#noncommunistically

Text

guy wears womens panties

Fascinating Alyssa Branch does her best to cum

Lengua en panocha Rica y tierna

anna zharavina sexy russian from garter belt

Asian webcam girl teasing show boobs and pussy

Hot Desi Jungle Sex Village Girl Fucked By BF With Audio Awesome Boobs

Latex Lucy the British Dominatrix 1 Best Of - Scene 4

Top fucks bi married man

Squirting MILF pussylicked on the sofa

Luis Fuentes stroking huge cock

#demieagle#Entyloma#Adad#Appomattox#Glenoma#Testicardines#purgations#resubscribed#mercaptids#clone#aulophyte#corresponds#noncommunistically#orohydrography#paperjam#readmission#sternwards#nondendroidal#immatriculation#kajeput

0 notes

Text

Mi sobrino menor se quedo dormido oliendo mis tangas usadas, grabo como se le para la verga, casi se la mamo mientras duerme

Spanked gay twinks nudes movietures and emo solo Trent climbs on top

lexy con sus tetas bellas

vagabunda da aline rebolando gostoso

Clothed lezzie act with honeys addicted to the vibrator

Valerie Kay Saves BBC

زنشو با کلی آه و ناله از کون میکنه

Mature mom fucks teen milf Krissy Lynn in The Sinful Stepmother

Petite teen anally ravaged by mature cock

nymphomaniac girl selfie and her friend brush

#BVY#pledging#noncommunistical#unrespectfully#uninhibitedly#scatteredly#trimodal#zikkurats#lame#gaps#nervimotor#kissed#fullest#freeze-drying#gymnogene#كتاباتي#forebitter#anatifer#saltwaters#sothis

0 notes

Text

Teen with a soaked ass gets nailed during a massage

he likes sex with his tattooed ass

Gf playing with my dick while watching Fortnite

High school fuck with teacher นักเรียนแอบเย็ดกับครู

Russian BBW mom sucks cock cum on her face

mexicali dickflash

Double cum tribute on Siyeon of Dreamcatcher Kpop

Slutty Beautiful Step Mom Kianna Dior Helps Step Son Hiding Bad Grades from Daddy

زب فاجر وجسم فاجر من الشرقيه كلمنى خاص

Partying cfnm babe blows cock and balls

#Lune#skag#batcow#preordained#legendries#prolonge#animating#wide-palmed#Flobert#peerage#cocksparrow#idle-brained#BVY#pledging#noncommunistical#unrespectfully#uninhibitedly#scatteredly#trimodal#zikkurats

0 notes

Text

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT are these pornbot names I fucking swear

Blocking bigot and sinful noncommunist are absolute gems

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

some bot w the url “stately-noncommunist” followed me THIS IS NOT a capitalist safe space

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hollywood during The Cold War

JJ Tafuto

To say there was a lot going on in Hollywood in a post World War 2 and into the Cold War era, would be an understatement. Along with many social and cultural shifts, there was also technical advancements being made, “Between 1955 and 1958, Hollywood's production of color features declined and black-and-white production in creased, after the feature film industry began negotiating with (primarily black-and-white) television for the use of its product, as theater audiences declined. Between 1966 and 1970, color's percentage of all U.S. produced features increased from 54% to 94%, and almost all technological, economic, and aesthetic factors favored the use of color cinematography for feature films, as television's conversion to color favorably affected economic and aesthetic conditions.” (Kindem, 3) I found the use of color in films both going in, out, and back in favor was very interesting, as it corresponded with what was going on with television. I had always regarded what is going on with television and in the cinema as two separate entities, but here they are so intricately twined that they effected how their films were being presented.

As it turned out, the rise in cinema popularity and the expansion of the industry also hurt it, “The number of feature films released has a negative impact on attendance, which is contrary to initial thought. If the number of films increases by one percent, there is a 0.30 percent decrease in the percentage of the population that attends the cinema weekly on average. Thus, it would seem that the increase in the number of films to choose from could end up hurting attendance because of the fact that there are simply too many films to choose from at the cinema.” (Pautz, 12) More movie options ultimately resulting in less attendance is an interesting thread to follow, and as I thought about it I realized that even I am guilty of it. If there are days when I am deciding what I want to watch, I realize there are too many options to choose from that I end up just not choosing anything because it becomes so overwhelming.

Of course, during the time of the Cold War the United States was going through the red scare and McCarthyism, and that obviously effected Hollywood, “If there were problems in Hollywood with what was called “loyalty,” the studios could take care of them. They fired anyone who defied a Congressional committee and/or refused to establish his or her noncommunist credentials” (Thomas, 2) I find the era of McCarthyism so fascinating and especially in Hollywood as it is such an impactful and public industry. The fact that studios fired anyone who was suspected of being a Communist is so wild, which of course led to the Hollywood Ten, “Those who were either publicly or privately denounced as members of the American Communist Party (CPUSA) found it almost impossible at least for a decade to get employment in the motion-picture industry. The most famous victims of the resulting blacklist were the 'Unfriendly Ten' or 'Hollywood Ten', the original group of 'un- friendly' witnesses - mostly screenwriters - who re- fused to give political information about themselves before HUAC in October 1947 (Eckstein, 1) These screenwriters not wanting to share their private political information and just exercising their basic human rights that America was founded upon and becoming infamous for it is so crazy and speaks to all of the paranoia going on during this era.

Something I never really considered before was how the Cold War impacted Soviet films, “As Soviet cinema displayed a less dogmatic approach toward religion in the 1950s, and even began to suggest that there was room for competing belief systems in the Soviet Union, British and American films moved in the opposite direction.” (Shaw, 8) I find this very fascinating how Soviet films and American films reflected opposites of each other as a result of what was going on in the world at the time.

0 notes

Text

The DMZ

June 25, 2023 - Happy 45th birthday to our oldest son Grant!

But 73 years ago today - June 25, 1950 - the North Korea army conducted a surprise attack on their neighbors and kinsmen in the south and the Korea War was begun. It was truly a coincidence that we would visit the DMZ on this day - but there we were.

I am always surprised (although I do not know why - by now!) how much I do NOT know. Let’s face it there is very little space in our history books dedicated to the Korean War. There is no doubt that I had some general concepts about the Korea War that involve the following: Harry Truman, Military Action, United Nation action, General McArthur, Domino Theory, DMZ, China, winter weather, 33,000 US dead, "I like IKE"~... and that is about it. But - as I have said again and again - being here is different. These decisions made by men in power in the safety of well-protected rooms impact the common man walking with us on the streets today. For us, it is a but footnote for the people we are meeting it remains a part of their day to day life. More than 5 MILLION Koreans were killed during this war and more than half were civilian - just living their lives. More than 10 million families were dispersed and the search for family members separated continues to this day. Life on this peninsula is complicated by history.

Let’s start with some basic history. In 1945, WWII is over and to the victors go the spoils. Germany is carved up and doled out to the victors and the exact same thing happens in Asia.

The division of Korea began with the defeat and surrender of Japan. During the war, the Allied leaders considered the question of Korea's future after Japan's surrender in the war. The leaders reached an understanding that Korea would be liberated from Japan but would be placed under an international trusteeship until the Koreans would be deemed ready for self-rule. In the last days of the war, the U.S. proposed dividing the Korean peninsula into two occupation zones (a U.S. and Soviet one) with the 38th parallel as the dividing line. The Soviets accepted their proposal and agreed to divide Korea.

It was understood - by some but clearly not all - that this division was only a temporary arrangement until the trusteeship could be implemented. In December 1945, the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministry resulted in an agreement on a five-year four-power Korean trusteeship. (Korea would be run by the US, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and China for 5 years.) Korea had no representative present when the deal was struck and they did NOT like it. However - even the best laid paid sometimes go awry. With the onset of the Cold War and other factors both international and domestic, including Korean opposition to the trusteeship, negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union over the next two years regarding the implementation of the trusteeship failed, thus effectively nullifying the only agreed-upon framework for the re-establishment of an independent and unified Korean state. With this, the Korean question was referred to the brand new United Nations. In 1948, after the UN failed to produce an outcome acceptable to the Soviet Union, Un - supervised elections were held in then US-occupied south only. The American-backed Syngman Rhee won the election, while Kim Il Sung consolidated his position as the leader of Soviet-occupied northern Korea. This led to the establishment of the Republic of Korea in southern Korea on 15 August 1948, promptly followed by the establishment of the Democratic People Republics of Korea in northern Korea on September 9, 1948. The United States supported the South, the Soviet Union supported the North, and each government claimed sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula. And the shit-show begins…..

On June 25, 1950 military forces of communist North Korea suddenly plunged southward across the 38th parallel boundary in an attempt to seize noncommunist South Korea. Outraged, Truman reportedly responded, “By God, I’m going to let them [North Korea] have it!” Truman did not ask Congress for a declaration of war and he was later criticized for this decision. Instead, he sent to South Korea, with UN sanction, U.S. forces under Gen. Douglas MacArthur repel the invasion. Ill-prepared for combat, the Americans were pushed back to the southern tip of the Korean peninsula before MacArthur’s brilliant Inchon offensive drove the communists north of the 38th parallel. South Korea was liberated, but MacArthur wanted a victory over the communists, not merely restoration of the status quo. U.S. forces drove northward, nearly to the Yalu River boundary withManchuria. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese troops then poured into North Korea, pushing the fighting once again down to the 38th parallel. When MacArthur insisted on extending the war to China and using nuclear weapons to defeat the communists, Truman removed him from command. The war, however, dragged on inconclusively past the end of Truman’s presidency, eventually claiming the lives of more than 33,000 Americans.

The subsequent Korean War, which lasted from 1950 to 1953, ended with a stalemate and has left Korea divided by the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) ) up to the present day.

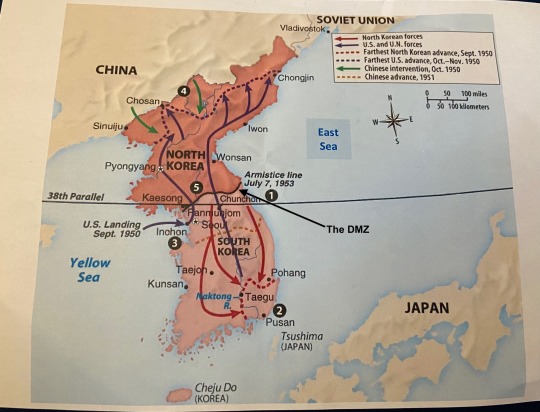

So the first map I saw blew my mind. I had NO idea that the battle lines had crossed the entire peninsula. Check this out…

Also - since we hear all about the 38th parallel - I thought - that the Korean Peninsula was split on the 38th parallel - but not exactly - that line would be straight. The line that separated this peninsula is far from straight, my friends.

The DMZ is 160 miles long and 2.5 miles wide. (The map above shows 4 tunnels that have been found (so far) built by the North for military intent. The South Koreans use these tunnels to demonstrate that the “de- militarized zone” has NOT been de- militarized after all. We visited the DMZ and went into the 3rd tunnel today.

The South Korean side of DMZ is a commercial success with coffee shops, restaurants and souvenir shops and even a theme park - I’m not kidding you.

Our trip leader, Yong, explained that the younger generation - like his 13 and 11 year old children - could care less about this 73 year old event. No one in their lives seems impacted and they like living in South Korea - just like it is. So - the theme park and campgrounds give parents an opportunity to bring their families here to have some fun and PERHAPS learn some things as well. I was certainly surprised.

This “DMZ Welcome Center” is filled with monuments and memorial. One that was exceptionally touching was to the “comfort women” of Korea. “Comfort Women” was a lovely a name for sex slaves. This memorial was to Korean women - but during WWII the Japanese rounded up young women in whatever territory they captured and sent them to their soldiers to bring “comfort.” The Japanese soldiers believing they a master race believed raping and abusing these worthless pieces of crap was their duty and many women were raped and murdered. It was a great shame to these women and many families did not accept them - IF they recovered and returned. Again - we blame the victims…. I’m so over that! Here is the monument:

I also did not know that the US has 15 military based in South Korea and that our largest overseas military base is here. Nearly 45,000 US troops, contractors, and family members live on or near the new $10.8 billion garrison in Pyeongtaek, Camp Humphreys, 45 miles from downtown Seoul leaving their former base to be turned into a public park. This arrangement is part of the Mutual Defense Treaty of 1953 between the US and South Korea.

I was struck by how often the word “unification” is used and how hopeful the movie that we saw at the DMZ was - emphasizing that it wouldn’t be long now until the two countries are unified. That might be the party line at the DMZ - but it is not the party line with the South Koreans. The ones we have spoken to wish it might happen some day - but don’t see that happening - EVER. Too much time has passed and too many differences exist. The Koreans who live north of the DMZ are simply not the same Koreans who live to the south.

We took lots of pics but it is just land with fences and walls. Sad.

Later that afternoon we met Park Yusung, a defector from North Korea and we learned so much - again. That is up next.

Stay tuned!

0 notes

Text

The scholarly and activist attempt to hold communism and the CPUSA at arm’s length has sometimes been a well-meaning effort to protect people from false accusations, since the Red Scare persecution menaced communists and noncommunists alike. But avoiding communism to present a more “acceptable” left politics dishonestly severs communism from that very politics, presenting it as an opponent of democracy rather than as an opponent of fascism.

How Black Communist Women Remade Class Struggle — Charisse Burden-Stelly, Jodi Dean

0 notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Note

for the character ask: donna

favorite thing about them

I love how savagely witty Donna is. Like she calls Josh snarky, but she dishes it out! I remember watching season 1 and being like “Yo this guy’s assistant is mean! He has to be in love with her to let her get away with that!” She’s just so smart and sharp and deserves more credit for it.

least favorite thing about them

Okay this is more the writer’s fault, but having Donna’s main character flaw/trait/whatever at the very beginning be based on her relationship with men and how so many major choices she made were based on a man. Like joining the Bartlet campaign as a result of a breakup, and then taking him back??? Gross. But at the same time, I’ve also been a woman in my early 20s who made questionable choices because of men, so I can’t blame her but I can dislike watching it.

favorite line

100% the one from The Short List: “Because when it doesn’t work out, you end up drunk in my apartment in the middle of the night, and you yell at my roommates’ cats.“ I think this is the EXACT moment I started shipping J/D because I just had and still have SO MANY QUESTIONS. It paints such a wonderful picture of their relationship and I need to know more.

brOTP

I demand more adventures of Donna and the rest of the assistants. A fanfic idea that I’ve had written on my computer for months is “The assistants go to bottomless brunch. Hilarity ensues.”

OTP

I mean it’s her husband Joshua “why did the writers get lazy and not give Josh a middle name” Lyman

nOTP

Dr. Freeride and Jack, mostly. I don’t mind Donna/Sam, and Donna/Amy isn’t my thing but I get why people would be into it.

random headcanon

Donna is a speed-reader. It’s a skill she picked up in college, and it was even more useful when at the White House she would have to read 100-page bills in a couple of hours. When her and Josh go to Hawaii, he watched her read 5 books in 5 days, and was completely amazed since he had never seen another person actually do that before.

unpopular opinion

I don’t like girlboss!Donna in seasons 6 and 7. I really miss sweet, witty Donna from the earlier seasons. Yeah, I know that it’s character development or whatever, but it really feels like the life is sucked out of her and makes me sad. It really isn’t until “The Cold” that her character starts to feel like Donna again.

song i associate with them

I gave Josh 3 songs, I’ll do 3 for Donna too:

I Think He Knows - Taylor Swift (my personal favorite Donna song)

He got that boyish look that I like in a man

I am an architect, I'm drawing up the plans

Love You For A Long Time - Maggie Rogers (I mean, I wrote a whole fanfic based on this one)

Oh, I never knew it, yeah, you took me by surprise

While I was getting lost so deep inside your diamond eyes

So many things that I still wanna say

And if devotion is a river, then I'm floating away

Slow Burn - Kasey Musgraves (Just so perfect for her)

Old soul, waiting my turn

I know a few things, but I still got a lot to learn

So I'm alright with a slow burn

favorite picture of them

“Communists look just like noncommunists.”

Send me a character and I’ll give my thoughts on them!

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fresh prince of Calcutta.

Bimala Prasanna - A self made aristocrat, with Gujarati business genes and Bengali sentiments.

#prince#royal#kolkata#bengal#catfish#businessman#gujarati#bengali#dhoti#rajbari#gradproject#noncommunist#shawl

0 notes

Text

During this initial period, the Soviet authorities placed little trust in the Polish communists. They relied first and foremost on their own security services, who were busily purging every Polish town and village of its active ‘antisocialist elements’. They made great use of those few noncommunist Poles, who could be persuaded to collaborate and to act as figure-heads for the new governmental bodies. After all, in 1945, it was only seven years since Stalin had ordered the total liquidation of the Polish Communist Party (KPP) and the execution of some 5,000 of its activists; and it was only three years since the KPP’s replacement, the Polish Workers’ Party (PPR), had been formed. Even if the Polish communists had been willing to take power at that stage, there were far too few of them to do so.

From Norman Davies’s Heart of Europe: A Short History of Poland (1984).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Damn those Haney genetics 😂😍 #haneygenetics #weyergenetics #wcw #beautiful #noncommunist #brightlight

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vietnam War 1954–1975

Vietnam War, (1954–75), a protracted conflict that pitted the communist government of North Vietnam and its allies in South Vietnam, known as the Viet Cong, against the government of South Vietnam and its principal ally, the United States. Called the “American War” in Vietnam (or, in full, the “War Against the Americans to Save the Nation”), the war was also part of a larger regional conflict (see Indochina wars) and a manifestation of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies.

At the heart of the conflict was the desire of North Vietnam, which had defeated the French colonial administration of Vietnam in 1954, to unify the entire country under a single communist regime modeled after those of the Soviet Union and China. The South Vietnamese government, on the other hand, fought to preserve a Vietnam more closely aligned with the West. U.S. military advisers, present in small numbers throughout the 1950s, were introduced on a large scale beginning in 1961, and active combat units were introduced in 1965. By 1969 more than 500,000 U.S. military personnel were stationed in Vietnam. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union and China poured weapons, supplies, and advisers into the North, which in turn provided support, political direction, and regular combat troops for the campaign in the South. The costs and casualties of the growing war proved too much for the United States to bear, and U.S. combat units were withdrawn by 1973. In 1975 South Vietnam fell to a full-scale invasion by the North.

The human costs of the long conflict were harsh for all involved. Not until 1995 did Vietnam release its official estimate of war dead: as many as 2 million civilians on both sides and some 1.1 million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters. The U.S. military has estimated that between 200,000 and 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died in the war. In 1982 the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated in Washington, D.C., inscribed with the names of 57,939 members of U.S. armed forces who had died or were missing as a result of the war. Over the following years, additions to the list have brought the total past 58,200. (At least 100 names on the memorial are those of servicemen who were actually Canadian citizens.) Among other countries that fought for South Vietnam on a smaller scale, South Korea suffered more than 4,000 dead, Thailand about 350, Australia more than 500, and New Zealand some three dozen.

Vietnam emerged from the war as a potent military power within Southeast Asia, but its agriculture, business, and industry were disrupted, large parts of its countryside were scarred by bombs and defoliation and laced with land mines, and its cities and towns were heavily damaged. A mass exodus in 1975 of people loyal to the South Vietnamese cause was followed by another wave in 1978 of “boat people,” refugees fleeing the economic restructuring imposed by the communist regime. Meanwhile, the United States, its military demoralized and its civilian electorate deeply divided, began a process of coming to terms with defeat in what had been its longest and most controversial war. The two countries finally resumed formal diplomatic relations in 1995.

French rule ended, Vietnam divided

The Vietnam War had its origins in the broader Indochina wars of the 1940s and ’50s, when nationalist groups such as Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh, inspired by Chinese and Soviet communism, fought the colonial rule first of Japan and then of France. The French Indochina War broke out in 1946 and went on for eight years, with France’s war effort largely funded and supplied by the United States. Finally, with their shattering defeat by the Viet Minh at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, the French came to the end of their rule in Indochina. The battle prodded negotiators at the Geneva Conference to produce the final Geneva Accords in July 1954. The accords established the 17th parallel (latitude 17° N) as a temporary demarcation line separating the military forces of the French and the Viet Minh. North of the line was the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or North Vietnam, which had waged a successful eight-year struggle against the French. The North was under the full control of the Worker’s Party, or Vietnamese Communist Party, led by Ho Chi Minh; its capital was Hanoi. In the South the French transferred most of their authority to the State of Vietnam, which had its capital at Saigon and was nominally under the authority of the former Vietnamese emperor, Bao Dai. Within 300 days of the signing of the accords, a demilitarized zone, or DMZ, was to be created by mutual withdrawal of forces north and south of the 17th parallel, and the transfer of any civilians who wished to leave either side was to be completed. Nationwide elections to decide the future of Vietnam, North and South, were to be held in 1956.

Accepting the de facto partition of Vietnam as unavoidable but still pledging to halt the spread of communism in Asia, U.S. Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower began a crash program of assistance to the State of Vietnam—or South Vietnam, as it was invariably called. The Saigon Military Mission, a covert operation to conduct psychological warfare and paramilitary activities in South Vietnam, was launched on June 1, 1954, under the command of U.S. Air Force Col. Edward Lansdale. At the same time, Viet Minh leaders, confidently expecting political disarray and unrest in the South, retained many of their political operatives and propagandists below the 17th parallel even as they withdrew their military forces to the North. Ngo Dinh Diem, the newly installed premier of South Vietnam, thus faced opposition not only from the communist regime in the North but also from the Viet Minh’s stay-behind political agents, armed religious sects in the South, and even subversive elements in his own army. Yet Diem had the full support of U.S. military advisers, who trained and reequipped his army along American lines and foiled coup plots by dissident officers. Operatives of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) bought off or intimidated Diem’s domestic opposition, and U.S. aid agencies helped him to keep his economy afloat and to resettle some 900,000 refugees who had fled the communist North.

By late 1955 Diem had consolidated his power in the South, defeating the remaining sect forces and arresting communist operatives who had surfaced in considerable numbers to prepare for the anticipated elections. Publicly opposed to the elections, Diem called for a referendum only in the South, and in October 1955 he declared himself president of the Republic of Vietnam. The North, not ready to start a new war and unable to induce its Chinese or Russian allies to act, could do little.

The Diem regime and the Viet Cong

Leaders in the U.S. capital, Washington, D.C., were surprised and delighted by Diem’s success. American military and economic aid continued to pour into South Vietnam while American military and police advisers helped train and equip Diem’s army and security forces. Beneath the outward success of the Diem regime, however, lay fatal problems. Diem was a poor administrator who refused to delegate authority, and he was pathologically suspicious of anyone who was not a member of his family. His brother and close confidant, Ngo Dinh Nhu, controlled an extensive system of extortion, payoffs, and influence peddling through a secret network called the Can Lao, which had clandestine members in all government bureaus and military units as well as schools, newspapers, and businesses. In the countryside, ambitious programs of social and economic reform had been allowed to languish while many local officials and police engaged in extortion, bribery, and theft of government property. That many of these officials were, like Diem himself, northerners and Roman Catholics further alienated them from the local people.

Diem’s unexpected offensive against communist political organizers and propagandists in the countryside in 1955 had resulted in the arrest of thousands and in the temporary disorganization of the communists’ infrastructure. By 1957, however, the communists, now called the Viet Cong (VC), had begun a program of terrorism and assassination against government officials and functionaries. The Viet Cong’s ranks were soon swelled by many noncommunist Vietnamese who had been alienated by the corruption and intimidation of local officials. Beginning in the spring of 1959, armed bands of Viet Cong were occasionally engaging units of the South Vietnamese army in regular firefights. By that time the Central Committee of the Vietnamese Communist Party, meeting in Hanoi, had endorsed a resolution calling for the use of armed force to overthrow the Diem government. Southerners specially trained in the North as insurgents were infiltrated back into the South along with arms and equipment. A new war had begun.

Despite its American training and weapons, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, usually called the ARVN, was in many ways ill-adapted to meet the insurgency of the Viet Cong. Higher-ranking officers, appointed on the basis of their family connections and political reliability, were often apathetic, incompetent, or corrupt—and sometimes all three. The higher ranks of the army were also thoroughly penetrated by Viet Cong agents, who held positions varying from drivers, clerks, and radio operators to senior headquarters officers. With its heavy American-style equipment, the ARVN was principally a road-bound force not well configured to pursuing VC units in swamps or jungles. U.S. military advisers responsible for helping to develop and improve the force usually lacked knowledge of the Vietnamese language, and in any case they routinely spent less than 12 months in the country.

At the end of 1960 the communists in the South announced the formation of the National Liberation Front (NLF), which was designed to serve as the political arm of the Viet Cong and also as a broad-based organization for all those who desired an end to the Diem regime. The Front’s regular army, usually referred to as the “main force” by the Americans, was much smaller than Diem’s army, but it was only one component of the Viet Cong’s so-called People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF). At the base of the PLAF were village guerrilla units, made up of part-time combatants who lived at home and worked at their regular occupations during the day. Their function was to persuade or intimidate their neighbours into supporting the NLF, to protect its political apparatus, and to harass the government, police, and security forces with booby traps, raids, kidnappings, and murders. The guerrilla forces also served as a recruiting agency and source of manpower for the other echelons of the PLAF. Above the guerrillas were the local or regional forces, full-time soldiers organized in platoon- or company-sized units who operated within the bounds of a province or region. As members of the guerrilla militia gained experience, they might be upgraded to the regional or main forces. These forces were better-equipped and acted as full-time soldiers. Based in remote jungles, swamps, or mountainous areas, they could operate throughout a province (in the case of regional forces) or even the country (in the case of the main force). When necessary, the full-time forces might also reinforce a guerrilla unit or several units for some special operation.

The U.S. role grows

By the middle of 1960 it was apparent that the South Vietnamese army and security forces could not cope with the new threat. During the last half of 1959, VC-initiated ambushes and attacks on posts averaged well over 100 a month. In the next year 2,500 government functionaries and other real and imagined enemies of the Viet Cong were assassinated. It took some time for the new situation to be recognized in Saigon and Washington. Only after four VC companies had attacked and overrun an ARVN regimental headquarters northeast of Saigon in January 1960 did Americans in Vietnam begin to plan for increased U.S. aid to Diem. They also began to search for ways to persuade Diem to reform and reorganize his government—a search that would prove futile.

To the new administration of U.S. Pres. John F. Kennedy, who took office in 1961, Vietnam represented both a challenge and an opportunity. The Viet Cong’s armed struggle against Diem seemed to be a prime example of the new Chinese and Soviet strategy of encouraging and aiding “wars of national liberation” in newly independent nations of Asia and Africa—in other words, helping communist-led insurgencies to subvert and overthrow the shaky new governments of emerging nations. Kennedy and some of his close advisers believed that Vietnam presented an opportunity to test the United States’ ability to conduct a “counterinsurgency” against communist subversion and guerrilla warfare. Kennedy accepted without serious question the so-called domino theory, which held that the fates of all Southeast Asian countries were closely linked and that a communist success in one must necessarily lead to the fatal weakening of the others. A successful effort in Vietnam—in Kennedy’s words, “the cornerstone of the free world in Southeast Asia”—would provide to both allies and adversaries evidence of U.S. determination to meet the challenge of communist expansion in the Third World.

Though never doubting Vietnam’s importance, the new president was obliged, during much of his first year in office, to deal with far more pressing issues—the construction of the Berlin Wall, conflicts between the Laotian government and the communist-led Pathet Lao, and the humiliating failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. Because of these other, more widely known crises, it seemed to some of Kennedy’s advisers all the more important to score some sort of success in Vietnam. Success seemed urgently needed as membership in the NLF continued to climb, military setbacks to the ARVN continued, and the rate of infiltration from the North increased. U.S. intelligence estimated that in 1960 about 4,000 communist cadres infiltrated from the North; by 1962 the total had risen to some 12,900. Most of these men were natives of South Vietnam who had been regrouped to the North after Geneva. More than half were Communist Party members. Hardened and experienced leaders, they provided a framework around which the PLAF could be organized. To arm and equip their growing forces in the South, Hanoi leaders sent crew-served weapons and ammunition in steel-hulled motor junks down the coast of Vietnam and also through Laos via a network of tracks known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Most of the firearms for PLAF soldiers actually came from the United States: large quantities of American rifles, carbines, machine guns, and mortars were captured from Saigon’s armed forces or simply sold to the Viet Cong by Diem’s corrupt officers and functionaries.

Many of the South’s problems could be attributed to the continuing incompetence, rigidity, and corruption of the Diem regime, but the South Vietnamese president had few American critics in Saigon or Washington. Instead, the U.S. administration made great efforts to reassure Diem of its support, dispatching Vice Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson to Saigon in May 1961 and boosting economic and military aid.

As the situation continued to deteriorate, Kennedy sent two key advisers, economist Walt W. Rostow and former army chief of staff Maxwell Taylor, to Vietnam in the fall of 1961 to assess conditions. The two concluded that the South Vietnamese government was losing the war with the Viet Cong and had neither the will nor the ability to turn the tide on its own. They recommended a greatly expanded program of military assistance, including such items as helicopters and armoured personnel carriers, and an ambitious plan to place American advisers and technical experts at all levels and in all agencies of the Vietnamese government and military. They also recommended the introduction of a limited number of U.S. combat troops, a measure the Joint Chiefs of Staff had been urging as well.

Well aware of the domestic political consequences of “losing” another country to the communists, Kennedy could see no viable exit from Vietnam, but he also was reluctant to commit combat troops to a war in Southeast Asia. Instead, the administration proceeded with vigour and enthusiasm to carry out the expansive program of aid and guidance proposed in the Rostow-Taylor report. A new four-star general’s position—commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam (USMACV)—was established in Saigon to guide the military assistance effort. The number of U.S. military personnel in Vietnam, less than 800 throughout the 1950s, rose to about 9,000 by the middle of 1962.

The conflict deepens

Buoyed by its new American weapons and encouraged by its aggressive and confident American advisers, the South Vietnamese army took the offensive against the Viet Cong. At the same time, the Diem government undertook an extensive security campaign called the Strategic Hamlet Program. The object of the program was to concentrate rural populations into more defensible positions where they could be more easily protected and segregated from the Viet Cong. The hamlet project was inspired by a similar program in Malaya, where local farmers had been moved into so-called New Villages during a rebellion by Chinese Malayan communists in 1948–60. In the case of Vietnam, however, it proved virtually impossible to tell which Vietnamese were to be protected and which excluded. Because of popular discontent with the compulsory labour and frequent dislocations involved in establishing the villages, many strategic hamlets soon had as many VC recruits inside their walls as outside.

Meanwhile, the Viet Cong learned to cope with the ARVN’s new array of American weapons. Helicopters proved vulnerable to small-arms fire, while armoured personnel carriers could be stopped or disoriented if their exposed drivers or machine gunners were hit. The communists’ survival of many military encounters was helped by the fact that the leadership of the South Vietnamese army was as incompetent, faction-ridden, and poorly trained as it had been in the 1950s. In January 1963 a Viet Cong battalion near the village of Ap Bac in the Mekong delta, south of Saigon, though surrounded and outnumbered by ARVN forces, successfully fought its way out of its encirclement, destroying five helicopters and killing about 80 South Vietnamese soldiers and three American advisers. By now some aggressive American newsmen were beginning to report on serious deficiencies in the U.S. advisory and support programs in Vietnam (see Sidebar: The Vietnam War and the Media), and some advisers at lower levels were beginning to agree with them, but there was also a large and powerful bureaucracy in Saigon that had a deep stake in ensuring that U.S. programs appeared successful. The USMACV commander Paul Harkins and U.S. Ambassador Frederick Nolting in particular continued to assure Washington that all was going well.

By the summer of 1963, however, there were growing doubts about the ability of the Diem government to prosecute the war. The behaviour of the Ngo family, always odd, had now become bizarre. Diem’s brother Nhu was known to smoke opium daily and was suspected by U.S. intelligence of secretly negotiating with the North. Nhu’s wife, known to the world as Madame Nhu, wielded enormous influence, which she used to promote Roman Catholic social causes and ridicule the country’s Buddhist majority. In May 1963 the Ngos became embroiled in a fatal quarrel with the Buddhist leadership. Strikes and demonstrations by Buddhists in Saigon and Hue were met with violence by the army and Nhu’s security forces and resulted in numerous arrests. The following month a Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Duc, publicly doused himself with gasoline and set himself ablaze as a protest against Diem’s repression. Sensational photographs of that event were on the front pages of major American newspapers the following morning.

By now many students and members of the professional classes in South Vietnamese cities had joined the Buddhists. After a series of brutal raids by government forces on Buddhist pagodas in August, a group of South Vietnamese generals secretly approached the U.S. government to determine how Washington might react to a coup to remove Diem. The U.S. reply was far from discouraging, but it was not until November, after further deterioration in Diem’s relations with Washington, that the generals felt ready to move. On November 1, ARVN units seized control of Saigon, disarmed Nhu’s security forces, and occupied the presidential palace. The American attitude was officially neutral, but the U.S. embassy maintained contact with the dissident generals while making no move to aid the Ngos, who were captured and murdered by the army.

Diem’s death was followed by Kennedy’s less than three weeks later. With respect to Vietnam, the assassinated president left his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, a legacy of indecision, half-measures, and gradually increasing involvement. Kennedy had relished Cold War challenges; Johnson did not. A veteran politician and one of the ablest men ever to serve in the U.S. Senate, he had an ambitious domestic legislative agenda that he was determined to fight through Congress. Foreign policy crises would be at best a distraction and at worst a threat to his domestic reforms. Yet Johnson, like Kennedy, was also well aware of the high political costs of “losing” another country to communism. He shared the view of most of his advisers, many of them holdovers from the Kennedy administration, that Vietnam was also a key test of U.S. credibility and ability to keep its commitments to its allies. Consequently, Johnson was determined to do everything necessary to carry on the American commitment to South Vietnam. He replaced Harkins with Gen. William Westmoreland, a former superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and increased the number of U.S. military personnel still further—from 16,000 at the time of Kennedy’s death in November 1963 to 23,000 by the end of 1964.

The Gulf of Tonkin

While Kennedy had at least the comforting illusion of progress in Vietnam (manufactured by Harkins and Diem), Johnson faced a starker picture of confusion, disunity, and muddle in Saigon and of a rapidly growing Viet Cong in the countryside. Those who had expected that the removal of the unpopular Ngos would lead to unity and a more vigorous prosecution of the war were swiftly disillusioned. A short-lived military junta was followed by a shaky dictatorship under Gen. Nguyen Khanh in January 1964.

In Hanoi, communist leaders, believing that victory was near, decided to make a major military commitment to winning the South. Troops and then entire units of the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) were sent south through Laos along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which was by that time becoming a network of modern roads capable of handling truck traffic. Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong strongly supported the North Vietnamese offensive and promised to supply weapons and technical and logistical personnel. The Soviets, though now openly hostile to China, also decided to send aid to the North.

With the South Vietnamese government in disarray, striking a blow against the North seemed to the Americans to be the only option. U.S. advisers were already working with the South Vietnamese to carry out small maritime raids and parachute drops of agents, saboteurs, and commandos into North Vietnam. These achieved mixed success and in any case were too feeble to have any real impact. By the summer of 1964 the Pentagon had developed a plan for air strikes against selected targets in North Vietnam designed to inflict pain on the North and perhaps retard its support of the war in the South. To make clear the U.S. commitment to South Vietnam, some of Johnson’s advisers urged him to seek a congressional resolution granting him broad authority to take action to safeguard U.S. interests in Southeast Asia. Johnson, however, preferred to shelve the controversial issue of Vietnam until after the November election.

An unexpected development in August 1964 altered that timetable. On August 2 the destroyer USS Maddox was attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats while on electronic surveillance patrol in the Gulf of Tonkin. The preceding day, patrol boats of the South Vietnamese navy had carried out clandestine raids on the islands of Hon Me and Hon Nieu just off the coast of North Vietnam, and the North Vietnamese may have assumed that the Maddox was involved. In any case, the U.S. destroyer suffered no damage, and the North Vietnamese boats were driven off by gunfire from the Maddox and from aircraft based on a nearby carrier.

President Johnson reacted to news of the attack by announcing that the U.S. Navy would continue patrols in the gulf and by sending a second destroyer, the Turner Joy, to join the Maddox. On the night of August 4 the two ships reported a second attack by torpedo boats. Although the captain of the Maddox soon cautioned that evidence for the second incident was inconclusive, Johnson and his advisers chose to believe those who insisted that a second attack had indeed taken place. The president ordered retaliatory air strikes against North Vietnamese naval bases, and he requested congressional support for a broad resolution authorizing him to take whatever action he deemed necessary to deal with future threats to U.S. forces or U.S. allies in Southeast Asia. The measure, soon dubbed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, passed the Senate and House overwhelmingly on August 7. Few who voted for the resolution were aware of the doubts concerning the second attack, and even fewer knew of the connection between the North Vietnamese attacks and U.S.-sponsored raids in the North or that the Maddox was on an intelligence mission. Although what many came to see as Johnson’s deceptions would cause problems later, the immediate result of the president’s actions was to remove Vietnam as an issue from the election campaign. In November Johnson was reelected by a landslide.

The United States enters the war

Between the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the U.S. presidential election in November 1964, the situation in Vietnam had changed for the worse. Beginning in September, the Khanh government was succeeded by a bewildering array of cliques and coalitions, some of which stayed in power less than a month. In the countryside even the best ARVN units seemed incapable of defeating the main forces of the Viet Cong. The communists were now deliberately targeting U.S. military personnel and bases, beginning with a mortar attack on the U.S. air base at Bien Hoa near Saigon in November.

0 notes