#vinciane pirenne delforge

Text

"PRÉSENTATION

La religion des anciens Grecs fait régulièrement l’objet d’introductions et de synthèses. Le présent ouvrage s’en distingue par la réflexion qu’il propose sur la pluralité inhérente à ce système religieux. En effet, la tension entre unité et pluralité, entre général et particulier est constitutive des relations que les Grecs entretenaient avec leurs nombreux dieux.

À partir de ce constat, plusieurs questions traversent le livre. Quelle est la pertinence des termes de religion et de polythéisme pour comprendre la Grèce antique ? Doit-on parler de « religion grecque » au singulier ou au pluriel ? Les figures divines se dissolvent-elles dans la variété de leurs cultes jusqu’à en devenir méconnaissables ? Peut-on parler de « croyance » dans ce cadre ? La pratique sacrificielle était-elle strictement locale ou bien fondée sur un arrière-plan partagé par toutes les communautés grecques ? En prenant l’Enquête d’Hérodote comme fil rouge, l’investigation entend rendre justice à un foisonnement de dieux et de rituels, et rendre intelligible la pluralité fluide d’un système complexe, bien loin de l’impression de chaos à laquelle nos propres déterminismes culturels risquent de le réduire.

English summary: The religion of the Ancient Greeks has already been the subject of a whole series of introductions and syntheses whose usefulness is no longer in doubt. The present work differs from them by the reflection it offers on the plurality inherent in this religious system. Indeed, the tension between unity and plurality, between the general and the particular, is constitutive of the relations that the Greeks had with their many gods.

Based on this observation, several questions run through the book: What is the relevance of the terms "religion" and "plurality"? Is there a "polytheism" to understand Ancient Greece? Should we speak of Greek religion in the singular or plural? Do divine figures dissolve in the variety of their cults to the point of becoming unrecognizable? Can we speak of "belief" in this context? Was the sacrificial practice strictly local or was it based on a background shared by all Greek communities? Taking Herodotus' Inquiry as a common thread, the investigation intends to do justice to a profusion of gods and rituals, carefully distinguishing between the fluid plurality of a complex system and the impression of chaos to which our own cultural determinisms risk reducing it.

Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge (born 1963 in Belgium) teaches at the University of Liege and since 2017 has been the Professor of Religion, History and Society in the Ancient Greek World at the College de France. Her main fields of investigation are the ancient Greek religion -particularly its gods and ritual norms-, the functioning of ancient polytheistic systems and the historiography of religions. She has notably published L'Hera de Zeus. Ennemie intime, epouse definitive (2016) and, more recently, Le Polytheisme grec comme objet d'histoire (2018)."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

One must recognise that Hera, in the stories that show her in conflict with Zeus, is constantly pressing to exercise her own power to the full and always demanding the recognition by her divine husband of her role as sovereign. The Greeks chose not to represent the Hera of Zeus as merely standing in the shadow of the king. Rather they preferred to imagine her as a counter-power which never ceases to issue challenges to her partner, Zeus – but challenges which, in the final instance, have the effect of reaffirming Zeus’s sovereignty.

(…) As a figure of the constructive eris (‘eris structurante’), Hera challenges the sons of Zeus to prove their legitimacy and issues the same challenge to the sovereign god himself in person.

- The Hera of Zeus: intimate enemy, ultimate spouse by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge and Gabriella Pironti

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

„A Macedonian curse tablet from the first half of the fourth century permits us to refine even further our understanding of ancient Greek perceptions of the relation between sexuality and marriage. It is a lovelor defixio by an abandoned woman, who curses the telos and the gamos which her former partner might enter into with any other woman or girl. The juxtaposition of these two terms in the first line of the text makes it clear that they are not exactly the same. Gamos refers to sexual union, a sense of the term particularly clearly present in the verb gameō. Telos, on the other hand, emphasises the aspect of an official engagement which constitutes the ‘full completion’, which would be the result of the project of uniting fully a man and a woman. In the Macedonian tablet, what the abandoned woman curses is not merely the possible sexual union of her companion with another woman, but also the formal engagement which would unite him with that other woman.”

- The Hera of Zeus: Intimate Enemy, Ultimate Spouse by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge & Gabriella Pironti

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I initially wrote this as an answer to this post, but the answer became too specific to me, my practice and relationship with Aphrodite that I thought it'd be better off as its own post (and to make sure the initial point wouldn't get lost in my rambling).

I've had a difficult relationship with Aphrodite.

For a lot of people - the ones who need it - she is the advocate for self-love and softness and kindness and the transcendence of love. With me? She was is the fiery storm of a goddess who's always had a very specific idea of what she wanted from me and would have done anything to get me there. Resisting her is useless, at least in my case, all it did was delay her advances.

It is the only time where I've told a deity "Fine. You win, I give up. Now do whatever you want with me because I can't do this anymore." Now, she (thankfully) didn't drag me in the dirt, but giving up control like that is an extremely difficult thing to do and leads you places. I don't know where, because she won't tell but we're definitely going somewhere.

The Aphrodite I deal with, the one she wants me to see is Epistrophia. I rarely call her this way. Both because it is an extremely localised epithet (Megara) but also because over time I've attached this side of her with other names. Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge summarizes that specific epithet this way: "Epistrophia embodies the nocturnal and potentially dangerous forces of sexuality, alongside the Dionysus of the night."

Clearly not surprising that this is the mask she wears with me. And maybe I'm tapping into a link of hers with Dionysus that simply didn't make it as much in the sources in other places as it did for Megara (thanks Pausanias), who knows?

All this to agree with @orsialos; Aphrodite knows madness, she knows mania, and one doesn't need to turn to myth to see the ravages.

The Anacreontea, Fragment 35 :

"Eros once failed to notice a bee that was sleeping among the roses, and he was wounded: he was struck in the finger, and he howled. He ran and flew to beautiful Kythere and said, ‘I have been killed, mother, killed. I am dying. I was struck by the small winged snake that farmers call "the bee".’ She replied, ‘If the bee-sting is painful, what pain, Eros, do you suppose all your victims suffer.’"

#aphroditedeity#aphrodite deity#it's the kind of shit that is all in your head until someone in your life uses weirdly specific language and you realize this is very real

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

LIRE "CIVILSATIONS : IDENTITE ET DIVERSITE"

LIRE “CIVILSATIONS : IDENTITE ET DIVERSITE”

Civilisations : questionner l’identité et la diversité

de Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge et Lluís Quintana-Murci (dir.) Éditions du Collège de France / Odile Jacob Collection « Colloques de rentrée »

Peut-on s’accorder sur une définition de la civilisation et utiliser le terme sans arrière-pensée ? Depuis son émer- gence dans le vocabulaire de l’Europe occidentale, cette notion a servi d’étendard…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hérodote, « historien des religions et du polythéisme » (1) - Religion, histoire et société dans le monde grec antique - Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge - Collège de France - 15 février 2018 11:00

Hérodote, « historien des religions et du polythéisme » (1) – Religion, histoire et société dans le monde grec antique – Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge – Collège de France – 15 février 2018 11:00

news of the world The Battle of the Allia was fought between the Senones (one of the Gallic tribes which had invaded northern Italy) and the Roman Republic. / in 2019, they join forces and return to polytheism….!! religious problems solved. celtic medicine.

Religion, histoire et société dans le monde grec antique – Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge

Source: Hérodote, « historien des religions et du…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"Chronique des activités scientifiques

Revue des livres

Comptes rendus et notices bibliographiques

Le Polythéisme grec à l’épreuve d’Hérodote

Theodora Suk Fong Jim

p. 290-293

Référence(s) :

Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge, Le Polythéisme grec à l’épreuve d’Hérodote, Paris, Les Belles Lettres / Collège de France, 2020. 1 vol. 13,5 × 21 cm, 251 p. (Docet Omnia, 6). ISBN : 978-3-515-12809-4.

Texte intégral

1 The last half century has seen a dazzling array of new approaches in the study of Greek polytheism. Moving away from a polis-centred model into which every student of Greek religion was once initiated, scholars have now advocated alternative frameworks ranging from ‘personal’ and ‘lived’ religion, to ‘network’ analyses, comparative perspectives, and the application of cognitive theories. Pirenne-Delforge’s latest book is a nuanced response to recent shifts in scholarly trends, and a critical reflection on current debates on the character of Greek polytheism. While revisiting old issues central and fundamental to the study of Greek religion, it offers a whole host of new insights into the analysis of Greek gods, the tension between unity and diversity, and the choice of conceptual tools by ancient historians.

2 The author confronts the thorny question of terminology from the outset: can we speak of Greek ‘religion’ when studying the ancient Mediterranean? Carefully tracing the history of the terms ‘religion’ and ‘polytheism’, she demonstrates that neither represents the ancient Greeks’ own use of word, and that their subsequent use is closely bound up with Christian polemics. Nevertheless, she reminds us, in historians’ attempt to avoid or get rid of terms with Christian associations, not only will we leave ourselves with no interpretive tool, we will also be perpetuating, consciously or unconsciously, the prejudice that Christianity is the true religion. In fact this ‘purge’ in terminology can go on: what about ‘religious’, ‘piety’, ‘thanks-giving’, ‘miracle’, and so on? Whether or not modern historians can give credence to the relations between the ancient Greeks and their gods, what is important is that they are recognized by the Greeks themselves. The definition of ‘religion’ chosen by the author aptly emphasizes this: its key element consists in ‘les relations avec la sphère supra-humaine dont cette culture postule l’existence’ (p. 55).

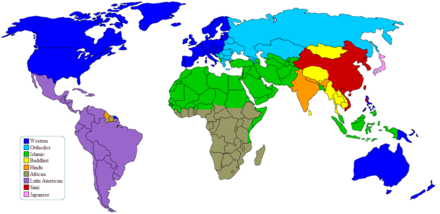

3 A central issue threaded through the whole book is the constant, and seemingly unreconcilable, tension between unity and diversity, the general and the particular, inherent in Greek polytheism. The question of ‘one or many’ has attracted scholarly attention in recent theoretical analyses of Greek cult epithets: to what extent is Zeus Meilichios the same as Zeus Ktesios? How much difference is there between the innumerable Zeuses bearing different epithets? Pirenne-Delforge shows, significantly, that the plurality (poly-) in the word ‘polytheism’ is not restricted to divine figures but is manifest at every level of Greek religion, from sacrificial and other ritual practices, to cult places and sanctuaries, divine names and epithets, and conceptions of the divine: these might vary between different levels of organization (Panhellenic, regional, polis, sub-polis, and so on), from place to place, from one individual to another, and across different time periods. So overwhelmingly diverse is every aspect of Greek polytheism that the singular ‘religion’, one may object, can hardly capture its diversity. Pirenne-Delforge categorically emphasizes the plurality and multiplicity inherent in Greek polytheism on the one hand, but on the other reaffirms the value and validity of Greek ‘religion’ in the singular. To speak of Greek ‘religion’ (rather than ‘religions’), in her view, is not to obscure or obliterate the bewildering plurality in Greek polytheism, but to recognize that ‘une certaine unité sous-tend les relations que les Grecs entretenaient avec leurs dieux’ (p. 95).

4 To demonstrate that this unity is not a construct invented by the historian, Pirenne-Delforge puts her arguments to the test by using Herodotus, who best documents the diversity of religious customs (nomoi) across and within ancient Mediterranean cultures. Close analysis of his Histories and other sources reveals that ‘Greek gods’ and ‘Greek sacrifice’ existed in the ancient Greeks’ own representation of theia pragmata. Such categories tend to lie ‘dormant’ in the Greeks’ perception of religious matters, but come to the surface when a contrast is made with non-Greek phenomena or in a foreign milieu. A question nevertheless remains: in the absence of a centralized religious authority, what gives unity to Greek polytheism? How far can regional, local, and personal variations go before any element loses its ‘Greekness’? Other eminent scholars have conceptualized aspects of this tension using the symbolism of a concertina (capable of expansion and contraction) or kaleidoscope (capable of changing from one to many varied visions),1 whereas Pirenne-Delforge stresses that both unity and diversity are constitutive of our understanding of Greek polytheism, and have to be studied together at every level of analysis. These two forces, the unifying and diversifying, the centripetal and centrifugal,2 hold each other in check, so that there was a limit to how far variations could go.

5 The analysis of the Greek gods has undergone various important shifts in paradigms over the last few decades. The ‘structuralist’ approach associated with Vernant and Detienne emphasizes that Greek gods were divine powers rather than persons, and that they need to be defined in relation to other powers in the pantheon. Versnel in Coping with the Gods (2011) is similarly preoccupied with the question of ‘one or many’, but he is anti-structuralist in stressing the inconsistencies in the Greeks’ perception of the gods and their ability to entertain multiple conceptions of a divine figure. Pirenne-Delforge’s present volume builds on what one might call the ‘neo-structuralist’ approach which she has developed in collaboration with Pironti. While recognizing the anthropomorphic tendencies in the Greeks’ perception of their gods, she follows Vernant in stressing that a god is not a ‘person’, but a divine power with a broad spectrum of competences (technai). Despite the potential plurality of each divine figure, she argues, ‘quelque chose de stable paraît transcender la polyonymie de chaque figure divine’ (p. 128). She uses the symbolism of a ‘network’ (réseau) to capture the dynamic powers and different attributes of each god. Nevertheless, it is unclear if the concept of a network necessarily leads to ‘quelque chose de stable’: all that it emphasizes is the interconnected nature of a god’s different powers, but that was already the assumption underlying what Parker calls the ‘snowball theory’ of polytheism.3

6 After almost two decades of lively debates on the relevance of ‘belief’ in the study of Greek polytheism, most historians now recognize that ‘belief’ existed among the Greeks in a broad sense without Christian overtones, that a plurality of different ‘beliefs’ coexisted, and that ‘belief’ is indispensable in making sense of the Greeks’ relations with their gods. Nevertheless, beyond these broad consensuses, progress in the investigation of ‘belief’ seems to have reached an impasse. Pirenne-Delforge takes the subject further by taking a fresh look at the closest Greek equivalent nomizein. The two aspects of its meaning—the ritualistic sense of ‘to practice and observe as a custom’, and the cognitive sense of ‘to believe’, ‘to recognize as gods’—have often been considered separately, whereas Pirenne-Delforge emphasizes that they are two sides of the same coin. To recognize a certain figure as god, in her view, implies a whole series of rituals and cultic actions rendered to the god concerned, and therefore nomizein tous theous in effect means to integrate the gods in the nomoi of the society. The cognitive recognition of a god in one’s mental sphere is expressed in religious customs, and so we should no longer prioritize ritual as primary or more important than belief. Even for phenomena such as divination and sacrifice, which seem manifestly ritualistic, Pirenne-Delforge demonstrates that these practices are in fact closely linked with the Greeks’ representation of the gods.

7 Other key issues arising from the book include the relations between gods in literature and gods in lived religion, the boundary between ‘public’ and ‘private’ religion, and the relations between the Panhellenic and the local. Each side of these dichotomies tends to form a separate object of analysis in existing studies and is rarely brought together or considered on the same plane in any given analysis. Yet Pirenne-Delforge almost effortlessly brings together different aspects, reminding us that the boundary in these polarities is fluid, permeable, and often ill-defined. In fact hardly any phenomenon in Greek religion can be studied solely from the perspective of either the polis or the individual, the literary or the cultic, the general or the particular, when both aspects are complementary to each other.

8 Forcefully argued and remarkably well-informed, this profoundly thoughtful book beautifully brings together a great deal of valuable insights and an impressive amount of learning resulting from many years of reflection on this subject. It challenges future generations of students and scholars in Greek religion to aspire to a new standard: to study Greek polytheism in its different manifestations and in its totality, and to deploy a multiplicity of perspectives for understanding the complexity of what can justifiably be called Greek religion.

Haut de page

Notes

1 R. Parker, On Greek Religion, Cornell, 2011, p. 87; H. Versnel, Coping with the Gods, Leiden, 2011, p. 212; M.S. Smith, Where the Gods Are, New Haven, 2016, p. 57.

2 E. Kearns, “Archaic and Classical Greek Religion”, in M.A. Aweeney, M.R. Salzman, E. Adler (eds.), The Cambridge History of Religions in the Ancient World, Cambridge, 2013, p. 281–284.

3 R. Parker, On Greek Religion, Cornell, 2011, p. 86.Haut de page

Pour citer cet article

Référence papier

Theodora Suk Fong Jim, « Le Polythéisme grec à l’épreuve d’Hérodote », Kernos, 34 | 2021, 290-293.

Référence électronique

Theodora Suk Fong Jim, « Le Polythéisme grec à l’épreuve d’Hérodote », Kernos [En ligne], 34 | 2021, mis en ligne le 31 décembre 2021, consulté le 03 octobre 2023. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/3913 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.3913Haut de page

Auteur

Theodora Suk Fong Jim

University of Nottingham

Articles du même auteur

Seized by the Nymph? [Texte intégral]Onesagoras the ‘dekatephoros’ in the Nymphaeum at Kafizin in CyprusParu dans Kernos, 25 | 2012

The vocabulary of ἀπάρχεσθαι, ἀπαρχή and related terms in Archaic and Classical Greece [Texte intégral]Paru dans Kernos, 24 | 2011 "

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

She is the guardian of the particular oikos (the household, the family line) that is Olympus; she keeps watch over its integrity, and because she presides in her own way over the adoption of new members, she reveals herself to have the power of granting legitimacy.

- The Hera of Zeus: intimate enemy, ultimate spouse by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge and Gabriella Pironti

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Rose, myrtle and lychnis are all preferred plants of the goddess, which could be used to weave wreaths in her honor. The ancients explained these choices in various ways: plants with shapes evocative of the goddess's powers, a rose born at the same time as her, or lychnis emerging from the bath she took after uniting with Hephaistos.

Myrtle is an aromatic shrub often associated with Aphrodite in myth and history. The leaves of a myrtle growing near the sanctuary of Aphrodite Kataskopia in Troezen were nervously mistreated by Phaedra as she watched Hippolytos train in the stadium below. The statue of Aphrodite offered by Pelops, who wished to marry Hippodamia, was sculpted from myrtle wood. A variant of the story of Myrrha and her son Adonis suggested that he was the result of his mother's metamorphosis into a myrtle shoot rather than a myrrh tree. In a Cretan tradition, the nymph Britomartis, fleeing the advances of Minos, was restrained by her peplos tangled in a myrtle branch. These various mythical episodes clearly indicate the plant's relationship with sexuality and its semantic connection with Aphrodite.

At the boundary between legend and history, myrtle, miraculously growing around a statue of the goddess, is said to have saved a ship from shipwreck, with its fragrance relieving sailors of seasickness. This episode is independent of any erotic connotation but simply signifies the action of the goddess through a favored attribute. Historically, myrtle branches were used to weave wreaths for newlyweds in Attica.

The funerary connotations of the plant should not be overlooked in the study of its relationship with Aphrodite, who herself is related to the world of the dead in certain places in Greece. Indeed, myrtle could be offered on graves and was associated with underworld deities, as stated by a scholiast of Aristophanes. It has been convincingly shown that this association was clearly based on the presence of myrtle in the ceremonies of the mysteries of Demeter and that myrtle was more a symbol of life than a funerary plant. Like the goddess of whom it is a privileged symbol, myrtle represents the power of life, and even more precisely, the path to immortality because its sensual fragrance is the very evocation of divinity. It is no coincidence that in the Iliad, it is Aphrodite who spreads a fragrant ointment over Hector's body, meant to protect the hero from the ill treatment of his corpse by Achilles."

- Adapted from L'Aphrodite grecque by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge

#aphrodite#plants#myrtle#why hasn't this book been translated in English yet?#I'm struggling here#quotes#excerpts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphrodite Epitragia: beyond Aphrodite Pandemos

Often, when one finds this epithet of Aphrodite, it is in reference to the many iconographical depictions of her riding a goat. Such depictions seem to appear towards the end of the Classical era and refer to her role as Pandemos, especially in Athens, which Plutarch explains in Theseus, 18:

"When the lot was cast, Theseus took those upon whom it fell from the prytaneium and went to the Delphinium, where he dedicated to Apollo in their behalf his suppliant's badge. This was a bough from the sacred olive-tree, wreathed with white wool. Having made his vows and prayers, he went down to the sea on the sixth day of the month Munychion, on which day even now the Athenians still send their maidens to the Delphinium to propitiate the god. [2] And it is reported that the god at Delphi commanded him in an oracle to make Aphrodite his guide, and invite her to attend him on his journey, and that as he sacrificed the usual she-goat to her by the sea-shore, it became a he-goat (‘tragos’) all at once, for which reason the goddess has the surname Epitragia." (trans. Bernadotte Perrin)

At first glance, it is hard to see how Aphrodite Epitragia relates to Aphrodite Pandemos or even the Aphrodisia. According to Plutarch, Aphrodite Epitragia places herself as Theseus' personal guide in the journey that would lead him to accomplish the synoikismos (lit. "coming together" of cities) and establish the cult of Aphrodite Pandemos, which is at the heart of the Aphrodisia.

While the depictions of Aphrodite riding a goat appear quite early on in Athenian history, the epithet "epitragia" only appears in later sources, one being the quote cited above from Plutarch, and the other being an inscription on one of the seats in the Theater of Dionysus, also dated from the 2nd century AD, probably the seat reserved for the clergy in charge of Aphrodite's cult under this epithet.

And this is, honestly, quite curious. If Aphrodite riding a goat was, until the turn of the millennium, mostly an iconographical and artistic depiction referring to her role as Pandemos, it is surprising to see that the cult of Aphrodite Epitragia had a clergy, as attested by the presence of the seat in the theater, and it mostly raises the question of the purpose of the cult. Was it different from the cult of Aphrodite Pandemos? If that was the case, how so? Was the cult of Aphrodite Epitragia always there despite the fact we have no trace of it before the 2nd century AD? etc.

In L’Aphrodite grecque, V. Pirenne-Delforge interprets Epitragia as a guide in the sexual coming of age of Theseus. In the same manner that another legend associates the cult of Aphrodite Pandemos as a patron the sexuality of young people through the opening of a brothel under Solon (6th century BC), the Thesean version would represent Aphrodite foreshadowing the metamorphosis of Theseus from a child to a man with the miraculous change from a she-goat to a he-goat. V. Pirenne-Delforge also points out that the image of Aphrodite riding a goat is not exclusively used to refer to Pandemos, as it is the case on ex-votos where she is represented in her Ourania aspects as well.

Still according to the same author, both the epithet and the iconographical trope seem to have been more akin to a protection than an actual representation of the goddess, popularized by the sculpture of Scopas in Elis, which represented Aphrodite in this manner (unfortunately lost to us). This conclusion can only be reevaluated if we find depictions of Aphrodite Epitragia that were made before the 4th century BC.

Further reading:

Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge, L’Aphrodite grecque. Contribution a l’etude de ses cultes et de sa personnalite dans le pantheon archaique et classique, 1994

107 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Philoinfo.fr - L'actualité philosophique en vidéos ! https://ift.tt/2J2uJqT Philoinfo.fr - L'actualité philosophique en vidéos ! https://ift.tt/2knG8KW

0 notes

Text

Graeco-Aegyptiaca | V. Pirenne-Delforge: Herodotus as an historian of religions and polytheism

youtube

"The Graeco-Aegyptiaca online seminar started in January 2022 with papers given monthly by established scholars in the field of Egyptian and Greek cultural relations. The second season's second event "Herodotus as an historian of religions and polytheism: the Egyptian matrix” was held by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge (Collège de France, FNRS) on 29 November 2022.

The lecture aims at addressing some well-known passages of Herodotus’s Book 2 about the origin of the gods and the place of the divine in his inquiry. The fact that these passages, crucial for the modern historian of religions, are embedded in the developments on Egypt is related to the Greek vision of the depth of Egyptian time, but the overall framework remains purely Greek and refers to what we call “Greek religion”.

Graeco-Aegyptiaca is a collaborative initiative by colleagues in the fields of Egyptology and Classics based in Hungary and the United Kingdom. The project aims to bring together researchers interested in the history of cultural interaction between Egyptians and Greeks from the very beginning to the Byzantine period."

1 note

·

View note

Text

„So not only does Hera push the hero to combat these dangerous creatures, she herself explicitly brings them up with the intention of unleashing them on him. The striking image of the consort of Zeus who is the nurse of monsters does not necessarily contain a reference to some earlier chthonic deity, traces of whom can be found in the figure of Hera. What is essential here is the goal that Hera is pursuing in raising these creatures. They are both expressions and instruments of Hera’s anger, and she shapes them into the form they have in order to persecute her adversary, just as that adversary is called upon to conquer them in order to acquire glory.”

„Let us consider more carefully these terrible creatures which, according to Hesiod, Hera raises. They are the offspring of Echidna and of Typhon, monstrous, formidable powers who beget a whole series of menacing creatures: the dog Orthos, Cerberus, the Lernaean hydra, the Chimaera. The Nemean lion and Phix (the Sphinx whom Hera is said to have sent against the Thebans) belong to the same brood.”

„It will be the task of the heroes, sons of Zeus, and particularly of Herakles, to rid the world of these noisome creatures. The association of Hera with this family of monsters, who map out between them a whole landscape of heroic exploits that need to be performed, is particularly interesting in light of the tradition which makes Hera the mother of Typhon, the last and more fearful adversary of Zeus.”

- The Hera of Zeus: intimate enemy, ultimate spouse by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge and Gabriella Pironti

#This book is everything I hoped it to be and more#Hera#basileia#helpol#hellenic polytheism#greek mythology#my notes

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

„Gods systematically punish mortals who have the audacity to compete with them in any domain at all, but especially in one which is supposed to be part of their special competency. This is why the punishment of those who offend the gods so often takes the form of contrappasso. This suggests that Hera is especially concerned not just with marriage and the prosperity of the oikos but also with beauty, her own and that of mortal women. Nor is it only in literary contexts that a relation is presumed to exist between Hera and beauty: a beauty contest called Kallisteia was organised by the women of Lesbos in honour of the goddess in her own sanctuary.”

- The Hera of Zeus: intimate enemy, ultimate spouse by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge and Gabriella Pironti

12 notes

·

View notes