#speaking french means i could also travel to the continent of africa and not have to learn 7 dialets of arabic that are apparently not

Text

girls, be honest. should i learn french just to watch kirikou et la sorcière? i love a good childrens cartoon. and i have 7 years of god awful public school education so its deffy the language i have the most experience with after english.

#speaking french means i could also travel to the continent of africa and not have to learn 7 dialets of arabic that are apparently not#mutually intelligible at all#and i could get a stupid job with my stupid federal government#my french accent is probably way better than my german one and defo defo better than my japanese or korean#but id rather learn spanish or portuguese if im learning a romance language!! they r so much cooler -_-#i want to have general proficiency in a language other than english sooo bad and i know french would be my quickest bet#like i bet in 12 months of picking french back up i could probably hold a conversation about general things#ive been going at japanese for 2 months now and i know the kanas and how to tell time#and i dont even know how to write the kanji for that#i think it would take at least 2 or 3 years before i would feel confident enough to speak to an actual japanese person ;_;#grrrr i totally have the free time to do two at once but like. hmpj#im stupid is all and mandatory french made learning the language quite tedious :/ when i think about all the former french colonies tho#thats a lot of people i could communicate with just by knowing french#and again my stupid country is bilingual so i do come across french speakers from time to time#tho most french speakers including immigrants end up in quebec#so i actually deal with way more Spanish speakers#and more arabic speakers#luchy me they speak english also tho so we can understand at least.#god being monolingual is a handicap

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How a Nigerian Prince Taught Me How to Behave as a Yoruba Princess ~KyleeliseTHT

Yoruba, a west African language spoken largely in Nigeria and Benin, is a beautiful tonal speak. I learned the melodic dialect while in grad school at Yale. My Yoruba professor and dear big-brother-friend was Frank Arasanyin.

A true linguist, Frank demanded perfection in every sound and tone spoken whether in class, passing on the city streets of New Haven, or in his home kitchen. From me, several years his junior but close enough to be informal, Frank also had this thing about my becoming regal.

“I am the son of a king. You are a princess,” he’d say. “You must at all times behave as one.”

Frank’s declaration didn’t mean that I was his princess but a princess in my own right. In fact, very early on in my princess-ness, he gave me the name, Ayo. Ayo means joy in Yoruba.

So emphatic that I transmute myself in conduct and spirit, Frank refused to call me by any other name. Quietly, I became Princess Ayo, even within my own sense of self.

The name “Ayo” is fitting. I am 24-percent Nigerian.

And, when privileged to be in the company of several great African writers, scholars, other creatives and thinkers, I would proudly include “I am Ayo” in my introduction. More than once, I was corrected: “You are Princess Ayo.” How did they know?

The importance of my Nigerian-Yoruba name didn’t always impress. Once I dropped it on the writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o when I took his class only to receive a lukewarm nod. But, hey, he’s Kenyan.

On my first visit to the African continent, I was not yet “Ayo” or “Princess Ayo.” I was “Kyleelise,” having been given the right to use my full name by my creative-mom, the principal dancer and second artistic director of the Alvin Ailey Company, Ms. Judith Jamison.

After a lifetime of “Lisa”, “Elise”, “Kyle”, and “Elisa”, it was Judy who decided that people ought to speak my full name without exception. Like when “the mother of modern African Literature,” Flora Nwapa, playwright and poet J.P. (John Pepper) Clark and so many others confirmed that I was, indeed, Ayo, I believed that I could expect people to navigate the difficulties of my name, Kyleelise, when the formidable Ms. Lena Horne—after Judy’s insistence--said to me, “If I have to call you Kyleelise, everyone else has to call you Kyleelise. No more nicknames!”

That day I descended from the plane on my first flight in north Africa, I would have cherished my own introduction: “I am Kyleelise and I am Princess Ayo. So pleased, I am, to meet you.”

I spent a lot of time in Frank’s kitchen, where he tried unsuccessfully, like so many others, to teach me to cook.

Arroz con pollo, fried plantains, bistec encebollado, mojo pork, alubias con arroz, and yucca cake—these are the only dishes I can cook competently. Ask my children! For the very last time there was an expectation that I make a meal for my family, I was slicing plantains when my children lined up at the counter and demanded that I surrender cooking and my limited menu of Latin meals—FOREVER!

Back in grad school, when Frank hosted, he gladly took on all the cooking, while other classmates sipped wine and chatted, while my daughter, Toccarra, moved about his place doing whatever curious, well-behaved children do.

Notice that I was not among the loungers? Nope. In exchange for not being a teachable culinarian, I got stuck in the kitchen doing all manner of lower-skilled jobs, like cleaning, setting the table, cutting vegetables and such. And, there was “princess” training.

Frank taught me how to buy and sell stocks and bonds, purchase a car, invest in real estate, how to best trade international currencies when traveling, when and where speaking French or Spanish is more advantageous when abroad but not in Europe. “Never let your passport expire,” he’d say. Sorry Frank.

The man was relentless! And, because he was just over a decade older, he used his elder-powers to be darn-right bossy when it came to my mastering these intricacies of princess etiquette.

Sometimes, I felt Frank just took the whole “I am the son of a king” and “You are a princess” thing too far.

But not quite.

I found my notes from Frank’s Yoruba class, recently. That time in his presence, listening to his lectures in class and the off-campus lessons about the conduct of a princess, seemed as if it would last forever. Ya know, “on and on ‘til the break of dawn” plus some.

Time passes. We all move on.

Frank’s influence on my life is palpable. We all remember him, fondly, my daughter and the guy I’d marry. Holding his notes, I thought that it would be a good time to look him up and give an update on how his little-sister princess turned out.

Timing is everything. Unfortunately, Frank’s time ended on February 10, 2012. I was six years and nine months late. I learned this when his obituary turned up in my online search.

The narrative of his life after Yale was revealing. I knew he married. His two beautiful, nearly-grown children were a pleasant surprise. And that’s not all—Turns out Frank really was the son of a king!

“Frank Olaoba Arasanyin was born October 10, 1954, at Afa, Okeagbe, Ondo State, Nigeria, to the Royal family of His Highness, the late Ezekiel O. Arasanyin and Princess Salamotu Arasanyin (nee Alilu).”

Oh, my. I wonder if his personal truth confirms that I really am a princess? Nah. But I have learned to play one in real life. Thank you, Frank. ~KyleeliseTHT

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview Allison Gibson

1. Okay, Miss Allison, what was the specific incident that got you to this interview?

I was scrolling through Facebook and noticed you were looking to interview women who have traveled solo before.

2. What has earned you the right to be an authority on this topic?

I started traveling quite young, but always with friends. It took me years to finally leap and take a true solo trip, which was life-changing. I want more women to gain the confidence and self-awareness that comes with traveling solo.

3. What is your brand, your topic exactly about?

I hope to inspire others to travel again once this global pandemic ends. On Ally Travels, I’ll share valuable tips, explore other cultures, and push my boundaries in far-off places. And, most shockingly, I’ll do all of this while living out of two suitcases!

4. Why is it important?

Travel is essential for the soul. I always learn so much about myself on these trips. I find every trip opens me up as a person and broadens my perception of the world. I think solo travel is an especially important experience to have. It really builds your confidence in having to rely only on yourself.

5. Now that I know what it is, now that I know why it’s important and relevant, how are you implementing this on your travels? I mean like, is there a process that you follow when traveling?

When traveling I like to research the location and come up with a few things that I’d love to do. I hate feeling too scheduled, so I choose a loose plan, then just see where the day takes me.

I try to say yes to as many things as safely possible. Journaling is something I also love to do. It’s so interesting to look back a year later and read it. I always realize how much personal growth I’ve had since the last entry.

Also, taking photos!

Solo travelers: Take as many selfies and photos as you can. I know it feels stupid, but trust me you’ll be so happy you have them later. Besides, you’ll likely never see these people again, so who cares if they judge you?

To avoid selfies, I try to spot another person trying to take a cute photo and offer to take a photo if they’ll take one of me. I’ve gotten such amazing photos this way (sometimes it takes a few tries).

6. What if people took advantage of your tips and steps you are providing? What will happen, how will their travels change?

They will likely have less stress, and make memories that will last a lifetime.

7. Now we would like to get just some general information about you and your travels:

(if not answered before) – When did you start traveling?

My first international trip was 5. My family moved to the island of Saba for 6 months. Then I to a summer acting program at Trinity College in Dublin for a month in high school. My first truly solo trip wasn’t until two years ago.

– Do you remember how you felt when you traveled alone for the first time?

It felt so freeing going off on an adventure. I love the anticipation of what lies ahead, anything could happen.

Personally, I had a really hard time dining alone before my first solo trip. I had so much anxiety about having to eat out alone so much on this trip. It always felt so awkward to me to be sitting there quietly playing on my phone or reading. Or doing the alternative of sitting silently staring into space.

That was a big leap for me. Being forced to face yourself can be daunting. We are always expected to be moving, to be doing something. We’re so busy that we rarely give ourselves time to reconnect with ourselves.

I walked away from that trip knowing more about myself and needs. For the first time in a long time, I felt really grounded and confident in myself.

– How did you, or do you deal with fears?

I remind myself that the reward is greater than the risk in most cases. Plus, the adrenaline feels so wonderful once you’re done facing down your fear.

In the dining alone case, I’d treat myself to a really delicious cocktail or glass of wine. Then order anything my heart desires on the menu with absolutely no guilt. I made it like a date night out with myself.

– Is there a place where you have been and you would definitely not recommend it for women on their own and why?

I’ve had really positive experiences on all my solo trips. While in Istanbul visiting a friend, he was very insistent that I shouldn’t go off alone. Personally, I felt safe but the fact he’s local and didn’t want me wandering off alone concerned me. I’d probably just try to be extra aware of my surroundings in Istanbul if I went back solo.

– Do you still have this excitement, when you go for a trip?

The anticipation and butterflies are my favorite part of the start of a trip. I love not knowing what adventures are ahead. I love how I feel traveling, there’s no greater high.

– What are your top 5 destinations and why?

Cote d’Azur: The South of France is stunning! I’ve been twice now, and I’m dying to go back again. There are a ton of tiny little beach towns to explore. It’s absolutely magical, and easily one of the most beautiful places that I’ve been to.

London: I am a big theater fan, so I love going to London to see shows. They also have an incredible restaurant scene. It’s great wandering around London, I find it to be really charming.

New York: New York is my home, and one of the greatest cities in the world. Plus, I can’t get enough of the theater scene there. The city has a really unique energy. There’s always something new to see. You’ll never be bored.

Nairobi: I haven’t been yet, but I’m dying to go. I know it’s a bit touristy now but I’d love to stay at Giraffe Manor. Between the giraffe encounters and elephant adoption, it’s every animal lovers’ dream. Africa itself is a continent that I still need to get to. I can’t wait to get over there.

Australia: This is another spot that I need to check off my list. Hopefully, I’ll be there with my boyfriend later this year (he’s Australian). I’m really excited to explore with him and especially thrilled about meeting kangaroos and koalas. Oh, and TimTams…they are these really delicious Australian biscuits covered in chocolate. My boyfriend has me addicted to them!

– The funniest story that happened to you when traveling?

While in St. Remy, France, I made friends with a horse that was tied up near the town. When the owner came back, he let me ride the horse all the way into the center of town to my dinner reservation with my dad. I should mention nobody else in this town had horses. It was an unusual sight.

We ended up parking the horse next to the outdoor section of the restaurant and all shared a few glasses of rose together. I should mention this man didn’t speak any English. My dad speaks no French, and I only have a limited high school level of French. There was a lot of miming and stifled laughter!

8. Call to action – what do you want people to do?

Take a leap, book that trip you’ve always dreamed of going on. I promise you’ll return feeling like a new person. Travel always changes you for the best.

Socials:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/allytravelsofficial/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AllyTravelsOfficial/?eid=ARDIJxvJiIl8YgqIOgwt-wZDAfOvsrPsiTBAsUEKGKNJKLaOG1uwOvlfT-PRXMEi7JhrO-9tfv1VlgVG

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/AllyTravelsOfficial/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/travels_ally

Free your travels, be a Travelita! #travelita #iamatravelita

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2Svqhbc

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

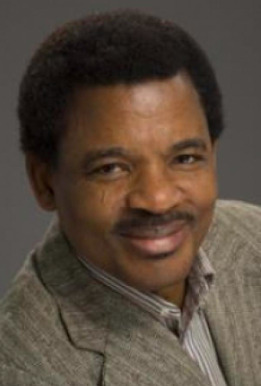

Interview with an Expert: Dr. Funso Afolayan

Faculty page: https://cola.unh.edu/person/funso-afolayan

Intro: Dr. Afolayan teaches African history, world history, international affairs, and history of world religion at the University of New Hampshire in Durham, NH. He has received his B.A. in History Teacher Education, his M.A. in International Relations & Affairs, and his Ph.D. in African Studies from Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria. His main research focuses are Nigeria and South Africa, and he has released several publications including (but not limited to) Culture & Customs of South Africa (2004), “African Historiography” (2005), “Religion and Politics in Colonial Nigeria: the Life and Career of Sir Walter Miller” (2009), and Historiography and Methods of African History(2012). In this interview, Dr. Afolayan helps shed light on the effects of colonialism on the region, the pan-Africanist movement and some of its heroes, and how populism stems from a variety of issues that have plagued South Africa much longer than an outsider might guess. Canovan wrote that populists see themselves as common democrats voicing popular opinions and grievances that are systematically ignored, and Dr. Afolayan is able to contextualize what many of those grievances are in the Rainbow Nation.

Transcription:

Funso Afolayan is my name. I teach African history, world history, international affairs, and history of world religion at the University of New Hampshire. My areas of research is Africa, more specifically Nigeria and South Africa.

Colonialism has heavily impacted this region. In South Africa specifically, how do you think this legacy continues to impact culture and politics?

Colonialism changed in very fundamental ways the history and culture of African society. The Europeans began to arrive in Africa in the European age of exploration at the beginning of the 15thcentury. In South Africa specifically the first settlement was in 1652 by the Dutch, who planted it for what they called a “replenishing station”, which means a temporary post, for Europeans to sail to and make provision for European merchant ships who are coming from Europe and going to the far east. It was meant to be a temporary settlement, but eventually it became permanent as more Europeans arrived, and as they needed to farm they got more land, established farms, and became pastoralist. But effective European conquest of the African continent did not take place until the end of the 19thcentury, but South Africa was one of the areas of Africa that came under colonialism early. So from 1652 Europeans basically began the process of the European colonization of Southern Africa. How did it change Africa? Well it brought a new culture to the continent, it brought European culture to the continent, the language changed, the religion changed, the politics changed. People in South Africa speak Dutch, they speak Afrikaner, which was a new language that was a kind of African-Dutch creole language. You have Indians also in South Africa, you have people from China, but it is the European presence that predominated, so today English is the lingua franca of South Africa, as it is in many parts of Africa with French, Portuguese, and Spanish to a great extent. So that was a change. European presence also brought Christianity, but colonialism helped it become further consolidated, so it changed religion, it changed the traditions, it changed the ways of life. Colonialism also brought the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which had far-reaching consequences. It took millions from Africa across the Atlantic to the New World, so it created the biggest African diaspora in America, some went to Europe but they predominantly came to the Americas, so then at the end of the 19thcentury Africa was conquered. Attempts made before the 19thcentury to conquer Africa failed because African societies were well developed enough to counter and resist European conquest. But European industrialization gave Europe the tools, so Europeans came back and the end of the 19thcentury and imposed their control of Africa, so African society changed. Colonialism brought economic transformation. There were positives like the development of railway, and the beauty of ports, western education, all those things came with colonialism. But it also led to the decline in indigenous culture, the abandonment of indigenous industry and indigenous traditions. What you would call the eclipse of African religion with the new religion that came from Europe, Christianity mostly, which also spread across the continent. Now we have a political system in Africa that is quite different from the indigenous system, modeled after the system of the former colonial masters, so these are major changes. Africa became Westernized, let me put it that way. Modernized, but also in the Western fashion.

You authored Culture and Customs of South Africa in 2004, and you discuss the competing European and African angles that face the nation in a variety of ways. How would you describe that relationship?

You know, South Africa is often described as the “Rainbow Nation”. As I said part of what Mandela did was to try to sustain that image. Rainbow of course means of many colors. You have the black majority, but you also have the whites, and then you have the Indians, who would be kind of like red, and you have the Chinese, who would probably be the same category, and you have a group called the colored, which is the byproduct of racial intermarriages. The colored population actually constitutes the biggest group in the Cape Province of South Africa. One of our popular talk show hosts here in the US, Trevor Noah, is a colored from South Africa. So you have that combination of a “rainbow nation”. Yeah, there is competition between these different groups because South African history is constituted of that history. The white group came in 1652 and literally took over the country, they subjugated it, they dispossessed the original population of their land, their power, their position, and ruled the country basically until 1994. So that’s like almost 300-400 years of domination. 1994 brought the transition, but even in the White you have the British, and the descendants of the Dutch who are known as “Afrikaners”, and they competed with each other. The Dutch are the people who established apartheid in 1948, but all the white people benefitted from it. They didn’t establish it just as an Afrikaner thing, but as white domination. Their nationalism was the extreme nationalism that especially established it. South Africa’s history is the negotiation between these different groups to maintain balance and harmony. And the biggest challenge they face today is power is now in the hands of the black majority, but the white minority still has economic power. They control the banks, the corporations, the mines. They also control much of the land. So these are issues that are creating tension, the people that have political power do not have economic power. You could say one balances the other, but it also creates resentment and disenchantment between the two groups. South Africa’s history is how do you balance these two things out, and how do you not just share power but also economic resources. So that is the challenge, and that is what the country has been doing. The time of transition in 1994 is balancing these two groups together. I think they have been generally effective in doing it, and I also think a number of black people have been economically empowered. There’s a program called “BEE”, Black Economic Empowerment, in which the government program is directed towards empowering young black entrepreneurs, spreading education. One of the watchwords of Mandela was education should become the priority of the South African government. When people get educated, they can break out of their oppression. They are not going to move forward like “Okay, let’s take the wealth of the white people and distribute it to the black”. That’s not going to work. By the time you have distributed, they will finish spending it, and then there is no wealth to distribute. But if give them education, education will become the instrument of their liberation. It will get them jobs, they will be able to start businesses, they will be able to penetrate into all the different places. So this is the promise South Africa is making. Of course there are many people who are not satisfied with that, who want a more radicalized way of redistributing wealth, but it is very difficult in the modern world to do that. So I think this balance between the two that sustains South Africa, I think they have done an incredibly marvelous job doing it. Most of the time the rhetoric does not give the impression that they have done that, but it is not rhetoric but reality on the ground that really matters.

In your book you also characterize South Africa as the economic powerhouse of the region. Can you explain that role?

First of all, for a long time South Africa’s GDP was the biggest in Africa. It has only been a year or two since it was surpassed by Nigeria, to my own surprise I didn’t think Nigeria could surpass it, but I almost think it is a temporary surpassing because South Africa has tremendous potential. Nigeria has oil, that a very limited resource. South Africa has all kinds of things. It is the world’s biggest producer and exporter of gold and diamonds, a wide variety. I mean 70% of the world’s diamonds come from South Africa. So those are huge things, and it also has a wide variety of other resources in the country. It is also the most industrialized country on the entire continent of Africa, South or North or East. It has well-developed infrastructure, more than any country on the continent, so it’s a powerhouse. And also it is the major source of economic sustenance for many of the countries in that sub region. Thousands of migrant laborers travel from neighboring countries to South Africa every year for economic sustenance, and the economy of several nations in that region from Lesotho, Botswana, Swaziland, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe, the economies of these countries are intermingled with South Africa. Any time there is crisis, Zimbabwe has been in trouble for many years now because of the bad rule of Mugabe, almost a third of the people of Zimbabwe are in South Africa. They are migrating there just like people are trying to come from South America, and they are all in because it is not like you keep people away. People go in and go out, the border is kind of loose. They also need the laborers and workers, so people go in and thousands of people from there are in South Africa, despite all the xenophobic attacks on everything. So South Africa’s economy is connected, it controls and influences the economy of that region. So it is in South Africa’s interest as well as in the interest of the people of that region. You have the South African Development Corporation, which was a deliberate attempt in Southern Africa to integrate all the countries of that region into a common economic union. South Africa is the major promoter of this corporation, almost comparative to what you call NAFTA here. So it has enormous resources, especially compared to other parts of Africa, so it is an economic powerhouse as it is the most centralized in many ways now that apartheid has ended. Before apartheid had it isolated, and with the end of apartheid it actually opened up the rest of Africa to South African investment. So South African business are all over the continent. The biggest Internet company in Africa today is owned by South Africa, it’s called MTN. That’s the biggest phone company in the whole place, and South African Airway are also the biggest on the continent, it flies to many parts of the continent. For a while South African Airway actually took over Nigerian airways, and they are doing the same thing in East Africa in many places. So many South African businesses that were not able to go anywhere before 1994, after apartheid basically opened up the African continent to South Africa in a very powerful way. And they are taking advantage of that everywhere. In fact many white farmers who had struggled in South Africa went to other African countries to go and get land and farm in those places. Some of them were actually invited to come and farm, and produce food in other countries.

Among others, Julius Malema has credited the pan-Africanist movement as a source for his ideas and policies of the EFF. Can you explain the pan-Africanist movement and ideology?

The word pan means “all encompassing” Africa. This was a movement that developed maybe late in the 19thcentury but it became popular mostly in the 20thcentury. It was a movement by Africans, in Africa and in the diaspora, to bring about the unity of all people of African descent from all over the world to come together, work together, in order to fight for objectives that were considered to be of common interest to all African people everywhere. At the center of it were educated African elites in Africa who are the byproduct of colonialism, and elites among African people in the new world, in America, in the Caribbean, who became prominent in an attempt to bring together African people to fight causes that are of interest to Africans. Liberation from colonial rule in Africa, civil rights achievements in the Americas, promotion of African culture, economic, and political independence. An autonomy everywhere in the world. Among the leaders of this movement you have major “American is African-American” people like Booker T. Washington, who was a notable figure in the black community in the Americas in the late 19thcentury to part of the 20thcentury, who advocated that black people should use self help and equal education to liberate themselves. Or W.E.B. Dubois who said the elite in the society, the African-American elites should be at the forefront of liberation in the new world. Or people like Marcus Garvey from Jamaica, who was very prominent and probably the most influential in Africa because of his what you would almost call nationalistic commitment and radicalism to pan-Africanism. He was able to raise what you would call a one million-man army, that we bring Africans together, liberate Africa, and come to the new world and create civil rights and freedom for black people. So these were the people that lead the movement. Of course in Africa there were leaders of pan-Africanism like Kwame Nkrumah who eventually became the first president of Ghana Leopold Senghor who you would say became the chief exponent of a version of pan-Africanism known as negritude. Negritude is an intellectual movement among African elite of French Africa who essentially saw colonialism of the French, which was based on assimilation in which the elite would have to become French, you would be treated well and respected. They saw it as a kind of alienation from French culture, so they then decided they could be French, but at the same time be African. And this ideological movement associated with “I am black and I am proud” became part of that movement in which they began to celebrate in every way and express their pride in their African culture, African ancestry, and African connection. So this was a very important movement, but I think the major element is the focus on unity. Brining African people from all over the world to form a united front and to fight for causes that are of major interest to Africa; in Africa which was colonial liberation and development, and in the new world civil rights. The ultimate end of it was the establishment of the Organization of African Unity by independent African states in the early 60s. The Organization of African Unity eventually became the African Union, which is almost like the new United Nations but it is focused on Africa.

Julius Malema has spoken very highly of Thomas Sankara, seeing him as an inspiration and aligning the EFF with symbols and policies that honor him. How would you characterize Thomas Sankara as a figure in the region?

He became the leader of Upper Volta, in 1983 he came to power. This was in West Africa, and I still remember very well the story of Thomas Sankara. He was a military leader who overthrew the previous government but he was a radical, revolutionary, and progressive military leader. Africans were generally skeptical of military governments because of their authoritarianism; it is a denier of rights and is not democratic and not accountable. But military governments were welcomed every now and then when the civilian system failed, and Thomas Sankara represented a progressive military takeover, and he promised revolution, progress, development. And so he was seen as a national hero, not only in Upper Volta which changed its name to Burkina Faso, but he was seen all over Africa as one of the leaders of the future who will bring change and development. Liberate Africa of neocolonialism, which is the continued hold by European power and major corporations over their destiny, bring an end to corruption, bring development, empower minorities. He was really welcomed, he was seen as a revolutionary national leader, but eventually he was overthrown. He was overthrown in 1987 by his deputy, who of course was not as effective as a leader, and so people continue to look to him today. He is seen as one of those visionary African leaders who was not able to carry out or execute their ideas. People compare him to people like Kwame Nkrumah who was a pan-Africanist pioneer, and this guy from the Congo Patrice Lumumba who was also one of those visionary leaders who ideas for Africa. They were probably naïve, they underestimated the power of the neocolonial forces, and it was during the Cold War that all these things were happening. So European powers, the French, the British, the Americans, the Belgians, were actively involved and they didn’t want these leaders. So because of that, these leaders didn’t survive for all kinds of reasons. Thomas Sankara is widely admired in Africa today, people see him almost like people in this country such as JFK, Martin Luther who was assassinated, RFK, or maybe Abraham Lincoln. These were visionary, revolutionary people so people continue to admire him. And today in Burkina Faso, two years ago they actually raise dup a monument celebrate him, and to get yourself to power in Burkina Faso now you have to connect yourself to him. So all over Africa he was seen as a radical, progressive leader. Even though many of them have what you call radical socialist credential, people there do not look at socialism in the negative way that people here do. Socialism is about giving power to the people, bringing development, ending corruption, and ensuring there will be a fight inequality and injustice in society. So he is one of those heroes in Africa that people continue to admire now.

While a former member of the ANC, Julius Malema has drawn a clear distinction between the goals and methods of the EFF and those of Nelson Mandela. How would you characterize Nelson Mandela’s legacy in the decades since the end of apartheid?

Mandela’s legacy, that’s a tough one. It is a huge one. Of course he was a pioneer in the liberation movement, the fight against apartheid and injustice is what sent him to prison. I think for me his legacy would be probably three ways: one, because of his guidance in the transition process from apartheid to a democratic South Africa, he was able to ensure stability. A peaceful transition- there were violence, there were all kinds of things- but South Africa escaped civil war that would have lasted for centuries. There were clashes between the ANC and the National Party that were likely formed by the apartheid agents, like the way Russia interfered in our election, but they turned one group against another. But Mandela used his experience, his age and maturity, to ensure peace overall. So, stability in transition. Two, reconciliation between the whites and the blacks in South Africa, because people were despairing that this would not happen, and would be a bloodbath between the two groups such as the Portuguese white. The Portuguese whites did not grant independence and fought the Africans through a colonial war, and by the time they were defeated they fled out of Africa. They were afraid that the whites in Africa would suffer the same fate. Mandela ensured that the two reconciled, that they were able to work together, that white people didn’t have to fear for their future in South Africa. He did this both by negotiating with them and by connecting with them, but also by drawing up a constitution, which would ensure that every group in South Africa would reconcile, and also by establishing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was chaired by the Peace Nobel laureate Desmond Tutu, which was meant to confront the horrors of apartheid and make people see it. Black and white coming together, each person brining their grievances, and then reconciling. It is not perfect but it has moved the country forward, and that is why the nation has continued. There is democracy, which was established, there is continued process of reconciliation, and there is also black empowerment and progress. South Africa still remained a major industrial power; the white people didn’t pull out their wealth and run away. They stayed- some people left, but the majority stayed in South Africa and they are still a part of their community in their country today. So I think that’s the major legacy for the country, to have brought that about beyond everyone’s wildest imagination, was very surprising. And lastly he showed us examples of what it means to be a statesman. To resolve conflict, you don’t have to fight each other to death, and the world today has still not learned that lesson, so he is a good example that you can have a position but still work together, and that whatever problem we have in the world, it can be solved through enemies talking to each other to find a way to resolve it without having to kill each other. Which is a lesson that is very hard for us to learn. So that is another lesson Mandela left behind, and that is very powerful.

Do you think the populism currently happening in South Africa is similar or different to contemporary populism in other parts if the world?

I think it is similar in one respect: it is a kind of movement trying to create a democratization of political and economic opportunities, which is similar to what is going on all over the world. Making the government accountable, making the government respond to the yearnings and desires of the vast majority of the people, I think it is very similar in that sense. In South Africa much of the populism we are having is related to problem of economic opportunities, continuing growth of inequality, and real and perceived injustice. As we have said before, power resides with the minority, the tiny fraction of the white population. Not all whites- it is a small group; there are whites that are poor and middle class, but the tiny group. That is not unique to South Africa, even in this country today there is a tiny group that controls the economy, and that is what capitalism does. But the majority of the poor are the black people. Black people expected after liberation and transition in 1994 that everything would happen. They will have a job, they will have a good house, they will have electricity, they will have education. There are some people that have gotten this, many more people than would have gotten it before, but many people are still left behind. There’s poverty, there’s inequality, and that’s a major problem. That’s what is fueling the populism that we have, this feeling of injustice and poverty that has become rampant.

0 notes

Text

We Have No HOME

I’ve finally had some free time to reflect upon my recent trip to East Africa - especially, in terms of my general “Back-to-Africa” outlook. And by “reflection,” I’m referring to the life-engaging process that deepens one’s thoughtfulness and distinguishes between a) reflection on experience, and b) reflection on the conditions that shape our experiences (Van Manen, 1991).

First of all, as Black Americans were are NOT African! Certainly, there’s much more to being African than simply being black (dark-skinned). If a man gets a boob job would we call him a woman? Obviously not! Biologically, chemically, skeletally he’ll always be a man despite having the outer appearance/features of a woman. And so the same concept applies for the Black American. Being black (dark-skinned) doesn’t make us African - though we share common physical attributes.

Not only so, but even native Africans themselves don’t consider us to be “African.” And why would they? We have almost no explicit connection to the culture, no direct tribal affiliations, nor do we speak a native African language (albeit, French is spoken in several African countries). As such, native Africans will always consider us to be mere Americans, Brits, or any other nationalities that we represent outside the continent. Let’s think about that and allow it to sink in for a moment???

While in Kenya, I had a great time going around and visiting many of the popular sites/attractions within Nairobi. By nature, Kenyans are very open to outsiders. I’m sure that being a former British colony has influenced them a great deal in this regard. And with English being a very widely spoken second language, it’s quite easy to strike up a conversation with anyone at random throughout the country. But again, though very outgoing and open to chatter, Kenyans will never consider Black Americans to be truly African. Therefore, I find it quite odd that we’re so quick to latch on to the label of “African-American.” This along with several others are labels that we’ve been branded with over history. Nigger, Negro, Afro-American, African-American, etc. But remember, these are names and labels that we were given - not ones which we as a people have actually coined for ourselves.

African-American? What does that really mean? Especially, when you personally visit an African nation and come to the very firm conclusion that we are not at all African in the least. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m a firm supporter of Marcus Garvey (d. 1940) and those other like-minded, early black pioneers who helped wake up the black masses from their long-standing delusions. America is not HOME, nor will it ever be! That was their slogan. These leaders clearly saw the writing on the wall, and it was time to start making preparations to migrate elsewhere. It’s as if Garvey could foresee decades into the future and envision black assassinations, political infiltrations, communal disenfranchisement, as well as, the present-day “Black Lives Matter” movement. For Garvey, it was much brighter on the other side of the rainbow (i.e Africa). And above all, his view was quite simple:

If you can’t beat ‘em, leave ‘em!

But yet despite this, there are also other factors which I do happen to disagree with concerning Garveyites. For instance, although fervent and sincere in his approach I don’t believe that he fully recognized both the social and logistical hardships with masses of Black Americans migrating to African lands. I have in fact researched about several small communities of Black Americans having some limited range of success with overseas migration. For example, the African Hebrew Israelite community that took refuge in Dimona, Israel under the leadership of the late, Ben Ammi (d. 2014). This community in particular is quite notable – as after decades of political and social campaigning many of their members were in fact able to secure Israeli citizenship via Israel’s Repatriation Program. But of course, this also came with several sharp stipulations including, mandatory military service in the IDF for young men/women under the age of 25. There’s also the Rastafari movement coming from both North America and the Caribbean in the 60s who were allocated small plots of land in Shashamane (Ethiopia) under the auspices of His Highness Emperor Haile Salisse (d. 1975). Several migrant Rastafari’s were given personal land of the Emperor in order to resettle in Ethiopia. Though successful in most respects, many Rastafari’s were never actually given full citizenship (residence permits only) and subsequently had to return back to the West. Nonetheless, these do serve as modern examples of how migrating in small numbers/communities and being persistent in your pursuits can eventually pay off quite rewardingly over the long term. However, I’m speaking more in terms of the “mass migrations” proposed by Garveyites and other Back-to-Africa movements.

In the broad sense, this is just simply impractical – and not mention, very unreasonable. You also have to keep in mind that even if mass hordes of Black Americans left North America to “resettle” in Africa (or elsewhere for that matter), they’d do nothing more than eventually cause an economic and social strain on the local, indigenous peoples. And sadly, this is exactly what many Americans (melanin-deficient ones in particular) use to overly criticize Latino immigrants in the US, and war-torn Arab migrants in Europe. So while Black migrants seeking African asylum would consider themselves as humbly “returning to the Motherland,” the native populous would come to view them with bitterness and discontent. And how can you blame them? Mass migrants would over-occupy jobs and exhaust other limited resources - especially seeing, that most African nations are still quite infant in their overall development.

So what does that all mean? Very simple; just like the title represents – we have no HOME! As a people we’re just going to have to get over this in one way or another. And even the idea of “home” itself – what or where is HOME exactly? Is it necessarily your land of origin (i.e. place of birth)? How about your passport – does it by itself truly elicit your “home?” For me, in many years of extensive travels around the world, I’ve humbly learned that HOME is wherever you can forge a social, economic and political future for both yourself and for your family. That’s HOME! Politics aside, you’ll need a place where you can have a feasible opportunity to buy land, own property, secure financial stability, establish business(es), while also having access to affordable education, healthcare and so on. And hey, if you can accomplish all of that from US living, then so be it. But I’m talking about the whole lot – not just a few of the above benefits. Having “partial” benefits definitely wont’ suffice. And so, beyond the meager 2-3% of black celebrities, entertainers, sports figures and a few notable politicians, etc, where does that leave the rest of the Black American masses? Can this remaining lot really acquire land, property, businesses, quality healthcare, and the like? Obviously not. Which means essentially, that the overwhelming majority of Black Americans are living on mere subsistence (i.e. just enough to survive). And so in total agreement with Garvey and others – the question remains…how long will Black Americans be satisfied with living in America on the outer periphery? This question certainly demands an answer. Does it not? Living paycheck to paycheck, and having just enough to get by every month certainly isn’t “success” by any stretch of the imagination. So what’s the solution – migration. And to where? Again, wherever you can accomplish the above mentioned social and economic distinctions.

Let me give a practical example. I have a good friend/colleague who took up residence in the Philippines after working several years in the country as an English teacher. By marriage to a local Filipina, this gave him direct access to all the rights and basic privileges of a local. In two years time he built a new home from the ground up in a promising residential area just near the beach – all for a fraction of the cost that you’d expect to pay in the US. Along with teaching, he also established a small English language school (private) and opened a restaurant catering to both American and local Filipino cuisines. He also has a young son from a previous relationship who spends a part of the year with him in the Philippines. Under the contract of his current international school he receives a tuition allowance for up to 2 dependents – which covers 100% of their tuition expenses.

Not only does his company offer Class A medical coverage for his entire family, they also provided free, furnished housing which he declined, as he has his own accommodation. He opted instead for the annual housing allowance which he then used to open his restaurant alongside his part-time English school. Make sense? And when asked about his own personal views concerning overseas living he says this: “For me, I’m all about looking ahead and being innovative in my thinking and world views. Personally speaking, I’ve never really felt like an ‘American’ while living in the United States. Our people have always lived on the outer fringes of American society. And obviously this isn’t going to change anytime soon. Therefore, as a people we must survive and advance - there’s no other alternative. It’s that simple! And so, I’ve found that living abroad can not only be financially and socially very rewarding, but it has also given me the chance to do and experience things that I never would’ve gotten from life in America - especially as a man of color. The US is like one big powder keg just waiting to explode! Black Lives Matter is only the beginning. I believe that another major civil rights movement is well under way in the United States. History always repeats itself. That nation was founded on prejudice and racial indifference. And therefore, race relations and other forms of racial discrimination will always be present in one way or another. And for me, life is simply way too short to be wasted away living in a nation with those types of principles. Not me. I’ve always wanted more for myself and my family. Not to bring up religion, but even the Islamic Prophet Muhammad and his people had to migrate away from their native land in Mecca as a means to preserve themselves and their religious integrity. I would say our situation as a people is much similar to this in certain respects. It all comes down to one’s outlook, and where your standards are set in life…"

Now the Philippines is certainly not Africa; not even close. But who cares! Which continent or country is beside the point. According to my view, my good friend is truly “successful,“ indeed. What more could you ask for? Above all, less than winning the lottery he could NEVER attain this level of status and privilege living in America. Overseas, he doesn’t have the daily worries of how he’ll pay the bills and provide for his family. No police brutalities or wondering whether he’ll make it home tonight to tuck his son in bed. No unfair labor practices that constantly keep him economically disenfranchised. Etc, etc, etc.

There are probably dozens of other factors which I could list in reference to my topic, but I believe that this quick snapshot is more than sufficient to make the matter very clear. But at the end of day, of course, to each his own. I just believe that it’s long overdue for us as Black Americans to start facing our apparent reality, and finding reasonable, viable solutions - elsewhere.

Works Cited: Van Manen, Max “The Tact of Teaching: The Meaning of Pedagogical Thoughtfulness,” 1991

#marcus garvey#black america#black lives matter#migration#back-to-africa#black politics#garveyites#african-american

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thursday 14th may, day 66

NOTE: i actually wrote this as a presentation letter to a guy on Slowly, but i really liked how it turned out so i thought “hm, might as well post this”. Here you go.

So here are 10 maybe-not-that-interesting facts about me.

1. My name in italian literally means "clear" and yet i have the same expression capability of a 5-year-old. It takes me forever to express myself in my native langue and I find it easier to speak in english, which can be quite a challenge when talking to my friends as you can imagine. Actually nobody calls me by my name, people usually refer to me by my surname, even my closest friends. (that's Cili if you where wondering, like red hot chili pepper)

2. In just a month i'll be graduating from high school and in september i'm going to start med school. I don't actually know why i'll be attending it since the very last thing i want to be when i grow up is a doctor. I have really, really low empathy so i don't think i could ever pull that off. Whant i want to be when i grow up is a resercher in neurosciences. There is nothing more fascinating then the human brain. I find utterly...disarming how everything we are, everything we do, all of our thought and movements are decided by how some tiny-iny particles of living matter interact with each other. The human body is the most beautiful of mysteries and everything it does is the result of a tiny miracle. I worship science. I love to find all the science that surrounds me and learn about it. And while i'm quite a thinker the subject i hate the most is philosophy. The only two authors i ever sincerely liked are Plato and Popper. The rest is garbage.

3. I have quite a memory. I perfectly remember stuff that has happened to me over 10 years ago. Like that one time when i was 8 and i was angry at my friend Dave so i started to throw comic books at him. Or how i used to go around my grandma's garden with my cousins dressed up in Sandocan costumes looking for pinecones that we would later smash in order to eat the pine nuts inside them. And how could I not mention when at 10 my friends and I organised a whole funeral for a ladybug that had drowned in their pool? we made this little raft out of a plastic plate, put the ladybug on it with some flowers and plants and then had a full celtic-like ceremony (we even wrote a eulogy). But the thing i remember the easiest are songs. I know hundres of thousands of song lyrics by heart. My playlist has over 600 songs and i can recognise any of them within 5 seconds (no kidding). Also i have the weirdest music taste. I like Queen as much as One Direction as much as early-2000s pop rock as much as indie as much as musicals. I believe music to be the expression of one's soul. Like, there are some songs that literally speak to the deepest part of me and if i didn't know any better i'd think they were written especially for me.

4. I'm an INTJ like Christopher Nolan, Elon Musk and Moriarty from Sherlock Holmes. I'm also a Ravenclaw even though Pottermore keeps putting me in Hufflepuff. As for the zodiac (in which i don't believe in but still read) i'm technically a scorpio but because i was born on the first day of scorpio at five past midnight, my zodiac-obsessed friend keeps telling me i'm a cusp which is something i had no idea existed until she pointed that out. As they say, you never stop learning.

5. I can solve rubik's cube in under a minute. My friend from robotics clubs tought me. Also, i'm in my schools robotics club. Last year we built a piano-playing robot and we're currently second in italy and forth in europe in our category. This year we were planning on going to the international competitions but then coronavirus happened so...yeah. Still, robotics is one of the best thing that has ever happened to me. Not for the club itself but for the people I met and for all the beautiful experiences and for that one time in october when we sneaked wine into our hotel room and the next morning i was so hungover i slept the whole day while tecnically competing.

6. I have a thing for alpacas. I don't know why, i think they're cute. I have a mug with an alpaca on it where i store my markers (i also have a thing for markers). One of my dreams is to see them in Machu Pichu (the alpacas, not the markers). I loooooooove travelling. It's the one thing i could never get tired of. I have an endless list of places i want to visit. My goal is to visit every continent before i turn 30 (the earlier, the better). So far i've been to North America (the USA, twice), Africa (Morocco and Egypt) and i've visited most european capital cities (London, Paris, Berlin, Madrid, Luxemburg, Bruxelles, and many other). As of right now there's Singapore on top of my list, immediatly followed by Peru. Travellig is such a unique experience. Every where you go there's always something new to learn and to discover. Different culture, different food, different languages. I adore languages of all kind. I'm fluent in italian (duh) and english (even tho i make tons of mistakes - i'm sorry), advanced in french and currently learning spanish.

7. I'm writing a book. Let me rephrase that - I'm writing a trilogy. It's actually a little more complicated than that to be honest. When i started high school i started writing this fairly awful teen-fiction-like novel and than i though to myself: why not make another book where i write the same exact story but from a different point of view and with a totally different style with no reason whatsoever? Five years later, i'm still not even halfway done with a first draft of any of the three books. I mostly use them as a creative outlet, something i do when i'm bored, just for the fun of it. But as stupid as they can be, they're still my creatures and i love them. Even though i'm sort of embarassed of them - no one i know has ever read them. I once tried to show the first few chapters to a group of friends and they still make fun of me for it (but they do it in that friend way that doesn't really offend, you know what i mean?). I just love words so much. I even have a list of favourite words written in my journal. Some exemples are "scrosciare", which is the italian word for the noise of heavy rain falling, and words that are what they mean, like obsolete and cacophonic.

8. if i were to write this last year, i'd tell you i don't believe in friendship. Now, my mind hasn't change that much, i still believe to have no friends in the way i consider a friend is supposed to be. And i know i talked about my friends quite s few times throughout this letter but i usually use this word in absence of something that better explains what i really feel. I'll try to make this as clear as i can. I struggle to make a connection with people. i always feel like people click with each other in misterious ways i have yet to understand. Most of those i identify as my friends are just the people i hang out with. There is no...spiritual connection? It's a little complicated to explain. As if at the beginning of times we were handed some instruction booklets on "human interaction and realtionships" and i lost mine, while everyone else carfully guarded theirs. The word that best describes what i think of most people is afecionado. I don't know where i read it but it pretty much explains it all - someone i feel affection for, but nothing else. I do have a best friend tho. I mean, best friend is quite a big word. I have a human being i feel more connected with in comparison to others. I’ve known him since forever and i hate him. I dont hate hate him as in i want him dead. I love him as a friend, he's a great friend. but i hate him as a human being. He's so goddam perfect it bothers me so much. Have you ever met someone that is just so annoingly good at any thing? well that's him.

9. I have never fallen in love. Not once. The last time i had a crush i was 11. This is what happens when you are an hopeless romantic who grew up reading love stories and at the same time a creepingly logical human. You have incredibly high expectations. And the only time i kissed someone it was more of a lips-touching-for-a-second kind of experience and we were both very much drunk (it was actually the first out of the three times in my life i ever got drunk, the third being the wine experience in october) When i first met said best friend everyone we knew shipped up ("shipped" as in the fandom term meaning two people should date) and there was a moment this summer when i thought i was developping feelings for him but it was just a second. And i may or may not have dreamed of dating this french guy i saw twice at a drama festival.

10. I love quotes. I think it's part of the memorising thing - learning quotes by heart. Songs, books, speeches, vines, stand up comedians. I also have a very weird sense of humor, basically anything makes my laugh like bad puns and dank memes. Anyway, i have this thing on my door where i write all the quotes i like. Mostly they're from songs, but i also have two from Dante's Divine Comedy. In italy we study it our third year of high school and my teacher is so obsessed with it that she made us learn over 200 verses by heart.

0 notes

Text

My Travel Story and How I Get Out of my Comfort Zone

TRAVEL - For starters, let me define a comfort zone. A comfort zone is everything you are familiar with. All habits, activities and places that unconsciously provide you with comfort and ease. On the soil of your country, surrounded by your family and your friends, you would rarely imagine yourself elsewhere, in a distant and foreign land.

It was not easy for me to leave behind a warm mother, a friend more than a father, a sister and a brother who will grow up away from my eyes. I missed everything, my choir, my family hikes and my grandmother's delicious tajines, but I managed to do it in the most beautiful way. If I, a 20-year-old girl, knew how to win, it's because you can too. I am confident that neither age nor gender is a limit for a free spirit and adventurer.

Putting your feet outside this area is a delicate but pleasant decision. It is human and understandable to fear the abstract, the failure and the judgments but, believe me, this courageous decision will mark your life forever. This transition allowed me to see a different world. I feel less vulnerable to failure and judgments.

Who would have thought that I would have arrived there one day? I am convinced that there is no better school than life and that there are no more hardships than the ones it makes us suffer every day. I had to endure a few happy times and others less. I received some hard knocks and I often fell down to get up much stronger and smiling.

If there is one thing I will not regret one day, it's nice to have made the trip not a fad but a lifestyle.

In saying this trip, I do not have in mind Rome, the Maldives or Thailand. There are so many places to discover in Morocco and so many activities to do. And then, meditation is, in itself, a spiritual journey.

I am often told: "You had a lot of luck and means to visit all these countries". Still, I do not believe in luck. I only believe in work and motivation. Luck will come to you only if you provoke it yourself.

Regarding the financing of travel, others add: "It is easier to work while studying abroad rather than Morocco." I only partially agree with that. While in Morocco, part-time jobs are scarce, but this is still possible. Many young Moroccans and Moroccans study and work at the same time.

In my opinion, the obstacle is a purely philosophical term and depends only on our own definition of the thing. In my opinion, "you are your biggest limit!"

I have kept two beautiful testimonies for the end. Smail, a 23-year-old Moroccan. Surfer and yoga teacher, traveling around Africa, and Tomas, 32, from Slovakia. Nomad for more than 8 years.

- Smail tells us about his trip around Africa and what he thinks about the comfort zone: "I have been traveling for 6 years to surf around the world, I usually work with my father in a restaurant to a duration of 6 months and I travel the rest of the time.

I visited several destinations but I particularly fell in love with Indonesia. At present, I am traveling around Africa. I decided to travel across my continent and the cradle of humanity. I also take the opportunity to help poor regions by installing filters for clean and safe water.

The most magical thing here is the kindness of people. They never leave their joy and their smile. They celebrate life every day as they should. While going to Liberia, I did not know the risks I was running: Ebola, malaria and other viruses.

One day, and after two weeks of surfing near the jungle, I felt very tired, I could barely walk. The signs were unfortunately those of malaria. I was hospitalized urgently in Accra. I'm better now, I recently got out of the hospital. I take this opportunity to give me back.

As for my trip in itself, I have not really had any sudden transitions since I was 12 years old. At that age, I was already on the road. I have always had a special love for travel and adventure. This helped me a lot in forging my personality but I was lucky not to come across bad people.

Despite what I had to endure during this trip to Africa, I have no regrets and I am sure to never have any. Africa is to take with its galleys and its diseases. His joy and his suffering. All this makes us who we are. It is very important to get out of the bubble and to discover the world. "

- Tomas also shares with us his story with the journey and his exit from his comfort zone: "I come from Slovakia, I am 32 years old and I have been married for almost 5 years, my first adventure as a nomad 12 years ago After school and army, I could hardly find work because I refused to work for the government I'm not the kind of person to be I did not want to be the man with the gun either, so I applied everywhere, to be finally hired in the Czech Republic, not far from home.

I have always had the desire to travel since I was little. When I was six years old, when I was asked what was my craziest dream, I said: go around the world to finally settle in your most beautiful corner.

So Prague was my first destination. And that's where the adventure started and my love for the journey began to grow and evolve.

After a few years in Prague, my French roommate and I decided to come back home. This time, I was quickly hired by a major bank and I quickly became one of the highest paid bankers in the region. I had a very good career in a very short time. In short, my comfort zone was growing. How to drop all this and start from scratch in another far country?

The situation was becoming more and more complex in the country, the monetary system also and above all, my dream of a little boy that I saw leaving. One day, looking at myself in the mirror one morning, I decided to sell everything and leave. Today, and after 8 years of travel, I speak with great joy and pride. I will never have been the same without this lifestyle that makes all my happiness and stability. I met my wife in India. It turned out that we are coming not only from the same country and from the same city, but also from the same neighborhood. She too decided to go on a discovery of the world. We make our life, while waiting for nomadic children too ".

The future is uncertain. I do not know if I will exist tomorrow but I am alive today so I take advantage of it. As I walk away, I am well aware of what I leave behind but I am even more aware of the value of what I miss by locking myself at home.

I propose to go to the discovery of yourself: put yourself to the test! And know that your exit from the comfort zone can really be done while being in Morocco.

0 notes

Text

Do you know anyone from Bujumbura, Burundi? Sounds exotic, right? Well, how about curious, witty, kind, opinionated…and all about adventure? Wait, am I still talking about Bujumbura or the best export they’ve ever exported? I may be talking about Nellie Umutesi-Vigneron. I may be comparing Africa with this woman. She’s generous, she’s bold, and she’s beautiful. Read on to discover more about this extraordinary woman…

What do you love to do? So many things I love to do… My top three would be spending time with family, read, a good glass of Pinot Noir, hike and camp (ooops that’s 4). I do it as often as time permits. Most of my family lives in Rwanda and Burundi, so I make time to visit home every couple of years. I read quite often, I average 2 books a month. I hike year round and camp whenever the weather permits. I make time to do the things that I love, they help me stay active, feel alive and replenish my soul!

What can you do today that you could not do a year ago? I can travel solo in a country that does not speak my language. I am fluent in both English and French and would always pick countries whose official language were either. Last year, I embarked on my first solo trip to Cuba and Costa Rica and to my surprise was able to communicate with my limited Spanish or used a lot of hand gestures.

Do you like your job? I love my job and the people I work with. More importantly I love the fact that with my job I am able to afford a pretty decent life for my son and myself as well as fund my adventures and passions. I have always looked at work or a career as a leverage to do the things that I want to do.

What would you regret not doing? Not sharing my love for adventure and the outdoors with other girls and women. Adventure has done so much for me in terms of self-esteem and having a positive outlook on life. It is not simply doing something new, it is more setting aside my fears and knowing that I can do anything I put my mind to. I want that same feeling for everyone. Last year, I made it a goal to share this with other women and girls and organized my first mother/daughter yoga event. For everyone who attended, it was something new, a time for mothers and daughters to bond and a start of them thinking of other things they would want to experience. It was a total success! Not going through this event (cause I was so scared it would be a complete flop), not sharing my passion will be one of my greatest regrets… and I won’t let that happen!

Note: I will always be referring to this paragraph as inspiration to not let my fears define my walls. Thank you, Nellie. TCW

When was the last time you traveled somewhere new? My latest new destination was Costa Rica and I fell in love with the people, the country, the food. It is an adventure paradise for an adventurous chica like myself. I first stayed in the rural part of the country. Stayed with a Costa Rican family, cooked and shared meals with them, volunteered at the local elementary school. Then I moved to another city, Samara, closer to the beach, where my days were filled with surf lessons, ziplining, horseback riding, sun bathing. I love Costa Rica because you get it all. If you love adventure or if you like to just lay on the beach sipping a mojito, there is something for everyone!

Have you done anything lately worth remembering? In December 2016, I went Gorilla Trekking in Rwanda. It was EPIC. I still look over the pictures and cannot BELIEVE IT! It was a hard trek but it was oh so worth it and being really close to silver back gorillas is freakishly scary and humbling!

What does success mean to you? First it means being a good mother to my son, exposing him to different cultures and adventures, giving him the BEST opportunities in this world. Success also for me is not to be constantly on a high, always happy, but also learning to manage and cope with the difficult times (because they will come). Success for me is always trying, maybe not always succeeding, but damn sure try my hardest!

What are you doing to pursue your dreams right now? I dream of visiting every country on the African Continent so I make it a point to visit on new African country per year (if budget allows). Finally, I created with the help of a friend, Adventurous Chica. We are essentially sharing stories of others; Adventurous girls and women. We also give 3 scholarships per year to deserving young ladies who want to attend an outdoor/adventure camp. Finally I have 4 events per year where I take women and girls kayaking, camping, hiking and some yoga!

What are you most scared of? Death scares me, but not just death, but also dying without having realized my dreams.

What are you most proud of? Being a mother to my son is what I am most proud. I take motherhood very seriously and want to give him all of the opportunities in the world to succeed (whatever his own definition of success is).

Where would you like to live? I am happy to call Atlanta my home for now, but definitely see myself living either in Senegal or Rwanda later on in life. Moving does not scare me at all, but I don’t think it is quite time yet.

If you left your current life in order to pursue your dreams, what would you lose? A steady paycheck.

What bad habits do you want to break? I am ashamed to say but I am a smoker. I have been struggling to quit for the last year or so, but I know one day I will be smoke free.

If you were someone’s life coach, what would you tell them? Freedom and happiness is on the other side of fear. From the stories others tell us to the stories our minds make up, fear can be paralyzing at time. Once I realized that fear is just an illusion everything changed for me. I still get afraid, but I don’t let it overtake me. A lady I look up to once told me: fear is growth! And I agree!

Fun and furious questions:

If you could do it all over again, would you change anything? Yes, maybe a couple of heartbreaks I’d avoid.

How old would you be, if you didn’t know how old you are? 30 year old.

What activity makes you lose track of time? Hiking

Best cheat indulgence? Pinot Noir

If you could only speak one word today, what would it be? Grateful.

To stay up to date with Nellie, follow her social media sites here:

Adventurous Chica

Facebook

Instagram

Much love and Aloha,

your I’m a big fan! clueless wanderer

Nothing is stopping this single parent! Bonjour, Nellie Umutesi-Vigneron!!! Do you know anyone from Bujumbura, Burundi? Sounds exotic, right? Well, how about curious, witty, kind, opinionated...and all about adventure?

0 notes

Text

The Red Sea

DURING THE DAY of January 29, the island of Ceylon disappeared below the horizon, and at a speed of twenty miles per hour, the Nautilus glided into the labyrinthine channels that separate the Maldive and Laccadive Islands. It likewise hugged Kiltan Island, a shore of madreporic origin discovered by Vasco da Gama in 1499 and one of nineteen chief islands in the island group of the Laccadives, located between latitude 10 degrees and 14 degrees 30' north, and between longitude 50 degrees 72' and 69 degrees east.

By then we had fared 16,220 miles, or 7,500 leagues, from our starting point in the seas of Japan.

The next day, January 30, when the Nautilus rose to the surface of the ocean, there was no more land in sight. Setting its course to the north-northwest, the ship headed toward the Gulf of Oman, carved out between Arabia and the Indian peninsula and providing access to the Persian Gulf.

This was obviously a blind alley with no possible outlet. So where was Captain Nemo taking us? I was unable to say. Which didn't satisfy the Canadian, who that day asked me where we were going.

"We're going, Mr. Ned, where the captain's fancy takes us."

"His fancy," the Canadian replied, "won't take us very far. The Persian Gulf has no outlet, and if we enter those waters, it won't be long before we return in our tracks."

"All right, we'll return, Mr. Land, and after the Persian Gulf, if the Nautilus wants to visit the Red Sea, the Strait of Bab el Mandeb is still there to let us in!"

"I don't have to tell you, sir," Ned Land replied, "that the Red Sea is just as landlocked as the gulf, since the Isthmus of Suez hasn't been cut all the way through yet; and even if it was, a boat as secretive as ours wouldn't risk a canal intersected with locks. So the Red Sea won't be our way back to Europe either."

"But I didn't say we'd return to Europe."

"What do you figure, then?"

"I figure that after visiting these unusual waterways of Arabia and Egypt, the Nautilus will go back down to the Indian Ocean, perhaps through Mozambique Channel, perhaps off the Mascarene Islands, and then make for the Cape of Good Hope."

"And once we're at the Cape of Good Hope?" the Canadian asked with typical persistence.

"Well then, we'll enter that Atlantic Ocean with which we aren't yet familiar. What's wrong, Ned my friend? Are you tired of this voyage under the seas? Are you bored with the constantly changing sight of these underwater wonders? Speaking for myself, I'll be extremely distressed to see the end of a voyage so few men will ever have a chance to make."

"But don't you realize, Professor Aronnax," the Canadian replied, "that soon we'll have been imprisoned for three whole months aboard this Nautilus?"

"No, Ned, I didn't realize it, I don't want to realize it, and I don't keep track of every day and every hour."

"But when will it be over?"

"In its appointed time. Meanwhile there's nothing we can do about it, and our discussions are futile. My gallant Ned, if you come and tell me, 'A chance to escape is available to us,' then I'll discuss it with you. But that isn't the case, and in all honesty, I don't think Captain Nemo ever ventures into European seas."

This short dialogue reveals that in my mania for the Nautilus, I was turning into the spitting image of its commander.

As for Ned Land, he ended our talk in his best speechifying style: "That's all fine and dandy. But in my humble opinion, a life in jail is a life without joy."

For four days until February 3, the Nautilus inspected the Gulf of Oman at various speeds and depths. It seemed to be traveling at random, as if hesitating over which course to follow, but it never crossed the Tropic of Cancer.

After leaving this gulf we raised Muscat for an instant, the most important town in the country of Oman. I marveled at its strange appearance in the midst of the black rocks surrounding it, against which the white of its houses and forts stood out sharply. I spotted the rounded domes of its mosques, the elegant tips of its minarets, and its fresh, leafy terraces. But it was only a fleeting vision, and the Nautilus soon sank beneath the dark waves of these waterways.

Then our ship went along at a distance of six miles from the Arabic coasts of Mahra and Hadhramaut, their undulating lines of mountains relieved by a few ancient ruins. On February 5 we finally put into the Gulf of Aden, a genuine funnel stuck into the neck of Bab el Mandeb and bottling these Indian waters in the Red Sea.

On February 6 the Nautilus cruised in sight of the city of Aden, perched on a promontory connected to the continent by a narrow isthmus, a sort of inaccessible Gibraltar whose fortifications the English rebuilt after capturing it in 1839. I glimpsed the octagonal minarets of this town, which used to be one of the wealthiest, busiest commercial centers along this coast, as the Arab historian Idrisi tells it.

I was convinced that when Captain Nemo reached this point, he would back out again; but I was mistaken, and much to my surprise, he did nothing of the sort.

The next day, February 7, we entered the Strait of Bab el Mandeb, whose name means "Gate of Tears" in the Arabic language. Twenty miles wide, it's only fifty-two kilometers long, and with the Nautilus launched at full speed, clearing it was the work of barely an hour. But I didn't see a thing, not even Perim Island where the British government built fortifications to strengthen Aden's position. There were many English and French steamers plowing this narrow passageway, liners going from Suez to Bombay, Calcutta, Melbourne, Reunion Island, and Mauritius; far too much traffic for the Nautilus to make an appearance on the surface. So it wisely stayed in midwater.