Text

Things you generally won’t find in Lukumi (Santeria):

1. Gemstones and crystals. The only time these really come up is when someone makes a very fancy and expensive mazo (beaded sash). But you won’t find gems and crystals used for their own sake, and we attach no spiritual meaning to them - except for coral. Coral is very important to us.

2. Dried herbs. We use fresh herbs. Dried herbs may be used in espiritismo but not in Lukumi, as we believe once they’re dry they’re dead.

3. Casting a circle. If you are at a ceremony and they start casting a circle, you are actually at a Pagan coven and not a Lukumi ilé. We have nothing even remotely resembling this practice.

4. Identifying as ‘witches’ (except as a joke). While North Americans have a Wiccan-influenced positive idea about witches and witchcraft, the traditional Lukumi view is actually very similar to medieval European ideas: that witches are a negative force on society, that witchcraft is harmful magic, that witchcraft is a selfish act and thus against our community-based mindset. We have a very specific kind of spirit referred to in English as “the Witches” known euphemistically as Iyami (”Our Mothers”), who are the negative ancestral female spirits, often in the form of birds, that rule over society. In Yorubaland they are a highly secretive all-female secret society of post-menopausal women, or so I’ve been told, and the impression I’ve gotten is that no one would openly state they are a part of it. We do not call on them and very, very rarely say their real name for fear of attracting their attention (Ajé is the proper name for them and you will see people outside Lukumi try to reclaim this a lot but let me tell you: if you say this during a ceremony you will get a reaction between either cut eye from every elder or fully being asked to leave the room - as an example, a Pagan godchild of mine was sitting around between ceremonies reading a book with witchcraft in the title and my elder kind of freaked out and told him to put it away and gave him a long lecture about it being inappropriate to bring it to ceremonies). Some Lukumi, particularly those who are also involved in Palo, reclaim the term “witch” as a joke and as a push back against the long history of Afro-Cuban religions being deemed witchcraft and outlawed (this has a very tragic and ongoing history in both Cuba and the United States). But in general, we bristle against having our religion compared to witchcraft.

5. Wearing all black clothing. This is highly unusual for Lukumi aleyos and priests as the colour black attracts negativity. If you turn up to a ceremony in all-black, you will not be let inside. The exception is for children of Warrior Orisha like Eleggua, Ogun, and Ochossi. They can wear whatever they want, though even most of these omo will not wear all-black to a ceremony. There’s one ebo we do in which wearing all-black is required, but that’s a different story.

6. Self initiations. They don’t exist in Lukumi or other Orisha-based religions.

7. Veves. If you arrive at a ceremony and there are chalk or cornmeal patterns on the ground, you are actually at either a Vodou ceremony or a Palo ceremony.

8. “Bring your own drum” drum circles. The drummers in Lukumi ceremonies are highly trained and drum with specific rhythms on specific kinds of drums in specific arrangements of drummers. The most important kind of drum is only played by people initiated to that drum.

9. Tarot cards. While many of us read tarot as part of espiritismo, tarot has no role in Lukumi. Our divination systems are Obí (which may only be cast by priests or with the guidance of a priest), diloggun, and Ifá. Both diloggun and Ifá may only be read by priests with specific kinds of initiations (Olochas read diloggun, Babalawos read Ifá) and with extensive training. More than a system of divination, these are the ‘mouths’ of the Orisha - they are the Orisha speaking directly.

10. Mojo bags. If you are using mojo bags, you’re actually doing Hoodoo not Lukumi. Our closest equivalent are niche Osain, but these are really quite different and look to be entirely beaded balls.

973 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. Michael the Archangel. Quis ut Deus? Who is like God?

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is your yearly reminder that, in the lead up to Halloween, you should never use activated charcoal to spookify your food/drink

Activated charcoal will nullify your meds.

Anything you take orally can and will be absorbed by the activated charcoal, preventing it from doing you any good. There's a reason it's used in emergencies to counteract poisoning!!

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

Please stop trigger tagging with #epilepsy tw/cw/warning/etc.

I need every single person to understand how horrible tumblr’s tagging system is

I go into the tag for epilepsy and its all flashing lights. We can’t use our own tag because people without epilepsy fill it up with improper warnings.

Use ‘flashing’ in place of ‘epilepsy’ in your tags. You aren’t warning people of epileptics, you’re warning us of flashing lights. Please please tag properly. Epileptics say this endlessly and constantly and it’s ignored. You are risking lives by doing this.

Here’s proof of what I mean:

THIS POST IS 100% OKAY TO REBLOG, I ENCOURAGE PEOPLE WITHOUT EPILEPSY TO ESPECIALLY DO SO!

97K notes

·

View notes

Photo

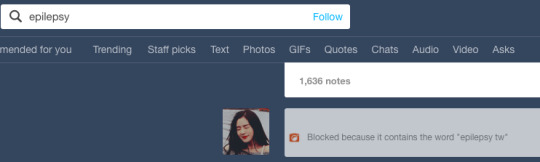

🐚Yemonja/Yemaya body beads/ileke set 🌊

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maferefun Yemoja

Artist IG: leo_barbosa34

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

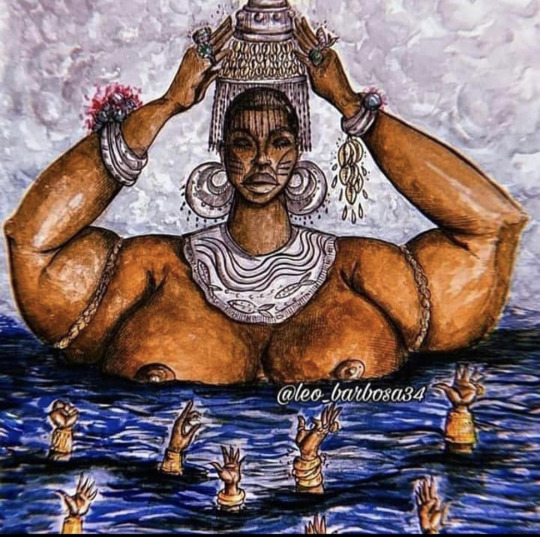

ORISHA OYA

Oya is the favorite wife of Shango, the only wife who remained true to him until the end, leaving Oyo with him and becoming a deity when he ascended. She is Goddess of the Niger River, which is called the River Oya (odo Oya), but she manifests herself as the strong wind that precedes a thunderstorm. When Shango wishes to fight with lightning, he sends his wife ahead of him to fight with wind. She blows roofs off houses, knocks down large trees, and fans the fires set by Shango's thunderbolts into a high blaze. When Oya comes, people know that Shango is not far behind, and it is said that without her, Shango cannot fight. The verses tell that Oya is the wife of Shango, "The wife who is fiercer than the husband." Her town is Ira, which is said to be near Ofa.

Asé

Grand rising!

335 notes

·

View notes

Photo

at Utica, New York

https://www.instagram.com/p/CPdWXfgnFW9/?utm_medium=tumblr

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

save for yourself and for future generations

464K notes

·

View notes

Photo

There is a saying, from the Africans in Haiti

“You European go to church and speak about God, We dance in the Temple and become God.”-African Proverb

Music and dance were highly valued in ancient Egyptian culture, but they were more important than is generally thought: they were integral to creation and communion with the gods and, further, were the human response to the gift of life and all the experiences of the human condition.

Dancers were not relegated only to temples, however, and provided a popular form of entertainment throughout Egypt. Dancing was associated equally with the elevation of religious devotion and human sexuality and earthly pleasures.

In Egyptian theology, sex was simply another aspect of life and had no taint of ‘sin’ attached to it. This same paradigm was observed in fashion for both male and female dancers. Women often wore little clothing or sheer dresses, robes, and skirts.

In the African worldview, dance is a conduit of individual and community healing. African conceptualizations of illness and health integrate social, spiritual, physical and mental realms, all of which are impacted by trauma.

The Vodou drumming rituals call upon abstract ancestral spirits, called Loas (or Lwas), for their aid, instruction, special powers and strengths as embodiment of certain principles or characteristics. While certain aspects of this religion may share the same roots, it is completely contrary to the stereotype of black magic, witch doctors, pins in dolls, and zombies portrayed by New Orleans style Voodoo (a variation of the name).

The Vodou drumming rituals call upon abstract ancestral spirits, called Loas (or Lwas), for their aid, instruction, special powers and strengths as embodiment of certain principles or characteristics. While certain aspects of this religion may share the same roots, it is completely contrary to the stereotype of black magic, witch doctors, pins in dolls, and zombies portrayed by New Orleans style Voodoo (a variation of the name).

There are so many subtleties and complexities in Haitian drumming, particularly in its relation to the rites and rituals of Vodou, that an overview of this kind cannot truly describe them in any detail. For instance, many of the rhythms have variations, each with their own subtitles, each assisting different loa. A good example of this is found in the Mahi rhythm - Mahi Darielle, Mahi Japeté and Mahi Deté are all variations of Mahi Simp (from the French Simple). However, some discussion of forms and techniques involved is essential.

An extremely important aspect of the performance of this music is the Kasé (from the French Casser, to break). The kasé is a break from the main cycle of the rhythm into a kind of alter-ego rhythm, usually instigated by the maman drum. In some cases, all the drums respond to the kasé with their respective changes, but often it is only the maman who will change, or at least the change in the segon is more subtle. Some kasé patterns stray quite far from the main rhythm, some create a counter pulse to it and others still remain fairly rooted in the pulse. Every rhythm has a kasé, and every kasé has its own way to enter and exit from the main line. Dancers also change their steps to follow the kasé.

The kasé is typically played to assist with aspects of the Vodou ritual, such as pouring libations before the drums. Sometimes these are cued by the officiating priests, sometimes by the maman player himself. However, the most dramatic use of the kasé is to facilitate spiritual possession. If the maman player recognizes the physical signs at the inception of a possession of one of the servants or dancers, he will play a heated kasé to entice the loa and may keep up the intense drumming of the kasé until the chwal in question is fully possessed.

The drums of Vodou employ techniques completely unique to the style. One of the most dramatic and difficult techniques to master is called the Siyé (from the French essuyer, to wipe). With this technique the drummer (usually a segon player) wipes the drum from the edge to the centre using the tips of his index finger, often with the thumb behind for support. As the finger rubs across the drumhead, a moaning sound is produced. The technique is employed as an embellishment on congas and is often referred to as a “Moose Call”. While the tone is very tricky to learn, it is even harder to do in the rapid succession which is required for some rhythms.

Vodou rites are done to call upon spirits, called Loas (or Lwas), for their aid, instruction, special powers and strengths. Loas are ancestral spirits who have become abstracted through the generations to become embodiments of certain principles or characteristics. A great feast is often prepared to entice the Loas to attend. Practitioners of the religion wear white clothes and are assisted by Ougan and Manbo (male and female Vodou priests, respectively) to become “possessed” by the loas. Through singing, dancing, and particularly the music of the drums, spirits come to “ride” their mortal hosts. The analogy of someone riding, and thereby controlling, a horse is given as an explanation of this phenomenon. The word Chwal (from the French cheval) is used to describe one who is “being ridden”. Spirits impart wisdom and direction through their chwals for the servants of the faith.

The loas are divided up into several nanchons (from the French nations), families of spirits from the same ethnic group and/or serving a similar function. The most prominent nanchons are Rada, Nago, Djouba, Petwo (also written Petro), Kongo, Ibo, and Gède. Traditionally each one of these nanchons would have had particular rites, rhythms and adherents. They even would have had their own drums that were unique to that nanchon to call upon its loas. These drum sets are known as batterie (from the French for “set of drums”). Today, due to economic constrictions and social and geographic changes, the drums from the Rada batterie are the most common, with the Petwo drums also extant.

Below is an overview of the several nanchons, the qualities and origins of their laws, and the rhythms and dances associated with their rites.

Rada - The loas of this nanchon are strong, but benevolent, balanced in their treatment of their servants. These are the most revered spirits, and many Vodou rituals begin with adulations for them. They originate from the Fon people of Dahomey (present day Benin). In Fact, the word Vodou comes from the Fon word for “God”. There are many loas in this group. To name a few: Papa Legba – Guardian of the Crossroads; Marassa – twin spirits who represent childhood; Dambala – the serpent spirit who represents energy and life; Ezili Freda – spirit of love and femininity; Lasirèn – mistress of the sea and music. Rhythm and dance styles played for the Rada nanchon include: Yanvalou, Parigol, Zepol, Mahi, Fla Voudou and Daomé.

Nago - The loas of this nanchon represent power. Its members embody attributes of warriors and leaders. They originate from the Yoruba people of south-western Nigeria and are closely associated with Ogun (sometimes written Ogou), the Yoruba Blacksmith-God. The loas in this group have names starting with Ogun, like Ogun Fèray and Ogun Badagri. As such, they are represented by steel and fire. The Nago rites are replete with military imagery. These spirits give masculine, fatherly council and support. The rhythm and dance style associated with these rites is also called Nago.

Djouba - The loas of this nanchon are connected to cultivation and farming. They personify peasants, both in appearance and manner. It is surmised that this nanchon comes from the island of Martinique. The principal loa for this group is Azaka. The rhythms and dance styles associated with this nanchon are Djouba (Matinik) and Abitan.

Petwo - The loas of this nanchon are aggressive, demanding, quick and protective. The origins of this nanchon are unclear, but many believe them to be the spirits of the original slaves and Haiti’s indigenous people (The Taino – almost completely wiped out after European contact), a sort of “home-grown” family of spirits. These spirits were called upon during the slave revolts beginning in 1791 which ultimately led to the defeat of Napoleons troops in 1803 and independence in 1804. The name might be derived from a slave priest of mixed African and Spanish Blood name Don Pedro who was one of the rebellion’s leaders. One of the loas in this nanchon bears his name (Jean Petwo). Another, Ezili Danto - sister to Ezili Freda in the Rada nanchon - is a spirit of love, but with a penchant for violence or revenge. The rhythm and dance styles associate with Petwo include Petwo, Makiya, Bumba, Makanda, and Kita.

Kongo - The loas of this nanchon are ancestors of the Bantu people of the Congo river basin. These spirits are gracious, and enjoy song and dance. In fact, music played for the Kongo nanchon is unique in that it is also popular in secular settings. In vodou worship houses called tanp (from the French temple) dolls representing these spirits are displayed adorned in brightly coloured clothing. Sprits include Kongo Zando and Rwa Wangol. The rhythm and dance style associated with this nanchon goes by the same name.

Ibo – The loas of this nanchon are from the Ibo people in south-eastern Nigeria. Their chief attributes are pride, to the point of arrogance, and are difficult to satisfy. These spirits preside over sacred items called Kanari, clay pots in which the soul of the initiate is said to reside during ritual possession. The best known loa of this group is Ibo Lélé (the chatterer). The rhythm and dance style associated with this nanchon also goes by the same name.

Gède - The loas of this nanchon are the spirits eroticism and death. More accurately they control the cycle of death and life. They are represented by figures in black with white faces. They are also tricksters. The most famous loa of this nanchon is Baron Samedi. He is macabre, obscene and lives in cemeteries. Other loas include Gède Nibo, Baron Lakwa and Gède Zarien. The Vodou ceremony almost always ends with the rites for Gède nanchon. The rhythm and dance style associated with this nanchon is called Banda.

While these seven nanchons all have their distinct attributes, in a more general way the nanchons are divided into two branches, each of which takes its name from one of the nanchons within it. While there is no consensus on this point, it can generally be argued that the Rada branch includes Rada, Nago and Djouba, and the Petwo branch includes Petwo, Kongo, Ibo and Gède. Some people place Djouba under the Petwo Branch, and some others consider the Kongo branch its own entity. For the purposes of drumming, we will use the two-branch differentiation, as rhythms most rhythms being played in non traditional contexts today use either the Rada or Petro batterie.

The Rada batterie and The Petwo batterie display as much contrast as the loas of the nanchon branches for which they play. The table below will illustrate some of the differences

When slave owners forced their Catholic beliefs and saints on them, slaves continued their worship in secret, linking each saint to an African deity and praying to them.

“The slave owners wanted to suppress the religion because they were afraid of the supernatural,” said Carrol F. Coates, a professor of French and comparative literature at the State University of New York in Binghamton who translates Haitian books into English. “They feared to some extent that the spirits could actually have an impact in their world.”

2K notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

I really enjoyed this video about Ogun! I’m trying to learn more about the Orisha, and this video was very helpful! If you’re wanting to learn about Ogun, consider this video!

109 notes

·

View notes