#janez vajkard valvasor

Photo

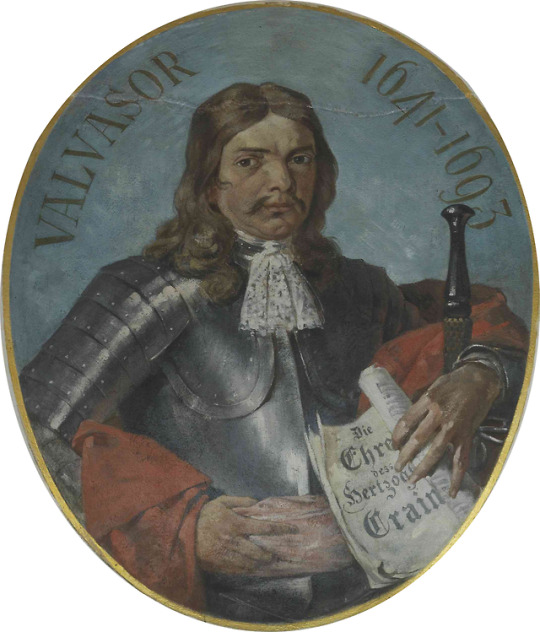

Johann Weikhard Freiherr von Valvasor or Johann Weichard Freiherr von Valvasor (Slovene: Janez Vajkard Valvasor) or simply Valvasor (baptised on 28 May 1641 – September or October 1693) was a natural historian from Carniola, present-day Slovenia, and a fellow of the Royal Society in London.

He is known as a pioneer of the study of karst phenomena. Together with his other writings, until the late 19th century his best-known work—the 1689 Glory of the Duchy of Carniola, published in 15 books in four volumes—was the main source for older Slovenian history, making him one of the precursors of modern Slovenian historiography.

Images:

1. Jurij Šubic, Janez Vajkard Valvasor, fresco, 1885, National Museum of Slovenia (ceiling), Ljubljana.

2. Johann Weichard von Valvasor, Self-portrait, copper engraving, 1689.

Sources: https://sl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janez_Vajkard_Valvasor?oldformat=true

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Weikhard_von_Valvasor?oldformat=true

1 note

·

View note

Note

So apparently Valvasor was the first person to describe vampires in print? observer. com/2017/10/history-of-vampires-johann-weichard-valvasor/

Yes! And Jure Grando is indeed considered to have been the earliest reported case of vampirism that we know of(you could say that he’s the prototype of “vampires” as we know them through popular culture today). He lived in the part of Istria that is now part of Croatia but yeah, I totally forgot it was Valvasor who described it!

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Map of the Castle of San Servolo in Die Ehre des Hertzogthums Crain by Janez Vajkard Valvasor, 1689

0 notes

Text

A Cave-Dwelling Salamander Didn't Move for Seven Years

https://sciencespies.com/news/a-cave-dwelling-salamander-didnt-move-for-seven-years/

A Cave-Dwelling Salamander Didn't Move for Seven Years

Following stories of dragons, naturalist Janez Vajkard Valvasor traveled to Vrhnika, a town now in Slovenia, in 1689. After heavy rainfall, animals resembling baby dragons were swept out of nearby caves; could this be evidence that a mama dragon was lurking inside, perhaps? Not quite. Those baby dragons were actually olm salamanders, which max out at about 12 inches long and live to be 100 years old.

Olms are a bit magical though. Lacking both pigmentation and eyesight, they are super-sensitive the feeling of light on their skin. Even more fascinating, they can sense both electric and magnetic fields. They are also pretty lazy.

According to new research published in the Journal of Zoology, one olm spent seven years without leaving its favorite spot.

“They are really good swimmers,” Eötvös Loránd University zoologist Gergely Balázs tells Science News’ Jake Buehler. Olms could “move around and try different spots to see if the neighbor is nicer, or there’s more prey… And they just don’t do it.”

Balázs and his colleagues began studying olms in the caves of eastern Bosnia-Herzegovina more than ten years ago. After several dives, the researchers began to suspect that some olms hadn’t budged. In 2010, the researchers labeled seven olms, and in 2016 tagged an additional 19. Each time they recaptured an olm, they tracked how far it had moved since the last time they saw it.

Out of 37 recaptures over the full study, only three olms moved further than 65 feet, and one olm was found in the same spot for 2,569 days, or just over seven years.

Olms live in cave systems without much food, and they can go for months or years without eating, writes the Independent’s Harry Cockburn. The animals also aren’t particularly sociable—they only mate about once every 12 years—and have no predators. The crustaceans and snails that olms snack on are both scarce and evenly distributed in their caves. It appears that if olms won’t benefit from moving, they just don’t, as Matthew Niemiller, a cave biologist at the University of Alabama in Huntsville who wasn’t involved in the study, tells Science News.

“If you’re a salamander trying to survive in this…food-poor environment and you find a nice area to establish a home or territory, why would you leave?” Niemiller says.

Other than a 2017 study that found DNA evidence of olms in caves where they hadn’t been seen before, research on these amphibious baby dragons has been completed in laboratory settings. In 2016, the first olm eggs were laid in captivity at Postojnska Caves, which gave researchers an opportunity to observe how they mature.

Most amphibians lose their external gills as they grow up, but olms never fully leave their larval state. In the latest study, Balázs and his colleagues estimated whether the animals were mature based on their size. Olms seven inches long were deemed adults. Olm larvae are susceptible to infection, so many die young, but olms that reach adulthood can live for more than a century.

Olms are listed as vulnerable species because they have a small, specific habitat range that’s broken up over many cave systems. They’ve caught the attention of naturalists from Charles Darwin, who called them “wrecks of ancient life,” to David Attenborough, who included them in his list of ten species he would most like to save from extinction.

“The olm lives life in the slow lane,” Attenborough says, per the Guardian’s Robin McKie, “which seems to be its secret for living a long life… and perhaps that is a lesson for us all.”

#News

0 notes

Video

Kranj CRAINBVRG CRAINBURG Stadt und Schloß Kieselstein Ansicht der Stadt in der Oberkrain mit Blick über die Save (Sava) und die Brücke by Vladimir Tkalčić

Via Flickr:

6400 Valvasor3 Johann Weikhard von Valvasor Die Ehre deß Herzogthums Crain The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola Laibach-Nürnberg 1689 III band Buch IX-XI 2te unveränderte Auflage Rudolfswerth 1877-1879. Druck und Verlag v. J. Krajec Author: Janez Vajkard Valvasor Date: 1689 Name: Kranj Slovenia Technique: Copper engraving Kranj CRAINBVRG CRAINBURG Stadt und Schloß Kieselstein Ansicht der Stadt in der Oberkrain mit Blick über die Save (Sava) und die Brücke hr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kranj#/media/File:Kranj.jpg --------------------------------

#6400#Valvasor3#Johann#Weikhard#von#Valvasor#Die#Ehre#deß#Herzogthums#Crain#The#Glory#Duchy#Carniola#Laibach-Nürnberg#1689#III#band#Buch#IX-XI#2te#unveränderte#Auflage#Rudolfswerth#1877-1879.#Druck#und#Verlag#v.

0 notes

Photo

Identity of Slovenia – Designing for the State

http://www.twenty.si/first-20-years/overview/before-and-now/identity-of-slovenia/

Mateja Malnar Štembal. June 2011.

The exhibition “Identity of Slovenia – Designing for the State,” held to mark the 20 years of independence in the Republic of Slovenia, was organized by the country’s central design organization, the Brumen Foundation, with the support and collaboration of the Ministry of Culture and National Gallery. The exhibition, on view at the National Gallery until mid-May 2011, is now moving to Slovenia’s representations abroad to display the country’s design highlights to the foreign public.

The exhibits cover the range of designs elaborated for the young state and its institutions by one of Slovenia’s top designers, Prešeren Award winner Miljenko Licul. Over the course of his artistic career, Licul has created a number of great works of visual culture that are closely related to the identity of the nation and state and are, by all means, the most recognizable visual images of Slovenia’s identity to be created over the 20-year history of Slovenia as a sovereign state.

The works Miljenko Licul designed for the state and its institutions have received much international acclaim and attention from professional and lay audiences, and are suitable to commemorate the anniversary as a dignified and innovative presentation of the country, its creative power, and its modern approach.

Working to accommodate the needs of the state administration and the daily life of its citizens, Licul developed a series of sophisticated design solutions, most of which are still used today and could easily stand comparison with the solutions of the most developed countries. Many Licul’s creations feature an interdisciplinary application of Slovenia’s values and the achievements of Slovenes in a variety of fields: culture and arts, science, nature and the environment, and society.

We should not fail to mention Slovenia’s former currency – the tolar – which has been out of circulation since the 2007 adoption of the euro but the visual design of the tolar banknotes and coins is still fresh in the memory of the nation.

Licul designed the banknotes in collaboration with his colleague Zvone Kosovelj and other authors. The engravings which were the basis for the images (Primož Trubar, Janez Vajkard Valvasor, Jurij Vega, Rihard Jakopič, Jože Plečnik, France Prešeren, and later Ivana Kobilica and Ivan Cankar) were made by painter Rudi Španzel, and the coins were modelled by sculptor Janez Boljka.

According to Licul, the eminent persons depicted on the banknotes were known across Europe, which is of utmost importance. The tools, also featured on the banknotes, portray the relationship between the person and his or her work. As nature is an essential element of life, the tolar coins featured animals. At the time, Licul also mentioned that the designers had to avoid using national symbols, as these were not finalized at the time of the project. It is, however, relevant that the banknotes bear the date 15 January 1992, which was chosen by the Council of the Bank of Slovenia as the date when independent Slovenia received its first international recognition.

Miljenko Licul, working together with Maja Licul and Janez Boljka, also designed Slovenia’s euro coins, recognizable all over Europe for their distinctive design. The visual image of Slovenia’s euro coins was selected in 2005. The outer edge of the coins bears the inscription “Slovenija,” making them easily distinguishable in the home country and elsewhere in Europe.

The national side of the coin depicts a stork, Europe’s largest bird, which also resides in Slovenia. The motif symbolically links Slovenia’s euro coins with the former tolar coins, as it was featured on the Slovenian 20 tolar coin. The 2 cent euro coin design features the Prince’s Stone, a reversed ancient Ionic column which was used in the inauguration ceremonies of Carantanian princes and, later, Carinthian dukes. It is a symbol of Slovenia’s sovereignty.

The Sower, depicted on the 5 cent coin, is embellished with round seeds and stars (these join up with the stars around the design and the number together reaches 25, the number of EU states at the time of Slovenia’s adoption of the euro). The sower is a frequent motif in paintings; the most famous Slovenian painting featuring this motif was painted by impressionist Ivan Grohar. The 10 cent euro coin design shows a line of text reading “Katedrala svobode” (“Cathedral of Freedom”), and an unrealized plan for the Slovenian Parliament building by architect Jože Plečnik.

The design for the 20 cent coin depicts a pair of Lipizzaner horses (representatives of a world-famous horse breed from the Lipica stud farm in Slovenia), and the 50 cent coin features Triglav (Slovenia’s highest mountain) below the constellation of Cancer (Slovenia achieved independence under the zodiac sign of Cancer), and the title of a patriotic song “Oj Triglav moj dom” (“Oh Triglav My Home”). The Slovenian design for the 1 euro coin contains a bust portrait of Primož Trubar and the words “Stati inu obstati” (“To Stand and Withstand”) taken from Trubar’s Sermon on Faith published in the 1550 Catechism, the first book written in the Slovene language. The 2 euro coin features a silhouette of France Prešeren, Slovenia’s greatest poet, and the words “Žive naj vsi narodi” (“God’s blessing on all nations”) in stylized Prešeren’s handwriting, from the 7th stanza of Zdravljica, Slovenia’s national anthem.

Miljenko Licul also designed a wide range of occasional, commemorative, and collector’s coins and is responsible for the visual image of Slovenia’s biometric passport, ID and health insurance card, and driver’s license. Moreover, Licul drew plans for Slovenia-Croatia Schengen border crossings (unrealized), designed a series of postage stamps, and elaborated numerous solutions for specific, local, and institutional needs.

As previously mentioned, the visual design of Slovenian passport bears the signature of Miljenko Licul. In its existing form, the passport was first published in 2001.

The motifs are selected to present, in both content and form, the country’s main cultural and historical information and features in a way that is appealing even to less attentive observers. Slovenia’s new visual identity was also determined by a series of motifs whose visual representation and historical importance confirm that all the relevant elements of the treasure-house of European culture were also present in the Slovenian territory. These fundamental theme elements include: the flat-earth representation of parts of Slovenia’s relief and the Vače situla, whereas the visa pages feature an excerpt from Slovenia’s national anthem.

Finally, there is a series of postage stamps entitled “Slovenija – Evropa v malem” (“Slovenia – Europe in Miniature”), which pays tribute to various artifacts from the nation’s rich cultural heritage. The motifs, most of them ethnographical, include: the mill on the Mura river; horn sleds; reed-pipes; double hayracks; earthen double bass; a Prekmurje house; the wind pump from Sečovlje Saltpans; a Karst house; the wine press; the Karst basket; the Ribnica horse; skis from Bloke; Easter eggs from Bela Krajina; a shoemaker’s light; a wind-rattle of Prlekija; a beehive; an Easter bundle from Ljubljana; a bootjack; and a wind mill

Miljenko Licul (1946 – 2009)

The designer Miljenko Licul was born in 1946 in the Istrian town of Vodnjan near Pula, where he attended elementary and secondary school. He moved to Ljubljana in 1964 to study architecture, and never left. In 1972 he started to work as graphic designer for Iskra, Yugoslavia’s largest company in the electrical industry of the time. In 1980 Licul founded his first design studio together with several friends, and worked as a freelance designer from then on. In the period 1988-2000 he taught typography at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana. For his work, Licul was awarded the highest professional awards, including the 2008 Prešeren Award for his life’s work. Miljenko Licul died in 2009.

The work of Miljenko Licul in graphic design is synonymous with superior quality. He was among the authors who renewed the strictly modernist graphic design style of the 1970s with a different, poetic expression without neglecting the content and historical elements of their tasks. He was a member of the generation of designers who successfully converted analogue images into digital form. With Miljenko Licul, the Slovenian graphic design strengthened its international presence and reputation.

Miljenko Licul sees and shows the present-day world, despite its technological advances or because of them, as a space where maximum effort should be used even with regard to the most mundane topics. The fundamental underlying message of Licul’s work is that the graphic design of items and texts paves the way, not only for the advance or demise of visual culture but also for the understanding, or misunderstanding, of the world.

Text by Mateja Malnar Štembal, based on texts by the Brumen Foundation and the National Gallery in Ljubljana

0 notes

Photo

Johann Koch, illustration for Janez Vajkard Valvasor’s Theatrum Mortis Humanæ Tripartitum, 1682.

137 notes

·

View notes