#just. know that this man essentially built a torture machine to give himself powers and then built another one to get rid of said powers

Text

Horrifying concept:

Sparrow keeps becoming reliant on whatever he gets spliced with because his psychology isn't meant to be spliced with anything.

Like, hybrids have a built in resistance, or mental block, that allows them to retain individuality while still being mixed with something. Sparrow doesn't have that. So, no matter what he merges with, its will is going to overpower his. It happened with the chip blatently overriding his wants while he was a golem and we can kinda see it happening more subtly with the skulk and setting up a new base.

I can't wait until he notices and builds another death contraption

#new life smp#owengejuicetv#sparrow new life#quinn talks#mcyt#listen. i know most of my followers have no idea what im talking about#just. know that this man essentially built a torture machine to give himself powers and then built another one to get rid of said powers#its fun here#this is like semi genuine#i do think theres something wrong with sparrow though#<- said lovingly

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

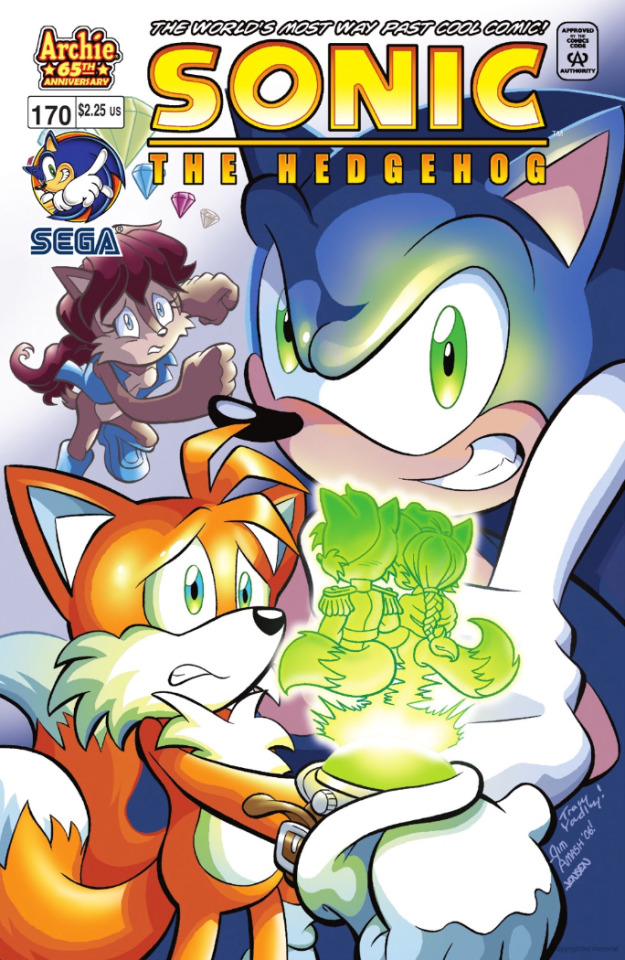

238. Sonic the Hedgehog #170

Comings and Goings

Writer: Ian Flynn

Pencils: Tracy Yardley

Colors: Jason Jensen

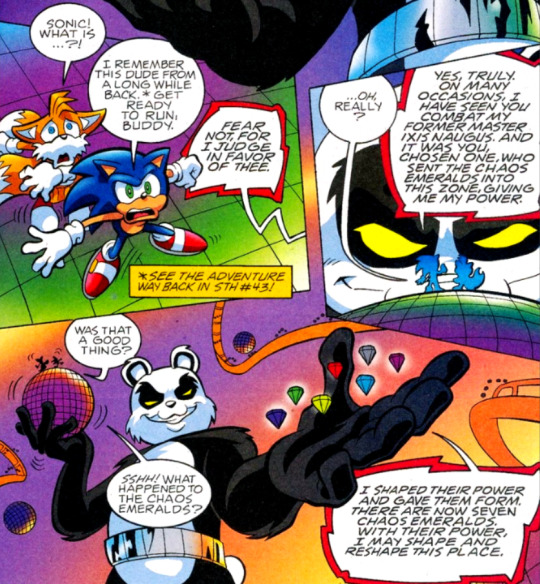

Today's main story is mostly just more clean-up on Ian's part. Sally is worried about her father, still in a coma in bed after being poisoned by Evil Antoine, but Sonic and Tails arrive to reassure her, as Tails and Rotor have cooked up something special that should allow them to retrieve a Chaos Emerald for a quick cure. This "something special" turns out to be a pair of star posts (yeah, Ian really wanted to align this more with the games) which can open portals to alternate zones through some unexplained-as-of-yet means. Sonic and Tails end up in what was once the Zone of Silence but is now the Special Zone, which looks significantly different now that the energies of the Chaos Emeralds have altered it so much. They quickly run into another living being within the zone - Feist, the Giant (literally) Panda! Oh boy, remember this one-off character from StH#43? I guess he was meant to be just another one of Naugus' random lackeys within the Zone of Silence, but it seems like he's taken his once-in-a-lifetime chance to become a god with the power of the emeralds.

Da-dadada-daaaaaa! Yep, after two-hundred thirty eight issues of these comics, the Chaos Emeralds have finally attained their more recognizable forms as a group of seven distinct multicolored gems! See what I mean by clean-up? After Sonic and Tails explain their mission, Feist grants them a single emerald, the gray one, though he warns them that the next time they enter this place in search of the emeralds he will test them as he sees fit. Sonic and Tails rush the emerald to the royal bedroom, where Dr. Quack and Uncle Chuck insert it into their little… medical machine thingy and fire it up while it's attached to the unconscious former king. After a brief light show, he begins to wake up, and asks after his kingdom. He's quietly thrilled to see Elias as king, and to hear that Sally is back to working with the Freedom Fighters.

Sonic and Tails vacate the room to give the family time to talk amongst themselves, but Sally follows quickly, handing over the emerald and telling them that Merlin was looking for them. They're confused, even more so when they find Knuckles also having been called over by Merlin, but Merlin explains that he can use the power of the Chaos Emerald and Knuckles' guiding star gem combined to bring them to Argentum, allowing them to finally bring Tails' parents back. Sonic is a little miffed that he's unable to really help besides merely coming along for the ride, wishing he could take Fiona along to show her the planet, but soon they've warped halfway across the universe and find themselves standing on the Wheelworld. However, the place looks desolate and wrecked, and they can see Xorda ships in the sky battling with fleets of other, unidentified ships. Tails becomes panicked and wanders off to find his parents with Merlin following close behind, but while they're gone Rosemary and Amadeus show up, informing Sonic and Knuckles that the other ships belong to the Black Arms, and their war has been going on for several months now, devastating Argentum in the process. Wait, the Black Arms? Shadow's progenitors? Yeah, so essentially, Ian couldn't get permission from Sega to bring the Black Arms to Mobius for whatever reason, even though he was trying, so he decided to tie them up in a war with the Xorda. This would allow him to easily bring them in at any time once he got his permission, simply by having the war end and the Black Arms continue on their way to Mobius. I'll spoil it for you right now though that he never did get that permission during the course of the preboot, so that aspect of Shadow's backstory never really got explored the way it did in the games, since the Black Arms were eternally doomed to remain an offscreen presence. Anyway, Sonic, upon seeing Tails' parents, quickly rushes off and brings Tails and Merlin back for a reunion.

Aww! Man, we've been waiting a long time for this reunion! The two long-lost foxes end up in the castle, where Elias greets them and enthusiastically offers them a place in his court, which they accept, apparently having encountered some ideas during their decade away that they'd like to find a way to implement into Knothole's government. That evening, Knuckles finds Sonic hanging out near the graves of Tommy and Sir Connery, and though Knuckles is surprised given that Sonic isn't normally one to mope, Sonic explains that he's still a bit broken up over their deaths, as normally they don't lose "so many so fast." Knuckles grimly remembers his own family's disappearance, and Sonic worries that with many old and new villains rising up lately, things might be about to take a turn for the worse.

Well, funny y'all should mention Shadow! He's currently storming into Eggman's main computer room, furious, as he's just discovered that Eggman has been hiding a diary of Gerald's all along, and now he wants to know where it is…

The Island of Misfit Badniks!

Writer: Mike Gallagher

Pencils: Dave Manak

Colors: Jason Jensen

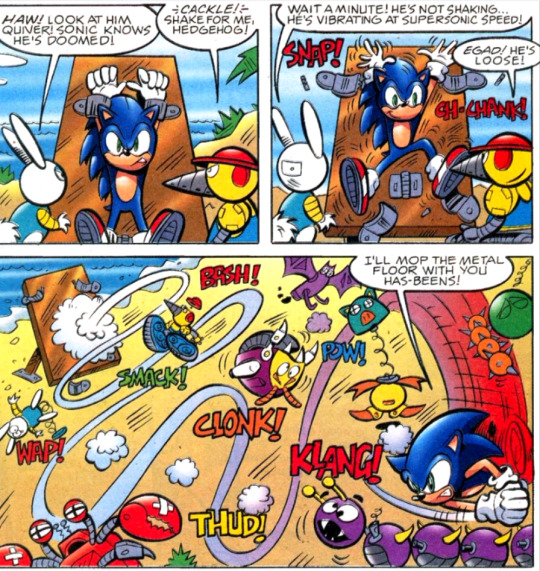

Oh, hi, Michael buddy! Haven't seen ya in some time! He's here to relieve us a bit from the more serious stuff of late with some of his characteristic slapstick charm, and a bit of a blast from the comic's past! Sonic, on one of his rare days off from duty, decides to take a run around the Great Forest only to accidentally stumble into an old hidden listening post of Robotnik's from the Robotropolis days. He finds a reference to an artificial island out in the ocean nearby, which was meant to be a waypoint for any defeated badniks to retreat to to await repair and/or retirement, and decides to check out if it's still there, using a piece of wood lying around nearby as a boogie board. Sure enough, the island is there, but he's surprised to find that "artificial" was a bit more literal than he expected and the place is in fact entirely made out of solid steel. Before he can explore further, he's knocked on the head from behind, and wakes up strapped to some kind of torture rack with a bunch of old badniks standing around him ready to bring the pain!

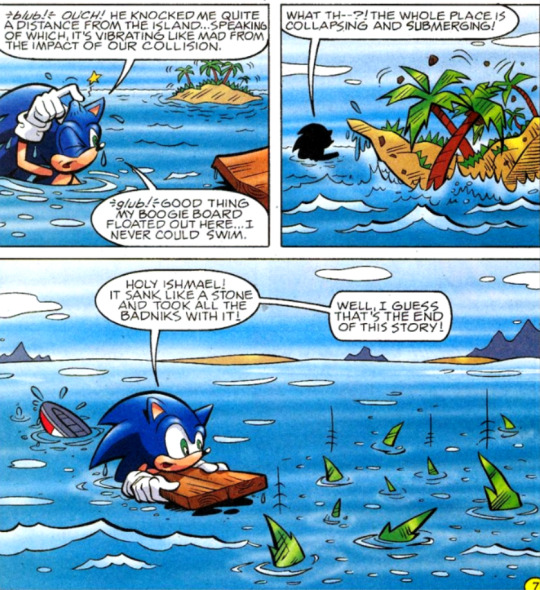

…yeah, that's about what we expected. Things are looking good until a new player arrives on the scene - none other than Pseudo-Sonic, who appeared alllllll the way back in StH#9! Damn, you're really goin' back for this one, Michael! Pseudo-Sonic has apparently been salty all these years that even though he was built to be Sonic's match as his first-ever metal doppelganger, he never got a chance to actually face off with the Blue Blur himself. The other badniks set up a contest between the two where they'll essentially run at and headbutt each other really hard, and whoever survives the impact is the winner. These two idiots actually do it, and Sonic ends up being headbutted all the way back out to sea.

Is it, though? C'mon, Sonic, you know it's never that simple! Sure enough, as he heads back to shore we discover that the badniks actually sunk the island on purpose, making it appear to be accidental while in fact setting up the island to be an underwater base where they can repair Pseudo-Sonic and plan their next revenge attack. Apparently this is "definitely not the end," so I guess we can look forward to one last visit from these guys in the future!

#nala reads archie sonic preboot#archie sonic#archie sonic preboot#sonic the hedgehog#sth 170#writer: ian flynn#writer: michael gallagher#pencils: tracy yardley#pencils: dave manak#colors: jason jensen

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deadly Fortune, Book 2, Chapter 00-1 - 15

The chapter numbering for the second book is a little weird because there are a couple 00 numbered chapters that take place before the game starts. It’s mainly stuff for Lady and what she was up to that led her to encounter the Order of the Sword.

Everything is under the cut again.

Link to the translation: https://originaldmc.github.io/DivinityStatue/Downloads.html

Link to the previous section of Notes: https://madartiste.tumblr.com/post/186824600040/deadly-fortune-book-1-chapters-6-11

Stage 00-1 (Before the game -- Lady encounters the Order)

We get some Lady! She's hunting a demon (naturally). She hears a weird noise that sounds more like a machine than a human or a demon. Lady calls out a warning because she doesn't want to accidentally shoot a person. They don't respond to her, so she decides to shoot anyway, and one of the Bianco Angelos blocks the rocket with its shield. She asks if they got lost on their way to a costume party. Though they don't answer, their posture tells Lady they're definitely listening to her. Interestingly, they don't attack her even though she attacked first, but they're still insanely strange and refuse to say or do anything to respond to her.

So she shoots them again. They scuffle a bit, she notices they've got some good gear since the armor can fly and they have motorized spears. She lands a hit and notices there is no blood. Apparently there are sometimes demons with no bodies, though it's very rare, and they can possess things -- 'Like old dolls or torture instruments' (wow). Items with significant emotional attachment to humans are their favorite shells. Lady considers that while medieval armor could possibly be possessed, this armor seems like it is far too new in construction. She also thinks that she's seen the crest that the knights are wearing before but can't remember.

Lady beats the first Bianco Angelo, noticing the blue-white lights that dissipate out of it, and is about to take some of the armor when more show up and surround her. There's a nice part where she thinks that when she was younger, she'd probably pick a fight with them, but now that she's more experienced, she understands her limitations better. She also notices they caught the demon she was after -- it has wings and a face like a dog according to her. Deciding that she doesn't like her odds, Lady hops on her bike after distracting the knights with her rocket launcher. She finds the situation strange, since they definitely could give chase but don't, and wonders why these demons possessing the armor are hunting other demons.

Stage 12 (Credo dies)

Nero is starting to lose himself inside the Savior. At first he feels completely calm and comfortable, but he can't remember who he is and can't move. After a moment, he remembers that he has to save someone.

Dante thinks of Mundus when he sees the Savior fly off. He comments that the bad guys have similar patterns.

Credo wakes up, and Dante does not care about his condition -- which seems harsh, but Dante further ruminates that Credo is a proud guy who wouldn't want sympathy from his enemy. He also is pretty sure Credo is dying. Dante correctly realizes that the plan is to open the gate to the underworld so that Sanctus can play hero. He's not impressed.

Dante thinks this is just like Temen-ni-gru, though that was built by humans. He's not overly concerned about the whole thing because 'the passage to the devil world is only a little longer.' (Not sure exactly what that means.) He also expresses that he doesn't like it when people tell him what to do or try to give him tasks, though he admires Credo's resolve and that he's managed to hold on to his humanity despite becoming a demon.

The way Credo dissolves when he dies isn't typical for a demon, and Dante thinks it's because of Credo's convictions. He thinks 'This must be the way angels sacrificed.'

Dante and Trish only took this job for entertainment which is why they didn't take it seriously. But now they feel obligated to fulfill Credo's dying request. Dante particularly finds humans who use demons to be abhorrent, and he wants to put an end to the Order. There's a line about him not being young anymore and that he's seen a lot of stuff, but Credo's death touched his heart.

Stage 00-2 (Before the game -- Lady learns about the Order)

Lady goes to a collector of supernatural items named John. It seems she doesn't like him much, and his smile creeps her out. There's a note that 'John swayed like a bald-headed man.' Whatever that means. She shows them the coat of arms (the Order's symbol). He says he knows what it is, but doesn't tell her, so Lady bribes him with some 'devil's blood.' She dislikes all the collectors because they try to flaunt their knowledge to her. Also hey remind her of Arkham.

John scoffs at her 'demon blood' because it shouldn't remain in liquid form. It either evaporates quickly after being spilled or crystallizes. But she knows better and tells him to "Forget it." He changes his tune and asks if the blood is real and how it could be liquid. She explains that if demon blood is poured onto a stone statue in a ritual, it can create a liquid demon called a Blood Bat. When the Bat is hit with high heat, it turns back into a stone statue, and that what she's got in her vial is part of the Blood Bat. She offers to let him set fire to the blood since it will turn to stone. And after a while, it will turn back into a liquid.

John tries out the trick and is super stoked. He grabs her hand in his excitement -- which she doesn't care for. John digs into his collection and brings back a book which has the Order's coat of arms on it: "The Teaching Code of the Order of the Sword." Ooooh, Lady saw the symbol in her father's study when she was a little kid. The book is about 4-500 years old, though the Order existed before that.

There's a 'Demon Sociology Group'???

John asks her if she wants a more recent book of their teachings, though it'll be a bit hard to get. He's very, very pleased with her gift, so he's willing to go the extra mile for her this time. Lady thinks there's something seriously shady happening, so she says yes.

Stage 13 (Dante vs the Blitz)

Agnus has been in the Savior during all this, so he visits Sanctus in the control room. The Savior has some automatic functions, but needs a human to do the more complex stuff. He's disappointed in how little Sanctus changed with his transformation, wondering if it's because Sanctus is so old. (There's a good translator's note that says that Angus considers switching between human and devil forms to be a 'passage to heaven.')

Agnus actually finds himself afraid of Sanctus and realizes it's because the old geezer is juiced full of powerful energy. He's ashamed of doubting Sanctus. He thinks that the power of the devil forms is related to the strength of the person's spirit. Interestingly, Agnus admits he is not a devout believer in Sparda. He's more interested in studying devils than he is in following Sparda and mainly used his position to satisfy his scientific curiosity. But seeing Sanctus… he's filled with awe and believes in his vision.

Angus thinks that Sanctus needs a new title because he should rule over not just the human world but the underworld too. (Good luck with that.) He calls him "Emperor of the Devil." Sanctus just laughs and gives him Yamato to go unlock the Hell Gate. Agnus pauses and asks what Sanctus will do about Dante -- which Sanctus thinks should be easy with the Savior.

Sanctus also seems to plan to blame all the insanity that's about to happen on Dante. Dante is unpredictable, Agnus worries that they'll be in trouble if they underestimate him. Aha, Agnus thinks that with Yamato he will have enough strength to beat Dante. (Is there something about Yamato and making people feel powerful??) Now that Credo is dead and he is Sanctus' most trusted confidant, Agnus is feeling pretty ballsy.

Back to Dante: Dante clearly smells demons afoot. There are some funky dark clouds gathering that shoot lightning at a demon. Oh, the Blitz. Interesting note: In Dante's experience, if a demon doesn't have eyes or a nose, it usually has some kind of organ that replaces those functions. Demons without eyes are rare, though the Blitz has really good hearing.

He uses Ebony and Ivory and thinks of Nell Goldstein (awww), remembering her saying that a normal person can't fire their guns like a machine gun -- which is why she designed his guns to handle being fired at an inhuman rate. Dante considers his guns to be partners. He also doesn't normally bring other weapons besides the pistols and Rebellion, but he brought along Coyote-A this time.

Rebellion is the first weapon Dante got, and Sparda trained him to fight with a sword. There's a line about how the sword symbolizes the power to protect a loved one.

Fighting the Blitz, Dante considers that a dying demon's only instinct is destruction, essentially wanting to kill everything around it when it goes. Hence the Blitz blowing itself up.

Stage 00-3 (Lady hires Dante and Trish)

Lady is considering what to do about the Bianco Angelos. They are obviously collecting demons for something, but they don't attack her unless she attacks them first. She debates about going to Fortuna, but isn't keen on the idea, though if the Angelos keep interfering with her hunts, she's losing money and reputation. She's chillin' on the sofa in her own room, thinking about what to do. Demon hunters are pretty rare and scattered around the country, but she knows a few people. Obviously, the person she thinks can deal with this is Dante.

She actually wonders if Dante is his real name because some people call him Tony -- though she knows this was an old alias. She heads out to his place, calls his area of town a 'slum.' Lady strolls into the office without knocking. She thinks that Dante would eat pizza or drink if he has nothing better to do, and that he eats sundaes like a little kid.

Lady doesn't know too much about Trish, only that she used to be Dante's partner and that she's not human. Trish is apparently traveling the world right now, but sometimes swings by Devil May Cry.

Dante turns her job down because he's suspicious of Lady's methods -- she sticks him with the damage fees all the time -- but Lady knows he doesn't really take jobs for the money. He just wants to kill demons. Apparently Trish knows about the Order of the Sword but doesn't say anything.

Lady has her doubts about Dante really being the son of Sparda, and when she asks him how much he knows, Dante says who can know everything about their dad? Lady finds the answer strange even for Dante. He gets his interest hooked at the point that Lady says they worship Sparda like a god on Fortuna. Despite what he'd like, Dante still wants to know about his father.

While she's talking, Trish is picking up the Sparda and some Devil Arms, but Dante doesn't notice. Lady doesn't care who takes the job.

Stage 14 (Dante vs. Echidna)

Agnus is in the Opera House. Only a few people know how to get to the Hell Gate under the building. The secret passage was built way before the Opera House, and Sanctus ordered Agnus to figure out where it was. The Hell Gate directly under the center of the city. Apparently the space is very creepy. He's excited to see the culmination of his research.

The original Hell Gate developed over time, caused by the 'magical difference between the human world and the underworld.' The little Hell Gates Agnus made concentrated magical energy in the area, allowing them to open the the Real Hell Gate all at once.

Back to Dante: He sees all the demons spilling out of the big Hell Gate and says "That's… not good." (Hah!) Even he is apprehensive about dealing with that many demons at once. He also is worried that they won't be able to save all the people.

Dante doesn't usually hang on to his Devil Arms. In fact, he sells them to pay his debts.

He's counting on the Order knights to protect the citizens, so he's focusing on getting back his Devil Arms and closing the small Hell Gates. Dante is confident he can win, but he knows he can't destroy the Savior with Nero inside since that could kill the poor kid.

In Mitis Forest, the air is so dense with demon energy that a normal person would just pass right out. Dante literally is looking forward to 'playing' with some tough demons.

He banters with Echidna, and there's a note that demons who can speak human languages are always chatty and show off. Dante grabs his Devil Arm before the fight in this. I guess there's a question if Gilgamesh is a true Devil Arm (which makes a bit of sense since DMC5 says it's actually a special kind of metal from the Underworld.). Dante Rising Dragon's Echidna and is a bit disappointed that she gets taken out so fast. It sounds like he gets intensely bored fighting demons and does all his showy moves mainly to entertain himself.

Stage 15 (Dante vs. Dagon)

Lady POV: She's on a boat on her way to Fortuna. The sailors can't believe she wants to go there with all the crazy stuff going on. She tells one of them that when she gets there, she'll put a stop to it… probably (she doesn't let them hear that last part). Three days after she left, Trish sent Lady a letter asking her to come by Fortuna in a month to pick her and Dante up. Lady gets attacked by a Mephisto. The sailor's name is Ben, and Lady tries to protect him and the ship.

She beats the demon but a ton more show up. She suggests Ben run to the lifeboat.

Back to Dante: He tries to get frisky with Dagon's ladies who tease him and dart away -- though he's already aware the frog demon is there thanks to the smell. Dagon has similarly poor human speech, like Bael, that Dante can barely understand. He also doesn't know who Dante is -- and Dante's disappointed by that. He asks if Dagon is "from the country."

The demon frogs come out of the hell gate before Dante kills Dagon. He Enemy Steps his way over to the Hell Gate to grab Pandora. To use Pandora's different forms, Dante just has to picture them in his mind. It was either built by or WAS an 'ordinance worker in the demon world.' I'm thinking built by because this demon also built a bunch of other guns. (Was it Machiavelli? Same guy who made Artemis?) Pandora can read the 'memory and the imagination' of the user to change into many shapes. When Trish first saw the Argument form for Pandora, she said Dante is just a big kid. He admits that he probably got the idea from a comic book or movie but still thinks it's cool. Also he got hit with the Omen transformation on accident before. He refers to that as 'tragic consequences.'

Link to the next section of notes: https://madartiste.tumblr.com/post/186847847540/deadly-fortune-book-2-chapters-16-20

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 12: Of Gods and Bondage (Loki x OFC Pairing)

They say people love and choose to accept life while fear death because life is a beautiful lie while death is the painful truth. In theory that's true although death itself isn't painful, only the transition to it is which means it's actually life that's painful, you don't feel much of anything when you're dead...unless you're me. Loki was a beautiful master of lies himself but was accepted and loved by few, while I was a pain in the ass necromancer that ruled the dead, so in a way we were stark opposites, our magic/power cancelled each other out in a way. We did have a few things in common though, betrayed by our own people, demi-gods, a fondness for daggers. I sometimes wondered just what he saw in me though, a quiet tall, ever observing man like himself going for the unquiet undead zombie queen. It couldn't just be the great sex or what we have in common though. He seemed far too clever to go for that alone. Then I wondered what his reaction would be when he really sees what I am, what I can do. Would he be afraid, intrigued? He rarely showed any fear, curiosity definitely, and caution, but he was probably trained his whole life to never show fear or weakness no matter what he was faced with.

I studied his face when he thought I wasn't looking while we stood in the park and enjoyed the tranquility. He told me stories of Asgard, the golden city, the glorious realm, things he missed terribly that unfortunately my realm couldn't compare. He spoke of other realms his brother, their friends, and he were sent "to keep the peace" which really meant beat the living shit out of till they surrendered and followed Odin's rule. The more he spoke of his past, the more I came to see just how and why he loathed his father so much, the guy, god or not, was a massive bully and I hated those cretins.

"Thor says its not a place but a people and the people there sound like they royally suck, pun intended, so if you think about it, Asgard wasn't really your home if you didn't feel all that welcomed there. Home is where the cuddles are."

"Are you trying to convince me you're my home now?" he asked in amusement.

"Is it working?" I replied hopefully.

He paused during our stroll and opened his mouth to retort but nothing came out as his expression of mirth turned to caution. "Do you hear that?"

I blinked and listened and if I could feel the cold again, I'd probably have goosebumbs, there wasn't a sound in the park, no bird, no barks of dogs being walked, no people talking or leaves rustling. "My zombie senses are tingling." Utter silence was completely unnatural, even when there wasn't a soul in sight.

Loki must have sensed something because he suddenly spun around, his back to me and seemed to use himself as a shield once more before his body went rigid then twitchy in front of me as he fell. I dropped to my knees by his side, his veins bulging, his face contorting in agony and I saw something small and metallic attached to his neck and put two and two together.

"The voltage will go up before you can touch it," a new voice warned me.

I didn't move from where I knelt but narrowed my eyes and looked for the owner of the voice that jumped from a tree to the ground. A hydra agent judging by the symbol on his otherwise blank black uniform. Others appeared from their own hiding spot.

"Do as I say and his blood won't boil and fry him alive from the electrical shocks."

My eyes went to Loki's though rage boiled my own blood at a bunch of asshats knocking down my god so easily. He couldn't even nod let alone talk but his eyes seemed to say enough to make me do as they said. I looked back to the man with the machine gun and narrowed my eyes.

"Stand up slowly, hands where we can see them and don't move unless we tell you. Boys, search her for any arcane weaponry."

I did as commanded and stood up and was immediately surrounded and padded down for anything which I almost found amusing as I was the weapon, why would I carry more?

"Nothing, sir," one reported.

I smirked at this, not taking my eyes off the commander who glared hard at me. He walked over to me, probably thinking he was safe if I was unarmed, and grabbed me by the throat.

"Tell me where they are or I'll crush your windpipe."

"You know what I'm not doing? I'm not using my windpipe," I hissed. "What is dead can never die."

He squeezed harder before letting go but didn't back down. "Lock em both up separately, if I can't break you, I'll break him and make you watch. Make sure they're not being watched either, we wouldn't want to have a tail."

They cuffed Loki from where he lay stiff on the ground and muzzled him as well like they had with me, then turned down the metal patch on his neck so he could at least stand for himself before forcing him away from me as I let myself be cuffed as well though they didn't bother with the muzzle on me this time, I was already too pissed for words anyway. We were led to a super shady looking armored truck, the commander sitting across from me, hands not leaving his firearm.

"They told me you couldn't be broken, they showed me recordings of what they tried on you and how you'd just smile or mock them when they stuck you full of blades and experiments."

"I've been told they tried that on me for five years...you know the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Your scientists are actually legit mad, not just evil, have fun with that."

"Oh don't worry about that, if we can't do it to you, we'll do it to someone less immune to our methods." He glanced over at the silently fuming god at the other end of the truck.

"You think this is the first time someone I love has been used against me that I'd just roll with your punches?" I asked incredulously. "Or is it because you people are terrible at judgments of character that think I've been alone till him? Did the ones you roped into your mess tell you about me? I mean really tell you about me? Did they explain why I don't feel physical pain? Why I can't be killed? Or are you the type to just go in guns blazing and skip the questions entirely till someone drops dead?"

"They told me enough."

"If that were true, you wouldn't be doing this, you'd drop this entire mission of yours and leave the necromancy to the few of us left that haven't changed sides. Because if you did know enough about me...you'd run and you'd sleep with one eye opened till I drag your soul to hell and use your empty skull for a cereal bowl."

"You really think that will scare me?"

"I work at a screampark, I know full well what makes even the toughest soldiers tremble, if you break him, you're next."

"You're in no position to threaten me."

"You sure? The way I see it, you need me more than I need you. You think by torturing him that I'll comply when you're only really giving me that much more reason to tear you apart, your actions are the tinder on which you burn. Then again by killing the others and attempting to break me before this, you got my attention so either way you're still fucked. I'm in every position to threaten you and so much more."

The truck stopped before he could retort and we could hear even more soldiers coming to the truck, no doubt to make sure we don't do anything against them or escape. We were led out and Loki was steered away from me and my line of sight while the commander and his team led me in the opposite direction elsewhere into the building that looked perfectly normal, nothing fancy, nothing suspicious, didn't even look abandoned like some hideouts were, people in business suits and briefcases were coming and going while I was being led in by the team. As I was being walked down to the basement I spotted another traitor I knew personally and stopped suddenly, not caring that I was completely surrounded and tapped on the glass wall separating him and the people he was working with from me. He turned around and went pale while I grinned maniacally. "Hiya Georgie!" I then let the team drag me away, I had left my mark on him, he knew what would happen the second I got free and found him. I was led to a large control type room with giant glass container filling up about half of it, a control panel on one side most likely for whatever's being contained. A middle aged man with scars distorting his face wearing an expensive business suit stood at the center of the room along with two scientists in lab coats and clipboards. He turned when he heard me walk in with the team and set his sights on me before glancing at the commander.

"Ah good, you caught her again, let's hope we have better luck and results this time around. My name is Dr. Feist, I'm the head of this operation and you are Noelle, are you not? The infamous necromancer that leveled an entire building without needing any explosives."

"And yet you thought it smart to bring me into another building?" I questioned.

"Well yes, we couldn't do any of this out in the open where we can be repeatedly interrupted by your new friends and if you try anything we don't want you to do well..." he snapped his fingers and the door to the glass cell opened up and Loki was suddenly thrown into it, the door sealing shut behind him as he got to his feet and bright abnormal looking lights clicked on in the cell.

I glanced at the panel controlling the room and back at Loki as he looked around attempting to get a bearing on his surroundings while the lights got brighter and I suddenly realized what was going on as he seemed to almost wilt where he stood before sitting down on the built in bench. They essentially put him into a small greenhouse, melting the Frost Giant.

"How long do you think he'll last in there?" Feist continued. "His people couldn't survive outside their own frozen planet without the casket of ancient winters I'm told."

My eyes didn't leave Loki as his normally stiff, proper posture seemed to deflate with the rising heat in the room, he looked tired, worn down, like it was a struggle just to sit and stay awake for him. "What do you want?"

"Every necromancer carries a blade and a stone, where are yours?"

"They already searched me, but you'll have to take me out to dinner before you can strip me yourself."

"Then where if not on your person?"

"Where only I alone can get to it, but I'm sure you already know what happens when someone not marked tries to play with things that aren't theirs."

"Clever lady. You're right, we can't touch them, that's why we brought in people who can."

I snickered at this. "The others you either bribed or threatened to join forces with? Let them try."

"Well since you don't have those things we were hoping for, we'll find other uses for you while we have you. Put her in the other holding cell for now while we dig deeper."

I was led away from the controls and down to the level where Loki was kept to another cell but before they could shove me in, I bolted to Loki's desperately and pressed my hands against the glass between us. He saw me despite the heavy eyelids and it damn near broke my heart seeing him look so weak as he held a hand up to match mine against the glass. Our eyes met once more before I was forced away and locked in.

#loki fanfiction#loki fanfic#loki romance#avengers#hydra#necromancer#necromancy#nell the necromancer#loki x OC#loki x original female character#loki x nell

0 notes

Text

Check out the weirdest New Year's Eve facts we could find

New Post has been published on https://nexcraft.co/check-out-the-weirdest-new-years-eve-facts-we-could-find/

Check out the weirdest New Year's Eve facts we could find

What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s newest podcast. Season one of The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week is available on iTunes, Soundcloud, Stitcher, PocketCasts, and basically everywhere else you listen to podcasts. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. You’ve got just enough time to binge the whole bunch before our second season arrives early next year.

Check out our surprise holiday episode below:

Fact: The treadmill was originally designed as a way to occupy and employ prisoners.

By Claire Maldarelli

January is a rough time for staying in shape. In at least half the world, the days are as short as they are cold. But, at least for me, working out indoors can be even worse. Case in point: The treadmill. Some gym rats swear by the device, but I see the machine as pure torture. For me, the mental frustration of running in place is far worse than the numbing chill the cold air brings.

As it turns out, that psychological distress is not far from what the exercise machine was originally designed for.

In 1818, a prominent civil engineer named William Cubitt was working as a millwright designing, building, and fixing mills. At that time, he apparently became increasingly interested in the “welfare” of prisoners. So, he took it upon himself to reconfigure a mill such that it required human movement to keep it going, which is how it got the name treadmill.

The device was essentially a giant hollow cylinder with an iron frame around it, with wooden steps built around that frame—far more similar to today’s stairmasters. Forty prisoners at a time would climb up on the steps and as they did so, the mill would turn. The faster the wheel turned, the more rapidly the prisoners would have to keep climbing. It was mainly used to crush grains such as corn.

It was quickly adopted by all the major gallows in the United Kingdom and soon came to the United States as well. The U.S. abolished its use first, and Great Britain followed with the Prisoner’s Act of 1898.

Fast forward to 1968, when aerobic exercise was quickly becoming recognized as the key ingredient to staying healthy. A man named William Staub redesigned the existing treadmill to fit inside people’s homes and appeal to the masses, not just the obsessed athlete. His treadmill was called the PaceMaster 600 and didn’t look all that different from the fancy treadmills of today.

So, the next time you step on the treadmill master this new year, remember that you, unlike the first users of the device, always have the option of stepping off. Hopefully that alone will keep you going—or get you to run outside.

Fact: The origin of sparkling wine isn’t all about Dom Perignon

By Rachel Feltman

When most people ponder the origin story of the bubbles in their New Year’s Eve flutes, they’ll hear the story of a 17th-century monk named Dom Perignon. But while Perignon certainly started the Champagne fever in France, fizzy wine likely didn’t begin in his monastery: Three decades earlier a British scholar had published observations on “sparkling” wines—the first recorded use of that word to describe the beverage—he’d seen produced around England. Sorry, Dom.

Even after Champagne took off in France, it wasn’t like the wine we know today for quite some time. For starters, it was extremely sweet—sweeter than most dessert wines you’ll find today, in sharp contrast to the dry flavors we expect from the classiest modern bottles. It was also either cloudy or kind of flat: the second fermentation process that gives sparkling wine its bubbles also leaves a lot of yeast trapped in the bottle, and they form cloudy detritus as they die. The easiest way to deal with this, for decades of production, was to simply pour the wine from one bottle to another before selling it, skimming out the offending fungi. But all this agitation meant the wine would sparkle quite a bit less upon its second uncorking. The solution came from a widow named Madame Clicquot, a trailblazing entrepreneur in a time when few French women had anything to do with business. She and her colleagues came up with the idea of riddling: wine gets its second fermentation on a special rack that allows the bottles to tilt, and winemakers periodically agitate them slightly before setting them back down at a slightly-more-extreme angle. At the end of the process, the yeast has all been coaxed to sit in a single layer at the very top of the bottle. This means you can simply uncork the wine and skim the sediment, then seal it back up—instead of shaking your delicate product around as you filter it from one bottle to another. There are some wineries where this still happens by hand.

For a bonus fact about why the heck we watch a ball drop every New Year’s Eve, listen to this week’s episode (embedded above).

Calendar power hour

By Eleanor Cummins

You could say we’re publishing this special episode of The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week on Christmas Day, December 25, 2018. But you could just as rightly say we’re publishing it on December 26, 2018—if you’re on the other side of the international dateline. Or on December 12, 2018 if you’re in imperial Russia and still using the Julian calendar. Or on December 25, 106 if you’re somehow accessing the internet from North Korea (hello!) and count in Juche years. In anticipation of our transition to 2019, I decided to look into what a year really is, and how it’s changed from ancient Rome to 1920s Greece to today. Find out more on Weirdest Thing!

If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on iTunes. You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in weirdo merchandise from our Threadless shop.

Written By Rachel Feltman, Claire Maldarelli, Eleanor Cummins

0 notes

Text

The Making of Gennady Golovkin, Boxing's Silent Superstar

"We live in a morbid society here in America," says Abel Sanchez. "We want to see somebody get hurt. We go to the bullfights not to see the bullfighter win, but to see the bullfighter get thrown up in the air."

Gennady Gennadyevich Golovkin came to America seven years ago from Germany, but he was born in Karaganda, a city in Kazakhstan, the Earth's ninth-largest country, dotted with underground coal mines that once fed the machine of Soviet industry. He was an amateur champion in his country, won an Olympic silver medal in 2004 and spent years knocking out every fighter Europe could throw at him before he finally showed up at Sanchez's gym in Big Bear, California, looking for someone to help him break into the U.S. market.

"I explained to him what America wants and what America needs, and if he gave me the chance, without any interruptions, I could make him that," says Sanchez, a construction contractor from Tijuana with a steady stable of fighters in Big Bear. "But he had something I couldn't teach, and that's the punch."

That punch has elevated Golovkin to the biggest stage in boxing. His life has revolved around the sport for decades, but slowly it is beginning to revolve around him. He is the real thing: a superstar, a knockout artist, a brand with increasingly strong endorsements—the custom Hublot watch, the Apple Watch ad, the Air Jordan gear. He walks with a placid swagger, in and out of the boxing ring, like a velociraptor in repose. In 37 professional fights, he has never lost, and he has never been knocked down.

Golovkin also does not enjoy suffering fools, but he does it well. Those endorsements that feed his family's future—and the promotional machine that sustains them—require a modicum of forced smiles, a flurry of necessary evils.

"Boxing is not a business," Golovkin recently told a Mexican reporter during a day of interviews and a public, outdoor workout in 100-degree weather in Los Angeles. "It is a sport."

But it is a huge business. On Saturday, Golovkin will face off against Saul "Canelo" Alvarez in the year's biggest boxing match to feature two actual boxers. Millions of people will spend $69.99 to watch on Pay Per View. Thousands will spend even more to see it live in Las Vegas. The naked capitalist theater of the recent fight between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Conor McGregor was a strangely attractive vortex of attention this summer, but the matchup with Golovkin and Alvarez is one the boxing world has wanted for years.

The fight takes place on Mexican Independence Day, one of boxing's marquee weekends. It features Mexico's most famous and accomplished contemporary superstar in Alvarez, and one of the country's favorite outsiders in Golovkin—a man who has claimed to fight "Mexican-style": with constant pressure, fearlessly, brutally.

Canelo Alvarez is Mexico's biggest boxing superstar. Photo: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports.

"We as Mexicans remember the greats and how they fought. And the greats of today, or the elite of today—Mexican fighters—don't fight the way our heroes used to fight," Sanchez says. "When [Golovkin] goes out there and puts it out on the line, the Mexican fan remembers those days when we used to have those kind of fighters."

This spring, Alvarez defeated Julio Cesar Chavez Jr., the son of Mexico's most iconic fighter. The fight, a mismatch from conception, was essentially a staged showdown for Mexican supremacy of Pay Per View boxing, the level at which a boxer's checks get substantially larger. By defeating Chavez Jr., Alvarez set himself up as the legitimate heir of Mexico's boxing tradition. In Golovkin, who is favored by oddsmakers—and adored by many Mexican fans—he faces the perfect rival.

"If you were to search the world to find the two people who know the most about how to construct and conduct their lives, maximize what they can do as a prizefighter, these are the two guys," says Jim Lampley, the HBO boxing commentator who has seen many of Golovkin's fights from ringside. "They train monastically. They live quiet, controlled personal lives. They are not out there presenting themselves crazily or for attention on social media."

So now, after a summer of dick-swinging from Mayweather and McGregor, boxing has a narrative less about spectacle and more about honor: Alvarez, the heavily marketed and relentlessly scrutinized son of a country that reveres its bloodsport heroes, will meet Golovkin, a boy born in a soot-soaked corner of the Soviet empire—in a city that grew out of a labor camp, in a society shaped by the warped, paranoid mind of Joseph Stalin—who grew into the man they call "Triple-G."

The mines of Golovkin's home city were built on several hundred thousand backs, and knees, and crushed hopes. The miners working there, and the population tasked with feeding that labor, were internally exiled citizens; ethnic minorities from the empire's vast corners; farmers who resisted Stalin's forced collectivization of agriculture; people who maybe were suspected of thinking (or, God save you, saying) something negative about Soviet life—packed into train cars and put to work. Babies in Karangada were kept a half-hour's walk away from their mothers, who were required to walk there and back several times a day to nurse them until they were two, at which point they were put up for adoption. Prisoners were tortured; some were tied up and left outside in the sub-zero winter temperatures.

In the 1930s, the gulag camp system phased into a working-class city, choked with coal dust. In 1982, in a neighborhood called Maikuduk, twins were born to a Russian man and his half-Korean wife. (Nearly everyone of Korean descent in the Soviet Union was sent to Karaganda in 1937; anyone with ties to an external country was seen as a threat, regardless of their Soviet citizenship.)

He started boxing at 10: city champion, regional champion, champion of the Kazakhstan Republic, Asian champion, Asian games—like the Asian Olympics—world youth champion, world amateur champion, Olympic finalist. He's like a professor.

The twins, Maxim and Gennady, had two older brothers, Sergey and Vadim, who explained to their younger siblings the need to defend themselves: Karaganda in the last days of the Iron Curtain was a tough place, and it got much tougher after the Soviet Union's collapse. A small group of citizens with enough foresight in this shaky, pirate capitalism were able to manipulate wealth for personal gain, while their countrymen were left without basic needs, without jobs or with currencies that didn't mean anything. In the 1990s, the city's last hospital was turned into a casino.

The twins preferred soccer, but Sergey and Vadim took them to a boxing gym. Years later, Sergey and Vadim would both die fighting in the Russian Army—the where, when, and how are still unknown to the family.

Maxim was the better boxer, by all accounts, but Gennady pushed himself harder as an amateur, losing only 5 of 350 fights in a country with one of the world's strongest boxing programs. He won a silver medal for Kazakhstan in the 2004 Olympics, but wanted to get out of the amateur current. After signing with a promoter and moving to Germany, he spent years knocking people out in Europe as a pro.

"He started boxing at 10: city champion, regional champion, champion of the Kazakhstan Republic, Asian champion, Asian games—like the Asian Olympics—world youth champion, world amateur champion, Olympic finalist," Max Golovkin said of his brother's pedigree. "He's like a professor."

Golovkin knocks out Curtis Stevens. Photo: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports

But Gennady wasn't getting the challenges he felt he deserved, and had no shot at breaking into the larger boxing market, so his German managers began scouring the U.S. for options. In 2010, they arrived in California, and met with Sanchez, whose Summit gym in Big Bear was a secluded place, 7,000 feet above sea level, where he could embrace a monastic training schedule.

They looked at some videos of Golovkin's fights. Sanchez spoke no Russian, and Golovkin spoke no English. Communication was primarily physical, a pantomimed twisting and shifting of weight to transfer power from one hand to another. Then Sanchez showed him a video of Julio Cesar Chavez, the beloved Mexican champion, fighting Edwin Rosario in 1987.

Chavez pursued Rosario for the entire fight, keeping him cornered, repeatedly bullying him against the ropes. Rosario had heart; he stayed upright the whole time, but his lips and nose were busted, and one eye swelled to a close by the 10th round.

"Chavez is turning this into an abattoir of Rosario's blood," intoned Larry Merchant, who was calling the fight for HBO. For Sanchez, a trainer whose hyperbolic praise for his fighters is one of the tools that helps Golovkin's mythical status, this was the type of violence he believed Golovkin was capable of doling out.

"I said to him, 'If you give me three years, I promise you that in three years, you'll be the best middleweight, you'll be undefeated, you'll be world champion, and we won't be able to get you fights. Give me three years, don't interrupt.' Still, to this day, he doesn't argue, he doesn't question, he does what he's told," Sanchez said. "Three years went by, and just like I said, he was the undefeated middleweight champion and nobody wanted to fight him."

"He's always looking at them with this predatory look, they can't seem to find space for escape from him.

It didn't take long for Golovkin, under Sanchez's power-first tutelage, to start turning heads. His penchant for knocking opponents out (33 KOs in those 37 fights) is what has endeared him to fans who will pay premium fees to watch him. His polite demeanor and dazzling smile have endeared him to the brands that make him the face of their products: outside of his myriad endorsements in Kazakhstan, he's the first boxer to have been endorsed by Chivas, and has been fitted for suits by the exclusive Bijan tailoring boutique on Rodeo Drive. At a time when boxing's ability to attract new fans is being overshadowed by the rising popularity of mixed martial arts, for such companies to attach themselves to Golovkin is a testament to his marketability.

For a while, his reputation had many opponents ducking him. He has not really ever been rattled, opting instead to apply a cold, steady pressure that leads to a breaking of the spirit. A velociraptor has no emotional investment in you. It just wants to eat.

"It's very unsettling to opponents," says Lampley, the HBO commentator, who often yells "KAZAKH THUNDER!" as Golovkin inevitably dismantles a foe. "They all talk about the fact that he's constantly directly in front of them, he's always looking at them with this predatory look, they can't seem to find space for escape from him, and that all becomes a difficult obstacle both mentally and physically."

In his fight against Golovkin last fall, Kell Brook, an undefeated British welterweight champion who had come up two weight classes for the bout, snapped Golovkin's head back. This is a rare sight. Golovkin's opponents are almost always running, moving away from him.

Brook, sensing a rare weakness in Golovkin, hit him with several more combinations; the crowd, at the 02 Arena in London, stood up, roaring. Golovkin retreated. It was rumored that he had been ill in the days leading up to the fight, which would have explained this display—or anything short of gracefully robotic pursuit. Or maybe he was just playing possum.

"I'm not sure you can take the Kell Brook fight as legitimate evidence of Gennady's capabilities," said Lampley, citing the potential need for Golovkin to lay some bait for Alvarez, who still would not agree to fight him. "He was attempting to say to potential opponents—most particularly Canelo, and Canelo's surrounding brain trust—'Look, I'm vulnerable. There's no reason to stay away.'"

Golovkin broke Brook's right orbital socket in the next round. Brook's corner stopped it in the 5th. After fighting in the center of his country's second-largest arena, Brook was taken to the hospital in an ambulance.

Curtis Stevens, a middleweight from Brownsville, Brooklyn, the neighborhood that produced Mike Tyson and Zab Judah, pushed Golovkin back multiple times in their 2013 matchup. But these were tiny victories; later, Stevens leaned against the ropes, getting his liver hammered. In the 6th round, his mother walked out. In the 8th, at which point Golovkin was playing with him like a cat with an injured mouse, Stevens's corner stopped it.

Matthew Macklin, who fought Golovkin in 2013, spent the first round trying to push him back, dipping in and out in a circle. Golovkin let Macklin wear himself out; he broke two of Macklin's ribs in the 3rd round, ending the fight.

"He was exceptionally good at range," Macklin said. "To stand off at range and try and move and box was the worst thing I could have done. It just invited more pressure."

In 2015, the quick-footed Willie Monroe Jr. tried dancing around Golovkin's attack for several rounds; when that didn't work, Monroe took the fight inside, putting his internal organs at risk. When he was knocked down for the third time, in the 6th round, he barely got up in time for the count of 10.

"You just beat it. YOU JUST BEAT IT. You gotta move faster," the referee, Jack Reiss, chided Monroe. "Do you want to continue?"

Monroe, trying to keep his face calm, mumbled something inaudible, as if he didn't want to admit it.

"DO YOU WANT TO CONTINUE?" Reiss asked again—it was on him to determine whether doing so would be dangerous for Monroe.

Monroe waited a beat, pondering the option.

"I'm done," he said, looking down.

For most of its citizens, the end of the Soviet Union was an economic trauma. Currencies were devalued overnight. Government systems of support were erased. But Kazakhstan's abundant natural resources helped it rebound a little quicker than other Central Asian republics. And in the past decade, it has invested in Gennady Golovkin.

Now he's an international hero. An increasingly large diaspora of Kazakh fans attend his fights, holding the country's flag aloft. He is plastered on billboards in cities. He recently helped inaugurate a sports complex for children in his hometown. He was named an ambassador for Astana EXPO2017, a trade and energy summit in the country's capital.

"He's like Elvis over there. Girls see him on the streets, on the sidewalk, and they start screaming," said Tom Loeffler, Golovkin's promoter. "With Kazakhstan, it really wasn't that well-known on a global basis. You had that whole thing with Borat and Kazakhstan, and Gennady's pretty much wiped out that whole image. Now, he's the best middleweight champion in the world, representing his country, and every time he gets in the ring, he's carrying the flag."

Sanchez gets email from Kazakh fans, whose references to Golovkin render him an anthropomorphic emotion. "'Take care of our pride and make sure our pride is ok, we thank you for everything you have done for our pride.' He is Kazakhstan."

Golovkin comes to parties after his own fights dressed in a tuxedo. He's an icon to his own people, a rock star in a former Soviet republic. He reportedly does 2000 situps a day. But the man who possesses these credentials is not particularly concerned with discussing them.

Seated at a table full of reporters, a few hours before stepping into an outdoor ring in downtown Los Angeles for an open workout, Golovkin seemed uneasy—which he never does during a fight. If one wanted to see a rare example of a rattled Golovkin, it would be here, in front of a billboard full of sponsor logos, taking questions. Does he feel the pressure? Why did he close his camp? Was it important to face adversity in his last fight, against Daniel Jacobs (one of the few fighters to avoid being knocked out by Golovkin)?

"Did you watch the Mayweather fight?"

Golovkin winced, shaking his head. "Maybe I'll watch it later in the week."

"What does Canelo do best?"

Golovkin shrugged. He let the question hang in the air, like a punch he didn't respect enough to dodge.

The Making of Gennady Golovkin, Boxing's Silent Superstar published first on http://ift.tt/2pLTmlv

0 notes

Text

The Making of Gennady Golovkin, Boxing’s Silent Superstar

“We live in a morbid society here in America,” says Abel Sanchez. “We want to see somebody get hurt. We go to the bullfights not to see the bullfighter win, but to see the bullfighter get thrown up in the air.”

Gennady Gennadyevich Golovkin came to America seven years ago from Germany, but he was born in Karaganda, a city in Kazakhstan, the Earth’s ninth-largest country, dotted with underground coal mines that once fed the machine of Soviet industry. He was an amateur champion in his country, won an Olympic silver medal in 2004 and spent years knocking out every fighter Europe could throw at him before he finally showed up at Sanchez’s gym in Big Bear, California, looking for someone to help him break into the U.S. market.

“I explained to him what America wants and what America needs, and if he gave me the chance, without any interruptions, I could make him that,” says Sanchez, a construction contractor from Tijuana with a steady stable of fighters in Big Bear. “But he had something I couldn’t teach, and that’s the punch.”

That punch has elevated Golovkin to the biggest stage in boxing. His life has revolved around the sport for decades, but slowly it is beginning to revolve around him. He is the real thing: a superstar, a knockout artist, a brand with increasingly strong endorsements—the custom Hublot watch, the Apple Watch ad, the Air Jordan gear. He walks with a placid swagger, in and out of the boxing ring, like a velociraptor in repose. In 37 professional fights, he has never lost, and he has never been knocked down.

Golovkin also does not enjoy suffering fools, but he does it well. Those endorsements that feed his family’s future—and the promotional machine that sustains them—require a modicum of forced smiles, a flurry of necessary evils.

“Boxing is not a business,” Golovkin recently told a Mexican reporter during a day of interviews and a public, outdoor workout in 100-degree weather in Los Angeles. “It is a sport.”

But it is a huge business. On Saturday, Golovkin will face off against Saul “Canelo” Alvarez in the year’s biggest boxing match to feature two actual boxers. Millions of people will spend $69.99 to watch on Pay Per View. Thousands will spend even more to see it live in Las Vegas. The naked capitalist theater of the recent fight between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Conor McGregor was a strangely attractive vortex of attention this summer, but the matchup with Golovkin and Alvarez is one the boxing world has wanted for years.

The fight takes place on Mexican Independence Day, one of boxing’s marquee weekends. It features Mexico’s most famous and accomplished contemporary superstar in Alvarez, and one of the country’s favorite outsiders in Golovkin—a man who has claimed to fight “Mexican-style”: with constant pressure, fearlessly, brutally.

Canelo Alvarez is Mexico’s biggest boxing superstar. Photo: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports.

“We as Mexicans remember the greats and how they fought. And the greats of today, or the elite of today—Mexican fighters—don’t fight the way our heroes used to fight,” Sanchez says. “When [Golovkin] goes out there and puts it out on the line, the Mexican fan remembers those days when we used to have those kind of fighters.”

This spring, Alvarez defeated Julio Cesar Chavez Jr., the son of Mexico’s most iconic fighter. The fight, a mismatch from conception, was essentially a staged showdown for Mexican supremacy of Pay Per View boxing, the level at which a boxer’s checks get substantially larger. By defeating Chavez Jr., Alvarez set himself up as the legitimate heir of Mexico’s boxing tradition. In Golovkin, who is favored by oddsmakers—and adored by many Mexican fans—he faces the perfect rival.

“If you were to search the world to find the two people who know the most about how to construct and conduct their lives, maximize what they can do as a prizefighter, these are the two guys,” says Jim Lampley, the HBO boxing commentator who has seen many of Golovkin’s fights from ringside. “They train monastically. They live quiet, controlled personal lives. They are not out there presenting themselves crazily or for attention on social media.”

So now, after a summer of dick-swinging from Mayweather and McGregor, boxing has a narrative less about spectacle and more about honor: Alvarez, the heavily marketed and relentlessly scrutinized son of a country that reveres its bloodsport heroes, will meet Golovkin, a boy born in a soot-soaked corner of the Soviet empire—in a city that grew out of a labor camp, in a society shaped by the warped, paranoid mind of Joseph Stalin—who grew into the man they call “Triple-G.”

The mines of Golovkin’s home city were built on several hundred thousand backs, and knees, and crushed hopes. The miners working there, and the population tasked with feeding that labor, were internally exiled citizens; ethnic minorities from the empire’s vast corners; farmers who resisted Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture; people who maybe were suspected of thinking (or, God save you, saying) something negative about Soviet life—packed into train cars and put to work. Babies in Karangada were kept a half-hour’s walk away from their mothers, who were required to walk there and back several times a day to nurse them until they were two, at which point they were put up for adoption. Prisoners were tortured; some were tied up and left outside in the sub-zero winter temperatures.

In the 1930s, the gulag camp system phased into a working-class city, choked with coal dust. In 1982, in a neighborhood called Maikuduk, twins were born to a Russian man and his half-Korean wife. (Nearly everyone of Korean descent in the Soviet Union was sent to Karaganda in 1937; anyone with ties to an external country was seen as a threat, regardless of their Soviet citizenship.)

He started boxing at 10: city champion, regional champion, champion of the Kazakhstan Republic, Asian champion, Asian games—like the Asian Olympics—world youth champion, world amateur champion, Olympic finalist. He’s like a professor.

The twins, Maxim and Gennady, had two older brothers, Sergey and Vadim, who explained to their younger siblings the need to defend themselves: Karaganda in the last days of the Iron Curtain was a tough place, and it got much tougher after the Soviet Union’s collapse. A small group of citizens with enough foresight in this shaky, pirate capitalism were able to manipulate wealth for personal gain, while their countrymen were left without basic needs, without jobs or with currencies that didn’t mean anything. In the 1990s, the city’s last hospital was turned into a casino.

The twins preferred soccer, but Sergey and Vadim, took them to a boxing gym. Years later, Sergey and Vadim would both die fighting in the Russian Army—the where, when, and how are still unknown to the family.

Maxim was the better boxer, by all accounts, but Gennady pushed himself harder as an amateur, losing only 5 of 350 fights in a country with one of the world’s strongest boxing programs. He won a silver medal for Kazakhstan in the 2004 Olympics, but wanted to get out of the amateur current. After signing with a promoter and moving to Germany, he spent years knocking people out in Europe as a pro.

“He started boxing at 10: city champion, regional champion, champion of the Kazakhstan Republic, Asian champion, Asian games—like the Asian Olympics—world youth champion, world amateur champion, Olympic finalist,” Max Golovkin said of his brother’s pedigree. “He’s like a professor.”

Golovkin knocks out Curtis Stevens. Photo: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports

But Gennady wasn’t getting the challenges he felt he deserved, and had no shot at breaking into the larger boxing market, so his German managers began scouring the U.S. for options. In 2010, they arrived in California, and met with Sanchez, whose Summit gym in Big Bear was a secluded place, 7,000 feet above sea level, where he could embrace a monastic training schedule.

They looked at some videos of Golovkin’s fights. Sanchez spoke no Russian, and Golovkin spoke no English. Communication was primarily physical, a pantomimed twisting and shifting of weight to transfer power from one hand to another. Then Sanchez showed him a video of Julio Cesar Chavez, the beloved Mexican champion, fighting Edwin Rosario in 1987.

Chavez pursued Rosario for the entire fight, keeping him cornered, repeatedly bullying him against the ropes. Rosario had heart; he stayed upright the whole time, but his lips and nose were busted, and one eye swelled to a close by the 10th round.

“Chavez is turning this into an abattoir of Rosario’s blood,” intoned Larry Merchant, who was calling the fight for HBO. For Sanchez, a trainer whose hyperbolic praise for his fighters is one of the tools that helps Golovkin’s mythical status, this was the type of violence he believed Golovkin was capable of doling out.

“I said to him, ‘If you give me three years, I promise you that in three years, you’ll be the best middleweight, you’ll be undefeated, you’ll be world champion, and we won’t be able to get you fights. Give me three years, don’t interrupt.’ Still, to this day, he doesn’t argue, he doesn’t question, he does what he’s told,” Sanchez said. “Three years went by, and just like I said, he was the undefeated middleweight champion and nobody wanted to fight him.”

“He’s always looking at them with this predatory look, they can’t seem to find space for escape from him.

It didn’t take long for Golovkin, under Sanchez’s power-first tutelage, to start turning heads. His penchant for knocking opponents out (33 KOs in those 37 fights) is what has endeared him to fans who will pay premium fees to watch him. His polite demeanor and dazzling smile have endeared him to the brands that make him the face of their products: outside of his myriad endorsements in Kazakhstan, he’s the first boxer to have been endorsed by Chivas, and has been fitted for suits by the exclusive Bijan tailoring boutique on Rodeo Drive. At a time when boxing’s ability to attract new fans is being overshadowed by the rising popularity of mixed martial arts, for such companies to attach themselves to Golovkin is a testament to his marketability.

For a while, his reputation had many opponents ducking him. He has not really ever been rattled, opting instead to apply a cold, steady pressure that leads to a breaking of the spirit. A velociraptor has no emotional investment in you. It just wants to eat.

“It’s very unsettling to opponents,” says Lampley, the HBO commentator, who often yells “KAZAKH THUNDER!” as Golovkin inevitably dismantles a foe. “They all talk about the fact that he’s constantly directly in front of them, he’s always looking at them with this predatory look, they can’t seem to find space for escape from him, and that all becomes a difficult obstacle both mentally and physically.”

In his fight against Golovkin last fall, Kell Brook, an undefeated British welterweight champion who had come up two weight classes for the bout, snapped Golovkin’s head back. This is a rare sight. Golovkin’s opponents are almost always running, moving away from him.

Brook, sensing a rare weakness in Golovkin, hit him with several more combinations; the crowd, at the 02 Arena in London, stood up, roaring. Golovkin retreated. It was rumored that he had been ill in the days leading up to the fight, which would have explained this display—or anything short of gracefully robotic pursuit. Or maybe he was just playing possum.

“I’m not sure you can take the Kell Brook fight as legitimate evidence of Gennady’s capabilities,” said Lampley, citing the potential need for Golovkin to lay some bait for Alvarez, who still would not agree to fight him. “He was attempting to say to potential opponents—most particularly Canelo, and Canelo’s surrounding brain trust—’Look, I’m vulnerable. There’s no reason to stay away.'”

Golovkin broke Brook’s right orbital socket in the next round. Brook’s corner stopped it in the 5th. After fighting in the center of his country’s second-largest arena, Brook was taken to the hospital in an ambulance.

Curtis Stevens, a middleweight from Brownsville, Brooklyn, the neighborhood that produced Mike Tyson and Zab Judah, pushed Golovkin back multiple times in their 2013 matchup. But these were tiny victories; later, Stevens leaned against the ropes, getting his liver hammered. In the 6th round, his mother walked out. In the 8th, at which point Golovkin was playing with him like a cat with an injured mouse, Stevens’s corner stopped it.

Matthew Macklin, who fought Golovkin in 2013, spent the first round trying to push him back, dipping in and out in a circle. Golovkin let Macklin wear himself out; he broke two of Macklin’s ribs in the 3rd round, ending the fight.

“He was exceptionally good at range,” Macklin said. “To stand off at range and try and move and box was the worst thing I could have done. It just invited more pressure.”

In 2015, the quick-footed Willie Monroe Jr. tried dancing around Golovkin’s attack for several rounds; when that didn’t work, Monroe took the fight inside, putting his internal organs at risk. When he was knocked down for the third time, in the 6th round, he barely got up in time for the count of 10.

“You just beat it. YOU JUST BEAT IT. You gotta move faster,” the referee, Jack Reiss, chided Monroe. “Do you want to continue?”

Monroe, trying to keep his face calm, mumbled something inaudible, as if he didn’t want to admit it.

“DO YOU WANT TO CONTINUE?” Reiss asked again—it was on him to determine whether doing so would be dangerous for Monroe.

Monroe waited a beat, pondering the option.

“I’m done,” he said, looking down.

For most of its citizens, the end of the Soviet Union was an economic trauma. Currencies were devalued overnight. Government systems of support were erased. But Kazakhstan’s abundant natural resources helped it rebound a little quicker than other Central Asian republics. And in the past decade, it has invested in Gennady Golovkin.

Now he’s an international hero. An increasingly large diaspora of Kazakh fans attend his fights, holding the country’s flag aloft. He is plastered on billboards in cities. He recently helped inaugurate a sports complex for children in his hometown. He was named an ambassador for Astana EXPO2017, a trade and energy summit in the country’s capital.

“He’s like Elvis over there. Girls see him on the streets, on the sidewalk, and they start screaming,” said Tom Loeffler, Golovkin’s promoter. “With Kazakhstan, it really wasn’t that well-known on a global basis. You had that whole thing with Borat and Kazakhstan, and Gennady’s pretty much wiped out that whole image. Now, he’s the best middleweight champion in the world, representing his country, and every time he gets in the ring, he’s carrying the flag.”

Sanchez gets email from Kazakh fans, whose references to Golovkin render him an anthropomorphic emotion. “‘Take care of our pride and make sure our pride is ok, we thank you for everything you have done for our pride.’ He is Kazakhstan.”

Golovkin comes to parties after his own fights dressed in a tuxedo. He’s an icon to his own people, a rock star in a former Soviet republic. He reportedly does 2000 situps a day. But the man who possesses these credentials is not particularly concerned with discussing them.

Seated at a table full of reporters, a few hours before stepping into an outdoor ring in downtown Los Angeles for an open workout, Golovkin seemed uneasy—which he never does during a fight. If one wanted to see a rare example of a rattled Golovkin, it would be here, in front of a billboard full of sponsor logos, taking questions. Does he feel the pressure? Why did he close his camp? Was it important to face adversity in his last fight, against Daniel Jacobs (one of the few fighters to avoid being knocked out by Golovkin)?

“Did you watch the Mayweather fight?”

Golovkin winced, shaking his head. “Maybe I’ll watch it later in the week.”

“What does Canelo do best?”

Golovkin shrugged. He let the question hang in the air, like a punch he didn’t respect enough to dodge.

The Making of Gennady Golovkin, Boxing’s Silent Superstar syndicated from http://ift.tt/2ug2Ns6

0 notes

Text

The Making of Gennady Golovkin, Boxing's Silent Superstar

"We live in a morbid society here in America," says Abel Sanchez. "We want to see somebody get hurt. We go to the bullfights not to see the bullfighter win, but to see the bullfighter get thrown up in the air."

Gennady Gennadyevich Golovkin came to America seven years ago from Germany, but he was born in Karaganda, a city in Kazakhstan, the Earth's ninth-largest country, dotted with underground coal mines that once fed the machine of Soviet industry. He was an amateur champion in his country, won an Olympic silver medal in 2004 and spent years knocking out every fighter Europe could throw at him before he finally showed up at Sanchez's gym in Big Bear, California, looking for someone to help him break into the U.S. market.

"I explained to him what America wants and what America needs, and if he gave me the chance, without any interruptions, I could make him that," says Sanchez, a construction contractor from Tijuana with a steady stable of fighters in Big Bear. "But he had something I couldn't teach, and that's the punch."

That punch has elevated Golovkin to the biggest stage in boxing. His life has revolved around the sport for decades, but slowly it is beginning to revolve around him. He is the real thing: a superstar, a knockout artist, a brand with increasingly strong endorsements—the custom Hublot watch, the Apple Watch ad, the Air Jordan gear. He walks with a placid swagger, in and out of the boxing ring, like a velociraptor in repose. In 37 professional fights, he has never lost, and he has never been knocked down.

Golovkin also does not enjoy suffering fools, but he does it well. Those endorsements that feed his family's future—and the promotional machine that sustains them—require a modicum of forced smiles, a flurry of necessary evils.

"Boxing is not a business," Golovkin recently told a Mexican reporter during a day of interviews and a public, outdoor workout in 100-degree weather in Los Angeles. "It is a sport."

But it is a huge business. On Saturday, Golovkin will face off against Saul "Canelo" Alvarez in the year's biggest boxing match to feature two actual boxers. Millions of people will spend $69.99 to watch on Pay Per View. Thousands will spend even more to see it live in Las Vegas. The naked capitalist theater of the recent fight between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Conor McGregor was a strangely attractive vortex of attention this summer, but the matchup with Golovkin and Alvarez is one the boxing world has wanted for years.

The fight takes place on Mexican Independence Day, one of boxing's marquee weekends. It features Mexico's most famous and accomplished contemporary superstar in Alvarez, and one of the country's favorite outsiders in Golovkin—a man who has claimed to fight "Mexican-style": with constant pressure, fearlessly, brutally.

Canelo Alvarez is Mexico's biggest boxing superstar. Photo: Joe Camporeale-USA TODAY Sports.

"We as Mexicans remember the greats and how they fought. And the greats of today, or the elite of today—Mexican fighters—don't fight the way our heroes used to fight," Sanchez says. "When [Golovkin] goes out there and puts it out on the line, the Mexican fan remembers those days when we used to have those kind of fighters."

This spring, Alvarez defeated Julio Cesar Chavez Jr., the son of Mexico's most iconic fighter. The fight, a mismatch from conception, was essentially a staged showdown for Mexican supremacy of Pay Per View boxing, the level at which a boxer's checks get substantially larger. By defeating Chavez Jr., Alvarez set himself up as the legitimate heir of Mexico's boxing tradition. In Golovkin, who is favored by oddsmakers—and adored by many Mexican fans—he faces the perfect rival.

"If you were to search the world to find the two people who know the most about how to construct and conduct their lives, maximize what they can do as a prizefighter, these are the two guys," says Jim Lampley, the HBO boxing commentator who has seen many of Golovkin's fights from ringside. "They train monastically. They live quiet, controlled personal lives. They are not out there presenting themselves crazily or for attention on social media."