#pierre mauclerc

Text

#Celtic Civilization by Jean Markale#Alix come get your man he's exhibiting Behaviors 😩#philippe auguste looking at brittany‚ high af: idek let my insane cousin try#thirteenth century#pierre mauclerc#shakespeareomnibus

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blanche as Regent, and the narrative of Louis's minority

There was no real threat or challenge to the status of young Louis as king. He had been designated by his father in his will, and the Capetian line had descended from father to son since 987. But when power was personal, minority government was always contested government. Magnates like Theobald of Champagne and Peter Mauclerc, who had been chafing under the heavy fists of Philip Augustus and Louis VIII, would certainly take advantage of the minority to push claims to additional land and power as far as they could, and protect themselves against what they saw as royal encroachment on their lordships. Others who were fundamentally loyal to the Capetians would still see a minority as an opportunity to bolster their positions. Peter Mauclerc was already exploiting Henry III's desires to regain the Angevin lands as a lever of personal power: he would not let slip the opportunity offered by a minority. All this could be expected.

Blanche's status as guardian and custodian of king and kingdom was another matter. There were no established norms for regency, whether in the case of a minority or when the king was out of the country in Crusade. The only previous Capetian to have succeeded as a minor was Philip I in 1060. The realm was ruled during his minority by his uncle by marriage, Count Baldwin of Flanders, probably with some assistance from Philip's mother, Anna of Kiev. Arrangements for Crusading regencies had varied. Philip Augustus had left the country in the guardianship of his mother, Adela of Champagne, her brother, the archbishop of Reims, and six prominent Paris merchants, who supervised the financial accounts. During the Second Crusade, the regents, "elected" under the influence of Bernard of Clairvaux, were an unlikely, and not very successful, triumvirate: Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, the archbishop of Reims and Louis VII's cousin Ralph of Vermandois. No powers were vested in Louis VII's mother, Queen Adela of Maurienne. The great principalities had a stronger tradition of leaving power in the hands of an absent prince's wife or a minor prince's mother. Recent notable examples were the successive countesses of Champagne, Mary of France and Blanche of Navarre. But leaving the kingdom in the hands of the queen alone was novel. (At least in France, though there was the recent example of Margaret of Navarre in Sicily). At the very least, one might have expected her to hold power jointly with a prominent churchman. The archbishop of Reims was the traditional choice- but William of Joinville had died shortly before Louis, on the return from the Albigensian Crusade.

[..]

There certainly were challenges to the regency from the French baronage. Political songs of the day accused Blanche of sending money to Spain, and accused both Blanche and Walter Cornut of preferring the men of Spain to the barons of France. They accused Blanche of keeping young Louis unmarried so that she could remain in power, and accused her of being the mistress of, variously, Theobald of Champagne and Cardinal Romanus Frangipani. Like most regents, Blanche would have to make concessions and obtain by diplomacy what a king would have obtained by command.

The narrative of Louis's minority produced by all his biographers, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, William of Nangis and Joinville, is a dramatic one, of terrible threat to Blanche's rule, and even to the king himself. All of them were writing long after the events, but all of them knew many of the protagonists, and reported first-hand accounts from Louis himself. The same dramacic story is told by the contemporary chroniclers, the Flemish Philip Mousquès, the English Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris, and the slightly later Ménestrel of Reims. But there are problems with all these sources. Their chronology of events is unclear and sometimes contradictory. Wendover may have had some information from those who campaigned with Richard Marshall alongside the most fractious of the French barons, Peter Mauclerc; at all events, Wendover's account, while a splendid source of French "baronial" gossip, is not always reliable as to facts. Matthew Paris, reworking Wendover's text, could not resist the baronial gossip, though he often dismissed it as lurid rumour. Of the contemporary French chroniclers, Philip Mousquès was well informed on French court gossip from a Flemish perspective, but his chronology is confused. The Ménestrel of Reims' court gossip was more second-hand, and his main aim was to entertain: his chronology is even more confused. St Louis's biographers tend to collapse together events that happened over a long time span, while Joinville, as seneschal of Champagne, was particularly concerned with events in and affecting that county. For all these sources, the narrative of the valiant widowed queen protecting her young son against the powerful wicked barons of France was irresistible. Indeed, it is clear from Louis's reminiscences, as reported by his biographers, that it had become the family's own narrative.

But it is a dramatization and an oversimplification. Many French magnates remained loyal. Those who proved particularly fractious had already been so under Louis VIII. The most consistent plotter of all, Peter Mauclerc, count of Brittany, continued his conspiracies long after St Louis had reached his majority; and Theobald of Champagne's major revolt occurred under Louis's personal kingship. Private war remained endemic in France, though Louis tried to outlaw it, to the disgust of his barons, in 1258. Blanche faced a continual need to control marriage alliances that might lead to dangerous power blocs — but that had been true in the previous two reigns, and continued to be an issue after Louis attained his majority. Much of the worst trouble was not aimed at toppling Blanche’s status as guardian of the realm; it was a series of attacks against Theobald of Champagne. The succession to Champagne had long been an issue, as had the border zone berween Champagne and Burgundy. Blanche and Louis intervened, for the king (or his regent) should ensure peace within his realm, and they did so with reasonable success. The exact chronology of the troubles is difficult to establish, but it seems that, after a difficult few months, stability had been restored by March 1227. In summer 1229 came the major attack on Champagne by members of the Burgundian aristocracy together with various related allies — though the fact that their relations included Peter of Brittany gave it a dangerous edge, for Peter was also plotting an invasion from England with Henry III. By summer 1230 it was clear that had failed, and although Peter of Brittany made war in western Normandy and the western Loire in most subsequent campaigning seasons until 1236, he was increasingly isolated. After 1230 he was an irritant rather than a threat to the Capetian kingship.

Joinville makes much of Blanche being a foreigner, from Spain, "who had neither relatives nor friends in all the kingdom of France". This was untrue. She had both friends and relatives on whom she could depend. The friendship and patronage networks that she had developed since her arrival in France, as the Lady Blanche and as queen consort, now supported her. The administrators, both lay and eccsiastical, who had worked so closely with her husband, and who were in many cases inherited from Philip Augustus, notably Bishop Guérin of Senlis (until his death in April 1227), Walter Cornut, archbishop of Sens, and his relations, the Clément family, Bartholomew of Roye, the chamberlain, and Matthew of Montmorency, the constable, proved intensely loyal. It was in their interests to support the Capetian crown, from which they derived their power and prestige. They might have been slightly cool in support of a queen regent, but they were not. Like her husband, Blanche could rely on the support of the aristocracy of the north-east, where her dower lands lay, such as Michael of Harnes, Arnold of Audenarde and John of Nesle, and on some of the most important reformist churchmen, notably the Cistercian bishop Walter of Chartres. She made the loyal, and partly Spanish, Theobald of Blaison seneschal of the politically sensitive Poitou. The important Angevin families of Craon and Des Roches supported the Capetians, as did the rich city of La Rochelle. Many of the great barons, too, were faithful, notably Stephen of Sancerre, John of Nesle, Amaury of Montfort and the counts of Blois and Chartres. The last two held their counties through their wives, the sister countesses Margaret of Blois and Isabella of Chartres, who were members of the Capetian family and cousins of Blanche herself.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#queens of france#louis ix#regents#thibault iv de champagne#pierre mauclerc#philippe ii#louis viii#frère guérin#mathieu ii de montmorency#and many more#regencies and troubles

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

Introduction du court-métrage “Rebellium” (œuvre fictionnelle coréalisée avec Amélie Laroche).

Travaux effectués : storyboard, illustration sur krita, animation sur After Effect et montage sur Première Pro.

Accompagnement musical de Thomas Thiebaud. Reprise de la composition de Guillaume de Machaut “Douce dame jolie”.

Synopsis:

Hiver 1229. Les barons dirigés par Pierre Mauclerc sont en révolte contre le Roi Louis IX et sa mère la Reine Blanche de Castille. Arthaud et Arnaud, chevaliers insurgés ont pour mission de garder la forteresse de Bellême afin de prévenir l'arrivée des troupes adverses. Le plan semble simple mais Arthaud rêve de gloire et ne peut se satisfaire de son poste. De plus en plus agacé par son ami qui lui vante les exploits légendaires du chevalier de Montmorency à Bouvines, il change d’objectif et décide de partir en quête d’ennemis à vaincre sans plus se soucier du reste. Arnaud arrivera t-il à faire revenir à la raison son coéquipier.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daughters of the Breton Dukes, part I

Judit, duchesse de Normandie. Daughter of Konan Iañ and Ermengarde-Gerberge d’Anjou. Mother of Aélis de Normandie, comtesse de Bourgogne and Aénor de Normandie, comtesse de Flandre. Grandmother of Adélaïde de Normandie, comtesse d’Aumale.

Hawiz, dugez Breizh. Daughter of Alan III and Berthe de Blois.

Berta, dugez Breizh. Daughter of Konan III and Maude FitzRoy. Mother of Konstanza Breizh, beskontez Roc’han and Enoguen Breizh, abbesse de St. Sulpice.

Konstanza, beskontez Roc’han. Daughter of Berta and Alan Penteur, 1st Earl of Richmond.

Konstanza, dugez Breizh. Daughter of Konan IV and Margaret of Huntingdon. Mother of Eleonora Breizh, the Fair Maid of Bretagne and Alis a Dhouars, dugez Breizh.

Eleonora, Countess of Richmond. Daughter of Konstanza and Geoffrey of England.

Alis, dugez Breizh. Daughter of Konstanza and Guy de Thouars. Mother of Yolanda Breizh, kontez Penteur.

Yolanda, kontez Penteur. Daughter of Alis and Pierre Mauclerc de Dreux. Mother of Alais de Lusignan, Countess of Gloucester; Marie de Lusignan, Countess of Derby; Isabelle de Lusignan, dame de Belleville; and Yolande de Lusignan, dame de Preaux.

Alis, comtesse de Blois. Daughter of Yann Iañ and Zuria Nafarroakoa. Mother of Jehanne de Châtillon, comtesse de Blois.

#bretagne#house of dreux#historyedit#french history#european history#women's history#history#royalty aesthetic#nanshe's graphics#medieval#bretoned

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

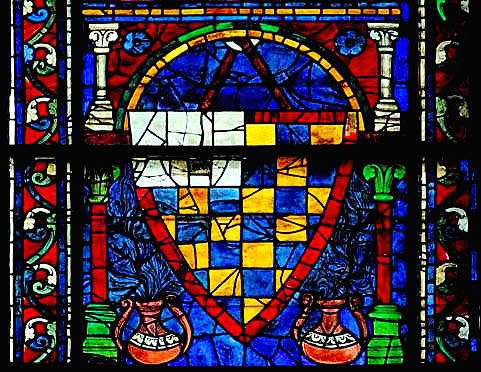

Dame Alix would be for us merely a name on a few timestained charters, the nebulous progenitrix of a noble line of Breton dukes, had she not married a man who while he may well have been a fond husband and devoted father, was certainly an ambitious and arrogant baron. But some fortunate mixture of affection, piety, and pride moved Peter to enshrine his family where he, his wife, and his two elder children would shine forth in varied colors from the lancet windows of the south transept of the cathedral of Chartres to rejoice the eyes of countless generations. In the lower part of the central lancet glow Peter's arms-alternate squares of blue and gold which designated the house of Dreux quartered with ermines which were Peter's personal insignia. The two lancets to the right of the center are occupied by Peter and John, those to the left by Alix and Yolande. Peter, kneeling in prayer in an armorial surcoat, looks far from comfortable and prepared for instant flight from his pious environment. As the feelings of a Christian martyr must have been very similar to those of Peter in prayer, it would be useless to probe the mind of the artist for his model. Peter looks unhappy-but so do the saints above him. Alix, John, and Yolande with their attending saints seem far more content.

-Sidney Painter, The Scourge of the Clergy: Peter of Dreux, Duke of Brittany

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

Alix of Thouars or Peter of Dreux for character bingo!

Alix:

Peter:

Send me a character for unhinged bingo night

#how about both? :D#there's an interesting paper that came out in 2019 about a lai Peter supposedly had written to give to Alix#i should get around to actually reading that in depth at some point...#i'm also hoping Desbordes' 2013 biography on Peter might have more on Alix but in terms of money I have no money :(#not to make it sound like i'm not interested in peter (i am. i need to study that unhinged man like a little bug)#but I'm also so desperate for anything on Alix beyond like genealogy#alix#pierre mauclerc

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Brother.

#they let him out of his enclosure and he immediately went rogue#>I betray the Lusignans >I profit >I then still keep Hugh of Lusignan's friendship for the rest of his life >reaping is for morons#pierre mauclerc#thirteenth century#The Scourge of the Clergy by Sidney Painter

0 notes

Text

HI????? HELLO?????

#🚨 PIERRE MAUCLERC IN MANGA 🚨 PIERRE MAUCLERC IN MANGA 🚨#Brittany Hanayome Ibun#thirteenth century#they made him so pointyyyy <3 (pierre was said to have a ''sharp appearance)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pierre de Dreux was present at the 1216 French invasion of England. Shakespeare was wrapping the play up at this point, but that would’ve made for a very entertaining pvp scene between Philip Bastard (unhinged) and Pierre Mauclerc (also unhinged).

#Pierre: take your filthy English paws off Richmond or I'll- I'll kill this audience member I'll do it I stg#Philip: Fine do it- do it see if I care. He's a groundling anyway#king john#histories

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thibaut le Chansonnier.

The present count of Champagne, Thibaut IV, is a poet. Guarded through his minority by his capable mother, Blanche of Navarre, Thibaut grew up to marry, one after the other, a Hapsburg, a Beaujeu, and a Bourbon princess, by whom he had eight children. To these children he added four more, products of his numerous love affairs. But the enduring passion of his life was a chaste one, owing to the inaccessibility of its object, the queen of France. This lady, Blanche of Castile, wife and widow of Louis VIII and mother of Louis IX (St.-Louis), was a dozen years Thibaut’s senior. Nevertheless Thibaut’s penchant for Blanche was such that he was suspected of poisoning her husband when the king died suddenly. The injustice of the accusation provoked Thibaut to join a couple of baronial troublemakers, Hugo of La Marche and Peter of Brittany, in a sort of antiroyal civil war. When on sober second thought Thibaut changed his mind, Hugo and Peter turned their spite against him and invaded Champagne, setting haystacks and hovels ablaze. Stopped by the walls of Troyes, they were forced to turn around and go home when a relieving force arrived, sent by Queen Blanche.

Partly as a result of the war, Thibaut was constrained to sell three of his cities—Blois, Chartres and Sancerre—to the king of France. At the last moment he felt a reluctance to hand over Blois, cradle of his dynasty, and carried stubbornness to the point of courting a royal invasion. But forty-six-year-old Blanche of Castile dissuaded thirty-three-year-old Thibaut in an interview of which the dialogue was recorded, or at least reported, by a chronicler:

Blanche: Pardieu, Count Thibaut, you ought to have remembered the kindness shown you by the king my son, who came to your aid, to save your land from the barons of France when they would have set fire to it all and laid it in ashes.

Thibaut (overcome by the queen’s beauty and virtue): By my faith, madame, my heart and my body and all my land is at your command, and there is nothing which to please you I would not readily do; and against you or yours, please God, I will never go.

Thibaut’s fancy for Blanche needed sublimation. Sage counselors recommended a study of canzonets for the viol, as a result of which Thibaut soon began turning out “the most beautiful canzonets anyone had ever heard” (a judgment in which a later day concurs). The verses of Thibaut the Songwriter were sung by trouvères and jongleurs throughout Europe. A favorite:

Las! Si j’avois pouvoir d’oublier

Sa beauté, a beauté, son bien dire,

Et son très-doux, très-doux regarder,

Finirois mon martyre.

Mais las! mon coeur je n’en puis ôter,

Et grand affolage

M’est d’espérer:

Mais tel servage

Donne courage

A tout endurer.

Et puis, comment, comment oublier

Sa beauté, sa beauté, son bien dire,

Et son très-doux, très-doux regarder?

Mieux aime mon martyre.

[Could I forget her gentle grace,

Her glance, her beauty’s sum,

Her voice from memory efface,

I’d end my martyrdom.

Her image from my heart I cannot tear;

To hope is vain;

I would despair,

But such a strain

Gives strength the pain

Of servitude to bear.

Then how forget her gentle grace,

Her glance, her beauty's sum,

Her voice from memory efface ?

I'll love my martyrdom.]

Frances & Joseph Gies- Life in a Medieval City

#xiii#frances & joseph gies#life in a medieval city#thibaut le chansonnier#thibaut iv de champagne#thibaut i de navarre#blanche de navarre#blanche de castille#louis viii#louis ix#hugues x de lusignan#pierre i de bretagne#pierre mauclerc#pierre de dreux

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

> Me and my son are summoned to the King of France

> I lie right to his face

> ???

> Profit

#he's such a piece of work. but also very funny.#pierre mauclerc#thirteenth century#The Scourge of the Clergy by Sidney Painter

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#asddfghjkl#dudes upon becoming duke consorts of brittany: i will now make myself everyone else's problem#pierre mauclerc

0 notes

Text

Les relations entre la Bretagne et la France au XIII siècle

Les relations entre la cour de Bretagne et celle de France de détériorent vite pendant le règne de Louis VIII (roi de France de 1223 à 1226 huitième de la dynastie dite des Capétiens directs) du fait du moindre prestige personnel du souverain et des menées occultes d’Henri III d’Angleterre. La disparition précoce de Louis VIII ouvre bientôt une période de régence, épreuve difficile pour la Couronne.

Pierre Mauclerc est écarté en 1237 quand le jeune duc Jean Ier arrive au pouvoir. Au chevalier aventureux et hardi succède un duc prudent et pacifique qui fera montre d’une fidélité sans faille à l’égard du roi capétien. Ses successeurs agiront de même : la Bretagne y gagne un siècle de paix mais perd alors toute influence diplomatique et voit son identité entamée. L’influence française se renforce en effet au XIIIe siècle. Faute d’une Université dans leur pays, les clercs bretons vont poursuivre leurs études supérieures à Angers, Orléans ou Paris.

0 notes

Text

Chronologie 1189-1514

Henri II meurt 1189

Constance remariée au vicomte d'Avranches

1196-contance prisonnière à Rouen

6 Avril 1199- Richard cœur de Lion meurt- lutte Jean sans Terre

Aliénor désigna Jean sans Terre, acceptée par les barons anglo-normands

1201-mort de Constance, Mère d'Arthur

1203- mort d'Arthur

Guy de Thouars

1206- la bretagne est passée de la tutelle anglo-normand à celle des Français. "le seigneur Philippe, roi de France, tient en main propre toute la Bretagne"

Henri II Plantagenet rendait le nantais a la Bretagne, lie de façon définitive ce grand compté méridional au duché: avec lui nait la Bretagne historique.

1206 - l'armée royal entre en Bretagne et prend Nantes.

1213 - mariage d'Alix de Thouars et Pierre de dreux

1222 - réunion du duché de bretagne et du Penthièvre

1237- Pierre de Mauclerc cède le duché à son fils, Jean Ier. Pierre mourra au retour de la croisade d’Egypte de Saint Louis

1237-1286 règne de Jean le Ier (Jean le Roux) duc prudent et pacifique. Le développement économique du duché s’affirme.

1246- les cordeliers s’installent à Nantes

1270- les assises ducales se tiennent à Nantes

1286-1305 - Règne de Jean II, compte de Richemont et duc de Bretagne

1294- Jean II prend parti pour le roi d’Angleterre et commande l’armée anglaise en Guyenne, avant de se rapprocher de la France.

1297- Phillipe le bel élevé la Bretagne au rang du duché-pairie : le duc de Bretagne devient ainsi l’égal d’une poignée de hauts feudataires, les « pairs de France ».

1303 - Mort d’Yves Hélori (saint Yves)

1305-1312 Jean II se rend au couronnement du pape Clément V, décède à Lyon. Règne d’Arthur II, duc de Bretagne.

1308- Saint Malo constitue une éphémère communauté de ville

1312-1341 - Règne de Jean III (Jean le Bon) épithète gage de stabilité et de paix. Le duc se comporte en fidèle soutien du roi de France. Il adopte pour armes les hermines pleines, qui symbolisent, en héraldique, pureté (par sa robe blanche) et majesté.

1328- Le roi de France Charles IV le Bel décède sans héritier direct. Phillipe VI de Valois, fils de Charles de Valois et neveu de Phillipe le Bel, est choisi comme roi au détriment d’Edouard III d’Angleterre, petit-fils de Phillipe le Bel par sa mère Isabelle. Edouard II, qui est duc d’Aquitaine, sûr de son bon droit, refuse de prêter l’hommage au roi de France pour la Guyenne en tant que duc d’aquitaine. Finalement, face à la pression française, il accepte de venir à Amiens prêter le fameux serment, mais avec des réserves concernant des terres détachées au duché de Guyenne par Charles IV.

1337- Excédé par les interventions persistantes de Philippe VI en Guyenne, Eduard III annule son hommage au souverain capétien et revendique la couronne de France, déclenchante la guerre de Cent Ans. Jean III, duc de Bretagne, vassal des deux rois rivaux à cause de ses tenures en France et en Angleterre, n’engage pas directement son duché dans le conflit.

1341- Mort de Jean III sans héritier.

La Guerre de Succession (1341-1365)

1341- la Bretagne est devenue champ de bataille pour la guerre de Cent Ans. L’armée royal fait le siège de Nantes où Jean de Montfort s’est laissé enfermer. La ville capitule le 21 novembre. Le duc prisonnier est envoyé sous escorte à Paris.

1342- Jean de Flandre accepte une aide d’Angleterre. Le 19 octobre, Eduard III débarque à Brest pour entamer une campagne dans le duché de Bretagne. Le port et ses environs seront tenus par les Anglais jusqu’en 1397.

1342- une trêve est conclue le 19 Janvier à Malestroit. Charles de Blois tient Rennes et Nantes et domine toute la Haute-Bretagne et le littoral nord. Edouard quitte la Bretagne, emmenant Jeanne et ses enfants. Le roi de France fait arrêter et exécuter.

1344- Charles de Blois entre en Bretagne à la tête d’une armée. Assiège Quimper puis Guérande.

1347- Charles de Blois est fait prisonnier à Vannes puis L’Angleterre. La Bretagne est comprise dans la trêve de Calais. La Guerre démure suspendue durant les quatre années suivantes.

1348-1350- Grande Peste noire en occident. La Bretagne fut relativement peu touchée.

1350- assassinat de Thomas Dagworth le chef des troupes Anglais en Bretagne. Mort de Phillipe VI de Valois. Jean II lui succède.

1352- La guerre ouverte reprend.

1356-1357- Long siège de Rennes (octobre-juillet) mené par le duc de Lancastre. Accompagné du compte Jean de Montfort, âgé de seize ans. En Aout 1356, Charles de Blois est libéré contre la promesse d’une énorme rançon de 700 000 florins d’or.

1360- traité de Brétigny entre la France et l’Angleterre. Concernant la Bretagne, les deux rois s’engagent à ménager un accord entre les deux prétendants. Mais Jeanne de Penthièvre, épouse de Charles de Blois, s’oppose à tout partage.

1362- Edouard III remet ses pouvoirs à Jean de Montfort.

1364- le 29 septembre. Charles de Blois meurt à la Bataille d’Auray. Jean de Montfort se retrouve seul duc de Bretagne.

1365- conclusion de la Paix. Traité de Guérande. Fin de la Guerre de succession

1366- Jean IV duc de Bretagne

1373- Bertrand de Guesclin, au service du roi de France, passe en Bretagne et rallie Nombre de Bretons à sa bannière. Le connétable contraint Jean IV à l’exil en Angleterre. Charles V ordonne la saisie du duché.

1378- une petite flotte anglaise débarque à Brest. En décembre, Charles V confisque officiellement le duché et le rattache à la couronne de France.

1380- Mort de Charles V et de Bertrand de Guesclin.

1389- Trêve entre la France et l’Angleterre.

1396- Trêve de 28 ans entre la France et l’Angleterre.

1399- Mort de Jean IV.

1402- La duchesse Jeanne épouse Henri IV. Jean V est couronné à Rennes à l’âge de douze ans.

1407- Trêve avec l’Angleterre (renouvelée en 1409, 1411,1415,1417).

1420- Marguerite de Clisson épouse Jean de Penthièvre. Attire Jean V sur ses terres et le fait prisonnier (13 février) Il est libéré en juillet. Les Penthièvre sont exilés et leurs terres confisquées. Le pouvoir ducal sont renforcé de l’épreuve.

1422- Mort de Charles VI.

1442- Mort de Jean V. Son fils François lui succède.

Règne de François I (1442-1450)

1451- Pierre II institue la prééminence des neuf baronnies aux états de Bretagne.

1457- Oncle de François Ier et de Pierre II, Arthur III réaffirme l’indépendance du duché malgré son office de connétable.

1458- mort d’Arthur. Lui succède François II, âgé de vingt-trois ans.

1459- couronnement de François II, acclamé par les Rennais. Il s’établit à Nantes, qui devient la capitale du duché. 1460- ouverture d’une université à Nantes.

1461- début du règne de Louis XI, qui considère le duc de Bretagne comme un vassal qu’il faut soumettre.

1464-Francois II accueille les grands révoltés contre Louis XI.

1466- Pierre Landais inspire la politique extérieure du duc : renforcer l’indépendance bretonne ; multiplier les alliances contre le roi de France.

1471-Mariage de François II et Marguerite de Foix

1471-1473- Reprise de Guerre avec la France, sur les marches.

1481- François II signe un traité d’alliance et d’amitié avec Maximilien d’Autriche, puis avec Edouard IV d’Angleterre (il comporte un projet de mariage entre le prince de Galles et l’héritière présomptive du duché, Anne).

1483- Mort de Louis XI. La régente, Anne de Beaujeu, poursuit la politique de son père contre le duc de Bretagne, au nom de Charles VIII.

1486- Les états de Bretagne font serment de reconnaitre Anne comme duchesse. Mort de Marguerite de Foix, mère d’Anne.

1487- traité de chateaubriant entre Charles VIII et les grands seigneurs bretons révoltés.

1488- Anne devient duchesse de la Bretagne.

1489- La guerre reprend avec la France. Couronnement d’Anne dans la cathédrale de Rennes. Traité de Francfort entre Charles VIII et Maximilien d’Autriche. Le traité est ratifié par Anne le 3 décembre.

1490- Anne conclut un mariage par procuration avec Maximilien d’Autruche le 19 décembre.

1491- Alain d’Albret, prétendant éconduit d’Anne de Bretagne, livre Nantes à la France. Rohan occupe de la Basse-Bretagne au nom du roi. Les troupes françaises menacent Rennes. Anne se résout à épouser Charles VIII. L’union est célébrée le 16 décembre dans la chapelle de Langeais. Anne a cédé à son époux tous les droits sur le duché et elle s’interdit de révoquer cette donation par testament au cas où elle mourrait avant le roi.

1492- couronnement d’Anne de Bretagne à Saint-Denis (8 février). Le 7 juillet, Charles VIII reconnait les privilèges de la Bretagne. Un traité est signé à l’Etaples entre Charles VIII et Henri VII. Le roi d’Angleterre reconnait le fait accompli en Bretagne.

1493- Charles VIII supprime la chancellerie de Bretagne.

1498- Mort de Charles VIII à Amboise (8 Avril). Le 19 août, Anne s’engage à Epouser Louis XII en cas d’annulation du mariage de ce dernier avec Jeanne de France. Elle fait son entrée solennelle à Nantes le # Octobre.

1499- Mariage d’Anne de Bretagne et de Louis XII (janvier). Le contrat préserve l’indépendance de la Bretagne.

1505- Anne effectue un Tour de Bretagne « Tro Breizh » triomphal. Qui signifie le double attachement des Bretons à la duchesse-reine et à la liberté bretonne qu’elle symbolisait.

1510- Naissance de Renée de France, deuxième fille d’Anne de Bretagne.

1514- Mort d’Anne de Bretagne (9 Janvier).

(Cornette, Histoire de la Bretagne 2005)

0 notes