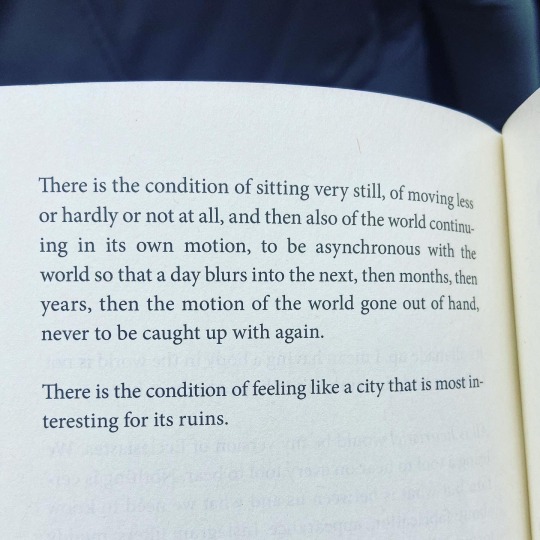

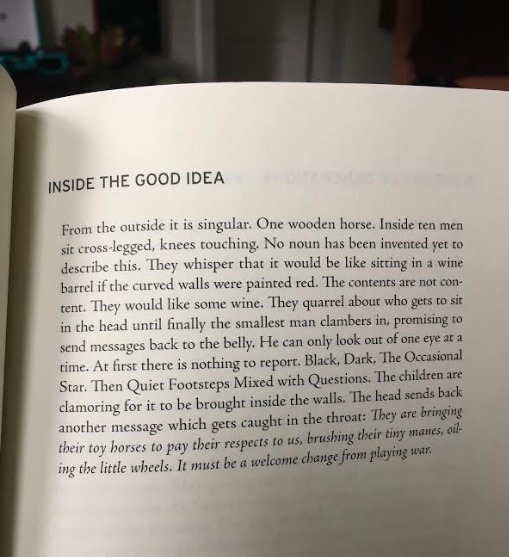

Text

Favorite Reads of 2023

As a reader, I think of myself as slow to turn toward fiction, but this year started off with stunning story after stunning story, thanks to writers like Emily St. John Mandel, Rivka Galchen, Amal El-Mohtar, and Max Gladstone. Miriam Toews' Fight Night made me weep on a train from Edinburgh to Glasgow; Josephine Tey's mysteries made me chuckle from Glasgow to Edinburgh. I wandered slowly but steadily with Susanna Clarke's Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norell throughout the year and I read Timothy Moore's short stories in one sitting and then started them over the next week. Grateful for these writers who move me in so many ways, and of course I have some poetry and nonfiction favorites!

1. Timothy Moore's exciting debut short story collection, I Will Teach You Retribution, is perfection. Its humor and absurdism and poignancy remind me a bit of George Saunders (CivilWarLand in Bad Decline), a bit of Aoka Matsuda (Where the Wild Ladies Are), and excitingly and obviously of Tim. If you aren't moved by the plight of a people-eating giant's quest for justice against himself, or a side character/ex-lover's desire to have her own transformative character arc, or a girl's use of social media to be popular, even though dead—or at least by the empathetic way Tim writes these characters and the wonderful crafting of his sentences—your heart may have stopped. An unexpected love-at-first-paragraph. Ten out of ten best use of exclamation points.

2. In Scared Violent Like Horses, John McCarthy writes about childhood in rural Illinois, absent parents, fistfights with friends, and flyover states, but mostly he writes of people in a way that sees their empathy and value. I read this while feeling a little lost and heartsick, and these poems wrapped around me and reminded me of what I love best. This is not to say that I saw my journey reflected back at me, but that lyric can offer the comfort of a song, that poetry lets you sit in a space of experience not answers, and that you can endure so much hardship and still emerge with tenderness. John’s writing is thoughtful and vivid, graceful and grace-giving. “But I’m not sure why we would expect dreams to make sense, when our waking lives so often fail to observe narrative convention,” he writes. And later: “No place is sad if you stay long enough.”

3. How to Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone is an abundantly written book, composed of letters between Red and Blue, two agents on opposite sides of a time war, one side more organic and one more tech-driven. It’s surprising and inventive in its world building and sweet on the act of letter writing. A love story that gushes to the beloved, overflowing without feeling cheesy. I read this on a beach in Mexico, against the bluest backdrop with the reddest sunrises.

“I want to tell you something about myself. Something true, or nothing at all.”

4. Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility was satisfying and unexpected, even up to the last line. As in her other books, she weaves together stories of multiple characters, gently nudging them more and more into each other’s orbits as the book draws to a close. This book feels higher stakes or maybe has more imaginary elements than The Glass Hotel, which I thought was nice but forgettable—I prefer the bigger “what ifs” in my fiction. But her writing always feels like a gliding, with these lovely details that linger. Here, there's an untouched forest in Canada and a shabby moon colony with a river reflecting the darkness of space. A writer of post-apocalyptic fiction, now a mother and turned off her own ideas. (It’s interesting to hear from an author who wrote a wildly successful novel about a global pandemic, then lived through one, and wrote a second pandemic-related novel in which much happens very differently.) The question of simulation a backdrop, the difference between knowing something in the abstract and the experience of it, how we come to the knowledge we have and the gestures we know we must make. All of it so well done and a pleasure to read.

5. The overarching frame of On Dreams by Maureen Thorson is the author's diagnosis of a rare eye disease that causes blind spots and some of Aristotle's absurd theories, such as how a mirror turns red when a menstruating woman looks into it. From there, in essays composed of short, aphoristic lines, Thorson explores what is reality and truth, how we know what we know, the illusion we have of control, and why we turn to writing and narrative. It's funny and smart, weaving in notes from her broad reading, and poignant in the leaps and turns it takes from line to line.

6. Border Vista by Anni Liu is composed of these lovely memory poems—atmospheric. She writes about emigrating to the US while young and being separated from her dad and grandparents with uncertain status, about relationships and home and dreaming in her nonnative language. The poems read almost memoir-like, back to back. The settings simple: a walk in the woods or market, hearing a piece of news or sitting in a movie theater, with some startling insight dropped upon the reader, the reader unaware even that she was building toward something. The lines below have echoed in my head the whole year, naming a longing so ingrained I didn't even know it was there:

“Crossing a deer-shaped patch of earth,

I come back to the edge

of an ancient sadness of being

just one thing”

7. I really enjoyed diving into the oeuvre of Josephine Tey this year, and in particular I don’t think I’ve read anything quite like her Daughter of Time, a unique take on both the histories and mysteries genres. Her Inspector Grant, laid up in a hospital and bored, takes on an academic investigation of the slander against Richard III, infamous for killing his two nephews—the Princes in the Tower—to remove any rivals to the throne. Despite the fact that Grant is initially driven into this mystery because Richard’s face just "looks" more like a judge’s than a criminal’s (classic Tey ridiculousness), Tey makes a compelling case for his innocence. Grant and his “looker-upper” (researcher) friend take a policeman’s approach to the unresolved mystery, looking at the whereabouts and motivations of the people involved instead of what they say, and keeping an eye out for any breaks in the patterns that suggest foul play. For a book whose main action is two men talking about historical accounts, it’s surprisingly gripping and convincing (although my own knowledge of British history is spottier than a spotted dick pudding!).

"Give me research. After all, the truth of anything at all doesn't lie in someone's account of it. It lies in all the small facts of the time. An advertisement in a paper. The sale of a house. The price of a ring."

8. When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities by Chen Chen is a book that “wants to believe it’s always possible / to love bigger & madder” and a poet whose “job is to trick adults / into knowing they have / hearts.” There's so much unbounded joy in these poems, even when writing of the sadness of having sadness or of the painful rejection by his mom for being gay or by fellow Americans for being Chinese. He writes rooted in a strong sense of self, which means his poems overflow with brightness, humor, and triumph.

Some possibilities:

“I want to be the Anti-Sisyphus, in love / with repetition, in love, in love. Foolish repetition, / wise repetition. I want more hours. I want insomnia, I want / to replace the clock tick with tambourines.”

“I am … an elegy that has felt light, the early morning light falling / on your lovely someone’s / lovable bare feet as he walks across the wood floor to sit by the window”

“Let’s put our briefcases on our heads, in the sudden rain, // & continue meeting as if we’ve just been given our names.”

9. Serendipitously, I read Rivka Galchen’s Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch just after reading Maria Popova’s marvelous storytelling about Johannes Kepler’s defense of his mother’s witch trial in Figuring. It’s a fascinating story in that Kepler felt responsible for fueling the accusations against her due to an allegorical sci-fi story he wrote about moon people holding onto outdated beliefs despite evidence otherwise, and—small detail—the narrator got to the moon thanks to his magical mother. Kepler eventually cleared his mother’s name of charges and spent years annotating his own manuscript so that no one could misunderstand his intentions again.

Rivka’s book is a fictional telling more focused on the accused, Katherine Kepler, and reminded me of the narrative style of Miriam Toews' Woman Talking with a literate third party roped in to make a record and with the reader being told about the events conversationally vs. reading them. Around the same time, I watched the movie The Wonder (which has some tough tw content but was excellently done) which also resonates in theme, about the stories we believe and shape our lives around, and how the efficacy of religion and science is all wrapped up in story.

This was an excellent story based on fascinating history, and Rivka’s writing is both dryly funny (“A hummingbird once rested near my shoulder. It was a very ill omen. For one who isn't a flower.”) and thoughtful (“I had to say what was in my heart, which is knowledge.”).

10. I really enjoyed This Party's Dead, in which British journalist Erica Buist, to cope with her grief at the loss of her father-in-law-to-be, travels to seven death festivals around the world to learn how people in other cultures grieve.

“Whenever anyone suggests the dead are in attendance, gifts and sugar always seems to follow.”

The journey's question broadens from "how do we grapple with the reality of mortality" to the more meaningful exploration of "in what ways do we continue to have a relationship with 'our dead'"? Because we do have one, even if our culture doesn't know what to do with that relationship or provide us with outlets for remembering in community. (There's a lovely line in which someone refers to their ancestors as "my" dead.)

Some of the festivals she visits involve meals in graveyards, others take place when it's time to bury a body--sometimes months or even years after a death, and others involve exhuming bodies so that living family members can rewrap them or visit quite literally with their bones before reburying. As part of a western tradition that sees very little of and so fears dead bodies, Erica asks celebrants how they feel about the corpse of their loved one. She often assumes incorrectly a reason why something is done (perfume over the body not to hide the smell of decay for us but to show the loved one they are still cared for) and observes: “Time and again, I see fear [as a cause for a ritual] where there is only love.”

It's a moving book, written with humor and openness, and I'm very drawn to the rituals of communally remembering our dead. I wish we had something like this beyond a funeral to help us transition from having a living loved one to a dead loved one: a reason to come together often with food and sharing and to invite our dead back home, even if for a little while.

As one festival celebrant tells her, “We think about dead people all the time. We pray for all the ancestors, even the ones we don’t remember; we have a huge celebration for them every six months. They’re not lost.”

(Book buddies: Mexico's beaches and Scotland's train views.)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Favorite Reads of 2022

With how many books I loved this year (lots of poetry, speculative fiction, and writers reading other writers!), it’s interesting to see what really lingers with me. Some books, like Rebecca Lindenburg‘s are quiet but I always think of her list-poem of clouds when I look up at the sky. Fathoms wasn’t exactly a page turner and the long passages of statistics in Invisible Women made my eyes glaze over at times, yet I go on thinking about and sharing what I’ve learned from them. Olivia Cronk and m. forajter are friends and encountering their voices again on the page was the most special kind of reading experience. The first six books on this list were particularly unexpected and inventive in how they played with form. Here’s a little more of why I loved each of them:

1. I simply adored Dear Sal, a poem/play/poem/epistolary by Jeremy Radin (published by Not a Cult) about love, longing, and home. With its backdrop of war and the Jewish diaspora, theatrical feel, and love story, plus a fabulist cast of characters, Dear Sal reminds me of Ilya Kaminsky’s Deaf Republic in all the best ways. Abacus, “the letter-composing klutz,” writes to Sal, “the stubborn beloved,” a year after their brief affair, and the others chime in—in sympathy, distraction, or encouragement that he once again find “stars and the beginning of your darlingsong” (my favorite line, right up there with “the animal of my solitude.”) The letters to Sal are my favorite parts but also delightful are the distinct voices of each of the personae poems, as in this one from his pants:

“But o you bleary

and bumbling thing!

O you brimming

and bumbling marvel!

What is all this [he indicates my bumbling]

but proof

that all this [he indicates the mysteries]

is working?”

2. In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado is a tough and exquisitely told story. A memoir of a psychologically and emotionally abusive queer relationship, told at a slant, through the tropes and genres of other stories—spy thrillers, creature features, stories of wrong lessons, omens, natural disasters, and deja vu. Through her story, she also explores the general disbelief of abuse in queer relationships, the desire to “put our best foot forward” in the community, and the subsequent need for marginalized communities to be accepted in all their humanity—acknowledging the good and the bad. Again, it’s a tough read, but also incredibly moving and I loved the path she found to write about the unspeakable.

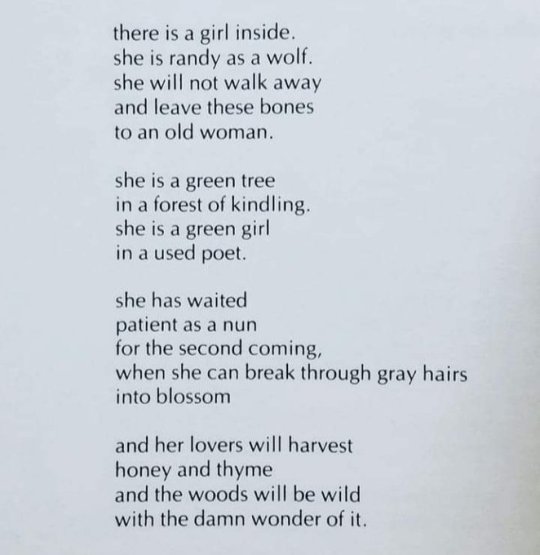

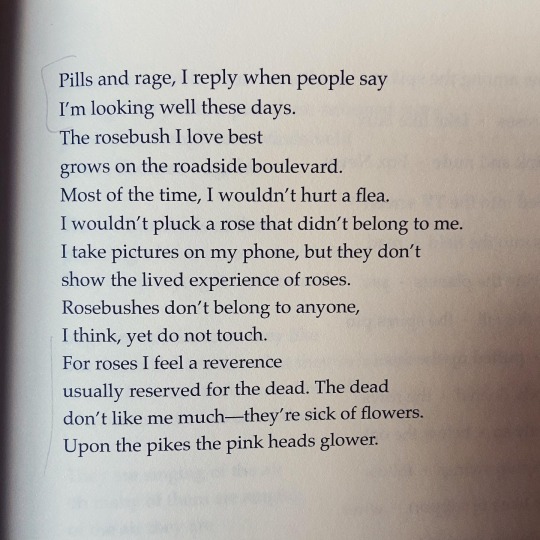

3. Interrogating the Eye by m. forajter (Schism Press) is a journey in understanding what images represent—a witness, an annunciation, a leakage, a thinking of the future, the self (“boring!”). Under the influence of Kurt Cobain, roses gifted by Bhanu Kapil, and medieval art, forajter writes with and on depression in a world that is polluted, sick, and full of passion. How do you return to making art when your relationship to yourself has changed, and where is “a steady hand … to no longer think in pieces”? Forajter looks and looks, and her looking grows into a kind of ownership and replenishing desire. It’s a heartfelt and exciting read.

“tuned towards the void/tuned towards myself // and yet, the sneakiness of vision. the sun that touches. the multiplicity of light. this is a vision made velvet.”

4. Where the Wild Ladies Are by Aoko Matsuda, translated by Polly Barton is a special kind of ghost story collection. Inspired by Japanese folktales, Matsuda’s stories feature a woman’s lover who, fished out of a river, appears every night in need of a bath; a son grieves his mother too much and to her annoyance; two saleswomen are eerily successful in getting people to buy their lanterns; and a ghost who died counting plates counts them again in her new form. These stories feature clever and thoughtful women with expanding ambitions and selves, exercising their very special talents alongside the living. This was so unexpected in style and voice and utterly delightful!

5. In two long poems, Olivia Cronk takes us into a wild, performative space in Womonster (Tarpaulin Sky). Scenes are blocked for the stage, our characters lounge on beds paging through magazines, and the narrative is frequently interrupted by a interrogator asking the speaker if they know what they’re doing. Through a deep attention to childhood and adult desires, fashion (“I understand the game is played in costume”), and the emotions we “parade in language,” she examines the many selves we carry from one era of our lives to another and one space to another:

“everything leaks / from home / and like it’s coming right into my purse like I packed it in the morning with my lunch”

The theater of home life is re-created on the page as both a control space to practice living in the speaker’s preferred conditions (“I cannot bear / domestic re-order”) and a purely play space rejecting convention and seeing everything anew (“the impossibility of the stairs meeting us is like a play”). It’s a thrilling, soap opera of a read, one to keep you on your toes and full of possibilities that only Olivia can create.

6. In The Trees Witness Everything, Victoria Chang (Copper Canyon Press) herself two very interesting constraints: a response to a poem title by W.S. Merwin and the form of a Japanese syllabic poem. The short poems (on memory and time, how we move through the day, how we look up and the birds we see when we do, and sadness, meditations which always seem to move together) are simple and powerful, giving so much space to sit with in the hard moments and delight in the small moments. I like that Chang writes mostly from a realist perspective, slipping occasionally into the surreal. And among the moon. Poets and their moons and the birds—I’ll never tire.

“There is a bird and a stone

in your body.

Your job is not

to kill the bird with the stone.”

7. The Undocumented Americans by Karla Cornejo Villavicencio is a moving picture of both the large and everyday challenges that undocumented people face. Through interviews and her personal experience, Karla raises the issues of what being undocumented means for access to health care—the networks of healers and solutions that spring up in its absence and the challenge in caring for aging parents, which particularly struck home. She writes how because of the need for work, undocumented people are often the first responders in crises and natural disasters, as in the case of 9/11 clean up efforts, but do so with a high risk of exploitation (to their health and to getting paid) and few means of advocacy. And she shares stories of people living in sanctuary, its indefinite state and challenges and its affects on families. In her introduction, she writes that she approached the interviews not with a journalistic focus but in the spirit of translation, particularly of poetry, to convey her subjects with the warmth, humor, wit, weirdness, and annoying traits they had, to make them more than workers or legal terms, to make them human. A necessary read and so much to think about what and how we can change our systems. One heartbreaking passage that has stuck with me is of the long-term effects of generations of kids being separated from their families:

“Researchers have shown that the flooding of stress hormones resulting from a traumatic separation from your parents at a young age kills off many dendrites and neurons in the brain that results in permanent psychological and physical changes. One psychiatrist I went to told me my brain looked like a tree without branches. So I just think about all of the children who have been separated from their parents, and there’s a lot of us, past and present, and some under more traumatic circumstances than others—like those who are in internment camps right now—and I just imagine us as an army of mutants. We’ve all been touched by this monster, and our brains are forever changed, and we all have trees without branches in there, and what will happen to us? Who will we become? Who will take care of us?”

8. Invisible Bias: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men is a book that is somehow both obvious and illuminating and also vindicating and incredibly frustrating for women to read. Caroline Criado Perez explores the places where we lack gender-specific data for everything from the unexpected planning of snow plow routes to creating clean-energy stoves to filing joint taxes. Some of this women just know intuitively: office spaces are too cold, seat belts are uncomfortable, iPhones rarely fit in pockets or hands, and gosh we do lots of unpaid labor. But it’s fascinating and affirming to see how these standards come about and how they might easily change once we gather the appropriate data and include people in the communities that a product/medicine/service serves to be part of the planning and feedback processes.

9. This year I read two collections by Rebecca Lindenburg, whose work is quiet and yet has loomed large in my mind. The Logan Notebooks (Center for Literary Publishing) in particular is a listy kind of book, in the spirit of Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book, a consideration of what makes a poetic subject. Lindenberg’s poems are gatherings on the topics of trees, mountains, insects, winds. On things that matter and things that have lost their power. Set in many kinds of wests, but mostly Utah, Lindenberg chronicles dailyness, the beautiful and impossible things that happen and also the things that are simply there. It’s an easy, meditative book to fall into, and one that grows in loveliness the longer you sit with it.

10. And finally, Rebecca Giggs' Fathoms: The World in a Whale was a dense and slow read and at times a little boring and yet these reasons are part of why it’s stuck with me for so long. The book focuses broadly on humans’ history with and impact on whales, partly in how our trash affects them (one whale was found with a whole greenhouse in its stomach), but also our noise, our tourism, our exploration and excavation of the world, our attitudes toward experiencing nature. She writes that because of her research, “my entire definition of pollution demanded revision." Griggs advocates for a philosophy of conservation that goes beyond "saving the whales" to retaining the "possible contexts in which they can continue their unique behaviors." She writes:"How to care for unmet things would seem to be a key question of this political moment."

My favorite fact: Cow farts release carbon dioxide, but whale poop helps absorb it. Because of ocean pressure, they rise to shallower levels to poop—and the current of their poop stirs up organic matter, bringing it closer to the surface so that it photosynthesizes, accelerating plankton growth and absorbing CO 2. The last 200 years of whaling has significantly depleted whale populations, altering the air and earth's atmosphere. So restoring populations would mitigate climate change—as significantly as trees. (!!!)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite Reads of 2021

I read more books this year than I ever have since I started documenting my reading in 2009. The continued ups and downs of the pandemic made books a grateful escape, but having read so much—and a lot of it “reading lite”—there’s much that blurs together and fades quickly. However, I was excited to come across Katherine Addison and Nghi Vo, whose stories thrilled me to my toes. I read Ken Liu’s The Paper Menagerie in January and his images have haunted me throughout the year. I read very few poetry books in 2021, and yet they’re the words that most take up residence in my mind and heart. And The Hidden Life of Trees kept me company on my frequent walks among the trees of my neighborhood. Here are a few more books that clung to my restless mind this year:

1. The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben portrays trees so personably, talking in terms of how they parent and educate, passing on knowledge or learning from a summer of drought. How beeches are somewhat the bullies of the forest as they grow around and through the crowns of other trees. How trees that are sleep deprived—either nightly or seasonally—don't live long. How the roots of a particular old quaking aspen have sprouted thousands of offshoots in its time. How trees are social, communicating threats to each other via scents and taking care of their wounded by sharing nutrients via their roots. How walking under some stands of trees can lower your blood pressure and increase lung capacity. How tree species migrated south and then back north after the Ice Age. How trees with year round red leaves are rather inefficient and would have died out had humans not thought them so pretty and continued cultivating them. How the whole life cycle of a tree's life is important to a forest, which we often don't allow for, and other fascinating facts that makes this book such a pleasure to spend time with.

2. Hotel Almighty is such an exquisite book that immediately upon finishing I went and ordered three more copies to gift to friends! Sarah J. Sloat erasures and adds collage to pages from Stephen King's Misery. Each page is rendered so differently. I gasped aloud several times. There are surprising and beautiful lines such as “lay back in the urgency of work” and "burning seemed the proper thing, like research for a great drama." This book is a pleasure.

3. In Nghi Vo’s novella When the Tiger Came Down the Mountain, a story collector is trapped by three tiger sisters and must wait through the night for help to come, so the story collector tells the sisters a folk story of a tiger and scholar. However, the tigers have the same tale in their folklore, and frequently interrupt to tell it from their perspective. It's a beautiful questioning of who gets to tell a story and how the story is shaped by who’s telling it. Doesn’t hurt that that the folktale also centers a poem, which I will always cheer on.

4. A lot of poetry books are quiet with a kind of quiet that works its way in, slows you, attunes you, shifts you, and I like that kind of poetry, I do. But then there's Homie by Danez Smith, which is loud and spilling off the page and calling to you from across the street and even while there are a lot of heavy topics that they address—of losing a friend to suicide, of not being able to come out fully to their family, of trying to survive and thrive in a white supremacist and straight world—at its core, it is a book of joy that revels in and reveres friendship, and god, I love friendship and I love people writing about their friends and I love when love feels loose and uncontainable and the largest part of the sky and I think this book might bring you joy, too.

"a thousand years of daughters, then me.

what else could I have learned to be?"

5. I was surprised at how compelling I found Katherine Addison’s The Goblin Emperor, which has a premise I glossed over and not much plot to speak of. But I couldn’t put it down! A forgotten half goblin/half elf in the middle of nowhere suddenly finds himself in line for the throne and moves to the elven court to begin his rule. It’s not as high fantasy as it sounds as it’s more about the intricacies and politics of being at a royal court than in a fantastical land. And it’s not even as Games of Thrones-ish as it sounds because the new king, Maia, whose journey we follow, is so earnest in his desire to rule kindly and give respect to those who serve him—to the continued astonishment of those around him. He’s good, but with all the relatable insecurities about managing others while being true to oneself. There are several attempts to dethrone Maia, yet there isn’t a strong plot driving the book. It’s mostly about Maia learning the ropes in an oppressive/traditional society while trying to change it and tenuously building friendships even though he’s repeatedly told that kings can’t be friends with those below him—meaning anyone. Ugh. You just want him to find a friend!

6. Meghan Privitello’s Notes on the End of the World doesn't look like any specific apocalypse. At the end of the world time crumbles, carnivals never leave town, earthquakes hit, animals are where they don't belong, and "every barn has become a church / to worship storms in." But each day's note captures some moment of bravery or loneliness, regret or determination or sanity that speaks to even small world-falling-apart experiences. Privitello asks: "with minutes until disaster / what do you gather? How do you / navigate your own useless fear?” And later: “Somehow we’ve all been given the same fate, / which means our lives are ordinary.”

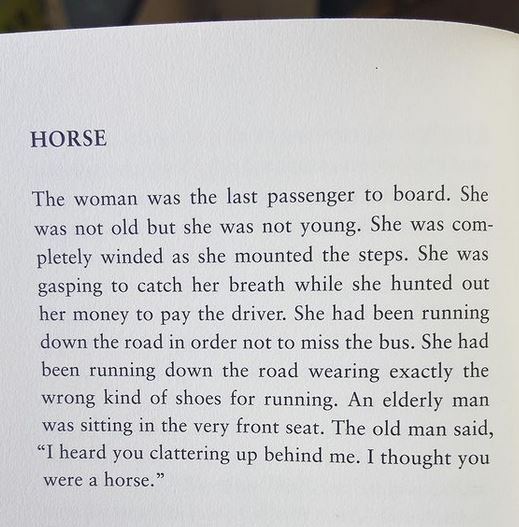

7. By Bus by Erica Van Horn is a little travelogue documenting the conversations you don't want to hear as the author commutes by bus through the small towns of Ireland. So much happens on a bus: shoes are polished and a woman looks for a husband and a mother is forgotten in the last town. A near disaster with a red Ford Fiesta creates an unexpected kinship among the passengers, and tourists on one side of the bus take pictures of sheep while the other side focuses on a castle. There are lots of missed connections and lateness (never earliness) and scathing criticism for passengers who don't say thank you when they leave. It's a very charming book about people being people that almost (almost!) has me thinking fondly of my daily train commute before the pandemic.

8. Witch Wife by Kiki Petrosino is so playful and witchy! I feel in awe of the energy in Kiki’s poems, her unapologetic way of writing and being herself, the human mix of everything good, messy, and hard. And it’s clear that she takes pleasure in words—through her forms such as sestinas and villanelles as well her prose and other pieces—a pleasure so swiftly passed on to the reader.

9. Night Talks by Elisabeth Rynell, translated from Swedish by Rika Lesser, is a raw expression of grief / a long poem and lament written upon the sudden death of Rynell’s husband. It’s beautiful and hard. Most of it is poetry, but she bookends it with a moving interview with her sleepless self at night and with stills of memories. // I began reading poetry when in need of words I couldn’t find myself, and I am always grateful for those who commit to paper their thoughts in the midst of pain. It makes some books strange to recommend, but they are there for when you need them.

10. The Paper Menagerie by Ken Liu is a beautiful collection of short stories that take place in China, Japan, the US, beneath the Atlantic Ocean, outer space, the past, and the future. My favorite story is one in which people's souls are born with them as objects—a salt shaker, ice cube, pack of cigarettes—and they must learn to live without using them up. Another story imagines the ways different alien species make "books"—some record of thoughts that can be passed to the next generation. In another story, a woman survives by accepting change again and again until ultimately she is transformed into light. There are heavy-sad moments as well as sweet-sad, and often a theme of something to be sacrificed. Ken Liu's premises are smart and inventive, and like any good sci-fi, tell us a tale of our humanity.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite Reads of 2020

In this year of slowness, thank god for books to make the world a little larger again. I read several classics for the first time—Shelley’s Frankenstein and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day—all of which felt important to return to the source material, to see how these books shaped those that came after them. And I delved into new books from favorite authors whose words I will always seek out—like Kelly Schirmann’s The New World and Heather Christle’s The Crying Book—and I branched out into mystery and romance books because they kept pages turning and tidied everything up so neatly at the end, which if not my usual fare, was sorely needed in this strange year. But since I do love a list, here are the books that sung to me / inspired me / shaped me:

1. Exquisitely told and inventive in form, Women Talking by Miriam Toews centers on a group of Mennonite women in South America who discover they're being drugged and raped during the night by the men in their community. While the men are away, the women meet to decide whether they will stay and forgive their attackers, as their community’s religious leaders ask them to, or leave the colony and start anew. Their conversation over the course of two days questions the role of women, what freedom and forgiveness really mean, how to fulfill one’s calling as a woman, mother, and believer, whether one must choose one thing over another, and whether staying or leaving carries the greater risk. It’s a thoughtful and creative approach to hard questions and the complicated reasons why there’s never a right answer.

2. Ilya Kaminsky's collection, Dancing in Odessa, was one of the first books of contemporary poetry I ever read, lent to me by a friend in college, and I remember being stunned at what poetry could be and do. Deaf Republic stuns in the same way. The poems are incredibly cinematic, telling the story of an occupied town and its people and a couple who fall in love. When a young, deaf boy is shot by the soldiers, the entire town pretends deafness in rebellion, finding excuses to not understand the soldiers. They bear witness to the boy’s death and honor his life. Though a fictional town, the call to political action, to really see those who are being oppressed and stand for justice with them, is resonant for any time and place. Plus, Ilya writes the most beautiful love poems.

3. Another cinematically-inclined poetry book is GennaRose Nethercott’s The Lumberjack’s Dove. In this long poem/myth/fable, a lumberjack accidentally cuts off his hand, which turns into a dove, and then a story parts ways. The lumberjack is not just a lumberjack and the hand-turned-dove is not just a hand-turned-dove, and the story visits both an operating room and a witch, and the story, of course, is one you've heard before and one that brings surprise and wonder to the telling. I simply adored it.

"Living creatures believe they own something as soon as they love it. They refuse to believe otherwise, no matter how many times a beloved vanishes."

4. I fell in love—hard—with The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller and her exquisite, queer love story between Achilles and Patroclus. Miller’s writing is wonderful and after reading her novel Circe as well—another fantastic retelling of Greek myths—I spent the remainder of the year searching for a novel that compared.

5. Some books meet you in the right moment. The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey is a slow and attentive book on small things, which in 2020’s period of waiting and uprootedness was a gift. Due to chronic illness, Bailey finds herself confined to a bed with little to do. Her friend brings her a potted plant and a snail whose pace of life, matching her own, becomes a comfort and lessons her loneliness. As she watches, she learns intimately the snail's eating and sleeping habits, its daily adventures, and the conditions it best thrives in. Later she delves into the literature and science of gastropods and weaves her notes in with her own observations and stories of the snail. Her writing is light and funny and holds such tenderness for this very small creature.

"In the History of Animals, Aristotle noted that snail teeth are 'sharp, and small, and delicate.' My snail possessed around 2,640 teeth, so I'd add the word plentiful to Aristotle's description....With only thirty-two adult teeth, which had to last the rest of my life, I found myself experiencing tooth envy toward my gastropod companion. It seemed far more sensible to belong to a species that had evolved natural tooth replacement than to belong to one that had developed the dental profession. Nonetheless, dental appointments were one of my favorite adventures, as I could count on being recumbent. I could see myself settling into the dental chair, opening my mouth for my dentist, and surprising him with a human-sized radula."

6. Insecurity System by Sara Wainscott was one of my favorite books published in 2020. The poems in it make up four crowns—a series of sonnets in which the last line of each poem becomes the first line (or an echo of it) of the next. The playfulness of the form as well as the topics give the book an energy: Sara muses on time travel, levitation, memory, flowers ("people who read poems know a rose / is how the poet drags in genitalia"), motherhood, Mars, and mythical transformations (children tell their mothers they have turned to seals “and it is true”). Sara is funny and wry, and yet she also captures some difficult emotions of grief and depression, a struggle with complacency amid daily obligations “Sentences become drawn out affairs / but I am doing what I can / to answer one word each day.” The poems move from the mundane to a hard feeling and then onward to wonder and a bit of the fantastical, which I guess is just how life goes—I love how these emotions are all rolled together and always shifting.

7. Asiya Wadud’s powerful long poem Syncope is one I’ve returned to often throughout the year. She tells the story of 72 refugees who fled Tripoli in an inflatable boat in 2011 and were stranded for 14 days, despite the presence of 38 maritime vessels who could have rescued them, but didn’t. Instead, only 11 passengers survived. Syncope is both an indictment against those who did not act and a eulogy for the dead, returning humanity to people who were deemed not worth saving but who were “luminous in that / we were each born under the / fabled light of some star.”

“We began as 72 ascendants

by that I mean we were a collective many

each bound for greatness merely

in the fact that we were each still living”

8. Eula Biss’s Having and Being Had is a thoughtful and exploratory conversation about capitalism and its effects on what we do and how we think. In a series of short vignettes, Eula picks apart what consumption, work, accounting, and investment mean on a personal and everyday level (albeit a white, middle class level). Who defines value among boys trading Pokemon cards and how did Monopoly's origins in economic injustice shift to pride in bankrupting players and if one of Eula's favorite things about being a new house owner is easy access to a laundry machine, is her house merely a $400,000 container for one washer and dryer? Her essays bounce from work that is valued, unseen or shamed; the perceptions and realities of being poor or rich; our approach to gift-giving and art-making and pleasure—weaving together research, observations, and conversations with friends.

9. In Grief Sequence, poet Prageeta Sharma’s grieves the loss of her husband in a kind of journal, tracing the memories of his diagnosis, the hard and normal days, the days before diagnosis, and the days after he is gone during which she tries to make sense of her new reality: “How gauche it is to be in this body being unseen by you now,” she writes. “You are not you anymore and I am trying to understand how a human with feelings has disappeared.” Her writing is excellent but it is hard to sit with and next to her pain, and it makes me wonder: when does one read such a book? When you’ve also lost a beloved to cancer? To be in conversation with someone who has, with Prageeta? Do you read for the sake of the living or to honor a body who was once here? Prageeta writes, “Poetry and grief are the same: you are taught to care about it when it happens to you.” I don’t know who to recommend this book to, but it spoke to me, and I’m glad she wrote it, as a monument, of sorts, to a specific togetherness and to a person.

10. The Lives of the Monster Dogs by Kirsten Bakis is a strange and sweet book about a race of genetically-engineered dogs, created initially to be soldiers, who move to New York in the ‘90s while still holding onto the customs and dress of nineteenth-century Prussia, which is to say: I don't know if I ever would have picked this book up had a friend not recommended it. Told through news clippings, letters, journal entries, an opera(!), and the first-person account of a human who befriends them, their story has echoes of Frankenstein as the monster dogs reflect on their creator and what it is to be human, to have purpose and hope, to wrestle with a clouded past and an uncertain future. "It's a terrible thing to be a dog and know it," writes one monster dog scholar after some of the dogs begin to revert back to their primal state. I loved the varied forms, the piecing together of the dog’s history, and the surreal mark they left in the book’s world and my world.

For more books throughout the year, follow along on Instagram at book.wreck.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

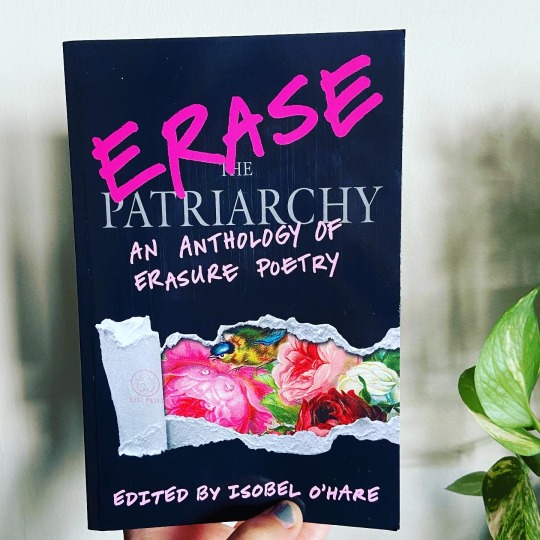

I’m thrilled to have a few poems included in Erase the Patriarchy! The anthology of erasures, which came out from University of Hell Press in September, is a beautiful mix of creativity, snark, wit, anger, and humor. These poems root out the selfishness and misogyny found in men's sexual harassment apology statements, song lyrics, and poems; in court cases and political speeches; and from leaders within sports, religion, and education. In their introduction, Editor Isobel O’Hare writes of the pandemic and the 2020 US election (between two men who have both been accused of sexual assault) what is true of any movement for justice: "There is always some catastrophic occurrence, some crisis ever more urgent that beckons our attention away from those crying out." Which is to say that this book arrives in the midst of many other urgent concerns and daily coping as a playful reminder that the work is ongoing.

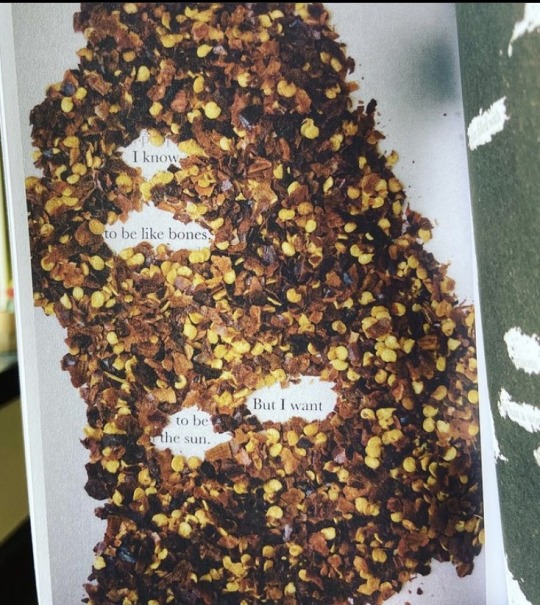

I contributed a series of erasures of Norman Mailer’s poems, using spices like red chili pepper below.

It's been a delight to contribute—and super exciting to read an array of voices who have gone in all directions for this prompt. I really, really hope that readers feel inspired to continue this project in their own unique ways. Below is a photo of several contributors at the virtual launch party earlier this year.

You can buy copies of Erase the Patriarchy here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

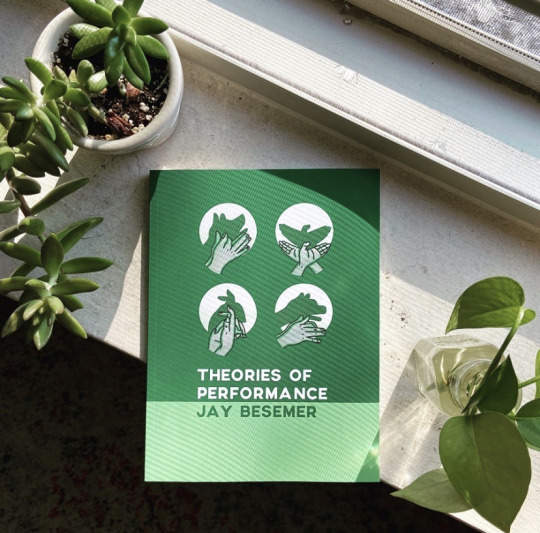

While this year has been one of slowness in many ways, it was also the year we released one of my favorite books to have published: Theories of Performance by Jay Besemer! Jay's poetry collection engages with issues of living in and through a queer, trans, sick/Disabled man’s body and examines the many ways we perform—a gender, out of expectation, in art. I find Jay's work so thrilling—these poems know themselves, confident even as they share what is vulnerable, what is close to the heart and skin. They recognize the limitations of a body while creating its many possibilities: "I'm not broken down / into something with / or without parts,” he writes. “The / grammar here is a / unique body."

Also, did I mention the animals? There are bear hearts and slick fish, huddled pigeons and mice, owls and badgers and hawks, the priest of hummingbirds and a green-shelled mussel and us, our very animal selves.

Get your copy via Lettered Streets or Small Press Distribution.

And check out the concept maps Jay created while drafting and shaping the book. The maps, helped him to draw connections and note themes throughout the process. Take a peek behind the scenes to see what the process was like and how the book evolved. He shares a bit more about the process of creating the book on The Kenyon Review.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I shared about a few lovely / hard / needed books for Tarpaulin Sky Magazine’s "What I'm Reading" series.

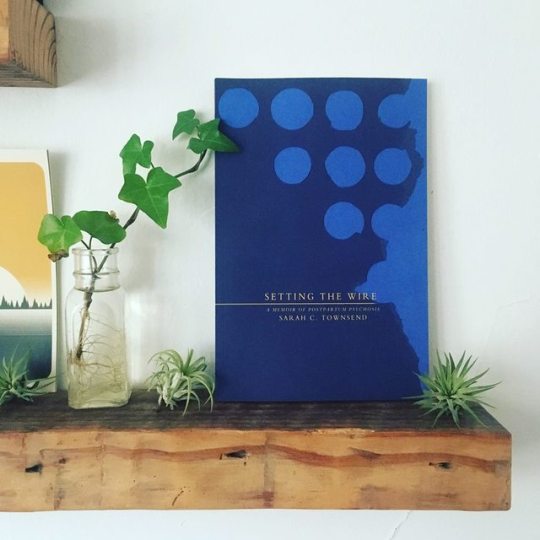

Mini reviews of Syncope by Asiya Wadud (@uglyducklingpresse), Grief Sequences by Prageeta Sharma (Wave Books), 1919 by Eve Ewing (@haymarketbooks), Litany for the Long Moment by Mary-Kim Arnold (Essay Press), and Setting the Wire by Sarah Townsend (@letteredstreetspress).

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

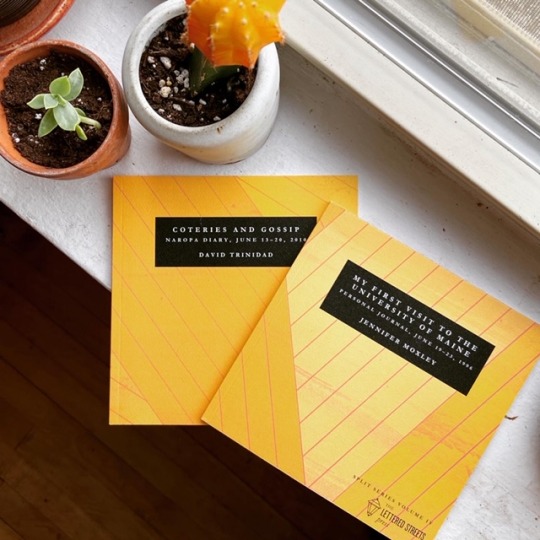

This book came about over tea on a sunny afternoon (perhaps all good books start so?) when I told David Trinidad how much I liked his previous book, Notes on a Past Life, and his vivid accounts of poets and writers in the 1980s and 90s of New York, a book made possible by David's habit of keeping a journal. He thought he might have other entries about poets worth sharing, and then he thought of Jennifer Moxley, another frequent diary keeper, and so in this 2 chapbooks-in-1 volume, they each share entries from their times at writing conferences and programs in 1996 and 2010. In them, they run into old friends and meet new people, take notes on writing advice, and go for moonlit drives (these are poets, after all; the moon is observed ☺️)

Diaries have an irresistible draw—so honest and detailed, curious in the mundane and often insightful. They give a peek into who people really are, hook us with their familiarity. “Before we are the poets we are meant to become, literary friendships prop us up and give shape to our ambitions,” writes Jennifer Moxley in her introduction to David’s side of the book, and this is why I've loved helping to make this a book: these entries invite me into a writing community when I don't always feel part of a community (hello #quarantinelife), remind me of how writing includes times of not writing / of just being, and show how what we do and achieve is always interconnected—a line is inspired by someone else's comments, a reading leads to an invitation, etc. And also, I'm so thankful that such interesting thinkers as Jennifer and David give us a peek into their lives.

Intrigued? Read more / order.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

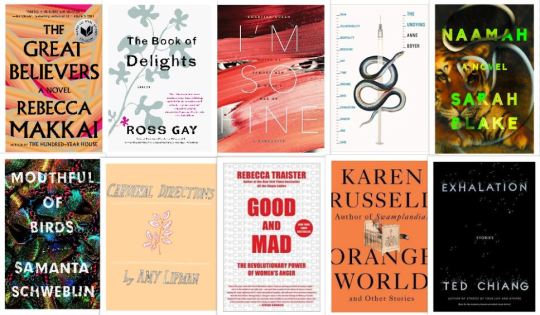

Top 2019 Reads

1. The Book of Delights by Ross Gay is written (and cannot help to be read) in a spirit of pure joy. Each entry is a few paragraphs on something he delighted in for the day—from a hyphen ("the handshake of the punctuation world") to the concept of do-overs in games ("it delighted me in part because among the sorrows of adulthood, this action can feel more fantasy than possibility"). Watching someone look at the world in wonder and in gratitude changes you, softens you.

2. Naamah by Sarah Blake is a strange and gorgeous book I can't stop thinking about! Sarah retells the story of Noah's flood in an exciting and inventive way (an impressive feat if you're someone who's heard the biblical story countless times) that includes lots of dreams, a cockatoo guide, a tiger who is seen and not seen, and desire in many forms. It is surreal and real and poetry. It's that kind of story that I wish I had the chops to write, but since that would take me years, I'm so glad Sarah wrote it and that it's here now in this very present moment to read.

(And bonus! Reading this book made me return to her earlier collections of poetry: Mr. West, which follows Kanye West and his work, and Let's Not Live on Earth, which includes a beautiful series of monster poems. 2019 was the year I became a huge fan of Sarah’s work.)

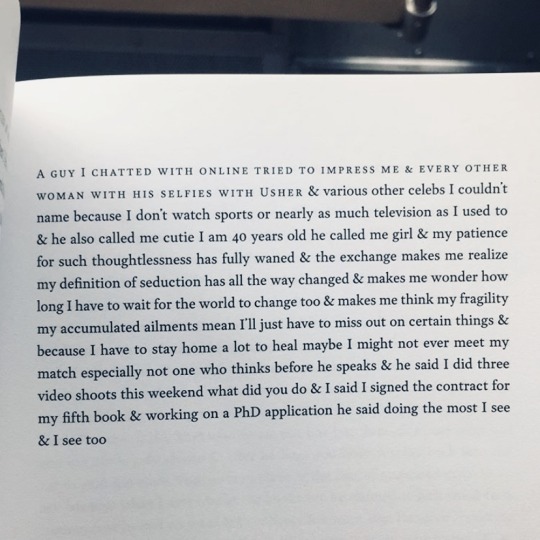

3. I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On by Khadijah Queen, which came out a few years ago from YesYes Books, is an inventive, energy-giving collection of prose poems. Khadijah’s speaker runs into Prince, Nelson Mandela, Elton John, The Rock, and others in both mundane and strange circumstances—on a video shoot or at the mall or at a bus stop or on MySpace. Some encounters are simply documented, others show the subtle or overt microaggressions women, and particularly Black women, face, and others revel in the joy of being, of talking back or just talking.

4. Much has been written about Rebecca Makkai’s The Great Believers, and all the praise is true. Her story weaves together the AIDs epidemic in the Chicago gay community in the 1980s and the present-day story of a woman connecting with an enstranged daughter and dealing with her memories of those who passed away. It’s a time that I’ve heard so little about and Makkai recreates the confusion, fear, and anger that many people felt as well as creates vibrant and real characters whom you also grieve to lose.

5. Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger by Rebecca Traister made me angry in the best ways possible, but also gave me words for my anger (ah, yes! that’s what I've been sensing). She provides a solid background on the history of women's movements over the decades, in particular centering women of color's leadership in these movements. It's good to know where we came from!

“The task—especially for the newly awakened, the newly angry, especially for the white women, for whom incentives to renounce their rage will be highest in coming years—is to keep going, to not turn back, to not give in to the easier path, the one where we weren’t angry all the time, where we accepted the comforts of racial and economic advantages that will always be on offer to those who don’t challenge power. Our job is to stay angry . . . perhaps for a very long time.”

6. I picked up Exhalation, Ted Chiang’s latest short story collection, because I loved the 2016 movie Arrival, based on one of his stories. Exhalation surprised me—it was so different from what I usually read. Chiang’s work is very heady, his stories concept-based rather than plot or character based, and often focus around a scientific or mathematical fact. Though I didn’t connect with every story, his writing expanded my thinking, made me pay attention to the logic within the world—and I loved that he included notes at the end of of each story about his inspiration, which made me appreciate each one.

7-8. Orange World by Karen Russell and Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin are two very strange and delightful short story collections that remind me why I love this genre and how far writers can take us into the surreal and parrallel-to-the-real and still have us follow them. After being somewhat disappointed with Karen’s first novel, I was eager to read her return to the short story world. Months later I still carry around with me the eerily calm rowing of the “The Gondoliers,” a story about sisters who have developed echolocation to guide tourists through a post-apocalyptic polluted and flooded Florida. Mouthful of Birds by the Spanish writer Samanta Schweblin had a similar tone to Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado. I loved it from the first story “Headlights,” in which a growing collection of women left at a gas station by their new husbands together take back the wheel of a car and leave. These stories haunt and surprise and tingle your spine.

9. I read very few poetry collections this year (and I miss it…), but one I did read was Amy Lipman’s chapbook collection, Cardinal Directions, published by Ghost Proposal last spring. Amy’s voice is like chamomile tea, immediately calming and guiding my attention to the smallest details of home and solitude and what it is to be. Always with a note of humor (”I remember you like a pet”), Amy’s self-interrogation is honest and unexpected, her form direct and playful. This book calls me to myself.

grass adjusting itself after someone’s total weight or just one step

trying more throughout the day only to listen

I make arrangements to understand one part of the task before getting to the next spreading oil in the pan and witnessing it warm, asking myself

to stop

making

language

10. How do you recommend a difficult and heartbreaking book? The Undying is not for the well or intact but, as Anne Boyer writes, for those who once were sick or will be sick. Her book explores her journey through breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, through disability and exhaustion, through capitalistic-oriented healthcare, through the difficulties of living without state-recognized families, through the pain and body as history. Boyer weaves in and out of story, the (lack of) literature of illness, and the ways in which capitalism is tied up with acts of care. As someone who’s lost a loved one to cancer, it’s difficult to read, but necessary, too, to have stories of not alone-ness and stories that could beget change. Boyer has so many insights into how we respond to and are failed by healthcare and our culture’s attitude toward the sick, our often blind belief in surgeons and medicine to save us, the myth that cancer is one identifiable disease and not a metaphor, and the inevitability that medicine becomes “the safest opportunity for profit.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Two Podcast Episodes to Add to Your Queue

On the Ezra Klein Show, N. K. Jemisin shares how she does world-building in her books by creating one with host Ezra Klein. In determining what the very practical physical elements of terrain, climate, geography, etc. are in this imagined world, she extrapolates what values, power dynamics, and cultural identities might form because of them. It's a fascinating behind-the-scenes look at how stories are crafted as well as making you think about what factors have shaped the dynamics of our own world.

On Being's interview with Rebecca Traister and Avi Klein! Traister talks about women's anger and their relationship to anger, especially around gendered inequality (she's great!). Avi Klein is counselor who has worked with many men grappling with the #MeToo movement and his insights in particular about shame, the lack of agency that some men feel, and people's resistance to taking in someone else's hurt is eye-opening. Everyone should listen to this, to hear the "other's" perspective and to question our own defenses and learn to listen well.

0 notes

Photo

I'm so excited to announce @letteredstreetspress‘s latest book, Setting the Wire: A Memoir of Postpartum Psychosis by Sarah C. Townsend! Her debut work is a fragmented lyric essay on motherhood, mental illness, and family ties: what we hold and what holds us together. It's been a delight to work with Sarah and her story is an important one, beautifully told, and now available!

Go check it / read it / gift it!

0 notes

Link

In which I review Lauren Haldeman's Instead of Dying, a book exploring grief and form, transformation and illumination, how poetry creates worlds we can bear to live in.

0 notes

Text

Top 2018 Reads

I am immensely grateful for writers this year and the weird and difficult and beautiful and eye-opening worlds they take us.

I was delighted with the elegance of Ada Limon’s poems in The Carrying; and Megan Stielstra’s humor and optimism about creativity, community, and Chicago in The Wrong Way to Save Your Life; and the utter joy of language and love and owning who you are exuded throughout Jordy Rosenberg’s Confessions of the Fox; and the imagination of Octavia Butler, whose work I finally read (consumed? there is no one else like her! The Parable of the Sower had me in her world for weeks); and that’s basically one list of favorite reads. Here’s another:

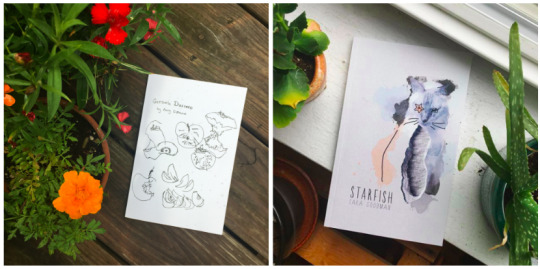

1-2. I wish that Getting Dressed by Amy Lipman and Starfish by Sara Goodman were on every top list of 2018! I am biased, I suppose, knowing them and being/writing in community with them, but I truly believe that if you are craving that feeling of being welcomed into intimate moments via reading, these are books that will gift you this. Sara’s book takes you on a walk as she wanders Chicago in the winter and thinks about climate change and stars and woolly mammoths and queer identity. Amy’s book invites you into her home as she examines the relationships between objects, people, her patterns of thinking, shifting your own awareness of self: “The senses aren’t reliable / they’re flat until / someone walks in.” Both writers bring a sense of amazement and curiosity about their world that makes you see your environment differently.

3. The best word to describe Wild Milk by Sabrina Orah Mark is delicious. I tried to savor this book story by story so it wasn’t read up too fast. There are particular writers whose voices feel like a blanket tucked tight around you or like stepping into your own skin or anything else that is warm and holding and feels like entering home, and Mark’s characters and whimsical dialogue and sentences that repeat over and over like they’re weaving a basket--another container to hold you--does that for me. I have too many metaphors going on. Here are Mark’s own sentences: “Mrs. Horowitz always refers to her husband as Mr. Horowitz should they ever one day become strangers to each other” and “‘Could Gloria come to you?’ ‘Her magnificence makes this impossible.’” If you like very short stories which slip into fabulism, humor, and poignancy without you fully understanding how you got anywhere, then you should read this book. And, lucky you who hasn’t read her first two collections, continue on to read her other work.

4. God Was Right by Diana Hamilton. I can’t remember in what journal I first came across a poem of Diana’s which led me to follow her on social media about the time she announced a forthcoming book of “arguments” from Ugly Duckling Presse which I immediately preordered (what a century we live in!). But thank goodness it happened, because these are delightful essays / poems / arguments about kissing and cats and being bi and teaching consent and reading books for the second time. She writes about the pleasure of the familiar and about freely contradicting herself (or rather evolving in thought) throughout the book, as poems allow us to do. So begins one argument:

It is stupid to imagine that cats, or really anything, are perfect.

Sure, you are, and I am especially, occasionally stupid,

and it is right to be this kind of stupid when a cat is standing on your shoulders.

But when given the opportunity to reflect more calmly, in the absence of cats, it should be clear that there are ways cats could improve.

5. In The Word Pretty, Elisa Gabbert reflects on all the things we think about as readers and (for some of us) as writers but don’t articulate, such as how we picture descriptions or the point of titling work and how we interact with the front matter of a book or the ways in which the meaning of pretty has changed. Her short and funny(!!) essays remind me of grad school—not the rigorous work of academia itself (which isn’t to say there isn’t rigor in these essays, just that it flows effortlessly) but the late night musings between friends on what their favorite books are doing and how they do it. In reading this one book, you are immersed in dozens.

6. An empty pet factory and moons orbiting dumplings in a restaurant and god inventing a more flexible forgiveness are just some of the worlds Matthea Harvey has created in Modern Life. She breaks up her playful prose poems like the one below with a running long poem, a kind of alliterative abecedarium, on love and war and healing that begs to be read aloud, read slowly.

7. Tell Me How It Ends by Valeria Luiselli is great reading and background on the journey and challenges migrant children face when seeking refuge from violence in their home countries, told by a translator/interpreter in the US immigration court who is familiar with our limited system in providing refuge. I can't talk it up enough! It's a good place to start if you're wondering how we got here and what we can do, because as Luiselli states, it is “not some distant problem in a foreign country, but in fact a transnational problem that includes the United States."

8. Carmen Maria Machado’s debut of short stories, Her Body and Other Parties, is everywhere and for good reason. Women are sewn up in clothes, a plague moves through the United States while a narrator reflects on her past sexual encounters, and, In my favorite story, Law & Order episodes are retold with a cast of otherwordly victims which makes you question how much women are valued in our world.

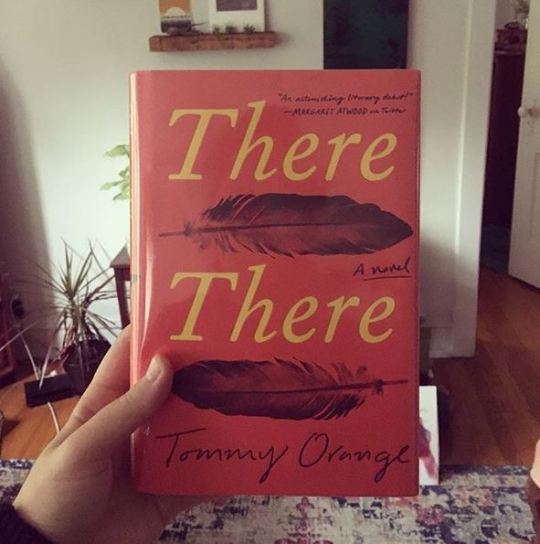

9. Tommy Orange’s debut novel, There, There, is a story of several Indigenous people whose lives eventually intersect at a pow-wow in San Francisco. Orange’s characters are so vivid, real with their struggles of pain and addiction, and his writing retells the story of generations from the side of the oppressed. “This was the sound of pain forgetting itself in song,” writes Orange. I couldn’t put it down and wandered aimlessly after I finished it, wishing I was back in this world.

10. I can’t recommend Rebecca Solnit’s work enough, and while she came out with a fantastic book this year on activism and recent political events, it was an older book, The Faraway Nearby, that I couldn’t stop thinking about. She writes about the stories we tell of ourselves and the legends that have shaped our communities, of caregiving and memory, the states of emergency and becoming. Her essays wander through ice and a mountain of apricots and the story of Frankenstein, somehow threaded together because "all stories are really just fragments of one story." If it had been my copy, there would have been underlined portions on every page. As it was the library's, I just wrote down passages such as this one:

"Listen: you are not yourself, you are crowds of others, you are as leaky a vessel as was ever made, you have spent vast amounts of your life as someone else, as people who died long ago, as people who never lived, as strangers you never met. The usual 'I' we are given has all the tidy containment of the kind of character the realist novel specializes in and none of the porousness of our every waking moment, the loose threads, the strange dreams, the forgettings and misrememberings, the portions of a life lived through others' stories, the incoherence and inconsistency, the pantheon of dei ex machina and the companionability of ghosts. There are other ways of telling."

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

You’ve heard of Frosty, the Grinch, Rudolph--now there’s Edward the Christmas Dragon! As co-creator Chris Woolsey shared: "A year ago I went to Zoo Lights in Chicago and noticed that among the usual candy canes, snowmen, and Santa Clauses there were also a couple of dragons dotted about the Lincoln Park Zoo. I must admit I’d never seen a Christmas Dragon before and found this to be a bit odd. As I was enjoying my mulled wine and thinking about these curious beasts, the character of Edward the Christmas Dragon was born. The next week Abigail Zimmer and I wrote a script on a car ride to South Bend and finally one year, one amazon order, and one extraordinarily chilly night of shooting later, Edward is here."

Shout out to the #LincolnParkZoolights for our set and to the lovely group of carolers we stumbled upon who humored us in singing along with Edward. We hope you enjoy!

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Good reads: Tommy Orange's debut novel, a story of several people whose lives intersect at a pow-wow in San Francisco. One of those books whose characters so drew me in, I didn't want the book to end, but it has and now what does one do? "This was the sound of pain forgetting itself in song," writes Orange.

2 notes

·

View notes