#neanderthalfunerary

Text

Term Paper: Mortuary Practices in the Symbolic Culture of Neanderthals

Abstract: The significance of burial rituals for Homo neanderthalensis throughout their time on Earth attests to a rich symbolic culture and a cognitive capacity for social organization and connectedness, yet a sparse fossil record restricts comprehensive understanding of behavioral processes driving both unique and widespread interment techniques.

From pinpointing the advent of intentional burials, to finding distinct patterns within chronological and population groupings, there are no easy answers to the questions posed by available literature. Examining funerary site features alongside constructs such as symbolic culture, sociality, and modernity requires a reinterpretation of models rooted in our own species’ characteristics.

Nevertheless, it is clear that Neanderthals shared a complexity akin to that of early Homo sapiens, and future findings will only enhance our understanding of their advanced connection to the environment and peoples around them.

#anthropology#neanderthal#archeology#neanderthalfunerary#prehistoric#evolution#student research#term paper#funerary art#burial rituals#symbolic culture#symbolic art#humans are weird

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Build-A-Burial: An Inventory of Neanderthal Funerary Sites (November 4, 2022)

An illustration of the Neanderthals at Shanidar Cave (Smithsonian Human Origins Program).

Each Neanderthal site found with evidence to suggest intentional mortuary practices is subject to thorough academic scrutiny in its designation as a burial grounds. These discussions are held on both a case-by-case basis and towards the species as whole. [1]

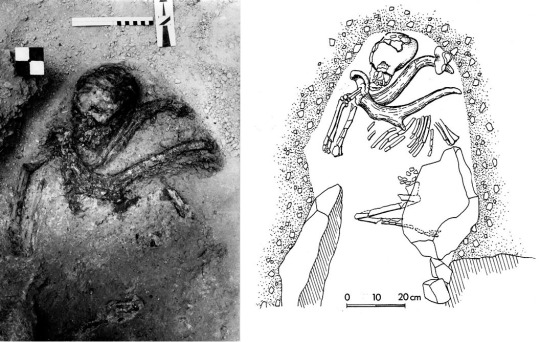

Museum reconstruction of the Neanderthal burial at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France (Mourre, 2017).

[2] [3] In questioning whether or not we can say that Neanderthals had the capacity for cognitive processes and social organization that would motivate ritualistic behavior, there is much debate within the anthropological field as to the indications that a specimen can be said to represent:

A deliberate interment, perhaps

Alongside other intentional burials

In some meaningful position/orientation;

The characteristics of which [4] influenced by social frameworks, such as:

Age or sex

Community role (e.g., as a 'shaman' figure [5])

Status or prestige

Emotional constructs (e.g., care, compassion, grief)

With associated grave goods

Potentially chosen based on symbolic meaning (tied to any of the above elements) [6]

Not the result of external disturbances (from local fauna or natural elements)

Thus, the following is a synthesis of mortuary features, supplemented by the evidence found at iconic sites. [7]

Each category includes both specific artifacts found at sites determined to be burials, as well as general implements from the repertoire of Neanderthal material culture.

Of course, I must preface with the usual disclaimer that all sites labeled as 'intentional burials' are not definitively so, but rather based upon analysis by many researchers (and likely contested by just as many).

Context

Layout of the La Ferrassie site and specimens (Pettit, 2002).

Site Organization

Temporal variation (seasonal occupations, at different stratigraphic layers by different populations)

Cohabitation (with other hominin species)

As one section of a multipurpose site

Surrounding Situ

Hearths (charcoal, ash, animal remains)

Tool processing (lithic debris)

Butchering and animal processing (animal remains, lithic debris)

'Campsite' shelters (fiber 'bedding', stone circle structures)

Other Specimens

Other deliberate interments [8]

Individuals not intentionally buried (died as a result of natural disasters, conflict) or corpse 'dumping zones'

Condition:

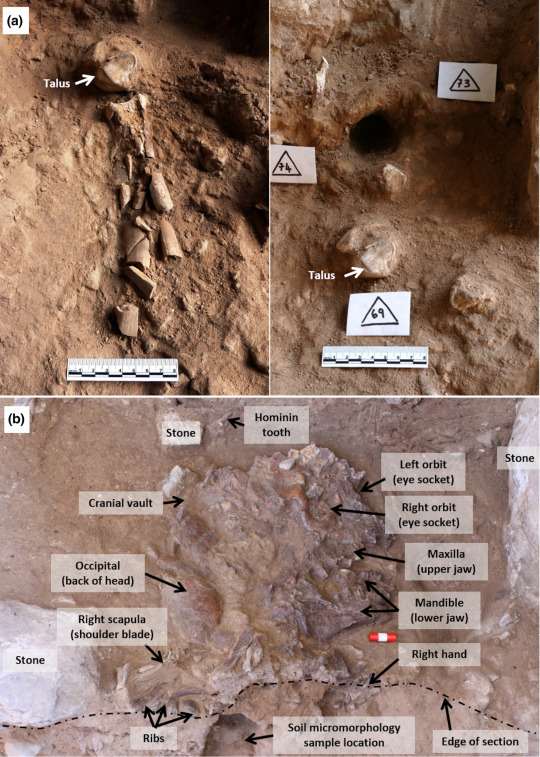

Labeled photographs of Shanidar remains in situ (Barker, 2015).

Primary burial

Secondary (later additions to the same burial 'plot')

Articulated (anatomical manipulation/positioning)

Spatially oriented (in relation to cardinal directions or other burials)

De-fleshed (cannibalism?) [9]

Bodily trauma (interpersonal violence?)

Healed wounds (caregiving?)

Grave goods

The Qafzeh 11 burial: an adolescent with a portion of the skull from a large deer laid upon its upper body (Neuville, 1933).

Animal remains

Ibex horns (Teshik-Tash)

Red deer maxilla bone (Amud 7)

Mammal jawbone (Shanidar II & V)

Pierced eagle talons (mythos?)

An example of potential Neanderthal ‘art’: a carved deer bone found at Einhornhöhle, Germany (Minkus).

Implements and ornamentation

Mousterian flake-based lithics

Organic material tools (bone, wood)

Carved figures (stone, bone, wood)

Marine shells (stacked, pierced)

Red ochre [10]

Flowers? (Shanidar IV) [11]

Sample Sites

Amud cave excavation (Garrett).

Krapina cave, Croatia (first excavated/discovered 1899)

La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France (1908)

La Ferrassie, France (1909)

Qafzeh cave, Israel (1929)

Teshik-Tash, Uzbekistan (1938)

Shanidar cave, Iraq (1957)

Amud cave, Israel (1961)

----- References & Further Reading -----

[1] Overview of human burial practices

Pettitt, Paul. “Landscapes of the dead: the evolution of human mortuary activity from body to place in palaeolithic Europe.” Settlement, Society and Cognition in Human Evolution, January 26, 2015, 258–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139208697.015.

[2] Analysis of Neanderthal burial sites and features

Koutamanis, Dafne. “The Place of the Neanderthal Dead: Multiple Burial Sites and Mortuary Space in the Middle Palaeolithic of Eurasia.” 2012. https://studenttheses.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2661542/view.

[3] Neanderthal burials in the fossil record

Emery, Kate Meyers. “Neanderthal Burials.” Bones Don’t Lie, April 26, 2011. https://bonesdontlie.wordpress.com/2011/04/25/neanderthal-burials/.

[4] Variability in Neanderthal burial site features

Pettitt, Paul. “The Neanderthal Dead: Exploring Mortuary Variability in Middle Palaeolithic Eurasia.” Before Farming 4 (January 2002): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3828/bfarm.2002.1.4.

[5] A potential case of animal-based spirituality in Neanderthals

Morton, Glenn. “Origins: The Shaman’s Cape-Religion among the Neanderthals.” www2.asa3.org, December 16, 1996. http://www2.asa3.org/archive/asa/199612/0102.html.

[6] Neanderthal symbolic and ritualistic thought

Nielsen, Mark, Michelle C. Langley, Ceri Shipton, and Rohan Kapitány. “Homo Neanderthalensis and the Evolutionary Origins of Ritual in Homo Sapiens.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 375, no. 1805 (June 29, 2020): 20190424. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0424.

[7] Critical analysis of Neanderthal intentional burials

Gargett, Robert H., Harvey M. Bricker, Geoffrey Clark, John Lindly, Catherine Farizy, Claude Masset, David W. Frayer, et al. “Grave Shortcomings: The Evidence for Neandertal Burial [and Comments and Reply].” Current Anthropology 30, no. 2 (1989): 157–90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2743544?seq=10#metadata_info_tab_contents.

[8] Multi-burial Neanderthal sites

Whelan, Ed. “New Evidence Ends the Neanderthal Burial Debate.” www.ancient-origins.net, December 11, 2020. https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/neanderthal-death-rites-0013303.

[9] Intersections between cannibalism and mortuary practices in Neanderthals

www.neandertals.org. “Burial, Ritual, Religion, and Cannibalism,” n.d. https://www.neandertals.org/ritual.html.

[10] Red ochre in Neanderthal burial sites

Roebroeks, W., M. J. Sier, T. K. Nielsen, D. De Loecker, J. M. Pares, C. E. S. Arps, and H. J. Mucher. “Use of Red Ochre by Early Neandertals.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, no. 6 (January 23, 2012): 1889–94. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1112261109.

[11] Shanidar IV Neanderthal 'flower burial'

Solecki, R. S. “Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq.” Science 190, no. 4217 (November 28, 1975): 880–81. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.190.4217.880.

----- Selected Sites -----

Krapina cave

Russell, Mary D. “Mortuary Practices at the Krapina Neandertal Site.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 72, no. 3 (March 1987): 381–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330720311.

La Chapelle-aux-Saints

Rendu, W., C. Beauval, I. Crevecoeur, P. Bayle, A. Balzeau, T. Bismuth, L. Bourguignon, et al. “Evidence Supporting an Intentional Neandertal Burial at La Chapelle-Aux-Saints.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 1 (December 16, 2013): 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1316780110.

La Ferrassie

Balzeau, Antoine, Alain Turq, Sahra Talamo, Camille Daujeard, Guillaume Guérin, Frido Welker, Isabelle Crevecoeur, et al. “Pluridisciplinary Evidence for Burial for the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal Child.” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (December 2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77611-z.

Quafzeh cave

Vandermeersch, Bernard, and Ofer Bar-Yosef. “The Paleolithic Burials at Qafzeh Cave, Israel.” Paléo 30, no. 1 (December 30, 2019): 256–75. https://doi.org/10.4000/paleo.4848.

Teshik-Tash

Wikipedia. “Teshik-Tash 1,” April 30, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Teshik-Tash_1.

Shanidar cave

Pomeroy, Emma, Paul Bennett, Chris O. Hunt, Tim Reynolds, Lucy Farr, Marine Frouin, James Holman, Ross Lane, Charles French, and Graeme Barker. “New Neanderthal Remains Associated with the ‘Flower Burial’ at Shanidar Cave.” Antiquity 94, no. 373 (February 2020): 11–26. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.207.

Amud cave

Hovers, Erella, Yoel Rak, Ron Lavi, and William H. Kimbel. “Hominid Remains from Amud Cave in the Context of the Levantine Middle Paleolithic.” Paléorient 21, no. 2 (1995): 47–61. https://href.li/?https://www.jstor.org/stable/41492632#metadata_info_tab_contents.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Announcement of Death: An Obituary for Shanidar I (November 2, 2022)

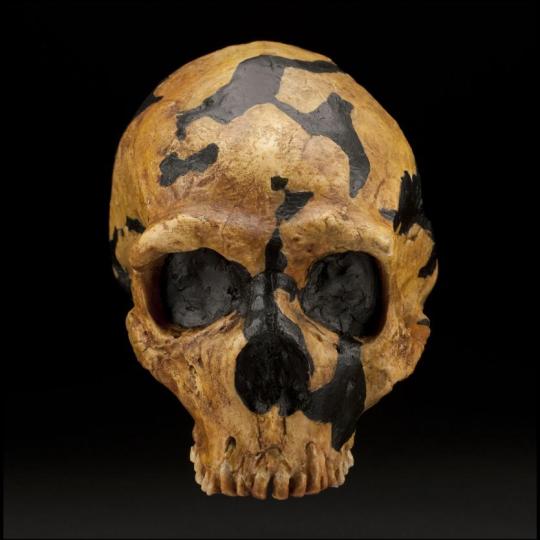

Skull cast of Shanidar I (Clark, 2012).

Shanidar 1, aged somewhere around 30 to 45, is estimated to have perished from falling rocks in a collapsing Shanidar Cave, Iraq, between 45,000 and 35,000 years ago.

Laid to rest (perhaps by survivors of the collapse) in a pit and covered with sediment from later cave-ins, his remains were discovered by Ralph Solecki in 1957. [1]

His burial, alongside those of at least nine others at the site, constitute a foundational source of insight into the mortuary practices of Homo neanderthalensis. [2]

Paleo-pathological assessment has determined that throughout the course of his life, ‘Nandy’- as he was nicknamed by his excavators- experienced a variety of significant injuries and degeneration. [3]

Speculative illustration of Shanidar I (Miladinovic).

A major blow to the head likely rendered him at least partially blind in his left eye, on top of profound hearing loss from bone spurs in both ear canals. Examination of these exostoses yielded a diagnosis of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, making Nandy the earliest potential example of this condition. [4] Worn down teeth indicate a possible degenerative disease, and he would have walked with a limp as a result of both legs being broken or deformed. With Nandy's lower right arm missing and a distinct fracture at the humerus, there is evidence to suggest that he was the recipient of some early form of surgery and amputation. [5]

Because of the debilitating effects of these injuries, it is unlikely that Nandy would have been able to survive to such old age without external support. The fact that many of his pathologies show signs of healing over time insinuate that he was provided for, to some extent, by members of his community.

Trauma sustained to the right side of Shanidar I’s face (Trinkhaus, 2017).

‘Compassion,’ or some analogous concept, may have played an important role in Neanderthal thought processes and social interactions. [6]

Nandy and the other Shanidar specimens exhibiting antemortem trauma are far from the only members of their species to have been found in situations indicative of intentional burial.

Shanidar 1 is not survived by any family members. However, to this day, the individuals from Shanidar Cave provide anthropologists with a wealth of information about the extent of Neanderthal capacity for symbolic thought, technological complexity, and altruism.

Illustration depicting a gathering in Shanidar Cave (Miladinovic).

----- References & Further Reading -----

[1] Shanidar Cave

Wikipedia. “Shanidar Cave,” October 29, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shanidar_Cave#Shanidar_1.

[2] Neanderthal mortuary practices in the context of Shanidar Z

Lewsy, Fred. “Shanidar Z: What Did Neanderthals Do with Their Dead?” University of Cambridge, February 18, 2020. https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/shanidarz.

[3] Trauma among the Shanidar Neanderthals

Trinkaus, E., and M. R. Zimmerman. “Trauma among the Shanidar Neandertals.” American Journal of Physical Anthropology 57, no. 1 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1002/AJPA.1330570108.

[4] Hearing loss in Shanidar I

Trinkaus, Erik, and Sébastien Villotte. “External Auditory Exostoses and Hearing Loss in the Shanidar 1 Neandertal.” Edited by Karen Rosenberg. PLOS ONE 12, no. 10 (October 20, 2017): e0186684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186684.

[5] Health-related care for the Shanidar I

Kent, Laura. “Health-Related Care for the Neanderthal Shanidar 1.” ANU Undergraduate Research Journal 8 (August 1, 2017): 83–91. https://doi.org/10.22459/aurj.08.2016.07.

[6] Neanderthal caregiving and emotional constructs

Spikins, Penny, Andy Needham, Lorna Tilley, and Gail Hitchens. “Calculated or Caring? Neanderthal Healthcare in Social Context.” World Archaeology 50, no. 3 (February 22, 2018): 384–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2018.1433060.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resting in Pieces: An Archeological ‘Op-Ed’ (October 26, 2022)

With reference to the Neanderthal, a hulking, brutish figure comes to mind.

Covered in hair or clad scantily in rough animal hides, images of such primitive creatures aimlessly beating stones together evoke a certain incompleteness. Not a missing link, but rather, yet another branch of humanity’s family tree that failed to grow with us. [1]

An imagined depiction of a Neanderthal man (1888).

After disappearing from the archeological record some forty thousand years ago [2], the modern Homo neanderthalensis takes up residence as a shadow of itself in media representation.

The reality gathered from an extensive archeological record stands in harsh contrast to the entertainment industry’s caricaturization.

Anthropologists construct an ever growing profile of Neanderthal morphological development, environmental adaptation, technological construction, and symbolic culture from finds at sites across Europe and parts of Southwest Asia. [3]

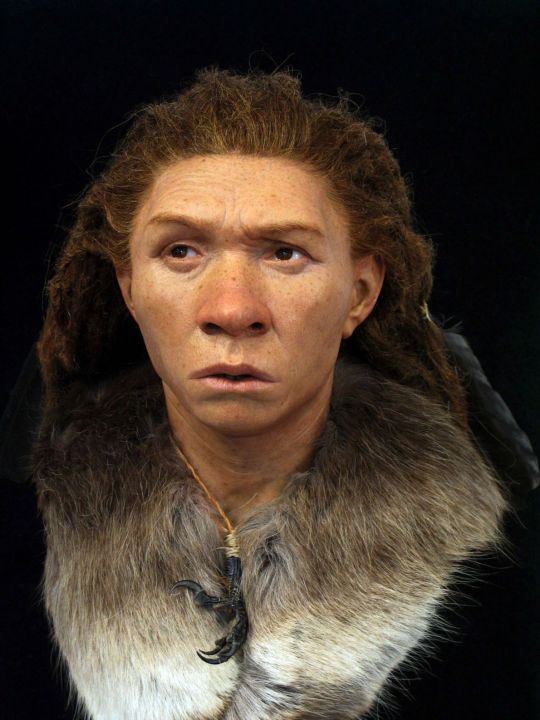

Facial reconstruction of a Neanderthal woman based on the Gilbratar 1 skull (Nilsson).

These were not simple ‘cavemen’ restricted to crude stone implements and grunts, and for reasons I can only attempt to explain, I find myself in many situations acting as an advocate to set the story straight. [4]

When opportunities present themselves (and they do, more often than one would expect), my ramblings are often met with shock. It is initially unfathomable, for most, to grasp the concept of Neanderthals occupying a niche in any way comparable to that of our own ancient ancestors.

These tangents often build up in intensity, as I work my way through an arsenal of trivia that only scratches the surface of what decades of fieldwork and analysis has provided. Eventually, whatever trivial (but misinformed) comment sparked this tirade is met with the coup de grâce: DNA evidence of interbreeding between humans and Neanderthals. [5]

A simplified model of Homo sapiens phylogeny.

To deny some degree of identifiability with the species known as Homo neanderthalensis becomes impossible once confronted with their impressions in our own genetic code.

Admittedly, I cannot blame whichever poor soul made the mistake of joking within earshot that they feel like a Neanderthal after failing their midterm for not sharing my fixation on this subject. I think it’s safe to say that the Neanderthals in question are unlikely to be bothered by their current role in our pop culture.

Nevertheless, why this prototype might persist intrigues me. Perhaps our tendency to disregard the possibility of non-human species exhibiting ‘human’ traits speaks to something buried more deeply than the expanding list of artifacts lending support for mental processes once thought to be beyond the abilities of other members from the genus Homo.

Neanderthal remains from the 'flower burial' at Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan (Barker, 2020).

Maybe it’s not about what we gain when we recognize Neanderthals for what they are, but rather, what we lose.

To consider the possibility of verbal speech; ritual behavior; shared environmental awareness; localized traditions; and ornamentation reflecting some meaning understood across regions and populations is to consider the role these beings played in the lives of Homo sapiens. [6]

If we accept that members of our own species coexisted- and, to some extent, cohabited with- Neanderthals, then we must accept that in their absence we are missing a vital connection to our past.

We must grieve a culture whose hands will never touch our own as they once did those of our ancestors.

There exists, however, an optimistic alternative to fantasizing about an Earth on which other hominin species still walked alongside us.

Handprints stenciled onto a wall at El Castillo Cave, Spain, an example of the oldest cave art on record, provide anthropologists with insight into the symbolic culture of their creators.

Paintings at El Castillo Cave theorized to belong to Neanderthals (Saura, 2012).

For casual followers of the field like myself, sites like this are tangible signs of life and diversity within the so-called ‘human’ experience. [7] [8]

We will never fully understand what cognitive mechanisms at work motivated a Neanderthal individual to leave their mark in this way.

But I can picture myself pressing out a print of my own on top, and there is closure in the knowledge that- despite differences in size and bone structure- our hands would overlap.

A closeup of a stenciled handprint at El Castillo Cave (Saura, 2012).

----- References & Further Reading -----

[1] Neanderthals in pop culture

Wikipedia. “Neanderthals in Popular Culture,” August 15, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neanderthals_in_popular_culture.

[2] Neanderthal extinction

Higham, Tom, Katerina Douka, Rachel Wood, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Fiona Brock, Laura Basell, Marta Camps, et al. “The Timing and Spatiotemporal Patterning of Neanderthal Disappearance.” Nature 512, no. 7514 (August 2014): 306–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13621.

[3] Neanderthal sites

Wikipedia. “List of Neanderthal Sites,” September 25, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Neanderthal_sites.

[4] Neanderthal technology complexity

Hoffecker, John F. “The Complexity of Neanderthal Technology.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 9 (February 12, 2018): 1959–61. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800461115.

[5] Other hominin contributions to Homo sapiens DNA

The Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program. “Ancient DNA and Neanderthals,” June 14, 2012. https://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/genetics/ancient-dna-and-neanderthals.

[6] Interactions between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens

Herrera, Kristian J., Jason A. Somarelli, Robert K. Lowery, and Rene J. Herrera. “To What Extent Did Neanderthals and Modern Humans Interact?” Biological Reviews 84, no. 2 (May 2009): 245–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185x.2008.00071.x.

[7] El Castillo Cave site

Hitchcock, Don. “El Castillo Cave.” www.donsmaps.com, n.d. https://www.donsmaps.com/castillo.html.

[8] Neanderthal cave art

Balter, Michael. “Did Neandertals Paint Early Cave Art?” www.science.org, June 14, 2012. https://www.science.org/content/article/did-neandertals-paint-early-cave-art.

5 notes

·

View notes