Text

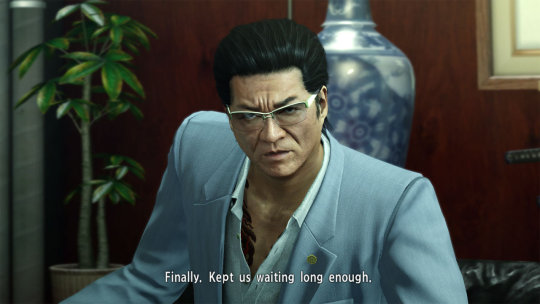

In Yakuza Kiwami, Kiryu’s Swagger Is Muted By The Times

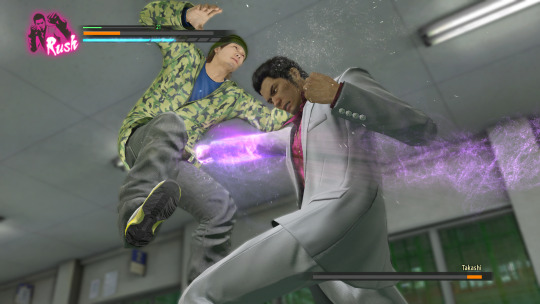

SEGA is no stranger to style. The veteran developer's back catalogue is full of riches if you like your games with a contemporary streak running through them. Their games have had bright red sports cars driving endlessly into blue blue skies, a too-fast-for-manners hedgehog scored by the King of Pop himself, and a rollerblading urban adventure bringing Tokyo J-rock/hip-hop fashion to players worldwide. With SEGA's long-running crime drama series Yakuza, however, things are different. Having proved they can make effortlessly cool games, the Yakuza series had higher ambitions – recreating a seedy slice of Tokyo's underground with brutal combat, high drama and a killer attention to detail. Style is not necessarily this series forte, featuring a photorealistic visual style and a penchant for high-quality cinematography over abstract “cool” design – instead, Yakuza packs a quality found in few other games, SEGA's or otherwise. Yakuza has swagger.

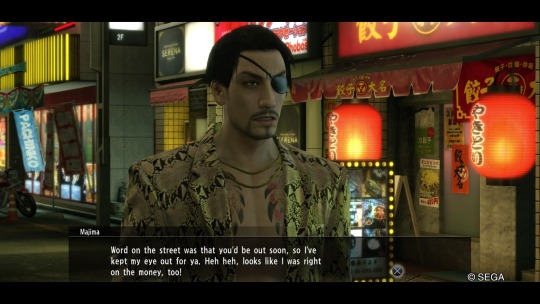

It's this swagger that made last year's Yakuza 0 stand so tall in a sea of instant classics. The 80s-set prequel takes the refinements of the series and kicks the 5-games-deep story to the curb, instead exploring the earliest years of series leads Kazuma Kiryu and Goro Majima. It was a much-needed starting point for newcomers to finally try out the series, but even amongst veterans the consensus seems clear: Yakuza 0 was very, VERY good. The whole game has a bravado, a specificity to its ambitions and its deliver that is so easy to love; it renders its setting in remarkable detail, getting down period details like pagers, disco, NES Dragon Quest fever and cabaret clubs, whilst never feeling too obvious. The music or dialogue doesn't let the setting pigeon-hole them, and when 0 does indulge in its 1988 backdrop, it's for the player's benefit, such as a ridiculous Michael Jackson encounter or a hilarious breakdancing fighting style for Majima. Beyond that, the cutscenes are impeccably shot, with the Japanese voice cast giving performances impressive even to my English ears, and the amount of side activities and their surprising depth and polish never stopped overwhelming and exciting me.

This wasn't the only Yakuza title released outside of Japan last year. Later in the year saw the arrival of Yakuza Kiwami, a PS4 remake of the original 2005 Yakuza for PS2. With 0 being my first dipping-of-the-toes into the series, Kiwami's existence (and localisation) was much appreciated, providing a necessary bridge from 0's isolated prequel tale to the wider Kazuma Kiryu saga. The game appears to heavily enhance the original game, bringing the fidelity up to par with 0 and adding a number of new activities and gameplay touches. Having recently wrapped up its story and most of the rest of the game, it's hard to shake off the feeling that what for some is a trip down memory lane, is for me an entirely different experience.

Yakuza Kiwami brings the story from 1988 briefly into 1995, before cutting to 10 years later to explore the state of the fractured Tojo Clan in 2005 Tokyo. Naturally, this reflects the year when the original Yakuza was released – back then, it was simply a contemporary crime tale, with what I presume to be no interest in being a barometer of the times. Indeed, Kiwami's plot follows Kiryu, his estranged brother-in-arms turned enemy Nishikiyama, their old friend/love interest Yumi, and Haruka, a 9 year old girl seeking out her mother. The events concern themselves primarily with the Tojo Clan's infighting, and how a recently incarcerated Kiryu can put an end to the bloodshed. Unlike 0, which frequently reflects on the prosperity enjoyed by late 80s Japan – its plot revolves around a plot of land, even – Kiwami feels more focused on purely defining Kiryu's convictions and strength.

Approaching Yakuza Kiwami as a newcomer lets this remake come into its own in several ways. Technically, Kiwami functions as a sequel to Yakuza 0, with many characters established in 0 returning in Kiwami, often in more prominent, important roles. Mechanically it is also identical to 0, recycling its combat system, many of its assets, and even a fair number of its minigames. Kiwami's additions to the original Yakuza game tend to be echoes of Yakuza 0 – a sidequest involving Scaletrix-type racing returns from 0, featuring a sequel sidequest with returning characters from 0; a women's wrestling league is repurposed as a ridiculous card-based arcade game; even the bowling, pool and darts minigames function identically. It feels more like an expansion pack at times than a fully-fledged original title, another hit of Kamurocho for those who didn't get enough from the 90 or so hours Yakuza 0 can easily provide. Even the city is ripped straight from 0 – though, granted, the district of Kamurocho is a common thread through the series.

Rather than a feeling of deja vu, this goes some way to developing Kiwami as a period piece of its own. It is easy to point to details like Kiryu's flip-phone, billboard screens and the fashion of the civilians to identify Kiwami as being set in '05, but those sorts of details are surface-level. My own memories of growing up in the 2000s weren't ones of cultural hegemony, unlike the 80s or even the 90s. The 2000s were the decade of political paranoia and technology's rapid growth leading to the defragmentation of “mainstream” - setting the stage for today, where for the most part, everyone goes their own way, and any instance of zeitgeist is baffling and without warning. Kiwami's Kamurocho has that feeling baked into it, especially coming off of Yakuza 0's more glitzy nightlife hub. The sidequests almost always involve cons or robbery, as multiple people goad Kiryu into a throwdown with a lazy scam attempt. The notion of honour even amongst thieves is shredded, as yakuza that would formerly hold knives behind their backs now openly tear each other's throats out. Even the major antagonist would rather see the young Haruka dead than let lie what risk she possesses to his ambitions. The world feels more jittery and paranoid than it did 17 years prior – and all the more dangerous for it.

The perspective of 2018 on Yakuza's 2005 roots make some contemporary inspirations more present, too. A big part of the story involves a surveillance network, initially set-up in response to terrorism fears, now operated by a former cop for his network of blackmailers. I definitely associate the 2000s with an up-tick in surveillance culture, despite living in the UK, so seeing this element present was a relatable surprise. The senseless spending of millennium culture features heavily too – a large landmark known as the Millennium Tower factors into the plot in a big way, an enormous skyscraper towering over Kamurocho. It appears almost entirely uninhabited, serving no function than being a shining monument to wasteful indulgence.

The result of Kamurocho's development since the 80s being so superficial and questionable is an almost wistful glance back towards the past. The aforementioned Pocket Circuit sidequest is a great example of this – a new addition for the remake, it sees Kiryu reunite with his 1988 racing mentory PC Fighter, as well as the now young professionals he formerly raced when they were children. It's a story with a lot of nostalgic reverence for Kiryu's past love of Pocket Circuit, and for anyone who played Yakuza 0 enough to really dig into this minigame, the reunions with the other racers are particularly touching moments. It appears the original Yakuza had nothing close to this quality of sidequest in it – whilst it’s clearly recycled content for convenience’s sake, it can’t help but suggest Kiryu has found few better distractions 17 years on.

The major new gameplay touch, the “Majima Everywhere” system, brings back the other playable character from Yakuza 0 as a recurring antagonist, accosting Kiryu in the street, the shops and even the batting range to try and bring out Kiryu's inner dragon once more. Majima was never a big part of the original Yakuza, and his heightened prominence in Kiwami feels like an acknowledgement that that was an error of sorts. Many of Majima's encounters reference his 80s escapades, such as his love of breakdancing or his former club owner occupation – it's another instance of the game looking back to the past for fun, interesting ideas. This is perfect from a 2000s set game – the decade where 80s music and fashion came back with a bang towards the end of it, and nostalgia began to be big business. Similarly, Kiwami spends a lot of time looking back on Yakuza 0, bringing back elements of that more popular original entry to flesh out systems and provide more activities.

Overall it impacts the classic Yakuza swagger, hard. Kiryu stills annihilates his opponents as he did in 0, but the game's backwards glance and knife-edge sense of urban danger make for a game with a very different vibe to its forebears. You can tell the series was still finding its feet here, but re-contextualised as both a remake, a sequel, and a period piece, Yakuza Kiwami finds its own bizarre identity in an almost self-loathing confidence. Happy to admit its era is a mess, and happy to mine another era for cheap pleasure, Kiwami is maybe the best representation of the 2000s in any game yet.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

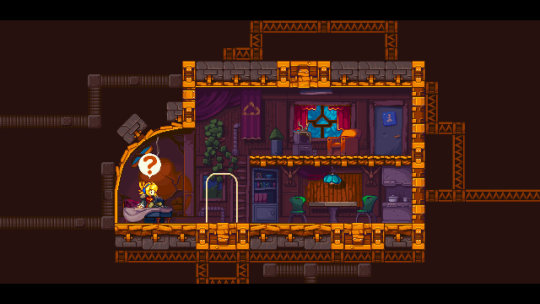

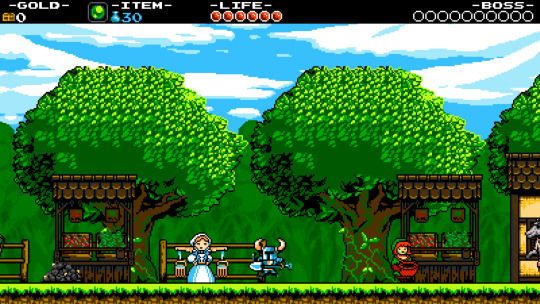

Review: Iconoclasts

Iconoclasts, like the subject of a Junji Ito-esque horror, feels like it was made for me, in especially devilish and unsettling ways. It combines a lot of the elements of the classics I adore into one big ambitious, clever, gorgeous mess of a game; the item-meets-environment puzzle-solving of The Legend of Zelda, the looping, layered level designs of Metroid, the smooth traversal you'd expect from games like Mega Man X. It's a game with its eyes to the giants of the action-platformer genre, most nakedly influenced by Metal Slug and Monster World IV, but the truth is I can see so much of a million other games I love in Iconoclasts, it's almost like developer Joakim “konjak” Sandberg has been peering inside my head for ideas of where to take the game next. But you needn't have me tell you that – on the surface, from its Metroid-esque map screen, the enormous SNK-style bullet sprays and the SEGA green hills and blue skies, Iconoclasts indeed looks like a pretender to the throne, another indie retro game tribute-cum-rehash to the heyday of This Sort Of Game. Fortunately, despite first impressions, Iconoclasts has its own tune to sing.

Breaking from tradition should be paramount for any game named after “iconoclasm”, the practice of essentially rebelling against the status-quo. Iconoclasts goes one further, and becomes more of a rumination on the costs and challenges of tearing down the old and the daunting task of facing what may replace it. The story takes this theme and runs with it, depicting a world overseen by a fascistic militia known as the One Concern. This force believe everyone need have their place in the world (naturally, not a place of their own choosing), and will rain down “Penance” upon the homes of anyone who steps out of line. Despite their ranks consisting mostly of visor-clad grunts in grey, they never quite feel like a generic group of baddies, as their grip of terror comes with a religious undertone, spooking the citizens into paranoia of violent reprisal at the hands of the divine being the One Concern follow. As Robin, the daughter of a deceased mechanic now illegally fixing all manner of problems in the settlements, you attract no small amount of disdain from the citizens, who'd much rather you packed in the unlawful assistance and settled down. Naturally, this doesn't quite happen, and Robin soon finds herself becoming a one-woman resistance against the Concern, aided by a handful of similarly aggrieved allies along the way.

Iconoclasts' storytelling feels distinct and notable for a number of reasons, but first and foremost it's surprising the lengths that Konjak has gone to to develop a layered narrative in a genre where traditionally no-one bothers. The game is still driven largely by its tight platforming and satisfying puzzle-based progression, so with those successfully built you could forgive the plot for being fairly obvious girl-defeats-big-dragon fare. But here, Iconoclasts' feels eager to be seen as newer, fresher and more relevant. The characters aren't happy-go-lucky, but often filled with grief, terror and rage, and it all acts as a compelling motivator beyond filling out the map screen or crafting another upgrade. Having large boss battles with their impressive levels of animation and challenge accompanied by a sense that the characters have been through a great amount to reach the confrontation makes Iconoclasts feel more mature than its inspirations, even as you're throwing down with a giant cat or caterpillar.

The writing is sharp and sweet, not lingering on any point for too long so you're back into the action in due time, whilst never feeling perfunctory enough to make you want to hit Skip anyway. It feels tight; a feeling that permeates through most of the game. It never goes overboard with the number of characters you meet or are expected to remember, and uses them sensibly. The leading villains of the One Concern are the highlight, appearing throughout the entire game more-or-less as recurring showdowns, a constant thorn in Robin's side (and vice versa), and a font of expression for the game's themes of idealogical decadence and implosion. Much as the One Concern bleed the planet dry of its most essential materials, Iconoclasts bleeds its characters dry for drama and intrigue, giving each character exactly enough screentime to make a strong, lasting impression.

“Making the most of what you have” is a running theme in this game, reflected not just in its use of character but also location and mechanics. Robin is equipped with a stun gun and a wrench, and for a lot of the game, that's more or less it. She eventually gets a bomb launcher, and a third weapon type I won't spoil, but that's her lot. Iconoclasts isn't interested in giving you a huge arsenal, because you don't need it. Instead, the weapons serve primarily as solutions for the game's puzzles, and in combination with a couple of wrench upgrades giving Robin electrical properties, Konjak gets a LOT of mileage out of these tools. Robin's wrench lets her tighten bolts to activate level elements, as well as swing off mid-air bolts to reach higher ground or clear chasms. This movement feels exquisite, with your momentum coming off the bolt never in question, and it combines with a auto-targeting 4-way directional aim on the stun gun for quick, speedy combat scenarios. Puzzles often involve shooting the bombs through tight gaps to create an opening, using electricity to activate switches, moving level elements around via tightening bolts – how to interact with the pieces of a room is rarely in question, but the number of combinations of bomb-powered platforms, mid-air bolts, electrical switches, tight platforming and certain enemies feels limitless thanks to Konjak's incredibly inventive level design.

When you're not using the few tools at your disposal to blast through puzzles, there are plenty of enemies to take down instead. Standard cannon-fodder is found in a lot of rooms, but the game offers a tricky parry move and a mid-air stomp for defeating a variety of enemies that can't all be K.O.'d with a volley of stun-gun blasts. Keeping on brand, it never goes overboard with the number of enemy types, but Iconoclasts is smart enough to make sure each of the 7-or-so areas of the game has their own distinct fauna, such as skull bats in the dank flooded caves or bizarre bipedal cacti in the desert, each with some killer animation tooled for high readability and expressiveness. The bosses are by far the peak of the game's gorgeous sprite-art; screen-filling titans lumbering toward you with equally screen-filling attacks, and lithe assassins striking fast and hard as they leap between the sides of the screen. One highlight is an enormous caterpillar train operating in a circular forest area, chasing you down as you use your wrench to zip along magnetic rails; another, a flaming-hot femme fatale who rains hot death from the sky as you attempt to knock her into electrified railings. Each boss tests your reactions and pattern-reading skills in diverse ways, often offering allies to further differentiate encounters with their own special means of assistance. They're all instantly memorable, from the initial giant mech showdown to a frankly ridiculous ultimate confrontation that might leave you equally perplexed and enthralled.

Iconoclasts mixes up its combat and movement with its “tweak” mechanic, giving the player three perks to use in their journey. These can include defensive measures, speeding up weapon cooldowns and even making new moves available, like a handy dodge roll. Unfortunately, taking damage causes these abilities to become disabled, only becoming active once more by grabbing “ivory” dropped by enemies or from smashed or fixed objects. Iconoclasts' difficulty level isn't punishingly hard, but it's challenging enough where you'll take your fair share of scrapes, and losing useful skills such as speed boosts or attack boosts due to mistakes can be irritating. This mixed together with the fact tweaks must first be crafted using secret collectibles – and can only be crafted once their blueprints have been obtained – makes the tweak system feel more frustrating and underutilised than it could have been. Acquiring tweaks has enough barriers to entry that removing the ivory requirement wouldn't be overly generous – as it is, it never feels enough of a boon to making secret hunting anything more than its own reward.

That concern aside, Iconoclasts is an impeccable result of its 7-year development history. The story of Iconoclasts argues simply in favour of doing the right thing – not settling for quiet subjugation, not rioting against the status quo just because, but simply identifying something broken, and getting to work fixing it. In looking at the classics of video game yesteryear, Konjak clearly didn't see much broken, but what there was, the game makes a valiant effort at fixing. A tight compelling story, a rejection of empowerment-based progression in favour of a puzzle- and boss- design focus, impeccable movement with smart quality-of-life choices and a look bursting with colour, detail, blood, sweat, tears and love – in sticking to doing a few things really, really well in surprising new ways, Iconoclasts is the most successfully ambitious action-platformer I've played in years, and a game I've been wanting for a long long time.

Score: 5/5

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My 10 Favourite Games Of 2017

This list was originally posted on the forum Resetera, but I felt like putting it up here too, with a little more insight into why I liked these games so much, and so they don’t get lost in the muddle of forum posts. Enjoy!

10. Snake Pass (Sumo Digital; Nintendo Switch, PS4, Xbox One, PC)

Sumo Digital has been a developer I've admired for years, particularly for their work on the Nintendo-tier kart racer Sonic & All-Stars Racing Transformed. Snake Pass is their first independently-produced title, and it has a great hook - the player controls a snake in much the same manner as a real snake might move. There's no jump button, no Earthworm Jim spacesuit, just the power to raise one's head and the strength to grip tightly to any object you've coiled around. There's no timer or enemies; Snake Pass is content to let you explore its levels at your own pace, letting you getting used to its unique feeling and take in the calming David Wise soundtrack. It's a game that feels like learning to ride a bike again, and the progression in ability over time is such a pleasing sensation that it earns it its place on this list by itself. The good use of collectables and generous helping of levels is icing on the cake.

9. Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus (MachineGames; PS4, Xbox One, PC)

B.J. Blazkowicz returns and he's lost all meaning of subtlety whilst he's been out of action. Wolfenstein 2 shoots all of its shots - the action is bloody, explosive carnage, and the subject matter isn't satisfied with just skewering Nazi idiocy and narcissism, taking time to shine a light on White America's love affair with sitting back and reaping the rewards of compliance under fascist rule. Whether it's exploring B.J.'s broken psyche, giving Wyatt a crash course on hallucinogenics or putting you under the spotlight in a terrifying audition, MachineGames refuse to pull their punches, each great moment coming swinging like B.J.'s Nazi-reprimanding fireaxe. The combat encounters are far from polished, with stealth being heavily nerfed from The New Order and the half-way shift in tone from borderline-satirical diatribe on mortality and American race relations to comic-book capers is incredibly stodgy, but Wolfenstein 2 leaves a hell of an impression all the same. Shame about that credits music.

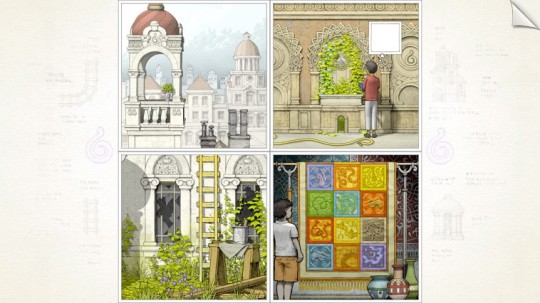

8. Gorogoa (Jason Roberts; PC, iOS, Nintendo Switch)

A good puzzle game can make a really strong impression, guiding you subtly by the hand to make you feel like a member of MENSA just for pressing a few buttons or prodding at a screen. With Gorogoa, I can't even begin to describe how the puzzles actually work. Imagine a window segmented with 4 panes of glass, and now imagine you can drag elements out of those panes and into other panes, or over where there isn't a pane to create a new pane... See, it’s hard! In as simple terms as I can muster, it’s a game about taking the world apart and putting it back together again to create paths and progress for your anonymous young hero. It’s intensely abstract, yet the South Asian aesthetic feels like a living locale, an exploration of a boy's days-to-come. It's a short experience, but with each puzzle solved making me feeling smarter than Albert god damn Einstein, it's one that will stick with me for a long time.

7. Splatoon 2 (Nintendo EPD; Nintendo Switch)

Like pretty much everyone, I didn't own a Wii U, but the sting of that decision never really happened until the arrival of Splatoon - Nintendo's first proper new "core" universe since what felt like Pikmin. It instantly looked like sheer fun - and as a big fan of both Jet Set Radio and The World Ends With You, it was clear as day Nintendo's younger designers were picking up the Shibuya fashion torch those games dropped behind them. Put simply, it's totally my shit. Splatoon 2 confirms my suspicions and then some, being the first multiplayer title I've enjoyed online in forever. I can't get enough of the soundtrack, the sound effects, the amazingly catty banter between Pearl and Marina, and just the feeling of dropping into ink, strafing around a sucker and blasting them straight between the eyeballs with my N-ZAP '85. 20% of Switch owners in the US can't be wrong.

6. Yakuza 0 (SEGA; PS4)

The only games I've played previously by SEGA's Toshihiro Nagoshi are the brilliant arcade/Gamecube bangers F-Zero GX and Super Monkey Ball 2, plus his one-off PS3 sci-fi shooter Binary Domain. Loving those 3 wacky games, I always felt a little put-off by his regular gig nowadays being a series about Japan's most decorated crime organisation, and a bare-knuckle brawler at that. Yakuza 0, the 80s-set series prequel that serves as a perfect entry point for series newcomers, proved my suspicions ill-founded. It's a game which instantly casts the majority of the yakuza as control freaks and bullies, pits its protagonists Kiryu and Majima as their unfounded targets and pawns... and then lets you fight your way out of hell via brutal finishing moves, bizarrely complex business management sidequests and, if you're so inclined, a gun shaped like a giant fish. It's that kind of game that always keeps you guessing whether or not you should take it seriously, and so it wins you over with its best-in-class action choreography, astonishingly good direction and a never-ending deluge of sidequests, minigames and challenges. Don't sleep on Kamurocho.

5. Sonic Mania (SEGA/Christian Whitehead/Headcannon/PagodaWest Games; Nintendo Switch, PS4, Xbox One, PC)

If you’re reading this, you probably know I'm a Sonic apologist. I don't really stand by the 3D entries - bar Sonic Generations, which I genuinely love - but the narrative that "Sonic was never good" is some ridiculous meme that I can't stand. They were genuinely fun games, albeit far from perfect; every game can use some improvement. Sonic Mania is that improvement, spinning the level themes and gimmicks from the original Mega Drive (and Mega CD) games into vast new forms, with myraid routes, tons of secrets, an astonishing sense of speed from beginning to end and fairer, more agreeable, more exciting level design. Old locales, new levels - oh, and some new locales as well, one of which (Studiopolis Zone) is an instant classic. 16:9 presentation, all new animations and crazy levels of animation detail, and a mind-blowing soundtrack by Tee Lopes - Sonic Mania is the perfect Sonic game.

4. NieR: Automata (Square Enix/PlatinumGames; PS4, PC)

For my first foray into the sunken mind of Yoko Taro, he couldn't have left a better impression. NieR: Automata uses Platinum's engaging-at-worst, thrilling-at-best melee combat as the language to tell his new story of how pointless it is for anyone to even bother throwing themselves after ideals of society or humanity, and why it's worth trying all the same. Every inch of this game feels crusted in Taro’s sensibilities, with the no-bullshit 2B and her curious whiny partner 9S running into robots waving white flags, avenging fallen comrades, establishing monarchies, throwing themselves to their deaths, and coming to terms with their crumbling existence in apocalypse. It's crushing, it's raw, it's often dull, but its uniquely bleak vision of AIs breaking free of their programming has a grip as powerful as a Terminator's. And when it’s ready to let you go, it has you send it off with the most memorable credits sequence in history. Glory to Yoko Taro, glory to PlatinumGames - glory to mankind.

3. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (Nintendo EPD; Nintendo Switch, Wii U)

Standing in the centre of a bridge connecting Hyrule’s broad, emerald green fields to the desert mountain approach, a bridge overlooking the still Lake Hylia, I fire an arrow into a lizard bastard’s head, or at least I try to. He dodges it and rushes me, forcing me to jump away and retaliate with my claymore. Out for the count, I resume looking for the lost Zora wife I’ve been asked to seek out, who apparently washed all the way downstream in a recent downpour. I can’t see any wife - my entire view is dominated by the giant green dragon snaking across the night sky above me. The wind picks up, but I am too awestruck by its presence to take note that I could glide up to it and shoot off a valuable scale. Instead, I just stand and stare, this utterly unexpected moment happening before my eyes. Friend or foe? A boss monster, perhaps? A vital story element later on? The answer ended up being none of the above: in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, there be dragons, and that fact in and of itself speaks volumes about what this game is about. After 30 years, Hyrule finally feels alive.

2. Night in the Woods (Infinite Fall; PS4, Xbox One, PC, Mac, Linux, Android, iOS)

Very few games instil a genuine emotional response within me, but the story of Mae Borowski's no-fanfare return from college to suburban gloom resonates hard with me. It's an expert at the little touches - the needless-yet-fun triple jump, the not-so-starcrossed rooftop musicians, the impulsive reaction to poke a severed arm with a stick - and woefully precise with its big swings, like an upsetting cross-town party, a wave of violent frustration amongst the townspeople, and the inability to just lay it all on the table with friends and family when you need to most. In the cosmic dreams of shitty teens, Night in the Woods finds an ugly beauty in depression.

1. Super Mario Odyssey (Nintendo EPD; Nintendo Switch)

It’s impossible to deny 2017 has been the year of Nintendo. There’s plenty of celebrate elsewhere, but the Switch’s rise to prominence as the machine to be playing ideally everything on, and the amount of absolute smash hits Nintendo has producing this year makes it hard for the narrative to focus elsewhere. The epitome of all this is their final killer game of 2017: Super Mario Odyssey, the grand return of a more open-ended style of Mario platformer. A true blue achievement in joyous freedom, it brings together everything from Mario's history of 3D platforming - 64's freedom, Sunshine's other-worldliness and sky-high skill ceiling, Galaxy's spectacle, 3D World's razor-sharp platforming challenge - and throws into one big pot, creating a Mario where both the journey and the destination are one and the same, and exciting to the very end. In a year of amazing games that hit upon horrid, upsetting themes with delicate, pinpoint accuracy for tremendous success, I’m not sure whether it’s a shame or an inevitability that such an unapologetically surprising, happy game made the biggest mark on me this year, but either way, I’m welcome to have Mario be truly Super once more.

#goty#2017#splatoon2#super mario odyssey#zelda breath of the wild#yakuza 0#night in the woods#snake pass#sonic mania#gorogoa#wolfenstein#nier automata

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New B.J.: How “Wolfenstein II” Remakes & Undoes Its Hero

Thar be spoilers ahead for pretty much all of Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, plus parts of Wolfenstein: The New Order too.

In Nazi-occupied Roswell, New Mexico, 1961, the former US special forces Captain “B.J.” Blazkowicz – protagonist of last year's Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus - is in a unique situation. Transporting a disguised nuclear payload in a fire extinguisher, he masquerades as a fireman through the town to a meeting point with a fellow resistance comrade. Fascist stormtroopers line the curbs, the KKK wander hooded and confident, and the town's women discuss their purchasing ambitions at the local slave market. The shock is in how leisurely this little piece of American soil has taken to complete white supremacy, but the moment is compounded by one uncomfortable truth – for once, for now, BJ can't fight back. Helmet down, eyes forward – at least to begin with, this is a sneaking mission.

One of the better qualities of many of the best games this generation has been the ways in which designers in both the AAA and independent spaces have moved on from traditional (some might say stereotypical) notions of what games are. The big man with the big weapon, mowing through villains with zero shades of grey and an infinite volume of blood to spill, it's a cliché but absolutely a prevalent one throughout games. In 2017 in particular, games felt more comfortable to populate popular genres with playable minority characters, and men & women with more believable, nuanced backgrounds beyond “murder purveyor”. It's been a growing trend for years now, but diversifying leads has reached the point where the big man with the big weapon is able to carve out an acceptable niche, and itself diversify within it.

2014's Wolfenstein: The New Order makes no bones that their protagonist is a shoot-first type of guy, a welcome break from the more modern action protagonist who regrets every bullet he fires (hello, every Rockstar Games lead character post-2008), but they smartly make sure to give B.J. something, anything else to do. In that game, it was the Kreisau Circle headquarters hidden in Berlin, which he could explore, check up on his comrades and get a better sense of the people taking up arms with him. “Slight” is the word, these moments taking place between missions and giving the player an opportunity to breathe first and foremost, but the mere opportunity to define B.J. in any way outside of emptying a gun into a fascist is a vital change for both B.J. historically and the wider notion of a male action hero in games.

In these moments, and the similar U-boat-set interludes in the sequel, B.J.'s masculinity is arguably more defined than almost any other video game protagonist. The Berlin HQ and the U-boat offer a variety of good deeds for B.J. to participate in – giving Max Hass his lost toys back, feeding the boat's pig, dealing with a rat in the armoury, locating a tertiary rebel's lost wedding ring. It's standard side-quest fare, but the irregularity of these moments, and the solid, emotional performances of the characters B.J. is aiding builds him up as more than the best gun on the team. B.J. is a protector, the fuel that keeps things running in the resistance and the medicine that patches it back up when it's damaged – regardless of how damaged B.J. himself is. It’s an obvious male stereotype, but one that feels refreshing in the context of a violent action game, or at least is delivered with more warmth than any other attempts.

His newly-defined paternal nature is made more explicit in the sequel, which makes him a father-to-be. His lover and comrade from The New Order, Anya, is now pregnant with twins, and suddenly B.J.'s role as a familial protector is no longer subtext. It brings upon the confrontation with his father, a man whose protective nature extended only as far as his beliefs and racial insecurities; it leads him to grapple with his mortality when once again going toe-to-toe with the Nazi forces; it contrasts deeply with the farewell of Caroline, the leader and friend he couldn't protect, and the arrival of Grace, their new leader with a child of her own yet an unshakeable temperament for leadership. For much of Wolfenstein 2, B.J.'s confidence as a man is shaken by his uncertainty over his and his children's future.

Back to Roswell. In the game's quieter moments, mostly taking place on the U-boat, B.J. is amongst friends and allies, and he can be himself in the aforementioned more subdued ways. He can't fire his weapons here, but he can still be of use, use his later-game abilities to aid folks in need, or simply have a conversation with the other rebels. Roswell's opening downtown jaunt is far less interactive, but this is where B.J.'s damaged masculinity shines – it's the first moment in a long time where he is out of options to rebel against the setting he finds himself in. Even when B.J. breaks into a concentration camp in The New Order, he is only there to bust it wide open – he doesn't even complete his short time operating the prison machinery without breaking it for his own ends. In downtown Roswell, B.J. is simply passing through, without any option to immediately fix (or break) what is happening around him. It's a sharp contrast for a man who usually answers with the business end of a shotgun.

Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus repeats this trick a few times. It's a shooter with things to say, and it's unwilling to sacrifice the things that made Wolfenstein popular originally to say them, so its default speed is set to an average of “killing 5 Nazis in the space of 20 seconds”, with brief moments of quiet for characters to breathe and by themselves between the bloodshed. But B.J.'s character is being to feel somewhat threatened by Wolfenstein's legacy. As they develop him into a more well-rounded person, they use his dyed-in-the-wool masculinity to further that and to give him interesting allies to rub up against. A rendevous in New Orleans sees B.J.'s charging personality at odds with the socialist firebrand Horton, who saw the Nazi regime as just the logical extreme of America's own recipe of white supremacy and unfettered capitalism. B.J.'s not politically minded, so he sees the socialists as a bunch of yellow-bellied commies who didn't put their guns where their mouth was when it mattered – citing his unborn kids as his motivation for fighting the good fight against unspeakable odds, he's there to deliver the stern talking-to a fair dad might give an unruly son. It's a great moment where the bloody battles beforehand make the drunken back-and-forth B.J. finds himself in all the more comically frustrating, and a rare instance of B.J.'s personality outside the gameplay meshing well with his minute-to-minute gunfighting.

Emphasis on rare. The problem with B.J.'s gradual shift in pitch from “badass WWII spy” to “still badass, but also wounded and affectionate and contemplative” is that “badass” suddenly has to be amplified to make sure people know it's still Wolfenstein. As mentioned prior, it's still an interesting, ironically uncommon direction to take in keeping Wolfenstein an explosive shooter, but after a while it begins to feel a little odd that this increasingly complicated character is throwing himself into such volatile situations. In Wolfenstein 2's first half, B.J. is broken, grieving and ready for the end, and the game's environments – besides Roswell's disgustingly comfortable streets, there's the nuclear wasteland of Manhattan and the Nazi-riddled U-boat interior – feel cold, grey and uncaring. It fits his mood. Following the game's midpoint twist, however, B.J. gains a new body, and suddenly he can go back to killing Nazis more efficiently than ever. He goes to the New Orleans ghetto, but after that he sneaks on board a spaceship to Venus and eventually has a go at taking over the Nazi's sky-bound mobile HQ in America. It seems outlandish, and through much of the game it was hard to feel out why. Was this story always this silly?

The New Colossus puts B.J. up front in narrative terms, and this is where the cracks begin to appear. Previously, the ally characters provided personality and warmth where B.J. couldn't afford to. Now, B.J. isn't just the rejuvenated hero kicking all the other would-be Nazi hunters into action, he's also a passionate father figure, a man with a broken past, AND a seasoned fighter familiar with both ends of the entire Nazi arsenal and beyond. Having a three-dimensional lead in a first-person shooter is certainly appreciated, but he can't exist in limbo; the wider game needs to be one this character can believably exist within. As it is, Wolfenstein 2 uses its gunplay to sell B.J.'s combat prowess, and only concerns itself with his fatherly concerns, love of his comrades and his broken past when there's no nearby Nazis to turn to mush. The scenarios he finds himself in don't feel inappropriate for the character in the level of violence on display – they're Nazis, etcetera – but in the carelessness of how B.J. operates. Roswell stands out as a lone area where B.J. takes a more sensible approach, but it feels static and distant due to the lack of interactivity; whilst the scenery and B.J.'s inability to fight back generate tension, it makes it feel more than ever like B.J.'s incapable of outside interaction beyond spraying lead death. Even when B.J. finds himself infiltrating Nazi compounds such as on Venus, his plan for completing his mission rarely goes deeper than “gun my way over to this person or objective”, and the stealth options feel neutered compared to “The New Order”. The options are available, but they're difficult to pull off, and imprecise – the game feels like it wants to you take the guns blazing approach, and rarely does this feel tactical or..., well, safe. As a father reckoning with his limited mortality early in the game, the B.J. at the end of Wolfenstein II feels like someone taking it remarkably for granted that he'll live to see his children grow up.

It doesn’t quite ring true, and so as the characterisation has improved, so must the level design and the feel of the game improve to keep pace. Great games are rarely merely the sum of their parts, and Wolfenstein 2 is the perfect example of that, so devoted to this brilliant image of its protagonist yet only doing half of the work to make him feel real. Working within the scope of a old-school shooter is holding the character development MachineGames holds dear back, and I would hope the final act of the trilogy no longer sends B.J. to places he needn't go with plans he doesn't have. His masculinity doesn't suffer for his approach not always being a dual-wielding shotgun one, and if B.J. is to be a father, the responsibility that implies should be reflected in the paths he (and the player) walks. Wolfenstein 2 is overall a heck of an experience, but in the finer details it feels a little exhausted and polarised. B.J.'s figured out the man he wants to be – let's see if MachineGames can figure out the kind of game they want Wolfenstein to be.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t Call It A Throwback

The “new old” is a phenomenon hardly unique to games, but a large corner of the medium can be identified as an intentional recreation of interactive entertainment's past. In film you have the 2011 silent film The Artist, in traditional art you naturally still see paintings in the style and approach of painters from centuries ago, and popular music is nothing if not big on recycling past sounds – just look at the turn-of-the-decade revival of 80s synth sounds in the UK. But it's in games where the past isn't so much referenced for new inspiration as it is recreated wholesale; brought out of the loft, dusted off and presented anew for a new generation of players.

Just look at the number of older games re-released in some form over the last 12 months. Off of the top of my head, I can think of Final Fantasy XII, the original PlayStation 1 Crash Bandicoot trilogy, Okami, Street Fighter 2, Pokemon Gold & Silver, PaRappa the Rapper, Yakuza (as Yakuza Kiwami), Mega Man 7 through 10, Full Throttle and the swathe of games released under the Arcade Archives and SEGA Forever banners. These releases include remasters (preserving the game with technical enchancements), remakes (building the game anew from the ground-up, often with new features) and more-or-less straight dumps of the original code running on emulation software. Whatever the format, publishers and developers are now fully committed to the notion that bringing old games to new platforms – and new players – is a winning strategy.

This is nothing new, of course, as anyone who remembers Super Mario All-Stars or the glut of Final Fantasy collections on PS1 can attest to. But classic titles working their way into the catalogues of new consoles does create an interesting juxtaposition in 2017 – as technology improves and games get more sophisticated, and new design trends emerge, what purpose does making old games readily available serve? Many new titles supplant or enhance their gameplay – of the above franchises mentioned, Pokemon, Final Fantasy and Street Fighter never slowed down, and games like Parappa and Full Throttle evolved into modern day titles like Rock Band and Telltale Game #353 Episode 1. So is it really the classic game feel that people are seeking? Or is the pull of an oldie simply born out of rose-tinted mythologising?

A handful of titles released in the last year make the argument that, actually, it's both. In 2017 SEGA released Sonic Mania; Terrible Toybox released Thimbleweed Park; and Playtonic released Yooka-Laylee. Each of these titles exists solely to recreate a particular style of game from history in the style you remember it, positing that, yeah, these games did play well, and still do. They occupy a fascinating space between ruthlessly chasing the cutting-edge, evoking classic gaming to explore more contemporary design like so many independent releases do, and bringing old titles to new platforms. In rebuilding a piece of the past that was left behind, each title ends up standing out as more interesting than they otherwise may have been in their heyday, or if they simply conformed to the modern-day standards of their genre playmates.

Let's start with Sonic Mania, a game that feels like it should have existed years ago in two ways. Firstly, it's a clear continuation of the original Sonic The Hedgehog platformers from the Mega Drive – a mission statement of the developers being to create the Sonic that the Sega Saturn never got to have. This results in a game that looks dazzling, and yet in line what with came before – this is Sonic The Hedgehog 2 with far more detail (and an extremely welcome 16:9 upgrade). This is a defining trait of the “new breed” of retro, in that it keeps what worked about the original games visually, and buffs it to a shine without it becoming unrecognisable. Sonic has always enjoyed rich sprite work and detailed backgrounds, and Mania feels as good on the eyes as players in the 90s maybe remember those original titles looking. You can imagine it being around circa 1996, blowing minds with new visual tricks like silhouettes, polygonal special stages and Sonic, Eggman and the gang's gorgeous animations – just looking a bit fuzzier on a CRT, of course.

Sonic Mania feels remarkably overdue in more recent terms, too – it has a slavish adherence to how Sonic span, rolled, bounced and launched in the Mega Drive/Mega CD quadrilogy, making the hedgehog feel better in the hands than he's felt in years. Dodgy physics and a wrong-headed speed emphasis in modern Sonic titles should have provoked a re-examination of the classic title's feel a good while ago. It's a cliché in Sonic conversations that the new is in the shadow of the old, but the idea that design progression does not necessarily mean a genre has objectively improved is a good one to keep in mind, despite it being otherwise scarcely considered. Mania doubles-down in proving the original Sonic feel needed a second outing; the physics and level design philosophy resurrected, developers Christian Whitehead, Headcannon and PagodaWest polish their levels with modern considerations including a dearth of cheap tricks, more inventive level gimmicks than those seen in the originals and an aural accompaniment that bridges poppy jazz, fidgety hip-hop and slowed-down mood music. It feels “old”, but almost only ever in ways that make the whole endeavour fun and surprising.

Thimbleweed Park mostly follows that same philosophy, and is largely as successful with it. Thimbleweed is an adventure game ripped straight out of the late 80s and mid-90s, complete with roughly a third of the screen lost to an ever-present inventory and list of possible actions. Akin to Maniac Mansion, you have a handful of characters to use at any time, and progression requires solving puzzles that tend to require an item being used in a particular way on a particular object or character. Like Mania, Thimbleweed takes that structure – one that used to too often be riddled with obtuse puzzles married to logic from the thirteenth dimension – and refines it, with puzzles following more earthbound ways of thinking and a handy hint system riffing on the old hint lines that no doubt rang up some hefty phone bills in the point'n'click heyday.

As someone who was born the year before Day Of The Tentacle released, I've had to experience classic point'n'click through reissues, which has occasionally been a frustrating experience. Thimbleweed felt like a more comfortable ride, a game I saw through to the finish with the right ratio of time being stumped and time making progress. The game has a lovely, corny sense of humour that always feels to follow Lucasarts' (and Double Fine's) games about, and the game's look is gorgeous sprite work – again, like Sonic, this is an old aesthetic as they truly imagined it. The game isn't necessarily a better time than, say, Day Of The Tentacle – it's not as funny or as clever at its heights, and the ending is maybe a little too self-indulgent – but its flaws never felt like they came from its inspirations. This type of adventure game, a remotely hands-off experience with plenty of opportunities for experimentation and getting stuck, felt relevant again.

Having not played Yooka-Laylee, I can't comment too much on its success, but based on commentary it sounds rather similar to something I have played – 2008's Mega Man 9, one of the earliest original titles to turn back the clock on gaming's progress. That game was brutal – its 8-bit style offered minimal improvements over what was capable on the Nintendo Entertainment System, and so did its gameplay, full of rock-solid boss encounters, pixel-perfect jumps and overwhelming enemy opposition. It felt like an old Mega Man game, but as someone who only played their first Mega Man game in 2007, it felt /exactly/ like a Mega Man game – my time with Mega Man 3 (that is, dying a lot) was more or less the same time as I had with MM9. It felt squarely for classic fans – a novelty, though undoubtedly a well-made one. As far as the commentary I've seen surrounding Yooka-Laylee, it sure sounds similar, stringent design authenticity taking the place of considered design. I don't want to write off a game I haven't played, but as exciting as the new breed of “original throwback” is, this is an important pitfall to signpost.

There are other examples of this kind of throwback, of course – 2014's Shovel Knight is a keenly-made mash-up of elements of Castlevania, Ducktales and Zelda 2, and like Sonic and Thimbleweed it beautifully maintains a era-appropriate look whilst working with more colours and on-screen objects than that hardware could manage. Its level design is tight, challenging whilst constantly incorporating new ideas to keep the whole thing fresh. It's a bizarre concept, a game on the surface unnecessarily slavish to the old school ending up feeling refreshing in the finer details and overall experience, but Shovel Knight, Sonic Mania and Thimbleweed Park all manage to pull this off with aplomb, and they set an exciting precedent for die-hard fans and embattled veterans to spruce up long forgotten gameplay styles. To answer the original question, is there an appetite for the way old games play? Sure – but a side of 2010s artistry sure helps it go down well.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Fleeting Thoughts

Just a quick sampling of thoughts on various game stuff I wouldn’t throw into a wider post:

- Eurogamer is reporting that Lego Dimensions has bit the dust, an eventuality that its complete absence at E3 more-or-less gave away, but it’s sad to hear nonetheless. Of all the toys-to-life nonsense that has appeared over the last 5 years or so, this was immediately the most appealing, if simply because it was designed with weirdo inter-brand mismashing in mind. Sonic referencing Simpsons jokes is the kind of silly ambition that licensed games should be going for if they’re going to play fast and loose with the source material - which Warner Bros. are wont to do. It was simultaneously the most accurate of licensed game - the Lord of the Rings world featuring Minas Tirith as you remember it in the films - and the goofiest - you could fly past it in the TARDIS. It was a lot of fun, but it definitely ran its outrageously expensive course by time the Sonic pack landed, and I’m glad to see it fizzle out with no apparent lasting damage to Traveller’s Tales.

- Picross S is a fun puzzle game on Switch for £7-ish. That said, I’ve played a lot of these games on 3DS and this one feels a bit... lacking. I’m not a huge fan of how the penalty system comes and goes between these games, and this edition leans too hard on the frankly-not-that-fun Mega Picross mode. The presentation being ultra minimalist I don’t mind, as I’m playing it while watching streams or TV, but I do hope the inevitable Picross S2 has a bit more going on.

- I’m still playing Zelda despite originally planning to put it down until the DLC arrived, as it’s hard not to slip back into that world. The amiibo stuff is very convenient and I hate that I have so many nonetheless. Probably my favourite this year (sorry NieR).

- I’ve downloaded Thimbleweed Park, despite not really being good at adventure games at all, but I’d heard nothing but good things and wanted something noticeably different tonally from what I’ve been playing this year. I’ll likely write a review of it at some point!

0 notes

Text

A Wild Rebellion: Breath of the Wild, Majora’s Mask and the Value of a Sad, Mad World

The Legend of Zelda has a knack for memorable beginnings. Be it a old man in a cave passing you a much-needed sword, or the patter of rain on your window as a princess' desperate plea for help pulls you from your dreaming, the series has often excelled at setting the stage for the scale and urgency of the quest to come. Despite this, the 2000 Nintendo 64 title The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask has a sharp opening salvo that sticks out amongst its series fellows, even 17 years and 12 games later. Far from the call to adventure and heroism most Zelda games open with, it features a Link on the brink of puberty robbed of his horse, his magical ocarina and - as punishment for pursuing his attacker - his human form. The game later reveals that the moon is falling, and Link must relive the same 3 days until he is prepared to stop an otherwise certain apocalypse, but even this level of dire circumstance feels natural following such an abruptly violent start. At the time, and even to this day, Majora's Mask's opening moments are Zelda's rude awakening.

Fast-forward to 2017, and the release of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Every Zelda title in the space between Majora and BotW more or less begins the same way. Link wakes up in his home, usually living in relative harmony in Hyrule or some other idyllic retreat, and finds his peace eventually disturbed by an invasive danger – emphasis on “eventually”. Even in the self-proclaimed “darker” entry Twilight Princess, the notion of terror and death is not the norm, with the encroaching Twilight Realm presenting a vicious challenge rather than a certain fate. Breath of the Wild breaks from this de-facto tradition in its own way, with Link waking up yet again – but this time, in a watery grave, in an alien room with pulsing neon lights and no friendly faces to greet or berate him. He has no memories to his name, almost as many clothes on his body. It's not just a clean break from recent tradition, but an aggressively stark subversion of the same. (Even series producer Eiji Aonuma noted how the game still began with a waking Link.)

The opening moments of “Majora's Mask” and “Breath of the Wild” have little in common in literal terms, but they share a rebellious heart in throwing off the shackles of Zelda's norms. What makes these openings important is how their respective tones of violent tragedy and hazy mystery seep through the rest of the game – and how they keep upsetting the usual Zelda order at every turn. It is this attitude to Zelda's norms that makes these games so special – and it is through rebellion, not adherence, that they fulfil the true promise of Zelda more thoroughly than any other so far.

The biggest decision Nintendo made with both of these games that sets them apart from the rest is their tone. Zelda games are traditionally steeped in valiant heroism, which sees Link making his way over Hyrule, thwarting evil and solving problems everywhere he goes. Peace is the norm, and the people of Hyrule live idyllic lives, albeit usually disturbed by whatever that adventure's antagonist may be. As established by their openings, and quickly expanded upon once Link encounters true allies to explain just what kind of hell he's in, “Majora” and “Breath” share ambitions of a much greyer tone.

Both are a far cry from Zelda's usual black-and-white Good Vs Evil fare; Evil's devastation is a looming certainity up until the very last impossible minute in the former, whilst Good's defeat is a centennial truth in the latter. These contexts linger throughout what feels like every moment of the game, with Majora's Termina feeling like an eternal tumble through the five stages of grief, while Hyrule in Breath has a sombre air, a world violated putting on a brave face.

What these grimmer backdrops afford Nintendo's designer is significant. Characters burst with purpose – previously, all an NPC needed to do was stand around, offer idle chit-chat and functional advice, possibly hint at the location of a secret Heart Piece. Now, they need to react to the malformed world they've been placed into, and in a variety of ways to boot. Characters in “Majora” look up at the moon some in fear, some in bemusement. The ones that have cottoned on to their impending doom squabble on what to do; on what can they do. The spectre of apocalypse inspires a different mix of emotion and reaction in each person and creature in Termina; to make this all the more believable, almost every character – certainly every human character - has a well-drawn backstory, a purpose in the world.

The carpenter refuses to leave Clock Town, his dyed-in-the-wool masculinity hardened through years of manual labour making him unable to even give the apocalypse quarter. The guards of Clock Town act as an artificial barrier to keep the shrunken floral Link confined within the game's prologue chapter, yet they too eventually stare at the moon in acknowledgement of their damned role in this town. Even the shopkeepers eventually shut up shop, fleeing Termina likely all too late to save themselves. These characters aren't just multi-faceted and sympathetic – they're relatable, as you too must contend with the impending apocalypse, more than anyone else in Termina will ever have to.

Breath of the Wild takes the idea of Hyrule's people as, well, people, and runs with it. Stripped of Majora's repeating three-day countdown to calamity, it's understandable that NPCs in BotW can't run around with unique routines and schedules, but nonetheless their more rigid nature is balanced out by leaning in hard to their purpose and personality. Stables dotted across Hyrule are the most common place to run into other people, where a warm bed, a place to cook and a friendly chat are always available. Breath's quietest subversion of what it means to run into an NPC in Zelda is the levelling of the playing field; the people you run into at these stables, and occasionally on Hyrule's well-trodden trails are explorers much like Link. They may lack his heroic purpose, instead adventuring in search of treasure, food or commerce, but when you see someone running from monsters or talking about a particular ingredient or meal they love, it's hard not to relate. You'll see travellers gathered around the cooking pot and know they're here for the same reasons you are: it's rough out there, man.

Whilst Breath doesn't give every single character a personal tragedy to overcome, their simpler lives still have the unmistakable mark of the post-apocalyptic Hyrule on them. The vibe of loss, detailed in intimate dread on an individual level in Majora, is extrapolated here to a blanket grief covering the world. It lets there exist areas of ruined buildings with no greater use than a tucked-away treasure chest or Korok seed puzzle, yet a powerful echo of the Great Calamity nonetheless. It lets the amphibious Zora treat Link's return with anxiety, his survival while their beloved princess remains murdered adding insult to their injury – a call to prove oneself that feels natural where it would normally feel arbitrary. It even feeds back into the gameplay; Link's weapons smashing to pieces, the abolition of health pickups in long grass or the extremely minimal waypointing would feel perhaps harsh against the heroic backdrop of Ocarina of Time, but this is the game where Link went toe-to-toe with Ganon once already... and he blew it.

Majora's Mask tries the same trick 17 years earlier, but it's not as solid. The apocalyptic tone of Majora feeds into all the writing, and even beyond the fear of the moon characters are dealing with a host of personal tragedies. Rescuing the Zora eggs in Great Bay from the Gerudo Pirates is necessary to access the temple, but the game doesn't even need to explicitly tell you that – instead it uses their mother's reclusive behaviour to paint it as the region's utmost concern, egging you on to track them down (sorry). This is one example within the main quest; meanwhile, you'll investigate characters such as the jilted bride, the bad-tempered circus leader or the mugged bomb shop owner out of a sense of curiosity for their troubles. These quests reward you with either a Piece of Heart or one of the many masks Link acquires, and they can include some of the most touching scenes in the game.

Well-written and cohesive as they are, outside of these stories is just typical Zelda fare. The world is navigated in similar fashion to Ocarina of Time, and Link acquires new weapons and health upgrades from progressing through the story. The dungeons can be difficult, and the time pressure does create a different sensation from usual when getting stuck, but ultimately Majora's Mask does little to stray from the Zelda model of continously empowering and rewarding Link. The game is rich in atmosphere, with the audio design putting in a lot of work setting the mood of each environment, but Link is in full hero mode here. The last quarter focuses on a canyon area home to a ruined kingdom and its undead inhabitants that refuse to move on. It's a fantastically eerie, vicious setting, reeking of regret and woe, but it's telling that the game shifts towards those Link is far too late to help; at this point, there isn't many in Termina that Link can't get back on their feet.

Breath avoids the issue of diminishing returns on its tone by further embracing the spirit of rebellion against Zelda's norms. On the surface, to compare the two you would consider “Breath” the less rebellious title, as it keeps to a “beat Ganon” plot and features many returning locations, but this is just a smart way of occasionally prodding the player and reminding them that, yes, this is Zelda. The core of Zelda is empowerment, and putting keys into locks to achieve this empowerment – in Ocarina this is overcoming dungeons and gaining new items within, in Majora this is helping people for masks with new powers (and also overcoming dungeons).

BotW handles empowerment, and the notion of “locks” and “keys” differently. Firstly it gives the player four unique skills up front to use both in the overworld and in the underground puzzle shrines. Even at the end of the game, these skills function identically to how they did at the beginning – empowerment comes from the player getting used to how they might best be used to overcome problems. The skills are keys, but even if it's clear which one the lock needs, there's still the matter of execution. Then there's the matter of weapons – they degrade, so you can't keep hold of them for long, even if they're carving through most enemies in your path. Exploring for the game's only permanent forms of empowerment, such as new clothing gear, or Korok seeds to expand your inventory, or shrines to improve your health and stamina – this choice comes with the caveat that you may lose your favourite bow or sword in the process.

The shelf date on every combat tool Link has keeps “empowerment” feeling relegated to the player's own self-confidence and knowledge of the world – even health becomes less of a safety net when stronger enemies appear more frequently the sturdier Link gets. Even the Master Sword will disintegrate for a while should you rely on it too much. Each part of Breath of the Wild is 100% invested in the notion that this is a “do it yourself” adventure, where Link has to truly prove himself through actions rather than handouts. The scenario, writing and mechanics all draw from the tone of defeat, and it reinforces their effectiveness, creating an incredibly cohesive experience – and a highly believable, intimidating world.

Breath of the Wild inherits Majora's Mask’s rebellious spirit and rejects even more of Zelda's norms, using a tonal break to introduce and contextualise deeper change than redefines what it can mean to be a Zelda game. What this means for the series going forward is hard to tell. It could be argued BotW’s tone is a result from intentionally exploring open-ended gameplay, and then finding an atmosphere for the world that felt right for the systems Nintendo wanted to introduce, but the end result is the same. If Nintendo treats BotW as a template going forward, it could run into the same problems Wind Waker and Twilight Princess had: there, tonal shifts existed in and of themselves, with the tried-and-true gameplay of previous successful Zeldas being retained and the games feeling somewhat lacking in comparison.

Consider a new emotion for Zelda. If most Zelda games are “heroic”, then Majora is tragic and Breath is melancholic – or perhaps simply wild. What would Zelda look like if the feeling they struck was fear? How about rage, or passion, or nostalgia? Take that feeling and bleed it into every element of the game design, and only then could it feel as distinct as Breath. The spirit of Zelda cannot be forgotten, but overcoming challenges and empowering the player will naturally shift dramatically under new lights. If Zelda is to keep growing, it needs to remember the lessons of Majora's Mask - ultimately, nothing can last forever.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Home For My Nonsense

Hi all!

If you’re here, you’re probably already following me on Twitter, and I’ve linked my tumblr enough times for you to wander down here. Thank you for your curiosity, and hopefully I’ll reward it. For everyone else, well, basically the same thing without the air of familiarity.

This page is going to be my de facto space for posting feelings and interpretations on things - mostly games - that I’ve been enjoyed. I’m generally playing Nintendo stuff, though I try to play a wide variety of games and I also try to other a bit of a different take on things if possible. I might also use this space to talk about TV or music I’ve been enjoying. Anyway, it’s good to have space to write beyond 140 characters. Or even 280.

Who even enjoys reading a Twitter thread anyway?

Anywho, please enjoy and like/follow/subscribe/kill me

1 note

·

View note