Text

qiao wanmian and di feisheng's first appearances in the present-day narrative are mirrors of each other, orbiting the presence of li xiangyi and li lianhua. episode 5 introduces them both in the same way, stepping back into li lianhua's life while he watches from out of sight. di feisheng emerges from seclusion, qiao wanmian meets xiao zijin in yucheng. and what other information this episode gives us about these characters is the inverse of what we would've expected. where we assumed qiao wanmian might be the ex-lover, still mourning after ten years of missing li xiangyi, the first thing we (and li lianhua) see is that she's happy with someone else. it comes to be more nuanced than that, but the first impression we get is that qiao wanmian has moved on. di feisheng's first moment he gets by himself, meanwhile, is him drinking his grief over li xiangyi's absence away. he has jinyuanmeng bowing to his feet and and a tremendous amount of power in the jianghu he could use against anyone, yet here is, seemingly, above many other things, lonely.

the next arc serves to reinforce this idea, that where qiao wanmian by normal genre conventions should be the one who couldn't get over li xiangyi, it's di feisheng who continues to cling onto his history with him instead. during the liansanjiao's trip to baichuanyuan and pudu temple, we see qiao wanmian trying to work through her lingering emotions about li xiangyi over and over, and eventually (thanks to li lianhua's intervention) achieves some kind of tenuous closure on that part of her past. all of we see of di feisheng, on the other hand, is him becoming increasingly obsessed with what he views as unresolved events, until he finally chokes li lianhua against a wall to interrogate him about it. mysterious lotus casebook swapped what might be more typical framing of these characters. qiao wanmian is not a sad figure waiting for her sweetheart to return, but someone who realizes she was more attached to what he represents than to him, and in finding him as a person manages to become friends in this new life of the present. di feisheng isn't someone who moves on from an existence measured against li xiangyi and finds a new way to define himself, but rather a person who wound up isolated and frozen in time for ten years after losing him, and still struggles to leave their relationship behind or allow it to evolve.

tl;dr the real jilted lover of li xiangyi by the choices of the story is di feisheng, not qiao wanmian

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching Mysterious Lotus Casebook common thoughts:

“Gay!”

“Ugh another mystery? Should I fast forward?”

“Omg that mystery was awesome I’m glad I didn’t fast forward!”

“Someone on tumblr… please gif every facial expression Cheng Yi is rolling out for this show…”

“Someone on tumblr made a gif set of my scene!”

“Gay!”

“Where is the dog?”

“I want a dumbass best friend to travel the world with who I can tease and play with…”

“Dude stop giving your qi or chi or whatever away! You’re gonna die!”

“Omg his eyelashes! Hmmm villain hottie.”

“This crazy bitch rules. Her agenda is dick and mayhem. She’s getting one at least.”

“Everyone has big houses in this show. And lotus ponds. And teenie tiny tea cups.”

“Poly gay!”

“Dude stop using your martial arts you’re gonna die!”

“The women in this show are great. But my Cheng Yi is my prettiest princess…”

“Villain guy (I mean is he even?) is soooooo… I mean… his hair! His grumpy face. Look at how he just stands there all menacing and hot…”

“The dog!”

“How does he keep his white robes clean? What was the laundry process back then anyway?”

“Gay!!!!”

“This show is made for tumblr peeps. Like… how can there be so much? Soooo much?!”

“Cheng Yi! Don’t cry… nooooo (let me drink your tears you beautiful creature it’s preposterous how pretty you are when you cry)”

“I think we are nearing the point where not telling your adorable dumbass your identity is borderline cruel… come on…”

“GAY.”

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

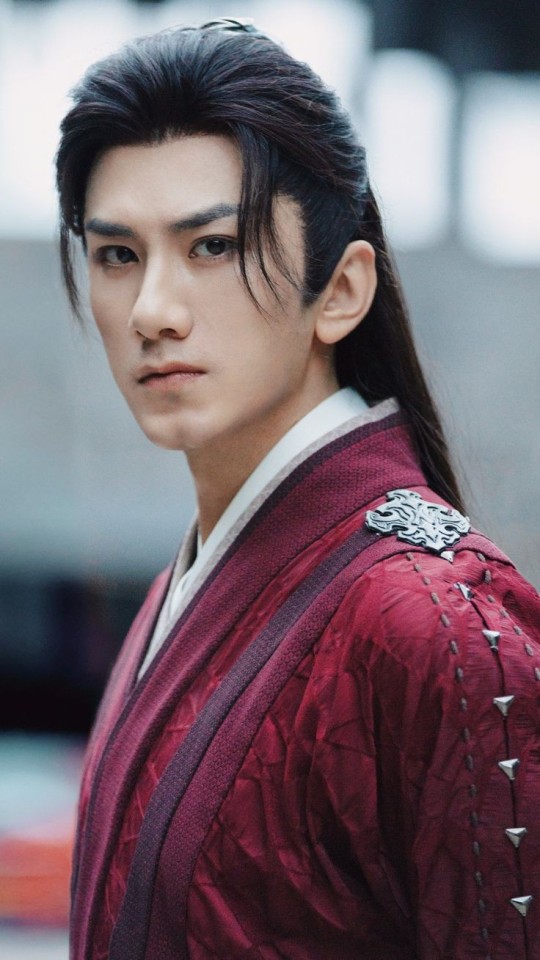

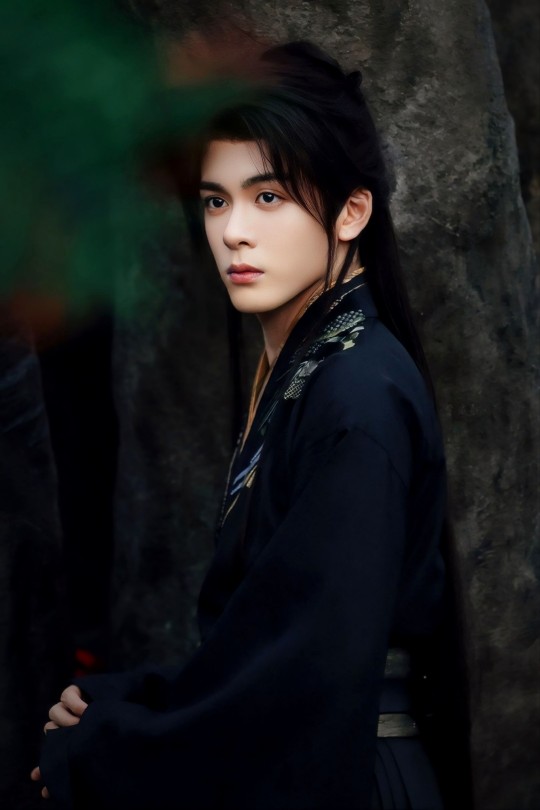

Why i didn't notice that these motherfukers

Are the split image of these other motherfukers

Pls cast Cheng Yi and Xiao Shunyao for tye live action I BEG YOU

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hmm maybe I should ask (sorry I might tag a few things) but is it like a thing in southern Asia to call out someone's name that much ? I will admit apart from learning korean and medias like anime and dramas, I never got to visit or know many people from these countries to have a better understanding of it (tbf I learned english like super late so I couldn't communicate with my japanese aunt for super long :( plus she lives in another country so we don't see each other that much).

For reference I'm from France. There are a few things I've noticed from foreign medias that I never know if it's a real cultural thing or jsut something you see on the television. For exemple US medias show people using a lot of nicknames for people, either a shorter version of someone's name or a funny title. I've barely ever done it or heard people do it here, more often than not it's nicknames that sound like the ones you could hear in us-american medias which I'm guessing is where the influence comes from).

That's why I wonder if it's a thing to use someone's name that much/often in south Asia, cause here it's really not that common. It's either to grab someone's attention once or when talking about someone so we know who the subject is. As a matter of fact I barely ever hear my name irl that it's always a surprise to hear someone say it to me when we've already engaged conversation (and still people usually grab someone's attention either by poking them or looking into their eyes).

#cdrama#jdrama#kdrama#i am also curious#i hear my name and its a shock to the system#or i think I'm in trouble

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Li Lianhua isn't so much haunted or loved by the narrative as he IS the narrative. He's the young hero he's the cyptic mentor he's the disappearing lover. The story revolves around his life until it doesn't. At the end we're left with the same question that Fang Duobing and Di Feisheng have to ask: what happens to the rest of the story when the narrative is gone?

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished tgcf season 2 and something clicked for me. This show has had my brain in an absolute chokehold since I started watching a week ago and I've been thinking, why? Well,

Hua Cheng and Xie Lian are Gomez & Morticia Addams coded.

And I can't not be obsessed with that. Hear me out.

Two dangerous individuals, both very weird in their own special ways, finding home in each other when they're feared and shunned by most.

Loving each other openly and loudly, even when people look at them sideways for it, because they're each other's everything and hiding that feels Wrong on a fundamental level.

It's respecting and encouraging each other's oddities, no matter how unusual they might be.

It's protecting each other fiercely but never out of possessiveness, because their significant other is strong, powerful, capable and they would never demean them by overlooking that.

It's the obsessive devotion, the insane lengths they'd go for their beloved, but never overstepping boundaries and making them uncomfortable.

It's Hua Cheng offering his ashes, the only way someone could possibly kill him, to Xie Lian on a silver platter, expecting nothing in return, just because it's his to keep.

It's Xie Lian wearing it over his heart everywhere, because that's where it belongs.

#heaven official's blessing#tian guan ci fu#xie lian#hua cheng#you aren't wrong op#they do have the Addams Vibe

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

now is not the time of night for me to be thinking about this in-depth, but there are two things i try not to forget in situating li xiangyi and di feisheng's places in the narrative. one, is that the jianghu in wuxia origin inherently exists as a space outside of and oppositional to (often ineffective and corrupt) figures of government, a concept key to wuxia as a genre and its historical context. two, is that the 侠 warrior holds first to their own honour before the dictation of any other authority or person. if you consider these conventions, and then look at how li xiangyi formed baichuanyuan as an ideal arbiter of justice for the jianghu (whose ultimate representation was himself), well. it's not surprising that di feisheng— lone swordsman answering to no one aside from his own code— gained so many allies and was uplifted as the perfect rival to counter li xiangyi, is it?

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It can be hard to avoid getting injured during the process of filming. As a result, do you have any fear or resistance toward these kinds of scenes [that can cause that]?"

Cheng Yi: "This is something that can't be avoided (...) it's just about learning to protect yourself, isn't it? It can't be helped. If you're shooting a fight scene but can't deal with getting a little hurt, do you have it in you to shoot fight scenes, then? This is fairly normal.

What we do can't even really be called martial arts. The stuntman/martial artist laoshis have it harder. For example, if we're doing wire work— I'm speaking honestly here— everyone's stuntmen are put into the most danger. Only once the hazardous moves are complete do the actors take over. [Stuntmen] are the number one people at risk. This is something I really want to emphasize.

For example, if there's a difficult stunt, [the stuntman] will try it first, then ask you afterward if you can do it, and they're always very respectful too. 'If you want a 360 degree spin, is your core strong enough to turn like that? If it is, you have to make the spin look good. Can your core achieve that? Are you able to execute your movements properly?' They'll ask you things like this. It's up to you, but if you can't do it, [the stuntmen] also won't force you." (x)

None of the guzhuang fight scenes you enjoy are possible without the stunt teams working just out of view alongside the actors to make them happen.

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey not to be deeply weird about it but just to check, has everyone else already seen this interview with xiao shunyao in which he (correctly) argues that actually di feisheng is a deeply loyal and affectionate character, and also that li xiangyi gives di feisheng a reason to live?

youtube

i'm so fucking normal about it

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is targeted tumblr content

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Love how tumblr has its own folk stories. Yeah the God of Arepo we’ve all heard the story and we all still cry about it. Yeah that one about the woman locked up for centuries finally getting free. That one about the witch who would marry anyone who could get her house key from her cat and it’s revealed she IS the cat after the narrator befriends the cat.

324K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewatching 《莲花楼》 (Mysterious Lotus Casebook) and they really gave us Li Lianhua rescuing stealing Jiao Liqiao's groom from the dungeon, spending the whole night with him in the wedding chamber exchanging internal energies, then drinking matrimonial wine while admiring the moon and toasting each other on the 10th anniversary of the night that they stabbed each other with their swords, and then they both waltz out in the morning and start to 打情骂俏 (bicker-flirt)? Right in front of Jiao Liqiao's salad? Smh guys.

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't care from what show this is. He is gorgeous and I will simply think of this as an older version of Fang Duobing

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

🪷 The Lotus Flower in Mysterious Lotus Casebook 🪷

i. Growing Deep Roots

As noted by difeisheng, Li Xiangyi is an image more than he is a person. He’s the “symbol” and “beating heart” of the Sigu sect; “he embodies everything [the sect] stands for” and “has become one with every person he represents” in his role as a leader. As such, one might say he doesn’t exist as an individual who’s allowed the luxury of flawed, fluid humanity. Rather, he’s fixed into an object: a shield protecting those under his care, a mirror reflecting those he’s taken upon himself to be the champion for.

While a heavy burden to carry, this identity as image is also shown to be brittle, hollow, like a hazy mirage which is more dazzling appearance than substance. Even Fang Duobing introduces Li Xiangyi to Li Lianhua by showing him a painting of his shifu — ink on a page, a person turned into a hero to be worshipped and idolated.

Li Lianhua, over the ten years that pass after the Great Battle of the East Sea, works to plant and cultivate a new identity in the same way one might grow flowers. Li Lianhua forms deep roots and grows out of the mythical hero’s shell he’d been carrying as Li Xiangyi, thus developing an identity which is solid and grounding in contrast — an identity which involves “walk[ing] within a crowd instead of [soaring] above it.”

This shift from image to person is itself rooted in the lotus mantra (written by Buddhist Layman Pang during the Tang Dynasty) which Li Xiangyi first encounters after monk Wu Liao rescues him:

一念心清净

莲花处处开

The heart attains peace with a single thought;

Lotus flowers bloom all around.

Although the exact timeline is left to interpretation, it’s implied that the lotus mantra operates as a catalyst of change for Li Xiangyi and that he changes his name to Li Lianhua after reading it. Now what is it about it that speaks to Li Xiangyi so deeply in that moment? As noted in 《 人間福報 》, the lotus mantra teaches us that a pure heart will result in an open and enlightened mind. One subtle, profound thought rife with compassion is enough for a person to glimpse Buddha in a flower, a leaf, a grain of sand or a speck of dust. In short, “if you can find peace within yourself, then you will find peace everywhere.” Perhaps Li Xiangyi, at his lowest point, finds solace in the prospect of stripping his life down to its very core and searching for purity, wisdom and peace within his troubled heart.

By renaming himself 莲花/liánhuā lotus flower, Li Lianhua takes his destiny into his own hands; he empowers himself into reshaping his identity and laying down the foundations for the person he wants to become. Similarly to The Yin-Yang Master: Dream of Eternity which tells us that “names are the shortest spells in the world,” Li Lianhua’s new name functions as a spell which speaks a new him into existence. It’s a deliberate choice, a conscious attempt at breaking free from the suffocating shell Li Xiangyi was trapped in and become a person of his own choosing.

The act of (re)naming notably also extends to Li Lianhua’s abode which he dubs 莲花楼 “Lotus Tower.” In addition to this significant choice of name, it’s interesting to note that Li Lianhua starts growing vegetables inside Lotus Tower when he’s left with nothing after his demise at the East Sea and is facing starvation. As such, his home is quite literally a site not only of self-sustenance and survival, but also of growth — a growth which requires hard work, patience and faith and nearly brings Li Lianhua to tears when his hopes are finally rewarded and the seeds he planted begin sprouting. The act of physically planting vegetables and learning to cook those vegetables speaks of a refreshing and grounding simplicity — of something disarmingly vulnerable and human after playing the role of a god-like figure. Li Lianhua has sweat on his brow and hope in his heart; he plants seeds, watches them grow and keeps himself alive by his own hands.

It seems it’s not only Li Lianhus’a home, but also his very person, which steadily grow into a lotus flower. Li Lianhua wears a variety of hairpins directly linked to the lotus, and the colour coding of his garments moves from the red he used to wear as Li Xiangyi to a lighter palette filled with greens and blues — colours which are more obviously linked to nature.

ii. Life Borrowed and Given Away

The lotus, both traditionally and within the drama itself, is closely connected to the theme of rebirth. On a literal level, the exotic lotus flowers of Cai Lian Manor grow directly from the corpses of the victims drowned in the pond, thus embodying life born from death. thawrecka writes in their story that Li Lianhua is “nothing but a lotus nurtured by a walking corpse, a body that doesn’t realise it should already be dead.” On a figurative level, the lotus grows in muddy water but blooms unsullied every morning, thus symbolising rising from a dark place and growing into something beautiful and colourful despite all the odds. The different stages of the lotus’ blooming can be taken to represent the beginning, middle and end of a spiritual path in Buddhism — a parallel to the theme of 趟/tāng taking a journey which underscores the drama in various ways.

Li Lianhua’s journey, more specifically, is that of a lotus being reborn. The soundtrack piece 《 一壶莲花醉 》 “A Pot of Lotus Wine” emphasises this connection in the following lines:

问一句莲花的悲喜

断一柄弃剑入青泥

I ask about the joys and sorrows of the lotus;

A broken, abandoned sword is thrown into the mud.

Not only does Li Lianhua keep stressing at different points of the drama that Li Xiangyi is dead and all that is left behind is Li Lianhua; he even breaks his own sword Shaoshi at the end of the story, thereby physically reenacting a process of destruction—death—and rebirth. As Li Lianhua writes in his farewell letter:

剑断人亡

My sword is broken, and I will be gone.

The significance of Li Lianhua’s action is further intensified here by the fact that the sword in the song is said to be thrown into 泥/ní mud, the site from which a lotus flower grows.

Considering that Shaoshi operates as a device embodying Li Lianhua’s character development throughout the drama, the fact that Li Lianhua decides to break it in the last episode should be taken as a key moment in which he chooses how his own narrative is going to end. Li Lianhua decides to kill for good the glorious image of Li Xiangyi which has become sullied with pain and regret in his heart, so that a simple, fragile peace can begin growing in its place like a lotus flower amidst the mud.

However, the tragedy of Li Lianhua’s narrative is that the rebirth he works to achieve for all these years is not his own to enjoy and never was intended to be. After the Great Battle of the East Sea, as Li Lianhua is reborn from Li Xiangyi and starts planting seeds all around him, he has already accepted that he’s nothing but a ghost, “wandering in the jianghu to close his loose ends and finally [...] vanish without a trace, not even a body left behind.” As mx-myth remarks, even the shift in his garment colours to an overwhelming amount of white as the story progresses makes it clear that he’s resigned to go and has “already started dressing for his own funeral.”

The lotus flower symbolism permeating the narrative accentuates this bone-deep, unshakable resignation. While imprisoned by Jiao Liqiao, Li Lianhua is full of an aching, bittersweet fatalism when he recites a section of Guan Hanqing’s《 窦娥冤 》“The Injustice to Dou E”:

花有重开日

人无再少年

不须长富贵

安乐是神仙

Flowers will blossom again,

But a man can never be young again.

Seek not eternal wealth;

You only need to be content.

Independently from the original meaning of the lines written by Guan Hanqing, the words seem to take on a sad, wistful quality when spoken with a bitter smile by Li Lianhua. In this scene, while the speaker reflects that rebirth occurs outside of themselves in flowers, they acknowledge that their own reality is one inevitably bound to end in old age and decay. Instead of looking forward to a bright future, the speaker doesn’t express any dreams nor ambitions and is only grateful that they’re alive this minute, this second, without any future prospects awaiting them. Perhaps a similar sentiment is reflected in the following lines from 《 一壶莲花醉 》 “A Pot of Lotus Wine”:

了了心事只

不负众生 而已

After settling my worries,

I just want to live up to all sentient beings.

Li Lianhua’s connection to the lotus flower, in fact, was always meant to be one of non-attachment. While Buddhism believes desire to be the root of all suffering, the lotus symbolises non-attachment due to being “rooted in mud (attachment and desire)” while “its flowers blossom on long stalks unsullied by the mud below.” This explains in part why the lotus is considered pure and noble. For Li Lianhua, this non-attachment takes on sorrowful connotations: it means that he stubbornly refuses to reap the seeds he sows and focuses his purest heart and will into ensuring those around him get to reap them instead. Non-attachment means allowing himself enough (a roof over his head, food on his plate) to survive, but rarely letting himself indulge in the precious luxuries of reciprocated love and care — of carefree joy and thirst for adventure.

The ten years he lives after his first death at the East Sea are, for him, only borrowed time he didn’t deserve — borrowed time not dedicated to himself, but rather dedicated to others.

In many ways, Li Lianhua’s path effectively goes full-circle by the end of the narrative. When he and Di Feisheng reminisce about the moon they remember from ten years ago, they conclude that today’s moon isn’t any brighter than the one alive in their memory: rather, it remains constant, unchanged, as though the past ten years never existed as anything other than a short pause in the story, a coma, long enough for wrongs to be righted but not for an already-dead person’s fate to be changed.

It’s interesting and particularly significant that the Styx flower (忘川花, from 忘川 “River of Forgetting” in the original Mandarin) is said throughout the drama to be the only thing capable of saving Li Lianhua’s life. In traditional Chinese culture, the Styx or River of Forgetting is part of the process of reincarnation; only by crossing it (and forgetting everything they’ve ever experienced and everyone they’ve ever loved) can a person finally reincarnate. For Li Lianhua, salvation through rebirth comes at a high cost — a price he’s evidently been ready to pay since the beginning, even if it means turning him into a ghost who must vanish from the story in order for those around him to grow and thrive further.

When Li Lianhua breaks his own sword to allow for rebirth, it’s not himself he’s saving. His sole purpose throughout his journey as Li Lianhua is to use whatever meagre strength he has left, whatever passion and drive are still alive in him, to save the world in any small ways that he can. He becomes a doctor who heals people; he looks for answers and solves mysteries to atone for the sins he thinks he has committed and rectify the mistakes he thinks he has made, so that those he has hurt can finally find peace and comfort.

The most powerful legacy Li Lianhua intends to leave behind by the end of the story has nothing to do with himself and everything to do with the people around him who he never truly admits he loves — the messy, imperfect world that’s caused him so much pain but that he nevertheless insists on saving with everything he has.

Most strikingly, Li Lianhua chooses—whether consciously or not—to leave the life and future he’s renounced for himself to his companions Fang Duobing and Di Feisheng. The only traces he purposefully leaves behind live in them: in the Yangzhouman coursing through Fang Duobing’s body; the home, dog and recipe book he passes onto him; the worthy opponent he leaves for Di Feisheng to fight in his stead after he’s gone…

Fang Duobing, by the end of the story, has grown into more than a disciple and a friend to Li Xiangyi/Li Lianhua: he himself has become the lotus flower bringing renewed life after Li Lianhua has left the narrative, thereby taking Li Lianhua’s legacy into a hopeful, vibrant future. As mx-myth mentions in their colour analysis, Fang Duobing notably wears bright pastel tones including a large amount of green/blue — a colour coding which emphasises Fang Duobing’s connection to spring and, by extension, new life and beginnings. “Life will always go on if there’s spring”; and so Fang Duobing’s youth, vitality and optimism can grow in the empty space left behind by Li Lianhua after he fades into the autumn of his life.

While Li Lianhua’s predominantly light colour palette might appear to align him with other characters in the drama who have left the past behind and are looking towards the future, Li Lianhua made peace long ago with the knowledge that he’s destined not to belong in that future. Just as the Lotus Sutra teaches us that “the inner determination of an individual has great transformative power” and “gives ultimate expression to the infinite potential and dignity inherent in each human life,” Li Lianhua focuses all his transformative efforts on creating a future which, despite having no place for him, will be fertile ground for the entire martial arts world to grow deep, healthy roots. In Li Lianhua’s own words:

幼芽生枝 新木长成

武林也一样

这未来如何

谁又能说得清楚呢

The young sprouts and the new trees grow.

The martial arts world is the same.

What does the future hold?

Who can say clearly?

Should we say, then, that Li Lianhua’s story is one of sacrifice, self-renunciation and resignation — of drifting inevitably towards death as a flower carried by a stream? As he disappears on a boat and is asked where he’s going, Li Lianhua gives a response which echoes his first death at the East Sea in a way that feels entirely deliberate:

小舟从此逝,

江海寄余生

From now on I would vanish with my little boat;

For the rest of my life on the sea I would float.

How are we to understand a person being reborn simply so they can pass on that new life to others, and being convinced that their only true value lies in their death?

Perhaps, in spite of it all, we can find some small comfort in the knowledge that, no matter how sorrowful Li Lianhua’s fate, it’s at least one that he chooses — one that he has full control over, even poisoned and robbed of his life force as he is. As the lyrics of 《 一壶莲花醉 》 “A Pot of Lotus Wine” underline, “it’s just a matter of picking an ending that you like.” Perhaps that’s all that truly matters.

wuxia-vanlifer makes an excellent point when asking: “What would be more tragic? That he never believed he was loved? Or that he did, but vanished anyway?” While I don’t have an answer to offer, there’s one thing I can say. Li Xiangyi, Li Lianhua — they live and die by love. They can’t conceive of themselves as anything other than a sacrificial tool because, for all that they pretend to be aloof and untethered, they actually love others—and the world—in a bone-deep, profound way they’ve never loved themselves. That love is not only the true driving force behind Li Lianhua’s character and the fate he chooses: it’s the beating heart of the entire drama.

“In this life, I have loved and I have been loved. That is enough.”

Shoutout to the following authors and bloggers whose brilliant words and ideas inspire me, as well as this gorgeous video 💖

ao3: @extraordinarilyextreme @thawrecka

tumblr: @difeisheng @extraordinarilyextreme @mx-myth @wuxia-vanlifer @xinyuehui

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cheng Yi x weapons

Bo

Sword

Brush

Umbrella

BONUS: Xuan Ye, can you see??

Spear

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

They say you die three times, first when the body dies, second, when your body enters the grave, and third, when your name is spoken for the last time. You were a normal person in life, but hundreds of years later, you still haven’t had your “third” death. You decide to find out why.

60K notes

·

View notes