Text

[QOL] Queer On-Line – Creating Internet Playgrounds in Digital: A Love Story, Hypnospace Outlaw, and Secret Little Haven

Being queer in the real world is hard. The oppressive malaise of everyday live ensures encounters with microaggressions and hateful bigotry on a regular basis, and self-expression is subject to an encompassing suffocation due to the restrictive pressures intwined with living in a heteronormative society. Once, in an age of utopic thinking, we thought of the internet as a place of escape, a place of safety to “simulate online what so many people who are gay or questioning their sexuality are too afraid to do in the ‘’real’’ world” (Harrison 288). The internet eschewed the confines of the real world, our bodies literally left behind as cyberspace welcomed us to construct a new ‘I’ – one unbound by physical gender expression. The lack of physical boundaries meant that identity could be forged purely from the textual and the visual, aspects of oneself easily created and adapted to suit how one felt inside rather than how the real world projected them on the outside. This techno-optimism characterises the early-internet as a place of freedom, a “cyberspace” that “would free Internet users from identities tied to the body – sexuality and gender, among others – such that you can become whoever you want” (Rodriguez 6).

The Internet of today is not freedom. Through the proliferation of social media, the anonymity promised by the early Internet has been abandoned wholesale for an overabundance of presence. We are no longer denizens of a cyberspace playground, but a cohort of billions of faces whose personal lives, histories, and physical appearances are available at a click of a button. Constructing a new identity in this landscape of overwhelming data, where every service demands your phone number, address, or even ID to ensure you’re truly human, is a herculean task. The internet is not a place of play, but a place of surveillance and harassment.

Safe Little Haven (hereby SLH) (Hummingwarp Interactive, 2018), Hypnospace Outlaw (hereby Hypnospace) (Tendershoot, 2019), and Digital: A Love Story (hereby Digital) (Love Conquers All Games, 2010) are all interface dramas set in this utopic early internet of the pre-2000s. Where the reality of cyberspace in the modern age is a place that offers no escape from hate crimes or harassment, these games all offer an alternative. A playground that is built upon a nostalgia for an internet that many of us never experienced, if it ever truly existed. These three games live “outside of normative boundaries” (Ruberg 10), showcasing a queerness that distorts the reality of cyberspace through meticulous simulations of personal computers to tell distinctly queer narratives about love, identity, and nostalgia. They question the internet we are forced to use in our everyday lives by proposing an alternative: true playgrounds of experience that allow players to engage with a faux internet that accepts their identity and self-expression. They represent a bespoke queer game design, one that simulates a normalised concept (using a computer) and re-mystifies it, queering what was once non-normative back to its utopic shape of a place without bodies or time. They are “queer games with queer stories”, (Shaw & Friesam 3884), games that represent queer characters and allow you to play as a queer identity. They are also games that showcase queer design sensibilities through their aesthetics, textuality, and design sensibilities.

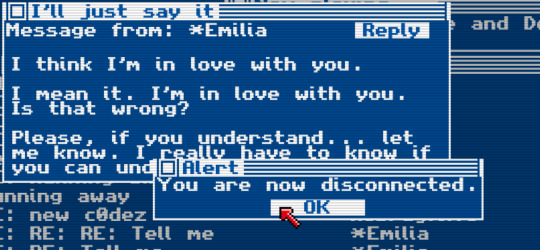

This paper will engage in dialogue with queer game studies and queer experiences of the internet to highlight how SLH, Hypnospace, and Digital all present welcoming playgrounds for the safe expression of queerness. It is dedicated to how these games allow for gender play and exploration of atypical queer relationships. SLH allows the player to embody a trans teenager who is slowly introduced to her gender identity through the safety provided by her online friends and the fandom forum she engages with. By controlling her PC, we can co-experience a feeling of acceptance of one’s identity alongside Alex, an experience many queer players will not have had the joy of having prior. SLH additionally creates a safe space for this queer exploration, while also complicating its narrative with the inclusion of periodic breaks of the safety as IRL aspects of Alex’s life invade the gamespace. These violations of the safe space are consistently the fault of Alex’s father and her IRL friend, Andy, both of whom demonstrate traits of toxic masculinity. Lastly, both SLH and Hypnospace introduce gameplay in the form of self-expressive customisation options, such as dress up dolls, which promote historically feminine play, a rare facet of games not directly marketed to girls. Elaborating on love in cyberspace, Digital presents a love story between the player and *Emilia, a character you interact with through email that is revealed to be an artificial intelligence. By presenting a conventional love story and then queering it through making one partner non-human, the game normalises queer romance.

Gender Play in Cyberspace

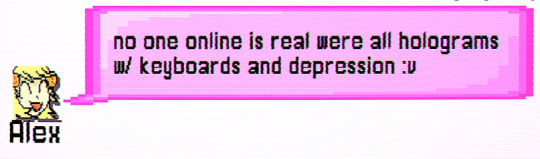

Figure 1. Secret Little Haven. Personal Screenshot

While most games allow the player to embody the presence of a bespoke protagonist with their own traits and identity, few games allow you to take on the act of controlling a trans character – less still one in the process of discovering and experimenting with their gender identity. SLH puts players in control of Alex, a young girl gradually discovering what being trans is through engaging with her online friends and denizens of an online forum for her favourite TV show. The game is entirely interfaced through the faux computer operating system ‘SanctuaryOS’, which reduces every character to words on a screen and their profile picture, including Alex. This obfuscation displaces the player from reality or a simulacrum of reality, instead allowing them only to occupy a digital space. Without physical attributes to characterise Alex or her friends, players are introduced to the gender play the game promotes through a distinctly un-gendered lens – due to her unisex name, players are free to assume her gender or lack thereof as her online friends do. She is distinctly masculinised or feminised only through assumptions based on her texting styles by her online friends and the player. Through this, the masculine identity that society in the real world sees within Alex is obscured, allowing her to define for herself what aspects of gender she wants to portray and be seen to embody. Our gateway into her IRL life through interactions with her male IRL friend Andy and her father are the only times Alex is gendered male rather than agender or female, showing the safety that the online proffers is only sacrosanct if it stays a ‘secret little haven’, unopen to the real world. Rodriguez states “because the physical body is invisible on the Internet, cyberspace would free Internet users from identities tied to the body—sexuality and gender, among others—such that you can become whoever you want. In turn, people could create new, virtual versions of themselves that did not align with their physical selves and identities.” (6). This freedom to “become whoever you want” belies an ability for people to experiment with their gender identity, and the simulation of this phenomenon in SLH furthers this into a zero-risk, zero-stake playground that pushes anyone to at least question the fluidity of their gender through the simultaneous embodiment of a questioning trans teenager as protagonist and player character. This comes at odds with Reeser’s concept of masculinity in disguise, which establishes the ability for men to be wolves in “sheep’s clothing”, embodying “woman-like traits for ends that are anything but non-hegemonic” (2). The assumption in Reeser’s article is that male to female gender play is intrinsically tied with the idea of a predator invading “all-female spaces” (3). I would argue that SLH presents an alternative gender play, one that invites men to engage with and better understand gender so that they can be introduced to the concept of gender fluidity just as Alex herself is. SLH allows for safe gender play, without the scopophilia inherent with allowing men to observe the overwhelmingly female cast in the game, due to its graphical simplicity and fully obfuscated presentation.

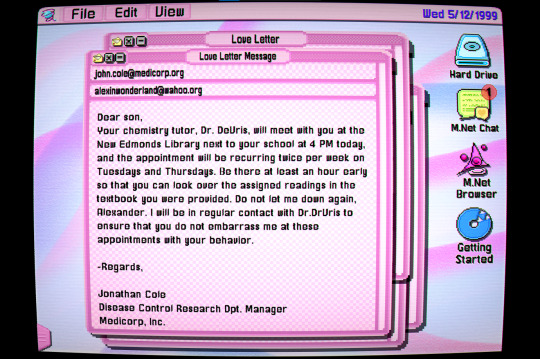

Figure 2. Safe Little Haven. Personal Screenshot

However, narratively, SLH often unveils the digital. At key moments throughout the game, the player is jolted away from their digital safety and into a horror-coded conversation with Alex’s father. The narrative conflicts within the game are spawned by these fraught conversations with Alex’s overbearing and toxic father, and the disconnect between the two is what drives Alex further and further into her digital haven even despite her father’s threats of taking away her computer for spending too much time online. These interruptions of the gameplay flow drastically alter the colour composition and mood of the game. The once “vibrant pink and purple SanctuaryOS interface” that presented a feminised facsimile of the “utopic possibilities of the early internet” (Harkin 166) are distorted into monochrome, with vicious scanlines crumbling down the screen, the video desyncing in real time. The femininity of the online space, the rich purples and pinks, is overwhelmed by a masculine haze that follows Alex’s father’s presence, the literal toxicity of such acting as a computer virus infecting ‘SanctuaryOS’, one with the goal to remove the femininity (and subsequently safety) of the space. The chat box, your primary means of interacting with the game, is set to no longer obey plausible time – your father’s texts rapidly come through, with your choices in how to reply distorting. While in the normal game your choices are logical and fit Alex’s character, your dialogue choices slowly become limited and even change after you’ve sent them, demonstrating Alex’s inability to challenge or get through to her father. It is only through skills taught by her online friends, be they coping mechanisms to combat the anxiety and stress of Alex’s IRL life, or practical skills such as Laguna’s programming tutoring leading to Alex being able to hack into her father’s account (Harkin 166), that Alex can reconnect with her father and make some steps towards growth for their relationship. It is potent that the panacea for their strained relationship is that of digital code taught by Alex’s online friend – the digital is directly impacting the real as a positive force, a reverse of the dynamic prior where the real invaded the digital to corrupt and distort Alex’s online playground. Harrison describes internet chat rooms as “a space in which to write new narratives” for “those at the sexual margins”, allowing them to “(re)integrate themselves into a virtual world” (288). While most of SLH matches this freeing space of narrative creation, of self-discovery and identity forgery, it is in these dramatic conversations with Alex’s father that integration with the virtual world is no longer possible. Alex is thrust into the real world, with all her anxieties and struggles, as it corrupts her portal to her haven – the digital screen dies, she is booted out as we are as players, and can only continue the game after she is able to log back in the next day. By both giving players the safe space and taking it away, it shows how important queer playgrounds are for the forging of new identities and gender expressions, as we are forced to experience the harrowing terror of being denied our right to expression and the freeing sublimity of reclaiming it.

A key constituent of an interface is its propensity for customisation. Both Windows and MacOS offer and have offered a multitude of customisation options in their frontends, including wallpapers, colour themes, and the ability to download third-party applications and games. In support of the verisimilitude of their simulation, SLH and Hypnospace both offer similar functionality. One of the main applications of SanctuaryOS is Doll Atelier, a dress up game that allows Alex and players to customise and create their own avatar. One can also download additional costumes for this avatar by searching through the forum Alex frequents or by chatting with her friends. This type of play is often female coded, mimicking girl-focused games and applications that tie into brands such as Barbie. Because of this coding, it is a type of play that is often unimplemented in games marketed for boys (though character customisation is common in RPG games, the standalone nature of doll dress up games and their feminine theming I’d argue separates them into different experiences). Since SLH is not feminine coded in the same way, it opens this type of play to people who may have never experienced it before, dismantling masculine stereotypes of play and leaving players vulnerable to new play types. Narratively, this emulates Alex’s own experience with SanctuaryOS, a place she can express her own femineity while her previous lived experiences IRL have been largely masculine. Alex’s father comments on Alex’s less gendered avatar, imploring her to remove it, seeing it as a threat to her masculinity that makes her stand out and appear childish. His brand of hypermasculinity, emotionally closed off and overbearing, sees anything feminine as weak and therefore unfit for his “son” who should be studying for a good career. Gender play is unfit for men, in his eyes. It is notable that his own icon in ‘SanctuaryOS’ is that of an ever gazing, 1984-esque opened eye, staring at the player (and therefore Alex) from the corner of the chat window. Toxic masculinity wants to know, to control, to have the power to prevent/”protect”, yet it does so in ever oppressive ways.

Figure 3. Secret Little Haven. Personal Screenshot

Hypnospace also allows for customisation in similar ways, despite its theming being completely agender. In Hypnospace you play as an anonymous, ungendered spectator to a wider internet, tasked with exploring cyberspace as a moderator of its content. This distant approach makes the player even more vulnerable to queer design, as the player is free to adjust their operating system to express their own interests and experiment with different theming as they unlock more through play. “Playing with one’s own vulnerability achieves its own, queer and compelling, joy. But this is not the joy of mastery, amorous consummation, or triumph: it is the queer pleasure of playfulness that risks the self to imagine new forms of being with Others” (Gatí 98). By eschewing the traditional game win states of triumph or mastery, these queer game designs instead make finding your own identity part of the play through experimentation and customisation. They allow players to “imagine new forms of being”, removing physical barriers from their ability to express themselves.

Figure 4. Digital: A Love Story. Personal Screenshot

Figure 5. Digital: A Love Story. Personal Screenshot.

Conclusion

Creating queer game experiences is complicated precisely because video games are “contradictory: spaces of freedom and possibility” whilst being “simultaneously normative and oppressive” (Ruberg 21). The turn towards emulating nostalgic computer interfaces in SLH, Hypnospace, and Digital considers this contradiction and gives players the space for freedom and expression whilst separating their experiences from normative reality. The dedication to verisimilitude of computer interfaces and the consequences this has for the player to play with identity and gender makes space for a type of queer playground game design. Computers are everyday objects in society, but by placing them into nostalgic time-pockets and setting queer stories inside of them, we are reminded of their once utopic potential for us to “become whoever [we] want” (Rodriguez 6). SLH puts players in the middle of a young girl’s journey of trans self-discovery, allowing us to better understand the elation of finding an identity that aligns with our needs and the despair when people try to take that away from us. Both SLH and Hypnospace show the importance of customisation and self-expression in games for all genders, and how they allow for a deeper understanding of the intersections between the self and gender. Digital shows how love is boundless, and it's queering of heterosexual romance through the internet is an example of how providing places of safety to play queer is an effective way to open players up to the possibilities of queer expression. The internet should be a safe place to be queer; these games allow us to rediscover the utopian promise that real technology betrayed.

References:

Gáti, Daniella. 2021. ‘Playing with Plants, Loving Computers: Queer Playfulness beyond the Human in Digital: A Love Story by Christine Love and Rustle Your Leaves to Me Softly by Jess Marcotte and Dietrich Squinkifer’. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 12 (1): 87–103.

Harkin, Stephanie. n.d. ‘Girlhood Games: Gender, Identity, and Coming of Age in Videogames’.

Harrison, Douglas. 2010. ‘No Body There: Notes on the Queer Migration to Cyberspace’. The Journal of Popular Culture 43 (2): 286–308.

Hummingwarp Interactive. 2018. Secret Little Haven. PC Game. Hummingwarp Interactive.

Love Conquers All Games. 2010. Digital: A Love Story. PC Game. Love Conquers All Games.

Reeser, Todd W. 2023. Masculinities in theory: An introduction. John Wiley & Sons.

Rodriguez, Julian A. 2019. ‘Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Media: Key Narratives, Future Directions’. Sociology Compass 13 (4): 1-10.

Ruberg, Bonnie, and Adrienne Shaw, eds. 2017. Queer game studies. U of Minnesota Press.

Shaw, Adrienne, and Elizaveta Friesem. 2016. "Where is the queerness in games?: Types of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer content in digital games." International Journal of Communication 10: 3877-3889.

Tendershoot. 2019. Hypnospace Outlaw. PC Game. No More Robots.

#video games#essay#analysis#games#secret little haven#game essay#media analysis#digital a love story#hypnospace outlaw

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life is Queer: Queer Time and Identity in Life is Strange and Member of the Wedding

We cannot control the flow of time. We passively experience the effects of time as we move through life, yet, who is to say that we all experience that time in the same way? Delays, stutters, and hitches disturb sequential temporality, a temporality more and more defined by “chrononormativity”, a mutually experienced time which helps “institutional forces come to seem like somatic facts” (Freeman 3). Institutions which vie to control the “bodily tempos and routines” (3) of daily life and therefore continue to push the “logic of time-as-productive” (5) are ever-present in modern society. One must always be doing something productive with their time – it is finite, it cannot be rewound, so it must not be wasted. Pivotally, the ability to queer time, and step away from traditional future-progress thought patterns is a rebellious act which liberates individuals from capitalistic structures which aim to control and normalise life.

Unreality, then, gives us a new way to look at time. By escaping the plains of everyday living, with its constant reminders of progressing time (calendars, clocks, alarms, schedules etc), we can consider realities without linear time. In a world where structures of power that control our mutual experiences of time are ever-present, and continually tied to oppressive governments and corporate structures, there is undeniable value for queer individuals to play with different interpretations of time. I single out queer individuals specifically as benefitting from this because our relationship with sequential time leads to a childhood defined by a pending heterosexuality, our “official destination” (Stockton 7) come adulthood. By rejecting the expected standard and being queer, we already hold some victory over the structures of modern time. Our existence is a rejection of chrononormativity, which makes its structural effects more potent, as we must linger in a world built for and out of systems of heterosexual dominance and expectations. By playing within other worlds, all queer people are given the opportunity to see time through new lenses – ones which may seem to line up more with our personal experiences as queer people over the heteronormative reality we live in.

These other worlds are numerous, from all manner of media, but in this essay I focus specifically on two extremes – the classic novel format, and the modern video game. By choosing to analyse Member of the Wedding, a queer bildungsroman novel, alongside Life is Strange, a queer coming of age video game, I hope to establish how Freeman’s ideas around queer temporality linger through art due to their persistent relevance to queer lives. Analepsis is used throughout the Member, queering our experience of the novel’s time through its continual movement between events of the presumed present and immediate past, obfuscating the novel’s actual narrative length of “four days” (Seymour 306). This time-play consequentially queers our perception of the novel, and of its protagonist. Frankie, as we read the novel, changes and molds herself into different identities and personas through continual name changes. Queer time and queer identity mix to create a queer narrative which defies systems of structure. Further, LiS showcases the impact of modern technology in queer storytelling, presenting a player-controlled narrative led by a bisexual time travelling teenager, Max Caulfield, as she uncovers a sci-fi murder mystery with her best friend and potential lover, Chloe Price (Fig 1). The game queers time explicitly, allowing Max to reverse time to reconsider her (and therefore the player’s) narrative choices or relive moments in the immediate past. I argue this ability to reverse time is a ludic version of the “odd” (Seymour 306) analepsis seen in Member. Additionally, the ability to choose your narrative as a player is a way to closely identify with a queer power fantasy which allows us to act without chrononormative structures. We can test our sexualities without consequence in this virtual queer simulator. Lastly, I touch on the ending of LiS, and its ultimate irreversible choice between sacrificing Chloe, your soulmate, or the entire town the game takes place in and the ways in which academics and fans responded to this choice through an examination of the player statistics of choices made worldwide.

Figure 1. Life is Strange. Personal Screenshot.

Time flows. Between us, around us, and through us, we cannot avoid time. When we sit down to read a book, we necessarily allocate our time to its consumption, and our time is exhausted whilst the diegetic time of the narrative we are reading is concurrently elapsing. This verisimilitude of elapsed time can be a functional technique to enhance the realism of a narrative, but since readers do not consistently read at the same pace, and narratives rarely limit themselves to real-time telling, storytellers necessarily use techniques such as ellipses and analepsis to ‘play’ with time. Rejecting linear time, narratives are queered by flashbacks and flash-forwards in the service of the story. Simply: narratives are unbound by our time, and the hour we spend reading can reflect years within a novel’s diegesis. This fact is incredibly freeing in that it allows a writer to present complex and time-intensive developments without consuming a proportional amount of the reader’s time. Notably, in the case of Member, playing with time can allow for a playground outside of the rules of chrononormativity – the “past” no longer need predict and become “material for a future” (Freeman 5). Instead, the future can become material for the past, or even purely immaterial. Freeman speaks of the chrono trappings inherent in modern society which novels allow an escape from. As Member meanders towards the titular wedding event, we as readers are thrust back and forth between events of the near-past, the already-covered past, the present, the future and everything in between. Seymour labels this liberal analepsis as “odd”, something which makes it difficult to “recognize the novel takes place over only four days.” (306). It creates a disconnect between the flow of time that the reader is naturally used to and McCullers’ imagined time. This disconnect is reflected in the start of the novel, where Frankie reflects on the prolonged feeling of Summer, blazing through descriptions of her experience of the season in half-a-page as if it was a “green sick dream” (1). Dreams are areas outside of normal time, outside of reality. They are a queered reality, an escape much like novels themselves. Eventually, on the last day of August, suddenly “all this was changed”. Frankie remarks “It is so very queer. (…) The way it all just happened”. (1) Starting the novel with this description of prolonged dream-like past only to shatter it with the queerness of the present shows the fickle adaptability of time and prepares the reader for the chronological techniques that are used throughout the novel. For Frankie time is experienced variably, both quickly and slowly. Pivotally, it shows the queerness of time, the way it flows around us yet how we all experience it so differently. In Member, time is a lived experience; it doesn’t respect logical boundaries. It responds to the mood of Frankie, her subjective experience of time, and moves between and through events accordingly.

Time affects identity. The ways we experience time are dependent on our independent circumstances, and queer people, who inherently reject the heteronormative standard of society through their very existence, are in a unique position of rebellion against chrononormativity as well. The “child who ‘will be’ straight is merely approaching while crucially delaying (in its own asynchronous fix) the official destination of straight sexuality, and therefore showing itself as estranged from what it would approach.” (Stockton 7). From childhood, time and queerness are linked through this “delay”. Stockton sees that the expected endpoint for children is rejected by queer people, which retroactively means their childhood is stuck in a sort of identity stasis where queer expression cannot be discovered or acted out until the child reaches adulthood. Childhood becomes wholly a “green sick dream” (McCullers 1), a prolonged period of identity paralysis until the sudden access to queer performance in adulthood. However, this childhood is not a linear progression to adulthood. Despite child protection laws and social expectations, many teenagers experiment with their sexualities openly regardless, forcing the penny drop of queerness earlier in life to escape the “official destination of straight sexuality”. Queer identity rejects societal norms. In Member, Frankie rejects predetermined aspects of her identity through her continual name-changes. Frankie laments that the “world seemed separate from herself” (31) near the beginning of the novel when she has yet to change her identity, yet when she first changes her name, it was “the day when (…) the world no longer seemed separate from herself and when all at once she felt included.” (59) Identity change here is linked to a sense of acceptance and belonging, both key themes in the novel. Seymour remarks that these name changes are “performances, rather than markers, of growth and change.” (304), however, I argue that queer identity is built through a series of performances made tangible through acceptance of that performance into one’s own self. Even though Frankie seemingly forces her numerous name-changes throughout the narrative, it is the dedication to this performance, this experimentation with other identities, that truly showcases her as a queer protagonist. The willingness to try and reject elements of life thrust upon her is the quintessential essence of queer expression.

Performance, then, is the key element that LiS adds to the queer coming of age narrative framework. Specifically, the ability to perform as the protagonist of the story through interactive play and choice-making. Max Caulfield doesn’t need to change her name to reinvent her identity – the player injects their own life, their own name, to form the narrative of LiS. Released across five staggered episodes throughout 2015, LiSis an interactive choice driven video game set in suburban Oregon, following the life of 18 year old Max Caulfield as she navigates her newfound power to reverse time. The game “narrates the existential maturation of an adolescent girl” (Miranda 826) and allows us as players to determine the direction this maturation goes. It is an explicitly queer narrative, with Max being a “genuinely queer character predominantly occupied with her relationship with Chloe” (Waszkiewicz), and regardless of the amount of player interaction within the narrative, the relationship between these two characters forms the core of the game’s story. Importantly, as a game, it can present its narrative through visuals and audio. The use of a player-controlled camera allows for bespoke ways to see each scene, creating unique experiences for each player. Unlike a novel, the fabric of a game is formed through the player’s ability to express themselves in the playspace through interaction, and this in turn effects the narrative. Choices are not the only impact of the player, meaning this isn’t an experience that is able to be replicated by a choose-your-own-adventure book format. The game is constantly giving the player minute choices through the very act of using a controller as an input and progression mechanism. Novels, too, have an input mechanism in the form of the page turn, and the pace of reading. However, in terms of a consumer’s agency, the video game form is synergistic with a narrative framed around time and choice as the very act of playing any game is fuelled by choices. This is an inherently queer way to experience a narrative, as it allows for such player agency and expression that it rejects the rigidity of storytelling. You are both story crafter and story consumer. I can turn the camera to frame Chloe between an American flag and a parental advisory label to symbolise her as trapped in-between a society she hates and the anti-social and abrasive personality she embodies to rage against it (Figure 2), or I can focus the camera instead on the radio in her room to listen to the licensed indie soundtrack, and both would be valid methods to experience the game.

Figure 2. Life is Strange. Personal Screenshot.

As a choice driven drama, there is an inherent tension between the time travel mechanic and the severity of choice. Previous games in this genre, such as Telltale’s The Walking Dead, are built upon the tension created by forcing the player to make irreversible and consequential choices. However, LiS deconstructs this trope by making all but the final choice immediately reversible, allowing the player to experiment with different choices. Time travel is used as a vehicle for experimentation and play. Like Member, the time travel also has a queer ability akin to analepsis. If time in Member flows according to Frankie, time is literally controlled by the player in LIS, flowing according to our will. This powerful control fuelled by the interactive narrative is what makes the game an “opportunity to decide (..) what to do in crucial existential simulated situations” transforming the game into a “series of philosophical, ethical, emotional, and collective thought experiments” (Miranda 835). Expanding upon this, the game specifically acts as a playground for queer experimentation, allowing the player to ‘play’ gay and “simulate heavy ethical or emotional choices” in queer roleplay “without irreversible consequences” (Miranda 835). For queer individuals, the ability to experiment with their sexuality and identity in a safe space is invaluable. There are numerous choices in LiS, but I want to focus on a choice presented in Episode 3 where the player is asked to choose to kiss Chloe (Fig 3). Much like any of the major choices in the game, it is presented with a blurry filter as time seems to crumble and freeze around the player as they decide. This grants the choice a huge amount of gravitas due to the conditioning made thus far that this effect is reserved for only the most important of narrative branches in the game, however, in dialogue, it is framed as Chloe daring Max in a playful way. This tug between playfulness and seriousness perhaps betrays the exceptionality of the scene – video games, especially non-indie titles, are extremely seldom to show queer relationships. Despite this, the ability to reverse this choice and, importantly, replay it multiple times sparks an evolution of Freeman’s queer temporality. In her analysis of K.I.P., she discusses the impossibility of “physical contact across time” (13). LiS presents a playground where this contact is no longer impossible, and just like the viewer of K.I.P. could “zoom the tape backward to the money shot as often as they wanted” (1), players too can replay this queer moment endlessly - The game even remarks on this, one of the few times the game’s dialogue directly references the player’s ability to rewind (Fig 4). The literal time-travel mechanic is one that allows for queer power fantasies unseen in other media due to the player’s agency in evoking queer content on screen.

Figure 3. Life is Strange. Personal Screenshot.

Figure 4. Life is Strange. Personal Screenshot.

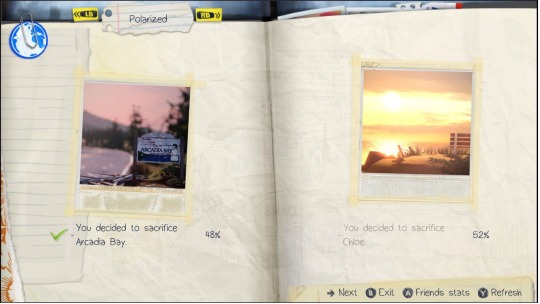

Evoking the content is poignant as, due to the staggered release of the game, each episode’s choices are statistically calculated and shown to the player, allowing both player and developer to see the worldwide consensus of choices. This leads to introspection on behalf of the player, moments of disbelief at other player’s choices or comfort in achieving consistency with others. It also “effectively” influenced “LIS’s developers in the ongoing writing of the last episodes. LIS has become a platform of cocreation and collective rhetoric.” (Miranda 836). By the time I re-played through LiS for this essay, 78% of players kissed Chloe (Fig 5) according to the online statistics shown at the end of every episode. The knowledge of this immediately comforts me, as I am confirmed in my queer sensibilities that most players are willing to allow two queer-coded characters to share an overtly gay event. It is hard to overstate how important, as a playground for queer experimentation, this statistic is for allowing a player to perhaps accept their own queer identity. However, the impact of these statistics is also dependent on if players choose the queer option. At the end of the game, a final irreversible choice is given to the player. As retribution for abusing her time travel powers, the game demands that Max decide between resetting the world back to before she gained her powers – and therefore killing Chloe, as her first use of the power was to save her life, or letting Arcadia Bay turn to rubble due to an impending hurricane caused by the constant time travel (Fig 6). 48% of people chose to sacrifice Arcadia Bay (Fig 7), a choice given the moniker “bae > bay” (Dunne 436). This Brexit-esque statistic belies the dwindled majority that the previous kiss held, which Butt and Dunne argue to be caused by the writing of Chloe as “fated to die”, which is what positions the player to feel justified in picking the “antipunk, antiwoman, antiqueer option” of sacrificing Chloe (435). In removing the ability to reject chrononormativity in this singular choice, the game removes the playground of queer experimentation. The game is no longer a safe space. Despite this, it is exceptional that so many players were so enthralled by the queer relationship between Chloe and Max that the trolley problem presented here still results in so many players choosing to save a bisexual punk rocker over every other character in the game.

Figure 6. Life is Strange. Personal Screenshot.

Figure 7. Life is Strange. Personal Screenshot.

We cannot control the flow of time. Our daily lives are stifled by chrononormativity, by the onslaught of schedules and work hours that manage our time on a macro scale. However, as queer individuals, we are uniquely positioned in rebellion to time’s linear progress through our delays in childhood and inevitable rejection of “the official destination of straight sexuality” (Stockton 7). Through reading and play, we can experience realities that reject chrononormativity and assign a queer temporality to imagined realities, which in turn leads to experimentations with queer identity. In Member, by using analepsis and other chrono-breaks, the reader’s sense of time is disturbed by continual references back to “hours or even minutes prior” that may have already “been touched upon previously” (Seymour 306). This queers the narrative, alongside Frankie’s continual name-changes which show her performing new identities to find a self she feels “included” in (McCullers 59). LiS takes the principles of performance and creates a playground for queer expression through the technological capabilities of video games in allowing for interactivity. Players are given narrative choices and control over time, allowing them to play as a bisexual teenager through her coming of age. The mesh of time travel, a literal refusal of sequential time, with queer interactive narrative gives the player a safe space to both rewind any choice without consequences and to replay any scenes for enjoyment. The game utilises interactivity as an inherently queered way to experience a narrative, one which evokes co-creation with a world of players through online statistics for every choice in the game. Queer temporality is relished in until the final moment whereby the game removes the queer safe space it establishes and forces the player back into real time. However, in allowing the player to play queer, the final choice of sacrificing queer romance over thousands of digital lives is made significantly harder. In the end, while “bae > bay” is not the winning choice, it is life affirming that so many players became so invested in a queer romance that the outcome was as statistically meaningful as it was.

Works Cited:

Butt, Mahli-Ann Rakkomkaew, and Daniel Dunne. “Rebel Girls and Consequence in Life Is Strange and The Walking Dead.” Games and Culture, vol. 14, no. 4, SAGE Publications, 2019, pp. 430–49.

de Miranda, Luis. “Life Is Strange and ‘Games Are Made’: A Philosophical Interpretation of a Multiple-Choice Existential Simulator With Copilot Sartre.” Games and Culture, vol. 13, no. 8, SAGE Publications, 2018, pp. 825–42.

Freeman, Elizabeth. “Introduction: Queer and Not Now.” Time Binds, Duke University Press, 2020, pp. 1–20.

Life is Strange. Steam Version, Square Enix, 2015.

McCullers, Carson. The Member of the Wedding. Penguin, 1962.

Pötzsch, Holger, and Agata Waszkiewicz. “Life Is Bleak (in Particular for Women Who Exert Power and Try to Change the World): The Poetics and Politics of Life Is Strange.” Game Studies, IT University of Copenhagen, 2019.

Seymour, Nicole. “Somatic Syntax: Replotting the Developmental Narrative in Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 41, no. 3, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009, pp. 293-313.

Stockton, Kathryn Bond. “Introduction. Growing Sideways, or Why Children Appear to Get Queerer in the Twentieth Century.” The Queer Child, or Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century, Duke University Press, 2021, pp. 1–58.

#life is strange#LiS#max mayfield#chloe price#pricefield#essay#video games#analysis#games#literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pokemon Yellow, Furries, and Interactive Cuteness

Cute is powerful. Commercially and critically, cuteness has garnered incalculable success in today’s consumerist Western society. This extends to various franchises and media, from animated film to video games. One such franchise which utilises the power of cute through its multimedia empire is Pokémon, a worldwide success which is currently the highest-grossing media franchise of all time (“Top Media Franchises”). To achieve this lofty height, Pokémon has been reliant on the aesthetics of cuteness in all its media. This essay will look at the impact of interactivity on the appeal of cuteness, prodding at how Pokémon’s success is borne through a combination of cuteness and interactivity with cute objects which inspire “emotional attachments to imaginary creations” (Allison 382). As such, this essay will focus specifically on the video games arm of the Pokémon franchise. I first wish to discuss the design philosophies which spawned the close relationship the game medium has had with cuteness since its inception. Early computer systems were too limited to produce detailed graphics, which meant relying on abstraction. Cute, however, is often simple, making it a viable principle to design game characters around. This inherent tie between video games and cuteness naturally led to a taste in game players for cute characters, one which has persisted to this day despite technological advancements allowing for photorealistic graphics. Secondly, narrowing the lens to purely the Pokémon video games, this essay will examine Pokémon’s personal relationship with cuteness and the impact of its interactivity. Through hours of play and dozens of different titles spanning over three decades, the game series is designed to evoke a sense of longing and care for the Pokémon creatures that players catch and bond with through the games. Pokémon Yellow Version will be used as a case study for the various game design innovations which developers Game Freak made to enhance the game’s cuteness, and therefore add to the relationship between player and character. This included having Pikachu follow players outside of battles and react to various story events. Lastly, I will discuss the Pokémon franchise through the context of the furry fandom, a large worldwide group of people who craft their identities around anthropomorphic animals (which include Pokémon). Furries mimic and recreate Pokémon characters in real life, often creating OCs, or original characters, which represent themselves through the cuteness of Pokémon designs. Cuteness becomes identity; a vision of oneself which through years of interaction and bonding inspires people to spend thousands on costumes to briefly become those self-same cute monsters.

Despite its relative modernity compared to other media, video games have evolved substantially across the past five decades of their prevalence. Technology has allowed games to create entire 3D worlds that are inhabitable in virtual reality, yet the origin of the artform stems from basic lines and pixels on a 2D plane. The limitations of early games in the 70s and 80s created a symbiosis with the ‘cute’, a necessary marriage birthed from the need to represent characters with such little power to render detail. The consequences of these limitations led to the birth of many different memorable gaming characters: Mario, Kirby, Sonic, Pacman etc. The general connective tissue with these characters is their art style. Derived from the ‘chibi’ aesthetic that was popular in manga at the time, these Japanese created games all featured characters with features often cited as “essential” to the creation of a cute character. Take Kirby, a pink circle with eyes (fig 1). The properties of Kirby’s design are derived from the limited canvas video games offered, which also happen to mesh with the design principles that make designs cute – “round, without bodily appendages, (…) non-sexual, mute” (Cheok 298). The list expands beyond this, yet most traits associated with cuteness are also fundamentally simple, which makes them easier to render for low-tech hardware. With Kirby, the intent was clearly to make a cute character, yet this principle applies to characters that aren’t necessarily meant to be cute. Pacman is just a moving pie-chart in the arcade game, a vehicle for the game’s mechanics. However, this necessity to make Pacman look like he’s eating using so few pixels also happened to be a perfect companion to making a marketable, cute mascot. By using cute character designs, developers can create characters that are easy to render and memorable, while publishers are able to market games through their appeal as cute objects – both in advertising for the games themselves as well as merchandising. This relationship was spawned exceptionally early in the lifespan of video games as a form of commercial media, and that ensures a consumer market that associates video games, at least partially, with the aesthetics and tastes of cuteness.

Taste in video games and in the cute, then, have been nurtured concurrently in consumers. To speak of taste is to speak of many systems which effect the enjoyment of a vast array of subjective activities and media. It is a vast subject, one which can only be touched upon in a limited capacity here, yet I think it is important to discuss what taste in video games and taste in cute says about the medium and its consumers. Hennion describes tastes as being “lived by each but fashioned by all, (…) a history of oneself permanently remade together with others.” (103). This description is pointed in its assertion that taste creation is a collaborative, social enigma. Tastes are ever shifting with the tide of a wider society, through media and through friendships. One can receive a taste for something or give that taste to someone else. Taste inherently becomes a tool of influence, a way to define a person and change those definitions over time and over different experiences. This makes taste incredibly powerful in a capitalist society that is fuelled on the ability to sell anything and everything to a consumer. New technologies and media, such as video games, are perfect vehicles to create more consumers by giving them a taste for something new, something expensive, something profitable. Cuteness, in this regard, then becomes the tool by which video games can achieve mass appeal – a way to paint over the foreboding and intimidating technologies which produce the games we play. Focussing on Japan, the region most closely associated with cuteness and technology’s intermingling, it’s hard to ignore that “many cultural transformations in Japan are essentially obsessed with technology” (296). This includes traditional video games, such as Mario, and gadgets and devices such as the Tamagotchi that fall somewhere between traditional toys and video games. These devices transformed consumer cultures in Japan, and their relationship with cuteness assured that cute sensibilities were ‘in taste’, popular and ever-present. The cute or “Kawaii” is irrevocably associated with “the technological landscape of Japan” (Cheok 298). I would argue that through the influence and popularity of games, the world outside of Japan also associates the cute with technology, if less severely. Pokémon is the perfect example of this.

Appearing in the late 90s, Pokémon made a clear impression on the gaming market. Quickly becoming an astronomical success, it was impossible to avoid the multimedia deluge of Pikachu laden content that graced both the West and Japan. The games are about collecting and fighting a multitude of Pokémon creatures, 151 in its initial release, through a role-playing adventure across a world inspired by the Kanto region of Japan. It follows a basic RPG formula of a grand adventure spanning tens of hours, all the while your characters gain experience and grow stronger through the course of the journey. Uniquely compared to other popular RPG franchises like Final Fantasy, however, is the fact that Pokémon is set in an urban setting not dissimilar to the modern world we live in. Characters in the game have televisions, while large shopping centres and gambling parlours are found in the region’s bigger cities. It is a modern world infused with Pokémon creatures. By making the world of Pokémon so closely fit our own, players can better relate to the events of the game and imagine our own world filled with cute creatures that roam around. It makes it easy to imagine interacting with Pokémon. “Bringing these characters out of the screen, so to speak, triggers the fantasy of enveloping them into everyday life” (Allison 385), and such, the marketing machine would pump out endless supplies of merchandise specifically to sell these cute creatures to consumers who had played the games and become attached to their Pokémon. How could they not when the game design is so catered to making sure players build an intimate relationship with their Pokémon? The game opens with a choice between three Pokémon to be the player’s first. The player is shown a portrait of the potential choices and can therefore make an instant connection with them based on their cute appearance. Given the game only lets you take six Pokémon with you at any given time, and that the starter Pokémon you choose is designed to be one of the strongest, it is likely that the player will keep this Pokémon in their team for the whole game. Growing with them, leading them to victory or defeat, hearing their cries of pain or success. This ability to influence these creatures, interact and play with them, enhances the relationship between video game character and player. “Cuteness here involves not only interaction with a virtual creature, but also its creation and maintenance.” says Anne Allison, and in maintaining this creature, they gain “pocket intimacy”, a “portable companion with whom they can interact with where they go” (391). It is the mingling between cuteness and the interactivity of video games that makes this possible, and I would extend Allison’s idea to its logical conclusion: this interaction with cuteness leads to a desire for people to take the Pokémon out of the game, and into their physical world through the purchase of merchandise.

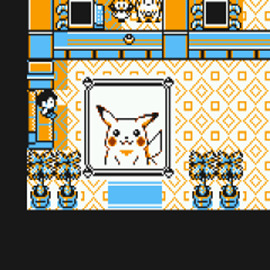

Many of Pokémon’s most effective ties between cuteness and interactivity were present since the first trio of games were published, yet Nintendo never stopped adding more cute creatures or ways to bond with them virtually. Over the past three decades, Pokémon has released dozens of games across eight generations, a term used to describe when the franchise adds a new set of Pokémon to the roster – we are close to reaching over one thousand. The second game in the series, an add-on to the original trio based on more heavily on the wildly popular anime series that was releasing at the time, was Pokémon Yellow Version. Still in the first generation, this game made clear the direction of the franchise and its commitment to enhancing the bond between player and merchandisable product. The most immediate change was to the branding – while the original games featured a choice between three starter Pokémon, this version would only allow players to start with the eponymous Pikachu, just as in the anime TV show. Players are immediately met with Pikachu’s visage from the box art to the title screen (fig 2). The Yellow Version in the games title obviously referring to Pikachu’s immense surge in prominence. The cute mascot of the wider Pokémon universe had made its mark on the games and would come to define the entire experience. As a mascot, “Pikachu was chosen for a number of reasons: its bright yellow color, memorable chant (…), unforgettable shape, and, most importantly, its cuteness which could attract just about anyone.” (Allison 385). These aspects of the character were defined in concept art and the anime, yet not apparent in the original games, which used a far pudgier version of Pikachu (fig 3) compared to the sleek design used in later media (fig 4). Pikachu’s power of cute would tie with Yellow Version’s new game mechanics to create an experience that gave personality to Pokémon creatures. Pikachu would now follow the player in the world of the game, rather than being contained in a Pokéball like all other Pokémon. This would allow players to always see Pikachu, not just in battle, and feel the intense sting when a poor choice results in them being incapacitated and disappear from the game screen. Pikachu even reacts to story events, making varied cries and noises voiced by Ikue Ōtani, their voice actress in the anime (all other Pokémon use synthesised cries). One can talk to Pikachu to see how they are feeling, and they’ll react with a variety of different animations (fig 5). The ability for the player to interact more closely with their Pokémon further sells them as companions to bond with instead of tools to win battles and complete the game with, and it is their cuteness which allows this intense bond.

Pokémon was a smash hit, in no small part due to the marketable power of cute anthropomorphic animals. The choice to use animals as a basis for the design of most Pokémon makes sense, given that animals in the real world are both cute and ferocious – necessary features when creating a game about fighting and raising creatures. The appearance of many of these Pokémon would mimic the design sensibilities of kemono, a Japanese concept which merges human features with animals. This is generally comparable to the concept of furries in the West, a widespread fan culture based around the creation of anthropomorphic artwork. Pokémon such as Lucario (fig 6) or Zeraora (fig 7) are extremely popular within the fandom due to their clear anthropomorphic design sensibilities. While Pokémon does not market directly to the furry fandom (the demographic, despite consisting of millions, is neither mainstream nor respected), these designs do inspire an amount of fan creativity and relatability that goes beyond what the games can offer independently. Essentially, furries take the idea of Pokémon, of being able to play with and bond with different cute creations, to the real world by crafting fursuits and fursonas based on these popular designs. Furry as a sub-culture is engaged with “fairly idiosyncratic fandom-related interests: they construct fursonas – anthropomorphic animal-themed identities to represent themselves.” (Reysen 1). As such, by creating fursonas that are based on Pokémon, furries mesh their constructed identities with what they perceive these Pokémon designs represent. Oft times, this is forged from a desire to become these cute creations, if only for entertainment and recreational purposes. It is an extension to the desire to own “iconized (…) commercial goods” which Pokémon appear on, such as “T-shirts, bookbags, calendars” (Allison 387) etc. The purchase of these products stems from a desire to bring Pokémon creatures into the real world – furries conclude that line of thinking. As such, intricate and expensive fursuits are created of these designs (fig 8 & 9) that allow furries to play as their favourite cute Pokémon in the real world. This extreme length to deepen the bond between player and product reminds me of Annemarie Mol’s musings on taste in food, where she states, “tasting cannot be done from a safe distance, it requires bodies quite literally to mix with this rest of the world.” (279). I would argue the intimacy of tasting here, the requirement of vulnerability, of openness to mix with others, is quite apt in describing the eagerness with which furries bring the world of Pokémon into the real and allow their cuteness to inspire them creatively.

The emergence of Pokémon within the furry fandom throughout the 2000s has been enormous, and this is interesting as fursonas are often representations of a person’s identity. By creating this personal identity around a marketable and copyrighted design, the case study brings up some concerning questions around the power of capitalism and consumerism in controlling a consumer’s ‘ideal’. Fursonas are “alternate identities” (Reysen 1) and are often constructed as “psychologically or behaviourally similar” to the person, essentially an “idealised version of themselves” (6). Through effective design, these Pokémon designs have become a part of certain furries’ ideals, which demonstrates the power of cute to impact the tastes and personalities of people around the world. I hesitate, however, to deride this morally – many capitalist products are personally impactful to all manner of people and become part of their identity (favourite films etc). It is important to keep in mind that the most integral part of the furry experience is the ability to self-curate personality and aesthetic traits into an alternate self. Pokémon creatures are therefore used as a base to build upon; add personal flair to. Cuteness is the ideal in itself; Pokémon is the vehicle by which people can attain it.

Virtual cuteness is ever-present in today’s consumerist society. From the early beginnings of video games as a commercial medium, technological restrictions on the creation of games have assured a clear connection between the aesthetics of cuteness and video games. Early gaming devices did not have the ability to render graphics with high fidelity, meaning games would rely on simplistic graphics which naturally mesh with the principles of cuteness. Cute is often simple, as seen in designs like Kirby. This early connection between cute and technology meant that the taste for video games was tied with a taste for cuteness in players. “Consumption is speedy, and the threshold of boredom is a slender line, each Kawaii character battles for supremacy and then survival.” (Cheok 299). Hence, the success of franchises like Pokémon relies on the “supremacy” of their cute mascots. Pokémon games are a perfect combination of cuteness and interactivity. They take the traditional principles of RPG video games and transcribe them into a modern day setting with cute creatures around every corner. Players grow and bond with their Pokémon, both through success and failure, through tens of hours. Pokémon Yellow Version demonstrates some of the evolution of the Pokémon franchise, showing a further reliance on the cuteness of Pikachu as a mascot and a design focussed on bonding with a character with a clear personality. Lastly, I have discussed here the impact of Pokémon and cuteness on the furry fandom, a group of people who craft alternate identities through donning the appearance of anthropomorphic animals. Furries recreate Pokémon in the real world through custom fursuits. This brings Pokémon closer to the real world and demonstrates the impact of cuteness in pop culture on groups of people. Pokémon, and their cuteness, allow people to adopt their designs as a base for imprinting their own ideal identities onto. The taste for cute, driven to the masses by the vehicle of a multi-billion dollar franchise.

Works Cited

Allison, Anne. “Portable Monsters and Commodity Cuteness: Pokémon as Japan’s New Global Power.” Postcolonial Studies, vol. 6, no. 3, Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2003, pp. 381–95.

Cheok, Adrian David, and Owen Noel Newton Fernando. “Kawaii/Cute Interactive Media.” Universal Access in the Information Society, vol. 11, no. 3, Springer-Verlag, 2011, pp. 295–309.

Guttmann, A. “Top Media Franchises by Revenue 2021”. Statista, 18 Aug. 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1257650/media-franchises-revenue/

Hennion, Antoine. “Those Things That Hold Us Together: Taste and Sociology.” Cultural Sociology, vol. 1, no. 1, Sage Publications, 2007, pp. 97–114.

Kirby Sprite. Retrogamer, https://www.retrogamer.net/retro_games90/kirbys-adventure/

Lucario Official Artwork. Pokemondb, https://pokemondb.net/pokedex/lucario

Mol, Annemarie. “GOOD TASTE: The Embodied Normativity of the Consumer-Citizen.” Journal of Cultural Economy, vol. 2, no. 3, Taylor & Francis Group, 2009, pp. 269–83.

Pokemon Blue Version. Gameboy Version, Nintendo, 1997.

Pokemon Yellow Version: Special Pikachu Edition. Gameboy Version, Nintendo, 1999.

PriamWolf. “Lucario Fursuit.” Furaffinity, 2017. https://www.furaffinity.net/view/20139678/

Reysen, Stephen, et al. “My Animal Self: The Importance of Preserving Fantasy-Themed Identity Uniqueness.” Identity (Mahwah, N.J.), vol. 20, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–8.

Willowcookie. “Zeraora Full Testfit.” Furaffinity, 2018. https://www.furaffinity.net/view/26076982/

Zeraora Official Artwork. Pokemondb, https://pokemondb.net/pokedex/zeraora

#pokemon#cuteness#cute#furry#anthro#game critique#games#video games#nintendo#essay#analysis#game design

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fallout, Media History, and Nostalgia

Nostalgia is weaved into the DNA of video games. Through their “active and participatory nature”, games can reinforce a player’s “memories of past media” and gain a more “powerful satisfaction of nostalgic desires through nostalgic play” (Sloan 532). It is this inherent interactivity within the medium that allows games to foster nostalgia at such an exceptional rate compared to other mediums. Every playthrough is different, personalised, and memories are formed through the unique ways a player may experience any given game. The Fallout series of games synthesise gaming’s penchant for nostalgic sensibilities with a narrative and design devoted to nostalgia for a lost era. Nostalgia for 1950s America is rampant in the Fallout franchise, from tube televisions, clunky automobiles; nuclear families to the height of McCarthyism. The games largely take place 200 hundred years into a post-war nuclear wasteland in a theoretical future birthed from the atomic craze of the real 1950s. This essay will focus firstly on the wider Fallout franchise. The design of the American wasteland, with its deluge of pre-war artifacts littering the scenery of a dead American landscape, shows how a fantasy of nostalgia can be crafted through the mixture of sci-fi and fantasy elements with accentuated 1950s iconography. It is this scattering of iconography that inspires players to be nostalgic for periods they likely have never lived through; the franchise manufactures a nostalgia for elements of both itself and its inspiration. Through its radio system, which constantly plays 1950’s licensed music while one explores the wasteland, players inevitably become nostalgic for the music and the time they represent as well as the world of Fallout itself. The second half of this essay will focus entirely on the Fallout: New Vegas (F:NV herein) entry into the franchise, which incorporates elements of nostalgia into its narrative design. Factions in the game, societies which try to rebuild America, are all based on and flawed by old-world ideologies. Caesar’s Legion is unabashedly stuck in rhetoric fit for the Roman Empire, while the New California Republic attempt to bring back American democracy to the wastes. This sense of the past persisting in the present is woven in into many quests in the game, which showcase the world’s reliance on nostalgic technologies of the past. Lastly, I will discuss why the game is so nostalgic: no crisis is greater than nuclear fallout to inspire nostalgia, and F:NV builds its narrative core around critiquing the integrity and longevity of the past and nostalgia for it. The question Fallout posits: why can nostalgia survive a nuclear apocalypse?

Nostalgia is a complicated term. It evokes bittersweet memories of the past, yet nostalgic feelings don’t necessarily rely on any true experience. One can be nostalgic for a past event, be it lived or experienced through media, or they can be nostalgic for their time with a piece of fictional media. Niemeyer puts nostalgia as a “way of living, imagining and sometimes exploiting or (re)inventing the past, present and future” (2). This definition distances nostalgia with its partner-in-crime, the past, to instead state its potential for invention. Making something new based on the past. Essentially, creating a fantasy of nostalgia. It is this kind of nostalgia, one for a fantasy based on a real time-period, which Fallout breeds through its game design. Despite all the games taking place in a fictionalised universe drawing “inspiration largely from Atomic Age science fiction literature and cinema” (Chandler 52), a world where the communist China initiated nuclear armageddon, they evoke a clear sense of nostalgia for the 1950s. There are innumerable references to 1950s America, albeit through the lens of an alternative history. Within Fallout 3, Washington D.C is transformed into the ‘Capital Wasteland’, with the roads and landmarks around this region of the world lovingly recrafted in all its post-apocalyptic glamour. The National Archives building somehow manages to evoke American exceptionalism in the face of utter nuclear defeat (fig 1) and the new world spawned by the atomic bombs fail to paint over the remaining dredges of American life. Games are a “medium capable of evoking long-gone eras” (Makai 2), but poignantly they are also a medium capable of transforming long-gone eras. Fallout’s nostalgic sensibilities are born out of a fantastical version of the 1950s, yet it manages to find ways to anchor players in its “altered world” (Stang 6). This nostalgia does not “necessarily evoke a longing for a real or imagined past”, and rather “functions as parody, satire, and critical commentary” (Stang 11). Stang points to the role of food in Fallout here, stating the fantasy Nuka-Cola drink (an obvious parody of Coca-Cola) functions as “critical commentary on the fictional (…) American culture that produced them but also on the real-world post-war American culture the games are parodying.” (11) The presence of food like this (including Sugar Bombs and InstaMash) ties the game to a very real American culture of unregulated food processing and advertising in the 1950s. These artifacts of the old-world are found throughout Fallout and act as reminders of an America that has passed, creating a nostalgia for Fallout’s fictional past as well as the real past it is based on.

While Fallout creates a world where nostalgia can persist after a nuclear war, it also manufactures nostalgia for the players of the game. In a world where the primary demographic for video games does not align with a demographic of people who lived through the 1950s, it might seem strange to commodify the era into a sellable product. Often, games use a “commodification of consumer nostalgia for a range of historical and mediated referents as a means of enhancing (their) appeal” (Sloan 531), and neither the 1950s as a historical moment, nor the Atomic Era sci-fi literature Fallout is inspired by are particularly prevalent in the minds of the franchise’s young demographic. However, Fallout is focussed on manufacturing this nostalgia for the 1950s through a persistent and iconic reappropriation of 1950s art and culture into the world of Fallout for players to grow attached to. Primarily, this is achieved through the game’s radio system, which allows players to tune into radio stations which play era-appropriate Easy-Listening and Jazz tunes at nearly every moment of the game’s run time (if the player so chooses). These songs evoke what Niemeyer calls a “false nostalgia: a pleasure-seeking yearning for former times that we have not, in fact, lived” (9). The disconnect between the dead world players traverse in Fallout with the often cheery and memorable radio songs makes the audio stand-out, and the songs’ overwhelming prevalence in the world make them impossible to ignore or forget. A generation of young adults were introduced to a plethora of 1950s songs through Fallout, therefore manufacturing a nostalgia for these records and the times they represent – notably, easier times, given the player naturally compares them to the apocalyptic one they are playing. Searching for any of the franchise’s songs on YouTube will result in Fallout-oriented uploads as the first hits. Jingle Jangle Jingle by Kay Kyser has sixteen million hits (“Fallout New Vegas Soundtrack – Jingle Jangle Jingle”) whereas the best performing non-Fallout branded video has less than two million (“Kay Kyser – Jingle Jangle Jingle”). Ironically, the actual version of the song used in F:NV is in the latter video, showcasing how much power a brand name can have to mislead a consumer, which is both hilarious and depressing. This trend showcases how important these games were in creating a nostalgia for artifacts of the 1950s, embedding an adoration for the era in players who would never have lived through it.

Figure 1. “National Archives.”

Thus far I have discussed two kinds of nostalgia: fantastical nostalgia, or the nostalgia for imagined worlds, and manufactured nostalgia, creating nostalgia for real time periods within people who had not lived through said time. Another nostalgia which Fallout creates is self-nostalgia. Niemeyer describes this as media being “technological objects of nostalgia” with how they can “become nostalgic themselves” (130). This sentiment is applied directly to video games, which have reached “a stage in their history where, like films, they have “become their own objects of nostalgia”” (Makai 2, qtd). What both these scholars touch upon is the ability for media to be self-nostalgic. I would argue this is largely due to the longevity of franchises in modern media consumption. Coupled with the ever-expanding technological prowess of media, especially video games, where games from ten years ago look archaic compared to what is released today, it is hard not to feel nostalgic for games that have come before. Fallout is especially apt as a case-study for this, as the franchise has spanned over twenty years and jumped from 2D to 3D presentation in the process. The original Fallout game was released in 1997, solidifying various franchise staples such as the Nuka-Cola drinks that serve as health regenerating items or the game’s penchant for 1950s pop music. So rich was the nostalgia for this game by the time Fallout 3 came out in 2007 (many years after Fallout 2 was released in 1999), that the announcement trailer (“Fallout 3 Teaser Trailer”) for the game used similar cinematography and another ‘The Ink Spots’ song as in the intro cinematic for the original Fallout (“Fallout Intro”)to accompany the reveal. The franchise’s revival was marketed based on consumer nostalgia for the original games and littering the game’s world are constant reminders of the franchise’s beginnings, despite the games going in radically different dimensions (literally). Returning characters from the original Fallout games, like Harold the talking tree, make even narrative aspects of the game a pastiche on the originals. At every corner there is a reminder for the player that the game they played a decade ago has been remade in stunning quality. The developers have utilised “nostalgia to create emotional bonds with virtual worlds that span across generations” (Makai 12). These emotional bonds hence create loyal customers who continue to buy into the franchise to continually feed their nostalgia for what they played earlier in life, though with the added benefit of technology’s obsession with progress.

How, then, does F:NV act as the perfect case study for nostalgia out of this franchise consisting of dozens of games? To explain the nostalgic principles that govern the game, I must first divulge into an explanation of the narrative of F:NV. The game begins as any other Fallout title – you take control of a blank slate character who is thrust into the post-apocalyptic wasteland. Unlike other Fallout media, however, F:NV is a story of the factions which strive for power within the Mojave. To the east is Caesar’s Legion, a group of invaders led by Caesar to take the Hoover Dam and therefore control the flow of electricity to the various settlements in the Mojave. The group, as their leader’s name suggests, is based on the Roman Empire, right down to their soldiers holding ranks such as ‘centurion’. They strive to bring back the savagery of the Roman Empire, taking people as slaves and ruling with an iron fist. The NCR, however, are the current holders of the Hoover Dam and mean to bring back American democracy to the largely lawless wasteland. They, as unsubtly as the Legion, are trying to return the world to pre-war sensibilities, even trying to assert their own currency based on American bank notes to replace the current standard of bottlecaps. Lastly, Mr. House is a solo operative who controls the New Vegas strip, the last surviving city-size area in the Mojave. He wishes to bring peace to the Mojave through a dictatorship, though this is spawned from a sense of ownership over the area, as he’s a pre-war survivor who invented a way to sustain his life and retain control of the Vegas strip over centuries. The player must decide which factions to support in their attempts to bring various elements of the past into the present, or merely choose to go their own way. Throughout the game’s narrative, the player discovers the pros and cons of each faction, yet the essential element of this conflict is that even after an atomic war, the past cannot help but be repeated. Nostalgia for the past, the lingering fragments of old cultures and societies, have inspired countless people in F:NV, often misguidedly. Even the seemingly morally correct faction is poisoned by their nostalgia. The NCR are homophobic, as noted by various characters, and starve their workers through low pay and an (in)equal distribution of resources across their famers. The main quest in F:NV is prodding at how nostalgia survived an apocalyptic crisis, and the ways its children have turned to the past to repeat its mistakes.

Fallout games are not linear. They operate by giving the player full access to a large open-world which they can explore in any order at their leisure. Hence, the player can stumble upon many side-quests which deal with nostalgia in their own ways. Many of these are humorous in their intent, yet the core themes which are repeated relate to nostalgic feelings. This open-world design philosophy mimics how history is “broken into pieces, to be reconstructed together by the player only should she wish to sift through documents or actively seek out knowledge of the past.” (Chandler 59). I would extend this sentiment past the open world gameplay of stumbling upon artifacts of the past and into a player’s experience with stumbling upon the people inhabiting the Mojave and their relationships with the past. One of the first quests a player can find in F:NV involves fixing a barmaid’s radio in the small town of Goodsprings. The radio, as previously mentioned, is a tool to rebirth the 1950s into present time. However, the radio also acts as an important tool for both the player and the game’s characters to hear about what is happening in the Mojave through the radio host Mr. New Vegas. Voiced by Wayne Newton, a real entertainer in Las Vegas, Mr. New Vegas’ news reports are delivered in a crooning voice reminiscent of old radio broadcasts, in part due to the purposefully low-quality playback. Essentially, the news of the present is delivered through technology and performance sensibilities of the past, and the citizens of the Mojave are reliant on this past to assure their safety in the deadly wasteland. Another quest which reaffirms this reliance on the past is an extensive series of stories relating around a group of Elvis impersonators who are held up in a decrepit School of Impersonation in the Vegas Strip. Called the ‘Kings’, this group talk and behave in ways they have learned to through reading the last existing remnants of Elvis’ legacy, largely misinterpreting them due to their lack of comprehensiveness. Their constitution reminds me of Van der Heijden’s analysis on thoughts around memory and the past, where memory is approached as an “active, embodied, performative, ritualised, and highly contextualised process” (105, emphasis my own). The Kings have decided to perform a role based solely on their impression of a past they did not live, actively deciding to bring back what they understood as Elvis’ legacy to bring peace to the Vegas Strip via their role as defenders of the poor.

I wish to briefly discuss the core concept at the heart of Fallout. The idea that nostalgia is a ‘child of crisis’ is self-evidently relevant to a franchise so dedicated to portraying elements of the past and its impacts on the present in an atomically ruined America. The very setting of the games, and the fact that anyone survives at all, shows how persistent nostalgia is theorised to be by the developers of the game. That an America exists is miraculous, yet the intriguing idea is that the America that survives is so reliant on the America which came before it. Despite so much culture and history being irrevocably destroyed, factions and people in the Fallout universe are hell-bent on recovering what they can of the past and living by the creeds that are detailed there, regardless of the intense irony staring everyone in the face: repeating and taking from a past which resulted in a nuclear apocalypse is probably only going to result in another nuclear apocalypse. One complicating factor within the Fallout universe is that people who lived before the apocalypse still survive, both through technology (as with Mr. House) and through radiation poisoning turning them into ghouls. That the past cannot only survive in documents and monuments, but also in living people, further displays Fallout’s insistence that history, memories, and nostalgia cannot be destroyed via any crisis. Instead, nostalgia is rebuffed through the crisis, with entire factions and civilizations who make doctrines of the past their personal dogmas.