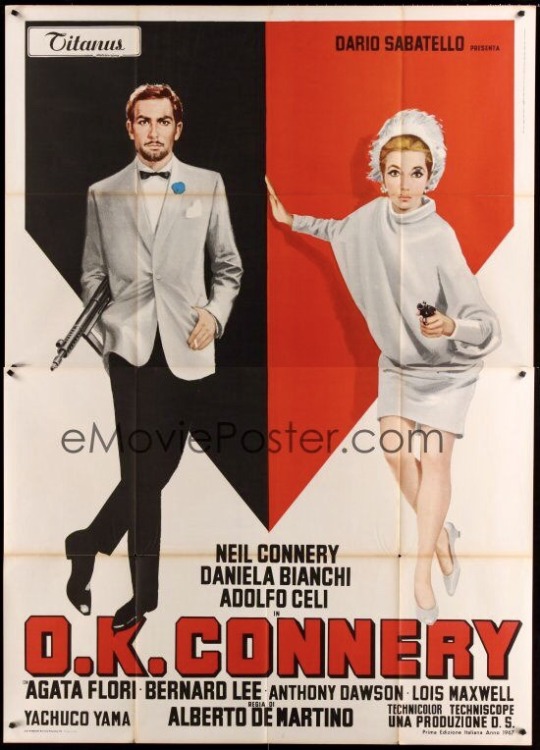

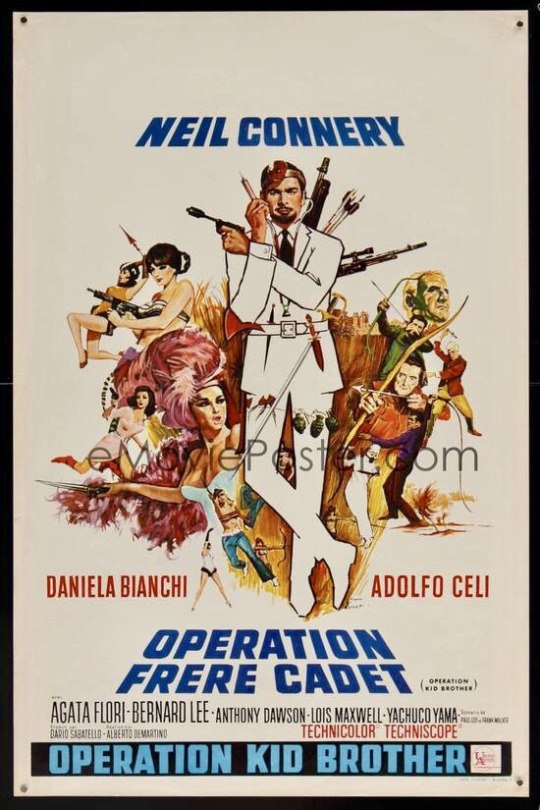

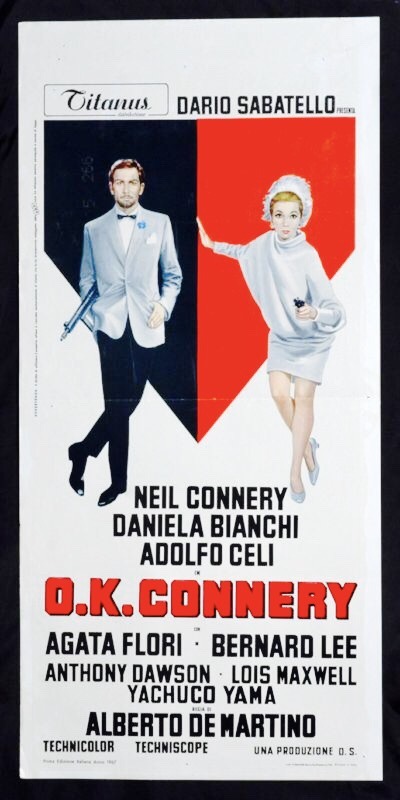

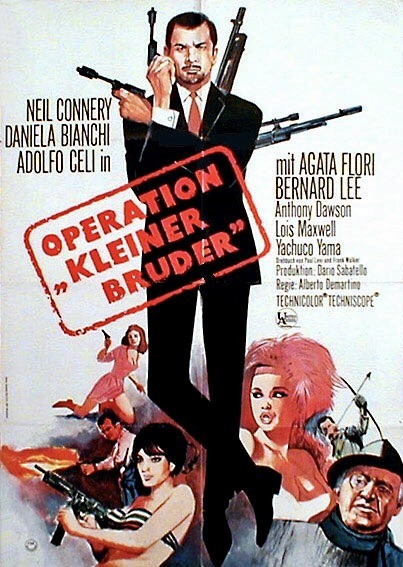

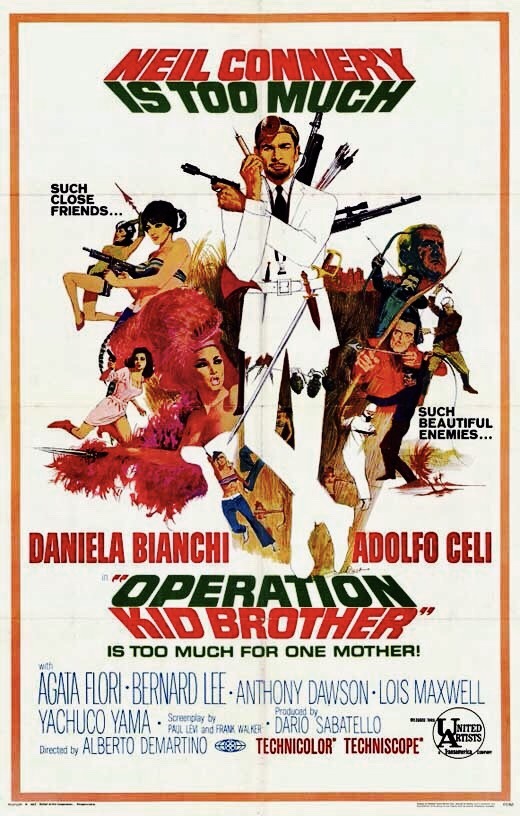

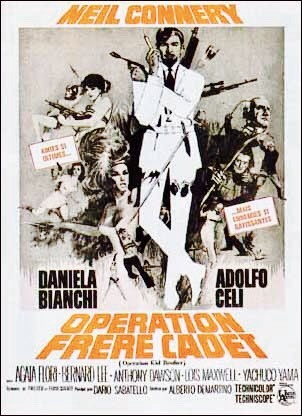

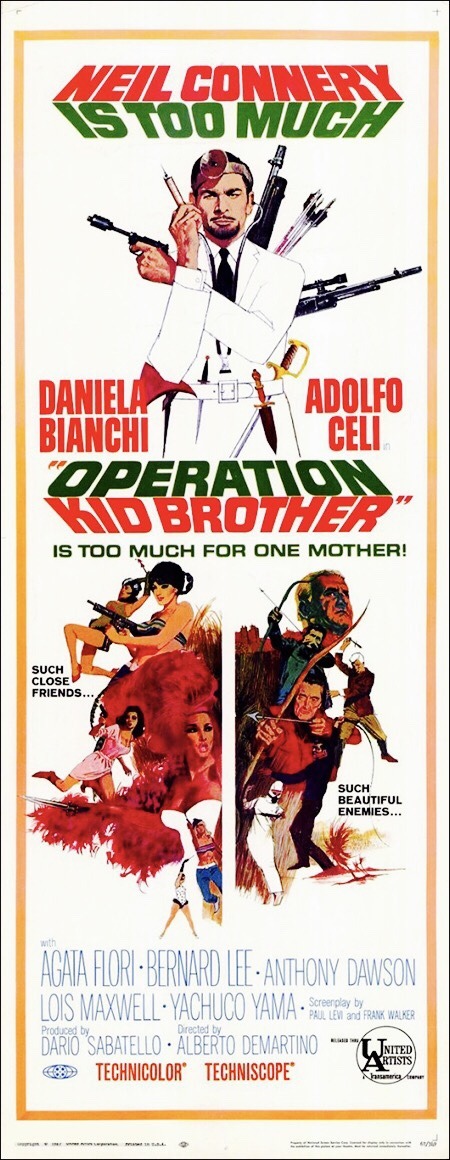

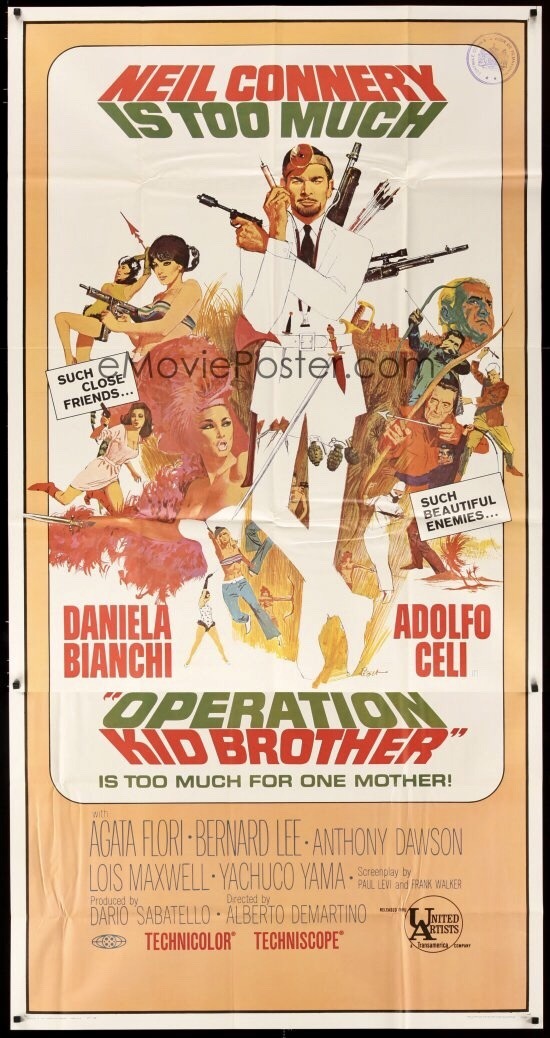

#operation frere cadet

Photo

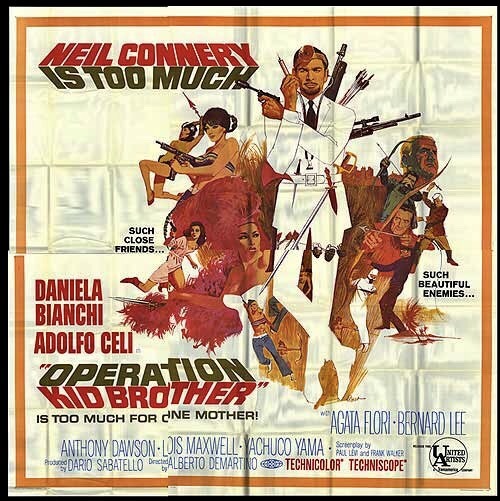

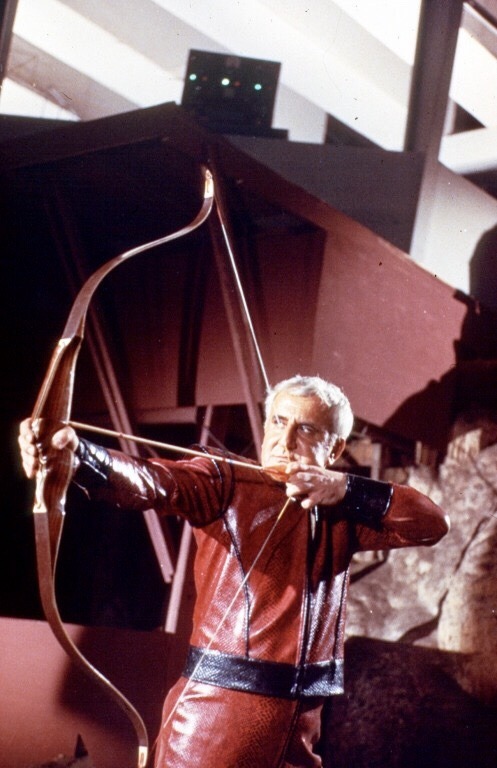

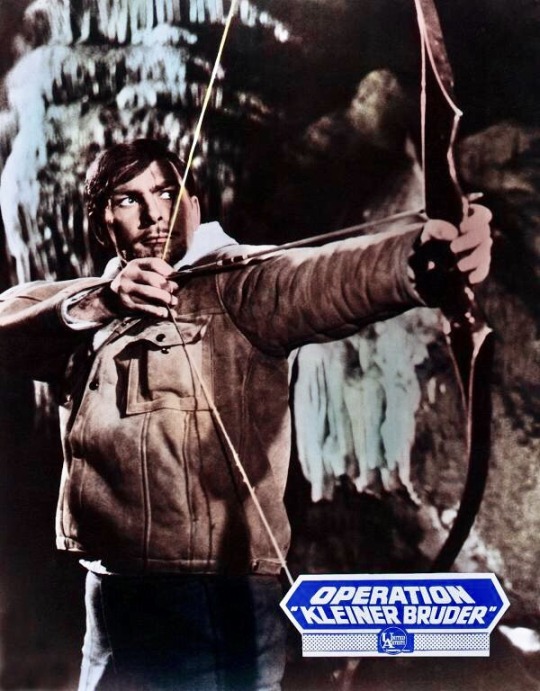

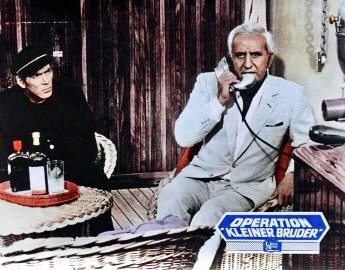

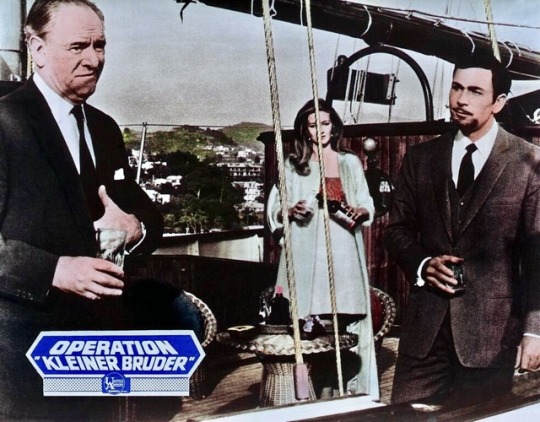

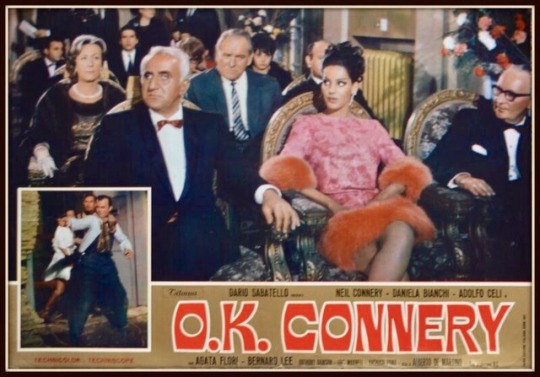

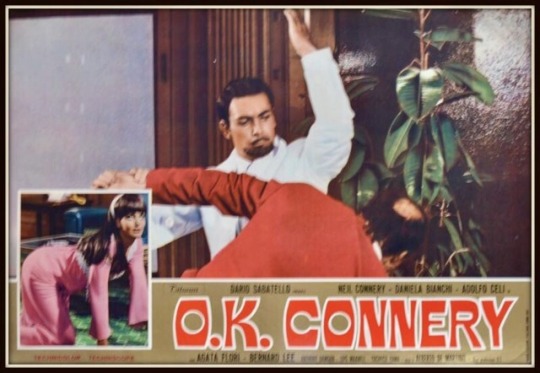

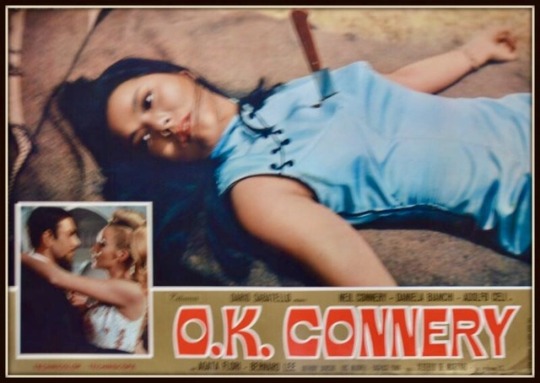

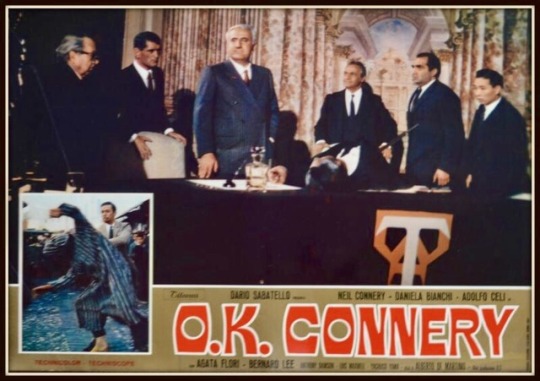

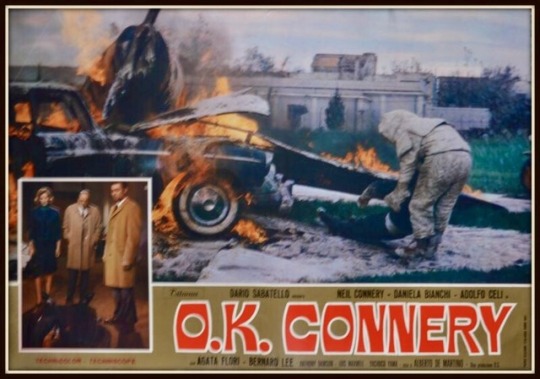

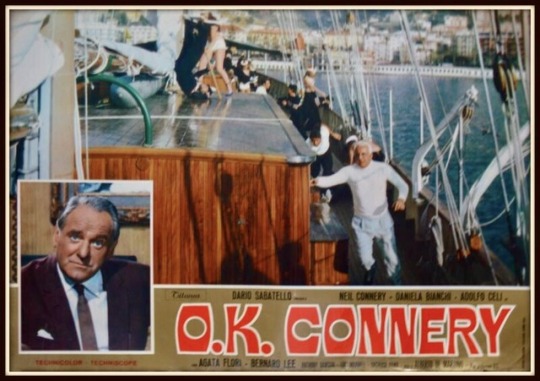

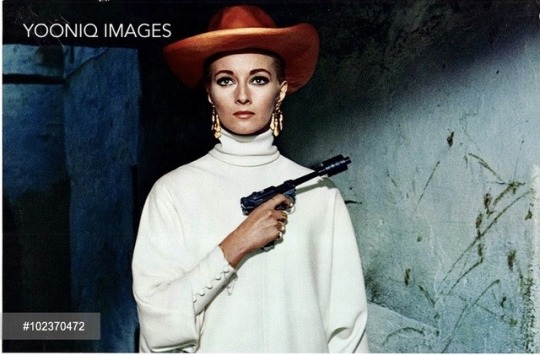

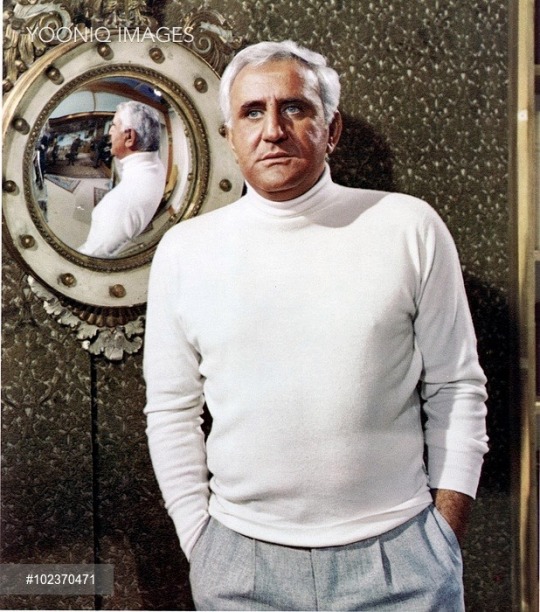

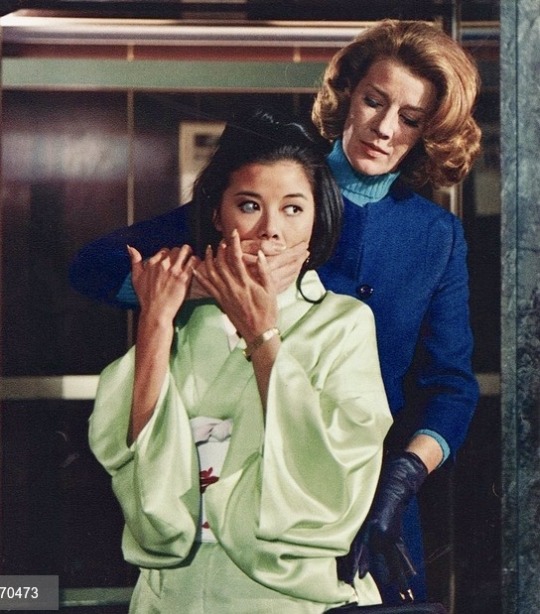

1967 (Very Rare THAI Poster ) OK Connery Also Known As (AKA) Operation Double 007 Secret Agent 00 Brazil Operação Irmão Caçula Colombia Operación hermano menor Denmark Operation Lillebror Spain Todos los hermanos eran agentes Finland Operaatio 'Pikkuveli' France Opération frère Cadet Greece (transliterated) Sta ihni tou adelfou tou Ireland (English title) Operation Kid Brother Italy (alternative spelling) O.K. Connery Japan Dokutâ Konerî/Kiddo Burazâ sakusen Mexico Operación hermano menor USA (informal short title) Kid Brother USA Operation Kid Brother West Germany Operation 'Kleiner Bruder' Directed by Alberto De Martino Music by Ennio Morricone & Bruno Nicolai Writing Credits Paolo Levi ... (story) Paolo Levi ... (screenplay) Frank Walker ... (screenplay) Stanley Wright ... (screenplay) Stefano Canzio ... (screenplay) Release Dates Italy 20 April 1967 USA 22 November 1967 (New York City, New York) Japan 2 March 1968 Finland 26 April 1968 West Germany 26 April 1968 UK May 1968 Denmark 29 May 1968 France 28 June 1968 Ireland 12 July 1968 Mexico 17 July 1969 Finland 1 April 2007 (Night Visions Film Festival) Cast Neil Connery Neil Connery ... Dr. Neil Connery Daniela Bianchi Daniela Bianchi ... Maya Rafis Adolfo Celi Adolfo Celi .. Mr. Thai - 'Beta' Agata Flori Agata Flori ... Mildred Bernard Lee Bernard Lee ... Commander Cunningham Anthony Dawson Anthony Dawson ... Alpha Lois Maxwell Lois Maxwell ... Max Yachuco Yama Yachuco Yama ... Yachuko Franco Giacobini Franco Giacobini ... Juan 🎬🇮🇹 #okconnery #operationkidbrother #operationfrerecadet #neilconnery #danielabianchi #adolfoceli #albertodemartino #enniomorricone #brunonicolai #italianspy #spymovie #eurospy #007 #seanconnery #spaghettispy #giallofever #giallo ##spionistico #cultmovies #italiancultmovie

#ok connery#operation kid brother#neil connery#daniela bianchi#adolfo celi#alberto de martino#bruno nicolai#operation frere cadet#spy movie#spy movies#eurospy#spionaggio#promo poster#art poster#poster movie#thai poster

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to Bacon & the Art of Living

The quest to understand how great bacon is made takes me around the world and through epic adventures. I tell the story by changing the setting from the 2000s to the late 1800s when much of the technology behind bacon curing was unraveled. I weave into the mix beautiful stories of Cape Town and use mostly my family as the other characters besides me and Oscar and Uncle Jeppe from Denmark, a good friend and someone to whom I owe much gratitude! A man who knows bacon! Most other characters have a real basis in history and I describe actual events and personal experiences set in a different historical context.

The cast I use to mould the story into is letters I wrote home during my travels.

Eskort Ltd.

October 1960

Over the years I have written letters to my kids telling them what I learn and about my experiences. They followed my quest to produce the best bacon on earth through these monthly communications. When I returned home I found that they kept every letter. When they were here last December, the gave me the draft of a book where they are including every letter. They even contacted Dawie and Oscar who both sent them my mails. They asked me to write the introduction to every county and the “Union Letters” as they called the letters I sent them from Cape Town.

I asked them if I can add three accounts of companies who achieved perfection in the large-scale production of bacon. This is the first of the three good examples of people who achieved what I sought. I think that for a time at Woody’s we achieved the same and when Duncan and Koos took over, things took a dip, but they are recovering beautifully. What makes this an insanely exciting story is the fact that Wynand Nel, the legendary production manager of Eskort is a good friend!

These stories begin much in the same way. A very close tie with England. A young nation that is trying to find its place in the global village; visionary farmers and politicians and one man who made all the difference!

Background

In the Natal Midlands, on the banks of the Boesmans river lays the largest bacon plant in South Africa, that of Eskort Ltd.. A few months ago I visited Wynand at the factory. I was 30 minutes early and instead of reporting to reception, I decided to drive a few hundred meters further and up the hill, right next to the bacon plant to Fort Dunford. The Fort is situated exactly 500m apart with the bacon plant nestled between the Boesmans River and the Fort.

It was built by Dunford in response to the Langalibalele Rebellion in 1873. The location of the old military site at Bushmans River drift, overlooked by Fort Dunford is where the Voortrekker leader Gert Maritz originally set up camp along the river.

The curator, Siphamandla, saw me driving up. I was the only visitor and he came running up to give me a proper welcome. I told him I will be at Eskort but when we are done, I’m coming back to see the Fort.

While waiting in reception at Eskort, I took a photo of a stone that was laid by J. W. Moor in 1918. He was the first chairman of “The First Farmers Co-Operative Bacon Factory Erected in South Africa”, the Eskort factory. I was intrigued!

I saw Wynand, visited the Fort briefly and was on my way back to Johannesburg. As soon as I got home I started digging through piles of information on the subject of Eskort and an amazing story emerged. All the information was firing through my mind as connections started to form between the new facts I learned and old history. When I finally fell asleep, I kept waking with every new connection made. Bits of information jolted me from deep sleep to a light slumber. Here is what I discovered.

Introduction

The origins of the Eskort Bacon factory is tied up with the story of the development of the Natal Midlands in the mid-1800s to the early part of the 1900s. It is embedded in the broader context of the existence of a very strong English culture in Natal. The Natal colony was created on 4 May 1843 after the British government annexed the short-lived Boer Republic of Natalia. A unique English culture continued. This bacon factory became one of the cornerstones of the creation of a meat industry in South Africa and contributed materially to the establishment of a meat curing culture in the country. The historical importance is seen in the fact that the South African roots of large scale industrial meat curing are English and not German.

The broader international context of its establishment in a cooperative can be traced back to Peter Bojsen who created the first cooperative abattoir and bacon curing plant in the world in Horsens, the Horsens Andelssvineslagteri, in 1882 in Denmark. By 1911 the first such cooperative factories were built in England, namely the St. Edmunds Bacon Factory, modeled in turn after the factory at Horsens. The 1918 development in Estcourt, Natal would, no doubt, have been a continuation of the model.

In terms of curing technology, the bacon plant produced its bacon in the most sophisticated way available at the time, using the same techniques employed by the Harris Bacon operation of Calne in Wiltshire. Following WW1, its curing techniques progressed from the Wiltshire process of the Harris operation (and through Harris, to Horsens where the technique was developed) to the direct addition of sodium nitrite to curing brines through the work of the legendary Griffiths Laboratories.

The great benefit of the dominant English culture of the Natal Midlands was in the fact that they had access to the Harris operation in Calne and the St. Edmunds Bacon Factory more so than the fact that the English population of the Midlands could have provided a possible market for their bacon. The population in Natal at the time and even in South Africa remained relatively small and the goal of creating such a sophisticated operation was to export.

In terms of access to local markets, I have little doubt that they relied heavily on the Imperial Cold Storage and Supply Company Ltd. of Sir David de Villiers Graaff (1859 – 1931) who was a contemporary of JW Moor (1859 – 1933). They were born a mere 6 months apart with David in March 1859 and John (JW Moor) in September of the same year.

One can say that David with his Imperial Cold Storage and Supply Company in Cape Town was a follower of Phillip Armour in Chicago with the establishment of refrigerated rail transport and cold storage warehouses throughout Southern Africa (just as Phil Armour did in the US). David probably met Phil in Chicago in the mid-1880s and possibly again in the early 1890s, who, in all likelihood, showed him his impressive packing plant and gave him the idea of refrigerating railway carts. John (JW) Moor, on the other hand, was in technical detail and broad philosophy, a follower of the Dane, Peter Bojsen in his creation of the first farmer’s coop for slaughtering and production of bacon and its marketing in England and the English operations of C & T Harris with their Wiltshire bacon curing techniques.

The location of the plant in Estcourt is in all likelihood closely linked to the existence of Fort Dunford and the close association with the military of the Moor family as is evident not only through the heritage of their grandfather but through their close involvement in the schooling system and the introduction of cadet training. The possible involvement of the Anglo Boer war hero, Louis Botha is fascinating.

The context of its creation is, more than anything, to be understood by two realities. One was the first World War. The second, the Moor family of Estcourt with a wider lens than a focus on JW Moor. To understand the Moor family, we must understand their heritage and how they came to South Africa.

Immigrating to South Africa

Immigration back then was done as it is today, through entrepreneurs who made money by facilitating movement to the new world and who sell their products through colourful displays and exciting tales of success and a new life. Between 1849 and 1852, almost 5000 immigrants arrived in Natal through the various schemes. One such an agent was Joseph Byrne who chartered 20 ships to ferry passengers to Natal between 1849 to 1851. One of the 20 ships was the Minerva which set sail on 26 April 1850 with 287 passengers from London. A festive atmosphere must have prevailed on the voyage to Natal and the promise of a new life. (Dhupelia, 1980)

On 4 July 1850, they arrived in Durban and the Minerva was wrecked on a reef below the Bluff. All occupants and cargo ended up overboard. Two of the passengers aboard were Sarah Annabella Ralfe who was traveling with her family and Frederick William Moor. (Dhupelia, 1980)

Romance and Settlement

F.W. Moor lifted the young Sarah Annabella Ralfe from the waters and carried her to the safety of the shore. It is not known if they were romantically involved before this event but romance bloomed afterward and the couple was married in June 1852. (Dhupelia, 1980) They settled in the Byrne valley which Byrne cleverly included in the total package he was selling back in England.

The Moors and the Ralfes were interested in sheep farming and the wet conditions at Byrne, close to Richmond were not favourable. In 1869 F.W. Moor moved to a farm Brakfontein, on the Bushman’s River at Frere close to Estcourt. Here the conditions were more suitable. “The farm was some five miles (8 km) south-west, of Estcourt and he obtained it from the Wheeler family in settlement of a debt. This farm has some historical interest. It was the site of the Battle of Vecht Laager in 1838 when Zulu impi of Dingaan clashed with the Voortrekkers who had settled there. It was on this farm that F.R. Moor and his wife settled on their return to Natal, his father having moved to Pietermaritzburg. Moor and his wife stayed for some years in a house built by the Wheelers until he built a larger house which he called Greystone. It was on this property that Moor’s seven children were born and it was here that he carried out his adventurous farming activities.” (Morrell, 1996)

Sara and FW, in turn, had 5 children. Two of these were F. R. Moor, born on 12 May 1853 in Pietermaritzburg and J. W. Moor born in September 1859 in Estcourt.

Strong Military Traditions

The Moor family had strong military connections going back to the father of F.W. Moor (FR and JW’s grandfather). FW was the youngest son of Colonel John Moor. Col Moor was an officer in the Bombay Artillery in the service of the British East India company. FW was born in Surat in 1830 and returned to England on the death of his father. “He and his mother settled first in Jersey and later in Hampstead while he trained to be a surveyor and, not entirely satisfied with his position in England, he decided to emigrate to Natal.” (Dhupelia, 1980) His mother followed him to Natal and passed away in 1878 on the farm of FW, Brakfontein, aged 85. (The Freeman’s Journal, Dublin, Dublin, Ireland; 18 Oct 1878)

The military connection of the Moor family is highlighted when one considers that when FR Moor was in high school, he and other students considered it desirable that the school should have a cadet corps. FR attended the Hermannsburg School situated approximately 15 miles (24 km] from Greytown and founded in the early 1850s by the Hanoverian Mission Society.

Moor, as a senior student at the school, was deputed to write to the Colonial Secretary seeking permission for the school to initiate the movement. Permission was granted and in 1869 a cadet corps of 40 students, between the ages of 14 and 18 years, was formed with a teacher, Louis Schmidt, as the captain and 16 years old F. R. Moor and John Muirhead as the first lieutenants.

Moor thus played a role in the establishment of the cadet movement and in giving Hermannsburg School the distinction and honour of being the first school not only in Natal but in the British Empire to have a cadet corps. Though the Hermannsburg cadet corps lasted only until 1878 its example was followed by Hilton College and Maritzburg High School in 1872. Yet another pupil of this first boarding school in Natal who was to make a name for himself in politics and was to be later closely associated with Moor was Louis Botha.” (Dhupelia, 1980)

Initial Capital

The Moor family became one of the large landowners in the Natal Midlands. Some of these families brought wealth from England and some, as was the case with the Moor family, made their money in other ways. The two most likely ways to make a fortune in those days were in Kimberley on the diamond fields or riding transport between Durban and Johannesburg.

After school, in 1872, the young FR Moor went to Kimberly to make his fortune. JW was still in school when FR left for the diggings where he remained for 7 years. The 19-year-old Moor made his first public speech on behalf of the diggers while in Kimberley “standing on a heap of rubble”. “Later he was twice elected to the Kimberley Mining Board which consisted of nine elected members representing the claim holders for the purpose of ensuring the smooth and effective running of the mines and diggings. This experience probably gave him confidence as well as experience in public affairs.” (Dhupelia, 1980) He later served as Minister of Native Affairs between 1893–1897 and 1899–1903. He became the last Prime Minister of the Colony of Natal between 1906 and 1910.

“While FR Moor was in Kimberley he met Cecil John Rhodes, another strong personality with outstanding qualities of leadership. There is some indication that the two men were closely associated during these years for the Moor and Rhodes brothers belonged to an elite group of 12 diggers who were teasingly named “the 12 apostles” and who associated with each other because of their common interests. Moor’s daughter, Shirley Moor, claims that her father would not have associated with Rhodes for he disliked him and in the 1890’s he abhorred Rhodes’ role in the Jameson Raid and held him responsible to a certain extent for the Anglo-Boer war of 1899.” (Dhupelia, 1980)

“After Moor got married, he felt that there was no security in remaining in the fields. He consequently sold his claims to his brother George, and returned to Natal in 1879 to take up farming has been very successful financially at the diamond fields.” (Dhupelia, 1980)

Dhupelia states that FR was “later joined (in Kimberley) by two of his three brothers.” As far as I have it, he had only two brothers with his siblings being George Charles Moor (whom we know took his diggings operation over); Annie May Chadwick; John William Moor and Kathleen Helen Sarah Druwitt. (geni.com) If both brothers joined him, this would mean that JW also spent time on the diggings. (This needs to be corroborated.) It would explain why JW shared in the wealth that his brother obtained in Kimberley.

Success in Farming

FR’s success in farming-related to JW, the main focus of our investigation, in that they conducted many of their farming activities as joint ventures. This is why I suspect that JW joined FR for a time on the diggings. Morrell (1996) states that “Moor displayed a considerable initiative and a pioneering spirit in his farming activities, making a name for himself as had his father who was one of the first in the colony to introduce imported Merinos from the valuable Rambouillet stock in France. Estcourt was one of the four villages in Weenen County and most farmers kept cattle, sheep, and horses. By 1894 Moor, in partnership with his brother J.W. Moor, was engaged in farming ventures over an area of 20 000 acres [8097,17 ha]. Their stock consisted of 6000 to 7000 sheep and they were among the largest breeders of goats in Natal possessing 1200 goats. Moor, in fact, acquired the first Angora goats in Natal where the interest in the mohair industry was considerable in the 19th century. In addition to the sheep and goats, Moor engaged in ostrich farming, for he believed there was a good market for the sale of ostrich feathers. He also kept horses and cattle and imported Pekin ducks.” (Morrell, 1996)

The British Market in Crisis

Walworth reported that by 1913 in the UK, “imported bacon had largely secured the market.” This was according to him one of the reasons for a rapid decline in the pig population with a 17% reduction in numbers from 1912 to 1913. (Walworth, 1940) Conditions in 1917 and 1918 were desperate in the UK with meat supply falling by as much as 30%. Stock availability, increased prices, and war rationing all played a role. Canada responded to the shortage of pork in 1917 and their export of bacon and ham increased from 24 000 tonnes to 88 000 tonnes in 1917. Corn was in short supply during the war, but it was in reaction to meat shortages that rationing was finally introduced in the UK in 1918. (Perren) The 1918 situation related to bacon in England was reported on by The Guardian (London, Greater London, England), 6 July 1918. The meat situation was generally better than it has been in a while. In the article, they report that Bacon is being imported into the country in large quantities and that the import “will be maintained at the same rate throughout the year.” It is interesting that the article also reports that “the intention is to build up a big reserve Bacon in cold storage for later use.” (The Guardian, 1918, p6) The entire article oozes with planning and deliberateness happening in the background.

It is clear that the two countries well-positioned to respond were Canada and South Africa. New Zealand was focussing on exporting frozen meat, as was Australia. Walworth leaves the South African response to bacon shortages out (except one comment that South Africa was one of the countries that eventually responded) but it is clear from the Estcourt case that the response was there.

The immediate context of the establishment of the bacon company is the war but in the early 1900s, the pork industry in the UK was in a bad state in terms of industrializing the process of bacon production. Producers were unable to compete in price or quality with imports. The reasons are interesting. Much of the curing in the UK was done by small curing operations or farmers who used dry curing. A large variety of pig breeds made it difficult. Small volumes or a large variety of bigs vs a large variety of a standard pig – the latter suits an industrial process. Fat was highly prized in many of the curing techniques, as it is to this day, but for lard to be cured takes a year. Again, it does not fit the industrial model. The main reason for high-fat content in bacon was due to imports from America who generally produced a much fatter pig on account of its diet. (Perren)

Market trends moved away from fat bacon and a leaner pig was required which the UK farmers were unable to deliver in the volumes required. The consumers also called for a milder bacon cure that we achieved with the tank curing method. The predominant way that bacon was cured in the UK was still the dry curing which resulted in heavily salted meat.

In April 1938, at the second reading of the Bacon Industry Bill before the British Parliament, the minister of Agriculture Mr. W. S. Morrison summarised the conditions in the bacon market in the UK pre-1933 as follows. “As far as the curers (in the UK) are concerned, lacking the proper pig as they did, and a regular supply, they could not achieve the efficiency in large-scale production and the economies which were within the power of their foreign competitors. Nor could they achieve adaptation to the changed taste of the public, and the change in taste was, indeed, largely the result of the foreign importation.” The change of taste he was talking about was a movement away from fatty bacon to lean bacon and a milder cure (less salty). The solution in terms of the fatty bacon was to breed less fatty pigs but the UK market failed to deliver such pigs. My suspicion is that this was not due to a technical inability or ignorance of the British farmers, but due to the deeply entrenched nature of the specialized, small scale dry-curing operations. Having gotten to know butchers from the UK, now in their 70’s, who stem from such traditions, I understand that they hold their trade in such high esteem that they would rather amputate a limb than compromise the dry curing traditions they were schooled in.

The fact is that for whatever reason, the UK pork and bacon market pre-1933, was fragmented and Morrison stated that “the factories in this country worked to a little more than half of their capacity with consequent high costs. The cheaper and quicker process of curing bacon (i.e. tank curing) made little headway and the whole industry was in a very weak position to stand competition even of a normal character.”

In response to the enormous size of the UK bacon market and the inability of local curers to convert to tank curing, foreign curers moved aggressively to fill the void. This aversion of the British to convert from dry curing to tank curing did not disappear after the war and would continue to be the basis of bacon exports into the UK following 1918 when the war ended. Mr. Morrison continued that “what was in store for the industry was not competition of a normal character. In the years 1929 to 1932, there ensued a scramble for this bacon market.” “In 1932 the importation rose to 12,000,000 cwts. or more than twice as much as it had been in the five-year period preceding the War.”

The British market started to respond after major government programs to change the bacon production landscape in the UK and tank curing was adopted to a large extent. Even though I have little doubt that the potential to export to England was a major driving factor in the creation of the company, as it was in Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Canada, and the USA, a further mention must be made of the very robust local bacon market. An interesting comment is made in an article published in The Gazette (Montreal, Canada) 24 January 1916. In an article entitled “Trade for Canada in South Africa” the comment is made about bacon that ���good business can be worked up in Canadian bacon brands if attention is paid to the packaging.” The first interesting point to take from this comment is that the demand for bacon in South Africa by 1916 was sizable and, secondly, that the standard of packaging was very high, pointing to high technical competency.

Agricultural Operations and the Establishment of a Bacon Cooperative

Back in Natal, farmers saw the benefit of various forms of cooperation precisely due to their small numbers and the fact that cooperation gave them access to larger markets and more stable prices. The children growing up in the Natal Midlands were encouraged after completing their schooling, to join one of the many farmers’ associations (FA). “The “reason for being” of these agricultural societies was to hold stock sales. As Nottingham Road’s James King (founder member of the LRDAS in 1884) said. “The worst drawback was the lack of markets”. (Morrell, 1996). It was this exact issue that JW addressed with his bacon cooperative.

“Their function was thus primarily marketing and their fortunes were generally judged by the success or failure of sales. The sale of stock differs markedly from that of maize (the product which sparked the cooperative movement in the Transvaal). In Natal. the market was very localised with local butchers and auctioneers generally dealing with farmers in their area.” (Morrell, 1996)

“A variety of factors increased the importance of cattle sales particularly in the late and early twentieth century. Catastrophic cattle diseases, particularly Rinderpest (1897-1898) and East Coast Fever (1907-1910) reduced herds dramatically making it all the more important for farmers to realise the best prices available for surviving stock. The number of cattle in Natal was reduced from 280 000 in 1896 to 150000 in 1898. This amounted to a loss of £863 700 to farmers.” (Morrell, 1996)

“It was only in the area of stock sales (sheep, cattle and to a lesser extent, horses) that cooperative marketing operated. Foreign imports began to undercut local products, particularly once the railway system was developed. In 1905, on behalf of the Ixopo Farmer Association, Magistrate F E Foxon objected to the government allowing imported grain.” (Morrell, 1996)

In other domains (such as dairy and ham products), cooperative companies were formed. These were joint stock companies, generally headed by prominent and prosperous local farmers (JW Moor and George Richards of Estcourt, for example), who raised capital from farmer shareholders. The members of the Board were generally the major shareholders. Farmers who joined were then obliged to supply the factory/dairy with produce, in return for which they got a guaranteed price and, If available, a dividend.” (Morrell, 1996) This was the basis of the operation of the Farmers’ Cooperative Bacon Factory.

“The small size of the local market put pressure on farmers to export. The capacity of Natal’s manufacturing industries was minuscule. It began to expand around 1910 yet by 1914 there were no more than 500 enterprises in the whole colony.” “So it happened that many prominent farmers were also directors of agricultural processing factories.” (Morrell, 1996)

Generally, it seems that as FR’s political involvement increased, his attention to farming decreased and he relied increasingly more on JW to take care of their farming interests. JW himself was politically active, but never to the extent of FR. JW Moor became MP for Escort while he was director of Natal Creamery Limited and Farmers’ Cooperative Bacon Factory.”

It is interesting that, as was the case around the world, pork farming followed milk production. This was what spawned the enormous pork industry in Denmark and to a large extent, sustains the South African pork farming industry to this day.

“It was Joseph Baynes, a Byrne settler and dairy industry pioneer who established a milk processing plant in Estcourt under the name of the Natal Creamery Ltd. where JW was a director. “This factory was located adjacent to the railway station. Baynes died in 1925 and in 1927 the factory, which by this time was owned by South African Condensed Milk Ltd. was bought by Nestlés. Today the factory produces Coffee, MILO and NESQUIK.” (Revolvy)

In 1917 a group of farmers, including JW Moor, met in Estcourt to discuss the establishment of a cooperative bacon factory. The Farmer’s Co-operative Bacon Factory Limited was founded in August 1917 and the building of the factory started. When the plant opened its doors, it was done on 6 June 1918 by the Prime Minister General Louis Botha. We can not overstate the massive symbolic nature of the leader of a country in the midst of war opening a food production facility.

The products were marketed under the name Eskort. It takes about a year to get a factory up and running and it was no different in the plant in Natal. When they were ready to supply the UK, the war was over but not the shortages. In 1919 the factory started exports to the United Kingdom. The honour went to the SS Saxon who carried the first bacon from the Estcourt plant exported to the United Kingdom, in June 1919. The products were well received.

A fire in 1925 caused significant damage to the factory. Production was relocated to Nel’s Rust Dairy Limited in Braamfontein, Johannesburg while renovations were being done at the plant. Despite this, the company still won the top three prizes at the 1926 London Dairy Show. (openafrica.org)

They were ready with streamlined efficiency when the second World War broke out and supplied over one million tins of sausages to the Allied forces all over the world and over 12 tonnes of bacon weekly to convoys calling at Durban harbour. (Revolvy) “Early in 1948 plans for a second factory in Heidelberg, Gauteng, were drawn up and the factory commenced production in September 1954.” (openafrica.org) In “1967 the Eskort brand was the largest processed meat brand in South Africa. In 1998 the company was converted from a cooperative to a limited liability company.” (Revolvy)

An interesting side note must be made here. This is the story of my travels to Denmark and the UK to learn how to make the best bacon on earth. The purpose of the venture was to export the bacon and supply the Imperial Cold Storage and Supply Company. The similarity of what we did to prepare for our own bacon production in Woodys and how the bacon plant in Estcourt came about is striking. To raise capital for the venture we relied on investors and I rode transport between Johannesburg and Cape Town. Without any knowledge of JW Moor, by simply looking at the Southern African context of the late 1800s and early 1900s, their course of action was logical. (2)

Technological Context

The technical aspects behind the curing technology employed at the new plant are of particular interest. The establishment of the operation in 1918 placed it right in the transition time when science was unlocking the mechanisms behind curing and an understanding developed (beginning in 1891) that it was not saltpeter (nitrate) that cured meat, but nitrite.

The second technical fact of interest was the form of cooperation that was chosen to house the bacon plant. From Denmark to England farmers saw the benefit of the cooperative model to solve the problem of “access to markets” and this was no different in South Africa.

Tank Curing or using Sodium Nitrite

In terms of curing brines, the scientific understanding that it was not saltpeter (nitrate) curing the meat, but somehow, nitrite was directly involved came to us in the work of Dr. Edward Polenski (1891) who, investigating the nutritional value of cured meat, found nitrite in the curing brine and meat he used for his nutritional trails, a few days after it was cured with saltpeter (nitrate) only. He correctly speculated that this was due to bacterial reduction of nitrate to nitrite. ( Saltpeter: A Concise History and the Discovery of Dr. Ed Polenske).

What Polenski suspected was confirmed by the work of two prominent German scientists. Karl Bernhard Lehmann (1858 – 1940) was a German hygienist and bacteriologist born in Zurich. In an experiment, he boiled fresh meat with nitrite and a little bit of acid. A red colour resulted, similar to the red of cured meat. He repeated the experiment with nitrates and no such reddening occurred, thus establishing the link between nitrite and the formation of a stable red meat colour in meat. (Fathers of Meat Curing)

In the same year, another German hygienists, one of Lehmann’s assistants at the Institute of Hygiene in Würzburg, Karl Kißkalt (1875 – 1962), confirmed Lehmann’s observations and showed that the same red colour resulted if the meat was left in saltpeter (potassium nitrate) for several days before it was cooked. (Fathers of Meat Curing)

This laid the foundation of the realisation that it was nitrite responsible for curing of meat and not saltpeter (nitrate). It was up to the prolific British scientist, Haldane (1901) to show that nitrite is further reduced to nitric oxide (NO) in the presence of muscle myoglobin and forms iron-nitrosyl-myoglobin. It is nitrosylated myoglobin that gives cured meat, including bacon and hot dogs, their distinctive red colour and protects the meat from oxidation and spoiling. (Fathers of Meat Curing)

Identifying nitrite as the better (and faster) curing agent was one thing. How to get to nitrite and use it in meat curing was completely a different matter. Two opposing views developed around the globe. On the one hand, the Irish or Danish method favoured “seeding” new brine with old brine that already contained nitrites and thus cured the meat much faster. (For a detailed treatment of this matter, see The Naming of Prague Salt) The Irish and the Danes took an existing concept at that time of the power of used brine and instead of a highly technical method of injecting the meat and curing it inside a vacuum chamber, a simple system using tanks or baths to hold the bacon and regularly turning it was developed which became known as tank curing.

The concept of seeding the brine did not develop from science around nitrite, but preservation technology that was a hot topic in Ireland’s scientific community at the beginning and middle of the 1800s. Denmark imported tank curing or mild curing technology in 1880 from Ireland where William Oake invented it sometime shortly before 1837. Oake, a chemist by profession developed the system which allowed for the industrialisation of the bacon production system. (Tank Curing was invented in Ireland)

A major revolution took place in Denmark in 1887/ 1888 when their sale of live pigs to Germany and England was halted due to the outbreak of swine flu in Denmark. The Danes set out to accomplish one of the miracle turnarounds of history by converting their pork industry from the export of live animals to the production of bacon (there was no such restriction on the sale of bacon). This turnaround took place in 1887 and 1888. They used the cooperative model that worked so well for them in their abattoirs namely the cooperative.

They were amazingly successful. In 1887 the Danish bacon industry accounted for 230 000 live pigs and in 1895, converted from bacon production, 1 250 000 pigs.

One would expect that the Irish system of curing was imported to Denmark then. This is however incorrect. The first cooperative bacon curing company was started in Denmark in 1887. Seven years earlier, in 1880, the Danes visited Waterford and “taking advantage of a strike among the pork butchers of that city, used the opportunity to bring those experts to their own country to teach and give practical and technical lessons in the curing of bacon, and from that date begins the commencement of the downfall of the Irish bacon industry. . . ” (Tank Curing was invented in Ireland)

This is astounding. It means that they had the technology and when the impetus was there, they converted their economy. It also means that Ireland not only exported the mild cure or tank curing technology to Denmark but also to Australia, probably through Irish immigrants during the 1850s and 1860s gold rush, between 20 and 30 years before it came to Denmark. Many of these immigrants came from Limerick in Ireland where William Oake had a very successful bacon curing business. Many came from Waterford. A report from Australia sites one company that used the same brine for 16 years by 1897/ 1898 which takes tank curing in Australia too well before 1880 which correlates with the theory that immigrants brought the technology to Australia in the 1850s or 1860s.

Tank curing or mild curing was invented without the full understanding of nitrogen cycle and denitrifying and nitrifying bacteria and the chemistry of nitrite and nitric oxide. Brine consisting of nitrate, salt and sugar were injected into the meat with a single needle attached to a hand pump (stitch pumping). Stitch pumping was either developed by Prof. Morgan, whom we looked at earlier or was a progression from his arterial injection method. (Bacon Curing – a historical review and Tank Curing Came from Ireland)

The meat was then placed in a mother brine mix consisting of old, used brine and new brine. The old brine contained the nitrate which was reduced through bacterial action into nitrite. It was the nitrite that was responsible for the quick curing of the meat.

Denmark was, as it is to this day, one of the largest exporters of pork and bacon to England. The wholesale involvement of the Danes in the English market made it inevitable that a bacon curer from Denmark must have found his way to Calne and I am the one who told John Harris about the new Danish system and implemented it at their Calne operation. (Bacon Curing – a historical review)

A major advantage of this method is the speed with which curing is done compared with the dry salt process previously practiced. Wet tank-curing is more suited for the industrialisation of bacon curing with the added cost advantage of re-using some of the brine. It allows for the use of even less salt compared to older curing methods. (Bacon Curing – a historical review)

Corroborating evidence for the 1880 date of the Danish adoption of the Irish method comes to us from newspaper reports about the only independent farmer-owned Pig Factory in Britain of that time, the St. Edmunds Bacon Factory Ltd. in Elmswell. The factory was set up in 1911. According to an article from the East Anglia Life, April 1964, they learned and practiced what at first was known as the Danish method of curing bacon and later became known as tank-curing or Wiltshire cure. (Bacon Curing – a historical review)

A person was sent from the UK to Denmark in 1910 to learn the new Danish Method. (elmswell-history.org.uk) The Danish method involved the Danish cooperative method of pork production founded by Peter Bojsen on 14 July 1887 in Horsens. (Horsensleksikon.dk. Horsens Andelssvineslagteri)

The East Anglia Life report from April 1964, talked about a “new Danish” method. The “new” aspect in 1910 and 1911 was undoubtedly the tank curing method. Another account from England puts the Danish system of tank curing early in the 1900s. C. & T. Harris from Wiltshire, UK, switched from dry curing to the Danish method during this time. In a private communication between myself and the curator of the Calne Heritage Centre, Susan Boddington, about John Bromham who started working in the Harris factory in 1920 and became assistant to the chief engineer, she writes: “John Bromham wrote his account around 1986, but as he started in the factory in 1920 his memory went back to a time not long after Harris had switched over to this wet cure.” So, early in the 1900s, probably between 1887 and 1888, the Danes acquired and practiced tank-curing which was brought to England around 1911. (Bacon Curing – a historical review)

The power of “old brine” was known from early after wet curing and needle injection of brine into meat was invented around the 1850s by Morgan and others. Before the bacterial mechanism behind the reduction was understood, butchers must have noted that the meat juices coming out of the meat during dry curing had special “curing power”. It was, however, the Irish who took this practical knowledge, undoubtedly combined it with the scientific knowledge of the time and created the commercial process of tank-curing which later became known as Wiltshire cure when the Harris operations became the gold standard in bacon curing. Their first factory was located in the English town of Calne, in Wiltshire from where the method came to be known as Wiltshire cure. Its direct ancestor was however Danish and they, in turn, capitalised on an Irish invention. (Bacon Curing – a historical review)

It is of huge interest that the Eskort brand of bacon, to this day, bears the brand name of Wiltshire cure. Wiltshire is an English county where Calne is located which housed the Harris factory. (C & T Harris and their Wiltshire bacon cure – the blending of a legend) There is no doubt in my mind that the same curing was practiced in Estcourt in 1918, as was done in the Harris factories in Calne and that this is the historical basis for the continued reference on the Eskort bacon packages as Wiltshire Cure.

At a time before the direct addition of nitrite to curing brines, the only two ways to cure bacon was either dry curing or tank curing. Dry curing requires about 21 days as against 9 days for tank curing. The Bacon Marketing Scheme officially established tank curing in the UK. (Walworth, 1940)

It would not have been possible for the plant to use sodium nitrite in its brine in 1918. Where the Danes and the English favoured tank curing, the Germans and the Americans liked the concept of adding nitrite directly to the curing brines. This was however frowned upon due to the toxicity of sodium nitrite. In America, the matter was battled out politically, scientifically and in the courts. It became the standard ingredient in bacon cures only after WW1. The Germans used it during the war due to a lack of access to saltpeter (nitrate) which was reserved for the war effort and the need to produce bacon faster to supply to the front. The American packing houses in Chicago toyed with its use due to the speed of curing that it accomplishes.

The timeline, however, precludes its use in the Bacon factory in Estcourt in 1918. In fact, Ladislav Nachtmulner, the creator of the first legal commercial curing brine containing sodium nitrite, only invented his Prague Salt, in 1915. Prague Salt first appeared in 1925 in the USA as sodium nitrite became available through the Chicago based Griffith Laboratories in a curing mix for the meat industry. (The Naming of Prague Salt)

In Oct 1925 in a carefully choreographed display by Griffith, the American Bureau of Animal Industries legalised the use of sodium nitrite as a curing agent for meat. In December of the same year (1925) the Institute of American Meat Packers, created by the large packing plants in Chicago, published the document. The use of sodium Nitrite in Curing Meats. (The Naming of Prague Salt)

A key player suddenly emerges onto the scene in the Griffith Laboratories, based in Chicago and very closely associated with the powerful meatpacking industry. In that same year (1925) Hall was appointed as chief chemist by the Griffith Laboratories and Griffith started to import a mechanically mixed salt from Germany consisting of sodium nitrate, sodium nitrite and sodium chloride, which they called “Prague Salt.” (The Naming of Prague Salt)

Probably the biggest of the powerful meat packers was the company created by Phil Armour who gave David de Villiers Graaff the idea of refrigerated rail transport for meat. More than any other company at that time, Armour’s reach was global. It was said that Phil had an eye on developments in every part of the globe. (The Saint Paul Daily Globe, 10 May 1896, p2) He passed away in 1901 (The Weekly Gazette, 9 Jan 1901), but the business empire and network that he created must have endured long enough to have been aware of developments in Prague in the 1910s and early ’20s. (The Naming of Prague Salt)

Drawing of David de Villiers-Graaff in his mayoral robes. The drawing appeared in a newspaper in Chicago on 11 April 1892 when he was interviewed at the World Exposition. He traveled to Chicago the first time in the mid-1880s when he probably met Armour.

There is, therefore, no reasonable way that the bacon factory in Estcourt could have used sodium nitrite directly in 1918. If Armour’s relationship was with JW Moor, this could have been a possibility since I suspect that Armour was experimenting with the direct addition of nitrite to curing brines as early as 1905, but his relationship, if any, would have been with David de Villiers Graaff who was a meat trader at heart and did not have any direct interest in a large bacon curing company until ICS acquired Enterprise and Renown, long after the time of David de Villiers Graaff (the 1st). Besides this, where would they have found cheap nitrite salts in South Africa in 1918? This takes the 1918 establishment of the company back to the technology used by the Harris family in Calne which was mother brine tank curing, the classic Wiltshire curing method which was later exactly defined in UK law.

At the demise of the Harris operation, many of the staff were taken up into the current structures of Direct Table which is, according to my knowledge, one of the only remaining companies in the world who still use the traditional Wiltshire tank curing method for some of its bacons. It undoubtedly is the largest to do so. In the Eskort branding of its bacon, the reference to Wiltshire cure it is a beautiful reference back to the origins of the company which pre-dates the direct addition of sodium nitrite.

The Griffith Laboratories became the universal prophet of the direct addition of nitrite to curing brines. They appointed an agent in South Africa in Crown Mills. Crown Mills became Crown National and Prague Powder is still being sold by them to this day. It could very well have been Crown Mills who converted Eskort from traditional tank curing to the direct addition of sodium nitrite through Prague Powder.

It must be mentioned that the butchery trade was well established in South Africa long before the cooperative bacon factory was established in Estcourt. Bacon curing was one of the first responsibilities of the VOC when Van Riebeek set the refreshment station up in 1652. Swiss, Dutch, German and later, English butchers were scattered across South Africa. The largest and most successful of these companies in Cape Town was Combrink and Co., owned by Jakobus Combrink and later taken over by Dawid de Villiers Graaff who changed the name to the Imperial Cold Storage and Supply Company. I suspect that most of these operations used dry curing which was not suitable for mass production.

Peter Bojsen and cooperative Bacon Production

The second technical aspect is the form of cooperation that was established and a few words must be said about Peter Bojsen for those who are not familiar with him. Cooperative bacon production was the buzz word in the early 1900s, but where did this originate?

It started in Denmark. The Danes were renowned dairy farmers and producers of the finest butter (Daily Telegraph, 2 February 1901: 6) They found the separated milk from the butter-making process to be excellent food for pigs. The Danish farmers developed an immense pork industry around it. (Daily Telegraph, 2 February 1901: 6) The bacon industry was created in response to a ban from England on importing live Danish pigs to the island. The Danish farmers responded by organising themselves into cooperatives who build bacon factories that supplied bacon to the English market. (Daily Telegraph, 2 February 1901: 6) This established bacon curing as a major industry in Denmark.

“On 14 July 1887, 500 farmers from the Horsens region joined forces to form Denmark’s first co-operative meat company. The first general meeting was held, land was purchased, building work commenced and the equipment installed.” (Danishcrown.com) “On 22 December 1887, the first co-operative abattoir in the world, Horsens Andelssvineslagteri (Horsen’s Share Abattoir), stood ready to receive the first pigs for slaughter.” (Danishcrown.com) The first cooperative bacon curing company was also established in 1887. (Tank Curing came from Ireland)

The dynamic Peter Bojsen (1838-1922) took center stage in the creation of the abattoir in Horsens. He served as its first chairman. He created the first shared ownership slaughtering house. In years to follow, this revolutionary concept of ownership by the farmers on a shared basis became a trend in Denmark. Before the creation of the abattoir, he was the chairman of the Horsens Agriculture Association and had to deal with inadequate transport and slaughtering facilities around the market where the farmers sold their meat at. (Horsensleksikon.dk. Horsens Andelssvineslagteri) Peter was a visionary and a creative economist. The genius of this man transformed a society.

In 1911, the St. Edmunds cooperative bacon factory was opened in England in Elmswell, with Danish help. It is clear that the concept of the Horsens plant crossed the English channel. It is plausible that its creation reached the ears of a group of farmers in a very “British” part of the empire, in Estcourt, Natal not just with the Wiltshire Tank curing of the Harris operation, but the cooperative movement in bacon production from St. Edmunds in 1911.

Early Success for Eskort

An article appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney, New South Wales), 2 June 1919, p7 entitled “On Land, Livestock in South Africa – Further Competition for Australia.” The article reports on pork production that “pig breeding has been taken up systematically and while in the year before the war imports of bacon and hams were valued at GBP368,112, last year they were reduced to GBP31,590, and there is good reason to think that soon these articles will be exported.” One may think that the reduction in import is due to the war and that in general South African producers were stepping up to the plate to fill the void, but the trend of the article is that something is happening “systematically” and there is a trend that projects that soon the GBP368,112 import figure will completely be supplied by South African producers and that surplus bacon will be exported.

The farmers cooperative were founded in 1917 in Estcourt. Moor laid the cornerstone in January 1918, the report in the Sydney Morning Herald appeared in June 1919, the same month when the first exports of Eskort bacon to the UK took place. Export may have taken place before the local market was completely saturated. Regardless of the actual circumstances, the export of bacon to the UK was not just a major achievement and competing nations took notice. I also suspect that Eskort managed to supply a sizable portion of the 1913 import figure of GBP368,112 in 1918 and that the article may elude to exactly this.

Pulling the Military Connections Together

The location of the Estcourt plant is of interest virtually right next to Fort Dunford, between the fort and the Bushmans river. My suspicion is that the land belonged to the army and that Moor, either JW or with the help of FR, secured rights to purchase it. This could have been done only by a family who had very cozy relationships with the military and had friends in high places in the persons of Louis Botha and FR Moor himself.

Fort Dunford is indicated with the red marker. Take note of the position of the Boesmans River, the Eskort plant, the Fort and the Hospital.

Just look at the defenses of the Fort. There were three defenses. The first would have been the Bushmans river. Secondly, there was a moat around the fort, 2 meters deep and 4 meters wide. Then, one part of the staircase could be pulled up in case two of the defenses were bridged. It is clear from the map that even the hospital was strategically located to be within the general protection of the Fort and the Boesmans River bend.

There is a second interesting contribution that the military post could have made to the establishment of the bacon plant. It is known that men from Elmswell and Wiltshire were drafted into service in South Africa. Could it have been that some of these men actually worked at the cooperative bacon plant in Elmswell? These records can quite easily be checked and will be worth the effort.

Strong circumstantial evidence, however, points to more than just a coincidental relationship between the location of the plant and the military establishment. Probably more important than the affinity of Moor family for the military was the fact that FR Moor was the political leader of the Natal colony until the Union of South Africa was created in 1910 and the fact that the old school friend of FR, General Louis Botha was in 1918, the Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa. Whichever way you look at it, it is hard not to recognise the close proximity of the Eskort plant to the military installations. What could be the uniting thought that pulls all these facts together? (Of course, in part, predicated on the fact that the factory is in the original location)

Looking at the state of the British Empire and wartime circumstances in the UK, I believe offers the answer. The military context goes much deeper than schoolboy comradery, family nostalgia or friends in high places. 1918 was the beginning of the last year of the Great War. On the one hand, it is hard for us to imagine the unified approach that the Empire had towards the war and every citizen in every Empire country. The empathy and support that the war elicited in South Africa generally, but especially in Natal, so closely linked with the UK in spit and culture was enormous. One source reports that in Estcourt school staff subscribed a portion of their salary monthly to the Governor-General’s Fund in support of the war. (Thompson, 2011) It is outside the scope of this article to delve deeper into the unprecedented effort that was being expended by the South African population and the people in Natal in particular in support of the troops but reading the accounts of what was being done in Natal is quite emotional.

On the other hand, directly responding to wartime shortages in the UK was an international effort. Bacon, in those days, was not just a luxury. It was staple food. The production of bacon was a matter of national importance debated in parliament. It was a key food source sustaining the British navy. Many people only had bacon as food every day. They would boil the bacon before eating it. The parents who had to work the next day had the actual meat and the kids only had the water. Eduard Smith made the remark in his landmark work, Foods (1873), that in this way both the parents and the children went to bed “with a measure of satisfaction.” Bacon had strategic importance to the military and in the first world war, spoke to the general food situation in war-ravaged England.

The fact that the bacon company was established in Estcourt in 1917 shows clearly that South Africa was ready to step in to prop up meat and bacon supply in particular to the UK. Was there direct involvement from the South Africa leader, General Louis Botha who possibly passed on a request from London to all Empire states to assist in the supply of meat and bacon in particular? It is a matter of conjecture, but a tantalising possibility. These are speculations that can be corroborated by looking at the correspondence of Botha. FR Moor himself had direct communication with London and Botha may have simply opened the factory in support of the idea. FR’s letters along with that of JW have to be scrutinised for leads. The one reason that makes me suspects that there may have been a direct request from Botha or some early support for the venture is the location of the factory, right next to the Fort. In my mind, it swings the possibility for direct involvement from Botha from possible to probable. (Facts from correspondence should solve the matter)

Supplying the British market may have been done to build up South Africa, just as much as it was done in support of the Empire. I suspect that the former may even be more of a driving force than the latter. On 13 June 1917, an article appeared in the Grand Forks Herald (Grand Forks, North Dakota), reporting from London that “Developments on an enormous scale are expected in South Africa after the war and plans in this connection are being made as regards the export of food. It is confidently predicted that so far as meat is concerned the Union will be in a position to compete very soon with any other part of the world and in order to assist the expansion of the industry all the steamship lines propose, it is understood, to increase their refrigerated space very considerably and to place more vessels in service.” This report came out in the year when the Cooperative bacon Company in Estcourt was formed. It oozes with deliberateness and purposefulness from the highest authorities.

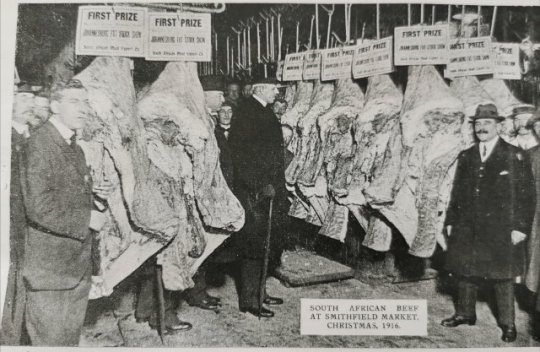

One person who was clearly involved in the “deliberateness and purposefulness” becomes clear from a pamphlet that was published in that same year. In a document dated 12 Jan 1917 about the South African meat export trade, compiled by A. R. T. Woods to Sir Owen Phillips, chairman of the Union Castle Line who by this time was carrying meat from South America to Europe in their Nelson Line of Steamers, the following interesting quite is given by Gen. Louis Botha. The background is the delivery of what is described in the document as “by universal consent,. . . probably the best specimen of South African meat (beef) yet placed upon the London market” delivered by the R. M. S. “Walmer Castle” to the Smithfield market in London and inspected by a group from South Africa featured below in 1914. (I will give much to know the names of the men below. Will there be the name of one JW Moor?)

The party traveled to London by invitation from The Hon. W. P. Schreiner, High Commissioner of South Africa and Mr. Ciappini (the Trades Commissioner). The South African meat was deemed comparable to frozen meat produced in any part of the world. The letter was a motivation that the South African meat trade was mature enough to be taken seriously and some helpful advice was given based on experience in South America.

He quotes Gen. Louis Botha who advised farmers that “so far as mealies are concerned the export should not develop, but that the mealies should be used to feed stock in this country, and that the export should be in the form of stock fed in South Africa on South African Mealies.” There is, therefore, good evidence of Genl. Louis Botha involving himself in the details of the establishment of the meat trade from South Africa and, I believe that it is in part this general encouragement that JW Moor followed in creating the Cooperative Bacon Curing Company in 1917.

I located this pamphlet among documents in the Western Cape Archive of J. W. Moor and his farmers Cooperative where they apply for permission to erect an abattoir and a bacon curing company in East London on the harbour. It is interesting that one of the recommendations given in the pamphlet is that abattoirs and chilling factories be erected in Ports, “along the quays where the ocean-going refrigerated steamers load” as it was done in Argentina. The influence of Botha’s encouragement on Moor can be well imagined.

The application for the abattoir was lodged in 1917, the same year when the Farmer’s Co-operative Bacon Factory Limited was founded in August 1917. It is possible that members of the Natal Farmers Co-operative Meat Industries and the Farmer’s Co-operative Bacon Factory Limited were the same people. Or that the one owned the other. Whichever way you look at it, John Moore was a key figure in both and the establishment of a bacon company in East London was directly in line with the proposals set out to boost meat exports. It is very interesting that both occurred in 1917 and that only the Eskort factory survived. As someone who established such a venture myself, my initial thoughts were that having a curing company at two such geographically distant sites as East London and Estcourt would have been impossible to manage, especially since both were new ventures. Further documents show that the factory was built on the proposed site and it is telling that only the Estcourt site survived.

East London’s harbour at the mouth of the Buffalo River. In the absence of facilities ashore, the vessel SV Timaru, fitted with cold chambers, was moored here by the East London Cold Storage Company for an extensive period early in the 20th century. (From Ice Cold in Africa). The businesses of David de Villiers Graaff and Moor were intertwined and mutually dependant.

The stone in Estcourt was unveiled by JW Moor on Jan 7, 1918, almost a full year before the Armistice. The Farmer’s Co-operative Bacon Factory Limited was founded in August 1917, 16 months before the end of the War. The factory was opened on 6 June 1918 by the Prime Minister General Louis Botha, 6 months before the Great War ended. This is remarkable.

The shortages in the UK in 1917 and 1918 were dire. The end of the war was not in sight and calls went out across the Empire to assist. Meat supply, at this time, diminished with 30% in the UK. In this context, it is easy to see how military land was either made available or that it would have been strategically prudent to locate such an installation close to a military site, but again, it would have required high-level support (involvement?).

For the South Africans, the call for help would have been close to home. Delville Woods took place in 1916, a year before the company was created. In the month when it was founded, August 1917, Lieutenant-General Sir Jacob Louis van Deventer had just taken over command of the mostly South African troops involved in the German East African campaign. His offensive started in July 1917. The entire East African region remained very active for the duration of the war.

When the fighting was all done almost 19 000 South Africans lost their lives. The madness of the time can best be described by the opening sentences of Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities. It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair… Such would have been the experience of the men and women involved in the war while setting up the Farmer’s Co-operative Bacon Factory on the banks of the Boesmans River in Estcourt, Natal. (1)

Finally

The Eskort factory is a historical site where many interesting cross-currents meet. Its uninterrupted existence from a time before nitrite was directly added to brine makes it unique in the world! Apart from Danish Crown and Tulip, I know of very few other companies.

Besides this, tied up in the story of its creation is a romantic immigrant, a family, defining themselves through diamond digging and making powerful friends; re-investing its fortunes in farming and establishing a food company that exists to this day. We see the use of tank curing which predates the direct addition of nitrite to curing brines. The global influence of Griffiths who probably converted Eskort to an operation using the direct application of nitrite to curing brines following WW1. We see the influence of the Danish Cooperative system, probably through the St. Edmunds Bacon Factory. Besides any of these, we see hard work, imagination and high character and a particular response to a specific call for help.

What is the purpose of this study? Besides the fascinating context of the Eskort operation, is there anything we can learn from the past? I offer a few suggestions.

1. Stay on top of the game. Use the best and latest technology available to stay well ahead in the race. A 1914 US newspaper article, from the Deming Headlight, called the Danish cooperative bacon factory “the last word as to efficient scientific treatment of the dead porker.” The article was entitled A Cooperative Bacon factory. (The Deming Headlight (Deming, New Mexico), Friday 8 May 1914, Page 6.)

2. Use the best corporate structure, appropriate for the time.

3. This point probably dovetails into the previous one – ensure that the business is well funded.

4. Think big! No, think massive! By no account was any of the plans of JW Moor or any of his brothers or their father ever small!

5. The factory was built with a specific market in mind. “It was built for exports”, even though saying it like this may be too specific. Lets state it this way – “technology was chosen to attract the right clients.” A modern-day example may be investing in a tray ready packaging line for fresh meat for the retail trade or cooked bacon for the catering trade.

6. Things are not as bad today as they were during the world wars. If anything, we have more opportunities. No matter what is happing in our country, this can be our age of wisdom, our epoch of belief, season of light and our spring of hope!

A last comment must be made about the legacy of the bacon plant. There can be little doubt that it had a large impact on the meat processing landscape in South Africa over the years. It provides a fertile and productive training center for many men and women to later either set up their own curing operations or work at other plants across the country, thus transferring the skills inherent in the Estcourt plant to the rest of the country. In this regard, the impact of the visionary work of the Moor family is volcanic. It is interesting to talk to executives in Eskort and to realise how many people in top positions in curing operations across the county started their careers at the Eskort plant in Estcourt in the Natal Midlands.

These are some of the obvious lessons I take away from the study. This is insanely exciting!

Aftermath 1:

Back row, left to right: Gen JBM Hertzog, H Burton, FR Moor, Col. G Leuchars, Gen JC Smuts, HC Hull, FS Malan and David de Villiers Graaff. Front: JW Sauer, Gen Botha and A Fischer.

Gen Louis Botha was the man who pushed for the development of the meat industry in SA. Of course, he found a great ally in David de Villiers Graaff who created ICS. At the end of 1934, the company was in serious financial trouble following the Great Depression. Anglo-American corporation was the largest investor and as it invested more money in the company, while the company worked ever closer with Tiger Oats which was another Anglo subsidiary. In March 1982 Barlow bought a large share of Tiger Oats and the controlling share in ICS. In October 1998 Tiger Brands (Tiger Oats Limited) bought Imperial Cold Storage and it was taken up in the portfolio of this companies brands.

Look at this old photo I found. In 1910 the Union of South Africa was created uniting the Transvaal, Free State, Natal and the Cape. Botha was asked to become Prime Minister. Here is a photo of his first cabinet. David was a member of this cabinet. He is in the back row on the right.

FR Moor is 3rd from the left, back row, looking to his right. His younger brother, JW Moor was the chairman of the farmers cooperative that became Eskort. Botha opened the Eskort factory in Estcourt, Natal shortly before he passed away. The complete list of men on the photo and members of the first Union cabinet is: Back row, left to right: Gen JBM Hertzog, H Burton, FR Moor, Col. G Leuchars, Gen JC Smuts, HC Hull, FS Malan and David de Villiers Graaff. Front: JW Sauer, Gen Botha, and A Fischer.

In a way, both Eskort and Enterprise (at least Tiger Brands) were represented. The individual photos are of De Villiers Graaff and Moor.

The history and impact of bacon men and woman, run deep! What a story!

Aftermath 2:

Arnold Prinsloo, the CEO of Eskort, sent me a message. He has a present for me, a book commemorating the first 100 years of Eskort, Ltd..

edf

hdrpl

It was a day when Paul Fickling, my partner in crime at Van Wyngaardt and I decided to follow Christo Niemand’s advice to stand back a bit and think about our strategy with the business. I was glad that Paul was with me so that I could introduce him to one of the legends in our industry.

What never had was an image of JW Moor. Arnold showed me his photo.

JW Moor

Finally, I am looking for the legendary first chairman of the First Farmers Cooperative Bacon Factory to be established in SA in the eyes. We spoke about history and the Moor family; the industry at large and then Arnold gave us a bit of information that is invaluable to our quest. “Build your company on quality! Nothing less than that will exist for 100 years.”

At home, I could hardly wait to page through the book. Here I saw so many of my friends.

Wynand Nel

Arnold Prinsloo

Melindi Wyma

Bob Ferguson (I know his son, Alex)

Bob Furgeson

Wynand Nel who worked with me at Stocks Meat Market, Arnold Prinsloo, Melindi Wyma, Bob Ferguson – I know his son, Alex who is heading up Multivac.

This morning Paul was telling me about a small hotel they stayed over in Natal the previous week, Hartford House. It turns out that the house was owned by JW Moor. Arnold elucidated us and suggested we get in contact with Mickey Goss, the current owner of the estate for an in-depth discussion of the history of the region and the Moor family.

I will definitely send Mickey correspondence and arrange for a visit to his famed estate. I am thrilled to be part of this incredibly rich history, humbled by the gesture of Arnold and the coincidence of Paul and his family staying at the exact house a week ago, well, that is just strange!!

(c) Eben van Tonder

Further Reading

John William Moor’s Short Biography

The speech was given by Mr. W. S. Morris, the Minister of Agriculture at the second reading of the BACON INDUSTRY BILL before the UP parliament on 11 April 1938 3.40 p.m.

History-of-Estcourt

Tank Curing Came from Ireland

Bacon Curing – a historical review

Walworth, G.. 1940. Imperial Agriculture, London, George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

The Mother Brine

A Most Remarkable Tale: The Story of Eskort

(c) eben van tonder

“Bacon & the art of living” in book form

Stay in touch

Like our Facebook page and see the next post. Like, share, comment, contribute!

Bacon and the art of living

Promote your Page too

Note

(1) 1917 and 18 were very interesting years besides for the creation of the bacon plant in Estcourt. On 8 June, two days after the start of production, the South African financial services group Sanlam was established in Cape Town. 1917/ 1918 was the year when the RAF was founded with another interesting South African connection. On 17 August 1917, General Jan Smuts released his report recommending that a military air service should be used as “an independent means of war operations” of the British Army and Royal Navy, leading to the creation of the Royal Air Force in 1918. (Hastings, Hastings, 1987)

(2) In reality, I did go to Denmark to learn bacon curing. The interesting thing is that Tulip is a Danish company, wholly owned by Danish Crown and a direct outflow of the creation of the cooperative curing plant at Horsens. In the ’70 and ’80, the Danish abattoirs and large processing companies consolidated and formed Danish Crown. The Danes created Tulip in England to, in a way, set up their own distribution company in England for the vast quantities of bacon they produced in Denmark. Essentially, they created their own client. In later years Tulip became involved in every aspect of the pork industry in England and currently is the largest pork farmer in the UK. Exactly as it was logical for my path to lead to Tulip, so, it was logical for JW’s path to lead to the Harris operations and a cooperative bacon plant. Given the same set of variables, the best choices are obvious to all, no matter how far in the future you look back at decisions of the past.

References

https://www.danishcrown.com/danish-crown/history/

Dhupelia, U. S.. 1980. Frederick Robert Moor and Native Affairs in the Colony of Natal 1893 to 1903. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Durban-Westville. Supervisor: Dr. J.B. Brain; Date Submitted: December 1980. Download: Dhupelia-Uma-1980

Dommisse, E. 2011. First baronet of De Grendel. Tafelberg

The Freeman’s Journal, Dublin, Dublin, Ireland; 18 Oct 1878, p1.

The Guardian (London, Greater London, England), 6 July 1918, p6.

Max, Bomber Command: Churchill’s Epic Campaign – The Inside Story of the RAF‘s Valiant Attempt to End the War, New York: Simon & Schuster Inc., 1987, ISBN 0-671-68070-6, p. 38.

Morrell, R. G.. 1996. White Farmers, Social Institutions and Settler Masculinity in the Natal Midlands, 1880-1920. A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economic History. University of Natal. Durban, March 1996

http://www.openafrica.org/experiences/route/24-drakensberg-experience-route/participant/925-eskort-limited-factory-shop

Perren, R. Farmers, and consumers under strain: Allied meat

supplies in the First World War. The Agricultural Historical Review. PDF: Richard Perren

The Saint Paul Daily Globe, 10 May 1896

Thompson, P. S.. 2011. Historia Vol 56 no 1, The Natal home front in the Great War (1914-1918) On-line version ISSN 2309-8392; Print version ISSN 0018-229X. The Historical Association of South Africa c/o Department of Historical and Heritage Studies, University of Pretoria.

Walworth, G.. 1940. Feeding the Nation in Peace and War. London, George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

The Weekly Gazette, 9 Jan 1901

Wilson, W. 2005. Wilson’s Practical Meat Inspection. 7th edition. Blackwell Publishing.

http://www.elmswell-history.org.uk/arch/firms/baconfactory/article2.html”>

http://www.elmswellhistory.org.uk/arch/firms/baconfactory/baconfactory.html

https://www.revolvy.com/page/Estcourt

Where I referenced previous articles I did, the links are provided in the article and I do not reference these again.

Chapter 12.02: Eskort Ltd. Introduction to Bacon & the Art of Living The quest to understand how great bacon is made takes me around the world and through epic adventures.

0 notes

Text

When Stars Align || Lafayette x Reader - Chapter 1

PAIRING: Lafayette x Reader

SUMMARY: A woman in the revolution? They all told her that she couldn't do it, but it's not like she's ever cared what they thought. The amazing military battle strategist Gaspard Legrand's daughter had recently turned twenty-one. She heard whispers of the revolution happening in the north, but hadn't thought much of it. She was happy on her family's small farm in Virginia where she lived with her father, brother, and grandmother. Until tragedy struck. Everything that she had always been sure of, she no longer knew. Except one thing. She would be the one to free her country.

WORDS: 3107

A/N: Issa series y’all! This is actually the fanfic I’m writing on wattpad, and updates may be slow, but here it is!!

TW: one sexist guy, a death

Wind whistled past my ears as I spurred my horse through the golden fields of wheat, my frail attempt to keep up with my brother Nael. Adrenaline coursed through my veins; the last fence was in sight, and I was nearing the finish, but I silently cursed as I saw Nael already turning back to face me, a smug grin on his face.

"You are too slow, soeur cadet." He grinned and I rolled my eyes at his ego.

"Not all of us are as amazing as you, frere aîne." I shot him a playful glare as I finally jumped the last fence, joining him in the clearing beyond our farm.

"Correct, for the first time," he teased, coaxing a chuckle from me. We began to circle each other on horseback as a mischievous smirk played at my lips.

"How about a rematch? And this time you don't start before we count down," I suggested.

"Do you really want to embarrass yourself even more? I'd have thought you'd had enough."

"You wish I'd give up. To the hill at the center of the farm?" I cocked an eyebrow at him, and his face broke into a wide grin.

"You're on."

We took off once again, this time with me pulling slightly ahead as my horse galloped towards the small hill. And then, managing to escape Nael's line of vision, I dropped off of the path, stifling a laugh at my brother's triumphant smile. I waited just a moment before trotting off in the other direction towards my house.

"Où allez-vous?" Nael shouted, finally realizing that I was no longer with him.

"I'm going to get to dinner first," I shouted back with a grin as I neared the small stable on the outside of my house, but before going in, I pulled my horse, Rachel, to face the horizon behind me. I absentmindedly began to run my hand down her silky coat, feeling her breathing in her chest.

She was a rather small horse, a white lipizzan splattered with gray all down her back. My father had gotten her for me from a local trader, and I hadn't thought twice before naming her Rachel after my mother.

I had never known my mother, aside from the tales of my father's time with her in the Caribbean. Supposedly, she was a beautiful woman, and my father and she had met three years after his wife's passing, as his ship took a detour on a trading route to France. They'd met one day in the market, and were infatuated with each other within that day.

Of course, I was the unintended result of that infatuation. She had written my father six months after he left, telling him of her pregnancy and asking him to come back and take me when I was born. She told him of her struggles with the one child she already had, and that she couldn't possibly support another. And so he came, and so I left.

I sighed at the memories of the stories I'd heard so many times, bringing my wandering mind back to bask in my surroundings. It was an absolutely breathtaking sight to look down on the rolling fields that were bathed in the late sunlight, and to see the pink sky hanging above as the sun departed between the two.

I was so taken with the sight that it wasn't for a few minuted that I realized what it meant for me.