#stanisława przybyszewska

Text

Illustrating the Danton Case + Thermidor

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Julius Caesar x The Danton Case Parallels to Celebrate the Ides of March, Frev Style 🔪🥳

Firstly, both Przybyszewska’s Danton Case and Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar are obviously (excellent!) tragedies that are set in a dying republic on the brink of collapse.

Here are some other interesting parallels I was able to trace:

1. Brutus and Robespierre:

Both of them are driven to execute an important figure even though they initially do not want to do it. They are both conflicted but feel like they have no other choice and have to commit the violent act for the good of the republic.

They are also arguably quite alike in terms of character: you have the „noble Brutus“ and then Robespierre, who is consistently referred to as „the Incorruptible“. Both are seen by others as selfless and committed to the good of the state (the people in the crowd very much emphasise this fact in both of the plays, I do have the receipts)

There is even the scene in which Brutus chastises Cassius for taking bribes, which plays into the idea of him as being (literally) “incorruptible” as well. And vice versa, traces of Brutus’ famed stoicism can then certainly be found in Maximilien.

2. Cassius and Saint-Just:

Both are characters who convince the protagonists (Brutus/Robespierre) to go along the violent act while not necessarily being portrayed as antagonists (at least Saint-Just definitely can't be seen as one in Przybyszewska’s play).

There are also parallels in the close relationship between Brutus and Cassius and Robespierre and Saint-Just, where they are very much portrayed as each other’s closest confidants. Of course, this idea can easily be pushed even further if one wishes to read between the lines. (There is no Camille Desmoulins in Shakespeare though)

3. Manipulating the Crowd:

I'm perhaps the most fascinated by how both Brutus and Mark Antony as well as Robespierre and Danton have the necessary rhetorical skills to manipulate the crowd of commoners (Robespierre being able to “play the crowd like an organ” very much came to my mind when I was reading Act 3 Scene 2 of the Shakespeare’s play).

Both Shakespeare and Przybyszewska portray “the court of public opinion” and how it can easily be manipulated - how opinions can be changed in the matter of minutes - in a way that is genuinely fascinating.

Specifically, the similarity between A3S2 in which people first listen to Brutus only to be immediately swayed by Mark Antony’s speech shortly after and the scene in the court in which Danton manipulates the crowd were in fact so similar in some respects that it was borderline uncanny.

The problem arises when looking for a mirror to Danton’s character in Shakespeare’s play.

4. The Case for Danton x Caesar:

It is Caesar who gets killed for being perceived as a danger to the republic

Both Caesar and Danton are portrayed as being very much beloved by the common people

Also, the idea of Danton being immortal is expressed at the end of Przybyszewka’s play, and while he does not come back literally as a ghost like Ceasar does, Robespierre nonetheless explains to Saint-Just that Danton’s spirit never truly dies.

5. The Case for Danton x Mark Antony:

If we see Danton and Robespierre as foils, Mark Antony makes more sense as a parallel to Danton (even though he does not die), since both Robespierre and Brutus as the classic ascetic/stoic archetype while Danton and Mark Antony’s are well-known for their appetite for drinking, women (or, you know, people, in the case of Mark Antony) , and the pleasures of life overall.

Both are also severely underestimated by their enemies at first, yet they prove to be quite cunning and are able to use their words skilfully to win over the public

Overall, reading both of the plays – especially the parts about manipulating the Roman public and the citizens of Paris just with the power of words – really makes me wonder if Przybyszewska read Shakespeare’s play and used it as a source of inspiration. It would make sense, especially given how the parallel between the French Republic and the Roman Republic was well-established long before her time (even, somewhat tragically, by the revolutionaries themselves).

I promise I think about Przybyszewska's and Shakespeare’s play and the Roman Republic along with the French Revolution a totally normal amount of time & that it definitely does not consume my every waking thought that should be very much going towards the exam preparation.

#ides of march#julius caesar#brutus#french revolution#maximilien robespierre#the danton case#stanisława przybyszewska#william shakespeare#mark antony#literature#classic literature#english literature#literary analysis#(attempted)#marcus junius brutus#georges jacques danton#antoine de saint-just#saint just#robespierre#frev#frev community#history#renaissance#tagamemnon#classics#roman republic#ancient rome#classic studies#you can tell this was not AI generated by the fact that it is so chaotic and at times barely coherent#but there is heart in it okay

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

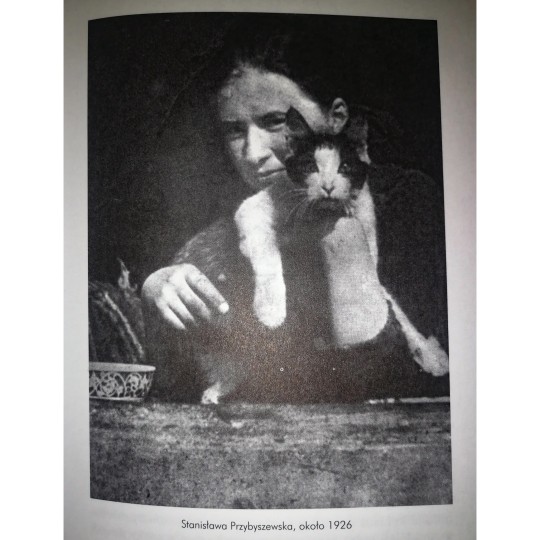

Stanisława Przybyszewska with a cat, 1926

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

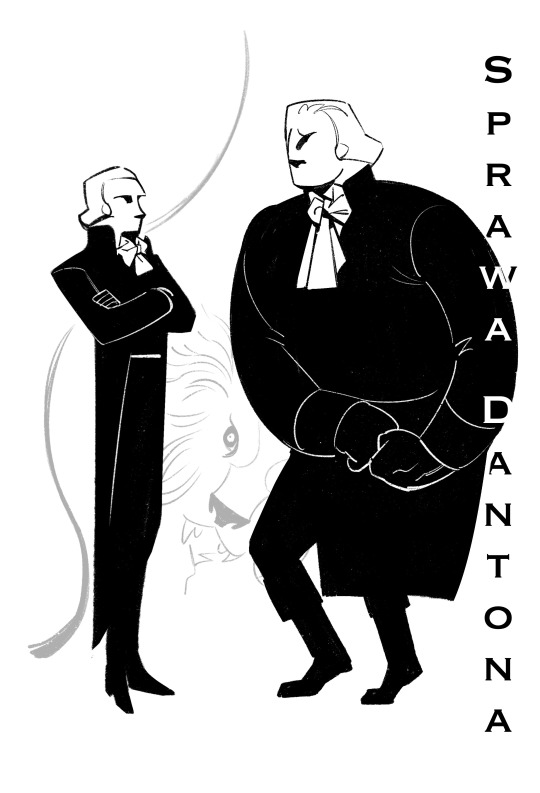

I was reading The Danton Case and wanna play with the steel-like (razor) shape concept a bit

end product

#The Danton Case#stanisława przybyszewska#french revolution#frev#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#art#my art

103 notes

·

View notes

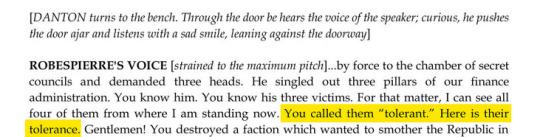

Text

#yes the indulgents were actually to his right. but.#the danton case#stanisława przybyszewska#french revolution#graphic design is my passion.#op#clearing the drafts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

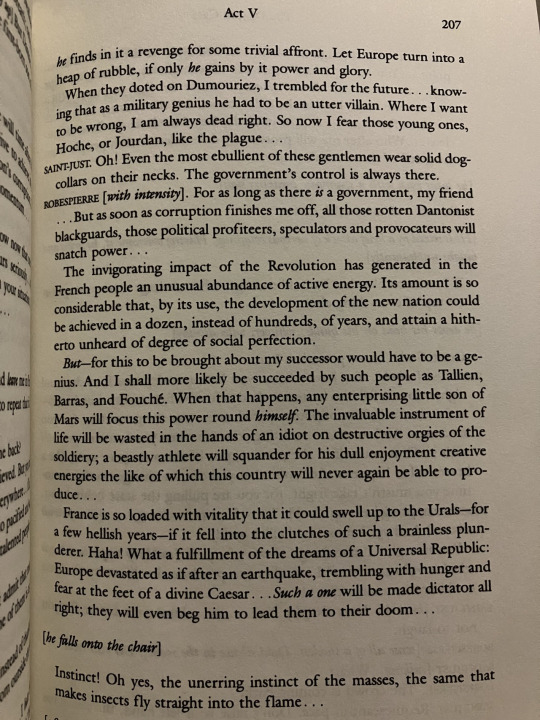

i cannot hold myself together anymore, friends, i have been living in the future that is controlled by the late danton.

(also saint-just really had to hear his prophet of a boyfriend tell him how difficult it will be without the two of them did he...)

#frev#french revolution#stanisława przybyszewska#the danton case#(;~;)#i should not have been rereading this on danton death day

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

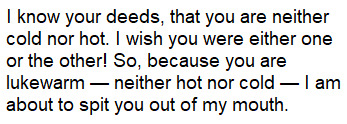

Ninety-three, Stanisława Przybyszewska, tr.@hhorror-vacuii | The Possessed: At Tikhon's, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, tr. S.S.Koteliansky & V. Woolf

#Josse contemplating ascetisim is not a virtue because it would be a crime to lead a sterile life like this. HELLO#Hello. HELLO!#virginia woolf translating dostoyevsky! a dream come true#the possessed#stanisława przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#fyodor dostoyevsky#fyodor dostoevsky#demons#the devils#biesy

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

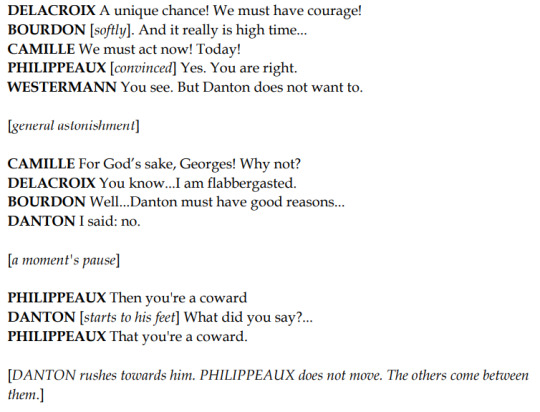

Philippeaux is the real chad here.

-from "The Danton Case" by Stanisława Przybyszewska

#the danton case#Stanisława Przybyszewska#Przybyszewska#frev#danton#philippeaux#desmoulins#l'affaire danton#french revolution

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

He never let us kiss his hand. And to be so familiar with him as to kiss his cheek – was altogether unimaginable. Besides, I doubt I would have ever dared to touch him. But I did manage to steal a pair of gloves, which retained the creases of his fingers and even a mysterious smell of perfumes. At night I sneaked out of bed and I buried myself in these gloves, reveling in this dying echo of an aroma, I couldn’t separate my lips off of them – night after night I would spend hours praying like this.

Ninety-Three, Stanisława Przybyszewska (transl. by @hhorror-vacuii)

My true God was my father. At communion it was my father I received, and not God. I closed my eyes and swallowed the white bread with blissful tremors. I embraced my father in holy communion. My exaltation fused into a semblance of holiness. I aspired to saintliness in order to conceal the secret love which I guarded so jealously in my diary. The voluptuous tears at night when I prayed to God, the joy without name when I stood in his presence, the inexplicable bliss at communion, because then I talked with my father and I kissed him.

Winter of Artifice, Anaïs Nin

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Danton (1983)

by Andrew Wajda

#1980s movies#french cinema#gerard depardieu#wojciech pszoniak#french revolution#stanisława przybyszewska#reign of terror#polish cinema#movie poster

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multirealities in Stanisława Przybyszewska’s plays

The most common critique of Przybyszewska I encounter everywhere is that she claimed her plays were a "historical chronicle" (an actual subtitle for The Danton Case), while being very obviously biased, belletrised, prejudiced etc., all in all not exactly the impartial retelling a chronicle is supposed to be. This critique permeats all that is written about her plays to the point when while I cannot exactly complain about the lack of resources focused on her (for such a niche personality she does have a dedicated group of scholars, fanalyzing her works and bringing to life all the forgotten bits from the Poznań archives), it seems to me way too much space is focused on these harsh views, and not enough left for enjoying what I consider to be a genius piece of literature.

When I say Przybyszewska was a genius, I don't only mean it in terms of brilliant literary prowess. She was actually a modern renaissance woman, talented in many fields, and if she constantly complained about not being good enough in any of them, it was only because she held herself to unbelievably high standards. Therefore it is simply stupid to assume she actually considered what she knew to be fictional - to be a chronicle. A title is one thing, believing it's true is another and I think the very least we could do in order to understand her and her works better, is to stop treating her like a child who did not pay attention in history clasess.

A small sidenote: Sandor Marai, my favourite Hungarian writer, has a knack for writing all love stories as if they were criminal cases, and the main character was conducting an investigation of sorts. Which makes it very fitting that in one of his most famous novels he introduces us to the concept of "reality versus truth". This seems counterintuitive, but I don't think it really is, and I also think this is something which should be more often applied to Przybyszewska. Too often she is being judged on the basis of having taken "too great a liberty" of assuming somebody's intentions and explanations. People act as if the very fact she wanted to give studying history a try already makes her a writer with an aspiration to be a historical writer. Now, I haven't read Albert Mathiez yet (but it's in my plans, as I don't think anybody can seriously discuss Przybyszewska without getting acquaintanced with Mathiez as well), but I doubt she wanted to write a history book, only better, only in form of a play, after studying Mathiez, much as she liked him.

All this points me to the direction of something I will call "A Prime Theory", and it's not very revolutionary, but it seems to be absolutely crucial to put it in place, because Przybyszewska is constantly being - unfairly - judged on the accordance and compatibility with the historical events, when it should not be the case. The foundation is this: the revolution Przybyszewska described is not The Great French Revolution, but The Great French Revolution'. According to mathematics for every Point, there is Point', identical to the first one but on a flipped side of the axis, so to say. I believe she has described something more akin to a parallel reality, with the general grasp on the events more or less the same that what we know from our history, but with occasional changes and differences. Therefore she did not describe the "reality" of the Revolution but the "truth" of it.

It is possible because the way Marai understood "truth" was that it was the essence, the gist of something much more than the actual chronology or honesty of a situation. The truth is much more personal and what we believe to be true, than what is factual and provable. The first and easier example would be the way she described Robespierre in regards to his physical traits. In every historical account I've read there is some thought dedicated to his fragile health and meagre posture, and Przybyszewska wholeheartedly disagrees, sprinkling small but firm descriptions that work to the contrary; any sign of illness or weakness is in her eyes onlyt emporal, besides, it's not really a weakness if it shows he has undergone (and proved succesful in the endeavour) such a multitude of obstacles any lesser man would have already given up. So even the "negative" traits she flips around so much they become "positive" in the end. They are literally being foils of their original meaning. The gnostic inspirations I have written about in the past have a lot to do with the general idea I'm describing now. The overall duality seems to be interwoven into the text, which is why I cannot treat it as if it were a singular thing. And I haven't even mentioned all the things she outright invents, like bragging about Robespierre's luscious hair (which are hidden under a wig anyway), or comparing him to a tiger or a cat or a dancer, or describing him with the help of a language which is highly metaphorical and imaginative. She is very visibly inventing Robespierre anew - why would she be accused of distorting a portrait of a historical figure, when it is clearly not THE historical figure she put on the stage?

It would also be unfair to judge her in terms of accuracy with history, because she was, after all, not a historian. I need people to understand (it seems funny to write about it, but it's been adressed so much by so many I think I really have to) she was not a bad historical writer, but a brilliant fictional writer. That her fiction resembles our reality so much is a point which still does not warrant reading her plays as historical plays in any way, shape or form. To be honest, I think any kind of factual reading of Przybyszewska's works is not a good idea, because she was so far removed from social and political life, she had so few friends or even just people she kept in contact with, I find it hard to believe she would even know how to describe actual, interpersonal relations, or political lobbies. This is more visible in her prose, but the relationships she's describing don't feel at all natural, and that is not because she was a bad writer - after all she a was a genius writer, with a talent few can match. She was innovative to the point of being incomprehensible by others, and the falsity and lack of natural feeling in the way she saw people is completely due to her lack of expierence of living in a society. This is what I find lacking in the discourse around Przybyszewska - not enough space is dedicated to underlining the fact her life was extraordinary in every aspect. Her life experience was something most people cannot even imagine, and especially this is not something we expect of a writer of her level.

I think I know where this dychotomy in perceiving her comes from: she used mechanical, detached language to describe the misery she lived in, and it seems to be a mascarade a lot of people still buys. It's the same things with the subtitle in TDC - we believe her at face value, completely disregarding the fact she was a writer, she was inventing fictional things all the time! It's like no one (not many people I've read anyway) is able to discern between what she put on display and what was really going on in her life or in her mind. I'm yet to see a good critical paper on her arguing that her perception of the world in all aspects must have been skewed because she was addicted to hard drugs. It's like no one notices it, nor the fact that she was allegedly sexually abused by her own father? There aren't that many more messed up situations than this one to find yourself in. The way she saw the world and described it in her works was surely affected by that, too. This is another argument in favour of truthfullness of these plays: she described what she felt was true, what she believed was true, what she imagined was true. It’s not a lie, if it doesn’t claim to be all encompassing turth, in short: it’s not a lie, because she said so (it only works in ficiton, but luckily for us, this is fiction!).

When I speak about "multi-realities" in her plays (a term I'm borrowing from Leon Chwistek, a painter and a mathematician living roughly in the same time as Przybyszewska, they had friends in common but I'm yet to discover if they knew each other personally) I mean, actually, that there is a multi-faceted way to look into her works. Yes, historical knowledge is good for analyzing the plays from one angle, but one mustn't stop at that. There are realities aplenty: reality of love, for one, is something she described very well. She also - mostly through Robespierre, partially through Billaud and Saint-Just - reaches out to the hypothetical future and describes possible, future realities. Her characters are not thethered to one spot, what she wrote encompasses more than what we see on the pages.

I think taking a step back when analyzing her works would go a long way. Not many people on here has read Ninety-Three, her short play, but this works as a good counterexample - in The Danton Case and Thermidor we get so hung up on the point that it surely must be reality, because all the characters are given the correct historical names etc. etc. we forget they are made up. In Ninety-Three, however, we don't encounter the same problem - I am positive there was never any princess Maud de la Meuge - and thus we are automatically able to read it as a piece of fiction.

Now that I think of it, this is another reason why it's easier to analyze in regards to fictionality her plays as adaptations, and not as the raw text. It's because the directors do a lot of additional fictionalizing for us, adding even more realitites to the already full melting pot of them. We need this abundance to see for ourselves neither of these plays are historical and it’s easier to come to this conclusion when the characters are very obviously wearing costumes, or the anachronism of the stage situation becomes too apparent.

#Stanisława Przybyszewska#stanislawa przybyszewska#the danton case#sprawa dantona#thermidor#ninety-three#dziewięćdziesiąty trzeci#literary analysis#leon chwistek#idk i said a lot of words while the idea is very simple

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making Przybyszewska's plays look like illustrated kid novels

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

A List of Relatable Things Stanisława Przybyszewska has done/written:

Studied philosophy at a university for one semester until "nervous exhaustion forced her to abandon her course"

Dated her letters by the French Revolutionary Calendar

Was known to often be humming La Marseillaise

Called Camille a twink in her play (okay, to be fair she used the word 'ephebe', but I'd argue that is as close to twink as you can get in the 1920s)

Worked at a leftist bookstore (and was subsequently arrested for it)

Took a stray cat from the street which at one point "was the only creature keeping her company"

Complained in at least two letters spanning over 3 paragraphs about a group of loud people playing football near her windows ("For the past forty-five minutes they have not been roaring, they have not been howling, they have been simply shrieking (...) like animals being slaughtered. Screams of that sort must be frightfully tiring for the vocal chords.")

When she wrote "I must write in order to be able to think. As a matter of fact, I am a remarkably unthinking person. Well, of course, that holds true too when I'm talking. But if I don't have either paper, or a human ear to listen to me, then I'm no more of a philosopher than a cat is."

1 + 8 - since I study philosophy at uni & am currently working on my thesis, these felt particularly relatable. I'm not more of a philosopher than a cat is definitely hits. Kind of want to put it in the preface.

2 + 3 are things I may have done myself before (okay, not letters but a diary, but it counts, right?)

7 - as someone who struggles with misophonia, I felt s e e n.

4- I'm sorry guys, I had to. But as someone who frequently asks herself "Are you really calling 30-somethings who have been dead for more than 200 hundred years twinks?", this felt like a vindication of sorts.

Also- I feel kind of conflicted about making this types of Tumblr posts about her since her work is really profound and serious and I have a sneaking suspicion she would have not appreciate them. At the same time, she has been living in my mind rent-free for the past week and this is a way to cope I guess?

SOURCES:

1. A LIFE OF SOLITUDE: STANISŁAWA PRZYBYSZEWSKA

Author(s): JADWIGA KOSICKA and DANIEL C. GEROULD

Source: The Polish Review , 1984, Vol. 29, No. 1/2 (1984), pp. 47-69

2. BBC Reith Lecture Three: Silence Grips the Town. Dame Hilary Mantel, 2017

3. Stanisława Przybyszewska: A Brilliant Playwright Preoccupied With Revolution. Alexis Angulo. Retrieved from: https://culture.pl/en/article/stanislawa-przybyszewska-a-brilliant-playwright-preoccupied-with-revolution

4. Przybyszewska, Stanisława. 1930. The Danton Case.

#french revolution#frev#frev community#stanisława przybyszewska#przybyszewska#the danton case#frev memes#history#literature#also go read the articles they are excellent#but obviously incredibly sad#camille desmoulins#20th century literature#misophonia#1700s#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#academia#it actually took effort not to put “daddy issues” on there#I guess it's now in the tags#oops#hall of fame

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have the desire to beat into the mushy interior of the public brain a new image of the Revolution, an image which would not do a terrible wrong to a number of its heroes, and of human nature in general (represented by the rare golden grains that are none the less contained within it); but I know only too well that I won't attain this goal. For one hundred and thirty-five years they have had an image of the Revolution that is incomparably simpler and much more comfortable, from both intellectual and a moral point of view. That's something that won't be given up so readily.

Stanisława Przybyszewska, Letter to Helena Barlińska, Gdańsk 19 March 1929,

from: Jadwiga Kosicka and Daniel Gerould, A Life of Solitude

8 notes

·

View notes

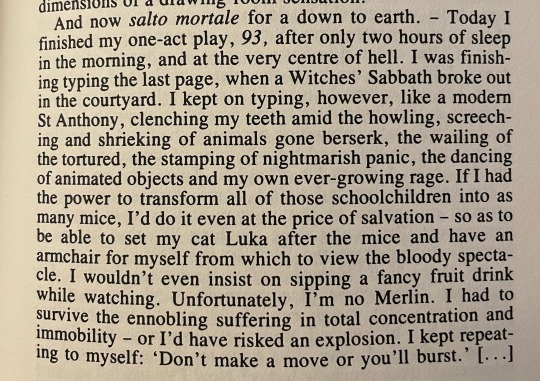

Text

Stanisława Przybyszewska on disruptive schoolchildren:

From a letter to her father, May 8, 1927. Published in A Life of Solitude, 1989

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

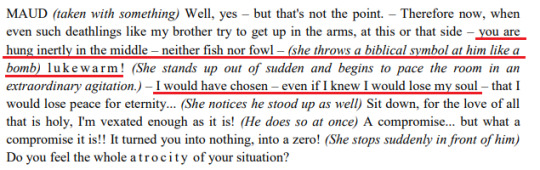

Revelation 3, 14-15 | The Possessed, Fyodor Dostoevsky | Ninety-Three, Stanisława Przybyszewska

#stanisława przybyszewska#fyodor dostoevsky#at first reading i thought the play was about Maud#at second - Josse#now I think it was Michot after all and it was so PAINFULLY obvious from the begginning. i'm just blind#i sort of need to write a paper comparing Michot and Tikhon#webweaving

32 notes

·

View notes