#they don’t know how to make ironic self referential humor

Photo

Editor's note: while I've certainly been away from Can't You Read for quite a while, anyone who follows my work at ninaillingworth.com or my Patreon blog already knows that I've been writing (and podcasting) again. You can check out some of my latest essays here, here and here; to listen to the podcast I co-host with Nick Galea (No Fugazi) just click here.

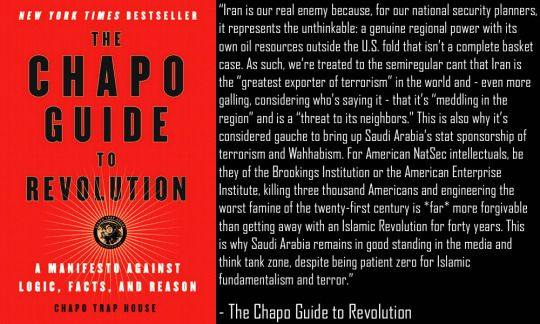

Today however I'm back on my bookworm bullsh*t with another curiously dated review of left wing literature from my extensive library of pinko pontification. In today's review, we're going to be taking a look at “The Chapo Guide to Revolution: a Manifesto Against Logic, Facts and Reason” written by five members of the popular left wing podcast “Chapo Trap House” - specifically, Felix Beiderman, Matt Christman, Brendan James, Will Menaker and Virgil Texas.

Baby Steps up the Ramparts

It is I will theorize, utterly impossible to write a review about the Chapo Trap House book without engaging in the extremely online, three-sided culture war that has sprung up around both “the Chapos” themselves and the enormously popular podcast they host. In light of the fact that seemingly everyone on the internet who detests the show regard the Chapos as slovenly crackpot losers born on third base and podcasting from mom's basement, it really is alarming how much digital ink has been spilled about the various types of “threat” to all that is good and holy this simple irony-infused podcast supposedly represents. While I intend to largely sidestep that discussion by focusing entirely on the book and not the podcast (which I don't listen to regularly, to be honest with you), I accept that virtually nobody reading this is going to be happy unless I do something to address the elephant in the room, so here goes:

Neera Tanden and her winged neoliberal monkeys can eat sh*t, but extremely online leftists have a point that the Chapos themselves occasionally skirt the line between mockingly ironic reactionary thought and just plain old reactionary thought; although this is not particularly alarming to me because they're Americans and America itself is a breeding ground for reactionary ideas – decolonizing your mind is a process and I'm pretty sure it's one I myself am also engaging in still every single day of my life at this point. Importantly, in my opinion this failing does not make them cryptofascists so much as the product of American affluence; I'm having a hard time understanding how teaching Marx and Zinn to Twitter reply guys serves the fascist agenda in any meaningful way.

While I obviously can't pretend to know another person's heart, in my opinion the Chapo boys are definitely leftists but they're obviously not labor class and yes it's a little hard to explain away the group's loose affiliation with the (objectively strasserist) Red Scare podcast through co-host Amber A'Lee Frost - but I'm not going to waste a couple thousand words trying to untangle Brooklyn independent media drama from half a country away and besides, Amber didn’t write this book. Despite these critiques however, I think it's important to note that under no circumstances am I prepared to accept the argument that with fascists to the right of me, and lanyards, um also to the right, the real problem here is... Chapo Trap House.

Ok, with that out of the way let's dive right in and talk about the question I think most folks who've written about The Chapo Guide to Revolution have largely failed to grasp – namely, what kind of book is it precisely? Combining elements of comedy, playful online trolling, historical analysis, political theory and good old-fashioned cross platform promotional marketing, the book has often lead critics to compare it to catch-all comedic efforts like Joe Stewart's “America” or even humorous men’s lifestyle advice texts like “Max Headroom's Guide to Life.” This is I think an essential misreading of the fundamentally earnest and direct tone the book actually takes in its efforts to reach a fledgling audience growing more receptive to left wing ideas. The Chapo Guide to Revolution is, as the cover says, a manifesto; but rather than serving as the mission statement for a particular formed political ideology, the Chapos have written an extremely effective, entry-level argument for why labor-class millennials should be leftists – and, of course, why they should listen to Chapo Trap House; this is still a cross-promotional work after all.

Naturally as befits a book about a comedy podcast, albeit a very political one, the Chapo Guide to Revolution is an extremely funny book that does a remarkable job translating the type of caustic online humor previously only found in left wing Twitter circles, onto the written page. While its certainly true that this quirky style of comedy can be a little difficult to grasp for the uninitiated, and typically a cross-promotional work of this type will get bogged down in self-referential humor and inside jokes, the book mostly avoids this trap by sticking with the basics and assuming that the reader has literally never heard an episode of Chapo Trap House, which in turn makes the humor fairly universal and extremely accessible – at least for anyone under the age of fifty. This endeavor is greatly aided by the dark and dystopian, yet hilariously eviscerating art of Eli Valley; a man who himself has since become one of the leading left wing critics of establishment power online through his extremely provocative sketches and ink work.

The truth however is that if the Chapo Guide to Revolution was merely just a funny book, I wouldn't be reviewing it here today. No, the reason this book is worth writing about at all lies in the fact that underneath all the jokes, taunts and “half-baked Marxism” lies an objectively brilliant work of historical analysis, cultural critique and left wing political theory – albeit an unfocused theory that borrows heavily from half a dozen functionally incompatible left wing thinkers and literary giants, but a fundamentally serious work of political philosophy nonetheless.

Yes, that's correct; I said brilliant. Where think-tank minions and neoliberal swine in the corporate media see a petulant pinko tantrum, and online leftist academics see privileged dudebros appropriating Marx (poorly), I see a brilliant and yet stealthy synthesis of political theories, historical analysis and organizational ideas originally presented by writers like Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky and Thomas Frank. Drawing on historical theories from Marx, Gramsci and Rocker, the Chapos have cobbled together a rudimentary political philosophy that represents a crude and yet promising welding of anarchist concepts about labor, Marxist concepts about economics and democratic socialist concepts about politics, collected together under the generic banner of “socialism.”

At this point some of you are undoubtedly snickering, but please bear with me for a moment here because what the Chapos (or their ghostwriter) have done in this book is truly a marvelous thing to behold precisely because you can't see it unless you're paying close attention. By positioning The Chapo Guide to Revolution as both a comedic work and an introductory level text, the authors have created a sort of unique crash course in left wing history, geopolitics, philosophy and political theory for a newly awakened generation of Americans who find themselves increasingly politicized whether they like it or not.

Underneath the acerbic millennial humor, “extremely online” diction and unrelenting waves of sarcasm, The Chapo Guide to Revolution is also a surprisingly accurate “CliffsNotes” style textbook presentation of multiple broad-based social science subjects – here are just a few examples:

In “Chapter One: World” the book presents a rudimentary and yet deliciously insightful history of post-World War II American empire that draws on authors like Howard Zinn and Noam Chomsky, with a touch of contemporary writers like Greg Grandin and Naomi Klein. In particular the attention devoted to condensing the target audience's formative experiences with empire like the War on Terror, the invasion of Iraq and the war in Afghanistan, into a short and coherent narrative that can be easily shared with other novice political observers makes this book an invaluable resource for budding millennial leftists Additionally, while it certainly might have been an accident, the Chapos' choice to wrap this “Pig Empire geopolitics for newbs” lesson in a protracted joke about America as an extremely ruthless corporate startup at least touches on ideas presented by writers like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Sheldon Wollin (or Chris Hedges repeating Sheldon Wolin), Joel Bakan, Rosa Luxemburg and others.

In Chapters Two and Three, entitled “Libs” and “Cons” respectively, the authors conduct a remarkably thorough political science lesson on the two major mainstream political “ideologies” in American culture, including both a rough outline of their history and their modern calcification inside the Democratic and Republican parties. Of course both of these sections rely heavily on the personal experiences of the authors growing up in a politicized America, but these discussions also dip into the works of Thomas Frank and Cory Robin to explore and critique the liberal and conservative political mindset respectively; in particular the Chapos summary of Robin's work on the conservative worship of hierarchies is an inspired distillation. More importantly however, the Chapos also expose the way in which these two ideologies represent a false dichotomy within the greater confines of a larger capitalist socioeconomic order; which is of course a (still absolutely correct) idea straight out of the works of Karl Marx.

In Chapter Six, appropriately entitled “work” the authors engaged in a disarmingly earnest discussion about wage slavery, the false promises of the protestant work ethic and the history of terrible jobs available to the labor class under various iterations of the capitalist project. This is followed by a humorous, but dystopian review of what future jobs might look like if the neoliberal socioeconomic order continues on as it has so far, and an extremely brief but sincerely argued pitch for completely transforming the role of work in society through some from of technologically assisted anarcho-communism. This last idea is admittedly a little half-baked but you have to admire their balls when the Chapo boys flatly call for a three hour workday; a position that will undoubtedly be popular with the labor class who're currently engaged in all those sh*tty jobs the book describes earlier in the chapter. Once again this synthesis of left wing ideas about work does represent a new and unique formulation, but despite the humorous and original content you can also clearly see the influence of anarchist writers like Kropotkin, Rocker and Goldman in this chapter, as well as contemporary authors like David Graeber and Mark Blyth.

Unfortunately, if there is a downside to writing a brilliantly subversive comedy book that functions as a “my little lefty politics primer” for politically awakening millennials, it's that you simply don't have the space for an intellectually rigorous examination of all the ideas you're sharing – there is after all a big difference between reading the Cliff Notes version of Zinn, Chomsky or Marx, and reading the original theories in their full form. Furthermore, the individual life experiences, idiosyncrasies and humor styles of the authors do at times bleed into the text in a way that I personally suspect was detrimental to the overall analysis. Here's a short list of “sour notes” I found in this otherwise remarkable book:

From what I have listened to of the Chapo Trap House podcast, it has always been my impression that the Chapos were particularly effective critics of American corporate media, so I was a little disappointed that the chapter on media in The Chapo Guide to Revolution was a fairly tepid and narrow discussion about (admittedly vapid) bloggers turned celebrated pundits. Don't get me wrong, I'm sure power dunking on the likes of Matty Yglesias, Meagan McArdell and Andrew Sullivan was viscerally satisfying for the book's target audience, but there's really not much of a broader critique of the media's ideological role in American capitalism and culture here like one would find in Herman & Chomsky's “Manufacturing Consent”, Matt Taibbi's “Hate Inc” or Michael Parenti's “Inventing Reality.” This absence I fear has the tragic side effect of reinforcing the idea the American corporate media sucks because egg-shaped moron bougie pundits are bad at their job and not because of the inherent failings of the for-profit media model and the institution's true role as an ideological shepherd keeping the masses aligned with the goals of elite capital and the ruling classes – almost exclusively against the bests interests of the labor class.

The introduction is written in what I can only assume is a sarcastic imitation of right-leaning self improvement books with a touch of Tyler Durden's Fight Club ethos thrown in; this might have been a better choice in a completely different book but it's largely out of place with the rest of this book. At this point I should also say that the best part about the Kidzone intermission is that it was only two pages long. Needless to say, neither one of these sections did anything for me whatsoever.

While it's entirely possible that at forty-three years of age, I'm simply too old to really get the “millenialness” of the chapter on Culture, the simple truth is that I found most of it to be a fairly useless examination of pop culture influences the Chapos hold in reasonably high esteem. As someone who isn't particularly engaged in watching lengthy television series or regularly playing video games, I really couldn't dig into most of the material presented and the less said about the art jokes and the bizarre absurdist discussion of elevator brands, the better. There is however one rather notable exception here in the brief essay on The Sorkin Mindset, which is an objectively brilliant evisceration of the liberal obsession with the West Wing and the tragic effect that obsession has had on Democratic Party politics – this really could have gone in the chapter on “Libs” because it's that valuable of a tool for understanding and critiquing the modern liberal lanyard worldview. Finally I guess I should note that while the Chapo boys' insightful critique of the vapid “prestige TV” phenomenon is both interesting and correct, it really only “matters” if you're a consumer of these types of series – and I'm not.

While I certainly understand the authors' decision to use their notes section to preemptively debunk bullsh*t complaints about the more outrageous accusations they level against the American establishment, I would have liked to see a “recommended reading” section. It is very clear that the Chapos have a reasonably strong background in imperial history, political science and labor theory and I feel like pointing readers towards writers who expand on the theories they summarize in The Chapo Guide to Revolution might have been a better use of space than printing links to old internet articles bad faith actors will never type into a search engine anyway.

Although it might seem like there was more about the book I didn't like, than I did, this is a little misleading – the first three chapters of The Chapo Guide to Revolution are pure fire and comprise over half of the volume. If you throw in the brilliant chapter about work and labor theory, the overall package is far more substance than style, despite the fact that it remains humorous and a little bit edgy throughout the book. While it's certainly fair to say that an introductory primer on why you should be a leftist for newly-politicized millennials isn't a must-read for everyone, the simple truth is that the vast majority of online leftists I know could learn a thing or two from this rudimentary synthesis of various left wing ideas into the seeds of a working, modern political ideology compatible with a uniquely Americanized, millennial left.

While no three hundred page comedy book written by five podcasters from Brooklyn is going to teach you everything there is to know about socialism and left wing ideology, there's something to be said for offering an accessible, entry-level alternative tailor-made for a target demographic already being heavily recruited by the fascists. As a starting point for exploring left wing political thought, you could do a lot worse than The Chapo Guide to Revolution and for a generation of kids who've mostly been encouraged to be passive accomplices to their own subjugation while blaming their misery on anyone even more powerless than they are, there is perhaps nothing more valuable than a condensed narrative that explores how to even think about another way to live.

Remarkably, this book finds a way to deliver on that monumental task while simultaneously failing to grasp one single relevant thing about the cherished American novel Moby Dick. Despite this infuriating literary myopia and insolence, this still might literally be the best book ever written for young American leftists who simply aren't going to spend ten years reading academic literature written by dead white guys from Germany and Russia.

- nina illingworth

Independent writer, critic and analyst with a left focus.

Please help me fight corporate censorship by sharing my articles with your friends online!

You can find my work at ninaillingworth.com, Can’t You Read, Media Madness and my Patreon Blog

Updates available on Twitter, Mastodon and Facebook.

Podcast at “No Fugazi” on Soundcloud.

Chat with fellow readers online at Anarcho Nina Writes on Discord!

#chapo trap house#book review#The Chapo Guide to Revolution#left wing politics#geopolitics#humor#leftism#introduction to leftism#Noam Chomsky#Howard Zinn#Thomas Frank#Cory Robin#culture war#politics#news#media#bloggers#savage burns

1 note

·

View note

Text

ON GIRLS, ADDICTION, AND GROWING UP by Catherine Pond

from Salmagundi, Summer 2017 [The TV Issue]

[photo by Annabel Mehran]

1

It was always winter that year, my first year in Brooklyn. Snow fell on the power-lines. A grey tree shivered outside my bedroom window. I had many friends but none that I could call.

I wanted to feel connected to the city the way other poets had, like Frank O’Hara in his famous poem “Steps”— “oh god it’s wonderful/ to get out of bed/ and drink too much coffee/ and smoke too many cigarettes/ and love you so much”— but I didn’t smoke, nor did I drink coffee. I barely made it out of bed some mornings. It felt more like I belonged in Muriel Rukeyser’s poem “Empire State Tower”:

The far lands melt to orange and to grey.

The city lies, quiet but for a rumor,

A single voice. People are guessed. We hazard

The world we know is there, below, unseen.

And in the street the many beautiful

Unstaring walk unwaiting the knives of doom…

2

It was 2012 and I was 21, living in East Williamsburg in a two-bedroom on Frost Street with my roommate Paul. Paul treated the few women in his life poorly. He despised his girlfriend (uncreative, immature, and blank were some of the adjectives he used) but no matter how many times he dumped her, she’d be back again the next week, sitting on our couch, Paul avoiding eye contact with me. For her birthday, he bought her a $200 steak at Peter Luger’s. “Maybe you actually like her,” I suggested one day, and he shrugged.

My romantic life was no less antagonistic. I often brought strangers home to have sex with, only to decide halfway through the act that I didn’t want them there, at which point I’d kick them out into the snow at some ungodly hour. Paul witnessed all of this but never brought it up, and I was grateful for that.

His great passion was television. He liked watching TV with his girlfriend; it was passive, I deduced, and allowed him to ignore her for long stretches of time. I didn’t understand television, and found it distracting and unsatisfying. His favorite show, still in its first season, was Lena Dunham’s cult hit Girls. Paul worked at a law firm and hated women, so this baffled me. When he turned it on, I’d note silently how obnoxious the girls were, then retreat to my bedroom to read Paul Celan.

3

One night, unable to sleep, I wandered into the living room and watched the entire first season of Girls. Still, I made it a point to actively hate the show. I told everyone I could: “The girls aren’t smart, or driven, and none of them have jobs. I can’t relate.” Occasionally episodes would be filmed on my block, in my coffee shop, in my neighborhood bar. I’d continue my criticism to whomever would listen: “I don’t recognize the world they live in.” Each month a check would arrive from my father to cover my rent. “They’re such spoiled brats,” I lamented to Paul.

4

Lena Dunham’s lime-green raincoat, dotted with pink flowers, falls open at the crotch. Her teeth are crooked; her lips bright red. It’s February 2017 and she’s posing on the cover of Nylon magazine, happy to capitalize on the character she’s developed: part-child, part-woman, all-provocation.

Fresh out of college in 2012 and riding the success of her movie Tiny Furniture, Dunham launched the pilot for her show Girls to much fanfare. She snagged the dream network (HBO), the dream co-producer (guru Judd Apatow), and the dream co-writers (Jenni Konner & Lesley Arfin among them).

Girls invited both acclaim and criticism from the get-go. Deemed “toxic” and “white girl feminism at its worst,” the show, set in contemporary Brooklyn, New York, features four protagonists: Hannah Horvath (Dunham), Jessa Johanson (Jemima Kirke), Shoshanna Shapiro (Zosia Mamet), and Marnie Michaels (Allison Williams).

Dunham is not the first to have the idea to follow four white girls around New York (see: Sex & the City) but she is the first to be held accountable for her show’s lack of diversity. In The Atlantic in 2013, Judy Berman spared no mercy: “Dunham continues to cast non-white actors only when race defines their character—which is to say, she still doesn’t get it.”

Lena Dunham, sometimes to her own detriment, is not concerned with political correctness (“I haven’t had an abortion but I wish I had,” she said recently in an interview). It is part of what makes the dialogue in her show so accurate and brightly humorous, and it is also part of what might be deemed problematic about her public and professional persona.

Is there an upside? This insistence on accountability has encouraged a long-overdue dialogue about diversity in television. And Dunham herself has learned a little something along the way: “When I wrote the pilot I was 23. Each character was an extension of me,” she told Nylon. “I wouldn’t do another show that starred four white girls,” she added.

5.

In the first season, Hannah (Dunham) has weird, sloppy sex with the overly aggressive Adam (Adam Driver); Jessa misses her own abortion appointment because she is getting drunk and having sex with a stranger in a bar; Shoshanna sets out to lose her virginity; and Marnie dumps her boyfriend of five years because he’s “too nice.” Later, Hannah takes acid in order to write a more interesting article, and Adam sends Hannah a picture of his dick wrapped in fur, then quickly texts, “That was for someone else.”

Despite this (or because of it) Hannah falls in love with Adam. Adam, for his part, seems drawn to Hannah, but disdains her, presumably because she evokes emotional reactions from him that he’s not fully comfortable feeling. In subsequent seasons, he dates ‘conventionally’ beautiful women, but finds himself defending Hannah, as in a scene where the stunning Shiri Appleby (whom Adam’s character degrades sexually, then dumps) bumps into Hannah and Adam at a coffee shop. Appleby sizes up Hannah’s body and exclaims, with lacerating cruelty, “That’s her?”

Late at night I considered my own body in the mirror. I had a proportional hourglass shape, with big boobs. But my body scared me. I preferred being thin and wearing baggie clothes, and it was my worst nightmare that anyone would learn I had large breasts.

I liked watching Hannah move through the world partially clothed, because I couldn’t, and her obliviousness, while sometimes problematic, seemed in this one sense a blessing.

6.

As the show progressed, I expected a personality transformation in the characters much like the one I expected in myself: I assumed Hannah would eventually mature, stop loving Adam, publish some writing, make a real career for herself. I thought Jessa would stop doing drugs, get her shit together, that Marnie would become less obnoxiously privileged and white, that Shoshanna would shed her Jewish-American Princess prissiness and learn to take care of herself. I hoped Adam would have a functioning relationship and make peace with his demons.

I was pissed when this didn’t happen. I was angry when Hannah went to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and then left because she couldn’t live anywhere but New York City, and didn’t understand how to take constructive criticism. Her writing was self-referential and sometimes straight-up bad. When I first watched Jessa attend AA meetings, I thought it was silly. Jessa’s stint in rehab seemed futile, and she picked up drinking soon after.

When, on my 23rd birthday, I broke down in front of my brother and admitted I needed help with my alcoholism, I didn’t make the correlation to Jessa’s character. I was proud and vocal when I stuck with AA for one month, and then two. And I was mortified and quiet when I stopped going and picked up drinking again, more heavily this time.

7

Around the time the fourth season came out, I fell in love with an artist named Charlie, who had dated a friend of mine years earlier. This friend was particularly possessive of him.

I made lists of all the reasons why my attraction to Charlie was bullshit, why it wouldn’t work, why I should avoid him. I assumed the attraction was based on some subconscious yearning, the fucked up parts of me attempting a ruinous self-sabotage. In a fury with myself, I used the money from a poetry prize to buy a ticket to France for a week. I decided in that time I would get over my bizarre crush and move on with my life.

I fell in love anyway. I lost my friend. And eight months later, I lost Charlie too.

8

In the fifth season of Girls, something surprising happens. Adam begins pursuing Jessa. As Hannah’s best friend, Jessa is furious to find herself falling for Adam as well. They date. Hannah finds out; Jessa begins to resent Adam.

“Y’know, people hate me,” Jessa confides to Adam. “I’m a hateable kind of person. I don’t know why, I can’t help it, maybe it’s because I have a big ass and good hair but I know, I know that I have principles and one thing I don’t do is steal people’s boyfriends. But you ruin that. Don’t you see that? We could die in the same bed and I will never forgive you.”

Adam, livid, replies: “Hannah is a lazy, entitled, manipulative, myopic narcissist who knows a lot less than she thinks she does. Why do you think I fucking hated you for so long? Because Hannah fucking hates you.”

Jessa whips her long blonde hair. “Welcome to having a friend,” she digs coolly, and Adam smashes a lamp against a wall.

9

As the other characters slide into caricature in the late seasons of the show, Adam seems actually to begin to mature, even playing guardian to his nephew after his unstable sister (the brilliant Gaby Hoffman) disappears. In this way he serves as Hannah’s foil, and his maturity highlights the ways in which Hannah fails to grow up with the world around her. Ironic that the character with the most interesting arc on Girls is a man.

10

I consoled myself a lot in my graduate school years by comparing myself to those I deemed less intelligent. I was convinced I could’ve written Girls, but better, and I protected myself this way, moving through the world with the conviction of my own gifts, and no awareness of the deep uncertainty I harbored inside. In the poems I wrote, I was at the mercy of everyone in the world who didn’t love me back.

Girls, for all its flaws, anticipated and mirrored my own life in ways I did not want to acknowledge. As I grew older and more forgiving of myself, I found myself more forgiving of the characters on the show, and their myriad missteps. Annoying, immature, adolescent—sure. But Lena Dunham had something I wanted: agency.

It’s this that I think we all work towards as we get older. Agency in our relationships, in our writing, in our careers, and in ourselves. I still want to be, as Hannah Horvath puts it in the pilot episode, “the voice of my generation. Or, you know, a generation.”

11

I haven’t spoken to Paul in years, but I think of him each time I watch Girls. How badly we behaved back then. How scared we were of being hurt.

I think of telling him how he saved my life with his dumb shows and giant flat-screen TV. How safe I felt, hearing him have hate-sex with his girlfriend through the wall. How I loved him, though I never said it. How I knew him by heart.

When I walked past the other day, Frost Street was quiet. Three trees struggled under ice.

I live on South 3rd now, a street with small fenced-in yards, and a happily neutral name.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

No Joke - Natasha Lennard

Image: Detail from Sacks (2007) by Sara Greenberger Rafferty. Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery.

A popular fiction has it that Socrates was convicted of his various charges by a slim majority of Athenian judges. Then, when it came to sentencing, the prosecutor proposed death. Socrates instead proposed that he receive free meals for life in the city’s sacred hearth. In response, more judges voted to sentence him to death for his impertinence than had voted to convict him in the first place. Though this isn’t true, it would have been ironic if it were.

Socrates, we might say, died from “irony poisoning.” Not the flesh-and-blood man Socrates, of course — he was probably killed for teaching and befriending deposed tyrants — but the Socrates we know from Plato and Xenophon’s hagiographic renderings, who was apparently sentenced to death by hemlock for using irony to reveal philosophical truths to young Athenian men.

If only the term irony poisoning were used that way, for cases in which poison is dispatched against irony. Instead, the term has emerged in social media parlance to signify that irony, cultivated online, is itself the poison. Mimetic of the process it ostensibly denotes, “irony poisoning” began somewhat as a joke. It’s well summed up, as these things often are, in an Urban Dictionary entry: “Irony poisoning is when one’s worldview/Weltanschauung/reality tunnel is so dominated by irony and detachment-based-comedy that the joke becomes real and you start to do things that are immoral or wrong from a place of deep nihilistic cynicism.” An extreme case of “irony poisoning” turns the online shitposter into the committed violent racist, willing to carry out bloody deeds offline.

The adoption of the term “irony poisoning” lets centrist liberals do what centrist liberals do best: call for civility, earnestness, and Truth as the antidote to violent extremism

Had “irony poisoning” remained imprecise, self-referential Twitter jargon, there would be no reason to take issue with it. But it’s now being used in earnest to describe a real and troubling condition. It has been enthusiastically picked up by publications like the Guardian, the Boston Globe, and the New York Times, which embraced it as a revelatory explanation for the rise and spread of fascist communities online and the offline violence they facilitate. “We are making a plea to scholars, readers and Silicon Valley elites,” the Times journalists wrote, without apparent irony, “take irony poisoning seriously.” And we should, but not for the reasons they adduce. Rather, the term’s adoption reveals the flawed way mainstream liberal analysis wants to see and interpret fascism. It lets centrist liberals do what centrist liberals do best: call for civility, earnestness, and Truth as the antidote to violent extremism.

That’s not to say that the pattern that the “irony poisoning” thesis points to is not gravely real. Online communities awash in euphemistic alt-right neo-Nazi references as well as explicit racial slurs and Hitler memes have produced violent actors in the physical world. Charlottesville was organized as a meat-space meetup of white supremacists who had found each other online and adopted a cartoonish lexicon by which to recognize each other (Pepes, symbols of Odinism and so on) and culminated in white supremacists beating a black man with metal poles, and a neo-Nazi mowing his Dodge Charger into a crowd of counter-protesters, killing one. Lane Davis, a prolific far-right troll on YouTube who called his parents “leftist pedophiles,” was thought to be nothing more than an outrage peddler until he stabbed his dad to death. The New York Times invoked irony poisoning in response to a case involving a German firefighter in a liberal town who bartered online in anti-refugee Facebook propaganda and Hitler jokes. He then attempted to set fire to a refugee group house.

These incidents of physical violence were no doubt stoked by a worldview shaped and encouraged in social media’s dark crevices, where race hate is often expressed and (further) normalized through memes and jokes. That is simply to say that our beliefs and behaviors are shaped and reinforced by the communities of which we are a part, and individual participation reinforces the group subjectivity in turn. Yet the framework of “irony poisoning” becomes dubious when applied as an actual explanation or pathology. By blaming irony as some sort of gateway drug to “real” race hate, it suggests that “real” far-right extremism develops through an extreme ironic detachment from reality and its moral standards. But in fact it is through routine attachment to networks in which white supremacy is an a priori moral norm in need of defense that fascist subjects are formed. Attachment, not detachment, is the problem.

For those of us interested in delivering effective blows to racist, fascistic formation, dismantling this liberal framework matters. I agree, we must take seriously the discursive violence expressed through veiled euphemisms and Pepe memes on Twitter, and the physical violence committed by those who speak that language. And we must take seriously that the flawed liberal response to these horrors is to blame irony.

The irony poisoning pathology belongs in the pantheon of bad explanations for the rise of fascism, which insist that a public is somehow unwittingly tricked into it: the idea that young, disaffected, white male social media users believe themselves to simply be playing a communal game of out-trolling each other but are in fact duped into a true fascistic frenzy. We see this framework play out in Jason Wilson’s piece on the phenomenon in the Guardian, in which he notes that seasoned neo-Nazis lure new recruits in with memes and racist jokes.

The media has picked up on contemporary white supremacist irony as if all previous iterations of fascism were somehow devoid of it. It’s perhaps calming to think that previous fascist constellations were transparent regimes of explicit race hate, easy to name and oppose. Nazi hats had skulls on them, for god’s sake, as British comedians David Mitchell and Robert Webb skewer in a sketch in which one Nazi asks another, “Hans, are we the baddies?” But historic fascist movements often bartered in irony and euphemism. Mussolini’s Black Shirts took up the slogan “Me Ne Frego,” which basically translates to “I don’t give a fuck” — a seeming cry of nihilistic detachment. But in context, the phrase meant “I don’t give a fuck if I die fighting for fascism.” The ironic expression was one of extreme attachment and sincere commitment, which makes individual nihilism possible. And as Malcolm Harris pointed out at in an interview with Elaine Parsons, author of Ku-Klux: The Birth of the Klan in Reconstruction, the Reconstruction Klan also weaponized “goofiness and so-called irony.” “All the Klannish affectations and accoutrements that seem so ridiculous today — the alliterative K’s, the costumes, the Magic: The Gathering titles like ‘Grand Wizard’ and ‘Exalted Cyclops’ — were ridiculous, and self-consciously so,” wrote Harris. “One of the functions of humor for the Klan, Parsons says, was to mark their transgressions as acceptable.” The funny white ghost costumes didn’t distract the American public into regarding Klan violence and the destruction of black life as acceptable and even desirable; rather it made it appear as normal and natural as laughter. The appeal to irony was not a trick, but an attempt to assert an already existing racist community, to invoke belonging and exclusion of the other.

In Germany in 1933, Wilhelm Reich, in analyzing how a society chooses fascism, rejected the all-too-easy notion of the duped masses. He insisted that we take seriously the fact that people, en masse, genuinely desired fascism. Ignorant masses weren’t manipulated into an authoritarian system they do not actually want. A Freudian acolyte, Reich posited a repressive hypothesis to account for fascist desire: The collective fascist subject was the result of societal sexual repression. His diagnosis was biologically essentialist and now appears wildly outdated, but his insistence on taking fascistic desire seriously remains all too lacking in today’s commentary on the rise of the far right.

This approach was further developed by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari to account for fascist desire formation as a productive force rather than a by-product of repression. “No, the masses were not innocent dupes; at a certain point, under a certain set of conditions, they wanted fascism,” they wrote. Deleuze and Guattari focused on micro-fascisms — quotidian, repressive operations of politics and power organized under capitalism and modernity. The individualized and detached self, the over-codings of family unit normativity, the authoritarian tendency of careerism and competition, the desire for hierarchy and power, the police — all among paranoiac sites of micro-fascism. These stem from the practices of authoritarianism and domination and exploitation that form us, reflecting how we are coded to desire the domination and oppression of the nameable “other,” and none of us are free of them. We can’t just “decide” our way out of them through a renewed commitment to earnestness.

But not everyone becomes a neo-Nazi. That requires a nurturing and constant reaffirmation of that fascistic desire to oppress and live in an oppressive world. And to be sure, that pernicious affirmation of white supremacy is not in short supply. Long before the birth of the internet, Deleuze and Guattari stressed interactive, habitual way that fascist desire is determined: “Desire is never an undifferentiated instinctual energy, but itself results from a highly developed, engineered setup rich in interactions.” Fascist subject formation relies on habit, and collective habit at that; social media platforms are an “engineered setup” that accommodate and incentivize these routines. Social media is literally designed to offer metrics of affirmation, which are easily adapted to incubating fascist desire.

The alt-right euphemistic symbols of racism are meant to confuse outsiders and affirm insiders who can feel a sense of belonging by being in the know. They are not attempts to trick the otherwise unsusceptible into racist thinking. Making racist jokes and references are among the habits that sustain and grow neo-fascist online communities, but it’s not the “irony” in them that affords a sense of permission and ushers someone toward white supremacist violence; it is the community that fosters such speech. The ability for angry, entitled people to find each other and support each other’s racial animosities, to speak freely and spread their message without negative consequences provides the conditions for far-right extremism to flourish, not the ambiguities of ironic discourse.

The suggestion that young social media users could somehow stumble into these online communities, believing them to be populated by ironic and nihilistic jokesters as opposed to “real” racists does not add up. Participation presumes understanding what Wittgenstein called a “form of life,” the necessary background context by which interactions and expressions are made possible. In these communities, emboldened white supremacy is the form of life, and participating in them presumes that understanding. Participants can’t be “poisoned” by what they already know.

Consider the “OK” hand sign adopted by the alt-right, Proud Boys, Identity Evropa and their fellow neo-Nazi travelers. The use of the hand sign began as a hoax on a 4chan alt-right discussion board. “Operation O-KKK” was announced “to convince people on Twitter that the ‘OK’ hand sign has been co-opted by neo-Nazis.” The same “meme magic” — to borrow shitposter parlance — was used to “trick” liberals and leftists into believing that milk was a white power symbol. Members of the alt-right swarmed actor Shia LaBeouf’s He Will Not Divide Us video-stream installation in New York, chugging cartons of milk. But there is nothing magical or alchemical in giving objects and words new significance through use. That just how meaning works. And it works even faster through social media’s metabolism, which establishes popular phrases and new references several times a day at minimum.

Buzzfeed’s Joe Bernstein, who first reported on the fight over the “OK” sign, wrote, “Where it gets really fuzzy … is trying to determine when and if these symbols cross over from ironic usage.” But it’s pretty clear that the “ironic” usage was poisoned with real racism from the moment groups defined by their white supremacy decide to collectively communicate and represent themselves with it. It’s not that irony poisoned the symbol or anyone using it; it’s the fact that neo-fascists used it to signal each other and develop the habit together, strengthening group subjectivity. Outside the language game of racism, it’s still just means “OK.” Inside, it betokens emboldened white supremacist fascism and bonds that sustain it. Those who claimed to be no more than pranksters were not drawing “us vs. them” lines arbitrarily; their targets were, from the jump, “libtards” and “social justice warriors” who dared care about misogyny and white supremacy.

Not every alt-right shitposter is going to take up physical violence against immigrants and non-white people. But the ones who do were not led to violence by a morality-blurring world of white supremacist humor but a consensus reality built around racism as a given, which is then nurtured, collectively and algorithmically.

If desiring fascism is not something that happens out of reason, we cannot break it with reason alone — this is the liberal mistake that manifests as calls to debate fascists in order to reveal the flaws in their thinking, as if fascist desire was simply something that dissolves into dust when faced with a counterargument or exposed for what it is.

Having a platform is what allows fascist communities to nurture fascist desire in participants. Thus anti-fascists seek to disrupt far-right rallies, deny opportunities to fascist speakers, and expose and shutter those online fascist communities to create unpleasant, if not intolerable, consequences for those indulging or exploring fascist desire. The point is to break the fascist habit by denying the spaces where it is fostered.

It would suit liberal and conservative disavowals of antifa tactics if irony poisoning were really the problem at hand. Condemning irony is the same as insisting that sunlight is the best disinfectant for fascism. As Vicky Osterweil noted in this publication, “feckless liberals abdicate power in the hopes that it will somehow ‘reveal’ the true nature of fascism — think of Democrats relying on Trump to finally demonstrate his unfitness to rule rather than organizing an actual opposition — fascism consolidates representations of that unfitness as opportunities to demonstrate loyalty and belonging.” Behind the so-called irony of Pepe and Kek, there is no pure discursive sphere to be revealed, where fascism and race hate have no place to hide. I suppose there’s some irony — a tired, well worn irony — in the media suggesting that the problem with racist fascism under Trump is that it’s all too obscure.

0 notes

Text

Ugly Crying in the Desert

When I was 13, the greatest pain I dealt with on a regular basis was the difference of treatment I got from people who assumed I thought I was better than them because I was a high performer. The gods saw fit to curse me with a high intelligence score, and some people appreciate that about me, but I hate it. It has brought me nothing but suffering.

I do well on non-metaphysical tests. You put a paper in front of me with little bubbles on it, and if you want it to be challenging you need it to be Non-self referential, and on a subject I don’t know much about to make me even break a sweat.

But if you put me in with 10 people, odds are that 9 of them are going to decide that they hate me because I am smart, and I do well, and I try hard, and I give a damn. It doesn’t win you friends. It doesn’t even get Praise. Even your bosses noses wrinkle up in distaste. People Openly Resent you. They Assume that you think you are better than them, even if that is not the case. Even when you want Nothing more than to be friends, and to just relax and be a part of a team. You get Rejected.

And even if they don’t actively Hate me, there’s a good portion of them that will just decide they don’t give a shit whether I live or die, and really, that’s as bad. Their indifference burns me, because I just want to be liked and respected. I want people to be open with me, and friendly, for no reason other than that they can.

Even at 35 it happens. I thought I was done with this bullshit. I thought once I was an adult and everyone around me was an adult, that this fucking shit would stop, but it was never about age. It was about maturity, and age is no fucking indicator....

If they had to climb inside this fucking meat suit I wear for thirty seconds, to see how it feels to be so fucking insecure all the time they would jump out basket-cases. And then they’d stare at me in horror at the brokenness that I live with. And I think they would Hate me Even More because of what I Do in Spite of the Shit that my own psyche continues to cough up.

If there was an invisible line that I could find, that I could toe, that would hide my stupidly perfectionist tendencies enough that people didn’t resent me, I don’t think I could do it. You cannot tell a Rooster not to Crow, or a Dog not to Bark. It makes me want to puke, to hide the giant fucking ball of Fire that I am.

All I have in my life that is real to me is my Honor. It is a thing no one else can see. I value it above all else, and No one else gives a shit.

I am not wired to be happy.

I don’t even know what it Looks like except in these beautiful little fleeting moments.

I just want to be Strong enough to Rise Above my Pain Every Time. I want to Be, unapologetically, the Biggest, Most Powerful Version of my Self. I want to Stop being Hurt by Haters. I want to walk With Strong People who Appreciate Me, and Who would Lift Me Up when I feel like I can’t take another Step. Or at least Won’t Push me down when I am trying to stand back up.

These are the Edges of Me. The Iron Anchors of my Fear. The raking claws of my pain. These are the teeth of my personal Hell, that gnash and strain against the meat hooks and chains at all times behind my closed lips. Demons Behind my decision not to speak.

I don’t owe you my pain. But you can deal with my tears. And you can fucking deal with my icy silence, because I will never let my demons poison you, or harm you in any way. The Cycle of Abuse ends with me in every Moment.

I keep asking people about what I should do for a job, and some of my friends, people who really care for me, ask me back, “Who are You?” They ask me what I Need. and What I Want...

And It’s all Internal. Everything I value about myself, everything that I feel is exceptional and rare, everything that makes me ME is private. Is connected to these people that live in my head and the love we share. the stories we make. The Mansions within me, their denizens, and the connection we share. What you see of me from the outside is a single expression of the collaborative efforts of all of us, working in tandem to make the world better. or do a good job, or help people, or rise up against bad shit.

I don’t have a Passion, that people keep telling me to chase, that is external to me. My greatest joy is in the smile in the eyes of men that only I will ever see. The triumphant twinkle on the teeth of the evil Amazon bitch in black armor that guards my heart. The gentle hands that Never fail to bring me back up, no matter how far from my truth I manage to fall in the face of the adversity of the hatred of others.

And no one gives a shit about this part of me. You can’t get paid for being bigger on the inside, unless you are Very Very Lucky, and become a Writer.

I can barely even show this sort of thing to the people I care for the most, Even them I suspect of just humoring me. Even them I suspect of not believing, not caring.

No Man is an Island... Except me. A Bitter, Sulking fucking Island full of people that don’t have their own bodies, and can’t fix me.

But Who do clear their throats, when I am feeling very sorry for myself, and tell me to do one better.

0 notes