Text

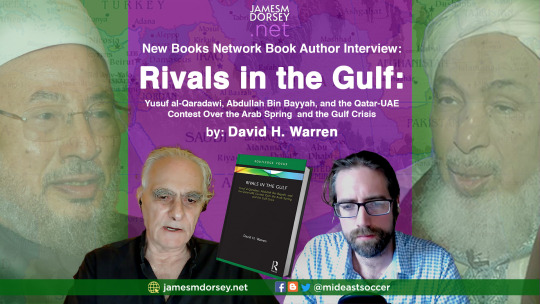

New Books Network Review: Rivals in the Gulf

By James M. Dorsey

Rivals in the Gulf: Yusuf Al-Qaradawi, Abdullah Bin Bayyah, and the Qatar-UAE Contest Over the Arab Spring and the Gulf Crisis (Routledge, 2021) goes to key questions of governance at the heart of developments in the Muslim world.

Warren looks at the issue through the lens of two of the foremost Middle Eastern religious protagonists and their backers: Egyptian-born Qatari national Yusuf a Qaradawi, widely seen as advocating an Islamic concept of democracy, and UAE-backed Abdullah Bin Bayyah who legitimizes in religious terms autocratic rule in the UAE as well as the Muslim world at large.

In doing so, Warren traces the history of the relationship between the two Islamic legal scholars and their Gulf state sponsors, their influence in shaping and/or legitimizing polices and systems of governance, and their vision of the proper relationship between the ruler and the ruled. He also highlights the development by Qaradawi and Bin Bayyah of new Islamic jurisprudence to religiously frame their differing approaches towards governance.

Warren’s book constitutes a significant contribution to the literature on the positioning of Islam in the 21st century, the regional competition for religious soft power in the Muslim world and beyond, and the struggle between autocratic regimes and social movements that strive to build more open systems of governance.

To watch a video version of this story please click here.

A podcast version is available on Soundcloud, Itunes, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, Spreaker, Pocket Casts, Tumblr, Podbean, Audecibel, Patreon, and Castbox.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and scholar, a Senior Fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute and Adjunct Senior Fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, and the author of the syndicated column and blog, The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and scholar, a Senior Fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute and Adjunct Senior Fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, and the author of the syndicated column and blog, The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer.

0 notes

Audio

Rivals in the Gulf: Yusuf Al-Qaradawi, Abdullah Bin Bayyah, and the Qatar-UAE Contest Over the Arab Spring and the Gulf Crisis (Routledge, 2021) goes to key questions of governance at the heart of developments in the Muslim world.

Warren looks at the issue through the lens of two of the foremost Middle Eastern religious protagonists and their backers: Egyptian-born Qatari national Yusuf a Qaradawi, widely seen as advocating an Islamic concept of democracy, and UAE-backed Abdullah Bin Bayyah who legitimizes in religious terms autocratic rule in the UAE as well as the Muslim world at large.

In doing so, Warren traces the history of the relationship between the two Islamic legal scholars and their Gulf state sponsors, their influence in shaping and/or legitimizing polices and systems of governance, and their vision of the proper relationship between the ruler and the ruled. He also highlights the development by Qaradawi and Bin Bayyah of new Islamic jurisprudence to religiously frame their differing approaches towards governance.

Warren’s book constitutes a significant contribution to the literature on the positioning of Islam in the 21st century, the regional competition for religious soft power in the Muslim world and beyond, and the struggle between autocratic regimes and social movements that strive to build more open systems of governance.

0 notes

Text

Athletes knock the legs from under global sports governance

By James M. Dorsey

Sports governance worldwide has had the legs knocked out from under it. Yet, national and international sports administrators are slow in realizing the magnitude of what has hit them.

Tectonic plates underlying sports’ guiding principle that sports and politics are unrelated have shifted, driven by a struggle against racism and a quest for human rights and social justice.

The principle was repeatedly challenged over the last year by athletes as well as businesses forcing national and international sports federations to either support anti-racist protest or at the least refrain from penalizing athletes who use their sport to oppose racism and promote human rights and social justice, acts that are political by definition.

The assault on what is a convenient fiction started in the United States as much a result of the explosion of Black Lives Matter protests on the streets of American cities as the fact that, in contrast to the fan-club relationship in much of the world, US sports clubs and associations see fans as clients, and the client is king.

The assault moved to Europe in the last month with the national soccer teams of Norway, Germany, and the Netherlands wearing T-shirts during 2022 World Cup qualifiers that supported human rights and change. The Europeans were adding their voices to perennial criticism of migrant workers’ rights in Qatar, the host of next year’s World Cup.

Gareth Southgate, manager of the English national team, said the Football Association was discussing with human rights group Amnesty International tackling migrant rights in the Gulf state.

While Qatar is the focus in Europe, greater sensitivity to human rights appears to be moving beyond. Formula One driver Lewis Hamilton told a news conference in Bahrain ahead of this season’s opening Grand Prix that “there are issues all around the world, but I do not think we should be going to these countries and just ignoring what is happening in those places, arriving, having a great time and then leave.”

Mr. Hamilton has been prominent in speaking out against racial injustice and social inequality since the National Football League in the United States endorsed Black Lives Matter and players taking the knee during the playing of the American national anthem in protest against racism.

In a dramatic break with its ban on “any political, religious or personal slogans, statements or images” on the pitch, world soccer governing body FIFA said it would not open disciplinary proceedings against the European players. “FIFA believes in the freedom of speech and in the power of football as a force for good,” a spokesperson for the governing body said.

The statement constituted an implicit acknowledgement that standing up for human rights and social justice was inherently political. It raises the question of how FIFA going forward will reconcile its stand on human rights with its statutory ban on political expression.

It makes maintaining the fiction of a separation of politics and sports ever more difficult to defend and opens the door to a debate on how the inseparable relationship that joins sports and politics at the hip like Siamese twins should be regulated.

Signalling that a flood barrier may have collapsed, Major League Baseball this month said it would be moving its 2021 All Star Game out of Atlanta in response to a new Georgia law that threatens to potentially restrict voting access for people of colour.

In a shot across the bow to FIFA and other international sports associations, major Georgia-headquartered companies, including Coca Cola, one of the soccer body’s longest-standing corporate sponsors, alongside Delta Airlines and Home Depot adopted political positions in their condemnation of the Georgia law.

The greater assertiveness of athletes and corporations in speaking out for fundamental rights and against racism and discrimination will make it increasingly difficult for sports associations to uphold the fiction of a separation between politics and sports.

The willingness of FIFA, the US Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) and other national and international associations to look the other way when athletes take their support for rights and social justice to the sports arena has let a genie out of the bottle. It has sawed off the legs of the FIFA principle that players’ “equipment must not have any political, religious or personal slogans.”

Already, the US committee has said that it would not sanction American athletes who choose to raise their fists or kneel on the podium at this July’s Tokyo Olympic Games as well as future tournaments.

The decision puts the USOPC at odds with the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) staunch rule against political protest.

The IOC suspended and banned US medallists Tommie Smith and John Carlos after the sprinters raised their fists on the podium at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics to protest racial inequality in the United States.

Acknowledging the incestuous relationship between sports and politics will ultimately require a charter or code of conduct that regulates the relationship and introduces some form of independent oversight akin to the supervision of banking systems or the regulation of the water sector in Britain, alongside the United States the only country to have privatized water as an asset.

Human rights and social justice have emerged as monkey wrenches that could shatter the myth of a separation of sports and politics. If athletes take their protests to the Tokyo Olympics and the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, the myth would sustain a significant body blow.

Said a statement by US athletes seeking changes to the USOPC’s rule banning protest at sporting events: “Prohibiting athletes to freely express their views during the Games, particularly those from historically underrepresented and minoritized groups, contributes to the dehumanization of athletes that is at odds with key Olympic and Paralympic values.”

A podcast version of this story is available on Soundcloud, Itunes, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, Spreaker, Pocket Casts, Tumblr, Podbean, Audecibel, Castbox, and Patreon.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute as well as an Honorary Senior Non-Resident Fellow at Eye on ISIS.

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Sports governance worldwide has had the legs knocked out from under it. Yet, national and international sports administrators are slow in realizing the magnitude of what has hit them.

#Sports#soccer#football#baseball#human rights#racism#Protest#United States#qatar#FIFA World Cup 2022#bahrain#f1

1 note

·

View note

Audio

Former Crown Prince Hamzah bin Hussein has papered over a rare public dispute in the ruling Jordanian family in a move that is unlikely to resolve long-standing fissures in society and among the country’s elite and that echo multiple Middle Eastern fault lines.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jordan is where domestic and regional fissures collide

By James M. Dorsey

Former Crown Prince Hamzah bin Hussein has papered over a rare public dispute in the ruling Jordanian family in a move that is unlikely to resolve long-standing fissures in society and among the country’s elite and that echo multiple Middle Eastern fault lines.

Differences over socio-economic policies, governance, and last year’s normalization of relations between Israel, the United Arab Emirates and three other Arab states as well as leadership of the Muslim world were laid glaringly bare by a security crackdown that targeted not only Prince Hamzah, a popular, modest, and pious 41-year-old half-brother of King Abdullah, but also seemingly unrelated others perceived by the monarch as a threat.

Reading tea leaves, the perceived threats may be twofold albeit unrelated: Prince Hamzah’s association with powerful conservative tribes who over the last decade have demanded an end to corruption and prominent figures with close ties to Saudi Arabia.

The kingdom, home to Islam’s two holiest cities, Mecca and Medina, has been quietly manoeuvring to force Jordan, the administrator of the faith’s third holiest site, Al-Haram ash-Sharif or Temple Mount in Jerusalem, to share its role. A say in Jerusalem would significantly boost the kingdom’s claim to leadership of the Muslim world.

There is little evidence that the two forces were working together despite government assertions that it had intercepted communications between the two in the days prior to this weekend’s crackdown that prompted Prince Hamzah to speak out.

Prince Hamzah’s statement focused on domestic issues, suggesting that the government may have been most immediately concerned that he was fuelling further protests particularly on the eve of Jordan’s April 11 centenary. The concern may have created the opportunity to address perceived less imminent threats.

The crackdown led to the arrest of among others two prominent leaders of the Al-Majali tribe and political clan, long a pillar of Hashemite rule, and Bassem Awadallah, a former top aide to King Abdullah, finance minister and envoy to Saudi Arabia, who is also an advisor to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Mr. Awadallah is a dual Jordanian-Saudi citizen.

The Washington Post reported that Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan had requested during a visit to Amman on Tuesday that Mr. Awadallah be released and allowed to travel to the kingdom with his delegation.

Privately, many Jordanians fear that Saudi Arabia could support efforts to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by turning the kingdom into a Palestinian state that would incorporate those parts of the occupied West Bank that would not be annexed by Israel.

Saudi Arabia has so far refused to establish diplomatic relations with Israel as long as the Palestinian issue has not been resolved. Mr. Bin Farhan reiterated the kingdom’s position earlier this month but also told CNN that relations with Israel would be "extremely helpful" and bring "tremendous benefits."

Relations between Saudi Arabia and Jordan, hard hit by the pandemic and home to one of the world’s largest Syrian refugee contingents, were strained by King Abdullah’s refusal to embrace former US President Donald J. Trump’s Deal of the Century Israeli-Palestinian peace plan.

King Abdullah opposed the plan because it recognized Israeli annexation of East Jerusalem, legitimized Israeli settlements in occupied territory and envisioned Israeli annexation of parts of the West Bank.

Saudi Arabia this weekend, like other Middle Eastern countries, was quick to express support for King Abdullah.

Prince Hamzah and Mr. Awadallah were not known to be close. Tribal leaders rejected Mr. Awadallah’s privatization of telecommunications, potash and phosphate companies during his tenure as finance minister as primarily benefitting the country’s allegedly corrupt elite and foreign companies.

Prince Hamzah, in an agreement mediated by the former crown prince’s uncle, Prince Hassan bin Talal, and several other princes, pledged allegiance to King Abdullah days after releasing two clips in which he denounced corruption and poor governance that had allegedly prevailed for much of the monarch’s rule. King Abdullah acceded to the throne in 1999.

The agreement takes the immediate sting out of the rare public airing of differences within the ruling family but fails to tackle grievances of the tribes and other segments of the population.

Prince Hamzah’s declaration of fealty may be less of a concession than it would appear at first glance. The former crown prince is not believed to aspire to succeeding King Abdullah.

Moreover, protests going back to the time of the 2011 popular Arab revolts and continuing more recently with the tribal-backed Hirak protest movement, have consistently stopped short of demanding regime change.

Tribal leaders went perhaps furthest when in 2011 they issued a statement asserting corruption among members of Kuwait-born Queen Rania’s Palestinian family and demanded that King Abdullah divorce his wife.

In the government’s statement on Sunday, Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi studiously avoided speaking of an attempted coup, asserting instead that the former crown prince and others had targeted “the country’s security and stability.”

Said a tribal activist: “Our issue is not the king or the family. Nobody is asking for regime change. That does not mean that our leaders have a blank check. They have to introduce real change and accommodate popular demands for transparency and accountable governance.”

A podcast version of this story is available on Soundcloud, Itunes, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, Spreaker, Pocket Casts, Tumblr, Podbean, Audecibel, Castbox, and Patreon.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute as well as an Honorary Senior Non-Resident Fellow at Eye on ISIS.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle for the Soul of Islam

By James M. Dorsey

This story was first published in Horizons

TROUBLE is brewing in the backyard of Muslim-majority states competing for religious soft power and leadership of the Muslim world in what amounts to a battle for the soul of Islam. Shifting youth attitudes towards religion and religiosity threaten to undermine the rival efforts of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran and, to a lesser degree, the United Arab Emirates, to cement their individual state-controlled interpretations of Islam as the Muslim world’s dominant religious narrative. Each of the rivals see their efforts as key to securing their autocratic or authoritarian rule as well as advancing their endeavors to carve out a place for themselves in a new world order in which power is being rebalanced.

Research and opinion polls consistently show that the gap between the religious aspirations of youth—and, in the case of Iran other age groups—and state-imposed interpretations of Islam is widening. The shifting attitudes amount to a rejection of Ash’arism, the fundament of centuries-long religiously legitimized authoritarian rule in the Sunni Muslim world that stresses the role of scriptural and clerical authority. Mustafa Akyol, a prominent Turkish Muslim intellectual, argues that Ash’arism has dominated Muslim politics for centuries at the expense of more liberal strands of the faith “not because of its merits, but because of the support of the states that ruled the medieval Muslim world.”

Similarly, Nadia Oweidat, a student of the history of Islamic thought, notes that “no topic has impacted the region more profoundly than religion. It has changed the geography of the region, it has changed its language, it has changed its culture. It has been shaping the region for thousands of years. [...] Religion controls every aspect of people who live in the Arab world.”

The polls and research suggest that youth are increasingly skeptical towards religious and worldly authority. They aspire to more individual, more spiritual experiences of religion. Their search leads them in multiple directions that range from changes in personal religious behavior that deviates from that proscribed by the state to conversions in secret to other religions even though apostasy is banned and punishable by death, to an abandonment of organized religion all together in favor of deism, agnosticism, or atheism.

“The youth are not interested in institutions or organizations. These do not attract them or give them any incentive; just the opposite, these institutions and organizations and their leadership take advantage of them only when they are needed for their attendance and for filling out the crowds,” said Palestinian scholar and former Hamas education minister Nasser al-Din al-Shaer.

Atheists and converts cite perceived discriminatory provisions in Islam’s legal code towards various Muslim sects, non-Muslims, and women as a reason for turning their back on the faith. “The primary thing that led me to atheism is Islam’s moral aspect. How can, for example, a merciful and compassionate God, said to be more merciful than a woman on her baby, permit slavery and the trade of slaves in slave markets? How come He permits rape of women simply because they are war prisoners? These acts would not be committed by a merciful human being much less by a merciful God,” said Hicham Nostic, a Moroccan atheist, writing under a pen name.

Revival, Reversal

The recent research and polls suggest a reversal of an Islamic revival that scholars like John Esposito in the 1990s and Jean-Paul Carvalho in 2009 observed that was bolstered by the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, the results of a 1996 World Values Survey that reported a strengthening of traditional religious values in the Muslim world, the rise of Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and the initial Muslim Brotherhood electoral victories in Egypt and Tunisia in the wake of the 2011 popular Arab revolts.

“The indices of Islamic reawakening in personal life are many: increased attention to religious observances (mosque attendance, prayer, fasting), proliferation of religious programming and publications, more emphasis on Islamic dress and values, the revitalization of Sufism (mysticism). This broader-based renewal has also been accompanied by Islam’s reassertion in public life: an increase in Islamically oriented governments, organizations, laws, banks, social welfare services, and educational institutions,” Esposito noted at the time.

Carvalho argued that an economic “growth reversal which raised aspirations and led subsequently to a decline in social mobility which left aspirations unfulfilled among the educated middle class (and) increasing income inequality and impoverishment of the lower-middle class” was driving the revival. The same factors currently fuel a shift away from traditional, Orthodox, and ultra-conservative values and norms of religiosity.

The shift in Muslim-majority countries also contrasts starkly with a trend towards greater religious Orthodoxy in some Muslim minority communities in Europe. A 2018 report by the Dutch government’s Social and Cultural Planning Bureau noted that the number of Muslims of Turkish and Moroccan descent who strictly observe traditional religious precepts had increased by approximately eight percent. Dutch citizens of Turkish and Moroccan descent account for two-thirds of the country’s Muslim community. The report suggested that in a pluralistic society in which Muslims are a minority, “the more personal, individualistic search for true Islam can lead to youth becoming more strict in observance than their parents or environment ever were.”

Changing attitudes towards religion and religiosity that mirror shifting attitudes in non-Muslim countries are particularly risky for leaders, irrespective of their politics, who cloak themselves in the mantle of religion as well as nationalism and seek to leverage that in their geopolitical pursuit of religious soft power. The 2011 popular Arab revolts as well as mass anti-government protests in various Middle Eastern countries in 2019 and 2020 spotlighted the subversiveness of the change. “The Arab Spring was the tipping point in the shift [...]. It was the epitome of how we see the change. The calls were for ‘dawla madiniya,’ a civic state. A civic state is as close as you can come to saying [...], we want a state where the laws are written by people so that we can challenge them, we can change them, we can adjust them. It’s not God’s law, it’s madiniya, it’s people’s law,” Oweidat, the Islamic thought scholar, said.

Akyol went further, noting in a journal article that “too many terrible things have recently happened in the Arab world in the name of Islam. These include the sectarian civil wars in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen, where most of the belligerents have fought in the name of God, often with appalling brutality. The millions of victims and bystanders of these wars have experienced shock and disillusionment with religious politics, and more than a few began asking deeper questions.”

The 2011 popular Arab revolts reverberated across the Middle East, reshaping relations between states as well as domestic policies, even though initial achievements of the protesters were rolled back in Egypt and sparked wars in Libya, Yemen, and Syria.

Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt imposed a 3.5 year-long diplomatic and economic boycott of Qatar in part to cut their youth off from access to the Gulf state’s popular Al Jazeera television network that supported the revolts and Islamist groups that challenged the region’s autocratic rulers. Seeking to lead and tightly control a social and economic reform agenda driven by youth who were enamored by the uprisings, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman “sought to recapture this mandate of change, wrap it in a national mantle, and sever it from its Arab Spring associations. The boycott and ensuing nationalist campaign against Qatar became central to achieving that,” said Gulf scholar Kristin Smith Diwan.

Referring to the revolts, Moroccan journalist Ahmed Benchemsi suggested that “the Arab Spring may have stalled, if not receded, but when it comes to religious beliefs and attitudes, a generational dynamic is at play. Large numbers of individuals are tilting away from the rote religiosity Westerners reflexively associate with the Arab world.”

Benchemsi went on to argue that “in today’s Arab world, it’s not religiosity that is mandatory; it’s the appearance of it. Nonreligious attitudes and beliefs are tolerated as long as they’re not conspicuous. As a system, social hypocrisy provides breathing room to secular lifestyles, while preserving the façade of religion. Atheism, per se, is not the problem. Claiming it out loud is. So those who publicize their atheism in the Arab world are fighting less for freedom of conscience than for freedom of speech.” The same could be said for the right to convert or opt for alternative practices of Islam.

Syrian journalist Sham al-Ali recounts the story of a female relative who escaped the civil war to Germany where she decided to remove her hijab. Her father, who lives in Turkey, accepted his daughter’s decision but threatened to disown her if she posted pictures of herself uncovered on Facebook. “His issue was not with his daughter’s abandonment of religious duty, but with her publicizing that before her family and society at large,” Al-Ali said.

Neo-patriarchism

Neo-patriarchism, a pillar of Arab autocratic rule, heightens concern about public appearance and perception. A phrase coined by American-Palestinian scholar Hisham Sharabi, neo-patriarchism involves projection of the autocratic leader as a father figure. Autocratic Arab society, according to Sharabi, was built on the dominance of the father, a patriarch around which the national as well as the nuclear family are organized. Relations between a ruler and the ruled are replicated in the relationship between a father and his children. In both settings, the paternal will is absolute, mediated in society as well as the family by a forced consensus based on ritual and coercion.

As a result, neo-patriarchism often reinforces pressure to abide by state-imposed religious behavior and at the same time fuels changes in attitudes towards religion and religiosity among youth who resent their inability to chart a path of their own. Primary and secondary schools have emerged as one frontline in the struggle to determine the boundaries of religious expression and behavior. Recent developments in Egypt, a brutal autocracy, and Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority democracy, offer contrasting perspectives on how the tug of war between students and parents, schoolteachers and administrations, and the state plays out.

Mada Masr, Egypt’s foremost independent news outlet, documented how in 2020 Egyptian schoolgirls who refused to wear a hijab were being coerced and publicly shamed in the knowledge that the education ministry was reluctant to enforce its policy not to mandate the wearing of a headdress. “The model, decent girl is expected to dress modestly and wear a hijab to signal her pride in her religious identity, since hijab is what distinguishes her from a Christian girl,” said Lamia Lotfy, a gender consultant and rights activist. Teachers at public high schools said they were reluctant to take boys to task for violating dress codes because they were more likely to push back and create problems.

In sharp contrast, Indonesian Religious Affairs Minister Yaqut Cholil Qoumas issued in early 2021 a decree together with the ministers of home affairs and education threatening to sanction state schools that seek to impose religious garb in violation of government rules and regulations. The decree was issued amid a public row sparked by the refusal of a Christian student to obey her school principal’s instructions requiring all pupils to wear Islamic clothing. Qoumas is a leader of Nahdlatul Ulama, the world’s largest Muslim movement and foremost advocate of theological reform in line with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “Religions do not promote conflict, neither do they justify acting unfairly against those who are different,” Qoumas said.

A Muslim nation that replaced a decades long autocratic regime with a democracy in a popular revolt in 1998, Indonesia is Middle Eastern rulers’ worst nightmare. The shifting attitudes of Middle Eastern youth towards religion and religiosity suggest that experimentation with religion in post-revolt Indonesia is a path that it would embark on if given the opportunity. Indonesia is “where the removal of constraints imposed by an authoritarian regime has opened up the imaginative terrain, allowing particular types of religious beliefs and practices to emerge [...]. The Indonesian cases study [...] brings into sharper relief processes that are happening in ordinary Muslim life elsewhere,” said Indonesia scholar Nur Amali Ibrahim.

A 2019 poll of Arab youth showed that two-thirds of those surveyed felt that religion played too large a role in their lives, up from 50 percent four years earlier. Nearly 80 percent argued that religious institutions needed to be reformed while half said that religious values were holding the Arab world back. Surveys conducted over the last decade by Arab Barometer, a research network at Princeton University and the University of Michigan, showed a growing number of youths turning their backs on religion. “Personal piety has declined some 43 percent over the past decade, indicating less than a quarter of the population now define themselves as religious,” the survey concluded.

With the trend being the strongest among Libyans, many Libyan youth gravitate towards secretive atheist Facebook pages. They often are products of the UAE’s failed attempt to align the hard power of its military intervention in Libya with religious soft power. Said, a 25-year-old student from Benghazi, the stronghold of the UAE and Saudi-backed rebel forces led by self-appointed Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, turned his back on religion after his cousin was beheaded in 2016 for speaking out against militants. UAE backing of Haftar has involved the population of his army by Madkhalists, a branch of Salafism named after a Saudi scholar who preaches absolute obedience to the ruler and projects the kingdom as a model of Islamic governance. “My cousin’s death occurred during a period when I was deeply religious, praying five times a day and studying ten new pages of the Qur’an each evening,” Said said.

A majority of respondents in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, and Iran said in a 2017 poll conducted by Washington-based John Zogby Associates that they wanted religious movements to focus on personal faith and spiritual guidance and not involve themselves in politics. Iraq and Palestine were the outliers with a majority favoring a political role for religious groups.

The response to polls in the second half of the second decade of the twenty-first century contrasts starkly with attitudes expressed in a survey of the world’s Muslims by the Pew Research Center several years earlier. Pew’s polling suggested that ultra-conservative attitudes long promoted by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar that legitimized authoritarian and autocratic regimes remained popular. More than 70 percent of those surveyed at the time in South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa favored making Sharia the law of the land and granting Sharia courts jurisdiction over family law and property disputes.

Those numbers varied broadly, however, when respondents were asked about specific issues like apostasy and corporal punishment. Three-quarters of South Asians favored the death sentence for apostasy as opposed to 56 percent in the Middle East and only 27 percent in Southeast Asia, while 81 percent in South Asia supported physical punishment compared to 57 percent in the Middle East and North Africa and 46 percent in Southeast Asia. South Asia emerged as the only part of the Muslim world in which respondents preferred a strong leader to democracy while a majority of the faithful in all three regions viewed religious freedom as positive. Between 65 and 79 percent in all regions wanted to see religious leaders have political influence.

Honor killings may be the one area where attitudes have not changed that much in recent years. Arab Barometer’s polling in 2018 and 2019 showed that more people thought honor killings were acceptable than homosexuality. In most countries polled, young Arabs appeared more likely than their parents to condone honor killings. Social media and occasional protests bear that out. Thousands rallied in early 2020 in Hebron, a conservative city on the West Bank, after the Palestinian Authority signed the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

Nonetheless, the assertions by Saudi Arabia that projects itself as the leader of an unidentified form of moderate Islam that preaches absolute obedience to the ruler and by advocates of varying strands of political Islam such as Turkey and Iran ring hollow in light of the dramatic shift in attitudes towards religion and religiosity.

Acknowledging Change

Among the Middle Eastern rivals for religious soft power, the United Arab Emirates, populated in majority by non-nationals, may be the only one to emerge with a cleaner slate. The UAE is the only contender to have started acknowledging changing attitudes and demographic realities. Authorities in November 2020 lifted the ban on consumption of alcohol and cohabitation among unmarried couples. In a further effort to reach out to youth, the UAE organized in 2021 a virtual consultation with 3,000 students aimed at motivating them to think innovatively over the country’s path in the next 50 years.

Such moves do not fundamentally eliminate the risk that the changing attitudes may undercut the religious soft power efforts of the UAE and its Middle Eastern competitors. The problem for rulers like the UAE and Saudi crown princes, Mohammed bin Zayed and Mohammed bin Salman, respectively, is that the loosening of social restrictions in Saudi Arabia—including the emasculation of the kingdom’s religious police, the lifting of a ban on women’s driving, less strict implementation of gender segregation, the introduction of Western-style entertainment and greater professional opportunities for women, and a degree of genuine religious tolerance and pluralism in the UAE—are only first steps in responding to youth aspirations.

“People are sick and tired of organized religion and being told what to do. That is true for all Gulf states and the rest of the Arab world,” quipped a Saudi businessman. Social scientist Ellen van de Bovenkamp describes Moroccans she interviewed for her PhD thesis as living “a personalized, self-made religiosity, in which ethics and politics are more important than rituals.”

Nevertheless, religious authorities in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Turkey, Qatar, Iran, and Morocco continue to project interpretations of the faith that serve the state and are often framed in the language of tolerance and inter-faith dialogue but preserve outmoded legal categories, traditions, and scripture that date back centuries. Outdated concepts of slavery, who is a believer and who is an infidel, apostasy, blasphemy, and physical punishment that need reconceptualization remain in terms of religious law frozen in time. Many of those concepts, with the exception of slavery that has been banned in national law yet remains part of Islamic law, have been embedded in national legislations.

While Turkey continues to, at least nominally, adhere to its secular republican origins, it is no different from its rivals when it comes to grooming state-aligned clergymen, whose ability to think out of the box and develop new interpretations of the faith is impeded by a religious education system that stymies critical thinking and creativity. Instead, it too emphasizes the study of Arabic and memorization of the Qur’an and other religious texts and creates a religious and political establishment that discourages, if not penalizes, innovation.

Widening the gap between state projections of religion and popular aspirations is the fact that governments’ subjugation of religious establishments turns clerics and scholars into regime parrots and fuels youth skepticism towards religious institutions and leaders.

“Youth have [...] witnessed how religious figures, who still remain influential in many Arab societies, can sometimes give in to change even if they have resisted it initially. This not only feeds into Arab youth’s skepticism towards religious institutions but also further highlights the inconsistency of the religious discourse and its inability to provide timely explanations or justifications to the changing reality of today,” said Gulf scholar Eman Alhussein in a commentary on the 2020 Arab Youth Survey.

Pooyan Tamimi Arab, the co-organizer of an online survey in 2020 of Iranian attitudes towards religion that revealed a stunning rejection of state-imposed adherence to conservative religious mores as well as the role of religion in public life noted the widening gap “becomes an existential question. The state wants you to be something that you don’t want to be [...]. “Political disappointment steadily turned into religious disappointment [...]. Iranians have turned away from institutional religion on an unprecedented scale.”

In a similar vein, Turkish art historian Nese Yildiran recently warned that a fatwa issued by President Erdogan’s Directorate of Religious Affairs or Diyanet declaring popular talismans to ward off “the evil eye” as forbidden by Islam fueled criticism of one of the best-funded branches of government. The fatwa followed the issuance of similar religious opinions banning the dying of men’s moustaches and beards, feeding dogs at home, tattoos, and playing the national lottery as well as statements that were perceived to condone or belittle child abuse and violence against women.

Although compatible with a trend across the Middle East, the Iranian survey’s results, which is based on 50,000 respondents who overwhelmingly said they resided in the Islamic republic, suggested that Iranians were in the frontlines of the region’s quest for religious change.

Funded by Washington-based Iranian human rights activist Ladan Boroumand, the Iranian survey, coupled with other research and opinion polls across the Middle East and North Africa, suggests that not only Muslim youth, but also other age groups, who are increasingly skeptical towards religious and worldly authority, aspire to more individual, more spiritual experiences of religion.

Their quest runs the gamut from changes in personal religious behavior to conversions in secret to other religions because apostasy is banned and, in some cases, punishable by death, to an abandonment of religion in favor of agnosticism or atheism. Responding to the survey, 80 percent of the participants said they believed in God but only 32.2 percent identified themselves as Shiite Muslims—a far lower percentage than asserted in official figures of predominantly Shiite Iran.

More than one third of the respondents said that they either did not belong to a religion or were atheists or agnostics. Between 43 and 53 percent, depending on age group, suggested that their religious views had changed over time with 6 percent of those saying that they had converted to another religious orientation.

In addition, 68 percent said they opposed the inclusion of religious precepts in national legislation. Moreover 70 percent rejected public funding of religious institutions while 56 percent opposed mandatory religious education in schools. Almost 60 percent admitted that they do not pray, and 72 percent disagreed with women being obliged to wear a hijab in public.

An unpublished slide of the survey shows the change in religiosity reflected in the fact that an increasing number of Iranians no longer name their children after religious figures.

A five-minute YouTube clip uploaded by an ultra-conservative channel allegedly related to Iran’s Revolutionary Guards attacked the survey despite having distributed the questionnaire once the pollsters disclosed in their report that the poll had been supported by an exile human rights group.

“Tehran may well be the least religious capital in the Middle East. Clerics dominate the news headlines and play the communal elders in soap operas, but I never saw them on the street, except on billboards. Unlike most Muslim countries, the call to prayer is almost inaudible [...]. Alcohol is banned but home delivery is faster for wine than for pizza [...]. Religion felt frustratingly hard to locate and the truly religious seemed sidelined, like a minority,” wrote journalist Nicholas Pelham based on a visit in 2019 during which he was detained for several weeks.

In yet another sign of rejection of state-imposed expressions of Islam, Iranians have sought to alleviate the social impact of COVID-19 related lockdowns and restrictions on face-to-face human contact by acquiring dogs, cats, birds, and even reptiles as pets. The Islamic Republic has long viewed pets as a fixture of Western culture. One of the main reasons for keeping pets in Iran is that people no longer believe in the old cultural, religious, or doctrinal taboos as the unalterable words of God. “This shift towards deconstructing old taboos signals a transformation of the Iranian identity—from the traditional to the new,” said psychologist Farnoush Khaledi.

Pets are one form of dissent; clandestine conversions are another. Exiled Iranian Shiite scholar Yaser Mirdamadi noted that “Iranians no longer have faith in state-imposed religion and are groping for religious alternatives.”

A former Israeli army intelligence chief, retired Lt. Col. Marco Moreno, puts the number of converts in Iran, a country of 83 million, at about one million. Moreno’s estimate may be an overestimate. Other studies in put the figure at between 100,000 and 500,000. Whatever the number is, the conversions fit a trend not only in Iran but across the Muslim world of changing attitudes towards religion, a rejection of state-imposed interpretations of Islam, and a search for more individual and varied religious experiences. Iranian press reports about the discovery of clandestine church gatherings in homes in the holy city of Qom suggest conversions to Christianity began more than a decade ago. “The fact that conversions had reached Qom was an indication that this was happening elsewhere in the country,” Mirdamadi, the Shiite cleric, said.

Seeing the converts as an Israeli asset, Moreno backed production of a two-hour documentary, Sheep Among Wolves Volume II, produced by two American Evangelists, one of which resettled on the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, that asserts that Iran’s underground community of converts to Christianity is the world’s fastest growing church.

“What if I told you the mosques are empty inside Iran?” said a church leader in the film, his identity masked and his voice distorted to avoid identification. Based on interviews with Iranian converts while they were travelling abroad, the documentary opens with a scene on an Indonesian beach where they meet with the filmmakers for a religious training session.

“What if I told you that Islam is dead? What if I told you that the mosques are empty inside Iran? [...] What if I told you no one follows Islam inside of Iran? Would you believe me? This is exactly what is happening inside of Iran. God is moving powerfully inside of Iran?” the church leader added. Unsurprisingly, given the film’s Israeli backing and the filmmaker’s affinity with Israel, the documentary emphasizes the converts’ break with Iran’s staunch rejection of the Jewish State by emphasizing their empathy for Judaism and Israel.

Reduced Religiosity

The Iran survey’s results as well as observations by analysts and journalists like Pelham stroke with responses to various polls of Arab public opinion in recent years and fit a global pattern of reduced religiosity. A 2019 Pew Research Center study concluded that adherence to Christianity in the United States was declining at a rapid pace.

The Arab Youth Survey found that, despite 40 percent of those polled defining religion as the most important constituent element of their identity, 66 percent saw a need for religious institutions to be reformed. “The way some Arab countries consume religion in the political discourse, which is further amplified on social media, is no longer deceptive to the youth who can now see through it,” Alhussein, the Gulf scholar, said.

A 2018 Arab Opinion Index poll suggested that public opinion may support the reconceptualization of Muslim jurisprudence. Almost 70 percent of those polled agreed that “no religious authority is entitled to declare followers of other religions to be infidels.” Similarly, 70 percent of those surveyed rejected the notion that democracy was incompatible with Islam while 76 percent viewed it as the most appropriate system of governance.

What that means in practice is, however, less clear. Arab public opinion appears split down the middle when it comes to issues like separation of religion and politics or the right to protest.

Arab Barometer director Michael Robbins cautioned in a commentary in the Washington Post, co-authored with international affairs scholar Lawrence Rubin, that recent moves by the government of Sudan to separate religion and state may not enjoy public support.

The transitional government brought to office in 2020 by a popular revolt that topped decades of Islamist rule by ousted President Omar al-Bashir agreed in peace talks with Sudanese rebel groups to a “separation of religion and state.” The government also ended the ban on apostasy and consumption of alcohol by non-Muslims and prohibited corporal punishment, including public flogging.

Robbins and Rubin noted that 61 percent of those surveyed on the eve of the revolt believed that Sudanese law should be based on the Sharia or Islamic law defined by two-thirds of the respondents as ensuring the provision of basic services and lack of corruption. The researchers, nonetheless, also concluded that youth favored a reduced role of religious leaders in political life. They said youth had soured on the idea of religion-based governance because of widespread corruption during the region of Al-Bashir who professed his adherence to religious principles.

“If the transitional government can deliver on providing basic services to the country’s citizens and tackling corruption, the formal shift away from Sharia is likely to be acceptable in the eyes of the public. However, if these problems remain, a new set of religious leaders may be able to galvanize a movement aimed at reinstituting Sharia as a means to achieve these objectives,” Robbins and Rubin warned.

Writing at the outset of the popular revolt that toppled Al-Bashir, Islam scholar and former Sudanese diplomat Abdelwahab El-Affendi noted that “for most Sudanese, Islamism came to signify corruption, hypocrisy, cruelty, and bad faith. Sudan is perhaps the first genuinely anti-Islamist country in popular terms. But being anti-Islamist in Sudan does not mean being secular.”

It is a warning that is as valid for Sudan as it is for much of the Arab and Muslim world.

Saudi columnist Wafa al-Rashid sparked fiery debate on social media after calling in a local newspaper for a secular state in the kingdom. “How long will we continue to shy away from enlightenment and change? Religious enlightenment, which is in line with reality and the thinking of youth, who rebelled and withdrew from us because we are no longer like them. [...] We no longer speak their language or understand their dreams,” Al-Rashid wrote.

Asked in a poll conducted by The Washington Institute of Near East Policy whether “it’s a good thing we aren’t having big street demonstrations here now the way they do in some other countries”—a reference to the past decade of popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Algeria, Lebanon, Iraq and Sudan—Saudi public opinion was split down the middle. The numbers indicate that 48 percent of respondents agreed and 48 percent disagreed. Saudis, like most Gulf Arabs, are likely less inclined to take grievances to the streets. Nonetheless, the poll indicates that they may prove to be more empathetic to protests should they occur.

Tamimi Arab, the Iran pollster, argued that his Iran survey “shows that there is a social basis” for concern among authoritarian and autocratic governments that employ religion to further their geopolitical goals and seek to maintain their grip on potentially restive populations. His warning reverberates in the responses by governments in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere in the Middle East to changing attitudes towards religion and religiosity. They demonstrate the degree to which they perceive the change as a threat, often expressed in existential terms.

Mohammad Mehdi Mirbaqeri, a prominent Shiite cleric and member of Iran’s powerful Assembly of Experts that appoints the country’s supreme leader, described COVID-19 in late 2020 as a “secular virus” and a declaration of war on “religious civilization” and “religious institutions.”

Saudi Arabia went further by defining the “calling for atheist thought in any form” as terrorism in its anti-terrorism law. Saudi dissident and activist Rafi Badawi was sentenced on charges of apostasy to ten years in prison and 1,000 lashes for questioning why Saudis should be obliged to adhere to Islam and asserting that the faith did not have answers to all questions.

Analysts, writers, journalists, and pollsters have traced changes in attitudes in the Middle East and North Africa as well as the wider Muslim world for much of the past decade, if not longer. A Western Bangladesh scholar resident in Dacca in 1989 recalled Bangladeshis looking for a copy of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses as soon as it was banned by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, who condemned the British author to death. “It was the allure of forbidden fruit. Yet, I also found that many were looking for things to criticize, an excuse to think differently,” the scholar wrote.

Widely viewed as a bastion of ultra-conservatism. Malaysia’s top religious regulatory body, the Malaysian Islamic Development Department (Jakim), which responsible for training Islamic teachers and preparing weekly state-controlled Friday sermons, has long portrayed liberalism and pluralism as threats, pointing to a national fatwa that in 2006 condemned liberalism as heretical. “The pulpit would like to state today that many tactics are being undertaken by irresponsible people to weaken Muslim unity, among them through spreading new but inverse thinking like Pluralism, Liberalism, and such. The pulpit would like to state that the Liberal movement contains concepts that are found to have deviated from the Islamic faith and shariah,” read a 2014 Friday sermon drafted and distributed by Jakim.

The fatwa echoed a similar legal opinion issued a year earlier by Indonesia’s semi-governmental Council of Religious Scholars (MUI) labelled with SIPILIS as its acronym to equate secularism, pluralism, and liberalism with the venereal disease. The council was headed at the time by current Vice President Ma’ruf Amin, a prominent Nahdlatul Ulama figure.

Challenging attempts by governments and religious authorities to suppress changing attitudes rather than engage with groups groping for greater religious freedom, Kuwaiti writer Sajed al-Abdali noted in 2012 that “it is essential that we acknowledge today that atheism exists and is increasing in our society, especially among our youth, and evidence of this is in no short supply.”

Al-Abdali sounded his alarm three years prior to the publication of a Pew Research Center study that sought to predict the growth trajectories of the world’s religions by the year 2050. The study suggested that the number of people among the 300 million inhabitants of the Middle East and North Africa that were unaffiliated with any faith would remain stable at about 0.6 percent of the population.

Two years later, the Egyptian government’s religious advisory body, Dar al-Ifta Al-Missriya, published a scientifically disputed survey that sought to project the number of atheists in the region as negligible. The survey identified 2,293 atheists, including 866 Egyptians, 325 Moroccans, 320 Tunisians, 242 Iraqis, 178 Saudis, 170 Jordanians, 70 Sudanese, 56 Syrians, 34 Libyans, and 32 Yemenis. It defined atheists as not only those who did not believe in God but also as encompassing converts to other religions and advocates of a secular state. A poll conducted that same year by Al Azhar, Cairo’s ancient citadel of Islamic learning, concluded that Egypt counted 10.7 million atheists. Al Azhar’s Grand Imam, Ahmad al-Tayyeb, warned at the time on state television that the flight from religion constituted a social problem.

A 2012 survey by international polling firm WIN/Gallup International reported that 5 percent of Saudis—or more than one million people—identified themselves as “convinced atheists” on par with the percentage in the United States; while 19 percent described themselves as non-religious. By the same token, Benchemsi, the Moroccan journalist, found 250 Arab atheism-related pages or groups while searching the internet, with memberships ranging from a few individuals to more than 11,000. “And these numbers only pertain to Arab atheists (or Arabs concerned with the topic of atheism) who are committed enough to leave a trace online,” Benchemsi said, noting that many more were unlikely to publicly disclose their beliefs.

The picture is replicated across the Middle East. The number of atheists and agnostics in Iraq, for example, is growing. Iraqi writer and one-time Shiite cleric Gaith al-Tamimi argued that religious figures have come to represent all that’s inherently wrong in Iraqi politics society. Iraqis of all generations seek to escape religious dogma, he says, adding that “Iraqis are questioning the role religion serves today.” Fadhil, a 30-year-old from the southern port city of Basra complained that religious leaders “overuse and misuse God’s name, police human bodies, prohibit extramarital sex, and police the bodies of women.” Changing attitudes towards religion figured prominently in mass anti-government protests in Iraq in 2019 and 2020 that rejected sectarianism and called for a secular national Iraqi identity.

Even in Syria, a fulcrum of militant and ultra-conservative forms of Islam that fed on a decade of brutal civil war and foreign intervention, many concluded in the words of Al-Ali, the Syrian journalist, that “religious and political authorities are ‘protective friends one of the other,’ and that political despotism stems from religious absolutism. [...] In Syria, the prestige sheikhs had enjoyed was undermined alongside that of the regime.” Religion and religious figures’ inability to explain the horror that Syria was experiencing and that had uprooted the lives of millions drove many forced to flee to question long-held beliefs.

Multiple Turkish surveys suggested that Erdogan’s goal of raising a religious generation had backfired despite pouring billions of dollars into religious education. Students often rejected religion, described themselves as atheists, deists, or feminists, and challenged the interpretation of Islam taught in schools. A 2019 survey by polling and data company IPSOS reported that only 12 percent of Turks trusted religious officials and 44 percent distrusted clerics. “We have declined when religious sincerity and morality expressed by the people is taken into account,” said Ali Bardakoglu, who headed Erdogan’s Religious Affairs Department or Diyanet from 2003 to 2010.

Unaware that microphones had not been muted, Erdogan expressed concern a year earlier to his education minister about the spread of deism, a belief in a God that does not intervene in the universe and that is not defined by organized religion, among Turkish youth during a meeting of his party’s parliamentary group. “No, no such thing can happen,” Erdogan ordained against the backdrop of Turkish officials painting deism as a Western conspiracy designed to weaken Turkey. Erdogan’s comments came in response to the publication of an education ministry report that, in line with the subsequent survey, warned that popular rejection of religious knowledge acquired through revelation and religious teachings and a growing embrace of reason was on the rise.

The report noted that increased enrollment in a rising number of state-run religious Imam Hatip high schools had not stopped mounting questioning of orthodox Islamic precepts. Neither had increased study of religion in mainstream schools that deemphasized the teaching of evolution. The greater emphasis on religion failed to advance Erdogan’s dream of a pious generation that would have a Qur’an in one hand and a computer in the other. Instead, reflecting a discussion on faith and youth among some 50 religion teachers, the report suggested that lack of faith in educators had fueled the rise of deism. Teachers were unable to answer the often-posed question: why does God not intervene to halt evil and why does he remain silent? The report’s cautionary note was bolstered by a flurry of anonymous confessions and personal stories by deists as well as atheists recounted in newspaper interviews.

Acting on Erdogan’s instructions, Ali Erbas, the director of Diyanet, declared war on deism. The government’s top cleric, Erbas blamed Western missionaries seeking to convert Turkish youth to Christianity for deism’s increased popularity. Erbas’ declaration followed a three-day consultation with 70 religious scholars and bureaucrats convened by the Directorate that identified “Deism, Atheism, Nihilism, Agnosticism” as the enemy. Erdogan’s alarm and Erbas’ spinning of conspiracy theories constituted attempts to detract attention from the fact that youth in Tukey, like in Iran and the Arab world, were turning their back on orthodox and classical interpretations of Islam on the back of increasingly authoritarian and autocratic rule. Erdogan thundered that “there is no such thing” as LGBT and added that “this country is national and spiritual, and will continue to walk into the future as such” when protesting students displayed a poster depicting one of Islam’s holiest sites, the Kaaba shrine in Mecca, with LGBT flags.

“There is a dictatorship in Turkey. This drives people away from religion,” said Temel Karamollaoglu, the leader of the Islamist Felicity Party that opposes Erdogan’s AKP because of its authoritarianism. Turkey scholar Mucahit Bilici described Turkish youths’ rejection of Orthodox and politicized interpretations of Islam as “a flowering of post-Islamist sentiment” by a “younger generation (that) is choosing the path of individualized spirituality and a silent rejection of tradition.”

Saudi authorities view the high numbers in the WIN/Gallup International as a threat to the religious legitimacy that the kingdom’s ruling Al-Saud family has long cloaked itself in. The groundswell of aspirations that have guided youth away from the confines of ultra-conservatism highlight failed efforts of the government and the religious establishment going back to the 1980s. The culture and information ministry banned the word ‘modernity’ at the time in a bid to squash an emerging debate that challenged the narrow confines of ultra-conservatism as well as the authority of religion and the religious establishment to govern personal and public life.

False Equation

The threat perceived by Saudi and other Middle Eastern autocrats and authoritarians as well as conservative religious voices is fueled by an implicit equation of atheism and/or rejection of state-imposed conservative and ultra-conservative strands of the faith with anarchy.

“Any calls that challenge Islamic rule or Islamic ideology is considered subversive in Saudi Arabia and would be subversive and could lead to chaos,” said Saudi ambassador to the United Nations Abdallah al-Mouallimi. Echoing journalist Benchemsi, Muallimi argued that “if (a person) was disbelieving in God, and keeping that to himself, and conducting himself, nobody would do anything or say anything about it. If he is going out in the public, and saying, ‘I don’t believe in God,’ that’s subversive. He is inviting others to retaliate.”

Similarly, Sheikh Ahmad Turki, speaking as the coordinator of the anti-atheism campaign of the Egyptian Ministry of Endowments, asserted that atheism “is a national security issue. Atheists have no principles; it’s certain that they have dysfunctional concepts—in ethics, views of the society and even in their nationalistic affiliations. If [atheists] rebel against religion, they will rebel against everything.’’

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have sought to experiment with alternatives to orthodox and ultra-conservative strands of Islam without surrendering state control by encouraging Al Azhar to embrace legal reform that is influenced by Sufism, Islam’s mystical tradition. “There is a movement of renewal of Islamic jurisprudence. [...] It’s a movement that is funded by the wealthy Gulf countries. Don’t forget that one reason for the success of the Salafis is the financial power that backed them for decades. This financial power is now being directed to the Azharis, and they are taking advantage of it. [...] Don’t underestimate what is happening. It might be a true alternative to Salafism,” said Egyptian Islam scholar Wael Farouq.

By contrast, Pakistan, a country influenced by Saudi-inspired ultra-conservatism, has stepped up its efforts to ringfence religious minorities. In an act of overreach modelled on American insistence on extra-territorial abidance by some of its laws, Pakistan laid down a gauntlet in the struggle to define religious freedom by seeking to block and shut down a U.S.-based website associated with Ahmadis on charges of blasphemy.

Ahmadis are a minority sect viewed as heretics by many Muslims that have been targeted in Indonesia and elsewhere, but nowhere more so than in Pakistan where they have been constitutionally classified as non-Muslims. Blasphemy is potentially punishable in Pakistan with a death sentence.

The Pakistani effort was launched at a moment that anti-Ahmadi and anti-Shiite sentiment in Pakistan, home to the world’s largest Shia Muslim minority, was on the rise. Mass demonstrations denounced Shiites as “blasphemers” and “infidels” and called for their beheading as the number of blasphemy cases being filed against Shiites in the courts mushroomed.

Shifting attitudes towards religion and religiosity raise fundamental chicken and egg questions about the relationship between religious and political reform, including what comes first and whether one is possible without the other. Indonesia’s Nahdlatul Ulama argues that religious reform requires recontextualization of the faith as well as a revision of legal codes and religious jurisprudence. The only Muslim institution to have initiated a process of eliminating legal concepts in Islamic law that are obsolete or discriminatory—such as the endorsement of slavery and notions of infidels and dhimmis or People of the Book with lesser rights—Nahdlatul Ulama, a movement created almost a century ago in opposition to Wahhabism, the puritan interpretation of Islam on which Saudi Arabia was founded, is in alignment with advocates of religious reform elsewhere in the Muslim world.

Said Mohammed Sharour, a Syrian Quranist who believed that the Qur’an was Islam’s only relevant text, dismissed the Hadith—the compilation of the Prophet’s sayings and the Sunnah, the traditions, and practices of the Prophet that serve as a model for Muslims: “The religious heritage must be critically read and interpreted anew. Cultural and religious reforms are more important than political ones, as they are the preconditions for any secular reforms.” Shahrour went on to say that the reforms, comparable to those of 16th century scholar and priest Martin Luther’s reformation of Christianity, “must include all those ideas on which the people who perpetrated the 9/11 attacks based their interpretations of sources. [...] We simply have to rethink the fundamental principles. It is [...] said that the fixed values of religion cannot be rethought. But I say that it is exactly these values that we must study and rethink.”

The thinking of Nahdlatul Ulama’s critical mass of Islamic scholars and men like Shahrour offers little solace to authoritarian and autocratic leaders and their religious allies in the Muslim world at a time that Muslims are clamoring not only for political and religious change. If anything, it puts them on the spot by offering a bottom-up alternative to state-controlled religion that seeks to ensure the survival of autocratic regimes and the protection of vested interests.

James M. Dorsey is Senior Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies of Nanyang Technological University, Senior Research Fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute, and an Honorary Senior Non-Resident Fellow at Eye on ISIS. You may follow him on Twitter @mideastsoccer.

0 notes

Text

China signals possible greater Middle East engagement

By James M. Dorsey

Two initiatives send the clearest signal, yet, that China may be gearing up to play a greater political role in the Middle East.

Touring the region this week, Foreign Minister Wang Yi laid out five principles Middle Eastern nations would need to adopt to achieve a measure of regional stability.

He called on the region’s rivals “to respect each other, uphold equity and justice, achieve nuclear non-proliferation, jointly foster collective security, and accelerate development cooperation.”

Chinese ambassador to Saudi Arabia Chen Weiqing said China would be “willing to play its due role in promoting long-term peace and stability in the Middle East.” China is focussing on Gulf security and the conflict with Iran as well as the Israeli-Palestinian dispute.

Mr. Wang said before leaving for the Middle East that China would be willing to host a multilateral Gulf security dialogue that would initially focus on securing oil facilities and shipping lanes.

China, however, is likely to find that maintaining good relations with all parties works as long as it focuses on economics and even that could prove tricky if a 25-year long political, economic, and strategic China-Iran cooperation agreement signed in Tehran this week by Mr. Wang and Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif proves to be what Iran suggests it could entail.

Moreover, finding common political ground among regional adversaries could be even riskier and more difficult.

Saudi Arabia has so far suggested that it has little interest in a gradual process that would allow Iran and its detractors to address low hanging fruit before tackling thornier issues, despite Chinese hints in recent months that it would engage provided Middle Eastern nations adopted its principles.

Saudi Arabia is the only Gulf country to have in the last year refrained from offering humanitarian aid to Iran, the country in the region hardest hit by the pandemic.

By the same token, Iran is unlikely to appreciate Mr. Wang’s reassurance during his stop in Riyadh that China supports Saudi regional leadership even if it does not express its view publicly in a bid to avoid jeopardizing its closer cooperation with China.

China sees endorsement of its principles as a way of managing rather than resolving myriad Middle Eastern conflicts and avoiding being sucked into them.

The Chinese initiatives are designed to exploit fears in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Israel that US President Joe Biden’s efforts to negotiate a return to the 2015 international agreement that curbed Iran’s nuclear program would not immediately address their concerns.

The Middle Eastern states want any agreement to also include limits on Iran’s ballistic missile program as well as an end to its support of non-state actors in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. The Gulf states and Israel have little faith in the Biden administration’s suggestion that a revival of the nuclear agreement that former US President Donald J. Trump abandoned in 2018 would create the basis for negotiations on non-nuclear issues.

The Chinese initiatives are also intended to cater to Middle Eastern concerns at a time that China and Western nations are locked into a tit-for-tat over criticism of Beijing’s brutal crackdown on Turkic Muslims in the north-western province of Xinjiang.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia, home to Islam’s two holiest cities, have sought to legitimize the crackdown, which reportedly involves forcing the region’s Muslim Uyghur population to violate Islamic law, by describing it as a legitimate fight against extremism and political Islam.

Saudi and UAE backing of the crackdown fits the two states’ religious soft power endeavours that propagate a vaguely defined notion of ‘moderate’ Islam centred on the principle of absolute obedience to the ruler and repression of political Islam. The Saudi-UAE notions fit hand in glove with Chinese autocracy as well as its efforts to Sinicize Muslim culture in China.

Nonetheless, Mr. Wang’s visit to Iran is likely to have set off alarm bells in Riyadh. A China that feels less concerned about falling afoul of US sanctions on Iran as Chinese-US relations dive could significantly help the Islamic republic dampen the effect of Washington’s punitive measures. Chinese imports of sanctioned Iranian oil have surged in recent months.

Few details of the China-Iran agreement have been made public, but it holds out the promise of Chinese investment in Iranian infrastructure, energy, mining, industry, and agriculture.

Mr. Wang also said on the eve of his Middle East tour that he would be inviting Israelis and Palestinians to Beijing for talks. He held out the prospect of China when it takes over the United Nations Security Council presidency for the month of May pushing for a resolution that would reaffirm the principle of a two-state solution.

There is little prospect that the Chinese initiative would be any more successful than its past efforts to mediate between Israelis and Palestinians, even if the United States were to support the resolution. Israeli elections this month, the fourth in two years, are unlikely to produce a government that would have the stability, cohesion, and willingness to negotiate a deal that would meet minimal Palestinian aspirations.

Said China analyst Eyck Freymann: “The status quo in the Middle East basically works in China’s favour. The United States spends enormous sums to combat extremist groups and protect freedom of navigation in the region, and China benefits… What China wants is to preserve this arrangement while gradually acquiring the ability to pressure individual countries to bend its way.”

A podcast version of this story is available on Soundcloud, Itunes, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, Spreaker, Pocket Casts, Tumblr, Podbean, Audecibel, Castbox, and Patreon.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore and the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute as well as an Honorary Senior Non-Resident Fellow at Eye on ISIS.

0 notes

Audio

Two initiatives send the clearest signal, yet, that China may be gearing up to play a greater political role in the Middle East.

0 notes

Audio

Amid Washington chatter about the future of US-Saudi relations, the kingdom has launched an unprecedented public diplomacy campaign to marshal business and grassroots support beyond the Beltway to counter anti-Saudi sentiment in the Biden administration and Congress.

0 notes

Text

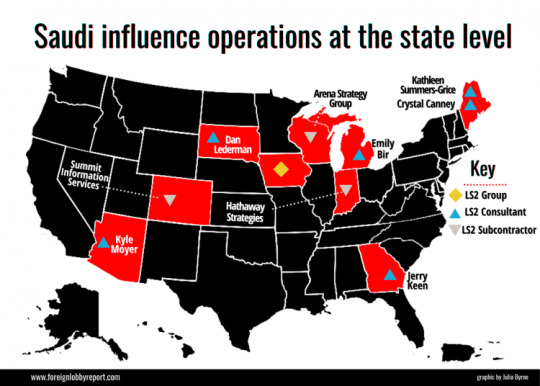

Playing US politics: Saudi Arabia targets Middle America

By James M. Dorsey

Amid Washington chatter about the future of US-Saudi relations, the kingdom has launched an unprecedented public diplomacy campaign to marshal business and grassroots support beyond the Beltway to counter anti-Saudi sentiment in the Biden administration and Congress.

To do so, the Saudi embassy in Washington has hired a lobbying and public relations firm headquartered in the American heartland rather than the capital. Iowa-based Larson Shannahan Slifka Group (LS2 Group) was contracted for US$126,500 a month to reach out to local media, business and women’s groups, and world affairs councils in far-flung states. “We are real people who tackle real issues,” LS2 Group says on its website.

Embassy spokesman Fahad Nazar told USA Today in an email that "we recognize that Americans outside Washington are interested in developments in Saudi Arabia and many, including the business community, academic institutions and various civil society groups, are keen on maintaining long-standing relations with the kingdom or cultivating new ones."

Prince Abdul Rahman Bin Musai’d Al Saud, a grandson of the kingdom’s founder, King Abdulaziz, businessman and former head of one of Saudi Arabia’s foremost soccer clubs, framed US interests, particularly regarding human rights, in far blunter terms.

Saudi Arabia “carries significant economic weight and it influences the region. The world cannot do without Saudi moderation. Because of its economy, its moderation, and its cooperation in the war on terror... the truth is that you need us more than we need you,” Prince Abdul Rahman said.

To boost the Saudi public diplomacy effort, the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies (KFCRIS) in Riyadh this month armed LS2 Group with a 32-page report, entitled ‘The US-Saudi Economic Relationship: More than Arms and Oil,’ that highlights the kingdom’s investments in the US, commercial dealings, gifts to universities, and purchase of US Treasury securities.

The report noted that US$24 billion in US exports to Saudi Arabia in 2019, $3.1 billion of which were arms sales, supported 165,000 jobs in the United States. US companies were working on Saudi projects worth $700 billion. The report said the kingdom held $134.4 billion in US Treasury securities and $12.8 billion in US stocks at the end of 2020 while US investment in Saudi Arabia in 2019 totaled $10.8 billion. It touted future investment opportunities in sectors such as entertainment where US companies have a competitive advantage.

In reaching out to the American heartland, Saudi Arabia hopes to garner empathy among segments of society that are less focused on foreign policy and/or the intricacies of the Middle East than politicians in Washington and the chattering classes on both coasts of the United States.

US President Joe Biden criticized Saudi Arabia during his election campaign in stark terms, calling the kingdom a “pariah.” Mr. Biden, since coming to office has halted the sale of offensive arms to Saudi Arabia that could be deployed in the six-year-old war in Yemen, released an intelligence report that pointed fingers at Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and said he would “recalibrate” relations with the Gulf state.

The Saudi public diplomacy campaign comes as Mr. Biden is under pressure from liberals and left-wing Democrats to sanction Prince Mohammed for the Khashoggi killing, define what he means by offensive arms sales, and potentially maneuver to prevent the crown prince from becoming king.

Prominent among the speakers LS2 Group rolls out is Saudi Arabia’s glamorous ambassador to the United States, Princess Reema bint Bandar, the kingdom’s first ever woman foreign envoy, a great granddaughter of its founder, and the US-raised daughter of Prince Bandar bin Sultan who was ambassador in Washington for 22 years.

Long active in the promotion of women’s sport, Princess Reema hopes to convince her interlocutors that Saudi Arabia as a pivotal global player is an asset to the United States that has embarked on far-reaching economic and social liberalization, including the institutionalization of women’s rights.

It is a message that is designed to put the kingdom’s best foot forward and distract from the kingdom’s abominable human rights record symbolized by the Khashoggi killing and the Yemen war.

Houthi rebels this week cold-shouldered a Saudi proposal for a ceasefire that would partially lift the kingdom’s blockade of the war-ravaged country.

If successful, the public diplomacy strategy could lead to grassroots organizations in Congressmen’s districts leaning on their political representatives in Washington to adopt more lenient attitudes towards the kingdom.

It would be a message that is aligned with positions adopted by the Israel lobby, various American Jewish organizations, and other pressure groups supportive of Saudi Arabia.

Going by Philadelphia World Affairs Council president Lauren Swartz and Alaska World Affairs Council president and CEO Lise Falskow, whose members are business leaders, students, educators, and other local residents interested in foreign affairs, the strategy is paying off.