#la na cailleach

Text

...and why the Spring Equinox ties up with the modern tax year.

0 notes

Text

CÓNOCHT AN EARRAIGH / SPRING EQUINOX

While it's unlikely that the Equinoxes were observed as such in the ancient Gaelic nations, we find from Scotland an interesting collection of modern observations centered around the coming of spring--and featuring a magical figure who may have roots in much older practices.

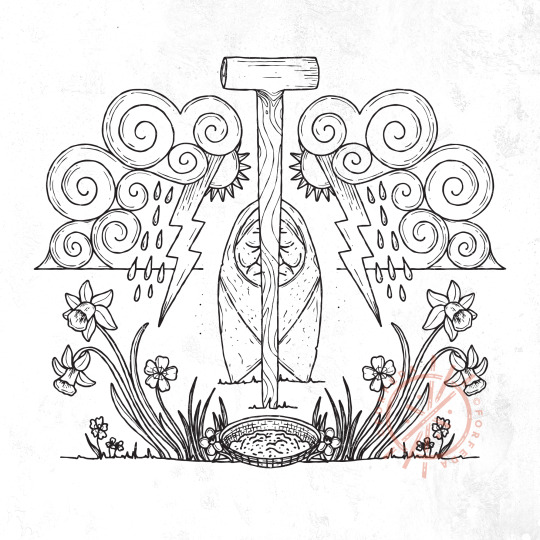

Held on March 25th, Lá na Cailleach, or Cailleach's Day, signified the time that the Cailleach, the Hag of Winter, was said to make her final struggle against the warmth and growth of spring, throwing down her staff and whirling up harsh winds and wild storms, before her eventual defeat. As March 25th was originally the date for the new year in Scotland, as well as the fixed date of the vernal equinox, Lá na Cailleach served as a turning point for the seasons and signaled the onset of changes in the weather.

This design features the Cailleach's magical staff, and the Cailleach herself, now turned to stone until next winter. Also incorporated are storm clouds, spring flowers, and a basket of seeds, ready for the sowing season.

#celtic#celticart#mythology#irish mythology#celtic mythology#folklore#equinox#cónocht#spring#wheeloftheyear#vernal equinox#spring equinox#la na cailleach#la na caillich#cailleach#gaelpol#wheel of the year#pagan#pagan art#forfedaproject

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pagan Deities

This part is separated into “deity categories” where I will only be listing the deities in each category because they may overlap and I unfortunately don’t have the time to go through every single deity, if any interest you by name feel free to look them up, but the categories should be helpful if you want to find a deity in a specific category, there are 15 deity categories from the website I used and I want to make sure my sources are good, so any feedback with corrections or additions you think I should add to it are greatly appreciated, especially since not every culture is represented in every category :)

Deities of Love and Marriage

Aphrodite (Greek)

Cupid (Roman)

Eros (Greek)

Frigga (Norse)

Hathor (Egyptian)

Hera (Greek)

Juno (Roman)

Parvati (Hindu)

Venus (Roman)

Vesta (Roman)

Deities of Healing

Asclepius (Greek)

Airmed (Celtic)

Aja (Yoruba)

Apollo (Greek)

Artemis (Greek)

Babalu Aye (Yoruba)

Bona Dea (Roman)

Brighid (Celtic)

Eir (Norse)

Febris (Roman)

Heka (Egyptian)

Hygieia (Greek)

Isis (Egyptian)

Maponus (Celtic)

Panacaea (Greek)

Sirona (Celtic)

Vejovis (Roman)

Lunar Deities

Alignak (Inuit)

Artemis (Greek)

Cerridwen (Celtic)

Chang’e (Chinese)

Coyolxauhqui (Aztec)

Diana (Roman)

Hecate (Greek)

Selene (Greek)

Sina (Polynesia)

Thoth (Egyptian)

Deities of Death and the Underworld

Anubis (Egyptian)

Demeter (Greek)

Freya (Norse)

Hades (Greek)

Hecate (Greek)

Hel (Norse)

Meng Po (Chinese)

Morrighan (Celtic)

Osiris (Egyptian)

Whiro (Maori)

Yama (Hindu)

Deities of the Winter Solstice

Alcyone (Greek)

Ameratasu (Japan)

Baldur (Norse)

Bona Dea (Roman)

Cailleach Bheur (Celtic)

Demeter (Greek)

Dionysus (Greek)

Frau Holle (Norse)

Frigga (Norse)

Hodr (Norse)

Holly King (British/Celtic)

Horus (Egyptian)

La Befana (Italian)

Lord of Misrule (British)

Mithras (Roman)

Odin (Norse)

Saturn (Roman)

Spider Woman (Hopi)

Deities of Imbolc

Aradia (Italian)

Aenghus Og (Celtic)

Aphrodite (Greek)

Bast (Egyptian)

Ceres (Roman)

Cerridwen (Celtic)

Eros (Greek)

Faunus (Roman)

Gaia (Greek)

Hestia (Greek)

Pan (Greek)

Venus (Roman)

Vesta (Roman)

Deities of Spring

Asase Yaa (Ashanti)

Cybele (Roman)

Eostre (Western Germanic)

Freya (Norse)

Osiris (Egyptian)

Saraswati (Hindu)

Fertility Deities

Artemis (Greek)

Bes (Egyptian)

Bacchus (Roman)

Cernunnos (Celtic)

Flora (Roman)

Hera (Greek)

Kokopelli (Hopi)

Mbaba Mwana Waresa (Zulu)

Pan (Greek)

Priapus (Greek)

Sheela-na-Gig (Celtic)

Xochiquetzal (Aztec)

Deities of the Summer Solstice

Amaterasu (Shinto)

Aten (Egyptian)

Apollo (Greek)

Hestia (Greek)

Horus (Egyptian)

Huitzilopochtli (Aztec)

Juno (Roman)

Lugh (Celtic)

Sulis Minerva (Celtic, Roman)

Sunna or Sol (Germanic)

Deities of the Fields

Adonis (Assyrian)

Attis (Phrygean)

Ceres (Roman)

Dagon (Semitic)

Demeter (Greek)

Lugh (Celtic)

Mercury (Roman)

Osiris (Egyptian)

Parvati (Hindu)

Pomona (Roman)

Tammuz (Sumerian)

Deities of the Hunt

Artemis (Greek)

Cernunnos (Celtic)

Diana (Roman)

Herne (British, Regional)

Mixcoatl (Aztec)

Odin (Norse)

Ogun (Yoruba)

Orion (Roman)

Pakhet (Egyptian)

Warrior Deities

Ares (Greek)

Athena (Greek)

Bast (Egyptian)

Huitzilopochtli (Aztec)

Mars (Roman)

The Morrighan (Celtic)

Thor (Norse)

Tyr (Norse)

Warrior Pagans

Mother Goddesses

Asasa Ya (Ashanti)

Bast (Egyptian)

Bona Dea (Roman)

Brighid (Celtic)

Cybele (Roman)

Demeter (Greek)

Freya (Norse)

Frigga (Norse)

Gaia (Greek)

Isis (Egyptian)

Juno (Roman)

Mary (Christian, but not referred to as a goddess according to some Christian beliefs)

Yemaya (West African/ Yoruban)

Source: https://www.learnreligions.com/types-of-pagan-deities-2561986 the links of each category show the deities provided

#witch#witchcraft#intro to paganism#intro to witchcraft#wicca#baby witch#research on witchcraft#deities#pagan#pagan deities#deity categories

611 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religious Medievalism: “Stregheria”, Wicca and History - part 1

[TN: This article will break the Introduction to Stregoneria series for a second, but I believe it’s important to set things into perspective about both Witchcraft and this blog.

My goal is to put out content, translated or redacted by me, in order to give people the correct historical information. I see a lot people on TikTok messing with things they don’t know, appropriating and distorting practices and cultures and profiting off of it.

The only focus of this blog is the practice and the history behind it, I don’t want to “put people down”, I want to make the information available so you won’t hurt yourselves.

Also, I do not support fa***sm, na**sm or any other movement/ideology that oppresses and discriminates people. I’m specifiying this because I’ve received an anonymous ask about it and it kind of hurt just reading it. I hope this will clarify things and make whoever asked me that more confortable with my blog and my content. I’m a history nerd Strega, nothing more.

This article will be a translation, synthesis and re-elaboration of the following articles

https://tradizioneitaliana.wordpress.com/2020/11/12/medievalismo-religioso-stregheria-wicca-e-storia/

https://medievaleggiando.it/la-legittimazione-storica-della-wicca-margaret-murray-e-la-manipolazione-delle-fonti/

https://medievaleggiando.it/il-vangelo-delle-streghe-e-linizio-della-wicca-il-fascino-di-un-falso-storico/

The first being a rectification of the two that follow.

This article will be divided in two parts because it’s way too long to read and to translate, i’m drained af]

THE DEBUNKING OF MURRAY

Margaret Alice Murray (1863-1963) was a British Anthropologist and Egyptologist, well known in the academic environment for her contributions in the studies of folklore. Even if she was very criticized and her reputation as an historian was poor, her work became popular bestsellers from 1940 onward.

The most well-known and controversial one is “The Witch-Cult in the Western Europe” published in 1921.

In this book, Murray alleges that there was some sort of secret model of pagan resistance to Christianity spreaded all across Europe, and that the witches’ hunt and the proof presented to the trials were an attempt to eliminate a rival cult.

This book was clearly influenced by “Satanism and Witchcraft” by Jules Michelet, that alleged that Medieval Witchcraft was an act of popular rebellion against the oppression of feudalism and the Roman Catholic church, that took the form of a secret religion inspired by paganism and organized mainly by women.

To support her narrative, Murray chooses to analyze some of the trials that took place during the great hunt and employs 15 primary sources, mostly British or Scottish (not paneuropean, or sources from the european continent), that describe famous trials.

Murray’s analysis of the Somerset Trials in 1664 offer a good example of her work ethics; quoting the testimony of Elizabeth Styles:

“At their meeting they have usually Wine or good Beer, Cakes, Meat or the like. They eat and drink really when they meet in their bodies, dance also and have Musick. The Man in black sits at the higher end, and Anne Bishop usually next him. He useth some words before meat, and none after, his voice is audible, but very low.”

Murray conveniently seems to “forget” to quote the immediately preceding phrase:

”That at every meeting before the Spirit vanisheth away, he appoints the next meeting place and time, and at his departure there is a foul smell.”

Other details offered by Styles are omitted, like when she alleges that the Devil presented to her in the shape of a dog or a cat or a fly, that the Devil offered her followers an oinment to use on their heads and wrists that made it possible to move them from a place to another. Or that sometimes the reunion involved only the spirits of the witches, while their bodies stayed at home.

Murray was fully aware of the fantasy element in the testimonies she included in her books, but she was able, by deliberately manipulating historical sources, to make people believe the fake narrative that a Medieval religion of witches with covens, rites and their own beliefs that relentlessy opposed Christianity really existed.

In her “The God of the Witches”, published in 1933 and clearly written for a commercial audience, she further broadened the scope of her claims on the witches’ cult.

In this book, she alleges that until the C17th BCE the there was a religion, older than Christianity, that kept existing in all of Western Europe. Said religion, was focused on the worship of a two-faced horned god, known to the Romans ad Diano; this god presided the witches’ gathering and was mistaken by the Inquisition of the Devil, conclusion that made them associate witchcraft with a satanic cult.

Murray claims the existence of a *specific* non-christian organized cult spread all across Europe that worshipped Diano and relentlessly opposed the Roman Catholic church, but the sources she quotes are late and recount the flattening of the various “pagan” cults to the assimilation with the christian Devil, operated by the Church.

In fact, the Devil that the trials report on, depending on the religion, overlapped with different figures: in British and Scottish traditions the Devil was the result of the demonization of the King of Elphame.

In the Basque country, the Devil substituted Mari. In Northern Italy it overlapped with the Donna del Buon Gioco.

This means that the “Northern Italian Devil” is different from the “British Devil” and the “Basque Devil”.

This “Devil” is a figure that flattens everything and overlapped and substituted so many different figures, depending on the religion and the figure it ended up overlapping with.

Therefore, Murray’s narrative of a paneuropean cult of the Horned God stems from the analysis of late sources and to the false equivalence of the Devil that presided the Ludus (Sabba) in Scotland (where he masks the King of Elphame) and the Devil of other countries (where he masks other entities).

Since the Devil isn’t the same entity in all of Europe, the narrative of a counter-christianity organized paneuropean cult of prehistoric origin falls too. Instead, what we’re dealing with are Medieval, non-christian rielaborations of different remainders of the Religions of the Gentiles that survived in the Christian age and were absorbed in the legend of the Faery Procession/Procession of the Dominae Nocturnae first, and the legend of the Ludus (Sabba) later.

The following quote by Ronald Hutton, English historian who specialises in Early Modern Britain, British folklore, pre-Christian religion and Contemporary Paganism and professor at the University of Bristol, confirms this:

“Over a quarter of a century ago, I adopted the expression “Pagan survivals” to describe elements of ancient Pagan culture that had persisted in later Christian societies. In doing so, I was drawing a distinction between such survivals, of which there seemed to be many, and “surviving Paganism”; that is the continued self-conscious practice of the older religions, of which there seemed to be none. This point was worth making because even in the 1980s, there was a persisting belief, based on outdated academic texts, that Paganism had survived as a living force among the common people in much of medieval Europe: it was widespread in other scholarly disciplines than history, let alone among the general public. My formula and approach was adopted by other authors in the 1990s. During that decade, however, a reaction set in against it among historians who preferred to stress the comprehensive Christianization of medieval European societies and to relegate elements that had hither to been identifed as of pagan origin to categories of religiously neutral folklore or of lay Christianity. Some emphasized that the undoubted tendency of some Christians at the time to condemn such beliefs and practices as pagan was a hallmark of a highly atypical, reforming, intolerant and evangelical strain of churchman. Michael’s system of classification, in this volume, may be said to take its place in this, apparently now dominant, set of scholarly attitudes. Revisiting the issue myself, I am inclined to meet it halfway. I am startingto agree that to speak of aspects of medieval culture as “Pagan” might indeed be misleading and inadequate. Moreover, it would be especially inappropriate to characterize fgures such as the lady of the night rides, the fairy queen or the Cailleach as “Pagan survivals” when they seem like medieval or post-medieval creations. However, I have equal diffculty in describing them simply and straightforwardly as “Christian” because of their total lack of reference to any aspect of Christianity, including theology, cosmology, scripture and liturgy; all of them would indeed fit far more comfortably into a Pagan world-picture. […] It may be that the old polarized labels are becoming inadequate to describe a medieval and early modern religious and quasi-religious world that is coming to seem even more complex, exciting and interesting than it had seemed to be before.”

Also Michael Ostling, religious studies scholar focusing on the history, historiography, and representation of witches and witchcraft, confirms this in Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits: “Small Gods” at the Margin of Christendom, published in 2018.

“Christians encompass aspects of their prior paganism both by inversion and revaluation. But where traditional spirits remain salient to a Christianized culture in encompassed or inverted form, their ongoing reality ought not to be counted by scholars as a pagan survival—though it is likely to be so construed by Christians themselves. Such “surviving” spirits are not just marginalized or diabolized pagan remnants, they are continually re-performed, recreated through Christian ritual and Christian discourse. We find such re-creation of the small gods throughout Christian history, and throughout this volume: when the Urapmin drive out the motobil by the power of the Holy Spirit, when Andean people frame their propitiation of the yawlu with devotion to the Christian God, when Mami Water appears primarily as a trope of Pentecostal deliverance ministry, when thirteenth-century Frenchwomen see, in an unoffcial Christian saint, their best hope of negotiating the return of their stolen babies from the follets, when the brownie and Robin Goodfellow appear in prayers of protection against them, in assertions of their diabolical status, or in tolerant mention of superstitious old wives who stillbelieve in such “harmless devils,” when cunningwomen insist that they only use “good devils” or that the fairies who facilitate their divination have no fear of the cross, this is because the beings involved have succeeded in taking up a niche within Christian discourse. The “good people” have not departed, have not been driven out by the sound of church-bells or the smell of gasoline. There are no pagan survivals: small gods are Christian creations with which to think the limits of Christianity.”

In essence, Murray’s version of events that describes Paganism as an anti-church, anti-society isn’t backed by any historical evidence.

Sources:

https://tradizioneitaliana.wordpress.com/2020/11/12/medievalismo-religioso-stregheria-wicca-e-storia/

https://medievaleggiando.it/la-legittimazione-storica-della-wicca-margaret-murray-e-la-manipolazione-delle-fonti/

https://medievaleggiando.it/il-vangelo-delle-streghe-e-linizio-della-wicca-il-fascino-di-un-falso-storico/

Michael Ostling. Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits: ‘Small Gods’ at the Margins of Christendom. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

#witchcraft#wicca#reconstructionist traditional witchcraft#traditional witchcraft#stregoneria#stregheria#witch#medieval witchcraft#spirits#familiar#familiars#pantheon#italian witchcraft#sabba#sabbat#strega#streghe

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

.᭝꒰᭄ꦿꪡᧉᥣᥴ᥆꧑ꫀ୭ ̥◌

- - - -.︶ ̥◌ :: ̥◌ ︶.- - - -

··· ─ ───────── ─ ···

⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝⏝

◦

○

◯

︵͡⏜͡︵͡⏜͡︵͡⏜͡︵͡͡⏜͡⏜͡︵͡⏜͡︵͡⏜͡︵͡͡⏜͡︵

Cailleach é a Anciã ancestral da Escócia, também conhecida como a Carline ou Mag-Moullach, representado o aspecto de velha da Deusa no ciclo anual.

Esta ligada às trevas e ao frio do inverno e assumiu a direção no ciclo das estações em Samhaim.

Ela porta um bastão negro do inverno e castigava a terra com frias forças contrativas que ressecavam a vegetação. Com a aproximação do fim do inverno, ela passava o bastão do poder para Brigid, em cujas mãos ele se tornava branco que estimulava a germinação das sementes plantadas na terra negra. As forças expansivas da natureza começavam então a se manifestar. (gancho com Imbolc)

Por vezes, essas duas deusas eram retratadas em batalha pelo controle da natureza: dizia-se até que Cailleach aprisionava Brigid sob as montanhas no inverno. Mas o melhor modo de vê-las é como duas facetas de uma deusa tríplice das estações: a Velha Cailleach do Inverno, a Donzela Brigid da Primavera e a Deusa-Mãe do viço do Verão e da frutificação do Outono. O nome do último membro dessa trindade não foi preservado na lenda folclórica com o mesmo cuidado. Talvez porque ela representava uma faceta demasiado pagã da Deusa, vinculada demais com a fecundidade e com as forças sexuais da vida.

Para os escoceses, Cailleach era aquela que cujo bastão negro, separava as montanhas, mudava a paisagem, previa o crescimento das ervas e comandava o tempo. Ficou conhecida também, como "Mulher de Pedra", porque era vista andando e carregando uma cesta cheia de pedras. Ocasionalmente deixava cair algumas, formando círculos de pedras. As montanhas também teriam sido criadas por pedras que a Deusa deixou cair da cesta.

Cailleach representava a terra coberta de neve e geada. Era uma Deusa da Transformação e guardiã da semente, que conserva dentro de si a força essencial da vida.

✦ ✧ ✩ ✫ ✬ ✭ ✯ ✭ ✬ ✫ ✩ ✧ ✦

☽О☾ Que os Deuses nos abençoe ☽О☾

♡☆Meus Estudos☆♡

⏝ ི⋮ ྀ⏝ ི⋮ ྀ⏝⏝ ི⋮ ྀ⏝

───────── • ⊰

┊ ┊ ┊

┊ ┊ ┊

┊ ┊ ✤

┊ ✩

✦

╭ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Obrigado por olhar!

Até a próxima

(◡ ω ◡)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sheila Na Gig

For the last few months I have been researching witches, pagan rituals, traditions and Celtic history. I first came across the Sheila na Gig statues when researching women’s rights before and after British rule over Ireland.

In Celtic Ireland women enjoyed legal rights, rights that would been seen as being very progressive even in some of today’s societies. Women kept their own property in marriage and a wife could divorce her husband for fourteen different reasons. British conquest brought to an end Ireland’s independent legal system and removed most of Irish women’s traditional rights. It also brought sexual prudity, which hadn’t previously been part of Irish culture.

In Celtic tradition there are many stories of strong warrior women, equal to men, if not stronger. There is Queen Maeve who led her army to victory, in one battle drowning an army in urine and menstrual blood. The narrative of this story has changed over the years, having been influenced by patriarchal readings of what happened, but compared to the stigma in today’s society around women and menstruation, this story is quite a powerful display of womanhood; menstruation shown as being powerful, a superpower nearly, instead of a weakness or something to be ashamed of. Irish women would fight in every rebellion as equals to men. It is easy to be unaware of this history and these legends in modern Ireland and can easily be hard to imagine when we are currently still fighting for economic and reproductive rights in Ireland.

The policing of female sexuality is not only a problem in Ireland, as control over women’s bodies and sexuality can be seen in most societies around the world. There is no doubt that the female body is political, whether it is being sexualised or de-sexualised, but there is power in realizing that we cannot continue to apologize for existing, for having needs, wants, desires and power. I am obviously particularly interested in the history of women in Ireland, being an Irish women myself, specifically Northern Irish. I was pleasantly surprised by the information I discovered on Irish women and the struggle for a United Ireland, the equality and respect they were granted as they fought alongside men. It is impossible to escape the effect of centuries of religion in Ireland, and with this religion comes the control over women in Ireland. This is why I was particularly interested and surprised when I discovered the figurative carvings of Sheila na Gigs that were carved on churches and castles in Ireland and Great Britain.

My discovery of Sheela na Gig statues is what led me to continue to research the history of women in Ireland, from Celtic legends to the Easter Rising. There is something so striking, so powerful in these unapologetic carvings with their exagerated vulva’s. I was also especially surprised to find that many of the Sheela na Gig carvings appeared to be masturbating, quite a radical depiction of women considering that even today female masturbation is quite a taboo subject and still not widely explored in modern art. There are many different explanations for what the Sheela na Gigs represent and it can be imortant to look at who is giving the explanation, for example, the theory that they are on churches as a warning against lust probably came from religious figures. There are suggestions that the Sheela na Gig represents a pagan goddess, perhaps the goddess cailleach, who was so powerful she could create and shape the hills and valleys. The imagery of a goddess is powerful in itself as she represents an immanent power, authority, control and respect. She is a spiritual figure that seeks to empower women in their own choices and self worth unlike many of the spiritual figures in other religions.

There are claims that the carvings are fertility figures, although many of the Sheela’s do not fit a fertility function. But this theory is no less empowering, as the ability to carry and give life can be seen as one of the greatest signifiers of a woman’s strength and power, the vulva being the gate between the womb and life, and so it is not hard to see how the Sheela’s could be associated with fertility.

My favorite interpretation is that the Sheila na Gig are used to ward off evil, that they perform a powerful type of Anasyrma as a form of protection. Anasyrma is the gesture of lifting up the skirt or kilt, connected with religious rituals, eroticism, and lewd jokes. It is a form of exhibitionism similar to flashing, but differs in that instead of being for the implicit purpose of the exhibtionist’s own sexual arousal, it is instead done only for the effect of the onlooker.

Anasyrma is effectively the exposing of the genitals, always by a women, and is interesting in that it, is the woman using her genitals as an apotropaic device that could be interpreted as empowering to herself, while historically and socially it has widely been men exposing their genitals to women in a form of power over women, an unwanted sexual advance. We can see similar figures to the Sheila na Gigs performing anasyrma such as the ancient Greek figure Baubo. Baubo’s performance of anasyrma is performed to create humor and laughter. There is also the Putta di Porta Tosa figurine in Milan mounted at an entrance in the city wall. The figure shows a woman standing, facing outward towards any potential attackers and she is holding a knife while lifting her garment to expose herself with the other. This is another example of a statue using anasyrma for protection. Another interesting example of this is Jean de La Fontaine’s painting ‘Nouveaux Contes’ showing a woman lifting up her skirt to terrify the devil himself. This shows the anthropic power that anasyrma has been believed to have, that it is strong enough to ward off the worst evils. A story from The Irish Times (September 23, 1977) reported a potentially violent incident involving several men, which was averted by a woman exposing her genitals to the attackers.

It is not only the exposing of female genitals that has mythical powers but the female body in general. In a similar vein to Queen Maeve and the power of menstruation that I spoke of before, Pliny the Elder wrote that a menstruating woman who uncovers her body can scare away hailstorms, whirlwinds and lightning. Another interesting example of sexuality and eroticism having powerful effects on the earth is Balkan Pagan traditions where women would run into the fields and lift their skirts to scare the gods and end the rain. This was brilliantly explored by Marina Abramovic in her performance piece 'Balkan Erotic Epic’ where she dressed in traditional folk costumes and reenacted these ancient rituals.

In Africa woman have in the past, and still do, strip naked as a curse and as a means to ward off evil. Women give life and so they can also take it away. Women invoke this curse under the most extreme cases, causing the men they curse to an extreme form of ostracism. It was used by women in Nigeria during the second Liberian Civil War and against President Laurent Gbagbo of the Ivory Coast, cursing his rule. In 2002 members of the Niger Delta Women for Justice occupied the Chevron Texan oil company in Escravos to protest for better treatment from the company. When the military showed up to remove them the women threatened to naked curse them and so the soldiers did not even touch them.

These are just a few examples of the influence and history of the female body and supernatural powers believed to be held by women around the world. There are undoubtedly even more examples than this, but I found these examples particularly interesting when exploring the female body and genitals in art and performances. For a subject often surrounded in shame and taboo it is intriguing to see learn of its use in forms of protest, its perceived influence over nature, life and death and war. It seems clear that despite an attempt from external forces to stigmatize the power of the female body, there is a undeniably history of it’s power in every culture.

With my project I am seeking to channel the different interpretations of what the Sheela na Gig means and the power of the female body in different culture’s, particularly Irish, legends. I have created my own interpretation of the Vulva using only sticks and wool, which is fitting, as Irish women have been weaving for centuries. By wearing my brightly colored 'vulva’ and bringing attention to it I am performing my own type of anasyrma, alluding to the different powers this brings. I am empowered by it’s ability to ward of evil, to scare men and to evoke fear in an enemy. I am empowered by presenting my own version of female sexuality as opposed to the usual presentation of female sexuality that is catered towards the male gaze. I am empowered by performing this piece on my own terms with the power from within connotations it has for me as a woman as opposed to the power over which male 'flashing’ seeks to bring. I do not seek to perform this piece to make anyone uncomfortable but to bring attention to the provocative and political nature and history behind exposing the female body and genitals. I am also able to see the comedy in my performance as my act can be perceived with surprise and humor, channeling anasyrma’s power to allow for a letting go of sadness. I certainly find it to be a humorous performance and often find myself laughing while trying to perform it.

All in all what inspired me and what I want to convey with this piece is the power of the female body to provoke and protest, to be beautiful, strong, and magical. There is no denying that whether or not you believe in these stories of the powers of the female body and the female genitalia, the fact that they exist is proof enough that they must have some power, to have provoked such a strong reaction from so many different people throughout history.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Personajes, material en uso.

AVATARES, TRAMAS...

PHILIPH KALLAHAN:

Jared Padalecki.

Smaug.

Family Business Beer Company.

El Castillo Ambulante (Phil sin corazón).

House of the Dragon (trama con Leo).

MITSHA KALLAHAN:

Grace V. Cox, Danielle Campbell, Eve Hewson.

Drogon / Viserion

Light Fury (How to train your dragon 3).

HAZIEL:

Misha Collins – Castiel en Supernatural (todos sus poderes). Ángel.

THE SCRIPT:

Danny O’Donoghue. Mark Sheehan. Glen Power.

JAMIE A. DHOIRE:

Sam Heughan.

Outlander – Craigh Na Dun.

HASSON GRIAN:

Alex O’Loughlin.

Belenus, Dios de la Luz, el Sol y el Fuego (en la mitología celta).

CIARA FRASER:

Jade Thirlwall.

Cailleach Bérrie, diosa de invierno (en la mitología celta).

YENNEFER DE VENGERBERG:

Yennefer de Vengerberg (The Witcher).

Anya Chalotra.

CALIFORNIA:

Ella Eyre.

DERMOT:

Dermot Kennedy, Eamon (guardianes de Drakkars).

FORMAS DE CONTACTO:

Gmail: [email protected]

Instagram: @MitshaKallahanF / @Darkmelodiesgar

Ask: @PhilKallahan

0 notes

Text

Divindades associadas aos Sabbats

(se eu deixar alguém de fora, por favor comentem abaixo e me deixem saber! Vou adiciona-los a lista)

🌲 Yule 🌲

Alcione, Amaterasu, Apolo, Astarte, Balder, Bona Dea, Cailleach, Demeter, Dionísio, Frau Holle/Holda, Frigga, Hodr, Holly King, Hórus, Isis, Jesus, La Befana, Senhor da desordem/Papai Noel, Lugh, Mitra, Morrigan, Odin, Osiris, Pandora, Ra, Saturno, Mulher Aranha, Virgem Maria

🌸 Imbolc 🌸

Oengus, Afrodite, Aradia, Ártemis, Atena, Bastet, Brigit, Ceres, Cerridwen, Diana, Eros, Fauno, Februa, Februus, Gaia, Hestia, Inanna, Minerva, Pan, Vênus, Vesta

🐣 Ostara 🐣

Adonis, Afrodite, Asase Yaa, Attis, Coatlicue, Cibele, Dylan, Eostre, Freya, Isis, Dama do Lago, Homem Verde, Ma-ku, Minerva, Mitra, Odin, Osíris, Perséfone, Rheda, Saraswati

🌹 Beltane 🌹

Ártemis, Astarte, Baco, Bes, Cernunnos, Diana, Dionísio, Flora, Homem Verde, Hera, Kokopelli, Marve, Maia, Oxun, Pan, Príapo, Sheela-na-Gig, Xochiqurtzal

🌻 Litha 🌻

Aditi, Apolo, Amaterasu, Áton, Beiwe, Hestia, Hórus, Huitzilopochtil, Juno, Lugh, Sulis Minerva, Sunna/Sol, Vesta

🌾 Lammas 🌾

Adonis, Attis, Baal, Ceres, Cronos, Dagon, Danu, Deméter, Hestia, Lugh, Mercúrio, Neper, Parvati, Pomona, Renenutet, Saturno, Sobek, Tailtiu, Tammuz, Vesta

🍁 Mabon 🍁

Arawn, Arcanjo Miguel, Astarot, Baco, Cernunnos, Cerridwen, Dagda, Dionísio, Dumuzi, Epona, Freya, Homem Verde, Hathor, Hermes, Inanna, Ishtar, Isis, Modron, Morrigan, Pamona, Perséfone, Mulher Cobra, Thor, Thoth

💀 Samhain 💀

Arianhod, Belili, Cernuno, Cerridwen, Dagda, Demeter, Dionísio, Ereshkigal, Hathor, Hecate, Hel, Herne, Inanna, Isis, Lilith, Ma'at, Marduk, Minerva, Morrigan, Nantosuelta, Nephthis, Odin, Osiris, Pan, Pomona, Sheshat, Tammuz, Tara, Thor

Post Original

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Os celtas integram uma das mais ricas civilizações do mundo antigo. Há quem aponte que as origens desta civilização remontam ao processo de desenvolvimento da Idade do Ferro, quando estes teriam sido os responsáveis pela introdução do manuseio do ferro e da metalurgia no continente europeu. De fato, o reconhecimento do povo celta pode se definir tanto pela partilha de uma cultura material específica, quanto pelo uso da língua céltica. Mas nada é certo de verdade. A riqueza desse povo é, para nós, uma espada com fio amolado dos dois lados. Se de um lado, a grande diversidade cultural dentro daquilo que podemos chamar de “Celta” nos faz ter a possibilidade de ir bem longe no proveito e análise de tradições, hábitos, vestes e rituais, temos a questão de definição. Quem afinal foram os Celtas, se não havia uma coesão, um indício que bem determinasse ser celta ou não ser Celta (questão próxima acontece com os ciganos, mas isso é papo para outro post).

Vamos pensar então na língua como forma de identificação mesmo. Talvez seja o caminho mais coerente.

Pela inexistência de dados e documentos originais, grande parte da história dos celtas é hipotética.

O que sabemos hoje é que a “vivência” Celta como sociedade se estendeu por 19 séculos, desde 1800 a.C. — quando, culturalmente, os celtas se individualizaram entre os demais povos indo-europeus — até o século I d.C, época da decadência motivada pela desunião entre suas várias tribos e a invasão romana às terras que ocupavam.

O período mais brilhante da história celta transcorre, aproximadamente, entre 725 e 480 a.C., na Era de Hallstatt, início da civilização céltica do ferro e, também, da invasão à Europa. Os celtas se instalaram em uma imensa região das atuais repúblicas Tcheca, Eslovaca, Áustria, sul da Alemanha, leste da França e da Espanha, alcançando a Grã-Bretanha. Nesta fase, se consolidaram os traços particulares da civilização céltica.

Os Celtas foram o primeiro povo civilizado da Europa, até onde sabemos.

Eles teriam chegado neste continente junto com a primeira onda de colonização ainda em 4.000 AC. (Muito mais tempo atrás do que a sua mente consegue retroagir nesse momento).

Destacaram-se dos outros povos que chegaram na mesma época porque acreditavam em uma terra prometida e iam em busca dela, o que não deixava de ser uma ideia quase messiânica. Em 1800 AC já tinham a sua cultura e o território totalmente estabelecidos. E isso enquanto os gregos nem sequer existiam para falar de filosofia, certo, errado ou metafísico. Há quem diga que, na verdade, os gregos vieram de Colônias Celtas – muitas são as incertezas sobre esse povo.

Os Celtas, até onde sabemos, ocupavam a região da Alemanha, Bélgica, Holanda, Dinamarca, França e Inglaterra.

Esse povo tão antigo não era lá muito pacífico. É fácil notar isso quando vemos que não raramente confundimos Vikings com Celtas pelas aparências e por características expansionistas.

Para se ter uma ideia do como esse povo tão ligado à natureza era guerreiro, para que um menino fosse considerado homem, ele deveria passar por uma prova (uma espécie de iniciação), que consistia em sair da cidade onde morava, sair da sua região, e trazer a cabeça de qualquer pessoa que não fosse Celta.

Somente com a cabeça na mão é que se fazia uma tatuagem no corpo do menino, cujo simbolismo determinava que ele agora era homem adulto.

(Bons os tempos em que as tatuagens tinham significados, não é?)

Chegaram a desenvolver uma escrita, mas o sistema alfabético e vocabular fora feito de forma tão complexa que até hoje são poucos os que se atrevem a desvendá-la. A escrita era considerada mágica, e somente os seus sacerdotes é que a aprendiam, estes eram os famosos druidas. Inventaram lendas belíssimas, que estão entre as mais famosas dos dias de hoje. Como por exemplo as história do rei Arthur e os cavaleiros da távola redonda, Tristão e Isolda, além de terem inventado quase todos os contos de fadas (que foram se modificando com o tempo).

Sem dúvida alguma, os Celtas eram um povo com muita ciência unida a muita mística. Existem relatos praticamente inexplicáveis, como o de uma operação de transplante de coração, realizado em 1000 a.C., e o de Navios voadores que soltavam fumaça enquanto desciam e pousavam no meio dos campos da Inglaterra. A eles é creditada a construção do Stonehenge, embora o próprio povo tenha negado essa feitura em muitos escritos.

O mistério de Stonehenge é só um décimo do grande mistério que cerca esse povo fantástico.

O povo Celta tinha uma estrutura de família bem peculiar, se consideravam animais (por isso a ligação tão profunda com a natureza) e acreditavam em uma infinidade de deuses e demônios. Aliás, aqueles duendes bonitinhos com potes de ouro são fruto da mitologia Celta. Se bem que os duendes eram bem mais “trolls” do que aparentam hoje em dia; como pequenos espíritos zombeteiros.

Uma coisa muito bacana presente na cultura Celta é o poder feminino. Em uma literatura histórica tão extensa e cheia de seres bons e maus, guerreiros, algozes e vítimas, a protagonista é sempre a figura feminina. Isso mesmo: se você viu ou leu Brumas de Avalon, aliás, deverá lembrar que as mulheres eram essenciais na sociedade Celta. Além de serem as responsáveis pela reprodução e gestação de numerosos filhos, muitas das mulheres eram sacerdotisas. Isso sem falar nas deusas do Panteão Celta.

Os celtas não misturavam panteões de outras culturas e nem cultuavam deuses celtas de outras tribos. Apesar das semelhanças, cada ramo celebrava seus deuses locais, seguindo apenas as referências das tradições pertencentes à sua terra natal, com exceção de algumas divindades pan-célticas.

Eram grandes nomes deste Panteão:

Áine: deusa do amor, da fertilidade e do verão. Rainha dos reinos feéricos dos Tuatha de Danann, conhecida como “Cnoc Áine” (Monte de Áine) é a soberana da terra e do sol, associada ao solstício de verão, às flores e as fontes de água. Áine (Enya) – filha de Manannán Mac Lir – representa a luz brilhante do verão. Como uma deusa solar, podia assumir a forma de uma égua vermelha.

Brigit / Brigid / Brighid / Brig: deusa reverenciada pelos Bardos, tanto na Irlanda como na antiga Bretanha, cujo nome significa “Luminosa, Poderosa e Brilhante”. Brighid, a Senhora da Inspiração, era filha de Dagda, associada à Imbolc e as águas doces de poços ou fontes, que ficam próximos às colinas. É a deusa do fogo, da cura, do lar, da fertilidade, da poesia e da arte, especialmente a dos metais. Brighid também é uma deusa guerreira, conhecida como “Bríg Ambue“, a protetora soberana dos Fianna. Brighid era consorte de Bres e mãe de Ruadan, que foi morto ao espionar os Fomorianos. Ela sentiu profundamente a morte do filho, dando origem ao primeiro lamento poético de luto irlandês, conhecido como keening.

Cailleach: é a deusa da terra e das rochas, diz a lenda que ela criou os morros e as montanhas a sua volta, ao atirar pedras em um inimigo. Na mitologia irlandesa e escocesa é conhecida também como a “Cailleach Bheur”, que significa mulher velha, às vezes, descrita de capuz com o rosto azul-cinzento. Geralmente é vista como a deusa da última colheita (Samhain), dos ventos frios e das mudanças, aquela que controla as estações do ano, a Senhora do Inverno.

Dagda: deus da magia, da poesia, da música, da abundância e da fertilidade. No folclore irlandês, Dagda era chamado de “o bom deus”, possuía todas as habilidades sendo bom em tudo, “Eochaid Ollathair” (Pai de todos) e “Ruad Rofhessa” (Senhor de Grande Sabedoria), considerado mestre de todos os ofícios e senhor de todos os conhecimentos. Consorte de Boann, teve vários filhos, entre eles Brighid, Oengus, Midir, Finnbarr e Bodb, o Vermelho. Dagda tinha um caldeirão mágico, o Caldeirão da Abundância, que nunca se esvaziava e uma harpa de carvalho chamada “Uaithne”, que fazia com que as estações mudassem, quando assim o ordenasse. Além disso, tinha um casal de porcos mágicos que podiam ser comidos várias vezes e que sempre reviviam, bem como, um pomar que, independente da estação, dava frutos o ano todo.

Dana / Danu / Danann: considerada a principal deusa mãe da Irlanda e do maior grupo de deuses, os Tuatha Dé Danann, o Povo de Dana ou o Povo Mágico (Daoine Sidhe), a tribo dos seres feéricos. A Terra de Ana (Iath nAnann), às vezes, é identificada como Anu ou Ana, seu nome significa “Conhecimento”. Era consorte de Bilé e mãe de Dagda. Em Munster, na Irlanda, Dana foi associada a dois morros de cume arredondados, chamados de “Dá Chich Anann” ou “Seios de Ana”, por se parecem com dois seios. É a deusa da fertilidade, da terra e da abundância.

Macha: deusa da fertilidade e da guerra, filha de Ernmas, junto com as irmãs Badb e Morrighan, podia lançar feitiços sobre os campos de guerra. Após uma batalha os guerreiros cortavam as cabeças dos inimigos e ofereciam a Macha, sendo este costume chamado de a “Colheita de Macha”. É a deusa dos equinos, que durante a gravidez foi forçada a uma corrida de cavalos. Quando chegou ao final, entrou em trabalho de parto e deu à luz a gêmeos. Antes de morrer, Macha colocou uma maldição sobre os homens da província para, que em tempos de opressão e maior necessidade, eles sofreriam dores como as de um parto.

Morrigan / Morrighan: é a Grande Rainha “Mor Rioghain”, na mitologia irlandesa, da tribo dos Tuatha Dé Danann. Senhora da Guerra, possuía uma forma mutável e o poder mágico de predizer o futuro. Reinava sobre os campos de batalha e junto com suas irmãs Badb e Macha eram conhecidas pelo nome de “Três Morrígans”, relacionadas à triplicidade que, para os celtas, significava a intensificação do poder. Associada aos corvos, ao mar, as fadas e a guerra, além da associação à Maeve, rainha de Connacht, casada com o rei Ailill e à Morgana, das lendas arthurianas. Podia mudar sua aparência à vontade, como em um lobo cinza avermelhado. Nos mitos relacionou-se com Dagda e apaixonou-se pelo grande herói celta, Cu Chulainn, que despertou toda sua fúria, ao rejeitá-la. Deusa da morte e do renascimento, da fertilidade, do amor físico e da justiça.

Scathach / Scath: Seu nome significa a “Sombra”, aquela que combate o medo. Deusa guerreira e profetisa que viveu na Ilha de Skye, na Escócia. Ensinava artes marciais para guerreiros que tinham coragem suficiente para treinar com ela, pois era dura e impiedosa. Considerada a maior guerreira de todos os tempos, foi a responsável por treinar Cu Chulainn.

Não compondo uma civilização coesa, os celtas se subdividiram em diferentes povos, entre os quais podemos destacar os Belgas, Gauleses, Bretões, Escotos (eu disse ES-CO-TOS), Batavos, Eburões, Gálatas, Caledônios (A Caledônia é onde fica a Escócia) e Trinovantes. Durante o desenvolvimento do Império Romano, vários desses povos foram responsáveis pela nomeação de algumas províncias que compunham os gigantescos domínios romanos.

Lembraram de Alguém?

Do ponto de vista econômico, podemos observar que os celtas estabeleceram contato comercial com diferentes civilizações da Antiguidade. Por volta do século VI a.C., a relação com povos estrangeiros pode ser comprovada pela existência de elementos materiais de origem Etrusca e chinesa em regiões tipicamente dominadas pelas populações célticas.

Por volta do século V a.C., os Celtas passaram a ocupar outras regiões que extrapolavam os limites dos rios Ródano, Danúbio e Sanoa. A presença de alguns armamentos e carros de guerra atesta o processo de conquista de terras localizadas ao sul da Europa. Após se estenderem em outras regiões europeias, os celtas foram paulatinamente combatidos pelas crescentes forças do Exército Romano.

A sociedade céltica era costumeiramente organizada através de clãs, onde várias famílias dividiam as terras férteis, mas preservavam a propriedade das cabeças de gado. A hierarquia mais ampla da sociedade céltica era composta pela classe nobiliárquica, os homens livres, servos, artesãos e escravos. Além disso, é importante destacar que os sacerdotes, conhecidos como druidas, detinham grande prestígio e influência. Como todas as castas sacerdotais ao longo da evolução da humanidade, diga-se de passagem.

Donos de uma cultura tão bela, a alma do povo Celta ainda vive: Atualmente, a Irlanda é o país onde se encontram vários vestígios da cultura céltica.

E mesmo após a cristianização do povo da natureza por São Patrício, muitos de seus elementos permaneceram perpetuados.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Livros e quadrinhos relacionados aos celtas:

Alma celta

Guia da Mitologia Celta: A magia da mitologia celta

Stonehenge

Rei Arthur e os Cavaleiros da Távola Redonda – Coleção Clássicos Zahar

As Brumas de Ávalon

Coleção Asterix

[BTTP CULTURA] O Povo Celta – As Deusas, o Ferro, As Belezas e Mistérios. Os celtas integram uma das mais ricas civilizações do mundo antigo. Há quem aponte que as origens desta civilização remontam ao processo de desenvolvimento da Idade do Ferro, quando estes teriam sido os responsáveis pela introdução do manuseio do ferro e da metalurgia no continente europeu.

#Áine#amor#animais#Árvore da Vida#Asterix#austríacos#Batavos#Belgas#Bretões#Brighid#brigida#brumas de avalon#cabeça do inimigo#Cailleach#Caledônios#cavaleiros da távola redonda#Celta#celtas#cervos#civilização céltica#contos de fadas#corvos#cruz#cultura#cultura céltica#cura#d&d#d7d#Dagda#Dana

1 note

·

View note

Text

Os celtas integram uma das mais ricas civilizações do mundo antigo. Há quem aponte que as origens desta civilização remontam ao processo de desenvolvimento da Idade do Ferro, quando estes teriam sido os responsáveis pela introdução do manuseio do ferro e da metalurgia no continente europeu. De fato, o reconhecimento do povo celta pode se definir tanto pela partilha de uma cultura material específica, quanto pelo uso da língua céltica. Mas nada é certo de verdade. A riqueza desse povo é, para nós, uma espada com fio amolado dos dois lados. Se de um lado, a grande diversidade cultural dentro daquilo que podemos chamar de “Celta” nos faz ter a possibilidade de ir bem longe no proveito e análise de tradições, hábitos, vestes e rituais, temos a questão de definição. Quem afinal foram os Celtas, se não havia uma coesão, um indício que bem determinasse ser celta ou não ser Celta ( questão próxima acontece com os ciganos, mas isso é papo para outro post).

Vamos pensar então na língua como forma de identificação mesmo. Talvez seja o caminho mais coerente.

Pela inexistência de dados e documentos originais, grande parte da história dos celtas é hipotética.

O que sabemos hoje é que a “vivência” Celta como sociedade se estendeu por 19 séculos, desde 1800 a.C. — quando, culturalmente, os celtas se individualizaram entre os demais povos indo-europeus — até o século I d.C, época da decadência motivada pela desunião entre suas várias tribos e a invasão romana às terras que ocupavam.

O período mais brilhante da história celta transcorre, aproximadamente, entre 725 e 480 a.C., na Era de Hallstatt, início da civilização céltica do ferro e, também, da invasão à Europa. Os celtas se instalaram em uma imensa região das atuais repúblicas Tcheca, Eslovaca, Áustria, sul da Alemanha, leste da França e da Espanha, alcançando a Grã-Bretanha. Nesta fase, se consolidaram os traços particulares da civilização céltica.

#gallery-0-13 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-13 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-13 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-13 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Os Celtas foram o primeiro povo civilizado da Europa, até onde sabemos.

Eles teriam chegado neste continente junto com a primeira onda de colonização ainda em 4.000 AC. (Muito mais tempo atrás do que a sua mente consegue retroagir nesse momento).

Destacaram-se dos outros povos que chegaram na mesma época porque acreditavam em uma terra prometida e iam em busca dela, o que não deixava de ser uma ideia quase messiânica. Em 1800 AC já tinham a sua cultura e o território totalmente estabelecidos. E isso enquanto os gregos nem sequer existiam para falar de filosofia, certo, errado ou metafísico. Há quem diga que, na verdade, os gregos vieram de Colônias Celtas – muitas são as incerteza sobre esse povo.

Os Celtas, até onde sabemos, ocupavam a região da Alemanha, Bélgica, Holanda, Dinamarca, França e Inglaterra.

Esse povo tão antigo não era lá muito pacífico. É fácil notar isso quando vemos que não raramente confundimos Vikings com Celtas pelas aparências e por características expansionistas.

Para se ter uma ideia do como esse povo tão ligado à natureza era guerreiro, para que um menino fosse considerado homem, ele deveria passar por uma prova ( uma espécie de iniciação), que consistia em sair da cidade onde morava, sair da sua região, e trazer a cabeça de qualquer pessoa que não fosse Celta.

Somente com a cabeça na mão é que se fazia uma tatuagem no corpo do menino, cujo simbolismo determinava que ele agora era homem adulto.

(Bons os tempos em que as tatuagens tinham significados, não é?)

Chegaram a desenvolver uma escrita, mas o sistema alfabético e vocabular fora feito de forma tão complexa que até hoje são poucos os que se atrevem a desvendá-la. A escrita era considerada mágica, e somente os seus sacerdotes é que a aprendiam, estes eram os famosos druídas. Inventaram lendas belíssimas, que estão entre as mais famosas dos dias de hoje. Como por exemplo as história do rei Arthur e os cavaleiros da távola redonda, Tristão e Isolda, além de terem inventado quase todos os contos de fada ( que foram se modificando com o tempo ).

Sem dúvida alguma, os Celtas eram um povo com muita ciência unida a muita mística.Existem relatos praticamente inexplicáveis, como o de uma operação de transplante de coração, realizado em 1000 a.C., e o de Navios voadores que soltavam fumaça enquanto desciam e pousavam no meio dos campos da Inglaterra. A eles é creditada a construção do Stonehenge, embora o próprio povo tenha negado essa feitura em muitos escritos.

O mistério de Stonehenge é só um décimo do grande mistério que cerca esse povo fantástico.

#gallery-0-14 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-14 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-14 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-14 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

O povo Celta tinham um estrutura de família bem peculiar, se consideravam animais ( por isso a ligação tão profunda com a natureza) e acreditavam em uma infinidade de deuses e demônios. Aliás, aqueles duendes bonitinhos com potes de ouro são fruto da mitologia Celta. Se bem que os duendes eram bem mais “trolls” do que aparentam hoje em dia; como pequenos espíritos zombeteiros.

Uma coisa muito bacana presente na cultura Celta é o poder feminino. Em uma literatura histórica tão extensa e cheia de seres bons e maus, guerreiros, algozes e vítimas, a protagonista é sempre a figura feminina. Isso mesmo: se você viu ou leu Brumas de Avalon, aliás, deverá lembrar que as mulheres era essenciais na sociedade Celta. Além de serem as responsáveis pela reprodução e gestação de numerosos filhos, muitas das mulheres eram sacerdotisas. Isso sem falar nas deusas do Panteão Celta.

Os celtas não misturavam panteões de outras culturas e nem cultuavam deuses celtas de outras tribos. Apesar das semelhanças, cada ramo celebrava seus deuses locais seguindo apenas as referências das tradições pertencentes à sua terra natal, com exceção de algumas divindades pan-célticas.

Eram grandes nomes deste Panteão:

Áine: deusa do amor, da fertilidade e do verão. Rainha dos reinos feéricos dos Tuatha de Danann, conhecida como “Cnoc Áine” (Monte de Áine) é a soberana da terra e do sol, associada ao solstício de verão, às flores e as fontes de água. Áine (Enya) – filha de Manannán Mac Lir – representa a luz brilhante do verão. Como uma deusa solar, podia assumir a forma de uma égua vermelha.

Brigit / Brigid / Brighid / Brig: deusa reverenciada pelos Bardos, tanto na Irlanda como na antiga Bretanha, cujo nome significa “Luminosa, Poderosa e Brilhante”. Brighid, a Senhora da Inspiração, era filha de Dagda, associada à Imbolc e as águas doces de poços ou fontes, que ficam próximos às colinas. É a deusa do fogo, da cura, do lar, da fertilidade, da poesia e da arte, especialmente a dos metais. Brighid também é uma deusa guerreira, conhecida como “Bríg Ambue“, a protetora soberana dos Fianna. Brighid era consorte de Bres e mãe de Ruadan, que foi morto ao espionar os Fomorianos. Ela sentiu profundamente a morte do filho, dando origem ao primeiro lamento poético de luto irlandês, conhecido como keening.

Cailleach: é a deusa da terra e das rochas, diz a lenda que ela criou os morros e as montanhas a sua volta, ao atirar pedras em um inimigo. Na mitologia irlandesa e escocesa é conhecida também como a “Cailleach Bheur”, que significa mulher velha, às vezes, descrita de capuz com o rosto azul-cinzento. Geralmente é vista como a deusa da última colheita (Samhain), dos ventos frios e das mudanças, aquela que controla as estações do ano, a Senhora do Inverno.

Dagda: deus da magia, da poesia, da música, da abundância e da fertilidade. No folclore irlandês, Dagda era chamado de “o bom deus”, possuía todas as habilidades sendo bom em tudo, “Eochaid Ollathair” (Pai de todos) e “Ruad Rofhessa” (Senhor de Grande Sabedoria), considerado mestre de todos os ofícios e senhor de todos os conhecimentos. Consorte de Boann, teve vários filhos, entre eles Brighid, Oengus, Midir, Finnbarr e Bodb, o Vermelho. Dagda tinha um caldeirão mágico, o Caldeirão da Abundância, que nunca se esvaziava e uma harpa de carvalho chamada “Uaithne”, que fazia com que as estações mudassem, quando assim o ordenasse. Além disso, tinha um casal de porcos mágicos que podiam ser comidos várias vezes e que sempre reviviam, bem como, um pomar que, independente da estação, dava frutos o ano todo.

Dana / Danu / Danann: considerada a principal deusa mãe da Irlanda e do maior grupo de deuses, os Tuatha Dé Danann, o Povo de Dana ou o Povo Mágico (Daoine Sidhe), a tribo dos seres feéricos. A Terra de Ana (Iath nAnann), às vezes, é identificada como Anu ou Ana, seu nome significa “Conhecimento”. Era consorte de Bilé e mãe de Dagda. Em Munster, na Irlanda, Dana foi associada a dois morros de cume arredondados, chamados de “Dá Chich Anann” ou “Seios de Ana”, por se parecem com dois seios. É a deusa da fertilidade, da terra e da abundância.

Macha: deusa da fertilidade e da guerra, filha de Ernmas, junto com as irmãs Badb e Morrighan, podia lançar feitiços sobre os campos de guerra. Após uma batalha os guerreiros cortavam as cabeças dos inimigos e ofereciam a Macha, sendo este costume chamado de a “Colheita de Macha”. É a deusa dos equinos, que durante a gravidez foi forçada a uma corrida de cavalos. Quando chegou ao final, entrou em trabalho de parto e deu à luz a gêmeos. Antes de morrer, Macha colocou uma maldição sobre os homens da província para que em tempos de opressão e maior necessidade, eles sofreriam dores como as de um parto.

Morrigan / Morrighan: é a Grande Rainha “Mor Rioghain”, na mitologia irlandesa, da tribo dos Tuatha Dé Danann. Senhora da Guerra, possuía uma forma mutável e o poder mágico de predizer o futuro. Reinava sobre os campos de batalha e junto com suas irmãs Badb e Macha eram conhecidas pelo nome de “Três Morrígans”, relacionadas à triplicidade que, para os celtas, significava a intensificação do poder. Associada aos corvos, ao mar, as fadas e a guerra, além da associação à Maeve, rainha de Connacht, casada com o rei Ailill e à Morgana, das lendas arthurianas. Podia mudar sua aparência à vontade, como em um lobo cinza avermelhado. Nos mitos relacionou-se com Dagda e apaixonou-se pelo grande herói celta, Cu Chulainn, que despertou toda sua fúria, ao rejeitá-la. Deusa da morte e do renascimento, da fertilidade, do amor físico e da justiça.

Scathach / Scath: Seu nome significa a “Sombra”, aquela que combate o medo. Deusa guerreira e profetisa que viveu na Ilha de Skye, na Escócia. Ensinava artes marciais para guerreiros que tinham coragem suficiente para treinar com ela, pois era dura e impiedosa. Considerada a maior guerreira de todos os tempos foi a responsável por treinar Cu Chulainn.

Não compondo uma civilização coesa, os celtas se subdividiram em diferentes povos entre os quais podemos destacar os Belgas, Gauleses, Bretões, Escotos ( eu disse ES-CO-TOS) , Batavos, Eburões, Gálatas, Caledônios ( A Caledônia é onde fica a Escócia) e Trinovantes. Durante o desenvolvimento do Império Romano, vários desses povos foram responsáveis pela nomeação de algumas províncias que compunham os gigantescos domínios romanos.

Lembraram de Alguém?

Do ponto de vista econômico, podemos observar que os celtas estabeleceram contato comercial com diferentes civilizações da Antiguidade. Por volta do século VI a.C., a relação com povos estrangeiros pode ser comprovada pela existência de elementos materiais de origem Etrusca eCchinesa em regiões tipicamente dominadas pelas populações célticas.

Por volta do século V a.C., os Celtas passaram a ocupar outras regiões que extrapolavam os limites dos rios Ródano, Danúbio e Sanoa. A presença de alguns armamentos e carros de guerra atesta o processo de conquista de terras localizadas ao sul da Europa. Após se estenderem em outras regiões europeias, os celtas foram paulatinamente combatidos pelas crescentes forças do Exército Romano.

#gallery-0-15 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-15 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-15 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-15 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

A sociedade céltica era costumeiramente organizada através de clãs, onde várias famílias dividiam as terras férteis, mas preservavam a propriedade das cabeças de gado. A hierarquia mais ampla da sociedade céltica era composta pela classe nobiliárquica, os homens livres, servos, artesãos e escravos. Além disso, é importante destacar que os sacerdotes, conhecidos como druidas, detinham grande prestígio e influência. Como todas as castas sacerdotais ao longo da evolução da humanidade, diga-se de passagem.

Donos de uma cultura tão bela, a alma do povo Celta ainda vive: Atualmente, a Irlanda é o país onde se encontram vários vestígios da cultura céltica.

E mesmo após a cristianização do povo da natureza por São Patrício, muitos de seus elementos permaneceram perpetuados.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

[CULTURA] O Povo Celta – As Deusas, o Ferro, As Belezas e Mistérios. Os celtas integram uma das mais ricas civilizações do mundo antigo. Há quem aponte que as origens desta civilização remontam ao processo de desenvolvimento da Idade do Ferro, quando estes teriam sido os responsáveis pela introdução do manuseio do ferro e da metalurgia no continente europeu.

#amor#animais#Árvore da Vida#Asterix#austríacos#brigida#brumas de avalon#cabeça do inimigo#Celta#cervos#corvos#cruz#cultura#cura#d&d#d7d#deusas#doença#dragão#druidas#escotos#fertilidade#gálatas#gauleses#ginger#gravidez#guerra#inteligência#irlandeses#macha

0 notes