#skaldic alliteration

Text

So I don't normally do this, but since my latest Lord of the Rings rewatch I've had this bouncing around my head, and finally am getting it out. So, poetry! This one is for Théodred, and I did my best to get the skaldic alliteration of Tolkien's Rohirric verse.

Simbelmynë

Forever they grow there, the fathers' graves watching;

white flowers covering, warding the dead.

Théodred lofty, Thengel's fair grandson,

alas they await him at his road's end.

Master of horses, the Mark's second Marshal,

prince of the people, proudly he stood.

At Isen's fords, with iron he fought there

with Saruman's forces, and slain there he fell.

Last of his line, Lord Théoden's only,

Dead in the river. So death we dealt then,

avenging the fallen, answering insult.

War we woke, the Westfold arising;

at Helm's Gate we harried the foe to the end.

The White Hand we withered, the wizard defying;

by spear and by sword we slew the dark host.

Still Simbelmynë, silent and silver,

his tomb it protects now til years have an end.

With Fréa he lies, Folca and Fréalaf;

In the ranks of his fathers he rests evermore.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scandinavia - Old Norse Poetry - Structure and advice on writing imitations

(Some of this will be copy-pasted from my previous post on Old Norse literature and oral tradition)

OLD NORSE POETIC FORMS

Old Norse poetry utilizes a modified form of alliterative verse. In simpler terms, the metrical structure is not necessarily based on the last syllables of a line or phrase rhyming...

Ex: (lines from William Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis) “And so in spite of death thou dost survive / In that thy likeness still is left alive”

... the structure relies on the repetition of multiple initial consonants in a line or phrase.

Ex: (from the Hávamál of the Codex Regius) Deyr fé // deyja frændr

SKALDIC POETRY

Primarily documented in sagas, skaldic poetry is usually about history, particularly the celebrated actions of kings, jarls, and some heroes. It typically includes little dialogue and recounted battles in dialogue. It has more complex styles, especially using dróttkvætt and many kennings.

DRÓTTKVÆTT (“courtly metre”)

- Adds internal rhymes and assonance (repetition of both consonants AND vowels) beyond the normal alliterative verse

- The stanza had 8 lines, each line usually having 3 lifts (heavily stressed syllables) and almost always 6 syllables

- The stress patterns tends to be trochaic (stressed, unstressed), with at least the last 2 syllables of a line being a trochee (usually...)

- In odd-numbered lines (first line, third line, etc.): 2 of the stressed syllables alliterate with one another; two of the stressed syllables share partial rhyme of consonants with dissimilar vowels (ex: hat and bet; touching and orchard)

- In even-numbered lines (second line, fourth line, etc.): the first stressed syllable must alliterate with the alliterative stressed syllables of the previous line (an odd-numbered line); two of the stressed syllables rhyme (ex: hat and cat; torching and orchard)

These requirements are SO difficult that oftentimes poets would mash together two separate lines of writing in order to meet the structure. It’s really hard to explain, so read the wikipedia link here for more info.

KENNINGS

Kennings are figures of speech strongly associated with Old Norse-Icelandic and Old English poetry. It is a “type of circumlocution, a compound employs figurative language in place of a more concrete single-word noun” (source).

Now, when I first read that, I had zero clue what the hell that meant. But this is my current understanding: a poetic device where you dance around using a single noun by describing it with other words. It is similar to the poetic device of parallelism.

- “bane of wood” = fire (Old Norse kenning)

- “sleep of the sword” = death (Old English kenning)

- Drahtesel = “wire-donkey” = bicycle (modern German kenning)

- Stubentiger = “parlour-tiger” = house cat (modern German kenning)

- Genesis 49:11 “blood of grapes” = wine

- Job 15:14 “born of woman” = man

A beautiful resource for translated kennings is this article here from the HuffPost’s Harold Anthony Lloyd.

SIMPLE KENNINGS

Simple kennings would be used in both Eddic and Skaldic poetry.

The usual forms are a genitive phrase (ex: the wave’s horse = ship) or a compound word (sea-steed = ship). There is usually a base-word and a determinant.

The determinant may be a noun used uninflected as the first element in a compound word, with the base-word being the second element of the compound word.

OR the determinant may be a noun in the genitive case placed before or after the base-word, either directly or separated from the base-word by intervening words. The base-words in the above examples are “horse” and “steed”, while the determinants are “waves” and “sea”.

The unstated noun which the kenning refers to is called its “referent”, in the example a bit above: ship.

COMPLEX KENNINGS

More complex kennings are really only used in skaldic poetry.

In these, the determinant and sometimes the base-word are themselves made up of kennings. A matryoshka doll of kennings, if you will.

Ex: “feeder of war-gull (bird)” = “feeder of raven” = “warrior” (referring to how warriors kill people and leave their corpses for birds to eat)

The longest kenning in Skaldic poetry belongs to Þórðr Sjáreksson’s Hafgerðinga where he writes “fire-brandisher of blizzard of ogress of protection-moon of steed of boat-shed”, which means “warrior” (source).

EDDIC POETRY

Eddic poetry is usually about mythology, ethics, and heroes, and is narrative (where both the narrator and the characters are speaking). They use simpler structures, like fornyrðislag, ljóðaháttr, and málaháttr, and use kennings more sparingly.

FORNYRÐISLAG (”old story metre”)

- Each line tends to be a whole phrase or sentence (or end-stopped), where a sentence won’t “run over” and onto the next line (or enjambment).

Ex: End-stopped, from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet “A glooming peace this morning with it brings. / The sun for sorrow will not show his head.”

Ex: Enjambed, from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land “ Winter kept us warm, covering / Earth in forgetful snow, feeding / A little life with dried tubers.”

- Each verse is split into 2 to 8 (or more) stanzas.

Ex: from Waking of Angantyr (structure provided by wikipedia)

- There are 2 lifts per half line, usually with two or three unstressed syllables. At least 2 (but usually 3) lifts will alliterate, always including the main stave (the first life of the second half-line). This means there are usually between 4 and 5 syllables per half line, and therefore between 8 and 10 syllables per full line (but it can vary).

MÁLAHÁTTR (“conversational style”)

- Similar to fornyrðislag, but there are more syllables in a line.

- It adds an unstressed syllable to each half-line, making the typical 2-3 per half-line and 4-6 per line into 3-4 per half-line and upwards of 6 unstressed syllables per line

LJÓÐAHÁTTR (“song” or “ballad metre”)

- Usually made up of stanzas with four lines each

- Odd numbered lines were usually standard lines of alliterative verse with 4 lifts and 2 or 3 alliterations. It was cut in half with a “cæsura” or “//”, which indicates the end of one phrase and the beginning of another.

- Even numbered lines had 3 lifts and 2 alliterations, with no cæsura.

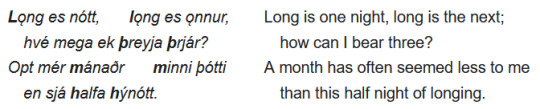

Ex: from Freyr’s lament in Skírnismál (structure provided by wikipedia)

WRITING IMITATION

When writing an imitation of Eddic and Skaldic poetry, there are many workarounds if you don’t want to jump through these hoops.

Personally, I am putting forward my imitation as a “translation” of an Old Norse text so I don’t need as much concern for alliteration, rhymes, and exact syllables.

But I enjoy having a similar feel to the original poems, so I do try to put in some alliteration for words that are of Norse/Germanic origin and keep a similar syllable count.

Posted: 2023 May 29

Edited last: 2023 May 30

Writing and research by: Rainy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eyrbyggja Saga Week 4

*deep breath*

skaldic verse is my fucking favorite. i love skaldic verse. somebody many centuries ago saw the opportunity to take their historical drama and also make it be a musical. and it slaps. i think the author added them because it fucking slaps, and it’s a really interesting narrative device that lends a level of artistic emphasis to the scene. if at this point as an audience member, you’ve tuned out any of the litany of borderline indistinguishable names or the loosely retold historical events that you probably already loosely know of, the actual poetry of the saga punctuates the experience in a really unique way. the rhythm and the alliteration and the shape of the sound reflects the emotional impact of the words. it’s debatable whether it’s learned or innate, but we all respond in specific and distinct ways to repetitive sounds, dependent on whether they’re percussive or resonant or sibilant or whatever. (and i think it’s worth mentioning that vocal, sound-based enchantment is such a notable part of the old norse mythos. the overlap between galdr and using skaldic verse to influence the emotional state of the audience makes me 👀) it serves to ratchet up the emotional tension. even beyond that, it gives the author an opportunity to really, stylistically, go ham with imagery that might go relatively understated in the prose. take as an example

slander forced me

to defend my fame.

ravens feasted then,

fattened by the spear's lust:

busy, the blade rang

battering my helm;

blood-tides surged

like surf at my side.

that’s fucking terrifying. (and i love that he has to walk back his bravado almost immediately with “i loathe the strife/of the scarlet shield wall” like yes. the imagery. yes.) it’s evocative as shit and i can only imagine that the experience of sitting in a firelit room, over a communal meal, all of your focus locked onto an orator who is all but given over to the narrative just throws the mental sensory construction of that scene and the sense of awe into sharper focus.

and actually while i’m loosely on the subject of narrative devices i love the repetition of arnkel and his men coming to search katla’s house for odd. it’s so good and so reminiscent of modern campfire stories. you even see the same motif of repeating an action three times and then having a different outcome after a final repetition in children’s books that are intended to be read aloud and it’s? idk it’s really interesting to me that the way oral storytelling works is so surprisingly universal.

i’m...not really sure what to say about the social forces at work. there’s a lot to unpack in this week’s reading that’s very very telling. i mostly just feel sad for thorarin, if i’m honest. damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t. his progression from being accused of insufficiently holding up cultural standards of masculinity, to feeling honor bound to repeatedly defend his reputation with violence, to what can only be described as deep depression, to being legally bound to flee to country is just...sad. it’s paints an absolutely fucking dismal picture of old norse society and like. i feel like more than a few of those social elements still hit uncomfortably close to home in 2020.

i’m still puzzled by katla v geirrid. i’m really looking forward to reading the article that was posted but i just haven’t had the chance yet. katla’s curse is going to lead to some wild shit, i can feel it. i can only assume his trip abroad which was very well thought out and not at all a panic move is going to go poorly because of Saga Family Drama.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

The alliteration poems remind me of skaldic poetry. Just needs more kennings.

I definitely need to read more skaldic poetry, pick up some techniques from that era. Especially because I can’t have the bad ass title of Skald until I learn how to utilize the poetic tools properly

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey. I hate using names and tend to call Loki by trickster or any of his other names, I also call Freya the lady or some variation of that. So what I’m asking is it okay to nickname gods?

Wonderful news! Using poetic alternate names for the gods (and people, and pretty much everything else) is a common convention in skaldic poetry, and one of the things that distinguishes it as an art form! A decent chunk of Skáldskaparmál, a book in the Prose Edda, is devoted to listing them.

These alternate names are called heiti. And there’s a special kind of heiti that functions sort of like a riddle. These are called kennings. For example, instead of calling the sun “the sun”, a skald might call it something metaphorical like the “sky candle”, often because it fit the meter better or allowed for alliteration. Their tone can range from serious to playful to outright crude humor.

You can find a list with many of the heiti used for Loki in the lore in this post. And making your own is very much in keeping with the literary tradition of the myths.

- Mod E

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's loki's view on puns????? various wordplay???

send me some heckin headcanon asks.

i mean, she invented ’em, so....

NAH. i mean, loki’s not responsible, but old nordic and proto-germanic languages are absolutely renowned for their understated complexity and capability for wordplay! i mean, if you look at skaldic poetry alone, it’s built entirely on alliteration/consonance and the interplay of sound and meter, and early germans are well noted for their sarcasm, especially documented in by-names. gorm the sleepy, first king of denmark? not a sleepy dude. known for swiftly and mercilessly crushing threats and seizing power. eric the memorable, further down the danish line, a complete fucking dick that all the danes wanted to forget as soon as possible. a figure we’re more familiar with, r/agnar l/oðbrók? loðbrók means shitty pants. it’s an inverse on him being fucking fearless. r/agnar don’t shit himself.

and then, you know, you have all this set up and then you take a god like loki who’s based entirely on wit and insight, of course she loves wordplay in all forms. puns probably delight her, and she’s incredibly prone to twisting language in general, particularly with a tendency to slip into alliterative/consonant styles of speech, since poetry is a big thing in the nordic world and it influences loki a lot. and with the above example, i mean, is it any surprise loki tends to say the exact opposite of what the hell she means, or come off so bitingly sarcastic that it’s kinda upsetting sometimes? she doesn’t mean it (all the time), she’s just used to manipulating language to worm in more meaning per word than people expect.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The poetry of medieval Scandinavia is generally divided into two categories, Skaldic Poetry which are by known skalds (poets) and a system of diction and metrics explained in Snorri’s Edda and Eddic Poetry, which is loosely defined as poems that are anonymous, possess a simple, flowing meter and deal with myths and legendary Viking heroes. However, there is a variety of opinion on what qualifies as ‘Eddic Poetry’ and the term is also traditionally used to refer to to refer to the Codex Regius, a collection of anonymous poems that deal with wisdom, mythology and heroic legend. Both categories have fairly fluid definitions and often there is overlap between the two genres.

Viking Poetry was derived from an oral tradition, distinguished by it’s use of alliteration and kennings (compound expressions with metaphorical meanings). Many of the sagas have stanzas of poetry inserted into the prose for dramatic function; this mixed prose-poetry model that is found in written sagas may have been inherited from previous oral traditions. In the sagas, one common characteristic of Viking heroes, besides bravery in battle, was the extemporary composition of verses. This demonstrates how the composition of poetry was viewed as an admirable skill and served an important function in Viking society and culture. In Egil’s sagas, the eponymous character composes a poem in order to express the grief of losing his sons; at the end he thanks Odin (who is attributed with granting mankind the knowledge of poetry) for the splendid gift of poetry. Egil describes poetry as being without blame or blemish; indicating that Old Icelandic poetry was considered morally and artistically perfect within the culture.

The subjects of these verses, besides the mythic and legendary narratives of eddic poetry, include grief, consolation, love, death and even poetry itself. However the most common of the poetry that has been preserved is one that is characteristic of Viking poetry: praise poetry, which is poetry composed for the living or recently dead in order to celebrate and perpetuate the name and glory of its subject. This is because throughout the 10th and 11th centuries, skalds would travel to the courts of kings and jarls to offer praise poetry with the expectation of reward. This ritual legitimized the King’s claim to his position and affirmed the values of the warrior class (as the subject would be praised for the traditional virtues of generosity and valor). These poems were then passed down orally until they were recorded by Icelandic writers in the 12th-14th centuries, which is where nearly all (excluding the Codex Regius) of the preserved Viking poetry comes from. [x][x]

World of VIKINGS ✦ Viking Poetry

#vikingsedit#vikings#perioddramaedit#worldofvk#new series!!! surprise!#as always remember that I am not an official historian#but I am going to pull from resources in order to do this not my memory#so you can always check the sources or correct me if you find something incorrect#feel free to suggest additions btw!#the sagas#Havamal#egil's saga

1K notes

·

View notes