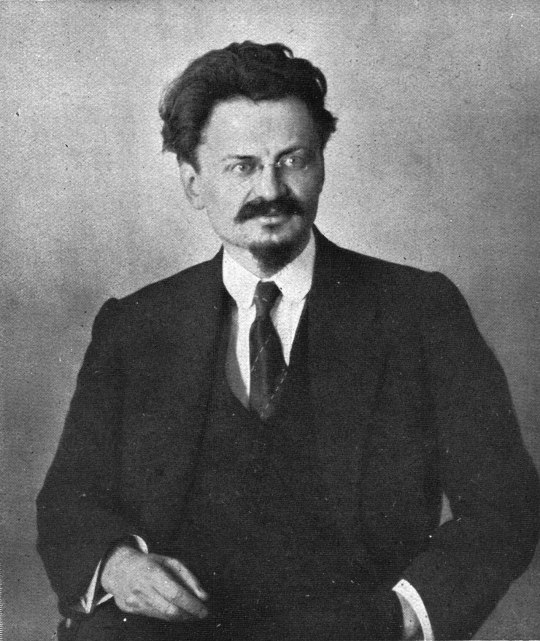

#lev Trotsky

Text

Hurrayyy hard choice between all the suggestions, but I studied with care this nonsense mix. 47% chances I’ll go for a second round.

#lonelloid#six fanarts#character design#narancia ghirga#inigo montoya#xadhoom#lev trotsky#oswald the lucky rabbit#ruth whitefeather feldman#disjointed#disney

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Leon Trotsky pays tribute to the victims of a bomb attack at the Moscow headquarters of the Communist Party on September 26, 1919. Anarchists and other leftists were blamed for killing 12 people and injuring 55."

“1919: The Year in Photographs (a Look Back at Life 100 Years Ago).” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, www.rferl.org/a/life-100-years-ago-1919-in-photographs/30296986.html.

#Leon Trotsky#Trotsky#Lev Trotsky#Лев Троцкий#Леон Троцкий#Russian Revolution#the Russian Revolution#Communist Party#Communism#Communist Russia#Soviet Russia#Russian History#Soviet History

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Trotsky#lev Trotsky#Leon Trotsky#Russian Revolution#Bolshevik#communism#russia#soviet union#ussr#October Revolution

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We must open negotiations with those governments which at present exist. However, we are conducting these negotiations in a way affording the public the fullest possibility of controlling the crimes of their governments, and so as to accelerate the rising of the working masses against the imperialist cliques.

...

"Our people bled in the course of the last three years in the imperialist murder campaign, and the revolution became first of all a means of freeing them from the horrors and sufferings of the war. The Jacobin Revolution of 1792 had a feudal Europe against it. The proletarian revolution of 1917 faces an imperialist Europe, divided into two hostile camps. If to the 'sans-culottes' the war was the direct continuation of the liberating revolution, then to the Russian soldier who has not yet left the trenches occupied by him for three years, the revolutionary war on an extensive scale would seem nothing else but a continuation of the preceding murder."

-Lev Trotsky, "Peace Negotiations and the Revolution," 1918

#socialism#communism#marxism#politics#soviet union#history#trotsky#lev trotsky#soviet#revolution#russian revolution#brest litovsk#world war i#bolsheviks#bolshevik#communist

0 notes

Text

What is the Marxist Explanation for the fact that all the old Bolsheviks look like knockoff versions of each other?

#marxism#bolshevism#vladimir lenin#nikolai bukharin#leon trotsky#yakov sverdlov#josef stalin#lev kamenev#leftcom

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Morirò rivoluzionario, proletario, marxista, materialista dialettico e di conseguenza ateo convinto. La mia fede nell'avvenire comunista dell'umanità non è meno ardente, anzi è più salda oggi di quanto non fosse nella prima gioventù. Natascia si è appena avvicinata alla finestra che dà sul cortile, e l'ha aperta in modo che l'aria entri più liberamente nella mia stanza. Posso vedere la lucida striscia verde dell'erba ai piedi del muro, e il limpido cielo azzurro al disopra del muro, e sole dappertutto. La vita è bella. Invito le generazioni future a purificarla da ogni male, oppressione e violenza e a goderla a pieno.“

Lev Trotsky

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

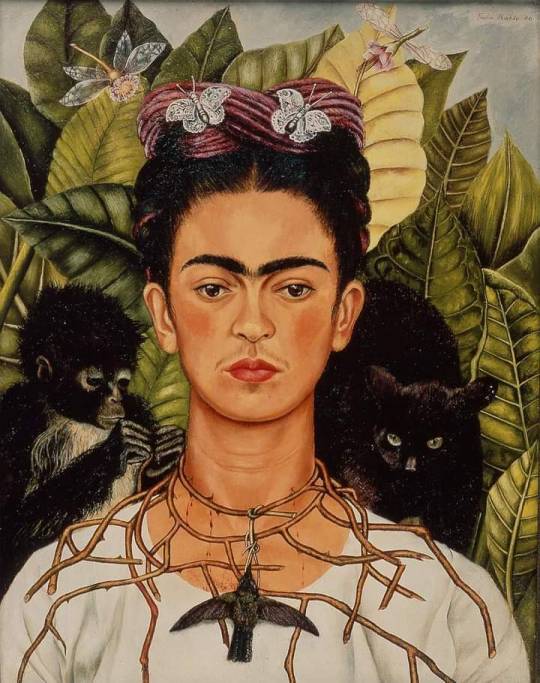

13 LUGLIO 1954 moriva FRIDA KAHLO

Un corpo fragile e uno spirito indomito.

Una vita difficile, quella di Frida Kahlo, segnata dalla lunga malattia e da grandi passioni, vissute senza remore, incondizionatamente con tutta sé stessa, abbandonano al cuore la razionalità.

La passione per l’arte, quella per il suo Messico e l’amore tormentato per Diego Rivera, il compagno di una vita.

Quella di Frida è stata una vita breve ma ricchissima perché vivere col cuore non significa limitarsi a contare i giorni, i mesi o gli anni, ma significa contare le emozioni, perché la vita non è mera sopravvivenza. E non è vero che chi vive più a lungo vive di più.

Frida Kahlo è stata un’artista coraggiosa, capace di trasformare la sofferenza in ispirazione, le sconfitte in capolavori, plasmando opere che sono un urlo orgoglioso e potente alla sfida del vivere.

LA VITA E LE OPERE DI FRIDA KAHLO:

RIASSUNTO IN DUE MINUTI (DI ARTE)

1. Frida Kahlo (Coyoacán 1907 – 1954) è considerata una delle più importanti pittrici messicane. Molti la annoverano tra gli artisti legati al movimento surrealista, ma lei non confermerà mai l’adesione a tale corrente.

Fin da bambina dimostra di avere un carattere forte, passionale, unito ad un talento e a delle capacità fuori dalla norma. Purtroppo la sua forza di carattere compensa un fisico debole: è infatti affetta da spina bifida, che i genitori e le persone intorno a lei scambiano per poliomielite, non riuscendola così a curare nel modo adeguato.

2. La prova più dura per Frida arriva però nel 1925. Un giorno, mentre torna da scuola in autobus viene coinvolta in un terribile incidente che le causa la frattura multipla della spina dorsale, di parecchie vertebre e del bacino. Rischia di morire e si salva solo sottoponendosi a 32 interventi chirurgici che la costringono a letto per mesi.

Ha solo 18 anni e le ferite al fisico la faranno soffrire per tutta la vita, compromettendo irrimediabilmente la sua mobilità.

3. Durante i mesi a letto immobilizzata da busti di metallo e gessi, i genitori le regalano colori e pennelli per aiutarla a passare le lunghe giornate. Questo regalo darà avvio ad una sfolgorante carriera artistica.

La prima opera di Frida è un autoritratto (a cui ne seguiranno molti altri) che dona ad un ragazzo di cui è innamorata.

4. I genitori incoraggiano sin da subito questa passione per l’arte, tanto da istallare uno specchio sul soffitto della camera di Frida, così che possa ritrarsi nei lunghi pomeriggi solitari. È questo il motivo dei numerosi autoritratti dell’artista. Lei stessa dirà: “Dipingo autoritratti perché sono spesso sola, perché sono la persona che conosco meglio”.

5. Frida Kahlo nel 1928, a 21 anni, si iscrive al partito comunista messicano, diventando una convinta attivista. È in quell’anno che conosce Diego Rivera, il pittore più famoso del Messico rivoluzionario. Lo aveva incontrato per la prima volta quando aveva solo quindici anni (e lui trentasei), sotto i ponteggi della scuola nazionale preparatoria, mentre Diego stava dipingendo un murale per l’auditorium della scuola.

6. Nel 1929 sposa Diego, nonostante lui abbia 21 anni più di lei e sia già al terzo matrimonio. Inoltre Diego ha fama di “donnaiolo” e marito infedele. Il loro sarà un rapporto fatto di arte, tradimenti, passione e pistole. Lei stessa dirà: “Ho subito due gravi incidenti nella mia vita… il primo è stato quando un tram mi ha travolto e il secondo è stato Diego Rivera.”

7. Frida Kahlo ha avuto molti amanti (uomini e donne), tra cui il rivoluzionario russo Lev Trotsky e il poeta André Breton, ma non riuscì mai ad avere figli, a causa del suo fisico compromesso dall’incidente. Quando rimase incinta del primo figlio, Frida fece di tutto per portare avanti la gravidanza. Si dovette arrendere solo quando i medici la costrinsero ad abortire per evitare che perdessero la vita sia lei che il bambino.

8. Frida Kahlo e Diego potevano considerarsi una “coppia aperta”, più per le infedeltà di Diego che per scelta di Frida, che soffrì molto per i tradimenti del marito che ebbe persino una relazione con la sorella minore di Frida, Cristina.

Vista l’impossibilità di fare affidamento sulla fedeltà di Diego, i due decisero di vivere in case separate, unite tra loro da un piccolo ponte, in modo che ognuno di loro potesse avere il proprio spazio “artistico”.

9. Le opere di Frida kahlo sono spesso state accostate al movimento Surrealista, ma Frida ha sempre rifiutato tale vicinanza sostenendo: “Ho sempre dipinto la mia realtà, non i miei sogni”.

10. L’album dei Coldplay Viva la vida or Death and All His Friends (2008) si ispira ad una celebre frase che la Kahlo scrisse sul suo ultimo quadro, otto giorni prima della sua morte a soli 47 anni per cause ancora non del tutto certe.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Yaoi is bad and will be abolished under socialism" - Lev Trotsky

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

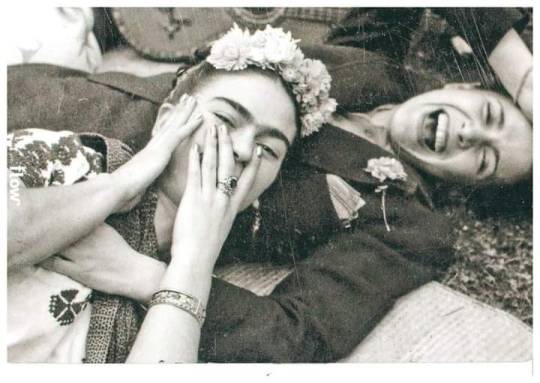

CARTA DE LEÓN TROTSKY A FRIDA KAHLO

Frida, amada:

Al contemplar esta noche tu rostro de cervatillo he descubierto que jamás conseguiré hacerte a un lado de mi cabeza no se diga de mi Corazón. Arde mi sangre como una lámpara votiva al lado de mi mesa, y es como un cerrojo (parte ilegible en el original) una noche en Collooacan. Dejo este papel debajo de tu puerta. Y debo volver a aclarar que no hubo diferencias entre nosotros. Ni la espina dorsal abre un surco insalvable en los hemisferios de una espalda. Me cuesta precisar en cualquier caso, tal vez por mi alma eslava, si ese espacio abierto entre nosotros podra cerrarse y cicatrizar.

Te amé desde siempre y a escondidas. Me encontraba dueño de un juego de principios en los que me arrellanaba como un castor, y esquivaba el fantasma de tu bigote, tu porte de soldadera y esa sed de besos capaz de (parte illegible en el original).

He pagado con creces ese acto de soberbia, el hacerte mía. Yo viví una de esas desafortunadas juventudes, y a tu lado he volado como el pájaráo que vuela por el solo placer de volar, Frida (parte ilegible en el original) alli donde se supone que se enciende el fuego originario, pronto fueron rumores.

Con lo que me duele. Я оставляю в руках Диего одиозной? ("¿Debo dejarte en las odiosas manos de Diego?". En ruso, en el original)... Cuando llegue la hora de los blogs, que tu y yo no veremos, sospecho que tu rostro anti virginal desafíara las leyes del no logo. Y profetizo que en un remoto lugar se verá multiplicado tu entrecejo, a esperar la llegada del olvido que tardará, como yo mismo me demoro en dejar este beso a tu figura inmortal. Frida, Frida…

Tuyo,

Lev T.

Лев Давидович Бронштейн

Fuente: Las cuatro esquinas, una intersección literaria

Imagen de la red

Frida Kahlo y Léon Trotsky en 1937.

Foto: Autor desconocido.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

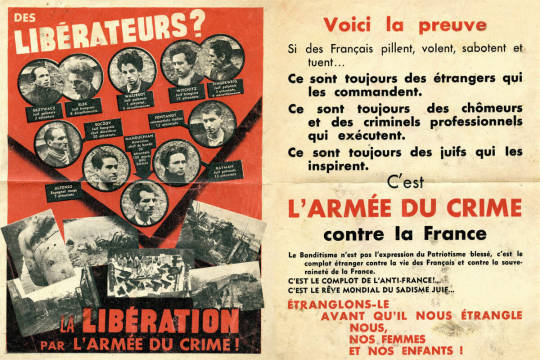

Il faut prendre le temps de lire le sermon de Macron, lu hier au Panthéon, à propos de ce terroriste communiste, le métèque Manouchian.

Quelques uns ont peut-être entendu, de loin, ce mauvais acteur de théâtre coaché par Brigitte, mais personne, ou presque, n’a lu à tête reposée les énormités qu’il a débitées.

Allons aux passages les plus mirobolants.

Élysée.fr :

Est-ce donc ainsi que les Hommes vivent ?

Des dernières heures, dans la clairière du Mont-Valérien, à cette Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, une odyssée du vingtième siècle s’achève, celle d’un destin de liberté qui, depuis Adyiaman, survivant au génocide de 1915, de famille arménienne en famille kurde, trouvant refuge au Liban avant de rejoindre la France, décide de mourir pour notre Nation qui, pourtant, avait refusé de l’adopter pleinement.

Le tableau est planté. Le métèque, héroïque, est le « patriote », bien que par définition la patrie est la terre des pères, propriété exclusive des autochtones. Dans la foulée, Macron fait d’emblée peser l’accusation sur les Français d’alors, et en filigrane ceux d’aujourd’hui, qui manquaient d’enthousiasme face aux flots de rastaquouères qui, déjà, se bousculaient en France.

Dans une inversion remarquable, la soi-disant « résistance », pourtant longtemps présentée aux masses (mensongèrement) comme le parti des autochtones qui voulaient que les Français restent les maîtres chez eux et chassent l’occupant étranger, devient le symbole de l’étranger qui résiste à l’autochtone, frappé de suspicion.

On le comprend : cette mise en scène voulue par le pouvoir est une mise en accusation formelle des Français de sang.

Reconnaissance en ce jour d’un destin européen, du Caucase au Panthéon, et avec lui, de cette Internationale de la liberté et du courage. Oui, cette odyssée, celle de Manouchian et de tous ses compagnons d’armes, est aussi la nôtre, odyssée de la Liberté, et de sa part ineffaçable dans le cœur de notre Nation. Reconnaissance, en cette heure, de leur part de Résistance, six décennies après Jean Moulin.

En un paragraphe, un jet d’énormités mêlées de crachats, d’une facture si caractéristique que l’on sait que la main qui l’a rédigé est juive.

On découvre un « destin européen » prêté à un immigré arménien encarté au Parti Communiste, satellite français de l’Union Soviétique dont l’unique horizon était pourtant la dictature mondiale du « prolétariat », pas « l’Europe ». Un satellite caporalisé par les commissaires politiques juifs au sein du Komintern, l’internationale communiste, fondée par le juif Zinoviev.

Grigori Zinoviev, avant sa liquidation par Staline en 1936. Il fomentait un coup d’état en coordination avec le juif Lev Bronstein dit « Trotsky ».

Les « compagnons » de Manouchian – les Francs-Tireurs Partisans – Main d’Oeuvre Immigrée – dont parle Macron sont pour l’essentiel des juifs, partisans de la révolution mondiale qui doit abattre les nations.

Cette « internationale de la liberté et du courage », armée et commandée à l’époque par les juifs du Kremlin pour les besoins de leur révolution planétaire, a désormais « une part ineffaçable dans le coeur » de la nation française.

Par un tour de passe-passe, et avec l’aide d’une république prédisposée depuis sa fondation, la nation française deviendrait le « coeur » de l’internationalisme juif.

Est-ce ainsi que les Hommes vivent ? Oui, s’ils sont libres. Libre, Missak Manouchian l’était, quand il gravissait la rue Soufflot, en fixant ce Panthéon qui l’accueille aujourd’hui. Libre, sur les bancs de la bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève à quelques mètres d’ici, découvrant notre littérature et polissant ses idéaux. Libre avec Baudelaire, dans le vert paradis qui avait le goût de son enfance, dans une Arménie heureuse, celle des montagnes, des torrents et du soleil. Libre avec Verlaine, dont les fantômes saturniens croisaient les siens : son père, Kévork, tué les armes à la main par des soldats ottomans, sous ses yeux d’enfant, sa mère Vartouhi, morte de faim, de maladie, victimes du génocide des Arméniens, spectres qui vont hanter sa vie.

Libre avec Rimbaud, après une saison en enfer, souvenirs partagés avec son frère Garabed. Mais voici les illuminations, les Lumières, celle qu’un instituteur de l’orphelinat, au Liban, lui enseigna. Eveil à la langue et à la culture françaises. Libre avec Victor Hugo et la légende des siècles, gloire de sa libre patrie, la France, terre d’accueil pour les misérables, vers laquelle Missak l’apatride choisit à dix-huit ans de s’embarquer, ivre, écrivait-il « d’un grand rêve de liberté ».

La France, terre promise des métèques depuis Rousseau.

S’ils y gagnent « la liberté », les autochtones, eux, récoltent de les subir à perpétuité.

Lui, Missak, « maraudeur, étranger, malhabile » pour reprendre les mots d’un autre poète, combattant qui choisit la France, Guillaume Apollinaire. Etranger, orphelin, bientôt en deuil de son frère tombé malade, et pourtant à la tâche, ouvrier chez Citroën, quai de Javel, licencié soudain, tremblant parfois de froid et de faim.

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes vivent ? Ainsi, le soir après l’usine, Missak Manouchian étudie. Ainsi, sous les rayonnages de livres, Missak Manouchian traduit les poètes français en arménien. Ainsi écrit-il lui-même. Mots de mélancolie, de privations, brûlés du froid des hivers parisiens. Mots d’espoir aussi rendus plus chauds par la fraternité des exilés, par la solidarité de la diaspora arménienne, par le foisonnement d’art et de musique, des revues et des cours en Sorbonne.

Manouchian, le migrant.

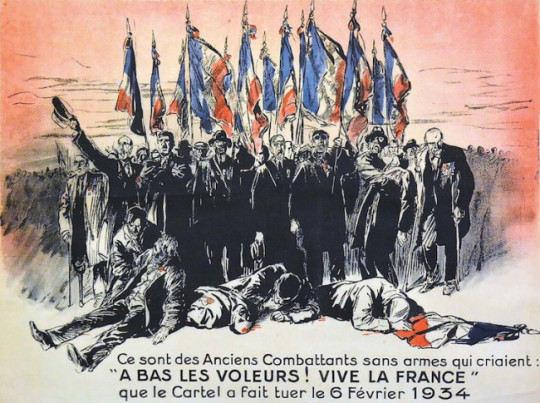

Poète et révolté. Quand les ligues fascistes défilent en 1934 au cœur de Paris, Missak Manouchian voit revivre sous ses yeux le poison de l’ignorance et les mensonges raciaux qui précipitèrent en Arménie sa famille à la mort.

Mensonges raciaux !

Nous y voilà.

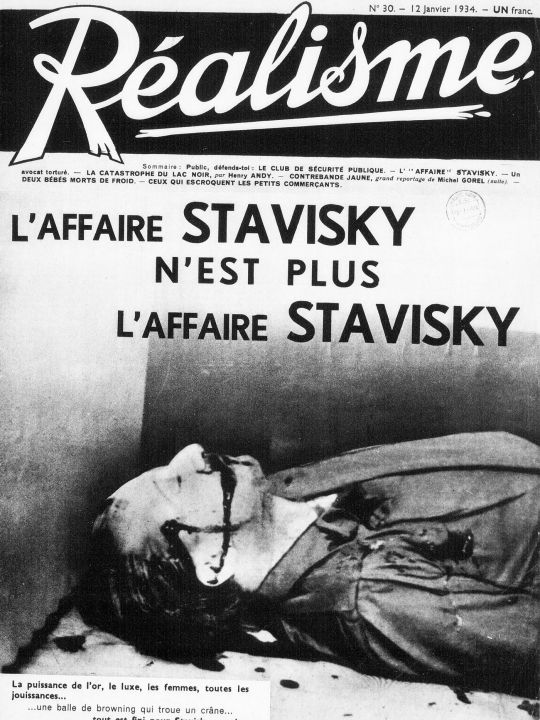

Pourtant le juif Stavisky, à l’origine du séisme de 1934, tendait à confirmer bon nombre d’observations faites à propos de la race juive, race menteuse, voleuse, agioteuse, perfide.

Et oui, il y avait encore des Français en France, révoltés, prêts au coup d’état. Ce n’est pas la révolution marxiste chère à Macron, mais celle des vétérans de 1914-1918, revenus du front, qui constatent, 16 ans après une « victoire » illusoire, que la vermine démocratique a prospéré du carnage.

Et Manouchian, le métèque venu de son Arménie célébré par Macron, a, d’après la voix présidentielle, part sur les vétérans du front, du seul fait qu’en France, depuis 1789, le métèque est roi et l’autochtone, traité en chien.

Manouchian, à peine débarqué en France, a les Français dans le nez, ne goûte pas du tout que les survivants des tranchées aspirent à reprendre leur pays des mains juives qui corrompent tout. Il est décidé à leur donner une leçon, comme tout patriote français qui se respecte, en rejoignant le Parti Communiste, cinquième colonne à la botte des juifs de Moscou en France.

Ne serait-ce pas ce qu’aurait fait Jeanne d’Arc à la vue des royalistes dans les rues de Paris ?

Macron en est convaincu, c’est là la plus solide preuve de la francité de Manouchian le manouche.

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes vivent ? Non. Alors, Missak Manouchian embrasse l’idéal communiste. Convaincu que jamais en France on n’a pu impunément séparer République et Révolution. Après 1789, après 1793, il rêve l’émancipation universelle pour les damnés de la terre. C’est ainsi que Missak Manouchian s’engage contre le fascisme, au sein de l’Internationale communiste, et bientôt à la tête d’une revue, Zangou, du nom d’une rivière d’Arménie. Espoir du Front Populaire, volonté d’entrer dans les Brigades Internationales pour l’Espagne, action militante.

Un autre paragraphe extraordinaire : Macron se fait l’adepte de « l’idéal communiste », celui de Lénine et de Staline, de l’Holodomor donc – en plein soutien à l’Ukraine -, puisque c’est de cela qu’il s’agit à l’époque de Manouchian, non sans passer par la Terreur de 1793.

Pour « libérer » la France des Français.

Quelqu’un mesure-t-il l’insanité de ces propos ?

Surtout, quelqu’un comprend-il qu’ils ont été écrits par des juifs qui, plus que jamais, mènent leur guerre raciale par procuration grâce à l’arme de l’immigration ?

C’est ainsi que Missak Manouchian trouve l’amour : Mélinée, enfant du génocide des Arméniens comme lui ; Mélinée, protégée par l’amitié de ses logeurs, les Aznavourian, parents de Charles, dix ans alors, déjà chanteur. L’amour, malgré le dénuement, ignorer le passé, conjuguer le futur, l’amour fou. Je vous parle d’un temps que ces gens de vingt ans, Missak et Mélinée, ont tant aimé connaître.

Charles Aznavour.

Encore un métèque, plus français que quiconque, mais planqué en Suisse, sur ses montagnes d’or, non sans appeler, jusqu’à la fin, à l’immigration totale.

Libres en France, ce pays que Missak a choisi adolescent, qui lui a offert des mots pour rêver, un refuge pour se relever, une culture pour s’émanciper. Alors, Missak Manouchian hisse haut notre drapeau tricolore, lors des 150 ans de la Révolution, en 1939, quand il défile dans le stade de Montrouge. Alors, pour servir ce drapeau, Missak Manouchian demande par deux fois à devenir Français. En vain, car la France avait oublié sa vocation d’asile aux persécutés.

Même la France du Front Populaire (!) était donc xénophobe, frileuse. Heureusement que Macron, lui, est audacieux. Avec 500,000 migrants supplémentaires par an, l’asile n’a plus de mystère pour lui.

Alors, quand la guerre éclate, Missak Manouchian veut s’engager. Ivre de liberté, enivré de courage, enragé de défendre le pays qui lui a tout donné. « Tigre enchaîné », selon ses mots de poète, dans les prisons où le jettent la peur des étrangers, la peur des communistes, sous les miradors du camp allemand où il est détenu, en 1941, et où Mélinée vient contre tous les périls lui apporter des vivres.

C’est que la « peur des communistes », qui avait justifié une première arrestation, le 2 septembre 1939, n’avait pas grand chose à voir avec les Allemands, mais tout avec l’interdiction du Parti Communiste qui devait suivre, le 26 septembre 1939, pour intelligence avec l’ennemi, en l’occurrence l’Allemagne.

Le 23 août précédent, 10 jours avant le début de la guerre, Molotov, ministre des Affaires étrangères de l’URSS, avait signé un pacte de non-agression avec son homologue allemand, Ribbentrop, afin d’oeuvrer, pensait-on à Moscou, à une guerre intra-occidentale dont Staline deviendrait l’arbitre, une fois les belligérants épuisés.

Macron ne parle pas de cette interdiction du Parti Communiste par la Troisième République pour trahison, ni de l’arrestation de Manouchian au nom de cette interdiction pour collaboration avec l’Allemagne contre l’effort de guerre français au profit d’une puissance étrangère, l’URSS. Il ne parle que de sa brève incarcération, à l’été 1941, avant d’être libéré par les Allemands.

Manouchian était simplement un patriote français, trop patriote pour la France du Front Populaire, foncièrement xénophobe, et il agissait par idéal en rejoignant une organisation, le Parti Communiste, dont les crimes, en 23 ans d’existence, étaient abondamment documentés.

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes vivent ? Oui, au prix du choix délibéré, déterminé, répété de la liberté. Car dans Paris occupé, Missak Manouchian rejoint la résistance communiste, au sein de la main d’œuvre immigrée, la MOI. Il se voulait poète, il devient soldat de l’ombre, plongé dans l’enfer d’une vie clandestine, une vie vouée à faire de Paris un enfer pour les soldats allemands. Guerre psychologique pour signifier à l’occupant que les Français n’ont rien abdiqué de leur liberté. Encore, toujours, « ivre d’un grand rêve de liberté », Missak Manouchian prend tous les risques. Lui qui aime aimer se résout à tuer. Comme ce jour de mars 1943 où il lance une grenade dans les rangs d’un détachement allemand.

C’est sûr, l’arménien Manouchian et ses comparses juifs de Hongrie, de Roumanie, de Pologne étaient décidés à « signifier que les Français n’ont rien abdiqué de leur liberté ».

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes rêvent ? Oui, les armes à la main. Et d’autres sont là, à ses côtés, parce qu’ils sont chassés de la surface du monde et ont décidé de se battre pour le sol de la patrie. Parce que nombre d’entre eux sont Juifs, et que certains ont vu leurs proches déportés : Lebj Goldberg, Maurice Fingercweig, Marcel Rajman. Parce ce que la guerre a volé leurs écoles et leurs ateliers, dans ce Paris populaire et ouvrier où le français se mêle à l’italien ou au yiddish. Parce que les forces de haine ont volé leur passé, là-bas, en Arménie, tel Armenak Manoukian. Parce que ce sont les femmes qui veulent œuvrer pour l’avenir de l’Homme, comme Mélinée, comme la Roumaine Golda Bancic, comme tant d’autres, armes et bombes qu’elles acheminent sans soupçons, filatures qu’elles accomplissent sans trembler. Parce qu’ils sont une bande de copains, à la vie, à la mort.

Pour Macron et son régime, le terrorisme, s’il est juif, devient une nécessité vitale. C’est ce que l’on avait compris depuis le 7 octobre dernier, en effet.

A l’âge des serments invincibles, tels Thomas Elek et Wolf Wajsbrot, une belle équipe comme sur un terrain de football, panache de Rino della Negra, jeune espoir alors du Red Star. Parce qu’ils ont vu mourir la liberté dans l’Italie de leurs parents, comme Antoine Salvadori, Cesare Luccarini, Amedeo Usseglio, Spartaco Fontano. Parce qu’ils ont vu les hommes de fer s’emparer de la Pologne et persécuter les Juifs, comme Jonas Geduldig, Salomon Schapira et Szlama Grzywacz. Parce qu’ils sont pour beaucoup des anciens des Brigades Internationales en Espagne, pays de Celestino Alfonso. Pour qui sonne le glas ? Pour les Polonais Joseph Epstein et Stanislas Kubacki. Pour les Hongrois Joseph Boczov et Emeric Glasz, eux les experts en sabotage, aux fardeaux de dynamite. Parce qu’ils ont vingt ans, le temps d’apprendre à vivre, le temps d’apprendre à se battre. Ainsi de ces Français refusant le STO, Roger Rouxel, Roger Cloarec et Robert Witchitz.

Parce qu’ils sont communistes, ils ne connaissent rien d’autre que la fraternité humaine, enfants de la Révolution française, guetteurs de la Révolution universelle. Ces 24 noms sont ceux-là, que simplement je cite, mais avec eux tout le cortège des FTP-MOI trop longtemps confinés dans l’oubli.

Il faut vraiment lire et relire ces déclarations, écrites par les juifs.

Macron est spirituellement marxiste et concrètement banquier.

Comme tout juif qui se respecte.

Il a été à bonne école, l’école Rothschild.

Oui, parce qu’à prononcer leurs noms sont difficiles, parce qu’ils multiplient les déraillements de train et les attaques contre les nazis, parce que ces combattants sont parvenus à exécuter un haut dignitaire du Reich, les voilà plus traqués que jamais. Dans leurs pas, marchent les inspecteurs de la préfecture de police – la police qui collabore, la police de Bousquet, de Laval, de Pétain – et l’ombre des rafles grandit.

À l’automne 1943, devenu dirigeant militaire des FTP-MOI parisiens, Missak Manouchian le pressent : la fin approche. Pour alerter ses camarades, il se rend au rendez-vous fixé avec son supérieur Joseph Epstein, un matin de novembre. Missak Manouchian avait vu juste : lui et ses camarades sont pris, torturés, jugés dans un procès de propagande organisé par les nazis en février 1944.

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes vivent ? S’ils sont résolument libres, oui. À la barre du tribunal, ils endossent fièrement ce dont leurs juges nazis les accablent, leurs actes, leur communisme, leur vie de Juifs, d’étrangers, insolents, tranquilles, libres. « Vous avez hérité de la nationalité française » lance Missak Manouchian aux policiers collaborateurs. « Nous, nous l’avons méritée ».

« Pousse-toi de là que je m’y mette » est en effet l’attitude récurrent de toute la vermine étrangère que le régime républicain a établi en France depuis un siècle.

Etrangers et nos frères pourtant, Français de préférence, Français d’espérance. Comme les pêcheurs de l’Ile de Sein, comme d’autres jeunes de seize ans, de vingt ans, de trente ans, comme les ombres des maquis de Corrèze, les combattants de Koufra ou les assiégés du Vercors. Français de naissance, Français d’espérance. Ceux qui croyaient au ciel, ceux qui n’y croyaient pas, ceux qui défendaient les Lumières et ne se dérobèrent pas.

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes meurent ? Ce 21 février 1944, ceux-là affrontent la mort. Dans la clairière du Mont Valérien, Missak Manouchian a le cœur qui se fend. Le lendemain, c’est l’anniversaire de son mariage avec Mélinée. Ils n’auront pas d’enfants mais elle aura la vie devant elle. Il vient de tracer ses mots d’amour sur le papier, amour d’une femme jusqu’au don de l’avenir, amour de la France jusqu’au don de sa vie, amour des peuples jusqu’au don du pardon.

« Aujourd’hui, il y a du soleil ». Missak Manouchian est à ce point libre et confiant dans le genre humain qu’il n’est plus que volonté, volonté d’amour. Délié du ressentiment, affranchi du désespoir, certain que le siècle lui rendra justice comme il le fait aujourd’hui, que ses bourreaux seront défaits et que l’humanité triomphera. Car qui meurt pour la liberté universelle a toujours raison devant l’Histoire.

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes meurent ? En tout cas les Hommes libres. En tout cas ces Français d’espérance. « Je ne suis qu’un soldat qui meurt pour la France. Je sais pourquoi je meurs et j’en suis très fier », écrira l’Espagnol Celestino Alfonso avant l’exécution. Et ce 21 février 1944, ce sont bien vingt-deux pactes de sang versé, scellés entre ces destins et la liberté de la France.

Pacte scellé par le sang du sacrifice. Un peu avant, avec la force que leur laissent les mois de torture, ils ont crié, « À bas les nazis, vive le peuple allemand ». Conduits aux poteaux, quatre par quatre, les yeux bandés sauf ceux qui le refusent, tombés, les corps déchiquetés, en six salves. Tombés, comme tombera, fusillé en avril au Mont-Valérien, Joseph Epstein, qui sous la torture ne donnera aucun nom, pas même le sien, démontrant jusqu’au bout son courage. Tombés, comme tombera, tranchée la tête de Golda Bancic, exécutée en mai à l’abri des regards dans une prison de Stuttgart.

Tombés, ils sont tombés et leurs bourreaux voulurent les exécuter à nouveau par la calomnie de la propagande, cette Affiche Rouge qui voulait exciter les peurs et ne fortifia que l’amour. Car les vrais patriotes reconnurent dans ce rouge, le rouge du Tricolore. Rouge des premiers uniformes des soldats de Quatorze, rouge des matins de Valmy, rouge du sang versé pour la France sur lequel miroite toujours une larme de bleu, un éclat de blanc.

C’est ainsi que les hommes, par-delà la mort, survivent. Ils débordent l’existence par la mémoire. Par les vers d’Aragon, par les chansons, celle de Léo Ferré et tant d’autres. Mémoire portée fidèlement par Arsène Tchakarian, ancien des FTP-Moi ou par Antoine Bagdikian, l’un et l’autre dévoués à honorer d’un même élan la Résistance des Arméniens et la Résistance des Juifs en France, portée par tant de passeurs inlassables.

Aragon, communiste, écrivait dans Les enfants rouges (1932), publié par les presses du Parti Communiste :

Les trois couleurs à la voirie !

Le drapeau rouge est le meilleur !

Leur France, Jeune Travailleur,

N’est aucunement ta patrie

Le rouge du communisme est le rouge du tricolore et des poilus. En fait, tout le monde en France a toujours été communiste, c’est simplement que nous avions besoin des juifs pour le savoir et de Macron pour le dire.

C’est ainsi que les hommes survivent. C’est ainsi que les Grands Hommes, en France, vivent pour l’éternité.

Entrent aujourd’hui au Panthéon vingt-quatre visages parmi ceux des FTP-MOI. Vingt-quatre visages parmi les centaines de combattants et otages, fusillés comme eux dans la clairière du Mont-Valérien, que j’ai décidé de tous reconnaître comme morts pour la France. Oui, la France de 2024 se devait d’honorer ceux qui furent vingt-quatre fois la France. Les honorer dans nos cœurs, dans notre recueillement, dans l’esprit des jeunes Français venus ici pour songer à cette autre jeunesse passée avant elle, étrangère, juive, communiste, résistante, jeunesse de France, gardienne d’une part de la noblesse du monde.

Les juifs, la noblesse du monde.

Missak Manouchian, vous entrez ici en soldat, avec vos camarades, ceux de l’Affiche, du Mont-Valérien, avec Golda, avec Joseph et avec tous vos frères d’armes morts pour la France. Vous rejoignez avec eux les Résistants au Panthéon. L’ordre de la nuit est désormais complet.

Missak Manouchian, vous entrez ici toujours ivre de vos rêves : l’Arménie délivrée du chagrin, l’Europe fraternelle, l’idéal communiste, la justice, la dignité, l’humanité, rêves français, rêves universels.

Missak Manouchian, vous entrez ici avec Mélinée. En poète qui dit l’amour heureux. Amour de la Liberté malgré les prisons, la torture et la mort ; amour de la France, malgré les refus, les trahisons ; amour des Hommes, de ceux qui sont morts et de ceux qui sont à naître.

Aujourd’hui, ce n’est plus le soleil d’hiver sur la colline ; il pleut sur Paris et la France, reconnaissante, vous accueille. Missak et Mélinée, destins d’Arménie et de France, amour enfin retrouvé. Missak, les vingt et trois, et avec eux tous les autres, enfin célébrés. L’amour et la liberté, pour l’éternité.

Vive la République. Vive la France.

Quelle nausée formidable.

Tout d’abord, ce numéro de cirque mémoriel ne touche qu’un seul public, un public du passé : les boomers, nés après-guerre, formatés par l’antifascisme d’état et son mythe résistantialiste. Pour Macron et sa clique, il s’agit de recréer un semblant d’unité face à la balkanisation généralisée de la société, balkanisation rendue possible par la politique soutenue par les Boomers pendant 50 ans. Derrière une « unité » d’apparence patriotique avec force Marseillaise et flonflons, ce numéro de cirque était d’essence profondément juive, cosmopolite, anti-française, haineuse de l’autochtone. C’est une démonstration de force du parti de l’étranger, identique à la marche des juifs « contre l’antisémitisme ». Paradoxalement, cette opération politico-médiatique conçue par les juifs pour délégitimer les autochtones au profit des immigrés, subliminalement incarné par Manouchian, n’a intéressé que les vieux Blancs, les banlieues ethniques étant complètement indifférentes à ces histoires.

La seconde leçon, c’est que le révisionnisme historique est essentiel dans la déconstruction de ce système foncièrement sémitique. Sans une revue critique des mythes et mensonges historiques martelés par le système, singulièrement ceux, fondateurs, de 1945, aucune action révolutionnaire ne peut être entreprise pour stopper ce système anti-Blancs. La reconnaissance par le RN de la légitimité de l’action des assassins – principalement juifs (plus de la moitié des FTP-MOI) – du Parti Communiste contre les forces nationalistes et l’acceptation de sa victoire politique, idéologique et culturelle après 1944 condamne le RN à n’être qu’une force d’appoint du système, comme jadis le parti gaulliste. La participation du RN à la cérémonie organisée pour le juif Badinter, destructeur du système judiciaire français au profit de la racaille immigrée, annonçait déjà cette subordination complète.

Le troisième point, c’est que, malgré le cirque médiatique, le marxisme international organisé a été irrémédiablement détruit avec l’effondrement de l’Union Soviétique. Si en France ses miasmes continuent de fermenter dans les syndicats, le show business ou l’Éducation Nationale, sa puissance n’a plus rien de commun avec la formidable organisation mondiale qu’il était au siècle dernier. Ce n’est pas Fabien Roussel, partisan de l’OTAN, ou Sophie Binet, d’une CGT groupusculaire, qui feront illusion, pas plus que trotskiste Usul. Le Parti Communiste est si négligeable que Mélenchon, ex-trotskiste et entouré de trotskistes, peut récupérer sans difficulté Manouchian, membre du PC stalinien, pour les besoins de sa retape. Ne pouvant plus aspirer au pouvoir depuis longtemps, dépourvu d’une grande puissance pour le soutenir, ce qu’il reste du marxisme peut être digéré par le système macroniste, appendice de la finance internationale. On voit d’ailleurs à cette occasion comment le marxisme, par son internationalisme corrosif, est parfaitement compatible avec la démocratie financière qui veut abattre nations et frontières grâce à l’immigration. Le fanatisme immigrationniste est bien le dénominateur commun de la bourgeoisie macroniste et de l’extrême-gauche comme cette cérémonie le démontre.

Le quatrième point, plus prosaïque, est d’ordre ethnique. Ces arméniens qui appellent constamment à l’aide pour qu’on les soutienne militairement face à l’Azerbaïdjan et la Turquie sont ceux qui, depuis plus d’un siècle, ont servi de supplétifs aux juifs dans leur guerre contre les Blancs en France. Ces arméniens, à l’image de Manouchian, doivent être récompensés de leurs efforts. Une telle constance mérite salaire. L’attitude nationaliste correcte consiste à soutenir la destruction de l’Arménie qui a appuyé l’effroyable guerre raciale menée par les juifs dans nos rues. La carcasse de Manouchian peut bien être au Panthéon, nous sommes bien vivants et nous avons des comptes à régler avec ces arméniens en leur qualité de fourriers des juifs. L’instrument providentiel de cette vengeance impitoyable assiège actuellement la patrie de ces chiens, j’ai nommé l’Azerbaïdjan. Le plus drôle étant que c’est Israël qui arme cet état contre les arméniens, décidément fort peu doués de flair. Les descendants des arméniens rouges d’hier peuvent bien agiter leur croix, ils ne doivent trouver qu’une porte close à leur supplication.

Bien sûr, il ne faut pas grossir démesurément ce qui n’est qu’une campagne de propagande juive guidée par la peur et la conscience que le pouvoir juif vacille. Cependant, dans la longue guerre que les juifs nous font, il faut voir clair et viser juste. Il faut également se sortir de la cage mentale de facture hébraïque dans laquelle cette race maudite tente de nous maintenir à tout prix.

Quant à ce Panthéon, catacombe de la Judée militante, sa vocation est d’être peuplé de nègres sous crack.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

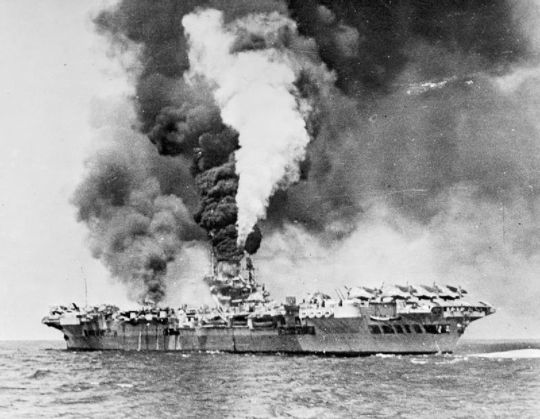

Forgotten Ukrainian-Jewish hero: Israel Ilyich Fisanovich (1914-44), Soviet submarine commander in World War II, Hero of the Soviet Union. He was born in Elizavetograd (later Soviet Kirovograd, now Ukrainian Kropyvnytskyi) to a working-class Jewish family. He joined the Red Fleet in 1932 and by 1938 was a submarine commander in the Baltic. Between 1941 and 1944 he sank two German warships, 10 transports and a tanker. In 1942 he was awarded the Order of Lenin and named a Hero of the Soviet Union. In July 1944 he was tragically killed when a British aircraft sank his submarine mistaking it for a German U-boat.

Fisanovich's Jewish identity was well-known - from 1942 he was a member of the Presidium of the Soviet Union's Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (EAK). After 1945 Stalin's regime became increasingly antisemitic, but during the war many Jews had distinguished military careers. Among them were Major-General Lev Dovator (1903-41), General Ivan Chernyakhovsky (1907-45), General Aaron Katz (1901-71) and General Naum Eitingon (1899-1981), an NKVD General who (among many other things) organised the assassination of Leon Trotsky in 1940. After the war Eitingon had the distinction of being arrested twice, first by Beria as an alleged Zionist plotter, and then after 1953 as an accomplice of Beria.

May his memory be for a blessing.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

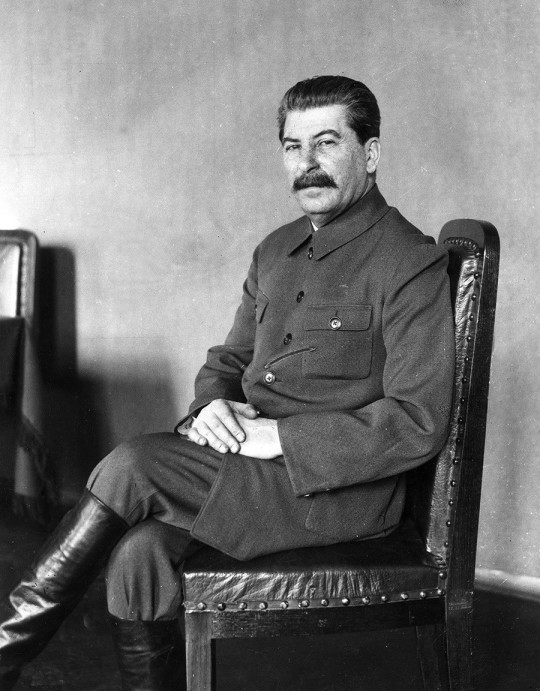

March 5 marks 70 years since Joseph Stalin died. As the leader of the USSR from 1924 to his death in 1953, Stalin established a totalitarian regime, provoked mass starvation, engineered the Great Terror, and led the Soviet Union to victory in the Second World War. Meduza spoke to Professor Ronald Grigor Suny, a historian and political scientist at the University of Michigan, and author of several books about Stalin and Stalinism, about Stalin’s politics and his rise to power in the early years of the USSR. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Who was Stalin before the 1917 revolution?

Stalin was born a very poor person, and he developed in time into what I would call an outlaw. He began as a relatively religious person, as a young man. He was a romantic poet. He wrote poems in Georgian that were considered quite good. He went to seminary following his mother's instructions and desires.

And then in that seminary, which produced, in some ways, more revolutionaries than priests, he became alienated from the tsarist regime and from the church and imbibed the local dissident ideology, which was a kind of Marxism. Very strangely, in Georgia, instead of nationalism being the dominant appeal to young people in the 1890s, there was this very powerful and influential Marxist movement led by a guy named Noe Žordania. And Stalin became part of that movement.

But as a young man, he was quite militant. He had his own desires. He was a rough guy, sort of a street fighter, and eventually he gravitated toward the more militant wing of social democracy in tsarist Russia, that is Bolshevism. There were aspects of his revolutionary experience before 1917 that already pre-visioned the kind of person he would be. He was a manipulator, he was pragmatic, he was Machiavellian, he did anything to further the cause. And he identified himself with that cause. So there was always this strange combination of the need to create a revolution and [the need] to promote himself, Stalin.

Could his comrades have guessed back then that he would advance so far in the ranks of the party?

Many historians who don't follow his early biography [closely] have underestimated Stalin. They see him as a minor leader, someone from the provinces, not very important. This is, I think, incorrect. When you look within the context in which he was operating, in what was called the Caucasus, Transcaucasia, or we now call it the South Caucasus, you see he was a leader there. In the Bolshevik faction, he was a major player. And we have letters and statements by local Bolsheviks at the time and by Social Democrats of the Menshevik variety, all of which note several traits: He's a good organizer, he's a good propagandist, he wrote influential pieces on anarchism and Marxism, and that he was also a manipulator, maybe not to be trusted. So he was a kind of outlaw figure, but also recognized as a potential leader.

[But] I agree that, if you take the whole Bolshevik party, he was a minor leader. Lenin promoted him and recognized his skills. Lenin was looking for Social Democrats who had come from the lower classes, not primarily from the intelligentsia, but who also were intellectual in some ways — this combination of the worker and the intelligentsia. And Stalin perfectly personified that. But he was not a major second-to-Lenin figure. The second-to-Lenin figures were people whom [Stalin] would murder — Zinoviev, Kamenev, Trotsky, Bukharin.

Who were the second-to-Lenin figures?

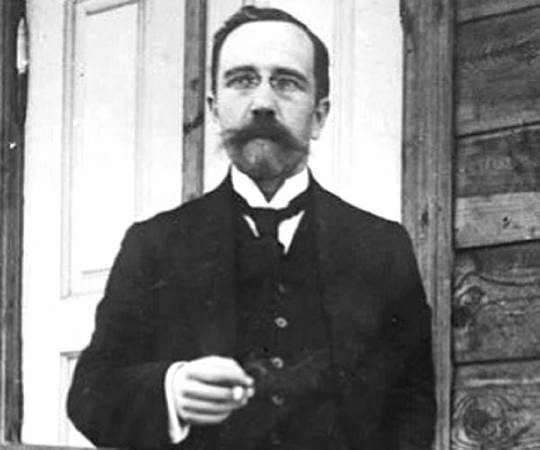

Grigory Zinoviev was a so-called Old Bolshevik, a close comrade of Lenin’s from the early days of the revolution.

Lev Kamenev was a revolutionary who participated in the failed 1905 revolution and an associate of Lenin. He argued with Lenin about the 1917 revolution, but nonetheless remained in a position of power in the early Soviet period. With Zinoviev and Stalin, he formed a troika against Trotsky.

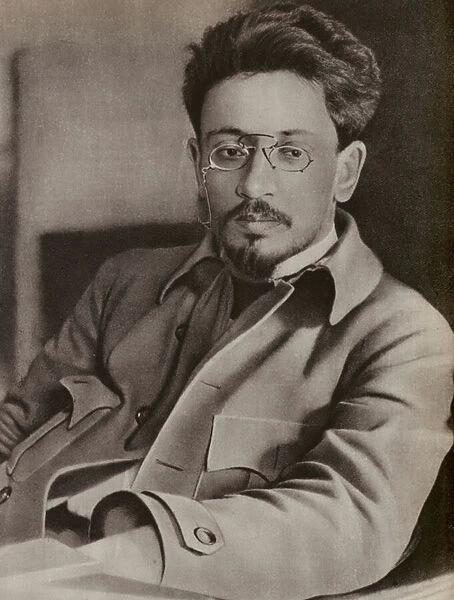

Lev Trotsky, revolutionary and political theorist, initially sided with the Mensheviks. He nonetheless held powerful positions in Soviet government until after Lenin’s death, when Stalin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev forced him out.

Nikolai Bukharin was close to Lenin and Trotsky before the revolution, when the when the three worked together from exile. After the revolution, he became the editor of the newspaper Pravda. He helped Stalin oust Trotsky, Zinoviev, and Kamenev from the party, but later split with Stalin over collectivization. He was executed after a show trial in 1938.

You partially answered this question already, but was there anything in Stalin's early party career that suggested that he would become a tyrant?

As a historian, I take context very seriously. There are aspects of Stalin’s early career that you could see [as likely to develop] in certain ways later, when he has full power. In his earlier career, we find that he’s very much interested in party unity. He even has conflicts with Lenin, who’s much more divisive. Lenin wants to get rid of deviationists, those he doesn’t think are the ones following the correct position. And Stalin is more inclusive, ironically, in wanting to bring people into the fold. Now, in the 1930s, he was also interested in party unity. And there’s a lot of talk about unification of the party and getting rid of oppositionists, deviationists, saboteurs, et cetera. But in the 1930s, with absolute power and with control of the police and the NKVD, he now can put them on trial or simply arrest them, exile them, or have them executed.

What was Stalin's role during the 1917 revolution?

At the beginning of 1917, Stalin was in a rather disadvantaged position. He was in exile in the Krasnoyarsk area, far from the center of power. And then suddenly the revolution broke out in February 1917, and he quickly returned to St. Petersburg, Petrograd at the time. And there he immediately became one of the major leaders — Lenin was not yet in Russia, he was in Switzerland — of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Party. And interestingly enough, Stalin was relatively moderate when he first returned to Petrograd, and even supported the provisional government that had taken power after the overthrow of the Tsar Nicholas II. Lenin was appalled by this moderation. And Lenin returned in April 1917 to Petrograd and he immediately castigated his followers about it. Stalin very quickly made a shift toward Lenin and became one of Lenin's most vocal and dedicated followers at that point.

When Lenin had to flee from Petrograd after the so-called July Days and go into hiding in Finland, Stalin emerged as one of the major figures of Bolshevism. Trotsky was in jail, Zinoviev was with Lenin in exile, and Kamenev was in jail for a while. By October [1917], the Bolsheviks came to power, and Lenin made Stalin the Commissar of Nationalities.

Moving on to 1918 and the beginning of the Civil War: what was Stalin's role during this time?

During the Civil War, Stalin is everywhere at once. He is at the front and in Tsaritsyn. He is competing with Trotsky, who is the head of the expanding Red Army that will ultimately win the Civil War. He’s Commissar of Nationalities, though he’s not paying much attention at the time to that particular office. And he’s not only fighting at the front occasionally, but he’s also involved in the formation of the whole concept of a new state of the Soviet Union. And he’s very close to Lenin in that period in trying to decide how to build this new state.

Basically, Stalin and Lenin are the architects of what can be called Soviet nationality policy. Originally, Marxists, of course, are generally opposed to nationalism. They recognize that at a certain stage of history, the bourgeois capitalist stage, there is also a political formation — the nation state. And they recognize this as part of the unfolding of history. But Marxists in general believe that class formations and class struggle ought to be much stronger than unified national struggles.

And yet Leninism is a very pragmatic ideology. The Bolsheviks, and Lenin and Stalin in particular, recognize that nationalism is developing during World War I. As the Russian Empire fell apart, different nationalities set up their own autonomies or even states. And so in order to deal with this real problem of disintegration, Lenin and Stalin developed a nationality policy that recognized the need for a new federated state. And here the dispute between Lenin and Stalin emerged. Lenin was willing to give more self-rule, more autonomy to the other republics. And Stalin wanted a far more centralized state. He preferred to have those other republics brought into the RSFSR [the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic], and Lenin proposed a larger framework called the USSR. And ultimately Lenin’s view would prevail.

One of the most important things that happens during the Civil War is that Stalin becomes general secretary of the party. This is a minor office, it’s considered a kind of administrative office. But this office of general secretary, in fact, becomes [Stalin’s] instrument to secure power within the party. And Stalin proves to be a great organizer, a great bureaucrat, and begins to build up cadre of supporters within the party. This office gives him appointment powers — he can send members of the party here and there. And it becomes a center of power that Lenin also will recognize later. And Lenin will even try to remove Stalin from that office, but it’s too late in his life. Lenin is ill by 1923-24 and is unable to carry out that assignment.

Was Stalin's rise to power, during the first couple of years of the 1920s, a series of coincidences? Or was it inevitable that a person like him would become a leader of this new relatively young state?

I don't believe that in history there is inevitability. There are possibilities, there are opportunities, and there are potentialities, but not inevitabilities. Stalin was one of many major [political] figures at the end of Lenin's life in 1923 and 1924. The last year of Lenin's life and the first year after his death [saw] the formation of a triumvirate of three people — Stalin, Zinoviev, and Kamenev — who used their unique position to marginalize Trotsky. [Trotsky] was a huge figure, a charismatic orator, a person of great power and influence, but basically a danger to this group of close Leninist comrades.

I'll explain how Stalin ultimately emerged as the major leader, but it's not inevitable. And at first it seemed quite improbable. First of all, Lenin had been a wartime leader during the Civil War, and he could be quite ruthless. Lenin believed that politics is a kind of warfare — not liberal democratic parliamentary politics, compromise, negotiation, give and take. Bolshevik politics was warfare. It destroyed the enemy. And Lenin was good at that, and won in 1917, and won again in the Civil War. But by March 1921, Lenin came to a new conclusion: “We're going to hold on to power. But we Bolsheviks live in a sea of peasants, and if the peasants unify and rise up, we're finished. Therefore, we need a new policy.” And it was called the New Economic Policy, NEP.

In some ways, NEP is what you can call an armistice. It is an attempt to reconcile this regime of urban intellectuals and revolutionaries, based on a small and dissolving working class in the cities, with the great mass of the population of the country. 80 percent of Russia was peasants, living in villages. This was the worst place you can imagine building socialism of a Marxist type, which is supposed to be built on developed capitalism and self-rule of the proletariat. So [NEP] is going to do something completely unexpected in normal Marxist theory. [It gave] the peasants the right to control their own economy, their agriculture, the major economic resource of the country. That compromise would last until 1928. Stalin supported this. And not only that, but [he] believed that this was a gradualist approach, which was basically state capitalism [moving] toward an eventual transition to socialism. He believed that you could build socialism in the Soviet Union, socialism in one country, without necessarily waiting for an international proletarian revolution abroad. So Stalin again was a moderate force, against the left and the left opposition, which was led usually by Trotsky, who wanted a more internationalist policy and more rapid industrialization.

Why didn’t Stalin immediately attempt to build a totalitarian state when he came to power in the second half of the 1920s?

As I mentioned, Stalin was very pragmatic. NEP was working right up to around 1927 or 1928. The country was restoring the economy after the war, developing slowly. The people were getting wealthier. But then, in 1928, NEP began to fail. Industry was growing too slowly [for the state to be able] to give goods to the peasants in exchange for the grain. So the peasants, being rational producers, withheld the grain from the state or sold it to private traders. And Stalin, suddenly moving quite radically to the left, decided, “We’re going to go out and seize the grain from the peasants.” And he eventually pushed for collectivization of agriculture [as a way] to bring grain from the countryside into the cities, and into the army, and to sell abroad.

Was that move really pragmatic, given that it caused massive starvation during the first years of the 1930s?

Collectivization, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, were part of an effort [by] Stalin and his closest supporters to break the back of peasant resistance. And in many ways, collectivization was a war against the peasants — a war of the state, the police, the cities, the workers, and the party against the majority of the population. Collectivization, which would be a disaster, which would reduce agricultural output, which would reduce the productivity of the peasantry in the villages, which would be a fundamental flaw in the Soviet system from the 1930s [through to] the collapse of the Soviet Union, this policy was not only economic — it was political.

Did Stalin ever take seriously the idea of radical world revolution espoused by people like Trotsky?

Stalin was the least internationalist of the Bolsheviks. That corresponds to my reading of Stalin as what we call an étatist, a statist. He’s most interested in preserving the power of the Soviet Union, the existence of the Soviet state, and would use any means needed to achieve that. And international revolution becomes less and less possible, because after 1920, there’s a very important stabilization of Western capitalism and liberalism and these democratic regimes in Europe and the United States that preclude the possibility of international revolution. Lenin’s Comintern, [which was] formed in 1919 and disbanded by Stalin in 1943, never once in all those years ever succeeded in making a revolution anywhere.

Let's turn to famine and the Holodomor in Ukraine. What was the main cause of the Holodomor? Why did the Ukrainian SSR suffer most drastically from this famine?

There are two interpretations of the Holodomor and the famine in Ukraine. One you find among Ukrainian scholars, [as well as] other scholars in the West: the Holodomor was a deliberate attempt by Stalin to destroy Ukraine and Ukrainians. [However], scholars like myself don't see [the Holodomor] as a genocide. I do not argue that it was an ethnocide that is directed specifically against Ukrainians as Ukrainians, but it was a misconceived, brutal policy that was part of the collectivization effort. Stalin and the regime didn't want Ukrainians to die and to cease producing grain. What they wanted was [for] them to produce grain, [so that the state] could take the grain. But what the regime did was take too much grain, including seed grain. And so poor harvests, combined with disastrous policies and brutal neglect, combined to create this death famine or Holodomor. It was incompetence and brutality. You could argue it was a kind of imperial policy, like many of Stalin's policies. The imperial center simply disregarded its peripheries and used the most vicious means. Note, however, that the famine also occurred in the North Caucasus, where there were lots of Ukrainians, in the Volga region, which was Russian, and in Kazakhstan, where the forced sedentarization of nomadic Kazakhs produced more deaths per capita than even in Ukraine. So this is a colossal period of failure, of incompetence, of brutality, that is very much consistent with Stalin's own imperial policies.

Was the Holodomor Stalin’s fault?

I would blame it on Stalin. Famine is a failure of state policy. It means the regime has not taken the necessary measures to prevent massive starvation. Not that there weren't natural causes for reduced productivity and so forth. But the chaos of collectivization itself, and the brutal policies of extracting the grain and taking it from Ukrainians and other peasants, also contributed.

What do we know about Stalin's personal attitude towards Ukraine?

I think that from a lot of little bits of evidence here and there, one can say that he looked down on Ukrainians. He himself was Georgian, but he so closely identified with Russia that in many ways he considered himself a kind of supranational Russian. And as a leader of the Soviet state, and with his Russophilic view of himself, he looked down on Ukraine. If there’s any attitude that I’ve met in my own personal experience of living in the Soviet Union and traveling through Russia, it is an extraordinary condescension of ordinary Russians toward Ukrainians. “Oh, Ukrainian culture? Oh, that’s an oxymoron, that doesn’t exist. What are you talking about? You’re part of Great Russia.” And you see this in Putin’s own reading: “Oh, we’re one people, right? We’re made up of Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians.” This is an imperial trope. This is an imperial way of understanding.

Can we call this kind of policy towards Ukraine and other national republics during the 1930s imperialist?

The Soviet Union is a kind of empire. It's a pseudo-federalist multinational state, but it has serious imperial features. All sovereignty in the Soviet Union belongs to Moscow. The republics have certain national rights, but not sovereignty, not supreme dominance of their own state. And that lasted right up until the Gorbachev period. At the same time, there was a Sovietization policy — the creation not only of national cultures, but also at the same time, and in some ways in contradiction to this, the creation of a Soviet culture, which was heavily Russian. So an Armenian or a Ukrainian or a Kazakh was supposed to [identify] with their own people, but at the same time, [have] a kind of patriotism for the Soviet Union. You could see how those things might be contradictory. In fact, they often work together. If you think of World War II, people fought and died for the Soviet Union. They would say, “For the homeland and for Stalin,” and they would die with that claim. So we can't underestimate the success of this Soviet project in creating dual, combined identities.

To what extent was Stalin's USSR during the 30s a reincarnation of the Russian Empire?

There are historians who argue that Stalin was a new tsar, that this was a new autocracy, that collectivization was a second serfdom, all of these kinds of things. I don’t find [such analogies] so useful. I think what Stalin was doing was creating a new kind of state. It was an imperial state, but it was quite different. It was now dominated by the Communist Party, by the nomenklatura. Some would say, “Okay, that’s a new nobility, right?” But these are not inherited positions. I would argue that [the USSR] is an imperial state, an internal empire, with very peculiar [elements], like the development of these national units. At the same time, let’s not forget that Stalin also created an external empire. After World War II, he took over Eastern Europe and had a whole slew of satellite states, which he didn’t incorporate into the Soviet Union.

What is the attitude toward Stalin in contemporary Georgia and the other countries of the South Caucasus?

If you go to Armenia or Azerbaijan, you will not find many people who love Stalin. They only know the horrors that Stalin brought on those countries, destroying their local intelligentsias, moving people to Siberia or Kazakhstan. But in Georgia, Stalin is a national hero. Stalin was the most famous and powerful Georgian in history. By the time Stalin died, he was probably the most powerful man in the world. So you can understand why Georgians might have a nostalgia for that achievement. At the same time, Georgia suffered. Its intelligentsia was also brutalized and murdered. There’s a debate in Georgia between those who don’t know much about what Stalin did to Georgia, and therefore continue to revere him, and those who are better informed.

What was Stalin's own relationship with his Georgian identity?

There's a private Stalin and a public Stalin, and the private Stalin did remain, in many ways, Georgian. He would have a Georgian chef, for instance. He trusted Georgians in certain ways, looked toward Georgians to help and protect him. His public persona is Soviet, a Russified Soviet, even though he always had a heavy Georgian accent. And he identified primarily with Russia as a great state and the Soviet Union as the embodiment of a great Russian state.

How do you rate Stalin as a political thinker?

Whatever original ideas Stalin had, they were Lenin's ideas or Marxist ideas — things he read and believed, and then interpreted in his own way. He took Marxism and Leninism as his framework, as his sociology, as his understanding of history. He was an intellectual. He read carefully, he annotated books, but always within this general framework. But then he interpreted that framework and narrowed that framework so that the more humanistic or dialectical or aspects of Marxism were eliminated.

What were the main reasons for starting the Great Terror, from Stalin's point of view?

You’re asking the most difficult question [about] one of the great mysteries of Soviet history. This is something that we don’t have a good answer to. And I’ve tried, myself, to think carefully, because the Great Purges are an irrational act. Why would a state on the eve of a war, that they knew was coming, destroy its intellectuals and its army commanders? Why would it weaken itself? Why would a great state make itself stupid when it most needed to be intelligent?

To answer your question — there were two things. One, Stalin's own belief that he himself represented the best guarantee for creating the kind of socialist state that he envisioned. It's not a state that I would call socialist, but that's what he envisioned as socialism. And two, he still was pushing, as he had [for his whole] career, for party unity. But now party unity would be achieved not by persuasion, not by agreement, not by discussion, as was true in the Leninist times, but by brutal force and by mass murder. And so he carried out this purge, weakened the Soviet Union, and left it a ruined landscape on the eve of the war.

So maybe Stalin wasn’t that pragmatic after all?

Pragmatic only in the sense that if his goal was to create a kind of brutalized unity, a kind of unity where there’s no more dissent, then it was pragmatic. But its effects were exactly the opposite. It actually weakened the Soviet Union seriously, and made the victory in the war far more difficult.

Why was it necessary for Stalin to proceed to large scale terror? Why couldn’t he just have conducted a purge within party ranks?

There’s a kind of multiplier effect in the great purges. So you start by arresting a few people, and [the authorities] tortured people, people gave false confessions, and then more people were arrested. And more and more, the NKVD was fabricating cases, making up conspiracies. And this fed into this atmosphere of suspicion, in which everyone was supposed to denounce everyone else. This steamroller of accusations and denunciations simply spiraled until finally, Stalin simply said, “Stop it.”

What were the results of the great purge politically and socially?

Politically, if you eliminate a whole generation of old Bolsheviks and managers and intellectuals, you need to have them replaced. And so what you have is new people coming up. A new generation came up, very young people, like Andrey Gromyko or Leonid Brezhnev. They came to power [when they were] in their 30s or younger, in the late Stalin period, to replace all of those people who had been killed. The Soviet leadership right up to Gorbachev were people who had been pushed up in this Stalinist period.

A second great social change was the complete dampening of initiative, of taking responsibility for your own actions, of trying to create something new. People became obedient. [But] when [World War II] came, suddenly one can see that ordinary Soviet citizens became initiators. In other words, what the West called a totalitarian regime was never fully achieved. That doesn’t mean that Stalin did not have totalitarian aims to control as much of the system and the society, and the knowledge of that society, as possible. But it never was ever achieved in full.

We’re skipping the whole decade of the 1940s because that could be an entire interview of its own. Let's talk about Stalin’s death. How did he die?

Very painfully. On the night of March 4th-5th, 1953, he and his friends had been carousing and having drinks in his dacha at Kuntsevo. And he seemed in a very good mood. They all left early in the morning, and he went into his study and lay down on the couch. And at some point during that night, he had a stroke, a massive stroke. He lingered through the night. The next morning, he didn't emerge from his study. [His] guards were fearful. They called members of the Presidium [of the Supreme Soviet], and they came. And Beria apparently said, “He's asleep, don't bother him.” The people who arrived did not call a doctor right away. So Stalin was dying at that time. And eventually he did, in fact, expire. That's the simple story. Even before Stalin was completely dead, the most powerful figures in the Communist Party were sitting together and organizing the post-Stalin regime.

What was the reaction of ordinary Soviet citizens?

Ordinary Soviet citizens were shocked — a kind of god had been removed. There were massive movements of people through the streets of Moscow that led to crushes of people and deaths as they tried to see Stalin’s body. It was a disorienting event because the whole system depended on Stalin.

Why were ordinary citizens so distraught? Had people simply forgotten about the Great Terror?

Stalin stayed in power not by terror alone. The terror was important, it reinforced his power, and it kept people in place. But you have to remember, along with that, [there] was a huge campaign of propaganda, of celebration, of beautiful posters trying to persuade people that this was the march forward into a beautiful future. People were much more affected by that propaganda campaign than one might think. And don't forget this [aspect]: we didn't talk particularly about the Second World War, but the Second World War was the great triumph of Stalin. He identified with the victory, which of course was carried out by ordinary Soviet citizens, 27 million of whom died during the war and in the struggle against fascism. Basically, the Soviets fought three-quarters of the Nazi forces and took Berlin. The Soviets ended the Holocaust by liberating Auschwitz and the camps in Poland. People don't give any credit to this at all.

Why did it take several years after Stalin’s death for Soviet leaders to start enacting real, systemic change?

One of the most interesting things when you look at the death of Stalin and the period right after [his death] is how frightened and confused the top Soviet leaders were. They didn’t know what was going to happen. It took some time for the consolidation of this new regime under Nikita Khrushchev. And by 1956, Khrushchev made an extraordinary, bold decision to launch an attack against Stalinism and the legacy of Stalin. And it almost destroyed the regime. It certainly made the regime less strong in the short run. There was dissent within the Soviet Union. There were revolts in Eastern Europe, most importantly in Hungary, but also in Poland. So the Khrushchev Congress took time before they could come to the idea that they ought to launch this attack on the worst excesses of Stalinism and try to return to what they imagined was the original Leninist project. They never went back to the original Leninist project, which, as we’ve described, was NEP. That would not occur until Gorbachev, who would try to get back to Leninism and something like a state capitalist regime, though it was late, he was weak, he didn’t enforce his policies well, he divided the Communist Party, and the regime collapsed.

You know, the way I look at Soviet history, I don't see that the Soviet regime descended from reading Karl Marx. I see the Soviet regime as a series of improvisations of trying to get the regime correct. We have war communism. We have NEP. We have Stalinism. We have the reforms of Khrushchev. We have the stagnation of Brezhnev. And finally, we have the radical revolutionary reforms of Gorbachev that brought the regime down. So they never got it right. And they never built something that I would call socialism. But they did modernize a country, from 80 percent peasants to 80 percent literate urban dwellers. And by the way, the Soviet population by 1991 didn't need the empire anymore. The empire had done its job.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's a soviet summer: my book collection about the soviet union and/or the dominant theme is the soviet union (with a bit of russian literature)

i spent the entire vacation as a little cocoon in pink and red and teared through these bad boys (except 5 books..... im saving those. i cannot let this hyperfixation die)

books include:

(stack one)

the communist manifesto by karl marx and friedrich engels

a nervous breakdown by anton chekhov

how much land does a man need? by leo tolstoy

the meek one by fyodor dostoyevsky

stalin: the history of a dictator by h. montgomery hyde

barbarossa and the bloodiest war in history by stewart binns

the future is history: how totalitarianism reclaimed russia by masha gessen

trotsky by robert service

reaction & revolutions: russia 1881-1924 by michael lynch

(stack two)

a backpack, a bear, and eight crates of vodka by lev golinkin

makers of the twentieth century: nikita khrushchev by martin mccauley

a guide to st. petersburg by rough guides

gorbachev by thos g. butson

down the volga by marq de villiers

forced displacement and human security in the former soviet union by helton & voronina

siege & survival by elena skrjabina

stalin's daughter by rosemary sullivan

#but just because i am interested about the ussr doesn't mean i stand with russia. i stand with ukraine#viv's post#viv's bookshelf

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

También nos llamaron locos cuando...

La Ojrana (policía secreta del Imperio ruso) fomentó el antisemitismo presentando Los protocolos de los sabios de Sion como texto auténtico.25

El asesinato de Lev Trotski en México, ejecutado por Ramón Mercader, un agente español de la NKVD soviética.

ODESSA (del alemán Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen, Organización de Antiguos Miembros de la SS) fue una presunta red de colaboración secreta desarrollada por grupos nazis para ayudar a escapar a miembros de la SS desde Alemania a otros países donde estuviesen a salvo, particularmente a Latinoamérica. La organización fue utilizada por el novelista Frederick Forsyth en su obra de 1972 The Odessa File, basada en hechos reales, lo que le dio una gran repercusión mediática. Por otro lado, el mayor investigador, perseguidor y encargado de informar sobre la existencia y misión de esta organización fue Simon Wiesenthal, un judío austríaco superviviente al Holocausto, quien se dedicó a localizar exnazis para llevarlos a juicio. La historiadora Gitta Sereny escribió en su libro Into That Darkness (1974), basado en entrevistas con el excomandante del campo de exterminio de Treblinka, Franz Stangl, que ODESSA nunca existió. Escribió: «Los fiscales en la Autoridad Central de Ludwigsburg para la investigación de crímenes nazis, que sabían precisamente cómo han sido financiada en la postguerra las vidas de ciertos individuos actualmente en Sudamérica, han buscado entre miles de documentos desde el principio hasta el final, pero afirman que son totalmente incapaces de autentificar la existencia de ‘Odessa’. No es que esto importe: ciertamente existieron varios tipos de organizaciones de ayuda a los nazis después de la guerra — habría sido sorprendente que no las hubiese habido».

El proyecto MK Ultra —a veces también conocido como programa de control mental de la CIA— fue el nombre en clave dado a un programa secreto e ilegal diseñado y ejecutado por la Agencia Central de Inteligencia (CIA) de los Estados Unidos para la experimentación en seres humanos. Estos ensayos en humanos estaban destinados a identificar y desarrollar nuevas sustancias y procedimientos para utilizarlos en interrogatorios y torturas, con el fin de debilitar al individuo y forzarlo a confesar a partir de técnicas de control mental. Fue organizado por la División de Inteligencia Científica de la CIA en coordinación con el Cuerpo Químico de la Dirección de Operaciones Especiales del Ejército de Estados Unidos.

La CIA ha estado involucrada en varias operaciones de tráfico de drogas. Algunos de estos informes afirman que la evidencia del Congreso que indica que la CIA trabajó con grupos que se sabía que estaban involucrados en el tráfico de drogas, por lo que estos grupos se les proporcionó información útil y de apoyo material, a cambio de permitir que sus actividades criminales continuaran, y de obstaculizar o impedir su arresto, acusación y encarcelamiento por las agencias policiales estadounidenses.

En la década de 1980, el gobierno de los Estados Unidos se vio envuelto en una conspiración para derrocar al gobierno nicaragüense, mediante la financiación, a través de la venta de armas a Irán y de drogas en las calles de los Estados Unidos, de una guerrilla contrarrevolucionaria. Estos hechos, conocidos como “Escándalo Irán-Contra” o “Irangate”, implicaron a varios miembros de la administración de Ronald Reagan, incluido el presidente, y fueron, incluso, judicializados y juzgados, lo que demuestra su veracidad.Informe del Senado estadounidense de 1977 sobre la existencia del programa MK Ultra.

La red ECHELON

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aniversario: 100 años de la Revolución Comunista en Rusia… que no es cosa de risa. (II)-

“Nunca toleraremos que me acusen con vergonzosas teorías de conspiración” ( Stalin sobre el asesinato de Trotsky)

Lev Davídovich Bronstein, Trotsky, fue un pensador, político y reconocido revolucionario ruso cuya obra más reconocida fue sobre todo la creación (junto a otros miembros como Lenin, Stalin y Hitler) de la antigua y prestigiosa "Escuela de diseño y vestimenta socialista" del siglo XX, gracias a ellos, el uso de los bigotes adquirió un nuevo enfoque indispensable para llevar a cabo la revolución.

Fue el quinto hijo de una familia de origen judío, lo que posiblemente explicaba el por qué Stalin era el que negociaba con Hitler y firmaba pactos de no agresión con él.

A la muerte de Lenin el puesto de líder quedó en manos de un bigotudo aún de peor carácter que su predecesor, el puño de hierro, Iósif Stalin, que poco tardó en dar su primera orden: ¡al tal Trotski de momento... me lo exilian!.

Trotski, como él mismo dijo siempre iba a "estar en una permanente revolución", así que Stalin al saber que iba a tener un peligroso competidor en lo que respecta a el monopolio de los bigotes soviéticos, hizo hasta lo imposible para asesinarlo.

Para ello reunió a dos socialistas catalanes de muy mal carácter debido a que en esa época su equipo aún no ganaba una Copa de Europa, mientras el rival, el Madrit, sí. Uno de ellos de apellido Mercader lo mandó (de forma permanente) al otro mundo.

Hay varias formas de ofender y sacar de quicio a los troskos (seguidores de Trosky y su IV Internacional) y todas son bastante entretenidas. La preferida del viejo Profesor Javaloyes es asumir que todos los troskos son posadistas* y hacer burla con eso.

El posadismo es una corriente argentina del trotskismo que mantiene dentro de sus postulados que existen alienígenas socialistas que van a venir a rescatarnos con su revolución intergaláctica.

Pero esa queridos es… otra historia.

“Hazme cosquillas con tu bigote León, Ahora te toca a ti hacérmelas a mí con el tuyo Frida” (hermosa conversación de amantes entre Trotsky y Frida Khalo)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Events on March 23

The Politburo Five

1919 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party re-establishes a five-member Politburo which becomes the center of political power in the Soviet Union. Original members Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Stalin, Lev Kamenev and Nikolai Krestinsky.

Source

View On WordPress

0 notes