duty the night before -- after which they would have been served breakfast before being dismissed. It seems that the two decided to stop by Rikyū's residence for chanoyu on their way home.

³Sanjō shiki [三疊敷].

This entry is problematic. The “3-mat room” that is occasionally mentioned in his kaiki generally refers to Nambō Sōkei's Shū-un-an (illustrated below), which he seems to have borrowed when receiving certain guests in his own home would have proven inappropriate*.

That said, there is no indication that this gathering was held in Sakai -- and, indeed, it would have been difficult for the guests to “suddenly” visit Rikyū there after taking their morning meal elsewhere, if the chakai were held in Sakai (in addition to the distance between Ōsaka and Sakai, Japanese citizens -- and particularly important officials such as these -- could not freely enter Sakai on the spur of the moment).

While Shibayama Fugen's entry concurs with what is found in the Enkaku-ji copy of the text, Tanaka Senshō states that the room was a nijō shiki [二疊敷] -- which would mean the two-mat room in Rikyū's residence.

In fact, though Tanaka does not mention that his copy deviates from other versions† (as he usually does when any of the then-known texts vary from the others), given that this was a fu-ji no chakai [不時の茶會], the two-mat room in Rikyū's official residence within Hideyoshi's Ōsaka castle complex would be a more logical place for these two important warriors to visit on the spur of the moment.

The kaiki is rather disorganized, which suggests that it may not have been part of Rikyū's manuscript, but added (from other sources) by someone else at a later date.

__________

*A “three-mat room” is mentioned in some of the kaiki written by other people (such as Kamiya Sōtan), but the details are confusing -- for example, though the room is called a three mat room (with 5-shaku toko -- similar to the original Tai-an room), it seems that there was either a daime appended to the room, or else the maru-jō utensil mat was used like a daime (perhaps it had a sode-kabe at the end, like the original Tai-an). Since Tanaka Senshō's manuscript states that it was a 2-mat room, and in the absence of any clear details, it seems best to treat this as a 2-mat room -- since this “3-mat room” is only mentioned this once (all other references clearly refer to the Shū-un-an).

†Tanaka Senshō used a handmade copy of the text as his teihon [底本], which was copied much earlier than the text consulted by Shibayama Fugen.

It is possible that the reading of the Enkaku-ji text is unclear -- the document shows a certain amount of insect damage which might make a two (ni [二]) seem to be a three (san [三]). Unfortunately, circumstances now make it difficult for me to confirm this.

⁴Toda minbu [戸田民部].

This refers to the bushō [武将] Toda Katsutaka [戸田勝隆; ? ~ 1594], who was the Assistant Vice-minister of Public Affairs (minbu-no-sunaisuke [民部少輔], also pronounced minbu-no-shōyu).

Katsutaka had been a personal retainer of Hideyoshi's, serving in his mounted guard, and so was in a position of great trust (since he was permitted to appear armed in Hideyoshi's presence). He participated in many of Hideyoshi's campaigns, and was part of the committee that negotiated the truce that formalized the cessation of hostilities following the First Invasion of the Continent. However, he was taken ill on the return journey, and died before reaching his homeland.

Katsutaka was also one of Rikyū's personal disciples, and was one of the small group of men permitted to receive the gokushin teachings by Hideyoshi.

⁵Ikeda Bitchū [池田備中].

This was the daimyō Ikeda Nagayoshi [池田長吉; 1570 ~1614], who held the junior grade of the Fifth Rank as Governor of the province of Bitchū (Bitchū-no-kami [備中守]). He was also one of Hideyoshi's personal retainers, and had the distinction of having been adopted by Hideyoshi.

Nevertheless, at the battle of Sekigahara (1600), Nagayoshi supported the claims of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and was afterward rewarded with Tottori castle (Tottori-jō [鳥取城]), which remained in his family throughout the Edo period.

In the Rikyū Hyakkai Ki, Ikeda Nagayoshi appeared as a fellow guest together with Toda Katsutaka at a chakai that Rikyū gave for them on the 10th day of the First Month of Tenshō 19 (1591), also in the morning, suggesting that (on both this and the other occasion) they visited Rikyū on their way from Hideyoshi's residence.

⁶Ubu [初].

Though the kanji is the same, ubu [初] does not mean the shoza, as it does in most of the entries; it means “first” or “beginning” -- that is, that the service of usucha happened at the beginning of this fuji-no-chakai.

The scroll in the toko had been hung up at dawn, after the room was swept, at which time the fire would have been put into the ro, and a large kama (perhaps the Temmyō ko-arare uba-guchi gama [天命小霰姥口釜], below, that Rikyū used at his previous chakai) placed over it to heat -- despite the fact that nobody had been invited for chanoyu that day.

When the two men arrived, noticing that the kama from dawn was still boiling, Rikyū invited them into the small room for usucha (using some left-over matcha that he happened to have on hand), after which he removed the larger kama, rebuilt the fire (while simultaneously having some fresh matcha ground in the mizuya), and put the small unryū-gama, filled with fresh water, on to boil, so he could serve the guests especially delicious koicha.

Shibayama Fugen suggests that the temae at the beginning of the chakai, at which only one bowl of usucha was served*, was probably a hakobi-temae [運び手前], meaning that Rikyū brought the mizusashi, chawan and nakatsugi, and hishaku, futaoki, and koboshi, out from the katte, served tea, and then took these things away (perhaps without haiken)†.

Tanaka Senshō, furthermore, adds that the kōgō and habōki were displayed on the tana from the start, so that the kane-wari for the “shoza” was:

◦ toko: kakemono, han [半];

◦ room: kama, han [半];

◦ tana: kōgō and habōki, arranged side by side, chō [調].

Han + han + chō equals chō, which is appropriate to the shoza -- even though usucha was served.

__________

*Though modern-day conventions suggest a single large bowl of usucha was passed around for all to share, in Rikyū's day offering each guest an individual bowl of usucha would have been the usual way to do this.

†That said, this kind of temae was usually considered more appropriate to a 4.5-mat room, since in the smaller rooms, the host was supposed to keep his entrances and exits to a minimum. That is why the room had a built-in tana.

Nevertheless, the present chakai seems to provide an exception -- since there would be no way to display both the tea utensils and the kōgō and habōki at the same time while still adhering to the rules of kane-wari -- and good taste.

⁷Usucha ippuku [薄茶一服].

Probably each guest was served one bowl of usucha -- even though, according to the modern custom, zen-cha [前茶]* is usually served as sui-cha [吸い茶]†. Rikyū writes the word ippuku to indicate that the service of usucha was truncated -- rather than allowing the guests to drink as much as they wanted‡.

__________

*Zen-cha [前茶] means usucha served at the beginning of a chakai or chaji.

The reader must be careful not confuse this with Zen-cha [禪茶], which means Zen-tea (or Zen and tea).

†Sui-cha [吸い茶] means a single bowl of tea is shared by all the guests, being passed from hand to hand with each drinking a portion.

‡As is usual when usucha follows koicha -- in the ordinary case where usucha follows koicha, the limiting factor would be only how much matcha remains in the tea container.

⁸Mizusashi Bizen [水指 備前].

This seems to have been the same mizusashi that Rikyū used during the previous chakai.

⁹Nakatsugi [中次].

A nakatsugi* was a storage container, used to keep tea for several days (so it would not spoil, and could still be served as usucha).

This suggests that Rikyū was using tea that had been ground for a previous chakai to serve as usucha first -- while the matcha that he would serve as koicha was being ground in the mizuya.

Though nothing is said about the chawan, Rikyū may have used the same one that he mentions later in the kaiki -- apparently his Seto-temmoku [瀬戸天目], used without a dai.

As for the other things, Rikyū would have used an ori-tame [折撓] of the usual length†, as well as a take-wa [竹輪] and mentsū [面桶].

__________

*While Rikyū clearly states when he used the nakatsugi that was made for him by Tenka-ichi Seiami [天下一盛阿彌] (Hideyoshi's personal lacquer artisan), this nakatsugi would have been an ordinary storage container -- that period's equivalent of Tupperware.

†He probably changed the chashaku afterward for a smaller one, made to match the bon-chaire that he used when serving koicha during the latter part of the chakai.

¹⁰Kobu aburite ・ kuri [コフ アフリテ ・ 栗].

After serving his guests a bowl of usucha (essentially, to wash down their breakfasts -- which they had probably taken in Hideyoshi's residence), Rikyū offered them some light refreshments (to prepare them for the koicha that would be served later).

This consisted of toasted kelp and roasted chestnuts†.

__________

*Kobu [コフ = こぶ] is usually pronounced (and written) kombu [こんぶ = 昆布] today.

†Kuri [栗] is Rikyū's abbreviated way of writing yaki-guri [燒栗].

¹¹Na-kago ni te issumi [菜籠ニテ一炭].

This was Rikyū's na-kago sumi-tori [菜籠炭斗].

Issumi [一炭] means a full set of charcoal. Since the fire had been laid at dawn, while the guests had arrived after the morning meal (which was generally served in the middle of the morning), the charcoal would have mostly burned away by the time that Rikyū finished serving a bowl of usucha to each of the guests immediately after they arrived. Therefore, after taking the kama out to the mizuya*, he would have collected the embers together into the middle of the ro, and then laid a full set of charcoal around them.

After adding the incense to the ro, Rikyū would have returned to the katte and brought out his bamboo jizai (which he suspended from the hook attached to the ceiling), and then brought out the wet small unryū-gama, which he suspended over the ro†.

__________

*It would not be reused, since a large kama would take too long to return to a boil. Also, since the matcha was being ground freshly, pure water that had not been boiling in the kama too long would make for the best-tasting koicha. Thus, Rikyū substituted the small unryū-gama for the other, before the eyes of the guests, during the sumi-temae.

†Given its small size, the kama would begin to boil in around 15 minutes, so that after the sumi-temae, the guests would have gone out to the koshi-kake for the naka-dachi -- and to use the restroom -- and they would have been ready to return about the time that the kama began to boil.

¹²Kama unryū [釜 雲龍].

This was the second small unryū-gama [小雲龍釜], with matsu-gasa kan-tsuki [松笠鐶付] and a cast-iron lid.

It was suspended over the ro on Rikyū's abura-dake jizai [油竹自在], using his bronze kan and tsuru.

¹³Tana ni kōgō ・ habōki [棚ニ 香合 ・ 羽帚].

The kōgō would have been Rikyū's ruri-suzume [瑠璃雀], which was the one that he ordinarily used with the ro.

And the habōki would have been a go-sun-hane, as appropriate to the small room, most likely made of shima-fukurō [嶋梟] feathers, as shown above.

¹⁴Toko Tōyo [床 東與].

This refers to a bokuseki written by the Yuan dynasty monk Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú [東陵永璵; 1285 ~ 1365]* (whose name is pronounced Tōryō Eiyo in Japanese).

He is said to have been related to the great Chán master Wúxué Zǔyuán [無學祖元; 1226年 ~ 1286] (Mugaku Sogen in Japanese). Both Wúxué and Dōnglíng emigrated to Japan in order to spread the orthodox Chán teachings.

Dōnglíng Yǒng-yú was a follower of the Sōtō sect [曹洞宗] of Chán; and, as mentioned above, he came to Japan in Shōhei 6 [正平六年] (1351). Although he was a monk of the Sōtō Shū, he served as the abbot (jūji [住持]) of a number of important Japanese temples that had no affiliation with that sect, among which were the Tenryū-ji [天龍寺] and Nanzen-ji [南禪寺] in Kyōto, and the Kenchō-ji [建長寺] and Enkaku-ji [圓覺寺] in Kamakura.

The kakemono in question was more likely the hōgo [法語] that is shown above.

___________

*When writing this abbreviated version of his name (it uses the first and last of the four kanji), Rikyū has mistaken the second kanji -- writing yo [與] (a kanji found in his own childhood name of Yoshirō [與四良]), rather than yo [璵].

According to this form, the name should have been written Tōyo [東璵].

¹⁵Hajime yori kakaru [初よりカヽル].

In other words, the scroll, while mentioned here, was actually hanging in the tokonoma when the guests entered the room.

This kaiki was set down in a very haphazard manner.

¹⁶Toko makite [床巻テ].

This is one of Rikyū's abbreviations, and means that the scroll was rolled up, and removed from the toko. (It does not mean, as Tanaka Sensho implies, that the rolled-up scroll was displayed on the floor of the toko*.)

__________

*Sometimes a scroll was arranged in this way, to display its gedai [外題] -- a sort of title (it usually included the name of the artist responsible for the scroll) that was written on a small slip of paper, which was glued to the back side of the scroll near the roller.

However, scrolls were displayed in this way first, and only after the guests had inspected the gedai was the scroll hung up so they could look at the honshi.

¹⁷Take-zutsu ni ume [竹筒ニ梅].

As discussed in the previous post, prior to the summer of 1590, the word take-zutsu [竹筒] referred to what is otherwise known as an oki-zutsu [置き筒], a length of bamboo that was stood on an usu-ita on the floor of the toko, for use as a hanaire.

Given the time of year, the plum blossoms were probably of the early-flowering pink variety.

This entry begins the list of the things displayed at the beginning of the goza. In terms of kane-wari:

◦ toko: chabana, han [半]*;

◦ room: kama, mizusashi (with the bon-chaire and temmoku placed, side by side, in front of it), chō [調];

◦ tana: nothing, making it chō [調].

Han + chō + chō equals han, which is appropriate to the goza.

__________

*As mentioned above, Tanaka Senshō, in his commentary on the kane-wari, inexplicably argues that the kakemono, after it was rolled up, was left in the toko (this interpretation of toko makite [床巻テ] actually goes against the way he has understood these words on previous occasions), with the chabana added to it (though where it may have been placed -- or perhaps he imagines that it was hung up on the hook? -- he does not venture to say). This throws the entire kane-wari scheme off; so that he then has to argue that the bon-chaire must be counted separately from the mizusashi in order for the total to be han [半].

This is what happens when one is playing with disembodied words, rather than approaching the matter with an understanding of what the utensils actually are.

¹⁸Chaire Shiri-bukura bon ni [茶入 尻フクラ 盆ニ].

The chaire that he named Shiri-bukura [尻膨]* was Rikyū's treasured karamono ko-tsubo chaire [唐物小壺茶入].

This chaire holds sufficient matcha to serve two, or possibly three, guests. It would have been filled with the just-ground matcha.

The tray is exactly 2-sun larger than the chaire on all fours sides. That means that the bon-chaire can be placed in front of the mizusashi and the chaire will be separated from it by 2-sun, just like a chaire without a tray. Consequently, with respect to kane-wari, the mizusashi and the things in front of it are counted together as a single unit (just as when an ordinary chaire is displayed in front of the mizusashi)†.

Furthermore, for the same reason, the temmoku-chawan (without a dai) could be displayed on the mat next to the bon-chaire while still adhering faithfully to the teachings of kane-wari‡.

And though not mentioned, Rikyū would have used a (different) ori-tame (chashaku), one that he had made to match this bon-chaire.

__________

*The name comes from its shape. The widest part of its circumference is at the hips, which is what the name means.

†This is true for all of the chaire that Rikyū paired with trays (though it is usually not true for trays paired with chaire by most other people of his generation, or before, or after).

‡When a chawan is placed next to the bon-chaire, the distance between the chawan and the chaire is also 2-sun, which is the same as when a tray is not present.

Unless these things are understood, it will be impossible to understand Rikyū’s usages -- or the way his arrangements conform to the teachings of kane-wari.

¹⁹Temmoku [天目].

While not described further, this was probably Rikyū's Seto-temmoku [瀬戸天目] shown below.

Since nothing is said (and, indeed, the fact that this was an impromptu chakai argues against it), the temmoku was probably displayed on the utensil mat (next to the bon-chaire) without its dai, with the chakin, chasen, and chashaku arranged in it as if it were an ordinary chawan.

Possibly the temmoku was also used at the beginning of the chakai, to serve usucha (since Rikyū disliked using any more utensils than absolutely necessary).

²⁰Mizusashi Bizen hatsu no [水指 備前 初ノ].

This means that the mizusashi was the same one that had been used when serving usucha at the beginning of the chakai. This, too, suggests that the chawan may also have been the same.

As for the futaoki and koboshi, these would have been a take-wa [竹輪] and a mentsū [面桶] -- the mentsū probably being a new one, rather than the one used during the service of usucha earlier.

0 notes

Quote

Favorite tweets: 名古屋向かってます!おこしやす!7/28(土)名古屋 鶴舞KDハポン猫も杓子もvol.3〜はいからさん ミニアルバム 「LONG TIME COMING!!」レコ発名古屋〜w/フクラ本舗/ジャッケンボーノ/リバーヴス松石ゲル(DJ)open 18:30 start 19:00前売2000円/当日2500円 (+1D)※予約特典あり pic.twitter.com/MICOMAEpEj— はいからさん (@haikarasan_gogo) July 28, 2018

http://twitter.com/haikarasan_gogo

0 notes

Quote

Favorite tweets: KDハポンの7月マンスリーのピックアップに載せていただいてる!!!しかも嬉しすぎるコメントに号泣です(꒦ິ⌑꒦ີ )(꒦ິ⌑꒦ີ )精一杯のチカラを出します!是非、目撃して欲しい!7月28日(土)KDハポンはいからさんフクラ本舗リバーヴスジャッケンボーノDJ 松石ゲルご予約お待ちしてます pic.twitter.com/t3mVoX3gUJ— オタ (@otaota_otan) July 4, 2018

http://twitter.com/otaota_otan

0 notes

Quote

Favorite tweets: 告知です!7月28日(土)KDハポン「はいからさん」ライブ会場限定ミニアルバム【LONG TIME COMING!!】レコ発名古屋ピースフルで力強いロックンロールを一緒に歌って踊りましょうフクラ本舗・ジャッケンボーノ・リバーヴス・DJは松石ゲル!という贅沢な名古屋勢でのお祝いLIVEは見逃せませんよ! pic.twitter.com/PJerp70xGY— オタ (@otaota_otan) July 2, 2018

http://twitter.com/otaota_otan

0 notes