Text

If we can't spend more we can at least spend better

The case for Place Based Public Service Budgets

First published on LabourList 31st January

On Monday, Angela Rayner described the government’s announcement of £600m of new emergency local authority funding as a “cynical sticking plaster”. She’s right: the money is welcome but a drop in the ocean.

Almost every day another council faces bankruptcy or cuts services to the bare legal minimum, in just one part of the crisis engulfing England’s public services. Last autumn, the NHS was facing a £7bn shortfall, according to independent experts. Schoolchildren in deprived areas are falling behind. Our courts and prisons are clogged.

We must revive a radical New Labour policy

Labour’s leadership is clear that a government boxed in by record taxation, high national borrowing, and years of low growth will have no quick or easy financial fix.

A new report I have co-authored with Jess Studdert of New Local says that if we can’t spend more, we must spend better. It advocates reviving radical ideas for place-based public service budgets that were pioneered by the last Labour government.

The concept behind the ‘Total Place’ pilots launched in 2009 was simple. Find out how much money is spent on all public services in an area and work out how to spend it better. That might sound blindingly obvious, but it isn’t how public service funding worked then, and it isn’t how it works now.

Local spending is fragmented into siloes. Each silo is accountable to a different government department, each has different measures of success, and each is funded separately by the UK Treasury. Effective local coordination of spending is impossible.

This setup is deeply damaging to how our services work. The IFS recently found that the distribution of £245bn spent in England across the NHS, schools, local government, the police, and public health did not reflect local need.

Some services in some areas were relatively overfunded. Others were underfunded. The IFS concluded that “there may be benefits in providing greater flexibility to leaders to move spending between service areas”. Under the current system, that just isn’t possible.

Services lack funds or incentive to focus on prevention

Real people don’t live their lives in separate departments or services. They often know what would make a difference but instead of services shaped around their needs they find duplication and gaps. Studies have found families forced to interact with many overlapping agencies, while social workers get bogged down in administration.

An ex-offender is more likely to get into new trouble than receive joined-up support from prisons, probation, mental health, housing, and Job Centres. Almost every family has experienced the broken interface between the NHS and social care.

Too little is invested in early intervention : each service has an incentive to shift the costs of economic and social failure on to another. It is a Catch-22 which our report calls “the prevention penalty”: services have little motivation, or money, to fix problems which will later become another service’s crisis.

Some councils pioneer collaboration, despite the system

Total Place offers a way to break this vicious cycle. The proof is in those early pilots, which filled me with so much hope when I was Secretary of State.

The first-year pilots were taken up across England, by councils of all political stripes. They showed how to bring health and social care together, deal more effectively with substance abuse, create joined up children’s services, and improve access to many services. All offered better services for the same money.

The Coalition scrapped Total Place in 2010, opting for the deep and damaging austerity we have had since.

Occasional attempts have since been made to bring services together; some councils have pioneered new ways of working and enabled local people to shape services that meet their needs. These prove the principle works but they happen despite the system, not because of it.

Councils can’t save any more cash

There is no room for more savings in today’s local government. There is no scope for top-down ‘productivity’ drives which intensify the ‘doom loop’ of constant crisis fighting and prevent service improvements.

Labour sees the need for change. Shadow devolution minister Jim McMahon recently told the Institute for Government: “The question is how do you get more bang for your buck? There is something in looking at every pound you spend in an area and really requiring every part of Government to marshal around a single plan for a place.”

It will take radical reform and the creation of Place Based Public Service Budgets to realise that potential. All agencies would identify the total money spent in each locality and match this against the needs of local people and communities.

Coordinated by elected local authorities they would produce Local Public Service Plans that set out new ways of working – including ways of involving local people – and the improved outcomes to be achieved. Instead of working to top-down departmental targets, local partners would be held accountable for achieving the results they promise.

And instead of each service reporting to its parent department – a system that gives only the illusion of looking after public money – value for money would be bolstered by a new statutory local audit service and Local Public Accounts Committees. Together these would provide tougher scrutiny than exists at presents.

It will take political determination to push such changes through Whitehall’s entrenched and centralist culture. But for a party committed to improved public services, there are few other games in town.

The ‘Place Based Public Service Budgets – Making public money work better for communities‘ report by John Denham and Jessica Studdert, Deputy Director of New Local, and is published by NewLocal in association with the Future Governance Forum.

0 notes

Text

Labour's misleading assumptions about English identity

First published on LabourList 27.12.23.

An enduring myth about national identity in England – not least on the left – is that Britishness is inclusive while Englishness is culturally and ethnically exclusive.

The belief has shaped Labour thinking on community cohesion and multiculturalism. Coupled with the equally erroneous argument that talking about England must inevitably undermine the union, it has left Labour in England talking only about Britain and Britishness.

Labour prejudices are often based on a tiny, noisy minority

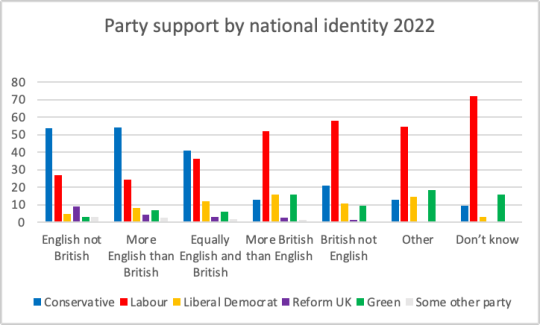

New polling from the Centre for English Identity and Politics (CEIP) challenges these Labour assumptions. The truth is that there is very little difference in the way England’s voters perceive the inclusiveness of their national identities.

Asked whether British identity can include people of all cultures and ethnicities, 74% agreed (44% strongly) and 9% disagreed (4% strongly). When the same question was asked about the inclusiveness of English identity, 69% agreed (41% strongly) and 11% disagreed (4% strongly). There is a difference, but it is small.

Amongst those who describe themselves as ‘English not British’, the rejection is higher at 24%, but this amounts to less than 4% of the population. No doubt this includes some of those who invaded the cenotaph on Armistice Day, but too often, Labour prejudices are shaped by this noisy but tiny minority, rather than by the views of England’s majority.

Previous polling by the CEIP with British Future also showed sharp falls in the number of people thinking of English as a white-only identity between 2012 and 2018, belying claims that Brexit in 2016 marked an upsurge in xenophobic Englishness.

A concerted attempt to promote inclusive Englishness is needed

A cohesive society rests on shared national identities and shared national stories. The great majority of people in England feel both English and British to some degree: for most, ‘belonging’ in England is to be both English and British.

The risks of dividing those identities from each other should be clear. If only Britishness is promoted as an inclusive identity (and by implication Labour reinforces the idea that Englishness is white and exclusive), the party is helping to construct two competing identities. On the one hand, there would be a British identity shared by members of ethnic minorities and a small group of largely graduate, liberal white people (admittedly, including a lot of Labour members). On the other, there would be the combination of British and English identity shared by the majority.

To an extent, this is where we are today not least because, in England, Britishness has been the focus of inclusive identity for 30 years. (In Scotland and Wales, the emphasis has been on creating inclusive national identities.)

Ethnic minorities are less likely to identify as English, but it is important not to ignore the organic change that is taking place. 45% see themselves as strongly English and a majority see Englishness as an identity that is open to them, and the new polling demonstrates that the door is open. The gap can be closed by a more concerted attempt to promote inclusive Englishness (and not relying so much on sport for visible and inspirational symbols of English belonging). Labour should take care not to be on the wrong side of history by standing in its way.

Denying voters’ Englishness weakens Labour’s connection with them

Apart from the central challenge of developing a shared sense of national identity in England, there are other reasons for talking about both English and British identity.

It is always good in politics to talk with voters in the way they talk about themselves. Most see themselves as British and English, not holding the identities as separate ideas but inextricably mixed. To deny their Englishness weakens Labour’s connection with them, and the more so for those who emphasise their Englishness.

In the same CEIP polling, 70% of English voters agreed that ‘England, Wales and Scotland each have distinct national interests’. The next UK Labour government will largely only determine domestic policy in England. Few of Wes Streeting’s responsibilities for health will stretch beyond the English border, and it is the childcare and education in England that Bridget Phillipson will be able to shape. The Tory government has run into trouble at the Covid inquiry for failing to understand the remits of different national administrations. We should not fall into the same trap.

Issues of identity will resurface if Labour comes to power

Nor should our support for the union prevent Labour from talking about England in England. The party already has a different approach to each nation.

Labour accepts the principle that the people of Northern Ireland should decide their future relationship with the UK and the Irish Republic. In Scotland, we have set out no legal route to Scottish self-determination, but Scottish Labour works hard to shift the focus from the constitution while still talking directly to Scotland. The Welsh Labour government, by contrast, has set up an independent commission on the future of the constitution.

And Britishness itself is not a unifying identity across the UK. Politics in the UK is both UK-wide and distinctly national, and the idea that Labour should not be able to mention England in England is clearly daft and out of step with our approaches to other national politics.

Labour still struggles to win as much support from voters who emphasise their Englishness. But so long as the cost of living, the NHS and Tory incompetence – issues that cut across all identities everywhere – are the top concerns, Labour’s lead looks strong.

Once in government, however, issues of identity will soon be back. Whether it is defending a cohesive society against right-wing populism or sorting out relationships across the UK, Labour will need to get its language and geography right.

0 notes

Text

Labour needs to refresh its multiculturalism

First published on LabourList, Monday 13th November

The former Home Secretary’s divisive rhetoric will rightly get much of the blame for drawing far right activists onto the streets on Saturday. But the emotions driven by terror attacks and the military response in Israel and Gaza were already high. Most people don’t want the government to take sides, but the polarisation of those who do was dividing our society and causing turmoil in our Party. It comes when Labour seems to have gone quiet on how to handle the differences that inevitably exist within a diverse society.

The last Labour government made mistakes, but we generally sustained a political commitment to multiculturalism and community cohesion. The influential multicultural thinker Tariq Modood has contrasted Labour’s legacy favourably with the rest of the EU. Today we seem less interested in that heritage.

It does not bode well that the new Foreign Secretary David Cameron declared the end of “state sponsored multiculturalism” in 2010. Since then, there has been no coherent government theory or practice of making a society of diverse ethnicities, faiths, values, and histories actually work.

The promotion of – in themselves unobjectionable – ‘fundamental British values’ masks a deeper assimilationist demand for minorities to adopt an unchallenged majority culture. There has never been a practical strategy to achieve this impossible goal. Instead, minority differences are used to fuel the politics of culture wars.

Some multicultural practice still exists today but much of the energy and resource has been diverted to the counterterrorist Prevent programme. In the corporate and public sectors, the focus has shifted towards equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in employment.

Current strategies tell us little about how to live together

Centred on achieving fairness across different groups, EDI contributes little to developing relationships between them. There is often a ‘lived multiculturalism’ in the more diverse communities that demonstrate the ‘conviviality’ described by Paul Gilroy, but, as current events and the recent disturbances in Leicester show, it is not as resilient as we might like to imagine.

It’s easy to mock Suella Braverman’s attack on multiculturalism when so many of the Cabinet seem to embody its success. But is the left clear what it is defending? While organisations like British Future have shown how events like Remembrance Day can unite rather than divide, Labour has said little about multiculturalism’s future. Keir Starmer’s recent Israel-Gaza speech was aimed at a UK audience. It recognised the threat of division but much more will be needed.

For many, ’multiculturalism’ seems to be a loose preference for living in a diverse society, a relaxed attitude towards immigration, and tolerance of difference, all resting on equal rights of citizenship under the law.

This ‘thin multiculturalism’ reflects liberal and individualistic world views and values. It makes it useless for the tough job of bringing together a truly diverse society, because it immediately excludes all those whose group identities are strong and values socially conservative.

“If only liberals can be multiculturalists, multiculturalism is reduced to imposing liberal values on others”

Few of us are truly just individual citizens under the law. Most have strong collective and communal identities, and these sometimes conflict with each other. If only liberals can be multiculturalists, multiculturalism is reduced to imposing liberal values on others. Real multiculturalism – ‘thick multiculturalism’ – means working to create a society and nation where we all feel we belong despite our differences.

Multiculturalism is a political challenge, but it is one of practice first, not policy or ideology. It requires us to talk with and more importantly listen to those whose views we don’t like and sharing and hearing other people’s stories.

That’s the only way we can find and build on the things we hold in common. The more we understand how we all came to be here the more easily we can identify the nation we want to build together. (And when we talk of nation, those who claim Britishness is inclusive and Englishness cannot be, risk excluding those who value Englishness as part of their identity and exclude others from feeling English).

Multiculturalism is a practice, and a demanding politics

Multicultural political practice doesn’t mean we have to change our political outlook, but it does demand we seek an empathetic understanding of the other point of view. Showing solidarity with Palestine should not make us blind to the fear some solidarity actions create amongst Jewish communities.

Solidarity with Israel cannot ignore the pain of those who feel Muslim lives are not given equal priority. If we are sure our version of history is ‘true’ we can at least listen to why others cling to a different version.

The challenges are only growing. By no means all migration gives rise to communal tensions, but our global diversity means that many foreign conflicts are no longer ‘over there’ but intimately connected with the families, communities, and politics of our fellow citizens. The ‘white majority’ is fractured, with its own minorities who feel excluded and disadvantaged. The number of potential fault lines is not getting any less.

Multiculturalism cannot be a synonym for soggy liberal preferences. It’s a politics that is demanding and uncomfortable. If we can’t change our own Labour practice, we can hardly lecture others.

Of course, some people will exclude themselves: those who insist that Britain must be white; those who claim their faith justifies the murder of non-believers; those who would impose their views by force. But the multicultural tent needs to be a big as possible.

Let’s not pretend there are not people with extremist views amongst Saturday’s solidarity and far right demonstrators or amongst Zionists. The government has set up commissions on ‘countering extremism’ but its search for selective and ever more complex and unenforceable proscriptions of language will not work. The only sure way of countering extremism is to grow the social solidarity that leads every part of society to exclude its own extremists.

0 notes

Text

'Dear Cabinet Secretary......'

First published on the Bennett Institute website 12.9.23.

General Elections are often followed by changes to the machinery of government, whether by an incumbent Prime Minister or a new administration. As part of the Review of the UK Constitution project which we have developed in partnership with the Institute for Government, former Cabinet Office civil servant Philip Rycroft and former Communities Secretary John Denham set out the guidance that either Rishi Sunak or Keir Starmer might give to the Cabinet Secretary ahead of the next general election, in order to ensure that the stated ambitions of both of the main parties in relation to English devolution and the effective delivery of English public policy are realised.

‘Cabinet Secretary

The governance of England

If successful at the next election, it is my intention to radically reform the governance of England. This note sets out the rationale for so doing and outlines a new approach that I will seek to put in place. I will look to you for early advice on how to swiftly implement these changes.

Rationale

Under current arrangements, the boundary between the governance of England and that of the UK is not clearly delineated. There is no departmental structure or system of ministerial accountability for the delivery of English domestic policy.

It is now clear that decades of centralised government of England by the UK state have failed to tackle deeply entrenched regional inequality in income, productivity and health. Despite some limited progress on devolution to combined authorities, more radical changes are needed to the state in England.

My government will wish to establish a coherent system of national governance of England to develop, implement and coordinate English domestic policy. There are five reasons for doing so:

Current policy can be criticised for being poorly coordinated and not being sufficiently joined up. For example, responsibility for challenges like the effective reduction of re-offending or tackling obesity falls across numerous departments, some of which are England only, some England and Wales and some UK-wide. Ad hoc attempts to coordinate policy are ineffective.

The budgets of UK departments are settled in bilateral negotiations with HM Treasury. The process precludes cross-departmental coordination of priorities and policy and does not create a national budget for English domestic policy.

The fragmentation that results, and lack of clarity over the lines of financial accountability running to departmental Permanent Secretaries obstruct the coherent use of public money across different departments and inhibit the government’s ability to tackle complex issues. As a result, England’s current governance fails to make the best use of increasingly limited resources.

Current structures work against effective devolution to English localities, including the flexible local pooling of public spending which is essential to reduce waste and inefficiency. The commitment to devolution varies considerably, and without good reason, from department to department. In practice, Treasury priorities and concerns limit the degree of devolution. A coherent system of central governance is key to the establishment of a genuinely devolved system of English governance which both main political parties have committed themselves to establishing.

By delineating the distinction between England and UK issues, greater clarity on the scope and boundaries of English governance would help ensure that the relationship between English policy, the policy of the devolved nations and UK policy is much more clear and transparent.

New approach

The main features of the new approach will be as follows:

The rebranding of departments responsible for policy that are in effect entirely English-focused departments, viz Education; Health and Social Care; Levelling Up, Housing and Local Communities. (Residual functions with UK-wide implications such as international policy may still be managed from within these departments but in close collaboration with the devolved governments).

Identification of England-only responsibilities in other relevant departments (Department for Culture, Media and Sport; Home Office; Justice; Business and Trade; Science, Innovation and Technology; Transport; Work and Pensions; Energy Security and Net Zero; Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) and reorganisation to ensure that these are exercised separately from UK (or Welsh) responsibilities.

The creation of an England Office to coordinate English domestic policy. We intend to appoint a Secretary of State for England who will lead this office.

The Secretary of State for England will also sit alongside the other territorial offices in a Department for the Union, led by the Deputy Prime Minister.

The Secretary of State for England and the England Office will, inter-alia, provide representation for English interests in inter-governmental forums at a political and official level.

The establishment of an English Cabinet Committee, serviced by the England Office, and chaired by the Secretary of State for England, to affect the coordination of English domestic policy, with sub-committees formed as necessary to advance specific policy goals and initiatives.

Reform of the relationship between HM Treasury and government departments to ensure that there is a national budget for England and that the allocation of resources reflects priorities agreed across English departments.

The focus of accountability for local spending should be at a local level, rather than to central government, but will be bolstered by a new independent statutory audit authority with powers of intervention.

Devolution

These changes will take place in the context of my wider ambitions for the devolution of power to the regions and localities of England. This in itself will drive an important shift in the relationship between Whitehall and regional/local government in England. Those departments responsible for policy that will be substantially devolved can expect to see many of their functions reduced in scale as power and resources are transferred to combined authorities. This creates an opportunity for a commensurate transfer of skills and capabilities from Whitehall to the regions of England. This should be built into your planning.

Parliament

The organisation of select committees is a matter for the Parliamentary authorities, although I anticipate, and will certainly advocate, a committee structure that mirrors the changes we intend to make in the Executive.

Civil Service skills

I recognise that territorial management is somewhat alien to the Whitehall mindset. This needs to change, and quickly. To help oversee this programme, you should prioritise a programme of exchange with local government to rapidly upskill Whitehall in the understanding of how to effectively support the running of policy at a regional and local level.

Timing

I will look to you to drive a programme of change that will deliver these aspirations within six months of the next election’.

John Denham and Philip Rycroft

0 notes

Text

National Identities and Political Englishness

Abstract of a paper published by John Denham and Lawrence McKay (both University of Southampton) in Political Quarterly 22.9.23. The full paper is currrently available open access here

Over two decades, voters who emphasised their English identity played an influential role in the rise of UKIP and the Brexit Party, the Brexit referendum and the election of Conservative governments—a trend overlooked in most electoral analyses. Using twenty years of data from the British Election Study and British Social Attitudes Survey, as well as recent original surveys, the article explores the evolving political behaviour of national identity groups. It finds that ‘more English’ and ‘more British’ identifiers increasingly voted for different parties. The analysis also identifies growing differences in the demographics, social values and immigration attitudes of these groups, which descriptive and regression analysis suggests may underpin these divergent political behaviours. However, a fuller understanding of electoral behaviour must take account of ideas of national democracy and sovereignty. The electoral impact of both the characteristics of English identifying voters and ideas associated with English identity constitute ‘political Englishness’.

0 notes

Text

England needs a government

Across a summer of international cricket, rugby and football, and across both men’s and women’s games, there has been one constant. England’s national anthem has been “God Save the King”: the one that also does duty for the whole of the United Kingdom. In this instance, England’s inability to tell the difference between nation and union largely serves to irritate the Scots, Welsh, and Northern Irish. But when it comes to England’s governance, it is England that loses out.

Most people in England never stop to consider that we have no government of our own. Search Whitehall and it is impossible to find any civil service structure or ministerial committee that coordinates England’s domestic policy. (That covers all those issues like childcare, education; health and social care; housing; levelling up; and most of transport, agriculture and environment; issues that have been devolved to other nations for decades). There is no national budget for England, nor any debate about how the totality might best be spent. Instead, England is governed by a mishmash of uncoordinated UK departments, some with responsibilities UK-wide, some England and Wales and some for England only. Each is funded separately by the UK Treasury.

The costs of this fragmented, incoherent structure are high. Complex problems that run across departmental boundaries, like criminal justice, obesity or children’s wellbeing are not met by coherent, joined-up policy. Departmental silos mean ringfenced budgets can never be varied to meet challenges as they arise at local level. Accountability to Whitehall departments, supposedly designed to safeguard public money, merely ensures duplication and gaps in provision at local level. There is a cross-party consensus on the need for more devolution within England, but without a coherent centre to devolve power from it will never happen on the scale that is needed. The confusion between English and UK governance continually exacerbates tensions across the Union.

Gordon Brown’s report for the Labour Party on the future of the UK identified the confusion between UK and English government as doing “a disservice both to the devolved nations and to England itself”. Sorting out England’s governance should be high on Keir Starmer’s priority list. Neither his “five missions for a better Britain”, nor his commitment to devolution nor the imperative to make the best use of scarce national resources can be achieved with England’s current governance. Should Rishi Sunak pull off the political recovery he insists is possible, his government too must reform England if the varied aspirations of a new blue/red wall coalition are to be met.

This is the time for both parties to be preparing Whitehall for the change ahead. In a blog for the Bennett Review of the UK Constitution, we have drafted the memo that needs to be sent by a future prime minister to the Cabinet Secretary the senior civil servant responsible for the machinery of government. A new England Office, headed by a Secretary of State for England, would coordinate English domestic policy. Major departments focussed on England would be rebranded, and the English responsibilities of other departments clearly delineated. The England Office would provide civil service support and advice to an English Cabinet Committee, chaired by the Secretary of State, to ensure high level political commitment to English priorities. At the same time, the relationship between HM Treasury and individual departments would change, creating a national budget whose deployment reflects agreed national priorities.

These changes would facilitate devolution across England that would be backed up by a focus on local accountability, rather than national, (the failed audit system that has allowed the scandals of Thurrock and Woking councils would also be replaced). As part of this, the transfer of skills and resources to England’s localities would slim down Whitehall.

It is true that Whitehall has sometimes dipped its toe in “joined up government”. As far back as 2015, the Institute for Government had identified nearly 60 such initiatives in the previous 20 years. However, most have come and gone as departments learned to wait until the enthusiasm of passing ministers had faded and the Treasury used its iron grip to stymie the radical reform that England needs. Without political leadership nothing will change.

John Denham is director of the Centre for English Identity and Politics at Southampton University. He was communities secretary 2009-10

Philip Rycroft was head of the Brexit department 2017-2019. He is also former director general for education in the Scottish government and a former head of the Enterprise, Transport and Lifelong Learning Department in the Scottish executive

0 notes

Text

What should be in the Take Back Control Bill?

This note was submitted to members of Labour's front bench by the Society of Labour Lawyers and former Communities Secretary John Denham. It represents our initial thoughts on our contribution to the promised Take Back Control Bill (TBCB).

The aim of Labour policy

Paradoxically, English devolution has been regarded as a matter of central government policy, and too oftencharacterised as local government reform. Central government decides which powers and resources it might bewilling to devolve or delegate, under which circumstances, and to which bodies. Local government has no formal role, and only a very limited informal role, in shaping this policy. Consequently, local authorities can only respond to the central agenda. While this has enabled some slow and limited progress, the current ‘deals’ always reflect thepriorities and interests of the centre and can always be removed by the whim of the centre.

We understand that Labour now wishes to change this relationship, giving local government defined rights, duties, and powers, which cannot casually be removed. Local authorities will have, by right, enhanced powers to shape their local areas, to create larger bodies to meet the needs of wider geographies, and to gain new powers and resources. Collectively, local authorities should have a role in shaping government policy and become partners with the centrein developing English devolution. In essence, this would signify a fundamental transition away from reform of localgovernment, to creating devolved government in England.

In addition, Labour wishes to empower communities below the level of combined local authorities and current localauthorities.

We understand that it is no intended that the TBCB will alter London’s unique devolution status. English devolution also fits within a wider vision of UK constitutional change which provides for the protection of constitutional rights andthe representation of English ‘regions.’ Neither of these issues are addressed in detail in this note.

Our work

Our focus is on two aspects of the new and empowered role of local authorities. However, in considering the scopeof the TBCB, in our view it should broadly do three things, first; consolidate and simplify the devolution arrangements in England, second; enhance those arrangements, and third; protect the rights and powers of devolved and localgovernment in England, through ensuring their 'constitutional autonomy'.

The importance of the ‘constitutional autonomy’ of local authorities was recognised in the report of the UK Commission on the Future of the UK. It is also implicit in the speeches by Keir Starmer, Lisa Nandy and other shadow ministers which promise to provide communities with the right to request new powers, for Westminster to explain why powers have not been devolved and to plan for further devolution, and the power to enable local authorities to createCombined Local Authorities and wider structures.

English devolution is explicitly linked directly to Labour’s broader objective of closing the gaps – in productivity, health,income, wealth, education etc – that exist between and within England’s regions. This aim not only requires devolution ofthe appropriate powers but, crucially, ensuring that each part of England has the financial resources required to achieve‘levelling-up’.

In this note we set out our initial thinking on how the powers of local authorities should be reflected in the TBCB, and howthe TBCB might set out both the aim of closing the gaps within England, as well as provide for a formula for the distributionof resources to ensure that this can happen. At this stage we are less concerned with the detail of which powers are settled at which level than we are with the relationship between different levels of sub- national and national government.

Constitutional autonomy

In our view, “constitutional autonomy” in this context means:

That devolved and local government in England has an exclusive power to initiate action within theircompetences; and

That this exclusive power1 cannot be interfered with or taken away by another constitutional actor.

In order to create this constitutional autonomy, the TBCB2 must do the following:

Set out that the UK Government cannot exercise or interfere with the competences of local or devolved government in England (save in certain limited circumstances, discussed below.)

Entrench those powers/responsibilities devolved by the TBCB. That is, it should set out the procedure by which Parliament can remove or reduce those powers/responsibilities (such as through a super majority or otherprocedure which is more difficult than amending or repealing ordinary legislation).

Entrench the TBCB itself, so that the entrenchment protecting the powers of local and the devolved government inEngland cannot be circumvented by simply amending the TBCB.

Protecting the constitutional autonomy of local and devolved government in England in this way would, in our view, facilitate a change in the relationship between the UK and sub- national governments, from a supervisory to acooperative one.

1 Although a consent mechanism could allow local authorities to agree with proposed changes, there would also need to be robust inter-governmental structures to facilitate cooperation in these kinds of matters.

2 These proposals differ from the model of entrenchment, through a reformed House of Lords, proposed by the Commission on the Future of the UK which, currently, are to apply mainly to the constitutional relationships between the devolved administrations and the UK government, rather than English devolution. In any case, the TBCB needs toestablish effective entrenchment before reform of the Lords might have been achieved.

Empowering local authorities

England has many layers of local authorities, including parishes, districts, counties, unitaries, metropolitan boroughs, combined local authorities and a unique arrangement for London. It is impossible to provide each with its own constitutional status.

An inherent tension in English devolution is that it must create bodies of sufficient size and geographic reach toexercise sub-regional economic development and governance powers, as well as ensuring that powers lie at a sufficiently local level to empower people and their communities, rather than simply create a new layer of remotedecision-makers. This tension can only be resolved by giving the appropriate level of local government much more influence over the ability to form sub-regional or larger bodies, and more responsibility to empower localcommunities.

We suggest that the TBCB’s constitutional focus should be to empower ‘upper tier’ unitary, county and borough councils. This is the only level of government which exists in a broadly similar form in every part of England. Theselocal authorities should:

have the right to exercise defined powers in their own areas,

have the right to draw down additional powers to their areas,

enjoy the constitutive power to form combined authorities,

be subject to a legal duty of subsidiarity to enable districts, parish, and other local bodies to exercise powers at the most appropriate level.

In what follows, ‘local authority’ means these upper tier councils unless explicitly mentioned otherwise.

The TBCB will provide for each of these rights and duties.

It would require government to set out in the TBCB which additional powers will be enjoyed by local authorities andto identify those additional powers that might be exercised. It would set out the circumstances under which additionalpowers might be refused and the responsibility of central government to work with local authorities to enable them to do so.

The underlying principle is that once a power has been devolved it could only be taken away in prescribed circumstances such as a catastrophic failure of governance.

It would enable local authorities to form Combined Local Authorities (CLAs) and to pool existing powers as desire. The right to determine the membership and geography of CLA, and whether there should be an elected mayor, should lie with local authorities (notwithstanding that central government may set out the powers that are available to CLAs ofdifferent size and capacity – see below)

The duty of subsidiarity would set out how local authorities should exercise the duty, the ability of local people to challenge, and any oversight to be exercised by central government. (CLAs would also be subject to a duty of subsidiarity – see below)

Combined Local Authorities

There is broad agreement that some (but not all) aspects of skills, infrastructure, strategic planning, transport, netzero and other elements of economic development are best exercised above local authority level. CLAs shaped by localauthorities are the vehicle for doing so, and CLAs in turn should be able to work together to create wider bodies ifneeded.

CLAs would gain their powers and resources from two sources. Firstly, from the pooling of powers (including new devolved powers) that are devolved to local authorities. Secondly, from additional powers made available to CLAs fromcentral government.

Central government has a legitimate interest in ensuring that powers are devolved appropriately, but over prescription from the centre can slow progress, be ineffective and cut across local democracy. The TBCB should providea framework that facilitates a collaborative relationship between local authorities and central government. Local authorities and CLAs would work with central government within a framework of right, and not be subject toindividual ‘deals.

In like manner to the approach to local authorities, the TBCB should

set out what additional powers will be devolved by right to CLAs, subject only to meeting minimum criteria of capacity to exercise them effectively,

set out what additional powers may be requested by CLAs It would set out the circumstances under which additional powers might be refused and the responsibility of central government to work with local authorities to enable them to do so,

enable CLAs to work together to pool powers over a wider geography.

This approach will produce a ‘messy’ devolution, but within a broader framework which imposes a necessary level ofcoherence across devolved and local government in England. Not all CLAs will cover the same population, economy, orgeography, but this approach is more likely to ensure that each CLAs reflects the needs of its areas and popular local geography than the top-down imposition of uniform structures. The policy framework creates strong disincentives tothe formation of perverse or dysfunctional structures. However, should these emerge, they can always be reformed at alater stage.

The duty of subsidiarity

The need to exercise some powers at a regional or sub-regional level must not take powers away from lowerlevels of upper tier and district authorities. Both local authorities and CLAs would be subject to a duty of subsidiarity in which they set out which of their powers could be exercised at a lower level and how this will be achieved. For example, the holding of strategic transport powers should not prevent the devolution of, for example, LowTraffic Neighbourhood policy to district, parish, or community level.

The TBCB should provide for:

both local authorities and CLAs should be required to consult on and publish a community empowerment plans,

the power of local communities and councils to challenge the plan,

the legal powers required to devolved powers to a local level.

The fair distribution of resources

Tackling the inequalities between and within England’s regions will require a fair distribution of resources, sufficientnot only to meet immediate needs but also to reverse historic deprivation and lack of investment. At the same time, devolution will not succeed unless local authorities can rely on the sufficient, predictable, and consistent funding that underpins their autonomy.

Constructing a formula for fair funding is complex and contentious and could not be on the face of the TBCB. A fairfunding formula is also likely to encompass a variety of different sources of revenue and capital including current localdomestic and business taxes, possible future local taxes (e.g., a tourism tax), various forms of planning gain(including from increased land values), the proceeds of economic growth (including the retention of business rates’) the retention of some proportion of locally raised national taxation, and redistribution of taxation through centralgovernment. Account will also need to be taken of national funding that has not been devolved – for example, somepart of research funding. This will also be too complex for the TBCB (and aspects might in any case be moreappropriate for a future Finance Bill).

The agreement of a new funding formula should not be only a matter for central government. It should be designed through a statutory consultation process with a representative body of local authorities. (This body could be based on local authorities or on CLAs, although until all of England is covered by established CLAs, a local authority-based body will be the only available option.)

Hence the TBCB should:

place a responsibility on the government to ensure that each part of England has access to sufficient resources to closehistoric inequalities,

place a responsibility on the government to create a mechanism through which a funding formula to achieve thatresponsibility can be agreed between central and local government,

provide for the creation of a representative body of local authorities with a statutory duty and right to agree a fundingformula with central government (and to provide a resolution if this is not possible),

protect an agreed funding formula from arbitrary change by central government (for example where it is not agreed by thelocal authorities’ representative body) by requiring explicit parliamentary approval,

provide for the different fiscal mechanisms by which local authorities can enjoy greater fiscal autonomy.

The scope of policy devolution

Much of Labour’s discussion of devolution has been concerned with economic policy. In the past Labour has looked towider policy devolution, including health, social care, and the creation of pooled public service budgets. At the current time, upper tier local authorities have gained new statutory roles on Integrated Care Partnerships with responsibilities to improve health and social care and to tackle underlying health inequalities.

The framework we have outlined here would work for a much wider range of policy issues as and when a Labour government chooses to widen the scope of devolution.

Accountability

Devolution creates new challenges for political and fiscal accountability. Whitehall’s role as the collectiveaccounting officer for public funding has already created constraints on devolution. As more powers and funds aredevolved, the risks and the need for more effective accountability will grow. But if accountability is upwards to thecentre, then devolution will be hampered.

A new framework should enable current accounting officers to satisfy their responsibility provided they have followed proper procedures in devolving powers and resources. At the same time, far more robust audit and accountability mechanisms should be introduced for local authorities and combined local authorities through the creation of a newstatutory audit body with appropriate intervention powers.

Beyond fiscal accountability, empowered local authorities and CLAs should be subject to more robust scrutiny from elected councillors, local citizens and, for CLAs, member local authorities. This might be done by establishing robust minimumstandards (including autonomy, resources etc) for the current local scrutiny regime.

The TBCB should:

enable national accounting officers to devolve their statutory responsibilities to appropriate officers in local authorities orCLAs,

create a new statutory public audit office for local authorities and CLAs with intervention powers, and enable central government, after consultation with the representative body of local authorities, to publish minimum standards for local scrutiny,

establish principles for the operation of local government including standards of conduct in public life, transparency and openness to scrutiny by public and media.

The central governance of England

As the report on the Future of the UK identified, the conflation of the government of the UK with that of England does not work well for either England or the union. Machinery of government questions lie outside the scope of the TBCB, but it isclear that devolution within England will not happen effectively without creating a more effective and joined up system ofEnglish governance at the centre.

All the elements of English domestic governance that are currently scattered across a mixture of UK, British, Englandand Wales and England-only departments need to be effectively coordinated, perhaps under the leadership of an England office (and perhaps a Secretary of State for England). HM Treasury should engage more clearly with the government of England as a whole, and less with individual departments.

UK constitutional reform

We understand that wider UK constitutional reform lies outside the TBCB, and we have not considered this in detail. However, our proposals are consistent with those of the Commission on the Future of the UK. The creationof a representative body of local authorities would enable England to be represented within a Council of the Nations and Regions (and without the need for an elected regional body or individual). The establishment of a fair fundingformula with appropriate devolved powers would make progress on the achievement of shared economic and social right. The clearer delineation of England’s domestic governance would clarify English interests in intra-governmental structures and discussions.

0 notes

Text

‘Ministers like control, but Labour must offer radical, irreversible devolution

(First published on LabourList 29.9.23.)

Labour has promised a ‘Take Back Control Bill’ in the first King’s Speech. Aimed at England, it must bring to life Keir Starmer’s promise of a ‘whole new way of governing’.

But what sort of Bill? Will it entrench a fundamental and irreversible shift of power away from Whitehall and the UK government to England’s localities? Will it embed new constitutional rights for the people of England? Or, will it be more piecemeal tinkering of the kind we have come to expect?

Disregard for norms means we are sleep walking into a crisis

Those questions are sharpened by a new report on the UK constitution published by the Institute for Government and the Bennett Institute for Public Policy. As well as seeing a growing crisis as political leaders ignore unwritten rules and norms and constitutional checks and balances, they argue that parliament does not treat constitutional issues seriously enough.

They conclude that constitutional legislation should be clearly identified and given much closer scrutiny than happens at present. Once given constitutional rights would be significantly harder to remove.

Will the Take Back Control Bill be such a ‘constitutional act’ with all the protection of rights for England’s citizens that implies?

Labour’s devolution to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland empowered the peoples of those nations. (Our incorporation of the ECHR and the Freedom of Information Act empowered people across the UK).

Will the people of England also soon be empowered in this way? Will they now know that the local authorities they elect, and the combined authorities those councils form, will have the right to exercise devolved powers they need, rather than by the gift of the UK government?

Does England sit in a constitutional blind spot?

England has no constitutional status, and while England is not the main focus of the Bennet Institute’s report, it does conclude that ‘England is over-centralised, lacks coherence and does not have sufficient accountability mechanisms, creating a democratic deficit….(and that) there is a disconnect between Whitehall’s increasingly Anglo-focussed operations and its continued insistence that it governs at a UK-wide level, with a failure to differentiate between its UK wide and England-specific functions.’

Gordon Brown’s report for Keir Starmer also argued that the “confusion of the government of the UK with that of England… does a disservice both to the devolved nations and to England itself” and advocated constitutional autonomy for local authorities.

Reforms are certainly needed in Whitehall. Former Permanent Secretary Philip Rycroft, and I have recently set out what these should be. But the Bennett/IfG report also calls for a new English Governance Bill to clarify the powers and responsibilities of different layers of government. This, surely, is what the Take Back Control Bill must do.

That would make it a constitutional Act, not a simple piece of enabling legislation to extend current powers.

To understand why this matters, we can look at the successful return of franchised buses to Greater Manchester after 40 years. While the BeeNetwork rewards the ambition Mayor Andy Burnham set out six years ago, those who claim it as a triumph for the mayoral model do not realise that the legal and constitutional basis for the exercise of these powers is shaky.

It is determined by and dependent upon decisions taken by the Conservative central government, not on the leadership of individual mayors.

Without a constitutional fix, progress could be reversed easily

If ministers wanted, a simple legislative change could take away these franchising powers irrespective of the wishes of the people, councils or mayor of Greater Manchester.

In fact, the Conservative government has arbitrarily restricted franchising powers to the ten Mayoral Combined Authorities (MCLAs). Other local authorities and combined authorities – often covering much bigger geographies – would have to ask permission from Ministers with no guarantee of agreement.

More fundamentally combined authorities and their mayors do not have same legal status as other local authorities, or the London Mayor and Assembly. There is no collective status of being a combined authority – each has bespoke powers given at the whim of ministers.

Even the powers they have by regulation do not give them defined rights to exercise them, receive money in relation to them or enjoy financial autonomy in how they exercise those powers. Local authorities themselves do not have the right to establish combined local authorities (instead having to jump through Whitehall hoops). Local people have no say on these arrangements or even whether they want a mayor at all.

Labour could build on the current flimsy structure of ad hoc deals, perhaps making them simpler and offering some more powers, but keeping the real power over devolution in London.

Or it could see the Take Back Control Bill as a constitutional change, as Bren Albiston of the Society of Labour has argued, that empowers local people to take more decisions, draw down more powers and control more resources as a right, rather than by the whim of Whitehall.

We must learn from history and beware an ad hoc approach

The first option may be attractive to new ministers who want to enjoy tight control. But ten years of English ‘devo-deals’ has shown that this ad hoc approach devolves too little and in far too few places.

Not even the most powerful MCLAs in Manchester or the West Midlands have anywhere near the power they need to counter the impact of historic austerity, let alone reshape their economies, public services, or communities for the better.

Radical and widespread devolution will be critical to the delivery of Labour’s five missions and to making the best use of limited public finances. This means that the Take Back Control Bill should become the first step in placing England’s governance on a proper, devolved, democratic and decentralised basis.

0 notes

Text

Labour in Scotland - turning point or breathing space?

(First published on LabourList 23rd October 2023)

Labour’s stunning victory in the Rutherglen and Hamilton West by-election opens the door to many more Scottish Labour MPs.

Recent polling shows voters in Scotland prioritise getting rid of the UK Conservatives over choosing a unionist or independence MP. Tactical voting might bring further gains.

A major Labour recovery would, however, confront the party with a huge judgement call. Is this a turning point? Or is it a breathing space? Is it a return to ‘politics as usual’ in which the constitutional question is marginal, or is it a window of opportunity to re-think a better union?

Labour should not be complacent even if it wins big

An extraordinary series of events propelled the SNP forwards: dissatisfaction with Labour in Westminster and Holyrood, mass mobilisation during the Indy referendum that consolidated SNP leadership, the divergence from the UK government over Brexit, and dislike of the Tories. SNP momentum might well have stalled even if the leadership had not imploded.

If, though, we want a stable and popular union we should not be complacent. Support for independence remains at 47%. Former Ed Miliband advisor Ayesha Hazarika has warned: “Starmer will need to show the people of Scotland that a Labour government can deliver for (Indy supporters) and fast before the Holyrood elections in 2026. Those Scottish elections could well place the future of the union centre stage again.”

A new report by the think tank IPPR suggests that a stable union will need change in every nation, including making a shaper distinction between the governments of England and of the UK.

The idea of the union is by no means dead. Support for the principle of social and economic solidarity across the UK is strong, (even if voters are rather less keen to share their national tax revenues). Nor is there support for wide policy variation (which does not mean voters don’t want devolution). Other studies suggest Scottish voters want more than a simple choice between unionism or independence.

On the other hand, many voters feel their nation receives less than its fair share.

Voters think other nations get too much

Scotland tends to complain it gets too little while England thinks Scotland gets too much. Authors Ailsa Henderson and Richard Wyn Jones characterise this as a ‘union of grievance’. More than half of voters in each UK nation support either independence or are ‘union ambivalent’, meaning that support is qualified by other considerations.

Wales has the most voters who back the continued British union. Scotland has most independence supporters and fewest ‘union ambivalent’, England the least independence and the most ambivalent. English Leave voters were prepared to see the UK breakup to ‘get Brexit done’; but many English Remain voters thought that ‘losing faith in the union’ would be worth it to remain in the EU.

Most voters in England, Scotland and Wales favour Irish re-unification – far more than in Northern Ireland itself.

Only a small minority of voters see Britain as a single state with a single government. Support for ‘muscular unionism’ – asserting the union over its nations – a term associated with May and Johnson but first used to describe Scottish Labour policy, is limited in every nation and the very idea divides supporters of both the Labour and Conservative parties.

Crucially ‘there is no single British national identity with a shared understanding of the union…but….multiple versions of Britishness across the state, each associated with different and at times contradictory visions of the state’. The ‘British’ in England were generally Remainers, but being British in Scotland and Wales meant the opposite.

Those who prioritise their Irish, Scottish and Welsh identities are notably more pro-autonomy and pro-European than their devo-anxious and Eurosceptic English counterparts. The union simply cannot be held together by asserting the importance of a shared British identity or the power of the UK state.

Labour must advocate in each nation for each nation

Studies of Welsh and Scottish elections suggest Labour success in Wales and SNP dominance in Scotland rested on each party’s ability to present itself as best for the national interest.

In England the Conservatives mobilised English identifying voters over 20 years. In each British nation, Labour must be the best advocate for the nation within the solidarity of union, not just an advocate for the union.

The restiveness of Scottish voters will re-merge unless Labour can refashion both a devolution settlement and a new relationship with the UK government that really delivers for Scotland. Welsh Labour that has long advocated a ‘union of nations.’ In England the debate has not yet begun.

Labour’s new England membership card, which has no space for a St George Cross, symbolises a party that rarely speaks to England and does not distinguish Britain from England in politics or in governance. This very Anglo-centric British unionist outlook is a problem for the union and for England.

The IPPR report highlights ‘the tendency of the present UK Government (and those seeking to form the next one) to announce policy initiatives for ‘this country’, an entity whose borders are only very rarely specified’. How, it asks, ‘can the UK government avoid being regarded as an English government asserting its will over territory on which it currently does not enjoy a political mandate?’

Building a popular stable union means enabling Scottish Labour to stake its claim as best party for Scotland as well as supporting the union. Welsh Labour should continue doing the same. But both rely on Labour also having the courage to be the best party for England and not just for the union.

Turning point or breathing space? There may not be long to decide.

John Denham

0 notes

Text

Voters back courts; not so sure about ECHR

Once again, government sources are suggesting the UK should leave the ECHR if it is used to block the Rwanda policy. Former advisor to Theresa May and newly selected candidate Nick Timothy has claimed it would be easy to do[1]. The liberal centre and left combine horror at the proposal with the belief that it has no traction.

Voter views are by no means as clear cut. On the one hand, England’s voters overwhelmingly back court action to constrain illegal acts by government and parliament. According to new polling from the Centre for English Identity and Politics, 77% agree that ‘the courts should be able to stop a UK government or parliament acting illegally’. Only 7% disagree. There’s little sign here that voters want to assert the sovereignty of parliament or the autonomy of the executive over the courts.

On the other hand, attitudes towards the deployment of the ECHR are much less clear cut. Faced with the proposition ‘the ECHR should not prevent a UK government acting in what it sees as the national interest’ only 30% disagree. Many more (45%) do not want the ECHR to block government action, and 25% neither agree nor disagree.

The two questions are obviously framed differently[2], which will have influenced the results to some extent. But the differences between overwhelming support for the principle of court intervention and the underwhelming endorsement for the use of the ECHR is too stark for the framing to be a simple explanation of the change. What’s more, ahead of a general election, we should be interested in the way voters may respond to the ways issues are framed by political parties.

How do we make sense of this apparent contradiction? For many on the liberal centre and left the two questions are more or less identical. To them, the ECHR, which after all was enacted into UK law by an explicit decision of the UK Parliament, forms part of the body of law on which we should expect the courts to draw. But, as I have written previously, there is very little evidence from past polling that this view of the ECHR has ever gained broad popular acceptance. What was previously a body of law that drew on parliamentary statute and the accretion of common law was supplemented by a series of legal principles whose meaning only becomes apparent once applied by the courts to a particular set of circumstances. Whether this represents a stark break with previous legal tradition or something more akin to an evolution of it is a debate best left to jurists. In parts of the population, however, the perception that the ECHR is something ‘foreign’ and outside our traditions remains strong.

This becomes clearer when we look at how England’s different identity groups respond. (In this type of polling we can understand national identity as a broad cipher for how different groups see nation, national democracy, sovereignty, and the Union. It’s not about flags and football).

Those who emphasise their English identity are far more sceptical about the role of the ECHR. 63% of the ‘more English than British’ oppose the ECHR blocking government action while 33% of the ‘more British than English’ do so. Positive support for the Convention is strongest amongst the ‘more British than English’ (50%) and weakest amongst the ‘more English’ (15%).

What might this mean for the election?

Three things stand out to me from this data.

Firstly, ‘Convention scepticism’ is highest amongst the identity groups that Labour has found it most difficult to win (though it has made significant gains across all groups). I’ve written this polling up recently. English identifiers who previously voted Tory are also more likely to have moved from Conservative to Reform, Don’t Know and Wont’ Vote than to Labour. The ECHR appears to be an issue that might help win back the ‘low-hanging fruit’ of previous Conservative voters who have so far resisted the appeal of Labour, the LibDems or the Greens.

Secondly, support for the ECHR is by no means a consensus issues on which ‘all decent people’ agree. Fewer than one in three voters positively endorse the ECHR in providing a block to government actions. Perhaps just 30% of the population are obviously open to a defence of the principle that it is legitimate for the provisions of the ECHR to be used to block government action, particularly in areas like asylum policy.

Third, ‘convention-scepticism’ is by no means limited to a hard-core Brexit true believing minority. It has a significant if smaller presence amongst all identity groups. Assumptions that criticism of the ECHR will be anathema to all former Tory voters in ‘Blue Wall’ seats look overstated at the very least.

It’s not clear whether any of this will make the ECHR an important election issue even for those most who dislike the ECHR. While more voters support the Rwanda policy than oppose, there is also considerable scepticism about its efficacy. A major problem for the government is its incompetent mishandling of immigration. It may well struggle to persuade voters than everything would be working fine if only it was not for the ECHR[3].

What the government might hope, as pollster James Johnson suggests, is that supporters of the ECHR over-reach themselves. By talking about critics as though they are all beyond the pale, such supporters could feed the wider cultural divide that the current government is so keen to entrench.

It’s important not to build too much on this limited polling. But perhaps a defence of the ECHR should stress how it was enacted into UK law by the UK parliament (and much less on it being a shared international convention); the principle that no government should be above the laws made by parliament; and focus on how it has protected individual citizens against an overbearing state (and much less on the protection of asylum seekers).

Prof John Denham

Director, Centre for English Identity and Politics

University of Southampton

[1] He also thought the same about Brexit.

[2] One is framed as a positive choice and the other a negative; and the scope is different.

[3] Assuming for the moment that the Supreme Court overturns or significantly limits the policy

Polling conducted by YouGov 26/27 June 2023, 1716 voters in England

0 notes

Text

How England’s National Identities Are Planning To Vote?

With three by-elections on Thursday and more in the pipeline, I thought it would be interesting to look at how national identity in England is reflected in current voting intentions. The two decades from 2000 saw a marked polarisation of voting by national identity[1]. Even in 2001, English identifiers were more Conservative than other identity groups, but Labour still one the larger share of their votes. In subsequent general elections those more English trended further towards the Conservatives. By 2019, Boris Johnson was able to win 68% of the ‘more English than British’[2], while Corbyn’s Labour won amongst the ‘more British’[3]. In between those elections, English identifiers were the driving force behind the rise of UKIP and the Brexit Party in European and local elections and were decisive in the Leave victory.

England’s national identity groups are not distinct tribes, of course, but their position on the Moreno scale does correlate broadly with the demographics of age, higher education, and diversity, with socially conservative and socially liberal values (including on immigration), and with views of national sovereignty and democracy. There is little difference between identity groups on economic values. National identities reflect different world views and values and can be mobilised when the right issues are high on the agenda. After 2001 combination of strong views of national sovereignty and a desire to control immigration enabled the mobilisation of English identifiers around an increasingly Eurosceptic politics.

A big question for those who focus on national identity (let’s be honest, a lot of academics ignore English national identities entirely) has been whether the polarisation would persist if other issues dominated the political agenda. (There is much less difference between identity groups on economic values). The cost-of-living crisis and the dire state of public services are now much more prominent. Issues of immigration and sovereignty are kept alive by small boats and rows about the ECHR, but nothing provides the simpl(istic) solution Brexit once appeared to offer.

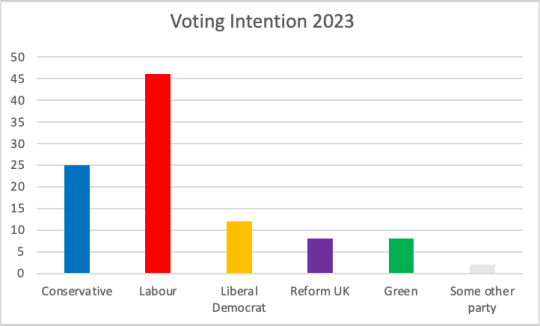

New polling from YouGov commissioned by the Centre for English Identity and Politics sheds some light on the new electoral map. In common with most current polling, it shows a strong Labour lead.[4]

Break the same polling down by identity groups and a marked divergence appears. Labour is ahead of the Conservatives amongst all the identity groups other than the ‘English not British’. But those emphasising their English identity are much less likely support to Labour, while those who emphasise Britishness or who have no British or English identity give strong support to Labour.[5]

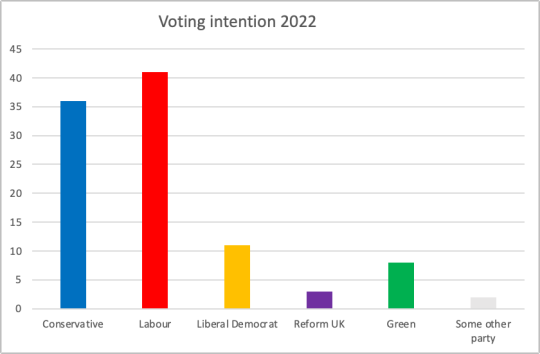

It's interesting to compare this recent data with a similar poll conducted in the run-up to the local elections in 2022.

This showed a smaller Labour lead, and when broken down by national identity group, the same skewed pattern is apparent.

The more significant changes in the last year took place at the ‘English end’ of the scale and reflect a fall in Conservative support as much as an increase in Labour support. Amongst the ‘English not British’ Conservatives support fell 21%, from 54% to 35%, while the Labour shared remained static on 27%. Amongst the ‘more English than British’ Conservative support fell 26%, from 54% to 28%, while Labour gained a modest 5% share, from 28% to 33%. Amongst the Equally English and British, the Conservatives lost 11%, falling from 41% to 30% and Labour gained 8% to reach 44%.

Between 2022 and 2023 support for Reform rose from 9% to 16% amongst the English identifiers; from 4% to 15% amongst the more English than British; and from 3% to 8% amongst the equally English and British. (This is in line with a presentation Prof Ailsa Henderson gave to a recent CEIP webinar showing that 2019 Conservative switchers were more likely to go to Reform if they were English identifiers and to Labour if they were British identifiers). Although excluded from the charts above, the raw data also shows those saying they won’t vote or don’t know rising from 31% to 37% amongst English not British, and from 17% to 38% amongst the more English than British. (The changes amongst other groups are much smaller).

A comparison of the recent 2023 polling with the outcome of the 2019[6] election shows the extent to which Labour has gained amongst all identity groups. Nonetheless, Labour support amongst English emphasisers remains well below their support amongst the other groups.

The alignment between English emphasisers and the Conservative Party that was so apparent in 2019 seems much less secure. The lead Labour has established since 2023 also owes as much Conservative losses as to Labour’s own gains.

The persistence of polarisation by national identity may partly reflect the historic tendency of English identifiers to be less supportive of Labour. Party alignments established over two decades may have a lingering influence on the rejection of Labour. It may also be that concerns about migration, social conservative values and a strong sense of national sovereignty may remain important to the English section of the electorate. While the Conservative Party can no longer mobilise them effectively, Labour still struggles reach many.

There is one further twist to this story. The Conservative Party ‘s ability to mobilise Leave supporting English identifiers was not clear even a few weeks ahead of the 2019 election. Polling conducted for the CEIP 16 days before election day showed strong support for the Brexit Party amongst English identifiers.

Through the previous two decades a growing section of English identifiers had switched between the Conservatives (and to a lesser extent Labour), UKIP and the Brexit Party depending on the election and who was seen as the standard bearer for Euroscepticism. In the event, the Brexit Party did not stand in Labour held seats in 2019 and the Tory appeal to ‘Get Brexit Done’ won over many other potential Brexit Party supporters.

There is clearly some potential for the Conservatives to win over Reform supporters at the next election and to outperform their current polling. There are fewer votes in play, the Conservatives do not have such a clear-cut offer to Eurosceptics, Reform is now the recipient of disillusioned Conservatives, and Labour has worked to keep Brexit off the political agenda.

The remaining polarisation will have a differential impact on constituencies. In some places –smaller towns and villages with older, less university educated and less diverse populations – the presence and influence of the English voters will be greater. If Labour’s poll leads narrows and some Tory defectors can be persuaded to return some seats may be more marginal than national polling would suggest.

John Denham

16.6.23.

Note: All polls conducted by YouGov for the Centre for English Identity and Politics at Southampton University. 27.6.2023; 21-22.4.2022; 2-3.12.2019

[1] as measured by the Moreno scale from English not British, through more English than British etc to British not English.

[2] English not British plus More English than British

[3] More British than English plus British not English

[4] The data excludes Don’t Knows and Will Not Vote, but has none of the adjustments for turnout, distribution of DKs etc used when trying to predict election results. We are interested here in underlying attitudes.

[5] The identity groups are not all the same size. In the 2023 poll, 15% English not British; 12% more British than English; 41% equally English and British; 10% more British than English 12%; British not English; 7% Other and 4% Don’t Know, making the equally English and British the larger than either the English or British emphasisers.

[6] Simplified to ‘more English’, ‘equally English and British’ and ‘more British than English’

0 notes

Text

Iraq - further thoughts

LabourList asked me to write a blog based on my comments a week ago, focussing on the contemporary lessons for Labour from the raw War. This was posted 30.3.23.

Twenty years on, Labour’s discussion of the Iraq War is curious and worrying in equal measure. The disaster often seems to have been absorbed into a wider factional politics in which positions on the war are more likely to be shaped by contemporary assessments of New Labour, Corbyn’s Labour and Starmer’s Labour than by lessons from the worst foreign policy disaster in our lifetimes. But twenty years ago, many firm supporters of New Labour were alarmed and appalled. Over half of Labour backbenchers voted against (and there were also abstainers, and ministers reluctant to collapse a government otherwise doing good things). My own resignation speech talked of a daily pride in our achievements.

In truth, as a party we have never really addressed the trauma. As leaders changed and times moved on there was a sense of putting it all behind us without really asking what it meant. This no longer seems possible. The architects of the UK’s involvement in the Iraq War have very largely been rehabilitated in British politics. Tony Blair is widely presented as an authoritative elder statesman, most recently publishing a report on technology with William Hague, one of the Conservatives’ most enthusiastic war supporters (the report itself is politically significant, suggesting that our challenges are technological rather than political).

Tony Blair shaped New Labour and, unlike most of our leaders, won elections, so it is worth understanding how he did it. Many talented people worked for him and guilt by association is never justified. On the other hand, Iraq happened because Blair had views of how government should be conducted and on Britain’s place in the world that were dangerously flawed. It is essential we understand why, and even more important to ensure that they are not taken up again now. New Labour’s achievements can be respected without believing that Tony Blair was anything but dangerously incompetent on both international affairs and British interests and in his conduct of government.