Text

IMPERIALISM, NATIONAL (IN)EQUALITY, AND SOCIALISM

By Adrien Welsh

The history of capitalism is marked by two major contradictions. One centres around the confrontation between imperialism and the nation, between domination and oppression, between sovereignty and subordination. The other centres around the divide between the working class and the bourgeoisie, capital and labour, capitalism and socialism. The latter is the fundamental contradiction, the one that predominates in our contemporary world.

But it so happens that the former, at varying times and under specific conditions, is the principle contradiction. This can be seen in the case of colonized peoples and nations, of states ruled by a “comprador bourgeoisie” whose subordination to the imperialist powers prevents the completion of a bourgeois democratic revolution and the process of national liberation. This was also the case for countries under fascist occupation during the Second World War.

Among those countries where the imperialist- national contradiction temporarily takes precedence over the fundamental contradiction of capitalism, we can identify Bolivarian Venezuela in its struggle against bourgeois attempts to exploit its natural and human resources for the benefit of US imperialism and its allies, or Palestine under Israeli occupation, or Western Sahara under Morocco.

Communists are thus challenged to maneuver between these two contradictions and to analyze the dialectical relationship which unites them, assessing the best interest of the working class in its struggle for socialism.

Thus, in its appeal “To the Workers, Soldiers and Peasants of Russia” at the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets on 25 October 1917, the Russian Revolution recognized for the first time the right of all nations within Russia to self- determination. This call also condemned “any incorporation of a small or weak nationality into a large or powerful State [...] regardless of the period during which this violent incorporation was accomplished, regardless also of the annexed nation’s degree of development or backwardness [...] independently of the place where this nation lives, whether in Europe or in the distant transoceanic lands.”

Through this appeal, the Russian Revolutionaries declared the right to self- determination a fundamental and inalienable principle. The Revolutionaries also did not see the problem of the emancipation of oppressed nations as a question apart from that of class, and they reiterated that this question must first be considered from the perspective of class relations, and that the unity of the working class must be prioritized over national unity.

Laying the groundwork of the national question

Before tackling the national question and its implications in Canada, it is necessary to first consider the theoretical foundations of the problem.

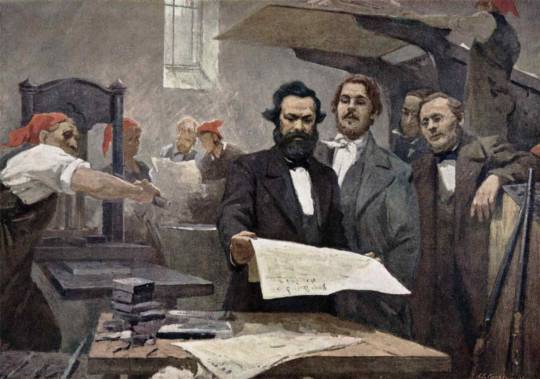

In considering the evolution of these two contradictions in a dialectical manner, it becomes clear that any analysis of the national question must emerge from a class-based perspective. Indeed, as with any other democratic issue, the national question may be approached from two different points of view: that of the working class, and that of the bourgeoisie. For us Communists, whatever the eventual conclusion of our analysis, the national question is subordinate to the class question. Thus, in order to understand the links which unite the national question and the class question, we must first define the concept of the “nation” from a Marxist perspective. Marx and Engels rarely discussed the national question as a problem in and of itself. When they did discuss it, especially in the case of Ireland, it was only occasional and on a case-by-case basis, rather than developing a specific theory on the subject. The national question only became a regular topic of discussion for Marxists later – and for good reason – following 1848’s “Springtime of the Peoples” and its repercussions in Europe and internationally. That being said, in the Manifesto, Marx and Engels had already laid the foundations for analyzing the dialectical relationship between democratic and social struggles.

It is from this perspective that, when confronted with the national question in a practical sense, many Marxists, especially those of Central and Eastern Europe (eg. Otto Bauer, the Bund, but above all Lenin and Stalin) have more systematically considered the question.

In 1912, exiled in Vienna, Stalin was commissioned by the Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) to write a report on the national question. This report would become the basis of the Marxist conception of the national question, which would subsequently be supported by various other writings, including those drafted by Lenin.

Through these documents, the nation can be understood as a stable group sharing the following four characteristics:

a common territory;

a common language;

a common economy (which does not necessarily mean a self-sufficient economy, but rather a unified economy, as opposed to the fractional one which predominates feudalism);

a sense of national belonging which manifests itself as a common culture.

From these characteristics emerges a key observation: that the national question is both objective and subjective. Indeed, as Stalin emphasizes, these four characteristics must be fulfilled for a community of individuals to be considered a nation. It is not enough to share the objective characteristics (territory, language, economy), just as it is not enough to simply share the subjective characteristic (a national culture), in order to constitute a nation. It would thus be illusory to claim that the existence of a nation may be determined independently by the group concerned, or by an outside group. Rather, the existence of a nation is based both on the subjective as well as objective recognition of the nation.

If a group lacks one of these characteristics, it cannot be considered a nation. It may instead be considered a national minority, which allows it to assert its own democratic and cultural rights (education and services in its mother tongue, cultural rights, etc.), without having access to the same rights afforded a nation.

Moreover, according to Stalin, the national question possesses a fundamental dynamism. As noted in his 1912 report, the emergence of a nation is contemporaneous with the rise of capitalism. In other words, the existence — and the relevance — of nations has everything to do with the goals of capitalism and the need to organize production within units, bringing together the exploited and the new ruling class.

The nation is therefore a historical construction specific to capitalism; the nation appears and disappears in the same way that the seigneurial system disappears with the fall of feudalism.

Generally, capitalists favour the nation state as the organizational model. Despite propaganda forwarded by the neoliberal elites of the imperialist nations and the existence of increasingly-present supranational alliances (such as the European Union), the fact is that these alliances cannot exist without the endorsement of the nation states concerned.

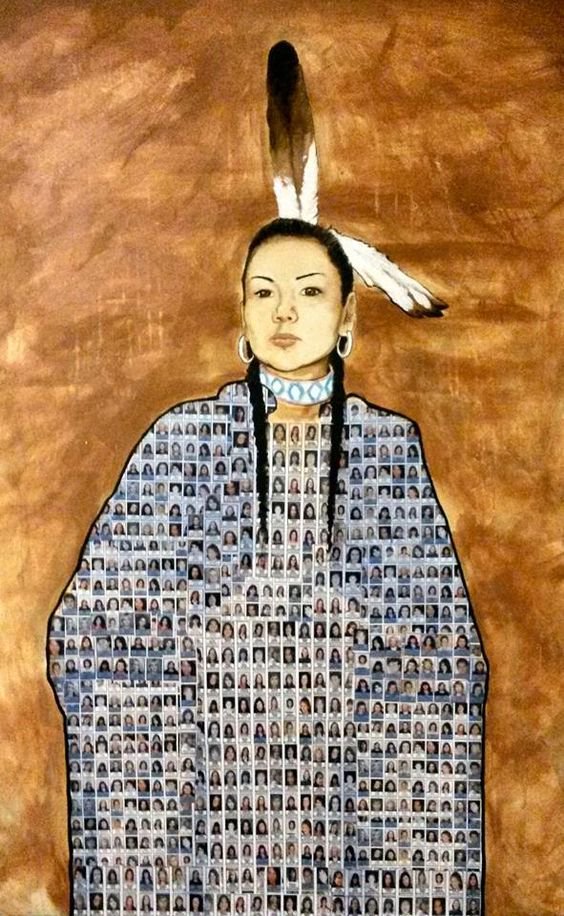

Canada, however, is an exception to this rule. Due to French colonization, the British Conquest, and the resistance of Indigenous peoples to assimilation, different nations have formed. That being said, these nations do not exist on an equal footing: aside from English-speaking Canada, none of them may exercise the right to self-determination, nor do they have the final say on broader political, social, and economic issues. It is partly on this national inequality that the first monopolies of Canada were built: the theft of Indigenous lands and genocide, maintaining Quebec in a state of economic backwardness in agreement with the bourgeoisie and the Catholic Church, all this served the interest of the dominant nation’s capitalist class.

Canada’s existence as an unequal union of nations is a central theme of the country’s politics. Therefore, it is natural that the Communist Party should have considered the national question early on.

A fundamental principle: the right to self-determination

During the course of the Communist Party of Canada’s past 100 years of struggle, the position of the Party has been refined continuously, not only through considering fundamental texts and the exchange of information, but through our practice and the ongoing wider evolution of the national question itself. But that does not mean that the fundamental principle, our guiding principle – namely, guaranteeing the right of self-determination up to and including secession, first of the French-Canadian nation, then of Quebec, Acadia, and Indigenous nations – is reflected in each of our analyses.

It is true that in our early years, this principle was conceived as secondary to the class struggle. A rather mechanistic view dominated the Party during this time: in 1929, the Report to the Sixth Congress of the CPC stated that “the struggle for free and full independence for Canada, the guarantee for complete self-determination (French-Canada) can only be achieved through revolutionary action.” Moreover, in 1934, the Party’s theoretical journal stated “While we do not make of the French question in Canada a national problem, we recognize that the French Canadians form a nation [...]. Therefore our first slogan... should be ‘The Right of Self-Determination up to Separation!’”

In the context of the 1930s, with the rise of fascism supported by the Catholic Church with its wider influence within the French-Canadian national movement (and even a portion of the labour movement), it may be said that this position on the national question was before its time. The existence of French Canada as a nation was recognized very early on by our Party – well before any of the other federal parties. However, there existed some confusion regarding how to deal with the issue, and how to link the struggle for socialism with the struggle for national equality.

In the 1929 report it appears clear that the struggle for national equality would flow naturally from the struggle for revolution and social transformation. The 1934 report is somewhat ambiguous; it does recognize that French-Canadians form a nation, but it does not recognize the problems that are specific to them as a nation. Until the end of World War II, the Communists perceived national equality primarily as a social and economic problem. However, from a Leninist perspective, the right to national self- determination means control by the oppressed nation (in this case, the French-Canadian nation) of its own state, and of being able to freely choose whether such a state exists separate from the dominant nation or within a new partnership.

We shall understand here that until the late 1940s, what can be designated as Quebec’s national movement was dominated by reactionary and clerical ideas, such as those found in the writings of Abbé Groulx, Henri Bourassa or André Laurendeau, but also found in Duplessis’s cassock nationalism. It is only by the end of the 1940s, particularly with the 1949 Asbestos strike, that an important part of the people’s movement and labour movement starts to break with Duplessis. Among these, the Canada’s Catholic Workers’ Association (the present-day CSN, Confederation of National Trade Unions) took the path of secularization, bringing many Québecois workers into working class struggles. It would also be important to mention the student movement, which organized, in 1958, a general strike that 120,000 students participated in. Therefore, starting with the 1950s, all these actors gave a mass and progressive character to Quebec’s national movement.

Faced with this development, the Communist Party of Canada at its 17th Congress in 1962 declared its support of “the demand for a new Canadian constitution; for the negotiating, on a completely equal footing, of a new confederal pact between French and English Canada, safeguarding the equality of rights and the interests of each, and containing explicit guarantees of the right of national self-determination for French Canada.” In other words, the issue of national inequality was now seen as a crucial democratic concern and not just a side-effect of capitalist exploitation.

The 1960s were marked by numerous strikes and workers’, farmers’, and students’ struggles. The soil was now fertile enough to permit a spate of new parties that claimed to link the struggle for national emancipation with the struggle for socialism. It was in this context that the Quebec Communists, with the support of the CPC’s Central Committee, formed the Communist Party of Quebec as a separate entity in 1965. The goal of this important change was, on the one hand, to better reflect the multinational character of Canada within the Party and, on the other, to guarantee Quebec Communists the latitude necessary to gain the confidence of Quebec workers, like other progressive groups.

This was a successful tactic, as it allowed the PCQ by the end of the 1960s to participate in creating a “federated mass party of labour” (according to the time-honoured words of Sam Walsh, at that time President of the PCQ) with the aim of uniting various left-wing groups, labour groups, and popular movements, whose main goal was to fight for necessary social and democratic reforms, including the recognition of Quebec as a nation, and the proposal of a new partnership with English-speaking Canada. The most important factor of this federated party was to place social and popular struggles at the forefront, rather than independence.

Despite fruitful discussion, 1968’s creation of the Mouvement Souveraineté-Association (a predecessor to the Parti Québecois), by René Lévesque and other dissidents from the Liberal Party, considerably slowed down this project. In fact, during the 1960s, the national movement began to be co-opted by the petty-bourgeoisie, who advocated secession as a priority. Thus, an important ideological struggle emerged between those who advocated the unity of the left beyond the national question (including the PCQ), and those who promoted independence. Through the MSA and the PQ, the latter group found a political vehicle through which to abandon the project of a federated mass party in favour of one which appeared to be social-democratic, but was above all pro-independence.

Indeed, even if the Parti Québecois did attempt to join the Socialist International, it was never a social democratic party. At no time did René Lévesque claim it was. While certain aspects of the PQ program prove confusing, they have everything to do with acquiring the support of the working masses for independence, a project essentially devoted to the interests of Quebec’s petty- bourgeoisie. To convince the working class, following the victory of the PQ in 1976, a number of measures were passed (“anti-scab” laws, universal auto insurance, the Quebec Charter of Rights and Freedoms, etc.). But, once the referendum was over, policies changed dramatically under the second Lévesque government, including the imposition of Bill 105, which forced a 20% pay cut and an increased workload on government employees. It was also during this time that one of Lévesque’s former ministers laid the groundwork for the state, employers, and unions to finance Quebec businesses.

That the adoption of these anti-social policies coincided with the party’s new orientation (the beau risque bet on independence) is not accidental; rather, it is a testimony to the true petty- bourgeois character of the Parti Québecois and of the Quebec independence project. Indeed, by implementing such policies, the Parti Québecois revealed its commitment to capitalism, a commitment it previously had to hide before the 1980 referendum so as to gain the confidence of the working masses and secure a “yes” vote. These policies reveal the true nature of the independence project, namely the creation of a new state through which the Quebec national petty-bourgeoisie could establish itself as a class monopolizing state power.

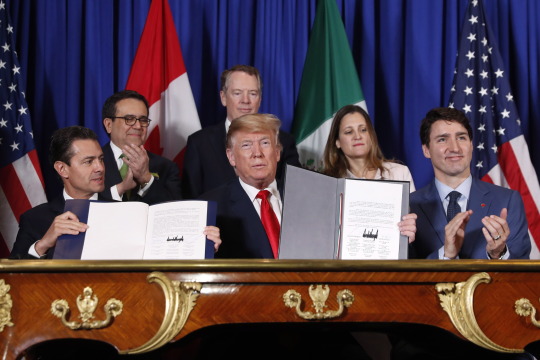

This aspect is present from the very beginning of the independence project (or the project for “sovereignty association”, to put it in Lévesque’s modest terms). In proposing a “sovereignty association”, it is interesting to note that Lévesque compared his project to some international examples, and he seemed to entertain the possibility of a North American equivalent of the European Economic Community (the predecessor to the European Union), which would have the consequence of pitting workers against one another. It is therefore clear that the independence project has always been intended to serve capitalist interests, particularly through the greater integration of Quebec into the US market — an integration which would undoubtedly have the same effect in the rest of Canada.

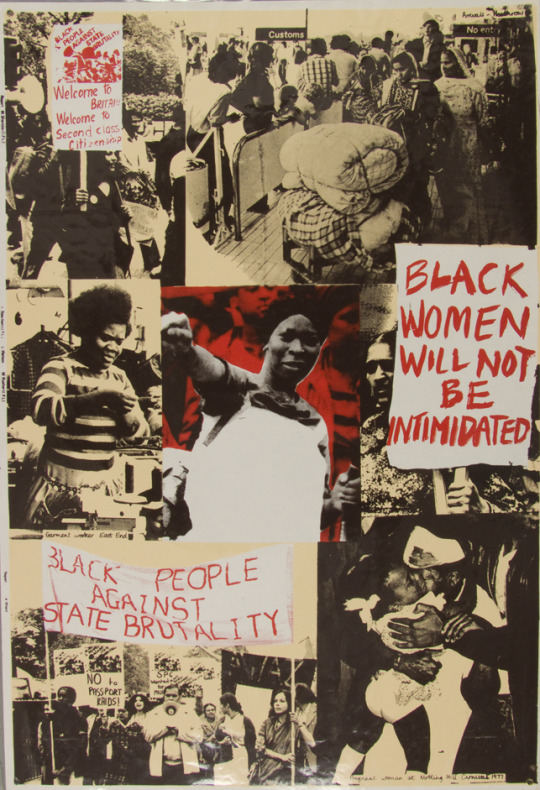

This is corroborated by the position taken by the Quebec separatists at the end of the 1980s, who supported the Free Trade Agreement between Canada and the United States (which would later become NAFTA). During the referendum campaign of 1995, the “yes” camp published a manifesto in which it clearly stated that Quebec’s existence within Canada hampered its ability to join NAFTA.

On this note, it is interesting to observe similar arguments currently being used in Europe. For example, one of the key arguments of the Scottish National Party is that its campaign for Scottish independence revolves around greater integration into the European Union. There is no doubt that this argument is gaining strength in the post-Brexit period. Similarly , the Catalan independence movement uses the same pro-EU rhetoric, as do several autonomist movements which advocate the weakening of the EU’s states in favour of strengthening its supranational character.

Faced with this apparent contradiction (integration with imperialism by way of national liberation), one must remember that the national question, like any democratic question, can be perceived in two ways: from the point of view of the working class, or from the point of view of the bourgeoisie. From the point of view of the latter, it is obvious that national interests are invoked because it is inappropriate for the ruling class to speak of its own interests as the exploiting class. However, as “unifying” as this nationalist discourse may appear, the fact remains that each nation – even an oppressed nation – is separated into two classes: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. One must never forget that national liberation is inevitably a bourgeois project. History has shown how most national liberation struggles (Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Iran, etc.), in which the Communists had no choice but to support the various united liberation fronts, ended up turning against them and the working class, if they were not able to win the fight against the nationalists after independence.

The question that arises is therefore whether the alliance between the proletariat and the national bourgeoisie is necessary to advance the struggle for socialism or whether, contrary to this, that alliance would slow down this struggle. In Canada, as in Spain and several other European countries, the Communists do not believe that the main contradiction is between the oppressed nations and the dominant nations, but rather between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. In Canada, we reject nationalist speeches which perceive the main contradiction to be between the Indigenous peoples and the descendants of European settlers, or between Quebec and the rest of Canada. Adopting such a position, in addition to forcing an alliance of the workers with the national bourgeoisie, would imply that an intermediate stage of national liberation would be necessary before embarking on the struggle towards socialism. However, this intermediate step, in our current circumstances, would only strengthen the bourgeoisie of this or that nation and would present the danger of balkanizing Canada into a series of more vulnerable nations, which would therefore be more dependent on the US imperialists.

If we believe, however, that no national liberation struggle takes precedence over the class struggle in Canada, we recognize the persistence of closely-related aspects of these struggles, and it is necessary to devise a truly democratic solution to the national question. We are not nihilists, and we reaffirm that the unity of the working class of every nation which inhabits Canada is only possible if we fight relentlessly, first against the chauvinism of the oppressing nation, then, parallel to this, against the narrow nationalism of small nations. This assertion does not mean that national equality should be achieved first as a precondition for the struggle for socialism, but rather that these two struggles complement each other. One should also note that in this sense, the existence of the Communist Party of Quebec as a separate national entity within the CPC since 1965, as well as the publication of an autonomous Quebec Communist press, plays an important role which makes it possible to mobilize people around the national question according to different strategies in the oppressed nation as compared with strategies in the dominant nation.

Whatever criticisms we may make of the national movement (even when considering the danger that the movement may be co-opted by imperialism), nothing justifies deviation from our fundamental principle, namely the guarantee of the inalienable right to self-determination of all nations, up to and including secession. As with a marriage, for the union to be free, consenting, and egalitarian, both spouses must be able to freely exercise their right to divorce. This does not mean, however, that we are in favour of divorce, but that without the clear guarantee of this right, the union between different peoples can only be unequal and forced. Indeed, without being guaranteed the right to separation, the nation remains oppressed, as it is deprived of the political leverage which allows it to guarantee its collective rights. If a union of nations is no longer considered an option, the nation has the right to leave the union unilaterally.

With these two principles (unity of the working class, and national equality), the Communists have over the past 100 years fought tirelessly for a new Canadian constitution which would guarantee the right to self-determination up to and including secession for all of the nations that make up Canada, on the basis of a new and voluntary partnership. The Quebec Communists have even committed themselves to a Quebec constitution, which would serve as the basis of what could become a Quebec republic within this union of nations.

During 1970’s October Crisis, which saw the Canadian army occupy Quebec, the imposition of the War Measures Act for the first time during peacetime, when 3,000 people were victims of police raids and 500 were arrested (mostly progressives who had nothing to do with the dozen FLQ members), the Communist Party of Canada was the only federal party which denounced this repression. While the other federal parties blamed the handful of petty-bourgeois adventurists, the Communists recognized that the root of the problem was the refusal to recognize Quebec as a nation and the refusal to guarantee its self- determination.

In 1972, the Communists were the only ones to actively mobilize within the Canadian Labour Congress to guarantee the autonomy of the FTQ (Quebec Federation of Labour), a battle which we won and which affirmed that Quebec’s working class could rely on the Communists to defend their national rights. Within other popular and democratic movements, particularly the student movement, the Young Communist League of Canada has always concerned itself with reminding student unions in English-speaking Canada of the need for an equal dialogue with Quebec student unions. In the peace movement, the Communists succeeded in ensuring that the Quebec Peace Council has its own seat within the World Peace Council, and this is true too within the women’s movement and the Cuban solidarity movement.

After a long campaign to alter the referendum question in 1980, and after it became clear that the question would not be changed, the Communists analyzed the situation and, considering the stakes as well as the positions adopted by the trade union movement, while also understanding that the “no” vote corresponded to the position of the monopolies, the Communists resigned themselves to calling for a critical “yes” vote. At the same time, in English-speaking Canada, the Communists campaigned to promote Quebec's right to sovereignty.

In 1995, following the attempted liquidation of the Party in the early 1990s, the Communist Party became disorganized in Quebec. However, this weakness did not prevent the Party from reaffirming its position to guarantee the right to national sovereignty. As the Liberals squandered public funds to allow Canadians from across the country to assemble in Montreal for a pro-Canada and pro-status-quo rally, a rally in which some left forces demonstrated their support, the Party issued an appeal to workers from both nations and stressed the importance of a new constitution for Canada.

Today, our party is the only pan-Canadian party to unequivocally denounce the Clarity Act, whereas the NDP and the Green Party refused to support a Bloc Québecois motion to repeal it. This position is far from trivial: through their actions, these two parties are making a clear anti- democratic statement. Not only do they refuse to support Quebec’s right to self-determination, but they put the final nail in the coffin by arguing that 50% plus one is not enough for Quebec’s secession to be valid... yet 50% minus one would be enough to keep Quebec within Canada...?

We should also note that the Communist Party has recognized the existence of Quebec as a nation since the 1930s. It was not until 2006 that the Conservative Party recognized this (no doubt as a political calculation by which to rally its strength against the Bloc Québecois in Quebec and navigate the sponsorship scandal). The NDP thus felt obliged to do the same and, in advocating an “asymmetric federation”, adopted the Sherbrooke Declaration — yet it does not recognize the right to self-determination, nor does it promise a new constitution.

In 1998, the reorganized Communist Party of Quebec wagered that the organization of a federated party of the working masses, as promoted earlier in the 1970s, was relevant during a period in which a growing number of trade unionists and progressives felt alienated by the neoliberal turn of the Parti Québecois under Lucien Bouchard. Thus, Communists, social democrats from the Parti pour la démocratie sociale (PDS), and trade unionists from the Rassemblement pour une alternative progressiste (RAP) founded the Union des forces progressistes (UFP) – which originally sought to constitute a union of progressive forces, beyond their individual positions on the national question. But, even though all member groups agreed that the issue of independence would not be at the centre of their agenda, the UFP was forced to rule on the issue very early on. Again, it was the Communist proposal that won the confidence of the congress. It was through this proposal that the UFP recognized the existence of two positions on the national question, one pro-independence (the majority position) and the other (the minority position) which promoted the unity of the working class. These two positions came together in the recognition that independence would not be the end in itself, but rather a means of providing Quebec with extensive social programs.

Victim of its own success, the UFP aroused the envy of several groups and individuals, each with varying degrees of militancy and left roots. In 2005, the UFP merged with the Option citoyenne movement, maintaining certain of the characteristics of a coalition, in particular assuring its original member organizations seats on its governing body, but it became become a unitary party known as Québec solidaire. Gradually , QS abandoned grassroots political activism in favour of bourgeois electoral politics. Its Coordination Committees no longer act as a catalyst for struggle, but as an electoral machine. Consequently, QS has moved away from popular, democratic, and labour struggles in order to be seen as a “reasonable” party, capable of assuming power and managing capitalism successfully in Quebec.

One of the last elements that distinguished it as a militant party was its position on the national question, inherited from the UFP . Even though QS asserted itself as an independence party, it refused independence through referendum and fought for a constituent assembly which would have the task of drafting a Quebec constitution. This constitution, according to the original program, did not necessarily seek to lead to independence, which allowed us Communists leeway to promote our idea of an equal and voluntary partnership. Thanks to this position, QS showed that it was possible to fight against the status quo without at the same time promoting independence as a solution to the national question. This stance contrasted with the vision of the federalists and nationalists, for whom combining the right of separation and unity of the working class beyond the nation is anathema.

For many leading members of the QS, this audacious proposal, too anchored in struggle, had to go. They tried three times: the first two times were without success, particularly thanks to the mobilization of the Communists. However, the third time around, they sidestepped the problem and used the pretext of a merger with a small nationalist group, Option nationale, to force members to accept their position on the national question.Today, QS still claims to fight for a constitution-drafting assembly, but its outcome will have to be independence. In other words, rather than a constituent assembly, it is a constituent referendum: “Independence, and a constitution to fix the details!” Following this change, we had no choice but to leave Québec solidaire, and our comrades who were still active there resigned.

This saga, in which the Quebec Communists were engaged for over 10 years, shows that our position on the national question, just like our strategy of a federated party for the working masses, has proved its worth, but that the main way that we can optimize carrying out this strategy is through the strengthening of the Communist Party .

We Communists do not claim to have a complete answer to the national question. In fact, several questions remain unanswered, including the form that this equal and voluntary partnership should take. For Quebec, we demand the existence of a sovereign nation, which would benefit from its own constitution, but be associated within the framework of an equal and voluntary partnership. However, for other nations, depending on what they choose freely, the exercising of their right to self-determination may be different, and may take the form of greater autonomy. From this arises several questions, not least of which is: should the dominant nation have its own state, or it will merge with the newly created central state? What about Indigenous peoples? Let us dare to ask the question: which ones constitute a nation, and which ones do not?

All of these questions are now circulating, and are subject to discussion as part of a democratic process. What is important for now is the guarantee for each of Canada’s nations to its inalienable collective right to self-determination up to and including secession.

Beyond this fundamental principle, we have a series of more concrete proposals to structure the debate, offering workers of all nations in Canada a say in what this new constitutional pact would look like and how we propose, concretely, to guarantee the right to self-determination for all nations that inhabit Canada.

As we have pointed out, the current Canadian Senate is unquestionably the institution that best personifies national oppression within Canada. Thus, our proposal is its abolition — pure and simple — and its replacement by a Chamber of Nationalities, on which will sit an equal number of elected representatives of each nation that makes up Canada. Thus, to the proportional and democratic representation of the equivalent of the House of Commons will be added the equal representation of each nation. Any bill will have to be endorsed by both chambers before it becomes law, and, when a bill concerns a particular nation, that bill will have to have the support of its representatives in the Chamber of Nationalities.

This proposal is the only truly democratic solution to the national question in Canada. It is the only one which makes the unity of the working class its fundamental principle while continuing to guarantee the inalienable right to self-determination of each of the Canadian nations. This is the only proposal that is truly unacceptable to the big corporations, because it concerns the right of nations to self-determination, including the vetoing of laws that would affect them negatively. It is also the only proposal which attacks the narrow, exclusive and selfish nationalism currently present in the oppressed nation, while pulling the rug out from under the national bourgeoisie, which uses the national question to advance its class interests. It is only through this proposal that the different national movements can come together in their common fight against state monopoly capitalism, the main enemy of the working masses of Canada and the basis of Canadian imperialism. It is also through this proposal that, by guaranteeing full equality as among nations, will enable the working class to unite and fight for the democratic sovereignty of Canada against the United States

This is what makes ours the only truly revolutionary proposal.

0 notes

Text

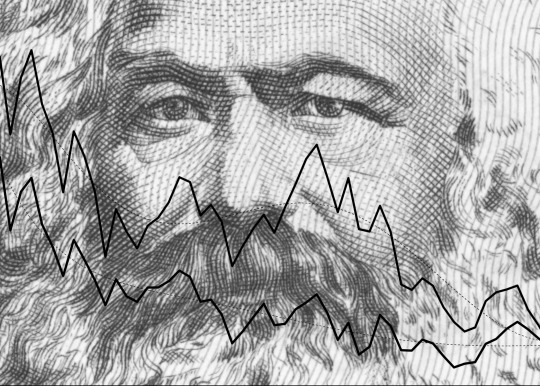

THE FALLING RATE OF PROFIT EXPLAINED – WITH NO MATH!

And Why the Green New Deal Can't Save Capitalism

Saleh Waziruddin is a long-time Niagara Peninsula activist and student of capitalism.

Why does Marx say that under capitalism the rate of profit has a tendency to fall? Why can't capitalists escape this tendency, or can they? Why can't they keep making profits at higher and higher rates? Could investing in “green jobs” and the “green economy” keep capitalism from crashing?

Marx said even if workers lived on air and worked 24-hour shifts, capitalists would still face a falling rate of profit.

It is important to make a distinction between (total) profits and rate of profit: the capitalists' total profit may keep increasing, but the rate of profit per amount invested as capital will decrease. This is important because capitalists are driven by getting a higher rate of return for their investment. It's all well and good to make $1 million profit, but it makes all the difference to the capitalist if they made that profit from a $1 investment or a $1 billion investment to begin with. There may still be a profit based on the cost of labour, materials, wear-and-tear on machinery, and other costs, but how much investment was needed to extract that profit?

Marx's Labour Theory of Value

The key to understanding the falling rate of profit according to Marx is to understand the difference between Marx's labour theory of value and the labour theories of value of those before him, namely Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Unlike previous economists Marx said the value of a commodity isn't embodied in it by labour for always and for ever, but the value of a commodity changes as society and technology change. The value is not the labour required to produce that particular item or service but the share of society's total labour required to reproduce that commodity (called socially necessary labour time).

To clarify, a commodity is something produced primarily for exchange as opposed to being used by the producer. It doesn't have to be a physical product; a commodity can also be a service if it is done for exchange. Under capitalism this exchange is done for a profit accumulated by the capitalist who hires the worker who produces the commodity. Those workers are said to be “productive” as in productive of capital; they produce the wealth the capitalist invests or accumulates. As Marx points out in Theories of Surplus Value (Addenda to Part 1) “A singer who sells her song for her own account is an unproductive labourer. But the same singer commissioned by an entrepreneur to sing in order to make money for him is a productive labourer; for she produces capital.” Her song would be a commodity if produced for sale even if it is not a physical object, e.g. at a live concert. (See Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Volume 34, page 136.)

It doesn't matter if some inept person took 10 hours to make something that could be made in one hour by one person with the current technology in our current society (the way it is organized for production). The value represented by that commodity would be the share of society's labour represented by one person-hour because that's how much labour would be required to make another one like it.

Note that although in the example above there is concrete (specific) work being done by one specific person, labour for Marx is social and abstract. The best analogy I have found is pyramid-building: no matter how much or for how long one person tugs at a pyramid's block, they won't be able to move it one inch. Working together a team of people can move it and build a pyramid. We can mathematically break this down into person-hours but the labour is the social result of a group of people working and not the contribution of any one person.

To scale-up to the level of a whole society, the wealth of the society has value because it is produced by the working class as a whole; every worker's activity contributes in some way to the value to society of a commodity. “Corporations are the pyramids of today” as someone once observed.

Anti-Marxist propaganda dating back to the early 1900's takes advantage of ignorance about Marx's labour theory of value to purport to show that management creates value too, not just labour! If a team of brick layers takes a certain amount of time to build a wall, but a manager can re-organize them to take less time to build the wall, then the value represented by the difference in time must have been created by the manager, or so argue these anti-Marxists. However, no matter how long it took a particular group of workers to build the wall, the value of the wall is from the generalized (abstract) share of all of society's labour the wall represents, as a generic wall and not just that particular wall.

If a group of wall builders were more inept or worked slower, or someone was able to get the wall built with less than society's average necessary labour required, it doesn't change the value the wall represents. It only means that either the wall will have to be billed at higher than its value (if they are less productive than average), or can be billed below its value (if they are more productive than average), or someone will have to pay the extra cost of being below average productivity, or someone can make an extra profit from being above average productivity. But the particular wall's value itself is from society's labour reflected in all walls, because another wall like it could be built for the socially necessary labour required for any wall in general.

Understanding specifically Marx's labour theory of value is key to understanding why the rate of profit falls. When capitalists compete with each other they can only go so far by cutting wages and getting labour for more hours, as there are only 24 hours in a day and you can't get (much) lower than free labour. The way they can get ahead of other capitalists is to invest in technology (e.g. machines) that will get more product out of a given amount of labour. This way their labour and material costs are spread across a higher volume of product and they can either undercut their competitors on price, or can make a higher return on their investment which will attract more investors than their competitors who need investments to continue.

At first, when a technology is new, this works out well for the capitalist who gets hold of the technology first. Eventually, the technology spreads throughout society and everyone is using it, getting more commodities from a given amount of labour than before.

Because the value of commodities reflects the share of society's labour which is required to reproduce that particular commodity, the value of commodities falls because under the new technology it takes less labour to make the particular good or service.

Why Pre-Marxist Labour Theories of Value Miss This Insight: Okishio's Theorem

If capitalists are going to end up with a lower rate of profit why would they invest in the first place? As you may have guessed, it is because they have no choice: whoever invests first gets an advantage and could destroy some of their competitors through undercutting them on price or attracting all the investment with initial higher rates of return. If a capitalist doesn't invest in the new technology and their competitor does they might find themselves in the ranks of the working class applying for a job with their erstwhile competitor.

But Marx's tendency of the rate of profit to fall was (apparently) shaken in 1961 by a Marxist, Nobuo Okishio, whose theorem used math to show capitalists would only invest if it reduced their costs and in some industries this would either increase or maintain the profit rate, and so their profit rate wouldn't fall. This convinced many Marxists to abandon the theory of the falling rate of profit altogether, saying it's unnecessary, or something Marx was wrong about even though it shows exactly us why capitalism is doomed no matter how the capitalists try to save it, even with a New Deal or a Green New Deal.

One of the reasons why Okishio came to his conclusion, and many Marxists have believed him, is because he did not understand Marx's theory of value, specifically that values would change once productivity increases relative to costs. Okishio said investment will occur if it decreases production costs, but not necessarily increase productivity.

At first Okishio's point will be true: the initial introduction of the new technology will decrease production costs for some capitalists and hold or increase their profit rate, and the same for other capitalists as they adopt the new technology. However, once the technology has become widespread it decreases the social labour required to produce a given mass of commodities, because even the costs of production which are reduced by the new technology represent less of society's labour, even if the labour involved in the direct production (not production of the raw materials or machines) of the commodity is the same.

But it's all of the working class's labour as a class which gives commodities their values, not only the labour of a particular group of workers. So while for at first some parts of the economy may be able to avoid a falling rate in profits, as Okishio says he has proved, eventually, despite the selected investments of those capitalists in cost-cutting technologies, the general rise in productivity in society leads to a general fall in the values of all commodities.

As capitalists invest more and more into technology and machines to get more value out of the labour of their workers, more and more of their total investment is going to other capitalists, who hire other workers to make the machines or technology. This other labour is “dead labour” when it gets to the capitalist using the technology, as it has already been used to produce the technology for a profit for another capitalist, while the “living labour” is used with the new technology to generate value which brings the profit to the capitalist investing in the technology. As capitalists are forced to invest more into technology to avoid being driven out of business by their competitors, more of their capital (investment) goes into “dead” labour than “living” labour,.

More of their profit has to be shared with other capitalists who are paid for the technology they bring, but they only make their profit from the “living” labour which is a smaller and smaller share of their capital. As their profit is coming only from the “living” labour which uses the technology, the values of their commodities must eventually fall as it takes less and less labour to produce, and so their profit rate also falls as they had to invest more into “dead” labour represented by the new technology than the “living” labour they employ to use the technology.

In this way also workers of a particular capitalist are not just working for that capitalist, but they are working for the capitalist class as a whole as more and more capitalists take a share of the profit from the value created by the labour of the workers. As value is from social and not individual labour, it is the workers as a class working for the capitalists as a class which produces the wealth then divided by the capitalists among themselves.

Does the rate of profit fall or not?

Marx wrote about various ways capitalists could fight against the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, but some Marxists have turned this into agnosticism saying the economy is too complex to know whether the rate of profit will fall or not, and that after all this law is only about a tendency (a law for a tendency). But Marxism does not, to borrow a phase from a TV character, tell us “oh, on the one hand this, and on the other hand that.” (Malcolm Tucker in The Thick of It, Season 2, Episode 1, BBC Four)

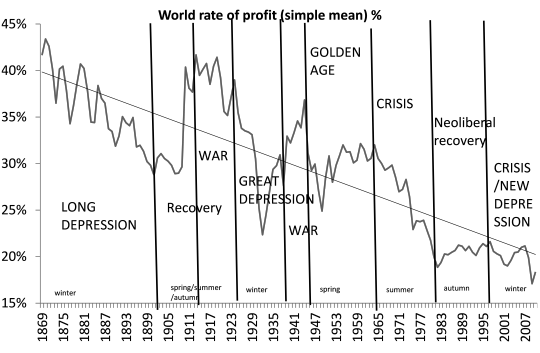

The value of a theory is in what it tells us about the interaction of, and how to determine the outcome of, the phenomena it describes, and Marx's labour theory of value tells us that no matter what the capitalists might do the rate of profit must eventually fall. This has been shown empirically, whether in the form of the rate of profit of corporations or of recurring economic crisis. See the following chart of the estimated rate of profit for the world from 1869 to 2010 from the blog of Michael Roberts based on “The historical transience of capital” by Esteban Ezequiel Maito published online here.

[Graph 1: estimated world rate of profit 1869-2010 based on a weighted average from 14 countries: Germany, the USA, the Netherlands, Japan, United Kingdom, Sweden, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, People's Republic of China, Republic of Korea, Spain, and Mexico. Graph is from Michael Robert's blog extracted from Figure 5 on page 13 (PDF) in Esteban Ezequiel Maito's paper.]

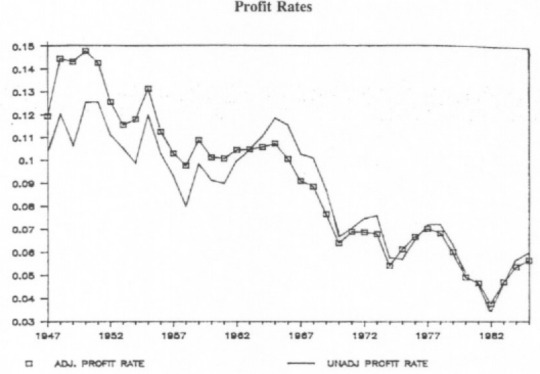

Also the following graph, Figure 3 in the original, from Anwar Shaikh's “The Falling Rate of Profit and the Economic Crisis in the US” on page 121 of The Imperiled Economy, Book I, (Robert Cherry et al, editors Union for Radical Political Economics, 1987) shows the overall decline in the profit rate for the USA:

[Graph 2: profit rates in the US with and without adjustment for capacity utilization. Graph is Figure 3 in Anwar Sheikh's article on page 121 of the book The Imperiled Economy, Book I.]

Unless of course the machines take over, in which case we would need to call The Terminator from the future. This, I admit, Marx may not have foreseen. This is an additional reason to overthrow capitalism before it reaches such a hypothetical stage, as if we needed more reasons.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THE RATE OF PROFIT STARTS FALLING?

When the rate of profit is increasing capitalists can expect to make a profit from investing their capital. Marx in Capital vol 3 described that when the rate of profit starts to fall, however, the smaller, more vulnerable capitalists can no longer sustain the return on their investment and, in order to avoid being destroyed by more secure competitors, start to engage in speculation and outright swindles. There is little need for them to take large risks if they can make a high return with only a moderate or lower risk, but it is only when they can't profit from what they had already been doing that they resort to increasingly desperate schemes.

The conventional understanding, even by radicals, has this phenomenon reversed: the source of the problem is misunderstood to be the financial swindling and speculation, and that the “productive” or “real” economy (which produces commodities, which may be goods or services) is fine. But actually Marx points out it is because the profit rate of the “real” economy can't be sustained that the swindling and speculation is resorted to. Otherwise why wouldn't these schemes be predominant all the time? Glib explanations such as “financialization” are offered but these are only superficial explanations that don't look at the deeper phenomena within production itself as Marx did.

Another conventional misunderstanding is that the “real” economy which produces commodities is only a small part of the economy compared to the “speculative” part of the economy. Actually those who engage in highly risky speculation or outright swindling are the smaller, more vulnerable capitalists compared to the larger capitalists who can weather the storm of crashing profit rates better. As Lenin pointed out in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism banking capital and “industrial” (manufacturing) capital are inter-connected and not separate.

It is the relatively smaller capitalists who get destroyed in crisis and there is an increasing consolidation of capital by fewer and fewer companies which can survive the drop in the rate of profit.

Attempts to reform capitalism so that it is crisis-free by focusing on the “real” side of the economy, or with massive public investment including into the environmental infrastructure and “green jobs” in a Green New Deal, as important as those are, cannot escape a financial crash from the falling rate of profit. This is because value and wealth are created socially but under capitalism are appropriated privately or individually, and so as values fall from increasing productivity profits will fall over time compared to when investments in technology were made in a race to not be driven out of business by competitors.

What happens when the rate of profit has fallen?

Capitalist rhetoric says government doesn't create jobs, business does. But when the profit rate has fallen business doesn't invest, because they can't get a return on their investment. In fact, as Marx described in Capital Volume 3, it becomes more important to hang on to cash to pay debts which can't be financed because the economy slows down as companies collapse.

This is why the then Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney accused companies of hoarding “dead” (i.e. uninvested) money (“Free up 'dead' money, Carney exhorts corporate Canada”, Kevin Carmichael, Richard Blackwell, and Greg Keenan, The Globe and Mail, August 22, 2012). Central banks lower interest rates to encourage investors to free up money from savings and invest them in stocks for a higher return than the interest rate. But when the rate of return on investment (profit rate) goes down to even zero, the Bank of Canada has to threaten that it is considering negative interest rates (in other words, charging interest on deposits!) as Governor Stephen Poloz said he would consider in 2015 (“Bank of Canada unveils new measures to deal with economic shocks”, David Parkinson and Barrie McKenna, The Globe and Mail, December 8, 2015). As of 2016 the central banks of the European Union, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark and Japan already had negative interest rate (“Will Canada join the negative interest club”, Jonathan Ratner, The Financial Post, March 14, 2016).

As a candidate for the Communist Party in federal and provincial elections, I could put this point across simply and be clearly understood by pointing out that “businesses don't invest when the economy is down,” and during the few years after the financial crash in 2008 there was little evident investment.

Capitalists want the working class to pay for the crisis, but it is at least as plausible (if not more plausible) to demand the capitalists to pay for it. This was demanded by a co-worker of mine at a call centre who, when told in a group meeting with other workers that the global economic crisis means our employer would be freezing our wages, responded by saying "we have been working for the employer for so long, producing all the profits they enjoy, that it is the employer who should make the sacrifice and absorb the cost of our raises."

How do the capitalists put the rate of profit back together again?

A fall in the rate of profit does not mean the end of capitalism. Once the values of commodities have fallen, those capitalists who survived the fall can invest at the lower values and make profits from investments made at the newer, lower values of commodities.

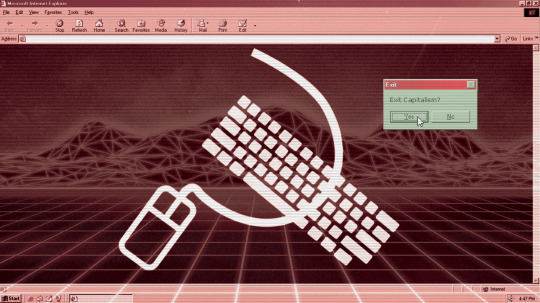

Capitalism has many falls in the rate of profit followed by investment picking up profitably at the newer level of technology. This doesn't mean capitalism can go on forever, but it does mean the fall in the rate of profit and economic crisis does not automatically mean the end of capitalism, it must be overthrown by the working class and its allies who use their political power to completely end the system of the private ownership of wealth and its production.

What happens if the rate of profit goes to zero?

There is a Marxist organization in the USA which has an unpublished theory that Marx's theories are superseded by the advent of robots. None of their publications cite this theory but their members hint at this belief. It is a pity they did not read Marx's Wage Labour and Capital where in the end he remarks “If the whole class of the wage-labourer were to be annihilated by machinery, how terrible that would be for capital, which, without wage-labour, ceases to be capital!” because the value of commodities would fall to zero, as would profits, requiring no socially necessary labour. (See Marx Engels Collected Works, Volume 9, page 226.)

If automation reached such a high level that all production operated in a kind of perpetual motion, where all maintenance and shut-downs/restarts were themselves done by robots (which may be possible as there are robots which can build or repair other robots, and even Marx noted in Wage Labour and Capital that since 1840 machines have been used to produce other machines), then no human labour would be required for production at all. As commodities can be reproduced without any labour they would have no value. As everyone would be out of work, hopefully enough of us would see the sense in just getting rid of the capitalists and taking over the production for the benefit of our class.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SUBSCRIBE

3 issues (including postage) = $20.00 CDN

$25.00 USD for international subscriptions

Individual copies = $7.00 CDN each

(2021 CPC Centenary Double Edition - $12 for both)

We accept interac transfers at [email protected] (be sure to include your address and email and make the password spark)

Make cheque or money order out to

NEW LABOUR PRESS

290A Danforth Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4K 1N6

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE CONTRADICTIONS OF CAPITALISM AND TECHNOCRATIC UTOPIAN FUTUROLOGY

A CRITIQUE OF FULLY AUTOMATED LUXURY COMMUNISM

Review by Roger Perkins

[Author Aaron Bastani, formerly known as Aaron Peters, one-time contributor to the UCL Conservative Society newspaper and researcher for the Blairite thinktank Demos]

There is no single contradiction or combination of contradictions that will make capitalism miraculously dissolve away into a communist nirvana. Capitalism in severe crisis does not collapse or fade away. Capitalism always fights back, searching for out-of-the-box configurations that give it new life. Therefore, capitalism must be consciously brought down and replaced with a new consciously-built socialist society. This imperative, the most important in human history, must begin, if not yesterday, then certainly today.

Contemporary capitalism is split by serious contradictions and seismic fault cleavages under increasing stress. The basic contradiction of capitalism is the contradiction between the social character of production and the private capitalist form of appropriation. In Anti-Dühring, Engels stated:

The contradiction between socialised production and capitalistic appropriation manifested itself as the antagonism of proletariat and bourgeoisie. (Karl Marx Frederick Engels Collected Works, Volume 25, page 256)

The resulting class struggle together with numerous economic crises and cycles have proven in the short and medium term to be features of a more or less “stable” capitalism and do not by themselves threaten the immediate collapse of capitalism.

However from time to time Marxists, non-Marxists, and even a few capitalists have sought out the fatal contradiction of capitalism. For example, it was postulated that the “Law of the Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall” would cause capitalism to grind to a halt. Investment would end if profit was no longer likely. But a tendency for the rate of profit to fall is not the same as an iron-clad law mandating the rate of profit to always fall. Counter tendencies, in theory and observed in practice, can bring about a rise. This was the view of Marx. Although Marx asserted that the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall was “the most important law of modern political economy” and “the most essential one for comprehending the most complex relationships ….” (Collected Works, Volume 29, page 133; Penguin Grundrisse, page 748) he nevertheless also stated that this law “operates only as a tendency. And it is only under certain circumstances and only after long periods that its effects become strikingly pronounced”. (Capital, Volume III, Collected Works, Volume 37, page 237; Penguin translation of Capital, Volume III, page 346) Only until capitalism is finally declared dead on a world-wide basis and the inevitable socialist forensic autopsy is performed will one be able to determine the extent a “falling rate of profit” played in its demise.

A more recent attempt to single out a possible fatal contradiction of capitalism occurred in conjunction with the so-called “greening of Marxism”. James O’Connor, founding editor of the eco-socialist journal Capitalism, Socialism, Nature, put forth the view that the “contradiction between the forces and relations of production” resulting in overproduction, crises, etc. is now in the process of being overshadowed by a Great Second Contradiction of Capitalism. Expandor-die capitalism is incapable of greening itself or reversing its expansion imperative to become a stable, steady-state capitalism. The dynamic logic of capitalism forces it to foul its own nest with run-away civilization imperiling climate change, environment destroying pollution and depletion of necessary resources. In addition to O’Connor’s “forces of production and relations of production” the conditions of production have now allegedly risen to prominence and will severely, even fatally, log-jam capitalism to a halt. Capitalist think-tanks are busy in search of ways to overcome this Great Second Contradiction of Capitalism while staying within the boundaries of a still recognizable capitalism and not straying over the border into obvious socialist solutions. So far they have not been anywhere near successful.

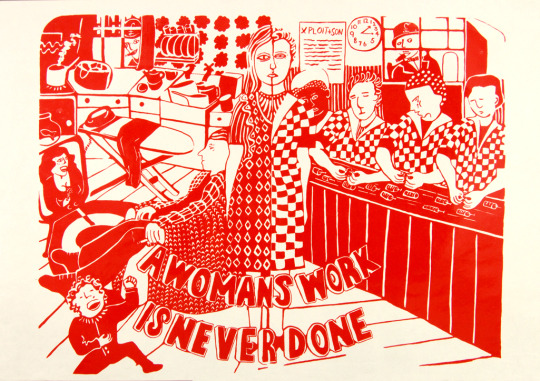

While O’Connor’s Great Second Contradiction of Capitalism is said to be located in production (conditions of production), the contradictions engendered by ever-increasing automation are observed in the sphere of consumption. At first automation was said to create as many new jobs as it displaced. But as the twentieth century progressed it became clear that the new jobs were mostly low-paid, precarious jobs for those who were able to obtain them and long-term, debilitating unemployment for those who did not. The working class, to an even greater extent than before, no longer had the purchasing power to buy what it produced – thus an under-consumption crisis.

This can be illustrated by the famous legendary encounter between Walter Reuther, head of the United Autoworkers of America (UAW) and a Ford Motor Company executive who had invited Reuther to tour the just-opened automated Ford plant in Cleveland. Reuther was confronted with acres of automated machines and robots. The usual assembly line of workers was nowhere to be seen. Instead a few thinly-dispersed technicians stood before a panel of green and yellow flashing lights making occasional adjustments to the production process. The Ford executive, with a gloating and gleeful grin turned to Reuther and confidently declared, “These robots, of course, receive no wages, zero pensions, never go on strike and they don’t pay any union dues to you!” Reuther immediately replied: “And neither do they buy any of your cars.”

The natural tendency of capitalism to cause a crisis of overproduction with the resulting temporary layoff of workers is said to have been morphed into the permanent massive disappearance of jobs accompanied by massive underconsuption.

In addition to the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, the destruction of the conditions of production and everincreasing automation there are many other contradictions of capitalism. For those who want to explore further, the following books may be of use:

Seventeen Contradictions of Capitalism, David Harvey, 2014

Breakdown of Capitalism: History of the Idea in Western Marxism 1883-1983, F. R. Hansen 1985, reprinted 2017

Capitalism’s Contradictions: Studies of Economic Thought Before and After Marx, Henryk Grossman, reprinted 2017

Contemporary Capitalism: New Developments and Contradictions, N. Inozemtsev, Progress Publishers: Moscow, 1974

The Scientific and Technological Revolution and the Contradictions of Capitalism, N. Inozemtsev, Progress Publishers: Moscow, 1982

With the arrival of the twenty-first century, Aaron Bastani, the author of Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto, believes a new third qualitative leap in human history is about to take place. The first qualitative leap was the invention of agriculture, which was vastly superior to hunting and gathering. The second was the Industrial Revolution, particularly the invention of the steam engine which accelerated capitalism and sped it down the tracks to eventual world dominance. And three, the epoch we are now entering, one of boundless abundance made possible by hyper-fast quantum computers exhibiting high levels of artificial intelligence (AI).

In Bastani’s mind automation itself will undergo a capitalism-ending giant qualitative leap which, while ironically solving most of the existing contradictions of capitalism, will nevertheless become the fatal contradiction of capitalism. This new artificial intelligence (AI) society will result in the vanishing of the working class because living labour power will no longer be hired. The working class has been digitized into computer zeros and ones. Variable capital has now become constant capital – or so Bastani claims.

The author states that all of our material needs will be produced very, very cheaply – almost for free – by gigantic computer-commanded 3-D printers. Bastani operates under the slogan “Information Wants to be Free” and gives the example of music now being free (but perhaps illegal) on the internet after having been digitized. This AI/knowledge society will be incompatible with a capitalist market economy, thus negating capitalism as well. But, according to the logic of Bastani, capitalists without a market would find themselves disoriented and confused. Under the infinite weight of AI technology they would not resist their inevitable demise. Therefore there would be no need to consciously overthrow capitalism and replace it with socialism. Capitalism just becomes irrelevant and sublimates away like dry ice. Such a view has more in common with 1950s social democracy than Marxism – an extreme version of “peaceful transition”.

And all of this will happen, not in some indefinite distant future when lowerstage socialism has evolved into communism, but only a few short decades away from now– maybe as little as only two decades away (around the 2040s). If only these fantastic predictions of Bastani were true! Communism is only twenty years or so hence and no revolution or socialist transition period necessary!

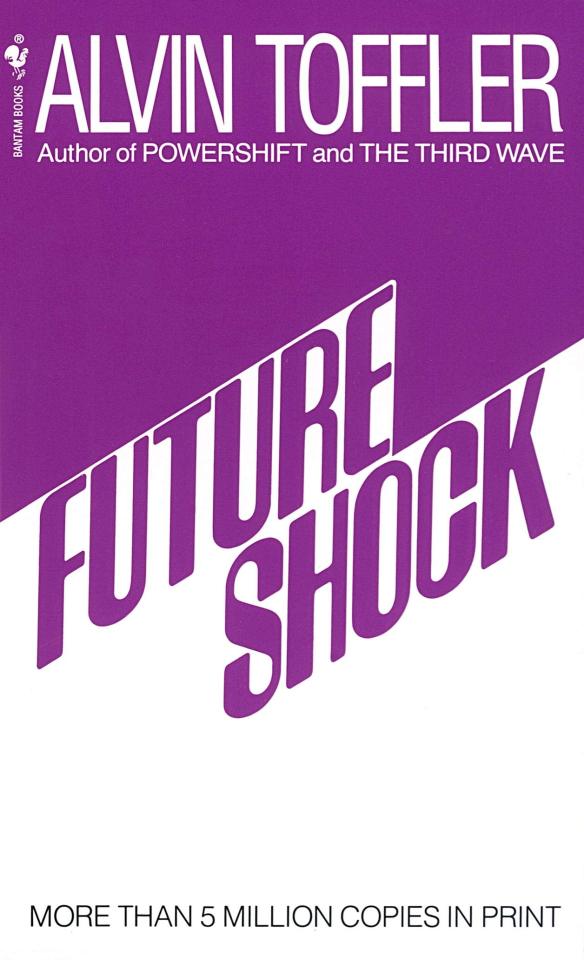

[Bourgeois futurologist pulp dates gracelessly in capitalist society: the above book chokes up the dollar bins of the English-speaking world]

Unfortunately, the author has combined some of the worst features of early utopian socialism with the speculative endeavors of modern bourgeois futurologists. Marx was hesitant to describe the future in more than a sketchy outline and certainly not in the fleshed-out and extensive details of the utopian socialists. Bastani on the other hand has no such hesitation. Meat would be grown in vats of nutrient fluid. There would be no need to cut down the oxygen-generating Amazon rain forest to create grazing land for methane-emitting cattle which would then get slaughtered for McDonald’s burgers. Declining scarce resources on Earth? Just get them from the moon or other planets – or, better yet, lasso a mineral-rich asteroid and tow it into a near-earth orbit. The author fails to mention any breakthrough regarding nuclear fusion on Earth, but why bother, we already have the sun. The new AI society will tap this free energy. No need to burn fossil fuels and Voila!, the climate change crisis solved.

The author provides technological solutions to most of the problems facing capitalism today, including health care (genetic modification and AI designed super drugs) and growing poverty (food, clothing and shelter – almost free due to AI mass production).

But the predictions of futurologists have often proven quite wrong. For instance, sixty years ago it was believed that by the year 2000 we would all be driving flying cars. It didn’t happen. This is most fortunate because automobiles raining down from the sky after an aerial freeway pile-up would be a very dangerous hazard indeed. A new category of statistical information would be necessary – death by falling vehicle.

Bastani doesn’t seriously consider that predictions are just that – predictions. He projects observed trends into the future as certainties, even having them manifest themselves almost within the same decade – a very unlikely occurrence. Even if one trend came true as predicted, he ignores the fact that a collectivity of many and different, interacting trends complicates accurate forecasting to an extreme degree. His thinking is mechanical, linear and not dialectical. He does not comprehend that all trends are subject to various contingencies, unintended consequences and even collateral damage to other trends, thereby altering the development path projected. Nevertheless Bastani plunges into the future with a fully elaborated utopian scheme – Fully Automated Luxury Communism (FALC). The author utilizes cherry-picked quotes from Marx throughout his book but is, in reality, much more a utopian technocratic futurologist than a clear-headed Marxist.

Who then is Aaron Bastani?

Bastani, UK-born and with a Ph.D. in political communication from the University of London, started his political journey with a family-inherited Tory outlook. He later opted for the Green Party, read Marx, continued his journey to the left and has now parked himself in the Labour Party recently led by Jeremy Corbyn. Along the way he co-founded Novara Media – a British left-leaning alternative media platform. However, Bastani’s media appearances are not confined to Novara and other fringe outlets. He is often invited as a guest on establishment media as well – BBC, Sky News, etc., where he sometimes dons a black T-shirt emblazoned with the message: “I am a Communist”. But is Bastani , his subjective beliefs notwithstanding, really a communist? Only by expanding the meaning of the word to its outermost fuzzy boundary, can Bastani be hesitantly identified as some sort of technocratic utopian “communist”. His views are not at all compatible with those of Marx, Lenin or historical materialists of today. The author’s political journey has definitely not arrived at the place called “Marxism”.

For Marxists, class is of the essence. For Bastani, class forces play little role. It is the forces of AI technology that have taken over. The working class (a prominent feature of Marxism) seems to have “died and gone to heaven”. It has been replaced by zeroes and ones and can no longer be exploited by capital because it has been absorbed into capital itself. As for the bourgeoisie, its class power has been sucked into the black hole of ever- increasing artificial intelligence. There is, however, a technocratic, vanguard-elite stratum of the population in his vision of society, but nowhere does the author state outright that it has become a new ruling class. What we are left with is some sort of amorphous multitude where class concepts are no longer applicable.

The political expression of this multitudinous blob of humanity Bastani calls “luxury populism”. Because Bastani believes the soon-to-arrive FALC is so overwhelming and inevitable, he doesn’t envision much political self-activity from the declassed and depoliticized masses. Although the author believes “the party form … makes increasingly little sense”(p.194), he flip-flops and advocates a FALC-led electoral party not too dissimilar from the Labour Party of 2019 – one of the very few instances where he recommends any sort of political action whatsoever. This party is necessary because the not-to-be trusted masses of Luxury Populism could go astray if not guided by the wisdom of committed FALC-ites. This party of “communist” technocracy would organize perfunctory “demonstration elections” because “people do not care about politics" and “it is only around elections” that the multitude is “open to new possibilities.”(p.195).The author is oblivious to other events that cause people to “care about politics” and become “open to new possibilities” – e.g. general strikes, wars, revolutionary situations, etc.

Apparently humankind’s path from capitalism to communism doesn’t include general strikes or revolutionary situations.

As for the possibility of war – imperialist nuclear war that could kill billions and set humanity back many thousands of years – Bastani obviously sees little danger because he fails to discuss this horrible possibility. If so, he is walking towards his “inevitable” utopian future with his eyes closed.

Though ignoring the working class in general the author does issue advice to present-day trade unions. To resist austerity is okay, but traditional trade union demands against capital should be shunted aside. Instead, unions should reorient themselves and attack the necessity of work itself. They should force corporations to introduce AI as soon as possible and as deeply as possible!

There is an anti-communist white thread running throughout the book. The only type of communism Bastani approves of is the “communism” of his own concoction –FALC. The author claims FALC differs from traditional communism in that it “recognizes the centrality of human rights, most importantly the right of personal happiness”(page 193). He gives no examples whatsoever to support this slanderous assertion. In answer to this anti-communist slop, let it be stated that communists are, of course, strongly in support of personal happiness and hold that it is achieved not in individual isolation but in the practice of a collective /individual dialectic. Human rights must be viewed not in the abstract in a form devoid of class content. They must be viewed concretely and the following question asked: “human rights” for whom and for what purpose? A capitalist whose bank has been nationalized would surely claim that the human right of ownership has been violated. That capitalist would also probably claim that the right to a job, healthcare and education are not human rights. And then there is “human rights imperialism”. Let us hope that Bastani has not fallen victim to such lying hypocrisy. But his “new communism” must, by any means necessary, be strongly marked off from the “old” communism.

Although Bastani does not extensively attack Lenin and the Russian Revolution, he does make his views known. He identifies with the Mensheviks who claimed that Russia was too technologically backward to even consider setting out on the path towards socialism/communism. The fact that he often quotes Marx but not Lenin is telling in itself (Marx good; Lenin bad). He describes the Bolshevik Revolution as an “anti-liberal coup” (p. 193). He condemns Leninism by falsely claiming that it “views production, and by extension working class subjectivity, as critical while ignoring a world whose ideas and technologies are hugely changed” (p. 196). But it is Bastani himself who views technological AI production as critical while failing to grasp that workingclass subjectivity (consciousness) is indeed one of the most important necessities in the defeat of capitalism.

Bastani instinctively knows that Communists would be highly critical of his smooth and speedy road to Fully Automated Luxury Communism – therefore Marxism Leninism must be run-over and left behind as road-kill.

The Scottish poet Robert Burns famously said that the best laid plans of mice and men go oft awry. No doubt reality itself will cause Bastani’s grandiose FALC to crash to earth. Will the author then concoct another and different utopian blueprint or will he become a disillusioned and cynical Labourite and maybe concentrate more on his business ventures? Or will he continue his political hopscotch and jump to the left and finally become a clear-headed Marxist (and Leninist)? It’s unlikely, but let us hope so. Or will he instead jump to the right and follow in the footsteps of former Labour Member of Parliament Sir Oswald Mosley, who had been considered a potential Labour Prime Minister? Mosley, however, defected from the Labour Party and founded the British Union of Fascists in 1932. Mosley’s mentor, Benito Mussolini, was also once a “socialist”. This reviewer will make no speculative predictions concerning the exact arrangement of Bastani’s future political kaleidoscope. It is his present political orientation as expressed in FALC that should cause concern.

The 1989 Hollywood hit movie Field of Dreams gave us the classic dialogue quote: “If you build it they will come.” In contrast Bastani’s 2019 science- fiction Field of Dreams tells us: Don’t build it and communism will come.

By relying on the almost infinite power of a qualitatively new artificial intelligence the author ignores the revolutionary practice of oppressed classes. No need to build any foundational construction that prepares for a revolutionary situation. Technological determinism has run amok. Just let the fatal contradiction of capitalism do its thing. The author leaves us with the impression that even if all anti-capitalists, revolutionaries and militant workers were to be placed in the deep sleep of suspended animation until after 2040 they would wake-up to Fully Automated Luxury Communism. Revolutionary cadres and a revolutionary organization not needed. This book is worse than seriously flawed; it is even dangerous, because it leaves us with the impression that passivity is a viable option.

Communists are not Luddite opponents of automation and AI. Many of the predictions of FALC will eventually become true although on a varied and much-altered time scale and under very different conditions than those envisioned by the author. But, however embodied or personified AI becomes, it cannot by itself function as avatar or proxy agent for qualitative change from one socioeconomic system (capitalism) to another (socialism/ communism). That role still belongs to a new and always changing working class. For Bastani the working class is not an agent of social change – only flotsam in the AI tsunami. For revolutionaries the working class, its party and allies must be recognized as the decisive core of the coming revolutionary process. The publishing of Bastani’s Fully Automated Luxury Communism will not get him rewarded with rapture to AI heaven. Instead, without decisive working-class action he will find himself engulfed in the flames of a capitalist hell-on-earth.

In conclusion: The declassed technological delusions and utopian visions of Aaron Bastani are dangerously wrong. The publisher, Verso Books, has given us a lemon, the lemonade of which is useful only to those who undertake grand “thought experiments” or seek truth via the maze of error.

Furthermore, speculations about the fatal contradiction of capitalism must be subordinated to the organization of a consciously socialist working class whose party is ready for and knowledgeable regarding what Lenin called a “revolutionary situation”. There is no single contradiction or combination of contradictions that will make capitalism miraculously dissolve away into a communist nirvana. Capitalism in severe crisis does not collapse or fade away. Capitalism always fights back, searching for out-of-the-box configurations that give it new life. Therefore, capitalism must be consciously brought down and replaced with a new consciously-built socialist society. This imperative, the most important in human history, must begin, if not yesterday, then certainly today.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BY LESLIE MORRIS

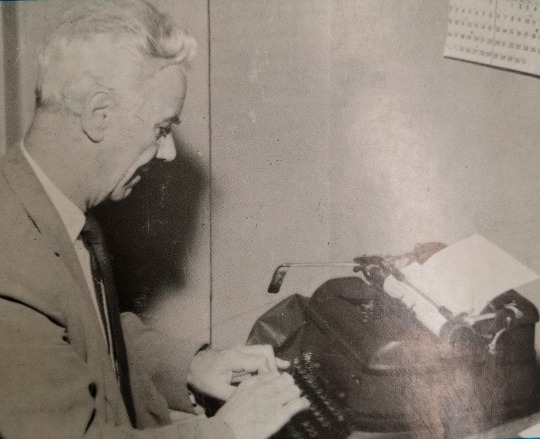

Leslie Morris at his typewriter. [Communist Party of Canada]

Welsh-Canadian Leslie Morris was a Communist Party activist in the nineteen-twenties, thirties, forties, fifties, and into the sixties. Elected Party Leader in 1962, he died in 1964. Through much of that time he wrote a regular column for the Communist press. Here are some examples.

***

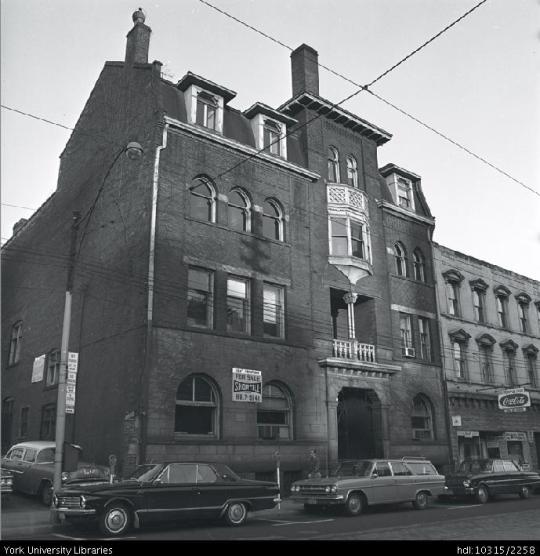

The Labour Temple at 167 Church Street, Toronto. (1965) [York University Archives]

***

(In 1921, while Canada was still under the War Measures Act, the Communist Party organized itself secretly in a barn near Guelph, Ontario. In 1922, the above-ground Workers Party of Canada was formed, and in 1924 it changed its name to Communist Party of Canada. Leslie Morris was there, and in 1938 reflected on the Party’s founding.)

December 24 | 1938

Party of the Builders of Canada

Daily Clarion