Text

I like the pictures for these two posts, but neither HORRIFIED nor WINGSPAN will appear on this two-part list. I would, however, fully endorse Horrified as an excellent gateway--and superior (!!) alternative to Pandemic.

NOTE: Part 1 can be found here--and apologies this took a lifetime to complete.

Harbour (2015)

WTF is this OOP?; Complexity 2.09/5; BGG;

Mechanisms: Worker Placement, Set Collection, Variable Player Powers

I already said that, for many, worker placement is the evergreen mechanic, so I figured I'd turn two entries on this list over to it. Where Coal Baron was a slight subversion of the genre, Harbour is not. This is the prototypical game in that you place a worker, do an action, and block a space. In Harbour, believe it or not, you're working in a... harbor. You, as a small gremlin-looking fellow visiting buildings to take actions, selling goods (cows, stone, wood, fish) in order to parlay those sales into purchasing new buildings in the harbor, thereby giving you new action spaces to do new cool stuff.

Harbour is a great entry into the inherently meaner side of worker placement because you only have one worker, so it's not quite as overwhelming as games where you start with a heap o' workers, but you can most certainly block action spaces. Not only that, but the market of the game is a simple system of fluctuating prices that are affected each time a player sells something. For a small box game, Harbour includes the idea of supply/demand, so things that aren't being sold to market are worth more, while things being sold constantly tank in value. Buildings have varied and interesting special abilities, and there are a lot of buildings that will come out into play during any given game, as well as a huge host of special abilities that players will start with, making the game play slightly asymmetrical.

With its worker placement, fluctuating market prices, buying/selling, and special abilities, Harbour is an excellent small box introduction to a plethora of Euro mechanics, and the fact that all of these interesting aspects are encapsulated in such a cleap, small box is remarkable. I will say, however, that of the six games on this list, Harbour is the game I'm least likely to play because I've grown past it as a gamer. I've seen this jokingly referred to as Tiny Epic Le Havre, which feels very on the nose. That being said, it does a remarkable job of introducing a handful of popular Euro mechanics, so if this game piques your interests, it has plenty of bigger, meatier siblings out there.

For a game that I haven't touched in a long while, Harbour is probably one of the best single small box game introductions to Euro mechanics I've played.

For those meat and potato worker placement fans (light to heavy): Lords of Waterdeep, Viticulture: Essential Edition, The Gallerist

If you enjoyed the market-based buying/selling/producing bits: Clans of Caledonia

Valley of the Kings (2014)

Try it and get the deluxe edition;

Complexity 2.19/5; BGG;

Mechanisms: Card Drafting, Deck Building, Hand Management, Set Collection

It was inevitable that I include deck building on here. For me, deck building is like the junk food of mechanics. When I first encountered deck building, it was all I wanted to do. There is something driving and compulsive about it. You have the feeling that all you have are options, with infinite combos laid out at your feet. I wanted to try every theme and variation possible. For a little bit, the hobby seemed to be exploding with deck builders of all stripes, with variations popping up everywhere.

Things have cooled now, and it seems deck building has found a more comfortable passenger seat behind (or partnered alongside) other mechanics in mid+ weight Euros, and I think that pairing it with additional mechanics in bigger games actually brings the mechanic to life. Deck building is the idea that all players will start with a small deck of very basic and underpowered cards--generally consisting of cards of different currencies, like attack and some kind of purchasing currency--that you'll use to either buy or defeat other cards, adding them to your deck and thereby increasing the strength of purchasing or fighting, as well as the abilities available to you.

It's a simple idea, but boy is it like Pringles when you first play it. We have a lot of deck builders, and a bunch more that we've since parted ways with. The problem is that many feel a bit themeless and similar, begging the question: If you've played one deck builder, have you played them all?

I would argue no. That being said, if you've played one, you've played... most. Dominion, Marvel: Legendary, Star Realms, Aeon's End, Hero Realms, Nightfall, Paperback, Eminent Domain, Core Worlds, Ascension, Marvel Dicemasters (not deck but dice pool builder), Shadowrun: Crossfire/Dragonfire, and Thunderstone all feel pretty sorta similar. Granted, they each bring a little teeny bit of something different, but if you didn't like one of these, you probably won't like most/any of them.

Valley of the kings subverts a lot of the classic expectations of a deck builder. First of all, the market is spatially interesting. Not just a flat row of cards that randomly come out, these cards form a pyramid, and you're only able to purchase cards on the bottom row. For the first time, maybe it would behoove you not to buy a decent card on the bottom, because once you do, the card above it will "fall" down and become available to the next player. But maybe you should do it anyway, because there are plenty of cards that let you slightly manipulate the arrangement of the pyramid, anyway. More interesting than the pyramid, however, is the end game scoring. Most cards are not worth flat rate points, but rather points based on how many you were able to squirrel away. And by "squirrel away," I mean you'll literally need to start removing them from your deck, one at a time, and adding them to your "tomb" (errr, thematically-named scoring pile) in order to score. Great cards in your deck or hand at the end of the game are worth nothin'. Timing is everything. If you realize that the other player is burying way more cards than you and accelerating the speed of the game, you really need to get on your horse and get those cards into your tomb, otherwise you're going to be out a lot of points. But by removing the cards from your deck, you will become less powerful. So... when do you do it?

Tough choices are the queen in great games, and for a tiny box that is not expensive, this game packs a lot of difficult, interesting decisions.

For excellent straight-up deck builders to get you shufflin' everyday: Legendary Encounters: Alien and Arctic Scavengers

If you want a little bit of deck building in your slightly heavier Euros: Great Western Trail (most Alexander Pfister, really), Orléans (not deck, but pool building), Time of Crisis, Newton, Concordia, Founders of Gloomhaven, Undaunted: Normandy/North Africa

Welcome To...

$20ish depending on the day; Complexity 1.82/5; BGG;

Mechanisms: Roll & Write, Bingo, Pattern Building

Roll and write games are like the little subgenre that could. So small, so simple, and so popular. For the past few years, roll and writes have fought for a place at the table, and at this point, I think they've done it. Heck, they even have entries that are skewing heavier in weight (Welcome to Dino World). That being said, lightness permeates most roll and writes, and that's not a bad thing. Light doesn't necessarily translate to SLIGHT.

Roll and writes are games where players begin with the same, or very similar, starting sheets of paper, at which point some randomizing thingy like dice (see: roll and write) or cards are used to present variable restrictions or requirements that players must work on accomplishing. As you draw or write or fill-in boxes on your little paper, your sheet will begin to look quite different from everyone else's. At the end of the game, you'll calculate scores and the highest wins. Yay.

Roll and writes have a great tactile nature, which for some reason is easier to teach than more abstract ideas you'd find in an equally light game. Being able to draw routes or write down numbers or shade specific areas feels oddly familiar, which makes roll and write games very family friendly. They also generally have a small footprint, small box, and low price tag, without sacrificing replayability. We have a few roll and writes, and I can say that they all seem to have high replayability--if roll and writes are your thing. I've read plenty from people who don't seem to like roll and writes, but the myriad options that clever designers have managed to get into these tiny games are remarkable. In Railroad Ink, you will roll dice that show sections of track, and slowly you will draw tracks on tiny dry erase boards, working to score specific features before your turns run out. In the aforementioned Welcome to Dino World, you'll be building dinosaur pens, powering electric fences, building features for your park, and trying to prevent the dinos from busting out and devouring people your score.

But what about Welcome To...? This game is a small, card-driven roll and write where you flip three double-sided cards so you'll be showing a trio of pairs baring number on one side and a feature on the back of another card, forcing you to choose one and add it to your map of a minute subdivision. Your working to meet end game objectives for points, as well as build specific features, like parks, to make sure you have the best neighborhood around.

Welcome To... brings the simple gameplay and high replayability along with a charming theme and low price tag. I could always play Welcome To..., and it does everything without falling into a roll and write pitfall of being too vaguely mathy or themeless. We've played with family who have not moved beyond Scrabble, and they loved it. And we've played it more than our fair share at the end of the night with a cool adult beverage in hand.

Roll more and write more, too: The Cartographers, Railroad Ink, Silver & Gold, On Tour, Imperial Settlers: Roll and Write

I want something a smidge heavier than that Welcome To... game: Welcome to New Las Vegas!

If you just want a taste of this because it sounds a little juvenile: Get the app for Ganz Schon Clever, which technically may be my most played game ever considering how you just want to get a higher score. You can do better. No, you can do better! Play again! No, now!

***

SORRY this took so long to complete. The problem with taking a long time to write about some games is that now a handful are hard to get. Go figure. Check your local store, older games have plenty of life.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The State of the Board

I hope this message finds you well, especially in such a tumultuous time. Kathleen and I have been very quiet of late, both in regard to Player One | Player Two podcastin’, as well as working on the blog or even my posting on Instagram. This isn’t just happenstance.

In truth, we have chosen to take a step back from things to try to reassess our place, to say nothing of going into safe/shelter mode. This isn’t just due to the pandemic, mind you, but everything happening in this country (US) right now.

The pandemic, racial strife, and dangerous political developments have made us try to refocus ourselves as people. We’re white, and I think it’s fair to say we’ve always been aware of our privileges. An awareness, however, isn’t really enough. We’re taking some time to educate ourselves further on how to be allies and participate more in local government. At this point, “participating” translates to being present for Zoom meetings of our town council, but we can continue to grow.

We’ve also been playing games. Games are such an important part of our lives, and in difficult times (like a global health crisis, domestic unrest, and growing national uncertainty), it’s important for us to do what we can to be together and feel good. So yeah, that means we’re still playing games.

Unmatched, The Voyages of Marco Polo, Mystery Rummy: Jekyll & Hyde, Mechs vs. Minions, Welcome to DinoWorld, Cockroach Poker, The Oracle of Delphi, and more have hit our table. I’m looking forward to sharing more of our thoughts on these soon.

That being said, it may be a minute before we do. I read recently that Michelle Obama came forward saying she was suffering from low grade depression. It’s fair to say she is not alone. So much of our lives that we took for granted seem nigh impossible to take for granted now, especially when simply going to the grocery store could put yourself or loved ones at risk. People are losing their jobs, their homes, and their lives. Things are bad right now. This is something that will be taught in history classes someday.

I certainly don’t want this simple post to seem too down, but I want to tell you, dear reader, why we’ve gone silent. We’re still here. We’re still shuffling. We’re still sitting down across the table from each other and enjoying the time. But it’s important now that we all take care of ourselves, so we’re trying to do just that.

Stay safe out there. Do what you can to make yourselves happy until things return to something like normal. Play good games with people you love. It’s important.

Eric

Player One

1 note

·

View note

Text

Episode 21: Don’t Go Breaking My Heart

Exit: The Catacombs of Horror by Inka Brand, Markus Brand, Ralph Querfurth

Episode 21: Don’t Go Breaking My Heart

0 notes

Text

Top 6 Gateway Games Not On Other Lists: Part 1

Recommendations for beginner board games, gateway board games, or next step board games (or any myriad variations) are spread across the wilderness of the internet like dandelions...

So here are some of our recommendations.

Oh, and they are all:

CHEAP

INTERESTING

and EASY TO LEARN

All right, so lots of these gateway lists are excellent, but they are very similar. One list will have significant crossover with another. And another. And another. The clear reasoning behind this is that there really are a handful of games that are just great to recommend to people new to the hobby.

These 10 are going to appear on a lot of lists:

- Pandemic (2008)

- Ticket to Ride (2004)

- Catan (1995)

- Sushi Go (2013)

- Carcassonne (2000)

- Codenames (2015)

- One Night Ultimate Werewolf (2014)

- Splendor (2014)

- 7 Wonders (2010)

- King of Tokyo (2011)

Each of these games has plenty of merit (I make this statement even though, for the sake of full disclosure, I freely admit we've never played 7 Wonders or Splendor, and it's been 20+ years since I last played Catan). The choice not to include any of these games here is because, frankly, I don't want this list to be completely redundant.

If you're anything like me, as a curious beginner to the hobby, you've made some permutation of this google search a whole lotta times. You've seen Pandemic and Ticket to Ride recommendations on a baker's dozen websites. If, for some reason, this is your first list like this, here are a few sites worth your traffic:

Paste, Dice Tower, IGN, Wire Cutter, this Medium list

It's really difficult to recommend games to people, not only because of the reasoning previously stated (that many recommendations are made so often they are simply rote), but it also presupposes that my opinions here have some kind of merit. With that in mind, I am writing this list because this is the list that I really needed about four or five years ago. I googled this topic incessantly, and more often than not I purchased games that were simply not a good fit for me and Kathleen. Games like Pixel Tactics or Summoner Wars are interesting and well-made games, but they don't particularly fit our play styles. Being as we flew into this hobby unaccompanied, we did plenty of wandering in the dark. If I've done my job here, each of these games will be different, presenting the players with a variety of mechanics spread across the hobby, each offering a different feel and scratching a different itch.

Okay, all that wordy garbagio out of the way, here are the criteria I kept in mind while making this list:

- Mechanics: Each of these games represents a different set of mechanics that should help point you in which direction you may further enjoy with bigger, heavier games.

- Price: These games are not expensive, and this is REALLY important to me. I hate when I see people recommend something like Pandemic: Legacy or Gloomhaven as a game for new hobbyists. These are great games, but if you're not all-in to this hobby, do not buy a $100+ game. Wait until you know what you like. There are plenty of satisfying, well-designed games that I do not want to ever play. This says more about me than about the game. Save your money while learning what you like.

- Complexity: These are all reasonably simple and straightforward games. Beyond that, they [almost] all act as gateway games into bigger games–you'll see one exception later. If you like a certain mechanic you experienced, you're a spitting distance away from a bigger, heavier, thinkier game.

- Footprint: This is an inherited concern thanks to having a conscientious wife and a big collection. Small box games that pack a punch are precious. Learn to love 'em, especially if you live in a small apartment.

Being as this is the Player One Player Two site, it should go without saying that we believe these all play very well with two players.

Enough of that, let's get moving. This post is long enough already.

Kingdomino (2016)

$14.49; Complexity 1.21/5; BGG

Mechanics: Drafting, Tile Placement

I'm putting Kingdomino first because this is the game most likely to appear on other lists (it won the Spiel des Jahres the year it was released, the German Game of the Year award).

Kingdomino is a lovely little tile laying game that incorporates drafting and a clever exponential scoring system. In Kingdomino, players will draft tiles from an available pool, tiles that have different land types on them--like fields, lakes, or caverns. As you draft tiles, you will play them into your kingdom matching like land types (just like dominos! see? it's clever!).

The larger a specific kind of land type, the more points you'll score. Similar to Carcassonne, there are bonus multipliers that you'll be looking for that will help you grow your score faster. But which tile you drafted will dictate the order in which you'll get to draft in the next round, presenting you with an excellent dilemma each round. Should you draft that great tile, knowing it will put you farther down the line next round, or will you draft conservatively, putting yourself in a better position moving forward? Unlike Carcassonne, there are no meeples to drop across your map, meaning this game will not press you on the touch choice of it/when to drop a meeple, but arguably you'll feel less regret when you choose poorly.

Kingdomino plays fast, has excellent artwork, and presents more options and choices than Carcassonne without robbing you of Carcassonne's easy/breezy feel. The box is small, the teach is fast, and it's cheap.

Polyomino games are hot right now. If you like this, check out (light to heavy): Patchwork, Barenpark, A Feast for Odin.

If the drafting element was cool, try 7 Wonders Duel for a unique, lighter spin on drafting, or Blood Rage for a much heavier experience.

Came Up Cards (2016)

Out of Stock today, check back!; Complexity 1.67/5; BGG

Mechanisms: Betting/Bluffing, Hand Management

Camel Up is a well-loved board game about camels racing in the desert that I've never played. Again, we are price-conscious 'round here, and when I purchased Came Up Cards, it was done understanding that this small box would give me a good experience of the wild racing/betting game that is Camel Up and save me about $25 in the process. This is not the only _____: The Card Game that will appear on this list either.

(Side note: I am dumbfounded that this is currently out of stock everywhere. Keep looking around, it will come back!)

When you think of games involving racing, the first assumption is that the game will center around you controlling one racer and, you guessed it, trying to cross the finish line first. Camel Up Cards is not that game, which is why it's a refreshing play. Rather than pushing your own racer towards the finish line, you'll be playing cards from your hands to move individual camels forward towards the finish line. Getting over the finish line will end the game, but it won't mean anything for winning. The point of the game is to bet on who the winning–or losing–camel will be. Certain cards will denote how you believe each camel will finish, and the earlier you take a card, the more money (points) it will give you when the game ends. But who's to say what cards your opponent is holding.

Camel Up Cards is wild. You can make early bets based on what you're holding, but your opponent can and will play cards that will really screw up what you're doing. Add in the crazy palm tree, the desert fox, and the ability to stack the camels, and it's impossible to guess too far ahead who will win, but that won't stop you from trying.

I don't normally like "zany" or "wacky" games, and this game veers dangerously close to being both. Ultimately, it's a really fun and wild experience, but not without strategy. It gets crazy, but doesn't ever go off the rails, which I appreciate. BGG has the best player count at 4, but with fewer players this game is much more strategic than out of crazy, which is what I like. The more players you add, the less control you'll have over what will happen in the race. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but you better know what you're getting into a 4+ player game.

If you like the wild, push your luck element (light to heavy): Port Royal, The Quacks of Quedlinburg

If you like the racing and betting elements: Downforce

Coal Baron: The Great Card Game (2016)

$22.69; Complexity 2.68/5; BGG

Mechanisms: Worker Placement, Set Collection, Hand Management

Worker placement is, for many, the evergreen mechanic. New worker placement games come out all the time, with some fitting perfectly into the most inside-the-box expectation of worker placement and others working to flip the whole genre on its head. The basic idea of worker placement is uber simple: take one of your workers, put them on an action space, and do that action. Each action will have a limited number of spaces, adding a bit of a wrinkle to your plans once people start to block you. I love the idea of worker placement, but this idea of blocking really irks me, which is why I tend to enjoy subversions to the genre more than more meat and potatoes staples of the genre.

Coal Baron: The Great Card Game (henceforth known simply as Coal Baron--not to be mistaken for Coal Baron: The Board Game) fits neatly into the "subverts the genre" column. This is a game about building trains, loading them with coal, and fulfilling contracts for points. In terms of the actual worker placement in the game, never will you be outright blocked from taking an action, which delights me.

However, there are some built-in wrinkles. For example, you don't have workers as you'd immediately expect (meeples or pawns), but rather a hand of numbered cards that represent your workers. You must play cards down to action spaces in numerical order to take the action. So the first person to take a locomotive card to begin building their train must play a #1 worker. The next player to do this action must play a #2 worker (or two #1s), and so on. In this way, a space is never filled by workers, but taking an action becomes increasingly costly.

In this way, Coal Baron feels like it moves beyond worker placement and into hand management/action selection territory. There will always be a question of not only what you are doing, but when you choose to do it. Should you rush to take a contract and only spend a #1 worker, or wait until a better contract may be revealed, but be forced to pay more for it?

If you like the subverted form of worker placement seen here, try (light to heavy): Architects of the West Kingdom or the brain-melter Nippon (which I reviewed here).

If you like the puzzly card/hand management/set collection: Concordia

* * *

By my count, these three games make up the first half of our top six. I’ll finish off the rest of the list and be back before you know it with the rest of the countdown.

Thanks for reading!

Player One

Eric

#board games#gateway games#board game reviews#board game review#camel up#kingdomino#coal baron card game#top ten#list

0 notes

Text

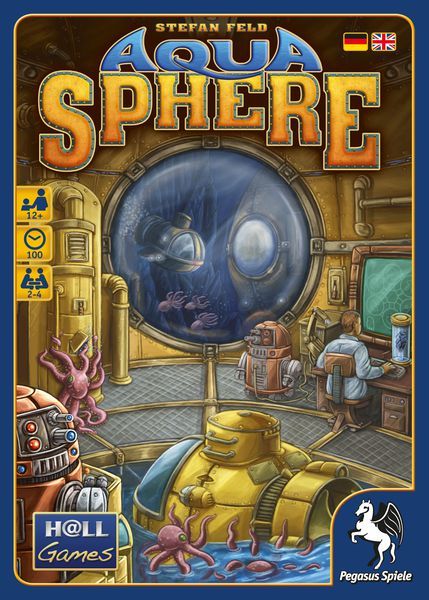

We Got Too Much (AquaSphere)

Point salad brain burnin’ metaphor mixin’ bad mother$%@#!

A first impression.

AquaSphere (2014)

Designed by Stefan Feld

Art by Dennis Lohausen

Published by Tasty Minstrel Games (in the US)

Asleep in the Desert (Some Background Information)

Stefan Feld, for being one of the preeminent Eurogame designers of the day, still often finds himself the target of attacks from tabletop gamers who prefer more than a skin-deep theme. He may have games about such varied and exciting things like jockeying for the attentions of a moon priestess, currying favor and fulfilling tasks handed down to you from Greek deities by a soothsayer, or leading your people through a brutally bad year in ancient China, but Stefan Feld’s games are generally held up as the pinnacle of The Dry Euro. A more generous opinion would probably be that Feld’s designs emphasize substance over style, but rare is this case made on his behalf.

In this house, at least, we certainly don’t mind how bone dry some of these games are. And yes, make no mistake they are dry. In fact, my first Feld purchase wasn’t solely driven by its bargain basement price–what a deal, but rather in an effort to really see what people meant when they talked about a dry Euro. We’d played lots of dice-rollers and card games, as well as a handful of more modern mashups of mechanics–games that bridged Ameritrash conflict and randomness with crunchier strategy. We had not, however, really played a straight up Euro, which is what lead me to purchase arguably one of Feld’s first bonafide classics, Notre Dame (2007).

Very soon, it was apparent what we’d been missing.

Swimming in Your Ocean (The Feld Design)

Board games are built from mechanics (or mechanisms, if you prefer). A fairly comprehensive list can be found here, but just a few examples are worker placement, rondel, negotiation, dice rolling, area majority/influence, or racing. As I said, these are functionally the building blocks from which games emerge. An effective game is some amalgamation of a small number of these, tied together by a theme and aimed at a common goal or victory condition for the players to pursue.

Feld’s designs are notoriously busy. While he rarely designs games that are considered “heavy,” he’s often criticized for games that appear as though everything but the kitchen sink was included in the design. For example, in Feld’s Trajan (2011), Board Game Geek lists the included mechanics as area movement, card drafting, hand management, mancala, rondel, and set collection. There are a multitude of excellent games that are designed using any one of these mechanics only.

While, on paper, the kitchen sink may be thrown into his games, in actuality the gameplay is a different beast. In general, we take a minute to learn how to play a Feld game, but this is usually due more to the wide variety of options and ways in which you can gain points rather than how complex the overall experience is. More often than not, Stefan Feld’s games offer players a wide variety of methods with which points can be earned, explaining the creation of the very Feldian term “points salad.” There are points to be had everywhere, and the question is no longer how to get points, but how to get points efficiently.

The combination of many mechanics, many methods of gaining points, and skinny theme have combined to make Feld games easy targets for criticism. Ultimately, it depends on where you’re coming from. If you like games that offer options, variable strategies, and myriad choices, Feld games are for you. If you prefer streamlined and thematic games, the odds are strong that you’ll have a hard time connecting with these games. More often than not, while I find the designs fascinating in how the multiple mechanisms interact, it still does feel mechanical. Rare is it that the individual game mechanics will “fade away” into the experience of playing or narrative presented by theme. You’ll always feel the mechanical nature of his games. But that’s okay. The satisfaction here comes from the puzzle of working the machine.

Six Four Days at the Bottom of the Ocean (AquaSphere as Feld)

For a frame of reference, we own five Stefan Feld designs: In the Year of the Dragon (2007), Notre Dame (2007), Bora Bora (2013), AquaSphere (2014), and Castles of Burgundy: The Card Game (2016). Before you ask, we purchased the Castles card game because it is significantly cheaper than the board game and, by all accounts, provides a very similar experience. Of these five designs, they all can be described as both a kitchen sink of mechanisms and point salad. At the same time, they all have a certain polished feel. My above description of Feld seems to read as “his games are Frankensteined abominations of mechanics!” but that’s misleading. Yes, they are hammered together, but that polish is still unmistakable. We’ve played plenty of other games that feel like Feld, but they usually get a little lost in some labyrinth of rules exceptions often missing from Feld’s generally clean designs.

That being said, AquaSphere is the heaviest of our Feld games, complete with its fair share of exceptions, and strategically this may be one of the heaviest games I can think of. I want to reemphasize that word “strategically,” because while teaching this intimidated me, Kathleen was not actually intimidated learning it. For some reason, the circular board (seen up above) feels like a lot to take it, but it’s really just six pods made up of seven rooms repeated in varying arrangements.

Played over four rounds, AquaSphere is about, you guessed it: scientists working in an underwater aqua sphere. On your turn, you’ll do one of two things: program a bot or use a programmed bot. Using a bot is essentially the same thing as “taking an action,” meaning it will take at least two turns to simply do an action. That two-turn process of taking an action is merely one way in which the game’s strategy handcuffs you. Often in points salad games, there is a limiting factor in what you can do (eg dice placement’s reliance on what your dice facings are), but in AquaSphere, there are many handcuffs. Not only are all actions two steps, but the game is based around a programming board, dictating which sequence of actions you’ll be able to do. As you progress forward on this board, your path will cut you off from certain actions. The board looks like this (image courtesy of BGG user lordalatar):

As you program bots and then deploy them across the station, you’ll be using them to fight for control over each of the six pods. At the same time, you’re working to add new lab sections to your own personal lab area, deploy submarines, and fight off the growing hoard of octopods that threaten to take over the whole joint.

I can’t even begin to really teach this game via writing without getting totally derailed, so I absolutely recommend watching Rodney Smith’s Watch It Played for AquaSphere. At the end of each round, one of four total intermediate scorings will take place. Check out the individual player board:

Scoring aids are listed on the right side. The top spiral notepad is intermediate scoring, and the bottom clipboard is end-game scoring. Those lightbulbs are the symbol for POINTS. See? point salad. Plenty of ways to bring those points in.

Again, I’m not going to go in-depth on how to play, nor will I talk about strategy, as this is merely a first impressions post, but I have to say that of Feld’s designs, this was the hardest to get my hands around. At first, I wasn’t even sure what I was doing when we first started. I had to get to an end-of-round intermediate scoring to even see what I should be focusing on. Area control is very important here, but as you grown your influence, those pesky octopods will become a real problem. Should you fight them off or build your lab? Or, perhaps more importantly, get those subs out? But without working on picking up time markers, you won’t be able to get the high cost submarines out.

Many of Feld’s designs revolve around the idea that, on your turn, you need to do 10 things, but you only have the ability to do two or three. AquaSphere presents players with this dilemma in spades. Perhaps because of this game’s baked-in difficulties, AquaSphere seems to have struggled very much to find an audience.

Beyond the Sea (Our Bottom Line on Feld & AquaSphere)

Where Castles of Burgundy is one of the most popular games on Board Game Geek, AquaSphere seems to be known as Feld’s “bargain bin” game. After Tasty Minstrel’s lovely US release and The Dice Tower’s subsequent negative review, it seems many players passed on this, which is rough, but unfortunately understandable. This game manages to be both complicated and complex in play. Additionally, forcing players to plan very far ahead tends to alienate the idea of “casual play,” and AquaSphere absolutely requires long term planning. I waved at so many points as they passed me by during our first play. At one point, Kathleen had written her entire strategy for a round out on a nearby legal pad.

Feld’s popularity in the hobby is unmistakable, but his design philosophy and aesthetic seem to be polarizing. And when you introduce a game that is overly demanding of its players, a design can take another step in the direction of alienating players who don’t live for the puzzle. There’s a reason that Castles of Burgundy is his most popular game. As Feld’s games get heavier, they become much more niche, but that same logic can be applied to any designer, right?

For the record, I think Stefan Feld’s games are remarkable. There is a polish here that you don’t even notice until it’s missing. So many Euro designers build complex, mechanically heavy games, and unfortunately, the smoothed edges of Feld’s designs become so much more evident when you play a game that’s all sharp edges.

That being said, I am of two minds on AquaSphere. In one hand, I think this game is a bit much. too many options, too many handcuffs, and too many variables. At the same time, I love the challenge of this game. For each handcuff or unexpected wrinkle, I remain undaunted, and instead desire only to do better next turn.

AquaSphere is a hell of a puzzle, and if you get a chance to play it, I think it’s worth it. I’m looking forward to my next opportunity to lose handily.

Player One

Eric

0 notes

Text

Episode 20: Picture in a Frame

The Gallerist by Vital Lacerda

Episode 20: Picture in a Frame

0 notes

Text

I Need a Hero (Marvel Champions LCG)

Do we really need another infinitely expandable card game with a comic book superhero theme that can easily be played solo but also plays remarkably well with two?

UM YES OF COURSE.

Marvel Champions: The Card Game (2019)

Designed by Michael Boggs, Nate French, and Caleb Grace

Art by Marvel

Published by Fantasy Flight

I love the idea and format of the living card game. I know this is not always the most popular opinion in the tabletop hobby. Living Card Games tend to be a bit of a lightening rod for criticism, given that they can get expensive if you go “all in,” unless the player is coming from the collectible card game niche of the hobby. In that case, Living Card Games feel comparatively cheap. Being as I played lots of Magic: The Gathering, I’m used to the idea of paying for cards, and it doesn’t bother me. Granted, not everyone feels that way, and I understand, but I want to clear the air now and say that, for me, the release model of this game is not a bad thing.

Anyway…

Lowdown (How to Play–in a Nutshell)

If you have any experience with a cooperative Living Card Game, either The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game (2011) or Arkham Horror: The Card Game (2016), then the uber-generically titled Marvel Champions (2019) will feel very familiar. The main connecting line that runs through each of these games is Nate French, an in-house designer for Fantasy Flight, so it’s not terribly surprising that there’s a mechanical overlap.

You’ll come to the game with a pre-built deck consisting of cards that belong specifically to a certain hero (the base box includes Black Panther, Spider-Man, She-Hulk, Captain Marvel, and Iron Man), as well a set of cards linked to one specific trait (like Justice or Protection), and then a few all-purpose neutral cards. With this deck, you’ll play cards and act with your hero to foil schemes associated with a villain. Rather than thwarting the villain’s scheme, you can attack the villain instead. On the villain’s turn, they will advance their scheme and then either attack you or scheme some more. Once that’s done, you’ll draw card(s) from the villain’s customized encounter deck and deal with those.

When you’ve defeated the villain, ie gotten their life down to zero, you win. Being as this is a cooperative game, you’ve got plenty of ways to lose, but if you lose it will most likely be that your own health was driven to zero or the villain was able to complete their scheme.

Tea for Two (Scaling for Two Players)

This game plays up to four, and all aspects of the game relevant to player count scales automatically (including how much life the villain has, how quickly the scheme will advance, and how many cards from the villain’s AI encounter deck are drawn each turn). While it plays up to four players, I’d probably shy away from playing it at the full count because the game would take significantly longer. However, in all honesty, I’ve only played the game solo, but Fantasy Flight’s cooperative LCGs have a great track record with two players in this household, and based on the comprehensive design similarities, I have no reason to think otherwise.

The Never-Ending Story (The Bad Stuff)

Okay, so I’ll be honest here, I probably could have told you the bad stuff prior to playing this game. Now that I’ve played it, I can tell you that the problematic aspects of this design are inherently part of the conscious choices made by the designers. That being said, you’re either going to be bugged by these design choices or not, but they were all intentional.

First of all, Marvel Champions immediately distinguishes itself from both The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game and Arkham Horror: The Card Game by eschewing the campaign system that runs both of those games in favor of a non-campaign, one-off episodic design instead. Rather than experiencing a slowly developing narrative played out over multiple games, you will only ever really experience this game in self-contained, narratively loose skirmishes. I hesitate to even use the word narrative, honestly. If you read the cards, including flavor text, you’ll get an idea of what’s supposed to be happening, but it’s nothing at all like Arkham Horror, the most heavily narrative game of the bunch, or even The Lord of the Rings, a decidedly lighter narrative experience.

This is not a bad thing for me, and I say that because I feel the campaign system actually keeps both Arkham and Lord of the Rings from hitting my table more frequently. Arkham felt like it relied too much on the narrative (for my taste), while Lord of the Rings’ narrative made me feel guilty to ever play without Kathleen, so often I’d want to play but not want to play without my gaming partner, meaning on the shelf it stayed. Also, because Marvel Champions is not narrative-based, you can skip any small expansion if you’re simply not interested in the hero without having to worry that you’re missing out on the story, making this inherently cheaper than other narrative LCGs. Again, this is very subjective. I’m sure that there are people who would say the narrative aspect of Arkham is what makes it the most rewarding of the lot, but for me if the story stumbled, the whole experience suffered for it (and I wasn’t so keen on a few of the Dunwich Legacy narrative choices).

Next up is the nature of the cooperative LCG. In this case, I don’t mean the release model, but rather the fact that the encounter deck, present here just as it is in both Lord of the Rings and Arkham, can be punishing. Ultimately, the probability of you succeeding is not only based on your strategic decisions in the game, but also on the luck of what is drawn from the encounter deck–and when it is drawn. More often than not, if you draw the deck’s cruelest cards at the worst moment, it will be all but impossible to overcome. You can prepare yourself as best you can, certainly, but sometimes winning is just not in the cards (Great job, Dad joke). Again, this is not a big enough problem to really bother me. I have certainly been frustrated playing Lord of the Rings, and that’s because, of the three, Lord of the Rings is the most punishing, by far. Arkham is second most, and Marvel Champions is actually the least punishing. At the same time, because of the cooperative aspect, I don’t mind the game feeling punitive. That’s the point, no? What’s the point of playing an easy cooperative game?

The only other drawback that someone might immediately raise objection to is actually something I really like. Deck-construction in this game is much simpler than with either Arkham or Lord of the Rings. Those two games are based on simple deck building restrictions revolving around factions, not terribly unlike Magic: The Gathering. Deck-construction in Marvel Champions has more in common with Star Wars: The Card Game. In Star Wars, cards come in blocks (or pods, if you’d prefer a whale metaphor). You choose an objective, most likely for a special ability, and with that objective you’ll also have a set of cards that will begin to build your deck, usually keyed to combo around the objective’s ability. As you select objectives, you’ll get their accompanying cards and slowly construct a deck, meaning decks are based on small, pre-built sets of cards rather than individual cards. It makes the build infinitely simpler.

Deck-construction here is similar. You’ll pick a hero and take a set number of cards as your deck starting set (like your 15 Iron Man cards or what have you). Then you’ll select one of those traits I mentioned earlier (Justice, Leadership, Aggression, or Protection), and add a certain number of cards from that trait. This is the most loosey-goosey bit, but the fact that you cannot combine traits really helps. Then you’ll augment what you’ve got with some neutral cards. Ultimately, your deck is only 40 cards, making it very easy to get a basic deck put together. While I am not a huge fan of tinkering with decks, making this a good thing, I completely understand this being a blemish on the game for those who really live and die for a good build experience.

There Goes My Hero (The Good Stuff)

All those gripes being said, Marvel Champions does plenty of things that I quite like, and that distinguish it from Lord of the Rings and Arkham.

First of all, Marvel is the lightest of the bunch. Along with the superhero theme, it’s clear that this was meant to be more of a gateway game. It’s not what I would call LIGHT, but it’s mechanically simpler than Arkham, and much simpler than Lord of the Rings, which I believe is clearly the heaviest of the bunch.

As an example, resources as you are used to are not here. Rather than managing a pool (or pools, in the case of Lord of the Rings) of resources, you pay for cards by discarding other cards from your hand, an evergreen mechanic that is so satisfying in its deceptive simplicity. Race for the Galaxy (2007) is another game that employs this same simple mechanic. What that means is that while the game is removing mechanics, its emphasizing the hand management here. And interestingly enough, your hand size will fluctuate based on if you are in Hero or Alter-Ego mode (ie which side your avatar’s card is face up). As your hand size fluctuates, it will present you with very difficult situations about whether you should hang onto cards and try to grow your hand size or discard as needed to pay for other cards.

And speaking of the Hero/Alter-Ego mode, this is one of the most satisfying puzzles of the game, because on your turn you can switch between these two modes, but only once per turn. Once the villain’s turn begins, they’ll interact with you differently based on if you are visible as a hero or disguised in your alter-ego. If you’re in hero mode, they attack you. If you’re in you alter-ego disguise, they’ll work on their scheme (slowly marching towards the end of the game). Is it better to stay in Hero mode and fight, thereby slowing the scheme’s progress? Or is it better to let the scheme progress so you can recover (heal) in Alter-Ego mode. Other than card abilities, this is the only way to increase your health, making it very important. This dilemma is so satisfying. What should you do, and when is always a delightful pickle to face.

And the theme. Yes, I love Marvel comics. I’ve read a fair amount of Marvel comics, mostly bronze age, and I find the implementation of theme here simple yet very effective. The mechanics are clean and streamlined, meaning some amount of theming is abstracted away, but so many of the card abilities are instructed by the hero’s comic book abilities. For example, Iron Man is underpowered at the start of the game (with a base hand size of only ONE when he is Iron Man), but as the game progresses and Tony is able to install upgrades to his suit, he will slowly become more powerful, and significantly more powerful at that. And as he adds upgrades, his hand size will grow, giving you a true feeling of acceleration

True, it’s still a card game, meaning that much of the heavy theming you may find in a more in-depth or complex board game is abstracted away. That being said, I really enjoy the implementation of theme here.

The End (Final Thoughts)

I apologize if it seems I’ve belabored the bad things, because that’s actually misleading. I think this game is great. Essentially, it’s exactly what I wanted. It plays well solo, it presents a ton of difficult choices, it’s hard, and it’s not campaign based. I can sit down and knock out a satisfying game of this in 30 minutes. It’s definitely challenging, and the heroes all feel very different when you play them. The Alter-Ego vs Hero modes not only present you with different abilities (most heroes have special abilities that are available to them based on which mode you are in), but there are also cards scattered throughout each hero’s deck that can only be played if you are in one mode or another.

In regard to the villains, I also want to mention the fact that there are nemesis cards associated with each hero, like Killmonger for Black Panther or Titania for She-Hulk or Vulture for Spider-Man, who can be brought into play based on a specific card being drawn from the encounter deck. Each hero also has an obligation card specific to them that may be drawn to complicate their lives. The obligation cards usually entail the hero having to choose between being in Hero mode or Alter-Ego mode. For example, Spider-Man’s obligation card is “Eviction Notice,” which forces him to essentially turn back into Peter Parker and deal with the problems in his day-to-day life. When you do that, however, it allows the villain to scheme, once again pushing the game towards its ending. This aspect is so clean, but so clever and thematic.

For a game that is really fairly simple, Marvel Champions presents so many tough choices, eliminating some of the heavy resource management and complex card-play inherent to Lord of the Rings or Arkham Horror and replacing it with more puzzly questions of timing and hand management.

If you like tough and clever card games, this is definitely something you’ll want to check out. For me, the only thing preventing this from getting the highest marks is the fact that I still have a strong personal affinity for Lord of the Rings, a game Kathleen and I have played loyally for years. But if you’re new to the land of cooperative LCGs, this could be your newest obsession.

Player One

Eric

#board games#board game review#marvel#marvel champions#living card game#fantasy flight games#board game#marvel champions board game review

0 notes

Text

Back Issues: Episodes 7-19

Boy, howdy, I am behind on this. If you’ve been keeping track in Podcastland, you probably know we’re coming up on episode 20 of PLAYER ONE | PLAYER TWO PODCAST, and I’ve simply been remiss in keeping up the blog. Infinite apologies.

Since our last episode posted, on which we covered The Dresden Files, we’ve covered a host of games, most of which have been excellent...

Comanchería by Joel Toppen, covered in Episode 7: High Lonesome

Villainous by Prospero Hall, covered in Episode 8: World’s Great Criminal Minds

Star Wars: The Card Game by Eric M. Lang, covered in Episode 9: The Dead Sea, Part 1

Evil High Priest by Sandy & Lincoln Petersen, covered in Episode 10: Am I Evil?

ZhanGuo by Marco Canetta & Stefania Niccolini, covered in Episode 11: You Can Get It If You Really Want

Fluxx by Andrew & Kristin Looney, covered in Episode 12: Take a Chance on Me

Targi by Andreas Steiger, covered in Episode 13: Two Step

5 Minute Dungeon by Connor Reid, covered in Episode 14: Time is on My Side

Detective by Ignacy Trzewiczek, covered in Episode 15: I Fought the Law

Our Current Top 10 Games! (9/19) covered in Episode 16: Still the One

Watergate by Matthias Cramer, covered in Episode 17: Know Your Enemy

Welcome To... by Benoit Turpin, covered in Episode 18: Little Pink Houses

Founders of Gloomhaven by Isaac Childres, covered in Episode 19: Build Me Up Buttercup

Get caught up. Send in any questions or suggestions. And play on!

0 notes

Text

Only a Pawn in Their Game (Nippon)

During an old video review published by the clever and astute duo of No Pun Included, Efka Bladukas said, quite deadpan, that “Nippon” was Japanese for “efficiency.” It was so deadpan–and I’m apparently enough of a philistine–that I believed it, no questions asked. You probably know that “Nippon” is actually is just a Japanese word meaning, ummm, “Japan.” It’s literal meaning is “the sun’s origin,” as in “the land of the rising sun.”

My naiveté aside, whatever the word for “efficiency” in Japanese is, that word would be a great name for Nippon, too!

Nippon (2015)

Designed by Nuno Bizarro Sentieiro & Paulo Soledade

Art by Mariano Iannelli

Published by What’s Your Game?

Its gorgeous cover aside, Nippon is one of the more stock-looking euro game–at first glance. Cubes, factories, a map with places for you to put markers of your color. Zzzzzzzzzzzzz... But wait! Not terribly unlike Village (2011), Nippon can almost hear what you’re thinking, but unlike Village–which added one mechanic to put a nice spin on a typical euro–Nippon subverts your expectations at every turn. Worker placement? Not really. Long term planning by saving your money? Hah! You simply cannot do that. Fulfilling orders/objectives for points? Not for points, brother.

Options are myriad, rounds are short, and no matter what you do, the game will be forcing you to pay through the nose every step of the way.

Lowdown (How to Play–in a Nutshell)

This game is fairly heavy, so rather than discuss actual actions or granular nuts and bolts of play, I’ll try and give you a broad overview and highlight some of the unique aspects of the game.

Nippon, by all accounts is a worker placement game, but not really. Those workers are the first thing you see when you first look at the board, but it’s all a ruse. At the top of the main map board are five columns, with all but one associated with two different action spaces (that fifth space is associated with only one big action space). Above each top action space, a random assortment of workers are sprinkled both during setup and in periodic refreshers throughout play. These workers are basic meeples of a variety of colors. On your turn you’ll take a meeple and add it to a track on your board, then you take one of the actions in the corresponding column. As you take more actions, maybe you’ll have a technicolor collection of workers on your track, or maybe you’ll be lucky enough to get duplicate colors (this is a good thing, by the way). Soon enough, you’ll be out of room on your track and you’ll need to take a consolidate action, instead, which will clear off your track, replenish your money and coal, and allow you to take more actions. The catch is that you have to pay your workers based on color. So if you have four workers of four different colors (eg red, blue, yellow, and white), you’ll be paying for a total of four workers. But if, instead, you have four workers of two different colors (eg two reds and two greens) you only have to pay for two workers. Duplicate colors are free!

Consolidating in Nippon is essentially that upkeep phase you have in many euro games. That being said, the game incentivizes you to wait longer before consolidating. The more workers you have on your track, the higher an end game scoring multipliers you’ll receive to place on your board, helping steer you towards some points at the game’s end. For example, if you have enough workers in your track, you will gain a x5 multiplier for you to put on an end game bonus space, like a space that signifying regions on the board. (This is hard to explain, but essentially in this example, once you get that x5 multiplier, it means you will gain 5 points for each region you’ve gotten one of your markers into by the end of the game; there are other spaces meaning things like “for every 6,000 Yen” or “for every advanced factory you’ve built,” etc)

Anyway, what are you doing with these workers? The point is to build factories, produce goods using coal, and then ship your goods oversees to fulfill orders for money and bonuses, or instead ship your goods locally across Japan to take a market share of an industry in a specific region. Each time you need to replenish meeples and there aren’t any meeples left, you’ll advance the turn marker one step forward. If you pass a scoring marker, you’ll score points for area control (or sometimes just presence) in each region on the map. The more goods you ship, the better your control is. After the third scoring round, you’ll add up all points, including from the end game multipliers you’ve been accumulating throughout the game, and the player with the most points wins.

Tea for Two (Scaling for Two Players)

Nippon is a reasonably fast game with two, but I’m not sure how fast it would be with three or four. The number of seeded meeples is different based on the player count. The first time we played, the game felt too short, but subsequent plays haven’t felt too short, but rather fast enough to drive you, but not so fast that you don’t have time to do things. Just fast enough to see the mistakes you make and wave at them as they fly by.

The other main scaling factor is that with two players only, there is a limit to the number of markers you can place in each city (two), meaning more often than not you’ll have one of each player’s color in each city. Each city will score points after each scoring phase is entered, giving points for first, second, and third place (the highest level marker you put out). But, to complicate things, each empty city space has a value in it, meaning that there is functionally a phantom player fighting for control of each city, too. Any uncovered number counts towards that phantom player’s control value, making it very difficult to get that coveted top points space in the area control scoring round. At most, you’ll probably get second behind the game itself.

All this is confusing to explain without really running through the rules, so I’ll just cut to it: this plays great with two.

Thorn Within (The Bad Stuff)

By all accounts, Nippon is a worker placement game (although Joel Eddy of Drive Thru Review Games described it beautifully as “worker displacement,” which is dead on), but all that worker juggling doesn’t actually score you any points. At first, you’d think the workers are really the main engine for those points, but they’re more like your utility tools in doing everything else. The points here are almost all in area control, not in production or any of the other basic action, and that’s deceptive. It’s all about the area control. Speaking of scoring via area control, if you find yourself running behind in the game, you are going to be hammered. And back to those workers, they really just stand in your way more often than not. Those workers are a money pit, because you have to pay 3,000 Yen for each difference color.

This can be really frustrating, because sometimes those meeple colors do not favor what you’re doing, and instead of picking four meeples and doing those for things you really need to do, you can’t because you can’t afford four different colored meeples. And slowly but surely, you have to sit and watch your opponent get their pieces on the board and score while you are stuck trying to scrape up money to catch up. There is a ton of stuff you can focus on in this game (upgrading machinery, building trains, building boats, upgrading coal production, fulfilling foreign orders, etc), and it’s easy to get lost down a rabbit hole that turns out to be, points-wise, a total dead end. But all of these aspects are interconnected, so you feel like you have to do everything. Nippon forces you to make tough decisions, and it often leaves you nothing but regrettable choices. You need to produce, but you don’t have enough coal; you want to up your coal production, but that won’t give you coal now, you need to ship locally to get a marker on the map, because if the next player takes that one meeple, it will trigger a scoring round and you’ll lose your shirt!

Not unlike Heaven & Ale (2017), Nippon is hard on the players. I wouldn’t call it brutal or unforgiving, but instead it feels like Nippon is a taskmaster. The game is demanding you to be an efficient manager, but it’s giving you no resources and no time to do it.

Carpe Diem Baby (The Good Stuff)

A lot of those bad things, well, they’re excellent. One of the more remarkable moments I’ve had in a game recently was a round of Nippon where I had a handful of actions I felt like I had to do, but I ended up abandoning my turn and consolidating early because I realized that I was better off not taking a new colored worker and spending 3,000 more Yen to pay for it. Here’s the thing about Nippon, when you consolidate, you lose all of your unspent money and coal. Yes, all of it. it is impossible to save your money turn-to-turn in hopes of paying for lots of workers in one turn and having that BIG TURN. That 2,000 Yen you didn’t spend this turn won’t roll over. Ditto next time. If you didn’t efficiently utilize your workers and money to maximize your turn, that’s tough on you. Remember, Nippon is Japanese for “efficiency” (it’s still not, by the way), so if you aren’t efficient, you are going to watch your money go up in smoke, along with your chances of winning.

Not having the ability to build up to your BIG TURN, Nippon forces you to grind your way through the game, slowly trying to out-think or out-maneuver your opponent. Should you fulfill overseas orders to increase your income level? That always feels like an excellent idea, because money is everything, and the more you have, the more you can do. At the same time, if you lean into fulfilling orders, the game will just slip away from you. Your carefully produced goods are hard to make, are you willing to pass up putting your markers on the map by fulfilling local orders just so you can make 2,000 more Yen each turn by fulfilling an overseas order? Cash will help you optimize your factories maybe, but what good will that cash be if you have no coal? What good will that cash be if you don’t have enough time to produce and ship? Cash converts to points, but it’s a bad conversion rate.

I can’t say enough about the gameplay of Nippon. This game is perfectly suited towards how I think, and the fact that it is essentially a game of nothing but tough decisions means it feels like it was designed for me. The worker displacement is puzzly, the rounds are fast and furious, and the game demands you to fight like hell to score those points. Love it.

The End (Final Thoughts)

Kathleen isn’t a huge fan of Nippon, but it’s a matter of preference. She agrees the game is remarkably well-designed, she just doesn’t like the demands it makes of the players, and I understand. Nippon forces you to diversify your actions, but ultimately all in service of the area control. If you aren’t able to manage that area control effectively, you will find this game very frustrating. Despite that respect for the design, it’s simply not suited to Kathleen’s play style.

At the end of the day, the good things and bad things are, for me, both good things. Everything I put into the “bad stuff” section ultimately equates to more tough decisions. I like that the game is a four course meal of which you can only eat one appetizer. Nippon presents you with a whole host of options, but gives you only the time and money to do 1/4 of what you’d like to do in a perfect world. Everything boils down to that time and money, and those are in such short supply here.

We played this game a bunch of times in the week or two after I got it, which got it into my top 10. It went dormant for a while. We pulled it out last week, and part of me was afraid it would have cooled a little. It didn’t. It climbed even higher in my top 10 list. It’s fantastic, and now it’s one of my favorite games.

This box is so crammed full of difficult choices, I can’t help but marvel at how difficult the decisions feel. For me, Nippon gets the highest marks. That being said, I fully understand it’s not for everyone. But if anything at all about this sounds interesting, get it. Get it now.

Player One

Eric

#board games#board game#board game review#review#nippon#What's Your Game?#Nuno Bizarro Sentieiro#Paulo Soledade

0 notes

Text

Episode 6: You Don’t Own Me

The Dresden Files Cooperative Card Game by Eric B. Vogel

0 notes

Text

The Village Green Preservation Society (Village)

Over the past few years, Inka and Markus Brand have been on fire. The husband and wife designer duo have, in the past three years alone, released the lovely dice-placement racer Rajas of the Ganges (2017), come out with their own sprawling take on the legacy game in The Rise of Queensdale (2018), and played their part in changing the hobby forever with their remarkable Exit series (2016-?).

But if you roll back your calendar a few years, you’ll find a lovely gem of theirs about simpler times. Rather than escaping certain death in Exit or building a grand and majestic estate in Rajas of the Ganges, you are, well, just living your life. Train to be a wainwright or stableman, make your mark, live a long and hopefully productive life, perhaps join the city council or the church, and leave a legacy to be remembered in your small town forever.

Simpler times, indeed.

Village (2011)

Designed by Inka & Markus Brand

Art by Dennis Lohausen

Published by Eggertspiele

Village is, at first glance, a fairly meat and potatoes euro about following four generations of your family through their simple lives in a small village. At its heart, this is a fairly straightforward resource management and conversion game. And yet, unlike so many similar games, there’s a little more than just picking up cubes and converting them into goods–although that’s certainly in the box, as well. Village is proof that the Brands’ inventiveness is no new thing. In addition to cubes, you’ve also got to grapple with time and its slow march forward. Every action takes time, and as time moves forward, those young’ns will grow, eventually becoming well-respected elders, continuing to age until they die and either become part of the village chronicles or are buried in the cemetery and are all but forgotten.

Lowdown (How to Play–in a Nutshell)

Before you ask: yes, it’s about points. Points, points, points.

Colored cubes and action selection combine to define Village. A certain amount of cubes are mixed randomly in a bag before being randomly distributed among a number of action spaces. On your turn, you will take a cube from a space, put it on your individual player board, and then you may take the action from that corresponding space. Each action will have a cost in time, and time is kept on a circular track on your player board.

The colored cubes will accumulate, and soon you will be cashing them in when you select an action in order to convert those cubes into different resources in the form of tokens. One color cube, however, is a plague cube, and if you choose (or are forced) to take a black action cube, you must advance time further.

The actions, which I’ll cover only briefly, are all similar variations on a theme–essentially resource conversion or selling items for points. You can take bags of grain in a harvest (another resource you can convert later or sell to market), grow your family (adding another meeple to your personal board), travel beyond the village (use wagons you’ve made to visit locations for bonuses), craft (cash in your cubes or grain to make wagons, plows, wagons, or buy/raise horses or cows), join the village council (points!), participate in church (points again!), and go to market to fulfill orders by selling your goods (the most points!).

In addition to simply trading in cubes to get other goods like plows or wagons, don’t forget you’ve got those meeples. You’ll often also deploy those meeples as family members to a particular location to make it easier to do that action in the future–essentially because you have trained them in that craft. The idea here is that the second time you need something, like a wagon, you’ll be able to go to your Auntie Edna or Uncle Pete, now trained as a wainwright, and get a wagon spending only time, rather than spending those precious cubes you’ve been hoarding.

When you’ve advanced your timekeeper far enough, however, one of your oldest generation-meeples must die. Slightly macabre, perhaps, but arguably realistic. Those family members will either take one of a few spaces in the village chronicles (for lots o’ points!), or be buried in the village graveyard (for no points!). After the village chronicle or graveyard is full, the game ends. Most points wins.

Tea for Two (Scaling for Two Players)

Each aspect of the games is scalable, with the village chronicle having fewer spaces for two players vs three or four, as well as fewer cubes and fewer market orders for fulfillment. In a two-player game, you’ll have a lower likelihood someone will take a cube you’ve been eyeing, but beyond more limited screwage–which is normal for a two player game vs a three or four player game–scaling is very good here, not really altering the experience at all.

Death to My Hometown (The Bad Stuff)

The mechanics here are very sturdy, albeit typical, euro fare. Take a cube, do an action. Take a cube, place a meeple. Take a cube, convert cubes for tokens. Take a cube, sell tokens. Rinse and repeat. This is a reliable game engine, built on an equally reliable chassis. Many of the actions feel comfortably familiar: harvesting for grain (take a resource) or the “family” action (put out another meeple from your supply), market day (sell for a variable market tile aka convert goods to points). About a half-dozen games immediately come to mind that rely on very comparable actions, and the reliance on cubes here abstracts these actions further, moreso than some of the others. The rulebook states (and I had to look this up because I don’t remember this at all) that orange cubes represent skill, green cubes persuasiveness, brown cubes faith, and pink cubes knowledge. I like that the cubes have some representative analog, but once you play, they completely lose any semblance of meaning beyond their color. A game like Clans of Caledonia (2017) has similar actions (build things, sell things), but feels infinitely less abstracted. Action-wise, Village is not reinventing any wheel.

The other hit Village will take is on the graphic design. A meat and potatoes euro game designed in 2011 looks–today, at least–very dated. It has all the attractive graphic design of a shag carpet and lava lamp. Ten years in board game graphic design is 30 years in fashion or interior design. Board Game graphic design still remains a vulnerable spot in the armor of a great many euro classics, and in that regard, Village is no different. Some publishers have learned a lot since 2011, but even today, Eggertspiel isn’t known for its flashy look. Village is a prime example of their perfectly utilitarian–if nothing to write home about–art and graphic design.

Local Hero (The Good Stuff)

I’d heard a lot about Village prior to playing it, and after reading the rules, I was a little confused about some of the more effusive praise that had been heaped on it. The mechanics are so… generic euro. After playing it, though, I realized something remarkable about it: Village is greater than the sum of its parts.

Being a person of slightly above average cynicism, perhaps, I find it rare to say that about a game. More often than not, I hear about a game and get excited–whether that’s because of the designer, mechanics, theme, art, or some combination of all–only to find the experience of playing it somehow less than the sum of its parts.

So why does Village succeed where other, more immediately engaging or interesting games ultimately fail?

For me, in a nutshell, it’s because of the time mechanic and the familial/generational development. Somehow, a game with a fairly bland and only moderately well-implemented generic euro theme (farming/working in a town/selling stuff, etc) manages to build a story as you play. The story I’m referring to is not actually in the game, mind you. This game does literally nothing to create a narrative for you. There aren’t even basic event cards, like This month there is a storm! Oh no! Better stock up on grain to sell so you don’t starve! Rather, somehow, a story manages to slowly and unassumingly coalesce for you as you play. Let’s say on your first turn you take a meeple and invest the time to train them as a stablehand, becoming skilled at raising horses and cows. You begin to sell your cows at market, and with cows, you’ll be well on your way to a much better harvest, because you’ll now be able to plow for more crops. With more grain, you can fulfill orders, or take those bags to the mill for money (aka points!). Or maybe you’ve got a barfly Uncle (with the expansion, Village: Inn (2013), at least). Maybe he was, over the years, able to buddy up, over a weekly shot and a beer perhaps, with the bigwig Count, guaranteeing that you’ll get more points at the game’s end if someone else in your family is able to visit him by traveling to his faraway castles! Excellent!

Oddly enough, this kind of thing is also present in other games. Giving a meeple a profession does not a story create. To put my finger on it, and I don’t want to sound maudlin, but for me it’s that death mechanic. I’m not exactly a softy, but is remarkably effective, to say nothing of affecting (although that’s may be a slightly-strong word). Your nameless meeples are bestowed with something akin to preciousness as you’re forced to usher them to the village chronicle, or more unfortunately, the graveyard.

Ultimately, there’s something ineffable about Village, something beyond the simple mechanics of it. There’s something remarkable here and worth exploring.

The End (Final Thoughts)

I was a bit flowerier than usual in The Good Stuff, because it’s hard for me to say what works so well about Village, but to turn back to gamier terms, there’s lots of great and satisfying strategy here. Lots of tactical decisions, lots of scrambling to meet objectives, errr I mean market orders. Lots of dilemmas, lots of time management–never enough time, btw–to say nothing of never enough of those dastardly cubes. There’s a lot to manage, but never so much that it becomes overwhelming. There’s new stuff here, but not enough to be daunting or difficult to manage, and it’s a game that is just welcoming enough to be taught to new-ish folks to the hobby. And the time, again, that time. For every first or second generation that you drag your feet to remove from the board, equally interesting is how you may, at times, rush these folks through their lives in hopes of sneaking them into the village’s chronicle before someone else.

So much of this game feels expected, but it’s surprising how much one little wrench can do to the works of a machine and ultimately defy all of your preconceptions. My first impression of the Brands was formed in playing Exit, which duly impressed me. Upon playing Village, however, I was delighted to learn that their seems to be no end to their ingenuity, and I will be keeping an eye out for anything that bears their name.

Player One

Eric

0 notes

Text

Editorial: ‘Til the Money Runs Out

(Unless otherwise clarified, all prices are MSRP, or manufacture standard retail price)

The subjectivity evident in any critical analysis of a book, movie, or board game is–I would hope–obvious. Value, however, feels far less subjective.

How much someone is willing to pay for something varies greatly depending on the person, not only based on what we’re talking about, but also how much money that person has. With that out of the way, let’s talk about a sticky wicket in the hobby of board gaming: value.

It wasn’t long ago that this idea felt less nebulous, with value often coming down to the argument of collectable games vs non-collectable games. Things are a little different now. Collectable card games (CCGs), expandable games/living card games (LCGs), legacy games, campaign games, mystery games, and consumable games have gone a long way in complicating a once-simple(ish?) idea. These days, everyone has an idea of what’s a good value, and what’s not. Lots of people have axes to grind against games deemed “of poor value.” I’ll try not to fall into such a black and white box.

When I originally thought about writing about value, my main angle was simple: Magic (1993) vs an LCG, like Android: Netrunner (2012) or Lord of the Rings: The Card Game (2011). As a former fan of Magic transformed into an avid LCG fan, I bristled at the less than rosy coverage most LCGs received from the gaming community, in regards to value specifically. I knew firsthand how expensive a collectable game like Magic could cost. With a 15-card Magic booster pack costing $3.99, and a booster box of 36 booster packs coming in usually around $100, it gets expensive quickly. Individual cards can be bought online for anywhere from 10¢ to $50+, this is a deep hole that is hungry and ready to eat you alive.

For anyone who has not played a collectable game, it is set apart from LCGs by randomness. A collectable game is purchased in packs of randomized cards, so oftentimes you will purchase a pack and get nothing you want or need. This happens far more than you would believe. LCGs/expandable card games are unique because they are available in fixed, non-randomized sets, whether that be small expansion packs of larger deluxe expansions. The rub is that these will cost more. For example, the typical small expansion pack for an LCG is typically $14.99, but you know exactly what you receive in that expansion, and additionally you’ll receive multiple copies of each card–something that never happens in collectable packs.

This distinction alone is worth a deeper dive, but we’ll only gloss over it briefly. Head to head LCGs or expandable games (like the now OP Android: Netrunner, Legend of the Five Rings (2017), Doomtown: Reloaded (2014), or Game of Thrones: The Card Game (2015)) offer a large pool of cards with a fixed distribution. You would conceivably be able to buy the core set for one of these ($40), plus perhaps four small expansions ($60 total), which puts you in at $100. For $100, you could buy a booster box of Magic cards and maybe build two strong decks, if you’re looking to have a satisfying experience. The randomness will throw a wrench in here, because you could theoretically get enough good cards for more than two solid decks; you could also get mostly junk.

Reviewers often balk at the LCG model, because while it appears to solve the money-pit aspect of CCGs, they are still not cheap. That being said, for people who are merely interested in the game–but not deck construction, LCG core sets offer plenty of introductory level gaming to help you discern whether you actually like a game or not. If you do, and you know what you like about the game (eg factions or mechanics), the set expansion packs allow you to build up where you want. Why buy an expansion pack for a faction you don’t like or don’t play? You don’t have to!

The cooperative LCGs are a different story. They, too, have the $15 expansion packs, but in addition to cards you’ll add to your pool for deck construction, you’ll also get quests to play against, essentially a typical “expansion” that brings in additional content beyond merely deck construction.

Whether it be cooperative or head-to-head, LCGs are expensive, but unlike CCGs, LCGs have simultaneously removed both the excitement of the blind buy as well as the frustration of the bad buy. Granted, in the small box expansions, you’ll still be getting cards you don’t need or don’t want, but at the very least, you will be getting at least a few cards you know you want (if not, uh... why did you buy it? Do your homework!).